Abstract

Background

Stromal derived factor-1α (sdf-1α), a chemoattractant chemokine, plays a major role in tumor growth, angiogenesis, metastasis and in embryogenesis. The sdf-1α signaling pathway has also been shown to be important for somite rotation in zebrafish (Hollway, et al 2007). Given the known similarities and differences between zebrafish and Xenopus laevis somitogenesis, we sought to determine whether the role of sdf-1α is conserved in Xenopus laevis.

Results

Using a morpholino approach, we demonstrate that knockdown of sdf-1α or its receptor, cxcr4, leads to a significant disruption in somite rotation and myotome alignment. We further show that depletion of sdf-1α or cxcr4 leads to the near absence of β-dystroglycan and laminin expression at the intersomitic boundaries. Finally, knockdown of sdf-1α decreases the level of activated RhoA, a small GTPase known to regulate cell shape and movement.

Conclusion

Our results show that sdf-1α signaling regulates somite cell migration, rotation and myotome alignment by directly or indirectly regulating dystroglycan expression and RhoA activation. These findings support the conservation of sdf-1α signaling in vertebrate somite morphogenesis; however, the precise mechanism by which this signaling pathway influences somite morphogenesis is different between the fish and the frog.

Keywords: somite, muscle, morphogenesis, sdf-1α, cxcr4, β-dystroglycan, RhoA, Xenopus laevis

INTRODUCTION

Somitogenesis establishes both the segmented body plan and the progenitors of the axial skeleton, dermis and skeletal muscle of the adult vertebrate. This process begins with cyclical subdivision of the presomitic mesoderm (PSM) into discrete blocks of mesodermal cells referred to as somites. Starting at the anterior end of the embryo, somites form at precise intervals as the axis elongates in the posterior direction. The proper temporal and spatial generation of somites during development is critical for the establishment of the major body plan of the adult.

Somitogenesis in Xenopus laevis involves a specific series of cell shape changes that eventually lead to the formation of somites comprised primarily of elongated myotome fibers. This process begins with cells at the anterior end of the PSM becoming progressively more elongated in the mediolateral axis (Afonin et al., 2006). This step is followed by the formation of the intersomitic boundary, which involves the deposition of critical extracellular matrix molecules such as laminin and fibronectin (Hidalgo et al., 2009). Soon after segmentation, individual cells within the somite undergo a 90° reorientation to form myotome fibers in parallel alignment with the notochord (Hamilton, 1969; Youn and Malancinski, 1981). This sequence of cell behaviors occurs every 50 minutes until 45 pairs of somites are formed in the X. laevis tadpole (Hamilton, 1969).

Although the cell behaviors that underlie somite formation in X. laevis appear to be unique, they share some similarities with behaviors underlying the formation of somites in zebrafish. Hollway and colleagues (2007) showed that zebrafish somite cells also undergo a 90° rotational event that is similar to one observed in X. laevis. Specifically, these researchers showed that the cells positioned in the anterior quadrant of the zebrafish somite express sdf-1α, a cytokine, as well as its receptor, cxcr4. Prior to somite rotation, the expression of sdf-1α moves to the lateral edge of the somite. Cells in the anterior compartment of the somite that express cxcr4 migrate towards the sdf-1α signal, causing a repositioning of the anterior somitic cells to the lateral edge of the somite compartment and, thus, driving the 90° rotation of the zebrafish somite.

The signaling molecules that drive somite rotation in X. laevis are not well understood. It is known that soon after segmentation cells within the somite increase their protrusive cell behavior to undergo a 90° rotation (Afonin et al., 2006). In contrast with what has been observed in zebrafish, all the cells within the X. laevis somite undergo this rotation. Once the cells complete rotation, their dynamic protrusive behavior ceases and is replaced by stable broad lamelopodial attachments to the intersomitic boundaries that lie at the anterior and posterior ends of each somite. At the completion of this process, the somite is composed primarily of elongated myotome fibers that are in parallel alignment to the notochord.

Given the known similarities and differences between somite rotation in zebrafish and X. laevis, we sought to determine whether the sdf-1α signal is important for somite rotation in X. laevis. Previous studies have identified and characterized sdf-1α and its receptor, cxcr4, in X. laevis (Moepps et al., 2000; and Braun et al., 2002). Both genes are known to be expressed at the onset of gastrulation and remain present throughout X. laevis development (Fukui, 2007). We show that knockdown of sdf-1α and its receptor cxcr4, leads to a disruption in X. laevis somite morphogenesis. Specifically, knockdown of sdf-1α and cxcr4 leads to a dramatic reduction in β-dystroglycan and laminin expression, both known to be important for the formation of intersomitic boundaries (Hidalgo et al., 2009). Prior studies using cell lines have shown that sdf-1 signaling activates the Rho family of GTPases during cell migration (Tan et al., 2006) and invasion (Bartolome et al., 2004). We provide in-vivo evidence that the sdf-1α signaling pathway also activates RhoA during X. laevis embryogenesis. We propose that activation of RhoA is important for regulating the dynamic cell behaviors necessary for proper somite rotation and myotome cell alignment in X. laevis. Though the precise cell behaviors associated with somite rotation vary between zebrafish and X. laevis, this study provides evidence of a conserved role for the sdf-1α signaling pathway in somite morphogenesis.

RESULTS

Knockdown of sdf-1α and cxcr4 lead to defects in somite morphogenesis

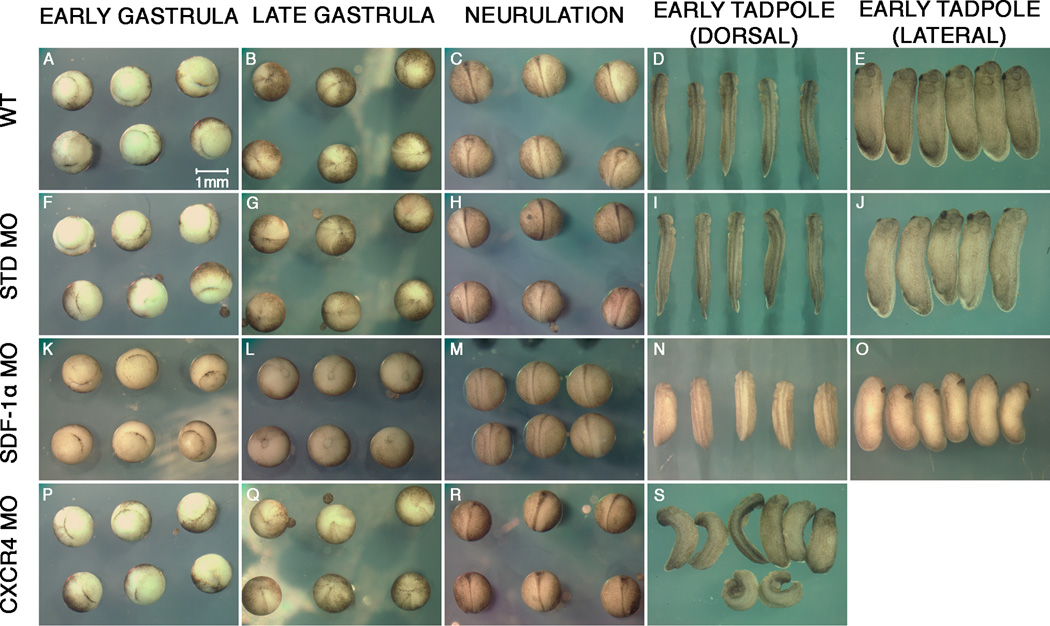

To determine the function of sdf-1α and cxcr4 during X. laevis somitogenesis, we used antisense moprholino oligonucleotides previously shown to block the expression of sdf-1α and cxcr4 (Fukui et al., 2007). Each morpholino (MO) was injected into one blastomere of two-cell stage embryos (Fig. 1). This approach results in embryos in which only the left or right side contains the specific MO. Thus, one side acts as a control and the contralateral side acts as the experiment. Moreover, unlike injecting sdf-1α and cxcr4 MO at the one-cell stage, which disrupts gastrulation movements (Fukui et al., 2007), embryos injected at the 2-cell stage undergo normal gastrulation as long as the fertilization envelope remains intact (Fig. 2). We show that after successfully progressing through gastrulation, as indicated by the closure of the blastopore (Fig. 2L,Q,), the sdf-1α and cxcr4 half-morphants proceed through neurulation, but they acquire slight curvatures in their axis (Fig. 2M,R). These curvatures become more pronounced as development progresses, indicating that one side of the embryo is significantly shorter than the contralateral side (Fig. 2N,S). In addition, sdf-1α and cxcr4 half-morphant embryos appear to be developmentally delayed in comparison to their controls. The cxcr4 half-morphants show a wider range of phenotypes with more severe curvatures than sdf-1α half-morphants (Fig. 2N,S). Together, these observations reveal that sdf-1α and cxcr4 half-morphants undergo normal gastrulation, but abnormal axis elongation.

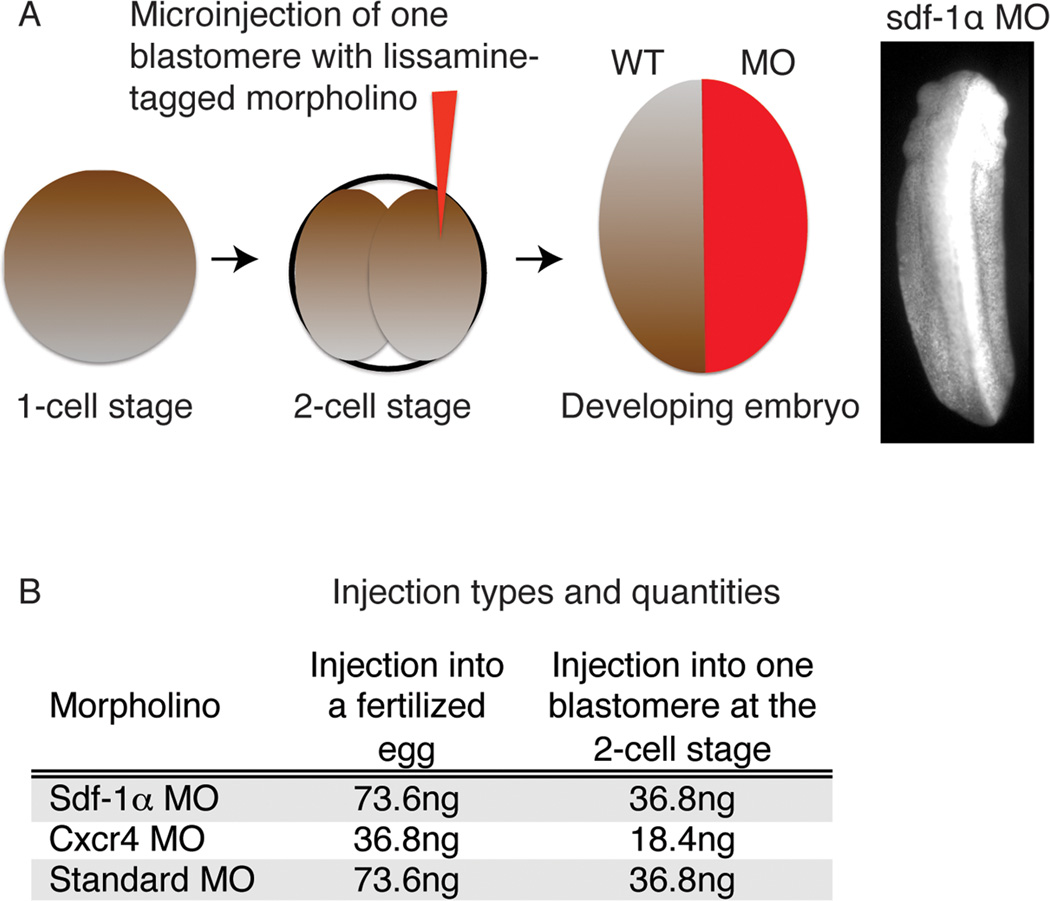

Figure 1. Experimental approach to the morpholino knockdown of sdf-1α and cxcr4.

(A) A schematic of the experiment in which one blastomere at the 2-cell stage is injected with a specific morpholino (MO) such that only half of the embryo is morphant. The embryo is then allowed to develop to tailbud stages and then fixed and analyzed. (B) A table indicating the specific amounts of MO injected into the fertilized egg or one blastomere at the two-cell stage.

Figure 2. Time-lapse imaging of sdf-1α and cxcr4 half-morphant embryos.

