Abstract

Older adults with dementia care needs often visit primary care physicians (PCPs), but PCP dementia care limitations are widely documented. This study tested the value of employing a nurse practitioner (NP) with geropsychiatric expertise to augment PCP care for newly and recently diagnosed patients and family caregivers. Twenty-one dyads received the NP intervention; 10 dyads were controls. Outcomes included patient neuropsychiatric symptom and quality of life changes, and caregiver depression, burden, and self-efficacy changes. Intervention acceptability by patients, caregivers, and PCPs was determined. No outcome differences were found; however, the NP intervention was deemed highly satisfactory by all stakeholders. Patients experienced no significant cognitive decline during their 12-month study period, helping explain why outcomes did not change. Given widespread acceptability, future tests of this PCP-enhancing intervention should include patients with more progressive cognitive decline at study entry. NPs with geropsychiatric expertise are ideal interventionists for this rapidly growing target population.

Dementia, an age-associated clinical syndrome characterized by irreversible loss or decline in memory and other cognitive abilities, is a growing health problem due primarily to the steady aging of the population. In 2013, an estimated 5.2 million Americans were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the most common cause of dementia. This figure is projected to reach 7.1 million Americans 65 and older with AD by 2025, and 13.8 million by 2050 (Alzheimer’s Association, 2013). AD accounts for an estimated 60% to 80% of all dementia; therefore, projected figures for the number of Americans with all types of dementia combined are even higher (Alzheimer’s Association, 2013).

Pharmacotherapy is only modestly effective in addressing cognitive and behavioral symptoms of dementia; therefore, active management of dementia involves careful monitoring of symptoms, treatment of comorbidities, medication monitoring, nonpharmacological management strategies, and linkage to community support services (Brodaty & Arasaratnam, 2012; Gitlin, 2012). Moreover, it has long been known that family members caring for individuals with dementia often experience adverse health consequences due to stresses associated with dementia symptoms and uncertainties about how to find information and help to support their care responsibilities (Schulz & Beach, 1999; Schulz, O’Brien, Bookwala, & Fleissner, 1995). Therefore, family members must be included in active management of patients with dementia to maximize health-related outcomes for patients and their family caregivers.

Many studies have demonstrated gaps in care provided by primary care physicians (PCPs) to older adults with dementia in the United States and elsewhere (Callahan, Hendrie, & Tierney, 1995; Fortinsky, 1998; Fortinsky, Leighton, & Wasson, 1995; Koch & Iliffe, 2010). Considering the current U.S. health policy climate focused on improving health care quality while reducing costs to Medicare and other health insurers, primary care enhancements that could effectively address PCP gaps in care for patients with dementia hold great potential for significant cost savings and improved health-related outcomes. A limited number of published trials of nonpharmacological interventions to enhance primary care for people with dementia and/or their family caregivers by augmenting the care provided by PCPs have yielded positive results (Bass, Clark, Looman, McCarthy, & Eckert, 2003; Callahan et al., 2006; Fortinsky, Kulldorff, Kleppinger, & Kenyon-Pesce, 2009; Maslow, 2012; Vickrey et al., 2006). However, none have been successfully sustained beyond the study period or replicated in community-based primary care settings. Tested interventions either required unsustainable linkages between PCPs and community organizations, involved multidisciplinary teams whose services are not presently reimbursable by Medicare or other health insurers, or occurred solely at academic health centers where only a fraction of all patients seek primary care. Therefore, models based on evidence-based care protocols still need to be tested in community-based settings where most primary care is delivered in the United States.

Nurse practitioners (NPs) working collaboratively with PCPs successfully implemented dementia care protocols in two published trials based at academic health centers (Callahan et al., 2006; Vickrey et al., 2006). Although the scope of practice of NPs varies across the United States, all NPs can diagnose, treat, and prescribe medications with physician involvement (Iglehart, 2013). NP services provided in primary care settings, or in home settings when approved by PCPs, are reimbursable by Medicare and many private health insurance plans. Using NPs as primary care–based dementia care specialists is a timely innovation given the growing recognition of roles NPs can play to address primary care workforce shortages (Cassidy, 2012; Donelan, DesRoches, Dittus, & Buerhaus, 2013; Iglehart, 2013) and the growing movement within the nursing profession to teach geropsychiatry core competencies to new and established nurses and NPs due to the growing older population living with dementia and other mental health–related challenges (Buckwalter, 2005; Evans, Beck, & Buckwalter, 2012). Employing NPs as dementia care experts in primary care settings is also consistent with many goals and strategies included in the 2013 update to the National Alzheimer’s Project Act of 2011 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2013) and with collaborative care and comanagement principles that have been successfully tested to treat depression and other geriatric conditions in the primary care setting (Reuben et al., 2013; Unützer, et al, 2002).

Accordingly, the current study implemented and evaluated an evidence-based NP-guided dementia care intervention, where the NP received referrals from and worked collaboratively with three community-based PCP group practice sites. Important differences between this intervention and collaborative care models tested elsewhere are the home-based location of NP-guided dementia care and the equal focus on the patient and family caregiver. Targeted groups were individuals with newly or recently diagnosed AD or other dementia (patients) and their family caregivers. This 12-month dementia care intervention, featuring monthly in-home visits by the NP, used medication management and nonpharmacological treatment protocols developed in a published randomized controlled trial that was tested at an academic health center (Callahan et al., 2006). The intervention tested in this study was called Proactive Primary Dementia Care (PPDC). The following two objectives, as well as major hypotheses for Objective 1, formed the scope of this study:

-

Objective 1: Determine the preliminary efficacy of PPDC on health-related outcomes in patients and their family caregivers.

Patient-specific hypotheses: Patients receiving PPDC will show reduced or more stabilized neuropsychiatric symptoms, as well as improved or more stabilized self-reported quality of life, as compared to control group patients.

