Abstract

Cholecystokinin (CCK) plays a role in the short-term inhibition of food intake. Cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript (CART) peptide has been observed in neurons of the paraventricular nucleus (PVN). It has been reported that intracerebroventricular injection of CART peptide inhibits food intake in rodents. The aim of the study was to determine whether intraperitoneally (ip) injected CCK-8S affects neuronal activity of PVN-CART neurons. Ad libitum fed male Sprague-Dawley rats received 6 or 10 μg/kg CCK-8S or 0.15 M NaCl ip (n = 4/group). The number of c-Fos-immunoreactive neurons was determined in the PVN, arcuate nucleus (ARC), and the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS). CCK-8S dose-dependently increased the number of c-Fos-immunoreactive neurons in the PVN (mean ± SEM: 102 ± 6 vs. 150 ± 5 neurons/section, p < 0.05) and compared to vehicle treated rats (18 ± 7, p < 0.05 vs. 6 and 10 μg/kg CCK-8S). CCK-8S at both doses induced an increase in the number of c-Fos-immunoreactive neurons in the NTS (65 ± 13, p < 0.05, and 182 ± 16, p < 0.05). No effect on the number of c-Fos neurons was observed in the ARC. Immunostaining for CART and c-Fos revealed a dose-dependent increase of activated CART neurons (19 ± 3 vs. 29 ± 7; p < 0.05), only few activated CART neuron were observed in the vehicle group (1 ± 0). The present observation shows that CCK-8S injected ip induces an increase in neuronal activity in PVN-CART neurons and suggests that CART neurons in the PVN may play a role in the mediation of peripheral CCK-8S's anorexigenic effects.

Keywords: CCK, CART, c-Fos, Food intake, PVN

1. Introduction

Peptide hormones play a pivotal role in the regulation of food intake [43]. Studies in the early 1970s showed that injection of peripheral cholecystokinin (CCK) before food exposure causes a dose-dependent decrease in meal size [10,11]. Numerous differing fragments of CCK can be identified in animals. All of them originate from one single gene and they are formed by different means of posttranslational or extracellular modification. The most common forms are CCK-8, CCK-33, and CCK-58 [9,20,28–30]. However, sulfated CCK-8, CCK-8S is most commonly used in behavioral and pharmacological studies on food intake [3,15,44]. CCK is synthesized by a population of endocrine cells in the upper small intestine, I-cells, [4] and affects food intake by binding to its CCKA receptor located on the vagus nerve, as demonstrated by studies showing a reduction of the peptide's inhibitory influence on feeding by surgical or chemical deafferentation of the vagus nerve [8,33,37]. Many reports indicate that CCK's modulation of food intake is mediated at least partly by distinct brain nuclei, as demonstrated by changes in neuronal activity after peripheral injection of CCK [6,8,15,23,26]. Furthermore, studies revealed that CCK activates corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF)-, oxytocin- and as recently shown nesfatin-1-immunopositve neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN) [23,26,39]. These neuropeptides block food intake when injected intracerebroventricularly (icv) into the second or third brain ventricle in rodents [18,24,25]. However, peripheral CCK also affects the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA)-axis [5,13].

Cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript (CART) is synthesized – beside other brain areas – in hypothalamic neurons, especially in the PVN and in the arcuate nucleus (ARC) of the hypothalamus [7]. Studies show that icv administrations of CART peptides have an inhibitory effect on food intake in rodents [1,19,38,41]. Additionally, icv injection of CART increased neuronal activity in PVN and ARC neurons of the hypothalamus [41]. Similarly to CCK, icv injection of CART activates the synthesis of c-Fos in oxytocin and CRF neurons of the PVN [40]. However, a recent study demonstrated that in fasted mice, the effect of CART on food intake acts synergistically with peripherally injected CCK-8S, and furthermore, the inhibitory action of CART on food intake can be reduced by systemic co-administration of the CCKA receptor antagonist, devazepide [21]. These data point towards a possible role for CCK-8S to modify the effect of CART peptide on food intake [21].