Live time-lapse images of wild type embryos (A–E), standard half-morphants (F–J), sdf-1α half-morphants (K–O), and cxcr4 half-morphants (P–S) as they proceed from gastrulation to the formation of early stage tadpoles (stages 26–28). Scale bar in (A) applies to all frames.

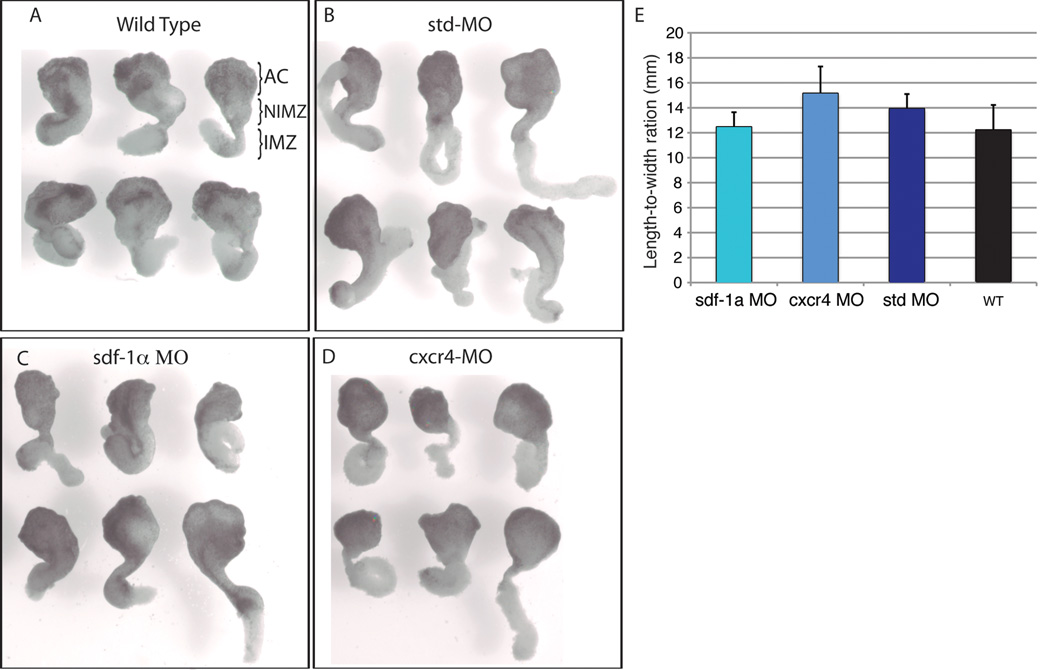

We next examined whether a defect in convergence and extension movements was responsible for the shortened axis observed in the cxcr4 and sdf-1α half-morphants. To test this possibility, we used a Keller sandwich assay, which tests whether individual cells can undertake the cell rearrangements to drive convergent extension (Keller and Danilchik, 1988). Embryos were injected with the specific MO at the one-cell stage and then cultured to the onset of gastrulation (stage 10), at which point Keller sandwiches were made by combining two dorsal lip explants together and culturing them under a coverslip to the early tailbud (stage 20). Sandwiches made from cxcr4 or sdf-1α morphant tissue were able to elongate to a similar extent to sandwiches made from wild type and standard-MO embryos (Fig. 3). This observation was further confirmed by the fact that there was no significant difference in length-to-width ratios between sandwiches made from cxcr4 or sdf-1α morphant embryos and the controls (Fig. 3E). Thus, the shortening we observed of the anteroposterior axis in the cxcr-4 and sdf-1α half-morphant embryos is not attributed to abnormalities in convergent extension.

Figure 3. Sdf-1α and cxcr4 are not required for convergent extension.

Keller sandwiches made from stage 10 wild type (A), standard MO (B), sdf-1α MO (C), and cxcr4 MO (D) embryos undergo the characteristic convergent extension to form a long and narrow array of cells. (E) Length-to-width ratio of Keller sandwiches reveal no significant differences between explants made from sdf-1α and cxcr4 morphant tissue compared to the controls. Statistical analysis was carried out by using the Student’s t test. Error bars indicate standard error. (AC) Animal Cap. (NIMZ) Non-involuting marginal zone. (IMZ) Involuting marginal zone.

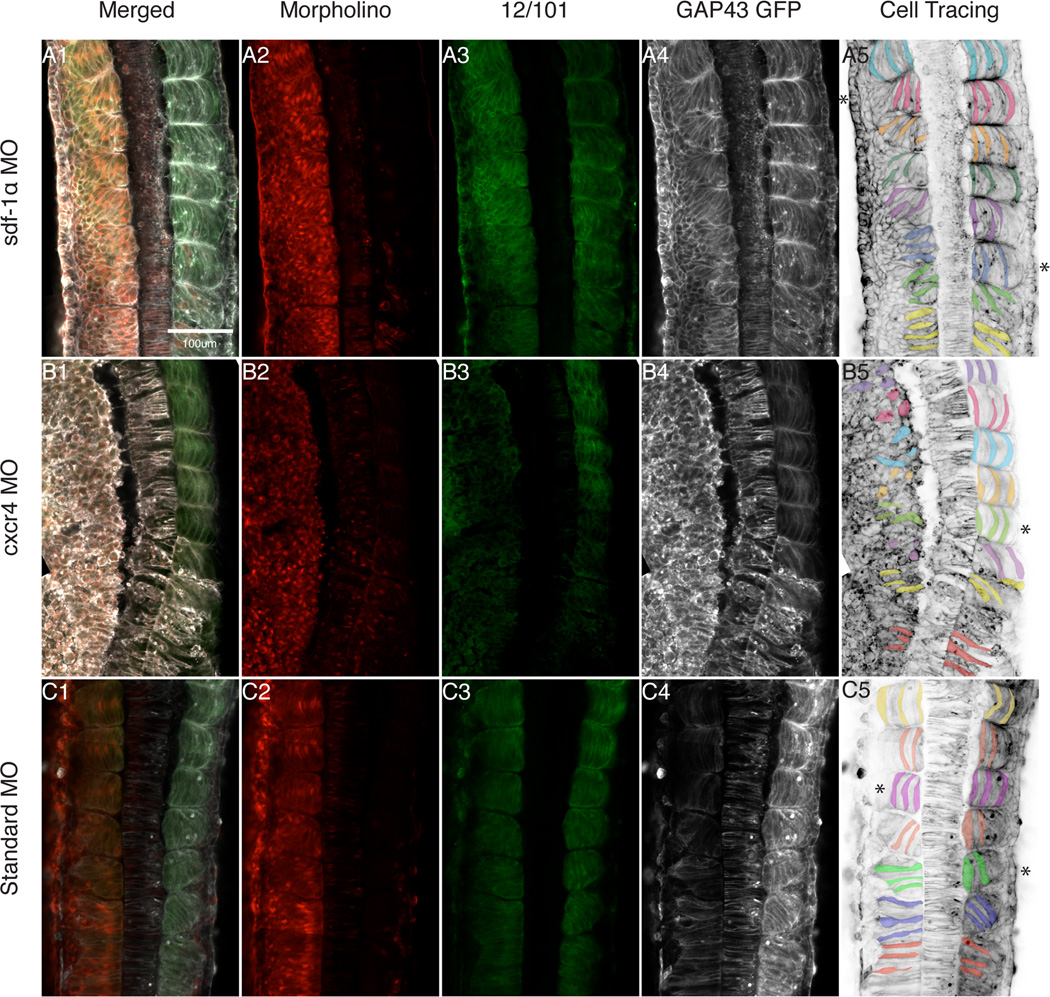

A likely mechanism underlying the abnormal shortening of the anteroposterior axis in sdf-1α and cxcr4 half-morphant embryos is a reduction in the number or organization of the somites. To test this hypothesis we injected embryos at the one-cell stage with mRNA encoding a membrane-targeted GFP (GAP43-GFP) that allows us to visualize the cell shapes associated with somite formation (Moriyoshi et al., 1996). We then injected the specific MO into one blastomere at the 2-cell stage to create half-morphants as previously described. The injected embryos were allowed to develop to stage 24, when approximately 15 somites have formed. Embryos were then stained for 12/101, a muscle-specific antibody, and anti-GFP antibody conjugated to AlexaFluor 647. Montages were made from 20X confocal scans to highlight cell shapes along the anteroposterior axis (Fig 4). We show that the sdf-1α morphant side displays a morphological delay such that approximately 5 somites are at intermediate stages of rotation in comparison to one somite on the control side (Fig. 4A.4–A.5; see asterisks). The GFP expression further shows irregular and incomplete intersomitic boundaries along with misaligned myotome fibers (Fig. 4A.4–A.5). Knockdown of cxcr4 on one side of the embryo led to a more severe phenotypic alteration in comparison to the sdf-1α knockdown (Fig. 4B). The 12/101 expression level is significantly lower on the cxcr4-morphant side in comparison to the control side (Fig. 4B.1–B.3). In addition, the somites on the control side are regularly spaced and consist of elongated and aligned myotome fibers whereas on the cxcr4-morphant side the intersomitic boundaries are undetectable and the cells are irregularly shaped (Fig. 4B.4–B.5). To control for non-specific effects due to the MO, we injected a standard MO (Genetools). As expected the standard-morphant side consists of regularly segmented somites composed of elongated and aligned myotome fibers as indicated by the 12/101 and GFP staining (Fig. 4C). We detected a slight delay of one somite on the standard morphant side, which may reflect a slight left-right asymmetry in somite formation. However, this is very mild in comparison to the left-right asymmetry observed in the sdf-1α half-morphant. Taken together, our results show that knockdown of sdf-1α and cxcr4 significantly disrupts the cell behaviors that lead to somite formation as well as myotome elongation and alignment.

Figure 4. Morpholino depletion of sdf-1α and cxcr4 cause a disruption in somite morphogenesis.

Montages of 20X dorsal scans of stage 26 sdf-1α (A.1), cxcr4 (B.1) and standard (C.1) half-morphants highlight the morphologies of cells in the paraxial mesoderm. (A.2–C.2) The distribution of the MO along one-half of the embryo is indicated by lissamine fluorescence. (A.3–C.3) Whole-mount immunocytochemistry with the muscle-specific antibody, 12/101. (A.4–C.4) Black and white images of GAP43 GFP expression. (A.5–C.5) Inverted images of the GAP43 GFP expression with pseudo-coloring of cells to highlight a subset of cell shapes within the paraxial mesoderm. Asterisk indicates the first fully rotated somite. Scale bar in (A1) applies to all frames. Anterior is at the top.

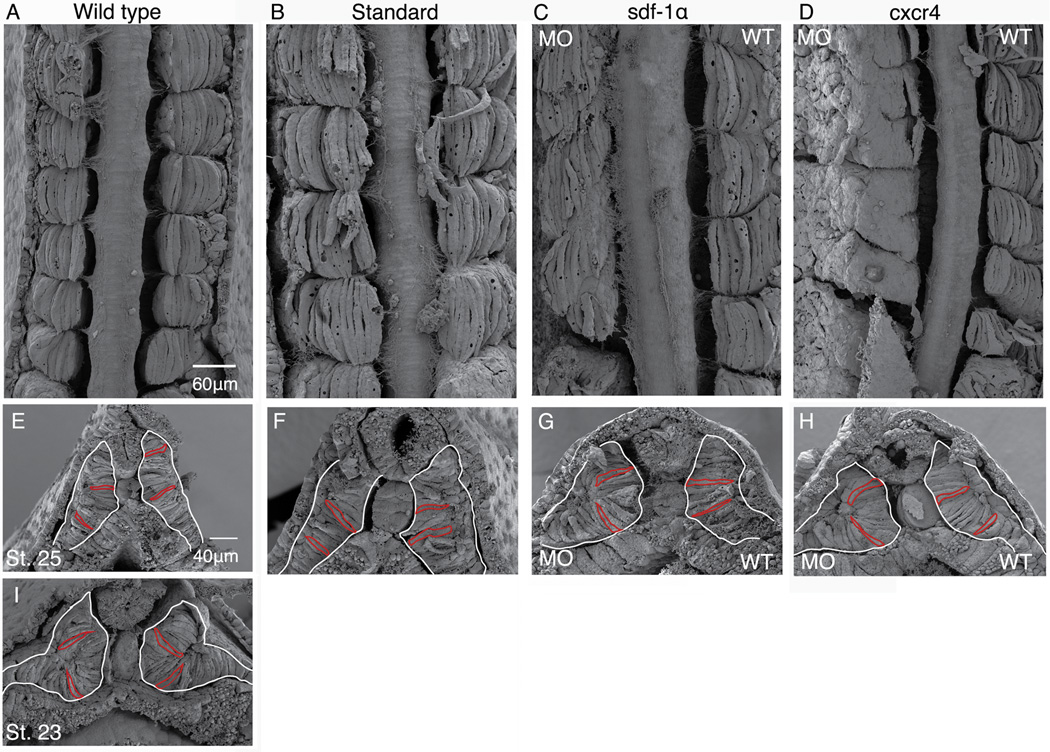

To gain a better understanding of the morphological abnormalities associated with knocking down either sdf-1α or cxcr4, we used scanning electron microscopy (SEM), which allows one to obtain a 3-dimensional view of the organization of multiple tissue structures. We used a fine blade to carefully peel away the ectoderm and expose the underlying mesoderm. In stage 26 wild type embryos, most of the paraxial mesoderm consists of regularly spaced somites composed of elongated and aligned myotome fibers (Fig. 5A). Like the wild type embryos, standard half-morphants also displayed organized somites composed of elongated and aligned myotome fibers (Fig. 5B). In the sdf-1α half-morphant, most cells have undergone rotation, however, the intersomitic boundaries appear irregular (Fig. 5C). In particular, a subset of somitic cells on the morphant side do not appear to be constrained within the intersomitic boundaries in the same fashion as the muscle cells on the control side. In the cxcr4 half-morphants, the somites are irregular and the cells appear flat and disorganized (Fig. 5C). In addition, the intersomitic boundaries are incomplete on the morphant side in comparison to the control side. These SEM images further confirm that knockdown of either sdf-1α or cxcr4 leads to a disruption in the organization of the 3-dimensional structure of the somite with the cxcr4 knockdown displaying a more severe phenotype in comparison to the sdf-1α knockdown.

