Abstract

Purpose

Patients with Cowden syndrome (CS) with underlying germline PTEN mutations are at increased risk of breast, thyroid, endometrial, and renal cancers. To our knowledge, risk of subsequent cancers in these patients has not been previously explored or quantified.

Patients and Methods

We conducted a 7-year multicenter prospective study (2005 to 2012) of patients with CS or CS-like disease, all of whom underwent comprehensive PTEN mutational analysis. Second malignant neoplasms (SMNs) were ascertained by medical records and confirmed by pathology reports. Standardized incidence ratios (SIRs) for all SMNs combined and for breast, thyroid, endometrial, and renal cancers were calculated.

Results

Of the 2,912 adult patients included in our analysis, 2,024 had an invasive cancer history. Germline pathogenic PTEN mutations (PTEN mutation positive) were identified in 114 patients (5.6%). Of these 114 patients, 46 (40%) had an SMN. Median age of SMN diagnosis was 50 years (range, 21 to 71 years). Median interval between primary cancer and SMN was 5 years (range, < 1 to 35 years). Of the 51 PTEN mutation–positive patients who presented with primary breast cancer, 11 (22%) had a subsequent new primary breast cancer and 10-year second breast cancer cumulative risk of 29% (95% CI, 15.3 to 43.7). Risk of SMNs compared with that of the general population was significantly elevated for all cancers (SIR, 7.74; 95% CI, 5.84 to 10.07), specifically for breast (SIR, 8.92; 95% CI, 5.85 to 13.07), thyroid (SIR, 5.83; 95% CI, 3.01 to 10.18), and endometrial SMNs (SIR, 14.08.07; 95% CI, 7.10 to 27.21).

Conclusion

Patients with CS with germline PTEN mutations are at higher risk for SMNs compared with the general population. Prophylactic mastectomy should be considered on an individual basis given the significant risk of subsequent breast cancer.

INTRODUCTION

Improvements in detecting cancer at earlier stages and advances in treatment have yielded an increase in the proportion of living individuals ever diagnosed with cancer. Second malignant neoplasms (SMNs) now comprise approximately 18% of all incident cancers in the United States,1 superseding first cancers of the breast, lung, and prostate. The rising importance of SMNs among cancer survivors has led to the identification of SMNs as one of the provocative questions of the National Cancer Institute1 and an emerging area of research. Increases in the rate of SMNs mirror advances in cancer survival and paradoxically reflect the successes derived from early detection and improvements in treatment and supportive care. It is expected that the number of patients with subsequent and higher-order malignancies will increase. This highlights the need for a greater understanding of the determinants of SMNs, which include environmental determinants (eg, tobacco and excessive alcohol intake), host factors, genetic predisposition, and combinations of these influences, and how they interact with one another.

The contribution of genetics to the etiology of SMNs is complex and characterized by the penetrance of individual genetic variants. Individuals with a deleterious high-penetrance mutation have an excessive risk of additional primary cancers (of same or different type). After a primary breast cancer diagnosis, patients with deleterious BRCA1/2 mutations are at significantly increased lifetime risk of developing ovarian2 and breast cancers.3 For all hereditary cancer predisposition syndromes, such insight allows health care providers to facilitate early SMN diagnosis and identify patients who may benefit from intervention to reduce the risk of SMNs.

Cowden syndrome (CS) and related syndromes characterized by germline mutations in the PTEN tumor suppressor gene are collectively known as PTEN hamartoma tumor syndromes (PHTSs).4,5 Clinical criteria for CS are based on guidelines developed by the International Cowden Consortium,6,7 subsequently adopted by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), and include pathognomonic, major, and minor criteria (Appendix Table A1, online only).8 CS is an autosomal-dominant disorder characterized by the development of multiple hamartomas and, importantly, carcinomas of the thyroid, breast, endometrium, and kidney.5,9 In a recent large prospective study, we confirmed and quantified that germline mutations in PTEN increased the risk of epithelial thyroid cancer by more than 70-fold when compared with that of the general population4 and increased lifetime risk of breast (85%), uterine (28%), and renal cancers (33%).5 Although it is clear that patients with PHTSs are at increased risk of certain cancers, the risk of developing an SMN is unclear for the individual patient, as is which CS-related cancers for which he or she would be at higher risk. Hence, the overall objective of our study was to evaluate the risk of SMNs in patients with PHTSs compared with the general population, which can be used to further inform cancer surveillance strategies.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Population

A total of 3,515 research participants were prospectively accrued and provided informed consent for Cleveland Clinic (CC) Institutional Review Board Protocol No. 8458-PTEN. Probands who met at least the relaxed International Cowden Consortium operational criteria for CS were eligible (Appendix Table A1, online only). Relaxed criteria are defined as full criteria minus one criterion; individuals meeting relaxed criteria are referred to as having CS-like disease. Patients were recruited from both community and academic medical centers throughout North America, South America, Europe, Australia, and Asia. For each patient, the medical record was examined by cancer genetics professionals, and when possible, primary documentation of medical records and pathology reports was obtained for confirmation of the primary cancer, SMNs, and precise histology, with patient consent. Of the 3,515 patients enrolled, 52 did not undergo PTEN testing, and 547 were age < 18 years at study enrollment. For the purposes of this analysis of adult-onset cancers, we limited our study to patients who were age ≥ 18 years at the time of enrollment (N = 2,916). For all patients, a semiquantitative score—the CC score based on clinical features—was calculated. The CC score has been shown to provide a well-calibrated estimation of pretest probability of PTEN status.10