However, to date it has not been investigated whether peripherally injected CCK-8S modulates neuronal activity of CART neurons localized in the PVN. Therefore, the goal of this study was to examine whether CCK-8S injected intraperitoneally (ip) at different doses influences neuronal activity of CART-immunoreactive neurons in the PVN.

2. Methods

2.1. Animals

Male Sprague–Dawley rats (Harlan-Winkelmann Co., Borchen, Germany) weighing 250–300 g were housed (four rats/group) under conditions of controlled illumination (12:12 h light/dark cycle), humidity, and temperature (22 ± 2 °C) for at least 21 days prior to experiments. Animals were fed ad libitum with a standard rat diet (Altromin®, Lage, Germany) and tap water. All animals were accustomed to the experimental conditions for a period of 14 days by handling them daily and putting them in the position to mimic the procedure of intraperitoneal (ip) injection. The handling was carried out between 9:00 and 11:00 h during the light phase. Animal care and experimental procedures followed institutional ethic guidelines and conformed to the requirements of the state authority for animal research conduct.

2.2. Peptide

CCK-8S (Bachem AG, Heidelberg, Germany) was dissolved in water with 1% (v/v) 1 N NH4OH and stored at −20 °C. Immediately before starting the experiments, the peptide was diluted in vehicle solution consisting of sterile 0.15 M NaCl (Braun, Melsungen, Germany) to reach the final concentration of 6 and 10 μg/kg body weight (5.2 and 8.7 nmol/kg). Peptide solutions were kept on ice for the duration of the experiments.

2.3. Experimental design

Ad libitum fed rats received an ip injection (final volume: 0.5 ml) of 6 and 10 μg/kg CCK-8S (n = 4/group) or vehicle solution (0.15 M NaCl, n = 4). 90 min after ip injection, animals were deeply anesthetized with 100 mg/kg ketamine (Ketanest®, Curamed, Karlsruhe, Germany) and 10 mg/kg xylazine (Rompun® 2%, Bayer, Leverkusen, Germany) and heparinized with 2500 IU heparin ip (Liquemin®, Hoffmann-La Roche, Grenzach-Whylen, Germany). Transcardial perfusion was performed as described before [14].

2.4. Immunohistochemistry

2.4.1. Single labeling immunohistochemistry for c-Fos in the PVN, ARC, and NTS

25 μm free-floating brain sections were pre-treated with 1% (w/v) sodium borohydride in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for 15 min. Subsequently, sections were incubated in a solution containing 1% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 0.3% (v/v) Triton X-100 in PBS for 60 min for blockade of unspecific antibody binding. The diluted primary antibody solution (rabbit anti-rat c-Fos, Oncogene Research Products, Boston, USA; 1:3000 in a solution of 1% (w/v) BSA, and 0.1% (w/v) sodium azide in PBS) was applied for 24 h at room temperature. After rinsing sections in PBS three times and incubation in a solution containing 1% (w/v) BSA in PBS for 60 min, FITC-labeled goat-anti-rabbit IgG (Sigma, St. Louis, USA) was applied for 12 h at room temperature in an appropriate dilution (1:400 in 1% (w/v) BSA in PBS). Then, brain sections were rinsed in PBS three times and stained with propidium iodide (2.5 μg/ml in PBS) for 15 min to counter stain cell chromatin. Sections were finally embedded in 8 μl anti-fading solution (100 mg/ml 1,4-diazabicyclo [2.2.2] octane (Sigma, St. Louis, USA) in 90% (v/v) glycerine, 10% (v/v) PBS, pH 7.4), and analyzed using a confocal laser scanning microscope (cLSM 510 Meta, Carl Zeiss, Germany).

