Abstract

This study examined the extent to which infant and parent response trajectories during the Still-Face-Paradigm (SFP) in early infancy predicted later infant-mother and infant-father attachment. Families (n = 135) participated in the SFP when infants were 3, 5, and 7 months and the Strange Situation when infants were 12 (mothers) and 14 months (fathers). Multilevel models showed that parent sensitivity assessed during the SFP was related to infants’ affective and behavioral response trajectories during the SFP, and that sensitivity and infant response trajectories predicted attachment. Results from the present study support the notion that parent and infant responses in the SFP with mothers and fathers during Bowlby’s Attachment in the Making phase provide insight into the developing parent-child attachment relationship.

Keywords: infancy, attachment, affect, regulation, fathers, parent sensitivity

Attachment theory posits that infants develop an internal working model of the infant-caregiver relationship through repeated parent-child interactions during the first year of life (Bowlby, 1973). According to Bowlby, internal working models are representations that help infants anticipate, interpret, and guide interactions with attachment figures. To the extent that a caregiver is consistently sensitive and emotionally responsive to infants’ needs, infants should develop a positive internal working model that the caregiver is a reliable source for care and comfort, i.e., secure attachment. If caregivers are rejecting, intrusive, or inconsistent in their responsiveness, or withdrawn, inattentive, and unresponsive, however, infants may develop a negative working model that the caregiver is not a dependable source of comfort, i.e., insecure attachment (Bretherton & Munholland, 2008). Indeed, one of the most robust predictors of infant-parent attachment security is parental sensitivity (see de Wolff & van IJzendoorn, 1997 and Lucassen et al., 2011 for meta-analyses for infant-mother and infant-father attachment), which refers to a caregiver’s ability to perceive and interpret an infant’s emotional cues and to respond promptly and appropriately (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978).

The development of attachment requires infants to have reached a certain level of cognitive maturity and to have experienced enough of a history with the attachment figure to be able to form an attachment. According to Bowlby (1969), infants reach the phase of Clear Cut Attachment between approximately 8 and 12 months of age. By 12 months, infants’ reactions to caregivers can be reliably assessed by trained observers, typically using the Strange Situation Procedure (Ainsworth et al., 1978). Based on their behaviors during this procedure that activates the attachment system, infants can be classified as secure, insecure (avoidant or ambivalent), or disorganized. Prior to this point, infants are in the phase of Attachment in the Making from approximately 2 to 8 months of age (Bowlby, 1969). Although we cannot directly assess attachment in this phase, we can observe infants’ emotional and behavioral responses during infant-parent interactions. To the extent that infant-parent interactions tap into early developing attachment systems, it is possible that we can observe signs of developing working models. We would expect, for example, that infants whose parents are more sensitive during play would show more positive affect toward parents in this context. Indeed, a recent study of infants at 5- months of age showed concurrent positive associations between maternal sensitivity and infants’ affective, behavioral, and physiological reactions with mothers (Conradt & Ablow, 2010).

Although several studies have examined associations between infants’ affective and behavioral responses during early infant-mother interactions and later attachment, none has included the following elements simultaneously in one study: Examine infant and parent behaviors over multiple time points to study longitudinal trajectories; include fathers as well as mothers; examine infant responses across contexts in which parents are emotionally available versus unavailable; and include all classifications of attachment (secure, avoidant, ambivalent, disorganized). The present study included each of the elements to examine links between affective and behavioral responses and attachment in a comprehensive manner. More specifically, infants, mothers, and fathers were studied when infants were 3-, 5-, and 7- months of age—during the phase of Attachment in the Making. We observed infant response trajectories during the Still-Face Paradigm (SFP; Tronick, Als, Adamson, Wise, & Brazelton, 1978) which involves several different episodes in which the parent is emotionally responsive or not and the degree to which trajectories related to parent sensitivity. In addition, we examined the degree to which patterns of trajectories during the SFP reflected secure, avoidant, ambivalent, or disorganized attachment classifications at one year of age.

Infant Responses During the Still-Face Paradigm

The SFP (Tronick et al., 1978) was introduced as a laboratory procedure designed to examine infants’ responses before, during, and after a perturbation in parent-child interaction and to explore infants’ understanding of social cues and interactions. Typically in this procedure, the infant and parent engage in a face-to-face interaction episode (play), followed by a still-face episode in which the parent ceases interaction and maintains a neutral facial expression; the SFP ends with a reunion episode in which normal face-to-face interaction resumes.

Infants often show marked changes in behaviors during the SFP as they proceed from one episode to the next. Typically, there is increased negative affect, decreased smiling, and less visual orientation toward the parent during the still-face episode compared to the play episode, and a return to initial levels of responses as infants recover during the reunion episode (Adamson & Frick, 2003). Behavioral responses during the SFP such as turning visual attention away from the parent or self-comforting (e.g., thumb sucking) may reflect infants’ attempts to regulate their arousal, especially when caregivers are unavailable during the still-face episode (Manian & Bornstein, 2009; Stifter & Braungart, 1995). In addition, such behaviors may serve as signals to caregivers about infants’ experiences (Toda & Fogel, 1993) during the play or reunion episodes. For example, when infants orient their attention away from parents during play or reunion, they may be signaling overstimulation or disinterest to their parents, whereas those showing more attention towards parents may be signaling the desire to maintain the interaction.

In many ways, the SFP contains similar elements as those involved in the Strange Situation (Ainsworth et al., 1978), which is used to assess attachment security during the phase of Clear Cut Attachments. Both procedures involve separation and reunion episodes, though in the case of the SFP, the separation and reunion episodes are socio-emotional in nature, whereas in the Strange Situation, the episodes are both socio-emotional and physical (Cohn, 2003). Thus, the SFP may be a particularly salient procedure in which to examine developing internal working models during the phase of Attachment in the Making given that we can observe how infants react when parents disengage their attention from the infant and then re-establish interaction.

Parent Sensitivity and Infant SFP Responses

Similar to how parent sensitivity predicts attachment assessed during the Strange Situation, sensitivity predicts individual differences in infants’ responses during the SFP. Meta-analytic results involving eight studies (Mesman, van IJzendoorn, & Bakermans-Kranenburg, 2009) found that more positive maternal behavior (e.g., positive affect, sensitivity) was significantly related to infant positive affect (d = .45, p < .01) but not negative affect (d = .15, p = .49) during the SFP. In addition, more sensitive parenting has been linked with longer gazes toward mothers during the still-face episode (Carter, Mayes, & Pajer, 1990), perhaps indicating that infants make more attempts to re-engage if their mothers are normally responsive. Increased maternal sensitivity outside of the SFP during a home visit is also predictive of decreased negative affect two weeks later during the still-face episode (Tarabulsy et al., 2003), suggesting that affective responses during the SFP may reflect the quality of infant-mother interactions more broadly.

Several studies have also examined the reunion episode of the SFP in which parents return to interacting with their infants. More specifically, infants whose mothers were more sensitive showed more positive affect (Erickson & Lowe, 2008), less gaze aversion and fewer displays of avoidant and resistant behavior toward mothers (Kogan & Carter, 1996), and greater regulation of negative affect (Haley & Stansbury, 2003) during reunion. These findings suggest that sensitivity is associated with more optimal affect recovery after the stressor (i.e., nonresponsive mother) has ended. Moreover, parents’ behaviors during reunion may differ somewhat from those during the initial play episode, particularly if they need to help infants recover from the still-face episode. Parent sensitivity during reunion may more strongly impact the bases of infants’ internal working models. Indeed, sensitivity during distress tasks was more highly related to parent-child attachment than sensitivity during play tasks (Leerkes, 2011). Previous studies, however, have not systematically looked for differential predictions by episode when examining links between parent sensitivity and infant responses. Thus, the present study examined parent sensitivity across both play and reunion episodes and infant behaviors across all three episodes of the SFP.

It should also be noted that studies to date have not examined affective or behavioral responses during the SFP in relation to sensitivity in a longitudinal manner. Studying longitudinal trajectories enables one to examine initial levels and changes in behaviors over time. For example, a study on the development of social fear found that lower levels of maternal sensitivity during a free-play situation did not predict initial levels of fear during a stranger-approach situation but predicted steeper increases in infant fear from 4 to 16 months (Braungart-Rieker, Hill-Soderlund, & Karrass, 2010). Thus, individual differences in patterns of developmental trajectories may tell us about emerging and changing dynamics in the infant-parent dyad that we would not otherwise detect during a single point in time.