Family caregiver-specific hypotheses: Caregivers receiving PPDC will show reduced or more stabilized depressive symptoms and burden, as well as increased or more stabilized self-efficacy for managing dementia, as compared to control group caregivers.

Objective 2: Determine the acceptability of PPDC based on satisfaction expressed by physicians, patients, and caregivers.

METHOD

Design and Setting

A nonequivalent control group design was used. For both intervention and control groups, patient and family caregiver outcome measures were collected via in-person interviews at three time points—immediately after obtaining written consent (baseline); 6 months later; and 12 months after baseline. Primary endpoints were 12 months after baseline, corresponding closely to the end of the PPDC intervention period. All data collected by research interviewers were submitted to the study data manager on precoded forms ready for automated scanning; scanned data were imported into Microsoft® Access files and prepared for analysis by the study data manager. Research interviewers and the study data manager all were trained by the first author (R.H.F.) in the data collection and processing protocols and procedures followed in this study. All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the first author’s institution.

The study was designed as a practice-based research partnership between the investigative team and a large PCP network in a northeastern state in the United States. Three practice sites within this large PCP network agreed to serve as intervention sites by incorporating the NP-guided dementia care intervention into their group practices. Three other practice sites, also part of the same large PCP network, originally agreed to serve as control sites; however, one of these control sites withdrew due to competing clinical initiatives and was replaced with a university-affiliated geriatrics primary care group.

During the PPDC intervention, control group patients and family caregivers received usual care from their PCPs. Control group dyads also received educational pamphlets and brochures published by the national Alzheimer’s Association explaining common dementia-related symptoms and sources of caregiver stress, as well as pamphlets listing locally available community resources. Research interviewers, trained by the first author, distributed and reviewed these educational materials in detail with control group dyads following completion of in-person baseline interviews. Control group dyads were instructed by research interviewers to educate themselves about dementia and to contact community resources as they saw fit. Following the 6-month follow-up interview with control group dyads, research interviewers offered to review these educational materials again, answered questions prompted by the brochures, and replaced brochures if they had been misplaced by control group dyads.

Study Entry Criteria

Patient inclusion criteria were: (a) age 50 or older; (b) living at home; (c) English speaking; (d) willing to participate in study per protocol; and (e) diagnosis of irreversible dementia <12 months prior to the start of the study recruitment period, or newly diagnosed during the recruitment period as evidenced by any of the following International Classification of Diseases, ninth revision (ICD-9; World Health Organization, 1978) codes: arteriosclerotic dementia (290.40–290.43); senile dementia (290.00–290.30); presenile dementia (290.10–290.13); memory loss, mild (310.10); or Alzheimer’s disease (331.00). By selecting patients who had been diagnosed with dementia <12 months prior to study recruitment startup, a reasonable balance was maintained between minimizing the length of time between diagnosis and study entry and maximizing the expected number of patients satisfying all study entry criteria.

Patient exclusion criteria were: (a) Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE; Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975) score <12; (b) dementia due to alcohol abuse or HIV/AIDS; (c) any comorbid illness deemed terminal by PCP; and (d) living in a nursing home or assisted living facility. The required minimum MMSE score was based on findings that patients scoring ≥13 can respond consistently and accurately to questions about their demographic characteristics and their daily care preferences (Feinberg & Whitlatch, 2001; Whitlatch, Feinberg, & Tucke, 2005).

Family caregiver inclusion criteria were: (a) family member or significant other of eligible patient, (b) English speaking, and (c) willing to participate in study per protocol. In most cases, family caregivers deemed eligible by the first criterion were listed as the primary contact in patients’ PCP medical records and routinely accompanied patients to PCP office visits. No exclusion criteria were prespecified for family caregivers.

Participant Recruitment and Consent Procedures

Newly diagnosed patients during the recruitment period and family members accompanying them to office visits were told about the study by PCPs. At this time, patients and caregivers either gave PCPs permission to provide their contact information to research interviewers, or they were given a study flyer with instructions on how to contact a research interviewer to learn more about the study. Patients diagnosed <12 months before the start of the recruitment period were identified through PCP site electronic billing records, and PCPs verified the diagnosis. PCP office staff then sent personalized study invitation letters to these patients and individuals listed in the medical records as primary contacts. Intervention site letters explained the opportunity to participate in a project testing the use of a nurse specially trained in helping patients and families after a dementia diagnosis. Control site letters explained the opportunity to participate in a project seeking to learn how patients and families adjust after a dementia diagnosis and to receive educational materials. Research interviewers trained by the first author screened interested patients and family members by telephone for eligibility; for those eligible, in-home visits for consenting and baseline data collection were scheduled. During in-home visits, patients were evaluated for capacity to provide written consent, adapting procedures developed for other adult populations with potential decisional impairment (Jeste et al., 2007). Consistent with the IRB-approved study protocol, patients found incapable of providing written consent and their family caregivers were excluded and provided educational materials received by control group dyads as described; in these cases, the principal investigator (R.H.F.) sent a letter to the referring PCP explaining that the patient could not provide written consent and could therefore not participate in the study.

