Abstract

Background

Clinical cluster analysis from the Severe Asthma Research Program (SARP) identified five asthma subphenotypes that represent the severity spectrum of early onset allergic asthma, late onset severe asthma and severe asthma with COPD characteristics. Analysis of induced sputum from a subset of SARP subjects showed four sputum inflammatory cellular patterns. Subjects with concurrent increases in eosinophils (≥2%) and neutrophils (≥40%) had characteristics of very severe asthma.

Objective

To better understand interactions between inflammation and clinical subphenotypes we integrated inflammatory cellular measures and clinical variables in a new cluster analysis.

Methods

Participants in SARP at three clinical sites who underwent sputum induction were included in this analysis (n=423). Fifteen variables including clinical characteristics and blood and sputum inflammatory cell assessments were selected by factor analysis for unsupervised cluster analysis.

Results

Four phenotypic clusters were identified. Cluster A (n=132) and B (n=127) subjects had mild-moderate early onset allergic asthma with paucigranulocytic or eosinophilic sputum inflammatory cell patterns. In contrast, these inflammatory patterns were present in only 7% of Cluster C (n=117) and D (n=47) subjects who had moderate-severe asthma with frequent health care utilization despite treatment with high doses of inhaled or oral corticosteroids, and in Cluster D, reduced lung function. The majority these subjects (>83%) had sputum neutrophilia either alone or with concurrent sputum eosinophilia. Baseline lung function and sputum neutrophils were the most important variables determining cluster assignment.

Conclusion

This multivariate approach identified four asthma subphenotypes representing the severity spectrum from mild-moderate allergic asthma with minimal or eosinophilic predominant sputum inflammation to moderate-severe asthma with neutrophilic predominant or mixed granulocytic inflammation.

Keywords: Severe Asthma Research Program (SARP), severe asthma, sputum, eosinophils, neutrophils, phenotype, cluster analysis

Introduction

Understanding asthma heterogeneity and phenotypic subpopulations are important steps in defining the spectrum of asthma severity. Guidelines have used approaches that rely on descriptive characteristics to classify asthma severity and patient disease risk primarily utilizing current therapeutic requirements and symptom assessment 1–4. Cluster analysis, an unsupervised statistical approach in which individual subjects are grouped based on multiple similarities in clinical or biologic measures without a priori hypotheses, has been used to characterize asthma severity 5–12. While these analyses have described new clinical and pathobiologic asthma phenotypes, none have included multivariate analyses of both clinical and multiple biologic measures in a single cluster analysis on a large number of subjects that have been characterized comprehensively using standardized protocols.

A previous cluster analysis performed on a large cohort of subjects from the NHLBI Severe Asthma Research Program (SARP) included 34 clinical variables derived from comprehensive clinical phenotyping7. This analysis defined clinically relevant asthma subpopulations that include an increasingly severe spectrum of early onset allergic asthma, a late onset severe asthma subpopulation and a severe subgroup with characteristics of COPD despite being nonsmokers. At the time of the clinical cluster analysis, however, the subset of SARP subjects who had assessments of inflammatory cellular measures was limited and thus, these variables were not included in the analysis. Consequentially, the clinical asthma phenotypes described could not be associated with any pathobiologic mechanism. Blood and sputum inflammatory cell counts are now available on a large subset of SARP allowing inclusion of these inflammatory assessments with clinical variables in a new cluster analysis. We hypothesized that integration of pathobiologic measures and subject characteristics in a single multivariate analysis would lead to the identification of groups of subjects who share not only clinical phenotypic traits but also similar pathobiologic mechanisms that may determine these phenotypes.

To accomplish this goal, we analyzed the subjects in SARP with complete clinical characterizations including blood and induced sputum cellular assessments. These subjects represent a broad spectrum of asthma severity but are enriched for severe asthma as defined by the ATS workshop on refractory asthma3. Application of factor analysis and clustering approaches to this group of SARP subjects identified four asthma subphenotypes with different clinical characteristics and inflammatory cell patterns.

Methods

The Severe Asthma Research Program (SARP)

