Abstract

Parasitic nematodes cause diseases of major economic importance in animals. Key representatives are species of Dictyocaulus (= lungworms), which cause bronchitis (= dictyocaulosis, commonly known as “husk”) and have a major adverse impact on the health of livestock. In spite of their economic importance, very little is known about the immunomolecular biology of these parasites. Here, we conducted a comprehensive investigation of the adult transcriptome of Dictyocaulus filaria of small ruminants and compared it with that of Dictyocaulus viviparus of bovids. We then identified a subset of highly transcribed molecules inferred to be linked to host-parasite interactions, including cathepsin B peptidases, fatty-acid and/or retinol-binding proteins, β-galactoside-binding galectins, secreted protein 6 precursors, macrophage migration inhibitory factors, glutathione peroxidases, a transthyretin-like protein and a type 2-like cystatin. We then studied homologs of D. filaria type 2-like cystatin encoded in D. viviparus and 24 other nematodes representing seven distinct taxonomic orders, with a particular focus on their proposed role in immunomodulation and/or metabolism. Taken together, the present study provides new insights into nematode-host interactions. The findings lay the foundation for future experimental studies and could have implications for designing new interventions against lungworms and other parasitic nematodes. The future characterization of the genomes of Dictyocaulus spp. should underpin these endeavors.

Keywords: Lungworms, Dictyocaulus spp, Transcriptome, Host-parasite interactions

1. Introduction

Parasitic nematodes cause diseases of major economic importance in animals. Particularly significant nematodes are members of the order Strongylida, including the Ancylostomatoidea, Strongyloidea, Trichostrongyloidea and Metastrongyloidea (Anderson, 2000). The latter superfamily includes pathogens of livestock such as cattle and small ruminants (sheep and goats) (Panuska, 2006). Important representatives are species of Dictyocaulus (= lungworms); these nematodes live in the bronchi and bronchioles, and cause bronchitis (i.e., dictyocaulosis, commonly known as ‘husk’), particularly in young animals (Panuska, 2006; Holzhauer et al., 2011).

Dictyocaulus spp. of ruminants have direct life cycles (Anderson, 2000; Panuska, 2006). Adults live in the bronchi and trachea. Embryonated eggs are coughed up, swallowed and hatch in the small intestine. L1s are excreted in faeces into the environment. Under suitable environmental conditions, L1s moult to the L2s and then L3s. The rate of development of the larvae to the L3 stage depends on temperature and humidity but can be achieved in a week. Infective L3s actively move from faeces to herbage and are ingested by the grazing animal; they can also be disseminated via the sporangia of particular fungi (Panuska, 2006). Following ingestion, L3s exsheath in the small intestine, penetrate the intestinal wall and enter the mesenteric lymph nodes. Here, larvae develop, moult and then migrate via the thoracic duct, anterior vena cava, heart and pulmonary arteries to the lungs (Panuska, 2006). They penetrate the walls of the alveoli and enter the airways. Here, the larvae become sexually mature, dioecious adults approximately 4 weeks following infection with L3s, after which the females produce embryonated eggs. Under particular conditions, larvae can undergo arrested development (hypobiosis) in the host animal.

The life cycles of Dictyocaulus spp. are remarkably similar, yet there are biological differences, particularly with regard to host preference (Panuska, 2006). Dictyocaulus viviparus infects cattle, other bovids and cervids, whereas Dictyocaulus filaria infects sheep and goats (the latter being more susceptible) (Panuska, 2006), and immunity to homologous reinfection is strong (reviewed by Panuska, 2006; Foster and Eisheikha, 2012). Interestingly, D. filaria can establish in the lungs of calves - disease has been reported to develop, but patent infection does not establish, although some degree of immunity against challenge infection with infective L3s of D. viviparus has been shown (Parfitt and Sinclair, 1967; Panuska, 2006).

Although there is clear evidence that cattle elicit mixed Th1/Th2 responses, with elevated (Th2-dependent) IgE and eosinophil levels against D. viviparus (reviewed by Foster and Eisheikha, 2012), no detailed information is available on the immunobiology of D. filaria. Nonetheless, it is known that D. filaria can infect calves (Partfitt and Sinclair, 1967), but D. viviparus does not infect sheep, which suggests a difference in host permissiveness, such that D. filaria might induce an immune response that is distinct from that induced by D. viviparus. Molecular studies of other parasitic nematodes (reviewed by Cantacessi et al., 2009; Hewitson et al., 2009; Klotz et al., 2011) have indicated that key groups of molecules, such as SCP/Tpx-1/Ag5/PR-1/Sc7 (SCP/TAPS) proteins, transthyretin-like proteins and type 2-like cystatins, are intimately involved in the parasite-host interplay. However, information is lacking for lungworms. Clearly, improving our understanding of the differences/similarities between Dictyocaulus spp. at the molecular level, through comparative transcriptomic analyses, could elucidate their immunobiology and the pathogenesis of disease and might also assist in guiding future interventions against them.

Advanced genomic and transcriptomic sequencing technologies (e.g., RNA-seq; Illumina) enable detailed molecular analyses and comparisons (Allen et al., 2011; Cantacessi et al., 2012; Li et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2012; Heizer et al., 2013; Mangiola et al., 2013). Thus far, using RNA-seq, transcriptomic analyses of life stages and/or sexes of D. viviparus have been conducted (Cantacessi et al., 2011a; Strube et al., 2012), but there have been no comparative analyses between closely related species such as D. viviparus and D. filaria. In the present study, we characterized the transcriptome of the adult stage of D. filaria and qualitatively compared it with that of D. viviparus, focusing on highly transcribed key molecules inferred to be involved in parasite-host interactions.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Production and procurement of parasite material, RNA isolation and sequencing

Adult specimens of D. filaria (n = 20; mixed sexes) were collected from the trachea and bronchi of an infected sheep in Victoria, Australia, following a routine autopsy; adults of D. viviparus (n = 20; mixed sexes) were collected from the trachea of an infected cow from Hanover, Germany (permit AZ 33-42502-06/1160; ethics commission of the Lower Saxony State Office for Consumer Protection and Food Safety). The worms were washed extensively in PBS and frozen at −70 °C. For each species, total RNA was extracted, purified and quantified spectrophotometrically (NanoDrop ND-1000 UV-VIS v.3.2.1). RNA libraries were prepared and paired-end sequenced using Illumina technology (Bentley et al., 2008), as described previously (Cantacessi et al., 2011b).

2.2. Curation of RNA-seq data and assembly of transcriptomes

The RNA-seq data sets for D. filaria (deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) sequence read archive - www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Traces/sra/; accession number SRP032224) and D. viviparus (accession numbers SRR1021573 and SRR1021571) were filtered for PHRED quality (< 30), and sequencing adapters removed using the program Trimmomatic (Lohse et al., 2012). The redundancy among reads was reduced using the program khmer (https://khmer.readthedocs.org), in order to obtain a read coverage of ≤ 20. Each non-redundant data set was assembled into contigs using the program Oases v.0.1.18 (Schulz et al., 2012) using a combination of k-mer lengths (i.e. 19–51 for D. filaria; 19–69 for D. viviparus) and read-coverage cut-offs (i.e. 5–20 for D. filaria; 3–20 for D. viviparus). Using this approach, 240 and 425 assemblies were produced for D. filaria and D. viviparus, respectively. For each assembly, five parameters were determined: (i) sequence redundancy - calculated as the number of contigs with significant similarity to those in the same assembly (BLASTn, E-value cut-off: ≤ 10−05) (Altschul et al., 1997); (ii) average contig length; (iii) number of open reading frames (ORFs) of ≥ 100 nucleotides, encoded in each contig; (iv) portion of the paired-end raw read data set that mapped to the assembled transcriptome using the program BWA (Li and Durbin, 2009) - employing a mismatch probability threshold of 0.05 and a minimum fraction gap opening of 3; the program flagstat (included in the SAMtools package; (Li et al., 2009) was used to undertake statistical analyses; and (v) total number of contigs. The transcriptomes assembled for adult D. filaria and D. viviparus with the most similar parameters (i–v) were selected for direct, comparative analyses.

Sequences that did not share amino acid (aa) sequence homology (BLASTp, E-value cut-off: ≤ 10−05) to those of other nematodes but were homologous to Ovis aries (sheep for D. filaria), Bos taurus (cattle for D. viviparus), bacteria, viruses and/or fungi were identified and removed from these two transcriptome data sets. Furthermore, viral-like retrotransposons were also identified and removed from the sequence data according to: (i) results from InterProScan (Zdobnov and Apweiler, 2001), using selected keywords; and (ii) an homology search against the database RepBase (Buisine et al., 2008) using the BLASTx algorithm (E-value cut-off: ≤ 10−05). Mitochondrial DNA and rRNA sequences were detected and removed using BLASTx and BLASTn algorithms (Altschul et al., 1997) (E-value cut-off: ≤ 10−05) employing sequence data sets for nematodes available in NCBI. All remaining sequences of ≥ 150 bases were subjected to protein predictions using getorf (Olson, 2002; using the –table=1 and –find=1 options) and individual ORFs selected using an established workflow (Mangiola et al., 2013). Sequence redundancy was removed by protein clustering using CD-HIT (Fu et al., 2012) using an aa sequence identity threshold of 0.95. The estimated completeness of each non-redundant transcriptome was assessed for the presence of conserved proteins shared among metazoan organisms using the program CEGMA (Parra et al., 2007).

2.3. Functional annotation of transcriptomes

Each curated, non-redundant transcriptome was functionally annotated using an established workflow (Mangiola et al., 2013). Predicted proteins were compared (BLASTp, E-value cut-off: ≤10−05) with those available in the following databases: SwissProt (Magrane and Consortium, 2011), WormBase (Caenorhabditis elegans) (Yook et al., 2012), MEROPS (peptidase and peptidase inhibitors) (Rawlings, 2009), Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) (Kanehisa and Goto, 2000) and SPD (secreted proteins) (Chen et al., 2005). Conserved domains and Gene Ontology (GO) (Dimmer et al., 2012) annotations were identified by InterProScan (cf. subsection 2.2). Signal peptide and transmembrane domains were predicted for individual protein sequences using the program Phobius (Kall et al., 2004).

