Abstract

Bacillus subtilis is a bacterium that undergoes a developmental program of sporulation in response to starvation. At the core of the program are σ factors, whose regulated spatiotemporal activation controls much of the gene expression. Activation of pro-σK in the mother cell compartment involves regulated intramembrane proteolysis (RIP) in response to a signal from the forespore. RIP is a poorly understood process that is conserved in prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Here, we report a powerful system for studying RIP of pro-σK. Escherichia coli was engineered to coexpress the putative membrane-embedded metalloprotease SpoIVFB with pro-σK and potential inhibitors of RIP. Overproduction of SpoIVFB and pro-σK in E. coli allowed accurate and abundant proteolytic processing of pro-σK with the characteristics expected for SpoIVFB acting as an intramembrane-cleaving protease (I-Clip). Coexpression of BofA in this system led to formation of a BofA–SpoIVFB complex and marked inhibition of pro-σK processing. Mutational analysis identified amino acids in BofA that are necessary for complex formation and inhibition of processing, leading us to propose that BofA inhibits SpoIVFB metalloprotease activity by providing a metal ligand, analogous to the cysteine switch mechanism of matrix metalloprotease regulation. The approach described herein should be applicable to studies of other RIP events and amenable to developing in vitro assays for I-Clips.

The abilities of cells to send signals, and to sense and respond to signals from other cells or from the environment, are essential features of developmental and adaptive processes. Regulated intramembrane proteolysis (RIP) has emerged as an important and widely conserved mechanism for controlling signaling pathways in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes (1). RIP involves cleavage of a protein in a transmembrane domain, releasing a part of the protein that in most cases regulates transcription or acts as a signal. Proteases believed to catalyze intramembrane cleavage occur in large families that are typically conserved from archaea to humans, and sometimes in bacteria as well (2). For example, one of the first intramembrane-cleaving proteases (I-Clips) identified, human site-2 protease (S2P) (3), has orthologs in Bacillus subtilis (SpoIVFB) (4, 5) and Escherichia coli (YaeL) (6, 7). Also, Drosophila and bacterial I-Clips in the rhomboid family recognize the same substrate motif and can be functionally interchanged (8, 9). RIP has been implicated in generating bacterial mating (10) and quorum sensing signals (11), and in the extracytoplasmic stress response of E. coli (6, 7). In metazoans, RIP is believed to control the unfolded protein stress response, cholesterol and fatty acid biosynthesis, epidermal growth factor and ErbB4 receptor signaling, Notch signaling, and processing of the Alzheimer precursor protein (1, 2). Elucidating mechanisms of RIP is important for understanding diverse signaling pathways and potentially for treating disease.

Bacterial sporulation provides a model to study RIP. When starved, certain bacteria undergo endosporulation, in which the cell is divided into mother cell and forespore compartments. Differential gene expression in the two compartments ensues, and signaling between the compartments ensures coordinate gene regulation and morphogenesis (12). One of the signaling pathways in B. subtilis, termed the σK checkpoint (Fig. 1) (13), appears to involve RIP. σK is synthesized as an inactive precursor, pro-σK, that associates with membranes in cells (13–15). SpoIVFB is believed to be an I-Clip that processes pro-σK to σK on the basis of the following: a B. subtilis spoIVFB mutant is defective in processing (14), coexpression of spoIVFB and sigK (encoding pro-σK) in growing B. subtilis allows processing (16, 17), SpoIVFB is a membrane protein (18) with sequence similarity to the S2P family of I-Clips (4, 5, 19), and mutational analysis of conserved motifs in apparent transmembrane segments of SpoIVFB supports the idea that it is a metalloprotease (4, 5). However, as is the case for all I-Clips, cleavage of a physiological substrate in vitro with purified enzyme has not been accomplished.