After establishing standard operating procedures, including a review by an independent Data Safety Monitoring Board and approval by the Institutional Review Boards of all sites, study participants underwent comprehensive phenotypic characterization as previously described4. Briefly, two groups of nonsmoking asthma subjects (< 5 pack years of tobacco use) were recruited. Those with severe asthma met the ATS definition of severe asthma3. A second group of subjects with mild to moderate asthma who did not meet these severity criteria were recruited as a comparator group. Thus, the phenotyped SARP subjects included a spectrum of mild to severe asthma. After informed consent, clinical staff administered questionnaires that assessed demographic information, asthma symptoms and medication use, medical history and health care utilization (HCU). Physiologic testing of lung function included “baseline” pre-bronchodilator spirometry with defined withholding of appropriate medications prior to testing, maximal bronchodilation to assess post-bronchodilator lung function (using 6–8 puffs of short-acting beta-agonists) and bronchial hyperresponsiveness to methacholine in subjects with an FEV1>50% predicted prior to inhalational challenge. Atopy was assessed by skin prick testing, measurement of serum total IgE and blood eosinophils. Exhaled nitric oxide was measured using ATS-approved on-line devices at a constant flow rate. Sputum was induced in SARP using the methodology utilized by other NHLBI sponsored asthma networks as previously described 13–15. In brief, an ultrasonic nebulizer with 3% saline was used to induce sputum. Samples were processed by the whole sputum method. All slides were overread by an independent investigator at Wake Forest (>500 cells/slide); slides with > 80% squamous cells were deemed inadequate for analysis. Subjects with an FEV1<45% predicted after albuterol administration did not undergo sputum induction, but a spontaneous sputum sample was collected whenever possible. Only subjects with complete blood and sputum cell counts were used for this analysis.

Cluster Analyses

Orthogonal varimax factor analysis was performed to select variables for cluster analysis. This analysis identified fifteen variables that included baseline and maximal FEV1 % predicted, % eosinophils and neutrophils in blood and sputum, gender, race, age, age of onset, asthma duration, body mass index and the three previously described composite variables [total number of asthma controllers, dose of corticosteroids, health care utilization (HCU) in the past year 7]. Ward’s minimum-variance hierarchical clustering method was performed utilizing an agglomerative (bottom-up) approach and Ward’s linkage (see for additional statistical methods). At each generation of clusters, samples were merged into larger clusters to minimize the within-cluster sum of squares or maximize between-cluster sum of squares. Stepwise discriminant analysis was used to identify the variables most influential in cluster assignment. To compare differences between clusters, ANOVA, Kruskal-Wallis, and chi square tests were used for parametric continuous, non-parametric continuous and categorical variables respectively.

Results

Subject Selection

423 subjects in SARP underwent sputum induction and had complete data for analysis (244 subjects from Wake Forest University, 103 subjects from the University of Wisconsin and 76 subjects from the University of Pittsburgh). A comparison of the demographics and baseline clinical characteristics of this subset of subjects with those of the larger SARP cohort used in the previous cluster analysis is shown in 7. There are no significant differences in age, gender, race, age of asthma onset or disease duration between the not severe and the severe asthma subjects in these two cohorts. Both not severe and severe asthma groups in the current analysis had a slightly higher mean BMI when compared to the larger cohort (p<0.02). Severe asthma subjects in the sputum subset had higher Baseline FEV1 % predicted than severe asthma subjects in the larger cohort (mean 68% vs 62%, p=0.007) due to exclusion of subjects with low lung function from sputum induction. The severe asthma group in the sputum cohort reported less oral corticosteroid use (32% vs 43% subjects, p<0.0001) and fewer hospitalizations for asthma exacerbations in the past year (18% vs 31%, p=0.007). This group was more atopic than the severe asthma group in the larger cohort with 80% of severe subjects with one of more positive skin prick test (80% vs 67%, p=0.009).

Selection of Variables

Factor analysis identified seven factors that accounted for 70% of variance in the analysis (see ). The most influential factors (factors 1–3) were characterized by highly correlated lung function parameters and measures of asthma control (medication use and health care utilization). Inflammatory cell measures correlated in blood (factor 4) or in sputum (Factor 7), however, they did not correlate with each other.

Cluster Analysis

A dendrogram was generated and four groups of subjects were identified (see ). Nearly 90% of the subjects were equally distributed between Clusters A, B and C, while the remaining subjects (11%) were assigned to Cluster D. Subjects classified as severe by the ATS workshop on refractory asthma were found in all four of the inflammatory clusters3. Using discriminant analysis, the two most influential variables for cluster assignment were baseline FEV1 % predicted (F=201, p<0.0001) and % sputum neutrophils (F=151, p<0.0001) (Table I).

TABLE I.

Important Variables in Cluster Analysis by Stepwise Discriminant Analysis

| Step | Variable | Partial R-Square | F value | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Baseline FEV1 % predicted* | 0.59 | 201.22 | < 0.0001 |

| 2 | % Sputum neutrophils | 0.52 | 151.58 | < 0.0001 |

| 3 | Current Age (years) | 0.16 | 27.01 | < 0.0001 |

| 4 | Maximal FEV1 % predicted† | 0.07 | 9.75 | < 0.0001 |

| 5 | Asthma Duration (years) | 0.03 | 4.36 | 0.005 |

| 6 | % Sputum eosinophils | 0.04 | 5.82 | 0.0007 |

| 7 | Body Mass Index (BMI) | 0.03 | 4.58 | 0.004 |

| 8 | Number of asthma controllers†† | 0.02 | 3.17 | 0.02 |

Pre-bronchodilator values with > 6 hours withhold of bronchodilators.

