Abstract

Objective

To minimise the intake of industrial artificial trans fat (I-TF), nearly all European countries rely on food producers to voluntarily reduce the I-TF content in food. The objective of this study was to investigate the effect of this strategy on I-TF content in prepackaged biscuits/cakes/wafers in 2012–2013 in 20 European countries.

Design

The I-TF content was assessed in a market basket investigation. Three large supermarkets were visited in each capital, and in some countries, three additional ethnic shops were included.

Results

A total of 598 samples of biscuits/cakes/wafers with ‘partially hydrogenated vegetable fat’ or a similar term high on the list of ingredients were analysed, 312 products had more than 2% of fat as I-TF, exceeding the legislatively determined I-TF limit in Austria and Denmark; the mean (SD) was 19 (7)%. In seven countries, no I-TF was found, whereas nine predominantly Eastern European countries had products with very high I-TF content, and the remaining four countries had intermediate levels. Of the five countries that were examined using the same procedure as in 2006, three had unchanged I-TF levels in 2013, and two had lower levels. The 18 small ethnic shops examined in six Western European countries sold 83 products. The mean (SD) was 23 (12)% of the fat as I-TF, all imported from countries in Balkan. In Sweden, this type of food imported from Balkan was also available in large supermarkets.

Conclusions

The findings suggest that subgroups of the population in many countries in Europe still consume I-TF in amounts that increase their risk of coronary heart disease. Under current European Union (EU) legislation, the sale of products containing I-TF is legal but conflicts with the WHO recommendation to minimise the intake of I-TF. An EU-legislative limit on I-TF content in foods is expected to be an effective strategy to achieve this goal.

Keywords: Nutrition & Dietetics

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A strength is the measurement of trans fat in many popular foods obtained in large supermarkets in 20 different European countries in 2012–2013, and in popular foods obtained in ethnic shops in Berlin, Paris, London, Malmö and Copenhagen.

In South-eastern Europe, foods with high amounts of artificial trans fat (I-TF) are present in large supermarkets and the same brands of foods with high amounts of I-TF are present in ethnic shops in Western Europe.

Foods with high amounts of I-TF produced in some countries in Europe are legally exported to many other European countries.

A limitation is that the average daily intake of I-TF was not measured, but instead inferred from the presence of popular foods with high amounts of I-TF in large super markets and in small ethnic shops.

Introduction

Trans fat (TF) in food originates from the industrial hydrogenation of oils and from ruminant sources. Compared to non-hydrogenated oils, fats containing industrially produced artificial TF are solid at room temperature, have some technical advantages for food processing, and prolong the shelf life of products. I-TF can constitute up to 60% of the fat in certain foods, whereas ruminant fat contains 6% TF at most.1 A meta-analysis of four large prospective studies found that an average intake of approximately 5 g/day of TF, corresponding to 2% of the total energy intake, was associated with a 23% increase in the risk of coronary heart disease.2 Recently, TF intake has also been associated with all-cause mortality in a large US-based study.3 A 2013 review concluded that ‘the detrimental effects of industrial trans fatty acids on heart health are beyond dispute’.4 Furthermore, inverse associations have been observed between TF and essential long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in the blood lipids of pregnant women and their offspring at birth as well as in human milk. As the latter fatty acids are important for neurodevelopment in infancy, the potential untoward effect of TF exposure caused by fatty acid competition in the brain has received increased attention.5–7

Based on the relationship between the intake of I-TF and heart disease, for years several public health organisations have recommended that I-TF intake be lowered as much as possible.8–10

In 2003, Denmark introduced a legislative sales ban aimed at the final consumer, limiting the I-TF content in the fat of foods to a maximum of 2%. The legislation applies to locally produced as well as imported foods. The European Commission initially opposed this legislation but dropped its infringement proceedings in March 2007 because of increasing scientific evidence about the dangers of TF.11 In 2005, Canada introduced mandatory labelling of the I-TF content in prepackaged foods. The US introduced mandatory labelling of TF on prepackaged foods in 2006, (US foods could be labelled ‘zero TFA’ even if they contained 0.5 g per serving) followed by legislative limits on I-TF in the food served in restaurants in New York City in 2008, and in the state of California in 2010–2011. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has proposed that partially hydrogenated oils, the source of I-TF, no longer be ‘generally recognised as safe’. That means food companies would have to prove that such oils are safe to eat.12 In Europe in 2009, Austria and Switzerland introduced a legislative ban similar to the Danish regulation, followed by Iceland in 2011 and probably by Sweden, Hungary and Norway in 2014.13–15 However, in 2014, only a minority of the population in the European Union (EU; ie, less than 50 million of the 500 million people in the EU) is protected by legislation that makes it illegal to sell foods with high amounts of I-TF to the final consumer.

