Abstract

Extensive studies from the past decade have completely revolutionized our understanding about the role of astrocytes in the brain from merely supportive cells to an active role in various physiological functions including synaptic transmission via cross-talk with neurons and neuroprotection via releasing neurotrophic factors. Particularly, numerous studies have reported that astrocytes mediate the neuroprotective effects of 17β-estradiol (E2) and selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) in various clinical and experimental models of neuronal injury. Astrocytes contain two main glutamate transporters, glutamate aspartate transporter (GLAST) and glutamate transporter-1 (GLT-1), that play a key role in preventing excitotoxic neuronal death, a process associated with most neurodegenerative diseases. E2 has shown to increase expression of both GLAST and GLT-1 mRNA and protein and glutamate uptake in astrocytes. Growth factors such as transforming growth factor α (TGF-α) appear to mediate E2-induced enhancement of these transporters. These findings suggest that E2 exerts neuroprotection against excitotoxic neuronal injuries, at least in part, by enhancing astrocytic glutamate transporter levels and function. Therefore, the present review will discuss proposed mechanisms involved in astrocyte-mediated E2 neuroprotection, with a focus on glutamate transporters.

Keywords: Astrocytes, Neuroprotection, Estrogen, Growth factors, TGF-α, GLT-1, GLAST, Glutamate transporters

1. Introduction

Astrocytes are the most abundant, non-neuronal glial cells in the brain and participate actively in normal physiology as well as in acute injury and the pathological process of chronic neurological disorders in the central nervous system (CNS) (Hamby, 2010; Ullian, 2004). The traditional understanding of astrocyte function as merely supporting cells of the brain has completely changed since the discovery that astrocytes are involved in various important functions in the CNS; these include the promotion of glutamate clearance, K+ buffering, antioxidant defense mechanisms and neuronal excitability by coupling with neurons (Allen, 2009; Clarke, 2013; Svendsen 2002; Zhang, 2010). Astrocytes are located in juxtaposition to neurons (which they outnumber 10:1 in some regions of the brain), and act as critical mediators of neuronal survival (Dhandapani, 2007). Besides maintaining neural tissue homeostasis in the brain, the multifunctional roles of astrocytes in the CNS have drawn significant attention to their potential as therapeutic targets for various neurological disorders (Barreto, 2011; Brann, 2007).

In addition to the importance of astrocytes, 17β-estradiol (E2) is now widely accepted as exerting a broad spectrum of actions in the CNS including neuroprotection (Lee, 2001; Wise 2002). This is true for disorders such as multiple sclerosis (MS), schizophrenia, depression, Parkinson’s disease (PD), Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Huntington’s disease (HD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and acute ischemic stroke [reviewed in (Behl 2002; Garcia-Segura, 2001; Green, 2000)]. Moreover, a growing body of evidence suggests that astrocytes are a major cellular target for this E2-induced neuroprotection (Azcoitia, 2010; Dhandapani and Brann 2007; Sortino, 2005). Although the exact mechanism(s) involved in astrocyte-mediated E2 neuroprotection remain to be established, E2 increases the expression and function of the glutamate transporters in astrocytes, GLAST and GLT-1 (Lee, 2012b; Lee, 2009a). Since astrocytic glutamate transporters maintain optimal levels of glutamate in synaptic clefts, which prevents excitotoxic neuronal death, E2-induced enhancement of these transporters may be a crucial step leading to E2-induced neuroprotection. The fact that GLAST and GLT-1 do not contain an estrogen response element (ERE) in their promoters suggests that E2-induced upregulation of GLAST and GLT-1 is an indirect effect, mediated via activation of other cellular signaling pathways. Studies have shown that growth factors such as TGF-α and TGF-β are vital to this E2 action on glutamate transporters (Lee et al., 2012b; Lee et al., 2009a). Thus, the goal of this review is to shed light on the role of astrocyte-derived growth factors in E2 neuroprotection with a particular focus on mechanisms involved in E2-induced upregulation of astrocytic glutamate transporters, GLAST and GLT-1.

2. Role of astrocytes in E2 neuroprotection

It is well-documented that E2 promotes neuronal survival {Sudo, 1997 #156} and offers neuroprotection against various stimuli including iron {Vedder, 1999 #157}, glutamate {Singer, 1996 #158}, kainate {Regan, 1997 #160} and H2O2 {Bonnefont, 1998 #159} in neurons. However, it should be emphasized that astrocytes also play a critical role in mediating E2-induced neuroprotection as E2 is capable of exerting neuroprotection against a neuronal toxic insult in the presence of astrocytes under condition in which it is unable to protect neurons in the absence of astrocytes {Dhandapani, 2002 #10;Park, 2001 #11;Platania, 2005 #12}. The most remarkable evidence for the role of astrocytes in E2-induced neuroprotection is a study by the Sofroniew group, revealing that E2 was unable to protect neurons against neuronal injuries in a model of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE, an animal model of MS) when ER-α was genetically knocked out in astrocytes, while it still exerted neuroprotection when neuronal ER-α was ablated {Spence, 2013 #115}. On the other hand, several studies have reported that neuronal ER-α mediated E2 neuroprotection against middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) in mice {Elzer, 2010 #161}, glutamate neurotoxicity in hippocampal neurons {Gingerich, 2010 #44;Zhao, 2007 #39}. These results indicate that astrocytes might not be exclusively mediating E2-induced neuroprotection, but ample evidence reveals that astrocytes play a major role in this process (reviewed in {Dhandapani, 2007 #2; Mahesh, 2006 #234}.

Astrocytes express all estrogen receptor (ER) subtypes including classical ER-α and ER-β as well as the G protein-coupled ER, GPR30 (Garcia-Segura, 1999; Kuo, 2010; Pawlak, 2005b). Among several proposed mechanisms for E2 neuroprotection involving astrocytes, an anti-inflammatory action in astrocytes appears to be critical to achieve E2-induced neuroprotection (Spence, 2011). Thus, E2 exerts neuroprotection against EAE in astrocytes by decreasing chemokine CCL2 and CCL7 levels (Spence et al., 2013). Since neuroinflammation is associated with many neurodegenerative diseases including MS, an E2-induced anti-inflammatory effect in astrocytes may likely contribute to E2 effects on neuroprotection as a whole (Vegeto, 2008). It also appears that inflammation is involved in the impairment of astrocytic glutamate transporters in neuropathological processes since proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin-1β (IL-1β) also reduce the glutamate transporter GLT-1 in astrocytes (Sama, 2008; Sitcheran, 2005; Su, 2003). Even though the exact mechanism involved in E2-induced enhancement of glutamate transporters in astrocytes remains to be established, is it clear that this pathway needs to be vigorously pursued, as it may yield therapeutic strategies for neurological disorders associated with excitotoxic neuronal injuries.