Moreover, research with fathers is sparse. As family structures and roles have become more diverse in recent decades, interest has grown dramatically in understanding the impact of fathers on children’s healthy growth and development (Cabrera, Tamis-LeMonda, Bradley, Hofferth, & Lamb, 2000). To our knowledge, however, only two studies (of different samples) have examined both infant and father behaviors during the SFP (Braungart-Rieker, Garwood, Powers, & Notaro, 1998; Forbes, Cohn, Allen, & Lewinsohn, 2004). Paternal behaviors were not significantly related to infant affect when infants were 3 (Forbes et al., 2004) or 4 months of age (Braungart-Rieker et al., 1998). By 6 months of age, however, infants whose fathers were more positive in their affect showed more positive and less negative affect during the still-face (Forbes et al., 2004). It is possible that coherent patterns of associations between fathers’ and infants’ behaviors take more time to develop given that fathers typically spend less time interacting with young infants than mothers (Pleck & Masciadrelli, 2004) and that infants may require additional time and experience in developing expectations of fathers’ behaviors. Neither of these studies, however, examined infants’ responses during the reunion episode, when parental behaviors may be more essential to the developing attachment system.

Studying infants with both mothers and fathers not only enables us to compare whether processes are similar across infant-mother and infant-father dyads, it allows us to examine if behaviors and relationships with one parent relate to those with the other parent. Although several major perspectives such as family systems (Cox & Paley, 2003) and ecological systems theories (Bronfenbrenner, 2009) argue for the importance of studying children across multiple contexts within and even beyond the family, this is rarely done. Thus, because infant-mother and infant-father dyads do not operate in isolation of each other, we explored the degree to which sensitivity of one parent is related to infants’ behavior during the SFP--not only with that same parent but with the other parent as well. By doing so, we can learn the degree to which infant responses are unique to a particular caregiver or transcend across relationships.

Early Infant Affective and Behavioral Responses and Later Attachment

A recent meta-analysis (Mesman et al., 2009) included four published studies and one unpublished study that examined the degree to which early affective and/or behavioral responses with mothers predicted later infant-mother attachment security, and each of these studies relied on the SFP to capture infant responses. Results indicated that infants later identified as secure showed more positive affect and less negative affect during the SFP (ds = .23 and .24, respectively). However, a number of gaps in knowledge remain.

First, studies either examined infant behaviors during the still-face episode only (Braungart-Rieker et al., 2001; Cohn, Campbell, & Ross, 1991; Tronick, Ricks, & Cohn, 1982), or examined responses collapsed across all three episodes (Fuertes, Santos, Beeghly, & Tronick, 2006). Thus, we are unable to learn whether infant responses during contexts in which parents are emotionally unavailable versus available differentially related to attachment. This may be important given that responses during the Strange Situation’s reunion episode are more revealing about attachment security than those during the separation episodes (Ainsworth et al., 1978).

Second, all previous studies either examined SFP responses in only one age group (Braungart-Rieker et al., 2001; Fuertes et al., 2006; Kiser et al., 1986) or included several age groups but examined groups separately (Cohn et al., 1991; Tronick, Ricks, & Cohn, 1982). When multiple age groups were examined, Cohn et al. (1991) found that infants later classified as secure had shown more positive affect during the SFP at 6 months but not at 2 or 4 months. Tronick et al. (1982) also found that attachment security was related to more positive affective patterns at 6 months; however, relations with affective patterns at 3 or 9 months were not detected. Thus, when considering the results from both of these studies, it is somewhat difficult to draw conclusions about how developmental processes might relate to connections between affect and attachment. The present study’s design enables us to examine trajectories of infant affective and behavioral responses over time. Given that attachment takes time to develop and that attachment security likely reflects the history of parent-child interactions during the phase of Attachment in the Making, it is important that we examine how infant affective and behavioral responses and parental sensitivity unfold over this period of time to gain better insights about the emerging attachment relationship.

Third, only one study has included fathers but did not find significant results between infant SFP responses at 4 months and infant-father attachment at 13 months (Braungart-Rieker et al., 2001). It may be that internal working models take longer to develop with fathers than mothers, if we assume that mothers typically spend more time with young infants (Pleck & Masciadrelli, 2004). Studying infants with fathers across a longer time period might allow more time for working models to develop. Thus, we examined the degree to which attachment security at one year of age related to infant responses with each parent across the 3 to 7 month age period.

Finally, no studies have examined how infant SFP responses relate to each of the classifications of attachment. Rather, they have examined the secure vs. insecure distinction (Tronick et al., 1982) or the traditional classifications of secure, avoidant, and ambivalent (Braungart-Rieker et al., 2001; Cohn et al., 1991; Fuertes et al., 2006; Kiser et al., 1986). In addition, results have not always been consistent when examining the insecure sub-classifications of avoidant and ambivalent infants. For example, Cohn et al. (1991) found that future avoidant but not ambivalent infants showed less positive affect during the still-face than future secure infants, but did not detect differences in negative affect across groups. In other studies, infants later classified as ambivalent but not avoidant showed more distress during the still-face episode than those later classified as secure (Braungart-Rieker et al., 2001; Kiser et al. 1986). Differences in the age of infant or how affect was coded could account for differential results across studies. Moreover, no studies have examined infants’ responses during the SFP and how that might relate to the disorganized classification.

The Present Study

In summary, three main goals guided the present study: (1) As a first step, we examined infant and parent SFP response trajectories descriptively as a function of age (3, 5, and 7 months), episode (still-face and reunion), and parent (mother and father). Patterns of behaviors and associations that vary by age, episode, or parent can inform us in different ways. Age-related trajectories tell us about emerging and changing dynamics in infant-parent dyads. Differences by episode provide us with insights about context; i.e., we observe infant responses when parents are emotionally disengaged and subsequently reengaged. Finally, studying the infant with both mothers and fathers informs us about whether responses are similar or different across parent dyads. (2) We examined the extent to which parent sensitivity is related to infant affective (positive and negative) and behavioral (visual orientation toward parents and self-comforting) response trajectories during the SFP. (3) We examined the degree to which infant and parent SFP response trajectories are related to attachment classifications (secure, avoidant, ambivalent, disorganized) at one year of age. With a goal to remove some of the effects of infant influence on parent sensitivity, infant affect, and attachment linkages, we control for infant negative temperament in analyses involving the latter two aims. We also control for infants’ initial responses during play so that we can better understand infants’ reactions to the still-face and reunion episodes.

Method

Participants

This study was part of a larger longitudinal study of 135 parents and their infants (64 boys; 71 girls) who visited the laboratory when infants were 3, 5, 7, 12, 14, and 20 months (+/− 14 days). Previous work stemming from these data include three publications examining attachment but not infant SFP responses (Lickenbrock, Braungart-Rieker, Ekas, Zentall, Oshio, & Planalp, in press; Planalp & Braungart-Rieker, 2013; and Zentall, Braungart-Rieker, Ekas, & Lickenbrock, 2012), one examining second-by-second associations between affective and behavioral responses within the SFP but not attachment (Ekas, Lickenbrock, & Braungart-Rieker, 2013), and two looking neither at attachment nor infant SFP responses (Ekas, Braungart-Rieker, Lickenbrock, Zentall, & Maxwell, 2011; Planalp, Braungart-Rieker, Lickenbrock, & Zentall, S. (in press). For the purposes of this study, data from all but the last visit were examined. Participants in this study were recruited through a variety of mechanisms: a local child birth educator announced the study to her classes, flyers were sent home to new mothers from a local hospital, business cards were distributed to various local community locations, and an informational booth was set up at several local community events. Mothers were on average 29.3 years (range = 17–44), and fathers were on average 30.7 years (range = 18–44). Parents were predominantly Caucasian (90.3% of mothers and 87.4% of fathers) and middle-class: 14.8% of the families had annual incomes below $29,999, 65.2% earned $30,000–$74,999, 17.60% made $75,000 or more annually, and 3.0% chose not to provide information on their annual income. Less than a fifth of parents’ highest level of education was a high school degree or less (11.1% of mothers and 18.7% of fathers), over half of parents had some college or completed college (61.6% of mothers and 52.2% of fathers), and more than a quarter of parents’ highest level of education involved some postgraduate training or completed postgraduate training (27.3% of mothers and 29.1% of fathers). Families consisted primarily of married parents living together (84.4%) and unmarried parents living together (11.9%).

Of the original 135 families who completed the 3-month lab visit, 130 completed the 5 month visit, 125 completed the 7-month visit, 124 completed the 12-month visit, and 117 completed the 14-month visit, yielding a low attrition rate of about 13% from the first to the fifth visit. Analyses comparing the sample of families who dropped out by the 14-month visit to those who remained in the study on demographic characteristics indicated that mothers whose highest level of education was high-school or less were more likely to drop out compared to those with higher education levels, χ2 (2) = 16.89, p < .001. In addition, families whose annual incomes were $29,999 or below per year had a higher drop-out than those with incomes greater than $30,000, χ2 (2) = 13.63, p < .01. Parents of minority ethnic status were also more likely to drop out: χ2 (1) = 7.86, p < .01 for mothers and χ2 (1) = 8.12, p < .01 for fathers. Paternal education level and cohabitation status did not differ for families who dropped out versus those who remained in the study. Thus, the generalizability of our findings is more limited to families who earned higher incomes, were Caucasian, and whose mothers were more educated.