Excretory/secretory (ES) proteins were inferred from transcripts using Phobius (Kall et al., 2004); proteins encoding a predicted signal peptide domain but not a transmembrane domain, and sharing homology (BLASTp; E-value < 1e−5) to proteins an in-house, curated database of ES proteins of C. elegans (from SwissProt) and parasitic nematodes (Hartman et al., 2001; Basavaraju et al., 2003; Hartmann and Lucius, 2003; Yatsuda et al., 2003; Zhan et al., 2003; Robinson and Connolly, 2005; Craig et al., 2006; Gregory and Maizels, 2008; Hewitson et al., 2008, 2009; Moreno and Geary, 2008; Ranjit et al., 2008; Bath et al., 2009; Cantacessi et al., 2009; Cuellar et al., 2009; Mulvenna et al., 2009; Smith et al., 2009; Klotz et al., 2011; Saeed et al., 2013).

2.4. Analysis of transcript abundance

For each non-redundant transcriptome, the abundance of a transcript was determined by calculating the number of sequence fragments (i.e. Illumina reads) mapped per kilobase of transcript per million total sequence fragments mapped (FPKM) using BWA (Li and Durbin, 2009), SAMtools (Li et al., 2009) and custom Python scripts. Transcripts were ranked according to their highest to lowest FPKM value, and the top 10% of transcripts were selected to represent the most highly transcribed genes.

2.5. Analysis of cystatins encoded in Dictyocaulus spp. and other nematodes

To investigate type 2-like cystatins, full-length sequences were identified (BLASTp or tBLASTn, E-value ≤ 10−05) in the transcriptomes of D. filaria and D. viviparus, and in the transcriptomes and/or genomes of a range of key nematodes representing different orders. Amino acid sequences were selected as homologs, if they: (i) were predicted to encode one or more cystatin I25 inhibitor domains (InterPro proteinase inhibitor I25, cystatin-like domains IPR000010, IPR018073 and IPR020381); (ii) contained a predicted signal peptide domain; (iii) had four or more conserved motifs necessary for the inhibition of papain-like (MEROPS C01 family) and/or asparaginyl endopeptidase-like peptidases (MEROPS C13 family) (Gregory and Maizels, 2008); and (iv) encoded a single proteinase inhibitor I25 domain (Abrahamson et al., 2003). All homologous sequences were then aligned using MAFFT (Katoh and Standley, 2013) and manually verified. To assess evolutionary relationships between or among the sequences, phylogenetic trees were constructed using Bayesian inference (BI) (MrBayes; Ronquist et al., 2012), employing the ‘Whelan and Goldman’ aa model (Whelan and Goldman, 2001) and using the final 75% of 2.3 million Markov chain Monte Carlo iterations (Metropolis et al., 1953; Hastings, 1970; Geyer, 1992) to construct a 50% majority rule tree, with the nodal support for each clade expressed as a posterior probability value (pp).

3. Results

3.1. Characterisation of the transcriptome of adult D. filaria - comparisons with D. viviparus

Totals of 29,405,140 and 120,808,829 paired-end reads were used to assemble the transcriptomes of D. filaria (16,987 contigs; k-mer value: 25; read coverage cut-off: 10) and D. viviparus (21,230 contigs; k-mer value: 51; read coverage cut-off: 8), respectively (Table 1). The transcriptomes of adult D. filaria and D. viviparus were inferred to encode 13,271 and 15,642 non-redundant proteins, respectively (Table 1), including > 80% of 248 core eukaryotic proteins (based on CEGMA). In total, 9,113 (69.0%) and 10,654 (68.1%) of all proteins predicted were annotated (E-value cut-off of ≤ 10−05) for D. filaria and D. viviparus, respectively (Table 1), with most (8,065 for D. filaria, and 8,929 for D. viviparus) having homology to non-hypothetical genes or protein sequences present in the NCBI non-redundant (nr) and SwissProt databases. For D. filaria, a total of 7,944 predicted proteins could be classified into 40 unique protein KEGG classes, and 4,553 into 288 unique KEGG pathways. For this species, 7,164 conserved domains were identified, allowing 5,431 genes to be assigned 1,537 unique GO terms. For D. viviparus, a total of 8,834 predicted proteins could be classified into 45 unique protein KEGG classes, and 4,875 into 306 unique KEGG pathways. For this species, 7,888 conserved domains were identified, allowing 6,032 genes to be assigned 1,748 unique GO terms.

Table 1.

Salient characteristics of the transcriptomic and predicted proteomic data sets for the adult stages of Dictyocaulus filaria and Dictyocaulus viviparus.

| D. filaria | D. viviparus | |

|---|---|---|

| Transcriptome assemblies: | ||

| Total number of reads | 29,405,140 | 120,808,829 |

| Contigs of > 150 nucleotides (mean ± S.D.; range) | 16,987 (1,042.6 ± 1,000.9; 150–14,409) | 21,230 (1,594.9 ± 2,120.0; 150–43,105) |

| Number of reads that mapped to contigs (%) | 23,787,556 (86.7) | 103,122,222 (89.4) |

| Number of non-redundant proteins of > 50 amino acids predicted (mean ± S.D.; range) | 13,271 (295.1± 291.4;50–4,779) | 15,642 (244.1± 267.1;50–7,258) |

| Complete/partial matches to 248 CEGs proteins in % | 81.5/92.7 | 85.1/96.0 |

| Numbers of proteins homologous (BLASTp; E-value cut-off of ≤ 10−5) to entries in various databases (01 Jan and 30 June 2013) (% of predicted proteome): | ||

| NCBI (non-redundant, nr) | 9,116 (68.7) | 8,577 (54.8) |

| SwissProt | 7,211 (54.3) | 6,820 (43.6) |

| MEROPS peptidase | 599 (4.5) | 561 (3.6) |

| MEROPS peptidase inhibitor | 223 (1.7) | 203 (1.3) |

| ChEMBL | 2,947 (22.2) | 2,900 (18.5) |

| Numbers of proteins homologous (BLASTp; E-value cut-off of ≤ 10−5) to entries in KEGG databases (E-value cut-off of ≤ 10−15) (% of predicted proteome; number of conserved KEGG protein classes or pathways): | ||

| KEGG BRITE | 7,944 (59.9; 40) | 8,834 (0.56; 45) |

| KEGG PATHWAY | 4,553 (34.3; 288) | 4,875 (31.1; 306) |

| Numbers of predicted proteins with conserved domains or GO annotations (% of predicted proteome; number of unique InterProScan domains or GO terms): | ||

| InterProScan conserved domains | 5,731 (43.2; 876) | 6,284 (40.2; 973) |

| GO terms | 5,431 (40.9; 1,537) | 6,032 (38.6; 1748) |

| Biological process | 3,298 (24.9; 571) | 3,834 (24.5; 667) |

| Cellular component | 1,860 (14.0; 209) | 2,114 (13.5; 214) |

| Molecular function | 4,710 (35.5; 757) | 5,235 (33.5; 867) |

| Numbers of proteins with a signal peptide, one or more transmembrane domains and predicted to be excreted/secreted (% of predicted proteome): | ||

| Predicted signal peptide | 1,624 (12.2) | 1,470 (9.4) |

| At least one transmembrane domain | 2,904 (21.9) | 4,111 (26.3) |

CEG, conserved eukaryotic genes; GO, gene ontology; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes.

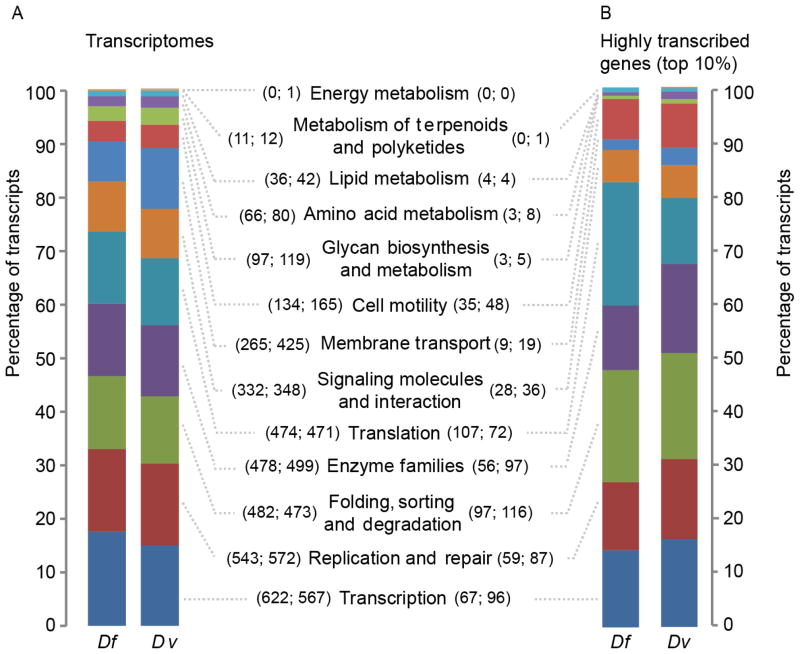

A comparison showed that 9,399 (71.0%) of the 13,271 aa sequences of D. filaria had homologs in D. viviparus; 8,771 (66.1%) had homologs in C. elegans, of which 1,005 were not detected in D. viviparus. Of 2,867 (21.6%) D. filaria sequences, with no homologs detected in either C. elegans or D. viviparus, 396 (3%), had homologs (E-value cut-off: ≤ 10−05) in other nematodes, including Ascaris suum, Haemonchus contortus, Necator americanus, Oesophagostomum dentatum, Trichostrongylus colubriformis and Trichuris suis. The proteins predicted from the transcriptomes of adult D. filaria and D. viviparus were assigned to 13 functional categories (Fig. 1A), with similarity in the numbers of proteins assigned to individual categories. In both transcriptomes, the proportion of highly abundant transcripts classified into different functional groups (Fig. 1B) was similar to that of the whole transcriptome (Fig. 1A); some differences related to translation in D. filaria and enzyme families in D. viviparus (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 1.

