Abstract

Background

WHO recommends birth spacing to improve the health of the mother and child. One strategy to facilitate birth spacing is to improve the use of family planning during the first year postpartum.

Objectives

To determine from the literature the effectiveness of postpartum family-planning programs and to identify research gaps.

Search strategy

PubMed and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials were systematically searched for articles published between database inception and March 2013. Abstracts of conference presentations, dissertations, and unpublished studies were also considered.

Selection criteria

Published studies with birth spacing or contraceptive use outcomes were included.

Data collection and analysis

Standard abstract forms and the US Preventive Services Task Force grading system were used to summarize and assess the quality of the evidence.

Main results

Thirty-four studies were included. Prenatal care, home visitation programs, and educational interventions were associated with improved family-planning outcomes, but should be further studied in low-resource settings. Mother–infant care integration, multidisciplinary interventions, and cash transfer/microfinance interventions need further investigation.

Conclusions

Programmatic interventions may improve birth spacing and contraceptive uptake. Larger well-designed studies in international settings are needed to determine the most effective ways to deliver family-planning interventions.

Keywords: Birth spacing, Family planning, Postpartum period, Programmatic interventions, Rapid repeat birth, Systematic review, Teen pregnancy

1. Introduction

An estimated 222 million women in lower-income regions of the world want to avoid a pregnancy but use either a low-efficacy family-planning method or no method, indicating an unmet need for family planning [1]. A 2010 analysis of Demographic and Health Survey data from 17 countries [2] demonstrated that 50–88% of women in the first year postpartum would like to avoid pregnancy but are not using contraception.

Policy efforts for providing family-planning services to postpartum women have primarily focused on the first 6 weeks after delivery, but the extension of services through the first year postpartum is likely to further improve birth spacing. WHO [3] recommends an interval of 24 months or more before attempting a next pregnancy after a live birth, to reduce the risks of adverse outcomes for mother and child.

Various interventions have been pursued to improve postpartum family planning; however, a systematic synthesis of the efficacy of these programs is not available. Therefore, we conducted a systematic review of the literature to describe and classify the existing literature and programs, to determine the efficacy of the various programs, and to assess the quality of research on these programs. The present systematic review summarizes postpartum family-planning interventions in order to inform program design and identify priorities for future research activities.

2. Materials and methods

Studies evaluating the effectiveness of interventions to prevent short interpregnancy intervals or to increase postpartum contraceptive use were included in the present review. Informed consent was not needed for this research because no human subjects research was conducted. Inclusion criteria for the present review included the following study designs: randomized controlled trials, case–control studies, cross-sectional studies, and cohort studies. The primary outcome of interest was the interpregnancy interval. A secondary outcome was contraceptive use.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines [4] were followed. The PubMed and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials databases were systematically searched for articles published between inception of the respective database and March 31, 2013. Articles in all languages were accepted. Abstracts of conference presentations, dissertations, and unpublished studies were also considered. Reference lists of identified articles and relevant review articles were hand-searched for additional citations. The search strategy appears in Supplementary Material S1.

Two authors (S.S., S.M.) summarized and systematically assessed the evidence. The quality of each individual piece of evidence was assessed using the US Preventive Services Task Force grading system [5]. Risk of bias was assessed by considering the randomization method, allocation concealment, blinding, control for potential confounding factors, adequacy of statistical procedures, and losses to follow-up and early discontinuation.

Studies were included if interventions took place in the prepartum period or within the first year postpartum, and if the family-planning outcomes of pregnancy or contraception uptake/use were assessed. Studies that did not compare the effectiveness of an intervention with that of a control were excluded. Information on study design, funding source, location, duration, population, inclusion and exclusion criteria, intervention, comparison group, and outcomes was extracted using a standard abstract form [6]. Owing to heterogeneity across study populations and evaluated interventions, it was not possible to conduct a meta-analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Study selection