Procedures

Parents who agreed to participate in the study were sent a packet of questionnaires to complete and bring with them to each laboratory visit. During each visit, infant-parent interactions were video-recorded using two separate video cameras, one focused on the infant and the other on the parent. The video-cameras recorded onto a split screen so coders were able to see both the parent and the infant simultaneously. Families were given a $25 gift card per visit to compensate for their participation.

3-, 5-, and 7-month visits

After consenting, parents were randomly assigned to participate first or second in the SFP (Tronick et al., 1978). The first parent entered the playroom and placed the infant in a booster seat on a table and then sat down and faced the infant directly. Parents were given verbal instructions about the procedure and were given written instructions to refer to if needed. The SFP involved three 90-s episodes—play, still-face, and reunion. For the play episode, parents were instructed to interact with their infant as they normally would until they heard a doorbell. During the still-face episode, parents ceased interacting with their infant, sat back in the chair, and maintained an expressionless face. This episode was shortened if the infant became overly upset, as was the case for three 3-month infant-father pairs, one 5-month infant-mother and infant-father pair, three 7-month infant-mother pairs, and one 7-month infant-father pair. Following a second doorbell, parents resumed interacting with their infant (reunion episode). Upon hearing a final doorbell, parents could remove the infant from the seat for a soothing episode, if they desired. Once the SFP was completed and the infant was once again in a neutral or positive state, the second parent entered and repeated the same procedure. Of interest in this study were parental behaviors observed during the play and reunion episodes, and infant behaviors during the still-face and reunion episodes.

12- and 14-month visit

To measure attachment security, the Strange Situation (Ainsworth et al., 1978) was conducted at 12 and 14 months. Mothers attended the 12-month visit, whereas fathers attended the 14-month visit. Parent order at the one-year visits was not counterbalanced given that there has been no evidence of order effects when there is at least a 4-week separation between assessments (e.g., Belsky, Rovine, & Taylor, 1984). The well-known Strange Situation procedure involves seven 3-minute episodes that are designed to elicit attachment and/or exploratory behavior in infants through a series of separations and reunions.

Measures

Three of the four sets of observational measures in this study--parental sensitivity, infant affect, infant behavioral responses--were rated by teams of coders in the first-author’s laboratory. To avoid bias, no coder rated more than one domain, and no coder rated the same infant with mothers and fathers within the same age group. For parent sensitivity, infant affect, and infant behavioral responses, gold standard coders (doctoral students) were selected by the first author based on their extensive knowledge of the literature and practice in coding for each measure. Each gold standard coder then trained their own team of coders until they achieved sufficient inter-rater reliability on a set of training tapes (intraclass correlations (ICCs) ≥ .80 for parent sensitivity and infant affect and Cohen’s κ ≥ .70 for infant behavioral responses). Once coders were reliable, they were then able to code independently. To calculate final reliabilities, the gold standard coder recoded a random subset of tapes (25%) completed by coders.

Parental Sensitivity

Sensitivity and intrusiveness were rated separately for each parent during the play and the reunion episodes of the SFP based on a reliable and valid rating system developed by Braungart-Rieker et al., 2001. In this system, parental sensitivity was rated using a 5-point Likert-type scale (1: no sensitivity to 5: high sensitivity) every 10-s. Similar to Ainsworth et al. (1978), high sensitivity was coded when a parent followed the infant’s gaze, read and responded to the child’s signals correctly, and made attempts to change the interaction if the infant was showing signals of boredom or distress. In contrast, low parental sensitivity was coded when the parent did not respond contingently to an infant’s signal by ignoring the signal or showing an inappropriate response (e.g., putting his/her face too close to the infant when the infant showed gaze aversion). The coder then assessed the degree to which the parent showed intrusive behaviors, also rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1: extremely intrusive to 5: no intrusiveness) every 10-s. Similar to Ainsworth et al. (1978), intrusiveness is observed when the parent overwhelms the infant with excessive stimulation by missing “slow-down” or “back-off” signals from the infant, is too rough with the infant, or fails to engage the level of interaction on the infant’s response to the previous interaction. ICCs ranged from .88 to .96 for sensitivity and from .85 to .96 for intrusiveness across age. Sensitivity and intrusiveness were highly correlated across age (range=.70 to .80). Thus, we averaged ratings for sensitivity and intrusiveness (note that high scores in intrusiveness reflect low intrusiveness) to create a new composite variable, hereon, parental sensitivity. High scores indicate high sensitivity/low intrusiveness.

Infant Affect

Infant affect, which included a combination of vocal and facial expressions, was rated on a second-by-second basis on a 7-point scale during all episodes of the SFP (Braungart-Rieker et al., 1998). Ratings ranged from −3 (e.g. screaming) to 3 (e.g. intensely laughing). ICCs ranged from .75 to .95 (M=.85) for all ages. Consistent with previous research, affect data were reduced to the proportion of time infants spent in positive and negative affect and log-transformed due to skewness (Braungart-Rieker et al., 1998). Additionally, all children who were highly fussy (negative affect was observed 95% or more of the time across all three episodes of the SFP) were excluded from all analyses because such extreme responses indicated an initial state of negativity that was not soothable (3 mo. Mother n=9; 3 mo. Father n=2; 5 mo. Father n=2; 7 mo. Mother n=3; 7 mo. Father n=1).

Infant Behavioral Responses

Infants’ behaviors were coded on a second-by-second basis as present or absent during the three episodes of the SFP. Similar to other studies, (Braungart-Rieker et al., 1998; Toda & Fogel, 1993) coders rated infants’ parent orientation, defined as focused looking toward the parent’s face; object orientation, defined as focused gaze toward objects (e.g., pictures on the wall, seat strap, hands, etc.); and self-comforting, defined as thumb or finger sucking, rubbing hands together, and other tactile behaviors aimed at the infants own body. Object and parent orientation were mutually exclusive with each other but self-comforting was not given that it could co-occur with either parent or object orientation. Escape and high intensity motor behaviors were also rated but were not included in the present study given that visual orientation and self-comforting have been conceptually and empirically supported as regulatory (Ekas et al., 2011; Stifter & Braungart, 1995). Cohen’s κ averaged .85 for parent orientation (range = .73 to .91) and .84 for object orientation (range = .71 to .92) across age (3, 5, 7 months), episode (play, still face, reunion), and parent context (mother, father). Proportion scores for each variable were created by summing the number of intervals in which the behavior was present, divided by the total number of intervals coded. Similar to affect measures, proportion scores were log-transformed. In addition, because parent orientation and object orientation were highly inversely related to each other (correlations averaged −.85 and ranged from −.61 to −.98) indicating substantially redundant information, we only included parent orientation in subsequent models.

Infant-Parent Attachment

Infants’ attachment classifications, coded from the Strange Situation, received a primary code of organized attachment (Ainsworth et al., 1978)—insecure-avoidant (A), secure (B), insecure-ambivalent (C), and a secondary code of attachment disorganization if the infant met criteria (D; Main & Solomon, 1986). A two-person coding team from the University of Minnesota headed by Dr. Elizabeth Carlson, rated attachment from the Strange Situation. To calculate inter-rater reliability, 16% of the infant-mother and 17% of the infant-father tapes were coded by both raters and yielded a 90% agreement with a Cohen’s κ = .84 for infant-mother dyads, and an 80% agreement with a Cohen’s κ = .71 for infant-father dyads.

Infant Negative Temperament

Infant temperament at 3, 5, and 7 months was measured using the Infant Behavior Questionnaire-Revised (IBQ-R; Gartstein & Rothbart, 2003), a 191-item measure with 14 scales. Following Putnam, Rothbart, and Gartstein (2008), we created a factor for negative temperament which includes four scales: distress to limitations, fear, sadness, and recovery (reverse scored). Mothers were asked to rate their infant’s behavior on a seven-point scale, ranging from ‘never’ to ‘always’ engaging in a behavior. Internal consistencies on the four scales at each age yielded Cronbach’s alphas of .64, .72, and .64 for 3, 5, and 7 month data, respectively.

Results

The results are presented in two sections. The first section presents descriptive results for the study variables, including cross-age, cross-parent, and cross-episode correlations, and within-age correlations between parent sensitivity and infant SFP responses. The second section presents results that address the major aims of this study, including the degree to which infant SFP response trajectories across 3, 5, and 7 months are related to parental sensitivity at 3, 5, and 7 months and infant-mother and infant-father attachment at 12 and 14 months, respectively.