Theoretical Basis for the PPDC Intervention

The Progressively Lowered Stress Threshold (PLST, Hall & Buckwalter, 1987) theoretical model was used to frame the PPDC intervention. The PLST model posits that individuals with dementia need environmental conditions modified as they experience progressive cognitive decline so that cues can be more easily processed and are thus less stressful. Symptoms of dementia are clustered into intellectual losses, affective or personality losses, conative or planning losses, and PLST, an array of behaviors that emerge when environmental demands exceed the individual’s ability to cope. Within this framework, six principles of care are proposed to keep stress to a manageable level: (a) maximize safe function by supporting losses in a prosthetic manner; (b) provide unconditional positive regard; (c) use anxiety and avoidance to gauge activity and stimulation levels; (d) teach caregivers to observe and listen to patients; (e) modify environments to support losses and enhance safety; and (f) provide on-going education, support, care, and problem-solving (Gerdner, Buckwalter, & Reed, 2002; Hall & Buckwalter, 1987; Smith, Hall, Gerdner, & Buckwalter, 2006). In this study, these PLST model principles were incorporated into the PPDC protocols that comprised the intervention. The rationale for initiating PPDC as close as possible to the time of diagnosis was that diagnostic disclosure has been found to lead patients and families to begin planning for the future (Bamford et al., 2004); therefore, the time of diagnosis is a teachable moment. The proactive nature of PPDC lies in the use of a NP readily prepared as a provider in the primary care setting at a key point in the dementia journey for patients and families.

Synopsis of the PPDC Intervention

The interventionist NP (E.S.) had prior extensive clinical experience with adult patient populations. Prior to starting work with study patients and family caregivers, this NP received competency-driven training and was deemed certified in geropsychiatry via a guided curriculum supervised by two internationally known academic nurse scholars and researchers. The PPDC intervention was written into a manual by a member (C.D.) of the investigative team with nursing intervention research experience, and the manual was reviewed extensively with the NP interventionist before subject recruitment began. Study patient/family caregiver dyads were scheduled to be seen by the NP in the setting of their choice (all chose in-home visits) for 12 in-person contacts over a 12-month period, including two contacts in the first month, as outlined by the intervention protocol used in the Alzheimer’s Collaborative Care study (Callahan et al., 2006). During the first two contacts, the NP determined how well the dyad adjusted to the news of the dementia diagnosis and explained the types of cognitive and behavioral symptoms that may be expected to develop over time. A complete review of the patient’s current medications and clinical review of systems was conducted, and any discovered medication side effects or potential interactions, or other urgent signs and symptoms, were reported immediately to the referring PCP. The NP did not initiate medication regimens but collaborated with the PCP to determine whether drug therapy might be adjusted. Beginning with the third contact, and at every contact thereafter, the Revised Memory and Behavior Problems Checklist (RMBPC; Teri et al., 1992) was used as a guide to activate specific nonpharmacological protocols developed for the Alzheimer’s Collaborative Care Study (Guerriero Austrom et al., 2004). The RMBPC assesses the frequency of specific problems exhibited by the patient and how they affect the caregiver. Nonpharmacological protocols implemented during the remaining intervention contacts included: (a) stress management; (b) exercises for physical health; (c) communication techniques; (d) legal and financial considerations; (e) depression and anxiety prevention, recognition, and management; (f) repetitive questioning and agitation; (g) mobility management; (h) personal care concerns; and (i) paranoia, delusions, and hallucinations. The NP sent secure electronic updates to referring PCPs after each intervention contact, and if warranted, secure electronic correspondence ensued between the NP and PCP.

To monitor treatment fidelity, selected procedures were used from a model from the National Institutes of Health Behavior Change Consortium (Bellg et al., 2004). Procedures included development and use of an intervention manual with standardized guidelines, completion of a checklist by the NP at every contact to record intervention components delivered, and quarterly conferences between the NP and members of the investigative team.

Measures

Patient Outcome Measures

The primary patient outcome was prevention or alleviation of behavior and mood problems. This outcome was measured using the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI; Cummings et al., 1994), the same primary outcome used in the Alzheimer’s Collaborative Care study (Callahan et al., 2006). The NPI uses an interview format to solicit reports from an informant familiar with the patient’s behavior and inquires about the frequency and severity of behavioral disturbances that commonly occur throughout the course of dementia, including anxiety, agitation, apathy, irritability, aberrant motor activity, euphoria, dysphoria, disinhibition, delusions, and hallucinations. The NPI is scored such that higher scores represent greater symptoms. It has been estimated that a 1-point decline in total NPI score is associated with an additional $250 to $400 annually in direct health care costs (Murman & Colenda, 2005).

The secondary patient outcome was self-reported quality of life, using the Quality of Life-Alzheimer’s Disease Scale (QOL-AD; Logsdon, Gibbons, McCurry, & Teri, 2002). The rationale for using a patient-reported outcome measure was that the proposed intervention was intended to involve the patient as an equal partner and because the effects of interventions involving dyads on patient self-reported QOL are virtually unknown (Smits et al., 2007). The QOL-AD consists of 13 items encompassing conceptual domains of QOL in older adults; in an article reporting its psychometric properties, internal consistency reliability for the QOL-AD was 0.84, and validity was established through expected correlations with measures of depression and physical function (Logsdon et al., 2002).

Family Caregiver Measures

The primary outcome for study family caregivers was prevention or alleviation of depressive symptoms over the 12-month study period. This outcome was measured using the 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression (CES-D) inventory (Radloff, 1977). Internal consistency reliability of this measure has been consistently high, and strong evidence of convergence and discriminant validity has been reported (Ostwald, Hepburn, Caron, Burns, & Mantell, 1999; Radloff, 1977).

The secondary family caregiver outcomes emphasized self-efficacy because this construct is studied much less often than depression or other mental health outcomes in intervention evaluations (Fortinsky, 2001; Smits et al., 2007). Two measures of family caregiver self-efficacy for managing dementia were used: symptom management self-efficacy and community support service use self-efficacy. The symptom management self-efficacy measure contains five items, and the community support service use self-efficacy measure contains four items; each item has a response range from 1 (not at all certain) to 10 (completely certain). Internal consistency reliability for these two measures were found to be 0.77 and 0.78, respectively, and construct validity was established by finding positive correlations between these two measures and a global caregiver competence scale, as well as negative correlations between these measures and the CES-D (Fortinsky, Kercher, & Burant, 2002).

