Abstract

Purpose

This guideline presents screening, assessment, and treatment approaches for the management of adult cancer survivors who are experiencing symptoms of fatigue after completion of primary treatment.

Methods

A systematic search of clinical practice guideline databases, guideline developer Web sites, and published health literature identified the pan-Canadian guideline on screening, assessment, and care of cancer-related fatigue in adults with cancer, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Clinical Practice Guidelines In Oncology (NCCN Guidelines) for Cancer-Related Fatigue and the NCCN Guidelines for Survivorship. These three guidelines were appraised and selected for adaptation.

Results

It is recommended that all patients with cancer be evaluated for the presence of fatigue after completion of primary treatment and be offered specific information and strategies for fatigue management. For those who report moderate to severe fatigue, comprehensive assessment should be conducted, and medical and treatable contributing factors should be addressed. In terms of treatment strategies, evidence indicates that physical activity interventions, psychosocial interventions, and mind-body interventions may reduce cancer-related fatigue in post-treatment patients. There is limited evidence for use of psychostimulants in the management of fatigue in patients who are disease free after active treatment.

Conclusion

Fatigue is prevalent in cancer survivors and often causes significant disruption in functioning and quality of life. Regular screening, assessment, and education and appropriate treatment of fatigue are important in managing this distressing symptom. Given the multiple factors contributing to post-treatment fatigue, interventions should be tailored to each patient's specific needs. In particular, a number of nonpharmacologic treatment approaches have demonstrated efficacy in cancer survivors.

INTRODUCTION

Recent advances in cancer screening and treatment have resulted in an expanding number of cancer survivors. The American Cancer Society estimates that as of January 2012, there were 13.7 million cancer survivors in the United States, and this number is estimated to rise to nearly 18 million by 2022.1 The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) has taken steps to address the recommendations made by the Institute of Medicine (IOM)2 to promote evidence-based, comprehensive, compassionate, and coordinated survivorship care.3–5 More specifically, the ASCO Cancer Survivorship Committee has mobilized to address recommendation three of the IOM, which calls for the “use of systematically developed evidence-based clinical practice guidelines, assessment tools, and screening instruments to help identify and manage late effects of cancer and its treatment. Existing guidelines should be refined and new evidence-based guidelines should be developed through public-and private-sector efforts.”2(p155) This guideline addresses one of a series of topics that have been identified and prioritized for development in cancer survivorship.

A majority of patients will experience some level of fatigue during their course of treatment; however, approximately 30% of patients will endure persistent fatigue for a number of years after treatment.6,7 Fatigue is one the most prevalent and distressing long-term effects of cancer treatment, significantly affecting patients' quality of life.6 The objective of this guideline is to identify evidence-based clinical practice guidelines, assessment tools, and screening instruments to help health care professionals care for survivors of adult-onset cancers who are experiencing symptoms of fatigue after completion of primary treatment.

THE BOTTOM LINE.

Guideline Question

What are the screening, assessment, and treatment approaches to the management of adult cancer survivors who are experiencing symptoms of fatigue after completion of primary treatment?

Target Population

This practice guideline pertains to cancer survivors diagnosed at age ≥ 18 years who have completed primary cancer treatment with curative intent and are in clinical remission off therapy as well as patients who are disease free and have transitioned to maintenance or adjuvant therapy (eg, patients with breast cancer receiving hormonal therapy, patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia receiving tyrosine kinase inhibitors).

Target Audience

This guidance is intended to inform health care professionals (eg, medical, surgical, and radiation oncologists, psychosocial and rehabilitation professionals, primary care providers, nurses, and others involved in the delivery of care for survivors) as well as patients, family members, and caregivers of patients who have survived cancer.

Recommendations

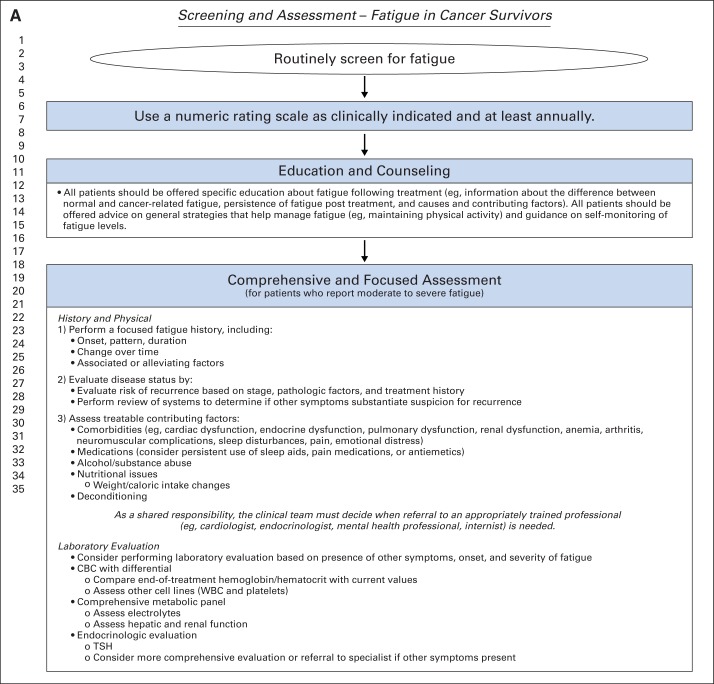

Screening

All health care providers should routinely screen for the presence of fatigue from the point of diagnosis onward, including after completion of primary treatment.

All patients should be screened for fatigue as clinically indicated and at least annually.

Screening should be performed and documented using a quantitative or semiquantitative assessment.

Comprehensive and Focused Assessment

History and Physical

Perform a focused fatigue history

Evaluate disease status

Assess treatable contributing factors.

As a shared responsibility, the clinical team must decide when referral to an appropriately trained professional (eg, cardiologist, endocrinologist, mental health professional, internist, and so on) is needed.

Laboratory Evaluation

Consider performing laboratory evaluation based on presence of other symptoms and onset and severity of fatigue.

Treatment and Care Options

Education and Counseling

All patients should be offered specific education about fatigue after treatment (eg, information about the difference between normal and cancer-related fatigue, persistence of fatigue after treatment, and causes and contributing factors).

Patients should be offered advice on general strategies that help manage fatigue.

