Abstract

Background

Aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease (AERD) is an inflammatory condition of the respiratory tract and is characterized by overproduction of leukotrienes (LT) and large numbers of circulating granulocyte-platelet complexes. LT production can be suppressed by prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and the cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA).

Objective

To determine if PGE2-dependent control of LT production by granulocytes is dysregulated in AERD.

Methods

Granulocytes from well-characterized patients with and without AERD were activated ex vivo and subjected to a range of functional and biochemical analyses.

Results

Granulocytes from subjects with AERD generated more LTB4 and cysteinyl LTs than did granulocytes from controls with aspirin-tolerant asthma and controls without asthma. When compared with controls, granulocytes from subjects with AERD had comparable levels of EP2 protein expression and PGE2-mediated cAMP accumulation, yet were resistant to PGE2-mediated suppression of LT generation. Percentages of platelet-adherent neutrophils correlated positively with LTB4 generation and inversely with responsiveness to PGE2-mediated suppression of LTB4. The PKA inhibitor H89 potentiated LTB4 generation by control granulocytes but was inactive in granulocytes from individuals with AERD and had no effect on platelet P-selectin induction. Both tonic PKA activity and levels of PKA catalytic gamma subunit protein were significantly lower in granulocytes from individuals with AERD relative to those from controls.

Conclusions

Impaired granulocyte PKA function in AERD may lead to dysregulated control of 5-lipoxygenase activity by PGE2, whereas adherent platelets lead to increased production of LTs, which contributes to the features of persistent respiratory tract inflammation and LT overproduction.

Keywords: Samter’s triad, aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease, AERD, aspirin triad, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, asthma, leukotriene, protein kinase A, prostaglandin E2, cyclic AMP

Aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease (AERD) is characterized by adult-onset asthma, nasal polyposis, and respiratory reactions caused by drugs that block COX-1.1 AERD accounts for a disproportionate percentage of patients with severe asthma2 and refractory nasal polyposis.3 AERD is noteworthy for intense inflammation of the respiratory mucosa, with large numbers of activated tissue eosinophils, mast cells, monocytes, and neutrophils.4–6 Each of these cells expresses 5-lipoxygenase (5-LO), the enzyme necessary to convert arachidonic acid into leukotrienes (LT), which are potent mediators of inflammation central to AERD. The 5-LO inhibitor zileuton substantially improves control of respiratory symptoms and diminishes the severity of reactions to aspirin,7,8 which confirms the importance of 5-LO products in AERD.

Two classes of LTs result from 5-LO-mediated oxidation of arachidonic acid into the unstable intermediate LTA4: cysteinyl LTs (cysLT) and LTB4; CysLTs form in eosinophils, monocytes, basophils, and mast cells, in which LTA4 is conjugated to reduced glutathione by LTC4 synthase (LTC4S).9,10 The parent cysLT, LTC4, is converted extracellularly to LTD4 and then to the stable metabolite 11,12 CysLTs act at G protein coupled LTE4. receptors to induce bronchoconstriction, vascular leak, and eosinophilia.13–15 Persistently elevated urinary levels of LTE4 are a hallmark of AERD.16 Neutrophils, the most numerous 5-LO–expressing cell in the blood, lack LTC4S but hydrolyze LTA4 to LTB4. The urinary levels of an LTB4 metabolite increase in parallel with LTE4 during reactions to COX-1 inhibitors in AERD,17 which implies that the disease involves a disturbance in the control of 5-LO activity across cell types. Cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) dependent protein kinase A (PKA)18 is the best characterized regulator of 5-LO activity. PKA exists as a complex of 2 catalytic subunits and 2 regulatory subunits. cAMP binds the PKA regulatory subunits, disassociating them from the catalytic subunits, which, in turn, phosphorylate intracellular substrates. Phosphorylation by PKA at serine 523 prevents 5-LO from translocating to the nuclear envelope, which precludes synthesis of LTA4. Accordingly, stimuli that increase PKA activity, including ligands for receptors that couple to stimulatory G proteins, suppress 5-LO activity and LT generation by effector cells.19 Prostaglandin (PG) E2 is among the most potent activators of cAMP and PKA, primarily by signaling through stimulatory G–linked E prostanoid2 (EP2) receptors. Both faulty PGE2 production and impaired expression of EP2 receptors are reported in tissues from patients with AERD.20–23

In inflammation, platelets can adhere to granulocytes via P-selectin (CD62P).24,25 This interaction can amplify cysLT formation, as platelet-derived LTC4S converts excess LTA4 from granulocytes into LTC4.26 We recently reported that the percentages of platelet-adherent neutrophils, eosinophils, and monocytes in the peripheral blood and sinonasal tissues from subjects with AERD far exceeded the percentages found in controls with aspirin-tolerant asthma (ATA) and controls without asthma.27 These percentages correlated with basal urinary levels of LTE4, and adherent platelets accounted for approximately 60% of the LTC4S activity in granulocytes from subjects with AERD. We also found that granulocytes from individuals with AERD generated 2-fold more total 5-LO pathway products than did those from controls, which suggests an overall increase in 5-LO activity. We now demonstrate that granulocytes from individuals with AERD resist suppression of LT generation by PGE2 and EP receptor-selective agonists, despite normal levels of EP receptor expression. Granulocytes from subjects with AERD possess lower levels of PKA activity than do granulocytes from aspirin-tolerant controls. Furthermore, the frequencies of neutrophil-adherent platelets correlate strongly with the production of LTB4 and inversely with ability of PGE2 and EP2 receptors to block LTB4 generation. Impaired granulocyte PKA function likely conspires with adherent platelets to dysregulate PGE2-dependent 5-LO activity in AERD, both of which contribute to the pathophysiology of the disease.

