Abstract

Objectives

To identify and critically assess the extent to which systematic reviews of enhanced recovery programmes for patients undergoing colorectal surgery differ in their methodology and reported estimates of effect.

Design

Review of published systematic reviews. We searched the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) and Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Database from 1990 to March 2013. Systematic reviews of enhanced recovery programmes for patients undergoing colorectal surgery were eligible for inclusion.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The primary outcome was length of hospital stay. We assessed changes in pooled estimates of treatment effect over time and how these might have been influenced by decisions taken by researchers as well as by the availability of new trials. The quality of systematic reviews was assessed using the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) DARE critical appraisal process.

Results

10 systematic reviews were included. Systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials have consistently shown a reduction in length of hospital stay with enhanced recovery compared with traditional care. The estimated effect tended to increase from 2006 to 2010 as more trials were published but has not altered significantly in the most recent review, despite the inclusion of several unique trials. The best estimate appears to be an average reduction of around 2.5 days in primary postoperative length of stay. Differences between reviews reflected differences in interpretation of inclusion criteria, searching and analytical methods or software.

Conclusions

Systematic reviews of enhanced recovery programmes show a high level of research waste, with multiple reviews covering identical or very similar groups of trials. Where multiple reviews exist on a topic, interpretation may require careful attention to apparently minor differences between reviews. Researchers can help readers by acknowledging existing reviews and through clear reporting of key decisions, especially on inclusion/exclusion and on statistical pooling.

Keywords: Surgery, Enhanced Recovery After Surgery, Fast Track

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Systematic reviews of randomised trials have consistently shown that enhanced recovery programmes reduce length of hospital stay for patients undergoing colorectal surgery, compared with usual care. The strength of this study is that we have looked in some detail at the available reviews to identify differences between them and possible explanations, such as differences in intervention and outcome definitions and handling of missing data from included trials in meta-analyses.

We found a high level of research waste, with multiple reviews covering identical or very similar groups of trials. Differences in pooled effect estimates across reviews reflected differences in interpretation of inclusion criteria, searching and analytical methods or software.

Where multiple reviews exist on a topic, interpretation may require careful attention to apparently minor differences between reviews. Researchers can help readers by acknowledging existing reviews and through clear reporting of key decisions, especially on inclusion/exclusion and on statistical pooling.

We identified limitations in reporting as one of the main barriers to understanding differences between reviews. These reporting issues often limited our ability to comment on whether decisions taken by review authors appear to be ‘right’ or ‘wrong’.

Introduction

Reduction in length of stay in secondary care hospital settings provides a key potential opportunity to improve productivity in healthcare systems. There has been growing interest over recent years in the use of enhanced recovery programmes (also known as enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS), fast track, multimodal, rapid or accelerated recovery programmes). The approach was pioneered in Denmark in the late 1990s for patients undergoing colorectal surgery and is now spreading to other surgical pathways such as musculoskeletal, urology and gynaecology.

The underlying aim of enhanced recovery programmes is to ensure that patients are in optimal condition for treatment (to minimise the risk of surgery being postponed or cancelled because of the patient's condition), receive innovative care during surgery and experience optimal postsurgical rehabilitation.1 Programmes differ widely but share common elements such as patient education and involvement in preoperative planning processes, preoperative oral carbohydrates, improved anaesthetic and postoperative analgesic techniques to reduce the physical stress of the operation, early oral feeding and mobilisation.2 3 Enhanced recovery programmes have been delivered in the UK National Health Service (NHS) since the early 2000s. Implementation has to date been variable despite the support of the department of health and more recently the Royal Colleges. It is likely that this variation reflects the complexity of enhanced recovery programmes themselves and issues around implementing change in fundamental surgical procedures at a time when the NHS is facing severe funding constraints.

There are a substantial number of systematic reviews and economic evaluations that examine the effectiveness and cost effectiveness of enhanced recovery programmes. We have used this evidence as the basis of a comprehensive rapid evidence synthesis relating to the effectiveness, cost effectiveness, implementation, delivery and impact of enhanced recovery programmes with particular reference to secondary care hospital settings in the NHS (Paton et al, in preparation). During the course of this project, we became aware of significant methodological differences between systematic reviews of enhanced recovery programmes in colorectal surgery (by far the largest body of evidence for any surgical specialty). Reviews published at around the same time varied in the trials they included and in their estimates (derived by meta-analysis) of the reduction in length of stay associated with enhanced recovery programmes.

The objective of this study, therefore, is to provide a critical overview of the methodology of the available systematic reviews and their contribution to the development of the evidence base available to decision-makers. In particular, we will examine how numerical estimates of the benefit of enhanced recovery on length of hospital stay have changed over time and how these might have been influenced by decisions taken by systematic reviewers as well as by the availability of new trials.