3. Role of astrocyte-derived growth factors in E2 neuroprotection

It has been well documented that E2 action in astrocytes leads to the synthesis and release of various growth factors including nerve growth factor (NGF), insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), transforming growth factors (TGF)-α and TGF-β, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF); all of these have been shown to exert neuroprotection (Buchanan, 2000; Duenas, 1994; Flores, 1999).

E2 increases NGF mRNA and protein levels in primary astrocytes (Xu, 2013) and exerts synergistic neuroprotective effects with NGF against apoptosis (Gollapudi, 1999). E2 also increases BDNF mRNA and protein expression in astrocytes and exerts neuroprotection via BDNF (Sohrabji, 2006; Xu et al., 2013). Moreover, multiple in vivo studies have demonstrated that BDNF exerts neuroprotection against ischemic and traumatic brain injury (Beck, 1994; Kazanis, 2004; Yamashita, 1997). E2 also increases expression and secretion of GDNF in astrocytes (Xu et al., 2013), and GDNF protects NMDA-induced neuronal cell death by attenuating calcium influx and activation of the ERK pathway (Nicole, 2001). Another study has shown that E2 increases the production and release of GDNF in astrocytes and rescues spinal motoneurons from AMPA-induced excitotoxicity (Platania et al., 2005). IGF-1 signaling also has been reported to play a critical role in mediating E2 neuroprotection via astrocytes. E2 and IGF-1 receptors are often co-localized in the same cells and promote the survival of the same groups of neurons and stimulate adult neurogenesis (Mendez, 2005). E2 also exerts neuroprotective effect against ischemia by activation of GPR30, which is linked to transactivation of the IGF-1 receptor (Lebesgue, 2009). E2 increases expression of bFGF in astrocytes (Galbiati, 2002), and bFGF is known to induce neuroprotection against ischemia and glutamate-induced excitotoxic neuronal cell death (Kirschner, 1995; Nozaki, 1993).

TGF-β is also one of the key growth factors that is induced by E2 and released from astrocytes to exert neuroprotection against various neuronal toxic insults (Dhandapani, 2003a; Dhandapani and Brann 2002; Dhandapani and Brann 2007; Sortino, 2004). Activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway is required for E2-induced TGF-β release from astrocytes (Dhandapani, 2005), while c-Jun-AP-1 signaling is involved in TGF-β-induced neuroprotection (Dhandapani, 2003b). We have reported that E2 and tamoxifen significantly increase the expression of TGF-β1 mRNA in rat primary astrocytes (Lee et al., 2009a). It appears that TGF-β1 mediates E2-induced upregulation of GLAST mRNA and protein levels and attenuates the manganese (Mn)-induced reduction of GLAST expression. TGF-β appears to exert multiple neuroprotection mechanisms including anti-apoptotic and anti-inflammatory actions that protect against excitotoxicity and neuronal regeneration (Dobolyi, 2012). Moreover, the levels of TGF-β are increased following brain ischemia, traumatic injury, MS, AD, PD and viral encephalomyelitis in order to induce neuroprotection [reviewed in (Dobolyi et al., 2012)].

E2 has been shown to increase TGF-α mRNA and protein levels in hypothalamic astrocytes (Ma, 1994), and astrocytes are considered to be the main neural cell type to mediate TGF-α-induced neuroprotection (Junier 2000; White, 2011). We have reported that both E2 and tamoxifen, a SERM, upregulated TGF-α mRNA and protein levels in rat primary astrocytes (Lee et al., 2012b). While tamoxifen exerts an antagonistic effect in breast tissue (Jordan 2006), multiple studies have reported its agonist actions in brain tissue (Kimelberg, 2000; Osuka, 2001). As an example, we found that tamoxifen exerts an agonist effect on glutamate transporters in astrocytes, by increasing TGF-α and GLT-1 expression (Lee et al., 2012b). Since long-term treatment with E2 can induce adverse peripheral effects (such as uterine and breast cancer), development of neuroSERMs that exert brain-specific agonist effects, while exerting antagonistic activities in peripheral tissues, would be ideal to treat neurodegenerative diseases (Littleton-Kearney, 2002).

4. Molecular mechanisms of E2/SERMs neuroprotection

The ER-dependent molecular mechanisms for E2/SERMs-induced neuroprotection could be common in all neural cell types and may be broadly categorized into two different groups; (i) genomic pathways mediated by the activation of nuclear estrogen receptors (ERs), and (ii) non-genomic pathways involving activation of cellular signaling pathways.

4.1. Genomic pathways mediated by ER-α and β

ER-α and -β are widely expressed throughout the brain where they are localized to neurons and glial cells. ER-mediated gene regulation involves either direct binding of ER dimers to ERE sequences in the target gene DNA, or indirect binding of ER with other transcription factors through protein-protein interactions (Marino, 2006). The neuroprotective action of E2 via a genomic pathway was demonstrated by showing that in vivo, a 24 h pre-treatment period was required to achieve protection of E2 against MCAO (Dubal, 1998). In support of this notion, treatment with the nonselective ER antagonist, ICI 182 780, increased the infarct size in female mice following MCAO (Sawada, 2000). To date the majority of studies from ER subtype-specific knockout mouse models have found that ER-α is more critical than ER-β in inducing neuroprotection (Simpkins, 2012; Spence et al., 2013; Zhang, 2011). Therefore, E2 was unable to reduce MCAO-induced neuronal injury in ER-α knockout mice, but effectively reduced neuronal injury in ER-β knockout mice, indicating that ER-α plays a more important role than ER-β does in E2 neuroprotection (Dubal, 2001). The importance of ER-α in E2-induced neuroprotection was further bolstered by the observation that only an ER-α agonist, but not an ER-β agonist, was able to reduce infarct size in rat MCAO models; further there was significant increase of ER-α mRNA expression in the ischemic region in the early development of infarct following MCAO (Dubal, 2006; Farr, 2007). A recent study using an EAE animal model also reported that ER-α, but not ER-β, mediated E2 neuroprotection by anti-inflammatory effects in astrocytes (Spence et al., 2013).