2.4.2. Double labeling immunohistochemistry for c-Fos and CART in the PVN of the hypothalamus

Brain sections (25 μm) were incubated with a 1% (w/v) sodium borohydride solution for 15 min. After rinsing in PBS three times again, sections were incubated in PBS blocking buffer (0.1 M PBS, 1% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA), 0.3% (v/v) Triton X-100, and 0.05% (v/v) phenylhydrazine, pH 7.5) for 1 h. Afterwards, the diluted primary antibody solution (rabbit anti-c-Fos; Oncogene Research Products; 1:3000 in PBS blocking buffer without Triton X-100 and phenylhydrazine) was applied for 24 h at room temperature. After rinsing in PBS three times, sections were incubated with the secondary antibody solution (goat biotin-SP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, PA, USA; 1:1000 in 1% (w/v) BSA in PBS) for 12 h at room temperature. After rinsing in PBS solution three times (free of sodium acid), sections were incubated in avidin–biotin peroxidase complex (ABC; 1:1000; Vector Laboratories, UK) in PBS for 5 h. Subsequently, sections were rinsed in PBS three times again, and then incubated in TSA™ fluorescein tyramide in amplification solution (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA, for 15 min at room temperature.

After rinsing the sections in PBS three times they were incubated in PBS with 1% (w/v) BSA for 1 h and then with the second primary antibody solution (anti-rabbit-CART; Phoenix-Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 1:1500) in PBS containing 1% (w/v) BSA) for 24 h at room temperature. After rinsing in PBS three times, tetramethyl rhodamine isothiocyanate (TRITC) labeled donkey anti-rabbit IgG, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.) in PBS was applied for 12 h at room temperature. After washing in PBS three times, sections were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) for 15 min to counter stain cell chromatin. Then, sections were rinsed in PBS three times again and embedded in 8 μl anti-fading solution (100 mg/ml 1,4-diazabicyclo [2.2.2] octane (Sigma) in 90% (v/v) glycerine, 10% (v/v) PBS, pH 7.4), and analyzed using a confocal laser scanning microscope (cLSM 510 Meta).

2.5. Data and statistical analysis

Quantitative assessment of c-Fos immunoreactivity was achieved by counting the number of c-Fos immunopositive cells. Cells with green nuclear staining were considered c-Fos positive. Every third of all cconsecutive coronal 25 μm sections was counted for Fos-positive staining bilaterally in the PVN (bregma −1.30 to −2.12 mm), ARC (bregma −2.12 to −3.60 mm), and NTS (bregma −13.24 to −14.30 mm) according to the coordinates by Paxinos and Watson [27]. The other sections were used for immunhistochemical double labeling for c-Fos and CART peptide. The investigator counting the number of c-Fos and CART-immunoreactive (ir) neurons was blinded to treatments received by the animals. The average number of Fos-positive cells/section for the brain nuclei mentioned above was calculated for four rats/experimental group.

Quantitative assessment of c-Fos and CART immunoreactivity was achieved by counting the total number of c-Fos, CART and doubled labeled neurons in the PVN. Thereafter, the percentage of CART neurons which were also immunoreactive for c-Fos was calculated. All data are presented as mean ± SEM, and analyzed by Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA on ranks. Differences between groups were evaluated by the Student–Newman–Keuls method, with p < 0.05 considered significant.

