Abstract

Interpretation of neuropsychological tests may be hampered by confounding sociodemographic factors and by using inappropriate normative data. We investigated these factors in three tests endorsed by the World Health Organization: the Grooved Pegboard Test (GPT), the Children's Color Trails Test (CCTT), and the WHO/UCLA version of the Auditory Verbal Learning Test (AVLT). In a sample of 12-15-year-old, Afrikaans- and English-speaking adolescents from the Cape Town region of South Africa, analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) demonstrated that quality of education was the sociodemographic factor with the biggest influence on test performance, and that age also significantly influenced GPT and CCTT performance. Based on those findings, we provide appropriately stratified normative data for the age group in question. Comparisons between diagnostic interpretations made using foreign normative data versus those using the current local data demonstrate that it is imperative to use appropriately stratified normative data to guard against misinterpreting performance.

Keywords: Neuropsychology, Grooved Pegboard Test, Children's Color Trails Test, WHO/UCLA Auditory Verbal Learning Test, South Africa

In the early 1990s, the World Health Organization (WHO) compiled a battery of preexisting, adapted, or newly-commissioned brief neuropsychological tests deemed suitable for use in cross-cultural contexts (Maj et al. 1991).The Grooved Pegboard Test (GPT; Matthews and Klove 1964), was included under the assumption that it was culture-fair because it did not contain stimuli, items, or tasks likely to disadvantage participants from non-Western cultures (Maj et al. 1993). The Children's Color Trails Test (CCTT; Llorente et al. 2003), which uses colors instead of letters of the alphabet as stimuli, and accommodates visual rather than verbal instructions, was included because of it's applicability to non-English speakers and to individuals with limited education (Llorente et al. 2003; Maj et al. 1991). The WHO/UCLA version of the Auditory Verbal Learning Test (AVLT; (Maj et al. 1993)) was included because the stimuli were selected from a lexicon of 250 words describing globally familiar concepts (Snodgrass and Vanderwart 1980).

Subsequent to the compilation of the WHO test battery, the International Test Commission (ITC) produced guidelines stipulating that good test practice involves not only selecting tests with limited cultural bias and adapting test material where such bias is likely to exist, but also stressed the importance of using normative data adequately characterizing the sociocultural and demographic profile of the individuals being tested to interpret test scores (International Test Commission 2000, 2010).

There are important reasons for adhering to the ITC stipulations in the context of a multicultural, multilingual, and socioeconomically diverse country such as South Africa. First, low and middle income countries (LAMIC) tend to carry a disproportionately high global burden of disease; sub-Saharan Africa, for example, has the highest global incidence of HIV infection (WHO 2010). Second, individual neural and cognitive development is compromised even in neurologically healthy individuals living in LAMICs, likely due to a combination of factors, including poverty, malnutrition, poor medical provision, increased incidence of perinatal complications, high prevalence of infectious diseases, and limited educational opportunities (Bellamy and UNICEF 2004; Olness 2003). Hence, researchers interested in, for instance, neuropsychological impairment associated with diseases such as HIV, or in how much cognitive function might be improved following treatment of those diseases, or in the relative contributions of various biopsychosocial variables to compromised cognition during childhood and adolescence, need instruments appropriate for the populations they intend to study.

For these and other reasons, many studies funded by international agencies are hosted in South Africa (e.g., Ferrett et al. 2010; May et al. 2007; S. L. Williams et al. 2007), which has a relatively unique combination of, on the one hand, a high incidence and prevalence of diseases known to affect neuropsychological functioning, and, on the other hand, a reasonably well-developed research infrastructure. If the quality of such studies is to be maintained and improved, and if the wide variety of South African clinical populations are to continue being studied as part of the broader brain-behavioral science enterprise, then the production of culturally fair normative data for internationally recognizable and standardized neuropsychological tests is crucial.

One of the major challenges to the use of such tests in South Africa (and in similar developing-economy countries) is that their cross-cultural utility varies according to the characteristics of the test populations. Dynamic and diverse historical and cultural factors (e.g., geographical location, degree of urbanization, home language and language of educational instruction, socioeconomic status, access to and quality of education, exposure to test-taking experiences, and cultural relevance of tasks) have an impact on neuropsychological test performance (e.g., Braga 2007; Brickman et al. 2006; I Fortuny et al. 2005; Manly 2008; Ostrosky-Solis et al. 1985). The interpretation of neuropsychological test results is even more complicated than usual in heterogeneous societies such as South Africa, which has 11 national languages, profound socioeconomic and educational disparities, and rapidly changing socialization structures (Foxcroft 1997, 2002; Jinabhai et al. 2004; Rosselli et al. 2009; Wong and Fujii 2004).

For instance, with regard to education, data from South Africa are consistent with those from North America (see, e.g., Manly 2006; Manly et al. 2004; Manly et al. 2002): Performance on neuropsychological tests is affected adversely by poor quality of education, and racial differences in performance on those tests tend to be attenuated by higher levels, and better quality, of education. With specific regard to quality of education, numerous studies have reported significant differences in neuropsychological test performance between South Africans with disadvantaged quality of education and (a) those with advantaged quality of education, and (b) non-local normative samples (Cave and Grieve 2009; Jinabhai et al. 2004; Shuttleworth-Edwards et al. 2004a; Shuttleworth-Jordan 1996; Skuy et al.2000, 2001)

A reasonably large literature demonstrates that, for South African individuals with higher levels of acculturation to Western culture, greater proficiency in English, greater urbanization, and more exposure to better quality of education, performance on neuropsychological tests tends to be compatible with normative data from standardization samples in England and North America (Cave and Grieve 2009; Grieve andvan Eeden 2010; Rushton and Skuy 2000; Rushton et al. 2004; Shuttleworth-Edwards et al. 2004a, 2004b; Shuttleworth-Jordan 1996; Skuy et al. 2002). However, individuals with that set of characteristics constitute only a small sector of South African society; for example, more than 90% of South Africans do not speak English as their first language; about 90% are not white; and more than 40% are not urbanized (Statistics South Africa 2007).

Consequently, a particular problem that hampers research in South Africa (and in sub-Saharan Africa in general) is that test scores on unadapted and culturally biased instruments tend to be uniformly low. In other words, in many cases both healthy individuals and those with neuropsychological dysfunction will attain scores that, relative to non-local normative standards, fall in the range of functioning conventionally interpreted by clinicians as being indicative of impaired functioning. Such lack of variability in scores limits the discriminability of the tests and obscures potentially meaningful between-group differences (Alcock et al. 2008; Ruffieux et al. 2010). Other pitfalls inherent in not using culturally appropriate tests and normative data in the South African context include false positive misdiagnoses as well as false negative misclassifications, based on erroneous assumptions that poor performance is a consequence of, for instance, socioeducational deprivation (Bauer 1997; de Rotrou et al. 2005; Farah 2007; Foxcroft 1997; Lezak et al. 2004; Martin et al. 2001; Mitrushina et al. 2005; Nell 2000; Shuttleworth-Jordan 1997; Strauss et al. 2006; Wong 2006).

With particular regard to the three tests that are the focus of the current research, there is no previous research on African samples. Although Rosin and Levett (1989) demonstrated that South African children performed more poorly than their American counterparts on the Children's Trail Making Test, it is not known whether a similar performance bias exists for the CCTT. On the Rey AVLT, rural Zulu children and urban Black polyglot adolescents both performed poorly relative to US standardization samples (Jinabhai et al. 2004; Skuy et al. 2001), despite the former study replacing potentially culturally unfamiliar items with ones assumed to be more appropriate for local purposes1. Again, however, it is not known whether the modifications introduced by the WHO/UCLA AVLT have reduced this performance bias.