Functional annotation of the transcriptomes of adult Dictyocaulus filaria (Df) and Dictyocaulus viviparus (Dv). Bar graphs compare the numbers of transcripts representing different categories of proteins encoded in the transcriptomes (A) and by the top 10% of highly transcribed genes (B). Proteins inferred from the transcripts were annotated by BLASTp (Evalue cut-off: ≤ 10−5) using the Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG) BRITE and an excretory/secretory protein sequence database (see Section 2.3). In parentheses (i.e. (Df; Dv)) are the numbers of inferred proteins of a particular category for each species.

Fig. 2.

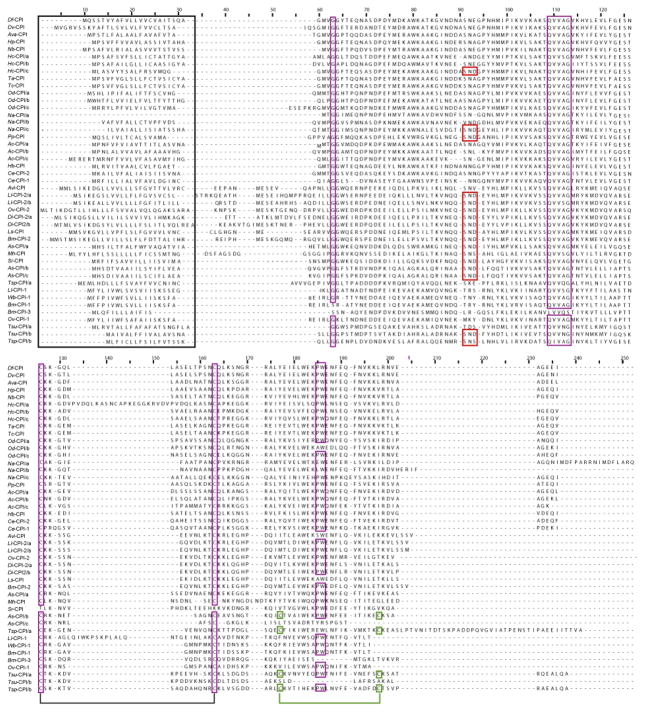

Sequence comparison. Alignment of amino acid sequences of type 2-like cystatins predicted for Dictyocaulus filaria (Df) and Dictyocaulus viviparus (Dv) with those of 24 other species of nematodes (see Table 3) and key structural and functional elements in these sequences. Key elements identified based on the tertiary structure of cystatin from chicken egg white (Bode et al., 1988) are: the signal peptide (outlined in black); residues involved in C1 papain-like peptidase binding (purple) including the N-terminus glycine (position 63; labeled as G in Table 3); the inhibitor domain for C1 papain-like peptidase (positions 113–117; QXVXG); the first, central cysteine disulfide bond (positions 131 and 159); and the C-terminus domain (positions 181 and 182; PW); the second C-terminus cysteine disulfide bond (positions 173 and 194; green); and the motif involved in the binding of the mammalian asparaginyl endopeptidase (SND/SNS; positions 95–97; red). Ac, Ancylostoma caninum; As, Ascaris suum; Ava, Angiostrongylus vasorum; Avi, Acanthocheilonema viteae; Bm, Brugia malayi; Ce, Caenorhabditis elegans; Di, Dirofilaria immitis; Hb, Heterorhabditis bacteriophora; Hc, Haemonchus contortus; Hp, Heligmosomoides polygyrus; Ll, Loa loa; Ls, Litomosoides sigmodontis; Mh, Meloidogyne hapla; Na, Necator americanus; Nb, Nippostrongylus brasiliensis; Od, Oesophagostomum dentatum; Ov, Onchocerca volvulus; Pp, Pristionchus pacificus; Sr, Strongyloides ratti; Ta, Trichostrongylus axei; Tc, Trichostrongylus colubriformis; Tsp, Trichinella spiralis; Tsu, Trichuris suis; Wb, Wuchereria bancrofti.

3.2. Analysis of transcription in D. filaria and D. viviparus

In D. filaria, 286 of 1,327 highly abundant transcripts were predicted to encode ES proteins, of which 220 shared aa sequence homology to proteins in the NCBI nr database. Similarly, 198 of the 1,564 highly abundant transcripts in D. viviparus were predicted to encode ES proteins, of which 173 shared aa sequence homology to proteins in the NCBI nr database. In D. filaria, highly transcribed genes encoded 24 proteins inferred to play a role in modulating the host immune response (Table 2); these molecules included cathepsin B peptidases (n = 7), fatty-acid and/or retinol-binding protein (n = 1), β-galactoside-binding galectins (n = 5), secreted protein 6 precursors (n = 3), macrophage migration inhibitory factors (n = 2), glutathione peroxidases (n = 2), a transthyretin-like protein (n = 1) and a cystatin (n = 1). Homologs of half of these molecules were also highly transcribed in D. viviparus (Table 2). The cystatin was of particular interest, because there is a substantial body of knowledge surrounding its dual role in immunomodulation and metabolism in parasitic nematodes (Hartmann et al., 1997; Dainichi et al., 2001; Manoury et al., 2001; Schonemeyer et al., 2001; Pfaff et al., 2002); immunomodulation appears to relate to (relatively) conserved sequence motifs (Hartmann and Lucius, 2003; Gregory and Maizels, 2008; Klotz et al., 2011) Therefore we explored, in detail, the relationship of this protein to homologs in D. viviparus and a range of other nematodes.

Table 2.

Transcripts encoding proteins predicted to have key roles in nematode-host interactions and inferred to be enriched in the adult stage of Dictyocaulus filaria.

| Designation of ortholog/homolog (species) | Sequence code D. filaria | FPKM | Sequence code D. viviparus | FPKM | Accession number | E-value; bit score | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cathepsin B peptidases, partial (Ac) | Dfil17598776 | 1805.7 | Dviv17666286 a | 261.3 | NCBI:AAC46878 | 4×10−108; 372.0 | Ranjit et al. (2008) |

| Dfil17598778 | 519.1 | Dviv17666286 a | 261.3 | NCBI:AAC46878 | 7×10−49; 175 | ||

| Dfil17598712 | 1190.3 | Dviv17666286 a | 261.3 | NCBI:AAC46878 | 1×10−79; 278 | ||

| Dfil17598717 | 1186.1 | Dviv17667352 a | 481.2 | NCBI:AAC46878 | 1×10−29; 112 | ||

| Dfil17598298 | 4039.7 | Dviv17666286 a | 261.3 | NCBI:AAC46878 | 4×10−50; 179 | ||

| Dfil17599746 | 2431.6 | Dviv17670798 a | 111.2 | NCBI:AAC46878 | 5×10−28; 105 | ||

| Dfil17615864 | 113.2 | Dviv17666286 a | 46.7 | NCBI:AAC46878 | 1×10−84; 294 | ||

| Fatty-acid and retinol-binding protein 1 (Ac) | Dfil17600048 | 6114.5 | Dviv17667361 a | 310.9 | NCBI:AAM93667 | 3×10−41; 211 | Basavaraju et al. (2003); Bath et al. (2009) |

| Dfil17611331 | 172.8 | Dviv17679991 | 7.1 | NCBI:AAM93667 | 6×10−56; 165 | ||

| Dfil17603002 | 1627.1 | Dviv17667690 a | 395.0 | NCBI:AAM93667 | 6×10−31; 100 | ||

| Beta-galactoside- binding lectin - galectin (Hc) | Dfil17603450 | 211.8 | Dviv17668724 a | 145.3 | UniProt:O44126 | 8×10−118; 404 | Hewitson et al. (2009) |

| Dfil17631226 | 407.1 | Dviv17676002 | 20.3 | UniProt:O44126 | 3×10−14; 60 | ||

| Dfil17621266 | 241.9 | Dviv17676002 | 20.3 | UniProt:O44126 | 3×10−70; 246 | ||

| Dfil17624969 | 245.3 | Dviv17676887 | 42.2 | UniProt:O44126 | 9×10−61; 215 | ||

| Dfil17608910 | 326.9 | Dviv17671378 a | 200.2 | UniProt:O44126 | 4×10−18; 66 | ||

| Dfil17606742 | 473.0 | Dviv17670877 a | 90.8 | UniProt:O44126 | 0; 538 | ||

| Secreted protein 6 precursor (Ac) | Dfil17616091 | 268.3 | Dviv17675465 | 30.7 | NCBI:AAO63578 | 2×10−14; 62 | Cantacessi et al. (2009) |

| Dfil17603746 | 1145.5 | Dviv17670798 a | 90.1 | NCBI:AAO63578 | 9×10−08; 40 | ||

| Dfil17608171 | 330.2 | Dviv17675465 | 30.7 | NCBI:AAO63578 | 2×10−13; 59 | ||

| Transthyretin-like protein (Bm) | Dfil17617022 | 408.5 | Dviv17674180 | 14.9 | NCBI:EDP38814 | 2×10−21; 82 | Hewitson et al. (2009) |

| Cystatin CPI (Nb) | Dfil17600089 | 519.7 | Dviv17683021 | 23.9 | NCBI:BAB59011 | 7×10−47; 194 | Dainichi et al., (2001) |

| Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (Bm) | Dfil17618988 | 233.2 | Dviv17667255 | 20.9 | NCBI:CAC70155.1 | 7×10−43; 126 | Pastrana et al. (1998) |

| Dfil17647749 | 116.9 | Dviv17676513 | 9.14 | NCBI:CAC70155.1 | 6×10−23; 75 | ||

| Glutathione peroxidase (Hc) | Dfil17600550 | 106.6 | Dviv17666277 | 17.2 | NCBI:AAT28332 | 4×10−28; 105 | Hartman et al. (2001) |

| Dfil17625009 | 232.7 | Dviv17679072 | 18.2 | NCBI:AAT28332 | 5×10−111; 407 |

FPKM, fragments per kilobase of transcript per million total sequence fragments mapped; Ac, Ancylostoma caninum; Bm, Brugia malayi; Hc, Haemonchus contortus; Nb, Nippostrongylus brasiliensis.

