Abstract

The study purposes were to 1) describe interaction behaviors and factors that may impact communication and 2) explore associations between interaction behaviors and nursing care quality indicators between 38 mechanically ventilated patients (≥60 years) and their intensive care unit nurses (n=24). Behaviors were measured by rating videotaped observations from the Study of Patient-Nurse Effectiveness with Communication Strategies (SPEACS). Characteristics and quality indicators were obtained from the SPEACS dataset and medical chart abstraction. All positive behaviors occurred at least once. Significant (p<.05) associations were observed between: 1) positive nurse and positive patient behaviors, 2) patient unaided augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) strategies and positive nurse behaviors, 3) individual patient unaided AAC strategies and individual nurse positive behaviors and 4) positive nurse behaviors and pain management, and 5) positive patient behaviors and sedation level. Findings provide evidence that nurse and patient behaviors impact communication and may be associated with nursing care quality.

Keywords: mechanical ventilation, critical care, older adults, interaction behaviors, nursing care quality, communication

Inability to communicate as a result of mechanical ventilation is a significant emotional stressor for critically ill patients (Carroll, 2007; Menzel, 1998; Patak, Gawlinski, Fung, Doering, & Berg, 2004). Moreover, communication difficulties during hospitalization are a significant risk factor for preventable adverse events, particularly for older adults (Bartlett, Blais, Tamblyn, Clermont, & MacGibbon, 2008). Critical care nurses are in an excellent position to lessen the detrimental effects of communication impairment by modifying their behaviors during bedside patient care (Happ et al., 2010).

Interaction behaviors are verbal and nonverbal behaviors communicated by both patients and nurses that can influence the interpersonal relationship. However, the association between nurse and patient interaction behaviors and nursing care quality has not been explored. While there is a growing recognition that improved communication is essential to improving healthcare quality and safety, little attention has been focused on the role of patient communication. The purposes of this study were to 1) describe nurse and patient interaction behaviors and factors that may positively or negatively impact communication between nurses and nonspeaking critically ill older adults in the intensive care unit (ICU) and 2) explore the association between nurse and patient interaction behaviors and nursing care quality indicators. Specifically, we aimed to 1a) identify interaction behaviors that nurses and nonspeaking critically ill older adults use during observation sessions in the ICU, 1b) describe the frequency of use of augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) strategies, 1c) evaluate the relationship between individual interaction behaviors and individual AAC strategies and 2) explore the association between interaction behaviors and nursing care quality indicators, including sedation use, sedation level, physical restraint use, pain management, and unplanned device disruption, during a two-day observation period.

BACKGROUND

Mechanical ventilation (MV) is the primary therapy used to provide pulmonary support for patients in the ICU and an estimated 800,000 patients receive this therapy each year (Wunsch et al., 2010). MV poses a barrier to communication for critically ill patients because they cannot vocalize. This difficulty communicating can exacerbate negative emotions and acute confusion (Carroll, 2007; Patak et al., 2004; Rier, 2000).

Older adults are at an increased risk for communication difficulties because of cognitive decline, physiological changes, including changes in their vision, speech, and hearing, and environmental factors such as noise (Ebert & Heckerling, 1998; Park & Song, 2005; Pope, Gallun, & Kampel, 2013). These changes and environmental factors can contribute to communication breakdowns, misunderstandings, and difficulty recalling what was said (Pope et al., 2013; Yorkston, Bourgeois, & Baylor, 2010). Older adults may utilize different interaction behaviors during critical illness to compensate for these changes.

Communication is an essential element of quality nursing care. The use of verbal and nonverbal interaction behaviors can help establish a synergistic care relationship between nurses and patients (Hansebo & Kihlgren, 2002). While previous work has shown that communication interactions can influence patient satisfaction (de los Ríos Castillo & Sánchez-Sosa, 2002), research on the how patient communication difficulties effects outcomes and adverse events in acute and critical care settings is limited (Bartlett et al., 2008). Salyer and Stuart (1985) reported that when ICU nurses exhibited positive interaction behaviors, such as praise or explaining a procedure, the patient’s reactions were often positive. Negative interaction behaviors by the nurse, such as criticizing, yielded negative reactions by the patient (Salyer & Stuart, 1985). A prior study supports ability of communication training to decrease negative nurse interaction behaviors and improve satisfaction of ICU patients (de los Ríos Castillo & Sánchez-Sosa, 2002). However, the intervention was not tested in a population of nonvocal mechanically ventilated, older patients.

In order to promote a symmetrical communication interaction and optimize patient-centered care, nurses need to share control and power to encourage active patient participation in communication exchanges (Kettunen, Poskiparta, & Karhila, 2003). Augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) allows patients to express thoughts, needs, and wants when an individual has a communication limitation that hinders natural speech (Beukelman & Mirenda, 2005). Unaided AAC strategies, such as mouthing, gesturing, and head nods, are the most common methods utilized by MV patients when communicating with healthcare providers, caregivers, and family (Menzel, 1998; Thomas & Rodriguez, 2011). Several studies have investigated the utility of “low tech” AAC strategies, such as writing and communication boards, with critically ill patients (Patak et al., 2004; Stovsky, Rudy, & Dragonette, 1988). Others have examined the benefits of more sophisticated electronic AAC devices in the care of critically ill adults. However, these were primarily feasibility studies that evaluated device use in small samples and lacked comparison groups (Happ, Roesch, Kagan, Garrett, & Farkas, 2007; Happ, Roesch, & Garrett, 2004; Miglietta, Bochicchio, & Scalea, 2004; Rodriguez & VanCott, 2005). Most importantly, previous studies have not evaluated the potential of AAC use to influence nurse-patient interaction behaviors or evaluated the type of AAC strategies older adult patient utilize.

Finally, the Joint Commission has recognized the importance effective provider-patient communication has on patient safety and new accreditation standards require providers to assess and accommodate for acquired communication disability during critical illness (The Joint Commission, 2010). Improved nurse-patient communication is important because it has the potential to enhance patient understanding of the treatment plan and decrease behaviors that lead to adverse outcomes. Physical restraint use, pain management, sedation use, and unplanned device removal are nursing care quality indicators potentially linked to communication (Alasad & Ahmad, 2005; Happ, 2000; Happ, Tuite, Dobbin, DiVirgilio-Thomas, & Kitutu, 2004; Weinert, Chlan, & Gross, 2001). To best inform communication interventions and intervention testing, research is needed to understand how nurse-patient interaction behaviors affect nursing care quality and safety for vulnerable, critically older adults.