In summary, it is of critical importance for (a) cross-cultural comparative research, (b) clinical purposes, and (c) the advancement of the brain-behavioral sciences, to ascertain, which sociodemographic factors confound interpretation of neuropsychological test performance, to evaluate the suitability of pre-existing foreign normative data, and to collect and publish locally-derived data that are stratified by relevant sociodemographic factors (Nell 2000; Shuttleworth-Jordan 1996, 1997). The heterogeneous South African context provides an ideal milieu in which to pursue such goals. Hence, the aims of this study were to, in a sample of South African adolescents, (1) ascertain which sociodemographic factors influence performance on the Grooved Pegboard Test, the Children's Color Trails Test, and the WHO/UCLA Auditory Verbal Learning Test; (2) create appropriately stratified normative data for the local population; and (3) examine the cross-cultural utility of previously published non-local normative data for the local population.

Methods

Research Design and Participants

We used a cross-sectional design with nonrandomized selection criteria, and convenience recruitment methods. The data reported here are from healthy control participants (N = 215) recruited into a larger multidisciplinary study examining the effects of alcohol abuse on the adolescent brain. The sample size for the GPT data (N = 194) was smaller than that for the other two tests because data for ambidextrous (n = 10) and left-handed (n = 11) participants were excluded from the analyses. Only data from right-handed participants were used so as to avoid the potentially confounding effects of handedness on GPT performance (Bryden and Roy 2005; Mitrushina et al. 2005).

The following exclusion criteria were applied: fewer than 4 years of education at a government school in the greater Cape Town region; more than one school grade repeated; first language other than Afrikaans or English; mental retardation and/or learning disability; severe behavioral abnormalities or social adjustment difficulties within the school setting; speech or language disorders; sensory impairments, including color blindness (except for visual defects in which the use of spectacles enabled 20/20 vision); current or lifetime Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association 2000) Axis I diagnoses, as assessed via administration of the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School Aged Children (6–18 years) Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL; Kaufman et al. 1996); current use of sedative and/or psychotropic medication; signs or history of fetal alcohol syndrome or malnutrition; history of head injury with loss of consciousness exceeding 10 minutes; any disease affecting the central nervous system; psychometric testing within the past 12 months; and any abnormalities detected by the study's MRI and EEG recordings.

Seventeen potential participants were excluded from the study based on previous psychiatric diagnoses (n = 9) or cannabis use exceeding a lifetime dosage of 10 units (n = 8).

The sample featured coloured (mixed ancestry) and white, Afrikaans- and English-speaking adolescents, aged between 12 and 15 years, with between 6 and 10 years of completed education. All participants were recruited from schools in the greater Cape Town metropolitan region. Table 1 presents the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics for Sociodemographic Variables.

| CCTT and WHO/UCLA AVLT (N = 215) |

GPT (N = 194) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Continuous Variablesa | ||

| Age | 13.91 (1.23) | 13.85 (1.23) |

| Level of education | 6.96 (1.27) | 6.91 (1.28) |

| Categorical Variablesb | ||

| Sex | ||

| Female | 54.4 | 55.7 |

| Male | 45.6 | 44.3 |

| Race | ||

| Coloured | 68.8 | 68.6 |

| White | 31.2 | 31.4 |

| Language | ||

| Afrikaans | 43.3 | 42.3 |

| English | 56.7 | 57.7 |

| Quality of education | ||

| Advantaged | 43.7 | 43.3 |

| Disadvantaged | 56.3 | 56.7 |

Note. CCTT = Children's Color Trails Test; AVLT = Auditory Verbal Learning Test; GPT = Grooved Pegboard Test.

Means are reported with standard deviations in parentheses.

Values reported are percentages.

With regard to age and level of education, the average values for the participants in the entire sample were not statistically significantly different from those for the GPT subset, t = 0.67, p = .502, and t = 0.56, p = .578, respectively. There were no statistically significant differences with regard to the distribution of males and females within the entire sample, χ2(1) = 1.70, p = .195, or within the GPT subset, χ2(1) = 2.50, p = .114. There were also no statistically significant differences in the distribution of participants with advantaged or disadvantaged quality of education within the entire sample, χ2(1) = 3.39, p = .066, or within the GPT subset, χ2(1) = 3.49, p = .062.

With regard to race, in keeping with the descriptive nomenclature for racial groups used in the South African census publications (Statistics South Africa 2007), we refer to the two racial groups represented by participants in this study as white and coloured (i.e., of mixed racial origin). All participants self-identified as either coloured or white (rather than black, Asian, or other). The racial composition of the sample was uneven, with significantly more coloured than white participants within the entire sample, χ2(1) = 30.52, p< .001, and within the GPT subset, χ2(1) = 26.72, p <.001. There was a similar unevenness with regard to language, with significantly more Afrikaans- than English-speaking participants in the entire sample, χ2(1) = 3.91, p = .048, and within the GPT subset, χ2(1) = 4.64, p = .031. However, the distribution of racial and language characteristics in the sample was similar to those distributions in the Western Cape Province, where coloured individuals (50%) outnumber white individuals (20%), and where Afrikaans-speakers (55%) outnumber English-speakers (20%; Statistics South Africa 2007).

We operationally defined quality of education as a dichotomous variable, with two assumed levels (advantaged or disadvantaged) of public (government) schooling (i.e., no participants from private schools were included in the study). The two groups were defined according to the parliamentary classification given to segregated schools prior to democratization in 1994 (Western Cape Education Department 2010). Apartheid regime education policies dictated that schools were segregated, classified, and allocated resources according to race. Hence, advantaged schools were those that, under the apartheid regime, were accessible only to white children. Disadvantaged schools were those that had been allocated to coloured children during the apartheid era.

Under apartheid, the schools we refer to here as ‘disadvantaged’ were allocated fewer human, instrumental, and financial resources than those we refer to here as ‘advantaged.’ For instance, schools attended by coloured and black students were allocated 43% and 4%, respectively, of the funds allocated to schools attended by white students (Corke 1984). Even now, 15 years after South Africa's new political dispensation, the typical disadvantaged school (in comparison with the typical advantaged school) might be described as follows: (a) geographic location within poorer areas with lower levels of personal safety (due to higher levels of interpersonal crime, gangsterism, drug abuse, and vandalism); (b) allocation of fewer human resources, leading to higher learner-educator ratios, higher levels of classroom overcrowding, lower-qualified and -salaried staff, poorer proficiency of educators in language of instruction, and higher absenteeism rates for educators and learners; (c) allocation of fewer material resources (e.g., fewer books, computers, and teacher aids; poorly equipped libraries and science laboratories); (d) fewer extracurricular resources due to the presence of fewer facilities and less manpower for extramural activities and extension subjects (e.g., arts, additional languages, computer studies); and (e) poorer educational outcomes (as measured by earlier school drop-out rates, lower pass rates at Grade 7 and Grade 12 levels, and lower university admission rates).

We recruited participants from 47 government schools in the greater Cape Town urban region of the Western Cape Province of South Africa (19 advantaged and 28 disadvantaged). All participants had received between 5 and 10 years of education within one of those two education profiles. The group with advantaged quality of education included both coloured (n = 27) and white (n = 67) participants, whereas the group with disadvantaged quality of education only included coloured participants.

Measures

Grooved Pegboard Test

Following contemporary practice (e.g., Heaton et al. 1986; Ruff and Parker 1993), only one trial for each hand was administered, starting with the dominant hand. Peg insertion order was from left to right for each row for the right hand, and from right to left for the left hand. Timing began when the examiner gave the cue for the participant to begin, and ended immediately after the participant completely inserted the final peg. The examiner did not interrupt timing if the participant dropped a peg. For both dominant and nondominant hands, the completion time (measured in seconds) for inserting all pegs constituted the primary outcome variable. These scores were not prorated, and did not include in any way the number of drops.

Children's Color Trails Test

We used version K of this test, in accordance with the instructions published in the manual (Llorente et al. 2003). For both Trial 1 and Trial 2, the completion time, measured in seconds, constituted the primary outcome variable. Trial 1 measures perceptual tracking, simple sustained attention, and graphomotor skills. Trial 2 measures the same skills as Trial 1, and also measures complex (divided) attention, sequencing skills, and response inhibition.