Figure 5. Scanning electron micrographs reveal cell shapes in sdf-1α and cxcr4 morphant embryos.

Dorsal images of a stage 26 wild type (A) standard half-morphant (B) embryos with somites composed of elongated and aligned myotome fibers. (C) Dorsal image of a stage 26 sdf-1α half-morphant with irregular intersomitic boundaries and a subset of mytome fibers that straddle two segments on the experimental side. (D) Dorsal image of a stage 26 cxcr4 half-morphant embryo with disorganized cells and incomplete intersomitic boundaries on the experimental side. Cross-sections of the PSM in wild type embryos at stages 25 (E) and 23 (I). Cross-section through the PSM of stage 26 standard (F), sdf-1α (G), and cxcr4 (H) half-morphant embryos. White tracing highlights the shape of the PSM and includes both the prospective myotome and dermatome. Red tracings highlight a the shape of a subset of prospective myotome cells. Scale bar in (A) applies to all frames except (E). Anterior is at the top (A–D). Dorsal is at the top (E–I).

The abnormal muscle cell shapes observed in knockdown embryos and in particular, in the cxcr4 morphant embryos, may be due to abnormal cell shapes in the PSM. Work from our lab has shown that cells within the PSM become progressively more elongated in the mediolateral axis as they near the transition zone where somite formation will take place (Afonin et al., 2006). Thus, it may be the case that the disorganization observed among muscle cells and the somites are associated with abnormal cell shapes present within the PSM. To examine this possibility, we imaged by SEM cross sections of the PSM of half-morphants and wild type embryos from stages 23 to 26 (Fig 5E–I). This approach provides a more complete visualization of cell shapes than confocal scans as it allows one to observe the mediolateral alignment (i.e. elongation) of cells throughout the dorsoventral extent of the PSM. We outlined the PSM region, which includes the elongated cells that will give rise to the myotome as well as the cuboidal cells positioned laterally that will give rise to the dermatome. We also outlined a few random prospective myotome cells to highlight their cell shapes. We show that the morphology of the PSM in wild-type and standard half-morphants is similar (Fig. 5E and F). Interestingly, the PSM of sdf-1α and cxcr4 half-morphants consists of elongated cells much like those observed in the control PSM, however, the overall shape of the PSM is more curved on the morphant side than on the control side (Fig. 5G and H). This rounded shape of the PSM in sdf-1α and cxcr4 half-morphants is very similar to the shape of the PSM observed in younger wild type embryos (stage 23; Fig. 5I). Thus, it may be the case that the morphological shape of the PSM in the sdf-1α and cxcr4 knockdown tissue is reflective of a developmental delay. However, knockdown of either sdf-1α or cxcr4 does appear to affect the elongation of prospective myotome cells within the PSM.

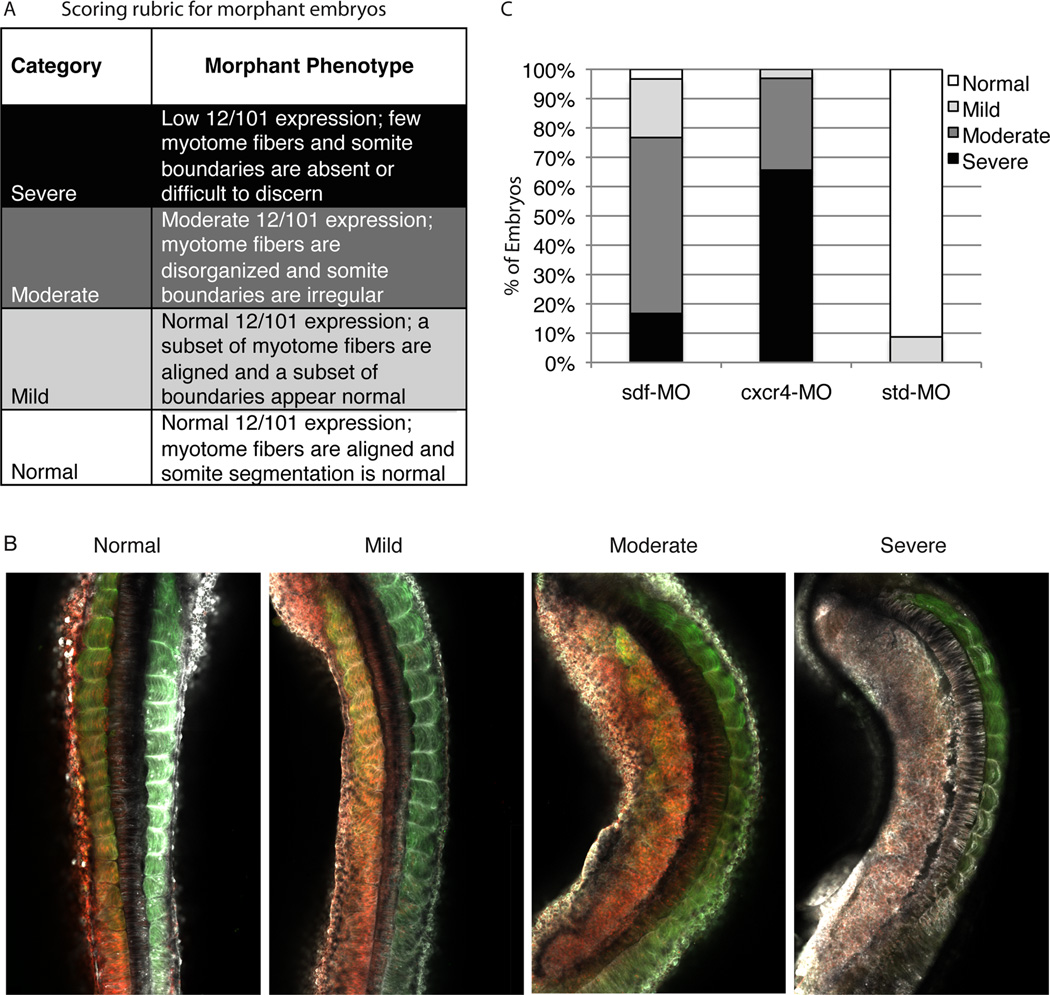

In analyzing half-morphant embryos, we detected phenotypic variations in the sdf-1α and cxcr4 knockdown tissue. To quantify the sdf-1α and cxcr4 half-morphant embryo phenotypes, we developed a scoring rubric with four categories ranging from “severe” to “normal” (see Fig. 6A and B). The scored results were compiled into a stacked bar graph (Fig. 6C). We found that the majority (60%) of the sdf-1α morphants fell into the “moderate” category as they displayed moderate levels of 12/101 staining, but typically displayed irregular intersomitic boundaries and unaligned myotome fibers. Most (66%) of the cxcr4 morphants fell into the “severe” category: they had little or no 12/101 staining, no discernable intersomitic boundaries, and disorganized cells. In contrast, as expected, the standard morphant appeared “normal” in the vast majority of cases (91%): the paraxial mesoderm had normal 12/101 staining, regular intersomitic boundaries and aligned myotome fibers.

Figure 6. Quantification of the sdf-1α and cxcr4 morphant phenotypes.

(A) Using four categories that range from “normal” to “severe”, sdf-1α, cxcr4, and standard morphant phenotypes are scored. (B) A stacked bar graph shows that knockdown of sdf-1α lead to a less severe phenotype in comparison to knockdown of cxcr4. However, knockdown of either sdf-1α or cxcr4 leads to a considerable disruption in muscle formation in comparison to the control and standard morphants.

