In 1950, the Noble Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to two chemists and a physician for the discovery and use of cortisone, a classic prohormone devoid of inherent glucocorticoid activity (1). This steroid was active because of its transformation, by reduction of the 11-keto into an 11-hydroxyl group, to cortisol, the natural human glucocorticoid. Since then, we have learned a great deal about cortisone and cortisol and the enzymes that catalyze their inter-conversion to each other in glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid target tissues. In general, two enzymes catalyze these reactions. 11β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (11β-HSD) type 1 is responsible for potentiating the actions of glucocorticoids in many target tissues by converting cortisone to cortisol. In contrast, 11β-HSD type 2 works in the opposite direction and is responsible for converting cortisol into cortisone. This enzyme protects the mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) from the effects of cortisol, which has a high binding affinity for this receptor and inherent mineralocorticoid activity. In this issue of PNAS, Sandeep et al. (2) suggest that use of a 11-β-HSD type 1 enzyme inhibitor could be useful in the treatment of cognitive dysfunction in elderly men and patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. The results are promising for a broad spectrum of potential therapeutic applications of such inhibitors but raise several questions as to whether such agents will ever reach clinical practice. These questions have to do with tissue specificity, dose optimization, and chronicity of therapy.

Glucocorticoids are ubiquitous, highly pervasive nuclear hormones (3, 4). They exert their actions in almost all tissues, influencing the expression of a large proportion of the human genome. Binding of the glucocorticoid to its receptor is followed by a multistep process, ultimately changing the transcription rates of target genes. A large number of molecules participate directly or indirectly in the glucocorticoid signaling cascade (3, 5). Glucocorticoids are pivotal in many aspects of resting and stress-related homeostasis, the latter including both behavioral and physical adaptation (3, 6). Resting homeostasis depends on the presence of a constant day-to-day exposure of our tissues to glucocorticoids, while the secretion of these hormones is increased during stress for a limited time period. The relative stability of cortisol secretion is maintained through an elaborate negative feedback regulatory system located in the brain and pituitary gland. The protective value of this rheostatic system to our organism is apparent by fact that disruption of glucocorticoid homeostasis characterized by either excess or deficient secretion or action results in Cushing's syndrome or Addison's disease, respectively, two very serious, potentially lethal clinical disorders (7). In both conditions, glucocorticoid excess or deficiency cause changes in many brain and peripheral functions (Table 1). In Cushing's syndrome, we see pathologic brain function changes both before and after the correction of hypercortisolism, while patients treated chronically with exogenous glucocorticoids may develop manifestations of Cushing's syndrome, as well as a distinct glucocorticoid withdrawal syndrome, when an abrupt return of high doses of glucocorticoids to normal replacement doses is attempted (8–10).

Table 1. Expected clinical manifestations in tissue-specific glucocorticoid excess or hypersensitivity vs. deficiency or resistance.

| Tissue/system | Cushing's syndrome/glucocorticoid hypersensitivity | Addison's disease/glucocorticoid resistance |

|---|---|---|

| Nervous system | ||

| Arousal/fear systems | Anxiety | Asthenia |

| Insomnia | ||

| Reward system | Depression | Depression |

| Hippocampus | Memory dysfunction | Memory dysfunction |

| Associative cortex | Executive dysfunction | Executive dysfunction |

| Pain and fatigue systems | Fatigue | Hyperalgesia |

| Fatigue | ||

| Sleep centers | Poor quality sleep | Poor quality sleep |

| Liver | +Gluconeogenesis | —Gluconeogenesis |

| +Lipogenesis | ||

| Skeletal muscles | Insulin resistance | +Insulin sensitivity |

| Atrophy (sarcopenia) | Asthenia/fatigue | |

| Bone/growth | Osteoporosis | |

| Growth stunting | ||

| Adipose tissue | Obesity | Loss of weight |

| Cardiovascular system | Hypertension | Hypotension |

| Immune/inflammatory reaction | Immune suppression (innate and T helper 1-directed immunity) | Excessive inflammation/autoimmunity, allergy |

Individual glucocorticoid target tissues may express the clinical manifestations seen in Cushing's syndrome or Addison's disease, when the effect of glucocorticoids is excessive or deficient (4, 5). These manifestations are summarized in Table 1. Two obvious targets for blocking excess glucocorticoid effects in our tissues are glucocorticoid receptor (GR)-specific antagonists, such as RU 486, and 11β-HSD type 1 inhibitors, such as carbenoxolone, although neither of them is exclusively specific to the GR or the enzyme. Excess effect of these agents could potentially produce the tissue-specific pathology that characterizes glucocorticoid deficiency, suggesting that the therapeutic benefit of such agents can only be achieved within a range of doses that allows optimal glucocorticoid action.

