Abstract

The management of primary and secondary radial nerve palsy associated with humeral shaft fractures is still controversial. Radial nerve function is likely to return spontaneously after primary as well as secondary radial nerve palsy in the absence of any level of neurotmesis. Identification and protection of the radial nerve during surgery may prevent secondary nerve palsy, but is not always performed and depends on the location of the fracture, and the experience and preference of the surgeon. We report a case of a healthy 40-year-old woman, referred to our hospital with a complete radial nerve palsy and a failed plate fixation of a right humeral shaft fracture. During exploration of the radial nerve and surgical revision of the fracture, we found the nerve entrapped by the plate and partially transected by a screw. Full recovery of radial nerve function occurred after neurolysis and microscopic neurorrhaphy.

Background

The incidence of radial nerve injury associated with a humeral shaft fracture is approximately 11.8%.1 While most (primary) radial nerve palsies are caused by spiral or oblique fractures of the junction between the middle and distal third of the humerus, iatrogenic (secondary) injury to the radial nerve may also occur during closed manipulations or at the time of surgical intervention using a compression plate or intramedullary nail.2 3

Most primary and secondary radial nerve palsies are probably caused by a compression or traction injury and fortunately the majority is transient with a full and spontaneous recovery of function within a median time of 6.6 months (range 3.4–12 months).4

Numerous reports discuss how to proceed if radial nerve palsy is diagnosed postoperatively after internal fixation of a humeral shaft fracture. So far there is no consensus. Based on the literature, Defranco and Lawton2 suggested early exploration because of the high frequency of nerve entrapment after internal fixation. In a recent study, Wang et al4 advocated observation for a minimum of 4 months before surgical exploration.

We describe an unusual course of events in a case with secondary radial nerve palsy after plating of a humeral shaft fracture.

Case presentation

A healthy, right-handed 40-year-old woman was referred to our hospital with a complete radial nerve palsy after plate fixation of a right humeral shaft fracture 2 months prior. Initially, the patient had presented with a closed fracture of the humerus without neurological deficits at the emergency department of another hospital (figure 1). Acute open reduction and internal fixation with a 3.5 mm. Locking Compression Plate (LCP, Synthes BV, Zeist, the Netherlands) was performed using a posterior approach under general anaesthesia. Postoperatively, the patient was noted to have a complete loss of radial motor and sensory function in the recovery room. A postoperative radiograph showed a suboptimal internal fixation of the plate (figure 2). Non-operative wait-and-see policy for the radial nerve deficit was advised by her surgeon. Six weeks later, the patient still experienced much pain and anxiety and consulted a hand therapist. A cock-up splint was provided, the initial surgeon was contacted and the patient was referred for a second opinion to our hospital.

Figure 1.

Fracture of the right humeral shaft.

Figure 2.

Radiograph showing suboptimal internal fixation 2 days postoperatively.

Investigations

During the past 2 months there were no signs of nerve function recovery. In addition, an obvious failure of the internal fixation showed on radiographs taken 2 months postoperatively (figure 3). When we contacted the surgeon who had operated on her, stated that he had not explored, nor seen the radial nerve during surgery.

Figure 3.

Radiograph showing the failed fixation at 2 months postoperatively.