METHODS

This expanded secondary study employed a descriptive correlational design utilizing data collected on a subset of older adult patients (≥60 years) enrolled in the Study of Patient-Nurse Effectiveness with Communication Strategies (SPEACS). The study received institutional review board approval and a waiver of the HIPAA authorization requirement for the sharing of contact information was obtained. All subjects provided informed consent and agreed to use of video-recorded observation sessions for future research (R01-HD043988; Happ 2003–2008) (Happ et al., Accepted).

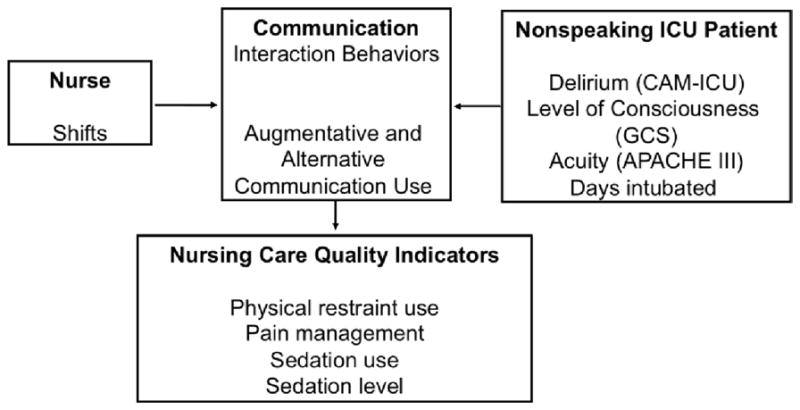

Research Model

The research model was adapted from the nurse-patient communication research model used in the SPEACS Study (Happ, Sereika, Garrett, & Tate, 2008) and in subsequent studies (Happ & Barnato, 2009–2011) (See Figure 1). In the SPEACS research model, the process outcomes measured were ease, success, frequency, and quality of communication. For the current study, interaction behaviors are the process measures and the outcomes are nursing care quality indicators.

Figure 1.

Research Model

Setting and Participants

The SPEACS study sample was comprised of MV patients and their ICU nurses. It was conducted in a 32-bed medical ICU (MICU) and a 22-bed cardiothoracic ICU (CT-ICU) of a large academic medical center located in southwestern Pennsylvania. We report results with unit names removed to preserve anonymity of participants.

Patients were eligible to participate if they were: (1) mechanically ventilated through endotracheal or tracheal intubation; (2) intubated for ≥48 hours and expected to remain intubated for an additional 2 days; (3) awake and responding to commands; (4) understands English. In the current study, only patients 60 years of age or older were included. Patients were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: (1) Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) < 13; (2) previous hearing or speech impairment seriously interfering with communication, or (3) previous diagnosis of dementia.

After patients were determined to be eligible, the project coordinator or trained graduate researcher obtained written informed consent. Patients who either:1) could not state their name by mouthing, 2) could not distinguish the difference between two colored pieces of paper (Higgins & Daly, 1999), 3) were unable to attend to the consent information, and/or 4) had a positive CAM-ICU were determined to be decisionally incapable of consenting and a surrogate was contacted. Eligibility criteria and recruitment procedures for the SPEACS study have previously been described in detail (Happ et al., 2011; Happ et al., 2008; Nilsen, Sereika, & Happ, 2013).

Measurement

Interaction Behaviors

The tool used to measure interaction behavior was modified from prior observational studies that enrolled ICU patients with and without the ability to speak (de los Ríos Castillo & Sánchez-Sosa, 2002; Hall, 1996; Salyer & Stuart, 1985). The modified tool, termed the Communication Interaction Behavior Instrument (CIBI), consisted of 29 interaction behaviors divided into the four subscales: (1) positive nurse, (2) negative nurse, (3) positive patient, and (4) negative patient (see Table 2). Nurses and patients could demonstrate both positive and negative behaviors during an interaction. Each behavior was measured as any occurrence (presence/absence) during an observation session. A count of different behaviors was computed for each subscale. Prior to use, the modified tool was tested for reliability and validity. Eight of 14 positive nurse behaviors had kappa coefficients of 0.60 or greater and 6 of 9 positive patient behaviors had kappa coefficients of 0.60 or greater for 75% of the sessions (Nilsen et al., In press).

Table 2.

Interaction Behaviors (n=29)

| Positive Nurse Behaviors (n=14): behaviors that communicate interpersonal support and encouragement | |

| Sharing | Offers the patient an item to support their wellbeing (other than prescribed medications or treatments) |

| Praising | Verbal comments indicating approval, recognition or praise |

| Visual Contact | Looks the patient in the eyes for as long as the nurse is at the bedside |

| Proximity with Speech | Stands at least arm’s length from the patient and provides spoken information |

| Physical Contact | Touches, pats or hugs the patient. |

| Social Politeness | Uses terms including “please”, “thank you”, and greets the patient by name. |

| Preparatory Information | Information given before a procedure. |

| Expanded Preparatory Information | Information given before a procedure, includes expanded explanation |

| Preparatory Information (Brief Delay) | Information given before a procedure but the procedure start is >10 seconds after the information is given |

| Expanded Preparatory Information (Brief Delay) | Information given before a procedure that includes expanded explanation but the start of the procedure is > 10 seconds after the information is given. |

| Smiling | Lifting lip scorners while looking the patient in the eyes |

| Modeling | Body changes or movements accompanied by the corresponding descriptive verbalization, reproduced by the patient |

| Laughing | Lifting the lips corners or congruently opening the mouth while emitting the characteristic voiced laughter sound |

| Augmenting | Augments patient’s auditory comprehension by writing, gesturing, showing object, |

| Negative Nurse Behaviors (n=3): behaviors by the nurse that inhibit the interpersonal relationship | |

| Disapproving | Verbalizations implicating disagreement, negation, disgust or criticism |

| Yelling | Loud verbalizations containing comments, threats, criticism or disapproval |

| Ignoring the Patient | After a request by the patient, the nurse does not answer or perform the requested action within five seconds in a congruent manner |

| Positive Patient Behaviors (n=9): behaviors that communicate interpersonal engagement, responsiveness and interdependence in the care recipient role | |

| Acceptance | Head, eyes or hand movement expressing agreement, acceptance or satisfaction. |

| Following Instructions | Engaging in a behavior in response to an request or instruction by the nurse |

| Visual Contact | Looks the nurse in the eye when the nurse asks a questions/addresses patient |

| Physical Contact | Touches, pats or hugs the nurse. |

| Request | Verbal, digital or manual indications to express a need or request |

| Smiling | Lifting lips corners while looking the patient in the eyes |

| Maintaining Attention | Keeps eye contact while nurse provides an explanation, information, instruction |

| Laughing | Lifting the lips corners or congruently opening the mouth. |

| Praising | Clearly distinguishable gesture or message expressing gratefulness or approval |

| Negative Patient Behaviors (n=3): behaviors that are expressions of disapproval or withdrawal from the interpersonal care relationship | |

| Disagreement | Actions expressing opposition to nurse’s actions |

| Disgust | Gestures or facial expressions indicating disgust, annoyance, or frustration. |

| Ignoring the nurse | After a request, the patient does not answer or respond within 5 seconds in a congruent manner |