This view (of the sole importance of ER-α in E2 neuroprotection) has been contradicted by the report that there was no additional damage in ER-α knockout mice following MCAO (Sampei, 2000). The importance of ER-β in neuronal survival was also confirmed in ER-β knockout mice by demonstrating morphological abnormalities of neurons as well as severe neuronal deficits in the cortex in these mice (Wang, 2001). In addition, both ER-α and ER-β were able to mediate E2-induced neuroprotection against amyloid β-induced toxicity in the hippocampal-derived neuronal cell line HT22 (Fitzpatrick, 2002). Similarly, selective agonists for either ER-α or ER-β were able to rescue glutamate-induced excitotoxic cell death in hippocampal neurons (Zhao and Brinton 2007; Zhao, 2004). Although further studies are warranted to determine the precise role and individual contributions of ER subtypes to E2-induced neuroprotection, the genomic pathway of the ER certainly plays an important role in E2-mediated neuroprotection.

4.2. Non-genomic signaling pathways

The neuroprotective actions of E2 in the brain also involve activation of intracellular signaling pathways via GPR30 (Gingerich et al., 2010; Liu, 2012). Although GPR30 might be primarily responsible for activation of intracellular signaling pathways, membrane-associated ER-α and ER-β can also mediate these effects (Bao, 2011; Kelly, 2009; Kuo et al., 2010; Marin, 2009). It has been shown that E2-induced activation of ERK pathway is required for E2 neuroprotection against glutamate-induced excitotoxicity in primary cortical neurons (Singer, 1999) and in hippocampal CA1 neurons during global ischemia (Jover-Mengual, 2007). Similarly, activation of PI3K/Akt pathway is crucial in E2-induced neuroprotection against ischemia (Choi, 2004; Jover-Mengual, 2010). The direct interaction of ER-α with the p85α subunit of PI3K may play a part in the non-nuclear E2 signaling mechanism (Simoncini, 2000). Furthermore, E2 activates the ERK-Akt-CREB-BDNF signaling pathway via a non-genomic ER mechanism in hippocampal CA1 region leading to the neuroprotection from ischemic injury and preserving cognitive function following global cerebral ischemia (Yang, 2010). A study from our laboratory has shown that E2 protects against Mn cytotoxicity in cultured astrocytes as well as in neurons via the ERK and PI3K/Akt pathways (Lee, 2009b). SERMs also induce neuroprotection against oxygen-glucose deprivation-induced cell death via GPR30 (Abdelhamid, 2011). Thus, E2 exerts neuroprotection via GPR30 against various toxic insults, including ischemia, glutamate- and oxidative stress-induced cell death in hippocampal and cortical neurons (Gingerich et al., 2010; Lebesgue, 2010; Liu, 2011).

5. Role of astrocytic glutamate transporters in E2 neuroprotection

5.1. Role of glutamate transporters in neuroprotection

Two astrocytic glutamate transporters, GLAST and GLT-1, play an essential role in removing excess glutamate from the synaptic cleft, thereby maintaining glutamate homeostasis and preventing excitotoxic neuronal injury in the CNS (Rosenberg, 1989). An impairment of GLT-1 expression and function has been also observed in ALS (Rothstein, 1995), and indeed, down-regulation of both GLAST and GLT-1 has been associated with various neurodegenerative diseases (Kim, 2011). Since dysfunction of these astrocytic glutamate transporters is associated with various neurological disorders, targeting these transporters for the development of therapeutic strategies to treat various neurodegenerative diseases could be both important and ideal (Kim et al., 2011; Lin, 2012). The beta-lactam antibiotic ceftriaxone and E2 have been reported to increase the expression and function of GLT-1 and GLAST (Lee et al., 2009a; Pawlak, 2005a). The clinical uses of E2 are hampered due to adverse effects from its long-term usage. The results showing that tamoxifen, a SERM, exerts agonist effects in the brain where it enhances glutamate transporter expression and function, could be a promising gateway to the development of optimal neuroSERMs. To achieve this goal, it requires further understanding on the molecular mechanisms involved in tamoxifen-induced enhancement of astrocytic glutamate transporters and neuroprotection. We will briefly update the findings from our laboratory on the mechanisms of E2/tamoxifen action toward enhancing GLAST and GLT-1 expression and function.

5.2. E2 and tamoxifen attenuate Mn-induced impairment of glutamate transporters in astrocytes

Cultured astrocytes from the cortex of AD patients showed reduced glutamate uptake consistent with down-regulation of GLAST and GLT-1 expression; E2 treatment in vitro reversed glutamate uptake along with expression of both GLAST and GLT-1 (Liang, 2002). To study the mechanisms underlying E2-induced attenuation of impaired astrocytic glutamate transporters, we used Mn, an environmental toxin which in high doses induces PD-like pathological features referred to as manganism (Dobson, 2004; Pal, 1999). Thus, it is an excellent model to study mechanisms for neurodegeneration associated with impairment of astrocytic glutamate transporters. Mn has been shown to decrease glutamate uptake along with promoter activity, mRNA and protein levels of GLAST and GLT-1 in astrocytes; E2 or tamoxifen completely block these deleterious effects of Mn (Lee et al., 2012b; Lee et al., 2009a). In addition to PD, Mn neurotoxicity is also associated with several other neurodegenerative disorders including AD, HD and ALS (Bowman, 2011; Lee et al., 2012b), and therefore, the ability of E2 or tamoxifen to afford protection against Mn-impaired glutamate transporters may lead to the development of neuroSERMs to treat multiple neurodegenerative diseases.