Descriptive Results

Table 1 presents the means and standard deviations for infant and parent measures across parent contexts. Effects for Age, Episode, and Parent are further examined in the next section. Main effects for parent order (mother- vs. father-first), however, were tested here. As can be seen from Table 1, a number of significant differences emerged. In some cases, order had a similar effect when infants were interacting with mothers or fathers. For example, infants showed more parent orientation toward mothers at 3 months if mothers participated as the first parent and showed more parent orientation toward fathers at 3 months if fathers participated as the first parent. In other cases, order effects were present with one parent but not the other. For example, infants showed more self-comforting at 5 months toward fathers during the still-face episode when fathers served as the first parent, but this pattern was not observed with mothers when mothers served as the first parent. In addition, mothers were more sensitive during the play episode at 5 and 7 months when they went first, and fathers were more sensitive during the reunion episode at 7 months when they participated first in the SFP. Therefore, all subsequent analyses include order as a covariate.

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations for Infant and Parent SFP Responses by Age, Episode, and Parent, and Testing for Order Effects

| Infant-Mother | Infant-Father | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| SFP Response | 3 month M (SD) (n = 119) |

5 month M (SD) (n = 124) |

7 month M (SD) (n = 118) |

3 month M (SD) (n = 122) |

5 month M (SD) (n = 123) |

7 month M (SD) (n = 119) |

| Infant Positive Affect | ||||||

| Play F-first | .16 (.08)a | .25 (.14) | .25 (.13) | .20 (.11)a | .21 (.12) | .22 (.12) |

| Play M-first | .23 (.13)b | .29 (.16) | .26 (.14) | .17 (.09)b | .20 (.11) | .23 (.15) |

| Still-Face F-first | .12 (.07) | .12 (.05) | .14 (.09) | .11 (.04) | .13 (.07) | .16 (.09)a |

| Still-Face M-first | .13 (.06) | .13 (.05) | .14 (.08) | .11 (.03) | .13 (.07) | .12 (.06)b |

| Reunion F-first | .16 (.07) | .22 (.14)a | .26 (.14) | .17 (.08) | .22 (.13) | .22 (.12) |

| Reunion M-first | .19 (.09) | .28 (.17)b | .24 (.13) | .14 (.07) | .21 (.13) | .23 (.16) |

| Infant Negative Affect | ||||||

| Play F-first | .17 (.17) | .12 (.06)a | .16 (.14)a | .15 (.14) | .11 (.03) | .11 (.04) |

| Play M-first | .14 (.13) | .10 (.01)b | .10 (.04)b | .16 (.16) | .14 (.13) | .12 (.07) |

| Still-Face F-first | .21 (.16)a | .25 (.20)a | .23 (.19)a | .19 (.17) | .13 (.09)a | .14 (.12)a |

| Still-Face M-first | .13 (.08)b | .14 (.10)b | .12 (.06)b | .22 (.18) | .19 (.16)b | .21 (.16)b |

| Reunion F-first | .23 (.22)a | .19 (.17)a | .25 (.21)a | .17 (.15) | .14 (.13)a | .14 (.12)a |

| Reunion M-first | .16 (.17)b | .12 (.05)b | .14 (.12)b | .23 (.23) | .21 (.19)b | .21 (.20)b |

| Infant Parent Orient. | ||||||

| Play F-first | .53 (.16)a | .50 (.15) | .48 (.15) | .64 (.12)a | .48 (.18) | .41 (.14)a |

| Play M-first | .59 (.16)b | .53 (.17) | .46 (.17) | .56 (.16)b | .50 (.16) | .47 (.15)b |

| Still-Face F-first | .38 (.17)a | .27 (.12) | .29 (.12)a | .47 (.17)a | .28 (.15) | .27 (.10) |

| Still-Face M-first | .47 (.17)b | .29 (.15) | .24 (.15)b | .40 (.17)b | .27 (.13) | .25 (.10) |

| Reunion F-first | .51 (.18)a | .50 (.17) | .51 (.17)a | .62 (.10)a | .50 (.15) | .46 (.15) |

| Reunion M-first | .60 (.13)b | .52 (.16) | .46 (.15)b | .53 (.17)b | .48 (.18) | .48 (.15) |

| Infant Self-Comfort. | ||||||

| Play F-first | .23 (.15) | .19 (.14) | .16 (.11) | .18 (.13) | .18 (.15) | .13 (.08)a |

| Play M-first | .19 (.13) | .17 (.12) | .17 (.13) | .18 (.13) | .17 (.12) | .17 (.12)b |

| Still-Face F-first | .18 (.08)a | .23 (.10) | .26 (.11) | .14 (.04)a | .17 (.10)a | .23 (.11) |

| Still-Face M-first | .13 (.04)b | .20 (.11) | .25 (.12) | .20 (.08)b | .23 (.11)b | .24 (.11) |

| Reunion F-first | .21 (.14) | .21 (.14)a | .17 (.12) | .23 (.17) | .18 (.13) | .13 (.06)a |

| Reunion M-first | .23 (.18) | .15 (.07)b | .21 (.15) | .18 (.12) | .14 (.08) | .17 (.10)b |

| Parent Sensitivity | ||||||

| Play F-first | 4.28 (.55) | 4.15(.58)a | 4.32(.43)a | 4.21 (.53) | 4.16 (.55) | 4.30(.49) |

| Play M-first | 4.32 (.59) | 4.41(.42)b | 4.51(.39)b | 4.18 (.49) | 4.10 (.63) | 4.12(.49) |

| Reunion F-first | 4.13 (.51) | 4.10(.61) | 4.27(.58) | 4.08 (.60) | 4.04 (.65) | 4.24(.57)a |

| Reunion M-first | 4.24 (.50) | 4.29(.46) | 4.40(.50) | 3.96 (.68) | 4.07 (.66) | 4.01(.57)b |

Note: M-first = Mother participated first and father participated second in the SFP; F-first = Father participated first and mother participated second in the SFP. Superscripts of a vs. b = significant (p < .05) effects for parent order within age and episode when comparing means when mother went first vs. father went first.

Table 2 presents the frequencies, percentages, and concordance rates of infant-mother and infant-father attachment groups. The upper portion of the table indicates rate for infants’ primary attachment classifications (A, B, C) with mothers and fathers, whereas the lower portion of the table indicates rates for infants’ secondary attachment classification (D) with each parent. The distribution of infant classifications was fairly equivalent across infant-mother and infant-father dyads. In addition, chi-square tests examining the frequency distribution of infant attachment classifications across dyads were nonsignificant for the ABC classification, χ2 (4) = 9.05, p < .10, and for the D classification, χ2 (1) = 2.78, p < .10, indicating a relative independence in attachment across infant-parent dyads.

Table 2.

Frequencies and Percentages of Infants’ Attachment with Mothers and Fathers: Primary Attachment Classification and Attachment Disorganization Classification

| Mother-Infant Primary Attachment Classification | Father-Infant Primary Attachment Classification

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avoidant | Secure | Ambivalent | TOTAL n | |

| Avoidant (A) | 2 (1.75%) | 6 (5.26%) | 2 (1.75%) | 10 |

| Secure (B) | 9 (7.89%) | 74 (64.91%) | 6 (5.26%) | 89 |

| Ambivalent (C) | 0 (0.00%) | 11 (9.65%) | 4 (3.51%) | 15 |

| TOTAL n | 11 | 91 | 12 | 114a |

| Mother-Infant Attachment Disorganization | Father-Infant Attachment Disorganization | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Organized | Disorganized | TOTAL n | |

| Organized (A, B, C) | 82 (70.69%) | 15 (12.93%) | 97 |

| Disorganized (D) | 13 (11.21%) | 6 (5.17%) | 19 |

| TOTAL n | 95 | 21 | 116a |

There were two fewer infant-father dyads rated in the ABC classification because those infants were classified as D/A/C and thus not classifiable in the traditional ABC system.

Table 3 presents the longitudinal and cross-parent partial correlations for SFP measures, controlling for parent order. Positive affect during the infant-mother SFP showed modest but significant levels of stability for six of the nine longitudinal correlations; all other infant measures yielded two or fewer significant longitudinal correlations from 3 to 5 to 7 months. In addition, maternal sensitivity showed significant age-related stability during the reunion but not play episodes. Paternal sensitivity, however, was significantly stable over time during both play and reunion episodes. Significant cross-parent correlations indicated that infants showed moderate levels of consistency in behavior across parent contexts. Mothers and fathers were also significantly consistent in sensitivity with each other at 3 but not at 5 or 7 months (See Table 3).

Table 3.