3. Results

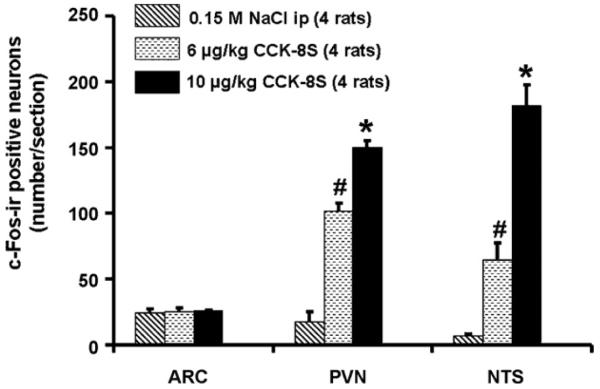

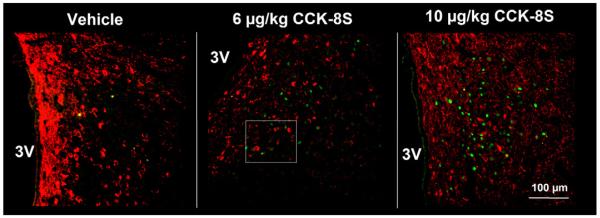

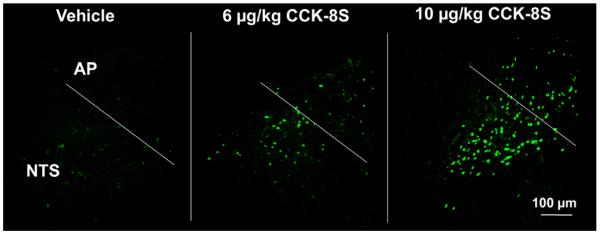

CCK-8S at doses of 6 and 10 μg/kg administered ip induced a 5–7-fold increase in the number of c-Fos-ir neurons in the PVN (mean ± SEM: 102 ± 6, p < 0.05, and 150 ± 5 neurons/section) compared to vehicle-treated animals (18 ± 7 neurons/section, p < 0.05; Figs. 1 and 4). The number of c-Fos-positive neurons in the PVN was dose-dependently increased after CCK-8S (6 or 10 μg/kg) injection. In contrast, CCK-8S at both doses injected ip had no effect on neuronal activity in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus compared to the vehicle-treated animals (Figs. 1 and 2). CCK-8S at both doses injected ip also induced a significant rise in the number of c-Fos labeled neurons in nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) of the brainstem compared to the vehicle group (CCK8-S 6 μg: 65 ± 13 neurons/section, CCK8-S 10 μg: 182 ± 16 neurons/section vs. vehicle: 7 ± 1 neurons/section, p < 0.05; Figs. 1 and 6).

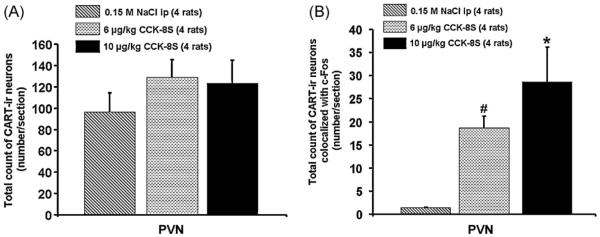

Fig. 1.

CCK-8S injected intraperitoneally increases the number of c-Fos-positive neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN) and in the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS), whereas no effects were observed in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus (ARC). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM of the number of rats indicated in parentheses. *p < 0.05 vs. 6 μg/kg CCK-8S and vs. vehicle; #p < 0.05 vs. 10 μg/kg CCK-S and vs. vehicle.

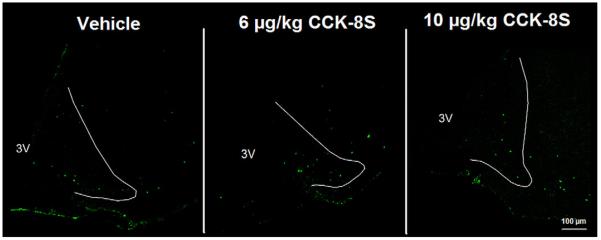

Fig. 4.

Double labeled neurons at low magnification with antibodies against c-Fos (green staining) and CART (red staining) in the paraventricular nucleus 90 min after intraperitoneal injection of vehicle, 6 or 10 μg/kg CCK-8S. 3V, third brain ventricle. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of the article.).

Fig. 2.

In the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus (ARC) no effects were observed on the number of activated neurons (green staining) at both doses of CCK-8S. The white outer line delineates the area of the ARC. 3V, third brain ventricle.

Fig. 6.

CCK-8S injected intraperitoneally at both doses (6 and 10 μg/kg) significantly increases the number of c-Fos-positive neurons in the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) in a dose-dependent manner. AP, area postrema.

In the PVN we found (mean ± SEM) 116 ± 11 CART-ir neurons per section. No significant effects on the number of CART neurons between the treatment groups were observed in present study (p > 0.05; Fig. 3). CART neurons were predominantly distributed in the parvocellular part of the PVN, and in the periventricular zone in close proximity to the third ventricle (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Total number of CART-immunoreactive neurons in all treatment groups in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (A) as well as number of double labeled neurons (c-Fos/CART) in the PVN (B). Double staining revealed that CCK-8S significantly and dose-dependently increased the number of c-Fos-positive CART cells in the PVN. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM of the number of rats indicated in parentheses.