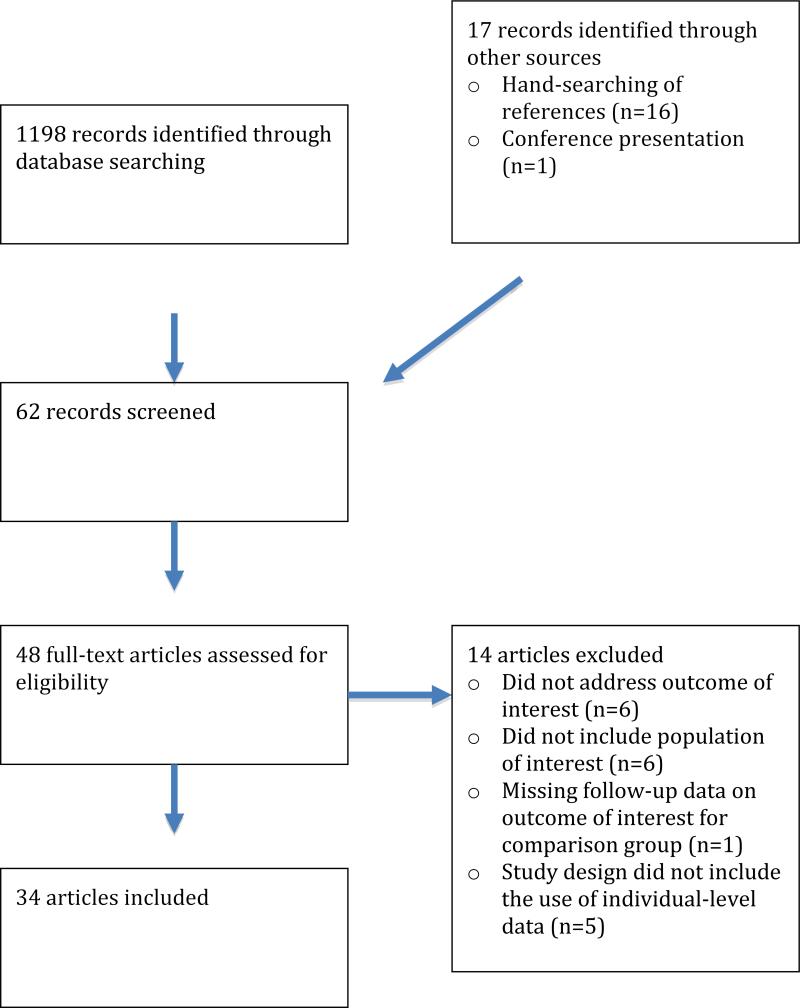

The search yielded a total of 1198 citations, whose titles and abstracts were reviewed. In addition, 16 records were identified via hand-searching, and 1 was found through a conference presentation. Thirty-four articles met the review inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Supplementary Material S2 summarizes all studies included in the present review. The articles were organized by type of intervention.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study selection process.

3.2. Prenatal care

A good-quality retrospective cohort study [7] using a birth records database of 113 662 women examined the association between the timing and adequacy of prenatal care and the subsequent birth interval (less than 18 months versus 60 months or more). The study showed increased odds of having a short birth interval (less than 18 months) for women who initiated care at 4–6 months (odds ratio [OR] 1.19; P<0.001) or 7–9 months (OR 1.26; P<0.001) of pregnancy, and for those who had no prenatal care (OR 1.61; P<0.001), compared with those who initiated care at 1–3 months of pregnancy. No differences between the groups were seen for the outcome of a birth interval of 60 months or more. The study also evaluated the adequacy of prenatal care, taking into consideration both the month of prenatal care initiation and the disparity between the actual and recommended numbers of prenatal care visits. The odds of having a birth interval of less than 18 months were increased for women who received inadequate prenatal care (OR 1.23; P<0.001) or no prenatal care (OR 1.53; P<0.01), compared with those who received adequate care. The content of family-planning counseling during the prenatal care visits was not described.

3.3. Home visitation

Twelve randomized controlled trials [8–19], ranging from fair to good quality, investigated the impact of home visitation during the postpartum period on repeat birth, repeat pregnancy, or contraceptive use. Ten were conducted in the USA [8,9,11–18], whereas the other studies came from Syria [10] and Australia [19]. Seven of these studies [8,9,11,15,17–19] focused on women aged 19 or younger.