The purpose of the present study is to examine whether there still is a potentially negative health impact on vulnerable populations due to intake of I-TF contained in prepackaged biscuits/cakes/wafers in 20 European countries. These food items were chosen as they are frequently consumed and easily accessible. They furthermore traditionally contain I-TF rich partially hydrogenated vegetable oils as their major lipid ingredient.16 Removal of I-TF in this category of food has been slower than in other food categories.17 I-TF content in these foods may be a marker of I-TF in other products including products that are not sold in prepackaged form.

The inclusion criteria for the food samples were defined based on the list of ingredients printed on the packing. The same procedure was used in similar studies in 2006 and 2009.18 19 We further investigated whether products with high I-TF produced in some European countries were disseminated to other European countries, including ethnic shops. The findings may be relevant to the future regulation of the I-TF content in foods in the EU.20 By December 2014, the Commission, taking into account scientific evidence and experience acquired in Member States, intends to submit a report on the presence of TFs in foods. The aim of the report is to promote the provision of healthier food options to consumers including the provision of information on TF or restrictions on their use. The Commission shall accompany this report with a legislative proposal, if appropriate.

Methods

Purchase of biscuits/cakes/wafers in supermarkets

The 20 countries visited encompass the countries in former Yugoslavia, its neighbouring countries, three Scandinavian and three large countries in northern Europe: Germany, France and UK.

The main tourist office in the capital of each country was asked to identify three large supermarkets, preferably chain supermarkets with many large shops across the country. In several capitals, the same stores that were visited in 2006 and in 2009 were visited in this study.18 19

Inclusion criteria

As in the previous studies, packages of biscuits/cakes/wafers were obtained by systematically examining the labels of the products placed on the appropriate shelves in the biscuits/cakes/wafers section in the supermarket.

Packages were purchased

If ‘partially hydrogenated fat’ or a similar term was listed among the first four on the list of ingredients (ranked according to content).

If total fat content was equal to or exceeded 15 g of fat per 100 g of product, since high fat food is generally defined as food containing more than 15–20 g of total fat per 100 g food.21

If the label indicated the amount of TF per serving.

If the same product appeared in packages of different sizes, only the smallest size was bought.

If exactly the same package was found in two different supermarkets in the same capital, only the one with the latest ‘best before date’ was included in the study.

The packages from the three supermarkets in each capital were labelled and photographed, the package was opened, and two identical 50–100 g samples of the food were placed in appropriately labelled plastic bags. All the empty packages were stored, as were the receipts from the purchases. The name of the product, producer, country of origin, ‘best before’ date and the languages used in the list of ingredients were recorded.

Between May 2012 and September 2013, 454 packages were purchased in 60 supermarkets in the capitals of Albania, Austria, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Denmark, France, Germany, Hungary, The Former Yugoslav republic of Macedonia, Montenegro, Poland, Norway, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Sweden, the Czech Republic and the UK. In addition, 30 packages were bought in three large supermarkets in Malmö, the third largest city in Sweden.

Purchase of biscuits/cakes/wafers in ethnic shops

Because our analysis of the biscuits/cakes/wafers from supermarkets in the Balkan capitals yielded a relatively high number of foods with high amounts of I-TF, we decided to search for these types of Balkan foods in other countries using Google (search term: name of capital and ‘Balkan foods’) to identify ethnic shops selling Balkan foods. Three different shops were visited in Berlin, Copenhagen, London, Oslo and Paris and in addition in Malmö. A total of 114 prepackaged biscuits/cakes/wafers were purchased in these shops using the same inclusion criteria and sampling procedure as were used for the purchases in supermarkets.

Analysis of TF

The foods were homogenised, and the fatty acid content was analysed using gas chromatography on a 60 m highly polar capillary column using a modification of the AOAC 006·06 method. The analytical work was conducted by Microbac Laboratories, Warrendale, Pennsylvania, USA, an ISO-17025-certified laboratory.