METHODS

Patient characterization

Patients were recruited from the allergy, pulmonary, and otolaryngology clinics at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Boston, Mass). Controls without asthma had no history of asthma or intolerance to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Controls with ATA had physician-diagnosed asthma and had taken a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug within the previous 6 months without an adverse reaction. AERD was diagnosed based on asthma, nasal polyposis, a history of respiratory reaction upon ingestion of a COX inhibitor, and a confirmatory graded oral challenge to aspirin that resulted in sinonasal symptoms and/or a decrease in FEV1 of >15%.28 No subjects smoked. All subjects with AERD were treated with the CysLT1R blocker montelukast during the aspirin challenge, and none were on zileuton. Clinical data, including pulmonary function, the presence of atopy (>2 positive skin prick tests to common inhalant allergens), and use of corticosteroids and long-acting β-agonists are summarized in Table E1 (in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org). The Brigham and Women’s Hospital Institutional Human Subjects Institutional Review Board approved the study, and all the subjects provided written consent.

Flow cytometry

Heparinized whole blood was assayed within 1 hour of collection. For subjects undergoing aspirin challenge, blood was collected before aspirin ingestion. Granulocytes were classified as eosinophils or neutrophils according to their scatter characteristics and expression of CD45 and CCR3. Granulocytes were assessed for the presence of adherent platelets by expression of CD61 and for the formyl peptide (fMLP) receptor 1 (all antibodies from BD Biosciences, San Jose, Calif).

EP2 receptor expression was analyzed on permeabilized whole blood by using a mouse anti-human monoclonal antibody directed against a fusion peptide based on extracellular portions of the human EP2 receptor (Abmart, Shanghai, China) or an IgG1 isotype control. Samples were incubated with a secondary antibody and with an antibody specific for CD45, and were fixed and analyzed as above. To confirm specificity, the EP2 receptor antibody was tested against human embryonic kidney 293 cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va) transfected with human EP2 receptors (see Fig E1 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org).

To assess platelet activation, platelet-rich plasma was incubated with or without 10 μM H89 at 37°C for 30 minutes. Samples were incubated at room temperature for 15 minutes in the absence or presence of PGE2 (0.01–1 μM, Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, Mich), or agonists of the EP1 receptor (DI-004), EP2 receptor (AE1-259-01), EP3 receptor (AE-248), or EP4 receptor (AE-329) (Ono Pharmaceutical Co, Osaka, Japan) at 1 μM and then stimulated for 15 minutes with 100 μM adenosine diphosphate 5′-[β-thio] diphosphate (ADPβS) (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, Mo). Platelet activation was assessed by cytofluorographic analysis of CD62P (BD Biosciences). Data are expressed as a fold change from the percentage CD62P expression induced by ADPβS stimulation alone.

LT and thromboxane measurements

Aliquots of 0.5 × 106 granulocytes were primed with 700 pM granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ), 10 μM cytochalasin-B (Sigma-Aldrich), 1.2 nM TNF-α (eBiosciences, San Diego, Calif), and 0.1 U/mL adenosine deaminase (Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C for 30 minutes18; 10 μM H89 or 5 μM myristoylated 14–22 amide (Milli-pore, Billerica, Mass) was added to some samples during priming to block PKA. Some samples were pretreated with 50 μM forskolin (Sigma-Aldrich); 0.01–1 μM PGE2; or 1 μM EP2, EP3, or EP4 receptor-selective agonists, and then stimulated with 1 μM fMLP for 10 minutes. Reactions were stopped with methanol, and LTB4, cysLTs, and thromboxane B2 levels were measured in the supernatants by enzyme immunoassay (Cayman Chemical).

cAMP measurements

Aliquots of 100 × 106 platelets or 2 × 106 granulocytes were incubated with 200 μM 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C for 10 minutes and treated with 50 μM forskolin, 1 pM iloprost (a selective agonist of the prostacyclin receptor) (Cayman Chemical), 0.01–1 μM PGE2, or 1 μM EP receptor-selective agonists at 37°C for 5 minutes. cAMP levels were analyzed by using enzyme immunoassay (Cayman Chemical).

Western blot analysis

Western blotting of granulocyte protein was performed as described.29 Membranes were probed with polyclonal antibodies against PKA catalytic α subunit (PKACα, Cell Signaling, Danvers, Mass), PKACβ, PKACγ, PKA regulatory Iβ subunit (PKARIβ), PKARIIα (all from Santa Cruz Biotech-nology, Santa Cruz, Calif); PKARIα (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, Mass), or a monoclonal antibody against PKARIIβ (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). PKA subunits were quantified by densitometry and expressed relative to GAPDH.

PKA activity analysis

Basal PKA activity was measured on lysates from aliquots of 0.1 × 106 unfractionated granulocytes by using a PKA kinase activity enzyme immunoassay (Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY).

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as mean (±SEM) unless otherwise stated. Differences in values were analyzed with the t test because all data presented were normally distributed; significance was defined as P <.05, and all tests were 2 tailed. Effect size was measured with the Pearson correlation coefficient.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

The 3 groups of patients were similar in age and sex. The 2 groups of subjects with asthma did not differ in baseline FEV1, the presence of atopy, or use of inhaled corticosteroids (Table E1). The percentage of circulating eosinophils was highest in the subjects with AERD (10.3% ± 8.1%, P <.05 compared with controls without asthma and controls with ATA) (Table E1).