Post-bronchodilator values after 6–8 puffs of albuterol.

Controllers include leukotriene modifiers, ICS, long-acting beta-agonists (LABA), theophyllines, OCS, omalizumab.

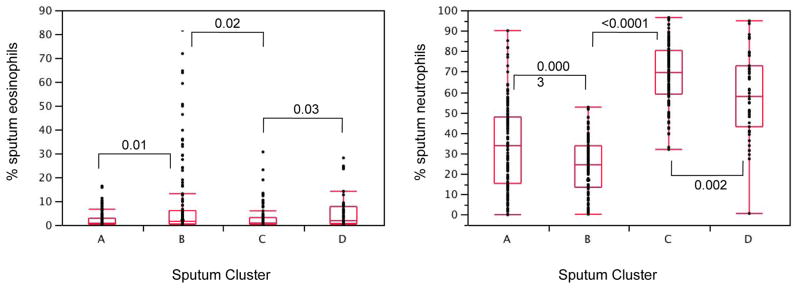

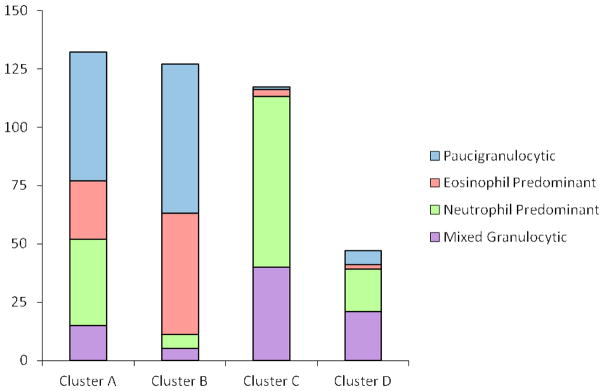

Inflammatory Cell Patterns in the 4 Clusters

While there were differences in % blood eosinophils (p=0.03) and % blood neutrophils (p=0.055) between the clusters (see ), differences in sputum eosinophils and neutrophils were more significant (p=0.001 and p<0.0001 respectively, See Figure 1) and the latter had greater influence on cluster assignment (Table I). To better define patterns of granulocytes in sputum, subjects were classified into four inflammatory subgroups based on whether the % eosinophils (Eos) and % neutrophils (Neu) were above or below the median for these measures based on our prior publications (median Eos=2%, Neu=40%) 13, 15. The most frequent inflammatory pattern in subjects from Clusters A and B was a low or paucigranulocytic sputum cell pattern (< 2% Eos, < 40% Neu) (Figure 2). An eosinophil predominant pattern (≥ 2% Eos, < 40% Neu) was most frequent in Cluster B (41% of subjects). In contrast, the paucigranulocytic and eosinophil predominant patterns collectively are present in only 7% of subjects in Cluster C and D. The majority of subjects in these clusters have elevated sputum neutrophils (97% and 83% of subjects in Clusters C and D respectively) with some subjects showing concurrent elevations in sputum eosinophils. Taken together, there is a marked difference in cellular patterns between Clusters A and B compared to Clusters C and D where a neutrophil predominant pattern (63% and 38% respectively) or a mixed granulocytic pattern (34% and 45% respectively) was present in the majority of subjects.

FIGURE 1.

Sputum inflammatory cells. Shown are box plots of % eosinophils and % neutrophils from sputum specimens. There was a wide range of values for both cell types in all sputum clusters. There are statistically significant differences among the four groups, (p=0.001 for eosinophils, p<0.0001 for neutrophils) with differentiation between clusters in contrast to blood inflammatory cells (see ). P values shown on graph are paired comparisons between two clusters of similar disease severity.

FIGURE 2.

Sputum granulocyte patterns in the four clusters. Subjects were assigned into one of four possible patterns based on % sputum eosinophils (<2% or >=2%) and % sputum neutrophils (<40% or >=40%). All four granulocyte patterns are present in every cluster, but in general, as asthma severity increases (Clusters C and D), sputum neutrophils increase in nearly all subjects and sputum eosinophils persist in a third to half of these subjects despite increasing doses of inhaled and/or oral corticosteroids.

Clinical Characteristics of the 4 Clusters

Cluster A

The youngest subjects with the lowest BMI are in Cluster A, which consists of a greater proportion of white women than in the other clusters (Table II). Two thirds of these subjects had early onset asthma before the age of 12 years and nearly 90% were allergic to common aeroallergens by skin prick testing. All subjects in Cluster A have normal lung function [Baseline FEV1 mean 97%, range 91–105%, Post-bronchodilator FEV1 mean 107%, range 99–113% predicted (25–75% IQR)]. Half of these subjects are treated with inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) and a few (n=26) required higher doses of ICS or oral steroids (OCS) (Table III). HCU was less frequent in this cluster, although 13% of subjects reported treatment with OCS or evaluation in the Emergency Department (ED) for an asthma exacerbation in the past year. One third of the subjects reported recurrent upper and lower respiratory tract infections, but a similar frequency was observed in the other subject clusters (Table III).

