Abstract

Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) is a common disorder. Although the etiology of PMS is not clear, to relieve from this syndrome different methods are recommended. One of them is use of medicinal herbs. This study was carried out to evaluate effects of ginger on severity of symptoms of PMS. This study was a clinical trial, double-blinded work, and participants were randomly allocated to intervention (n = 35) and control (n = 35) groups. To determine persons suffering from PMS, participants completed daily record scale questionnaire for two consecutive cycles. After identification, each participant received two ginger capsules daily from seven days before menstruation to three days after menstruation for three cycles and they recorded severity of the symptoms by daily record scale questionnaire. Data before intervention were compared with date 1, 2, and 3 months after intervention. Before intervention, there were no significant differences between the mean scores of PMS symptoms in the two groups, but after 1, 2, and 3 months of treatment, there was a significant difference between the two groups (P < 0.0001). Based on the results of this study, maybe ginger is effective in the reduction of severity of mood and physical and behavioral symptoms of PMS and we suggest ginger as treatment for PMS.

1. Introduction

Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) is one of the most common problems in women at their reproductive age [1, 2]. PMS is defined as the recurrent mood and physical symptoms which is usually in the luteal phase, and it remits in the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle [3–6]. There is a high prevalence of PMS; about 80% of women reported mild premenstrual symptoms, 20%–50% reported moderate symptoms, and about 5% of women had severe symptoms [7, 8]. Despite the high incidence of premenstrual syndrome, causes of it have not been clear and several etiologies have been suggested (e.g., hormonal change, neurotransmitters, prostaglandins, diet, drugs, and lifestyle) [7, 9–14]. Although the exact etiology of PMS is not known, a wide range of therapeutic interventions have been tested to treat premenstrual symptoms (e.g., lifestyle changes, pharmacological intervention, and nonpharmacological treatments) [15–22]. Due to the side effects of chemical drugs, except severe cases, chemical drugs consumption is not recommended. Today, complementary and herbal medicine are commonly used in the treatment of many chronic conditions such as PMS, menopausal symptoms, and dysmenorrhea [17, 20, 23–27].

Ginger is commonly used in the herbal medicine and traditionally it used to treat dysmenorrhea [28, 29]. Zingiber officinale is the scientific name of plant Ginger [30]. Ginger rhizome is used in traditional medicine [31]. Studies showed beneficial effects of ginger on vomiting, nausea, motion sickness, arthritis, migraine, headache, and so forth [32]. In addition, studies have shown that the ginger can modulate prostaglandins system [33–35]. With regard to the role of prostaglandins in PMS and effect of ginger on modulation of prostaglandins system, the aim of this study was evaluating the effects of ginger on the severity of the PMS symptoms.

2. Materials and Methods

This clinical trial was a randomized, double-blinded, and placebo-controlled study. The study was done on 70 female students in dormitories of Tehran University of Medical Sciences in the year of 2013. Data were collected during 7 months. The ethics committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences approved the study (No. 97/130/D/92) and it was registered at Iranian Registry of Clinical Trial (IRCT No. 201301012751N7).

Inclusion criteria were as follows: being healthy premenopausal women aged between 18 and 35 years, having regular menstrual cycles of 21–35 days, being single, lacking sensitivity to ginger, not taking any medication, not drinking alcohol, not smoking, and not having stressful events in the last 3 months.

The participants recorded symptoms with daily record questionnaires (this form contains a table with 19 symptoms of premenstrual syndrome questionnaire based on the DSM-IV (the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders of the American Psychiatric Association), Self-Rating Scale) for two cycles before the intervention. This questionnaire determines the severity of PMS using 3 items, including mood symptoms (restlessness; irritability; anxiety, depression, or sadness; crying; feeling of isolation), physical symptoms (headache, breast tenderness, backache, abdominal pain, weight gain, swelling of extremities, muscle stiffness, gastrointestinal symptoms, and nausea), and behavioral characteristics (fatigue, lack of energy, insomnia, difficulty in concentrating, increased or decreased appetite). Then the severity of premenstrual syndrome was evaluated for all participants ((0) absence of symptoms, (1) mild symptoms that may not interfere with everyday activities, (2) moderate symptoms that interfere with daily activities, and (3) severe symptoms that impede doing daily activities). Each participant with at least five symptoms was finally diagnosed as a person with PMS. After identifying patients with PMS, they were randomly divided into two groups (n = 35). The first group received ginger capsule and the second group received placebo capsule. Doses of ginger and placebo were 250 mg/12 hours and given from 7 days before and until 3 days after onset of menstrual bleeding. The subjects completed the daily record questionnaire at their first, second, and third menstrual cycles. After interventions, again the severity of PMS was evaluated. Participants and researcher were blind about the kind of drug throughout the study. Exclusion criteria were incidence of side effects drugs or drugs allergy, use of other drugs, drug use disorder, identifying any diseases during the study, getting married during the study, menstrual irregularities, and irregular bleeding event during the study.