PTEN Mutation and Deletion Analysis

All research participants underwent PTEN (NM 000314.4) mutation analysis. Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral-blood leukocytes using standard methods.11 Scanning of genomic DNA samples for PTEN mutations was performed as previously reported with a combination of denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis, high-resolution melting curve analysis (Idaho Technology, Salt Lake City, UT), and direct Sanger sequencing (ABI 3730xl; Life Techonologies, Carlsbad, CA).12 Deletion analysis using the multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification assay13 was performed with the P158 multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification kit (MRC-Holland, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) according to manufacturer protocol. All patients underwent polymerase chain reaction–based Sanger sequencing of the PTEN promoter region (primer sequences listed in Appendix Table A2, online only) as previously described.14 Nonsynonymous missense, frameshift, splice-site, and nonsense mutations as well as large deletions and whole-gene deletion were assigned PTEN mutation–positive status. All intronic and synonymous mutations were classified as variants of unknown significance and considered mutation negative. Prediction databases, three-dimensional structural modeling, and downstream protein readouts10 were used to assist missense mutation annotations.14–17 Unless the specific PTEN promoter mutations were shown to affect PTEN function14 and to be associated with CS phenotypes,5,18 to be conservative, we considered them here as mutation negative.

Follow-Up Procedures

For all patients who were diagnosed with an underlying germline PTEN mutation, we abstracted recorded baseline information from medical records on diagnosis as well as detailed cancer history. In addition, any SMNs diagnosed and, specifically, any information regarding thyroidectomy, mastectomy, or hysterectomy through August 2013 were obtained by trained interviewers through telephone interviews with PHTS survivors or through updated information received from patients or medical providers. Invasive SMNs were confirmed by pathologic reports whenever possible or by hospital or physician records. We excluded all in situ cancers, benign tumors, and nonmelanoma skin cancers from this analysis. We excluded metastases as well as synchronous cancers of the same histology if they occurred within 6 months of the primary cancer diagnosis. Bilateral breast cancers were considered as separate primaries, if so determined after clinical review. All confirmed cancers were coded according to the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology.19

Statistical Analysis

Accrual of person-years of follow-up began 6 months after primary cancer diagnosis and ended on date of SMN diagnosis, date of surgical procedure including prophylactic surgeries (eg, hysterectomy, mastectomy, thyroidectomy), date of death, or date last known alive, whichever occurred first. Standardized incidence ratios (SIRs) and 95% CIs for all SMNs combined and for the four most common CS-related cancers (ie, breast, thyroid, endometrial, and renal cancers) were calculated. We compared the observed number of cancers to the expected number of SMNs based on the age-, sex-, and 5 year (calendar year) –specific US incidence rates from the SEER program from 1973 onward, not adjusted for race or ethnicity. Comparisons of SIRs were based on the χ2 test of homogeneity.20 Excess absolute risk (EAR) per 10,000 person-years, which measures the absolute burden of disease, was determined by calculating the difference in expected and observed numbers of cancers. SIRs and EAR were calculated using SEER*Stat software (version 8.0.4; http://www.seer.cancer.gov/seerstat). Cumulative incidence for all SMNs combined and second CS-related cancers combined was calculated by decade up to three decades after diagnosis of first primary cancer. Statistical tests were two sided, with P ≤ .05 considered significant. All analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 19.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Of the 2,916 adult patients included in our analysis, 2,024 had a cancer history and were included for subsequent analyses. Germline PTEN mutations were seen in 114 patients with an invasive cancer history (5.6%). Table 1 lists selected demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with PHTSs with one primary cancer (68 of 114; 59.6%) and those with SMNs (46 of 114; 40.4%). Characteristics of patients with one primary cancer were compared with those of patients with SMNs. There was no difference in age at primary cancer diagnosis between patients with PHTSs with one cancer versus those with SMNs (41 v 44 years; P = .66). Median age at SMN diagnosis was 50 years (range, 21 to 71 years). Women with PHTSs were more likely to have SMNs (42 of 91 v four of 23; P = .02). Table 2 lists the primary and subsequent cancers of patients with PHTSs with SMNs, along with the specific PTEN mutations and intervals between first and second cancers.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients With PHTSs With Primary Cancer and SMNs

| Variable | PHTS With ≥ Two Cancers (n = 46) |

PHTS With One Cancer (n = 68) |

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | ||

| Age at first cancer diagnosis, years | .66 | ||||

| Median | 43.5 | 40.5 | |||

| Range | 7-66 | 9-69 | |||

| Sex | .02 | ||||

| Male | 4 | 9 | 19 | 28 | |

| Female | 42 | 91 | 49 | 72 | |

| CC score | .39 | ||||

| Median | 20.5 | 27 | |||

| Range | 4-55 | 1-69 | |||

| First primary cancer | |||||

| Breast | 18 | 39 | 21 | 31 | .42 |

| Thyroid | 10 | 22 | 23 | 34 | .21 |

| Endometrial | 11 | 24 | 5 | 7 | .03 |

| Renal | 2 | 4 | 6 | 9 | .47 |

| Other | 5 | 11 | 13 | 19 | .27 |

Abbreviations: CC, Cleveland Clinic; PHTS, PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome; SMN, second malignant neoplasm.

Table 2.