Treatment

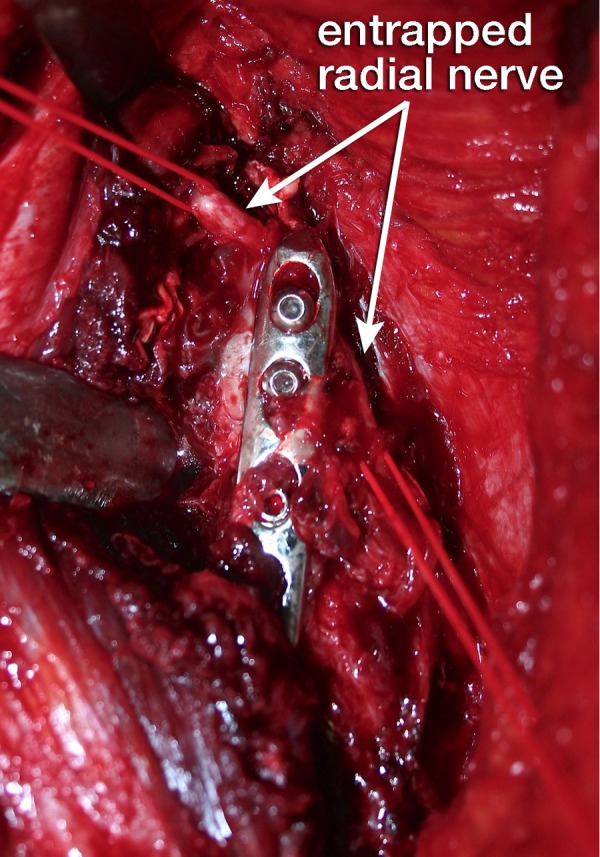

We decided to perform a radial nerve exploration and revision fixation using a double plating technique. We used a modified posterior approach of the humerus according to Gerwin et al.5 Intraoperatively, the radial nerve was found entrapped under the fixation plate. Locking screws were used but the plate was snugged down to the bone. After removing the plate, the nerve appeared to have been crushed by the plate and in addition the proximal screw had skewered and partially transected the nerve for at least 40% of its diameter (figure 4). Based on these devastating intraoperative findings, we believed the nerve to be irreversibly damaged. Even so, an external neurolysis was performed. The partially transected part was repaired with end-to-end neurorrhaphy using Ethilon 9.0 sutures under surgical microscope magnification (figure 5).

Figure 4.

Radial nerve (marked by red vessel loops) partially crushed between the locking plate and the humerus.

Figure 5.

Radial nerve after neurolysis and microscopic neurorrhaphy of the transected part.

At surgery, the fracture showed only minimal callus formation and no signs of infection. The humerus was reduced and stabilised with a 3.5 mm titanium pelvic reconstruction plate combined with 3.5 mm locking compression plate extra-articular distal humerus plate (both Synthes BV, Zeist, the Netherlands). There were no postoperative complications. The patient resumed hand therapy directly after the wound had healed.

Outcome and follow-up

Three weeks postoperatively, the first signs of radial nerve function recovery were already observed. At 10 months follow-up, the radial motor and sensory deficit had fully recovered. The fracture healed uncomplicated (figure 6). The patient regained strength, normal range of motion and returned to all her activities and work. Pain, measured by the Visual Analogue Scale (range 0–100) diminished from a score of 80 preoperatively to 0 at follow-up. Muscle strength of the radial nerve innervated muscles of the wrist, fingers and thumb improved from 0 to 4+ (Medical Research Scale). Grip strength (Jamar hand held dynamometer) improved from 8 kg (18.5% of the non-affected non-dominant hand) at 3 months postoperative to 30 kg (72%). The Disability of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand score (DASH) decreased from fully disabled preoperative (DASH score 100) to a score of 15.

Figure 6.

Radiograph months after revision fixation.

Discussion

The treatment of primary radial nerve palsy associated with humeral shaft fractures remains controversial. Given the high rate of spontaneous recovery of radial nerve palsies after closed humeral fractures and the risks of operative exploration like secondary infection and further nerve damage, the majority is managed without surgery.3 When secondary radial nerve palsy does occur, the treatment approach varies among surgeons. The chance of spontaneous recovery obviously depends on the condition of the nerve. Compression or traction injuries without neurotmesis are likely to recover spontaneously within 16–18 weeks, while the prognosis of (partially) transected nerves is poor.1 4 6 Identification and protection of the radial nerve during surgery may prevent nerve palsy, but is not always done. The surgical approach depends on the location of the fracture, the experience and preference of the surgeon.7 Only when the nerve is protected at completion of the primary surgical procedure does it seem that early exploration is not warranted in case of secondary palsy. If not, there will always be grounds for uncertainty as to whether the nerve is entrapped and/or lacerated by the internal fixation device or surgical instruments. Any indication for such possible nerve transection requires early exploration and neurorrhaphy or nerve reconstruction.6

It is well established that long-term nerve injury (neurotmesis) causes a reduction in the regeneration capacity of the affected neuron by a reduction in the number of axons.8 9 Furthermore, Schwann cell ability to respond to signals of axonal degeneration following peripheral nerve injury is significantly reduced after 2 months.10 These neurobiological aspects indicate that (partial) nerve transection should be determined early and repaired at least within 3 months, before irreversible loss occurs.