Methods

Literature searches

This study was carried out following a rapid synthesis of evidence relating to enhanced recovery programmes in all types of surgery (Paton et al, in preparation). To identify systematic reviews, we searched the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) and Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Database from 1990 to March 2013. See online supplementary appendix 1 for search strategies. The PROSPERO database was searched to identify any ongoing systematic reviews. Systematic reviews evaluating enhanced recovery programmes in patients undergoing any type of elective surgery in a hospital setting in the UK NHS or a comparable healthcare system were eligible for inclusion in the rapid evidence synthesis. Review authors’ definitions of enhanced recovery programmes were accepted. Outcomes of interest were any measure of clinical outcomes, patient experience or resource use. Reviews had to compare enhanced recovery with usual/standard care without a structured multimodal enhanced recovery pathway. For this methodological study, only systematic reviews of enhanced recovery programmes for colorectal surgery were considered.

Study selection

We stored the literature search results in a reference management database (EndNote X6). Two researchers independently screened all titles and abstracts obtained through the searches for potentially relevant articles. Full manuscripts of potentially relevant articles were ordered and two researchers independently assessed the relevance of each article using the criteria stated above. Disagreements between researchers were resolved by discussion or by recourse to a third researcher where necessary.

Quality assessment

Quality assessment of systematic reviews was based on the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) critical appraisal processes for DARE (http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/crdweb/HomePage.asp). Specific aspects assessed were adequacy of the search; assessment of quality/risk of bias of included studies; quality assessment results taken into account in the analysis; study details reported and differences between studies accounted for; investigation of statistical heterogeneity; were gaps in research identified; and were the review conclusions justified. The quality assessment was performed by one researcher and checked by a second. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion or by recourse to a third researcher.

Data extraction and analysis

Clinical effectiveness data for the rapid evidence synthesis were extracted into review software (EPPI Reviewer V.4.0). An analysis plan for this methodological study was prepared in advance and additional methodological information was extracted into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. Data were extracted by one researcher and checked by another; discrepancies were resolved by consensus or where necessary by recourse to a third researcher.

Data extracted from the reviews included the systematic review inclusion criteria (particularly the definition of an ERAS programme); randomised controlled trials (RCTs) included (number and list); length of stay mean difference (MD) estimates and 95% CIs for each RCT as reported in the review; meta-analysis methods (eg, type of model used); method used to handle missing means/SDs; definition of primary and total length of stay; pooled estimates of weighted MD (WMD) in length of stay between ERAS and control groups and source of funding.

Extracted data were examined and tabulated to identify differences between reviews that may have influenced their conclusions and quantitative estimates of the effectiveness of enhanced recovery programmes compared with usual care. We focused on the outcome of length of primary hospital stay (and total length of stay including readmissions, where reported) because reduction of length of stay is a key objective of enhanced recovery programmes and because length of stay was a primary outcome of most included systematic reviews. Only length of stay data from RCTs was included in this analysis.

Results

The report by Paton et al included 11 systematic reviews of ERAS programmes for colorectal surgery. One review4 focused on quality of life and patient satisfaction and another on compliance and variations in practice,5 leaving nine reviews that reported length of stay, of which seven reported a pooled effect estimate (WMD in days). The review by Zhuang et al,6 which was published too late to be fully discussed by Paton et al, is also included in this report, giving a total of 10 systematic reviews that met the inclusion criteria for this methodological study (table 1).

Table 1.

Overview of systematic reviews of ERAS for colorectal surgery

| Review | Minimum definition of ERAS intervention | Search cut-off date | Included RCTs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wind et al7 | At least four elements required | December 2005 | Anderson et al,8 Delaney et al,9 Gatt et al10 |

| Eskicioglu et al11 | Not stated | May 2008 | Anderson et al,8 Delaney et al,9 Gatt et al,10 Khoo et al12 |

| Gouvas et al13 | At least four elements required | July 2008 | Anderson et al,8 Delaney et al,9 Gatt et al,10 Khoo et al12 |

| Walter et al14 | At least five elements required (preoperative, perioperative and postoperative) | January 2007 | Anderson et al,8 Gatt et al10 |

| Varadhan et al15 | At least four elements required (preoperative, perioperative and postoperative) | November 2009 | Anderson et al,8 Delaney et al,9 Gatt et al,10 Khoo et al,12 Muller et al,16 Serclova et al,17 |

| Adamina et al18 | Documented compliance with at least four of five key elements | June 2010 | Anderson et al,8 Delaney et al,9 Gatt et al,10 Khoo et al,12 Muller et al,16 Serclova et al17 |