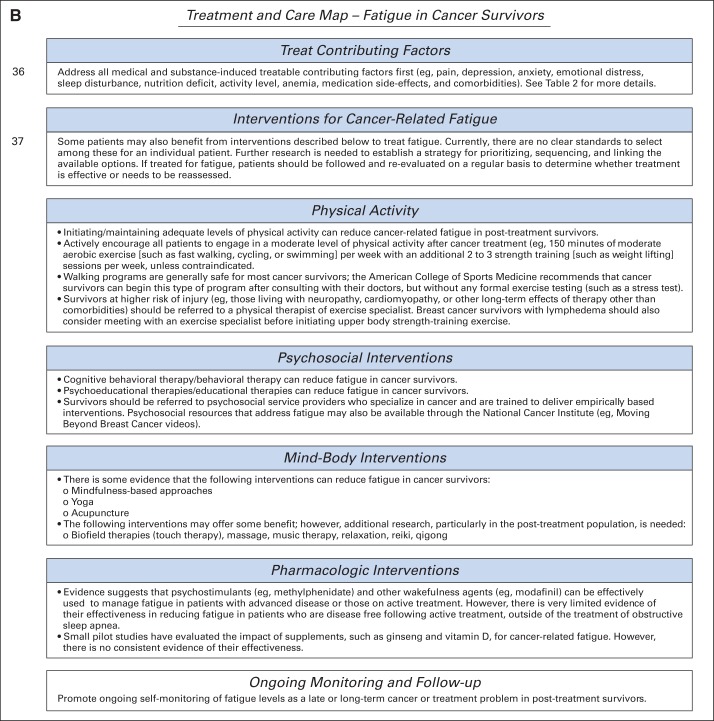

If treated for fatigue, patients should be observed and re-evaluated on a regular basis to determine whether treatment is effective or needs to be reassessed.

Contributing Factors

Address all medical and treatable contributing factors first (eg, pain, depression, anxiety, emotional distress, sleep disturbance, nutritional deficit, activity level, anemia, medication adverse effects, and comorbidities).

Physical Activity

Initiating/maintaining adequate levels of physical activity can reduce cancer-related fatigue in post-treatment survivors.

Actively encourage all patients to engage in a moderate level of physical activity after cancer treatment (eg, 150 minutes of moderate aerobic exercise [such as fast walking, cycling, or swimming] per week with an additional two to three strength training [such as weight lifting] sessions per week, unless contraindicated).

Walking programs are generally safe for most cancer survivors; the American College of Sports Medicine recommends that cancer survivors can begin this type of program after consulting with their physicians but without any formal exercise testing (such as a stress test).

Survivors at higher risk of injury (eg, those living with neuropathy, cardiomyopathy, or other long-term effects of therapy) and patients with severe fatigue interfering with function should be referred to a physical therapist or exercise specialist. Breast cancer survivors with lymphedema should also consider meeting with an exercise specialist before initiating upper-body strength training.

Psychosocial Interventions

Cognitive behavioral therapy/behavioral therapy can reduce cancer-related fatigue in post-treatment survivors.

Psychoeducational therapies/educational therapies can reduce cancer-related fatigue in post-treatment survivors.

Survivors should be referred to psychosocial service providers who specialize in cancer and are trained to deliver empirically based interventions. Psychosocial resources that address fatigue may also be available through the National Cancer Institute and other organizations.

Mind-Body Interventions

There is some evidence that mindfulness-based approaches, yoga, and acupuncture can reduce fatigue in cancer survivors.

Additional research, particularly in the post-treatment population, is needed for biofield therapies (touch therapy), massage, music therapy, relaxation, reiki, and qigong.

Survivors should be referred to practitioners who specialize in cancer and who use protocols that have been empirically validated in cancer survivors.

Pharmacologic Interventions

Evidence suggests that psychostimulants (eg, methylphenidate) and other wakefulness agents (eg, modafinil) can be effectively used to manage fatigue in patients with advanced disease or those receiving active treatment. However, there is limited evidence of their effectiveness in reducing fatigue in patients after active treatment who are currently disease free.

Small pilot studies have evaluated the impact of supplements, such as ginseng, vitamin D, and others, on cancer-related fatigue. However, there is no consistent evidence of their effectiveness.

ASCO has established a process for adapting other organizations' clinical practice guidelines. This article summarizes the results of that process and presents the adapted practice recommendations.

The clinical question of focus is: What are the optimal screening, assessment, and treatment approaches in the management of adult cancer survivors who are experiencing symptoms of fatigue after completion of primary treatment? This practice guideline pertains to cancer survivors diagnosed at age ≥ 18 years who have completed primary cancer treatment with curative intent and are in clinical remission off therapy as well as patients who are disease free and have transitioned to maintenance or prophylactic therapy (eg, patients with breast cancer receiving hormonal therapy, patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia receiving tyrosine kinase inhibitors). This guidance is intended to inform professional health care providers (eg, medical, surgical, and radiation oncologists, psychosocial and rehabilitation professionals, primary care providers, nurses, and others involved in the delivery of care for survivors) as well as patients, family members, and caregivers of patients who have survived cancer.

METHODS

This guideline adaptation was informed by the ADAPTE methodology,8 which was used as an alternative to de novo guideline development for this guideline. Adaptation of guidelines is considered by ASCO in selected circumstances, when one or more quality guidelines from other organizations already exist on the same topic. The objective of the ADAPTE process (http://www.adapte.org/) is to take advantage of existing guidelines to enhance efficient production, reduce duplication, and promote the local uptake of quality guideline recommendations.

The ASCO adaptation process begins with a literature search to identify candidate guidelines for adaptation. Adapted guideline manuscripts are reviewed and approved by the ASCO Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee (CPGC). The review includes two parts: methodologic review and content review. The methodologic review is completed by a member of the CPGC Methodology Subcommittee and/or by ASCO senior guideline staff. The content review is completed by an ad hoc panel (Appendix Table A1, online only), with guidance from an advisory group (Appendix Table A2, online only), convened by ASCO that includes multidisciplinary representation. Additional details on the methods used for the development of this guideline are reported in a Data Supplement.