Genes of Dictyocaulus viviparus inferred to be highly transcribed.

3.3. Analysis of the type 2-like cystatins of Dictyocaulus spp. and other nematodes

The type 2-like cystatins predicted for D. filaria were compared with homologs from other nematodes (Table 3), accessible from public databases (Elsworth et al., 2011; Martin et al., 2012; Yook et al., 2012; Mangiola et al., 2013). Assisted by the identification of type-2 cystatin domains, 43 full-length homologs were identified in 24 other species of nematodes (Table 3; Fig. 2). Overall, based on alignment, the aa sequences had similar features (Table 3; Fig. 2), but there were some differences among them.

Table 3.

Key features of the amino acid sequences of type 2-like cystatins for various nematodes, including Dictyocaulus filaria and Dictyocaulus viviparus studied herein

| Nematodes | Protein sequence code | Accession number | Key elements of type 2-like cystatins

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SP | G | QXVXG | CC | PW | AEP | AEP codons | |||||

| Order Strongylida | |||||||||||

| Ancylostoma caninum | Ac -CPI/a | Nematode.net: Acan_isotig04796 (trans) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | SNA | TCG | AAT | GCT |

| Ac-CPI/b | Nematode.net: Acan_isotig01924 (trans) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | SNL | AGT | AAT | CTG | |

| Ac-CPI/c | Nematode.net: Acan_isotig06817 (trans) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | SNG | TCC | AAC | GGC | |

| Angiostrongylus vasorum | Ava-CPI | HelmDB:Avas8850088 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | SNA | TCG | AAC | GCA |

| Dictyocaulus filaria | Df-CPI | HelmDB:Dfil1654476 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | SNE | TCG | AAT | GAA | |

| Dictyocaulus viviparus | Dv-CPI | Sup. material: Dviv14021295 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | SNE | TCA | AAT | GAA | |

| Haemonchus contortus | Hc-CPI/a | Sup. material: Hcon01 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | AND | GCG | AAT | GAT |

| Hc-CPI/b | Sup. material: Hcon02 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | SNE | TCA | AAT | GAA | |

| Hc-CPI/c | Sup. material: Hcon03 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | SND | TCA | AAC | GAT | |

| Heligmosomoides polygyrus | Hp-CPI | NCBI: AGA95986.1 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | SNA | TCG | AAC | GCT |

| Necator americanus | Na-CPI/a | HelmDB:Name4169628 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | SN− | AGC | AAT | GGT | |

| Na-CPI/b | HelmDB:Name3969602 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | VND | GTC | AAC | GAC | |

| Na-CPI/c | HelmDB:Name3969149 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | SND | TCT | AAC | GAT | |

| Nippostrongylus brasiliensis | Nb-CPI | NCBI: BAB59011.1 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | SNE | TCC | AAT | GAG |

| Oesophagostomum dentatum | Od-CPI/a | HelmDB:Oden4876005 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | SNA | TCT | AAT | GCT | |

| Od-CPI/b | HelmDB:Oden4682688 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | SNA | TCA | AAT | GCT | |

| Od-CPI/c | HelmDB:Oden4799499 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | SNA | TCC | AAT | GCA | |

| Trichostrongylus axei | Ta-CPI | Sup. material: Taxe6078832 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | SNA | TCA | AAT | GCC |

| Trichostrongylus colubriformis | Tc-CPI | Sup. material: Tcol3751336 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | SNA | TCA | AAT | GCC |

| Order Rhabditida | |||||||||||

| Caenorhabditis elegans | Ce-CPI-1 | WormBase:WP:CE18035 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | −NN | AAG | AAT | AAT |

| Ce-CPI-2 | WormBase: WP:CE25962 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | SNN | TCC | AAC | AAC | |

| Heterorhabditis bacteriophora | Hb-CPI | WUSTL: contig1346 (trans) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | NNG | AAC | AAT | GGT |

| Strongyloides ratti | Sr-CPI | Sanger: SRAE_2361000 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | SND | TCA | AAT | GAT | |

| Order Diplogasterida | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ||||||

| Pristionchus pacificus | Pp-CPI | www.pristionchus.org: TRA00000190911 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | SND | TCC | AAT | GAC |

| Order Ascaridida | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ||||||

| Ascaris suum | As-CPI/a | HelmDB:Asuu7980596 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | SND | TCG | AAC | GAT |

| As-CPI/b | HelmDB:Asuu7717467 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | SND | TCG | AAC | GAT | |

| As-CPI/c | WormBase: Scaffold798 (trans) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | SND | TCG | AAC | GAT | ||

| Order Spirurida | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ||||||

| Acanthocheilonema viteae | Avi-CPI | NCBI: AAA87228 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | SNV | TCA | AAC | GTG | |

| Brugia malayi | Bm-CPI-1 | NCBI:AAC47623 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | TRY | ACT | AGA | TAT | |

| Bm-CPI-2 | NCBI:XP_001895475 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | SND | TCA | AAC | GAT | |

| Bm-CPI-3 | NCBI:AAB69857 | ✓ | ✓ | LR− | TTG | AGA | GGT | ||||

| Dirofilaria immitis | Di-CPI-2/a | Nematodes.org:Ndi.2.2.2.t08234-RA | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | SND | TCA | AAC | GAT |

| Di-CPI2/b | Nematodes.org:Ndi.2.2.2.t08235-RA | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | SND | TCA | AAC | GAT | |

| Litomosoides sigmodontis | Ls-CPI | NCBI:AAF35896 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | SND | TCA | AAC | GAT | |

| Loa loa | Ll-CPI-1 | NCBI: XP_003136654 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | TRS | ACT | AGG | AGC |

| Ll-CPI-2/a | NCBI: XP_003147913 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | SND | TCA | AAC | GAT | |

| Ll-CPI-2/b | NCBI: XP_003145409 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | SND | TCA | AAC | GAT | |

| Onchocerca volvulus | Ov-CPI-1 | NCBI:AAD51087 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | MK Y |

ATG | AAA | TAT |

| Ov-CPI-2 | UniProt:P22085 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | SND | TCA | AAC | GAT | |

| Wuchereria bancrofti | Wb-CPI-1 | NCBI: EJW82673 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | TNY | ACT | AAC | TAC |

| Order Trichocephalida | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ||||||

| Trichinella spiralis | Tsp-PI/a | WUSTL: Contig1.89 (trans) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | SKE | TCC | AAA | GAA | |

| Tsp-PI/b | WUSTL: Contig1.103 (trans) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | SNS | AGC | AAT | AGC | |

| Trichuris suis | Tsu-PI/a | HelmDB:Tsui7356239 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | TDS | ACC | GAC | AGT |

| Tsu-PI/b | HelmDB:Tsui7387460 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | SND | TCC | AAC | GAT | ||

| Order Tylenchida | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ▪ | ||||||

| Meloidogyne hapla | Mh-CPI | WormBase: MhA1_Contig41.frz3.gene10 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | SNS | TCT | AAT | TCT |

Key structural or functional elements in the type-2-like cystatins, identified based on the conserved motifs present in chicken cystatin C (Bode et al., 1988). For type 2-like cystatins, the presence (tick) of a signal peptide domain (SP); residues involved in papain-like peptidase binding, including the N-terminus glycine (G); the primary inhibitor domain (QXVXG), the central cysteine disulfide bond (CC); the C-terminus domain (PW); and a conserved motif known to be involved in the binding of the asparaginyl endopeptidase (AEP). Accession numbers of cystatin-like proteins are given where available. If proteins were conceptually translated from nucleotide sequence data (trans), accession numbers of nucleotide sequences are listed. Accession numbers are linked to public databases, including HelmDB (HelmDB: www.helmdb.org), National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI:www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), Nematode & Neglected Genomics at the Blaxter Laboratory, Institute of Evolutionary Biology, School of Biological Sciences, The University of Edinburgh, UK (Nematodes.org: www.nematodes.org/); the Genome Institute at Washington University, USA (WUSTL; nematode.net); WormBase (www.wormbase.org); and the Pristionchus pacificus genome website at Max-Planck-Institut für Entwicklungsbiologie, Germany (www.pristionchus.org).

The signal peptide was present in most sequences, except for protein Na-CPI/a (N. americanus) (Fig. 2). The three ‘functional’ motifs involved in the binding to the cathepsins B, L and S (C1 papain-like peptidases) (Bode et al., 1988; Alvarez-Fernandez et al., 1999) were relatively conserved among sequences (Fig. 2). However, there were some variations: (i) the conserved glycine residue at the N-terminus of the mature peptide was absent from the proteins Bm-CPI-1 and Bm-CPI-3 (Brugia malayi); (ii) the central cystatin-specific flexible loop glutamine-X-valine-X-glycine (QXVXG) was absent from Bm-CPI-3 (B. malayi); (iii) the proline-tryptophan (PW) hairpin loop-pair at the C-terminus of the mature peptide was absent from Av-CPI (Acanthocheilonema viteae); (iv) the disulfide bond, essential for positioning the N-terminal glycine to the right spatial conformation (Bode et al., 1988), was absent from protein Sr-CPI (Strongyloides ratti). Interestingly, a total of four sequences for As-CPI/b (A. suum), Tsp-CPI/a, Tsp-CPI/b (Trichinella spiralis) and Tsu-CPI/a (T. suis) (Table 3) were predicted to form a second disulfide bond at the C-terminus of the protein (Fig. 2), similar to the cystatin of chicken (Gallus gallus) (Bode et al., 1988) and mammals, such as cattle (B. taurus), sheep (O. aries) and humans (Homo sapiens) (Gregory and Maizels, 2008; Klotz et al., 2011). The C13 legumain-like asparaginyl endopeptidase (AEP)-binding loop motif was present in some sequences but absent from others, which likely relates to the evolution of type 2-like cystatins in nematodes (Fig. 3).