Clinical Characteristics of Patients With PHTSs With SMNs

| Patient ID No. | Sex | CC Score | Age (years) |

Type of Cancer |

Interval From Primary Cancer to SMN (years) | PTEN Mutation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Enrollment | Primary Cancer Diagnosis | Primary | Second | Subsequent | |||||

| 5482 | F | 14 | 57 | 48 | Breast | Breast | Endometrial | 3 | c.277C>T p.(His93Tyr) |

| 5580 | F | 24 | 54 | 50 | Breast | Breast | Ovarian | 2 | c.388C>T p.(Arg130*) |

| 5355 | F | 13 | 57 | 39 | Breast | Breast | Thyroid | 10 | c.388C>T p.(Arg130*) |

| 9242 | F | 14 | 59 | 54 | Breast | Breast | Thyroid | < 1 | c.517C>T p.(Arg173Cys) |

| 1432 | F | 16 | 42 | 44 | Breast | Breast | < 1 | c.388C>G p.(Arg130Gly) | |

| 2844 | F | 28 | 60 | 54 | Breast | Breast | 6 | c.209 + 1G>T | |

| 5822 | F | 17 | 56 | 32 | Breast | Breast | 13 | c.80-?_164+?del | |

| 7274 | F | 18 | 72 | 48 | Breast | Breast | 23 | c.389G>A p.(Arg130Gln) | |

| 8171 | F | 14 | 59 | 50 | Breast | Breast | 8 | c.238A>T p.(Lys80Ter) | |

| 9358 | F | 15 | 61 | 61 | Breast | Breast | 1 | c.696dupA p.(Thr233fs) | |

| 1216 | F | 37 | 39 | 29 | Breast | Ovarian | 17 | c.389G>A p.(Arg130Gln) | |

| 7155 | F | 31 | 64 | 46 | Breast | Endometrial | Renal, breast | 3 | c.70G>C p.(Asp24His) |

| 590 | F | 15 | 51 | 51 | Breast | Endometrial | < 1 | c.388C>T p.(Arg130*) | |

| 3910 | F | 17 | 57 | 36 | Breast | Endometrial | 5 | c.1033C>G p.(Leu345Val) | |

| 7082 | F | 22 | 56 | 49 | Breast | Endometrial | 7 | c.71A>G p.(Asp24Gly) | |

| 9513 | F | 14 | 70 | 65 | Breast | Endometrial | 3 | c.46T>C p.(Tyr16His) | |

| 5928 | F | 42 | 49 | 43 | Breast | Small intestine | 6 | c.210-4_210-1delTTAG | |

| 6243 | F | 4 | 57 | 50 | Breast | Thyroid | 5 | -834C>T | |

| 3944 | F | 14 | 49 | 47 | Colorectal | Breast | 2 | c.182A>G p.(His61Arg) | |

| 5151 | F | 46 | 54 | 35 | Colorectal | Endometrial | Breast | 18 | c.697C>T p.(Arg233*) |

| 7112 | F | 41 | 51 | 47 | Endometrial | Breast | 1 | c.883_884insT p.(Cys296Metfs*2) | |

| 8008 | F | 29 | 51 | 49 | Endometrial | Breast | < 1 | c.323T>C p.(Leu108Pro) | |

| 8370 | F | 16 | 58 | 47 | Endometrial | Breast | 11 | c.672dupA p.(Tyr225fs) | |

| 10402 | F | 66 | 66 | 31 | Endometrial | Breast | 35 | c.160_162del3 | |

| 3015 | F | 16 | 47 | 43 | Endometrial | Colorectal | 4 | c.720C>A p.(Tyr240*) | |

| 5760 | F | 45 | 49 | 34 | Endometrial | Melanoma | Thyroid | 7 | c.72_73insAGA p.(Asp24_Leu25insArg) |

| 7851 | F | 32 | 38 | 30 | Endometrial | Renal | Breast | 2 | c.388C>T p.(Arg130*) |

| 10071 | F | 22 | 59 | 46 | Endometrial | Renal | Ovarian | 8 | c.79T>A p.(Tyr27Asn) |

| 1186 | F | 25 | 43 | 34 | Endometrial | Renal | 16 | c.1027-2A>C | |

| 1716 | F | 38 | 61 | 61 | Endometrial | Renal | < 1 | c.388C>T p.(Arg130*) | |

| 5191 | F | 46 | 41 | 38 | Endometrial | Thyroid | 3 | c.734_737del4 p.(Gln245Argfs*10) | |

| 7764 | F | 31 | 50 | 32 | Melanoma | Endometrial | Breast | 17 | c.491delA p.(Lys164Argfs*3) |

| 342 | M | 55 | 51 | 26 | Melanoma | Renal | 25 | c.388C>T p.(Arg130*) | |

| 8743 | M | 43 | 54 | 49 | Renal | Colorectal | 4 | c.164 + 1G>T | |

| 1365 | F | 19 | 50 | 45 | Renal | Melanoma | 11 | c.1003C>T p.(Arg335*) | |

| 10077 | F | 10 | 40 | 21 | Thyroid | Bladder | 20 | c.389G>T p.(Arg130Leu) | |

| 1343 | F | 10 | 59 | 46 | Thyroid | Breast | 11 | c.203A>G p.(Tyr68Cys) | |

| 4566 | F | 19 | 41 | 35 | Thyroid | Breast | 3 | c.324delT p.(Asp109Thrfs*4) | |

| 6797 | F | 18 | 45 | 42 | Thyroid | Breast | 2 | c.697C>T p.(Arg233*) | |

| 1554 | M | 18 | 73 | 41 | Thyroid | Colorectal | 5 | c.633C>A p.(Cys211*) | |

| 435 | F | 19 | 52 | 33 | Thyroid | Endometrial | Breast | 13 | c.406T>C p.(Cys136Arg) |

| 7292 | F | 45 | 21 | 17 | Thyroid | Endometrial | Ovarian | 4 | c.509G>T p.(Ser170Ile) |

| 1084 | F | 16 | 26 | 26 | Thyroid | Ovarian | < 1 | c.655C>T p.(Q219*) | |

| 1352 | M | 23 | 26 | 7 | Thyroid | Renal | 14 | c.491delA p.(Lys164Argfs*3) | |

| 5350 | F | 17 | 44 | 36 | Thyroid | Renal | 8 | c.1003C>T p.(Arg335*) | |

| 1688 | F | 27 | 39 | 19 | Hodgkin lymphoma | Breast | 11 | c.1003C>T p.(Arg335*) | |