Four fair-quality studies [9,11,13,14] reported that home visitation improved birth spacing outcomes. Barnet et al. [9] used a computer-assisted motivational intervention (CAMI) for teenagers with biweekly to monthly home visits for up to 24 months postpartum versus CAMI with a single home visit, compared with usual care. The second study [11] involved an intervention that included 19 home-based lessons during the 2 years postpartum. Both of these trials showed a decrease in “rapid repeat birth” (repeat birth within 2 years) (P<0.05) (Supplementary Material S2). Two trials [13,14] among a high-risk African American nulliparous population compared 4 arms: prenatal care with no home visitation, prenatal care and referral to services for the children, prenatal care plus intensive prenatal home visits and 1 postpartum home visit, and prenatal care with intensive home visits prepartum and postpartum. In these trials, conducted in the same study population, the odds of subsequent pregnancies and live births in the intervention groups were decreased at a 2-year follow-up assessment (OR of a subsequent pregnancy: 0.6, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.4–0.9, P<0.001; OR of a subsequent live birth: 0.6, 95% CI 0.4–0.9, P<0.01) [13] and at a 4.5 year follow-up assessment (difference in the mean number of new pregnancies: 0.19, 95% CI 0.01–0.35, P<0.05; difference in the mean number of new live births: 0.11, 95% CI, –0.02 to 0.25, P>0.05) [14] (Supplementary Material S2).

An Australian trial [19] of good quality evaluated the efficacy of home visits at 1 week, 2 weeks, 1 month, 2 months, and 4 months in a teenage population, and showed an increase in contraceptive use at 6 months (adjusted relative risk of contraceptive use at 6 months: 1.35, 95% CI 1.09–1.68; P=0.007).

3.4. Mother–infant care integration

Six studies [20–25] evaluated pregnancy or contraceptive use outcomes when mother and infant care is integrated to include family-planning counseling. Interventions varied considerably in character and counseling intensity, and were not described consistently. Four studies conducted interventions at infant vaccination visits: 2 studies [20,23] involved family-planning counseling and referral to a family-planning clinic, 1 study [24] provided education on breastfeeding and family planning, and another study [25] included multidisciplinary care with a social worker, pediatrician, and nurse practitioner. Other studies tested multiple additional visits outside of routine infant care.

Of the 3 mother–infant care integration studies that reported positive results [23–25], 1 study [25] was of fair quality and 2 studies [23,24] were of poor quality. In a randomized controlled trial of postpartum adolescents [25], the intervention group that received an integrated multidisciplinary mother–infant care program had a significantly decreased repeat pregnancy rate at 18 months compared with a control group that received routine well-infant care (12% versus 28%; P=0.003). Three studies [20–22] did not find an association between mother–infant care integration and improved family-planning outcomes; these studies were of poor to fair quality (Supplementary Material S2). The largest study on this topic did not find an impact on contraceptive uptake but the intervention may not have been consistently implemented [20].

3.5. Educational interventions

Educational interventions included 1 or more counseling sessions about contraception and/or breastfeeding during the prepartum period [26–31], on the postpartum ward [32–35], or during the later postpartum period in the clinic [30,32]. The studies varied in the duration of follow-up, which ranged from 6 weeks to 12 months. Four [30–32,34] of the 5 studies with positive results involved family-planning education during the postpartum hospital stay.

Of the 10 studies [26–35] evaluating educational interventions, 5 studies [27,30–32,34] of poor to good quality showed an improvement in contraceptive use, and 2 showed a decrease in repeat pregnancy within 12 months [30] or 9 months [27]. In a randomized controlled trial conducted in Pakistan [34], the intervention group received a 20-minute counseling session along with a 1-page leaflet after delivery. This trial found improved rates of contraceptive use at 8–12 weeks in the intervention group compared with the control group (56.9% versus 6.31%; P<0.01). In a cohort study [30] that focused on postpartum contraception use and lactational amenorrhea education in Brazil, with participants recruited before and after the intervention, there were significantly fewer pregnancies in the intervention group (7.4% versus 14.3%; P<0.001) at 12 months postpartum. In addition, fewer women in the intervention group were not using any form of contraception at 12 months postpartum compared with the control group (7.4% versus 17.7%; P<0.001). Another randomized controlled trial [32] conducted in Nepal showed that infant health education including breastfeeding education immediately after birth increased contraceptive use at 6 months (OR 1.62; P=0.03). A prospective cohort study [27] of an educational campaign intervention in India reported fewer pregnancies (10.5% versus 16.4%; P≤0.01) and increased contraceptive use (OR 3.51; P≤0.01) in the intervention group at 9 months postpartum. Finally, a randomized controlled trial [31] among women in Nigeria with 4 or more prior deliveries studied the effect of a prepartum educational intervention that included counseling on family planning and the risks of high parity. Women in the intervention group were more likely to choose sterilization (13.0%) compared with those in the control group (3.4%; P<0.001).