Longitudinal and Cross-Parent Partial Correlations Among Infant and Parent Measures at 3, 5, and 7 Months Within Each Episode, Controlling for Parent Order

| Longitudinal Correlations

|

Cross-Parent Correlations | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infant-Mother | Infant-Father | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| SFP Response | 3m–5m n=119 |

5m–7m n=112 |

3m–7m n=116 |

3m–5m n=120 |

5m–7m n=115 |

3m–7m n=116 |

3m n=118 |

5m n=122 |

7m n=117 |

| Pos. Affect | |||||||||

| Play | .15 | .22* | .20* | −.06 | .25** | .14 | .17 | .23* | .47*** |

| Still-Face | .38*** | .09 | .08 | −.07 | .20* | .16 | .34*** | .20* | .39*** |

| Reunion | .21* | .19* | .32*** | .01 | .14 | .17 | .40*** | .28** | .41*** |

| Neg. Affect | |||||||||

| Play | .00 | .00 | .22* | .02 | .02 | .17 | .07 | .11 | .27** |

| Still-Face | .19 | .15 | −.05 | .10 | .12 | −.09 | .13 | .33*** | .17 |

| Reunion | .05 | .00 | −.01 | .16 | .10 | .08 | .07 | .19* | .39*** |

| Parent Or. | |||||||||

| Play | .15 | .10 | .02 | −.02 | .15 | −.04 | .38*** | .20 | .33** |

| Still-Face | −.02 | .26* | −.04 | −.05 | .04 | .16 | .20 | .24* | .24* |

| Reunion | .06 | .19 | .20 | −.01 | −.06 | .12 | .17 | .29** | .28** |

| Self-Comf. | |||||||||

| Play | .01 | .03 | .03 | −.07 | .20* | −.04 | .36*** | .22* | .12 |

| Still-Face | .09 | −.05 | −.05 | .14 | .16 | .07 | .16 | .52*** | .46*** |

| Reunion | .04 | −.12 | −.12 | .02 | .23* | −.06 | .26*** | .30** | .29** |

| Parent Sen. | |||||||||

| Play | .18 | .15 | .11 | .24* | .26** | .33*** | .19* | .15 | .16 |

| Reunion | .20* | .23* | .13 | .30** | .30** | .22* | .21* | .15 | .12 |

Note:

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

Pos. = Positive; Neg. = Negative; Or. = Orientation; Comf. = Comforting; Sen.= Sensitivity

Within-age cross-episode partial correlations for SFP behaviors, controlling for parent order were computed as well. Cross-episode (play to still-face, still-face to reunion, and play to reunion) correlations for infant positive affect, negative affect, and parent orientation were all significant and averaged .47 for infant-mother dyads (rs ranged from .22 to .71, ps < .05) and .49 for infant-father pairs (rs ranged from .27 to .72, ps < .05). In addition, parents were highly consistent from play to reunion in sensitivity at each age (rs range from .73 to .80 for mothers and .74 to .81 for fathers, ps < .001). Infant self-comforting, however, was less consistent across episodes; correlations were nonsignificant from play to still-face and still-face to reunion but were significant from play to reunion: rs = .35 to .53, ps < .001 for infant-mother pairs and rs = .37 to .54, ps < .001 for infant-father pairs.

To examine the degree to which infant and parent SFP variables at 3, 5, and 7 months and attachment styles (A, B, C) and attachment disorganization (D) were related to demographic factors (infant gender, family income, maternal and paternal education, cohabitation status, minority status) 310 correlations, chi-square tests, or ANOVAs were conducted, depending on the scaling properties of the pairs of variables. Of these, 17 were significant, which is equal to the amount expected that would be due to chance (.05). Thus, none of the demographic variables was included as covariates.

Finally, we calculated partial correlations between parent sensitivity and infant SFP responses within each age, episode, and parent context, controlling for parent order. Correlations are presented in Table 4. Of the 48 correlations within each infant-parent dyad, 11 were significant for infant-mothers and 11 were significant for infant-fathers. Infants whose mothers were more sensitive showed more positive affect, parent orientation, and self-comforting, and less negative affect at 5 and/or 7 months but not at 3 months than infants whose mothers were less sensitive. Likewise, infants whose fathers were more sensitive showed more positive affect and less negative affect across all three ages than infants whose fathers were less sensitive. Parent orientation and self-comforting were not significantly related to parent sensitivity, however, at any of the three ages for infant-father pairs.

Table 4.

Within-age Correlations Between Parental Sensitivity and Infant SFP Responses, Controlling for Parent Order

| Infant SFP Response | 3 month Sensitivity | 5 month Sensitivity | 7 month Sensitivity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Play | Reunion | Play | Reunion | Play | Reunion | |

| Mother-Infant | n = 119 | n = 124 | n = 118 | |||

| Positive Affect | ||||||

| Still-Face | −.10 | −.02 | .21* | .14 | .21* | .13 |

| Reunion | .09 | .10 | .14 | .22* | .18 | .16 |

| Negative Affect | ||||||

| Still-Face | .06 | .11 | .21* | .16 | −.02 | −.02 |

| Reunion | .00 | .03 | .16 | .04 | −.23* | −.34*** |

| Parent Orientation | ||||||

| Still-Face | .10 | −.02 | .20* | .10 | .25* | .26** |

| Reunion | .08 | .09 | −.06 | .00 | .09 | .19* |

| Self-Comforting | ||||||

| Still-Face | −.12 | −.01 | −.00 | −.06 | −.04 | −.12 |

| Reunion | .16 | .08 | .18* | .14 | .05 | .08 |

| Father-Infant | n = 122 | n = 123 | n = 119 | |||

| Positive Affect | ||||||

| Still-Face | .11 | .12 | .17 | .18* | .08 | .10 |

| Reunion | .20* | .29** | .13 | .05 | .20* | .30** |

| Negative Affect | ||||||

| Still-Face | −.14 | −.15 | −.02 | −.18* | −.14 | −.18* |

| Reunion | −.22* | −.31*** | −.01 | −.19* | −.09 | −.26** |

| Parent Orientation | ||||||

| Still-Face | .15 | .09 | −.02 | .05 | .08 | .15 |

| Reunion | .05 | .11 | .01 | .07 | .09 | .13 |

| Self-Comforting | ||||||

| Still-Face | .04 | .10 | .05 | .01 | .18 | .16 |

| Reunion | .12 | .08 | .08 | .09 | −.10 | −.05 |

Infant and Parent SFP Trajectories

To test the degree to which sensitivity predicted infant SFP trajectories during still-face and reunion and the degree to which attachment groups distinguished SFP trajectories for infant responses and parent sensitivity, we relied on Multilevel Modeling (MLM; Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002) using SAS PROC MIXED (see Singer, 1998 for a description). MLM is a technique that is well suited for longitudinal data, especially if there are missing data. Our longitudinal analyses involved three steps. First, we tested base models for SFP trajectories that included random effects for Intercept, Age, Episode, Parent, Parent Order, and each two-way interaction. In addition, we included two covariates: infant behavior during the play episode to control for baseline levels of behavior and negative temperament to control for general intrinsic aspects of infant reactivity. Unconditional models in which no covariates are included were not tested because we wanted to ensure that significant variation in the parameters of interest was not attributed to variation in covariates. Age, Episode, and Parent are considered level-1 variables, whereas Parent Order is considered a level-2 predictor. Second, we tested conditional models that included all parameters from the base models as well as parental sensitivity as a level 2 predictor of infant SFP trajectories. Third, we conducted conditional models in which infant-parent attachment style as level-2 variables predicted infant and parent SFP trajectories. In addition, all predictor variables except Age were grand-mean centered so that coefficients reflect average effects for each individual. Age was centered at 3 months to reflect the starting point of the study.

Base models

Five models were conducted to determine the pattern of trajectories for positive affect, negative affect, parent orientation, self-comforting, and parent sensitivity predicted by Age (in months), Episode (still-face and reunion for infant measures; play and reunion for parent sensitivity measures), Parent Gender, Parent Order, and two-way interactions among these factors. Infants’ corresponding behavior during the play episode and infant negative temperament were also entered as covariates in each model. This model allowed us to test for both mean level variation (differences from zero) and individual variation for all parameters. To determine whether linear age (full) models fit better than intercept-only (reduced) models, we calculated the change in −2 Log Likelihood estimates across models (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2006). In each case, the change in fit was significantly (p < .05) worse when age effects were excluded in the models. Thus, all subsequent models included linear age effects.

Table 5 presents the parameter estimates from the base models. All five models indicated that the mean level of each variable was significantly greater than zero. In addition, a number of mean level effects emerged for Age, Episode, Parent, and Order. Specifically, Age-related slope estimates indicated that on average, infants showed increases in positive affect and self-comforting and decreases in parent orientation over time. Parents also showed increases in parent sensitivity over time. Episode effects revealed that infants showed significant increases in positive affect, parent orientation, and self-comforting from still-face to reunion, whereas parents were less sensitive during reunion than during play. Mean level Parent effects indicated that infants showed less negative affect with fathers than with mothers during the SFP.

Table 5.