Caregiver burden served as the other secondary outcome for family caregivers. The 12-item short form of the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) assesses caregivers’ subjective feelings about effects of care provision on emotional, physical, social, and financial life domains. The short form ZBI was shown to correlate very highly (0.92 to 0.97) with the full 22-item burden inventory at two different time points and showed high internal consistency reliability (0.88) (Bédard et al., 2001).

Acceptability Measures

Acceptability was evaluated by determining the level of satisfaction with the intervention from the perspectives of physicians, patients, and family caregivers. Based on discussions with intervention group PCPs before the start of the study about how they would judge the acceptability of the PPDC, investigators constructed a self-administered, patient-specific questionnaire for completion by PCPs when each patient ended the intervention. This questionnaire included six items with Likert scale responses (1 to 4) ranging from very satisfied to very dissatisfied, each accompanied by a comment section for PCPs to provide further explanations of their responses. PCPs were also asked open-ended questions about their experiences with and opinions on how to refine the PPDC intervention. PCPs completed these self-administered questionnaires and faxed or sent via e-mail attachment their completed questionnaires to the study data manager (A.K.) trained by the first author. A final debriefing session with intervention group PCPs was convened by the first author to learn any final recommendations they had about how to optimize NP involvement in their practice sites and with their patients going forward.

Patients and family caregivers also completed self-administered questionnaires inquiring about their satisfaction with the intervention. The 12-item treatment satisfaction questionnaire consisted of Likert scale responses (same responses as for PCP questionnaires) to questions tailored specifically to the PPDC intervention process. Domains of satisfaction—with the interventionist and with the content of the intervention material—were adapted from measures of acceptability used in published studies on a dyadic intervention in early stage dementia (Whitlatch, Judge, Zarit, & Femia, 2006) and a telephone intervention for family caregivers of dementia patients (Tremont, Davis, Bishop, & Fortinsky, 2008). Comments were solicited for each response, and two open-ended questions at the end allowed further comments. This self-administered questionnaire was completed separately by patients and caregivers following completion of the 12-month follow-up interview. The research interviewer did not ask these satisfaction questions in an interview style; instead, patients and family caregivers separately completed their own satisfaction questionnaires without any input from the research interviewer. This approach maximized the capacity of patients and caregivers to report on satisfaction independently and privately.

Analysis

This study was originally designed to enroll a total of 70 patient-family caregiver dyads, with 35 dyads in each study group. These samples would have resulted in 75% power to detect an effect size in the patient NPI score (primary patient outcome) similar to the effect size found in the Alzheimer’s Collaborative Care study (Callahan et al., 2006). We also originally intended to use parametric statistics to analyze results. However, due to lower-than-expected enrollment with resulting small samples, as well as non-normal distributions of most outcome variables in our study samples, we chose to use nonparametric statistics (Hollander & Wolfe, 1999) to analyze observed treatment group differences. Kruskal Wallis nonparametric tests were used to determine significant differences in median scores within each treatment group over time. To determine intervention effects, Freidman tests were used to compare median differences between treatment groups adjusted for the three time points. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. SAS 9.1 was used for these analyses. Intention-to treat-analyses were conducted for all models tested, with the assumption that any missing data were randomly distributed across study participants.

RESULTS

Study Samples and Characteristics

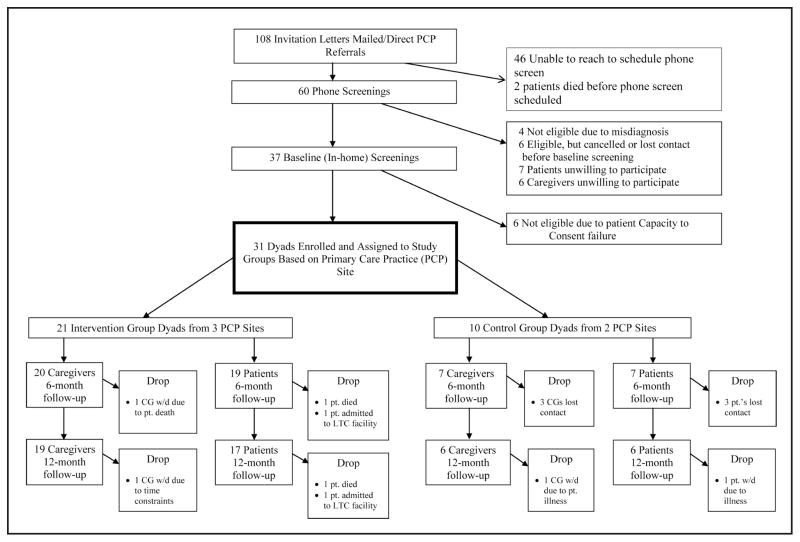

A total of 31 dyads were enrolled in this study—21 dyads in the PPDC intervention group and 10 dyads in the control group. The Figure provides a schematic view of study participant recruitment, starting with the total number of dyads that received either personalized PCP invitation letters to participate or direct referrals from PCPs to the research team, both per study protocol, and ending with the number of patients and caregivers who remained in the study through 12-month follow-up data collection.

Figure.

Flow chart of study participant recruitment.

Note. CG = caregiver.