Auditory Verbal Learning Test

We used the WHO/UCLA word lists along with the recognition items published in Strauss et al. (2006, p. 783)2. An Afrikaans linguistic specialist evaluated the lists to ascertain whether the words were suitable for local use; specifically, she sought to confirm that the words were familiar to the population, semantically unambiguous, and equivalent between the two languages (in word class, meaning, conceptual difficulty, syllable length, and frequency of colloquial use). This linguistic evaluation confirmed that all the words in list A were entirely suitable for local use and equivalent in Afrikaans and English. However, three List B (distractor list) words were identified as problematic, and were therefore replaced3.

We used the standard administration format, which consists of five free recall trials of List A, an interference trial using List B, two post-interference trials testing free recall of List A (the first immediately after the distractor list, and the second after a 30-minute delay), and a List A recognition trial (Lezak et al. 2004; Mitrushina et al. 2005; Strauss et al. 2006). We used the instructions described by Strauss et al. (2006, p. 784, Fig. 10-29) verbatim for all trials, except for the recognition trial. The latter trial was presented orally, with participants answering yes or no to indicate whether they thought the word being presented was from the original list.

Although numerous outcome measures can be derived from such conventional administration of the AVLT, here we report on, and provide normative data for, only Trial 1, Trial 5, the Immediate and Delayed Recall trials, and the Recognition trial, as these outcome measures tend to be used frequently when assessing verbal memory performance (Strauss et al. 2006).

Procedure

The study protocol and procedures were approved by Stellenbosch University's Committee for Human Research, and they were conducted in strict adherence to the guidelines contained in the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association 2008).

Recruitment procedures involved oral presentations at schools and advertisement via word-of-mouth. Volunteers were screened for eligibility after written informed assent/consent was obtained from them and their parents/guardians. The screening procedure included a psychiatric and medical examination and history-taking interview, conducted by a psychiatrist. Parents and educators corroborated self-reported information.

All neuropsychological test materials were translated according to Brislin's (1983) guidelines, which include translation, independent back-translation, and the resolution of differences between the original and translated versions (Mitrushina et al. 2005). We used this formal translation process to reduce the potential for distortions of meaning resulting from inexact translations and idiosyncratic linguistic variations. Neuropsychological tests were individually administered, following ITC recommendations (International Test Commission 2000), in the participants' home language, by a clinical psychologist, in a quiet testing location with adequate lighting and ventilation.

Statistical Analyses

We completed all analyses using PASW Statistics, version 18.0, and set the threshold for statistical significance at .05.

Preliminary analyses

All data upheld the assumptions underlying parametric inferential analyses. We calculated descriptive statistics for all independent variables (viz., age, sex, race, language, level of education, and quality of education) and for all dependent variables (viz., each of the outcome scores on the GPT, CCTT, and AVLT). To prevent potential confounding effects of age and level of education, which were strongly positively correlated (rs = 0.90, p< .001), we used age as a covariate in the analyses and reported successfully completed years of education for descriptive purposes only.

Analyses of covariance

We conducted a series of ANCOVAs and appropriate post-hoc analyses to ascertain the relative contribution of each independent variable to performance on each outcome variable. For each ANCOVA, we entered age (a continuous variable) as a covariate, and sex, language, and quality of education (all dichotomous variables) as independent variables.

Analyses of variance: Race and neuropsychological test performance

We conducted a series of ANOVAs to ascertain whether, within the group of participants with advantaged quality of education, there were performance differences between coloured and white participants. There were only coloured participants in the group of participants with disadvantaged quality of education, and so this analytic step was not necessary for that education group.

Stratification of normative data

The analyses described above, then, contributed to our decisions about how to stratify the normative data appropriately. Another set of analyses also contributed to those decisions: For outcome measures affected significantly by age, we undertook further investigations to ascertain how to subdivide the age groups when presenting normative data. For these analyses (ANOVAs and post-hoc pairwise comparisons via the Least Significant Difference procedure), we treated age as a categorical variable, with four discrete groups: (a) 12-year-olds (12.0 to 12.11 years); (b) 13-year-olds (13.0 to 13.11 years); (c) 14-year-olds (14.0 to 14.11 years); and (d) 15-year-olds (15.0 to 15.11 years).

Comparisons between local and non-local normative data

To facilitate these comparisons, we first converted the raw score data into two sets of z-scores (a ‘local’ set and a ‘foreign’ set). To transform each participant's raw score on each outcome variable into a local z-score, we used the appropriate means and standard deviations derived from the current dataset. To transform each participant's raw score on each outcome variable into a foreign z-score, we used means and standard deviations from three separate sets of normative data from non-local sources. Specifically, for the GPT we used the age-stratified miscellaneous normative data from North America, as published in the instrument's instruction leaflet (Lafayette Instrument Company 2003); for the CCTT we used the smoothed, age-stratified American standardization data published in Llorente et al.'s (2003) manual; and for the WHO/UCLA AVLT we used Ponton et al.'s (1996) data for Hispanic-American 16- to 29-year-olds, in the absence of published data that precisely matched the age-range of our sample.

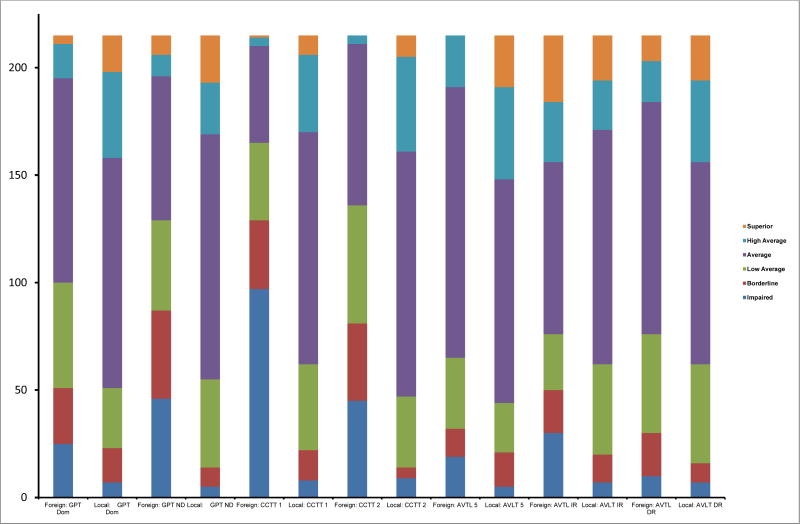

We then created a stacked histogram of those z-score data to demonstrate, graphically, the number of participants that would fall into discrete performance ranges (e.g., low average, average, high average) when using local norms versus when using foreign norms.

Results

Grooved Pegboard Test

The ANCOVAs here detected statistically significant main effects of age and quality of education for both outcome variables (i.e., completion times for both dominant and nondominant hands; see Table 2). The means suggest that older age and an advantaged education were associated with faster completion times. There were no main effects of sex or language, and no interactions.

Table 2. Grooved Pegboard Test ANCOVA: Effects of Sociodemographic Variables on Performance.

| Dominant Hand | Nondominant Hand | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| p | ω2 | p | ω2 | |

| Main effect | ||||

| Age | < .001*** | .084 | < .001*** | .072 |

| Sex | .137 | .011 | .527 | .002 |

| Language | .606 | .001 | .262 | .006 |

| Quality of Education | .007** | .035 | < .001*** | .061 |

| Interaction effect | ||||

| Sex x Language | .669 | .001 | .189 | .008 |

| Sex x Quality of Education | .574 | .002 | .412 | .003 |

| Language x Quality of Education | .925 | < .001 | .099 | .013 |

| Sex x Language x Quality of Education | .418 | .003 | .539 | .002 |

p< .05.

p< .01.

p< .001.

No between-race differences were seen in the group of participants with advantaged quality of education (F(1, 81) = 0.03, p = .872 for the dominant hand, and F(1, 81) = 0.63, p = .431 for the nondominant hand).