5.3. E2 and tamoxifen upregulate GLT-1 via nuclear ER-α and ER-β, as well as G protein-coupled ER GPR30

Astrocytes express ER-α, ER-β and GPR30 (Lee et al., 2012b; Lee et al., 2009b); selective agonists for these ER subtypes (PPT, DPN and G1, respectively) increase GLT-1 protein expression and glutamate uptake activity (Lee et al., 2012b). These results suggest the all three ERs play a role in E2-induced upregulation of GLT-1. Moreover, intracellular signaling pathways such as ERK/MAPK and PI3K/Akt pathways are involved in E2/tamoxifen-induced upregulation of GLT-1 (Lee et al., 2012b). Further study is required to understand, in more detail, the molecular mechanisms by which E2 or tamoxifen increases GLT-1 expression via ER-α and ER-β associated signaling pathways. On the other hand, GPR30 plays a critical role in GLT-1 regulation, as shown by the fact that inhibition of GPR30 with its specific antagonist G15, or siRNA knockdown, abrogates the stimulatory effects of G1, a selective agonist of GPR30, on GLT-1 expression (Lee, 2012a). G1-induced upregulation of GLT-1 is mediated by multiple signaling pathways, including ERK/MAPK, PI3K/Akt, protein kinase A and Src.

5.4. E2 and tamoxifen upregulate GLT-1 via the NF-κB and CREB pathways at the transcriptional level

Extensive studies from our laboratory in recent years have led to the identification of transcription factors that are involved in E2/tamoxifen-induced upregulation of GLT-1 (Karki, 2013). The GLT-1 promoter lacks an ERE, but it contains three NF-κB and one CRE consensus sites. This indicates that the E2 action on enhancing GLT-1 promoter activity is indirect, rather than due to the direct binding of nuclear ER-α/-β to the GLT-1 promoter. Therefore, it appears that these two transcription factors, NF-κB and CREB, play a critical role in E2/tamoxifen-induced enhancement of GLT-1 expression. Previous studies have shown that NF-κB mediates the effects of epidermal growth factor (EGF) and dibutyric cyclic AMP (dbcAMP) on GLT-1 upregulation (Sitcheran et al., 2005; Su et al., 2003). We found that the NF-κB pathway also plays a critical role in E2/tamoxifen-induced enhancement of GLT-1 expression and function (Karki et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2012a). G1 or E2/tamoxifen induced the direct binding of p50 and p65 subunits of NF-κB to the GLT-1 promoter, indicating their critical roles in E2/tamoxifen-induced upregulation of GLT-1. Pharmacological inhibitors of NF-κB abrogated these effects. G1 and tamoxifen also activated the CREB pathway as evidenced by the fact that they induced phosphorylation of CREB and increased CRE reporter activities. G1 and E2/tamoxifen also induced CREB binding to the GLT-1 promoter. In addition, an inhibitor of protein kinase A (upstream activator of CREB) abrogated the G1/tamoxifen-induced GLT-1 expression, supporting the crucial role of these transcription factors in GLT-1 regulation (Karki et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2012a).

5.5. TGF-α as a mediator in E2/tamoxifen-induced upregulation of GLT-1

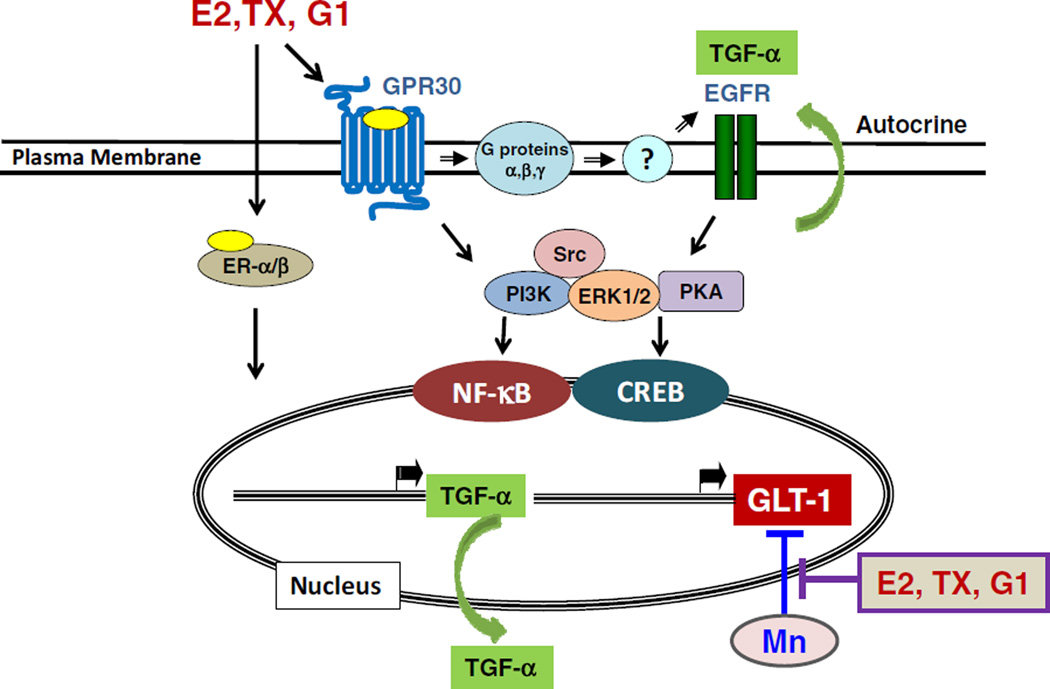

The synthesis and release of growth factors from astrocytes following E2/tamoxifen treatment may represent a major mechanism by which E2 or tamoxifen upregulates GLT-1 and promotes neuroprotection. Our findings that knockdown of TGF-α abrogated G1 and E2/tamoxifen-induced increases in GLT-1 expression in astrocytes, further confirmed the role of TGF-α in E2-induced GLT-1 upregulation (Lee et al., 2012b). Moreover, G1 and E2 increased the phosphorylation epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), the receptor for TGF-α, while inhibition of the EGFR with the pharmacological inhibitor AG-1478 abolished G1 and E2/tamoxifen-induced upregulation of GLT-1 (Karki et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2012a). E2/tamoxifen also increased TGF-α promoter activity, mRNA and protein levels, suggesting a role of TGF-α as a mediator in E2/tamoxifen-induced upregulation of GLT-1 (Karki et al., 2013). The neuroprotective role of TGF-α in neuronal injury was further evidenced by showing that treatment with TGF-α in spinal cord injury exerted neuroprotection by activating EGFR in astrocytes (White et al., 2011). Based on all of our findings, we proposed a model indicating the pathways responsible for E2/tamoxifen-induced upregulation of GLT-1 (Fig. 1). The effects of E2 or tamoxifen are mediated by nuclear ER-α, ER-β and GPR30, which collectively lead to the increased expression of TGF-α which in turn, enhances the GLT-1 expression in astrocytes.