Abbreviations: CC, Cleveland Clinic; PHTS, PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome; SMN, second malignant neoplasm.

SIRs and EAR

Excluding nonmelanoma skin cancer, the risk of SMNs compared with general population rates revealed significantly elevated SIRs for patients with PHTSs for all SMNs combined (SIR, 7.74; 95% CI, 5.84 to 10.07). Similarly, increased risks of breast (SIR, 8.92; 95% CI, 5.85 to 13.07), thyroid (SIR, 5.83; 95% CI, 3.01 to 10.18), endometrial (SIR, 14.08.07; 95% CI, 7.10 to 27.21), and renal SMNs (SIR, 4.09; 95% CI, 0.49 to 14.76) were also seen. SMN melanoma (SIR, 7.41; 95% CI, 1.24 to 24.47) and colon cancer (SIR, 6.20; 95% CI, 1.28 to 18.11) risks were also higher than those of the general population. The EAR for all combined SMNs was 364 per 10,000 person-years; the EAR was 430 per 10,000 person-years for breast cancer, 235 per 10,000 person-years for thyroid cancer, 617 per 10,000 person-years for uterine cancer, and 310 per 10,000 person-years for renal cancer (Table 3).

Table 3.

Risk of Second Malignancy in Patients With PHTSs Compared With General Population

| Type of Cancer | No. of Cancers |

SIR | 95% CI | EAR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | Expected* | ||||

| All | 52 | 6.72 | 7.74† | 5.84 to 10.07 | 364 |

| Breast | 24 | 2.69 | 8.92† | 5.85 to 13.07 | 430 |

| Thyroid | 12 | 2.06 | 5.83† | 3.01 to 10.18 | 235 |

| Uterine | 10 | 0.68 | 14.80 | 7.10 to 27.21 | 617† |

| Renal | 2 | 0.49 | 4.09 | 0.49 to 14.76 | 310† |

| Melanoma | 2 | 0.27 | 7.41 | 1.24 to 24.47 | 344† |

| Colon | 3 | 0.48 | 6.20 | 1.28 to 18.11 | 319† |

Abbreviations: EAR, excess absolute risk per 10,000 person-years; PHTS, PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome; SIR, standardized incidence ratio.

Using data from SEER*Stat.

P < .05.