Results

I-TFA content in prepackaged biscuits/cakes/wafers

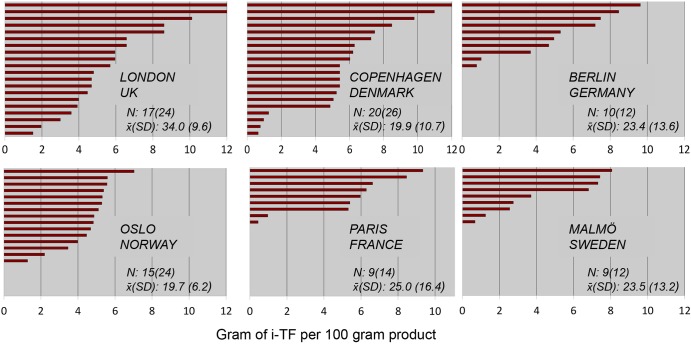

The I-TF content in the 312 products bought in the three supermarkets in each country was ranked according to I-TF level expressed in grams per 100 g of the product (figure 1). Each bar in each panel represents a product. Only products with more than 2% of the fat content as TF are shown. The first number given in the panel is the number of products with more than 2% of the fat content as TF. The number in parentheses is the number of products that fulfilled the inclusion criteria. The difference between the two numbers reflects the number of samples that did not contain appreciable amounts of TF despite the information on the label. The panels are ranked according to the sum of I-TF concentrations in the different products.

Figure 1.

Amounts of industrially produced artificial trans fat (I-TF) in 100 g of prepackaged biscuits/cakes/wafers with more than 2% I-TF of the total fat content, bought in three supermarkets in each of 20 European capitals and in Malmö, Sweden in 2012–2013. Each bar in a panel represents a product. N is the number of products. The number in parentheses is the number of foods that fulfilled the inclusion criteria.  (SD) is the mean value of I-TF% of total fat in the products shown in the panel. FYROM (The Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia). No products fulfilled the inclusion criteria in supermarkets in London, Paris, Berlin, Vienna, Copenhagen, Oslo and Stockholm.

(SD) is the mean value of I-TF% of total fat in the products shown in the panel. FYROM (The Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia). No products fulfilled the inclusion criteria in supermarkets in London, Paris, Berlin, Vienna, Copenhagen, Oslo and Stockholm.

Dissemination across countries

The highest amount was found in Bosnia Herzegovina, followed by Serbia. Of the 312 products made by 51 food producers in 15 European countries, 40% of the products had more than 20% of the fat as I-TF with a mean (SD) of 32 (7) %. We found 212 different products with more than 2% I-TFA in the fat. Only 10 food producers provided together 110 of the products that is, about 50%. One producer provided 30 different products. In the supermarkets in the capitals of Austria, Denmark, France, Germany, Norway, Sweden, and the UK, no samples were found that fulfilled the inclusion criteria (figure 1, lower right panel). The panel for three supermarkets in Malmö, Sweden was similar to the panels for Podgorica, Montenegro and Skopje, The Former Yugoslav republic of Macedonia, and was very different from the zero values found in the supermarkets in Copenhagen, Oslo and Stockholm.

Ethnic shops

A total of 83 packages of biscuits/cakes/wafers with high amounts of TF were bought in the ethnic shops in five capitals and in Malmö; this number varied between 9 and 20 for each shop (figure 2). Furthermore, 60% of the products had more than 20% of the fat as I-TF with a mean (SD) of 30 (9) %. Many of the products were the same in the six countries. These foods were also found in Copenhagen, which is surprising because their sale is illegal in Denmark, in contrast to the other countries in which the foods were found.

Figure 2.

Amounts of industrially produced artificial trans fat (I-TF) in 100 g of prepackaged biscuits/cakes/wafers with more than 2% I-TF of the total fat content bought in three ethnic shops in five European capitals in 2012–2013 and in Southern Sweden. Each bar in a panel represents a product. N is the number of products. The number in parentheses is the number of foods that fulfilled the inclusion criteria.  (SD) is the mean value of I-TF% of total fat in the products shown in the panel.

(SD) is the mean value of I-TF% of total fat in the products shown in the panel.