Table 1 summarizes characteristics of the 31 study patients and their caregivers, respectively, at the time of baseline data collection. As Table 1 shows, intervention and control group patients did not differ significantly from one another in terms of sociodemographic characteristics or cognitive status, the latter measured by the MMSE (Folstein et al., 1975). Table 1 shows that intervention and control group caregivers did not differ significantly from one another in terms of baseline sociodemographic characteristics.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Study Patients and Family Caregivers

| Characteristic | Intervention Group (n = 21) | Control Group (n = 10) | Total (N = 31) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | ||||

| Female (%) | 62 | 40 | 55 | 0.25 |

| Age (mean, SD) (years) | 76.9 (7.8) | 80.7 (9.6) | 78.1 (8.4) | 0.25 |

| Race (%) | 0.55 | |||

| Caucasian | 95 | 90 | 94 | |

| African American | 5 | 10 | 6 | |

| Educational level (%) | 0.73 | |||

| Less than high school | 10 | 0 | 6 | |

| High school only | 48 | 40 | 45 | |

| Some college | 14 | 10 | 13 | |

| College graduate | 29 | 50 | 36 | |

| Lives with caregiver (%) | 95 | 80 | 90 | 0.24 |

| Married (%) | 76 | 60 | 71 | 0.35 |

| MMSE score, mean (SD) | 24.1 (5.5) | 25.1 (2.3) | 24.4 (4.7) | 0.46 |

| Family caregivers | ||||

| Female (%) | 48 | 70 | 55 | 0.24 |

| Age (mean, SD) (years) | 67.4 (13.8) | 69.9 (14.9) | 68.2 (14) | 0.65 |

| Race (%) | 0.97 | |||

| Caucasian | 91 | 90 | 90 | |

| African American | 9 | 10 | 10 | |

| Educational level (%) | 0.17 | |||

| Less than high school | 5 | 0 | 3 | |

| High school only | 33 | 10 | 26 | |

| Some college | 33 | 20 | 29 | |

| College graduate | 29 | 70 | 42 | |

| Relation to patient (%) | 0.75 | |||

| Spouse | 71 | 70 | 71 | |

| Adult child | 19 | 30 | 23 | |

| Other relative | 10 | 0 | 6 | |

| Married (%) | 95 | 90 | 94 | 0.58 |

| Annual income (%) | 0.45 | |||

| <$40,000 | 19 | 10 | 16 | |

| $40,000 to $49,999 | 19 | 10 | 16 | |

| ≥$50,000 | 52 | 70 | 58 | |

| Refused to answer | 10 | 10 | 10 | |

Note. MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination (Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975). Percentages may not total 100 due to rounding.

PPDC Intervention Delivery Results

Of the 21 intervention group dyads, 16 (76.2%) dyads completed all 12 in-home sessions with the NP per protocol. Among the non-completers, one dyad received nine visits and then the NP was unsuccessful in reaching them at home; one dyad received eight visits and then the patient was admitted to a nursing facility; one dyad received four visits and then chose to suspend visits and did not resume; one dyad received three visits and then the patient died; and one dyad received no in-home visits because the patient was admitted to a nursing facility before the first scheduled visit was made.

The mean length of all visits made to the 21 dyads was 1 hour 15 minutes (SD = 21 minutes, range = 30 minutes to 3 hours, 45 minutes). Visits 1 and 2 lasted longer on average than the remaining sessions, with mean lengths of 1 hour 51 minutes and 1 hour 38 minutes, respectively.

PPDC Efficacy Analysis Results

Table 2 summarizes all outcome measures related to specific hypotheses associated with study Objective 1. Patient outcomes were the NPI score and QOL-AD score, whereas family caregiver outcomes were depressive symptoms, burden, and dementia management self-efficacy scores. Kruskal Wallis test results show that neither treatment group of patients or caregivers experienced statistically significant changes in any of the median outcome measure scores over time (all values p > 0.05). Freidman test results show that there were no statistically significant between-group differences in any of the patient or family caregiver outcome measures after adjusting for the three time points (all values p > 0.05).

TABLE 2.

Median Outcomes at Baseline, 6-Month, and 12-Month Follow Up

| p Value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Treatment Group | Baseline | 6 Months | 12 Months | Kruskal Wallis Test | Freidman Test |

| Patient outcomes | ||||||

| NPI score | Intervention (n = 19) Control (n = 6) |

7 6 |

3 3 |

9 3.5 |

0.66 0.06 |

0.59 |

| QOL-AD score | Intervention (n = 17) Control (n = 6) |

38 40 |

39 41 |

37 40 |

0.99 0.24 |

0.95 |

| Family caregiver outcomes | ||||||

| CES-D score | Intervention (n = 19) Control (n = 6) |

7 1.5 |

5 4.5 |

6 2 |

0.54 0.21 |

0.80 |

| Symptom management self-efficacy score | Intervention (n = 19) Control (n = 4) |

40 37.5 |

39 45 |

37 44.5 |

0.60 0.52 |

0.92 |

| Support service self-efficacy score | Intervention (n = 19) Control (n = 4) |

31 35.5 |

36 38 |

35 38 |

0.29 0.75 |

0.14 |

| Zarit Burden Interview score | Intervention (n = 19) Control (n = 6 ) |

13 6.5 |

10 3 |

10 3 |

0.38 0.37 |

0.60 |

Note. NPI = Neuropsychiatric Inventory; QOL-AD = Quality of Life-Alzheimer’s Disease scale; CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale.

Acceptability Analysis Results

Table 3 summarizes results of satisfaction surveys completed by intervention group patients and family caregivers, and Table 4 summarizes results of satisfaction surveys completed by referring PCPs responsible for medical care for intervention group patients. Table 3 and Table 4 show that there was an extremely high level of satisfaction expressed by patients, caregivers, and PCPs participating in the PPDC intervention. Mean satisfaction scores for all items for all respondent groups ranged from 3.5 to 4.0, where 4 was the highest level of satisfaction on response scales. Table 3 indicates that all caregivers gave the highest rating of satisfaction to the item asking about whether PPDC program material was relevant to their situation, and patients gave highest satisfaction marks on the question of the interventionist’s ability to help them feel better about the future. Table 4 shows that participating PCPs were overwhelmingly satisfied with all aspects of the intervention. PCPs were most satisfied with the PPDC intervention’s effect on patient mood and outlook when patients made office visits during the study observation period. PCPs were slightly less satisfied with the interventionist’s reporting of patients’ progress at monthly meetings. Results from debriefing sessions with PCPs revealed that PCPs would have been even more satisfied if they had had the opportunity to hold periodic meetings together with the NP interventionist as well as the patient and family caregiver (results not shown).