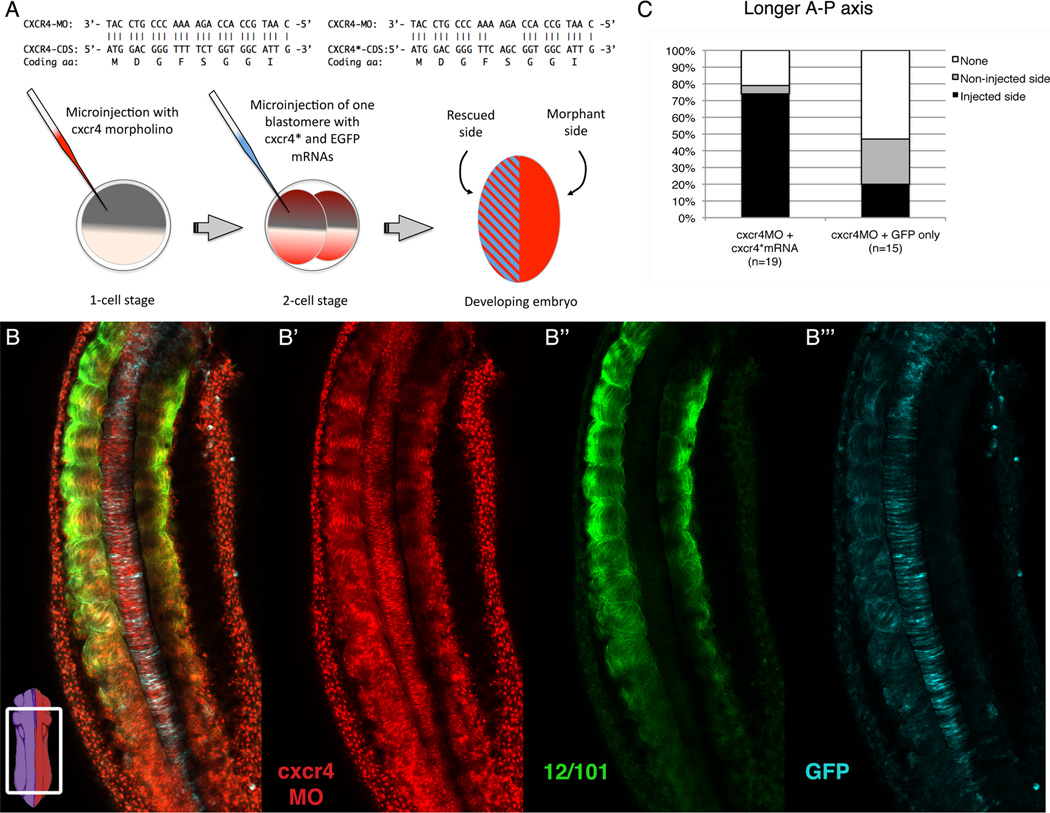

To confirm the specificity of our MOs, we conducted a rescue experiment of the cxcr4 morphants. We designed an mRNA that coded for the cxcr4 protein, but had four consecutive nucleotide changes which makes it resistant to binding the cxcr4 MO. We injected cxcr4-MO at the one-cell stage, followed by injection of the mRNA encoding the MO-resistant cxcr4* and EGFP mRNA, as a lineage tracer, into one of two blastomeres (Fig. 7A). We analyzed the resultant embryos between stages 24 and 26 by confocal microscopy after staining them with 12/101 to visualize the myotome fibers, and with a GFP antibody to visualize the region of the embryo that received the MO-resistant cxcr4* mRNA (Fig. 7B). We show that the presence of the MO-resistant cxcr4* mRNA was able to rescue the morphant phenotype. As expected, given that cxcr4 MO was injected at the one-cell stage, we detected lissamine throughout the embryo (Fig. 7B’). However, EGFP expression was restricted to the half of the embryo expressing the cxcr4* mRNA (Fig. 7B”’). Moreover, the EGFP expression correlates with the half of the embryo that contains the largest number of somites as indicated by 12/101 staining (Fig. 7B”). These observations were quantified by determining which side of the paraxial mesoderm is longer (i.e. had more muscle) by using 12/101 staining (Fig. 7C). We found that in 75% of embryos the side that was injected with MO-resistant cxcr4* mRNA (n=19) displayed a longer axis. As a control, cxcr4 morphant embryos (n=15) were injected at the 2-cell stage with mRNA encoding EGFP only. The majority (53%) of these embryos showed no difference in axis length; those that did display a difference were nearly equally distributed between the injected (20%) and the non-injected (27%) sides. Thus, EGFP expression alone cannot rescue the phenotype. Finally, we also assessed the possibility that the MO-resistant cxcr4* mRNA could act as a non-specific enhancer of myogenesis in our rescue experiments. We, therefore, injected the MO-resistant cxcr4* mRNA into one of two blastomeres of wild type embryos (n=10). We show that in the majority of samples (70%), the longer axis was associated with the non-injected side. Thus, the ectopic expression of the MO-resistant cxcr4* mRNA alone does not lead to increased myogenesis. These results show that the MO-resistant cxcr4* mRNA can rescue the cxcr4 morphant phenotype, thus confirming the specificity of the cxcr4 MO.

Figure 7. Morpholino-resistant cxcr4* mRNA rescues the cxcr4 morphant phenotype.

(A) Top: Comparison between endogenous cxcr4 and MO-resistant cxcr4* 5’ coding region sequences (MO binding site). Bottom: Diagram of the experimental strategy, which consists of embryos injected at the one-cell stage with cxcr4 MO, and at the two-cell stage with MO resistant cxcr4* mRNA and EGFP mRNA (lineage tracer) in one of two blastomeres. (B) A merged image of a stage 25 cxcr4 MO rescued embryo. Bottom left: a diagram of an embryo indicating the region imaged. Subsequent series shows individual channels: B’ lissamine-tagged cxcr4 MO; B” muscle fibers stained with 12/101; and B”’ AlexaFluor anti-GFP indicating the rescued side. Anterior is at the top. (C) Graph showing the percentages in which a specific half of the embryo (injected or non-injected) has a longer axis. In some cases neither side is longer and is thus, scored as “none”.

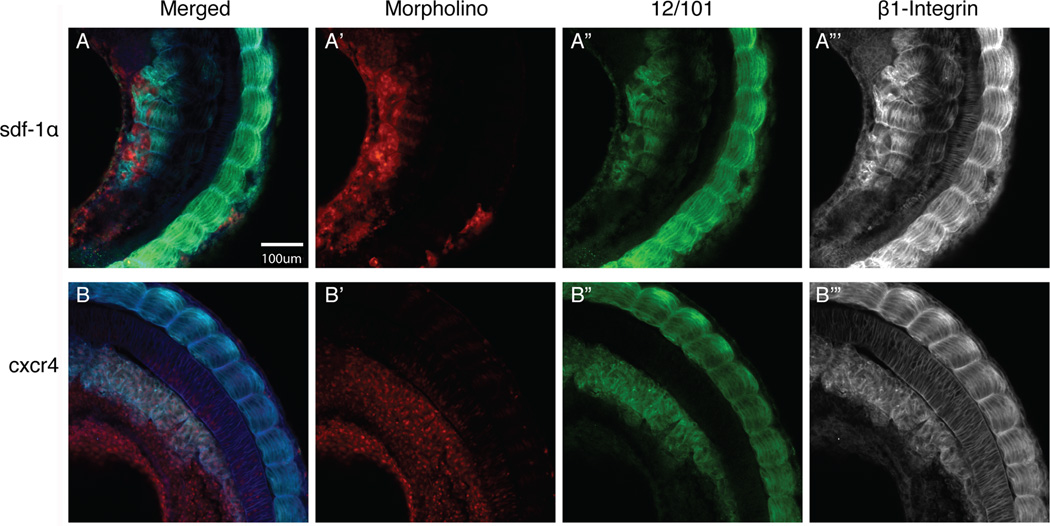

β1-integrin expression is not affected in sdf-1α and cxcr4 depleted embryos

The formation of somites requires the physical separation of a group of cells from the PSM. In X. laevis this process begins with the deposition of fibronectin, closely followed by laminin, to form the intersomitic boundaries (Hidalgo et al., 2009). Integrin expression has been shown to be important as the cells rotate to form aligned myotome fibers (Kragtorp and Miller, 2007). Given that knockdown of either sdf-1α or cxcr4 led to a disruption in somite morphogenesis, we next examined whether β1-integrin expression was effected in these morphants. We found that β1-integrin co-localizes with 12/101 positive cells in the paraxial mesoderm (Fig. 8). In the sdf-1α half-morphant, β1-integrin staining revealed the presence of some somites, but they are unorganized in contrast to the control side, which feature regularly-spaced intersomitic boundaries and aligned myotome fibers (Fig. 8A). In cxcr4 half-morphants, we also observed a disorganization of somitic cells and an absence of clear intersomitic boundaries (Fig. 8B). Thus, the presence of β1-integrin expression among 12/101-positive sdf-1α and cxcr4 morphant cells is not sufficient to drive proper segmentation and myotome elongation and alignment.

Figure 8. β1-integrin distribution in sdf-1α and cxcr4 morphant tissue.

Merged images (MO-lissamine, 12/101 and β1-integrin) of stage 26 (A) sdf-1α and (B) cxcr4 half-morphant embryos. (A’–B’) Distribution of the lissamine-tagged MO. (A”–B”) Expression pattern of the muscle-specific marker, 12/101. (A”’–B”’) Images were converted to black and white to better visualize the distribution of β1-integrin staining on the morphant side in comparison to the wild type side. Scale bar in (A) applies to all frames. Anterior is at the top.

Knockdown of sdf-1α and cxcr4 severely decreases the expression levels of β-dystroglycan and laminin

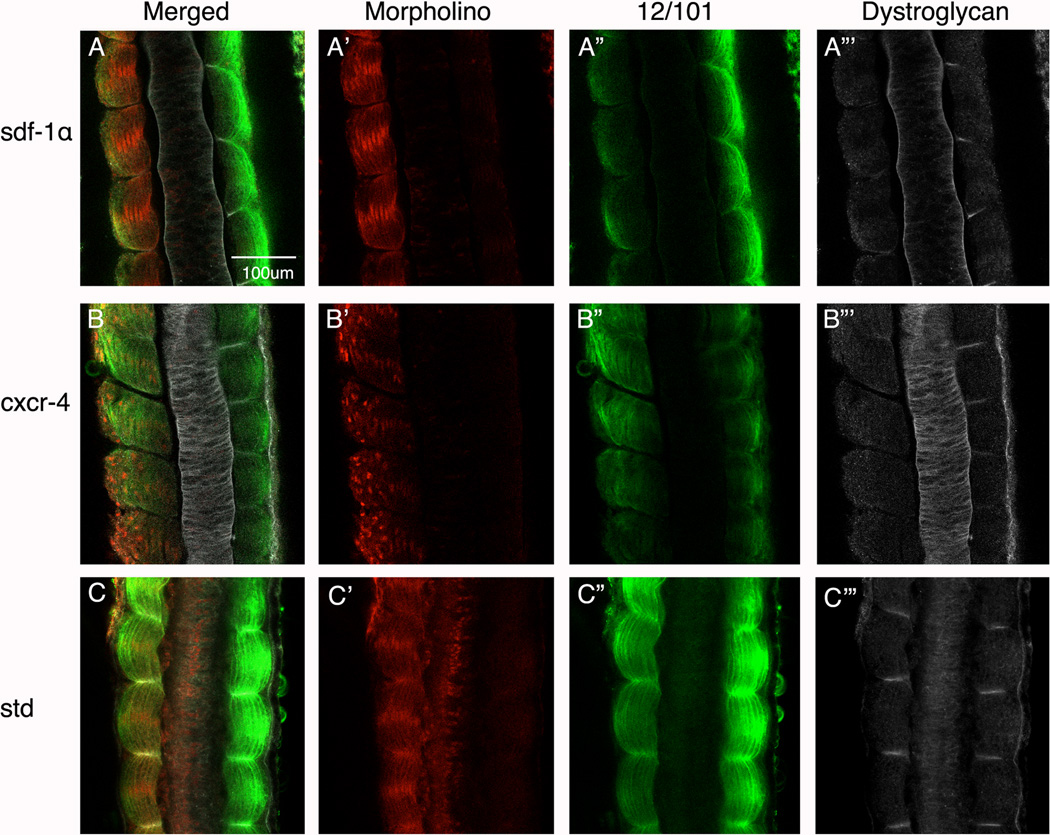

Work by Hidalgo and colleagues (2009) showed that laminin assembly closely follows fibronectin fibrillogenesis during X. laevis somitogenesis. In fact, they showed that expression of β-dystrogylcan, a transmembrane protein that binds laminin through a complex with α-dystrogylcan, coincides with somite rotation and myotome alignment. We show that β-dystroglycan expression is significantly reduced when sdf-1α (Fig. 9A) or cxcr4 (Fig. 9B) are knocked down, respectively. In fact, we selected morphant embryos that scored between “mild” to “moderate” to clearly show that despite the presence of 12/101 expression and somewhat organized somites (Fig. 9A” and B”), β-dystroglycan is not present in significant amounts at the intersomitic boundaries.

Figure 9. Dystroglycan expression in sdf-1α and cxcr4 half morphants.

Stage 26 (A) sdf-1α, (B) cxcr4, and standard (C) half-morphant embryos showing a merged imaged (MO-lissamine, 12/101 and dystroglycan). (A’–B’) Distribution of the lissamine-tagged MO. (A”–B”) Immunolocalization of the muscle-specific marker, 12/101. (A”’–B”’) Images were converted to black and white to better visualize the distribution of dystroglycan on the morphant side in comparison to the control side. Scale bar in (A) applies to all frames. Anterior is at the top.