Statistical analysis was performed using software SPSS-18. Intergroup analyses were performed to compare the total score of PMS, mood, and behavioral and physical symptoms before and after the intervention. Intergroup analysis was performed by independent samples t-test. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

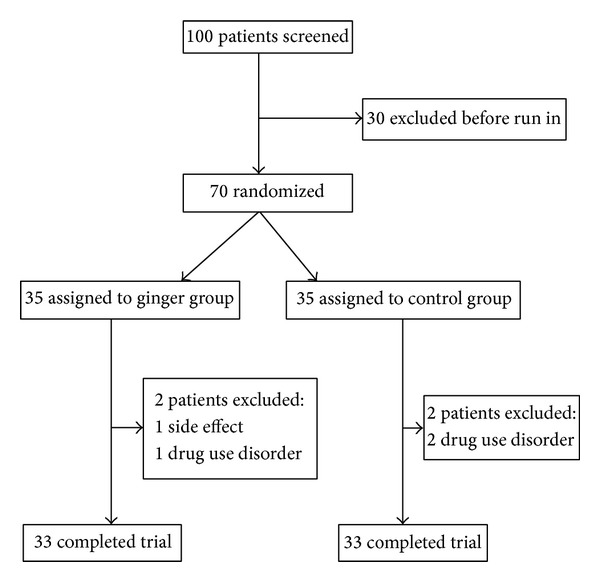

Out of the 70 students who participated in the study 2 persons in the ginger group and 2 persons in the placebo group did not complete the study (Figure 1). In the ginger group two samples were excluded, one because of incidence of side effect and second one due to misuse of ginger. In the placebo group reason for exclusion for each of the 2 people was drug use disorder.

Figure 1.

Trial profile.

No significant differences between two groups were seen with regard to demographic characteristics and menstrual history data (Table 1).

Table 1.

The demographic characteristics and menstrual history of the participants.

| Characteristics | Group | Test results |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Ginger | ||

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | ||

| Age (year) | 25.52 ± 3.13 | 24.76 ± 3.17 | P = 0.33 |

| Weight (kg) | 59.61 ± 9.69 | 57.55 ± 7.4 | P = 0.24 |

| Height (cm) | 160.9 ± 6.66 | 161.4 ± 5.72 | P = 0.92 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.33 ± 3.44 | 22.13 ± 2.95 | P = 0.1 |

| Age at menarche (year) | 13.48 ± 1.25 | 13.21 ± 1.31 | P = 0.39 |

| Duration of cycle (day) | 29 ± 1.42 | 28.7 ± 1.6 | P = 0.46 |

| Duration of menstruation (day) | 5.3 ± 1.46 | 5.8 ± 1.36 | P = 0.1 |

There were no significant differences regarding the total score of PMS, severity of mood, and physical and behavioral symptoms between the two groups before the intervention (resp., P = 0.71, P = 0.69, P = 0.56, and P = 0.76) (Table 2). Statistical analysis demonstrated that there were significant differences in total score of PMS, severity of mood, and physical and behavioral symptoms between the two groups after the intervention, and ginger could reduce severity symptom of PMS (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of PMS scores in ginger and placebo groups before and after the intervention.

| Symptoms | Group | Test results | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Ginger | ||