Fig. 1.

Mechanisms of E2/tamoxifen-induced upregulation of GLT-1. E2 and TX activate ER-α, ER-β and GPR30 leading to upregulation of TGF-α. This upregulated TGF-α is released into the extracellular compartment as autocrine mode and activates its receptor EGFR, ultimately resulting in enhancement of GLT-1 expression and function via the NF-κB and CREB pathways. E2, TX and G1 also attenuated Mn-induced down-regulation of GLT-1.

6. Summary

Numerous in vitro studies using cell cultures as well as in vivo animal models have documented the neuroprotective effects of E2 via astrocytes. However, the adverse effects associated with long term use of E2 has hampered its clinical utility, while SERMs has drawn significant attention as possible alternatives for E2 due to their unique pharmacological properties, i.e., exerting tissue-specific agonist or antagonist properties. Moreover, the findings that astrocytes play critical roles in E2/SERMs-induced neuroprotection have placed these non-neuronal cells into an important position for future research related to strategies to treat neurological diseases. The impairment of astrocytic glutamate transporters in various neurodegenerative diseases and the capability of E2/SERMs to enhance the expression and function of these transporters have further bolstered the importance of developing neuroSERMs. Taken together, understanding the molecular mechanisms of E2-induced neuroprotection by enhancing astrocytic glutamate transporters will definitively attribute to development of novel therapeutics to treat multiple neurological disorders.

Highlights.

Estrogen upregulates glutamate transporter GLT-1 expression in astrocytes

Estrogen increases GLT-1 expression via GPR30 using the NF-κB and CREB pathways

TGF-α mediates estrogen-induced upregulation of GLT-1 and GLAST in astrocytes

Tamoxifen, a selective estrogen receptor modulator, enhances GLT-1 expression via NF-κB and CREB

