Abstract

Calcification of basal ganglia or Fahr's syndrome is a rare disease characterized by bilateral and symmetrical intracranial deposition of calcium mainly in cerebral basal ganglia. Motor and neuropsychiatric symptoms are prominent features. We report a case presented with a few motor symptoms, features of delirium and prominent psychiatric symptoms (disorganized behavior) predominantly evident after the improvement in delirium. Radiological findings were suggestive of bilateral basal ganglia calcification. Parathyroid hormone levels were low with no significant findings in other investigations and negative family history. Patient showed significant improvement in behavioral disturbances with risperidone, low dose of lorazepam, oxcarbazepine, and memantine.

Keywords: Basal ganglia, calcification, Fahr's syndrome, parathyroid hormone, psychiatric symptoms

INTRODUCTION

Fahr's syndrome is a rare[1] neurological disorder characterized by abnormal deposits of calcium in areas of the brain that control movement. Through the radio-imaging (computed tomography [CT] scans), calcifications are seen primarily in the basal ganglia and in other areas such as the cerebral cortex.[2] One definition proposed by Trautner et al. requires bilateral calcifications with neuropsychiatric and extra-pyramidal disorders with normal calcium and phosphorus metabolism.[3] Beall et al., 1989 gave another definition which describes seizures, rigidity, and dementia with characteristic calcification of the basal ganglia.[4] The most commonly affected region of the brain is the lenticular nucleus and in particular, the internal globus pallidus.[5] In adult-onset Fahr's disease, calcium deposition generally begins in the 3rd decade of life, with neurological deterioration 2 decades later.[6] Reduced blood flow to calcified regions correlates with clinical signs.[7] Symptoms develop when the deposits accumulate, including progressive deterioration of mental function, loss of previous motor development, spastic paralysis, and athetosis. In addition, optic atrophy may occur.

The disease usually manifests itself in the 3rd to 5th decade of life, but may appear in childhood or later in life.[8] Neuropsychiatric symptoms can be the first or the most prominent manifestations ranging from mild difficulty in concentration, memory changes in personality, behavior, frank psychosis and dementia.[9]

About 40% of patients with basal ganglia calcification (BGC) may present initially with psychiatric features.[10] Cognitive, psychotic, and mood disorders are common. Symptoms may change over time. More extensive calcification and subarachnoid space dilatation are known to correlate with the presence of psychiatric manifestations.[10]

Currently, there is no cure for Fahr's syndrome, nor a standard course of treatment. The available treatment is directed toward symptomatic control and treatment for cause of calcification. The prognosis is variable and difficult to predict. There is no reliable correlation between age, extent of calcium deposits in the brain, and neurological deficit. Progressive neurological deterioration generally results in disability and death.