In light of the statistically significant main effect of age detected by the ANCOVAs, we conducted ANOVAs and pairwise post-hoc comparisons to determine how best to stratify the normative data by age group. This suggested a stepwise improvement in GPT performance in (a) dominant- and nondominant-hand performance for 12-year-olds compared to 14- and 15-year-olds (ps<. 01); (b) dominant- and nondominant-hand performance for 13-year-olds compared to 15-year-olds (ps< .05); and (c) nondominant-hand performance for 13-year-olds compared to 14-year-olds (p< .001). Consequently, we stratified the normative data by two age bands (i.e., 12- and 13-year-olds separate from 14- and 15-year-olds) and by quality of education. These normative data are presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Grooved Pegboard Test: Descriptive Normative Data for 12-15-year-old South African Children, Stratified by Age and Quality of Education.

| Dominant Hand | Nondominant Hand | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Age / Quality of Education | n | M | SD | Range | n | M | SD | Range |

| 12-13 years | ||||||||

| Advantaged | 54 | 71.07 | 8.21 | 58-96 | 54 | 78.59 | 10.59 | 56-103 |

| Disadvantaged | 47 | 74.49 | 13.35 | 50-120 | 47 | 84.49 | 10.31 | 65-102 |

| 14-15 years | ||||||||

| Advantaged | 30 | 67.47 | 8.77 | 49-81 | 30 | 72.93 | 10.61 | 51-88 |

| Disadvantaged | 63 | 69.27 | 8.32 | 53-94 | 63 | 76.24 | 13.93 | 22-113 |

Note. Values presented are in seconds, representing time to complete the task. The sample (N = 194) includedfemale and male, Afrikaans- and English-speaking participants. Groups with advantaged quality of education included coloured and white participants; groups with disadvantaged quality of education included coloured participants only.

Children's Color Trails Test

The ANCOVAs here detected statistically significant main effects of age and quality of education for both outcome variables (i.e., completion times on Trial 1 and Trial 2; see Table 4). The means suggest that older age and advantaged quality of education were associated with faster completion times. There were no statistically significant main effects of sex or language, and no statistically significant interaction effects.

Table 4. Children's Color Trails Test ANCOVA: Effects of Sociodemographic Variables on Performance.

| Trial 1 | Trial 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| p | ω2 | p | ω2 | |

| Main effect | ||||

| Age | < .001*** | .117 | < .001*** | .068 |

| Sex | .112 | .012 | .842 | .001 |

| Language | .380 | .004 | .187 | .008 |

| Quality of Education | .019* | .026 | < .001*** | .077 |

| Interaction effect | ||||

| Sex x Language | .101 | .013 | .626 | .001 |

| Sex x Quality of Education | .423 | .003 | .256 | .006 |

| Language x Quality of Education | .573 | .002 | .783 | .001 |

| Sex x Language x Quality of Education | .858 | .001 | .421 | .003 |

p< .05.

p< .01.

p< .001.

No between-race differences were seen in participants with advantaged quality of education (F(1, 91) = 0.22, p = .644 for Trial 1, and F(1, 91) = 1.39, p = .242 for Trial 2).

In light of the statistically significant main effect of age detected by ANCOVAs, we again conducted ANOVAs and pairwise post-hoc comparisons to determine how to best stratify the normative data by age group. These analyses detected (a) statistically significant differences in performance on both CCTT trials between 12-year-olds and each of the other three age groups (ps< .05), but (b) no statistically significant performance differences between 13-year-olds compared to 14- and 15-year-olds (ps> .05), or between 14-year-olds compared to 15-year-olds (ps> .05). Consequently, we stratified the normative data by two age bands (i.e., 12-year-olds separate from 13-15-year-olds) and by quality of education. These normative data are presented in Table 5.

Table 5. Children's Color Trails Test: Descriptive Normative Data for 12-15-year-old South African Children, Stratified by Age and Quality of Education.

| Age / Quality of Education | Trial 1 | Trial 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| n | M | SD | Range | n | M | SD | Range | |

| 12 years | ||||||||

| Advantaged | 31 | 26.77 | 7.35 | 16-45 | 31 | 43.48 | 9.20 | 27-65 |

| Disadvantaged | 34 | 32.82 | 9.22 | 17-53 | 34 | 55.59 | 14.77 | 32-100 |

| 13-15 years | ||||||||

| Advantaged | 63 | 22.13 | 7.44 | 8-48 | 63 | 37.92 | 10.82 | 19-75 |

| Disadvantaged | 87 | 22.67 | 8.99 | 10-59 | 87 | 46.53 | 13.94 | 21-98 |

Note. Values presented are in seconds, representing time to complete the task. The sample (N = 215) included female and male, Afrikaans- and English-speaking participants; groups with advantaged quality of education included coloured and white participants; groups with disadvantaged quality of education included coloured participants only.

WHO/UCLA Auditory Verbal Learning Test

Of the five AVLT outcome variables older age was associated with better performance for two measures, and better quality of education for three (see Table 6). There were no main effects of sex and language, or interactions.

Table 6. WHO/UCLA Auditory Verbal Learning Test ANCOVA: Effects of Sociodemographic Variables on Performance.

| Trial 1 | Trial 5 | Immediate Recall | Delayed Recall | Recognition | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| p | ω2 | p | ω2 | p | ω2 | p | ω2 | p | ω2 | |

| Main effect | ||||||||||

| Age | .105 | .013 | .014* | .029 | .241 | .007 | .020* | .026 | .737 | .001 |

| Sex | .954 | .000 | .990 | < .001 | .638 | .001 | .682 | .001 | .772 | .000 |

| Language | .761 | .000 | .265 | .006 | .195 | .008 | .629 | .001 | .170 | .009 |

| Quality of Education | .187 | .008 | .003** | .042 | .023* | .025 | .019* | .027 | .131 | .011 |

| Interaction effect | ||||||||||

| Sex x Language | .728 | .001 | .757 | .000 | .790 | < .001 | .109 | .012 | .897 | .000 |

| Sex x Quality of Education | .743 | .001 | .136 | .011 | .069 | .016 | .145 | .010 | .792 | .000 |

| Language x Quality of Education | .830 | .000 | .826 | < .001 | .860 | < .001 | .838 | <.001 | .088 | .014 |

| Sex x Language x Quality of Education | .597 | .001 | .776 | < .001 | .984 | < .001 | .567 | .002 | .193 | .008 |

p< .05.

p< .01.

p< .001.

No between-race differences were seen in participants with advantaged quality of education (F(1, 91) = 1.30, p = .257 for Trial 1; F(1, 91) < 0.01, p = .949 for Trial 5; F(1, 91) = 2.61, p = .110 for Immediate Recall; F(1, 91) = 2.45, p = .120 for Delayed Recall; and F(1, 91) = 3.24, p = .075 for Recognition).

Although the ANCOVAs showed statistically significant main effects of age on Trial 5 and Delayed Recall performance, ANOVAs and post-hoc pairwise comparisons did not detect any statistically significant age-related differences, implying the absence of a linear age-related performance trend. In addition, the effect sizes associated with these age-related comparisons were small (Hedge's g values ranged from 0.03 to 0.18), and so normative data for the entire age range (12-15-year olds) were stratified only by quality of education (see Table 7).

Table 7. WHO/UCLA Auditory Verbal Learning Test: Descriptive Normative Data for 12-15-year-old South African Children, Stratified by Quality of Education.

| Trial 1 | Trial 5 | Immediate Recall | Delayed Recall | Recognition | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Quality of education | M | SD | Range | M | SD | Range | M | SD | Range | M | SD | Range | M | SD | Range |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Advantaged | 7.07 | 1.80 | 3-12 | 12.95 | 1.54 | 8-15 | 11.77 | 1.95 | 6-15 | 11.50 | 2.12 | 5-15 | 29.20 | 1.34 | 20-30 |

| Disadvantaged | 6.71 | 1.82 | 2-12 | 11.91 | 1.97 | 7-15 | 10.70 | 2.31 | 5-15 | 10.64 | 2.25 | 4-15 | 28.79 | 1.42 | 25-30 |

Note.Values presented are raw scores (i.e., number of words recalled on the trial for Trials 1, 5, Immediate and Delayed Recall; and number of Recognition items answered correctly). The sample (N = 215) included female and male, Afrikaans- and English-speaking participants; the group with advantaged quality of education (n = 94) included coloured and white participants; the group with disadvantaged quality of education (n = 121) included coloured participants only.