Age-Related Penetrance Curves for SMNs in PHTSs

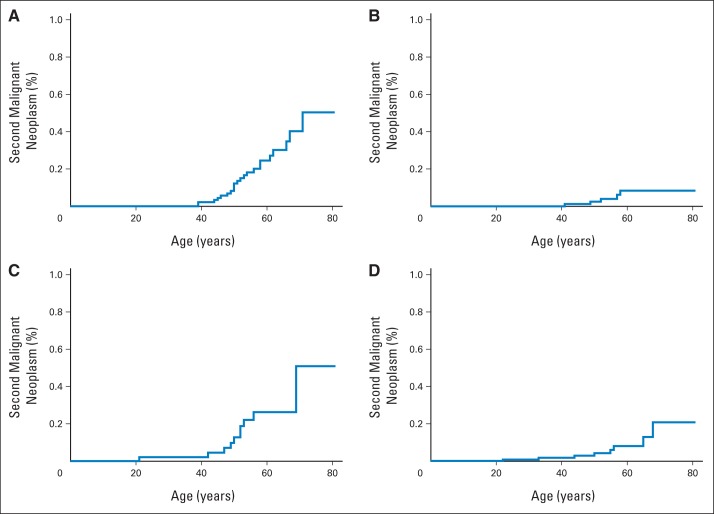

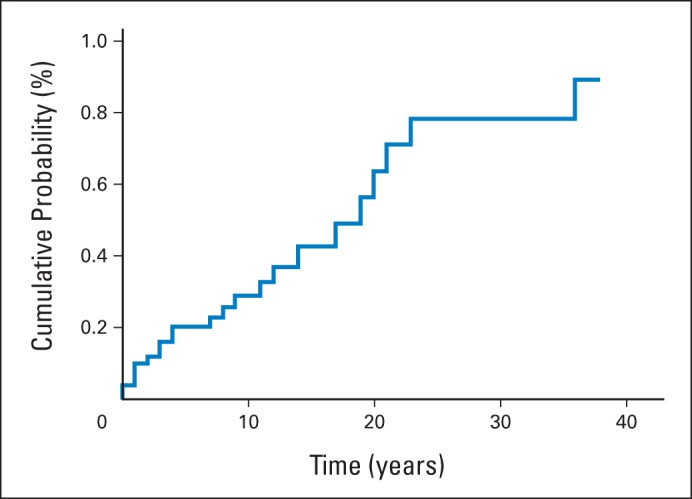

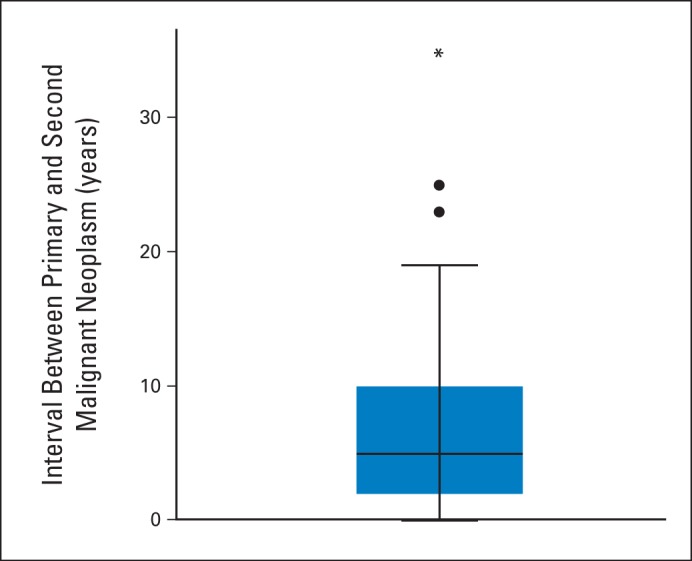

There were no significant differences in interval time from a primary cancer to subsequent specific CS-related cancer types. Median interval to second cancer was 5 years (Appendix Fig A1, online only). Age-related penetrance curves for CS-related SMNs after surviving a primary cancer are shown in Figures 1A to 1D. Fifty-one patients with PHTSs presented with breast cancer, of whom 11 (22%) had a second breast primary; median age at second breast primary was 52 years (range, 39 to 71 years). The 10-year cumulative risk of breast SMN after first breast cancer was estimated to be 29% (95% CI, 15.3 to 43.7; Fig 2).

Fig 1.

Age-related penetrance curves of (A) female breast, (B) thyroid, (C) endometrial, and (D) renal cancers presenting as second malignant neoplasms (SMNs) in patients with PTEN hamartoma tumor syndromes. Highest age-related penetrance was observed in female breast SMN, with estimated 59% lifetime risk after any primary cancer.

Fig 2.

Cumulative risk of breast second malignant neoplasm after first breast cancer in patients with PTEN hamartoma tumor syndromes.

DISCUSSION

Given the protean nature of CS and lack of familiarity among clinicians in recognizing CS, the true prevalence of PHTSs is likely to be higher than the commonly reported one in 200,000 and may account for some of the SMNs seen in the population. Clinicians should consider the possibility of PHTSs in patients who have multiple primary cancers involving thyroid, renal, breast, or endometrial cancer or melanoma. Adult patients with PHTSs had a seven-fold increased risk of an SMN compared with the US general population. This is the first report, to our knowledge, to estimate risk for SMNs by presence of germline PTEN mutations (inherited or de novo). As expected, SIRs compared with those of the general population were significantly elevated for three of the most common CS-related cancers (breast, thyroid, and endometrial cancers). The interval between first and second cancers ranged from 0 (synchronous) to 35 years, with a median of 5 years. These insights, although not unexpected, provide information that is important for future studies and cancer surveillance strategies.

It is important to note that 22% of patients with PHTSs who had a primary breast cancer proceeded to develop a subsequent breast cancer, with a 10-year cumulative risk of 29% from the time of primary breast cancer. This finding may have implications for the surgical management of patients with PHTSs at the initial presentation of breast cancer. Our group demonstrated in 201210 a much higher estimated lifetime risk of female breast cancer (85%) relative to the traditional estimates of 25% to 50% that had previously been used for clinical risk discussion and counseling.21 Our findings were subsequently confirmed by two other groups, which also found the lifetime risk for breast cancer to be 85%.22,23 Benign breast disease commonly affects up to 67% of those with PHTSs, often affecting one or both breasts extensively.10 This makes breast imaging a challenge. Managing these lesions is further complicated by the cosmetically unpleasant scars some patients develop after biopsy or lumpectomy. These challenges are unique to patients with PHTSs; although increased surveillance is universally recommended, prophylactic mastectomy should be discussed on an individual basis.

The interval between primary cancer and SMN is also important because it is common for so-called imaging fatigue to set in for patients. PHTSs are a protean disease, and unfortunately, at present, there are neither good clinical nor molecular correlates to help refine current surveillance recommendations (Table 4).5 Knowing that the median interval time to onset of an invasive SMN is 5 years (but interval can be as long as up to 35 years) will enable care providers to give previously unavailable information to patients with regard to the importance of continued compliance with screening recommendations.

Table 4.

Screening Recommendations for Patients With PHTSs

| Cancer | General Population Risk (%) | Lifetime Risk With PHTSs (%) | Average Age at Diagnosis (years) | Screening |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast | 12 | Approximately 85 | 40-49 | Starting at age 30 years: annual mammogram; consider MRI for patients with dense breasts |

| Thyroid | 1 | 35 | 30-49 | Annual ultrasound |

| Endometrial | 2.6 | 28 | 40-59 | Starting at age 30 years: annual endometrial biopsy or transvaginal ultrasound |

| Renal cell | 1.6 | 34 | 50-59 | Starting at age 40 years: renal imaging every 2 years |

| Colon | 5 | 9 | 40-49 | Starting at age 35 years: colonoscopy every 2 years |

| Melanoma | 2 | 6 | 40-49 | Annual dermatologic examination |

Abbreviations: MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PHTS, PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome.