| Rawlinson et al19 | At least four elements required (preoperative, perioperative and postoperative) | February 2011 | Anderson et al,8 Delaney et al,9 Gatt et al,10 Khoo et al,12 Muller et al,16 Serclova et al17 |

| Spanjersberg et al20 | At least seven elements required | Unclear (January 2011?) | Anderson et al,8 Gatt et al,10 Khoo et al,12 Serclova et al17 |

| Lv et al21 | Not stated | April 2012 | Anderson et al,8 Delaney et al,9 Gatt et al,10 Khoo et al,12 Muller et al,16 Serclova et al,17 Vlug et al22 |

| Zhuang et al6 | At least seven elements required | July 2012 | Anderson et al,8 Gatt et al,10 Khoo et al,12 Muller et al,16 Serclova et al,17 Ionescu et al,23 Vlug et al,22 Garcia-Botello et al,24 van Bree et al,25 Ren et al,26 Wang G et al,27 Wang Q et al,28 Yang et al29 |

ERAS, enhanced recovery after surgery; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Most of the included reviews were reasonably well conducted and reported (table 2). The reviews by Wind et al,7 Walter et al,14 Spanjersberg et al20 and Zhuang et al6 met all seven quality criteria and were considered at low risk of bias. Three other reviews met six criteria but all failed to take study quality into account in their synthesis.11 13 15 Adamina et al18 and Lv et al21 failed to meet two of the criteria, while the paper by Rawlinson et al19 only clearly met two criteria and was considered potentially at high risk of bias.

Table 2.

Risk of bias in included systematic reviews

| Review | Adequate search | Risk of bias assessed | Quality score accounted for in analysis | Study details reported and differences accounted for | Statistical heterogeneity investigated | Gaps in research identified | Conclusions justified |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wind et al7 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Eskicioglu et al11 | ✓ | ✓ | X | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Gouvas et al13 | ✓ | ✓ | X | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Walter et al14 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Varadhan et al15 | ✓ | ✓ | X | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Adamina et al18 | ✓ | ✓ | UC | ✓ | UC | ✓ | ✓ |

| Rawlinson et al19 | ✓ | X | X | ✓ | UC | X | UC |

| Spanjersberg et al20 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Lv et al21 | ✓ | ✓ | X | X | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Zhuang et al6 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

UC, unclear.

Chronological development of the evidence base

Four systematic reviews were published in the years 2006–2009. At this stage, only a few randomised trials were available. Wind et al7 included three trials; Eskicioglu et al and Gouvas et al four trials and Walter et al included just two trials (table 1).

Four further reviews were published in 2010 and 2011. These all considered the same six trials, although one review chose to exclude two of these from its main analysis because the intervention did not meet the review definition of an ERAS programme.20

A systematic review by Lv et al published in 2012 added one more trial, bringing the total to seven. However, just a year later Zhuang et al published a systematic review with 13 included trials, among them 4 recent trials by Chinese investigators. With one exception,25 the trials included in this review were identified and discussed by Paton et al in our review of trials not included in the then-available systematic reviews.

The included reviews varied somewhat in the extent to which they cited previously published reviews of the field. However, in general, reviews tended to cite most of the earlier reviews that would have been available at the time of writing. The first systematic review, by Wind et al, was cited by eight of the nine subsequent reviews. Gouvas et al's review was cited by six of seven subsequent reviews and Varadhan et al by four out of five (table 3). The main exception was the paper by Rawlinson et al,19 which was not cited by three later reviews. Adamina et al differed from other researchers in their use of Bayesian methodology and their work was only cited by one of the four later reviews. Zhuang et al cited all the previous systematic reviews except that of Lv et al, which may have been published too late to be included.

Table 3.

Cross-citation among included systematic reviews

| Review | Reviews cited | Cited by subsequent reviews |

|---|---|---|

| Wind et al7 | NA | Eskicioglu et al,11 Gouvas et al,13 Walter et al,14 Varadhan et al,15 Adamina et al,18 Rawlinson et al,19 Spanjersberg et al,20 Zhuang et al6 |

| Eskicioglu et al11 | Wind et al7 | Varadhan et al,15 Rawlinson et al,19 Zhuang et al6 |

| Gouvas et al13 | Wind et al7 | Varadhan et al,15 Adamina et al,18 Rawlinson et al,19 Spanjersberg et al,20 Lv et al,21 Zhuang et al6 |

| Walter et al14 | Wind et al7 | Varadhan et al,15 Spanjersberg et al,20 Lv et al,21 Zhuang et al6 |

| Varadhan et al15 | Wind et al,7 Eskicioglu et al,11 Gouvas et al,13 Walter et al14 | Rawlinson et al,19 Spanjersberg et al,20 Lv et al,21 Zhuang et al6 |