The two coders independently rated interaction behaviors on each of four 3-minute video-recorded observation sessions of nurse-patient interaction (morning and afternoon) with each nurse-patient dyad. Observations were initiated when the nurse entered the room and the researchers followed (Happ et al., 2008). Patients were aware of the video- recording and assent was verified at each observation. Observations that included personal hygienic care and emergency situations were not included. The length of 3 minutes for an observation session was based on previous research that demonstrated ICU interactions between nurse and patients lasted approximately 3–5 minutes (Ashworth, 1980; Bergbom-Engberg & Haljamae, 1993; Salyer & Stuart, 1985). There were a total of 4 observation sessions (n=152) over the two-day observation period (n=76 observation days). Coders received 18 hours of training and independently coded 5 pilot cases before performing analysis on this sample. To enhance the validity, employed dual raters to observe interactions and adjudicate discrepancies (Nilsen et al., In press). If the coders differed on the presence or absence of a behavior and could not come to a consensus, a third experienced coder reviewed the session in question and provided feedback and arbitration.

Patient Characteristics

Level of Consciousness (LOC) was measured with the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) (Teasdale & Jennett, 1974) adapted to account for patient ability to communicate words through nonvocal methods (Happ et al., 2011). Because GCS scores lacked variability, they were dichotomized to represent: 1) awake and completely oriented (GCS=15) or 2) compromised (GCS≤ 14) In the SPEACS study, inter-rater agreement for 10% of sessions was > .90%. Delirium was measured as either present or absent through the Confusion Assessment Method for ICU (CAM-ICU) (Ely, Margolin, et al., 2001). In the SPEACS study, inter-rater agreement for 10% of sessions was > .90%. Acuity was measured by the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE III) scoring system which assigns points (range 0–299) for alterations in acute physiology, age, and chronic health status (Wagner, Knaus, Harrell, Zimmerman, & WATIS, 1994). Raters achieved > .90 agreement on all scores (Happ et al., 2008). Duration of intubation prior to study enrollment was recorded from the electronic medical record as the number of days during the current admission that a patient was intubated before study entry. This variable was included because previous analysis demonstrated that length of intubation prior to study enrollment had a curvilinear association with the amount of time the nurse talked to a patient during interactions (M. Nilsen, ., S. Sereika, & M. Happ, 2013). Table 1 provides psychometrics on the measurements and a schedule of when the measurements were administered.

Table 1.

Variables, Measures, and Measurement Schedule for Patient Characteristics

| Variables | Measures | Inter-rater Reliability | Observation Session | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| Delirium | Confusion Assessment Method for ICU (CAM-ICU) | .96*1 | * | * | * | * | * |

| Level of Consciousness | Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) | .64*2 | * | * | * | * | * |

| Severity of Illness | Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE III) | .90+3 | * | * | * | * | * |

| Days Intubated Prior to Enrollment | Days intubation prior to enrollment (in days) | - | * | ||||

Cohen’s Kappa Coefficient,

Intra-class Correlation Coefficient

Note: References for inter-rater reliability statistics:

Nurse Characteristics

Nurses in the SPEACS study received 1) basic communication skills training (BCST), or 2) BCST with additional training in electronic AAC device plus individualized speech language pathologist consultation (AAC+SLP), depending on group participation. Low-tech communication materials (e.g., alphabet boards, picture boards, writing materials) were available to those who received BCST. Low tech materials and high tech (electronic) AAC devices were available to those who received BCST and AAC+SLP (Happ et al., 2008). Nurses were included in the present study irrespective of group participation to enable sampling of interaction behaviors by nurses with varied training. Nursing shift was used as a marker of possible interaction exposure between nurses and patients. It was measured as a binary variable denoting whether the study nurse worked a 12-hour or 8-hour shift for each observation day.

Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) Strategy Usage

AAC strategies are the methods non-vocal, mechanically ventilated patients utilize to achieve the interaction behaviors. These strategies were categorized as: (1) unaided AAC strategies (mouthing, gesture, head nods, facial expressions, or non-verbal but communicative action), (2) low-technology (drawing, writing, use of picture boards or communication boards) and (3) high-technology strategies (direct selection or scanning using an electronic speech generating device) (Beukelman, Garrett, & Yorkston, 2007). Use of AAC strategies was determined by observation of the video recording and analysis of research observer field notes for each session. Because usage was relatively uncommon, low-tech and high-tech strategies categories where combined to denote whether any AAC strategies/devices were used during an observation session. The count of different AAC strategies was computed for each category. The data for strategy use was obtained from an existing SPEACS dataset.

Nursing Care Quality Indicators

Physical restraint use was defined as the presence or absence of wrist restraints on the patient and was measured during each session by direct observation, which has been shown to be an accurate and unobtrusive method of measuring physical restraints use (Fogel, Berkman, Merkel, Cranston, & Leipzig, 2009). Pain management was measured as presence or absence of pain via patient or nurse report. The patient was recorded as having pain if the nurse provided a pain score, stated the patient had pain without a score, or if the patient received “as needed” opioid analgesia (e.g. Percocet® or oxycodone) during the observation day. The concordance between direct report/observation and clinical record documentation of pain has been shown to be unsatisfactory (Morrison et al., 2006; Saigh, Triola, & Link, 2006), however, medical record documentation affords the best proxy for pain management for this study. Sedation use was calculated using a total equivalent dose of opioids and benzodiazepines for the observation days. These totals were converted to morphine and lorazepam equivalents using an established conversion formula (Cammarano, Drasner, & Katz, 1998; Lacy, Armstrong, Goldman, & Lance, 2004) that has been used in previous studies to compare sedation use among patients (de Wit et al., 2007; de Wit, Gennings, Jenvey, & Epstein, 2008; Dubois, Bergeron, Dumont, Dial, & Skrobik, 2001; Ely et al., 2004; Lat et al., 2009). Sedation-agitation level was measured using the Richmond Agitation and Sedation Scale (RASS) during each observation session to complement information to sedation use. The RASS is a 10-point scale with four levels of agitation, one level for calm and alert, and 5 levels of sedation (Sessler et al., 2002). Due to lack of variability in this sample, scores were collapsed to represent two categories: 1) calm or 2) agitated/sedated. The RASS is commonly utilized in critical care research to measure sedation level (Soukup et al., 2012) and for this study; it provides important and complementary information to sedation use. In the SPEACS study, inter-rater reliability was checked by independent rater for 10% of sessions, with > .90% agreement.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using IBM® SPSS® Statistics (version 20.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) and SAS (version 9.3, SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). For aim 1a, summary statistics were computed to describe interaction behaviors and AAC strategy use. Frequencies, percentages, and ranges were calculated for individual interaction behaviors and individual AAC strategies. For the count of different interaction behaviors (by subscale) and the count of different AAC strategies (by category), means and standard deviations were calculated as measures of central tendency and dispersion, respectively. Since study nurses were paired with more than one study patient, random nurse effects were also considered.