Disclaimer

The information contained in this article, including but not limited to clinical practice guidelines and other guidance, is based on the best available evidence at the time of creation and is provided by ASCO to assist providers in clinical decision making. The information should not be relied on as being complete or accurate, nor should it be considered as inclusive of all proper treatments or methods of care or as a statement of the standard of care. With the rapid development of scientific knowledge, new evidence may emerge between the time information is developed and when it is published or read. The information is not continually updated and may not reflect the most recent evidence. The information addresses only the topics specifically identified herein and is not applicable to other interventions, diseases, or stages of diseases. This information does not mandate any particular product or course of medical treatment. Furthermore, the information is not intended to substitute for the independent professional judgment of the treating provider, because the information does not account for individual variation among patients. Recommendations reflect high, moderate, or low confidence that the recommendation reflects the net effect of a given course of action. The use of words like must, must not, should, and should not indicate that a course of action is recommended or not recommended for either most or many patients, but there is latitude for the treating physician to select other courses of action in certain cases. In all cases, the selected course of action should be considered by the treating provider in the context of treating the individual patient. Use of the information is voluntary. ASCO provides this information on an as is basis and makes no warranty, express or implied, regarding the information. ASCO specifically disclaims any warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular use or purpose. ASCO assumes no responsibility for any injury or damage to persons or property arising out of or related to any use of this information or for any errors or omissions.

Guideline and Conflicts of Interest

The expert panel was assembled in accordance with the ASCO Conflicts of Interest Management Procedures for Clinical Practice Guidelines (summarized at http://www.asco.org/guidelinescoi). Members of the panel completed the ASCO disclosure form, which requires disclosure of financial and other interests that are relevant to the subject matter of the guideline, including relationships with commercial entities that are reasonably likely to experience direct regulatory or commercial impact as the result of promulgation of the guideline. Categories for disclosure include employment relationships, consulting arrangements, stock ownership, honoraria, research funding, and expert testimony. In accordance with these procedures, the majority of the members of the panel did not disclose any such relationships.

RESULTS

GUIDELINE SEARCH AND ASCO PANEL CONTENT REVIEW

As mentioned, the adaptation process starts with a literature search to identify candidate guidelines for adaptation on a given topic. The systematic search of clinical practice guideline databases, guideline developer Web sites, and published health literature was conducted to identify clinical practice guidelines, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and other guidance documents addressing the screening, assessment, and care of cancer-related fatigue (see the Data Supplement on www.asco.org/guidelines for details of the search). On the basis of content review of the search yield, the ad hoc panel selected the pan-Canadian guideline on fatigue published in 2011,9 which is informed by recommendations from the Oncology Nursing Society10 and National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN).11 The panel also considered two NCCN Guidelines12,13 that had been created or updated since 2009. These guidelines were selected because they were comprehensive and recently developed by multidisciplinary panels of experts.

Overview of Pan-Canadian and NCCN Guidelines

Clinical questions and target populations.

The pan-Canadian guideline9 describes assessment after screening and effective interventions for management of fatigue in adults with cancer who are identified as experiencing symptoms of fatigue or tiredness using the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS; further information on ESAS can be found in pan-Canadian guideline9). This practice guideline pertains to adults with cancer at any phase of the cancer continuum, regardless of cancer type, disease stage, or treatment modality. This practice guideline is intended to inform Canadian health authorities, program leaders, and administrators as well as health care professionals who provide care to adults with cancer. The guideline is interprofessional in focus, and the recommendations are applicable to direct-care providers (eg, nurses, social workers, family practitioners) in diverse care settings.

The NCCN Guideline for Cancer-Related Fatigue12 describes procedures for the assessment and management of fatigue in patients with cancer. The target population includes children, adolescents, and adults, and the guideline is intended to provide guidance for health care professionals as they implement it in their respective institutions and clinical practice. The NCCN Guideline for Survivorship13 consists of screening, evaluation, and treatment recommendations for common consequences of cancer and cancer treatment. The target population for this guideline is survivors who have completed treatment and are in clinical remission. It is intended for health care professionals who work with survivors of adult-onset cancer in the post-treatment period.

Summary of development methodology and key evidence of pan-Canadian and NCCN guidelines.

The pan-Canadian guideline9 used systematic methods to search for evidence and clearly describes the strengths and limitations of the body of evidence and the methods used for formulating recommendations. The NCCN guidelines12,13 represent a consensus of experts; they are based on evidence, well respected, and widely used, and as such, they were included as supplementary evidence. All three guidelines offer comprehensive and user-friendly algorithms helpful in informing screening, assessment, and treatment options.

ASCO METHODOLOGIC REVIEW

From the identified guidelines and reviews, the pan-Canadian guideline on screening, assessment, and care of cancer-related fatigue in adults with cancer9 was singled out and underwent an expedited review by two content experts, who suggested that the guideline be accepted with modifications. After a second review, the ASCO panel suggested that the more recent NCCN Guideline for Cancer-Related Fatigue12 and NCCN Guideline for Survivorship13 also be included in the adaptation. A methodologic review of the three guidelines was completed by two ASCO staff members using the Rigour of Development subscale of the AGREE II (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II) instrument14 (www.agreecollaboration.org). The Rigour of Development subscale consists of seven items that assess the quality of processes used to gather and synthesize relevant data and methods used to formulate guideline recommendations (Data Supplement; detailed results of scoring for this guideline are available on request to guidelines@asco.org). Briefly, the pan-Canadian guideline9 received a score of 86.5%, the NCCN Guideline for Cancer-Related Fatigue12 received a score of 47%, and the NCCN Guideline for Survivorship13 received a score of 44%.

ASCO UPDATED LITERATURE SEARCH

Because the literature search included in the pan-Canadian guideline was only current to 2009, an additional search was undertaken. The MEDLINE and EMBASE databases were systematically searched by one reviewer from January 2009 to March 2013 using a combination of the following search terms: fatigue, cancer, survivor, post-treatment, late effects, and long-term effects. Reference lists of reviews were also extensively searched for studies on fatigue in the cancer survivor population. The located meta-analyses, systematic reviews, and randomized controlled trials were used as a supplementary evidence base for the recommendations and are cited where appropriate in the text.