TABLE II.

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics of Subjects in Clusters

| Cluster A | Cluster B | Cluster C | Cluster D | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Subjects | 132 | 127 | 117 | 47 | p-value¶ |

| Age at Enrollment (yrs) | 27(10) | 35 (11) | 42 (14) | 50 (10) | <0.0001 |

| Gender (% Female) | 73% | 61% | 62% | 43% | 0.003 |

| Race (% White) | 70% | 58% | 62% | 79% | 0.03 |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | 28 (6) | 31 (9) | 32 (10) | 31 (6) | 0.0001 |

| % with BMI > 30 | 28% | 46% | 50% | 57% | <0.0001 |

| Age of Asthma Onset (yrs) | 12 (13) | 12 (12) | 17 (16) | 22 (18) | 0.001 |

| % with onset ≥ 12 years old | 37% | 41% | 52% | 60% | .01 |

| Asthma Duration (yrs) | 15 (8) | 23 (13) | 24 (14) | 28 (18) | <0.0001 |

| % of Subjects with Severe Asthma | 15% | 24% | 38% | 66% | <0.0001 |

| Baseline Lung Function* | |||||

| FEV1 % predicted | 97 (10) | 73 (13) | 76 (13) | 47 (15) | <0.0001 |

| FVC % predicted | 104 (11) | 87 (12) | 87 (12) | 65 (14) | <0.0001 |

| FEV1/FVC | 0.80 (0.1) | 0.70 (0.1) | 0.71 (0.1) | 0.59 (0.1) | <0.0001 |

| Post-bronchodilator Lung Function† | |||||

| FEV1 % predicted | 107 (10) | 86 (11) | 88 (12) | 61 (14) | <0.0001 |

| FVC % predicted | 108 (12) | 96 (13) | 96 (11) | 79 (15) | <0.0001 |

| Change in % predicted FEV1 | 12 (13) | 20 (20) | 19 (23) | 31 (28) | <0.0001 |

| PC20 Methacholine (mg/ml)ठ| 1.66 (0.7) | 0.89 (0.8) | 1.07 (0.7) | 0.93 (0.5) | 0.02 |

| Atopy Status | |||||

| Total Serum IgE (IU/ml)‡ | 120 (0.6) | 178 (0.6) | 135 (0.6) | 118 (0.7) | 0.09 |

| Number Positive SPT++ | 4.0 (2.9) | 4.8 (3.2) | 4.2 (3.1) | 4.0 (3.5) | 0.14 |

| % with ≥1 Positive SPT++ | 85% | 90% | 83% | 76% | 0.13 |

| Exhaled Nitric Oxide (ppb)‡ | 30 (0.4) | 34 (0.4) | 26 (0.4) | 32 (0.4) | 0.22 |

Numeric data expressed as Mean (SD).

Pre-bronchodilator values with > 6 hours withhold of bronchodilators.

Post-bronchodilator values after 6–8 puffs of albuterol.

Geometric Mean (log 10 SD)

Only Subjects with FEV1 ≥ 55% predicted pre-testing underwent methacholine challenge [n=129, 112, 104, 11 respectively].

SPT = skin prick test.

p-value from ANOVA or Chi-Square analysis between four clusters.

TABLE III.

Medication Use, Health Care Utilization and Co-morbidities

| Cluster A | Cluster B | Cluster C | Cluster D | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Subjects | 132 | 127 | 117 | 47 | p valueठ|

