Abstract

Objective

Vitamin D deficiency has been linked to the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Given the demonstrated anti-inflammatory function of Vitamin D in multiple organ systems including trophoblast cells and placenta, we hypothesized that Vitamin D deficiency contributes to the development of preeclampsia through increased inflammation, as indicated by elevated interleukin-6 (IL-6) concentrations.

Study Design

Plasma samples from a large preeclampsia cohort study were examined in 100 preeclamptic and 100 normotensive pregnant women. Comparisons of Vitamin D and IL-6 concentrations used Student t-test and Chi-square test or their non-parametric counterparts. A logistic regression model assessed the association between Vitamin D, IL-6 concentrations and the preeclampsia risk.

Results

The mean concentration of 25(OH)D was 49.4 ± 22.6 nmol/L in normotensives and 42.3 ± 17.3 nmol/L in preeclamptic women, (p = 0.01). The median (interquartile range: Q1, Q3) concentrations of IL-6 were 2.0 (1.3, 3.4) pg/ml and 4.4 (2.2, 10.0) pg/ml in the control and preeclampsia groups, respectively (p < 0.01). We observed a significant association between IL-6 elevation and preeclampsia (odd ratio = 4.4, 95% CI (1.8, 10.8), p < 0.01) and between Vitamin D deficiency and preeclampsia (odd ratio = 4.2, 95%CI (1.4, 12.8), p = 0.04). However, there was no association between Vitamin D deficiency and IL-6 elevation.

Conclusion

Third trimester IL-6 elevation and Vitamin D deficiency were independently associated with the risk of preeclampsia. We found no evidence to support the hypothesis that Vitamin D deficiency alters the pathogenesis of preeclampsia by activation of inflammation as assessed by IL-6 concentration.

Keywords: IL-6, inflammation, Vitamin D, preeclampsia, pregnancy

Introduction

Preeclampsia is a multisystemic pregnancy disorder diagnosed clinically by new onset gestational hypertension and proteinuria. It occurs in 3-5% of all pregnancies worldwide and is a major cause of maternal, fetal, and neonatal morbidity and mortality. Despite recent progress toward the understanding of the pathophysiology of preeclampsia, the disorder remains a challenge with no preventive therapy and effective treatment limited to delivery to terminate pregnancy and the disorder. A current model of the pathophysiology of preeclampsia invokes a two stage model [1, 2]; decreased placental perfusion usually secondary to abnormal trophoblastic invasion with consequent failed dilatory remodeling of maternal vessels perfusing the placenta that precedes and results in the clinical manifestations of preeclampsia. Multiple factors have been indicated in the initiation and progression of preeclampsia, including maternal constitutional factors, antiangiogenic factors, endothelial dysfunction, syncytiotrophoblast microparticles (STBM) and inflammatory activation [2].

On the journey of discovering the underlying mechanisms that cause preeclampsia, Vitamin D deficiency has been linked with an increased risk of preeclampsia. Maternal Vitamin D deficiency is associated with a 5-fold increase in the odds of preeclampsia compared with normotensive controls [3]. Vitamin D is well known for its function in maintaining normal blood concentration of phosphorus and calcium. However, it also has important roles in other cellular responses that could be relevant to preeclampsia. Vitamin D influences inflammatory responses outside of pregnancy. For example, women deficient in Vitamin D have higher IL-6 levels after hip fracture repair [4]. In human coronary arterial endothelial cells, pretreatment with Vitamin D significantly inhibits the TNF-α-induced downstream signaling pathways [5].

Human trophoblasts both produce and respond to the active form of Vitamin D, 1,25(OH)2D. The concentration of 1,25(OH)2D is tightly regulated by the Vitamin D activating enzyme 1α-hydroxylase (CYP27B1) and the degradation enzyme 24-hydroxylase (CYP24A1). Both enzymes are expressed in human placenta. The activated 1,25(OH)2D mediates its actions through specific Vitamin D receptors -- VDR, which are expressed in both decidua and trophoblast. Recent pregnancy-related studies indicate that Vitamin D inhibits the mRNA transcription of inflammatory cytokine genes (TNFα, IFNγ and IL-6) in trophoblast cell culture systems [6]. Immune challenge by LPS (lipopolysaccharide) induces the expression of VDR and CYP27B1 along with cytokines such as IL-6 in placenta; up-regulation of IL-6 is further enhanced in CYP27B1 or VDR knockout mice [7]. Given the demonstrated anti-inflammatory function of Vitamin D in multiple organ systems including trophoblast cells and placenta, we hypothesized that Vitamin D deficiency contributes to the development of preeclampsia through increased inflammation.