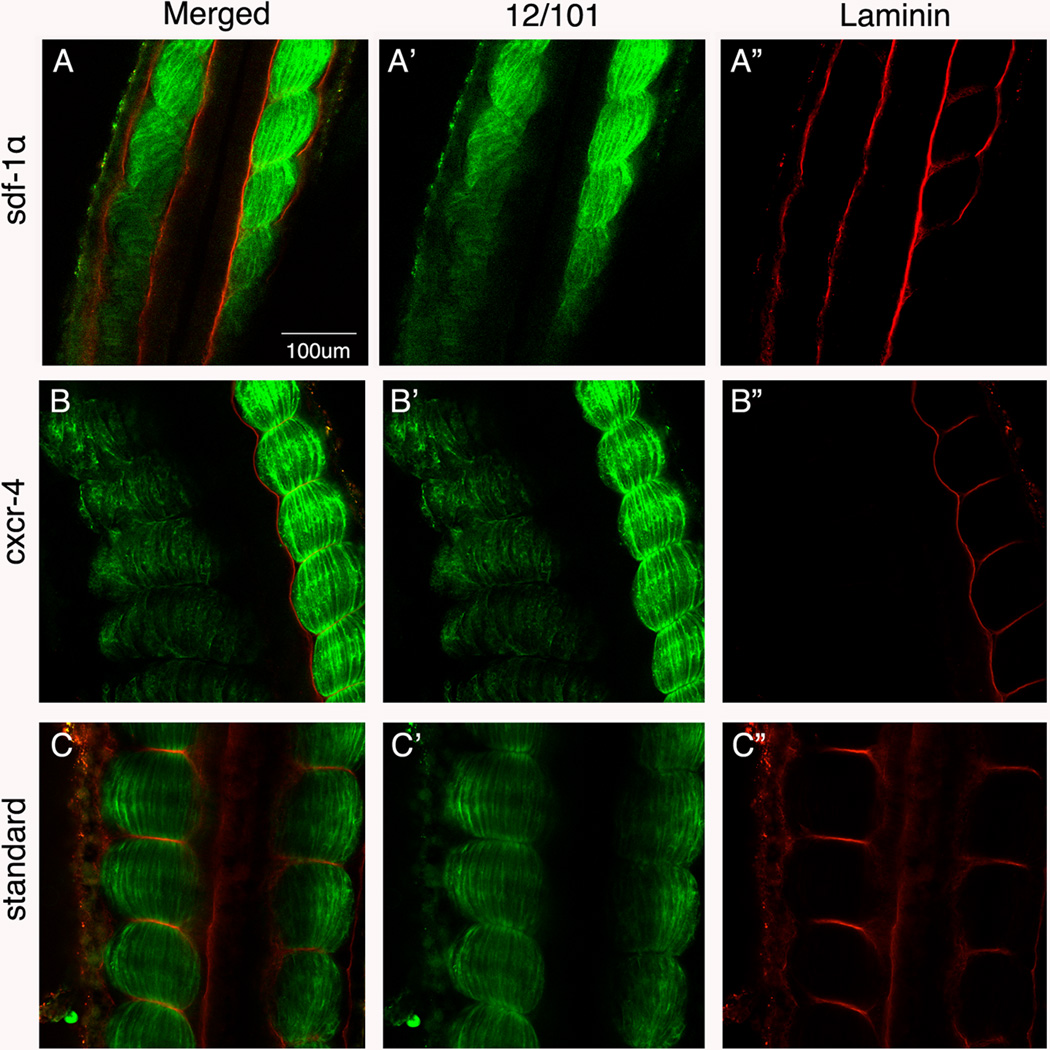

Given the important role of β-dystroglycan in laminin assembly, we next examined whether laminin is properly localized to the intersomitic boundaries in sdf-1α and cxcr4 knockdown embryos. The immunostaining protocol for laminin requires embryos to be fixed in DMSO and methanol. While this fixation procedure eliminates the lissamine signal, the absence of detectable lissamine does not pose a problem for identification of the morphant side, as the phenotype is quite obvious. In the sdf-1α half-morphants, laminin staining was present at the lateral and medial edges of the paraxial mesoderm (Fig. 10A), but was undetectable in the intersomitic boundaries (Fig. 10A”). The situation was more dramatic in the cxcr4 half morphant with laminin being undetectable in the lateral and medial sides of the paraxial mesoderm as well as at the intersomitic boundaries (Fig. 10B”). These results are in stark contrast to the wild type side of the half-morphants and to the standard control, where laminin was localized to the intersomitic boundaries and lateral and medial edges of the paraxial mesoderm (Fig. 10). Thus, knockdown of sdf-1α and, particularly, cxcr4, leads to a complete absence of β-dystroglycan and laminin expression at the intersomitic boundaries.

Figure 10. Laminin expression is severely diminished by the depletion of sdf-1α and cxcr4.

Stage 26 (A) sdf-1α, (B) cxcr4, and (C) standard half-morphant embryos showing a merged imaged (12/101 and laminin). (A’–C’) Distribution of the muscle-specific marker, 12/101. (A”–C”) Immunolocalization of laminin on the morphant side in comparison to the control side. Scale bar in (A) applies to all frames. Anterior is at the top.

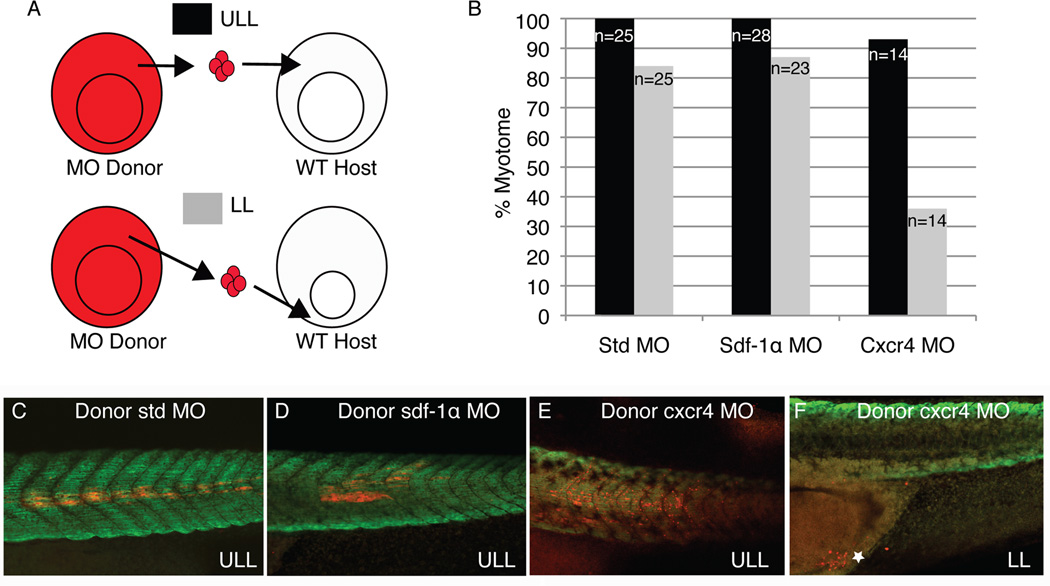

Transplantation experiments reveal that cxcr4 is required for the migration of cells from the lower blastopore lip to the presomitic mesoderm

Given the role of cxcr4 as the receptor for sdf-1α, we next employed a series of transplantation experiments to examine whether knockdown of cxcr4 acts in a cell-autonomous fashion. Previous work from our lab showed that cells positioned around the dorsal blastopore lip of the gastrula take different trajectories to give rise to myotome fibers at precise locations along the anteroposterior axis (Krneta-Stankic et al., 2010). Cells located in the upper lateral blastopore lip (ULL) undergo convergence and extension movements to give rise to myotome fibers in the central region of the somites along the anteroposterior axis. In contrast, cells from the lower blastopore lip (LL) migrate around the blastopore to join the presomitic mesoderm (PSM) and form myotome fibers towards the posterior end of the axis. Given these differences, we proceeded to transplant morphant cells to either the ULL or LL region of wild type host embryos during gastrulation (Fig. 11A). Interestingly, cxcr4 morphant cells transplanted to the ULL region gave rise to myotome fibers in over 90% of cases, which was comparable to cells grafted from either sdf-1α or standard morphants (Fig. 11B). Further, the grafted morphant cells formed elongated myotome fibers that expressed the muscle-specific antibody, 12/101 (Fig. 11C–E). In contrast, cxcr4 morphant cells grafted to the LL region of wild type embryos gave rise to myotome in only 36% of cases (Fig. 11B). However, cells grafted from sdf-1α and standard morphants gave rise to myotome fibers in over 80% of cases. In fact, the majority of the grafted cxcr4 morphant cells remained near the blastopore (Fig. 11F, see white star). Thus, these results show that knockdown of cxcr4 specifically disrupts the movement of cells from the LL to the PSM, where they eventually form dorsal myotome fibers.

Figure 11. Cell transplantations reveal a role for cxcr4 in the migration of lower lip mesoderm cells.

(A) Cells from standard, sdf-1α, or cxcr4 morphant embryos were grafted from the upper lateral lip (ULL) region of the blastopore at the mid-gastrula stage to either the ULL or lower lip (LL) region of wild type host embryos at the same stage. Grafted embryos developed to stage 39 at which time their ability to form myotome fibers was determined (B). Confocal images showing that standard (C), sdf-1α (D), and cxcr4 (E) morphant cells give rise to myotome fibers when grafted to the ULL region of a wild type embryos. (F) A confocal image showing that cxcr4 morphant cells grafted to the LL region fail to migrate dorsally and remain closely associated with their original position near the future anus of the tadpole (see white star).

RhoA activation is impaired in the absence of sdf-1α signaling

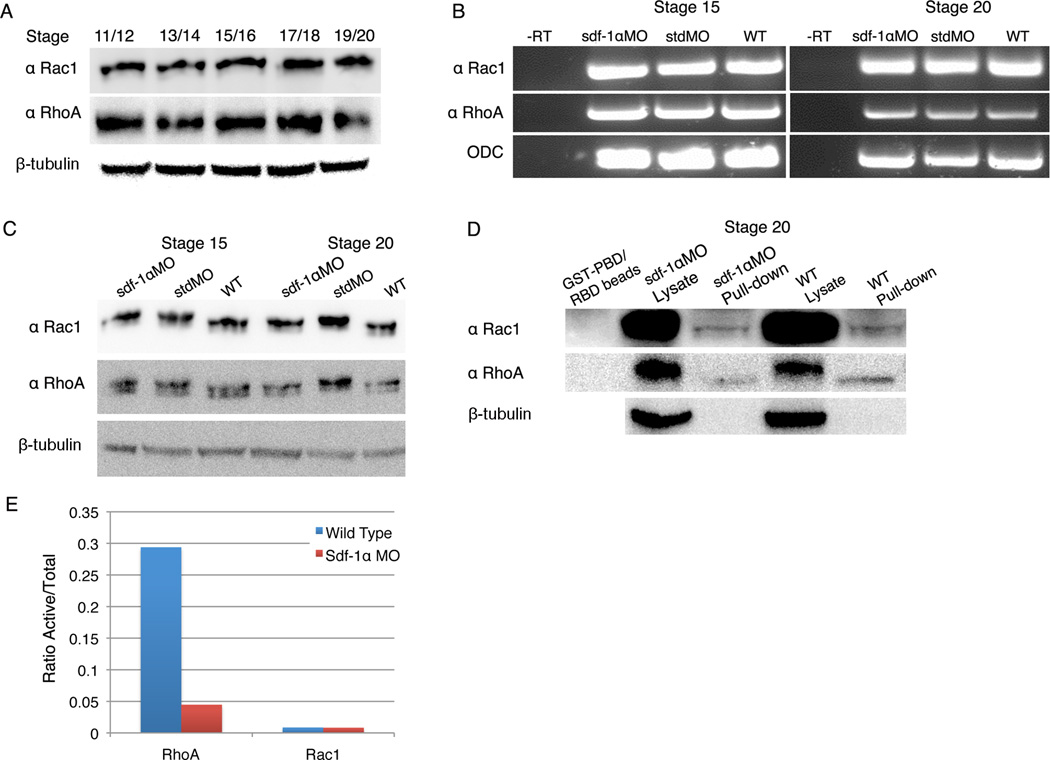

Cell culture studies have shown that the sdf-1α signaling pathway mediates cell movements by directly activating RhoA (Tan et. al., 2006) and Rac1 (Bartolome et. al., 2004). These small GTPases are actin regulatory molecules that are known to regulate cell shape changes, protrusive activity, lamellipodia formation, migration, and cell adhesion (Jaffe and Hall, 2005). In X. laevis, RhoA and Rac1 are involved in polarized cell contact behaviors that drive gastrulation movements (Tahinci and Symes, 2003). We thus hypothesized that the sdf-1α signaling pathway works through RhoA and Rac1 to regulate the cell contact behavior underlying somite rotation and myotome alignment. Previous work showed that rac1 (Habas et al; 2003) and rhoA (Wunnenberg-Stapleton et al; 1999) are expressed at the mRNA level throughout X. laevis development. To test our hypothesis that Rac1 and RhoA are downstream targets of the sdf-1α signaling pathway during somitogenesis, we first confirmed through Western blot analysis that Rac1 and RhoA are present during the stages associated with somite formation (Fig. 12A). Next, we used RT-PCR to examine whether knockdown of sdf-1α affects the mRNA levels of rac1 and rhoA at stage 15, which corresponds with the onset of somite formation, and stage 20, when the first 6–7 somites have formed. Regardless of the stages, we found no difference in rac1 or rhoA mRNA levels between the controls (stdMO and wild type) and sdf-1α morphants (Fig. 12B). Using Western blot analysis we then determined that knockdown of the sdf-1α signaling pathway did not affect Rac1 and RhoA protein levels (Fig. 12C).

Figure 12. RhoA and Rac1 activation through sdf-1α signaling pathway.