| Corticosteroid Use (%) | <0.0001§ | ||||

| None | 45% | 36% | 37% | 11% | |

| Low-moderate dose ICS | 39% | 37% | 22% | 23% | |

| High dose ICS* | 16% | 26% | 41% | 66% | |

| Oral or Systemic CS* | 4% | 6% | 16% | 26% | |

| ≥ 2 Controllers (%)† | 40% | 43% | 47% | 70% | 0.008§ |

| Health Care Utilization, past year (%) | 0.007§ | ||||

| Emergency Department Visit | 20% | 18% | 24% | 19% | |

| ≥ 3 Oral CS bursts | 13% | 13% | 18% | 28% | |

| Hospitalized for asthma | 5% | 4% | 9% | 17% | |

| Hospitalized in ICU | 2% | 4% | 3% | 2% | |

| Health Care Utilization, ever (%) | |||||

| Emergency Department Visit | 64% | 65% | 79% | 68% | 0.07‡ |

| Hospitalized for asthma | 28% | 41% | 55% | 64% | <0.0001‡ |

| Hospitalized in ICU | 6% | 15% | 22% | 34% | <0.0001‡ |

| History of sinopulmonary infections | |||||

| Pneumonia | 38% | 45% | 44% | 68% | 0.007 |

| Bronchitis | 35% | 31% | 36% | 37% | 0.78 |

| Sinusitis | 41% | 47% | 42% | 53% | 0.44 |

| Associated allergic diseases | |||||

| Aspirin sensitivity | 10% | 9% | 11% | 10% | 0.98 |

| Nasal Polyps | 5% | 11% | 12% | 21% | 0.02 |

| Co-existing Medical problems | |||||

| Gastroesophageal Reflex | 19% | 28% | 37% | 44% | 0.003 |

| Hypertension | 8% | 13% | 28% | 37% | <0.0001 |

| Osteoporosis | 2% | 3% | 6% | 11% | 0.04 |

| Diabetes | 5% | 3% | 9% | 9% | 0.27 |

All data presented as % of subjects.

High dose inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) dose equivalent to ≥ 1000 mcg fluticasone propionate daily; Chronic oral corticosteroids (OCS) ≥ 20 mg daily or other systemic steroids in the past 3 months.

Controllers include leukotriene modifiers, ICS, long-acting beta-agonists (LABA), theophyllines, OCS, omalizumab.

p value from Chi-Square analysis between four clusters, except for

p-value from Chi-Square analysis of ranked ordinal composite variable between 4 clusters.

Cluster B

Subjects in Cluster B are slightly older, almost half are obese (BMI > 30 kg/m2) and one third are African American. Similar to Cluster A, most subjects had early onset allergic asthma, but disease duration is longer since subjects are currently older. Cluster B subjects had mildly decreased baseline lung function (Baseline FEV1 mean 73%, range 64–82%), but following maximal bronchodilation reverse to normal or near normal lung function (Post-bronchodilator FEV1 mean 86%, range 78–95% predicted). The use of corticosteroids was more frequent in this group, one third required treatment with high doses of ICS (26%) and/or OCS (6%). HCU in the past year is similar to Cluster A, but 41% of Cluster B subjects report a prior history of a hospitalization for asthma “ever”; 15% of these in the ICU.

Cluster C

Cluster C subjects are older with the highest BMI (half with BMI > 30 kg/m2) and 38% were classified as having severe asthma (Table II). Half of the subjects reported the onset of asthma after the age of twelve years, although most are atopic by skin prick testing. Lung function was similar to Cluster B (Baseline FEV1 mean 76%, range 66–84%, Post-bronchodilator FEV1 mean 88%, range 79–97% predicted). In contrast to Cluster B, however, 41% of subjects in Cluster C were being treated with high doses of ICS and 16% with concurrent OCS (p=0.02 compared with Cluster B). Despite this therapeutic requirement for high dose corticosteroid treatment, HCU in the past year was not different between Clusters B and C, although historical HCU (“ever”) was higher for Cluster C (p=0.04). While subjects in this cluster reported a similar frequency of sinopulmonary infections, medical co-morbidities such as GERD (37%), hypertension (28%) and diabetes (9%) are more frequent in the older subjects in this cluster compared to Clusters A and B (Table III).

Cluster D

Subjects in the smallest cluster are clinically different from the previous clusters. They are the oldest subjects with a higher proportion of men, the majority of the subjects are white and most are obese with a BMI > 30 kg/m2 (57%) (Table II). Two thirds of the subjects in Cluster D have severe asthma. Onset of asthma after the age of 12 years (later onset asthma) is more common. Despite later onset of disease, measures of atopy (IgE, skin prick testing) were increased in most subjects. Lung function is markedly reduced and although there is reversibility to short-acting beta-agonists, there is persistent airflow obstruction after acute maximal bronchodilation (Baseline FEV1 mean 47%, range 36–57%, Post-bronchodilator FEV1 mean 61%, range 50–71% predicted). This group of subjects reported complex medication regimens, 66% required treatment with high doses of ICS, 26% required daily OCS and 70% of subjects were treated with at least one additional asthma controller medication (Table III). Urgent HCU was frequent, with 17% of subjects hospitalized for an asthma exacerbation in the past year and over two thirds reporting a history of pneumonia in the past. Co-morbidities are frequent in Cluster D subjects (44% GERD, 37% hypertension, 9% diabetes, 11% osteoporosis).

Discussion

The original SARP clinical cluster analysis identified five asthma phenotypes that differed in phenotypic characteristics, medication use, health care utilization, lung function and responsiveness to bronchodilators 7. The current analysis integrates measures of cellular inflammation, clinical characteristics and physiologic variables in a new cluster analysis on 423 subjects who had both blood and induced sputum cell differentials performed at three SARP clinical centers. Using a similar clustering approach we identified four novel asthma subpopulations differentiated by inflammatory cell phenotypic patterns and clinical characteristics.