An additional diagnostic tool prior to exploration may be ultrasound. We did not use ultrasound in this case because surgical revision was indicated anyhow due to plate failure combined with radial nerve exploration. With an experienced radiologist and high-quality devices, ultrasound can identify discontinuity of the radial nerve with reasonable accuracy. Ultrasound allows for the distinction of neurotmesis from axonotmesis where neurophysiological evaluation could not, and may provide information useful for surgical planning.11 As such, it might be a useful adjunct in the treatment algorithm for secondary radial nerve palsies.

In our patient, we used the modified posterior approach for exposure of the humerus. Although technically more challenging, the modified posterior approach allows for increased visualisation of the posterior aspect of the humerus with identification and protection of the radial nerve.5 Because almost the entire posterior aspect of the humerus can be exposed, this approach allows for greater flexibility when internal fixation is needed for the humerus.

After neurolysis of the radial nerve from the zone of injury, we decided to perform a secondary neurorrhaphy of only the transected part of the nerve instead of a complete resection of the transected and crushed part of the nerve to make a complete neurorrhaphy of undamaged nerve endings. Because a part of the radial nerve was still intact in this case, the elastic properties of the nerve did not cause retraction. This is most likely an important feature in this case as tension-free repair without grafting is very beneficial for nerve recovery.

Learning points.

We feel that this case contributes to the surgical recommendation to identify and protect the radial nerve during posterior or straight lateral fixation of humeral shaft fractures. This case illustrates that early exploration of the radial nerve should at least be considered when there was failure to identify and protect the radial nerve at the primary surgery.

Although technically more challenging, the modified posterior approach allows for increased visualisation of the posterior aspect of the humerus with identification and protection of the radial nerve.

Compression or traction injuries of the radial nerve without neurotmesis after non-operative treatment of humerus fractures are likely to recover spontaneously within 16–18 weeks.

Footnotes

Contributors: Conception and design (PK, MK), analysis and interpretation of data (AK, PK, AV, MK). Drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content (AK, PK, AV, MK) and final approval of the version to be published (AK, PK, AV, MK).

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Shao YC, Harwood P, Grotz MR, et al. Radial nerve palsy associated with fractures of the shaft of the humerus: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2005;87:1647–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeFranco MJ, Lawton JN. Radial nerve injuries associated with humeral fractures. J Hand Surg Am 2006;31:655–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Korompilias AV, Lykissas MG, Kostas-Agnantis IP, et al. Approach to radial nerve palsy caused by humerus shaft fracture: is primary exploration necessary? Injury. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2013.01.004. Jan 22. pii: S0020-1383(13)00016-8. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2013.01.004. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang JP, Shen WJ, Chen WM, et al. Iatrogenic radial nerve palsy after operative management of humeral shaft fractures. J Trauma 2009;66:800–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gerwin M, Hotchkiss RN, Weiland AJ. Alternative operative exposures of the posterior aspect of the humeral diaphysis with reference to the radial nerve. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1996;78:1690–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pan CH, Chuang DC, Rodriguez-Lorenzo A. Outcomes of nerve reconstruction for radial nerve injuries based on the level of injury in 244 operative cases. J Hand Surg Eur Vol 2010;35:385–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walker M, Palumbo B, Badman B, et al. Humeral shaft fractures: a review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2011;20:833–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fu SY, Gordon T. Contributing factors to poor functional recovery after delayed nerve repair: prolonged denervation. J Neurosci 1995;15(5 Pt 2):3886–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fu SY, Gordon T. Contributing factors to poor functional recovery after delayed nerve repair: prolonged axotomy. J Neurosci 1995;15(5 Pt 2):3876–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li H, Wigley C, Hall SM. Chronically denervated rat Schwann cells respond to GGF in vitro. Glia 1998;24:290–303 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Padua L, Di Pasquale A, Liotta G, et al. Ultrasound as a useful tool in the diagnosis and management of traumatic nerve lesions. Clin Neurophysiol 2013;124:1237–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]