Base Models for Infant and Parent SFP Response Trajectories, Testing for Intercept, Age, Episode, Parent Order, and Interactions, Controlling for Infant Play Responses, Parent Sensitivity during Play, and Negative Temperament.

| Parameter | Positive Affect | Negative Affect | Parent Orientation | Self-Comforting | Parent Sensitivity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Individual Variation | Mean | Individual Variation | Mean | Individual Variation | Mean | Individual Variation | Mean | Individual Variation | |

| Intercept (SE) | .098 (.007)*** | .000 (.000) | .102 (.013)*** | .007 (.001)*** | .246 (.018)*** | .003 (.001)** | .156 (.008)*** | 0 | 4.09 (.051)*** | .181 (.034)*** |

| Age (SE) | .012 (.002)*** | .0001 (.0000)* | −.002 (.004) | .0001 (.000)*** | −.009 (.004)** | 0 | .007 (.003)** | .000 (.000) | .040 (.016)** | .009 (.002)*** |

| Episode1 (SE) | .054 (.010)*** | .002 (.001)*** | −.013 (.012) | 0 | .153 (.013)*** | .000 (.000) | .052 (.012)*** | .003 (.001)** | −.132 (.039)** | 0 |

| Parent (SE) | −.002 (.009) | .000 (.000) | −.069 (.013)*** | .003 (.001)** | .034 (.012)* | .001 (.001) | −.016 (.011) | 0 | .024 (.052) | .132 (.025)*** |

| Order (SE) | .006 (.007) | .000 (.000) | −.022 (.015) | .004 (.002)** | .033 (.013)* | .004 (.001)** | −.003 (.009) | 0 | .106 (.059) | .068 (.023)** |

| A X E (SE) | .015 (.003)*** | .000 (.000) | .002 (.004) | .000 (.000) | .022 (.004)*** | .000 (.000) | −.031 (.004)*** | −.0004 (.0002)* | .021 (.013) | .001 (.004) |

| A X P (SE) | −.000 (.003) | .000 (.000) | −.003 (.004) | .000 (.000) | −.004 (.004) | .000 (.000) | −.007 (.004) | .000 (.000) | −.024 (.013) | −.001 (.005) |

| A X O (SE) | −.002 (.003) | .000 (.000) | .002 (.005) | −.001 (.000) | −.017 (.005)*** | .000 (.000) | .000 (.004) | −.000 (.000) | −.018 (.021) | −.000 (.005) |

| E X P (SE) | −.035 (.009)*** | −.001 (.000)* | .012 (.013) | −.000 (.001) | −.013 (.014) | −.001 (.001) | −.013 (.012) | −.002 (.001)** | −.011 (.043) | .017 (.013) |

| E X O (SE) | .010 (.010) | .000 (.000) | .007 (.013) | .000 (.001) | .001 (.014) | .000 (.001) | −.013 (.012) | .000 (.001) | −.019 (.042) | −.009 (.013) |

| P X O (SE) | −.017 (.009) | .000 (.000) | .148 (.014)*** | .006 (.001)*** | −.054 (.014)*** | .001 (.001) | .024 (.012)* | −.001 (.000)* | −.260 (.049)*** | .015 (.018) |

| Play Behavior (SE) | .235 (.021)*** | NA | .744 (.048)*** | NA | .376 (.025)*** | NA | .164 (.024)*** | NA | NA | NA |

| Sensitivity Play (SE) | .003 (.005) | NA | .017 (.008)* | NA | .011 (.008) | NA | −.004 (.006) | NA | NA | NA |

| Negative Temp. (SE) | .003 (.004) | NA | .014 (.008) | NA | .004 (.007) | NA | −.011 (.006)* | NA | −.014 (.035) | NA |

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001. A = Age; E = Episode; P = Parent; O = Order; Temp. = Temperament; NA = Not applicable.

Episode effects involve still-face and reunion for infant positive affect, negative affect, parent orientation, and self-comforting and play and reunion for parent sensitivity measures.

In addition to main effects, a number of interactions emerged as well (see Table 5). For the sake of brevity, however, we limit our description to those of most relevance to the study’s aims: Age X Episode, Age X Parent, and Episode X Parent, and not those involving Parent Order. More specifically, patterns (see also Table 1) indicated that infants showed greater increases in positive affect and parent orientation from still-face to reunion as they got older. In addition, infants showed increases in self-comforting from still-face to reunion at 3 months but showed decreases in self-comforting at 5 and 7 months. Significant Episode X Parent effects indicated that infants showed greater increases in positive affect from still-face to reunion with mothers than with fathers. There were no significant Age X Parent effects, however, indicating that infants did not show differential rates of change in behaviors across age with mothers vs. fathers. Finally, results involving covariates indicated that SFP responses during the initial play episode of the SFP were each significantly related to their respective trajectories, whereas negative temperament was not significantly associated with responses during the SFP. Parental sensitivity during play, which was included as a covariate for subsequent conditional models examining infant SFP-attachment linkages was significant for negative affect trajectories. All terms, significant or not, were included in subsequent conditional models to control for even low levels of potential influence.

Conditional models

Two sets of conditional models were subsequently examined—one involving the degree to which parent sensitivity predicted infant SFP trajectories and one involving the degree to which infant attachment predicted parental and infant SFP trajectories. For models examining sensitivity and infant SFP associations, parent sensitivity was treated as a time varying covariate that was allowed to vary across age, episode, and parent. Models testing for associations between attachment and infant and parent SFP trajectories included six dummy coded variables (A, C, and D for each infant-parent dyad), with B (secure) serving as the reference group for each dyad. Attachment styles were treated as fixed effects given that they were assessed at only one point in time.

In addition, only parameters that had significant individual variation in base models were subsequently examined in conditional models. Table 6 presents a summary of those parameters that were tested in each model as well as which parameters yielded significant findings. The specifics of each result are presented below. To the extent that parameters were significant in conditional models, we calculated effect sizes (Pseudo R2) by comparing the residual variances from base models, full models, and models in which the significant parameter is excluded (Peugh, 2010). Effect sizes (ES) of .02 are considered small, .15 are medium, and effect sizes of .35 are large (Singer & Willett, 2003).

Table 6.

An Overview of Parameters that were Tested (√) in Conditional Models, Estimates that were Significant in Conditional Models Examining Sensitivity (Sens), or Estimates that were Significant in Models Examining Attachment (M- or F-; A, B, C, or D)

| Positive Affect | Negative Affect | Parent Orientation | Self-Comforting | Parent Sensitivity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | √ | √ Sens M-D |

√ M-A F-A |

||

| Age | √ Sens M-C |

√ | √ | ||

| Episode | √ Sens M-C |

√ Sens M-C |

|||

| Parent | √ Sens | √ M-C | |||

| Age X Episode | √ F-C F-D |

||||

| Episode X Parent | √ | √ M-C |

Note: √ indicates the parameters that showed sufficient individual variation to be tested for each model. When parameters were significant (p < .05), the table indicates if this was for a model examining sensitivity (Sens) or attachment. In the latter, details about whether the attachment involved the mother vs. father (M vs. F) and which style of attachment (A, C, D) are indicated.

For models testing the degree to which sensitivity predicted infant SFP responses, all four yielded significant results as can be seen in Table 6. Two of the three parameters that were tested in the model examining positive affect were significant—Age and Episode. Parents who were more sensitive had infants who showed greater increases in positive affect from 3 to 7 months (Est. = .008, SE = .002, p < .001, ES = .33). Greater sensitivity was also associated with steeper increases in positive affect from the still-face to reunion episodes (Est. = .035, SE = .009, p < .001; ES = .28). One of the three parameters tested in conditional models examining negative affect trajectories was significant. Infants showed less negative affect with fathers when parent sensitivity was higher (Est. = −.039, SE = .013, p < .01, ES =.39). Infants whose parents were more sensitive also showed higher initial levels of parent orientation (Est. = .026, SE = .011, p < .05, ES = .23) than those whose parents were less sensitive. Finally, infants whose parents were more sensitive showed greater increases in self-comforting from still-face to reunion (Est. = .035, SE = .018, p < .05, ES = .44).

Next, we tested conditional models examining the degree to which attachment is related to SFP trajectories. As with the models examining linkages between parent sensitivity and infant SFP responses, we included parent order, and their interactions with random effects (Age, Episode, and Parent); we also included the relevant infant SFP response during the play episode and negative temperament as covariates. An additional covariate was included in the models examining infant SFP responses—parent sensitivity during the play episode. Because parent sensitivity was assessed in the same context as infant responses, we can more strongly test whether infant responses during the SFP are indeed reflecting more than just their immediate reactions to parental sensitivity during the initial episode.