Other studies of prenatal contraception counseling [26,28,29] and post-delivery counseling [33,35] showed no effect on contraceptive use [26,28,29,33,35] or repeat pregnancy [28].

3.6. Multidisciplinary approach

Multidisciplinary approaches comprised a variety of interventions in which a team administered health and educational interventions. In a cohort study [36] that evaluated the effect of biweekly educational sessions provided to teenage mothers by a collaborative team (including obstetricians/gynecologists, pediatricians, social workers, and health educators), an increased rate of contraceptive use (85% versus 22%; P<0.001) and a decreased rate of repeat term pregnancy (3% versus 36%; P<0.001) were noted in the intervention group. A fair-quality randomized controlled trial [37] from the USA showed a decreased time to repeat pregnancy in a stratified analysis of postpartum girls aged 15–17 years who participated in an intensive multidisciplinary intervention involving biweekly telephone counseling, a reproductive health curriculum, and dinner group sessions (hazard ratio 0.987, 95% CI 0.977–0.997; P=0.013). However, no significant results were noted in the full studied sample in this study.

A US ambidirectional cohort study [36] (in which data were retrospectively collected from medical records until 1985, and prospectively collected thereafter) showed an increased rate of contraceptive use (85% versus 22%; P<0.001) and a decreased rate of repeat pregnancy by age 20 years (3% versus 36%; P<0.001) in the intervention group compared with the control group. A Kenyan survey [38] evaluated a comprehensive “postnatal care package” that included maternal and child health assessments and services at birth as well as 2 and 6 weeks after delivery. In this study, contraceptive use improved from 35% during the pre-intervention period to 63% after the intervention, although no statistical analysis was reported.

3.7. Cash transfer and microfinance

Two studies [39,40] were identified that evaluated whether transferring cash or providing microfinance to postpartum women has an effect on family-planning outcomes. A cluster randomized controlled trial [39] of 5001 women used time series data to evaluate a program in Mexico that provided cash transfers to designated female household heads in poor communities conditional to their participation in health promotion activities and/or children's school attendance. Family-planning programs were also instituted as a part of this program. In this study, the hazard ratio of giving birth subsequent to an index birth was 1.04 (P>0.05). The use of modern contraceptive methods improved during the initial 2 years of the study (difference in the log odds of contraceptive use: 0.16; P≤0.05), but not during the following 3 years (difference in the log odds of contraceptive use: 0.16; P>0.05).

A time series survey study [40] evaluated an intervention in Bangladesh that integrated the delivery of family-planning services, child immunization, and microcredit (small loans). In this study, an analysis of post-intervention data showed improvements in current contraceptive use in the experimental group (baseline 28.0%, experimental group 53.0%, control group 38.4%). However, no statistical analysis of the group differences was presented.

4. Discussion

Programmatic interventions aiming to strengthen postpartum family-planning service delivery have the potential to improve maternal and child health. A variety of interventions have been implemented to improve birth spacing and contraceptive use during the postpartum period. In general, evaluating the overall efficacy of these programs is challenging, given the great variety in program types. However, we attempted to synthesize the results from studies addressing program interventions to inform future directions in programmatic development, funding priorities, and future research.

One good-quality study [7] was identified that evaluated the relationship between early initiation of prenatal care and the subsequent birth interval. Strengths of this study included its large sample size and the strong statistical methodology. However, it was conducted in only 1 state in the USA, which limits its generalizability to other settings. It is well-recognized that prenatal care is essential for maternal and child health. Outreach efforts should be made to include as many women as possible in prenatal care.

The present review included studies in high-income countries that showed an association between home visitation during the postpartum period and improved birth spacing outcomes. All studies in this category provided Level I evidence (randomized controlled trials). Strong statistical methodology was used, and each of the studies had a moderate-to-large sample size (more than 200 participants). All trials examining the impact of home visitation included women of low socioeconomic status in their sampling. Nevertheless, the generalizability of these studies is limited because 11 of the 12 trials were conducted in high-income countries, and 6 of the 12 trials [8,9,11,13,14,16] included predominantly African American women. In addition, there is potential selection bias because many of the publications did not provide information on allocation concealment. In 2 studies [15,19], the primary outcome was not a family-planning outcome. Home visitation may be useful in low-income countries, particularly if the skills of ancillary health workers are used. The feasibility and effectiveness of home visits to improve postpartum family-planning outcomes in low-income countries should be studied further.