CASE REPORT

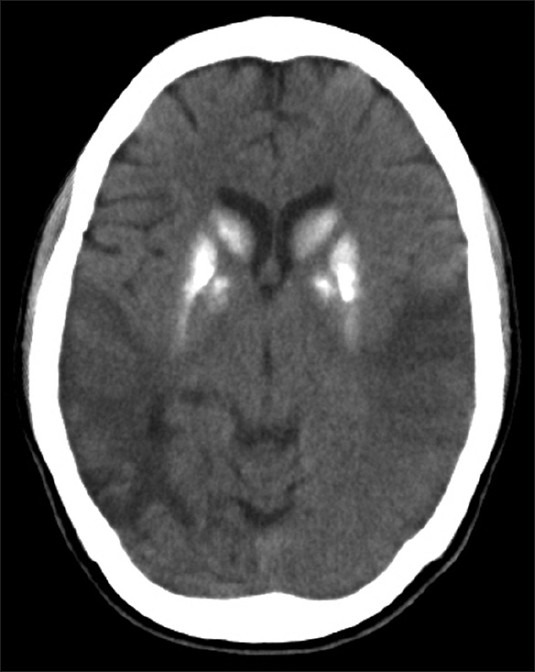

A 25-year-old married woman was brought by the mother to psychiatry outpatient department with the complaints of withdrawn behavior, headache, abnormal posturing, and reduced sleep since around 15 days and sudden onset altered behavior a night before during sleep, when patient woke up, started screaming, went to wash room and started inducing the vomiting. She was fearful and not recognizing the family members and couldn't sleep. The episode lasted for the whole night and the next day she was brought to the hospital. Family members denied any stressor or organic antecedents before the start of illness. There was no sociooccupational impairment according to family members though the patient was symptomatic in last 15 days. Patient did not report any depressive features, delusions, or hallucinations. Mother also reported doubtful history of abnormal jerky movements of lower limbs in sleep with altered sensorium, only one episode that lasted for 4-5 min few months back. On examination in the outpatient department, patient was found emaciated, not interacting, not maintaining eye contact, maintaining abnormal posture, was starring and bit drowsy. She was minimally responding even to the painful stimuli. Patient was urgently referred to Medicine Department, CT scan brain was done and the patient was admitted to medicine intensive care unit (MICU). The radiological findings showed bilateral symmetrical dense/amorphous BGC with white and grey matter edema in the left parietal and occipital region [Figure 1]. Based on the clinical features and radiological signs, differential diagnoses were considered as acute confusional state and cerebral edema with the possibility of tubercular meningitis, cerebral malaria and viral meningitis. Patient was investigated further for above conditions and meanwhile neurologist was consulted who advised magnetic resonant imaging (MRI) and electro-encephalogram. Patient was started on antibiotics and phenytoin. Patient remained in MICU for around 10 days and was persistently confused, agitated, talking irrelevantly, disoriented, sometimes not communicating at all and maintaining abnormal posture. For behavioral control, she was started on oral risperidone 0.5 mg and lorazepam 1 mg. Her cerebrospinal fluid examination revealed normal study, patient was negative for malarial parasite, and serum electrolytes were within normal range with normal liver and kidney function tests. Serum calcium and magnesium levels were within normal limits. MRI findings were suggestive of inherited/acquired leukoencephalopathy with BGC and associated mass effects on the left side of brain with grey matter hypointensity. She was negative for HIV and hepatitis B virus testing. Her hormonal study revealed normal thyroid status with low level of serum parathyroid hormone. Slowly there was an improvement in the features of delirium and when she became medically stable, was transferred to a psychiatry ward. In psychiatry ward patient was found continuously pacing around, minimally interacting, had poor self-care and disorganized behavior (e.g. handling the feces), irritable and anxious. But she was oriented in time, place and person. She was inconsistent in her verbal responses with rapid and unclear speech (dysarthric speech) and sometimes words could not be understood. Her judgment, immediate and recent memory was impaired and was not co-operative for remote memory testing. Doses of risperidone were increased. In view of low parathyroid level, her ionic calcium levels were done which came out to be within normal range (1.16 mmol/l). Endocrinologist's opinion was taken and started on treatment for hypoparathyroidism. Her past history revealed one episodes of vomiting with abnormal jerky movements of limbs around 4 years back. The details of treatment were not available. Her family history was not significant. She was educated up to HSC, was average in studies, married for around 8 years and had a history of spontaneous abortion around 2 years back. Her menstrual cycles were regular. Based on above history and investigations, diagnosis of Fahr's syndrome (bilateral BGC, dysarthria and neuropsychiatric symptoms) probably due to hypoparathyroidism was kept. Patient showed partial improvement in behavioral symptoms; hence, oxcarbazepine was added in a dose of 300 mg. Patient responded (with risperidone, oxcarbazapine, lorazepam, and memantine and treatment for hypo-parathyroidism) in next 20 days and was discharged.

Figure 1.