Increased LT generation and impaired suppression of LT production by PGE2 and EP agonists in granulocytes from subjects with AERD

To determine whether LT generation by stimulated granulocytes differed between subjects with AERD and the controls, we measured LT levels in supernatants from primed granulocytes stimulated with1 μM fMLP.18 Becaus eneutrophils activated poorly after elution from an immunomagnetic CD16 selection column, all experiments were done by using unfractionated granulocytes. fMLP-stimulated granulocytes from subjects with AERD generated significantly more LTB4 than did granulocytes from the controls without asthma (P < .05), with intermediate levels of LTB4 generated by granulocytes from controls with ATA (Fig 1, A). Similar trends were seen among the patient groups for the generation of cysLTs (Fig 1, B). Cell surface expression of the fMLP receptor by both neutrophils and eosinophils did not differ significantly between the patient groups (n = 3 for each group, data not shown).

FIG 1.

LT production by fMLP-stimulated granulocytes and suppression by PGE2 and EP agonists. LTB4 (A) and cysLT (B) production by 0.5 × 106 granulocytes stimulated with 1 μM fMLP are shown from controls without asthma (white columns), controls with ATA (gray columns), and subjects with AERD (black columns). Percentage suppression of LTB4 (C) and cysLT (D) production by fMLP-stimulated granulocytes pretreated with the listed agonists is shown for cells from controls without asthma, controls with ATA, and subjects with AERD. Data are expressed as mean (±SEM) (*P < .05; **P < .01).

To determine whether EP receptor-mediated suppression of LT generation differed between granulocytes from subjects with AERD and controls, we studied the effects of pretreatment with PGE2 and EP receptor-specific agonists. We used forskolin as a control to activate adenylyl cyclase independently of EP receptor function. Pretreatment with forskolin, PGE2, and agonists of EP2, EP3, and EP4 receptors all significantly inhibited the generation of LTB4 by granulocytes from ATA and controls without asthma (P < .05 for all conditions, raw data not shown; percentage inhibition is shown in Fig 1, C). Forskolin (P < .01) and the EP3 agonist (P < .05) also significantly suppressed LTB4 generation by granulocytes from subjects with AERD, whereas suppression by PGE2 (P = .052), the EP2 agonist (P = .052), and the EP4 agonist (P =.07) approached significance (raw data not shown). When the percentage suppression of LTB4 generation was compared across groups, the effects of each agonist on the granulocytes from individuals with AERD were significantly less robust than their effects on control subjects (Fig 1, C). Trends for cysLT production were comparable with those for LTB4, except that PGE2 and the EP3 and EP4 agonists tended to potentiate cysLT generation by granulocytes from subjects with AERD (Fig 1, D). Thromboxane A2 generation by granulocytes was not suppressed by PGE2, forskolin, or EP receptor agonists (n = 2, one subject from each control group; data not shown).

Adherent platelets correlate with LTB4 production and PGE2-EP2 resistance in AERD

To determine whether platelet adherence to neutrophils was related to LTB4 generation, we examined the relationship between the platelet-adherent neutrophils in whole blood and the fMLP-induced generation of LTB4 by granulocytes in the same samples. The percentages of platelet-adherent neutrophils in subjects with AERD correlated strongly with the basal fMLP-stimulated LTB4 generation (r = 0.89) (Fig 2, A) and correlated negatively with the percentage suppression of LTB4 release by pretreatment with either PGE2 (r = −0.65) or the EP2 agonist (r = −0.71) (Fig 2, B and C). Correlations were also found in control groups (percentages of platelet-adherent neutrophils vs percentage suppression of LTB4 by PGE2 in controls without asthma and controls with ATA was r = −0.27 and −0.48, respectively, and vs percentage suppression of LTB4 by EP2 was r = 20.64 and 20.76, respectively, not shown).

FIG 2.

Platelet-adherent neutrophils, LTB4 generation, and suppression of 5-LO activity in AERD. A, Percentages of platelet-adherent neutrophils in whole blood from 8 subjects with AERD are plotted against quantity of LTB4 generated by fMLP-stimulated granulocytes from the same individuals. Percentage suppression of fMLP-induced LTB4 by pretreatment with PGE2 (B) or the EP2 receptor-specific agonist (C) plotted against percentages of platelet-adherent neutrophils in the blood of each subject. Effect size (Pearson correlation) is denoted as an r value.

EP2 receptor protein expression and EP receptor-induced cAMP accumulation are not impaired in AERD

Neutrophils consistently expressed EP2 receptor protein (Fig 3, A and B). No differences in EP2 expression were noted among the 3 patient groups. Eosinophils (Fig 3, B, bottom) and platelets (Fig 3, D) in the same samples expressed lower EP2 levels than neutrophils, with no differences among the patient groups. Granulocytes (Fig 3, C) and platelets (Fig 3, E) from all 3 groups of patients accumulated cAMP in response to forskolin, PGE2, and agonists of the EP2 and EP4 receptors, with no differences between subjects with AERD and control subjects. Platelets in the 3 groups responded equivalently to iloprost (Fig 3, E). Neither the EP1 nor the EP3 receptor-selective agonist induced cAMP accumulation in the cells of any patient group. Platelets from all 3 subject groups expressed CD62P in response to ADPβs stimulation (Fig 3, F), with no differences in the magnitude of response. Whereas 1 μM PGE2 tended to potentiate CD62P induction, EP2 and EP4 agonists tended to suppress, as did forskolin and iloprost. Again, there were no differences among the patient groups.

FIG 3.

EP2 protein expression, cAMP accumulation, and inhibition of platelet CD62P. A, Representative flow cytometric histogram of intracellular EP2 is shown for neutrophils from a subject with AERD. Mean intra-cellular EP2 levels of neutrophils and eosinophils (B) and of platelets (D) are shownfor controls without asthma (n = 6), controls with ATA (n = 5), and subjects with AERD (n = 16). Intracellular cAMP accumulation within granulocytes (C) or platelets (E) stimulated with listed agonists is shown. F, Inhibition of ADPβS-stimulated CD62P expression on platelets in platelet-rich plasma is shown. Data are expressed as mean (±SEM). There were no significant differences between patient groups for any comparisons in panels B–F.