(A) Western blot analysis reveals the constant presence of Rac1 and RhoA protein between X. laevis stages 11 and 20. β-Tubulin was used as a protein loading control. (B) RT-PCR analysis shows that Rac1 and RhoA are expressed in sdf-1α morphants at the same level as in the standard morphants and wild type embryos at stages 15 and 20. ODC was included as a loading control. (C) Western blot analysis shows no difference in total Rac1 and RhoA protein levels between sdf-1α morphants and controls (standard morphant and wild type embryos) at stages 15 and 20. β-Tubulin was used as a protein loading control. (D) Western blot analysis shows the level of activated RhoA and Rac1 in stage 20 sdf-1α morphant and wild type embryos. β-Tubulin was included as a protein loading control. (E) A graph showing the ratio between active and total Rac1 and RhoA proteins at stage 20 in sdf-1α morphants and controls.

Since Rac1 and RhoA are post-translationally regulated, we predicted that the sdf-1α signaling pathway is involved in the activation of these proteins. Both Rac1 and RhoA are small GTPases that cycle between a GTP-bound “active” and GDP-bound “inactive” state. It is in the GTP-bound state that Rac1 and RhoA influence actin cytoskeletal dynamics. To assay for the activated form of these proteins, we used a pull-down assay to isolate the GTP-bound forms of Rac1 and RhoA from X. laevis embryos (Habas et al 2003). GST-PBD (Benard et al. 1999) and GST-RBD (Ren et al. 1999) fusion proteins were used to isolate “active” GTP-bound Rac1 and RhoA from X. laevis embryos. Untreated wild type embryo lysates were used as a positive control for total (GTP and GDP-bound) Rac1 and RhoA protein. In addition, GST-PBD and GST-RBD beads served as a negative control for Rac1 and RhoA. Western blot analysis showed that the active form of RhoA is lower in sdf-1α morphants than in wild type embryos at stage 20 (Fig. 12D and E). We were unable to determine whether knockdown of sdf-1α affected the activation levels of Rac1 because of the difficulty in detecting activated Rac1 in wild type embryos. However, we were able to show that the sdf-1α signaling pathway is involved in activating RhoA in vivo and at stages associated with X. laevis somitogenesis.

DISCUSSION

We set out to determine the role of sdf-1α, and its receptor, cxcr4, in X. laevis somitogenesis. Knockdown of either sdf-1α or cxcr4 leads to a disruption in somite formation and muscle cell alignment. We propose that the sdf-1α signaling pathway regulates somitogenesis, initially by regulating the migratory behavior of cells from the LL region of the gastrula to the dorsal aspect of the PSM. Once cells reach the PSM and undergo segmentation, sdf-1α signaling is required for the expression of β-dystroglycan, which is important for somite rotation as well as laminin assembly at the intersomitic boundary. The proper establishment of the intersomitic boundaries then supports the elongated cell shape and alignment of the myotome fibers.

Sdf-1α signaling pathway in X. laevis

Close examination of the knockdown of sdf-1α and cxcr4 reveals a range of defects in somite morphogenesis. For example, the phenotypes of sdf-1α half-morphants ranged from “mild” to “moderate.” The paraxial mesoderm of the sdf-1α morphant consisted of a subset of somites composed of aligned myotome fibers, however, the majority of the somites had difficulty in completing the 90° rotation in comparison to the control side. In addition, many intersomitic boundaries were irregular and a subset of myotome fibers commonly straddled two different segments. The phenotype of cxcr4 half-morphant embryos were more pronounced and ranged from “moderate” to “severe”. In many cases only a small number of cells from the cxcr4 half-morphant side were positive for 12/101. In addition, the intersomitic boundaries were either absent or difficult to discern and cells in the paraxial region failed to elongate. It may be the case that the difference in severity between the sdf-1α and cxcr4 morphant phenotypes is due to different isoforms of sdf-1 present in X. laevis. The human version of sdf-1 undergoes differential RNA splicing to form two isoforms, sdf-1α and sdf-1β (Shirozu et al., 1995). In X. laevis, sdf-1α and sdf-1, a mammalian homolog sdf-1β, have been characterized. The morpholino used in this study specifically targeted sdf-1α. It may be the case that sdf-1, which begins to be expressed at the early tailbud (st. 18) and is found in adult muscle tissue (Braun et al., 2002), is still present in sdf-1α depleted tissue. If this were the case then sdf-1 could compensate for the absence of sdf-1α, thus, resulting in a milder phenotype. This explanation would also account for the more severe phenotype resulting from the knockdown of the receptor, cxcr4, as absence of this receptor would obliterate the transduction of both the sdf-1 and sdf-1α signals.

Sdf-1α and its receptor, cxcr4, are required for the formation of the intersomitic boundary

The deposition and assembly of the extracellular matrix in the intersomitic boundaries plays a key role in myotome alignment. Fibronectin is the first extracellular matrix deposited in the intersomitic boundaries (Wedlich et al., 1989). Kargtorp and Miller (2007) showed that integrin expression is required for proper deposition of fibronectin at the intersomitic boundaries and that failure to express integrin led to a disruption in somite rotation. In addition, Hidalgo and colleagues (2009) showed that laminin is deposited in the intersomitic boundaries after fibronectin and requires β-dystroglycan expression in order to become properly assembled at the intersomitic boundaries. Our results indicate that β1-integrin expression is present in sdf-1α and cxcr4 morphant somites. However, both β-dystroglycan and laminin are virtually undetectable in the morphants, particularly in the cxcr4 knockdown embryos, indicating a clear link between the sdf-1α signaling pathway and β-dystroglycan and laminin expression. Give our results, we propose that the sdf-1α signaling pathway is not needed to initiate segmentation as integrin expression is present in the knockdowns; however, sdf-1α signaling is needed for β-dystroglycan and laminin expression. Failure to express β-dystroglycan and laminin within the paraxial mesoderm leads to the formation of incomplete and irregular intersomitic boundaries, which subsequently leads to the failure of somitic cells to rotate and form aligned myotome fibers.

Cxcr4 is important for the movement of cells from the lower blastopore lip to the dorsal PSM

Directed cell movements and cell shape changes play an important role in the elongation of the embryonic axis. We found that knockdown of sdf-1α and cxcr4 leads to a shortening of the posterior axis. A major mechanism underlying axis elongation is convergent extension (Keller and Danilchick, 1988). Using Keller sandwiches we show that knockdown of sdf-1α or cxcr4 does not affect convergent extension. Supporting this observation, SEM images of the PSM indicate that sdf-1α and cxcr4 morphant cells adopt mediolateral elongated cell shapes indicative of normal mediolateral intercalation behavior, which is known to drive convergent extension of the paraxial mesoderm (Shih and Keller 1992). An alternative mechanism influencing axis elongation are the cell movements associated with somite formation. Our cell transplantation experiments revealed that cells from the lower blastopore lip require cxcr4 to undergo the proper cell movements to join the posteriorly-lengthening PSM. Work from our laboratory has shown that cells from the lower blastopore lip region of the gastrula contribute significantly to the formation of trunk and posterior myotome fibers (Krneta-Stankic et al., 2010). Therefore, it seems likely that the contribution of lower lip cells to the paraxial mesoderm is substantially reduced in the absence of proper migration in the cxcr4 morphants. We posit that the combination of abnormal migration of cells from the lower lip region of the gastrula with the abnormal formation of somites leads to the shortening of anteroposterior axis.

The role of sdf-1α signaling pathway in the activation of RhoA and Rac1

Prior studies have shown that sdf-1α activates the Rho family of GTPases during the migration of Jurkat T cells (Tan et al., 2006), and endothelial cells (Carretero-Ortega et al., 2010), as well as during melanoma cell invasion (Bartolome et al., 2004) and axonal elongation (Arakawa et al., 2003). These studies used cell culture as a model system, however, no in-vivo system had examined whether sdf-1α signaling activates the Rho family of GTPases during embryogenesis. Thus, we set out to determine whether the sdf-1α signaling pathway activates RhoA and Rac1 in-vivo and during the stages associated with somitogenesis in X. laevis. Prior studies in X. laevis showed that Rac1 and RhoA mRNA are detectable throughout development (Wunnenberg-Stapleton et al., 1999) and are involved in regulating gastrulation movements (Habas et al., 2003; Tachini and Symes, 2003). Using Western blot analysis, we confirmed that Rac1 and RhoA are present during the stages associated with somite morphogenesis. We employed a pull-down assay developed by Habas and colleagues (2003), to show that activated levels of RhoA are significantly lower in the sdf-1α knockdown embryos than in wild type embryos, thus providing evidence that the sdf-1α signaling pathway leads to RhoA activation. It may also be the case that RhoA activation occurs indirectly, possibly through β-dystroglycan. Support for this hypothesis comes from the observation that β-dystroglycan can activate small GTPAses such as Rac1 and RhoA to transduce mechanical signals in rat adult muscle (Chockalingam et al., 2002). If this were the case, then in sdf-1α morphant tissue, where β-dystroglycan expression levels are low, RhoA activation would subsequently be affected as well. The reduction in RhoA activiation during the stages associated with somitogenesis would likely impact the ability of cells to undergo the normal cell behaviors associated with somite rotation and attachment to the intersomitic boundaries to form aligned myotome fibers.