These four clusters represent the range of asthma severity from mild allergic asthma with normal lung function, limited medication requirements, rare health care utilization and minimal airway inflammation in Cluster A to progressively more severe asthma. Cluster D was characterized by decreased lung function, high medication requirements and frequent health care utilization, medical co-morbidities and complex airway inflammation. Clusters A and D represent the “ends” of this spectrum – they are expectedly very different from each another. In contrast, Clusters B and C represent the mid range of clinical asthma severity with similar levels of lung function and health care utilization, but a more frequent requirement for treatment with higher inhaled or oral corticosteroid regimens in Cluster C subjects to achieve similar levels of asthma control. Although subjects in Cluster B and C may appear clinically “similar” there is a marked shift in airway cellular inflammation from minimal or eosinophil predominant airway inflammation to neutrophil predominant or mixed granulocytic patterns in the latter cluster. Clusters B and C illustrate the importance of integrating clinical disease characteristics and inflammatory cell measures into a single multivariate analysis not only to identify novel subphenotypes but also to understand underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms. It is important that in this multivariate approach no single biomarker or cell type delineated individual cluster groups. Measurements of exhaled nitric oxide and the frequency of atopy (assessed by skin prick testing) did not differ between the four clusters.

Increased sputum eosinophils have been described in all asthma severities and are associated with decreased asthma control and exacerbations in some asthmatics 16. In general, treatment with inhaled corticosteroids decreases sputum eosinophilia and improves asthma control in most subjects 14, 17–19. Severe asthma subjects with persistent sputum eosinophilia despite chronic use of high doses of inhaled or oral corticosteroids may represent a specific eosinophilic subpopulation 13, 15, 18, 20. The increasing frequency of an eosinophilic inflammatory phenotype in Cluster B, a group with fair asthma control [normal lung function and low health care utilization requiring treatment with inhaled corticosteroids (64% subjects)] supports the importance of eosinophils as one pathobiologic biomarker in these mild to moderate asthma subjects. In contrast, the increasing frequency of a mixed granulocytic pattern of airway cellular inflammation despite higher corticosteroid doses in Cluster D subjects suggests complex biologic mechanisms that affect asthma severity. These findings imply that a single biomarker alone is unlikely to be sufficient to accurately subclassify these groups with more severe asthma.

There are numerous reports of “non-eosinophilic” asthma assessed by induced sputum, but it is difficult to ascertain from these studies if these subjects had primarily paucigranulocytic or predominantly neutrophilic airway inflammation. The finding of sputum neutrophilia in asthma patients has led to a number of clinical trials with antibiotics (macrolide), anti-fungals (itraconazole) (ATH 55–57) or with specific anti-neutrophilic compounds such as CXCR2 or anti-TNF immunomodulators targeting innate immunity pathways in addition to traditional allergic or eosinophilic pathobiologic mechanisms 21–26. In the current study, the neutrophilic predominant and mixed granulocytic patterns were most frequent pattern observed in the severe asthma clusters. It is interesting that there was a relatively high frequency of atopy in these clusters suggesting that the presence of atopy does not exclude a neutrophilic phenotype in severe asthma.

Cluster C and D subjects were treated with the highest doses of inhaled or oral corticosteroids and it has been suggested that sputum neutrophils may represent a specific biologic “side effect” of exposure to high doses of corticosteroids 17. Our group has previously published a factor analysis in which corticosteroid use was not associated with either sputum eosinophils or neutrophils suggesting minimal effects of continuous corticosteroids exposure on sputum granulocytes13, 15. Analysis of sputum and blood neutrophil counts in severe asthma subjects in the current study stratified by intensity of corticosteroid exposure also did not show statistical differences in sputum neutrophilia between subjects on high dose inhaled or chronic oral corticosteroids.

It has also been suggested that the presence of sputum neutrophils in asthma is caused by concurrent chronic sinopulmonary infections, especially in severe patients with poor baseline lung function. In the current study, subjects were required to be free from respiratory infectious symptoms for at least four weeks prior to sputum induction and thus, did not have an acute sinopulmonary infection. In addition, there was no difference in subject reported history of a diagnosis of sinusitis or bronchitis among the clusters implying that there was not an increased frequency of airway infections in the more severe clusters (C and D). More cluster D subjects did report a prior history of pneumonia, however, consistent with our previous publication showing a relationship between decreased pulmonary function and serious lung infections in the past 4.