TABLE 3.

Patient and Family Caregiver Satisfaction with the Proactive Primary Dementia Care (PPDC) Program

| n (Mean Scorea, SD) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Satisfaction Measure | Patients | Caregivers |

| Nurse practitioner (NP) sensitivity to your concerns | 14 (3.9, 0.3) | 19 (3.9, 0.2) |

| NP ability to answer your questions | 13 (4) | 19 (4) |

| NP enthusiasm about working with you | 14 (4) | 19 (4) |

| NP ability to help you feel better about facing the future | 13 (4) | 19 (3.9, 0.3) |

| NP ability to link you with community resources | 11 (3.8, 0.4) | 19 (3.9, 0.3) |

| Overall satisfaction with NP | 13 (4) | 19 (4) |

| PPDC program material relevance to your situation | 10 (3.8, 0.4) | 18 (4) |

| Quality of discussion of material | 12 (3.8, 0.4) | 19 (4) |

| Quality of dyad discussions between NP meetings | 11 (3.7, 0.7) | 19 (3.5, 0.7) |

| Amount of information learned on how to plan for the future | 12 (3.6, 0.9) | 19 (3.9, 0.2) |

| Amount of information learned about community resources | 12 (3.5, 0.9) | 19 (3.9, 0.5) |

| Overall program satisfaction | 13 (3.9, 0.4) | 19 (3.9, 0.3) |

Satisfaction measure scores range from 1 (very dissatisfied) to 4 (very satisfied).

TABLE 4.

Primary Care Physician Satisfaction with the Nurse Practitioner’s Care

| Satisfaction Measure | na | Mean Scoreb (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Monitoring the patient’s medication for dementia symptoms | 18 | 3.8 (0.4) |

| Monitoring the status of any comorbidities and related symptoms | 18 | 3.8 (0.4) |

| Reporting on the patient’s progress at monthly meetings | 18 | 3.7 (0.7) |

| Having an effect on the mood and outlook of the patient based on office visits during the year | 16 | 4.0 (0.0) |

| Saving you time during the year in taking care of the patient’s dementia-related problems | 16 | 3.8 (0.4) |

| Your overall satisfaction with the PPDC intervention | 18 | 3.8 (0.4) |

Note. PPDC = proactive primary dementia care.

n refers to the number of patients whose care by the nurse practitioner was rated by the eight participating intervention group primary care physicians.

Satisfaction measure scores range from 1 (very dissatisfied) to 4 (very satisfied).

DISCUSSION

Several study findings and experiences are noteworthy, particularly as they relate to implications for future nursing research, nursing practice, and public policy related to community-based care for individuals with dementia and their families. First, all stakeholders—PCPs, patients, and caregivers—reported overwhelming satisfaction with the PPDC care model, particularly the in-home care setting of care delivery.

These acceptability results strongly suggest that the NP-guided PPDC care model has demonstrated proof of concept to the key model participants. One caution regarding these results is that with a single interventionist, reported satisfaction might be due to personal relationships between NP and stakeholders rather than the intervention itself; however, satisfaction items completed by patients, caregivers, and PCPs included items that focused on NP skills as distinct from personality, and all of these items were rated highly as well.

Second, the PPDC intervention did not measurably improve patient or family caregiver outcomes compared to those in the control group patients and caregivers. Although this finding might be interpreted as a less-than-efficacious intervention, it is also possible that outcomes did not change over time in either treatment group because during the 12-month intervention period patients did not experience measurable cognitive decline. Specifically, median MMSE scores for the 17 intervention group patients with complete follow-up data declined very slightly from 26 to 24 between baseline and 12-month follow-up, whereas for the 6 control group patients with complete follow-up data median MMSE scores declined by only 1 point, from 26 to 25, over their follow- up period. Therefore, it is possible that little change was observed across all patient and family caregiver outcome measures because the severity of patients’ cognitive symptoms remained nearly stable over the study period. From the perspective of the PLST model that guided the intervention, stress threshold levels were not necessarily lowered during the 12-month observation period because patients’ cognitive symptoms remained nearly stable.

The lesson from this finding is that patients with a more diverse dementia experience, including those with more progressive dementia-related symptoms, should be studied in future trials such as the PPDC. Additionally, future studies recruiting patients with relatively mild cognitive decline at study baseline must allow for a longer follow-up period than 12 months to increase the likelihood that patients will experience cognitive decline, which is often the trigger for development of neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients and increased levels of burden and depressive symptoms as well as decreased self-efficacy levels in family caregivers. A larger-scale trial would allow for a longer follow-up period to overcome this important study limitation.

Closer inspection of median score patterns in Table 3 suggests the following trends: Intervention group family caregivers had more depressive symptoms and higher burden scores at baseline than control group caregivers; changes over time in NPI scores favored control group patients; and symptom management self-efficacy score changes over time favored control group caregivers. Observed trends in changes over time are in the opposite direction than hypothesized, and they might be explained by intervention group caregivers having greater baseline mental health symptoms than controls, along with an insufficiently potent intervention to counteract these between-group differences in baseline caregiver mental health.