Among the inflammatory markers that are increased in preeclampsia, IL-6 has been consistently indicated to be present at higher serum concentrations in preeclamptic patients than in normal pregnant women [8-14]. Therefore we chose IL-6 as the marker of inflammation in our study. We tested whether the association between Vitamin D deficiency and preeclampsia risk is dependent on increased inflammation, as indicated by elevated IL-6 concentrations when vitamin D deficiency is associated preeclampsia (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Hypothesis for the mediation of Vitamin D deficiency by increased inflammation.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

We used banked plasma samples collected as part of a large preeclampsia cohort study and conducted a retrospective study on a total of 100 women with preeclampsia and 100 normotensive pregnant women. Blood samples were collected at ≥24 week gestation from nulliparous women carrying a singleton pregnancy. The 100 preeclampsia samples were randomly selected from samples collected from women with preeclampsia in a study approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board. These cases were matched by maternal age, gestational age at blood sampling, BMI, maternal race/ethnicity and smoking status to a computer-generated randomized, control group of 100 uncomplicated pregnancies from the same study.

Preeclampsia was defined as the new onset of hypertension and proteinuria after 20 weeks of gestation. Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure greater or equal to 140 mmHg and/or diastolic pressure greater than or equal to 90 mmHg, and/or an increase of greater than 30 systolic and/or an increase of greater than 15 diastolic. Proteinuria was defined as urine protein greater than 300mg/24hr or 2+ dipstick or a protein/creatinine ratio greater than 0.3. Among the 100 preeclamptic patients, 3 patients developed blood pressures greater than 30 systolic and/or 15 diastolic without being greater than or equal to 140 and/or 90. 15 also meet at least one of the criteria for HELLP syndrome, namely hemolysis (serum total bilirubin concentration of 1.2 mg/dL or greater, serum LDH concentration of 600 IU/L or greater, or hemolysis determined by peripheral blood smear), elevated liver function (aspartate aminotransferase ≥ 70 IU/L) and thrombocytopenia (<100,000/mm3). There were an additional 3 patients who met all criteria for HELLP syndrome.

IL-6 Assay

IL-6 was measured by high sensitivity Human IL-6 immunoassay kit (R&D systems, UK). The minimal detectable concentration was less than 0.7 pg/ml, and the inter-assay coefficient of variation was 7%. In order to ascertain if the highest IL6 values in preeclamptic women were associated with the lowest vitamin D concentrations, we defined elevated IL-6 as plasma concentrations within the highest quartile of the 100 preeclamptic samples. Concentrations were calculated by averaging values between two duplicates. Samples with absorbance readings out of the range of standard curve were repeated with appropriate titration. Two values (1%) were censored due to the lower limit of detection (0.7 pg/ml) and substituted with half of the detection limit for statistical analysis.

Vitamin D assay

Plasma Vitamin D concentrations were determined by 25-OH-D assay kit (DiaSorin, Stillwater, MN) with inter-assay coefficient of variation 7-11%. We defined Vitamin D deficiency if the serum concentrations were less than 37.5 nmol/L; Vitamin D insufficiency if they were less than 75 nmol/L [3]. Concentrations were calculated by averaging values between two duplicates.

Statistical analyses

Vitamin D concentrations are presented as the means ± SD; IL-6 data are presented as median and interquartile range (Q1, Q3) because the data were substantially skewed. The comparisons between Vitamin D, IL-6 concentrations in two study groups were conducted using Student t-test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test as non-parametric counterparts. Proportions of Vitamin D deficiency and IL-6 elevation were calculated for both the control and preeclampsia groups, and assessed by Chi-square test. A logistic regression model was used to assess the relationship of Vitamin D, and IL-6 concentrations with preeclampsia risk. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) assuming statistical significance at p<0.05. The prevalence of coexisting IL-6 elevation and Vitamin D deficiency in the preeclampsia group was specifically studied. A random association between the two variables would yield a frequency equal to the product of high IL-6 frequency and low Vitamin D frequency. A difference in the prevalence would indicate a relationship between Vitamin D and IL-6 in preeclampsia. With a sample of 100 in each study group, the current study had 80% statistical power to detect a 1.2-fold difference in prevalence of patients with IL-6 elevation and Vitamin D deficiency between random vs. non-random association with the use of a two-sided test at the 0.05 significance level.