As can be seen in Table 6, the model examining parental sensitivity and attachment classifications yielded several significant findings. Mothers (Est. = −.376, SE = .151; p < .01, ES = .20) and fathers (Est. = −.421, SE = .127, p < .001, ES = .60) of infants later classified as avoidant showed lower initial levels of sensitivity than those later classified as secure with each parent. In addition, a significant Parent effect indicated that fathers of infants later classified as ambivalent with mothers were more sensitive than fathers of infants classified as secure with mothers (Est. = .273, SE = .129, p < .05, ES = .20). As also seen in Table 6, three of the four models examining relations between attachment style and infant SFP responses yielded significant results. Infants later classified as ambivalent with mothers showed less of an increase in positive affect over time (Est. = −.010, SE = .004, p < .05, ES = .10) and episode (Est. = −.041, SE = .021, p < .05, ES = .07) compared with those classified as secure.

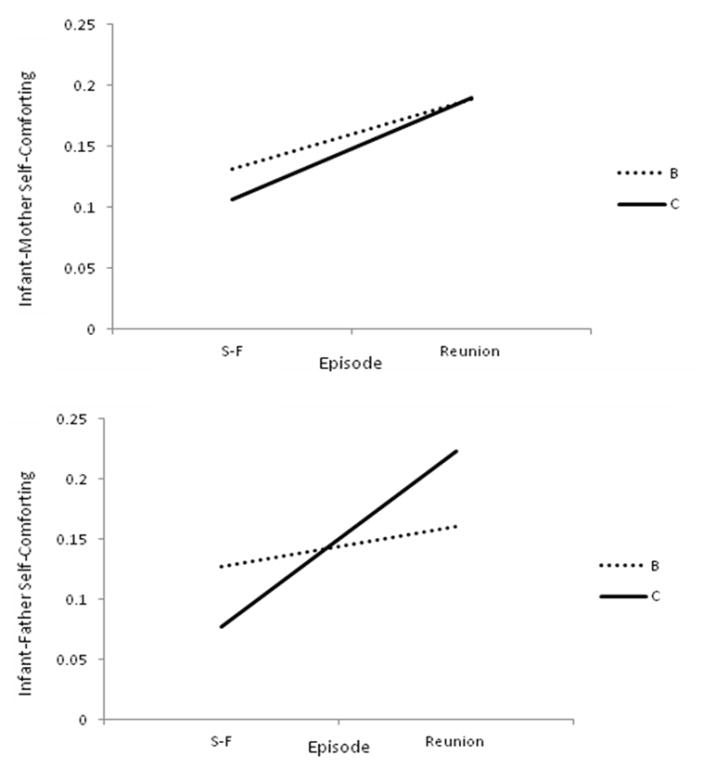

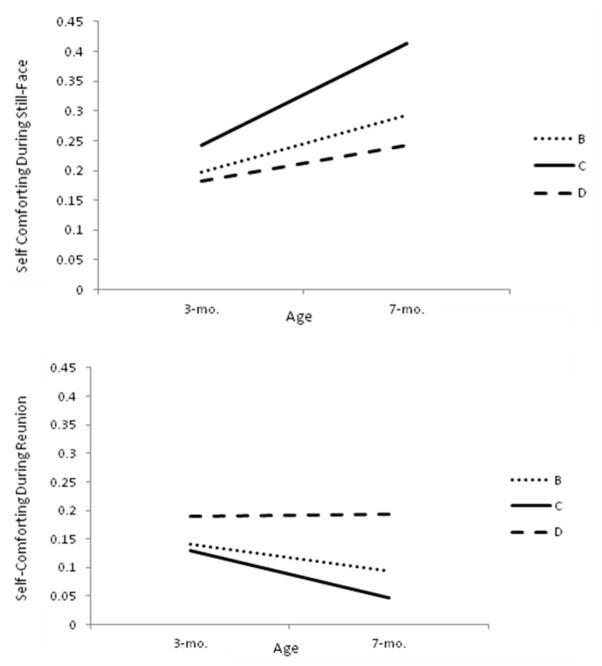

Although models testing negative affect with attachment classifications did not yield significant results, several significant results emerged for the models examining parent orientation and self-comforting. Infants later classified as disorganized with mothers showed lower initial levels of parent orientation than those classified as secure (Est. = −.032, SE = .014, p < .05, ES = .67). Significant Episode and Episode X Parent effects for self-comforting indicated that compared to infants later identified as secure with mothers, those later classified as ambivalent with mothers showed greater increases in self-comforting from still-face to reunion (Est. = .076, SE = .035, p < .05, ES = .08), particularly with fathers (Est. = .087, SE = .040, p < .05, ES = .15). Figure 1 depicts this interaction. In addition, Age X Episode effects indicated that relative to infants who were secure with fathers, those classified as disorganized with fathers maintained heightened levels self-comforting from 3 to 7 months, particularly during the reunion episode (Est. = .021, SE = .011, p < .05, ES = .15). A contrasting pattern emerged for infants classified as ambivalent with fathers who showed greater increases in self-comforting with age during still-face but greater decreases with age during reunion, relative to those classified as secure (Est. = −.028, SE = .011, p < .05, ES = .19). Figure 2 combines these two interactions (Age X Episode X ambivalent dummy code and Age X Episode x disorganized dummy code).

Figure 1.

Episode X Parent interaction depicting self-comforting from still-face to reunion with mothers versus fathers for infants classified as secure and ambivalent with mothers

Figure 2.

Age X Episode interactions depicting self-comforting over time during the still-face versus reunion episode for infants classified as secure, ambivalent, and disorganized with fathers

Discussion

This is the first study to demonstrate that longitudinal trajectories of infant affective and behavioral responses during the phase of Attachment in the Making (3 to 7 months) were related to concurrent measures of parental sensitivity as well as to later assessments of infant-mother and infant-father attachment during the Clear Cut Attachment phase (12+ months). Early parental sensitivity trajectories were also related to later infant-parent attachment. Below, we discuss these findings in more detail.

Parent Sensitivity and Infant SFP Trajectories

In terms of how parental sensitivity related to infant SFP trajectories, both similarities and differences in infant-mother and infant-father dyads emerged. We found that infants whose parents were more sensitive showed greater increases in positive affect over time, even after controlling for levels of positive affect during play and parental ratings of negative temperament. This finding suggests that the processes linking early caregiving experiences with infant affect may operate fairly similarly for infant-mother and infant-father relationships. To our knowledge, this is the first study to show linkages between parental sensitivity and age-related changes in infants’ affective responses. Such changes in positive affect that are associated with parental sensitivity during the phase of Attachment in the Making could reflect infants’ emerging internal working models of the infant-parent relationship. Sensitivity was also associated with episode-related changes for both positive affect and self-comforting. Infants with more sensitive mothers and fathers showed greater increases in positive affect and self-comforting as they transitioned from the still-face to the reunion episode of the SFP. This pattern perhaps reflects greater affect recovery. More sensitive parents seem to be better attuned to infants’ emotional signals and engage in behaviors that help infants re-engage in more positive play (Leerkes, 2011).

Greater sensitivity was also related to higher levels of visual orientation toward parents across still-face and reunion episodes. This is similar to a finding from one of the only other studies that examined both mothers and fathers during the still-face episode which found that ratings of parent sensitivity and synchrony were related to increased levels of parent orientation during the still-face episode (Braungart-Rieker et al., 1998). Heightened parent orientation during the still-face episode may indicate infants’ more positive expectations about parental responsiveness, whereas orienting more toward parents during reunion episodes may indicate more synchronous exchanges between infants and parents during the recovery process. It is important to keep in mind that unlike previous studies, we controlled for levels of parent orientation from the play episode as well as parental ratings of negative temperament in our models. This supports the notion that orientation toward caregivers during still-face and reunion does not just reflect merely state- or trait-like tendencies.

Only one model testing parent sensitivity-infant SFP linkages in this study yielded results that were more specific to a particular infant-parent dyad. Infants of less sensitive fathers showed more negative affect overall (across age and episode) than infants of more sensitive fathers. This result is similar to one of only two other studies examining father sensitivity and infant negative affect during the SFP at 6 months (Forbes et al., 2004). This finding suggests several possible processes. Perhaps infants who show more negative affect across episodes of the SFP and over time are more temperamentally negative in general (Braungart et al., 1998), and fathers perhaps react to fussier infants in a consistently less sensitive manner. In this case, the direction of effects flows from infant to father. However, we statistically controlled for both infant negative temperament and infants’ negative affect during the play episode. Thus, another possibility is that fathers with lower sensitivity are consistently eliciting increased levels of negative affect from infants. In this scenario, the direction of effects flows from father to infant. It is also possible that both processes are at play that result in a fairly stable system across episodes and over time.

Parental and Infant SFP Responses and Infant-Parent Attachment

In this study, we hypothesized that both parental sensitivity and infants’ affective and behavioral response trajectories during the SFP would predict infant-parent attachment later in infancy. In brief, we found that avoidant, ambivalent but not disorganized attachment classifications were related to parental sensitivity trajectories. In addition, ambivalent and disorganized but not avoidant attachment classifications were associated with infant affective and behavioral response trajectories. Below, we discuss these results in more detail.