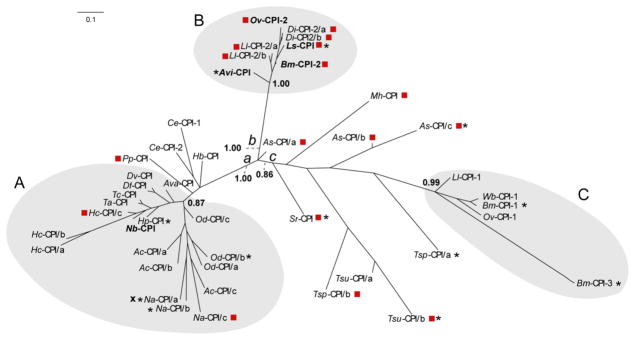

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic tree. The relationships of type 2-like cystatins of Dictyocaulus filaria (Df-CPI) and Dictyocaulus viviparus (Dv-CPI) compared with other nematodes, including proteins with a role in immunomodulation (bold) (see Table 3). A red square represents a sequence that possesses an SND/SNS C13 legumain-like asparaginyl endopeptidase (AEP)-binding loop motif. An asterisk represents a sequence that lacks one or more conserved motifs essential for the binding of C1 papain peptidase (Gregory and Maizels, 2008). An “X” represents a sequence that lacks a signal peptide. The clusters A–C shaded) and branches a–c are indicated. Posterior probabilities (pp) are indicated at key nodes. AEP, asparaginyl endopeptidase inhibitor domain; PW, C-terminus C1 papain-like peptidase binding domain; Ac, Ancylostoma caninum; As, Ascaris suum; Ava, Angiostrongylus vasorum; Avi, Acanthocheilonema viteae; Bm, Brugia malayi; Ce, Caenorhabditis elegans; Di, Dirofilaria immitis; Hb, Heterorhabditis bacteriophora; Hc, Haemonchus contortus; Hp, Heligmosomoides polygyrus; Ll, Loa loa; Ls, Litomosoides sigmodontis; Mh, Meloidogyne hapla; Na, Necator americanus; Nb, Nippostrongylus brasiliensis; Od, Oesophagostomum dentatum; Ov, Onchocerca volvulus; Pp, Pristionchus pacificus; Sr, Strongyloides ratti; Ta, Trichostrongylus axei; Tc, Trichostrongylus colubriformis; Tsp, Trichinella spiralis; Tsu, Trichuris suis; Wb, Wuchereria bancrofti.

To explore the evolutionary relationships of type 2-like cystatins of D. filaria and D. viviparus with respect to the 43 homologs from other nematode species, an alignment of aa sequences was made (Fig. 2), taking into account key motifs (cf. Alvarez-Fernandez et al., 1999). The BI analysis, characterized by an average S.D. of split frequencies of 0.012 and an average potential scale reduction factor (PSRF; excluding NA and >10.0) of 1.004 (cf. Ronquist et al., 2012), showed three main clusters of type 2-like cystatin sequences (A–C) (Fig. 3). Cluster A comprised sequences of nematodes of the orders Strongylida and Rhabditida, including the superfamilies Ancylostomatoidea, Metastrogyloidea, Strongyloidea and Trichostrongyloidea (pp = 0.87), whereas the well-separated clusters B and C both represented nematodes of the superfamily Filarioidea (pp = 1.00 and 0.99, respectively). In addition to the genes that clustered, sequences representing the Strongyloidea related to branch a, whereas others representing superfamilies Ascaridoidea, Strongyloidoidea, Trichuroidea and Trichinelloidea were dispersed on branch c; for the majority of them, nodal support (pp values of < 0.70) was insufficient to infer clusters for these sequences. In the aligned aa sequence region encoding an AEP-like motif, four and eight of 19 sequences within cluster A contained SNA and SNE motifs, respectively, and two contained an SND/SNS motif (Table 3). In contrast, six of eight sequences in cluster B contained SND/SNS motifs. None of the five sequences in cluster C had an SNE, SNA or SND/SNS motif. Although the codon usage for the AEP motif was relatively conserved within a particular nematode order, it was variable for the SND/SNS motifs (Table 3). For a small number of sequences in each cluster, one or more motifs linked to the binding of cysteine peptidases or signal peptides were lacking.

4. Discussion

Here, we explored the transcriptome of the adult stage of D. filaria and qualitatively compared it with D. viviparus. The majority (71.0%) of predicted proteins conceptually translated from the adult D. filaria transcriptome had homologs in D. viviparus, reflecting the similarity in biology of the two species. Furthermore, the molecular similarities between D. filaria and D. viviparus were supported by comparable numbers of encoded proteins in conserved functional protein categories (Fig. 1). Only 3% of the ‘orphan’ genes in D. filaria were inferred to encode functional proteins by homology comparisons with sequences in public databases. The high number of species-specific proteins may also reflect genetic divergence among the dictyocaulids associated with their adaptation to specific hosts (Gasser et al., 2012).

We focused on a select group of predicted ES molecules which were highly transcribed in adult worms and likely linked to parasite-host interactions (Table 2). Proteins inferred to be enriched in D. filaria and D. viviparus included beta-galactoside-binding lectins (= galectins), and secreted protein 6 precursor, also known as SCP/Tpx-1/Ag5/PR-1/Sc7 (SCP/TAPS) (Cantacessi et al., 2009). Galectins have also been reported to be abundantly transcribed in other nematodes such as H. contortus (see Greenhalgh et al., 2000), and can interfere with antigen uptake and presentation, cell adhesion, apoptosis and T cell polarization in the host (Hewitson et al., 2009). In Dictyocaulus spp., SCP/TAPS proteins might also be involved in regulating or altering some immune responses and/or can play a role in host invasion (Cantacessi and Gasser, 2011). This statement is supported somewhat by the proposal that the SCP/TAPS protein Na-ASP-2 of the hookworm N. americanus is an antagonistic ligand of complement receptor 3 (CR3) (Asojo et al., 2005; Bower et al., 2008).

Other immunomodulators relating to high transcription in adult D. filaria included homologs of vertebrate macrophage migration inhibitory factor, peroxidases and a TTL protein. This migration inhibitory factor might inhibit the circulation of macrophages (Pastrana et al., 1998), while ES peroxidases might play a protective role by inhibiting damage caused by host-derived reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Henkle-Dührsen and Kampkötter, 2001; Melendez et al., 2007; Chiumiento and Bruschi, 2009). TTL proteins, characterised previously in ES products from Ostertagia ostertagi and H. contortus (see Hewitson et al., 2009) and B. malayi and D. immitis (see Geary et al., 2012), have been suggested to bind retinoids and/or immunoregulators (Hewitson et al., 2009). Some genes that were highly transcribed in adults of both D. filaria and D. viviparus encoded proteins with a predicted role in immunomodulation and/or metabolism. These include fatty acid- and retinol-binding proteins and cathepsins B. Homologs of the fatty acid- and retinol-binding proteins, predicted to be ES proteins of Dictyocaulus spp., have been identified in the ES products of A. caninum (Zhan et al., 2003). Besides their known role in nutrient acquisition (Mei et al., 1997; Kennedy, 2000; McDermott et al., 2002), these proteins are proposed to play an active role in the establishment or maintenance of infection. The ability of fatty acid- and retinol-binding proteins to sequester retinol – which is involved in the synthesis of collagen, tissue repair (Bulger and Helton, 1998) and IgA production (Nikawa et al., 1999) –suggests that these proteins might regulate immune responses in the host animal (McSorley et al., 2013). Cathepsin B-like enzymes are an important component of the degradome of nematodes, including haematophagous worms (Williamson et al., 2003; Cantacessi et al., 2010a, b; Knox, 2011; Mangiola et al., 2013; Schwarz et al., 2013). Cathepsin-like cysteine peptidases are enzymes involved in the digestion of blood and are also involved in other key biological processes, including the establishment and maintenance of infection in the host (Tort et al., 1999; Williamson et al., 2003; McKerrow et al., 2006). As most cathepsins play a general role in intracellular protein metabolism, they are usually tightly regulated and expressed as inactive zymogens, which contain cysteine peptidase inhibitor domains and protect cells from proteolytic damage (Dickinson, 2009). In addition to cathepsin B, a D. filaria type 2-like cystatin was also abundantly represented in the adult. Type 2-like cystatins are an important group of endogenous proteins that inhibit cysteine peptidases, including members of the papain- (C01) and AEP-like (C13) peptidases. In parasites, excreted/secreted cystatins are also potent inhibitors of host peptidases, and can modulate the host immune response via the inhibition of host cathepsins and AEPs that are required for antigen processing/presentation and/or the regulation of pattern recognition receptor signaling (Vray et al., 2002; Klotz et al., 2011). Secreted cystatins of some parasitic nematodes can also down-regulate inflammation by employing multiple immunological pathways in the host, for example, by reducing Th2-related inflammation via the induction of IL-10 cytokine production in macrophages (Schnoeller et al., 2008). Although cysteine peptidases were abundant in the transcriptomes of both Dictyocaulus spp., the apparent abundance of type 2 cystatin (a cysteine peptidase inhibitor) solely in D. filaria prompted further study of their potential role in modulating host immune responses to infection. Interestingly, a number of conserved characteristics of nematode secreted type 2-like cystatins appear to have evolved independently from those that inhibit peptidases (Klotz et al., 2011). Exploring the levels of conservation in protein domain sequences revealed various groups of type 2-like cystatins among 26 nematode species (Fig. 3).