Group comparative statistics were utilized to evaluate differences in overall interaction behaviors by individual AAC strategy categories for aim 1b. Linear mixed effect modeling was applied to treat AAC strategy use as a time-dependent predictor variable (i.e., allowed to vary from session to session) to model the interaction behaviors. F-tests were used to investigate AAC strategy for unit, labeled A and B, and regression coefficients were used to summarize these associations. For aim 1c, marginal modeling with generalized estimating equation) was utilized to explore individual patient unaided AAC strategies association with individual positive nurse behaviors. The level of significance was set at .05 for two-sided hypothesis testing.

Nursing care quality indicators analyzed in aim 2 were both continuous (sedation use) as well as binary (physical restraint use, sedation level, and pain management). For all models fitted, regression coefficients with 95% confidence intervals and appropriate test statistics were computed to describe and test the associations between counts of behaviors and specific nursing care quality indicators. Linear mixed effect modeling was used to evaluate the association between the count of different interaction behaviors and sedation use, assuming a normal error distribution. For binary outcome variables, including pain management and sedation-agitation level, marginal modeling with generalized estimating equations was employed. GCS, acuity, delirium, length of intubation prior to study enrollment, and nursing shifts were included as time-dependent covariates in the repeated measures analyses. Due to limited variability and small sample size, linear mixed effects modeling could not be performed. To evaluate the association between the counts of positive nurse and patient behaviors and restraint use, positive nurse behaviors, positive patient behaviors, and the covariates, including APACHE, CAM-ICU, GCS, were each individually aggregated as a mean across the four observation sessions in order to perform binary logistic regression with any restraint use (yes, no) as the dependent variable.

FINDINGS

Patient Characteristics

The 38 patient participants were evenly distributed between the two units. The patients were 60 to 87 years of age (Mean=70.3 years, SD= 8.5), predominantly white (90%), with 8 to 21 years of formal education (Mean =12.9 years, SD= 2.8). At session 1, 28 patients (74%) were mechanically ventilated via a tracheostomy and by session 4, three additional patients (n=31, 82%) received a tracheostomy. Patients were awake and oriented (GCS =15) during 129 of the 152 observation sessions (85%). Ten patients (26%) had a compromised LOC for at least one observation session, while two patients (5%) were compromised during all sessions. Patients experienced delirium in 52 observation sessions (35%). Delirium status was missing for 13 sessions (9%). Of the 38 patients, 21 (55%) were delirious during at least one observation session and of these patients, 6 (16%) were delirious during all sessions. During the 76 observation days, APACHE III scores ranged from 36 to 105 with a mean of 62.8 (SD=14.32). The number of days patients were intubated prior to study enrollment ranged from 1 to 85 days with a mean of 17.4 days (SD=16.04).

Nurse Characteristics

The 24 nurses in this study ranged from 22 to 55 years of age (Mean=35.1 years, SD= 10.4). The nurses were predominantly female (79%), baccalaureate prepared (83%) with years in nursing practice and in critical care ranging from 1 to 33 with means of 10.0 (SD=10.7) and 7.2 (SD= 9.3) years, respectively. Finally, the study nurse worked an 8-hour shift as opposed to a 12-hour shift on 6 observation days (8%).

Nurse and Patient Interaction Behaviors

Positive nurse behaviors were associated with an increase in positive patient behaviors (F(1,107)=15.43, p≤.001). On average, nurses utilized 5.40 different positive behaviors per observation session (SD=1.82, Min=0, Max=9), while patients used 3.11 different positive behaviors per observation session (SD=1.74, Min=0, Max=7). The mean count of different positive patient behaviors and the mean count of different positive nurse behaviors did not vary by type of ICU.

Individual interaction behaviors are described in Table 2. Preparatory information was more common in the Unit B (n=32) than in the Unit A (n=18) (Wald Chi-Square=4.69, p=.030). The remaining positive nurse behaviors did not differ significantly by ICU. For negative patient behaviors, disagreement and disapproval co-occurred for two patients. Patient smiling occurred more often in the Unit A (n=23) than in Unit B (n=7) (Wald Chi-Square=6.58, p=.010). There were no significant differences between units for the remaining positive patient behaviors.

AAC Strategy Use

A mean of 3.4 different patient unaided AAC strategies were used per observation session (SD=1.35, Min=0, Max=6). On average, low-tech and high-tech AAC strategy usage was less common than unaided AAC strategy usage (Mean±SD=0.16±0.42, Min=0, Max=2). The mean and standard deviations for individual AAC strategies is reported in Table 4. Mouthing was the only unaided AAC strategy that was significantly different by unit: Unit A patients used mouthing more frequently than Unit B patients (53 occurrences vs. 33 occurrences) (F(1,107)=15.43, p=.03).

Table 4.

Communication Strategies across the sessions for the 38 Nurse-Patient Dyads

| Mean±SD | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unaided Strategies | |||

|

| |||

| Mouthing | 2.26±1.55 | 0 | 4 |

| Gesturing | 2.58±1.33 | 0 | 4 |

| Head Nods | 3.55±0.92 | 0 | 4 |

| Facial Expression | 1.68±1.38 | 0 | 4 |

| Non-verbal but communicative action (ex. purposeful look, purposeful squeeze) | 3.34±0.88 | 1 | 4 |

|

| |||

| Low Tech Strategies | |||

|

| |||

| Drawing | 0.03±0.16 | 0 | 1 |

| Writing | 0.32±0.77 | 0 | 3 |

| Points to letter board | 0.18±0.56 | 0 | 3 |

| First letter spelling while mouthing | 0.03±0.16 | 0 | 1 |

| Point to an encoded symbol representing a phrase | 0.03±0.16 | 0 | 1 |

| Indicate phrase in response to partner’s auditory/visual scanning of phrase choice list | 0.03±0.16 | 0 | 1 |

|

| |||

| High Tech Strategies | |||

|

| |||

| Direct Selection- Message | 0.03±0.16 | 0 | 1 |

| Scan- spell | 0.03±0.16 | 0 | 1 |

Relationship between Interaction behaviors and AAC use

The count of different unaided AAC strategies was positively associated with the count of positive nurse behaviors (F(1,121)=9.93, p=.002). In addition, the use of head nods was significantly associated with the count of different positive nurse behaviors (F(1,8)=10.85, p=.01). Table 5 shows the co-occurrence of individual patient unaided AAC strategies with individual positive nurse behaviors.