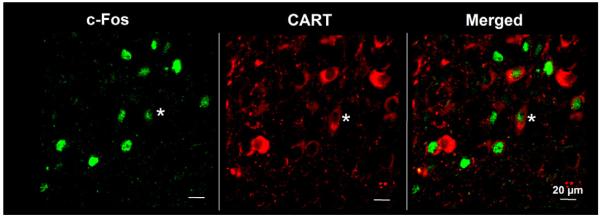

Double staining for c-Fos and CART revealed that peripherally injected CCK-8S significantly and dose-dependently increased the number of c-Fos-positive and CART-ir cells in the PVN (mean ± SEM: 19 ± 3 neurons/section and 29 ± 7 neurons/section; p < 0.05 respectively) and compared to vehicle-treated rats (1 ± 0 neurons/sections; p < 0.05 Figs. 3, 4 and 5), corresponding to 16.7 ± 0.4% and 24.9 ± 3.5% of CART neurons respectively being also positive for c-Fos. Assessment of double staining with anti-c-Fos and anti-CART revealed that CART immunoreactivity could only be observed in the cytoplasm and axons, whereas c-Fos was localized within the nucleus of activated PVN neurons (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Magnification of c-Fos-positive neurons co-localized with CART immunoreactivity in the PVN after injection of 6 μg/kg CCK-8S (the region of the magnification is indicated in Fig. 4).

4. Discussion

In the present study we show that intraperitoneal injection of CCK-8S (6 and 10 μg/kg) induces a dose-dependent neuronal activation (assessed by c-Fos immunohistochemistry) of CART immunoreactive cells in the PVN of ad libitum fed rats.

The PVN plays a key role in the activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis as well as in the modulation of food intake. After injection of CCK-8S, the number of c-Fos-positive neurons in the PVN increased [15,22,23,26], whereas no modulation could be observed in the ARC. The lack of CCK8-S's effect on the activation of neurons in the ARC has been reported before [15]. Previous studies on the neuropeptidergic phenotype of activated PVN neurons revealed that these contain CRF, oxytocin (OT) and nesfatin-1 immunoreactivity [23,39]. These three neuropeptides have a strong inhibitory effect on food intake when injected into the lateral or third brain ventricle [18,24,25].

The CART peptide is widely distributed in the rodent brain, being expressed in the ARC, PVN, and dorsomedial hypothalamus, among others [2,16,17]. It has been described that CART peptides reduce food intake in rodents when injected into the third brain ventricle [19,42]. These experiments imply a relevance of CART in the regulation of food intake. Recently, it has been shown that in fasted mice, the inhibitory effect of CART peptide on food intake injected icv can be increased by ip injection of low doses of CCK-8S [21] indicating a synergistic interaction of these two peptides. The observation that the inhibitory effect of CART on food intake in these animals can be abolished by systemic co-administration of the CCKA receptor antagonist, devazepide is of particular interest [21] and points towards a crucial role of CCK in the CART-mediated reduction of food intake. However, these studies also emphasize the potential role of CART peptides in the CCK-induced inhibitory modulation of food intake.

In light of these findings it seems reasonable that we found a dose-dependent increase in the number of c-Fos immunoreactive CART neurons in the PVN after CCK-8S injection. Furthermore, it has been shown that icv injection of CART peptide causes activation of PVN neurons, and induced c-Fos synthesis in CRF- and OT-immunoreactive cells in this brain nucleus [40]. Additionally, icv injection of CART peptide induced an increase in corticosteroidand OT-plasma levels [40]. Interestingly, it has also been shown that peripherally injected CCK-8S increases serum adrenocorticotropic hormone and corticosterone levels as well as OT-plasma levels in mammals [5,12,13]. Therefore, one can speculate that CART signaling in the PVN may play a role for modulation of OT and CRF neurons localized in the PVN in response to systemic CCK-8S administration. It appears conceivable that the inhibitory effect on food intake and the activation of the HPA-axis by peripheral CCK-8S is mediated partially via CART-PVN neurons although the neuronal mechanisms leading to an activation of CART neurons are yet to be established.