Cystatins were of particular interest due to distinct transcription between D. filaria and D. viviparus, and due to their role in immunomodulation and/or metabolism in parasitic nematodes (Hartmann et al., 1997; Dainichi et al., 2001; Manoury et al., 2001; Schonemeyer et al., 2001; Pfaff et al., 2002). The type 2-like cystatins predicted for Dictyocaulus and orthologs of related strongylid nematodes seem to have co-evolved with cystatins from distantly related parasitic nematodes (cf. Table 3; Fig. 3). However, the phylogenetic relationships of all type 2-like cystatins of nematodes are not consistent with the evolution of the nematodes themselves. For parasitic nematodes, the role of cystatins as endogenous and/or host-derived papain-like cysteine peptidase inhibitors appears to be relatively conserved, with various nematode species, including D. filaria and D. viviparus, retaining at least one type 2-like cystatin with the three conserved domains that interact with papain-like cysteine peptidases (Bode et al., 1988). In contrast, the ability of nematode cystatins to inhibit host AEP-like cysteine peptidases is not a characteristic shared by all nematode cystatins studied to date, rather a trait acquired by some parasites to enhance their capacity to evade immune responses (Manoury et al., 2001; Murray et al., 2005). The presence of a relatively conserved SND/SNS domain in cystatins is not restricted to a particular nematode order, but is dispersed among nematode groups (Fig. 2). Interestingly, an alignment of the type 2-like cystatin sequences of key parasitic nematodes (Fig. 2) reveals an aa substitution in this domain in strongylid and rhabditid nematodes compared with other representatives. Furthermore, an alignment of the AEP-motif coding domain suggests that a functional AEP binding motif (encoding an SND/SNS) evolved independently more than once, being lost from a common ancestor of the Strongylida/Rhabditida and then re-emerging, possibly via convergent evolution, as an isoform of the type 2-like cystatins of H. contortus, N. americanus and Pristionchus pacificus. This is consistent with the hypothesis that parasitism evolved more than once in the Phylum Nematoda (Blaxter et al., 1998), and suggests that the AEP-motif plays an important role in nematode-mammalian host interactions. At this point, the ability of type 2-like cystatins of D. filaria and D. viviparus to inhibit host AEP is uncertain. Findings from a functional study of the free-living nematode C. elegans suggest that a cystatin encoding an AEP inhibitory site with an alternative polar/hydrophilic aa residue at the third position (SNN) does not inhibit mammalian AEP (Murray et al., 2005). Nonetheless, a negatively charged, polar aa residue at the third position of the conserved AEP inhibitory site (SNE) (Table 3; Fig. 2) suggests that a broader range of nematode cystatins may inhibit host AEP and function via the disruption of antigen processing/presentation (Murray et al., 2005). Current evidence (Table 3; Fig. 2) suggests that conserved domains appear to have been lost upon cystatin gene duplication, which might relate to a loss of cysteine peptidase inhibition of respective cystatins. A striking example is B. malayi, whose genome encodes three type 2-like cystatins, two of which are developmentally regulated and do not retain the conserved domains required for peptidase inhibition. A loss of conserved domains linked to cysteine peptidase inhibition was also observed for other nematodes in which more than one copy of the cystatin gene was encoded in genomic/transcriptomic data sets (Table 3; Fig. 2).

Experimental evidence for various parasitic nematodes (Klotz et al., 2011), including strongylids, suggests that cystatins expressed in the adult stages of D. filaria and D. viviparus might play one or multiple roles in modulating host immunity, independent of inhibition of host cysteine peptidases. For instance, cystatins of some parasitic nematodes retain a conserved mechanism to modulate cytokine production (Hartmann et al., 2002) and/or nitric oxide (NO) synthesis in antigen-presenting cells in the host animal (reviewed by Klotz et al., 2005), but are not linked to a common immune pathway. While cystatins of selected filarial nematodes, for example, induced NO production in IFN-gamma-primed macrophages in a TNF-alpha and IL-10-dependent manner (Hartmann et al., 1997; Schnoeller et al., 2008), cystatins of other nematodes can stimulate NO production in an IL10-independent manner (Garraud et al., 1995). Clearly, based on current opinion (Klotz et al., 2011), particular structures of cystatins secreted by parasitic nematodes are likely to be critical in maintaining an effective interplay with the host animal. Interestingly, Hartmann et al. (2002) demonstrated also that the N-terminal region of cystatins of some filarial nematodes is essential for cysteine peptidase inhibition, but not for the induction of NO in host macrophages. Future study, focused on the conserved structures within the C-terminal region of these proteins, is needed to assess the functionality of conserved (secondary or tertiary) domains/motifs. This work could be done by cloning an array of genes encoding secreted cystatins from non-filarial nematodes, expressing these proteins and testing them on host antigen-presenting cells to elucidate their immunomodulatory capacities.

Highlights.

Dictyocaulus filaria and Dictyocaulus viviparus transcriptomes were compared

Some enriched molecules were linked to host interactions

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the Australian Research Council (ARC) and Australian National Health & Medical Research Council (NHMRC). This project was also supported by a Victorian Life Sciences Computation Initiative (VLSCI) grant number VR0007 on its Peak Computing Facility at the University of Melbourne, an initiative of the Victorian Government, Australia. Other support from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, Germany, and the Melbourne Water Corporation, Australia, is gratefully acknowledged (R.B.G), as is funding from and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI), USA and National Institutes of Health (NIH), USA (P.W.S.). M.M. also received funds from NIH. N.D.Y is an NHMRC Early Career Research (ECR) Fellow. We also acknowledge the continued contributions of staff at WormBase (www.wormbase.org).

Footnotes

Note: Nucleotide sequence data reported in this article are publicly available in HelmDB (www.helmdb.org) and Nematode.net (www.nematode.net). RNA-seq data sets have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) sequence read archive - www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Traces/sra/under accession numbers SRP032224 (Dictyocaulus filaria), SRR1021573 and SRR1021571 (Dictyocaulus viviparus).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abrahamson M, Alvarez-Fernandez M, Nathanson C. Cystatins. Biochem Soc Symp. 2003;70:179–199. doi: 10.1042/bss0700179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen MA, Hillier LW, Waterston RH, Blumenthal T. A global analysis of C. elegans trans-splicing. Genome Res. 2011;21:255–264. doi: 10.1101/gr.113811.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Fernandez M, Barrett AJ, Gerhartz B, Dando PM, Ni J, Abrahamson M. Inhibition of mammalian legumain by some cystatins is due to a novel second reactive site. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:19195–19203. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.27.19195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RC. Their Development and Transmission. CABI Publishing; Wallingford, UK: 2000. Nematode Parasites of Vertebrates. [Google Scholar]