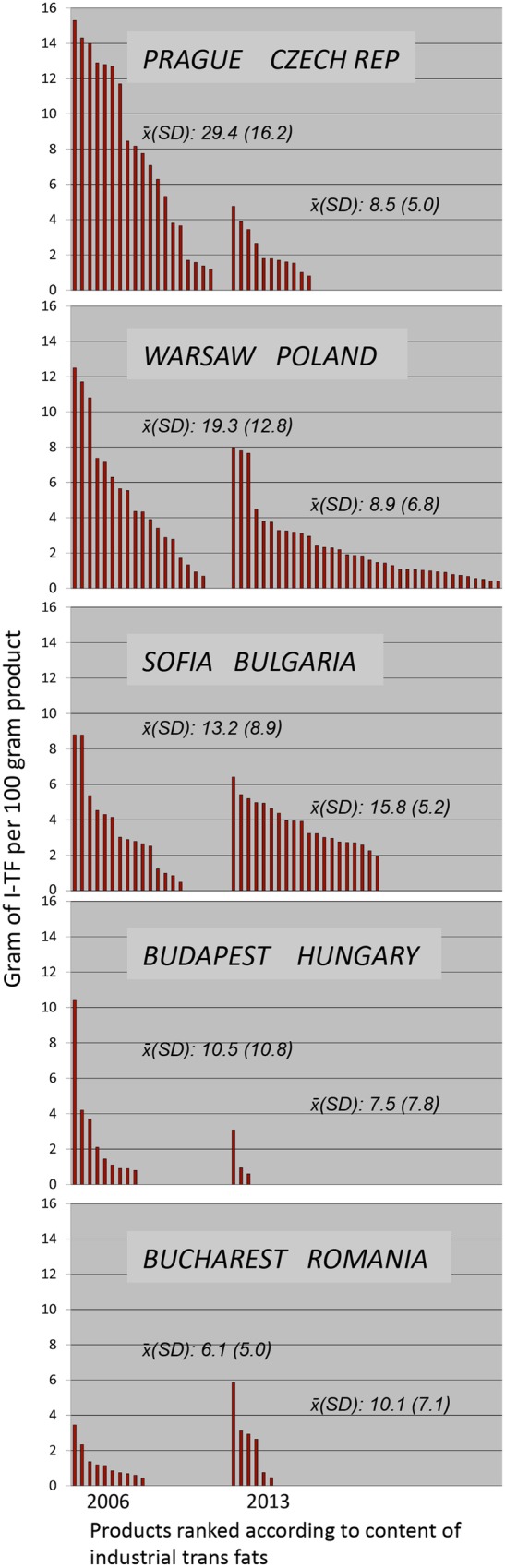

Comparison between 2006 and 2013

In Poland, Bulgaria and Romania, there were no obvious changes in the presence of many products with high I-TF between 2006 and 2013 (figure 3). The products in these countries were primarily from local food producers. Hungary and, especially, the Czech Republic showed a decline in high-I-TF foods during the same period.

Figure 3.

Amounts of industrially produced artificial trans fat (I-TF) in 100 g of prepackaged biscuits/cakes/wafers with more than 2% I-TF of the total fat content bought in three supermarkets in each of five capitals in Eastern Europe in 2006 and 2013.  (SD) is the mean value of I-TF% of total fat in the products shown in the panel.

(SD) is the mean value of I-TF% of total fat in the products shown in the panel.

Discussion

Products with industrial TF in supermarkets

In each of 20 European capitals, three large supermarkets were visited in 2012–2013, and in five of the capitals and in Malmö, Sweden, an additional three ethnic shops were visited. A total of 598 packages containing biscuits/cakes/wafers were bought and analysed for TF content, and 396 of these products contained high amounts of I-TF (more than 2 g/100 g of fat). In 25 different products, the I-TF content was higher than 40/100 g of fat. Similarly high values of I-TF in foods bought in Poland and in Serbia have also been reported in Polish and Serbian studies.22 23 The findings clearly demonstrate that I-TF is still present in 2013 in high concentrations in popular foods in many countries in Europe (figures 1 and 2).

Some foods with partially hydrogenated fat or a similar term in the list of ingredients did not contain significant amounts of TF based on a chemical analysis. A mixture of cis unsaturated fat and fully hydrogenated fat without TF is understood by some food producers to be partially hydrogenated fat.