Table 5.

The Association Between Presence of Individual Patient Unaided AAC Strategies with the Presence of Individual Positive Nurse Interaction Behaviors (Univariate Results)

| Positive Nurse Behavior | Patient Unaided AAC Strategies | b | SE | z-value | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Praising | Facial Expression | 0.608 | 0.240 | 2.53 | .011 |

|

| |||||

| Visual Contact | Head Nods | 1.661 | 0.742 | 2.24 | .025 |

| Nonverbal but communicative | 1.298 | 0.548 | 2.37 | .018 | |

|

| |||||

| Physical Contact | Gesturing | −1.003 | 0.366 | −2.75 | .006 |

| Nonverbal but communicative | 1.032 | 0.324 | 3.19 | .001 | |

|

| |||||

| Preparatory Information | Mouthing | −0.887 | 0.361 | −2.46 | .014 |

|

| |||||

| Smiling | Mouthing | 0.776 | 0.382 | 2.03 | .042 |

| Head Nod | 1.509 | 0.694 | 2.18 | .030 | |

| Nonverbal but communicative | 1.194 | 0.468 | 2.55 | .011 | |

|

| |||||

| Laughing | Gesturing | 1.456 | 0.462 | 3.15 | .002 |

| Facial Expression | 1.042 | 0.368 | 3.00 | .003 | |

|

| |||||

| Augments | Mouthing | 1.756 | 0.555 | 3.17 | .002 |

| Gesturing | 1.874 | 0.425 | 4.41 | <.001 | |

| Head Nods | 2.574 | 0.880 | 2.92 | .003 | |

| Nonverbal but communicative | 1.396 | 0.556 | 2.51 | .012 | |

Nursing Care Quality Indicators (Outcome)

Patients had bilateral wrist restraints in 27 of the 152 observation sessions (18%). Of the 38 patients, 10 patients (26%) had bilateral wrist restraints present for at least 1 observation session and 3 patients (8%) had restraints during all four sessions. There were no occurrences of unilateral restraints. There were no significant associations between positive nurse behaviors, positive patient behaviors, or unaided AAC strategies and the use of restraints.

Patients were in pain during 33 of the 76 observation days (43%); only 5 observation days were missing any description of pain (7%). The count of different positive nurse behaviors was positively associated with the absence of reported pain (b=0.436, SE=0.136, z=3.21, p=.001) and remained positively associated when all covariates were incorporated into the model (b=0.276, SE=0.108, z=2.55, p=.011). The count of different positive patient behaviors was not associated with the absence of reported pain (b=0.097, SE=0.168, z=0.58, p=.563).

Patients were calm for 93 of the 152 observation sessions (61%). Eight patients (21%) had some degree of sedation or agitation for 3 or more observation sessions. Count of different positive patient behaviors was associated with the patient being calm (unadjusted: b=0.488, SE=0.144, z=3.39, p<.001 and adjusted: b=0.505, SE=0.143, z=3.53, p<.001). When controlling for the significant covariates of delirium and LOC, the association between count of different positive patient behaviors and the probability of the patient being calm remained (b=0.504, SE= 0.131, z=3.85, p<.001). In contrast, the count of different positive nurse behaviors was not significantly associated with agitation-sedation (unadjusted: b=0.047, SE=0.102, z=0.46, p=.648; adjusted: b=−0.021, SE=0.122, z-test=−0.18, p=.861).

The mean morphine equivalent for the 76 observation days was 14.93 mg (SD=45.28, Min=0, Max=325.0). Of the 38 patients, 16 patients (42%) received no opioids during the 2 observation days. After the models were adjusted for all the covariates, the count of different positive nurse behaviors and the count of different positive patient behaviors were not significantly associated with opioid use (b=−4.939, SE= 2.606, z=−1.90, p=.067; b=−4.176, SE= 2.986, z=−1.40, p=.172, respectively). The mean benzodiazepine equivalent for the 76 observation days was 0.25 mg (SD=0.76, Min=0, Max=4). Of the 38 patients, 29 (76%) did not receive any benzodiazepines. After the models were adjusted for all the covariates, the count of different positive nurse behaviors and the count of different positive patient behaviors were not significantly associated with benzodiazepine use (b=−0.016, SE=0.036, z=−0.44, p=.660, b=0.001, SE=0.042, z=0.02, p=.980, respectively).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we described nurse and patient interaction behaviors and how AAC use impacted communication between nurses and nonspeaking critically ill older adults and explored the association between nurse and patient interaction behaviors and nursing care quality indicators. Our results showed that 1) there were positive associations between positive nurse and patient interaction behaviors, 2) patient unaided AAC strategy use was associated with the count of different positive nurse behaviors, 3) patient individual unaided AAC strategies tended to co-occur with positive nurse behaviors, 4) the count of nurse positive behaviors was associated with pain management, and 5) the count of patient positive behaviors was associated with sedation level.

On average, nurses used 5 different positive interaction behaviors and patients utilized 3 different positive behaviors during an observation session. An increase in positive nurse interaction behaviors was associated with an increase in positive patient behaviors. Our findings support previous research conducted by Salyer and Stuart (1985) demonstrating that positive nurse behaviors yield positive patient behaviors and provide further evidence that nurses have the ability to influence the tone of communication with ICU patients. Although a three minute sham session was conducted to help desensitize the nurses to the presence of the camera prior to study data collection, the presence of the camera may have influenced the types of behaviors the nurses utilized during the observation. An orientation period prior to each observation (Salyer & Stuart, 1985) could have been used as an alternative method to help the nurse become accustomed to the camera but the nature of nurse-patient interactions in the ICU are typically brief, lasting only 3–5 minutes (Ashworth, 1980; Bergbom-Engberg & Haljamae, 1993; Salyer & Stuart, 1985), which would make implementing this method difficult.

Patients most often used unaided AAC strategies, e.g., head nods, non-verbal but communicative action, gestures, and mouthing, consistent with previous research (Menzel, 1998; Thomas & Rodriguez, 2011). In addition, most patients utilized more than one strategy during an observation session, consistent with prior reports (Fried-Oken, Howard, & Stewart, 1991; Happ, Roesch, et al., 2004). An increased use of patient unaided AAC strategies was associated with increased positive nurse behaviors.

Our observations identified several unaided AAC strategies that tended to co-occur with positive nurse behaviors. To our knowledge, we are the first to demonstrate a co-occurrence of unaided AAC strategies and positive nurse behaviors (see Table 5). Critical care nurses are in a position to help improve patient communication by guiding them to try and use multiple unaided AAC strategies to express their needs. Due to limited use of low and high-tech AAC strategies, a larger sample or longer observation segments where such techniques were readily available would be needed to evaluate whether there is an association between low and high tech AAC strategies and interaction behaviors.