- Asojo OA, Goud G, Dhar K, Loukas A, Zhan B, Deumic V, Liu S, Borgstahl GE, Hotez PJ. X-ray structure of Na-ASP-2, a pathogenesis-related-1 protein from the nematode parasite, Necator americanus, and a vaccine antigen for human hookworm infection. J Mol Biol. 2005;346:801–814. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basavaraju SV, Zhan B, Kennedy MW, Liu Y, Hawdon J, Hotez PJ. Ac-FAR-1, a 20 kDa fatty acid- and retinol-binding protein secreted by adult Ancylostoma caninum hookworms: gene transcription pattern, ligand binding properties and structural characterisation. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2003;126:63–71. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(02)00253-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bath JL, Robinson M, Kennedy MW, Agbasi C, Linz L, Maetzold E, Scheidt M, Knox M, Ram D, Hein J. Identification of a secreted fatty acid and retinol-binding protein (Hp-FAR-1) from Heligmosomoides polygyrus. J Nematol. 2009;41:228. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley DR, Balasubramanian S, Swerdlow HP, Smith GP, Milton J, Brown CG, Hall KP, Evers DJ, Barnes CL, Bignell HR, Boutell JM, Bryant J, Carter RJ, Keira Cheetham R, Cox AJ, Ellis DJ, Flatbush MR, Gormley NA, Humphray SJ, Irving LJ, Karbelashvili MS, Kirk SM, Li H, Liu X, Maisinger KS, Murray LJ, Obradovic B, Ost T, Parkinson ML, Pratt MR, Rasolonjatovo IM, Reed MT, Rigatti R, Rodighiero C, Ross MT, Sabot A, Sankar SV, Scally A, Schroth GP, Smith ME, Smith VP, Spiridou A, Torrance PE, Tzonev SS, Vermaas EH, Walter K, Wu X, Zhang L, Alam MD, Anastasi C, Aniebo IC, Bailey DM, Bancarz IR, Banerjee S, Barbour SG, Baybayan PA, Benoit VA, Benson KF, Bevis C, Black PJ, Boodhun A, Brennan JS, Bridgham JA, Brown RC, Brown AA, Buermann DH, Bundu AA, Burrows JC, Carter NP, Castillo N, Chiara ECM, Chang S, Neil Cooley R, Crake NR, Dada OO, Diakoumakos KD, Dominguez-Fernandez B, Earnshaw DJ, Egbujor UC, Elmore DW, Etchin SS, Ewan MR, Fedurco M, Fraser LJ, Fuentes Fajardo KV, Scott Furey W, George D, Gietzen KJ, Goddard CP, Golda GS, Granieri PA, Green DE, Gustafson DL, Hansen NF, Harnish K, Haudenschild CD, Heyer NI, Hims MM, Ho JT, Horgan AM, Hoschler K, Hurwitz S, Ivanov DV, Johnson MQ, James T, Huw Jones TA, Kang GD, Kerelska TH, Kersey AD, Khrebtukova I, Kindwall AP, Kingsbury Z, Kokko-Gonzales PI, Kumar A, Laurent MA, Lawley CT, Lee SE, Lee X, Liao AK, Loch JA, Lok M, Luo S, Mammen RM, Martin JW, McCauley PG, McNitt P, Mehta P, Moon KW, Mullens JW, Newington T, Ning Z, Ling Ng B, Novo SM, O’Neill MJ, Osborne MA, Osnowski A, Ostadan O, Paraschos LL, Pickering L, Pike AC, Chris Pinkard D, Pliskin DP, Podhasky J, Quijano VJ, Raczy C, Rae VH, Rawlings SR, Chiva Rodriguez A, Roe PM, Rogers J, Rogert Bacigalupo MC, Romanov N, Romieu A, Roth RK, Rourke NJ, Ruediger ST, Rusman E, Sanches-Kuiper RM, Schenker MR, Seoane JM, Shaw RJ, Shiver MK, Short SW, Sizto NL, Sluis JP, Smith MA, Ernest Sohna Sohna J, Spence EJ, Stevens K, Sutton N, Szajkowski L, Tregidgo CL, Turcatti G, Vandevondele S, Verhovsky Y, Virk SM, Wakelin S, Walcott GC, Wang J, Worsley GJ, Yan J, Yau L, Zuerlein M, Mullikin JC, Hurles ME, McCooke NJ, West JS, Oaks FL, Lundberg PL, Klenerman D, Durbin R, Smith AJ. Accurate whole human genome sequencing using reversible terminator chemistry. Nature. 2008;456:53–59. doi: 10.1038/nature07517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaxter ML, De Ley P, Garey JR, Liu LX, Scheldeman P, Vierstraete A, Vanfleteren JR, Mackey LY, Dorris M, Frisse LM, Vida JT, Thomas WK. A molecular evolutionary framework for the phylum Nematoda. Nature. 1998;392:71–75. doi: 10.1038/32160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bode W, Engh R, Musil D, Thiele U, Huber R, Karshikov A, Brzin J, Kos J, Turk V. The 2.0 A X-ray crystal structure of chicken egg white cystatin and its possible mode of interaction with cysteine proteinases. EMBO J. 1988;7:2593–2599. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03109.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bower MA, Constant SL, Mendez S. Necator americanus: The Na-ASP-2 protein secreted by the infective larvae induces neutrophil recruitment in vivo and in vitro. Exp Parasitol. 2008;118:569–575. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2007.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buisine N, Quesneville H, Colot V. Improved detection and annotation of transposable elements in sequenced genomes using multiple reference sequence sets. Genomics. 2008;91:467–475. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulger EM, Helton WS. Nutrient antioxidants in gastrointestinal diseases. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1998;27:403–419. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8553(05)70010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantacessi C, Campbell B, Visser A, Geldhof P, Nolan M, Nisbet AJ, Matthews JB, Loukas A, Hofmann A, Otranto D. A portrait of the “SCP/TAPS” proteins of eukaryotes—developing a framework for fundamental research and biotechnological outcomes. Biotechnol Adv. 2009;27:376–388. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantacessi C, Campbell BE, Gasser RB. Key strongylid nematodes of animals - Impact of next-generation transcriptomics on systems biology and biotechnology. Biotechnol Adv. 2012;30:469–488. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2011.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantacessi C, Gasser RB. SCP/TAPS proteins in helminths—where to from now? Mol Cell Probes. 2011;26:54–59. doi: 10.1016/j.mcp.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantacessi C, Gasser RB, Strube C, Schnieder T, Jex AR, Hall RS, Campbell BE, Young ND, Ranganathan S, Sternberg PW, Mitreva M. Deep insights into Dictyocaulus viviparus transcriptomes provides unique prospects for new drug targets and disease intervention. Biotechnol Adv. 2011a;29:261–271. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantacessi C, Mitreva M, Campbell BE, Hall RS, Young ND, Jex AR, Ranganathan S, Gasser RB. First transcriptomic analysis of the economically important parasitic nematode, Trichostrongylus colubriformis, using a next-generation sequencing approach. Infect Genet Evol. 2010a;10:1199–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2010.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantacessi C, Mitreva M, Jex AR, Young ND, Campbell BE, Hall RS, Doyle MA, Ralph SA, Rabelo EM, Ranganathan S, Sternberg PW, Loukas A, Gasser RB. Massively parallel sequencing and analysis of the Necator americanus transcriptome. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010b;4:e684. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantacessi C, Young ND, Nejsum P, Jex AR, Campbell BE, Hall RS, Thamsborg SM, Scheerlinck JP, Gasser RB. The transcriptome of Trichuris suis — first molecular insights into a parasite with curative properties for key immune diseases of humans. PLoS One. 2011b;6:e23590. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Zhang Y, Yin Y, Gao G, Li S, Jiang Y, Gu X, Luo J. SPD—a web-based secreted protein database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D169–173. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiumiento L, Bruschi F. Enzymatic antioxidant systems in helminth parasites. Parasitol Res. 2009;105:593–603. doi: 10.1007/s00436-009-1483-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig H, Wastling JM, Knox DP. A preliminary proteomic survey of the in vitro excretory/secretory products of fourth-stage larval and adult Teladorsagia circumcincta. Parasitology. 2006;132:535–543. doi: 10.1017/S0031182005009510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuellar C, Wu W, Mendez S. The hookworm tissue inhibitor of metalloproteases (Ac-TMP-1) modifies dendritic cell function and induces generation of CD4 and CD8 suppressor T cells. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3:e439. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dainichi T, Maekawa Y, Ishii K, Zhang T, Nashed BF, Sakai T, Takashima M, Himeno K. Nippocystatin, a cysteine protease inhibitor from Nippostrongylus brasiliensis, inhibits antigen processing and modulates antigen-specific immune response. Infect Immun. 2001;69:7380–7386. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.12.7380-7386.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson DP. Cysteine peptidases of mammals: their biological roles and potential effects in the oral cavity and other tissues in health and disease. Crit Rev Oral Biol M. 2002;13:238–275. doi: 10.1177/154411130201300304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimmer EC, Huntley RP, Alam-Faruque Y, Sawford T, O’Donovan C, Martin MJ, Bely B, Browne P, Mun Chan W, Eberhardt R, Gardner M, Laiho K, Legge D, Magrane M, Pichler K, Poggioli D, Sehra H, Auchincloss A, Axelsen K, Blatter MC, Boutet E, Braconi-Quintaje S, Breuza L, Bridge A, Coudert E, Estreicher A, Famiglietti L, Ferro-Rojas S, Feuermann M, Gos A, Gruaz-Gumowski N, Hinz U, Hulo C, James J, Jimenez S, Jungo F, Keller G, Lemercier P, Lieberherr D, Masson P, Moinat M, Pedruzzi I, Poux S, Rivoire C, Roechert B, Schneider M, Stutz A, Sundaram S, Tognolli M, Bougueleret L, Argoud-Puy G, Cusin I, Duek-Roggli P, Xenarios I, Apweiler R. The UniProt-GO Annotation database in 2011. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D565–570. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsworth B, Wasmuth J, Blaxter M. NEMBASE4: the nematode transcriptome resource. Int J Parasitol. 2011;41:881–894. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster N, Eisheikha HM. The immune response to parasitic helminths of veterinary importance and its potential manipulaton for future vaccine control strategies. Parasitol Res. 2012;110:1587–1599. doi: 10.1007/s00436-012-2832-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu L, Niu B, Zhu Z, Wu S, Li W. CD-HIT: accelerated for clustering the next generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:3150–3152. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garraud O, Nkenfou C, Bradley JE, Perler FB, Nutman TB. Identification of recombinant filarial proteins capable of inducing polyclonal and antigen-specific IgE and IgG4 antibodies. J Immunol. 1995;155:1316–1325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasser RB, Jabbar A, Mohandas N, Hoglund J, Hall RS, Littlewood DT, Jex AR. Assessment of the genetic relationship between Dictyocaulus species from Bos taurus and Cervus elaphus using complete mitochondrial genomic datasets. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:241. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geary J, Satti M, Moreno Y, Madrill N, Whitten D, Headley SA, Agnew D, Geary T, Mackenzie C. First analysis of the secretome of the canine heartworm, Dirofilaria immitis. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:140. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer CJ. Practical chain Monte Carlo. Stat Sci. 1992;7:473–483. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh CJ, Loukas A, Donald D, Nikolaou S, Newton SE. A family of galectins from Haemonchus contortus. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2000;107:117–121. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(99)00230-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory WF, Maizels RM. Cystatins from filarial parasites: evolution, adaptation and function in the host-parasite relationship. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:1389–1398. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman D, Donald DR, Nikolaou S, Savin KW, Hasse D, Presidente PJ, Newton SE. Analysis of developmentally regulated genes of the parasite Haemonchus contortus. Int J Parasitol. 2001;31:1236–1245. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(01)00248-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann S, Kyewski B, Sonnenburg B, Lucius R. A filarial cysteine protease inhibitor down-regulates T cell proliferation and enhances interleukin-10 production. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:2253–2260. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann S, Lucius R. Modulation of host immune responses by nematode cystatins. Int J Parasitol. 2003;33:1291–1302. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(03)00163-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann S, Schonemeyer A, Sonnenburg B, Vray B, Lucius R. Cystatins of filarial nematodes up-regulate the nitric oxide production of interferon-gamma-activated murine macrophages. Parasite Immunol. 2002;24:253–262. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.2002.00459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings WK. Monte Carlo sampling methods using Markov chains and their applications. Biometrika. 1970;57:97–109. [Google Scholar]