Results

Demographic and biochemical data are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences between normotensive controls and preeclamptic women in maternal age, BMI, gestational age at blood sampling, ethnicity or smoking status. All women in this study were nulliparous. Average gestational age at delivery from the preeclampsia group was 4.9 weeks earlier than that of the control group. This disparity was secondary to higher incidence of spontaneous and induced preterm birth in women with preeclampsia.

Table 1. Characteristics of women with and without preeclampsia.

| ALL (n=200) | Non-preeclamptic (n=100) | Preeclamptic (n=100) | p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (year), mean(SD) | 25.7(5.7) | 25.5 (5.5) | 26.0 (5.9) | 0.60 |

|

| ||||

| BMI (kg/m2), mean(SD) | 26.8(5.9) | 26.7 (5.6) | 27.0 (6.3) | 0.76 |

|

| ||||

| Gestational age at blood collection (wk), mean(SD) | 34.8(4.0) | 34.7 (4.0) | 34.9 (4.0) | 0.68 |

|

| ||||

| Gestational age at delivery (wk), mean(SD) | 37.4(3.8) | 39.9 (1.1) | 35.0 (4.0) | < 0.01 |

|

| ||||

| Maternal race/ethnicity, n(%) | 0.87 | |||

| White | 168(84.0) | 84(84.0) | 84(84.0) | |

| Black | 31(15.5) | 16(16.0) | 15(15.0) | |

| Asian | 1(0.5) | 0 | 1 | |

|

| ||||

| Smoking status, n(%) | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 48(24.0) | 24(24.0) | 24(24.0) | |

| No | 138(69.0) | 69(69.0) | 69(69.0) | |

| unknown | 14(7.0) | 7(7.0) | 7(7.0) | |

Student's t-test for continuous variables and Chi-squared test for categorical variables.

Table 2 outlines the mean concentrations of maternal Vitamin D in the normal pregnancy group and the preeclamptic group. Of the 100 controls, the mean concentration of 25(OH)D was 49.4 ± 22.6 nmol/L. Thirty subjects had severe Vitamin D deficiency, with 25(OH)D concentrations below 37.5 nmol/L; 54 had Vitamin D insufficiency, with 25(OH)D concentrations between 37.5-75 nmol/L; the remaining 16 had normal Vitamin D concentrations (above 75 nmol/L). In the preeclampsia group, the mean concentration of 25(OH)D was 42.3 ± 17.3 nmol/L. Patients who met at least one HELLP criteria were noted to have lower Vitamin D concentrations (40.1 ± 14.6 nmol/L). Among the 100 preeclamptic patients, 41% had severe Vitamin D deficiency, 54% had Vitamin D insufficiency and only 5% had normal Vitamin D concentrations. Plasma 25(OH)D concentrations were 14% lower in women with preeclampsia compared to those in controls (p = 0.01). We observed a positive association between Vitamin D deficiency and an increased risk for preeclampsia (p= 0.03) (Table 2).

Table 2. Plasma concentrations of Vitamin D and IL-6 at 35 weeks of gestation.

| ALL (n=200) | Non-preeclamptic (n=100) | Preeclamptic (n=100) | p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin D(nmol/L), | ||||

| All, mean (SD) | 45.8(20.4) | 49.4 (22.6) | 42.3(17.3) | 0.01 |

| ≥ 75 (%) | 21(10.5) | 16(16.0) | 5(5.0) | 0.03 |

| 37.5 – 75 (%) | 107(53.5) | 53(53.0) | 54(54.0) | |

| < 37.5 (%) | 72(36.0) | 31(31.0) | 41(41.0) | |

|

| ||||

| IL-6 (pg/ml) | ||||

| All, median (IQR)b | 2.7 (1.7, 6.3) | 2.0 (1.3, 3.4) | 4.4(2.2, 10.0) | < 0.01 |

| Elevated, n(%)c | 32(16.0) | 7(7.0) | 25(25.0) | < 0.01 |

| Normal, n (%) | 168(84.0) | 93(93.0) | 75(75.0) | |

Student's t-test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables and Chi-squared test for categorical variables.

median and interquartile range(IQR)= (Q1, Q3)

IL-6 (pg/ml) ≥ 10.0 (top 25% in the preeclamptic study group)

Median (Q1, Q3) concentrations of IL-6 were 2.0 (1.3, 3.4) pg/ml and 4.4 (2.2, 10.0) pg/ml in the control and preeclampsia groups, respectively (p < 0.01). 7% of the non-preeclamptic women were classified into the elevated IL-6 group based on the cutoff we defined, which was the upper quartile of women with preeclampsia (p < 0.01). Results are presented in Table 2.