Comparisons between Local and Non-local Normative Data

For each participant, we derived two z-scores (one local, based on the normative data in Tables 3, 5, and 7, and one foreign, based on the sources listed earlier), and then categorized each z-score using conventional diagnostic/interpretive taxonomy as presented by, for instance, Mitrushina et al. (2005): impaired (z < -2.00); borderline (z ≥ -2.00 and ≤ -1.34); low average (z ≥ -1.33 and ≤ -0.68); average (z ≥ -0.67 and ≤ 0.67); high average (z ≥ 0.68 and ≤ 1.33); and superior (z > 1.33). For all outcome measures, the number of participants categorized as ‘impaired’ is much larger when using the z-scores derived from foreign normative data than when using those derived from local data (see Figure 1). These differences are notably large for CCTT Trial 1: almost half the sample (f = 97) would be classified as ‘impaired’ on this measure using Llorente et al.'s (2003) American standardization normative data, whereas only 8 participants would be classified thus using appropriately stratified local normative data.

Fig. 1. Interpretive ranges using foreign and local normative data.

GPT = Grooved Pegboard Test; Dom = dominant hand; ND = nondominant hand; CCTT = Children's Color Trails Test; AVLT = WHO/UCLA Auditory Verbal Learning Test; IR = Immediate Recall; DR = Delayed Recall.

Also of interest here is the fact that the number of performances classified as being at or above the average range would be much smaller when using foreign norms than when using local norms. For example, when using the Lafayette's (2003) data to interpret GPT nondominant hand completion times, 160 participants would achieve ‘average’, ‘high average’, or ‘superior’ performance using local norms, whereas only 86 would do so using foreign norms.

Finally, the differences in interpretive classifications between local and foreign normative data for the AVLT were smaller than for the other two tests. For example, on the Delayed Recall trial, 10 participants were classified as ‘impaired’ using Ponton et al.'s (1996) norms for Hispanic individuals in the United States, whereas 7 participants were classified thus using local norms.

Discussion

The aims of this study were, in a sample of Afrikaans- and English-speaking, coloured and white, urbanized adolescents from the Western Cape province of South Africa, (a) to identify which sociodemographic variables were most strongly associated with performance on three tests from the neuropsychological battery compiled by the WHO for use in cross-cultural research (the Grooved Pegboard Test, the Children's Color Trails Test, and the WHO/UCLA Auditory Verbal Learning Test; Maj et al. 1991); (b) to create appropriately stratified local normative data, and (c) to evaluate the suitability of previously-published non-local normative data.

Influence of Sociodemographic Variables on Test Performance

Our data indicated that, for all three tests, older age and advantaged education were associated with better performance. Sex, language, and race did not contribute significantly to the variance in performance on any of the outcome measures.

The findings of improved cognitive performance with increasing age are consistent with general trends in the literature (Giedd et al. 2008; Gogtay et al. 2004; Luna 2009; Shaw et al. 2006; Sowell et al. 2004; Yurgelun-Todd 2007). Our data suggest, however, that cognitive functioning continues to undergo refinements and becomes more efficient during the adolescent phase. For instance, previous studies have reported that GPT completion times decrease gradually throughout childhood, and then tend to stabilize during adolescence (Rosselli et al. 2001; Trites 1977). Our findings suggest ongoing refinement during adolescence, with 14- and 15-year-olds performing more efficiently than 12- and 13-year-olds. Similarly, previous normative studies reported stability of CCTT performance between the ages of 12 and 16 (Llorente et al. 2003; J. Williams et al. 1995), whereas in the current study this stability only appeared to occur after age 12. The poorer performance by 12-year-olds compared to older children in this study may be indicative of developmentally-related limitations in those younger individuals' capacity for cognitive control, an observation consistent with those made in other studies (Anderson 2002; Luna 2009).

Although the influence of age on adolescent WHO/UCLA AVLT performance has not been studied previously, our data revealed similar trends to those reported for other versions of the Auditory Verbal Learning Test demonstrating similar performances within 11-17 year-olds (Vakil et al. 1998).

Our findings of improved cognitive performance with increasing quality of education are also consistent with general trends in the literature. The discrepancies in performance, on all outcome measures, between participants with advantaged and disadvantaged quality of education correspond with findings in previous literature from North America (e.g., Manly 2006; Manly et al. 2004; Manly and Echemendia 2007; Manly et al. 2002) and from South Africa (e.g., Cave and Grieve 2009; Grieve and van Eeden 2010; Shuttleworth-Edwards et al. 2004b). The current data reinforce, quite powerfully, the need for separately stratified normative data for participants with differing quality of education.

Ongoing differences in neuropsychological performance between South African individuals with differing qualities of education have been attributed to inequities originating from the apartheid era (van der Berg 2002; van der Berg and Burger 2003). Since 1994 and the country's new political dispensation, there has been a marked reduction of between-race quantitative educational attainment differentials (i.e., number of years of education has begun to even out across racial groups); nonetheless, qualitative discrepancies between schools remain large (van der Berg 2011). The cumulative effects of inferior quality of education seem to have persisted in the context of ongoing socioeconomic deprivation and disparities (Burman and Reynolds 1986; Kahn 2004; Molteno 1985; Motala 2006; O'Gorman 2007; Sonn and Collett 2010). Collectively, the abovementioned factors contribute to large performance differences on neuropsychological tests by participants with differing sociodemographic profiles (Foxcroft 2002, 2004; Foxcroft and Roodt 2005; Jinabhai et al. 2004; Nell 2000).

Our findings with regard to the absence of sex differences in performance on the three tests are also largely consistent with previous literature. For instance, Bryden and Roy's (2005) isolated findings of a modest female advantage on the GPT stand in contrast to most of other studies of that test (see, e.g., Rosselli et al. 2001; Thompson et al. 1987). Similarly, most studies of trail-making tests have not demonstrated sex differences in performance (Lezak et al. 2004; Strauss et al. 2006); Llorente et al.'s (2003) finding of a male advantage on CCTT Trial 1 and Williams et al.'s (1995) finding of a female advantage on CCTT Trial 2 have not been replicated. Similarly, the overall trend in the child and adolescent AVLT literature does not generally demonstrate sex differences in performance (Lezak et al. 2004; Strauss et al. 2006).

Our findings with regard to the absence of language-based differences in performance on the CCTT and on the WHO/UCLA AVLT are consistent with the report of Maj et al. (1993), who tested adult English-, Thai-, Lingala-, Italian-, and German-speakers and found no between-group differences. The current data with regard to CCTT and language stand in contrast, however, to those presented by Mok and colleagues (2008). Those researchers demonstrated, in a sample of children from Hong Kong, that Mandarin speakers completed both CCTT trials faster than both Mandarin-English bilinguals and English monolinguals. It is possible that lexigrammatic differences between English and Mandarin written language may partially explain the differences demonstrated within the Hong Kong sample. If that is the case, we would not expect these differences to exist in the current sample, because Afrikaans and English employ the same system of lexigrams.

Cross-lingual comparisons of polylingual samples on the WHO/UCLA AVLT have not been investigated previously.

Contemporary research on race-based differences in neuropsychological functioning rarely treat race or ethnicity as an isolated factor; the effects of factors such as socioeconomic status, acculturation to mainstream or dominant culture, and level and quality of education are always considered as well (e.g., Manly 2005; Manly et al. 2004; Manly and Echemendia 2007; Touradj et al. 2001). Consequently, race-based performance differences per se on the GPT, CCTT, and AVLT have not been reported previously.

Race-based performance differences on the GPT and the CCTT have not been investigated previously in South Africa, but South African neuropsychological research in general has established that black South African adolescents tend to perform poorly relative to American normative data (e.g., Jinabhai et al., 2004; Skuy et al., 2001) and that differences in performance between black, white, and coloured participants tend to be attenuated, but not entirely eliminated, by better quality of education, degree of urbanization and acculturation, and greater exposure to, and proficiency in, English (e.g., Shuttleworth-Edwards et al. 2004b; Shuttleworth-Jordan 1996). Our findings of the absence of race-based performance differences between coloured and white participants with advantaged quality of education on the GPT, CCTT, and WHO/UCLA AVLT are, therefore, roughly in keeping with the aforementioned trends.