PKA inhibition fails to potentiate LTB4 production in AERD

To determine whether control of 5-LO activity by PKA differed among the subject groups, fMLP-induced LTB4 production was measured in the absence or presence of H89. In some experiments we compared the effect of H89 with that of a myristoylated peptide PKA inhibitor (myrPKI, 5 μM) to verify specificity. We activated cells with and without PGE2-EP agonist pretreatment to assess both the effect of inhibiting tonic PKA activity and the effect of PKA inhibition on EP receptor–mediated suppression of LTB4 generation. In the absence of pretreatment, PKA inhibition significantly potentiated LTB4 generation by granulocytes from both control subjects without asthma and those with ATA (Fig 4, A and B). Similar trends were observed for cysLT generation (data not shown). In 3 healthy controls, the effect of myrPKI on fMLP-induced LTB4 generation was similar to that of H89 (from 259 ± 23 pg LTB4/mL to 455 ± 140 pg LTB4/mL with H89, and 378 ± 76 pg LTB4/mL with myrPKI, respectively). H89 also significantly reversed the suppression of LTB4 generation caused by pretreatment with PGE2 and the EP2 receptor agonist in cells from controls, with similar trends for cells pretreated with EP3 and EP4 agonists. In contrast, H89 did not potentiate the generation of LTB4 by granulocytes from subjects with AERD under any condition (Fig 4, C). In addition, the effect of myrPKI on fMLP-induced LTB4 generation also was similar to that of H89 in 3 subjects with AERD (4271 ± 1698 pg LTB4/mL to 4962 ± 1193 pg LTB4/mL with H89 and 4751 pg LTB4/mL ± 1724 pg LTB4/mL with myrPKI, respectively). Treatment of platelets with H89 did not alter the expression of CD62P in response to ADPβS and did not reverse the effects of EP agonists, iloprost, or forskolin in any patient group (data not shown).

FIG 4.

Effect of H89 on LTB4 production from blood granulocytes. The effect of pretreatment of granulocytes with H89 on fMLP-induced LTB4 production is shown for controls without asthma (A) (n = 6), controls with ATA (B) (n = 6), and subjects with AERD (C) (n = 8). Data are expressed as mean (±SEM) (*P < .05; **P < .01).

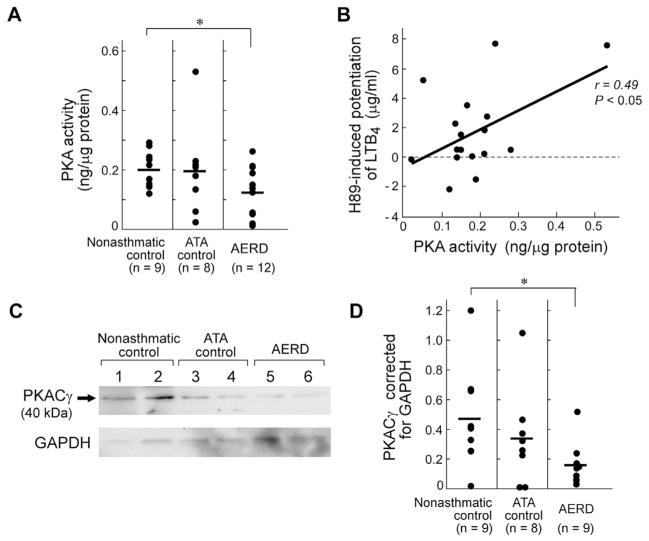

Granulocyte PKA activity and PKACγ subunit expression are reduced in AERD

Freshly isolated granulocytes were analyzed for PKA activity and PKA protein. Baseline granulocyte PKA activity, measured by using enzyme immunoassay, was lower in subjects with AERD than in the controls without asthma (Fig 5, A). The levels of granulocyte PKA activity correlated significantly with the extent of potentiation of LTB4 by treatment with H89 (r = 0.49, P =.05) (Fig 5, B) but not with the total amount of LTB4 generated (data not shown). Granulocytes from all controls without asthma and control subjects with ATA contained PKACγ protein (representative Western blot) (Fig 5, C), with considerable intersubject variability. Corrected PKACγ protein levels were significantly lower in subjects with AERD (Fig 5, D) than in controls. Granulocyte PKACα and PKACβ proteins were low to undetectable in all groups (data not shown). PKARIα and PKARIβ subunits were detected in all samples and their levels did not differ among the groups (data not shown). PKARIIα or PKARIIβ subunits were not detected. Lysates from washed platelets strongly expressed all 3 PKA catalytic subunits as well as PKARIIα and PKARIIβ subunits (data not shown), which verified the efficacy of the antibodies. Removal of platelets by trypsinization did not alter levels of PKA subunits or PKA activity.

FIG 5.

Granulocyte PKA activity and PKACγ subunit expression. A, Basal PKA activity measured by ELISA is shown. B, The net effect of H89 on granulocyte production of LTB4 is shown plotted again the basal PKA activity for each patient. Effect size is denoted as an r value. C, Representative Western blot of granulocytes for PKACγ protein, with GAPDH shown below. Of note, the 2 control subjects with ATA with the lowest PKACγ protein levels of that patient group are the 2 shown on this blot. D, Mean PKACγ protein levels normalized to GAPDH are shown. *P < .05.