The results of this study demonstrated an association between nurse interaction behaviors and pain reporting. The count of different positive nurse behaviors was associated with the probability that the patient had no reported pain. In respect to sedation level, the count of positive patient behaviors was associated with the patient being calm. Calm patients also tended to use more unaided AAC strategies. Because our study did not test these associations using an experimental design, more work needs to be done to determine direction of the relationship and causation. It is important to note that we did control for the presence of delirium in the analyses because prior work has demonstrated that delirium can impact communication; particularly the initiation of symptom communication (Tate et al., 2013).

Finally, there was no association between the interaction behaviors and restraint use and sedation use. The lack of an association between restraint use and negative patient behaviors may be related to the relatively low incidence and lack of variability in both variables. As for sedation use, it is important to note that only 58% of patients received opioids during the observation period and even smaller percent of patients received benzodiazepines, which may be related to the fact that these patients were at a later stage in the critical illness trajectory. In this study, the majority of the patients observed were mechanically ventilated through a tracheostomy and were chronically critically ill (Nelson, Cox, Hope, & Carson, 2010) with a mean of 17 days intubation prior to the study, which may have contributed to the limited use of opioids and benzodiazepines. Previous research has demonstrated that critically ill patients who receive a tracheostomy tend to require less continuous IV sedation, spend less time heavily sedated, and are more autonomous (Nieszkowska et al., 2005), which is consistent with our findings.

Limitations

The patients in this study were older, recruited following an extended ICU stay and therefore representative of the chronically, critical ill population (Carson & Bach, 2002). Results of this study may not be generalizable to patients who are earlier on in their care trajectory or those younger than 60 years of age. While all patients could use unaided AAC strategies, not all patients had access to low and high tech AAC devices. The study was also secondary in nature so we were limited to the data available in the medical record. Pain is under-recognized in older adults (Gelinas & Johnston, 2007), which would not be captured in the medical record abstraction. Further, research in the area of interaction behaviors and nursing care quality indicators should include larger, prospective samples where low and high technology devices are more readily accessible to all patients.

Finally, one of the main limitations of this study is that behaviors were measured as any occurrence during the observation session. While Salyer and Stuart (1985) tallied the number of behaviors and reactions used during an observation period, we chose to measure the variables at the session level because determining when certain behaviors cease and another begins is imprecise. For example, when evaluating behaviors such as smiling or laughing, it can be difficult to discretely and reliably identify what constitutes an endpoint for these behaviors. Behaviors such as smiling or laughing were not included in Salyer and Stuart’s work (1985). A count of individual behaviors within each session could have provided more robust data. It is important to note that even at this aggregated level of measurement, we were still able to demonstrate the tendency of individual behaviors to co-occur with individual unaided AAC strategies (see Table 5).

CONCLUSION

Our findings provide supportive evidence that nurses’ behaviors can significantly impact communication. Our findings highlight individual interaction behaviors that critical care nurses can incorporate into daily care interactions for mechanically ventilated patients and AAC strategies that can be used to guide patients to utilize to facilitate communication. In addition, the intentional use of positive interactions by the nurse, such as touching, and smiling, may encourage patients to engage in communication and help establish a therapeutic nurse-patient relationship. Further research should include large sample sizes in order to evaluate other quality of care indicators, such as device disruption, and younger populations to determine if the results are generalizable to other age groups.

Table 3.

Individual Interaction Behaviors Across All 4 Sessions (Nurse-Patient Dyad n=38)

| Mean±SD | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Nurse Behavior | |||

|

| |||

| Proximity with Speech | 3.76±0.59 | 2 | 4 |

| Visual Contact | 3.45±0.89 | 1 | 4 |

| Social Politeness | 2.95±1.06 | 0 | 4 |

| Augments | 2.89±1.03 | 0 | 4 |

| Physical Contact | 1.89± 1.23 | 0 | 4 |

| Praising | 1.55±1.31 | 0 | 4 |

| Preparatory Information | 1.32±1.09 | 0 | 3 |

| Smiling | 0.92±1.12 | 0 | 4 |

| Sharing | 0.92±0.85 | 0 | 3 |

| Laughing | 0.74±1.13 | 0 | 4 |

| Expanded Preparatory Information | 0.45±0.69 | 0 | 3 |

| Preparatory Information (Brief Delay) | 0.42±0.68 | 0 | 2 |

| Expanded Preparatory Information (Brief Delay) | 0.21±0.47 | 0 | 2 |

| Modeling | 0.11±0.31 | 0 | 1 |

|

| |||

| Negative Nurse Behaviors | |||

|

| |||

| Disapproving | 0.03±0.16 | 0 | 1 |

| Yelling | 0.00±0.00 | 0 | 0 |

| Ignoring | 0.00±0.00 | 0 | 0 |

|

| |||

| Positive Patient Behaviors | |||

|

| |||

| Instruction Following | 3.42±0.95 | 0 | 4 |

| Acceptance | 2.55±1.25 | 0 | 4 |

| Maintaining Attention | 1.95±1.37 | 0 | 4 |

| Visual Contact | 1.87±1.30 | 0 | 4 |

| Requests | 1.32±1.19 | 0 | 4 |

| Smiling | 0.79±1.12 | 0 | 4 |

| Physical Contact | 0.24±0.59 | 0 | 2 |

| Laughing | 0.13±0.41 | 0 | 2 |

| Praise | 0.16±0.49 | 0 | 2 |

|

| |||

| Negative Patient Behaviors | |||

|

| |||

| Ignoring | 0.16±0.37 | 0 | 1 |

| Disgust | 0.08±0.27 | 0 | 1 |

| Disagreement | 0.05±0.23 | 0 | 1 |

Acknowledgments

Funding: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01-HD043988) (PI: M. Happ), National Institute of Nursing Research (K24-NR010244) (PI: M. Happ), National Institute of Nursing Research (F31-NR012856) (PI: M. Nilsen), National Institute of Nursing Research (T32-NR008857) (PI: J. Erlen)

The authors thank Judith Tate, PhD, RN, and Dana Divirgilio, MPH, for providing guidance and assistance with the dataset. In addition, they extend a special thanks to Rebecca Nock, BSN, RN, for performing the second coding of the nurse and patient interaction behaviors and medical record abstraction.

Footnotes

No conflict of interest to note.

Contributor Information

Marci Nilsen, T32 Postdoctoral Fellow, University of Pittsburgh, School of Nursing.

Susan M. Sereika, Professor, University of Pittsburgh, School of Nursing.

Leslie A. Hoffman, Professor Emeritus, University of Pittsburgh, School of Nursing.

Amber Barnato, Associate Professor, University of Pittsburgh, School of Medicine.