Associations between IL-6, Vitamin D concentrations and the risk of preeclampsia were analyzed through logistic regression (Table 3). The odds for preeclampsia was four fold higher with elevated IL-6 (odd ratio = 4.43, 95% CI (1.82, 10.80), p =0.001). The odds of preeclampsia was tripled with Vitamin D insufficiency (odd ratio = 3.26, 95% CI (1.12, 9.54), p =0.038), and quadrupled with Vitamin D deficiency (odd ratio = 4.23, 95% CI (1.40, 12.81), p =0.038).

Table 3. Odds ratio for preeclampsia using categorized IL-6 and Vitamin D concentrations.

| OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Model1 (IL-6 only) | ||

| High IL-6 (≥ 10.0) | 4.4 (1.8, 10.8) | < 0.01 |

|

| ||

| Model2 (Vitamin D only) | ||

| Vitamin D(ref: normal (≥ 75) | 0.04 | |

| Vitamin D insufficiency (37.5 – 75) | 3.3 (1.1, 9.5) | |

| Vitamin D deficiency (<37.5) | 4.2 (1.4, 12.8) | |

|

| ||

| Model3 (IL-6 and Vitamin D) | ||

| High IL-6 | 4.4 (1.8, 1.1) | < 0.01 |

| Vitamin D(ref: normal (≥ 75) | 0.05 | |

| Vitamin D insufficiency (37.5 – 75) | 3.1 (1.0, 9.3) | |

| Vitamin D deficiency (<37.5) | 4.2 (1.4, 13.1) | |

|

| ||

| Model4 (IL-6, Vitamin D and interaction) | ||

| High IL-6 | 3.75(0.19,74.06) | 0.39 |

| Vitamin D(ref: normal (≥ 75) | 0.07 | |

| Vitamin D insufficiency (37.5 – 75) | 2.98(0.92,9.72) | |

| Vitamin D deficiency (<37.5) | 8.91(0.84,94.42) | |

| High IL-6 * Vitamin D | 0.98 | |

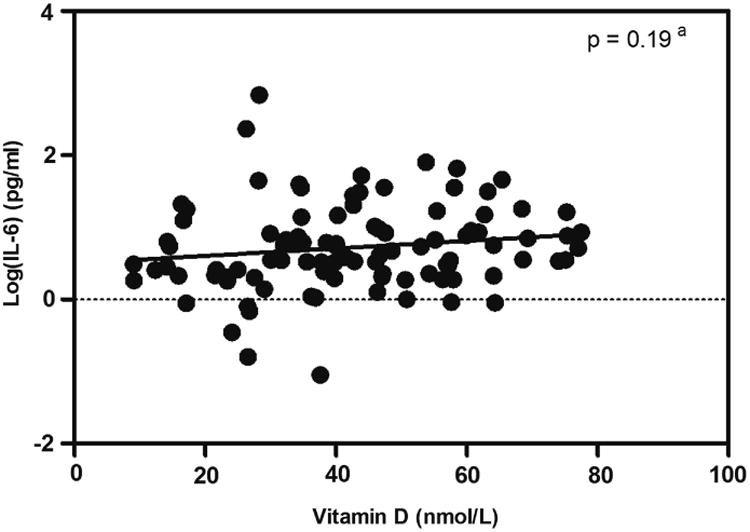

We used several strategies to test whether low Vitamin D was associated with high IL-6 in women with preeclampsia. First, the prevalence of IL-6 elevation in women with Vitamin D deficiency was not significantly different from those who were not Vitamin D deficient (27.1% vs. 22.0%, p = 0.56, Table 4). We then calculated the Spearman correlation coefficient between the ranked Vitamin D and IL-6 concentrations (ρ = 0.22, p = 0.03). The absence of a negative correlation did not support a relationship between high Vitamin D and low IL6 in women with preeclampsia. Furthermore, a linear regression model was applied to assess the association between Vitamin D and log transformed IL-6, and confirmed that high IL-6 concentrations was not significantly related to low Vitamin D concentrations (p = 0.19, Figure 2). Likewise, we performed these analyses using all 200 subjects including women with or without preeclampsia as well as 100 control subjects, and did not observe any significant association between IL-6 elevation and Vitamin D deficiency.