In all 20 countries except for Denmark and Austria, it is legal to use as much I-TF in foods as technically possible without providing the quantity on the list of ingredients. Governments and consumer associations strive to follow the recommendations of the WHO. The voluntary reduction in the amount of I-TF in foods by food producers appears to work well in some countries, but not in others. Food producers in a given country or in neighbouring countries may remove I-TF from their products, but importing products with high I-TF content from more distant countries may counteract the initiatives, as demonstrated in the supermarkets in southern Sweden (figure 1, panel 4). Based on previous measurements, the I-TF content in biscuits/cakes/wafers from supermarkets in Germany, France and the UK was nearly eliminated between 2005 and 2009,19 and no products with significant amounts of TF were found in 2013 (figure 1). This result contrasts with the situation in Poland, Bulgaria and Romania, where there were no obvious changes in the presence of I-TF in foods between 2006 and 2013 (figure 3). The products in these countries were primarily from local food producers. Hungary and, especially, the Czech Republic showed a decline in high-I-TF foods during the same period.

Products with industrial TF in ethnic shops

Although the number of consumers who regularly buy food in ethnic shops may be lower than the number of consumers who purchase food in large supermarkets, the harmful effect of I-TF is still present. Studies from Sweden suggest that mortality due to heart disease among immigrants exceeds the mortality rate in the indigenous population.24–26 Using the same internet procedure that was used to identify shops with Balkan foods in other countries, three ethnic shops where prepackaged biscuits/cakes/wafers with high amounts I-TF were available were found in Copenhagen. These sales are illegal and can be stopped immediately by the food authorities, if they desire.27

In Southern Sweden, biscuits/cakes/wafers with high amounts of I-TF are present not only in small ethnic shops (figure 2) but also in large supermarkets (figure 1). This type of product has spread from the small ethnic shops to large supermarkets, suggesting considerable sales of these products, which remain legal in Sweden. The Swedish parliament decided in 2011 that Sweden should adopt the same I-TF legislation as Denmark, but the Swedish government decided to postpone the implementation on the advice of the Swedish food authorities because they found that all of the large food suppliers in Sweden, Norway and Denmark had removed I-TF from products sold in Sweden.13 They did not take into account the free flow of goods across borders in Europe. Many products with high amounts of I-TF have ingredient lists in more than 10 different languages, suggesting that they are potentially exported to many different countries. Retailers distributing these foods are present in Sweden and in other European countries, and the majority of products with high amounts of I-TF can be bought on the Internet, which is legal for private consumption only. Although foods with high amounts of I-TF were not found in large supermarkets in other Western countries, the Swedish story may repeat elsewhere.

The strength of this study is that it provides up-to-date data about the availability of popular foods containing high amounts of I-TF in 20 European countries. One weakness of the study is that the average daily intake of I-TF was not measured in subgroups of the population in the various countries but instead was inferred from the presence of biscuits/cakes/wafers with high amounts of I-TF in large supermarkets. The following assumptions led to the conclusion that these products have harmful effects: (1) the analysed brands of biscuits/cakes/wafers were stocked at the supermarkets because they are sold in considerable amounts; (2) the majority of these foods are regularly bought and consumed by the same subgroups of consumers and (3) the findings in the supermarkets in each capital are representative of the country. In addition, it is likely that the presence of I-TF in biscuits/cakes/wafers is a marker of a more widespread use of I-TF in other foods, including products that are not sold in a prepackaged form suggesting a higher intake of I-TF than that from biscuits/cakes/wafers. Another weakness of the study is that the foods were only bought in large supermarkets or in small ethnic shops with foods from the Balkans. The I-TF content in other foods sold by small, privately owned shops or street vendors was not examined. High amounts of I-TF prolong the shelf life of foods, and it is reasonable to assume that this factor is even more important for small shops than it is for larger supermarkets. The selective pattern of purchasing in the present study may thus have led to an underestimation of the amounts of I-TF consumed by subgroups of the population, such as truck and taxi drivers, manual labourers and members of minority ethnic groups, who already have an increased risk of coronary heart disease partly because of lifestyle factors such as smoking, poor diet and metabolic syndrome.28

A legislative limit of industrial TF in foods or a voluntary reduction?