Computed tomography section of the patient showing calcification in Basal ganglia region

DISCUSSION

Fahr's syndrome is mostly associated with a disorder of calcium and phosphate metabolism, especially due to hypoparathyroidism (HPT),[11,12,13,14] but can also be due to other different etiologies, including infectious, metabolic, and genetic diseases.[15] Our patient did not have any abnormality in calcium and phosphate levels, but parathyroid level was low which may be the reason for BGC in our patient. Furthermore, there was no family history of the disease. The prevalence of Fahr's syndrome is unknown, but an incidence of BGCs ranging from 0.3% to 1.2% has been reported in routine radiological examinations.[16,17]

This patient did not have extrapyramidal symptoms or a metabolic disorder and had normal neurological examination except for speech abnormality (dysarthria). Similar cases have been reported in the literature.[18] The clinical expression of Fahr's disease can vary greatly. Symptoms can include features of psychiatric disorders, epileptic seizures and dementia.[19] However, other presentations have also been noted, like Simone et al. have reported a case of Fahr's disease with syncope and pseudo-HPT.[20] Our patient showed features of delirium and psychotic features in the form of muttering to self, disorganized behavior, pacing around, and irritability. Memory impairment was also observed in this patient and mini mental status examination score was 18/30.

About 40% of patients are known to present initially with psychiatric features and cognitive, psychotic, and mood disorders are common.[10] Paranoid and psychotic features often present between the ages of 20 and 40 in FD.[21] Two patterns of psychotic presentation in Fahr's disease are known, including early onset (mean age 30.7 years) with minimal movement disorder and late onset (mean age 49.4 years) associated with dementia and movement disorders.[22] This patient was presented at 25 years with psychosis and no extra pyramidal involvement. With such clinical findings, the presentation of a patient in early 20s with recent onset of first episode of acute onset psychotic features can lead to a misdiagnosis of acute transient psychotic disorder (ATPD), especially in Asian countries like India where ATPD is very common.[1] The treatment of Fahr's syndrome is directed to the identifiable cause[23] along with a symptomatic treatment. Especially in HPT, the early treatment can prevent calcification and neurophysiological disorders.[11,12,24] Our patient showed response with Risperidone 1 mg, Lorazepam 2 mg and Oxcarbazapine 300 mg in around 20 days. Studies show that psychosis in setting of Fahr's disease is known to respond variably to treatment and is sometimes unresponsive.[22]