We observed that CART neurons activated by injection of CCK-8S were located predominantly in the parvocellular portion of the PVN. In this part of the PVN, large numbers of CRF and nesfatin-1-ir neurons can be detected as well [23]. We hypothesize that CART neurons may be co-localized with nesfatin-1 and/or CRF neurons. All these peptides inhibit food intake [18,24,38]. Further studies are needed to investigate possible synergistic inhibitory effects.

There is evidence that catecholaminergic as well as non-catecholaminergic cells from the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) project to hypothalamic brain areas [31,34–36]. Interestingly, PVN neurons activated by peripheral CCK-8S receive noradrenergic input from the A2-cell group in the NTS [32]. Therefore, it is likely that systemic CCK-8S-induced neuronal activation of CART cells and other neurons in the PVN is – at least in part – mediated by signals from noradrenergic NTS neurons. In line with this assumption, we observed a dose-dependent activation of the NTS following ip CCK8-S. However, the detailed physiological relevance of CART peptides in the PVN and its interaction with CCK-8S needs further investigation.

In conclusion, the present study shows that intraperitoneal injection of CCK-8S at two doses (6 and 10 μg/kg) dose-dependently increases neuronal activation in the PVN, as assessed by changes in c-Fos immunoreactivity. A considerable sub-population of these activated neurons in the PVN was CART immunopositive. The activation of CART-ir neurons in the PVN by peripheral CCK-8S suggests that the effect of CCK-8S on food intake and on the HPA-axis could – at least in part – be mediated by CART peptide.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the German Research Foundation to P.K (DFG KO 3864/2-1), and from Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin to P.K (UFF 09/41730 and 09/42458) as well as Veterans Administration Research Career Scientist Award (Y.T), Veterans Administration Merit Award (Y.T), NIHDK 33061 (Y.T), Center Grant DK-41301 (Animal Core) (Y.T.).