| Adamina et al18 | Wind et al,7 Gouvas et al13 | Zhuang et al6 |

| Rawlinson et al19 | Wind et al,7 Eskicioglu et al,11 Gouvas et al,13 Varadhan et al15 | Not cited |

| Spanjersberg et al20 | Wind et al,7 Gouvas et al,13 Walter et al,14 Varadhan et al15 | Lv et al,21 Zhuang et al6 |

| Lv et al21 | Gouvas et al,13 Walter et al,14 Varadhan et al,15 Spanjersberg et al20 | Not cited |

| Zhuang et al6 | Wind et al,7 Eskicioglu et al,11 Gouvas et al,13 Walter et al,14 Varadhan et al,15 Adamina et al,18 Spanjersberg et al20 | NA |

NA, not applicable.

Methodological differences between systematic reviews

The four early systematic reviews of ERAS for colorectal surgery showed a number of methodological differences. Although inclusion criteria appeared similar, Walter et al excluded two trials that were included in the reviews by Eskicioglu et al and Gouvas et al. In one case,9 this was reported to be because the trial included some patients who had undergone small bowel surgery; the reason for the other exclusion12 was not reported. Walter et al also differed from the other reviews in its definition of outcomes: length of stay was measured as total days of admission in this review and as days spent in hospital after surgery in the other reviews published in the same period.

In terms of data synthesis, Eskicioglu et al was the only one of the four early reviews that did not perform a meta-analysis, on the grounds that data in the right form (means and SDs) were not available. The remaining three reviews elected to pool. Gouvas et al and Wind et al used random effects models for their main meta-analysis, while Walter et al used a fixed effects model. Wind et al and Walter et al justified their choice on the basis of a random effects model being more appropriate in the presence of some heterogeneity but neither stated a level of heterogeneity above which a random effects model should be used. Wind et al stated that trials without means and SDs were omitted from the analysis, while Gouvas et al estimated from reported medians and ranges where necessary. Walter et al did not report on this point.

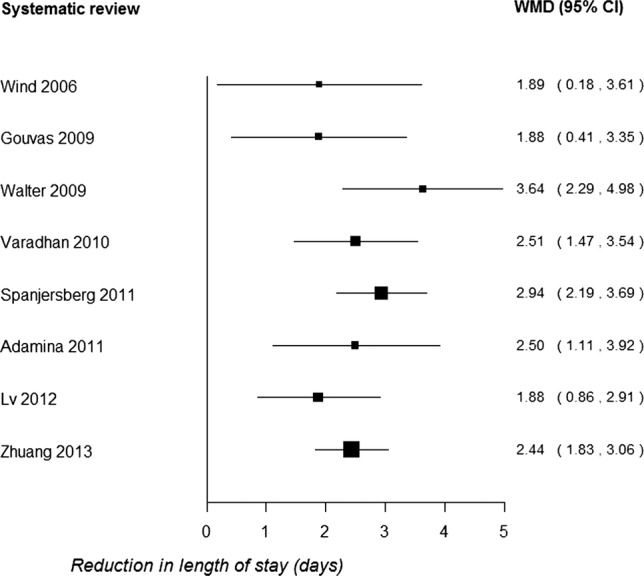

Pooled estimates (WMD) of the effect of ERAS on primary length of stay varied substantially, being considerably higher and with a wider CI in Walter et al compared with the other reviews (figure 1 and table 4). Wind et al and Gouvas et al provided almost identical WMDs, the only effect of an additional trial in Gouvas et al being to slightly narrow the 95% CI. Walter et al reported no statistical heterogeneity while the other two reviews found some evidence of heterogeneity.

Figure 1.

Summary of pooled results for primary length of stay (WMD, weighted mean difference).

Table 4.

Summary of meta-analyses for length of stay

| Review | Definition of primary length of stay | Meta-analysis model | Pooled effect estimate for primary length of stay | Pooled effect estimate for total length of stay |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wind et al7 | Days in hospital after surgery | Random | WMD −1.89 (−3.61 to −0.18), I2=63.4% | Not calculated |

| Eskicioglu et al11 | Days in hospital after surgery | NA | Not calculated (authors stated pooling was not feasible) | |

| Gouvas et al13 | Days in hospital after surgery | Random | WMD −1.88 (−3.35 to −0.41), I2=45% | WMD −1.73 (−3.50 to 0.04), I2=0% |

| Walter et al14 | Days in hospital during index admission | Fixed | WMD −3.64 (−4.98 to −2.29), I2=0% | WMD −3.75 (−5.11 to −2.40), I2=0% |