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Unpaired test | |

| Total severity of PMS | |||

| Before intervention | 106.7 ± 44.65 | 110.2 ± 30.77 | P = 0.71 |

| One month after intervention | 105.7 ± 45.76 | 51.18 ± 32.76 | P < 0.0001 |

| Two months after intervention | 107.2 ± 50.68 | 49.48 ± 33.12 | P < 0.0001 |

| Three months after intervention | 106 ± 48.74 | 47.06 ± 33.41 | P < 0.0001 |

| Mood symptoms | |||

| Before intervention | 37.42 ± 17.37 | 38.97 ± 14.16 | P = 0.69 |

| One month after intervention | 37.18 ± 16.13 | 16.39 ± 10.54 | P < 0.0001 |

| Two months after intervention | 37.61 ± 18.58 | 14.61 ± 8.84 | P < 0.0001 |

| Three months after intervention | 38.37 ± 20.31 | 13.45 ± 10.65 | P < 0.0001 |

| Physical symptoms | |||

| Before intervention | 42.64 ± 23.83 | 45.76 ± 19.76 | P = 0.56 |

| One month after intervention | 43.48 ± 24.25 | 21.85 ± 22.54 | P = 0.0004 |

| Two months after intervention | 43.42 ± 24.13 | 21.12 ± 20.31 | P < 0.0001 |

| Three months after intervention | 42.06 ± 22.76 | 22.76 ± 19.62 | P = 0.0005 |

| Behavioral symptoms | |||

| Before intervention | 26.64 ± 16.20 | 25.42 ± 16.05 | P = 0.76 |

| One month after intervention | 25.06 ± 17.86 | 12.94 ± 12.35 | P = 0.002 |

| Two months after intervention | 26.15 ± 19.08 | 13.76 ± 13.79 | P = 0.003 |

| Three months after intervention | 25.61 ± 18.47 | 10.85 ± 13.05 | P = 0.0004 |

4. Discussion

The findings of this study showed that ginger could significantly reduce the total score of PMS, severity of mood, and physical and behavioral symptoms of the first month intervention. So according to the availability and the safety of ginger, the ginger can be an appropriate treatment in reducing symptoms of premenstrual syndrome. One of the proposed mechanisms that lead to premenstrual syndrome is change in prostaglandin system [7, 16, 36]. Ginger through the inhibition of the metabolism of cyclooxygenase and lipoxygenase prevents the production of prostaglandins [35]. To our knowledge, this study is the first report about the effect of ginger on premenstrual syndrome. Rahnama et al. [28] and Ozgoli et al. [29] showed that the use of ginger is effective in reducing symptoms of dysmenorrheal [28, 29]. Primary dysmenorrhea is caused by excessive production of prostaglandins from the endometrial tissue, and 80% of cases of dysmenorrhea with prostaglandin inhibitors can be improved [29]. Because some ginger compounds are prostaglandin inhibitors and are effective on dysmenorrhea, so perhaps through this mechanism they could be effective on other problems of menstruation cycle [28, 29]. Some of symptoms of PMS like pain are common with dysmenorrhea (such as backache and abdominal pain). In our study these symptoms of PMS have been reduced.

In women with PMS, severe headache outbreaks during the luteal phase and an increase in headache resistance to painkillers and anti-inflammatory drugs lead to increase in depression, irritability, anxiety, anger, and food intolerance during the luteal phase [37–39]. Cady et al. [40] reported that ginger administration caused a significant deceleration in severity of headache in patients with migraine [40]. One of the symptoms of PMS is incidence of headache and exacerbation of migraine. In our study ginger was found to be effective in relieving headaches.

Levine et al. reported that the ginger reduced the delayed nausea of chemotherapy and reduced use of antiemetic medications [41]. Ginger was effective in treating nausea and vomiting during pregnancy [31, 42]. Study of K. S. Naeine and S. S. Naeine [43] showed that the use of 1 gram of powdered ginger, 1 hour before taking contraceptive pills, induced reduction in contraceptive pills nausea [43]. Nausea is one of symptoms of PMS; in our study the incidence of gastrointestinal disturbances and nausea after taking ginger reduced.

Studies showed that ginger has anti-inflammatory properties and is effective in treatment of pain in patients with osteoarthritis, muscle pain [30, 33, 44]. Joint and muscle pain are also symptoms of PMS; in the present study, ginger was effective in relieving severity of these symptoms of PMS.

The only side effect observed in the present study was nausea in the group of ginger. In addition, the use of ginger in traditional medicine to treat colds, fever, sore throat, nausea, stomach upset, muscle aches, and arthritis and for cancer prevention is effective [32]. Therefore, the use of ginger in the treatment of PMS can also benefit from other advantages of ginger.