Heidi Donovan, Associate Professor, University of Pittsburgh, School of Nursing.

Mary Beth Happ, Distinguished Professor, The Ohio State University, College of Nursing.

References

- Alasad J, Ahmad M. Communication with critically ill patients. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2005;50(4):356–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashworth Pat. Care to Communicate: An Investigation into Problems of Communication Between Patients and Nurses in Intensive Therapy Units. London: Royal College of Nursing of United Kingdom; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett Gillian, Blais Regis, Tamblyn Robyn, Clermont Richard J, MacGibbon Brenda. Impact of patient communication problems on the risk of preventable adverse events in acute care settings. CMAJ Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2008;178(12):1555–1562. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.070690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergbom-Engberg I, Haljamae H. The communication process with ventilator patients in the ICU as perceived by the nursing staff. Intensive & Critical Care Nursing. 1993;9(1):40–47. doi: 10.1016/0964-3397(93)90008-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beukelman DR, Garrett KL, Yorkston KM. Augmentative Communication Strategies for adults with acute or chronic medical conditions. Baltimore, MD: Paul H Brookes Publishing Co; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Beukelman DR, Mirenda P. Augmentative and alternatie ommunication: Supporting children and adults with complex communication needs. Baltimore, MD: Paul H Brookes Publishing Co; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cammarano WB, Drasner K, Katz JA. Pain control sedation and use of muscle relaxants. In: Hall J, Schmidt G, Wood L, editors. Principles of Critical Care. 2. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1998. pp. 90–97. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll SM. Silent, slow lifeworld: the communication experience of nonvocal ventilated patients. Qualitative Health Research. 2007;17(9):1165–1177. doi: 10.1177/1049732307307334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson SS, Bach PB. The epidemiology and costs of chronic critical illness. Crit Care Clin. 2002;18(3):461–476. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0704(02)00015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de los Ríos Castillo JL, Sánchez-Sosa J. Well-being and medical recovery in the critical care unit: the role of the nurse-patients interaction. Salud Mental. 2002;25(2):21–30. [Google Scholar]

- de Wit M, Wan SY, Gill S, Jenvey WI, Best AM, Tomlinson J, Weaver MF. Prevalence and impact of alcohol and other drug use disorders on sedation and mechanicaly ventilations: a retrospective study. BMC Anethesiology. 2007;7(3) doi: 10.1186/1471-2253-7-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit Marjolein, Gennings Chris, Jenvey Wendy I, Epstein Scott K. Randomized trial comparing daily interruption of sedation and nursing-implemented sedation algorithm in medical intensive care unit patients. Critical Care (London, England) 2008;12(3):R70. doi: 10.1186/cc6908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois MJ, Bergeron N, Dumont M, Dial S, Skrobik Y. Delirium in an intensive care unit: a study of risk factors. Intensive Care Medicine. 2001;27(8):1297–1304. doi: 10.1007/s001340101017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert DA, Heckerling PS. Communication disabilities among medical inpatients. New England Journal of Medicine. 1998;339(4):272–273. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807233390416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ely EW, Inouye SK, Bernard GR, Gordon S, Francis J, May L, Dittus R. Delirium in mechanically ventilated patients: validity and reliability of the confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit (CAM-ICU) JAMA. 2001;286(21):2703–2710. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.21.2703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ely EW, Margolin R, Francis J, May L, Truman B, Dittus R, Inouye SK. Evaluation of delirium in critically ill patients: validation of the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU) Critical Care Medicine. 2001;29(7):1370–1379. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ely EW, Shintani A, Truman B, Speroff T, Gordon SM, Harrell FE, Jr, Dittus RS. Delirium as a predictor of mortality in mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;291(14):1753–1762. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.14.1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ely EW, Truman B, Shintani A, Thomason JWW, Wheeler AP, Gordon S, Bernard GR. Monitoring sedation status over time in ICU patients: reliability and validity of the Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS) JAMA. 2003;289(22):2983–2991. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.22.2983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogel JF, Berkman CS, Merkel C, Cranston T, Leipzig RM. Efficient and accurate measurement of physical restraint use in acute care. Care Management Journals. 2009;10(3):100–109. doi: 10.1891/1521-0987.10.3.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried-Oken M, Howard JM, Stewart SR. Feedback on AAC intervention from adults who are temporarily unable to speak. Augmentative and Alternative Communication. 1991;7:43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Gelinas Celine, Johnston Celeste. Pain assessment in the critically ill ventilated adult: validation of the Critical-Care Pain Observation Tool and physiologic indicators. Clinical Journal of Pain. 2007;23(6):497–505. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31806a23fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall DS. Interactions between nurses and patients on ventilators. American Journal of Critical Care. 1996;5(4):293–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansebo Görel, Kihlgren Mona. Carers’ interactions with patients suffering from severe dementia: a difficult balance to facilitate mutual togetherness. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2002;11(2):225–236. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2002.00601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Happ MB, Garrett K, Tate JA, Divirgilio D, Houze M, Demerci J, Sereika SM. Effect of a multi-level intervention on nurse-patient communication in the intensive care unit: Results of the SPEACS trial. Heart & Lung. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2013.11.010. (Accepted) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Happ MB. Using a best practice approach to prevent treatment interference in critical care. Progress in Cardiovascular Nursing. 2000;15(2):58–62. doi: 10.1111/j.0889-7204.2000.080394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Happ MB, Barnato AE. SPEACS-2: Improving Patient Communication and Quality Outcomes in the ICU: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Interdisciplinary Nursing Quality Research Initiative (INQRI) 2009–2011. [Google Scholar]

- Happ MB, Baumann BM, Sawicki J, Tate J, George EL, Barnato AE. SPEACS-2: intensive care unit “communication rounds” with speech language pathology. Geriatric Nursing. 2010;31(3):170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Happ MB, Garrett K, Thomas DD, Tate J, George E, Houze M, Sereika S. Nurse-Patient Communication Interactions in the Intensive Care Unit. American Journal of Critical Care. 2011;20(2):e28–e40. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2011433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Happ MB, Roesch T, Kagan SH, Garrett KL, Farkas N. Aging and the use of electronic speech generating devices in the hospital setting. New York: Nova Science Publishing Inc; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Happ MB, Roesch TK, Garrett K. Electronic voice-output communication aids for temporarily nonspeaking patients in a medical intensive care unit: a feasibility study. Heart & Lung. 2004;33(2):92–101. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Happ MB, Sereika S, Garrett K, Tate J. Use of the quasi-experimental sequential cohort design in the Study of Patient-Nurse Effectiveness with Assisted Communication Strategies (SPEACS) Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2008;29(5):801–808. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Happ MB, Tuite P, Dobbin K, DiVirgilio-Thomas D, Kitutu J. Communication ability, method, and content among nonspeaking nonsurviving patients treated with mechanical ventilation in the intensive care unit. American Journal of Critical Care. 2004;13(3):210–218. quiz 219–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins Patricia A, Daly Barbara J. Research methodology issues related to interviewing the mechanically ventilated patient. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 1999;21(6):773–784. doi: 10.1177/01939459922044180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettunen Tarja, Poskiparta Marita, Karhila Päivi. Speech practices that facilitate patient participation in health counselling-A way to empowerment? Health Education Journal. 2003;62(4):326–340. [Google Scholar]