EU countries, with the exceptions of Austria and Denmark, legally allow foods with a high amount of I-TF as a percentage of the total fat content (up to 60%) to be sold without notice as long as the food is unpackaged, as it is in restaurants and fast food outlets. If the food is prepackaged, the law requires the presence of I-TF to be noted only by the term ‘partially hydrogenated fat’ on the list of ingredients. Most consumers do not recognise the hazard concealed therein and will have difficulties in, or not attempt to decipher the often illegible text in the list of ingredients.29–31

Societal pressure on food producers has undoubtedly resulted in a reduction in the population-level mean intake of I-TF from 2005 to 2013, especially in Western EU countries19 but high intake of I-TF is still possible in Eastern Europe and South-eastern European countries, with no obvious downward trend in the availability of these foods from 2006 to 2013 in three of the countries (figure 3). High intake of I-TF in subgroups will continue as long as popular foods with a high concentration of I-TF are available. Although labelling foods with I-TF content may further reduce the mean intake of I-TF, such labelling still allows for the intake of high amounts because fast food in restaurants is not labelled and because consumers might not pay attention to or understand the labels.31 An important advantage of a legislative limit on the I-TF content of food is that it does not require that the population learn about the health risks of I-TF or pay attention to the labels of food products. Furthermore, it is simpler and less expensive to monitor the presence of I-TF in foods at the sales level than to monitor the actual intake of I-TF at the individual level in at-risk subgroups of the population.

Because many of the biscuits/cakes/wafers in the supermarkets that were visited did not contain I-TF, a legislative I-TF limit would not affect the supply of these foods and would most likely moderately affect the production of most food producers. It has been shown that I-TF in cakes, cookies and microwave popcorn can be replaced by a mixture of saturated, monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fat, which is a healthier fat composition than a one-to-one substitution of I-TF with saturated fat.32 A reduction in I-TF content without a commensurate increase in saturated fats was found in fast food purchases in New York City's restaurants after legislative restriction of I-TF in restaurants.33 The regulations in Austria, Denmark, Switzerland, Norway and Iceland have shown that the health risks of high intake of I-TF can be eliminated for the entire population without any noticeable side effects for consumers. The extent to which the difference in the presence of I-TF in popular foods in Eastern and Western Europe contributes to the much higher mortality from coronary heart disease in Eastern Europe than in Western Europe remains to be determined.34 It also needs to be determined to which extent the approximate 70% reduction (the highest reduction in the EU from 1980 to 2009) in coronary mortality among Danish men and women is actually due to a minimal intake of I-TF in all subgroups in Denmark during the latter part of this period.34

The effectiveness of policies for reducing dietary TF was recently assessed based on studies published between 2005 and 2012.17 It was found that ‘bans were most effective in eliminating TF from the food supply, whereas mandatory TF labelling and voluntary TF limits had a varying degree of success’. This statement is strongly supported by the findings in the present study concerning the current availability of popular foods with high amounts of I-TF in Europe, thus lending support to a legislative TF restriction by the EU. This is a low hanging fruit to pick in the prevention of coronary heart disease among 500 million EU citizens.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support from Jenny Vissings Foundation, University of Copenhagen and the Department of Clinical Biochemistry, Gentofte University Hospital.

Footnotes

Contributors: SS and JD were responsible for the concept design of the study, for collection of food items, registration and labelling. SS and JD produced the first draft of the study and SS, JD and AA were responsible for critical revision of the manuscript. SS is the guarantor.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data used to construct figures 1–3 can be shared by emailing Steen Stender.

References

- 1.Wahle KWJ, James WPT. Isomeric fatty acids and human health. Eur J Clin Nutr 1993;47:828–39 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mozaffarian D, Katan MB, Ascherio A, et al. Trans fatty acids and cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med 2006;354:601–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kiage JN, Merill PD, Robinson CJ, et al. Intake of trans fat and all-cause mortality in the Reasons for Geographical and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) cohort. Am J Clin Nutr 2013;97:1121–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brouwer IA, Wanders AJ, Katan MB. Trans fatty acids and cardiovascular health: research completed? Eur J Clin Nutr 2013;67:1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Decsi T, Boehm G. Trans isomeric fatty acids are inversely related to the availability of long-chain PUFAs in the perinatal period. Am J Clin Nutr 2013;98(Suppl):543S–8S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richardson AJ, Montgomery P. The Oxford-Durham study: a randomized, controlled trial of dietary supplementation with fatty acids in children with developmental coordination disorder. Pediatrics 2005;115:1360–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richardson AJ, Burton JR, Sewell RP, et al. Docosahexaenoic acid for reading, cognition and behavior in children aged 7-9 years: a randomized, controlled trial (the DOLAB Study). PLoS ONE 2012;7:e43909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uauy R, Aro A, Clarke R, et al. WHO Scientific Update on trans fatty acids: summary and conclusions. Eur J Clin Nutr 2009;63:68S–75S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.2010. Dietary Guidelines for Americans. http://www.health.gov/dietaryguidelines/dga2010/DietaryGuidelines2010.pdf (accessed Apr 2014)