Table 4. Prevalence of high IL-6 in Vitamin D deficient vs. non-deficient women using data of 100 women with preeclampsia.

| Vitamin D, n (%) | Vitamin D ≥ 37.5 nmol/L | Vitamin D <37.5 nmol/L | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| IL-6, n (%) | |||

| Normal IL-6 | 43 (72.9) | 32 (78.0) | 75 |

| Elevated IL-6 | 16 (27.1) | 9a (22.0) | 25 |

|

| |||

| Total | 59 | 41 | 100 |

p-value = 0.56 from Chi-square test

Observed prevalence of concomitant IL-6 elevation and Vitamin D deficiency = 9%; Expected prevalence = 10.3% (assuming that the relationship of IL-6 and Vitamin D was completely random)

Figure 2.

Scatter plot between the concentrations of IL-6 and Vitamin D in 100 women with preeclampsia. aRegression line and p-value from linear regression model

We also assessed the effect of interaction between IL-6 and Vitamin D concentrations in logistic regression. There was no significant interaction effect of the two analytes (p = 0.98, Table 3 Model 4) indicating that the association of Vitamin D with the risk of preeclampsia was the same at all IL-6 concentrations.

Additionally, the interdependence of hypovitaminosis D and IL-6 elevation was evaluated by testing the independence of this association in preeclampsia. We compared the observed number of patients with concurrent IL-6 elevation and hypovitaminosis D and the expected number of patients who would have low Vitamin D and high IL-6 if they were independent of each other. The prevalence of IL-6 elevation in preeclamptic samples by definition was 25%, and the prevalence of Vitamin D deficiency was 41%. If we assumed that the relationship of IL-6 and Vitamin D was completely random, the expected prevalence of concomitant IL-6 elevation and Vitamin D deficiency would be the product of 25% and 41%, 10.25%. Observed prevalence of patients with IL-6 elevation and Vitamin D deficiency higher than 10.25% would indicate a positive association between IL-6 elevation and Vitamin D deficiency. However, the observed prevalence in our data set was 9% (Table 4), supporting no positive relationship between IL-6 elevation and Vitamin D deficiency as indicated by the alternative analysis.

We also asked whether the relationship of low Vitamin D concentrations and high IL-6 might be present in early onset preeclampsia supporting a role for inflammation with hypovitaminosis D in this subset of preeclamptic women. We performed the analyses described above in 37 women with preeclampsia who delivered before 34 weeks gestation and controls marched for gestational age at sample collection. The findings in the total group of preeclamptics were replicated in this group. There was no difference in IL-6 prevalence at low or high Vitamin D concentration, no negative association of the two analytes by Spearman correlation coefficient estimation or linear regression model, and the distribution of high and low IL-6 and Vitamin D concentrations was as predicted by independent interactions (data not shown). (We were unable to test interactions by logistic regression since there were not sufficient observations for some categories in the logistic regression model.)

Comment

This large retrospective study assessed the association between Vitamin D deficiency, IL-6 elevation and the risk of preeclampsia. We found that the plasma concentrations of maternal 25(OH)D measured at an average of 35 week gestational age were statistically significantly lower in women with preeclampsia compared to non-preeclamptic controls and that IL-6 was higher. However our primary hypothesis (Figure 1) was not supported. The findings were not consistent with inflammation as measured by concentrations of IL-6 being on the causal pathway of vitamin D deficiency. The relationship of vitamin D to preeclampsia was not related to IL-6 concentration.

These findings are consistent with those from other studies. In a nested case control study [3], the mean maternal Vitamin D concentration of the preeclamptic women at delivery was 54.4 nmol/L, which was 15% lower than that of the normotensive pregnant women. In a prospective cohort study[15], the mean Vitamin D concentration at 24-26 weeks of gestation was 14% lower in preeclamptic women (48.9 nmol/L) compared to that of healthy women delivering at term (57.0 nmol/L). Maternal Vitamin D concentrations in our study were slightly lower than previous studies. This is likely due to different 25(OH)D assays, samples obtained at different gestational age and distinct patient characteristics. Importantly, the percentage difference between the preeclampsia and the control groups coincided with other studies [3, 15]. In our study, the mean maternal Vitamin D concentrations were 14% lower in women with preeclampsia compared with controls, which is similar to the difference found in prior studies.