A potential limitation to this analysis is the cross-sectional design of SARP with the collection of one induced sputum sample as part of the comprehensive clinical characterization. Some recent studies have shown a degree of variability in sputum inflammatory cell counts when collected at different times 14, 27–29. It is possible that subjects could change inflammatory cell patterns and this temporal variability could confound interpretation of inflammatory cell pattern heterogeneity. While repeated measures of any clinical variable are invaluable, sputum induction with accurate assessment of inflammatory cells can be difficult to obtain in most health care settings even at tertiary referral health care systems. Thus, it is important to investigate the phenotypic implications of sputum inflammatory cell assessments performed during comprehensive phenotypic characterization on asthma severity and determine the operational aspects of and the cost-effectiveness of sputum induction in clinical settings.

In contrast, spirometry with assessment of bronchodilator response to short-acting beta-agonists can be performed easily in most clinical settings. Interestingly, lung function measures remain the most important variables for cluster assignment in both the current sputum and previous SARP clinical cluster analyses. The current analysis confirms that baseline FEV1 % predicted and bronchodilator reversibility are pivotal clinical variables that aid in the identification of clinical subphenotypes of asthma.

To attempt to utilize the results of this cluster analysis in a clinical setting, the following approach could be considered. The current analysis confirms the importance of spirometry in the “real world” clinic and advocates for the performance of pre- and post-bronchodilator assessments with appropriate withholding of bronchodilator medications before testing to adequately characterize airflow limitation in these patients. In the current study, the Cluster D subjects with the lowest lung function and the most complex medication regimens were characterized by a mixed granulocytic (45%) or a neutrophilic inflammatory cell pattern (38%). These findings suggest that clinic patients with decreased baseline FEV1 % predicted despite treatment with high dose inhaled or oral corticosteroids and a second controller may be considered for sputum induction to guide further therapeutic options in the management of their severe disease.

In conclusion, a multivariate approach utilizing both clinical phenotypes and inflammatory cellular information together identified four sputum Clusters (A to D). These phenotypes represent the severity spectrum from mild-moderate allergic asthma with minimal or eosinophilic predominant sputum inflammation to moderate-severe asthma with complex neutrophilic predominant or mixed granulocytic inflammation. Sputum neutrophils were the second most influential variable in this multivariate analysis suggesting that this cell likely has an important role in the pathobiology of patients with severe asthma, either alone or in conjunction with airways eosinophils. These findings imply that increased sputum neutrophils may be a biomarker of different pathobiologic mechanisms in more severe asthma: a finding that requires further investigation. As new biologic therapies are developed for the management of severe asthma, both neutrophilic and eosinophilic components of airway inflammation should be evaluated and potentially targeted using a personalized medicine paradigm.

Clinical Implications.

In this analysis, severe asthma was associated with sputum neutrophilia with or without eosinophilia suggesting that new biologic therapies for these patients may need to target both inflammatory cell types.

Acknowledgments

Grant support: HL69116, HL69167, HL69174, UL1RR025011

The authors would like to thank Patricia Noel, Ph.D. and Robert Smith, Ph.D. at the National Heart Lung Blood Institute for their support and scientific involvement with the Severe Asthma Research Program for over ten years.