Mother–infant care integration programs take advantage of opportunities for contraceptive provision that may otherwise be missed. The limitations of the identified studies on mother–infant integration programs included unclear time and method of outcome measurement [24,25] and significant loss to follow-up limiting the ability to measure outcomes [21,22]. In addition, the study by Huntington et al. [23] was a combination of a time series survey and a retrospective review of service statistics, both of which have a high susceptibility to confounding and bias. Research on mother–infant care integration is sparse and varied in quality, although some research [23–25] has shown that these interventions improve contraceptive use and pregnancy spacing. The largest study on this topic [20] did not show improvement in contraceptive uptake but that may be because of incomplete implementation of the intervention. In addition, the effect of mother–infant care integration on child health is unclear.

Postpartum and prepartum educational interventions improved postpartum family planning in many of the included studies. In general, the educational interventions were not fully described in these publications. Other limitations with this group of studies include: susceptibility to confounding [30], improper randomization technique [26], no description of the randomization method [29,34], no description of allocation concealment [29,31,34], and lack of specificity of the outcome measure [32,34].

Multidisciplinary interventions involving postpartum education by health professionals have been studied in high-income countries only. The included articles were of poor to fair quality, and specifics and curricula for the interventions were often not provided. The study by Rabin et al. [36] did not compare baseline characteristics in the studied groups, did not control for any potential confounders, and did not describe the timing of the outcome measure. Thus, the potential for confounding and for selection and information bias was high. The study by Katz et al. [37] described a very intensive intervention that may not be generalizable to low-resource settings. Finally, the study by Warren et al. [38] included no power calculation, had a small sample size, and was susceptible to selection bias with its time series survey design. It is unclear whether the studied types of intervention (involving intensive interventions and technology) are generalizable to low-resource settings. It is difficult to make conclusions based on these studies, given their significant heterogeneity.

Cash transfer and microfinance interventions in postpartum family planning are an interesting area for further research. The study on cash transfer by Feldman et al. [39] provided Level I evidence of fair quality, and controlled for confounders and clustering. Limitations of this study included the data collection in time series surveys and the merging of different survey data. The study by Amin et al. [40], which evaluated microfinance, included no power calculation or statistical analysis, and thus the effect of the intervention could not be fully assessed.

The present review included emerging relevant research from 1 unpublished study. The results from a randomized controlled trial of an educational intervention were abstracted from an abstract [35] of a conference presentation.

When preparing the present systematic review of program interventions, we found that the length of an academic journal article is not generally amenable to the detailed descriptions needed to adequately describe these programs. In addition, many of the identified studies were of poor to fair quality. It is difficult to combine program evaluation and peer-reviewed research. The findings of the present review support the need to allocate additional resources to the evaluation of high-quality programs, using more rigorous research techniques. In addition, with the expansion of research journals to the Internet, web-based appendices may be used to aid in the description, and possibly the replication and scaling-up, of high-quality programs.

The benefit of improving high-quality family-planning services for women during the first year postpartum is clear. In the present review, we have systematically assessed the effectiveness of different approaches to deliver these services. In order to gain a greater understanding of the potential for postpartum family-planning interventions to improve maternal and child health outcomes, attention is needed toward conducting well-designed studies that evaluate a variety of the most promising interventions.

Supplementary Material

Synopsis.

Prenatal care, home visitation programs, and educational interventions seem to improve postpartum family-planning outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The present review was supported by WHO, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the US Agency for International Development, and the Family Planning Fellowship. S.M. is supported by the Women's Reproductive Health Research program (grant K12 HD00 1259).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Singh S, Darroch JE. Adding It Up: Costs and Benefits of Contraceptive Services. Estimates for 2012. http://www.unfpa.org/webdav/site/global/shared/documents/publications/2012/AIU%20Paper%20-%20Estimates%20for%202012%20final.pdf. Published 2012.