Sdf-1α signaling and somite morphogenesis

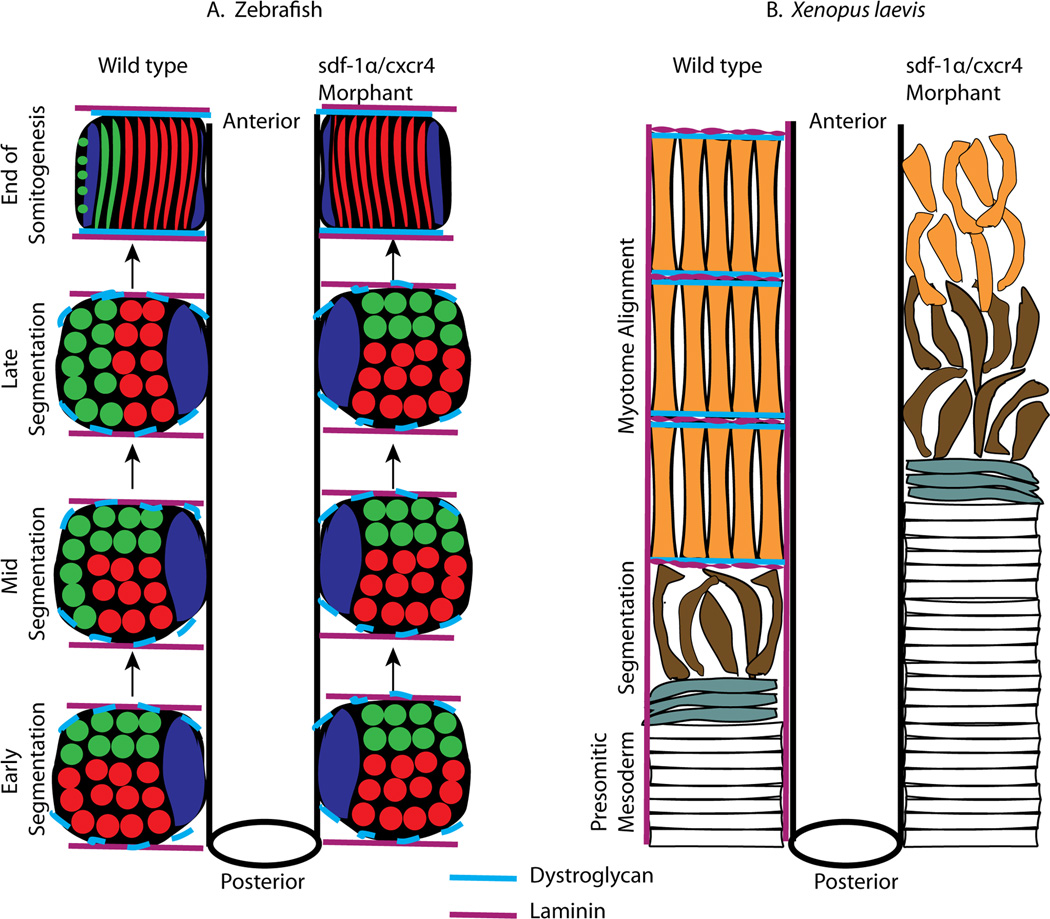

Until recently, somite rotation was a unique characteristic of X. laevis somite morphogenesis. However, elegant time-lapse imaging by Hollway and colleagues (2007) showed that at mid-somitogenesis (15-somites), a subset of somitic cells in zebrafish undergo a 90° rotation. These researchers went on to show that the sdf-1α signaling pathway is important for this rotation as it guides the movement of anterior somitic cells to the lateral edge of the somite (see green cells; Fig. 13A). In sdf-1α morphant zebrafish, anterior somitic cells failed to migrate to the lateral edge. Because of this inability to migrate, these cells subsequently do not differentiate and, instead, are dispersed throughout the somite. In addition to anterior somitic cells, the zebrafish somite is also comprised of adaxial and posterior cells, which undergo normal differentiation in the absence of sdf-1α signaling (Fig. 13A). In contrast, we observed that knockdown of sdf-1α signaling in X. laevis leads to a more severe phenotype as the vast majority of cells within the somite are disorganized and fail to differentiate into muscle (Fig. 13B). Given that the X. laevis somite consists primarily of myotome cells all of which undergo rotation, it seems logical that a signaling molecule that perturbs somite rotation would likely impact the majority of the cells within the X. laevis somite. Thus, much like the anterior somitic cells in zebrafish, the myotome cells of X. laevis fail to rotate and complete their final stages of myogenesis as indicated by the low detection level of the muscle-specific marker, 12/101. In zebrafish, sdf-1α acts as a cytokine to recruit the movement of anterior somitic cells to the lateral edge. In X. laevis, cells from the lower blastopore lip are recruited to the PSM likely through an sdf-1 signal. However, once in the PSM, sdf-1α is then important for the expression of β-dystroglycan and the subsequent assembly of laminin in the intersomitic boundaries (Fig. 13B). Given that somite rotation occurs soon after the formation of the intersomitic boundaries (Afonin et al., 2006), failure to build a proper intersomitic boundary would likely lead to a failure to complete rotation and form myotome fibers that are elongated and in parallel alignment. In zebrafish, somite rotation occurs much later and is not associated with intersomitic boundary formation (Henry et al., 2005). The early intersomitic boundary in zebrafish is composed of laminin and fibronectin as well as low levels of β-dystroglycan (Snow and Henry, 2009). Once the slow-twitch muscle fibers begin to translocate laterally (Devoto et al., 1996), the extracellular matrix (ECM) within the intersomitic boundaries begins to change such that fibronectin decreases and β-dystroglycan increases (Snow and Henry, 2009). Thus, the maturation of intersomitic boundaries in zebrafish is influenced by the lateral movement of slow-twitch muscle fibers, which occurs independently of somite rotation and is not disrupted by the knockdown of sdf-1α. In contrast, in X. laevis the formation of the intersomitic boundaries is closely associated with cell rotation. Thus, although sdf-1α signaling is involved in somite morphogenesis in both zebrafish and X. laevis, the temporal and spatial deployment of this signaling pathway in relationship to the cell behaviors associated with somite rotation is significantly different.

Figure 13. A comparison of the role of sdf-1α signaling during somite morphogenesis in zebrafish and X. laevis.

(A) A schematic representation of a dorsal view of somite morphogenesis comparing the series of events between the wild type and sdf-1α knockdown in zebrafish. In the wild type enbryo, the anterior somitic cells (shown in green) migrate to the lateral edge via an attraction to an sdf-1α signal. These anterior somitic cells will eventually elongate and cells in the rostral position will form hypaxial and appendicular muscle precursors while the cells positioned more caudally will form fast twitch muscle and the dorsal fin. Shown in red are the posterior somitic cells, which will give rise to fast twitch muscle fibers and in blue are the adaxial cells which will give rise to slow twitch muscle fibers. In the absence of sdf-1α signaling, the anterior somitic cells fail to rotate and differentiate. However, the posterior somitic cells (red) and adaxial cells (blue) are able to undergo normal differentiation. (Adapted from Hollway et al., 2007). In zebrafish, the intersomitic boundaries are first composed of laminin (violet) and low levels of β-dystroglycan. Once the adaxial cells migrate to the lateral edge, β-dystroglycan (light blue) levels increase (end of somitogenesis). The dynamics of the intersomitic boundaries are likely unaffected by the knockdown of sdf1-1α signaling. (B) A schematic representation of a dorsal view of somite morphogenesis in X. laevis. In the wild type embryo, at the anterior end of the PSM cells begin to separate to form a somite. At this time, β-dystroglycan (light blue) is expressed and is associated with laminin (violet) assembly at the intersomitic boundaries. The somitic cells complete a 90° rotation such that each elongated myotome fiber is in contact with the intersomitic boundaries at either end of the somite. Unlike zebrafish in which somite rotation occurs much later (mid segmentation), in X. laevis, somite rotation occurs almost coincident with somite segmentation. In the sdf-1α and cxcr4 knockdown embryos, the PSM cells initiate somite formation. However, dystroglycan is not expressed and laminin assembly does not occur at the intersomitic boundaries. The morphant somitic cells attempt to rotate, but are unable to complete this process and fail to form elongated and aligned myotome fibers. The failure to make stable contacts with the intersomitic boundaries disrupts the final stages of myotome formation. Given that the majority of cells within the X. laevis somite are impacted by the abnormal organization of the intersomitic boundaries, the resultant phenotype in X. laevis is much more disrupted in comparison to zebrafish.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Fertilization and Harvesting of Xenopus laevis Embryos

Using standard methods, eggs were retrieved from X. laevis females 18–22 hours post-HCG injection and fertilized in vitro with X. laevis male sperm in 1/3 MBS (Modified Barth’s Solution) at room temperature (Danilchick et al., 1991). Once fertilized, embryos were dejellied in a 2% cysteine solution and allowed to develop to the required stage according to the Nieuwkoop and Faber (1994) staging table.

Microinjections of Morpholinos and mRNAs

To determine the role of sdf-1α and cxcr4 in somitogenesis, morpholinos were used to knockdown their expression levels. Sdf-1α antisense oligonucleotide morpholino (MO) conjugated to lissamine, with sequence 5’-CAGAGCTAGAGTCCTTATGTCCATG-3’, and a cxcr4 antisense oligonucleotide MO conjugated to lissamine, with the sequence 5’-CAATGCCACCAGAAAACCCGTCCAT-3’, were ordered from Gene Tools LLC as previously described (Fukui et al., 2007). As a control, we used a standard that targets human β-globin pre-mRNA and controls for any non-specific morpholino effects with the sequence 5’-CCTCTTACCTCAGTTACAATTTATA-3’ (www.gene-tools.com/node/23#standardcontrols). Using a Drummond Nanoinject II Automatic Oocyte Injector, one of two blastomeres was injected with one of the following morpholinos: 36.8 ng of sdf-1α MO, 18.4 ng of cxcr4 MO, 36.8 ng of std MO (Fig. 1). Following injections, embryos were transferred into a post-injection solution (1/3X MBS + 2% Ficoll) and allowed to develop to the appropriate stage in a 16°C incubator. Embryos were fixed at various stages of somitogenesis (stage 15–28) in MEMFA for 1 hour at room temperature and then transferred to 100% methanol for long-term storage.

To describe the changes in cell shapes associated with somite formation and rotation, we injected embryos at the one or two-cell stage with ~600pg of an in vitro transcribed RNA (from a NotI-linearized plasmid template pGAP43-GFP) encoding a membrane-tagged GFP protein (Moriyoshi et al., 1996; Kim et al., 1998). Injected embryos were cultured to various stages, fixed, and stained with an anti-GFP antibody conjugated to AlexaFluor 647 (Molecular Probes).

For the cxcr4 MO rescue experiment, we created a MO-resistant cxcr4* mRNA by changing four nucleotides at the center of the cxcr4 MO binding site to prevent direct interaction with the cxcr4 MO while maintaining the cxcr4 amino acid sequence (Fig. 6A). To generate this construct, we amplified the cxcr4 cDNA using the following primers: 5’-ACAGCTCGAGATGGACGGGTTCAGCGGTGGCATTGATATCAATATT-3’ and 5’-CATGACTAGTTTAGCTCGAGTGAAAACTGGAG-3’. The sequence was then cloned into pSD64TF plasmid (gift by P. Welling). Similarly, EGFP cDNA was amplified with the following primers: 5’-ACAGCTCGAGGATCTATGGTGAGCAAGGGCGAGG-3’, and 5’-CATGACTAGTCTAGGATCTCTTGTACAGCTCGTC-3’ from pIRES2-EGFP (Invitrogen) and cloned into pSD64TF backbone. Cxcr4* and EGFP mRNAs were then synthesized using mMESSAGE machine SP6 in vitro transcription kit (Ambion). Embryos were injected at the 1-cell stage with 36.8ng of cxcr4 MO. At the 2-cell stage one blastomere was then injected with 0.5ng of cxcr4* mRNA and 0.2ng of EGFP mRNA as a tracer. Negative controls received only EGFP mRNA. Embryos were de-enveloped around stages 13 and 15 were fixed between stages 24 and 26 as previously described, and then stained with the 12/101 antibody followed by an IgG goat-anti mouse Alexa Fluor 488 and with an anti-GFP-647 conjugate (Invitrogen). Dorsal images of processed embryos were taken using a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope.

Immunohistochemisty and Confocal Imaging

To determine the effects of knocking down sdf-1α and cxcr4 on somites, we used a standard immunostaining protocol described in the Cold Spring Harbor manual to visualize specific proteins (Hemmati-Brivanlou and Melton, 1994). Primary antibodies used in this study were skeletal-muscle specific 12/101 (Kintner and Brockes, 1984), β1-integrin (8C; DSHB), β-dystroglycan supernatant (DSHB) and laminin (Sigma). Secondary antibodies included IgG goat-anti mouse Alexa Fluor 488, 555, and 647 (Molecular Probes). Stained embryos were then cleared in a benzyl benzoate/benzyl alcohol (2:1) solution and mounted dorsally on slides with handmade wells. Embryos were imaged on either a Nikon PCM2000 or a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope and their images were captured at 1.8 µm intervals through either a 10× or 20× objective.

Scanning Electron Microscopy Imaging

Stage 26 wild type and morphant embryos were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehde in 1×PBS solution for 24 hours at 4°C. Fixed embryos were then transferred to 1× PBS and the epithelium and ectoderm were carefully peeled back from the embryo using a surgical knife. The embryos were then rinsed in 1× PBS and then dehydrated with increasing concentrations of ethanol (from 25% to 95%) and stored at 4°C in 100% ethanol for 24 hours. Next, embryos were dried in a critical point dryer for approximately one hour. They were mounted dorsally or as cross-sections on metal stubs using PELCO isopropanol-based graphite paint, dried overnight, coated with a iridium target using a 208HR High Resolution Sputter Coater (Cressington), and imaged using the Zeiss Ultra 55 Field emission scanning electron microscope.

Cell Transplantations

To observe the migratory path of morphant cells, we injected sdf-1α, cxcr4, or standard morpholino into X. laevis at the one-cell stage. Injected embryos were transferred to 1/3X MBS containing 2% Ficoll and after 24 hours they were moved to 1/3X MBS. Embryos were allowed to develop to the desired stage and then screened for fluorescence using an Olympus SZX12 fluorescence-dissecting microscope. At the appropriate stage, the protective vitelline envelope was removed from both host and donor embryos using forceps. Eyebrow and eyelash tools were used to remove approximately 10–50 cells from donor embryos. Cell transplantations were performed in 2% agar coated Petri dishes containing 1X MBS and then transferred to 2% agar coated Petri dishes containing 1/3X MBS for long-term culture. At stage 39, embryos were fixed in 1X MEMFA (100mM MOPS pH 7.4; 2mM EGTA, 1mM MgSO4; 3.7% formaldehyde) for one hour at room temperature or overnight at 4° Celsius, cleared in a benzyl benzoate/benzyl alcohol (2:1) solution, mounted laterally on slides, and then imaged on a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope.

Keller Sandwiches

To determine whether sdf-1α and cxcr4 are required for convergent extension movements, Keller sandwiches were made as previously described in Keller and Danilchik (1988). This involved injecting 38.8ng of cxcr4 MO, 73.6ng of sdf-1α MO and 73.6ng of standard MO at the one-cell stage. At the onset of gastrulation, sandwiches of dorsal marginal zone tissue were made and cultured in 1/2X MBS overnight, fixed and imaged at the early tailbud stage under brightfield with an Olympus SZX12 dissecting microscope. The amount of elongation was assessed for all sandwiches as previously described (Wallingford et al., 2001). This consisted of measuring the length of the longest aspect of each sandwich and the width of each sandwich at the constriction point between the involuting marginal zone (IMZ) and non-involuting marginal zone (NIMZ). The length-to-width ratio (LWR) was calculated for each sandwich using the public domain NIH Image 1.62 program (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/nih-image/), and the significant differences among sandwiches was calculated by using the Student’s t test (P<0.05).