Third, PCPs reported to the investigative team in a final debriefing session that, although they were satisfied with the PPDC intervention content, they would prefer to work with NPs who are fully employed in their practice sites. A key implication of this finding is that NPs serving as dementia care specialists, or more broadly as geropsychiatric NPs, would more quickly assume their role as a team member if recruited from the ranks of existing NPs working within PCP sites and then trained to work with patients with dementia and their families. More broadly, the collaborative care and comanagement principles and models on which this study is based (Callahan et al., 2006; Reuben et al., 2013; Unützer et al., 2002) would appear to be highly acceptable to PCPs in this study if the PPDC model is refined to combine office and home visiting for longer-term clinical oversight of patients with dementia and their families.

Fourth, PCPs reported in the final debriefing session that they believed the PPDC intervention could be equally effective in a much shorter time period than 12 months. They suggested that a 4-month intervention in which the first two visits retained focus on complete review of medications and systems for signs of additional comorbidities, and in which the remaining visits focused on teaching patients and families about how to prepare for the future given the course of dementia diseases, stood a much greater chance of being reimbursable by Medicare and other insurers. These refinements might lead to a more financially sustainable model of NP-guided dementia care as an extension of customary primary care.

Finally, major unanticipated challenges hampered recruitment success for this study, yielding an under-powered study because only 31 dyads were enrolled compared to the originally expected 70 dyads on which power estimates were based. The PCP practice network that had agreed to supply intervention and control group sites for this study made a critical business decision (i.e., to implement steps necessary to achieve patient-centered medical home [PCMH] status) coincident with the study period. Achieving PCMH status, an important goal for many physician groups in the current health care policy climate in the United States, involved a tremendous amount of site reengineering at participating PCP sites and other network sites, including purchase and implementation of and complete conversion to electronic health records and development of associated meaningful use activities. These PCMH accreditation-related activities led to considerable office flow changes as well. Control group sites that had originally agreed to participate in this study withdrew due to the overwhelming requirements associated with PCMH-related activities. Intervention sites that agreed to participate in the study remained committed; however, the amount of time available to office staff to assist with recruitment was significantly reduced due to priority placed on PCMH-related activities. In July 2011, this PCP network achieved Level III PCMH accreditation from the National Center for Quality Assurance for all 80 of its practice sites. More recently, in January 2013, this PCP network achieved Medicare Shared Savings Accountable Care Organization approval from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. This achievement bodes well for future studies involving creative uses of NPs within this and other PCP networks, including a larger-scale trial of a refined PPDC intervention.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institutes of Health (R21 NR011127).

Footnotes

The authors have disclosed no potential conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise.

Contributor Information

Dr. Richard H. Fortinsky, Professor and Health Net, Inc. Chair in Geriatrics and Gerontology, UConn Center on Aging, University of Connecticut Health Center, Farmington.

Dr. Colleen Delaney, Associate Professor, School of Nursing, University of Connecticut, Storrs.

Dr. Ofer Harel, Associate Professor, Department of Statistics, University of Connecticut, Storrs.

Ms. Karen Pasquale, Program Administrator and Senior Project Manager, Connecticut Center for Primary Care, Farmington.

Ms. Elena Schjavland, Doctoral candidate, School of Nursing, University of Connecticut, Storrs.

Mr. John Lynch, Executive Director, Connecticut Center for Primary Care, Farmington.

Ms. Alison Kleppinger, Clinical Research Associate, UConn Center on Aging, University of Connecticut Health Center, Farmington.

Ms. Suzanne Crumb, Clinical Research Assistant, University of Connecticut Health Center, Farmington, Connecticut.

References

- Alzheimer’s Association. 2013 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.02.003. Retrieved from http://www.alz.org/downloads/facts_figures_2013.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bamford C, Lamont S, Eccles M, Robinson L, May C, Bond J. Disclosing a diagnosis of dementia: A systematic review. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2004;19:151–169. doi: 10.1002/gps.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass DM, Clark PA, Looman WJ, McCarthy CA, Eckert S. The Cleveland Alzheimer’s managed care demonstration: Outcomes after 12 months of implementation. The Gerontologist. 2003;43:73–85. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bédard M, Molloy DW, Squire I, Dubois S, Lever JA, O’Donnell M. The Zarit Burden Interview: A new short version and screening version. The Gerontologist. 2001;41:652–657. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.5.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellg AJ, Borrelli B, Resnick B, Hecht J, Minicucci DS, Ory M, Czajkowski S. Enhancing treatment fidelity in health behavior change studies: Best practices and recommendations from the NIH Behavior Change Consortium. Health Psychology. 2004;23:443–451. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.5.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodaty H, Arasaratnam C. Meta-analysis of nonpharmacological interventions for neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;169:946–953. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11101529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckwalter KC. Envisioning the future of geropsychiatric nursing. In: Devereaux Melillo K, Crocker Houde S, editors. Geropsychiatric and mental health nursing. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers; 2005. pp. 393–399. [Google Scholar]

- Callahan CM, Boustani MA, Unverzagt FW, Austrom MG, Damush TM, Perkins AJ, Hendrie HC. Effectiveness of collaborative care for older adults with Alzheimer’s disease in primary care: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;295:2148–2157. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.18.2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callahan CM, Hendrie JC, Tierney WM. Documentation and evaluation of cognitive impairment in elderly primary care patients. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1995;122:422–429. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-6-199503150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy A. Health policy briefs: Nurse practitioners and primary care. 2012 Oct 25; Retrieved from http://www.healthaffairs.org/healthpolicybriefs/brief.php?brief_id=79.

- Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: Comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44:2308–2314. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.12.2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donelan K, DesRoches CM, Dittus RS, Buerhaus P. Perspectives of physicians and nurse practitioners on primary care practice. New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;368:1898–1906. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1212938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans LK, Beck C, Buckwalter KC. Carpe diem: Nursing making inroads to improve mental health for elders. Nursing Outlook. 2012;60:107–108. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg LF, Whitlatch CJ. Are persons with cognitive impairment able to state consistent choices? The Gerontologist. 2001;41:374–382. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.3.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortinsky RH. How linked are physicians to community support services for their patients with dementia? Journal of Applied Gerontology. 1998;17:480–498. doi: 10.1177/073346489801700405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fortinsky RH. Health care triads and dementia care: Integrative framework and future directions. Aging & Mental Health. 2001;5(Suppl 1):S35–S48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortinsky RH, Kercher K, Burant CJ. Measurement and correlates of family caregiver self-efficacy for managing dementia. Aging & Mental Health. 2002;6:153–160. doi: 10.1080/13607860220126763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortinsky RH, Kulldorff M, Kleppinger A, Kenyon-Pesce L. Dementia care consultation for family caregivers: Collaborative model linking an Alzheimer’s association chapter with primary care physicians. Aging & Mental Health. 2009;13:162–170. doi: 10.1080/13607860902746160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortinsky RH, Leighton A, Wasson JH. Primary care physicians’ diagnostic, management, and referral practices for older persons and families affected by dementia. Research on Aging. 1995;17:124–148. doi: 10.1177/0164027595172002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdner LA, Buckwalter KC, Reed D. Impact of a psychoeducational intervention on caregiver response to behavioral problems. Nursing Research. 2002;51:363–374. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200211000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin LN. Good news for dementia care: Caregiver interventions reduce behavioral symptoms in people with dementia and family distress. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;169:894–897. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12060774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerriero Austrom M, Damush TM, Hartwell CW, Perkins T, Unverzagt F, Boustani M, Callahan CM. Development and implementation of nonpharmacologic protocols for the management of patients with Alzheimer’s disease and their families in a multiracial primary care setting. The Gerontologist. 2004;44:548–553. doi: 10.1093/geront/44.4.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall G, Buckwalter KC. Progressively lowered stress threshold: A conceptual model for care of adults with Alzheimer’s disease. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 1987;1:399–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollander M, Wolfe DA. Nonparametric statistical methods. New York, NY: Wiley; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Iglehart JK. Expanding the role of advanced nurse practitioners—Risks and rewards. New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;368:1935–1941. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr1301084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeste DV, Palmer BW, Appelbaum PS, Golshan S, Glorioso D, Dunn LB, Kraemer HC. A new brief instrument for assessing decisional capacity for clinical research. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:966–974. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.8.966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch T, Iliffe S. Rapid appraisal of barriers to the diagnosis and management of patients with dementia in primary care: A systematic review. BMC Family Practice. 2010;11:52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-11-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logsdon RG, Gibbons LE, McCurry SM, Teri L. Assessing quality of life in older adults with cognitive impairment. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2002;64:510–519. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200205000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslow K. Translating innovation to impact: Evidence-based interventions to support people with Alzheimer’s disease and their CGs at home and in the community. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.agingresearch.org/content/article/detail/21737.

- Murman DL, Colenda CC. The economic impact of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: Can drugs ease the burden? Pharmacoeconomics. 2005;23:227–242. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200523030-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostwald SK, Hepburn KW, Caron W, Burns T, Mantell R. Reducing caregiver burden: A randomized psychoeducational intervention for caregivers of persons with dementia. The Gerontologist. 1999;39:299–309. doi: 10.1093/geront/39.3.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reuben DB, Ganz DA, Roth CP, McCreath HE, Ramirez KD, Wenger NS. Effect of nurse practitioner comanagement on the care of geriatric conditions. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2013;61:857–867. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Beach SR. Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: The Caregiver Health Effects Study. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282:2215–2219. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.23.2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, O’Brien AT, Bookwala J, Fleissner K. Psychiatric and physical morbidity effects of dementia caregiving: Prevalence, correlates, and causes. The Gerontologist. 1995;35:771–791. doi: 10.1093/geront/35.6.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M, Hall GR, Gerdner L, Buckwalter KC. Application of the Progressively Lowered Stress Threshold Model across the continuum of care. Nursing Clinics of North America. 2006;41:57–81. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits CH, de Lange J, Dröes RM, Meiland F, Vernooij-Dassen M, Pot AM. Effects of combined intervention programmes for people with dementia living at home and their caregivers: A systematic review. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2007;22:1181–1193. doi: 10.1002/gps.1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teri L, Rabins P, Whitehouse P, Berg L, Reisberg B, Sunderland T, Phelps C. Management of behavior disturbance in Alzheimer disease: Current knowledge and future directions. Alzheimer’s Disease & Associated Disorders. 1992;6:77–88. doi: 10.1097/00002093-199206020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremont G, Davis JD, Bishop DS, Fortinsky RH. Telephone-delivered psychosocial intervention reduces burden in dementia caregivers. Dementia. 2008;7:503–520. doi: 10.1177/1471301208096632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unützer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, Williams JW, Jr, Hunkeler E, Harpole L, Langston C. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288:2836–2845. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. National plan to address Alzheimer’s disease: 2013 update. 2013 Retrieved from http://aspe.hhs.gov/daltcp/napa/NatlPlan2013.pdf.

- Vickrey BG, Mittman BS, Connor KI, Pearson ML, Della Penna RD, Ganiats TG, Lee M. The effect of a disease management intervention on quality and outcomes of dementia care: A randomized, controlled trial. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2006;145:713–726. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-10-200611210-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlatch CJ, Feinberg LF, Tucke S. Accuracy and consistency of responses from persons with cognitive impairment. Dementia. 2005;4:171–183. doi: 10.1177/1471301205051091. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlatch CJ, Judge K, Zarit SH, Femia E. Dyadic intervention for family caregivers and care receivers in early-stage dementia. The Gerontologist. 2006;46:688–694. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.5.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. International classification of diseases. Geneva, Switzerland: Author; 1978. (9th rev.) [Google Scholar]