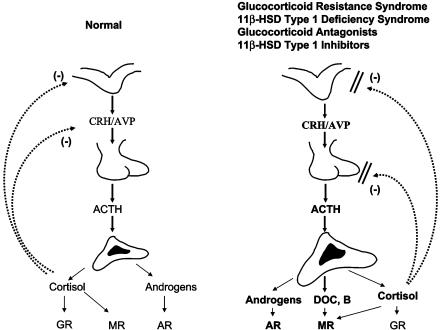

Administration of GR antagonists or 11β-HSD type 1 blockers to persons with an intact hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis would be expected to create resistance of target tissues to glucocorticoids, including regulatory feedback centers of the HPA axis in the brain and pituitary gland (Fig. 1). This would lead to a compensatory activation of the HPA axis that would try to correct for the perceived glucocorticoid action deficit throughout the body. The degree of the HPA axis activation, however, depends on the ability of the drugs to reach these regulatory centers and on the presence and quantity of the 11β-HSD type 1 enzyme in these tissues. Data from RU 486 administration and from the naturally occurring familial/sporadic glucocorticoid resistance syndrome, a condition that results from congenital glucocorticoid signaling system disturbances, suggest that compensation may occur but at the expense of a chronically hyperstimulated adrenal gland (11, 12) (Fig. 1). The latter produces, in addition to the necessary extra cortisol, excess mineralocorticoid precursors, such as corticosterone and deoxycorticosterone, and adrenal androgens, such as dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and Δ4-androstenedione, that may produce manifestations of mineralocorticoid and/or androgen excess. The former may be associated with salt retention and arterial hypertension, and the latter may result in virilization of children and masculinization of women. Chronic female hyperandrogenism may be expressed with acne, hirsutism, menstrual irregularities, male pattern baldness, infertility, and development of the secondary polycystic ovary syndrome.

Fig. 1.

A normally functioning (Left) and a hyperfunctioning (Right) HPA axis, the latter because of congenital generalized familial or sporadic glucocorticoid resistance, treatment with a glucocorticoid antagonist, congenital deficiency of 11β-HSD type 1, or treatment with a 11β-HSD type 1 inhibitor. The hypersecretion of cortisol, corticosterone (B), and deoxycorticosterone (DOC) may cause sodium retention and hypertension via excessive activation of the MR; the hypersecretion of adrenal androgens may cause virilization in children or masculinization in women via the androgen receptor (AR). The degree of mineralocorticoid or androgen excess effect depends on the degree of axis hyperfunction and the sensitivity of the mineralocorticoid and androgen signaling systems. ACTH, corticotropin; AVP, arginine vasopressin; CRH, corticotropin-releasing hormone.

The above pathophysiologic mechanisms are in action in patients with the syndrome of 11β-HSD type 1 deficiency (13). In these patients, the compensatory increase of adrenal function is generally small, resulting primarily in mild hyperandrogenism. If one examines the clinical spectrum of the glucocorticoid resistance syndrome, one also sees that the less severely affected subjects develop only hyperandrogenism, suggesting that the phenotype of the disorder is a matter of degree rather then different pathophysiologic mechanisms. Some of the tissues of these patients, such as adipose tissue, are protected from the excessive effects of glucocorticoids in Cushing's syndrome, preventing the expression of the typical centrally obese phenotype. Similarly, and as would have been expected, the 11β-HSD type 1 knockout mouse is protected from developing obesity.

Whether circulating glucocorticoid levels increase with age is a controversial issue. It appears that healthy aging is associated with normal HPA axis function until a very late age (14). In contrast, general population studies in aging subjects, including all subjects but persons with major morbidities, clearly show a progressively increasing hyperfunction of the HPA axis with age (15), and this may have pathologic significance for many physiologic functions (Table 1). The same phenomenon has been observed in younger patients with a history of major affective disorder, as well as in poorly controlled patients with diabetes mellitus (16, 17). Thus, aging subjects with mild hypercortisolism or patients with depression or diabetes mellitus may be the right target populations for novel glucocorticoid antagonist or 11β-HSD type 1 inhibitor therapies.