RT-PCR

RNA was extracted from embryos using the RNeasy Plus Universal Mini Kit (Qiagen) and quantified by the absorbance of samples at A260nm. Amplification was performed with the Titanium One-Step RT-PCR Kit (Clontech). Thermal cycling was carried out using the GeneAmp PCR system 2400 (Perkin Elmer). The primers used were as follows: for Rac1, 5’-AGTGGTACCCAGAAGTGCGAC-3’ and 5’-TATTGAGCCAACAGACTCACG-3’; for RhoA, 5’-CCGGAGGTGAAACATTTCTG-3’ and 5’-TTTCTGTGACTGTACGTTTTGC-3’; for ODC, 5’-GGGCAAAGGAGCTTAATGTG-3’ and 5’-ATTGGCAGCATCTTCTTCA-3’ as previously described (Cao et. al., 2001).

Western Blots and Pull-Down Assay

Western blots were performed by lysing approximately 20 wild type, standard or morphant embryos that were generated by injecting 73.6ng of sdf-1α MO at the one-cell stage and then cultured to the appropriate stage, in RIPA buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors. Lysates were left on ice for 10 minutes, and then centrifuged for 15 minutes at 14,000rpm at 4°C to remove yolk. Protein concentration was determined using spectroscopic analysis (75 mg/ml). Cleared lysates were combined with an equal volume of 2X reducing buffer and then heated to 95°C. Protein samples were run on a 4–20% gel (Thermo Scientific) and then transferred to a PVDF membrane (Millipore), which was subsequently blocked in 5% PBST/non-fat dry milk for one hour at room temperature, and then incubated with one of the following primary antibodies overnight: 1:1000 RhoA (55) and 1:2000 Rac1 (23A8) purchased from Millipore or 1:2000 Beta tubulin (D-10) purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. This was followed by incubation with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody (Thermo Scientific) used at 1:1,000 for one hour at room temperature. After development with the Super Signal West Femto Chemiluminescence kit (Thermo Scientific), immunoblots were imaged on a Kodak 400R Imaging Station.

For the RhoA and Rac1 pull-down assay, approximately 100 wild type and sdf-1α morphant embryos at stage 20 were used for protein isolation. Lysates were processed as mentioned above to remove yolk proteins. To conduct the pull down assay we used the p21 binding domain (PBD) of the p21-activated protein kinase, which specifically binds to the activated form of Rac1. The PBD was then fused to a glutathione S-transferase (GST) to create a PBD-GST fusion protein (Benard et al. 1999). Similarly, a Rho binding domain (RBD) of the effector of Rhotekin, which specifically binds the activated form of RhoA, was fused to GST to create a GST-RBD fusion protein (Ren et al. 1999). The GST-PBD and GST-RBD fusion proteins were created in the Habas lab (Habas et. al., 2003) and plasmids were sent to us as a gift. The X. laevis whole embryo lysates were incubated for one hour at 4°C with the GST-PBD or GST-RBD fusion proteins, which were previously coupled to glutathione sepharose beads, and the samples were then processed as previously published (Habas and He, 2006).

Key Findings.

Knockdown of sdf-1α and cxcr4 disrupts somite rotation and myotome alignment in X. laevis.

Knockdown of sdf-1α and cxcr4 expression leads to a significant decrease in dystroglycan and laminin expression.

Knockdown of sdf-1α decreases the level of activated RhoA.

Sdf-1α signaling is important for intersomitic boundary formation.

Sdf-1α signaling plays a conserved role in regulating somite rotation in zebrafish and X. laevis, but the mechanism underlying this process is quite distinct.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Annette Chan, Clive Hayzelden, Lisa Galli, Kimberly Tanner, and Clarissa Henry for technical advice and discussions. We thank Raymond Habas for his kind gift of the GST-PBD and GST-RBD reagents as well as his expertise on this subject. We also thank Laura Burrus, Blake Riggs, and Vanja Krneta-Stankic for their thoughtful comments on the manuscript, and Barbara Ustanko for her editorial guidance. The 12/101 antibody developed by J. Brockes, β1-integrin antibody (8C8) developed by P. Hausen, and dystroglycan antibody developed by G.E. Morris, were obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank developed under the auspices of the NICHD and maintained by the Department of Biological Sciences at the University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA 52242. This work was supported by fellowships from the NIH RISE R25-GM059298 to M.A.L and C.N., NIH MARC T34-GM008574 to D.S. and A.S., LaCaixa Fellowship to H.M.V. and an NIH SC3GM081165 grant to C.R.D. The project was also supported by an NIH National Center On Minority Health And Health Disparities award P20MD000544, an NSF MRI 0821204 for the purchase and use of the Ziess LSM 710 confocal microscope, and NSF MRI 0821619 and EAR 0949176 awards for the purchase and use of the Zeiss Ultra 55 Field emission scanning electron microscope.

REFERENCES

- Afonin B, Ho M, Gustin JK, Meloty-Kapella C, Domingo CR. Cell behaviors associated with somite segmentation and rotation in Xenopus laevis. Developmental Dynamics. 2006:3268–3279. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arakawa Y, Bito H, Furuyashiki T, Tsuji T, Takemoto-Kimura S, Kimura K, Nozaki K, Hashimoto N, Narumiya S. Control of axon elongation via an SDF-1alpha/Rho/mDia pathway in cultured cerebellar granule neurons. J Cell Biol. 2003;161(2):381–391. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200210149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartolome R, Galvez B, Longo N, Baleux F, Van Muijen G, Sanchez-Mateos P, Arroyo A, Teixido J. Stromal Cell-Derived Factor-1α promotes melanoma cell invasion across basement membranes involving stimulation of membrane-type 1 matrix metalloproteinase and Rho GTPase activities. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2534–2543. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benard V, Bohl BP, Bokoch GM. Characterization of Rac and Cdc42 activation in chemoattractant-stimulated human neutrophils using a novel assay for active GTPases. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:13198–13204. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.19.13198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun M, Wunderlin M, Spieth K, Knöchel W, Gierschik P, Moepps B. Xenopus laevis Stromal cell-derived factor 1: conservation of structure and function during vertebrate development. J Immuno. 2002;168(5):2340–2347. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.5.2340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Zhao H, Hollemann T, Chen Y, Grunz H. Tissue-specific expression of an Ornithine decarboxylase paralogue, XODC2, in Xenopus laevis. Mech Devel. 2001;102:243–246. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00295-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carretero-Ortega J, Walsh CT, Hernández-García R, Reyes-Cruz G, Brown JH, Vázquez-Prado J. Phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate-dependent Rac exchanger 1 (P-Rex-1), a guanine nucleotide exchange factor for Rac, mediates angiogenic responses to stromal cell-derived factor-1/chemokine stromal cell derived factor-1 (SDF-1/CXCL-12) linked to Rac activation, endothelial cell migration, and in vitro angiogenesis. Mol Pharmacol. 2010;77(3):435–442. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.060400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chockalingam PS, Cholera R, Oak SA, Zheng Y, Jarrett HW, Thomason DB. Dystrophin-glycoprotein complex and Ras and Rho GTPase signaling are altered in muscle atrophy. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2002;283(2):C500–C511. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00529.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danilchick M, Peng HB, Kay BK. Xenopus laevis: Practical uses in cell and molecular biology. Pictorial collage of embryonic stages. Methods Cell Biol. 1991;36:679–681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devoto SH, Melançon E, Eisen JS, Westerfield M. Identification of separate slow and fast muscle precursor cells in vivo, prior to somite formation. Development. 1996a;122:3371–3380. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.11.3371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukui A, Goto T, Kitamoto J, Homma M, Asashima M. SDF-1α regulates mesendodermal cell migration during frog gastrulation. Biochem Biophys Research Communications. 2007;354:472–477. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habas R, Dawid IB, He X. Coactivation of Rac and Rho by Wnt/Frizzled signaling is required for vertebrate gastrulation. Genes and Devel. 2003;17:295–309. doi: 10.1101/gad.1022203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habas R, He X. Activation of Rho and Rac by Wnt/Frizzled Signaling. Methods Enzymol. 2006;406:500–511. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)06038-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton L. The formation of somites in Xenopus. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1969;22:253–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmati-Brivanlou A, Melton DA. Inhibition of activin receptor signaling promotes neuralization in Xenopus. Cell. 1994;77:273–281. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90319-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry CA, McNulty IM, Durst WA, Munchel SE, Amacher SL. Interactions Between Muscle Fibers and Segment Boundaries in Zebrafish. Developmental Biology. 2005;287(2):346–360. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo M, Sirour C, Bello V, Moreau N, Beaudry M, Darribe T. In Vivo Analyzes of Dystroglycan Function During Somitogenesis in Xenopus laevis. Developmental Dynamics. 2009;238:1332–1345. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21814. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollway GE, Bryson-Richardson RJ, Berger S, Cole NJ, Hall TE, Currie PD. Whole-somite rotation generates muscle progenitor cell compartments in the developing zebrafish embryo. Dev Cell. 2007;12(2):207–219. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe AB, Hall A. Rho GTPases: biochemistry and biology. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2005;21:247–269. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.020604.150721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller R, Danilchick M. Regional expression, pattern and timing of convergence and extension during gastrulation of Xenopus laevis. Development. 1988;103:193–209. doi: 10.1242/dev.103.1.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Yamamoto A, Bouwmeester T, Agius E, De Robertis EM. The role of Paraxial Protocadherin in selective adhesion and cell movements of the mesoderm during Xenopus gastrulation. Development. 1998;125:4681–4691. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.23.4681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kintner CR, Brockes JP. Monoclonal antibodies identify blastemal cells derived from dedifferentiating limb regeneration. Nature. 1984;308:67–69. doi: 10.1038/308067a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kragtorp KA, Miller JR. Integrin α5 is required for somite rotation and boundary formation in Xenopus. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:2713–2720. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krneta-Stankic V, Sabillo A, Domingo CR. Temporal and spatial patterning of axial myotome fibers in Xenopus laevis. Dev Dyn. 2010;239:1162–1177. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moepps B, Braun M, Knöpfle K, Dillinger K, Knöchel W, Gierschik P. Characterization of a Xenopus laevis CXC chemokine receptor 4: implications for hematopoietic cell development in the vertebrate embryo. Eur J Immuno. 2000;30:2924–2934. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200010)30:10<2924::AID-IMMU2924>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriyoshi K, Richards LJ, Akazawa C, O’Leary DDM, Nakanishi S. Labeling neural cells using adenoviral gene transfer of membrane-targeted GFP. Neuron. 1996;16:255–260. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwkoop P, Faber J. Normal table of Xenopus laevis development (Daudin) New York and London: Garland Publishing Inc; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ren XD, Kiosses WB, Schwartz MA. Regulation of the small GTP-binding protein Rho by cell adhesion and the cytoskeleton. EMBO J. 1999;18:578–585. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.3.578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirozu M, Nakano T, Inazawa J, Tashiro K, Tada H, Shinohara T, Honjo T. Structure and chromosomal localization of the human stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF1) gene. Genomics. 1995;28:495. doi: 10.1006/geno.1995.1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snow CJ, Henry CA. Dynamic formation of microenvironments at the myotendinous junction correlates with muscle fiber morhogenesis in zebrafish. Gene Expression Patterns. 2009;9:37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.gep.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahinci E, Symes K. Distinct functions of Rho and Rac are required for convergent extension during Xenopus gastrulation. Dev Biol. 2003;259(2):318–335. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00206-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan W, Martin D, Silvio Gutkind J. The Gα13-Rho signaling axis is required for SDF-1-induced migration through CXCR4. Biol Chem. 2006;281(51):39542–39549. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609062200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallingford JB, Ewald AJ, Harland RM, Fraser SE. Calcium signaling during convergent extension in Xenopus. Curr. Biol. 2001;11:652–661. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00201-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wedlich D, Hacke H, Klein G. The distribution of fibronectin and laminin in the somitogenesis of Xenopus laevis. Differentiation. 1989;40:77–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1989.tb00816.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wunnenberg-Stapleton K, Blitz I, Hashimoto C, Cho K. Involvement of the small GTPases XRhoA and XRnd1 in cell adhesion and head formation in early Xenopus development. Development. 1999;126:5339–5351. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.23.5339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youn BW, Malacinski GM. Somitogenesis in the amphibian Xenopus laevis:scanning electron microscopic analysis of intrasomitic cellular arrangements during somite rotation. J Embryo Exp Morphol. 1981;64:23–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]