DISCUSSION

Persistent respiratory tract inflammation and overproduction of LTs are hallmarks of AERD. The 5-LO products are prominent disease effectors,7 especially during the reactions that occur with administration of nonselective COX inhibitors.8,30 Such reactions are characterized by the marked further overproduction of both cysLTs16 and LTB4.17 Although these findings suggest that AERD involves a fundamental disturbance in the control of 5-LO, no explanatory mechanism had previously been demonstrated. PGE2, an abundant COX product, can suppress 5-LO activity by inducing PKA signaling through EP2 (and possibly other) receptors,18,19 and analysis of results of immunohistochemical studies suggest that EP2 receptor protein expression was reduced on several leukocyte subsets in the sinonasal21 and bronchial mucosa20 from patients with AERD relative to controls with ATA. However, no previous study had examined whether EP receptor-mediated control of 5-LO activity was impaired in cells from patients with AERD.

We activated granulocytes by using fMLP, a physiologic agonist that acts through the formyl peptide G protein coupled receptors expressed by both neutrophils31 and eosinophils.32 Under priming conditions to amplify the fMLP signal,18 granulocytes from all 3 subject groups generated both classes of LTs, with higher levels generated by cells from subjects with AERD (Fig 1, A and B). This difference was not attributable to differences in fMLP receptor expression and is also consistent with our prior study in which levels of total 5-LO products generated by ionophore-stimulated granulocytes from subjects with AERD were approximately 2-fold higher than levels generated by granulocytes from controls with ATA.27 CysLTs can be generated both by eosinophils and by platelet-adherent neutrophils. In our current study, the generation of cysLTs correlated modestly with both the percentages of eosinophils (r = 0.65) and platelet-adherent granulocytes (r = 0.58) in the samples, which supports the thesis that 5-LO activity may be increased across cell types in AERD.

As expected, PGE2 dose dependently suppressed fMLP-induced LTB4 generation in cells from control subjects. However, suppression in the cells from subjects with AERD was markedly blunted (Fig 1, C). Similar trends were observed for cysLTs, although the EP4 agonist and, to a lesser extent, EP3 agonist tended to potentiate cysLT formation in the granulocytes from subjects with AERD (Fig 1, D). The potentiation of cysLTs may be due to different effects of EP receptor signaling in eosinophils (more abundant with subjects with AERD than with controls) versus neutrophils. We anticipated that EP2 receptor signaling would dominate in its ability to block LTB4 formation and that its function would be impaired in AERD. Indeed, the percentage suppression of LTB4 generation by pretreatment with PGE2 and the EP2 agonist correlated significantly (r = 0.73, P = .01), which suggests that the effects of PGE2 reflected, at least in part, signaling through EP2.

Three unexpected findings emerged from these studies. First, LTB4 production in controls was suppressed not only by the EP2 receptor agonist but also by agonists for the EP3 and EP4 receptors at doses at which they are specific for their targets.33 The administration of the EP3 agonist suppressed LT generation in allergen challenged mouse lung34 and also blocked cysLT release in response to aspirin challenge in a mouse model of AERD.35,36 Collectively, these studies and the current result support the capacity of EP3 receptor signaling to suppress LT generation in vitro and in vivo, despite the inability of the EP3 agonist to raise cAMP levels. None of the agonists suppressed thromboxane A2 formation in the same samples, which supports the conclusion that the agonists targeted 5-LO activity rather than arachidonic acid release. Second, the impaired response of the granulocytes from subjects with AERD extended to all of the agonists, including forskolin (Fig 1, C and D). Third, the quantity of LTB4 generated correlated positively with the frequencies of adherent platelets (Fig 2, A), whereas the extent to which PGE2 and the EP2 agonist suppressed LTB4 formation correlated negatively with platelet adherence (Fig 2, B and C). In a mouse model of AERD, antibody-mediated platelet depletion markedly suppressed the production of both LTB4 and cysLTs in response to aspirin challenge, which suggests that platelet adherence contributes substantially to the dysregulation of 5-LO activity.35 We, therefore, focused on whether AERD involved a signaling defect downstream of EP receptors, and, if so, whether the defect involved granulocytes, platelets, or both.

Results of previous immunohistochemical studies suggested that expression of the EP2 receptor protein is specifically reduced on effector cells in bronchial and nasal biopsy specimens from subjects with AERD compared with controls who are aspirin tolerant.20,21 In contrast, we found no differences in EP2 receptor protein expression by neutrophils (Fig 3, B, top), eosinophils (Fig 3, B, bottom), or platelets in peripheral blood from subjects with AERD relative to controls, nor did we find evidence for defective EP2 receptor function (Fig 3, C and D). EP2 receptor expression is upregulated on sputum eosinophils compared with peripheral blood eosinophils37 and can be either upregulated22 or downregu-lated38 by cytokines or ligands for Toll-like receptors. It therefore is possible that the expression of EP2 on leukocytes is modified differently in the tissues of subjects with AERD than in controls once they are recruited. Moreover, responses to the EP4 agonist, forskolin, and, in the case of platelets, iloprost indicated that the associated stimulatory G proteins and adenylyl cyclases were functionally intact. Platelet adhesion onto granulocytes requires expression of platelet CD62P, and, because CD62P expression is controlled by cAMP, we studied CD62P induction as a surrogate for downstream signaling of platelet EP receptors. Platelets from subjects with AERD were not different from those of controls in terms of activation-induced CD62P expression, and suppression of this expression by EP2 and EP4 agonists was unimpaired (Fig 3, F). Thus, we turned our focus to PKA as the next logical post–receptor-signaling step to explain the relatively PGE2-resistant phenotype exhibited by granulocytes from subjects with AERD.