- Heizer E, Zarlenga DS, Rosa B, Gao X, Gasser RB, De Graef J, Geldhof P, Mitreva M. Transcriptome analyses reveal protein and domain families that delineate stage-related development in the economically important parasitic nematodes, Ostertagia ostertagi and Cooperia oncophora. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:118. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henkle-Dührsen K, Kampkötter A. Antioxidant enzyme families in parasitic nematodes. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2001;114:129–142. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(01)00252-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitson JP, Grainger JR, Maizels RM. Helminth immunoregulation: the role of parasite secreted proteins in modulating host immunity. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2009;167:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitson JP, Harcus YM, Curwen RS, Dowle AA, Atmadja AK, Ashton PD, Wilson A, Maizels RM. The secretome of the filarial parasite, Brugia malayi: proteomic profile of adult excretory-secretory products. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2008;160:8–21. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzhauer M, van Schaik G, Saatkamp HW, Ploeger HW. Lungworm outbreaks in adult dairy cows: estimating economic losses and lessons to be learned. Vet Rec. 2011;169:494. doi: 10.1136/vr.d4736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kall L, Krogh A, Sonnhammer EL. A combined transmembrane topology and signal peptide prediction method. J Mol Biol. 2004;338:1027–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K, Standley DM. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy MW. The polyprotein lipid binding proteins of nematodes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1476:149–164. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(99)00249-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klotz C, Ziegler T, Danilowicz-Luebert E, Hartmann S. Cystatins of parasitic organisms. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2011;712:208–221. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-8414-2_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klotz L, Schmidt M, Giese T, Sastre M, Knolle P, Klockgether T, Heneka MT. Proinflammatory stimulation and pioglitazone treatment regulate peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma levels in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from healthy controls and multiple sclerosis patients. J Immunol. 2005;175:4948–4955. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.8.4948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knox D. Proteases in Blood-Feeding Nematodes and Their Potential as Vaccine Candidates. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2011;712:155–176. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-8414-2_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li BW, Wang Z, Rush AC, Mitreva M, Weil GJ. Transcription profiling reveals stage-and function-dependent expression patterns in the filarial nematode Brugia malayi. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:184. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Song Y, Jiang N, Wang J, Tang B, Lu H, Peng S, Chang Z, Tang Y, Yin J. Global gene expression analysis of the zoonotic parasite Trichinella spiralis revealed novel genes in host parasite interaction. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1794. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohse M, Bolger AM, Nagel A, Fernie AR, Lunn JE, Stitt M, Usadel B. RobiNA: a user-friendly, integrated software solution for RNA-Seq-based transcriptomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:W622–627. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magrane M, Consortium U. UniProt knowledgebase: a hub of integrated protein data. Database (Oxford) 2011;2011:bar009. doi: 10.1093/database/bar009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangiola S, Young ND, Korhonen P, Mondal A, Scheerlinck JP, Sternberg PW, Cantacessi C, Hall RS, Jex AR, Gasser RB. Getting the most out of parasitic helminth transcriptomes using HelmDB: implications for biology and biotechnology. Biotechnol Adv. 2013;31:1109–1119. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manoury B, Gregory WF, Maizels RM, Watts C. Bm-CPI-2, a cystatin homolog secreted by the filarial parasite Brugia malayi, inhibits class II MHC-restricted antigen processing. Curr Biol. 2001;11:447–451. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00118-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin J, Abubucker S, Heizer E, Taylor CM, Mitreva M. Nematode. net update 2011: addition of data sets and tools featuring next-generation sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D720–728. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott L, Kennedy MW, McManus DP, Bradley JE, Cooper A, Storch J. How helminth lipid-binding proteins offload their ligands to membranes: differential mechanisms of fatty acid transfer by the ABA-1 polyprotein allergen and Ov-FAR-1 proteins of nematodes and Sj-FABPc of schistosomes. Biochemistry. 2002;41:6706–6713. doi: 10.1021/bi0159635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKerrow JH, Caffrey C, Kelly B, Loke P, Sajid M. Proteases in parasitic diseases. Annu Rev Pathol. 2006;1:497–536. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.1.110304.100151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McSorley HJ, Hewitson JP, Maizels RM. Immunomodulation by helminth parasites: Defining mechanisms and mediators. Int J Parasitol. 2013;43:301–310. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei B, Kennedy MW, Beauchamp J, Komuniecki PR, Komuniecki R. Secretion of a novel, developmentally regulated fatty acid-binding protein into the perivitelline fluid of the parasitic nematode, Ascaris suum. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:9933–9941. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.15.9933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melendez AJ, Harnett MM, Pushparaj PN, Wong WS, Tay HK, McSharry CP, Harnett W. Inhibition of Fc epsilon RI-mediated mast cell responses by ES-62, a product of parasitic filarial nematodes. Nat Med. 2007;13:1375–1381. doi: 10.1038/nm1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metropolis N, Rosenbluth AW, Rosenbluth MN, Teller AH, Teller E. Equation of state calculations by fast computing machines. J Chem Phys. 1953;21:1087. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno Y, Geary TG. Stage- and gender-specific proteomic analysis of Brugia malayi excretory-secretory products. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2:e326. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulvenna J, Hamilton B, Nagaraj SH, Smyth D, Loukas A, Gorman JJ. Proteomics analysis of the excretory/secretory component of the blood-feeding stage of the hookworm, Ancylostoma caninum. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8:109–121. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800206-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray J, Manoury B, Balic A, Watts C, Maizels RM. Bm-CPI-2, a cystatin from Brugia malayi nematode parasites, differs from Caenorhabditis elegans cystatins in a specific site mediating inhibition of the antigen-processing enzyme AEP. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2005;139:197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikawa T, Odahara K, Koizumi H, Kido Y, Teshima S, Rokutan K, Kishi K. Vitamin A prevents the decline in immunoglobulin A and Th2 cytokine levels in small intestinal mucosa of protein-malnourished mice. J Nutr. 1999;129:934–941. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.5.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson SA. EMBOSS opens up sequence analysis. European Molecular Biology Open Software Suite Brief Bioinform. 2002;3:87–91. doi: 10.1093/bib/3.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panuska C. Lungworms of ruminants. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract. 2006;22:583–593. doi: 10.1016/j.cvfa.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parfitt JW, Sinclair IJ. Cross resistance to Dictyocaulus viviparus produced by Dictyocaulus filaria infections in calves. Res Vet Sci. 1967;8 (6):6–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra G, Bradnam K, Korf I. CEGMA: a pipeline to accurately annotate core genes in eukaryotic genomes. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:1061–1067. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastrana DV, Raghavan N, FitzGerald P, Eisinger SW, Metz C, Bucala R, Schleimer RP, Bickel C, Scott AL. Filarial nematode parasites secrete a homologue of the human cytokine macrophage migration inhibitory factor. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5955–5963. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.12.5955-5963.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaff AW, Schulz-Key H, Soboslay PT, Taylor DW, MacLennan K, Hoffmann WH. Litomosoides sigmodontis cystatin acts as an immunomodulator during experimental filariasis. Int J Parasitol. 2002;32:171–178. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(01)00350-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranjit N, Zhan B, Stenzel DJ, Mulvenna J, Fujiwara R, Hotez PJ, Loukas A. A family of cathepsin B cysteine proteases expressed in the gut of the human hookworm, Necator americanus. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2008;160:90–99. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawlings ND. A large and accurate collection of peptidase cleavages in the MEROPS database. Database (Oxford) 2009;2009:bap015. doi: 10.1093/database/bap015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MW, Connolly B. Proteomic analysis of the excretory-secretory proteins of the Trichinella spiralis L1 larva, a nematode parasite of skeletal muscle. Proteomics. 2005;5:4525–4532. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200402057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F, Teslenko M, van der Mark P, Ayres DL, Darling A, Hohna S, Larget B, Liu L, Suchard MA, Huelsenbeck JP. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst Biol. 2012;61:539–542. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/sys029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeed M, Baig MH, Bajpai P, Srivastava AK, Ahmad K, Mustafa H. Predicted binding of certain antifilarial compounds with glutathione-S-transferase of human Filariids. Bioinformation. 2013;9:233–237. doi: 10.6026/97320630009233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnoeller C, Rausch S, Pillai S, Avagyan A, Wittig BM, Loddenkemper C, Hamann A, Hamelmann E, Lucius R, Hartmann S. A helminth immunomodulator reduces allergic and inflammatory responses by induction of IL-10-producing macrophages. J Immunol. 2008;180:4265–4272. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.6.4265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonemeyer A, Lucius R, Sonnenburg B, Brattig N, Sabat R, Schilling K, Bradley J, Hartmann S. Modulation of human T cell responses and macrophage functions by onchocystatin, a secreted protein of the filarial nematode Onchocerca volvulus. J Immunol. 2001;167:3207–3215. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.6.3207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz MH, Zerbino DR, Vingron M, Birney E. Oases: robust de novo RNA-seq assembly across the dynamic range of expression levels. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:1086–1092. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz EM, Korhonen PK, Campbell BE, Young ND, Jex AR, Jabbar A, Hall RS, Mondal A, Howe AC, Pell J. The genome and developmental transcriptome of the strongylid nematode Haemonchus contortus. Genome Biol. 2013;14:R89. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-8-r89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SK, Nisbet AJ, Meikle LI, Inglis NF, Sales J, Beynon RJ, Matthews JB. Proteomic analysis of excretory/secretory products released by Teladorsagia circumcincta larvae early post-infection. Parasite Immunol. 2009;31:10–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2008.01067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strube C, Buschbaum S, Schnieder T. Genes of the bovine lungworm Dictyocaulus viviparus associated with transition from pasture to parasitism. Infect Genet Evol. 2012;12:1178–1188. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tort J, Brindley PJ, Knox D, Wolfe KH, Dalton JP. Proteinases and associated genes of parasitic helminths. Adv Parasitol. 1999;43:161–266. doi: 10.1016/s0065-308x(08)60243-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vray B, Hartmann S, Hoebeke J. Immunomodulatory properties of cystatins. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2002;59:1503–1512. doi: 10.1007/s00018-002-8525-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whelan S, Goldman N. A general empirical model of protein evolution derived from multiple protein families using a maximum-likelihood approach. Mol Biol Evol. 2001;18:691–699. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson AL, Brindley PJ, Knox DP, Hotez PJ, Loukas A. Digestive proteases of blood-feeding nematodes. Trends Parasitol. 2003;19:417–423. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4922(03)00189-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yatsuda AP, Krijgsveld J, Cornelissen AW, Heck AJ, de Vries E. Comprehensive analysis of the secreted proteins of the parasite Haemonchus contortus reveals extensive sequence variation and differential immune recognition. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:16941–16951. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212453200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]