Estrogen and tamoxifen attenuate manganese-induced reduction of GLT-1 expression

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr. Diana Marver for her critical review of the manuscript. The study in our laboratory is supported by the NIGMS grant, NIGMS SC1 089630.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abdelhamid R, Luo J, Vandevrede L, Kundu I, Michalsen B, Litosh VA, Schiefer IT, Gherezghiher T, Yao P, Qin Z, et al. Benzothiophene Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators Provide Neuroprotection by a novel GPR30-dependent Mechanism. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2011;2:256–268. doi: 10.1021/cn100106a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen NJ, Barres BA. Neuroscience: Glia - more than just brain glue. Nature. 2009;457:675–677. doi: 10.1038/457675a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azcoitia I, Santos-Galindo M, Arevalo MA, Garcia-Segura LM. Role of astroglia in the neuroplastic and neuroprotective actions of estradiol. Eur J Neurosci. 2010;32:1995–2002. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao YJ, Li LZ, Li XG, Wang YJ. 17Beta-estradiol differentially protects cortical pericontusional zone from programmed cell death after traumatic cerebral contusion at distinct stages via non-genomic and genomic pathways. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2011;48:185–194. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barreto G, White RE, Ouyang Y, Xu L, Giffard RG. Astrocytes: targets for neuroprotection in stroke. Cent Nerv Syst Agents Med Chem. 2011;11:164–173. doi: 10.2174/187152411796011303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck T, Lindholm D, Castren E, Wree A. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor protects against ischemic cell damage in rat hippocampus. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1994;14:689–692. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1994.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behl C. Oestrogen as a neuroprotective hormone. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:433–442. doi: 10.1038/nrn846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnefont AB, Munoz FJ, Inestrosa NC. Estrogen protects neuronal cells from the cytotoxicity induced by acetylcholinesterase-amyloid complexes. FEBS Lett. 1998;441:220–224. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01552-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman AB, Kwakye GF, Hernandez EH, Aschner M. Role of manganese in neurodegenerative diseases. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2011;25:191–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2011.08.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brann DW, Dhandapani K, Wakade C, Mahesh VB, Khan MM. Neurotrophic and neuroprotective actions of estrogen: basic mechanisms and clinical implications. Steroids. 2007;72:381–405. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan CD, Mahesh VB, Brann DW. Estrogen-astrocyte-luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone signaling: a role for transforming growth factor-beta(1) Biol Reprod. 2000;62:1710–1721. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod62.6.1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi YC, Lee JH, Hong KW, Lee KS. 17 Beta-estradiol prevents focal cerebral ischemic damages via activation of Akt and CREB in association with reduced PTEN phosphorylation in rats. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2004;18:547–557. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2004.00284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke LE, Barres BA. Emerging roles of astrocytes in neural circuit development. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14:311–321. doi: 10.1038/nrn3484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhandapani K, Brann D. Neuroprotective effects of estrogen and tamoxifen in vitro: a facilitative role for glia? Endocrine. 2003a;21:59–66. doi: 10.1385/endo:21:1:59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhandapani KM, Brann DW. Estrogen-astrocyte interactions: implications for neuroprotection. BMC Neurosci. 2002;3:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-3-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhandapani KM, Brann DW. Role of astrocytes in estrogen-mediated neuroprotection. Exp Gerontol. 2007;42:70–75. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2006.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhandapani KM, Hadman M, De Sevilla L, Wade MF, Mahesh VB, Brann DW. Astrocyte protection of neurons: role of transforming growth factor-beta signaling via a c-Jun-AP-1 protective pathway. J Biol Chem. 2003b;278:43329–43339. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305835200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhandapani KM, Wade FM, Mahesh VB, Brann DW. Astrocyte-derived transforming growth factor-{beta} mediates the neuroprotective effects of 17{beta}-estradiol: involvement of nonclassical genomic signaling pathways. Endocrinology. 2005;146:2749–2759. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobolyi A, Vincze C, Pal G, Lovas G. The neuroprotective functions of transforming growth factor Beta proteins. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13:8219–8258. doi: 10.3390/ijms13078219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson AW, Erikson KM, Aschner M. Manganese neurotoxicity. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1012:115–128. doi: 10.1196/annals.1306.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubal DB, Kashon ML, Pettigrew LC, Ren JM, Finklestein SP, Rau SW, Wise PM. Estradiol protects against ischemic injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1998;18:1253–1258. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199811000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubal DB, Rau SW, Shughrue PJ, Zhu H, Yu J, Cashion AB, Suzuki S, Gerhold LM, Bottner MB, Dubal SB, et al. Differential modulation of estrogen receptors (ERs) in ischemic brain injury: a role for ERalpha in estradiol-mediated protection against delayed cell death. Endocrinology. 2006;147:3076–3084. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubal DB, Zhu H, Yu J, Rau SW, Shughrue PJ, Merchenthaler I, Kindy MS, Wise PM. Estrogen receptor alpha, not beta, is a critical link in estradiol-mediated protection against brain injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:1952–1957. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041483198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duenas M, Luquin S, Chowen JA, Torres-Aleman I, Naftolin F, Garcia-Segura LM. Gonadal hormone regulation of insulin-like growth factor-I-like immunoreactivity in hypothalamic astroglia of developing and adult rats. Neuroendocrinology. 1994;59:528–538. doi: 10.1159/000126702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elzer JG, Muhammad S, Wintermantel TM, Regnier-Vigouroux A, Ludwig J, Schutz G, Schwaninger M. Neuronal estrogen receptor-alpha mediates neuroprotection by 17beta-estradiol. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30:935–942. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farr TD, Carswell HV, Gsell W, Macrae IM. Estrogen receptor beta agonist diarylpropiolnitrile (DPN) does not mediate neuroprotection in a rat model of permanent focal ischemia. Brain Res. 2007;1185:275–282. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick JL, Mize AL, Wade CB, Harris JA, Shapiro RA, Dorsa DM. Estrogen-mediated neuroprotection against beta-amyloid toxicity requires expression of estrogen receptor alpha or beta and activation of the MAPK pathway. J Neurochem. 2002;82:674–682. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores C, Salmaso N, Cain S, Rodaros D, Stewart J. Ovariectomy of adult rats leads to increased expression of astrocytic basic fibroblast growth factor in the ventral tegmental area and in dopaminergic projection regions of the entorhinal and prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci. 1999;19:8665–8673. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-19-08665.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galbiati M, Martini L, Melcangi RC. Oestrogens, via transforming growth factor alpha, modulate basic fibroblast growth factor synthesis in hypothalamic astrocytes: in vitro observations. J Neuroendocrinol. 2002;14:829–835. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2002.00852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Segura LM, Azcoitia I, DonCarlos LL. Neuroprotection by estradiol. Prog Neurobiol. 2001;63:29–60. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(00)00025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Segura LM, Naftolin F, Hutchison JB, Azcoitia I, Chowen JA. Role of astroglia in estrogen regulation of synaptic plasticity and brain repair. J Neurobiol. 1999;40:574–584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gingerich S, Kim GL, Chalmers JA, Koletar MM, Wang X, Wang Y, Belsham DD. Estrogen receptor alpha and G-protein coupled receptor 30 mediate the neuroprotective effects of 17beta-estradiol in novel murine hippocampal cell models. Neuroscience. 2010;170:54–66. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.06.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollapudi L, Oblinger MM. Estrogen and NGF synergistically protect terminally differentiated, ERalpha-transfected PC12 cells from apoptosis. J Neurosci Res. 1999;56:471–481. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19990601)56:5<471::AID-JNR3>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green PS, Simpkins JW. Neuroprotective effects of estrogens: potential mechanisms of action. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2000;18:347–358. doi: 10.1016/s0736-5748(00)00017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamby ME, Sofroniew MV. Reactive astrocytes as therapeutic targets for CNS disorders. Neurotherapeutics. 2010;7:494–506. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan VC. Tamoxifen (ICI46,474) as a targeted therapy to treat and prevent breast cancer. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;147(Suppl 1):S269–S276. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jover-Mengual T, Miyawaki T, Latuszek A, Alborch E, Zukin RS, Etgen AM. Acute estradiol protects CA1 neurons from ischemia-induced apoptotic cell death via the PI3K/Akt pathway. Brain Res. 2010;1321:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.01.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jover-Mengual T, Zukin RS, Etgen AM. MAPK signaling is critical to estradiol protection of CA1 neurons in global ischemia. Endocrinology. 2007;148:1131–1143. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junier MP. What role(s) for TGFalpha in the central nervous system? Prog Neurobiol. 2000;62:443–473. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(00)00017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karki P, Webb A, Smith K, Lee K, Son DS, Aschner M, Lee E. CREB and NF-kappaB Mediate the Tamoxifen-induced Upregulation of GLT-1 in Rat Astrocytes. J Biol Chem. 2013 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.483826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazanis I, Giannakopoulou M, Philippidis H, Stylianopoulou F. Alterations in IGF-I, BDNF and NT-3 levels following experimental brain trauma and the effect of IGF-I administration. Exp Neurol. 2004;186:221–234. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly MJ, Ronnekleiv OK. Control of CNS neuronal excitability by estrogens via membrane-initiated signaling. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2009;308:17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Lee SG, Kegelman TP, Su ZZ, Das SK, Dash R, Dasgupta S, Barral PM, Hedvat M, Diaz P, et al. Role of excitatory amino acid transporter-2 (EAAT2) and glutamate in neurodegeneration: opportunities for developing novel therapeutics. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226:2484–2493. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimelberg HK, Feustel PJ, Jin Y, Paquette J, Boulos A, Keller RW, Jr, Tranmer BI. Acute treatment with tamoxifen reduces ischemic damage following middle cerebral artery occlusion. Neuroreport. 2000;11:2675–2679. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200008210-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschner PB, Henshaw R, Weise J, Trubetskoy V, Finklestein S, Schulz JB, Beal MF. Basic fibroblast growth factor protects against excitotoxicity and chemical hypoxia in both neonatal and adult rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1995;15:619–623. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1995.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo J, Hamid N, Bondar G, Prossnitz ER, Micevych P. Membrane estrogen receptors stimulate intracellular calcium release and progesterone synthesis in hypothalamic astrocytes. J Neurosci. 2010;30:12950–12957. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1158-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebesgue D, Chevaleyre V, Zukin RS, Etgen AM. Estradiol rescues neurons from global ischemia-induced cell death: multiple cellular pathways of neuroprotection. Steroids. 2009;74:555–561. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebesgue D, Traub M, De Butte-Smith M, Chen C, Zukin RS, Kelly MJ, Etgen AM. Acute administration of non-classical estrogen receptor agonists attenuates ischemia-induced hippocampal neuron loss in middle-aged female rats. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8642. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E, Sidoryk-Wegrzynowicz M, Wang N, Webb A, Son DS, Lee K, Aschner M. GPR30 regulates glutamate transporter GLT-1 expression in rat primary astrocytes. J Biol Chem. 2012a;287:26817–26828. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.341867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E, Sidoryk-Wegrzynowicz M, Yin Z, Webb A, Son DS, Aschner M. Transforming growth factor-alpha mediates estrogen-induced upregulation of glutamate transporter GLT-1 in rat primary astrocytes. Glia. 2012b;60:1024–1036. doi: 10.1002/glia.22329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee ES, Sidoryk M, Jiang H, Yin Z, Aschner M. Estrogen and tamoxifen reverse manganese-induced glutamate transporter impairment in astrocytes. J Neurochem. 2009a;110:530–544. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06105.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee ES, Yin Z, Milatovic D, Jiang H, Aschner M. Estrogen and tamoxifen protect against Mn-induced toxicity in rat cortical primary cultures of neurons and astrocytes. Toxicol Sci. 2009b;110:156–167. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfp081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, McEwen BS. Neurotrophic and neuroprotective actions of estrogens and their therapeutic implications. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2001;41:569–591. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Z, Valla J, Sefidvash-Hockley S, Rogers J, Li R. Effects of estrogen treatment on glutamate uptake in cultured human astrocytes derived from cortex of Alzheimer's disease patients. J Neurochem. 2002;80:807–814. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2002.00779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CL, Kong Q, Cuny GD, Glicksman MA. Glutamate transporter EAAT2: a new target for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. Future Med Chem. 2012;4:1689–1700. doi: 10.4155/fmc.12.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littleton-Kearney MT, Ostrowski NL, Cox DA, Rossberg MI, Hurn PD. Selective estrogen receptor modulators: tissue actions and potential for CNS protection. CNS Drug Rev. 2002;8:309–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3458.2002.tb00230.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu SB, Han J, Zhang N, Tian Z, Li XB, Zhao MG. Neuroprotective effects of oestrogen against oxidative toxicity through activation of G-protein-coupled receptor 30 receptor. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2011;38:577–585. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2011.05549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu SB, Zhang N, Guo YY, Zhao R, Shi TY, Feng SF, Wang SQ, Yang Q, Li XQ, Wu YM, et al. G-protein-coupled receptor 30 mediates rapid neuroprotective effects of estrogen via depression of NR2B-containing NMDA receptors. J Neurosci. 2012;32:4887–4900. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5828-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma YJ, Berg-von der Emde K, Moholt-Siebert M, Hill DF, Ojeda SR. Region-specific regulation of transforming growth factor alpha (TGF alpha) gene expression in astrocytes of the neuroendocrine brain. J Neurosci. 1994;14:5644–5651. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-09-05644.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahesh VB, Dhandapani KM, Brann DW. Role of astrocytes in reproduction and neuroprotection. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2006;246:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2005.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin R, Diaz M, Alonso R, Sanz A, Arevalo MA, Garcia-Segura LM. Role of estrogen receptor alpha in membrane-initiated signaling in neural cells: interaction with IGF-1 receptor. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2009;114:2–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2008.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino M, Galluzzo P, Ascenzi P. Estrogen signaling multiple pathways to impact gene transcription. Curr Genomics. 2006;7:497–508. doi: 10.2174/138920206779315737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez P, Cardona-Gomez GP, Garcia-Segura LM. Interactions of insulin-like growth factor-I and estrogen in the brain. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2005;567:285–303. doi: 10.1007/0-387-26274-1_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicole O, Ali C, Docagne F, Plawinski L, MacKenzie ET, Vivien D, Buisson A. Neuroprotection mediated by glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor: involvement of a reduction of NMDA-induced calcium influx by the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. J Neurosci. 2001;21:3024–3033. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-09-03024.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozaki K, Finklestein SP, Beal MF. Basic fibroblast growth factor protects against hypoxia-ischemia and NMDA neurotoxicity in neonatal rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1993;13:221–228. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1993.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osuka K, Feustel PJ, Mongin AA, Tranmer BI, Kimelberg HK. Tamoxifen inhibits nitrotyrosine formation after reversible middle cerebral artery occlusion in the rat. J Neurochem. 2001;76:1842–1850. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal PK, Samii A, Calne DB. Manganese neurotoxicity: a review of clinical features, imaging and pathology. Neurotoxicology. 1999;20:227–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park LCH, Zhang H, Gibson GE. Co-culture with astrocytes or microglia protects metabolically impaired neurons. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development. 2001;123:21–27. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(01)00336-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlak J, Brito V, Kuppers E, Beyer C. Regulation of glutamate transporter GLAST and GLT-1 expression in astrocytes by estrogen. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2005a;138:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlak J, Karolczak M, Krust A, Chambon P, Beyer C. Estrogen receptor-alpha is associated with the plasma membrane of astrocytes and coupled to the MAP/Src-kinase pathway. Glia. 2005b;50:270–275. doi: 10.1002/glia.20162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platania P, Seminara G, Aronica E, Troost D, Vincenza Catania M, Angela Sortino M. 17beta-estradiol rescues spinal motoneurons from AMPA-induced toxicity: a role for glial cells. Neurobiol Dis. 2005;20:461–470. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regan RF, Guo Y. Estrogens attenuate neuronal injury due to hemoglobin, chemical hypoxia, and excitatory amino acids in murine cortical cultures. Brain Res. 1997;764:133–140. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00437-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg PA, Aizenman E. Hundred-fold increase in neuronal vulnerability to glutamate toxicity in astrocyte-poor cultures of rat cerebral cortex. Neurosci Lett. 1989;103:162–168. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(89)90569-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein JD, Van Kammen M, Levey AI, Martin LJ, Kuncl RW. Selective loss of glial glutamate transporter GLT-1 in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 1995;38:73–84. doi: 10.1002/ana.410380114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sama MA, Mathis DM, Furman JL, Abdul HM, Artiushin IA, Kraner SD, Norris CM. Interleukin-1beta-dependent signaling between astrocytes and neurons depends critically on astrocytic calcineurin/NFAT activity. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:21953–21964. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800148200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampei K, Goto S, Alkayed NJ, Crain BJ, Korach KS, Traystman RJ, Demas GE, Nelson RJ, Hurn PD. Stroke in estrogen receptor-alpha-deficient mice. Stroke. 2000;31:738–743. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.3.738. discussion 744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawada M, Alkayed NJ, Goto S, Crain BJ, Traystman RJ, Shaivitz A, Nelson RJ, Hurn PD. Estrogen receptor antagonist ICI182,780 exacerbates ischemic injury in female mouse. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2000;20:112–118. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200001000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoncini T, Hafezi-Moghadam A, Brazil DP, Ley K, Chin WW, Liao JK. Interaction of oestrogen receptor with the regulatory subunit of phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase. Nature. 2000;407:538–541. doi: 10.1038/35035131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpkins JW, Singh M, Brock C, Etgen AM. Neuroprotection and estrogen receptors. Neuroendocrinology. 2012;96:119–130. doi: 10.1159/000338409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer CA, Figueroa-Masot XA, Batchelor RH, Dorsa DM. The mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway mediates estrogen neuroprotection after glutamate toxicity in primary cortical neurons. J Neurosci. 1999;19:2455–2463. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-07-02455.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer CA, Rogers KL, Strickland TM, Dorsa DM. Estrogen protects primary cortical neurons from glutamate toxicity. Neurosci Lett. 1996;212:13–16. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12760-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitcheran R, Gupta P, Fisher PB, Baldwin AS. Positive and negative regulation of EAAT2 by NF-kappaB: a role for N-myc in TNFalpha-controlled repression. Embo j. 2005;24:510–520. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohrabji F, Lewis DK. Estrogen-BDNF interactions: implications for neurodegenerative diseases. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2006;27:404–414. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sortino MA, Chisari M, Merlo S, Vancheri C, Caruso M, Nicoletti F, Canonico PL, Copani A. Glia mediates the neuroprotective action of estradiol on beta-amyloid-induced neuronal death. Endocrinology. 2004;145:5080–5086. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sortino MA, Platania P, Chisari M, Merlo S, Copani A, Catania MV. A major role for astrocytes in the neuroprotective effect of estrogen. Drug Development Research. 2005;66:126–135. [Google Scholar]