5. Conclusions

The findings of the present study demonstrated the likelihood of usefulness of ginger in treating PMS while no specific side effects have been seen, and consumption of it is associated with health benefits. Ginger is readily available because of its low cost and, so, can be widely used in the treatment of premenstrual syndrome. According to increased tendency in the use of traditional medicine and herbal medicine, especially for people who have no desire to use chemical drugs, with more side effects, use of ginger, with very low side effects, is very useful. Furthermore, we cannot find study that evaluates effect of ginger on PMS; we suggest doing more studies with larger number of patients concerning the efficacy and safety of different doses of ginger.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Tehran University of Medical Sciences. The authors thank the Department of Student and Research Assistance of Tehran University of Medical Sciences, and Golestan 8 and Vesal dormitories' administrators, and students residing in Golestan 8 and Vesal dormitories for their nice assistance in data collection. (This paper is relevant to the midwifery master degree thesis of Samira khayat.)

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Claman F, Miller T. Premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder in adolescence. Journal of Pediatric Health Care. 2006;20(5):329–333. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Lin H, Rickels K, Sondheimer SJ. Clinical subtypes of premenstrual syndrome and responses to sertraline treatment. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2011;118(6):1293–1300. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318236edf2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Indusekhar R, Usman SB, O’Brien S. Psychological aspects of premenstrual syndrome. Best Practice and Research: Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2007;21(2):207–220. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ford O, Lethaby A, Roberts H, Mol BW. Progesterone for premenstrual syndrome. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012;(3) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003415.pub4.CD003415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braverman PK. Premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. 2007;20(1):3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bakr I, Ez-Elarab HS. Prevalence of premenstrual syndrome and the effect of its severity on the quality of life among medical students. The Egyptian Journal of Community Medicine. 2010;28(2):19–30. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pearlstein T, Steiner M. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder: burden of illness and treatment update. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience. 2008;33(4):291–301. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brahmbhatt S, Sattigeri BM, Shah H, Kumar A, Parikh D. A prospective survey study on premenstrual syndrome in young and middle aged women with an emphasis on its management. International Journal of Research in Medical Sciences. 2013;1(2):69–72. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qiao M, Zhao Q, Wei S, Zhang H, Wang H. Premenstrual dysphoria and luteal stress in dominant-social-status female macaques. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2013;2013:9 pages. doi: 10.1155/2013/393862.393862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baker FC, Kahan TL, Trinder J, Colrain IM. Sleep quality and the sleep electroencephalogram in women with severe premenstrual syndrome. Sleep. 2007;30(10):1283–1291. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.10.1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ismail KMK, O’Brien S. Premenstrual syndrome. Current Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2005;15(1):25–30. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campagne DM, Campagne G. The premenstrual syndrome revisited. European Journal of Obstetrics Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 2007;130(1):4–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2006.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salamat S, Ismail KMK, O’ Brien S. Premenstrual syndrome. Obstetrics, Gynaecology and Reproductive Medicine. 2008;18(2):29–32. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sadler C, Smith H, Hammond J, et al. Lifestyle factors, hormonal contraception, and premenstrual symptoms: the United Kingdom Southampton Women’s survey. Journal of Women’s Health. 2010;19(3):391–396. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Milewicz A, Jedrzejuk D. Premenstrual syndrome: from etiology to treatment. Maturitas. 2006;55(1):S47–S54. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Halbreich U. The etiology, biology, and evolving pathology of premenstrual syndromes. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2003;28(3):55–99. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(03)00097-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yonkers KA, O’Brien PS, Eriksson E. Premenstrual syndrome. The Lancet. 2008;371(9619):1200–1210. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60527-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Berardis D, Serroni N, Salerno RM, Ferro FM. Treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) with a novel formulation of drospirenone and ethinyl estradiol. Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management. 2007;3(4):585–590. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lim C, Park Y, Bae Y. The effect of the kinesio taping and spiral taping on menstrual pain and premenstrual syndrome. Journal of Physical Therapy Science. 2013;25(7):761–764. doi: 10.1589/jpts.25.761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Whelan AM, Jurgens TM, Naylor H. Herbs, vitamins and minerals in the treatment of premenstrual syndrome: a systematic review. Canadian Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2009;16(3):e407–e429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Delaram M, Kheiri S, Hodjati MR. Comparing the effects of echinophora-platyloba, fennel and placebo on premenstrual syndrome. Journal of Reproduction and Infertility. 2011;12(3):221–226. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chung M-S, Kim G-H. Effects of Elsholtzia splendens and Cirsium japonicum on premenstrual syndrome. Nutrition Research and Practice. 2010;4(4):290–294. doi: 10.4162/nrp.2010.4.4.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Domoney CL, Vashisht A, Studd JWW. Premenstrual syndrome and the use of alternative therapies. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2003;997:330–340. doi: 10.1196/annals.1290.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsumoto T, Asakura H, Hayashi T. Does lavender aromatherapy alleviate premenstrual emotional symptoms? A randomized crossover trial. Biopsychosocial Medicine. 2013;7(12, article 12) doi: 10.1186/1751-0759-7-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Filho EAR, Lima JC, Neto JSP, Montarroyos U. Essential fatty acids for premenstrual syndrome and their effect on prolactin and total cholesterol levels: a randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled study. Reproductive Health. 2011;8, article 2 doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-8-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fugh-Berman A, Kronenberg F. Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in reproductive-age women: a review of randomized controlled trials. Reproductive Toxicology. 2003;17(2):137–152. doi: 10.1016/s0890-6238(02)00128-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.He Z, Chen R, Zhou Y, et al. Treatment for premenstrual syndrome with Vitex agnus castus: a prospective, randomized, multi-center placebo controlled study in China. Maturitas. 2009;63(1):99–103. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rahnama P, Montazeri A, Huseini HF, Kianbakht S, Naseri M. Effect of Zingiber officinale R. rhizomes (ginger) on pain relief in primary dysmenorrhea: a placebo randomized trial. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2012;12, article 92 doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-12-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ozgoli G, Goli M, Moattar F, Valaie N. Comparing ginger with mefenamic acid and ibubrofen for the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea. Pejouhesh. 2007;31(1):61–65. [Google Scholar]