PKA-mediated phosphorylation of 5-LO controls both its catalytic activity39 and its nuclear import.40 We used H89, a PKA inhibitor, to determine whether control of 5-LO function by PKA activity was impaired in granulocytes from subjects with AERD. H89 doubled the production of LTB4 by fMLP-stimulated granulocytes from controls without asthma and controls with ATA. Responses to myrPKA were similar to responses to H89 in all groups. H89 also completely reversed the PGE2- and EP2-mediated suppression of LTB4 (Fig 4, A and B), while also potentiating LTB4 generation in the presence of EP3 and EP4 agonists. Because the stimulation with EP3 receptor agonist did not result in increased cAMP, the reversal of its effect on LTB4 production could reflect either an off-target effect of H89 or could reflect an alternative pathway to PKA activation as reported elsewhere.41 Nevertheless, the cells from subjects with AERD resisted the effects of H89 (Fig 4, C), which suggests that a disturbance of PKA function may impair the ability of PGE2 to suppress granulocyte 5-LO in AERD. Moreover, the finding that H89 did not alter the ADPβS-induced expression of platelet CD62P in any subjects suggested that the functional disturbance in PKA in AERD rested in granulocytes.

Although basal PKA activity varied substantially, it was significantly lower in granulocytes from subjects with AERD (Fig 5, A), including the individuals with the 4 lowest values. PKA activity correlated significantly with the potentiation of LTB4 generation in response to H89 (Fig 5, B). PKACγ was the catalytic subunit expressed most consistently and strongly in granulocytes (Fig 5, C), which contained negligible amounts of PKACα and β subunits. PKACγ was expressed at lower levels in granulocytes from subjects with AERD when corrected for GAPDH (Fig 5, D), including the 4 individuals with the lowest amounts among all analyzed. The small numbers of individuals for whom both PKA activity and PKACγ data were available (n = 8 [2 with AERD]) did not permit an analysis of correlation. PKACγ levels are among several variables, including basal cAMP levels, the cell activation state in vivo, in vivo exposure to PGE2, the strength of association of catalytic and regulatory subunits, and artifacts of handling that could influence PKA activity. It is noteworthy that the expressions of EP2 receptors and PKACα subunits are variably deficient in lung fibroblasts from patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.42 Both defects result in relative resistance to the growth-suppressive effects of PGE2. Regardless of cause, reduced PKA function in granulocytes may have several effects not addressed by our study. These could include failure to induce EP2 expression in the inflamed tissues because the human PTGER2 gene contains consensus binding sites for PKA-dependent transcription factors.

Although blood granulocytes may contribute to the basal production of LTs in AERD,27 resident tissue cells such as mast cells may contribute substantially to the sharp rise of LTs that occur in response to aspirin challenges. Inhaled PGE2 blocks both bronchoconstriction and increases in urinary LTE4 that occur in response to aspirin challenge.43 These bronchoprotective effects of exogenous PGE2 may reflect actions on mast cells or other resident tissue cells that retain PGE2 responsiveness. Indeed, mast cells cultured from peripheral blood progenitors of patients with AERD exhibit robust suppression of IgE-dependent cysLT production in response to preincubation with PGE2.44 It also is possible that the doses used in the in vivo study (70 μM) achieved local concentrations high enough to overcome any deficit in either EP receptor or PKA function. PGE2 normally increases with pulmonary inflammation and limits maximal 5-LO activation in vivo.35 The relative resistance of cells from subjects with AERD to PGE2 identified in our study could compound their capacity for high-level LT production (Fig 1) and promoted LT-related respiratory symptoms at baseline. These symptoms become marked when local PGE2 levels fall below a critical threshold when COX-1 is inhibited by aspirin ingestion. To our knowledge, this is the first study linking platelets to 5-LO function in humans and demonstrating a functional impairment of the PKA system in granulocytes from carefully phenotyped subjects with AERD. An in vivo dose-ranging study would be necessary to assess whether patients with AERD are relatively hyporesponsive to inhaled PGE2.

Platelet adhesion onto granulocytes increases granulocyte integrin avidity and expression45 and permits transcellular synthesis of cysLTs.46 The strong correlation between the percentages of neutrophils with adherent platelets in vivo and the absolute levels of LTB4 generated by fMLP-stimulated granulocytes in vitro (Fig 2, A) in this study may reflect priming of 5-LO by soluble or contact-dependent factors from platelets.47 However, platelet adherence also correlated negatively with the extent of suppression of LTB4 generation by pretreatment with PGE2 and the EP2 receptor agonist (Fig 3, B and C). Interactions between granulocytes and platelets are multifactorial and bilateral, and we cannot exclude the possibility that platelets actively suppress PKA activity in granulocytes. It also is possible that impaired PKA activity dysregulates the release of factors from neutrophils, which, in turn, activate platelet expression of CD62P.48 Tonic PKA activity in granulocytes also controls integrin expression and avidity,49 a parameter that correlates with adherence to platelets in AERD.34 Thus, impaired PKA activity, by simultaneously facilitating adherence of platelets, enhancing integrin expression, and impairing cAMP-mediated control of 5-LO activation, would promote the severe, persistent respiratory tract inflammation and LT overproduction that are characteristic of AERD (see Fig E2 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants AI078908, AI095219, AT002782, AI082369, K23 HL111113, and HL36110; by an American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology Third and Fourth Year Fellow-In-Training Research Award (to T.M.L.), and by generous contributions from the Vinik Family.