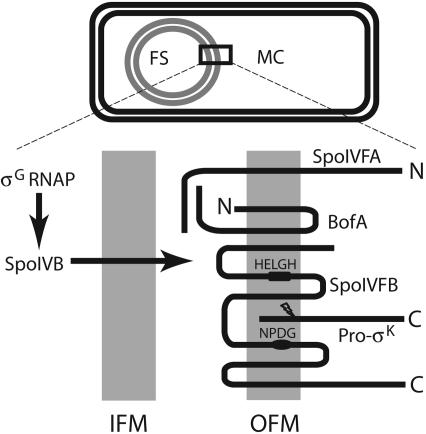

Fig. 1.

Model showing proteins involved in the σK checkpoint. (Upper) A sporangium in which the forespore (FS) has been engulfed within the mother cell (MC). (Lower) An expanded view of the inner forespore membrane (IFM) and the outer forespore membrane (OFM), which surround the FS. σG RNA polymerase (σG RNAP) transcribes spoIVB in the FS (21). SpoIVB (not to be confused with SpoIVFB) is believed to cross the IFM and activate pro-σK processing by SpoIVFB (lightning bolt). The topologies depicted for BofA, SpoIVFA, and SpoIVFB are based on analysis of lacZ and phoA fusions in E. coli (34, 40). The HELGH and NPDG sequences of SpoIVFB that are critical for RIP of pro-σK (4, 5), are predicted to be in transmembrane segments. Release of σK from the OFM allows formation of σK RNA polymerase in the MC, which transcribes genes whose products help form the cortex and coat layers of the spore.

Also lacking is an understanding of how pro-σK processing is regulated. SpoIVFB forms a complex with SpoIVFA and BofA in the outer forespore membrane (OFM) (Fig. 1) (18, 20). This complex appears to be inactive for pro-σK processing, and it is thought to be activated by SpoIVB, a serine protease synthesized in the forespore that is believed to traverse the inner forespore membrane (IFM) (21–23). The observation that BofA stabilizes SpoIVFA led to the model that SpoIVFA inhibits SpoIVFB I-Clip activity until the SpoIVB signal comes from the forespore (24). The level of SpoIVFA decreases when pro-σK processing begins during sporulation, and the decrease of SpoIVFA depends on SpoIVB (25, 26). However, a form of SpoIVFA made more stable by fusion with the green fluorescent protein (GFP) did not prevent processing (20). Also, conditions were found under which the level of SpoIVFA decreased, but SpoIVFB did not become active for processing of pro-σK (25). These results suggested that SpoIVFA might not be the primary inhibitor of SpoIVFB. Because SpoIVFA localizes to the membrane surrounding the forespore and helps BofA and SpoIVFB to do likewise, SpoIVFA was proposed to assemble a complex in which BofA inhibits SpoIVFB I-Clip activity (20).

Here, we show that SpoIVFB is sufficient for accurate and abundant proteolytic processing of pro-σK in a heterologous host. By expressing different components of the σK checkpoint in E. coli, we demonstrate that BofA can inhibit pro-σK processing in the absence of SpoIVFA. We present a model for the mechanism by which BofA inhibits SpoIVFB I-Clip activity, based on analogy with matrix metalloprotease inhibition and the results of mutations in bofA. We discuss RIP of pro-σK in light of the recent finding that the SpoIVB serine protease can cleave SpoIVFA in vitro (26).

Materials and Methods

Plasmids. The plasmids used in this study are described briefly in Table 1. Details of their construction are in Tables 2 and 3, which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site. The methods used have been described previously (27). DNA sequencing of all cloned PCR products and all genes subjected to mutagenesis (QuikChange kit, Stratagene) confirmed the presence of the desired sequences.

Table 1. Plasmids used in this study.