- 2.Borda M, Winfrey W. Postpartum Fertility and Contraception: An Analysis of Findings from 17 Countries. http://www.k4health.org/sites/default/files/Winfrey_Borda_17countryanalysis.pdf. Published March 2010.

- 3.World Health Organization . Report of a WHO Technical Consultation on Birth Spacing. Geneva, Switzerland: Jun, 2005. pp. 13–15. http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/birth_spacing.pdf. Published 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harris RP, Helfand M, Woolf SH, Lohr KN, Mulrow CD, Teutsch SM, et al. Current methods of the US Preventive Services Task Force: a review of the process. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20(3 Suppl):21–35. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00261-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mohllajee AP, Curtis KM, Flanagan RG, Rinehart W, Gaffield ML, Peterson HB. Keeping up with evidence a new system for WHO's evidence-based family planning guidance. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28(5):483–90. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teitler JO, Das D, Kruse L, Reichman NE. Prenatal care and subsequent birth intervals. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2012;44(1):13–21. doi: 10.1363/4401312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barnet B, Liu J, DeVoe M, Alperovitz-Bichell K, Duggan AK. Home visiting for adolescent mothers: effects on parenting, maternal life course, and primary care linkage. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5(3):224–32. doi: 10.1370/afm.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barnet B, Liu J, DeVoe M, Duggan AK, Gold MA, Pecukonis E. Motivational intervention to reduce rapid subsequent births to adolescent mothers: a community-based randomized trial. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(5):436–45. doi: 10.1370/afm.1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bashour HN, Kharouf MH, Abdulsalam AA, El Asmar K, Tabbaa MA, Cheikha SA. Effect of postnatal home visits on maternal/infant outcomes in Syria: a randomized controlled trial. Public Health Nurs. 2008;25(2):115–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2008.00688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Black MM, Bentley ME, Papas MA, Oberlander S, Teti LO, McNary S, et al. Delaying second births among adolescent mothers: a randomized, controlled trial of a home-based mentoring program. Pediatrics. 2006;118(4):e1087–99. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El-Kamary SS, Higman SM, Fuddy L, McFarlane E, Sia C, Duggan AK. Hawaii's healthy start home visiting program: determinants and impact of rapid repeat birth. Pediatrics. 2004;114(3):e317–26. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kitzman H, Olds DL, Henderson CR, Jr, Hanks C, Cole R, Tatelbaum R, et al. Effect of prenatal and infancy home visitation by nurses on pregnancy outcomes, childhood injuries, and repeated childbearing. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1997;278(8):644–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kitzman H, Olds DL, Sidora K, Henderson CR, Jr, Hanks C, Cole R, et al. Enduring effects of nurse home visitation on maternal life course: a 3-year follow-up of a randomized trial. JAMA. 2000;283(15):1983–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koniak-Griffin D, Verzemnieks IL, Anderson NL, Brecht ML, Lesser J, Kim S, et al. Nurse visitation for adolescent mothers: two-year infant health and maternal outcomes. Nurs Res. 2003;52(2):127–36. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200303000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Norr KF, Crittenden KS, Lehrer EL, Reyes O, Boyd CB, Nacion KW, et al. Maternal and infant outcomes at one year for a nurse-health advocate home visiting program serving African Americans and Mexican Americans. Public Health Nurs. 2003;20(3):190–203. doi: 10.1046/j.0737-1209.2003.20306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olds DL, Eckenrode J, Henderson CR, Jr, Kitzman H, Powers J, Cole R, et al. Long-term effects of home visitation on maternal life course and child abuse and neglect. Fifteen-year follow-up of a randomized trial. JAMA. 1997;278(8):637–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olds DL, Henderson CR, Jr, Tatelbaum R, Chamberlin R. Improving the life-course development of socially disadvantaged mothers: a randomized trial of nurse home visitation. Am J Public Health. 1988;78(11):1436–45. doi: 10.2105/ajph.78.11.1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quinlivan JA, Box H, Evans SF. Postnatal home visits in teenage mothers: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361(9361):893–900. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12770-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vance G, Janowitz B, Chen M, Boyer B, Kasonde P, Asare G, et al. Integrating family planning messages into immunization services: a cluster-randomized trial in Ghana and Zambia. Health Policy Plan. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czt022. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alvarado R, Zepeda A, Rivero S, Rico N, López S, Díaz S. Integrated maternal and infant health care in the postpartum period in a poor neighborhood in Santiago, Chile. Stud Fam Plann. 