At this time, the pharmaceutical industry is rigorously searching for, developing, and/or testing glucocorticoid antagonists and 11β-HSD type 1 inhibitors for the treatment of a host of human disorders that might benefit from blockade of glucocorticoid action, such as obesity, the dysmetabolic syndrome, diabetes type 2, melancholic depression, osteoporosis, etc. Three potential problems are evident. (i) Tissue specificity is a major issue for both classes of agents. For the GR antagonists, it is possible that the allosteric changes of the GR induced by an agent may influence glucocorticoid actions differently between different genes, cells, or tissues. For the 11β-HSD type 1 inhibitors, the presence or absence of the enzyme and its quantity in different tissues play a role as to which tissues will be affected the most. For both drug classes, a potential discrepancy between the effects of the drug in the regulation of the negative feedback regulatory centers of the HPA axis and any other tissues not participating in this regulation may produce pathology (4, 5) (Table 1). (ii) Dose optimization is also important. Not to overtreat or undertreat will be crucial, because our tissues operate best at an optimum range of glucocorticoid concentrations and actions. We should be titrating the dose for optimal effect at multiple tissues, which may be hard. (iii) Chronicity of treatment may be particularly critical in children and women, because even small sustained elevations of circulating adrenal androgens over a long time period may produce undesired side effects from hyperandrogenism, such as manifestations of virilization in children and masculinization in women. It is hoped that these potential shortcomings of the above drug classes will not be a major hurdle and that, eventually, clinically useful compounds with glucocorticoid antagonist or 11β-HSD type 1 inhibitory activity will be available in clinical practice.

See companion article on page 6734.

References

- 1.Chrousos, G. P. (2001) Endocrinology and Metabolism, eds. Felig, P. & Frohman, L., (McGraw–Hill, New York), 4th Ed., pp. 609-632.

- 2.Sandeep, T. C., Yau, J. L. W., MacLullich, A. M. J., Noble, J., Deary, I. J., Walker, B. R. & Seckl, J. R. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 6734-6739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Franchimont, D., Kino, T., Galon, J., Meduri, G. U. & Chrousos, G. P. (2003) Neuroimmunomodulation 10, 247-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chrousos, G. P., Charmandari, E. & Kino, T. (2004) J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 89, 563-564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kino, T., De Martino, M. U., Charmandari, E., Mirani, M. & Chrousos, G. P. (2003) J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 85, 457-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chrousos, G. P. (1998) Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 851, 311-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller, W. & Chrousos, G. P. (2001) Endocrinology and Metabolism, eds. Felig, P. & Frohman, L. (McGraw–Hill, New York), 4th Ed., pp. 387-524.

- 8.Dorn, L. D., Burgess, E. S., Dubbert, B., Kling, M., Gold, P. W. & Chrousos, G. P. (1995) Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxford) 43, 433-442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dorn, L. D., Burgess, E. S., Friedman, T. C., Dubbert, B., Gold, P. W. & Chrousos, G. P. (1997) J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 82, 912-919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hochberg, Z., Pacak, K. & Chrousos, G. P. (2003) Endocrine Rev. 24, 523-548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chrousos, G. P., Detera-Wadleigh, S. & Karl, M. (1993) Ann. Int. Med. 119, 1113-1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laue, L., Lotze, M. T., Chrousos, G. P., Barnes, K., Loriaux, D. L. & Fleisher, T. A. (1990) J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 71, 1474-1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jamieson, A., Wallace, A. M., Andrew, R., Nunez, B. S., Walker, B. R., Fraser, R., White, P. C. & Connell, J. M. (1999) J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 84, 3570-3574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pavlov, E. P., Harman, M. S., Chrousos, G. P., Loriaux, D. L. & Blackman, M. R. (1986) J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 62, 767-772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vgontzas, A. N., Zoumakis, M., Bixler, E. O., Lin, H.-M., Prolo, P., Vela-Bueno, A., Kales, A. & Chrousos, G. P. (2003) J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 88, 2087-2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gold, P. W. & Chrousos, G. P. (2002) Mol. Psychiatry 7, 254-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roy, M. S., Roy, A., Gallucci, W. T., Collier, B., Young, K., Kamilaris, T. C. & Chrousos, G. P. (1993) Metabolism 42, 696-700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]