FINAL RECOMMENDATIONS

The recommendations were adapted from the three guidelines (original recommendation matrix provided in Data Supplement) by a multidisciplinary group of experts using evidence from the supplementary literature search and clinical experience as a guide. The majority of the recommendation text is listed verbatim from the three guidelines; however, there are some instances where the ASCO expert panel made modifications or additions to the recommendations to reflect local context, practice beliefs, and updated empiric evidence. These changes are identified with the words “modified from” preceding the guideline title after each subsection heading. Figure 1 presents a two-page screening, assessment, treatment, and care map algorithm for fatigue adapted from the pan-Canadian guideline. Copyright permission for the adaption was obtained from the authors of the pan-Canadian and NCCN guidelines.

Fig 1.

Screening and assessment of fatigue in cancer survivors. CBC, complete blood cell count; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone. Data adapted with permission.9 Treatment and care map for fatigue in cancer survivors. Data adapted with permission.9

DEFINITION

Modified from NCCN Guideline for Cancer-Related Fatigue and NCCN Guideline for Survivorship.

Cancer-related fatigue is a distressing, persistent, subjective sense of physical, emotional, and/or cognitive tiredness or exhaustion related to cancer and/or cancer treatment that is not proportional to recent activity and interferes with usual functioning. These guidelines are focused on fatigue in patients who have completed primary cancer treatment and/or are in clinical remission.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Screening

Modified from pan-Canadian guideline and NCCN Guideline for Cancer-Related Fatigue.

All health care providers should routinely screen for the presence of fatigue from the point of diagnosis onward, including after completion of primary treatment.

All patients should be screened for fatigue as clinically indicated and at least annually.

Screening should be performed and documented using a quantitative or semiquantitative assessment. For example, on a 0 to 10 numeric rating scale (0, no fatigue; 10, worst fatigue imaginable), mild fatigue is indicated as a score of 1 to 3, moderate fatigue as 4 to 6, and severe fatigue as 7 to 10.15,16 Because fatigue is rarely an isolated symptom, a multisymptom screening tool may have greater clinical utility. Patients who report moderate to severe fatigue should undergo a comprehensive and focused assessment.

Table 1 lists selected instruments for the measurement of fatigue, which could be used to supplement initial screening with the 0 to 10 numeric scale.

Table 1.

Selected Instruments Used to Measure Cancer-Related Fatigue17

| Scale | Description |

|---|---|

| Unidimensional* | |

| FACT-F18 | 13-item standalone questionnaire that is part of larger FACIT series of quality-of-life and tumor-specific symptom questionnaires |

| Studied in mixed cancer population | |

| Dimension: severity | |

| EORTC QLQ C3019 | 30-item quality-of-life questionnaire with three-item fatigue subscale (independently validated as separate fatigue measure) |

| Psychometric properties weaker than more extensive scales, but it is brief and easy to use | |

| Independently assessed in lung cancer, bone marrow transplantation, and metastatic cancer | |

| Dimension: severity | |

| POMS-F20 | 65-item questionnaire with seven-item fatigue subscale |

| Assessed in both noncancer and cancer populations | |

| Has defined minimum clinically significant difference | |

| Dimension: severity | |

| Multidimensional† | |

| BFI15 | Nine-item numeric scale |

| Validated for use in mixed cancer population | |

| Reasonable psychometric properties but limited ongoing use | |

| Cutoff scores to differentiate between mild, medium, and severe fatigue, but it has not been validated and is likely to be of use for screening purposes only | |

| Dimensions: severity and interference | |

| Chalder Fatigue Scale (also called FQ)21 | 11-item scale |

| Validated in general practice setting but widely used for chronic fatigue syndrome | |

| Brief and easy to administer | |

| Dimensions: physical and mental | |

| FSI22 | 13-item scale |

| Validated in breast cancer population and mixed cancers | |

| Reasonable psychometric properties, but there is some concern regarding its test/retest reliability | |

| Dimensions: severity, duration, and interference | |

| MFI-2023 | 20-item scale |

| Designed for use in patients with cancer | |

| Validated in Army trainees and physicians undertaking shift work as well as in patients with cancer | |

| Dimensions: general fatigue, physical fatigue, mental fatigue, reduced motivation, and reduced activity | |

| MFSI-3024 | 30-item scale |

| Investigated in patients with breast cancer undergoing treatment and in mixed cancer population | |

| Favorable psychometric properties | |

| Dimensions: general fatigue, physical fatigue, emotional fatigue, mental fatigue, and vigor | |

| Revised Piper Fatigue Scale25 | 22-item revised version of original scale |

| Validated in breast cancer survivors | |

| Dimensions: behavioral, severity, affective meaning, sensory, cognitive/mood | |

| Schwartz Cancer Fatigue Scale26 | 28-item scale |

| Validated in mixed cancer population undergoing treatment | |

| Psychometric properties examined in mixed cancer population | |

| Limited use; hence, its usefulness despite extensive psychometric data must therefore be questioned | |

| Dimensions: total score and physical and perceptual subscores |

Abbreviations: BFI, Brief Fatigue Inventory; EORTC QLQ C30, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality-of-Life Questionnaire Core 30; FACIT, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy; FACT-F, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Fatigue; FQ, Fatigue Questionnaire; FSI, Fatigue Symptom Inventory; MFI-20, 20-item Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory; MFSI-30, Multidimensional Fatigue Symptom Inventory 30-item short form; POMS-F, Profile of Mood States–Fatigue.

Tend to measure physical impact of fatigue.

Tend to measure cognitive or affective symptoms.

Comprehensive and Focused Assessment

Modified from NCCN Guideline for Survivorship.

Regarding history and physical, first, perform a focused fatigue history, including:

Onset, pattern, and duration.

Change over time.

Associated or alleviating factors.

Second, evaluate disease status by:

Evaluating risk of recurrence based on stage, pathologic factors, and treatment history.

Performing a review of systems to determine if other symptoms substantiate suspicion for recurrence.

Third, assess treatable contributing factors, including:

Comorbidities (Table 2).

Medications (consider persistent use of sleep aids, pain medications, or antiemetics).

Alcohol/substance abuse.

Nutritional issues (including weight/caloric intake changes).

Decreased functional status.

Deconditioning/decreased activity level.