| Varadhan et al15 | Not explicitly defined but appears to be days in hospital after surgery | Random | WMD −2.51 (−3.54 to −1.47), I2=55% | Not calculated |

| Adamina et al18 | Length of stay outcome not explicitly defined | Bayesian | Mean difference for ‘length of stay’ −2.5 (95% CI −3.92 to −1.11), I2 not reported | |

| Rawlinson et al19 | Not defined | NA | Not calculated (authors cited findings from Gouvas and Varadhan) | |

| Spanjersberg et al20 | Not explicitly defined but appears to be days in hospital after surgery | Fixed | WMD −2.94 (−3.69 to −2.19), I2=0% | Not calculated |

| Lv et al21 | Days in hospital during index admission | Random | WMD −1.88 (−2.91 to −0.86), I2=75% | Not calculated |

| Zhuang et al6 | Days in hospital after surgery | Random | WMD −2.44 (−3.06 to −1.83), I2=88% | WMD −2.39 (−3.70 to −1.09), I2=85% |

NA, not applicable; WMD, weighted mean difference.

Overall, these reviews suggested considerable uncertainty about the magnitude of the effect of ERAS programmes in reducing length of hospital stay. Based on 95% CIs, the effect could plausibly range from less than 0.5 to almost 5 days.

The next group of systematic reviews to be published 15 18 19 20 included up to six RCTs (additional RCTs by Muller et al16 and Serclova et al17 were now available). Spanjersberg et al differed from other authors in treating length of stay as a secondary outcome of the review and more significantly by excluding two trials that were included in most other systematic reviews. The authors stated that Muller et al and Delaney et al9 failed to meet the inclusion criterion of including at least seven elements in the ERAS intervention.

None of these reviews provided clear definitions of outcomes but Varadhan et al and Spanjersberg et al appeared to measure days in hospital after surgery (ie, primary length of stay). Adamina et al reported their outcome as length of hospital stay without definition or distinguishing between primary and total length of stay. The reviews also differed in their reported treatment of studies with missing data (mean/SD): Varadhan et al obtained data from original authors, Spanjersberg et al calculated from median and range and Adamina et al did not report their methods. Adamina et al were the only authors who used Bayesian methods for meta-analysis, although few details were reported.18 Rawlinson et al19 did not report an original meta-analysis but instead discussed the findings of Gouvas et al and Varadhan et al.

Compared with the earlier reviews, this group of systematic reviews reported a substantially narrower range of effect estimates, all suggesting a reduction of 2.5–3 days in primary hospital stay associated with ERAS programmes (table 1). The range of 95% CIs was also narrower (approximately 1.1–3.9 days).

The 2012 review by Lv et al21 added one additional RCT for a total of seven trials. The new trial22 compared ERAS with traditional care in patients undergoing laparoscopic and open surgery and so was treated as two trials in the meta-analysis. The trial showed a 1-day reduction in length of stay in the laparoscopic setting, but there was no difference in patients undergoing open surgery. Lv et al also differed from most of the earlier reviews in defining length of stay as length of the index admission (rather than days in hospital after surgery). It is unclear whether this explains the discrepancy but Lv et al reported a smaller reduction in length of stay compared with the reviews immediately preceding it (−1.88 days, 95% CI −2.91 to −0.86). However, this estimate was still compatible with a ‘true’ reduction of around 2–3 days in primary length of stay.

The most recent systematic review that we are aware of was published in May 2013, too late to be considered in detail in the full report.6 It is more comprehensive than the previous reviews, with 13 included trials (two with open and laparoscopic arms) and 1910 participants. All except one30 of the RCTs included in our report were also in this systematic review. However, Zhuang et al also included one trial that we excluded.25 In fact, this publication is a single-centre report of results from the laparoscopy and/or fast track multimodal management versus standard care (LAFA) trial that was reported in full by Vlug et al,22 so it is likely that there was double counting of these patients in Zhuang et al's meta-analyses. However, this publication was not included in the meta-analysis of length of stay outcomes.

Some of the trials included for the first time in Zhuang et al's review, particularly that of Ionescu et al,23 were available to earlier systematic reviewers. Of the reviews published in 2010 or later, Varadhan et al did not give references for any excluded studies. Adamina et al gave references for excluded studies but did not list Ionescu et al, suggesting that their search did not locate this trial. Rawlinson et al did not list excluded studies, while the Cochrane review by Spanjersberg et al did not list Ionescu et al among the excluded studies. Lv et al excluded 26 out of 33 studies examined in full text but did not report any details.

There was a discrepancy between Zhuang et al and Lv et al in their data extraction of the trial by Vlug et al. There were also minor data extraction discrepancies between these reviews for two other trials, but as they were in opposite directions in the two cases, this is unlikely to have had a major impact on the overall meta-analysis results.