Abbreviations

- ATS

American Thoracic Society

- BMI

Body mass index

- ED

Emergency Department

- FeNO

Fraction of exhaled nitric oxide in ppb

- GERD

Gastroesophageal reflux disease

- ICS

Inhaled corticosteroids

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- LABA

Long-acting beta-agonist

- NHLBI

National Heart Lung Blood Institute

- OCS

Oral Corticosteroids

- SARP

Severe Asthma Research Program

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. Expert Panel Report 3. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; Heart, Lung and Blood Institute; 2007. [accessed on April 15, 2013]. No. 07-4051. Available at http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bateman ED, Hurd SS, Barnes PJ, Bousquet J, Drazen JM, FitzGerald M, et al. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention: GINA executive summary. Eur Respir J. 2008;31:143–78. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00138707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Proceedings of the ATS workshop on refractory asthma: current understanding, recommendations, and unanswered questions. American Thoracic Society. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:2341–51. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.6.ats9-00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moore WC, Bleecker ER, Curran-Everett D, Erzurum SC, Ameredes BT, Bacharier L, et al. Characterization of the severe asthma phenotype by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Severe Asthma Research Program. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:405–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.11.639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haldar P, Pavord ID, Shaw DE, Berry MA, Thomas M, Brightling CE, et al. Cluster analysis and clinical asthma phenotypes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:218–24. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200711-1754OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weatherall M, Travers J, Shirtcliffe PM, Marsh SE, Williams MV, Nowitz MR, et al. Distinct clinical phenotypes of airways disease defined by cluster analysis. European Respiratory Journal. 2009;34:812–8. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00174408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moore WC, Meyers DA, Wenzel SE, Teague WG, Li H, Li X, et al. Identification of asthma phenotypes using cluster analysis in the Severe Asthma Research Program. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:315–23. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200906-0896OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fitzpatrick AM, Teague WG, Meyers DA, Peters SP, Li X, Li H, et al. Heterogeneity of severe asthma in childhood: confirmation by cluster analysis of children in the National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Severe Asthma Research Program. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:382–9. e1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siroux V, Basagaña X, Boudier A, Pin I, Garcia-Aymerich J, Vesin A, et al. Identifying adult asthma phenotypes using a clustering approach. European Respiratory Journal. 2011;38:310–7. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00120810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sutherland ER, Goleva E, King TS, Lehman E, Stevens AD, Jackson LP, et al. Cluster Analysis of Obesity and Asthma Phenotypes. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36631. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brasier AR, Victor S, Boetticher G, Ju H, Lee C, Bleecker ER, et al. Molecular phenotyping of severe asthma using pattern recognition of bronchoalveolar lavage-derived cytokines. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:30–7. e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baines KJ, Simpson JL, Wood LG, Scott RJ, Gibson PG. Transcriptional phenotypes of asthma defined by gene expression profiling of induced sputum samples. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:153–60. 60 e1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hastie AT, Moore WC, Meyers DA, Vestal PL, Li H, Peters SP, et al. Analyses of asthma severity phenotypes and inflammatory proteins in subjects stratified by sputum granulocytes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:1028–36. e13. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGrath KW, Icitovic N, Boushey HA, Lazarus SC, Sutherland ER, Chinchilli VM, et al. A large subgroup of mild-to-moderate asthma is persistently noneosinophilic. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:612–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201109-1640OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hastie A, Moore WC, Li H, Rector BM, Ortega VE, Pascual RM, Peters SP, Meyers DA, Bleecker ER. Biomarker surrogates do not accurately predict sputum eosinophil and neutrophil percentages in asthmatic subjects. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.03.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deykin A, Lazarus SC, Fahy JV, Wechsler ME, Boushey HA, Chinchilli VM, et al. Sputum eosinophil counts predict asthma control after discontinuation of inhaled corticosteroids. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2005;115:720–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.12.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cowan DC, Cowan JO, Palmay R, Williamson A, Taylor DR. Effects of steroid therapy on inflammatory cell subtypes in asthma. Thorax. 2010;65:384–90. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.126722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dente FL, Bacci E, Bartoli ML, Cianchetti S, Costa F, Di Franco A, et al. Effects of oral prednisone on sputum eosinophils and cytokines in patients with severe refractory asthma. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. 2010;104:464–70. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Green RH, Brightling CE, McKenna S, Hargadon B, Parker D, Bradding P, et al. Asthma exacerbations and sputum eosinophil counts: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360:1715–21. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11679-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.ten Brinke A, Zwinderman AH, Sterk PJ, Rabe KF, Bel EH. “Refractory” eosinophilic airway inflammation in severe asthma: effect of parenteral corticosteroids. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:601–5. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200404-440OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simpson JL, Powell H, Boyle MJ, Scott RJ, Gibson PG. Clarithromycin Targets Neutrophilic Airway Inflammation in Refractory Asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:148–55. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200707-1134OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brusselle GG, VanderStichele C, Jordens P, Deman R, Slabbynck H, Ringoet V, et al. Azithromycin for prevention of exacerbations in severe asthma (AZISAST): a multicentre randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Thorax. 2013;68:322–9. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sutherland ER, King TS, Icitovic N, Ameredes BT, Bleecker E, Boushey HA, et al. A trial of clarithromycin for the treatment of suboptimally controlled asthma. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2010;126:747–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Denning DW, O’Driscoll BR, Powell G, Chew F, Atherton GT, Vyas A, et al. Randomized controlled trial of oral antifungal treatment for severe asthma with fungal sensitization: The Fungal Asthma Sensitization Trial (FAST) study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:11–8. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200805-737OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nair P, Gaga M, Zervas E, Alagha K, Hargreave FE, O’Byrne PM, et al. Safety and efficacy of a CXCR2 antagonist in patients with severe asthma and sputum neutrophils: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Clin Exp Allergy. 2012;42:1097–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2012.04014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wenzel SE, Barnes PJ, Bleecker ER, Bousquet J, Busse W, Dahlen SE, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of tumor necrosis factor-alpha blockade in severe persistent asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:549–58. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200809-1512OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Green RH, Pavord I. Stability of inflammatory phenotypes in asthma. Thorax. 2012;67:665–7. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-201657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Al-Samri MT, Benedetti A, Prefontaine D, Olivenstein R, Lemiere C, Nair P, et al. Variability of sputum inflammatory cells in asthmatic patients receiving corticosteroid therapy: A prospective study using multiple samples. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:1161–3. e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hancox RJ, Cowan DC, Aldridge RE, Cowan JO, Palmay R, Williamson A, et al. Asthma phenotypes: Consistency of classification using induced sputum. Respirology. 2012;17:461–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2011.02113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]