Comparisons of Local versus Foreign Normative Data

Given the data derived from the analyses of sociodemographic influences on test performance, normative data were stratified by age group (differently for each test, depending on analytic indications) and by quality of education (at two levels, advantaged or disadvantaged). As shown in the tables of normative data (Tables 3, 5, and 7), our findings are consistent with previous literature indicating that GPT completion times for the dominant hand are faster than those for the nondominant hand, and that CCTT Trial 1 completion times are faster than those for Trial 2, probably due to the relative complexity of the former task (Lezak et al. 2004; Llorente et al. 2003; J. Williams et al. 1995).

Regarding the local normative data for the WHO/UCLA AVLT, performance was highly consistent with trends noted in standard neuropsychological texts (Lezak et al. 2004; Mitrushina et al. 2005) based on overviews of multiple studies on various Auditory Verbal Learning Tests. For instance, previous studies suggest that (a) Trial 5 acquisition scores usually range from 12 to 13 (in the current study, we found mean values of 12.95 ± 1.54 for participants with advantaged quality of education, and 11.91 ± 1.97 for those with disadvantaged quality of education), (b) scores on immediate and delayed recall trials tend to be similar, rarely differing by more than 2 points (in the current study, we found mean differences of 0.27 ± 0.17 for participants with advantaged quality of education, and 0.06 ± 0.05 for those with disadvantaged quality of education).

As Figure 1 showed, the three tests varied with regard to the extent to which previously published normative data, derived from non-local populations, were biased against the local participants, particularly those with disadvantaged quality of education. Of particular interest here was the fact that foreign normative data for nonverbal tests which were devoid of obviously culturally loaded stimulus items or test material (the GPT and the CCTT) appeared to be more biased against the local population than were foreign normative data for the verbal test (the AVLT).

Regarding the GPT, the normative data published by the instrument's developers, the Lafayette Instrument Company (2003) are particularly unsuitable for South African adolescents, and increase the risk of false positive diagnoses of impaired fine motor coordination: the mean completion times, for both dominant and nondominant hands, presented by those foreign datasets are significantly shorter than the mean completion times contained in the local dataset presented by the current study.

Regarding the CCTT, our findings demonstrated that Llorente et al.'s (2003) USA standardization normative data are inappropriate for use in the local population. Across all age groups, and for participants with advantaged and disadvantaged quality of education, completion times on both CCTT trials were substantially slower than those presented by Llorente et al. The mean completion times for both trials, for all except one subgroup of the current sample (viz., 15-year-old participants with advantaged quality of education) were slower than the mean performance for adolescents with ADHD and mild head injuries in the abnormative data published by Llorente et al. (2003). That fact demonstrates emphatically that the use of such foreign norms for this particular test is likely to increase the risk of false-positive diagnoses of dysfunctional abilities in the domains of visual attention, attentional control, and cognitive flexibility.

Our findings that foreign normative data for the GPT and the CCTT were biased against local participants is consistent with previously published data showing that nonverbal tests are not necessarily free from cross-cultural bias (Rosselli and Ardila 2003; Shuttleworth-Edwards et al. 2004b). Furthermore, the overall pattern of slower performance by South Africans than by US standardization samples is not uncommon (Nell 2000). These differences in performance on speeded tests between individuals from developing- and developed-economy countries may reflect cultural differences regarding the relative importance of accuracy versus speed (Grieve 2005). The emphasis on speed, for example, is not considered to be important in all cultures (Brickman et al. 2006; Foxcroft 2002). Ardila (2005) points out that in many cultures, speed and quality may be at cross-purposes; some cultures, for instance, may regard good products as those resulting from slow and careful planning processes, whereas others may hold rapid execution as a primary goal. Nell (2000) hypothesizes that observed differences between some South Africans and North Americans on speeded tests is partially because the latter population attach greater value to speed, and consequently have greater exposure to tests constrained by speed limits, from primary school onwards. The especially slow performances by participants with disadvantaged education may also reflect diminished opportunities to develop test-taking skills within under-resourced education systems (Foxcroft 2004; Kanjee 2005).

In striking contrast to the comparisons of foreign versus local normative data for the nonverbal tests, similar comparisons for the verbal test (WHO/UCLA AVLT) suggested that Ponton et al.'s (1996) normative data for Hispanic Americans could have useful local applications, despite the participants in that US sample being older (16-29 years) than those in the current sample. The relative culture-fairness of the WHO/UCLA AVLT has important implications for testing verbal memory in South Africa, because other list-learning tests (e.g., the Rey AVLT) appear to be strongly biased against South Africans (Jinabhai et al. 2004; Skuy et al. 2001).

Finally, Figure 1 showed large differences between foreign- and local-based interpretations in terms of the ranges of scores within the various interpretive categories, particularly with regard to GPT and CCTT performance. The disproportionately large number of scores classified as ‘impaired’, and the disproportionately small number of scores categorized at or above ‘average’, when using foreign normative data means that (a) clinicians using those data are increasing their risk of making false positive misdiagnoses of impaired functioning, and (b) the capacity of the tests to identify above-average or superior functioning is reduced.

Limitations of the Current Study

Although one of the strengths of this study is the collation of carefully stratified normative data, it cannot be assumed that these data are generalizable to other groups in the Western Cape (e.g., Xhosa-speaking individuals, or black African adolescents in general) or to other cultural subgroups in other regions of South Africa.

Another limitation of the current study is that could not address the question of whether the ongoing improvements, beyond age 12, in GPT and CCTT performance are peculiar to the study population. Future studies that directly compare performances across cultural contexts might be able to address this question, and to investigate, for instance, whether adolescents from developing-economy countries simply show a slower trajectory of improvement on tests of information processing speed.

The current study is also limited by the fact that the comparisons of normative data were not based on contemporaneous sampling, but were derived from different sources. It would be helpful to conduct studies using the identical protocols and procedures, during the same time frame, across different geographical locations, thus enabling more direct cross-cultural comparisons of the kind accomplished by Maj et al (1993).

Summary and Recommendations

No differences in performance on any of neuropsychological variables were seen between females and males, between Afrikaans- and English-speakers, or between coloured and white participants, with advantaged quality of education. However, age and quality of education influenced GPT and CCTT performance, and influenced performance on three out of five AVLT outcome measures. Better performance was associated with older age and better quality of education.

We stratified our normative data for the three tests by age and by quality of education, and we recommend that the GPT and the CCTT are culture-fair only in conjunction with the use of local normative data stratified in such a fashion. Furthermore, although we strongly advocate the use of properly-stratified local normative data in general (they are more likely than foreign norms to characterize cognitive functioning accurately), the WHO/UCLA AVLT, used in conjunction with Ponton et al.'s (1996) normative data, appears to be culturally fair for use in the current study population.

Our study, and our approach, is consistent with the ITC's recommendations regarding good test practice, in that it gives due attention to the selection and adaptation of test material in order to reduce cultural bias, and the creation of appropriate normative data within which to interpret test results fairly (International Test Commission 2000, 2010). We hope that future studies will use the design template provided by this study to extend the normative database to, for example, individuals younger than 12 and older than 15 years in South Africa, and to residents of other LAMIC countries.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH Grant Number 5RO1AA016303-04). The authors do not have any conflicts of interest that might be interpreted as influencing the research.

Footnotes

For instance, chicken replaced turkey, and herdboy replaced ranger.

But note the typographical error for the 5th item of list A, which should read plane, not place

These three problematic items were: (1) boot/stewel- the Afrikaans word is used rarely (and only in more formal language contexts), and so the semantically compatible words shoe/skoen weresubstituted; (2) plate/bakkie – the Afrikaans word bakkie is ambiguous in that it could take the meaning of either bowl or truck, and so the semantically compatible words plate/bord were substituted; (3) bee/by – the Afrikaans word by is a homophone, and could be heard as taking the meaning of the English words at, bee, or mood; hence, and to ensure that the word was understood in its original semantic category (i.e., insects), we used the Afrikaans word gogga, as a generic description of a bug.