Like most included reviews, Zhuang et al defined length of stay as time in hospital after surgery. The pooled estimate of a 2.44 day reduction in primary length of stay (95% CI 1.83 to 3.06) for ERAS relative to traditional care was very similar to those reported by Varadhan et al15 and Adamina et al.18

Discussion

Main findings

Systematic reviews of randomised trials have consistently shown a reduction in length of hospital stay with ERAS compared with traditional care. The estimated effect tended to increase over time from 2006 to 2010 as more trials were published but has not altered significantly in the most recent review, despite the inclusion of several unique trials. The best estimate appears to be an average reduction of around 2.5 days in primary postoperative length of hospital stay. However, there is considerable heterogeneity in most pooled estimates and the complexity of ERAS as an intervention means that the benefits achieved in routine practice may differ from those reported in clinical trials. These issues are discussed in the full project report (Paton et al, in preparation).

The published systematic reviews show a high level of redundancy, with multiple reviews covering identical or very similar groups of trials. Differences in pooled effect estimates across reviews reflect differences in interpretation of inclusion criteria, searching and analytical methods or software. A few data extraction discrepancies were observed but these are unlikely to have significantly affected review conclusions.

Findings in relation to previous studies

The existence of multiple systematic reviews covering the same topic was investigated by Siontis et al.31 They found that of 73 systematic reviews (with meta-analysis) published in 2010, 49 (67%) had at least one other published meta-analysis on the same topic. A particularly striking example was the existence of 11 meta-analyses of statins to prevent atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery; all except the first of these showed a large positive effect of the intervention. Our findings reinforce those of Siontis et al, although even where reviews included exactly the same trials, their pooled estimates of effect were not necessarily identical. Enhanced recovery differs from an intervention like statins after cardiac surgery, being more complex and changing over time as more elements are incorporated into routine practice. This would tend to favour increased variation between reviews along the lines we observed.

A slightly different approach to investigating overlap between systematic reviews was taken by Woodman et al,32 who looked at the differences between eight reviews of community interventions to promote physical activity. Across the eight reviews, there were 28 included studies, of which 22 (79%) were only included in one review. There was little cross-citation between reviews. For most reviews, Woodman et al could explain why primary data were not included, which was usually due to the reviews having a relatively narrow scope. Despite these issues, the review conclusions were similar. Comparing our results with those of Woodman et al, the enhanced recovery reviews had a higher degree of overlap, although they differed with respect to inclusion of non-randomised studies (not discussed in this paper). The differences between the enhanced recovery and physical activity reviews probably reflect the fact that enhanced recovery, although a complex intervention, is more narrowly defined than interventions to increase physical activity.

Implications

The findings of this study have implications for systematic reviewers, readers of systematic reviews and producers of systematic review-based evidence products. Systematic reviewers can help readers compare their reviews with other similar studies by clear reporting of key decisions, especially on inclusion/exclusion and on statistical pooling. Most of the reviews of enhanced recovery programmes performed a meta-analysis to calculate a WMD in length of stay between enhanced recovery and usual care groups. Calculating the WMD requires the means and SDs of length of stay in each group in the included trials, but trials often report a different measure such as median and range (or IQR). Systematic reviews can deal with this situation in different ways, for example, by using formulae to estimate the mean and SD, contacting the trial authors or omitting trials from any meta-analysis if mean and SD are not reported. The enhanced recovery reviews adopted all of these approaches but did not report which data were estimated rather than derived directly from trial reports. Improved reporting in this area would improve transparency and help readers to understand discrepancies between apparently similar meta-analyses. Length of stay outcomes was not always clearly defined or reported and differences between reviews may in part stem from the fact that they were measuring an outcome in different ways.

Readers of systematic reviews need to be aware of the existence of multiple systematic reviews for a high percentage of topics. This means they should not rely uncritically on the first review they find and underlines the importance of services that critically appraise systematic reviews and those that provide overviews of reviews across a topic area.33 34 As an aid to transparency, authors of new systematic reviews should also acknowledge the existence of any systematic reviews addressing the same or a similar question.

The use of systematic reviews to produce rapid evidence summaries to inform decision-making is an area where methodology is still developing, although some methodological frameworks have been published.35 36 Assessment of the quality and reliability of systematic reviews is an important part of this process, but the present study suggests that conventional approaches to critical appraisal are not sufficient and careful attention should be paid to apparently minor differences between reviews. This may require increased extraction of methodological data, although the results may not be included in published evidence summaries aimed at decision-makers.