As a shared responsibility, the clinical team must decide when referral to an appropriately trained professional (eg, cardiologist, endocrinologist, mental health professional, internist, and so on) is needed.

Table 2.

Potential Comorbid Conditions and Other Treatable Contributing Factors Possibly Associated With Fatigue Symptoms

| Treatable Contributing Factor | Examples of Possible Diagnostic Evaluation* |

|---|---|

| Cardiac dysfunction (eg, arrhythmia, hypertension, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure) | Consider echocardiogram, exercise test for cardiopulmonary reserve |

| Endocrine dysfunction (eg, diabetes, hypothyroidism, hypogonadism, adrenal insufficiency) | Consider measuring HgbA1C, TSH, glucose, and testosterone, conduct dexamethasone suppression test |

| Pulmonary dysfunction | Consider chest x-ray, 6-minute walk test, pulmonary function tests, oxygen saturation |

| Renal dysfunction | Consider kidney and electrolyte chemistries |

| Anemia | Consider CBC |

| Arthritis | Consider sedimentation rate, serologies |

| Neuromuscular complications (neuromuscular, neuropathy) | Consider grip strength test, neuropathy sensory testing, electromyography |

| Sleep disturbances (eg, insomnia, sleep apnea, vasomotor symptoms, restless leg syndrome) | Consider assessing sleep with standardized questionnaire, possible sleep study |

| Pain | Evaluate with standardized assessment tool |

| Emotional distress (eg, anxiety, depression) | Evaluate with standardized assessment tool or diagnostic interview |

NOTE. This list is not meant to be exhaustive. Data adapted.13

Abbreviations: CBC, complete blood cell count; HgbA1C, hemoglobin A1C; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone.

Should be undertaken only when clinically appropriate.

Laboratory Evaluation

NCCN Guideline for Survivorship verbatim.

Consider performing laboratory evaluation based on presence of other symptoms, onset, and severity of fatigue.

Complete blood cell count with differential: compare end-of-treatment hemoglobin/hematocrit with current values; assess other cell lines (WBC and platelets).

Comprehensive metabolic panel: assess electrolytes; assess hepatic and renal function.

Endocrinologic evaluation: TSH [thyroid-stimulating hormone]; consider more comprehensive evaluation or referral to specialist if other symptoms present.

Treatment and Care Options

Modified from pan-Canadian guideline and NCCN Guideline for Cancer-Related Fatigue.

Regarding education and counseling:

All patients should be offered specific education about fatigue after treatment (eg, information about the difference between normal and cancer-related fatigue, persistence of fatigue after treatment, and causes and contributing factors).

Patients should be offered advice on general strategies that help manage fatigue (eg, physical activity, guidance on self-monitoring of fatigue levels).

If treated for fatigue, patients should be observed and re-evaluated on a regular basis to determine whether treatment is effective or needs to be reassessed.

Treatment of Contributing Factors

Modified from pan-Canadian guideline and NCCN Guideline for Survivorship.

Address all medical and substance-induced treatable contributing factors first (eg, comorbidities, medications, nutritional issues, activity level). Table 2 provides more details. Some patients can also benefit from interventions described in this article to treat fatigue. Currently, there are no clear standards for selecting among these to treat an individual patient. Further research is needed to establish a strategy for prioritizing, sequencing, and linking the available options.

Physical Activity

Modified from pan-Canadian guideline and NCCN Guideline for Survivorship.

Several meta-analyses, systematic reviews, and randomized trials27–36 have demonstrated that initiating or maintaining adequate levels of physical activity can reduce cancer-related fatigue in post-treatment patients. For example, a recent meta-analysis of 27 exercise intervention trials conducted with patients after treatment completion found that exercise training significantly reduced fatigue, with a mean effect size of 0.38 (95% CI, 0.21 to 0.43).27

Actively encourage all patients to engage in a moderate level of physical activity after cancer treatment (eg, 150 minutes of moderate aerobic exercise, such as fast walking, cycling, or swimming, per week with an additional two to three sessions per week of strength training, such as weight lifting, unless contraindicated).27–31

Walking programs are generally safe for most cancer survivors; the American College of Sports Medicine recommends that cancer survivors begin this type of program after consulting with their physician but without any formal exercise testing (such as a stress test).30

Survivors at higher risk of injury (eg, those living with neuropathy, cardiomyopathy, or other long-term effects of therapy other than comorbidities) should be referred to a physical therapist or exercise specialist. Breast cancer survivors with lymphedema should also consider meeting with an exercise specialist before initiating upper-body strength training.

Encourage survivors to make use of empirically based programs and local resources that are consistent with guideline recommendations. For patients with severe fatigue interfering with function, consider referral to a physical therapist or physiatrist.

Common barriers to physical activity in cancer survivors include physical and disease-related limitations (eg, illness, pain, fatigue, weakness) as well as lack of time, lack of interest/motivation, lack of facilities, and lack of encouragement from family or friends.37–40 To overcome these barriers, survivors should be encouraged to avoid inactivity by, at the minimum, engaging in exercises such as walking or using a stationary bicycle or cycle ergometer, beginning at an easy pace and progressing gradually to moderate intensity.41 Counseling and motivational interviewing have also been shown to encourage exercise adherence.41–43

Psychosocial Interventions

Modified from NCCN Guideline for Survivorship.

Several meta-analyses, systematic reviews, and randomized trials32,44–48 have indicated that cognitive behavioral therapy/behavioral therapy can reduce fatigue in cancer survivors. For example, a cognitive behavioral intervention that targeted dysfunctional thoughts about fatigue, poor coping strategies, and dysregulated sleep and activity patterns in a mixed sample of fatigued cancer survivors led to significant improvements in fatigue that were sustained over long-term follow-up.45

Several systematic reviews and randomized trials have suggested that psychoeducational/educational therapies may reduce fatigue in cancer survivors.32,48,49 For example, an Internet-based educational program that provided tailored information on cancer-related fatigue, physical activity, pain control, distress management, sleep hygiene, nutrition, and energy conservation led to significant improvements in fatigue in a mixed sample of fatigued cancer survivors.50

Survivors should be referred to psychosocial service providers specializing in cancer and trained to deliver empirically based interventions. Psychosocial resources that address fatigue may also be available through the National Cancer Institute (http://www.cancer.gov), the American Cancer Society (http://www.cancer.org), LIVESTRONG (http://www.livestrong.org), the Cancer Support Community (www.cancersupportcommunity.org), CancerCare (http://www.cancercare.org), Cancer.Net (http://www.cancer.net), and the American Psychosocial Oncology Society (http://www.apossociety.org/survivors/helpline/helpline.aspx).