1999;30(2):133–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.1999.00133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elster AB, Lamb ME, Tavaré J, Ralston CW. The medical and psychosocial impact of comprehensive care on adolescent pregnancy and parenthood. JAMA. 1987;258(9):1187–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huntington D, Aplogan A. The integration of family planning and childhood immunization services in Togo. Stud Fam Plann. 1994;25(3):176–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jakobsen MS, Sodemann M, Mølbak K, Alvarenga I, Aaby P. Promoting breastfeeding through health education at the time of immunizations: a randomized trial from Guinea Bissau. Acta Paediatr. 1999;88(7):741–7. doi: 10.1080/08035259950169026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Sullivan AL, Jacobsen BS. A randomized trial of a health care program for first-time adolescent mothers and their infants. Nurs Res. 1992;41(4):210–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akman M, Tüzün S, Uzuner A, Başgul A, Kavak Z. The influence of prenatal counselling on postpartum contraceptive choice. J Int Med Res. 2010;38(4):1243–9. doi: 10.1177/147323001003800405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sebastian MP, Khan ME, Kumari K, Idnani R. Increasing postpartum contraception in rural India: evaluation of a community-based behavior change communication intervention. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2012;38(2):68–77. doi: 10.1363/3806812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith KB, van der Spuy ZM, Cheng L, Elton R, Glasier AF. Is postpartum contraceptive advice given antenatally of value? Contraception. 2002;65(3):237–43. doi: 10.1016/s0010-7824(01)00308-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soliman MH. Impact of antenatal counselling on couples’ knowledge and practice of contraception in Mansoura, Egypt. East Mediterr Health J. 1999;5(5):1002–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hardy E, Santos LC, Osis MJ, Carvalho G, Cecatti JG, Faúndes A. Contraceptive use and pregnancy before and after introducing lactational amenorrhea (LAM) in a postpartum program. Adv Contracept. 1998;14(1):59–68. doi: 10.1023/a:1006527711625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Omu AE, Weir SS, Janowitz B, Covington D, Lamptey PR, Burton NN. The effect of counseling on sterilization acceptance by high-parity women in Nigeria. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 1989;15(2):6. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bolam A, Manandhar DS, Shrestha P, Ellis M, Costello AM. The effects of postnatal health education for mothers on infant care and family planning practices in Nepal: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 1998;316(7134):805–11. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7134.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gilliam M, Knight S, McCarthy M., Jr Success with oral contraceptives: a pilot study. Contraception. 2004;69(5):413–8. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2003.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saeed GA, Fakhar S, Rahim F, Tabassum S. Change in trend of contraceptive uptake--effect of educational leaflets and counseling. Contraception. 2008;77(5):377–81. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang JH, Dominik R, Zerden M, Brody S, Stuart G. Abstract: Effect of an educational script on postpartum contraceptive uptake: a randomized controlled trial.. Presented at the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 61st Annual Clinical Meeting; May 7, 2013; 2013. [December 2]. http://www.acog.org/About_ACOG/News_Room/~/media/Departments/Annual%20Clinical%20Meeting/20130507Papers.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rabin JM, Seltzer V, Pollack S. The long term benefits of a comprehensive teenage pregnancy program. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1991;30(5):305–9. doi: 10.1177/000992289103000508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Katz KS, Rodan M, Milligan R, Tan S, Courtney L, Gantz M, et al. Efficacy of a randomized cell phone-based counseling intervention in postponing subsequent pregnancy among teen mothers. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15(Suppl 1):S42–53. doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0860-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Warren C, Mwangi A, Oweya E, Kamunya R, Koskei N. Safeguarding maternal and newborn health: improving the quality of postnatal care in Kenya. Int J Qual Health Care. 2010;22(1):24–30. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzp050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feldman BS, Zaslavsky AM, Ezzati M, Peterson KE, Mitchell M. Contraceptive use, birth spacing, and autonomy: an analysis of the Oportunidades program in rural Mexico. Stud Fam Plann. 2009;40(1):51–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2009.00186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Amin R, St Pierre M, Ahmed A, Haq R. Integration of an essential services package (ESP) in child and reproductive health and family planning with a micro-credit program for poor women: experience from a pilot project in rural Bangladesh. World Development. 2001;29(9):11. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.