Strengths and limitations

The strength of this study is that we have looked in some detail at reviews of a complex clinical intervention to identify differences between them and possible explanations, such as differences in intervention and outcome definitions and handling of missing data from included trials in meta-analyses. We have identified limitations in reporting as one of the main barriers to understanding differences between reviews of the same topic. These reporting issues have often limited our ability to comment on whether decisions taken by review authors appear to be ‘right’ or ‘wrong’. The discrepancies between reviews identified in this study sometimes arose from decisions where both options could be considered reasonable, for example, whether or not to exclude the trial by Delaney et al9 because a small number of patients undergoing small bowel surgery were included.

This study only considered length of stay outcomes. Length of stay was selected as the primary outcome because of its importance for the health service at a time of acute financial pressure and because it was an outcome considered in all the included systematic reviews. Other important outcomes, including morbidity and mortality, are discussed in the full report (Paton et al, in preparation).

Unanswered questions/further research

The current study suggests a need for further, more in-depth research into methods of quality assessment of systematic reviews; to make the best use of a cumulative evidence base for decision-making and to identify methodological issues and decision points that may influence the eventual conclusions of a review. These issues are particularly important for researchers seeking to help decision-makers interpret and use systematic reviews. Enhanced recovery is a complex intervention with multiple components and its successful implementation is likely to be influenced by numerous background factors. Given this background, researchers and clinicians carrying out new systematic reviews should ensure that their chosen method of synthesis is appropriate for exploring intervention complexity. The recently published research agenda for reviews of complex interventions37 provides timely guidance in this regard. Ideally, systematic reviews of emerging complex interventions (eg, interventions to support integration of health and social care) should use standardised methods and outcome definitions and be regularly updated, although this may be difficult to achieve in practice.

Systematic reviews of enhanced recovery programmes in colorectal surgery continue to be published and we are aware of at least two publications since our search was completed.38 39 The authors of one of these reviews refer to their paper as ‘a substantial update from previous meta-analyses’38 but in fact the included trials and overall findings are almost identical to those of Zhuang et al.6 This is not the fault of the authors but represents an avoidable waste of research resources. Systematic reviews are now increasingly being registered prospectively at the outset on databases such as PROSPERO40 and it will be interesting to see whether the production of overlapping reviews decreases over time.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to the design of this methodological study and commented on the analysis plan and/or draft manuscript. PW took overall responsibility for the rapid evidence synthesis and is the guarantor. DC and FP extracted additional methodological data. DC wrote the first draft of the paper. All authors have seen and approved the final version.

Funding: This project was funded as part of a programme of research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research programme (Project ref: 11/1026/04).