Comparing plasma IL-6 concentrations in this study with those from previous studies was difficult, since values vary substantially across studies [16]. We did however confirm the association between higher IL-6 concentration and the incidence of preeclampsia. We demonstrated that plasma IL-6 at an average of 35 weeks of gestation was presented in higher concentrations in preeclamptic women compared to normotensive pregnant women; median concentrations were 4.4 pg/ml and 2.0 pg/ml, respectively (p<0.01, Table 2).

The pathogenesis of preeclampsia is complex. Vitamin D is one of the proposed risk factors. We hypothesized mediation of the increase in the risk of preeclampsia through increased inflammation as has been described in association with hypovitaminosis D in non-pregnant settings, such as in diabetic, post hip fracture and hemodialysis patients [4, 17, 18]. In vitro studies support these observations. Vitamin D inhibits TNFα induced inflammatory cytokines in human coronary endothelial cells [5]; Vitamin D deficiency was also connected with increased IL-6 concentrations through a stress-related kinase, p38 inactivation, in human prostatic epithelial cells [19]. These studies are all consistent with an anti-inflammatory role of Vitamin D. Nonetheless, we did not observe a significant association between Vitamin D deficiency and IL-6 elevation in our study population, regardless of how the IL-6 and 25(OH)D were specified in the model (linear, categorical).

Failure to observe an association between Vitamin D and inflammation could be related specifically to our choice of IL-6. Vitamin D might correlate with deficiencies of other inflammatory cytokines. The consistent relationship of IL-6 with preeclampsia [8-14] and with other cytokines in pregnancy [8-14] makes this unlikely. Vitamin D deficiency could contribute to the development of preeclampsia by other previously recognized actions of the Vitamin. Vitamin D may regulate the transcription and function of key target genes involved in placental invasion and implantation as implied by in vivo and in vitro studies [20]. There is also evidence that Vitamin D regulates angiogenesis through direct effects on VEGF gene transcription and release in vascular smooth muscle cells [21]. Alternatively, Vitamin D deficiency may have a role in blood pressure regulation through renin-angiotensin system [22].

Additionally, we must recognize that one of the assumptions of our hypothesis, that Vitamin D deficiency contributes to the development of preeclampsia, remains controversial. Results of human studies relating Vitamin D as a cause of preeclampsia are conflicting. Several studies found that maternal Vitamin D deficiency was associated with increased risk of preeclampsia [3, 23-25]. Previous studies from our group found that serum 25(OH)D concentrations at less than 22 week gestation and at delivery were lower in women with preeclampsia than in those with normotensive pregnancies. Three other studies found a similar significant association between Vitamin D deficiency and preeclampsia[15, 24, 25]. Furthermore, women with Vitamin D supplementation in early pregnancy reduced incidence of preeclampsia later in pregnancy [26, 27]. Studies on seasonal patterns demonstrated higher incidence of preeclampsia in winter than that in summer [28, 29], which would be predicted by the dependence of Vitamin D concentration on sunlight. In contrast, other studies found no association between Vitamin D status with or before preeclampsia and the incidence of preeclampsia [30-32].

Preeclampsia is proposed to be a two-stage disorder; clinical manifestations are preceded by reduced placental perfusion due to abnormal trophoblastic invasion, and subsequently ineffective vascular remodeling. These conflicting results of Vitamin D status and preeclampsia indicate that the causal relationship between Vitamin D and preeclampsia remains elusive and that Vitamin D may play a role preceding preeclampsia for example, at the stage of vascular remodeling. Therefore, it is possible that the association between Vitamin D deficiency and elevated inflammation only occurs in certain stages of pregnancy and was not revealed by our study in which blood samples were obtained at an average of 35 weeks of gestation.