References

- Alcock KJ, Holding PA, Mung'ala-Odera V, Newton CR. Constructing tests of cognitive abilities for schooled and unschooled children. J Cross-Cult Psychol. 2008;39:529–552. [Google Scholar]

- DSM-IV-TR: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson P, Anderson V, Lajoie G. The Tower of London test: validation and standardisation for pediatric populations. Clin Neuropsychol. 1996;10:54–65. [Google Scholar]

- Ardila A. Cultural values underlying psychometric cognitive testing. Neuropsychol Rev. 2005;15:185–195. doi: 10.1007/s11065-005-9180-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer RM. Brain damage caused by collision with forensic neuropsychologists. Abstracted from a paper presented at the 25th meeting of the International Neuropsychological Society; Orlando, FL. 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bellamy C UNICEF. The state of the world's children 2005: childhood under threat. New York: UNICEF; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Braga L. International handbook of cross-cultural neuropsychology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Brickman AM, Cabo R, Manly JJ. Ethical issues in cross-cultural neuropsychology. Appl Neuropsychol. 2006;13:91–100. doi: 10.1207/s15324826an1302_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brislin RW. Cross-cultural research in psychology. Annu Rev of Psychol. 1983;34:363–400. [Google Scholar]

- Bryden PJ, Roy EA. A new method of administering the Grooved Pegboard Test: Performance as a function of handedness and sex. Brain Cogn. 2005;58:258–268. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burman S, Reynolds P. The contexts of childhood in South Africa. Johannesburg: Raven Press; 1986. Growing up in a divided society. [Google Scholar]

- Cave J, Grieve K. Quality of education and performance on neuropsychological tests of executive functioning. New Voices in Psychology. 2009;5:29–48. [Google Scholar]

- Corke MAS. Business, poverty and education. Paper presented at the Second Carnegie inquiry into poverty and development in Southern Africa.1984. [Google Scholar]

- de Rotrou J, Wenisch E, Chausson C, Dray F, Faucounau V, Rigaud AS. Accidental MCI in healthy subjects: a prospective longitudinal study. Eur J Neurol. 2005;12:879–885. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2005.01100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farah MJ. Social, legal, and ethical implications of cognitive neuroscience: “neuroethics” for short. J Cogn Neurosci. 2007;19:363–364. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2007.19.3.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrett HL, Carey PD, Thomas KGF, Tapert SF, Fein G. Neuropsychological performance of South African treatment-naive adolescents with alcohol dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;110:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foxcroft CD. Psychological testing in South Africa: perspectives regarding ethical and fair practices. Eur J Psychol Assess. 1997;13:229–235. [Google Scholar]

- Foxcroft CD. Ethical issues related to psychological testing in Africa: what I have learned (so far) Online Readings in Psychology and Culture. 2002;2:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Foxcroft CD. Planning a psychological test in the multicultural South African context. SAJIP. 2004;30:8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Foxcroft CD, Roodt G. An introduction to psychological assessment in the South African context. 2nd. Cape Town: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Giedd JN, Keshavan M, Paus T. Why do many psychiatric disorders emerge during adolescence? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:947–957. doi: 10.1038/nrn2513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogtay N, Giedd JN, Lusk L, Hayashi KM, Greenstein D, Vaituzis C, et al. Dynamic mapping of human cortical development during childhood through early adulthood. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:8174–8179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402680101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieve KW. Factors affecting assessment results. In: Foxcroft C, Roodt G, editors. An introduction to psychological assessment in the South African context. 2nd. Cape Town: Oxford University Press; 2005. pp. 225–241. [Google Scholar]

- Grieve KW, van Eeden R. A preliminary investigation of the suitability of the WAIS-III for Afrikaans-speaking South Africans. SAJP. 2010;40:262–271. [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Grant I, Matthews CG. Differences in neuropsychological test performance associated with age, education, and sex. In: Grant I, Adams K, editors. Neuropsychological assessment of neuropsychiatric disorders. New York: Oxford University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- I Fortuny LA, Garolera M, Romo DH, Feldman E, Barillas HF, Keefe R, et al. Research with Spanish-speaking populations in the United States: lost in translation. A commentary and a plea. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2005;27:555–564. doi: 10.1080/13803390490918282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Test Commission. International guidelines for test use. [Accessed 12 June 2011];2000 http://www.intestcom.org.

- International Test Commission. International test commission guidelines for translating and adapting tests. [Accessed 26 June 2011];2010 http://www.intestcom.org.

- Jinabhai CC, Taylor M, Rangongo MF, Mkhize NJ, Anderson S, Pillay BJ, et al. Investigating the mental abilities of rural Zulu primary school children in South Africa. Ethn Health. 2004;9:17–36. doi: 10.1080/13557850410001673978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn M. For whom the bell tolls: disparities in performance in senior certificate mathematics and physical science. Persp Edu. 2004;22:149–156. [Google Scholar]

- Kanjee A. Cross-cultural test adaptation and translation. In: Foxcroft C, Roodt G, editors. An introduction to psychological assessment in the South African context. 2nd. Cape Town: Oxford University Press; 2005. pp. 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Ryan N. The Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School Aged Children (6-18 years) Lifetime Version. [Accessed 20 June 2011];1996 http://www.wpic.pitt.edu\ksads.

- Lafayette Instrument Company. Grooved Pegboard user's manual. Indiana: Lafayette Instrument Company; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lezak MD, Howieson D, Loring D. Neuropsychological Assessment. 4th. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Llorente AM, Williams J, Satz P, D'Elia LF. Children's Color Trails Test: professional manual. Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Luna B. Developmental changes in cognitive control through adolescence. Adv Child Dev Behav. 2009;37:233–278. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2407(09)03706-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maj M, D'Elia L, Satz P, Janssen R, Zaudig M, Uchimaya C, et al. Evaluation of two new neuropsychological tests designed to minimize cultural bias in the asssessment of HIV-1 seropositive persons: a WHO study. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 1993;8:123–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maj M, Janssen R, Satz P, Zaudig M, Starace F, Boor D, et al. The World Health Organization's cross-cultural study on neuropsychiatric aspects of infection with the human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1). Preparation and pilot phase. Br J Psychiatry. 1991;159:351–356. doi: 10.1192/bjp.159.3.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manly JJ. Advantages and disadvantages of separate norms for African Americans. Clin Neuropsychol. 2005;19:270–275. doi: 10.1080/13854040590945346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manly JJ. Deconstructing race and ethnicity: implications for measurement of health outcomes. Med Care. 2006;44(11 Suppl 3):S10–16. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000245427.22788.be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manly JJ. Critical issues in cultural neuropsychology: profit from diversity. Neuropsychol Rev. 2008;18:179–183. doi: 10.1007/s11065-008-9068-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manly JJ, Byrd DA, Touradji P, Stern Y. Acculturation, reading level, and neuropsychological test performance among African American elders. Appl Neuropsychol. 2004;11:37–46. doi: 10.1207/s15324826an1101_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manly JJ, Echemendia RJ. Race-specific norms: using the model of hypertension to understand issues of race, culture, and education in neuropsychology. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2007;22:319–325. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manly JJ, Jacobs DM, Touradji P, Small SA, Stern Y. Reading level attenuates differences in neuropsychological test performance between African American and White elders. Journal Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2002;8:341–348. doi: 10.1017/s1355617702813157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin M, Allan A, Allan MM. The use of psychological tests by Australian psychologists who do assessments for the courts. Aust J Psychol. 2001;53:77–82. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews CG, Klove K. Instruction manual for the Adult Neuropsychology Test Battery. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Medical School; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- May PA, Gossage JP, Marais AS, Adnams CM, Hoyme HE, Jones KL, et al. The epidemiology of fetal alcohol syndrome and partial FAS in a South African community. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88:259–271. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitrushina M, Boone KB, Razani J, D'Elia LF. Handbook of normative data for neuropsychological assessment. 2nd. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mok N, Tsang L, Lee TM, Llorente AM. The impact of language on the equivalence of trail making tests: findings from three pediatric cohorts with different language dominance. Appl Neuropsychol. 2008;15:123–130. doi: 10.1080/09084280802083962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molteno C. A longitudinal study involving preschool coloured children in Cape Town. University of Cape Town; Cape Town: 1985. The relationship between growth, development and social milieu. [Google Scholar]