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Enhanced Recovery Partnership Programme. Delivering enhanced recovery—helping patients to get better sooner after surgery. London: Department of Health, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kehlet H, Wilmore DW. Multimodal strategies to improve surgical outcome. Am J Surg 2002;183:630–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sturm L, Cameron AL. Brief review: fast-track surgery and enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) programs. Melbourne: Australian Safety and Efficacy Register of New Interventional Procedures—Surgical (ASERNIP-S), 2009, Contract No: 3 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khan S, Wilson T, Ahmed J, et al. Quality of life and patient satisfaction with enhanced recovery protocols. Colorectal Dis 2010;12:1175–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmed J, Khan S, Lim M, et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery protocols—compliance and variations in practice during routine colorectal surgery. Colorectal Dis 2012;14:1045–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhuang CL, Ye XZ, Zhang XD, et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery programs versus traditional care for colorectal surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Dis Colon Rectum 2013;56:667–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wind J, Polle SW, Fung Kon Jin PH, et al. Systematic review of enhanced recovery programmes in colonic surgery. Br J Surg 2006;93:800–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson AD, McNaught CE, MacFie J, et al. Randomized clinical trial of multimodal optimization and standard perioperative surgical care. Br J Surg 2003;90:1497–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delaney CP, Zutshi M, Senagore AJ, et al. Prospective, randomized, controlled trial between a pathway of controlled rehabilitation with early ambulation and diet and traditional postoperative care after laparotomy and intestinal resection. Dis Colon Rectum 2003;46:851–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gatt M, Anderson AD, Reddy BS, et al. Randomized clinical trial of multimodal optimization of surgical care in patients undergoing major colonic resection. Br J Surg 2005;92:1354–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eskicioglu C, Forbes SS, Aarts M-A, et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) programs for patients having colorectal surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Gastrointest Surg 2009;13:2321–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khoo CK, Vickery CJ, Forsyth N, et al. A prospective randomized controlled trial of multimodal perioperative management protocol in patients undergoing elective colorectal resection for cancer. Ann Surg 2007;245:867–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gouvas N, Tan E, Windsor A, et al. Fast-track vs standard care in colorectal surgery: a meta-analysis update. Int J Colorectal Dis 2009;24:1119–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walter CJ, Collin J, Dumville JC, et al. Enhanced recovery in colorectal resections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Colorectal Dis 2009;11:344–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Varadhan KK, Neal KR, Dejong CH, et al. The enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) pathway for patients undergoing major elective open colorectal surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Nutr 2010;29:434–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muller S, Zalunardo MP, Hubner M, et al. A fast-track program reduces complications and length of hospital stay after open colonic surgery. Gastroenterology 2009;136:842–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Serclova Z, Dytrych P, Marvan J, et al. Fast-track in open intestinal surgery: prospective randomized study (Clinical Trials Gov Identifier no. NCT00123456). Clin Nutr 2009;28:618–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adamina M, Kehlet H, Tomlinson GA, et al. Enhanced recovery pathways optimize health outcomes and resource utilization: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials in colorectal surgery. Surgery 2011;149:830–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rawlinson A, Kang P, Evans J, et al. A systematic review of enhanced recovery protocols in colorectal surgery. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2011;93:583–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spanjersberg Willem R, Reurings J, Keus F, et al. Fast track surgery versus conventional recovery strategies for colorectal surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;(2):CD007635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lv L, Shao Y-f, Zhou Y-b. The enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) pathway for patients undergoing colorectal surgery: an update of meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Colorectal Dis 2012;27:1549–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vlug MS, Wind J, Hollmann MW, et al. Laparoscopy in combination with fast track multimodal management is the best perioperative strategy in patients undergoing colonic surgery: a randomized clinical trial (LAFA-study). Ann Surg 2011;254:868–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ionescu D, Iancu C, Ion D, et al. Implementing fast-track protocol for colorectal surgery: a prospective randomized clinical trial. World J Surg 2009;33:2433–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garcia-Botello S, Canovas de Lucas R, Tornero C, et al. Implementation of a perioperative multimodal rehabilitation protocol in elective colorectal surgery. A prospective randomised controlled study. Cir Esp 2011;89:159–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Bree SH, Vlug MS, Bemelman WA, et al. Faster recovery of gastrointestinal transit after laparoscopy and fast-track care in patients undergoing colonic surgery. Gastroenterology 2011;141:872–80.e1–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ren L, Zhu D, Wei Y, et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) program attenuates stress and accelerates recovery in patients after radical resection for colorectal cancer: a prospective randomized controlled trial. World J Surg 2012;36:407–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang G, Jiang Z, Zhao K, et al. Immunologic response after laparoscopic colon cancer operation within an enhanced recovery program. J Gastrointest Surg 2012;16:1379–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Q, Suo J, Jiang J, et al. Effectiveness of fast-track rehabilitation vs conventional care in laparoscopic colorectal resection for elderly patients: a randomized trial. Colorectal Dis 2012;14:1009–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang D, He W, Zhang S, et al. Fast-track surgery improves postoperative clinical recovery and immunity after elective surgery for colorectal carcinoma: randomized controlled clinical trial. World J Surg 2012;36:1874–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee TG, Kang SB, Kim DW, et al. Comparison of early mobilization and diet rehabilitation program with conventional care after laparoscopic colon surgery: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Dis Colon Rectum 2011;54:21–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Siontis KC, Hernandez-Boussard T, Ioannidis JP. Overlapping meta-analyses on the same topic: survey of published studies. BMJ 2013;347:f4501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Woodman J, Thomas J, Dickson K. How explicable are differences between reviews that appear to address a similar research question? A review of reviews of physical activity interventions. Syst Rev 2012;1:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chambers D, Wilson P, Thompson C, et al. Maximizing the impact of systematic reviews in healthcare decision-making: a systematic scoping review of knowledge translation resources. Milbank Q 2011;89:131–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lavis JN. How can we support the use of systematic reviews in policymaking? PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chambers D, Wilson P. A framework for production of systematic review based briefings to support evidence-informed decision-making. Syst Rev 2012;1:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khangura S, Konnyu K, Cushman R, et al. Evidence summaries: the evolution of a rapid review approach. Syst Rev 2012;1:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Noyes J, Gough D, Lewin S, et al. A research and development agenda for systematic reviews that ask complex questions about complex interventions. J Clin Epidemiol 2013;66:1262–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Greco M, Capretti G, Beretta L, et al. Enhanced recovery program in colorectal surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World J Surg 2014;38:1531–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gianotti L, Beretta S, Luperto M, et al. Enhanced recovery strategies in colorectal surgery: is the compliance with the whole program required to achieve the target? Int J Colorectal Dis 2014;29:329–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Booth A, Clarke M, Dooley G, et al. PROSPERO at one year: an evaluation of its utility. Syst Rev 2013;2:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.