Reflecting the increasing focus of the oncology community on SMNs, a number of population-based studies and review articles exploring SMNs have been published, many within the last 2 years.24–29 Although early studies focused largely on SMNs related to therapy, such as radiotherapy-related SMNs, increasingly, the interest has expanded to include a deeper understanding for why SMNs occur within certain subpopulations. A common theme that is seen in many population-based studies is the propensity for SMNs before or after thyroid cancer,24–26 commonly occurring with renal, melanoma, and breast cancers. The bidirectional association between thyroid and other cancers is not completely understood. This is most striking among male patients with thyroid cancer, who had a 29- and 4.5-fold increase in prevalence of subsequent breast and renal cancers, respectively. Male patients with breast or renal cancer had an increased prevalence of thyroid caner of 19- and three-fold, respectively.25 Unidirectional associations are more likely to result from cancer treatment effects (eg, breast cancer after radiotherapy for Hodgkin lymphoma), but a bidirectional association would suggest a shared genetic or shared genetic and environmental risk factors. Here, our data show that in at least a minority of these cases, the reason lies with an underlying germline PTEN mutation.

The lack of overall awareness regarding germline PTEN mutation status and thyroid cancer is reflected in our present data. Of the 33 patients with PHTSs who presented with thyroid cancer, 10 (30%) were seen for genetic assessment only after a second cancer diagnosis. Our group has shown that follicular thyroid cancer (FTC) and male thyroid cancer are overrepresented in patients with PHTSs. Although the prevalence of germline PTEN mutations among those with differentiated thyroid cancer is low (< 1%), in unselected patient cases of FTC, germline PTEN mutation frequency was 4.8%.30 We would advise that clinicians be vigilant when seeing patients with thyroid cancer. In addition to the two red flags we have described (ie, male sex and FTC), clinicians should look specifically for additional clinical clues suggestive of CS (Appendix Table A1, online only), such as an enlarged head circumference4,30 or pediatric age of onset. Of the PTEN mutation–positive patients included in this study, five had pediatric onset cancers, all of which were thyroid (age range, 7 to 17 years). This is in keeping with our published work and our recommendation that patients with a germline PTEN mutation receive baseline thyroid imaging and examination at the time of PTEN mutation detection. No patient had an SMN before age 18 years.

As with all inherited cancer syndromes to date, although we can counsel increased prevalence of specific cancers, we cannot predict which subset of those with PTEN mutations will develop each component cancer. A weakness this study is that given the rarity of the disease, we do not have a sufficient sample size to adequately address which host or exposure factors affect the prevalence of SMNs in patients with germline PTEN mutations. High-penetrance mutations in cancer susceptibility genes make only a small contribution to population SMN burden, because of their low frequency. For most individuals, the prevailing model is defined by the cumulative effect of multiple low- and intermediate-penetrance risk alleles for cancer, where each individual genetic variant confers a modest increase in risk, but which, collectively, increase risk substantially when coinherited in an individual.31,32 It is therefore equally likely that such multigenic models influence cancer risk in patients with germline PTEN mutations. Indeed, we found that 6% of PTEN mutation/variant–positive patients with CS also had germline SDHx variants, and presence of SDHx variants seems to further modify PTEN-mutation breast cancer risk over PTEN mutation in isolation.33 It is our hope that with increased sample size, we will identify subsets of patients who are particularly susceptible to SMNs and those who instead present with noncancer phenotypes (eg, neurodevelopmental), allowing for targeted research.

A key strength of this study was the longitudinal data we had on our PHTS survivors on both SMNs as well as surgical procedures since study enrollment. Prophylactic surgical procedures as well as extent of surgery (eg, total v partial thyroidectomies) would certainly reduce the incidence of subsequent cancers in the organs removed and otherwise lead to an underestimation of the observed cancers. Other limitations include possible selection and lead times bias in patients with PHTSs undergoing active cancer surveillance after diagnosis of PHTSs. Although this could potentially lead to an overestimation of SMNs and a shortened interval between primary cancer and SMN, it is worth noting that the majority of patients with PHTSs in our series had an SMN before their PHTS diagnosis (45 of 46 patients; Table 2). Indeed, reflecting clinical practice, it is often the occurrence of SMNs that prompt clinicians to refer patients for genetic testing and diagnose PHTSs. From a clinical perspective, it is more important to note that PHTSs are too often diagnosed only after a second malignancy, which may reflect the overall diagnostic challenge that PHTSs pose for treating oncologists. Our study, the largest prospective series in the literature to our knowledge, will continue longitudinal follow-up for research participants to validate our current findings and better determine the impact of cancer surveillance on incidence and outcomes of SMNs.

These data provide new clinical information for patients with PHTSs, their family members, and their health care providers on the risk of SMNs. If the high incidence of a subsequent breast primary in patients with PHTSs presenting with breast cancer is validated, this suggests that prophylactic mastectomy should be a consideration for some patients. The latter is particularly germane because the breasts of some patients with PHTSs are difficult to screen given their propensity for development of multiple benign breast pathologies.

Acknowledgment

We thank all our research participants and their clinicians who contributed to this study and the Genomic Medicine Biorepository of the Cleveland Clinic Genomic Medicine Institute as well as our database and clinical research coordination teams for their meticulous upkeep and auditing of the clinical databases.

Appendix

Table A1.