Abbreviations used

- 5-LO

5-lipoxygenase

- ADPβS

Adenosine diphosphate 5′-[β-thio]diphosphate

- AERD

Aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease

- ATA

Aspirin-tolerant asthma

- cAMP

Cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- cysLT

Cysteinyl leukotriene

- EP

E prostanoid receptor

- fMLP

Formyl peptide

- LT

Leukotriene

- LTC4S

Leukotriene C4 synthase

- myrPKI

Myristoylated peptide protein kinase A inhibitor

- PG

Prostaglandin

- PKA

Protein kinase A

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: J. A. Boyce has received consultancy fees from ONO Pharmaceuticals. The rest of the authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Szczeklik A, Stevenson DD. Aspirin-induced asthma: advances in pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:913–21. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mascia K, Haselkorn T, Deniz YM, Miller DP, Bleecker ER, Borish L. Aspirin sensitivity and severity of asthma: evidence for irreversible airway obstruction in patients with severe or difficult-to-treat asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:970–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jantti-Alanko S, Holopainen E, Malmberg H. Recurrence of nasal polyps after surgical treatment. Rhinol Suppl. 1989;8:59–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sousa A, Pfister R, Christie PE, Lane SJ, Nasser SM, Schmitz-Schumann M, et al. Enhanced expression of cyclo-oxygenase isoenzyme 2 (COX-2) in asthmatic airways and its cellular distribution in aspirin-sensitive asthma. Thorax. 1997;52:940–5. doi: 10.1136/thx.52.11.940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adamjee J, Suh YJ, Park HS, Choi JH, Penrose JF, Lam BK, et al. Expression of 5-lipoxygenase and cyclooxygenase pathway enzymes in nasal polyps of patients with aspirin-intolerant asthma. J Pathol. 2006;209:392–9. doi: 10.1002/path.1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cowburn AS, Sladek K, Soja J, Adamek L, Nizankowska E, Szczeklik A, et al. Overexpression of leukotriene C4 synthase in bronchial biopsies from patients with aspirin-intolerant asthma. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:834–46. doi: 10.1172/JCI620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dahlen B, Nizankowska E, Szczeklik A, Zetterstrom O, Bochenek G, Kumlin M, et al. Benefits from adding the 5-lipoxygenase inhibitor zileuton to conventional therapy in aspirin-intolerant asthmatics. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:1187–94. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.4.9707089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Israel E, Fischer AR, Rosenberg MA, Lilly CM, Callery JC, Shapiro J, et al. The pivotal role of 5-lipoxygenase products in the reaction of aspirin-sensitive asthmatics to aspirin. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;148:1447–51. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/148.6_Pt_1.1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyce JA, Lam BK, Penrose JF, Friend DS, Parsons S, Owen WF, et al. Expression of LTC4 synthase during the development of eosinophils in vitro from cord blood progenitors. Blood. 1996;88:4338–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weller PF, Lee CW, Foster DW, Corey EJ, Austen KF, Lewis RA. Generation and metabolism of 5-lipoxygenase pathway leukotrienes by human eosinophils: predominant production of leukotriene C4. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983;80:7626–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.24.7626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee CW, Lewis RA, Corey EJ, Austen KF. Conversion of leukotriene D4 to leukotriene E4 by a dipeptidase released from the specific granule of human polymorphonuclear leucocytes. Immunology. 1983;48:27–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carter BZ, Shi ZZ, Barrios R, Lieberman MW. Gamma-glutamyl leukotrienase, a gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase gene family member, is expressed primarily in spleen. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:28277–85. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.43.28277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanaoka Y, Maekawa A, Austen KF. Identification of GPR99 as a potential third cysteinyl leukotriene receptor with a preference for leukotriene E4. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:10967–72. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C113.453704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maekawa A, Kanaoka Y, Xing W, Austen KF. Functional recognition of a distinct receptor preferential for leukotriene E4 in mice lacking the cysteinyl leukotriene 1 and 2 receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:16695–700. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808993105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soter NA, Lewis RA, Corey EJ, Austen KF. Local effects of synthetic leukotrienes (LTC4, LTD4, LTE4, and LTB4) in human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1983;80:115–9. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12531738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Christie PE, Tagari P, Ford-Hutchinson AW, Charlesson S, Chee P, Arm JP, et al. Urinary leukotriene E4 concentrations increase after aspirin challenge in aspirin-sensitive asthmatic subjects. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;143:1025–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/143.5_Pt_1.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mita H, Higashi N, Taniguchi M, Higashi A, Akiyama K. Increase in urinary leukotriene B4 glucuronide concentration in patients with aspirin-intolerant asthma after intravenous aspirin challenge. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:1262–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.02034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flamand N, Surette ME, Picard S, Bourgoin S, Borgeat P. Cyclic AMP-mediated inhibition of 5-lipoxygenase translocation and leukotriene biosynthesis in human neutrophils. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;62:250–6. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feng C, Beller EM, Bagga S, Boyce JA. Human mast cells express multiple EP receptors for prostaglandin E2 that differentially modulate activation responses. Blood. 2006;107:3243–50. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corrigan CJ, Napoli RL, Meng Q, Fang C, Wu H, Tochiki K, et al. Reduced expression of the prostaglandin E2 receptor E-prostanoid 2 on bronchial mucosal leukocytes in patients with aspirin-sensitive asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:1636–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ying S, Meng Q, Scadding G, Parikh A, Corrigan CJ, Lee TH. Aspirin-sensitive rhinosinusitis is associated with reduced E-prostanoid 2 receptor expression on nasal mucosal inflammatory cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:312–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roca-Ferrer J, Garcia-Garcia FJ, Pereda J, Perez-Gonzalez M, Pujols L, Alobid I, et al. Reduced expression of COXs and production of prostaglandin E(2) in patients with nasal polyps with or without aspirin-intolerant asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.01.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoshimura T, Yoshikawa M, Otori N, Haruna S, Moriyama H. Correlation between the prostaglandin D(2)/E(2) ratio in nasal polyps and the recalcitrant pathophysiology of chronic rhinosinusitis associated with bronchial asthma. Allergol Int. 2008;57:429–36. doi: 10.2332/allergolint.o-08-545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maugeri N, Evangelista V, Celardo A, Dell’Elba G, Martelli N, Piccardoni P, et al. Polymorphonuclear leukocyte-platelet interaction: role of P-selectin in throm-boxane B2 and leukotriene C4 cooperative synthesis. Thromb Haemost. 