Mind-Body Interventions

There is evidence from randomized trials that the following interventions may relieve fatigue in cancer survivors:

The following interventions may also offer some benefit57–61; however, additional research, particularly in the post-treatment period, is needed:

Biofield therapies (touch therapy), massage, music therapy, relaxation, reiki, and qigong.

Survivors should be referred to practitioners specializing in cancer and using protocols that have been empirically validated in cancer survivors.

Pharmacologic Interventions

Modified from NCCN Guideline for Cancer-Related Fatigue and NCCN Guideline for Survivorship.

Evidence suggests that psychostimulants (eg, methylphenidate) and other wakefulness agents (eg, modafinil) can be effectively used to manage fatigue in patients with advanced disease or those receiving active treatment.62–64 However, there is limited evidence of their effectiveness in reducing fatigue in patients who are disease free after active treatment, outside of the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea.65

Small pilot studies have evaluated the impact of supplements, such as ginseng and vitamin D, for cancer-related fatigue. However, there is no consistent evidence of their effectiveness.57

Ongoing Monitoring and Follow-Up

Promote ongoing self-monitoring of fatigue levels, using a symptoms diary or other methods, because fatigue can be a late or long-term problem in post-treatment survivors.

SPECIAL COMMENTARY

Although there are a number of guidelines and systematic reviews offering recommendations on the management of cancer-related fatigue, there is still relatively little guidance available for the management of fatigue in cancer survivors. The purpose of this guideline is to tailor the available information to this distinct population, because follow-up care for cancer survivors is often challenging, especially if they are dealing with comorbidities and receiving care from multiple providers. Patient follow-up and ongoing care should be individualized based on type of cancer, treatments received, overall health, and personal preferences. In many cases, the patient will be transitioned post-treatment to his or her primary care provider or a survivorship clinic. This transition may be eased with the use of survivorship care plans, which contain personalized information about the patient's treatment and follow-up plans (examples provided in ASCO templates at http://www.cancer.net/survivorship/asco-cancer-treatment-summaries). It is estimated that by 2022, the number of cancer survivors in the United States will exceed 18 million.1 Therefore, there is a need for greater coordination of care among oncologists and primary care providers, development of evidence-based resources, and ongoing research focusing on the survivor population as well as education, training, and clinical tools that will improve overall patient experience and well-being. The cornerstone of progress for the patient with cancer is the rapport established with his or her health care team. Open and engaging communication will assist both the patient and health care providers in assessing the patient's experience of fatigue and in determining an appropriate management strategy. ASCO believes that cancer clinical trials are vital to inform medical decisions and improve cancer care and that all patients should have the opportunity to participate.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Additional information, including data supplements, evidence tables, and clinical tools and resources, can be found at www.asco.org/guidelines/. Patient information is available there and at www.cancer.net. The complete adapted guideline can be accessed at http://www.capo.ca/Fatigue_Guideline.pdf and http://www.nccn.org.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Bryan Rumble for assisting with the methodologic guideline review; Tom Oliver and Mark Somerfield for administrative assistance; and the Survivorship Guideline Advisory Group, Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee (CPGC), and CPGC reviewers Jennifer Mack, MD, and Julia Rowland, PhD, for their thoughtful reviews and insightful comments on this guideline.

Appendix

Table A1.

Members of Fatigue Panel

| Panel Member | Institution |

|---|---|

| Julienne E. Bower, PhD (cochair), psychology | Departments of Psychology and Psychiatry/Biobehavioral Sciences, University of California at Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA |

| Paul B. Jacobsen, PhD (cochair), psychology | H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute, Tampa, FL |

| Ann Berger MSN, MD, pain and palliative care | National Institutes of Health Clinical Center, Bethesda, MD |

| William Breitbart, MD, psychiatry | Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY |

| Carmelita P. Escalante, MD, internal medicine | University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX |

| Patricia A. Ganz, MD, medical oncology | Schools of Medicine and Public Health, University of California at Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA |

| Hester Hill Schnipper, LICSW, BCD, patient representative, oncology social work | Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA |

| Jennifer A. Ligibel, MD, medical oncology | Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA |

| Gary H. Lyman, MD, MPH, FASCO, FRCP, medical oncology | Duke University and Duke Cancer Institute, Durham, NC |

| Mohammed S. Ogaily, MD, FACP, ASCO PGIN representative, medical oncology | Oakwood Center for Hematology and Oncology–Downriver, Brownstown, MI |

| William F. Pirl, MD, psychiatry | Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA |

| Kate Bak, MSc | ASCO, Alexandria, VA |

| Christina Lacchetti, MHSc | ASCO, Alexandria, VA |

Abbreviations: ASCO, American Society of Clinical Oncology; PGIN, Practice Guidelines Implementation Network.

Table A2.

Members of Survivorship Guideline Advisory Group

| Member | Institution |

|---|---|

| Gary Lyman (cochair) | Duke University and Duke Cancer Institute, Durham, NC |

| Smita Bhatia (cochair) | City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center, Duarte, CA |

| Louis S. Constine | University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY |

| Melissa M. Hudson | St Jude Childrens Research Hospital, Memphis, TN |

| Julia Howe Rowland | National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD/Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, DC |

| Kevin C. Oeffinger | Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY |

| Donna E. Maziak | The Ottawa Hospital, General Campus, Ottawa, ON |

| Larissa Nekhlyudov | Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA |

| Wendy Landier | City of Hope, Duarte, CA |

| Paul B. Jacobsen | H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute, Tampa, FL |

| Mark Gorman | Patient Representative, Silver Spring, MD |

| Anthony Magdalinski | ASCO PGIN; Abington Health Lansdale Hospital, Lansdale, PA; Doylestown Hospital, Doylestown, PA; Grand View Hospital, Sellersville, PA; St Lukes Quakertown Hospital, Quakertown, PA |

Abbreviations: ASCO, American Society of Clinical Oncology; PGIN, Practice Guidelines Implementation Network.