- Spence RD, Hamby ME, Umeda E, Itoh N, Du S, Wisdom AJ, Cao Y, Bondar G, Lam J, Ao Y, et al. Neuroprotection mediated through estrogen receptor-alpha in astrocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:8867–8872. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103833108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spence RD, Wisdom AJ, Cao Y, Hill HM, Mongerson CR, Stapornkul B, Itoh N, Sofroniew MV, Voskuhl RR. Estrogen mediates neuroprotection and anti-inflammatory effects during EAE through ERalpha signaling on astrocytes but not through ERbeta signaling on astrocytes or neurons. J Neurosci. 2013;33:10924–10933. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0886-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su ZZ, Leszczyniecka M, Kang DC, Sarkar D, Chao W, Volsky DJ, Fisher PB. Insights into glutamate transport regulation in human astrocytes: cloning of the promoter for excitatory amino acid transporter 2 (EAAT2) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:1955–1960. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0136555100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudo S, Wen TC, Desaki J, Matsuda S, Tanaka J, Arai T, Maeda N, Sakanaka M. Beta-estradiol protects hippocampal CA1 neurons against transient forebrain ischemia in gerbil. Neurosci Res. 1997;29:345–354. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(97)00106-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svendsen CN. The amazing astrocyte. Nature. 2002;417:29–32. doi: 10.1038/417029a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullian EM, Christopherson KS, Barres BA. Role for glia in synaptogenesis. Glia. 2004;47:209–216. doi: 10.1002/glia.20082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vedder H, Anthes N, Stumm G, Wurz C, Behl C, Krieg JC. Estrogen hormones reduce lipid peroxidation in cells and tissues of the central nervous system. J Neurochem. 1999;72:2531–2538. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0722531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vegeto E, Benedusi V, Maggi A. Estrogen anti-inflammatory activity in brain: a therapeutic opportunity for menopause and neurodegenerative diseases. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2008;29:507–519. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Andersson S, Warner M, Gustafsson JA. Morphological abnormalities in the brains of estrogen receptor beta knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:2792–2796. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041617498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White RE, Rao M, Gensel JC, McTigue DM, Kaspar BK, Jakeman LB. Transforming growth factor alpha transforms astrocytes to a growth-supportive phenotype after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2011;31:15173–15187. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3441-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise PM. Estrogens and neuroprotection. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2002;13:229–230. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(02)00611-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu SL, Bi CW, Choi RC, Zhu KY, Miernisha A, Dong TT, Tsim KW. Flavonoids induce the synthesis and secretion of neurotrophic factors in cultured rat astrocytes: a signaling response mediated by estrogen receptor. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:127075. doi: 10.1155/2013/127075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita K, Wiessner C, Lindholm D, Thoenen H, Hossmann KA. Post-occlusion treatment with BDNF reduces infarct size in a model of permanent occlusion of the middle cerebral artery in rat. Metab Brain Dis. 1997;12:271–280. doi: 10.1007/BF02674671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang LC, Zhang QG, Zhou CF, Yang F, Zhang YD, Wang RM, Brann DW. Extranuclear estrogen receptors mediate the neuroprotective effects of estrogen in the rat hippocampus. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9851. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang QG, Han D, Wang RM, Dong Y, Yang F, Vadlamudi RK, Brann DW. C terminus of Hsc70-interacting protein (CHIP)-mediated degradation of hippocampal estrogen receptor-alpha and the critical period hypothesis of estrogen neuroprotection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:E617–E624. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104391108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Barres BA. Astrocyte heterogeneity: an underappreciated topic in neurobiology. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2010;20:588–594. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L, Brinton RD. Estrogen receptor alpha and beta differentially regulate intracellular Ca(2+) dynamics leading to ERK phosphorylation and estrogen neuroprotection in hippocampal neurons. Brain Res. 2007;1172:48–59. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.06.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L, Wu TW, Brinton RD. Estrogen receptor subtypes alpha and beta contribute to neuroprotection and increased Bcl-2 expression in primary hippocampal neurons. Brain Res. 2004;1010:22–34. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.02.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]