1994;72:450–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cao YJ, Wang YM, Zhang J, Zeng YJ, Liu CF. The effects of antiplatelet agents on platelet-leukocyte aggregations in patients with acute cerebral infarction. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2009;27:233–8. doi: 10.1007/s11239-007-0190-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maclouf J, Antoine C, Henson PM, Murphy RC. Leukotriene C4 formation by transcellular biosynthesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1994;714:143–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb12038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laidlaw TM, Kidder MS, Bhattacharyya N, Xing W, Shen S, Milne GL, et al. Cysteinyl leukotriene overproduction in aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease is driven by platelet-adherent leukocytes. Blood. 2012;119:3790–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-384826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.White AA, Stevenson DD, Simon RA. The blocking effect of essential controller medications during aspirin challenges in patients with aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2005;95:330–5. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61150-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu T, Laidlaw TM, Feng C, Xing W, Shen S, Milne GL, et al. Prostaglandin E2 deficiency uncovers a dominant role for thromboxane A2 in house dust mite-induced allergic pulmonary inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:12692–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207816109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berges-Gimeno MP, Simon RA, Stevenson DD. The effect of leukotriene-modifier drugs on aspirin-induced asthma and rhinitis reactions. Clin Exp Allergy. 2002;32:1491–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2745.2002.01501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Woloszynek JC, Hu Y, Pham CT. Cathepsin G-regulated release of formyl peptide receptor agonists modulate neutrophil effector functions. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:34101–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.394452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Svensson L, Dahlgren C, Wenneras C. The chemoattractant Trp-Lys-Tyr-Met-Val-D-Met activates eosinophils through the formyl peptide receptor and one of its homologues, formyl peptide receptor-like 1. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;72:810–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sugimoto Y, Narumiya S. Prostaglandin E receptors. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:11613–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R600038200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kunikata T, Yamane H, Segi E, Matsuoka T, Sugimoto Y, Tanaka S, et al. Suppression of allergic inflammation by the prostaglandin E receptor subtype EP3. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:524–31. doi: 10.1038/ni1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu T, Laidlaw TM, Katz HR, Boyce JA. Prostaglandin E2 deficiency causes a phenotype of aspirin sensitivity that depends on platelets and cysteinyl leukotrienes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:16987–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1313185110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lundequist A, Nallamshetty SN, Xing W, Feng C, Laidlaw TM, Uematsu S, et al. Prostaglandin E(2) exerts homeostatic regulation of pulmonary vascular remodeling in allergic airway inflammation. J Immunol. 2010;184:433–41. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ying S, O’Connor BJ, Meng Q, Woodman N, Greenaway S, Wong H, et al. Expression of prostaglandin E(2) receptor subtypes on cells in sputum from patients with asthma and controls: effect of allergen inhalational challenge. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:1309–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trudeau J, Hu H, Chibana K, Chu HW, Westcott JY, Wenzel SE. Selective downregulation of prostaglandin E2-related pathways by the Th2 cytokine IL-13. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:1446–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luo M, Jones SM, Phare SM, Coffey MJ, Peters-Golden M, Brock TG. Protein kinase A inhibits leukotriene synthesis by phosphorylation of 5-lipoxygenase on serine 523. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:41512–20. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312568200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luo M, Jones SM, Flamand N, Aronoff DM, Peters-Golden M, Brock TG. Phosphorylation by protein kinase a inhibits nuclear import of 5-lipoxygenase. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:40609–16. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507045200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dulin NO, Niu J, Browning DD, Ye RD, Voyno-Yasenetskaya T. Cyclic AMP-independent activation of protein kinase A by vasoactive peptides. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:20827–30. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100195200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang SK, Wettlaufer SH, Hogaboam CM, Flaherty KR, Martinez FJ, Myers JL, et al. Variable prostaglandin E2 resistance in fibroblasts from patients with usual interstitial pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:66–74. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200706-963OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sestini P, Armetti L, Gambaro G, Pieroni MG, Refini RM, Sala A, et al. Inhaled PGE2 prevents aspirin-induced bronchoconstriction and urinary LTE4 excretion in aspirin-sensitive asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153:572–5. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.2.8564100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang XS, Wu AY, Leung PS, Lau HY. PGE suppresses excessive anti-IgE induced cysteinyl leucotrienes production in mast cells of patients with aspirin exacerbated respiratory disease. Allergy. 2007;62:620–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pitchford SC, Yano H, Lever R, Riffo-Vasquez Y, Ciferri S, Rose MJ, et al. Platelets are essential for leukocyte recruitment in allergic inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112:109–18. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maclouf JA, Murphy RC. Transcellular metabolism of neutrophil-derived leukotriene A4 by human platelets. A potential cellular source of leukotriene C4. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:174–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Murphy RC, Maclouf J, Henson PM. Interaction of platelets and neutrophils in the generation of sulfidopeptide leukotrienes. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1991;314:91–101. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-6024-7_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maugeri N, Evangelista V, Piccardoni P, Dell’Elba G, Celardo A, de Gaetano G, et al. Transcellular metabolism of arachidonic acid: increased platelet thromboxane generation in the presence of activated polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Blood. 1992;80:447–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chilcoat CD, Sharief Y, Jones SL. Tonic protein kinase A activity maintains inactive beta2 integrins in unstimulated neutrophils by reducing myosin light-chain phosphorylation: role of myosin light-chain kinase and Rho kinase. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83:964–71. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0405192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.