References

- [1].Asakawa A, Inui A, Yuzuriha H, Nagata T, Kaga T, Ueno N, et al. Cocaine-amphetamine-regulated transcript influences energy metabolism, anxiety and gastric emptying in mice. Horm Metab Res. 2001;33:554–8. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-17205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Balkan B, Koylu E, Pogun S, Kuhar MJ. Effects of adrenalectomy on CART expression in the rat arcuate nucleus. Synapse. 2003;50:14–9. doi: 10.1002/syn.10213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Barrachina MD, Martinez V, Wang L, Wei JY, Taché Y. Synergistic interaction between leptin and cholecystokinin to reduce short-term food intake in lean mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10455–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Buffa R, Solcia E, Go VL. Immunohistochemical identification of the cholecystokinin cell in the intestinal mucosa. Gastroenterology. 1976;70:528–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Calogero AE, Nicolosi AM, Moncada ML, Coniglione F, Vicari E, Polosa P, et al. Effects of cholecystokinin octapeptide on the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis function and on vasopressin, prolactin and growth hormone release in humans. Neuroendocrinology. 1993;58:71–6. doi: 10.1159/000126514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Chen DY, Deutsch JA, Gonzalez MF, Gu Y. The induction and suppression of c-fos expression in the rat brain by cholecystokinin and its antagonist L364,718. Neurosci Lett. 1993;149:91–4. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90355-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Couceyro PR, Koylu EO, Kuhar MJ. Further studies on the anatomical distribution of CART by in situ hybridization. J Chem Neuroanat. 1997;12:229–41. doi: 10.1016/s0891-0618(97)00212-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Day HE, McKnight AT, Poat JA, Hughes J. Evidence that cholecystokinin induces immediate early gene expression in the brainstem, hypothalamus and amygdala of the rat by a CCKA receptor mechanism. Neuropharmacology. 1994;33:719–27. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(94)90111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Eysselein VE, Eberlein GA, Hesse WH, Singer MV, Goebell H, Reeve JR., Jr Cholecystokinin-58 is the major circulating form of cholecystokinin in canine blood. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:214–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Gibbs J, Young RC, Smith GP. Cholecystokinin decreases food intake in rats. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1973;84:488–95. doi: 10.1037/h0034870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Gibbs J, Young RC, Smith GP. Cholecystokinin elicits satiety in rats with open gastric fistulas. Nature. 1973;245:323–5. doi: 10.1038/245323a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Haley GE, Flynn FW. Tachykinin neurokinin 3 receptor signaling in cholecystokinin-elicited release of oxytocin and vasopressin. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;294:R1760–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00033.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kamilaris TC, Johnson EO, Calogero AE, Kalogeras KT, Bernardini R, Chrousos GP, et al. Cholecystokinin-octapeptide stimulates hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal function in rats: role of corticotropin-releasing hormone. Endocrinology. 1992;130:1764–74. doi: 10.1210/endo.130.4.1312423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kobelt P, Tebbe JJ, Tjandra I, Bae HG, Rüter J, Klapp BF, et al. Two immunocyto-chemical protocols for immunofluorescent detection of c-Fos positive neurons in the rat brain. Brain Res Brain Res Protoc. 2004;13:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresprot.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kobelt P, Tebbe JJ, Tjandra I, Stengel A, Bae HG, Andresen V, et al. CCK inhibits the orexigenic effect of peripheral ghrelin. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;288(3):R751–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00094.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Koylu EO, Couceyro PR, Lambert PD, Ling NC, DeSouza EB, Kuhar MJ. Immunohistochemical localization of novel CART peptides in rat hypothalamus, pituitary and adrenal gland. J Neuroendocrinol. 1997;9:823–33. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1997.00651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Koylu EO, Weruaga E, Balkan B, Alonso JR, Kuhar MJ, Pogun S. Co-localization of cart peptide immunoreactivity and nitric oxide synthase activity in rat hypothalamus. Brain Res. 2000;868:352–7. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02290-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Krahn DD, Gosnell BA, Levine AS, Morley JE. Behavioral effects of corticotropin-releasing factor: localization and characterization of central effects. Brain Res. 1988;443:63–9. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)91598-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kristensen P, Judge ME, Thim L, Ribel U, Christjansen KN, Wulff BS, et al. Hypothalamic CART is a new anorectic peptide regulated by leptin. Nature. 1998;393:72–6. doi: 10.1038/29993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Larsson LI, Rehfeld JF. Localization and molecular heterogeneity of cholecystokinin in the central and peripheral nervous system. Brain Res. 1979;165:201–18. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90554-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Maletinska L, Maixnerova J, Matyskova R, Haugvicova R, Pirnik Z, Kiss A, et al. Synergistic effect of CART (cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript) peptide and cholecystokinin on food intake regulation in lean mice. BMC Neurosci. 2008;9:101. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-9-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Mönnikes H, Lauer G, Arnold R. Peripheral administration of cholecystokinin activates c-fos expression in the locus coeruleus/subcoeruleus nucleus, dorsal vagal complex and paraventricular nucleus via capsaicin-sensitive vagal afferents and CCK-A receptors in the rat. Brain Res. 1997;770:277–88. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00865-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Noetzel S, Stengel A, Inhoff T, Goebel M, Wisser AS, Bannert N, et al. CCK-8S activates c-Fos in a dose-dependent manner in nesfatin-1 immunoreactive neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus and in the nucleus of the solitary tract of the brainstem. Regul Pept. 2009;157:84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Oh-I S, Shimizu H, Satoh T, Okada S, Adachi S, Inoue K, et al. Identification of nesfatin-1 as a satiety molecule in the hypothalamus. Nature. 2006;443:709–12. doi: 10.1038/nature05162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Olson BR, Drutarosky MD, Chow MS, Hruby VJ, Stricker EM, Verbalis JG. Oxytocin and an oxytocin agonist administered centrally decrease food intake in rats. Peptides. 1991;12:113–8. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(91)90176-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Olson BR, Hoffman GE, Sved AF, Stricker EM, Verbalis JG. Cholecystokinin induces c-fos expression in hypothalamic oxytocinergic neurons projecting to the dorsal vagal complex. Brain Res. 1992;569:238–48. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90635-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Academic Press; San Diego: 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Reeve JR, Jr, Eysselein VE, Ho FJ, Chew P, Vigna SR, Liddle RA, et al. Natural and synthetic CCK-58. Novel reagents for studying cholecystokinin physiology. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1994;713:11–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb44047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Rehfeld JF. Neuronal cholecystokinin: one or multiple transmitters? J Neurochem. 1985;44:1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1985.tb07105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Rehfeld JF, Hansen HF, Marley PD, Stengaard-Pedersen K. Molecular forms of cholecystokinin in the brain and the relationship to neuronal gastrins. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1985;448:11–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1985.tb29902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Ricardo JA, Koh ET. Anatomical evidence of direct projections from the nucleus of the solitary tract to the hypothalamus, amygdala, and other forebrain structures in the rat. Brain Res. 1978;153:1–26. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(78)91125-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Rinaman L, Hoffman GE, Dohanics J, Le WW, Stricker EM, Verbalis JG. Cholecystokinin activates catecholaminergic neurons in the caudal medulla that innervate the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus in rats. J Comp Neurol. 1995;360:246–56. doi: 10.1002/cne.903600204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Ritter RC, Ladenheim EE. Capsaicin pretreatment attenuates suppression of food intake by cholecystokinin. Am J Physiol. 1985;248:R501–4. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1985.248.4.R501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Sawchenko PE, Benoit R, Brown MR. Somatostatin 28-immunoreactive inputs to the paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei: principal origin from non-aminergic neurons in the nucleus of the solitary tract. J Chem Neuroanat. 1988;1:81–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Sawchenko PE, Swanson LW. Central noradrenergic pathways for the integration of hypothalamic neuroendocrine and autonomic responses. Science. 1981;214:685–7. doi: 10.1126/science.7292008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Sawchenko PE, Swanson LW. The organization of noradrenergic pathways from the brainstem to the paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei in the rat. Brain Res. 1982;257:275–325. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(82)90010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Smith GP, Jerome C, Gibbs J. Abdominal vagotomy does not block the satiety effect of bombesin in the rat. Peptides. 1981;2:409–11. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(81)80096-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Stanley SA, Small CJ, Murphy KG, Rayes E, Abbott CR, Seal LJ, et al. Actions of cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript (CART) peptide on regulation of appetite and hypothalamo-pituitary axes in vitro and in vivo in male rats. Brain Res. 2001;893:186–94. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)03312-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Verbalis JG, Stricker EM, Robinson AG, Hoffman GE. Cholecystokinin activates c-Fos expression in hypothalamic oxytocin and corticotropin-releasing hormon neurons. J Neuroendocrinol. 1991;3:205–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.1991.tb00264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Vrang N, Larsen PJ, Kristensen P, Tang-Christensen M. Central administration of cocaine-amphetamine-regulated transcript activates hypothalamic neuroendocrine neurons in the rat. Endocrinology. 2000;141:794–801. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.2.7295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Vrang N, Tang-Christensen M, Larsen PJ, Kristensen P. Recombinant CART peptide induces c-Fos expression in central areas involved in control of feeding behaviour. Brain Res. 1999;818:499–509. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)01349-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Wang C, Billington CJ, Levine AS, Kotz CM. Effect of CART in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus on feeding and uncoupling protein gene expression. Neuroreport. 2000;11:3251–5. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200009280-00040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Woods SC, Seeley RJ, Porte D, Jr, Schwartz MW. Signals that regulate food intake and energy homeostasis. Science. 1998;280:1378–83. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5368.1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Zittel TT, Glatzle J, Kreis ME, Starlinger M, Eichner M, Raybould HE, et al. C-fos protein expression in the nucleus of the solitary tract correlates with cholecystokinin dose injected and food intake in rats. Brain Res. 1999;846:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01842-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]