CONCLUSIONS

Psychiatrists should consider Fahr's syndrome as a differential diagnosis in the evaluation of psychosis associated with atypical presentation and motor abnormalities. This case further emphasizes the importance of the role of neuroimaging and the search for disrupted phosphocalcic metabolism and abnormal parathyroid levels in patients with atypical psychotic symptoms. Judicial use of risperidone and oxcarbazapine can definitely help in controlling the behavioral symptoms in Fahr's syndrome.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge our patient who consented for the case report publication and head of the Department of Radiology who helped us in understanding the radiological findings of the patient.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Srivastava S, Bhatia MS, Sharma V, Mahajan S, Rajender G. Fahr's disease: An incidental finding in a case presenting with psychosis. Ger J Psychiatry. 2010;13:86–90. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benke T, Karner E, Seppi K, Delazer M, Marksteiner J, Donnemiller E. Subacute dementia and imaging correlates in a case of Fahr's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:1163–5. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.019547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trautner RJ, Cummings JL, Read SL, Benson DF. Idiopathic basal ganglia calcification and organic mood disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1988;145:350–3. doi: 10.1176/ajp.145.3.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beall SS, Patten BM, Mallette L, Jankovic J. Abnormal systemic metabolism of iron, porphyrin, and calcium in Fahr's syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1989;26:569–75. doi: 10.1002/ana.410260412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonazza S, La Morgia C, Martinelli P, Capellari S. Strio-pallido-dentate calcinosis: A diagnostic approach in adult patients. Neurol Sci. 2011;32:537–45. doi: 10.1007/s10072-011-0514-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manyam BV, Bhatt MH, Moore WD, Devleschoward AB, Anderson DR, Calne DB. Bilateral striopallidodentate calcinosis: Cerebrospinal fluid, imaging, and electrophysiological studies. Ann Neurol. 1992;31:379–84. doi: 10.1002/ana.410310406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uygur GA, Liu Y, Hellman RS, Tikofsky RS, Collier BD. Evaluation of regional cerebral blood flow in massive intracerebral calcifications. J Nucl Med. 1995;36:610–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sobrido MJ, Hopfer S, Geschwind DH. Familial idiopathic basal ganglia calcification. In: Pagon RA, Bird TD, Dolan CR, Stephens K, editors. SourceGeneReviews. Seattle (WA): University of Washington; 2007. pp. 1993–2004. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiu HF, Lam LC, Shum PP, Li KW. Idiopathic calcification of the basal ganglia. Postgrad Med J. 1993;69:68–70. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.69.807.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.König P. Psychopathological alterations in cases of symmetrical basal ganglia sclerosis. Biol Psychiatry. 1989;25:459–68. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(89)90199-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nicolau Ramis J, Espino Ibáñez A, Rivera Irigoín R, Artigas CF, Masmiquel Comas L. Extrapyramidal symptoms due to calcinosis cerebri in a patient with unknown primary hypoparathyroidism. Endocrinol Nutr. 2012;59:69–71. doi: 10.1016/j.endonu.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goswami R, Sharma R, Sreenivas V, Gupta N, Ganapathy A, Das S. Prevalence and progression of basal ganglia calcification and its pathogenic mechanism in patients with idiopathic hypoparathyroidism. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2012;77:200–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2012.04353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baba Y, Broderick DF, Uitti RJ, Hutton ML, Wszolek ZK. Heredofamilial brain calcinosis syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80:641–51. doi: 10.4065/80.5.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Senoglu M, Tuncel D, Orhan FO, Yuksel Z, Gokçe M. Fahr's syndrome: A report of two cases. Firat Tip Dergisi. 2007;12:70–2. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swami A, Kar G. Intracranial hemorrhage revealing pseudohypoparathyroidism as a cause of Fahr syndrome. Case Rep Neurol Med 2011. 2011 doi: 10.1155/2011/407567. 407567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kazis AD. Contribution of CT scan to the diagnosis of Fahr's syndrome. Acta Neurol Scand. 1985;71:206–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1985.tb03190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fénelon G, Gray F, Paillard F, Thibierge M, Mahieux F, Guillani A. A prospective study of patients with CT detected pallidal calcifications. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1993;56:622–5. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.56.6.622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kotan D, Aygul R. Familial Fahr disease in a Turkish family. South Med J. 2009;102:85–6. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181833f02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Modrego PJ, Mojonero J, Serrano M, Fayed N. Fahr's syndrome presenting with pure and progressive presenile dementia. Neurol Sci. 2005;26:367–9. doi: 10.1007/s10072-005-0493-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simone O, Tortorella C, Antonaci G, Antonaci S. An unusual case of transient loss of consciousness: The Fahr's syndrome. Recenti Prog Med. 2008;99:93–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cummings JL. Orlando, FL: Grune and Stratton; 1985. Clinical Neuropsychiatry; pp. 154–5. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cummings JL, Gosenfeld LF, Houlihan JP, McCaffrey T. Neuropsychiatric disturbances associated with idiopathic calcification of the basal ganglia. Biol Psychiatry. 1983;18:591–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mitchell DM, Regan S, Cooley MR, Lauter KB, Vrla MC, Becker CB, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with hypoparathyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:4507–14. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rastogi R, Singh AK, Rastogi UC, Mohan C, Rastogi V. Fahr's syndrome: A rare clinico-radiologic entity. Med J Armed Forces India. 2011;67:159–61. doi: 10.1016/S0377-1237(11)60020-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]