- Motala S. Education resourcing in post-apartheid South Africa: the impact of finance equity reforms in public schooling. Persp Edu. 2006;24:79–93. [Google Scholar]

- Nell V. Cross-cultural neuropsychological assessment: theory and practice. New Jersey: Erlbaum; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- O'Gorman M. Educational disparity and racial earnings inequality. University of Toronto; Toronto: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Olness K. Effects on brain development leading to cognitive impairment: a worldwide epidemic. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2003;24:120–130. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200304000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrosky-Solis F, Canseco E, Quintanar L, Navarro E, Meneses S, Ardila A. Sociocultural effects in neuropsychological assessment. Int J Neurosci. 1985;27:53–66. doi: 10.3109/00207458509149134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponton MO, Satz P, Herrera L, Ortiz F, Urrutia CP, Young R, et al. Normative data stratified by age and education for the Neuropsychological Screening Battery for Hispanics (NeSBHIS): initial report. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 1996;2:96–104. doi: 10.1017/s1355617700000941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosin J, Levett A. The Trail Making Test: performance in a non-clinical sample of children aged 10 to 15 years. SAJP. 1989;19:14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Rosselli M, Ardila A. The impact of culture and education on non-verbal neuropsychological measurements: a critical review. Brain Cogn. 2003;52:326–333. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2626(03)00170-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosselli M, Ardila A, Bateman JR, Guzman M. Neuropsychological test scores, academic performance, and developmental disorders in Spanish-speaking children. Dev Neuropsychol. 2001;20:355–373. doi: 10.1207/S15326942DN2001_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosselli M, Tappen R, Williams C, Salvatierra J, Zoller Y. Level of education and category fluency task among Spanish speaking elders: number of words, clustering, and switching strategies. Neuropsychol Dev Cogn B Aging Neuropsychol Cogn. 2009;16:721–744. doi: 10.1080/13825580902912739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruff RM, Parker SB. Gender- and age-specific changes in motor speed and eye-hand coordination in adults: normative values for the Finger Tapping and Grooved Pegboard Tests. Percept Mot Skills. 1993;76(3 Pt 2):1219–1230. doi: 10.2466/pms.1993.76.3c.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruffieux N, Njamnshi AK, Mayer E, Sztajzel R, Eta SC, Doh RF, et al. Neuropsychology in Cameroon: first normative data for cognitive tests among school-aged children. Child Neuropsychol. 2010;16:1–19. doi: 10.1080/09297040902802932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushton JP, Skuy M. Performance on Raven's Matrices by African and White university students in South Africa. Intelligence. 2000;28:251–265. [Google Scholar]

- Rushton JP, Skuy M, Bons TA. Construct validity of Raven's Advanced Matrices for African and Non-African engineering students in South Africa. Int J Select Assess. 2004;12:10. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw P, Greenstein D, Lerch J, Clasen L, Lenroot R, Gogtay N, et al. Intellectual ability and cortical development in children and adolescents. Nature. 2006;440:676–679. doi: 10.1038/nature04513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuttleworth-Edwards AB, Donnelly MJ, Reid I, Radloff SE. A cross-cultural study with culture fair normative indications on WAIS-III Digit Symbol-Incidental Learning. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2004a;26:921–932. doi: 10.1080/13803390490370789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuttleworth-Edwards AB, Kemp RD, Rust AL, Muirhead JG, Hartman NP, Radloff SE. Cross-cultural effects on IQ test performance: a review and preliminary normative indications on WAIS-III test performance. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2004b;26:903–920. doi: 10.1080/13803390490510824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuttleworth-Jordan AB. On not reinventing the wheel: a clinical perspective on culturally relevant test usage in South Africa. SAJP. 1996;26:96–102. [Google Scholar]

- Shuttleworth-Jordan AB. Age and education effects on brain-damaged subjects: ‘negative’ findings revisited. Clin Neuropsychol. 1997;11:205–209. [Google Scholar]

- Skuy M, Gewer A, Osrin Y, Khunou D, Fridjhon P, Rushton JP. Effects of mediated learning experience on Raven's matrices scores of African and non-African university students in South Africa. Intelligence. 2002;30:221–232. [Google Scholar]

- Skuy M, Schutte E, Fridjhon P, O'Carroll S. Suitability of published neuropsychological test norms for urban African secondary school students in South Africa. Pers Ind Diff. 2001;30:1413–1425. [Google Scholar]

- Skuy M, Taylor M, O'Carroll S, Fridjhon P, Rosenthal L. Performance of black and white South African children on the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-- Revised and the Kaufman Assessment Battery. Psychol Rep. 2000;86:727–737. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2000.86.3.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snodgrass JG, Vanderwart M. A standardized set of 260 pictures: norms for name agreement, familiarity and visual complexity. J Exp Psychol Hum Learn. 1980;6:174–215. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.6.2.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonn B, Collett K. Community development through early literacy: 1: engaging with schools, families and communities. Paper presented at the The 21st biennial international congress of the International Society for the Study of Behavioural Development.2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sowell ER, Thompson PM, Toga AW. Mapping changes in the human cortex throughout the span of life. Neuroscientist. 2004;10:372–392. doi: 10.1177/1073858404263960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics South Africa. Community Survey Revised Version. [Accessed 20 June 2011];2007 www.statssa.gov.za.

- Strauss E, Sherman EMS, Spreen O. A compendium of neuropsychological tests: administration, norms, and commentary. 3rd. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson LL, Heaton KR, Matthews CG, Grant I. Comparison of preferred and nonpreferred hand performance on four neuropsychological motor tasks. Clin Neuropsychol. 1987;1:324–334. [Google Scholar]

- Touradj P, Manly JJ, Jacobs DM, Stern Y. Neuropsychological test performance: a study of non-Hispanic White elderly. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2001;23:643–649. doi: 10.1076/jcen.23.5.643.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trites RL. Neuropsychological test manual. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Royal Ottawa Hospital; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Vakil E, Blachstein H, Sheinman M. Rey AVLT: developmental norms for children and the sensitivity of different memory measures to age. Child Neuropsychol. 1998;4:161–177. [Google Scholar]

- van der Berg S. Education, poverty and inequality in South Africa. Paper presented at the Conference for Economic Growth and Poverty in Africa.2002. [Google Scholar]

- van der Berg S. Apartheid's enduring legacy: inequalities in education. J Afr Econ. 2011;16:849–880. [Google Scholar]

- van der Berg S, Burger O. Education and socio-economic differentials: a study of school performance in the Western Cape. S Afr J Econ. 2003;71:496–522. [Google Scholar]

- Western Cape Education Department. WCED homepage. [Accessed 28 May 2011];2010 www.wced.wcape.gov.sa.

- WHO. World health statistics 2010. Geneva, Switzerland: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Williams J, Rickert V, Hogan J, Zolten AJ, Satz P, D'Elia LF, et al. Children's color trails. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 1995;10:211–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams SL, Williams DR, Stein DJ, Seedat S, Jackson PB, Moomal H. Multiple traumatic events and psychological distress: the South Africa stress and health study. J Trauma Stress. 2007;20:845–855. doi: 10.1002/jts.20252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong TM. Ethical controversies in neuropsychological test selection, administration, and interpretation. Appl Neuropsychol. 2006;13:68–76. doi: 10.1207/s15324826an1302_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong TM, Fujii DE. Neuropsychological assessment of Asian Americans: demographic factors, cultural diversity, and practical guidelines. Appl Neuropsychol. 2004;11:23–36. doi: 10.1207/s15324826an1101_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Paper presented at the 59th WMA General Assembly; Seoul. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Yurgelun-Todd D. Emotional and cognitive changes during adolescence. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2007;17:251–257. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]