- 10.2012. Nordic Nutrition Recommendations. http://www.norden.org/en/theme/nordic-nutrition-recommendation/nordic-nutrition-recommendations-2012 (accessed Apr 2014)

- 11.Stop Press: Commission drops Danish trans fat case. EU Food Law Weekly 2007;295 (23 Mar). http://www.eurofoodlaw.com/resources/pdfarchive (accessed May 2014) [Google Scholar]

- 12.US FDA. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/11/08/health/fda-trans-fats.html?hp&_r=1& (accessed Apr 2014)

- 13. Sveriges Riksdag. http://www.riksdagen.se/sv/Debatter-beslut/Interpellationsdebatter1/Debatt/?did=H010498&doctype=ip#pos=865 (accessed Apr 2014)

- 14. Hungary. http://www.eurofoodlaw.com/country-reports/eu-member-states/hungary/hungary-to-limit-transfats-track-consumption-69040.htm (accessed Apr 2014)

- 15.Norwegian Government. http://lovdata.no/dokument/LTI/forskrift/2014-01-16-34 (accessed Apr 2014)

- 16.Hooker N, Downs MS. Trans-border reformulation: US and Canadian experiences with trans fat. Int Food Agribusiness Manag Rev 2014;17(Special Issue A):131–46 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Downs MS, Thow AM, Leeder SR. The effectiveness of policies for reducing dietary trans fat: a systematic review of the evidence. Bull World Health Organ 2013;91:262–9H [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stender S, Dyerberg J, Bysted A, et al. A trans world journey. Atherosclr 2006;(Suppl 7):P47–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stender S, Astrup A, Dyerberg J. A trans European Union difference in the decline in trans fatty acids in popular foods: a market basket investigation. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2011L 304/35. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2011:304:0018:0063:EN:PDF (accessed Apr 2014)

- 21. NHS Choices. http://www.nhs.uk/Livewell/Goodfood/Pages/Fat.aspx (accessed Apr 2014)

- 22.Zbikowska A, Krygier K. Changes in the fatty acids composition, especially trans isomers, and heat stability of selected frying fats available on the polish market in the years 1997 and 2008. Pol J Food Nutr Sci 2011;61:45–9 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kravic SZ, Suturovic ZJ, Svarc-Gajic JV, et al. Fatty acid composition including trans-isomers of Serbian biscuits. Hem Ind 2011;65:139–46 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gadd M, Johansson SE, Sundquist J, et al. Morbidity in cardiovascular diseases in immigrants in Sweden. J Intern Med 2003;254:236–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gadd M, Johansson SE, Sundquist J, et al. The trend of cardiovascular disease in immigrants in Sweden. Eur J Epidemiol 2005;20:755–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sundquist K, Li X. Coronary heart disease risks in first- and second-generation immigrants in Sweden: a follow-up study. J Intern Med 2006;259:418–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Danish trans fat legislation. http://www.foedevarestyrelsen.dk/english/food/trans%20fatty%20acids/Pages/default.aspx (accessed Apr 2014)

- 28.Gill PE, Wijk K. Case study of a healthy eating intervention for Swedish lorry drivers. Health Educ Res 2004;19:306–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Consumers find food labelling confusing. http://www.guardian.co.uk/money/2009/may/07/food-drink-health-labels (accessed Apr 2014)

- 30.Borra S. Consumer perspectives on food labels. Am J Clin Nutr 2006;83:1235S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jasti S, Kovacs S. Use of trans fat information on food labels and its determinants in a multiethnic college student population. J Nutr Educ Behav 2010;42:307–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stender S, Astrup P, Dyerberg J. What went in when trans went out? N Engl J Med 2009;361:314–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Angell SY, Cobb LK, Curtis CJ, et al. Change in trans fatty aid content of fast-food purchases associated with New York City's restaurant regulation. Ann Intern Med 2012;157:81–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nichols M, Townsend N, Scarborough P, et al. Trends in age-specific coronary heart disease mortality in the European Union over three decades: 1980–2009. Eur Heart J 2013;34:3017–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.