Clinical Operational Diagnostic Criteria for CS

| Criteria |

|---|

| Pathognomonic |

| Adult LDD (cerebellar tumors) |

| Mucocutaneous lesions |

| Trichilemmomas, facial |

| Acral keratoses |

| Papillomatous papules |

| Mucosal lesions |

| Major |

| Breast cancer |

| Thyroid cancer (nonmedullary) |

| Macrocephaly (megalocephaly; ie, ≥ 97th percentile) |

| Endometrial cancer |

| Minor |

| Other thyroid lesions (eg, adenoma, multinodular goiter) |

| Mental retardation (ie, IQ ≤ 75) |

| GI hamartomas |

| Fibrocystic breast disease |

| Lipomas |

| Fibromas |

| Genitourinary tumors (especially renal cell carcinoma) |

| Genitourinary malformations |

| Uterine fibroids |

| Operational diagnosis in individual |

| Any of following: |

| Mucocutaneous lesions alone, if ≥ six facial papules (three of which must be trichilemmomas) |

| Cutaneous facial papules and oral mucosal papillomatosis |

| Oral mucosal papillomatosis and acral keratoses |

| ≥ Six plamoplatar keratoses |

| ≥ Two major criteria (one of which must be macrocephaly or LDD) |

| One major and ≥ three minor criteria |

| ≥ Four minor criteria |

| Operational diagnosis in family where one individual is diagnostic for CS |

| Any one pathognomonic criterion |

| Any one major criteria ± minor criteria |

| Two minor criteria |

| History of Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome |

Abbreviations: CS, Cowden syndrome; LDD, Lhermitte-Duclos disease.

Table A2.

PTEN Light Scanner Primers and Annealing Temperatures

| Name | Sequence 5′ → 3′ | Annealing Temperature (°C) |

|---|---|---|

| PTEN LS E1F | GCAGCTTCTGCCATCTC | 66 |

| PTEN LS E1R | GCATCCGTCTACTCCCAC | |

| PTEN LS E2F | AGTATTCTTTTAGTTTGATTGCTGC | 60 |

| PTEN LS E2R | CTAAATGAAAACACAACATGAATATAAACA | |

| PTEN LS E3F | ATGTTAGCTCATTTTTGTTAATGGTG | 60 |

| PTEN LS E3R | CAAGCAGATAACTTTCACTTAATAGTTG | |

| PTEN LS E4F | TTTTTTCTTCCTAAGTGCAAAAGATAAC | 60 |

| PTEN LS E4R | CAGTAAGATACAGTCTATCGGGT | |

| PTEN LS E5F | ACCTACTTGTTAATTAAAAATTCAAGAGTT | 60 |

| PTEN LS E5R | ATCCAGGAAGAGGAAAGGAAA | |

| PTEN LS E5SeqF | TGCAACATTTCTAAAGTTACCTACTTG | |

| PTEN LS E6F | CCCAGTTACCATAGCAATTTAGTGA | 60 |

| PTEN LS E6R | TAGATATGGTTAAGAAAACTGTTCCAATAC | |

| PTEN LS E7F | CAGTTTGACAGTTAAAGGCATTTC | 61 |

| PTEN LS E7R | AATATAGCTTTTAATCTGTCCTTATTTTGG | |

| PTEN LS E8.1F | TTTGTTGACTTTTTGCAAATGTTTAACATA | 61 |

| PTEN LS E8.1R | ATTTCTTGATCACATAGACTTCCA | |

| PTEN LS E8.2F | GTAAATACATTCTTCATACCAGGACC | 61 |

| PTEN LS E8.2R | GCTGTACTCCTAGAATTAAACACAC | |

| PTEN LS E9F | AAGATGAGTCATATTTGTGGGTT | 61 |

| PTEN LS E9R | TTTCAGTTTATTCAAGTTTATTTTCATGG | |

| PTEN LS E9SeqF | AGATGAGTCATATTTGTGGGTTTT | For sequencing |

| PTEN LS E9SeqR | AAAGGTCCATTTTCAGTTTATTCAA | For sequencing |

| PTEN LS SNP E8.2F | GCAAATAAAGACAAAGCCAACCGA | 60 |

| PTEN LS SNP E8.2R | AGCTGTACTCCTAGAATTAAACACACATC | For intronic 8 SNP |

| PTEN LS SNP E8.2 probe | CATACAAGTCACCAACCCCCAC-block |

Abbreviations: LS, light scanner; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism.

Fig A1.

Interval from primary cancer diagnosis to second malignant neoplasm for patients with PTEN hamartoma tumor syndromes (n = 46); median interval, 5 years.

Footnotes

Listen to the podcast by Dr Stratakis at www.jco.org/podcasts

Supported in part by Grants No. P01CA124570 and R01CA118980 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI; C.E.) and by Case Comprehensive Cancer Center Support Grant No. NCI 5P30 CA043703 (J.S.B.-S.). J.L.M. is Ambrose Monell Foundation Cancer Genomic Medicine Clinical Fellow at the Cleveland Clinic Genomic Medicine Institute. C.E is Sondra J. and Stephen R. Hardis Chair of Cancer Genomic Medicine at the Cleveland Clinic and American Cancer Society Clinical Research Professor, funded in part by the F.M. Kirby Foundation.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Joanne Ngeow, Charis Eng

Collection and assembly of data: All authors

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

REFERENCES

- 1.National Cancer Institute. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2007. http://seer.cancer.gov/archive/csr/1975_2007.