Parental sensitivity trajectories - attachment

As expected, parent sensitivity trajectories were significantly related to insecure-avoidant attachment classifications. Mothers and fathers of infants later classified as avoidant showed lower initial levels of sensitivity during the SFP than those classified as secure. Our results are compatible with previous research showing that infants whose mothers (e.g., de Wolff & van IJzendoorn, 1997) and fathers (e.g., van IJzendoorn & de Wolff, 1997) are less sensitive are at risk for developing an insecure attachment relationship.

Interestingly, somewhat different patterns emerged for mothers of ambivalent infants versus fathers of ambivalent infants. Significant parent effects indicated that mothers of ambivalent infants engaged in less sensitive behaviors than did their spouse when interacting with these same infants. These results suggest interesting family-level dynamics. Nearly 75% of infants classified as ambivalent with mothers in this sample were classified as secure with fathers. In one of the only other studies examining cross-parent associations at one year of age, Schoppe-Sullivan, Diener, Mangelsdorf, Brown, McHale, and Frosch (2006) found that fathers were more sensitive toward sons with an insecure relationship with their mothers. Thus, it is possible that in these cases, fathers are serving in a more compensatory role in their relationship with the infant. Moreover, research has found that children benefit from having at least one parent with whom they are secure. In research comparing socio-emotional outcomes in preschool aged (Verschueren & Marcoen, 1999) and school-aged children (Kochanska & Kim, 2013), having one secure relationship appears to buffer against some of the negative effects of having an insecure attachment relationship with both parents, though having a secure attachment relationship with both parents is more optimal. Although we were not able to explicitly test such patterns in our data due to a relatively small number of infants who were insecure-ambivalent with both parents (n = 6), future research involving attachment with mothers and fathers should examine potential buffering and compensatory patterns by considering the various combinations of attachment styles children can develop.

Although it is not entirely clear why paternal sensitivity did not appear to differ for those who develop an ambivalent style of attachment with fathers, some have suggested that parents of ambivalent infants are more inconsistent in their behavior (Cassidy & Berlin, 1994). In other words, parents of ambivalent infants can show sensitive responding but not as much as infants may require. Perhaps by examining fathers in a more intensely emotionally laden situation or one that is longer in duration than the SFP would be a more definitive way to assess inconsistent responding.

In addition, sensitivity did not differ for infants later classified as disorganized. Previous research has found that aspects of parenting in addition to sensitivity as well as parents’ own childhood histories may be particularly relevant in the development of disorganized attachment. For example, parents who show frightened or frightening behavior (Main & Hesse, 1990) and other atypical behaviors (Madigan, Benoit, & Boucher, 2011) have been associated with the disorganized classification. We did not code for nor are we likely to observe such behaviors during the SFP. In addition, infants whose mothers have an unresolved attachment history are at risk for developing disorganized attachment behavior (Madigan, Bakermans-Kranenburg, van IJzendoorn, Moran, Pederson, & Benoit, 2006), though this was not the case for those whose fathers have an unresolved attachment history (Steele, Steele, & Fonagy, 1996). Thus, to better understand the link between infant behavioral reactions during the SFP and later disorganized attachment, future research should assess a broad array of parenting in multiple contexts.

Infant response trajectories - attachment

Infants who later developed an ambivalent attachment relationship with mothers showed a slower rate of increase in positive affect over time and from the still-face to reunion episodes. This is the first study to test for and detect age- and context-related changes in affect. Thus, dampened levels of positive affect that emerge during the phase of Attachment in the Making or during periods in which the infant-parent relationship requires some repair appear to reflect a developing negative internal working model of the infant-parent relationship. Given these patterns with positive affect, it is rather surprising that links did not emerge between attachment classification and negative affect. Meta-analytic results (Mesman et al., 2009) indicated significant associations between negative affect during the SFP and insecure attachment, though not across all studies (see Cohn et al., 1991). There is some evidence that positive affect is more susceptible than negative affect to environmental input. First, positive and negative affect do not appear to reflect opposite ends of a single dimension. Rather, there is substantial evidence that positive and negative affect are relatively independent constructs (Watson & Clark, 1997), which suggests that the two may function and develop in different ways. For example, behavioral genetic studies have shown that individual differences in negative affect are related to both environmental and genetic influences, whereas individual differences in positive affect are tied more to environmental than genetic influences (Baker, Cesa, Gatz, & Mellins, 1992). Thus, compared with negative affect, positive affect during the SFP, at least from 3 to 7 months, may be a stronger indicator of underlying developing attachment (i.e., environmental) processes at work. It is also possible that situations that elicit more intense negative reactions than those observed during the SFP would be better suited to detect meaningful links between negative affect and later attachment. In addition, perhaps more specific components of negative affect are particularly reflective of the developing attachment system. For example, fear is believed to play an especially critical role in the development of attachment given that attachment security reflects infants’ ability to rely on parents as a source of comfort (Bowlby, 1969). Future studies should examine how different elements of negative affect (i.e., fear, anger, sadness) may be differentially related to attachment.

In addition to showing a slower rate of increase in positive affect from still-face to reunion, infants who were rated as ambivalent with mothers showed a faster rate of increase in self-comforting from still-face to reunion. Greater levels of self-comforting, particularly during reunion, suggest that infants are making attempts on their own to recover from the distress felt during the previous still-face episode. Similarly, infants who were rated as disorganized with fathers also showed relatively high levels of self-comforting during the reunion episode, especially as they got older. Although self-comforting has been found to be an effective strategy for regulating distress during infancy (Ekas et al., 2011; Stifter & Braungart-Rieker, 1995), a heightened level of self-comforting during contexts in which parents are emotionally available such as the reunion episode is curious. Self-stimulating or repetitive behavior such as rocking or hair-stroking during the reunion episode of the Strange Situation can reflect a disorganized attachment system (Main & Solomon, 1986). Thus, it seems that the context in which self-comforting behaviors are occurring is important to consider.

It should be noted that the Episode effect for self-comforting in infants later rated as ambivalent with mothers was further qualified by an Episode X Parent interaction. In other words, infants who were rated as ambivalent with mothers showed greater increases in self-comforting from still-face to reunion, particularly when they interacted with fathers. This finding suggests that infant-parent attachment does not operate solely at the dyadic level. Rather, interactions and experiences within one dyadic system can permeate other dyadic systems in the family (Cox & Paley, 2003).

Although we found somewhat similarly heightened patterns of self-comforting during the reunion episode for infants developing an ambivalent style of attachment with mothers and a disorganized attachment style with fathers, those who developed an ambivalent attachment with fathers showed greater decreases in self-comforting from the still-face to reunion episodes. Given that fathers whose infants developed an ambivalent attachment with them were not necessarily less sensitive than those who developed a secure relationship, there may be other unmeasured variables that explain these results. In previous research examining infant-father attachment, Brown et al. (2012) found that both quantity of involvement and quality of interaction are important in the prediction of infant-father attachment. When both involvement and quality are low, infants had lower security scores as assessed on the Attachment Behavior Q-set (Waters, 1995). Although types of insecurity cannot be discerned from this attachment measure, it is possible that fathers of future ambivalent infants are less involved with their infants at home. Thus, when there are fewer interactions during the phase of Attachment in the Making, the development of the attachment system may take longer to develop and increased levels of positive affect may reflect an activation of the play system rather than the attachment system. More comprehensive research is needed to further explore the role of father involvement, quality of interaction, styles of attachment, and infants’ affective and behavioral responses with fathers.

Limitations and Future Directions

We would like to acknowledge several additional limitations in this study. First, the present sample involved fairly low-risk families. As a result, we had relatively small group sizes across both insecure and disorganized categories, typical for low-risk samples (e.g., Cyr, Euser, Bakersmans-Kranenburg, & van IJzendoorn, 2010). The generalizability of our study is also limited by its methodology. For example, parental sensitivity was assessed in the laboratory during structured play and reunion interactions that were relatively brief and may have resulted in more attenuated relations between sensitivity and infant SFP responses and attachment. Observing sensitivity during longer, more emotionally intense interactions, and those outside of the SFP paradigm might more fully capture parents’ ability to attend to a range of infant signals. Relatedly, studying sensitivity and infant responses in different contexts would help clarify directionality issues; it may be that parents whose infants are more positive and better regulated have an easier time being sensitive than those whose infants are fussy and difficult to soothe. Third, infants participated in the SFP twice in each visit. Although we counterbalanced the order of parents (mother-first vs. father-first), allowed for breaks between SFPs for the infant to return to a neutral or positive state, and statistically controlled for parent order and any interactions between parent order with all other effects (age, episode, and parent gender), we nonetheless have an imperfect situation. Future studies might consider separating SFPs by at least a day so that infants are more “fresh” during the second SFP.

Conclusions