Footnotes

Editor's note: This American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline provides recommendations, with review and analysis of the relevant literature for each recommendation. Additional information, which may include data supplements, slide sets, patient versions, frequently asked questions, and clinical tools and resources, is available at www.asco.org/adaptations/fatigue.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

Clinical Practice Guideline Committee approval: July 29, 2013.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Although all authors completed the disclosure declaration, the following author(s) and/or an author's immediate family member(s) indicated a financial or other interest that is relevant to the subject matter under consideration in this article. Certain relationships marked with a “U” are those for which no compensation was received; those relationships marked with a “C” were compensated. For a detailed description of the disclosure categories, or for more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to the Author Disclosure Declaration and the Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest section in Information for Contributors.

Employment or Leadership Position: None Consultant or Advisory Role: None Stock Ownership: None Honoraria: None Research Funding: Carmelita P. Escalante, Pfizer; Patricia A. Ganz, Amgen; Gary Lyman, Amgen; Paul Jacobsen, Pfizer Expert Testimony: None Patents, Royalties, and Licenses: None Other Remuneration: None

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

REFERENCES

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer Treatment and Survivorship Facts and Figures 2012-2013. http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@epidemiologysurveilance/documents/document/acspc-033876.pdf.

- 2.Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E, editors. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rowland JH, Hewitt M, Ganz PA. Cancer survivorship: A new challenge in delivering quality cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5101–5104. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ganz PA, Earl CC, Goodwin PJ. Journal of Clinical Oncology update on progress in cancer survivorship care and research. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3655–3656. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.3886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCabe MS, Bhatia S, Oeffinger KC, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology statement: Achieving high-quality cancer survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;31:631–640. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.6854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bower JE, Ganz PA, Desmond KA, et al. Fatigue in breast cancer survivors: Occurrence, correlates, and impact on quality of life. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:743–753. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.4.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Servaes P, Verhagen S, Bleijenberg G. Determinants of chronic fatigue in disease-free breast cancer patients: A cross-sectional study. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:589–598. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.ADAPTE Collaboration. The ADAPTE process: Resource toolkit for guideline adaptation (version 2.0) http://www.g-i-n.net.

- 9.Howell D, Keller-Olaman S, Oliver TK, et al. A pan-Canadian practice guideline and algorithm: Screening, assessment and supportive care of adults with cancer-related fatigue. Curr Oncol. 2013;20:e233–e246. doi: 10.3747/co.20.1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mitchell SA, Beck SL, Hood LE, et al. Putting evidence into practice: Evidence-based interventions for fatigue during and following cancer and its treatment. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2007;11:99–113. doi: 10.1188/07.CJON.99-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Cancer-Related Fatigue (version 2.2009) www.nccn.org.

- 12.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Cancer-Related Fatigue (version 1.2013) www.nccn.org.

- 13.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Survivorship (version 1.2013) www.nccn.org.