- 2.Metcalfe KA, Lynch HT, Ghadirian P, et al. The risk of ovarian cancer after breast cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;96:222–226. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rhiem K, Engel C, Graeser M, et al. The risk of contralateral breast cancer in patients from BRCA1/2 negative high risk families as compared to patients from BRCA1 or BRCA2 positive families: A retrospective cohort study. Breast Cancer Res. 2012;14:R156. doi: 10.1186/bcr3369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ngeow J, Mester J, Rybicki LA, et al. Incidence and clinical characteristics of thyroid cancer in prospective series of individuals with Cowden and Cowden-like syndrome characterized by germline PTEN, SDH, or KLLN alterations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:E2063–E2071. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tan MH, Mester JL, Ngeow J, et al. Lifetime cancer risks in individuals with germline PTENmutations. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:400–407. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eng C. Will the real Cowden syndrome please stand up: Revised diagnostic criteria. J Med Genet. 2000;37:828–830. doi: 10.1136/jmg.37.11.828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pilarski R, Eng C. Will the real Cowden syndrome please stand up (again)? Expanding mutational and clinical spectra of the PTEN hamartoma tumour syndrome. J Med Genet. 2004;41:323–326. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.018036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daly MB, Axilbund JE, Buys S, et al. Genetic/familial high-risk assessment: Breast and ovarian. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010;8:562–594. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2010.0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mester JL, Zhou M, Prescott N, et al. Papillary renal cell carcinoma is associated with PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome. Urology. 2012;79:1187.e1–1187.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tan MH, Mester J, Peterson C, et al. A clinical scoring system for selection of patients for PTEN mutation testing is proposed on the basis of a prospective study of 3042 probands. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88:42–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eng C, Thiele H, Zhou XP, et al. PTEN mutations and Proteus syndrome. Lancet. 2001;358:2079–2080. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)07110-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van der Stoep N, van Paridon CD, Janssens T, et al. Diagnostic guidelines for high-resolution melting curve (HRM) analysis: An interlaboratory validation of BRCA1 mutation scanning using the 96-well LightScanner. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:899–909. doi: 10.1002/humu.21004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schouten JP, McElgunn CJ, Waaijer R, et al. Relative quantification of 40 nucleic acid sequences by multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:e57. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnf056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teresi RE, Zbuk KM, Pezzolesi MG, et al. Cowden syndrome-affected patients with PTEN promoter mutations demonstrate abnormal protein translation. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:756–767. doi: 10.1086/521051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moorman NJ, Shenk T. Rapamycin-resistant mTORC1 kinase activity is required for herpesvirus replication. J Virol. 2010;84:5260–5269. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02733-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lang SA, Hackl C, Moser C, et al. Implication of RICTOR in the mTOR inhibitor-mediated induction of insulin-like growth factor-I receptor (IGF-IR) and human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (Her2) expression in gastrointestinal cancer cells. Biochim Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1803:435–442. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moss SC, Lightell DJ, Jr, Marx SO, et al. Rapamycin regulates endothelial cell migration through regulation of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27Kip1. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:11991–11997. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.066621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Y, Romigh T, He X, et al. Differential regulation of PTEN expression by androgen receptor in prostate and breast cancers. Oncogene. 2011;30:4327–4338. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Percy C, Fritz A, Jack A, et al. International Classification of Disease for Oncology: ICD-O (ed 3) Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Breslow NE, Day NE. Statistical methods in cancer research: Volume II—The design and analysis of cohort studies. IARC Sci Publ. 1987;82:1–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hobert JA, Eng C. PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome: An overview. Genet Med. 2009;11:687–694. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181ac9aea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bubien V, Bonnet F, Brouste V, et al. High cumulative risks of cancer in patients with PTEN hamartoma tumour syndrome. J Med Genet. 2013;50:255–263. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-101339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nieuwenhuis MH, Kets CM, Murphy-Ryan M, et al. Cancer risk and genotype-phenotype correlations in PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome. Fam Cancer. doi: 10.1007/s10689-013-9674-3. [epub ahead of print on August 11, 2013] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayat MJ, Howlader N, Reichman ME, et al. Cancer statistics, trends, and multiple primary cancer analyses from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. Oncologist. 2007;12:20–37. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-1-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van Fossen VL, Wilhelm SM, Eaton JL, et al. Association of thyroid, breast and renal cell cancer: A population-based study of the prevalence of second malignancies. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:1341–1347. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2718-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lal G, Groff M, Howe JR, et al. Risk of subsequent primary thyroid cancer after another malignancy: Latency trends in a population-based study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:1887–1896. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-2193-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nielsen SF, Nordestgaard BG, Bojesen SE. Associations between first and second primary cancers: A population-based study. CMAJ. 2012;184:E57–E69. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.110167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ng AK, Kenney LB, Gilbert ES, et al. Secondary malignancies across the age spectrum. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2010;20:67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Travis LB, Demark Wahnefried W, Allan JM, et al. Aetiology, genetics and prevention of secondary neoplasms in adult cancer survivors. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2013;10:289–301. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2013.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nagy R, Ganapathi S, Comeras I, et al. Frequency of germline PTEN mutations in differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2011;21:505–510. doi: 10.1089/thy.2010.0365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peto J. Breast cancer susceptibility: A new look at an old model. Cancer Cell. 2002;1:411–412. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pharoah PD, Antoniou A, Bobrow M, et al. Polygenic susceptibility to breast cancer and implications for prevention. Nat Genet. 2002;31:33–36. doi: 10.1038/ng853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ni Y, He X, Chen J, et al. Germline SDHx variants modify breast and thyroid cancer risks in Cowden and Cowden-like syndrome via FAD/NAD-dependant destabilization of p53. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:300–310. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]