A number of studies have observed elevated IL-6 concentration in preeclamptic pregnancies [8-14]. Blood samples from these studies were usually collected during the 3rd trimester or at the time of diagnosis of preeclampsia. In one study that measured IL6 in the first trimester, differences between controls and women who later became preeclamptic approached significance at this time but were clearly different in the third trimester[33]. Kronborg CA and colleagues [34] conducted a longitudinal study to measure cytokines from the 18th -19th week of gestation until delivery in both preeclamptic and non-preeclamptic women. Interestingly, they revealed that TNFα increased significantly between the 26th and 29th week in women with preeclampsia; whereas an increase of IL-6 concentrations exclusively occurred in preeclamptic samples obtained beyond 36 weeks. Though the sample size of this study was small, it was interesting to detect pregnancy-stage dependent associations between cytokines and preeclampsia. To further investigate our hypothesis whether the association between Vitamin D and preeclampsia is inflammation dependent, we suggest using additional inflammatory markers that might demonstrate differences at different stages of pregnancy.

Our study should be viewed with the following limitations. First, the retrospective design of studying women with clinical preeclampsia prevented establishing a causal relationship of Vitamin D with IL-6 and preeclampsia. Secondly, 1,25(OH)2D, the active metabolite of 25(OH)D was not measured in this study due to the short in vivo half-life. It is plausible that the absence of the association between Vitamin D deficiency and IL-6 elevation is secondary to distinctive activities of 1α-hydroxylase in placentas of preeclamptic or normotensive women. Furthermore, our patient population is predominantly Caucasian-Americans with 15.5% of African-Americans. We do not have sufficient data to compare among different races or to generalize our results to other ethnic groups. It is also evident that severe inflammation may actually reduce Vitamin D concentration perhaps by acute reductions in Vitamin D binding proteins[35]. This would question whether an association of low Vitamin D and increased inflammatory markers indicated that Vitamin D increases inflammation. However, this was clearly not the case in our study which found no association of Vitamin D and IL-6 supporting that Vitamin D does not increase inflammation (or vice versa) in preeclampsia and that there is no causal relationship. Despite these limitations, our study had several important strengths. Patient characteristics were meticulously matched by several important factors known to influence maternal Vitamin D concentrations, including obesity, smoking status, gestational age at sampling and race/ethnicity. We also examined a relatively large sample size to minimize confounder effects.

In this retrospective case-control study, third trimester IL-6 elevation and Vitamin D deficiency were independently associated with preeclampsia. Although Vitamin D is believed to play important immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory roles in multiple systems, we did not find any evidence to support for the hypothesis that Vitamin D deficiency alters the pathogenesis of preeclampsia by increasing inflammation as indicated by higher IL-6. Further investigation into the role of Vitamin D with larger sample size, different gestational age windows, and different inflammatory markers should be undertaken to improve our understanding on the development of preeclampsia.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the research staff in Dr. Roberts' laboratory for their assistance and contribution to the study.

Source of Support: National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant P01 HD30367 funded this work.