- 30.White B. Ginger: an overview. American Family Physician. 2007;75(11):1689–1691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heitmann K, Nordeng H, Holst L. Safety of ginger use in pregnancy: results from a large population-based cohort study. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2013;69(2):269–277. doi: 10.1007/s00228-012-1331-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baliga MS, Haniadka R, Pereira MM, et al. Update on the chemopreventive effects of ginger and its phytochemicals. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 2011;51(6):499–523. doi: 10.1080/10408391003698669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chrubasik S, Pittler MH, Roufogalis BD. Zingiberis rhizoma: a comprehensive review on the ginger effect and efficacy profiles. Phytomedicine. 2005;12(9):684–701. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ali BH, Blunden G, Tanira MO, Nemmar A. Some phytochemical, pharmacological and toxicological properties of ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe): a review of recent research. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2008;46(2):409–420. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.09.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Butt MS, Sultan MT. Ginger and its health claims: molecular aspects. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 2011;51(5):383–393. doi: 10.1080/10408391003624848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dickerson LM, Mazyck PJ, Hunter MH. Premenstrual syndrome. American Family Physician. 2003;67(8):1743–1752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fragoso YD, Guidoni ACR, de Castro LBR. Characterization of headaches in the premenstrual tension syndrome. Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria. 2009;67(1):40–42. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2009000100010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martin VT, Wernke S, Mandell K, et al. Symptoms of premenstrual syndrome and their association with migraine headache. Headache. 2006;46(1):125–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Allais G, Gabellari IC, Burzio C, et al. Premenstrual syndrome and migraine. Neurological Sciences. 2012;33(supplement 1):111–115. doi: 10.1007/s10072-012-1054-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cady RK, Goldstein J, Nett R, Mitchell R, Beach ME, Browning R. A double-blind placebo-controlled pilot study of sublingual feverfew and ginger (LipiGesic M) in the treatment of migraine. Headache. 2011;51(7):1078–1086. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2011.01910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Levine ME, Gillis MG, Koch SY, Voss AC, Stern RM, Koch KL. Protein and ginger for the treatment of chemotherapy-induced delayed nausea. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2008;14(5):545–551. doi: 10.1089/acm.2007.0817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Modares M, Besharat S, Kian FR, Besharat S, Mahmoudi M, Sourmaghi HS. Effect of Ginger and Chamomile capsules on nausea and vomiting in pregnancy. Journal of Gorgan University of Medical Sciences. 2012;14(1):46–51. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Naeine KS, Naeine SS. The effect of ginger on nausea and vomiting of oral contraceptives users in Shiraz. Islamic Azad University of Medical Sciences Journal. 2009;1(19):31–34. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Naderi Z, Mozaffari-Khosravi H, Dehghan A, Hosseini HF, Nadjarzadeh A. The effect of ginger (zingiber officinale) powder supplement on pain in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a double-blind randomized clinical trial. Journal of Shaeed Sdoughi University of Medical Sciences. 2012;20(5):657–667. [Google Scholar]