- 14.Brouwers M, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. AGREE II: Advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in healthcare. CMAJ. 2010;182:E839–E842. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mendoza TR, Wang XS, Cleeland CS, et al. The rapid assessment of fatigue severity in cancer patients: Use of the Brief Fatigue Inventory. Cancer. 1999;85:1186–1196. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990301)85:5<1186::aid-cncr24>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nekolaichuk C, Watanabe S, Beaumont C. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System: A 15-year retrospective review of validation studies (1991-2006) Palliat Med. 2008;22:111–122. doi: 10.1177/0269216307087659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Minton O, Stone P. A systematic review of the scales used for the measurement of cancer-related fatigue (CRF) Ann Oncol. 2009;20:17–25. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yellen SB, Cella DF, Webster K, et al. Measuring fatigue and other anemia-related symptoms with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) measurement system. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;13:63–74. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(96)00274-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365–376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McNair DM, Lorr M. EITS Manual for the Profile of Mood States. San Diego, CA: Educational and Testing Service; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chalder T, Berelowitz G, Pawlikowska T, et al. Development of a fatigue scale. J Psychosom Res. 1993;37:147–153. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(93)90081-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hann DM, Jacobsen PB, Azzarello LM, et al. Measurement of fatigue in cancer patients: Development and validation of the Fatigue Symptom Inventory. Qual Life Res. 1998;7:301–310. doi: 10.1023/a:1024929829627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smets EM, Garssen B, Bonke B, et al. The Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI) psychometric qualities of an instrument to assess fatigue. J Psychosom Res. 1995;39:315–325. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(94)00125-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stein KD, Martin SC, Hann DM, et al. A multidimensional measure of fatigue for use with cancer patients. Cancer Pract. 1998;6:143–152. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.1998.006003143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Piper BF, Dibble SL, Dodd MJ, et al. The revised Piper Fatigue Scale: Psychometric evaluation in women with breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1998;25:677–684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwartz AL. The Schwartz Cancer Fatigue Scale: Testing reliability and validity. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1998;25:711–717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Puetz TW, Herring MP. Differential effects of exercise on cancer-related fatigue during and following treatment: A meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43:e1–e24. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McMillan EM, Newhouse IJ. Exercise is an effective treatment modality for reducing cancer-related fatigue and improving physical capacity in cancer patients and survivors: A meta-analysis. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2011;36:892–903. doi: 10.1139/h11-082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cramp F, Byron-Daniel J. Exercise for the management of cancer-related fatigue in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11:CD006145. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006145.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmitz KH, Courneya KS, Matthews C, et al. American College of Sports Medicine roundtable on exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42:1409–1426. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181e0c112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brown JC, Huedo-Medina TB, Pescatello LS, et al. Efficacy of exercise interventions in modulating cancer-related fatigue among adult cancer survivors: A meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:123–133. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duijts SF, Faber MM, Oldenburg HS, et al. Effectiveness of behavioral techniques and physical exercise on psychosocial functioning and health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients and survivors: A meta-analysis. Psychooncology. 2011;20:115–126. doi: 10.1002/pon.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saarto T, Penttinen HM, Sievänen H, et al. Effectiveness of a 12-month exercise program on physical performance and quality of life of breast cancer survivors. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:3875–3884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Winters-Stone KM, Dobek J, Bennett JA, et al. The effect of resistance training on muscle strength and physical function in older, postmenopausal breast cancer survivors: A randomized controlled trial. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6:189–199. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0210-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thorsen L, Courneya KS, Stevinson C, et al. A systematic review of physical activity in prostate cancer survivors: Outcomes, prevalence, and determinants. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16:987–997. doi: 10.1007/s00520-008-0411-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Speck RM, Courneya KS, Mâsse LC, et al. An update of controlled physical activity trials in cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4:87–100. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lynch BM, Owen N, Hawkes AL, et al. Perceived barriers to physical activity for colorectal cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18:729–734. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0705-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ottenbacher AJ, Day RS, Taylor WC, et al. Exercise among breast and prostate cancer survivors: What are their barriers? J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5:413–419. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0184-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Charlier C, Van Hoof E, Pauwels E, et al. The contribution of general and cancer-related variables in explaining physical activity in a breast cancer population 3 weeks to 6 months post-treatment. Psychooncology. 2013;22:203–211. doi: 10.1002/pon.2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blaney JM, Lowe-Strong A, Rankin-Watt J, et al. Cancer survivors' exercise barriers, facilitators and preferences in the context of fatigue, quality of life and physical activity participation: A questionnaire-survey. Psychooncology. 2013;22:186–194. doi: 10.1002/pon.2072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wolin KY, Schwartz AL, Matthews CE, et al. Implementing the exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. J Support Oncol. 2012;10:171–177. doi: 10.1016/j.suponc.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bennett JA, Lyons KS, Winters-Stone K, et al. Motivational interviewing to increase physical activity in long-term cancer survivors: A randomized controlled trial. Nurs Res. 2007;56:18–27. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200701000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ligibel JA, Meyerhardt J, Pierce JP, et al. Impact of a telephone-based physical activity intervention upon exercise behaviors and fitness in cancer survivors enrolled in a cooperative group setting. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;132:205–213. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1882-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van der Lee ML, Garssen B. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy reduces chronic cancer-related fatigue: A treatment study. Psychooncology. 2012;21:264–272. doi: 10.1002/pon.1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gielissen MF, Verhagen CA, Bleijenberg G. Cognitive behaviour therapy for fatigued cancer survivors: Long-term follow-up. Br J Cancer. 2007;97:612–618. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dirksen SR, Epstein DR. Efficacy of an insomnia intervention on fatigue, mood and quality of life in breast cancer survivors. J Adv Nurs. 2008;61:664–675. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jacobsen PB, Donovan KA, Vadaparampil ST, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of psychological and activity-based interventions for cancer-related fatigue. Health Psychol. 2007;26:660–667. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.6.660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kangas M, Bovbjerg DH, Montgomery GH, et al. Cancer-related fatigue: A systematic and meta-analytic review of non-pharmacological therapies for cancer patients. Psychol Bull. 2008;134:700–741. doi: 10.1037/a0012825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mitchell SA. Cancer-related fatigue: State of the science. PM R. 2010;2:364–383. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2010.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yun YH, Lee KS, Kim YW, et al. Web-based tailored education program for disease-free cancer survivors with cancer-related fatigue: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1296–1303. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.2979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lengacher CA, Reich RR, Post-White J, et al. Mindfulness based stress reduction in post-treatment breast cancer patients: An examination of symptoms and symptom clusters. J Behav Med. 2012;35:86–94. doi: 10.1007/s10865-011-9346-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hoffman CJ, Ersser SJ, Hopkinson JB, et al. Effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction in mood, breast- and endocrine-related quality of life, and well-being in stage 0 to III breast cancer: A randomized, controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1335–1342. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.0331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bower JE, Garet D, Sternlieb B, et al. Yoga for persistent fatigue in breast cancer survivors: A randomized controlled trial. Cancer. 2012;118:3766–3775. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Banasik J, Williams H, Haberman M, et al. Effect of Iyengar yoga practice on fatigue and diurnal salivary cortisol concentration in breast cancer survivors. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2011;23:135–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2010.00573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Johnston MF, Hays RD, Subramanian SK, et al. Patient education integrated with acupuncture for relief of cancer-related fatigue randomized controlled feasibility study. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2011;11:49. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-11-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Molassiotis A, Bardy J, Finnegan-John J, et al. Acupuncture for cancer related fatigue in patients with breast cancer: A pragmatic randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4470–4476. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.41.6222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Finnegan-John J, Molassiotis A, Richardson A, et al. A systematic review of complementary and alternative medicine interventions for the management of cancer-related fatigue. Integr Cancer Ther. 2013;12:276–290. doi: 10.1177/1534735413485816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fernández-Lao C, Cantarero-Villanueva I, Díaz-Rodríguez L, et al. Attitudes towards massage modify effects of manual therapy in breast cancer survivors: A randomised clinical trial with crossover design. Eur J Cancer Care. 2012;21:233–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2011.01306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jain S, Pavlik D, Distefan J, et al. Complementary medicine for fatigue and cortisol variability in breast cancer survivors: A randomized controlled trial. Cancer. 2012;118:777–787. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chuang CY, Han WR, Li PC, et al. Effects of music therapy on subjective sensations and heart rate variability in treated cancer survivors: A pilot study. Complement Ther Med. 2010;18:224–226. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Oh B, Butow P, Mullan B, et al. Impact of medical Qigong on quality of life, fatigue, mood and inflammation in cancer patients: A randomized controlled trial. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:608–614. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Minton O, Richardson A, Sharpe M, et al. Drug therapy for the management of cancer-related fatigue. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;7:CD006704. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006704.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fife K, Spathis A, Dutton SJ, et al. A multicenter, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial of modafinil for lung cancer-related fatigue: Dose response and patient satisfaction data. J Clin Oncol. 2013;(suppl 15):31. abstr 9503. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jean-Pierre P, Morrow GR, Roscoe JA, et al. A phase 3 randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, clinical trial of the effect of modafinil on cancer-related fatigue among 631 patients receiving chemotherapy. Cancer. 2010;116:3513–3520. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Santamaria J, Iranzo A, Ma Montserrat J, et al. Persistent sleepiness in CPAP treated obstructive sleep apnea patients: Evaluation and treatment. Sleep Med Rev. 2007;11:195–207. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.