Abbreviations

- 25(OH)D

25-hydroxyvitamin D

- BMI

body mass index

- CYP27B1

Vitamin D activating enzyme 1α-hydroxylase

- HELLP

Hemolysis Elevated Liver enzymes and Low Platelet count

- IFNγ

interferon γ

- IL-6

interleukin-6

- LDH

lactate dehydrogenase

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- STBM

syncytiotrophoblast microparticles

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor-α

- VDR

Vitamin D receptor

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: All authors have no relevant conflict of interest to disclose, and there has been no previous presentation of the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Roberts JM, Gammill HS. Preeclampsia: recent insights. Hypertension. 2005;46(6):1243–9. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000188408.49896.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roberts JM, Hubel CA. The two stage model of preeclampsia: variations on the theme. Placenta. 2009;30 Suppl A:S32–7. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bodnar LM, et al. Maternal vitamin D deficiency increases the risk of preeclampsia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(9):3517–22. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller RR, et al. Association of serum vitamin D levels with inflammatory response following hip fracture: the Baltimore Hip Studies. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(12):1402–6. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.12.1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suzuki Y, et al. Anti-inflammatory effect of 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3) in human coronary arterial endothelial cells: Implication for the treatment of Kawasaki disease. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2009;113(1-2):134–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diaz L, et al. Calcitriol inhibits TNF-alpha-induced inflammatory cytokines in human trophoblasts. J Reprod Immunol. 2009;81(1):17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu NQ, et al. Vitamin D and the regulation of placental inflammation. J Immunol. 2011;186(10):5968–74. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Visser N, et al. Inflammatory changes in preeclampsia: current understanding of the maternal innate and adaptive immune response. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2007;62(3):191–201. doi: 10.1097/01.ogx.0000256779.06275.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma A, Satyam A, Sharma JB. Leptin, IL-10 and inflammatory markers (TNF-alpha, IL-6 and IL-8) in pre-eclamptic, normotensive pregnant and healthy non-pregnant women. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2007;58(1):21–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2007.00486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Casart YC, Tarrazzi K, Camejo MI. Serum levels of interleukin-6, interleukin-1beta and human chorionic gonadotropin in pre-eclamptic and normal pregnancy. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2007;23(5):300–3. doi: 10.1080/09513590701327638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borekci B, et al. Maternal serum interleukin-10, interleukin-2 and interleukin-6 in pre-eclampsia and eclampsia. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2007;58(1):56–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2007.00491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernardi F, et al. Oxidative stress and inflammatory markers in normal pregnancy and preeclampsia. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2008;34(6):948–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2008.00803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh A, et al. Role of inflammatory cytokines and eNOS gene polymorphism in pathophysiology of pre-eclampsia. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2010;63(3):244–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2009.00781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalinderis M, et al. Elevated serum levels of interleukin-6, interleukin-1beta and human chorionic gonadotropin in pre-eclampsia. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2011;66(6):468–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2011.01019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wei S, et al. Longitudinal vitamin D status in pregnancy and the risk of pre-eclampsia. BJOG. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2012.03307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conrad KP, Benyo DF. Placental cytokines and the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1997;37(3):240–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1997.tb00222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giulietti A, et al. Monocytes from type 2 diabetic patients have a pro-inflammatory profile. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D(3) works as anti-inflammatory. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;77(1):47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bednarek-Skublewska A, et al. Effects of vitamin D3 on selected biochemical parameters of nutritional status, inflammation, and cardiovascular disease in patients undergoing long-term hemodialysis. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2010;120(5):167–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nonn L, et al. Inhibition of p38 by vitamin D reduces interleukin-6 production in normal prostate cells via mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase 5: implications for prostate cancer prevention by vitamin D. Cancer Res. 2006;66(8):4516–24. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evans KN, et al. Vitamin D and placental-decidual function. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2004;11(5):263–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jsgi.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cardus A, et al. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 regulates VEGF production through a vitamin D response element in the VEGF promoter. Atherosclerosis. 2009;204(1):85–9. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li YC, et al. Vitamin D: a negative endocrine regulator of the renin-angiotensin system and blood pressure. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;89-90(1-5):387–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robinson CJ, et al. Plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels in early-onset severe preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(4):366 e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robinson CJ, et al. Maternal vitamin D and fetal growth in early-onset severe preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(6):556 e1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baker AM, et al. A nested case-control study of midgestation vitamin D deficiency and risk of severe preeclampsia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(11):5105–9. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haugen M, et al. Vitamin D supplementation and reduced risk of preeclampsia in nulliparous women. Epidemiology. 2009;20(5):720–6. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181a70f08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olsen SF, Secher NJ. A possible preventive effect of low-dose fish oil on early delivery and pre-eclampsia: indications from a 50-year-old controlled trial. Br J Nutr. 1990;64(3):599–609. doi: 10.1079/bjn19900063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bodnar LM, Catov JM, Roberts JM. Racial/ethnic differences in the monthly variation of preeclampsia incidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196(4):324 e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.TePoel MR, Saftlas AF, Wallis AB. Association of seasonality with hypertension in pregnancy: a systematic review. J Reprod Immunol. 2011;89(2):140–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2011.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shand AW, et al. Maternal vitamin D status in pregnancy and adverse pregnancy outcomes in a group at high risk for pre-eclampsia. BJOG. 2010;117(13):1593–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Powe CE, et al. First trimester vitamin D, vitamin D binding protein, and subsequent preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2010;56(4):758–63. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.158238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu CK, et al. Maternal serum vitamin D levels at 11-13 weeks of gestation in preeclampsia. J Hum Hypertens. 2012 doi: 10.1038/jhh.2012.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Freeman DJ, et al. Short- and long-term changes in plasma inflammatory markers associated with preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2004;44(5):708–714. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000143849.67254.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kronborg CS, et al. Longitudinal measurement of cytokines in pre-eclamptic and normotensive pregnancies. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2011;90(7):791–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reid D, et al. The relation between acute changes in the systemic inflammatory response and plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations after elective knee arthroplasty. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2011;93(5):1006–11. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.008490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]