- Knaus WA, Wagner DP, Draper EA, Zimmerman JE, Bergner M, Bastos PG, et al. The APACHE III prognostic system. Risk prediction of hospital mortality for critically ill hospitalized adults. Chest. 1991;100(6):1619–1636. doi: 10.1378/chest.100.6.1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacy CF, Armstrong LL, Goldman MP, Lance LL. Lexi-Comp’s Drug Information Handbook. Hudson, OH: Lexi-Comp; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lat Ishaq, McMillian Wes, Taylor Scott, Janzen Jeff M, Papadopoulos Stella, Korth Laura, Burke Peter. The impact of delirium on clinical outcomes in mechanically ventilated surgical and trauma patients. Critical Care Medicine. 2009;37(6):1898–1905. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819ffe38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menzel LK. Factors related to the emotional responses of intubated patients to being unable to speak. Heart & Lung. 1998;27(4):245–252. doi: 10.1016/s0147-9563(98)90036-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miglietta MA, Bochicchio G, Scalea TM. Computer-assisted communication for critically ill patients: a pilot study. The Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection, and Critical Care. 2004;57(3):488–493. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000141025.67192.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison RS, Meier DE, Fischber D, Moore C, Degenholtz H, Litke A, Siu AL. Improving the management of pain in hospitalized adults. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006;166:1033–1039. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.9.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson Judith E, Cox Christopher E, Hope Aluko A, Carson Shannon S. Chronic critical illness. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2010;182(4):446. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201002-0210CI. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieszkowska Ania, Combes Alain, Luyt Charles-Edouard, Ksibi Hichem, Trouillet Jean-Louis, Gibert Claude, Chastre Jean. Impact of tracheotomy on sedative administration, sedation level, and comfort of mechanically ventilated intensive care unit patients*. Critical care medicine. 2005;33(11):2527–2533. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000186898.58709.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen ML, Happ MB, Donovan H, Barnato A, Hoffman L, Sereika SM. Adaptation of a Communication Interaction Behavior Instrument for use in Mechanically Ventilated, Nonvocal Older Adults. Nursing Research. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0000000000000012. (In press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen ML, Sereika S, Happ MB. Nurse and Patient Characteristics Associated with Duration of Nurse Talk during Patient Encounters in ICU. Heart & Lung. 2013;42(1):5–12. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen ML, Sereika S, Happ MB. Nurse and Patient Characteristics Associated with Duration of Nurse Talk during Patient Encounters in ICU. Heart & Lung. 2013;42(1):5–12. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park EK, Song M. Communication barriers perceived by older patients and nurses. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2005;42(2):159–166. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patak L, Gawlinski A, Fung NI, Doering L, Berg J. Patients’ reports of health care practitioner interventions that are related to communication during mechanical ventilation. Heart & Lung. 2004;33(5):308–320. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope DS, Gallun FJ, Kampel S. Effect of hospital noise on patients’ ability to hear, understand, and recall speech. Research in Nursing & Health. 2013;36(3):228–241. doi: 10.1002/nur.21540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rier D. The missing voice of the critically ill: A medical sociologist’s first-hand account. Sociology of Health and illness. 2000;22(1):68–93. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez Carmen S, VanCott Mary Lou. Speech Impairment in the Postoperative Head and Neck Cancer Patient: Nurses’ and Patients’ Perceptions. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15(7):897–911. doi: 10.1177/1049732305278903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saigh O, Triola MM, Link N. Failure of an electronic medical record tool to improve pain assessment documentation. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;(21):185–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00330.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salyer J, Stuart BJ. Nurse-patient interaction in the intensive care unit. Heart & Lung. 1985;14(1):20–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sessler CN, Gosnell MS, Grap MJ, Brophy GB, O’Neal PV, Keane A, Elswick RK. The Richmond Agitation–Sedation Scale: validity and reliability in adult intensive care unit patients. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2002;166:1338–1344. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2107138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soukup Jens, Selle Antje, Wienke Andreas, Steighardt Jorg, Wagner Nana-Maria, Kellner Patrick. Efficiency and safety of inhalative sedation with sevoflurane in comparison to an intravenous sedation concept with propofol in intensive care patients: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2012;13(1):135. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-13-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stovsky B, Rudy E, Dragonette P. Comparison of two types of communication methods used after cardiac surgery with patients with endotracheal tubes. Heart & Lung. 1988;17(3):281–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tate JA, Sereika S, Divirgilio D, Nilsen M, Demerci J, Campbell G, Happ MB. Symptom Communication during Critical Illness: The impact of age, delirium, and delirium presentation. Journla of Gerontological Nurisng. 2013;39(8):28–38. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20130530-03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teasdale G, Jennett B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet. 1974;2:81–84. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)91639-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Joint Commission. The Joint Commission: New and Revised Standards and EPs for Patient-Center Commuication- Hospital Accreditation Program. 2010 Retrieved July 23, 2010, from http://www.jointcommission.org/NR/rdonlyres/26D4ABD6-3489-4101-B397-56C9EF7CC7FB/0/Post_PatientCenteredCareStandardsEPs_20100609.pdf.

- Thomas Loris A, Rodriguez Carmen S. Prevalence of sudden speechlessness in critical care units. Clinical Nursing Research. 2011;20(4):439–447. doi: 10.1177/1054773811415259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner Douglas P, Knaus William A, Harrell Frank E, Zimmerman Jack E, WATIS CHARLES. Daily prognostic estimates for critically ill adults in intensive care units: results from a prospective, multicenter, inception cohort analysis. Critical care medicine. 1994;22(9):1359–1372. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199409000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinert CR, Chlan L, Gross C. Sedating critically ill patients: factors effecting nurses’ delivery of sedative therapy. American Journal of Critical Care. 2001;10(3):156–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wunsch H, Linde-Zwirble WT, Angus DC, Hartman ME, Milbrandt EB, Kahn JM. The epidemiology of mechanical ventilation use in the United States. Critical Care Medicine. 2010;38(10):1947–1953. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181ef4460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yorkston Kathryn M, Bourgeois Michelle S, Baylor Carolyn R. Communication and aging. Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation Clinics of North America. 2010;21(2):309–319. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]