| Plasmid | Description |

|---|---|

| pETpro-σK | KmR; T7-pro-σKH6* |

| pZR2 | ApR; T7-H10SpoIVFB-GFP |

| pZR6 | KmR; T7-H10SpoIVFB-GFP |

| pZR12 | KmR; T7-pro-σK(1—126)H6 |

| pZR13 | ApR; T7-H10SpoIVFB-GFP |

| pZR16 | ApR; T7-H10SpoIVFB-GFP/T7-BofA |

| pZR24 | ApR; T7-H10SpoIVFB-E44Q-GFP |

| pZR33 | ApR; T7-H10SpoIVFB-GFP/SpoIVFA |

| pZR62 | ApR; T7-GFPΔ27BofA |

| pZR63 | KmR; T7-pro-σK(1—126)H6/T7-GFPΔ27BofA |

| pZR64 | ApR; T7-GFPΔ27BofA-G75E |

| pZR65 | ApR; T7-GFPΔ27BofA-H57F |

| pZR67 | ApR; T7-H10SpoIVFB-GFP/T7-GFPΔ27BofA |

| pZR68 | ApR; T7-H10SpoIVFB-GFP/T7-GFPΔ27BofA-G75E |

| pZR70 | KmR; T7-pro-σK(1—126)H6/T7-GFPΔ27BofA-H57F |

| pZR73 | ApR; T7-SpoIVFA |

KmR, kanamycin-resistant; ApR, ampicillin-resistant.

The T7 RNA polymerase promoter (T7) plus the optimum translation initiation sequence in pET-29b was fused to the B. subtilis sigK gene (encoding pro-σK) which had been tagged with six histidine (H6) residues at the C-terminus (40). The descriptions of other plasmids are abbreviated in a similar fashion, and details of their construction are in Tables 2 and 3

Cotransformation and Protein Production. Proteins were produced in the E. coli strain BL21(DE3) (Novagen), which can be induced to synthesize T7 RNA polymerase. To transform this strain with two plasmids bearing different antibiotic resistance genes and different B. subtilis genes fused to a T7 RNA polymerase promoter, 50 ng of each plasmid was electroporated into cells, and tranformants were selected on Luria–Bertani (LB) agar supplemented with kanamycin sulfate (50 μg/ml) and ampicillin (100 μg/ml). To induce expression, transformants were grown in LB liquid containing 50 μg/ml kanamycin and 200 μg/ml ampicillin overnight at 37°C with shaking at 350 rpm, then 200 μl of culture was transferred to 10 ml of fresh LB liquid with antibiotics, and incubation was continued under the same conditions until the culture reached an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.7–0.8, at which time isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (0.5 mM) was added and incubation was continued for 2 h.

Western Blot Analysis. Equivalent amounts of E. coli cells from different cultures were collected from 0.5–1.0 ml of culture (depending on the OD600) by centrifugation (12,000 × g). Unless otherwise specified, extracts were prepared by resuspending cells in 50 μl of lysis buffer [50 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.5/10 mM MgCl2/1 mM EDTA/1 mM Pefabloc (Roche Molecular Biochemicals)/1 mg/ml lysozyme/10 μg/ml DNase I] and incubating for 10 min at 37°C, then adding 50 μl of 2× sample buffer [50 mM Tris·HCl, pH 6.8/4% SDS/20% (vol/vol) glycerol/200 mM DTT/0.03% bromophenol blue] and boiling for 3 min. After centrifugation (12,000 × g), 2 μl of supernatant was loaded onto an SDS/14% Prosieve polyacrylamide gel (Cambrex Bio Science, Rockland, ME) for separation of proteins and Western blot analysis as described previously (25). Antibodies to pentahistidine (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) were used at 1:10,000 dilution.

Fractionation of Cellular Proteins. E. coli from cultures (100 ml) induced as described above were harvested by centrifugation (12,000 × g) and resuspended in 6 ml of PBS, pH 7.2 (Invitrogen), containing 1 mM Pefabloc, 0.5 mg/ml lysozyme, 10 μg/ml DNase I, and 10 μg/ml RNase A, then passed twice through a French pressure cell (American Instruments) at 14,000 lb/in2 (96 MPa). The lysate was centrifuged at 4°C (12,000 × g, 10 min). The supernatant (4.5 ml) was centrifuged at 4°C for 1.5 h at 200,000 × g in a SW50.1 rotor (Beckman). The supernatant served as the cytoplasmic fraction. The pellet was rinsed with PBS, then resuspended in PBS (4.5 ml), and this served as the membrane fraction. To 50 μl of each fraction, 50 μlof2× sample buffer was added. The samples were boiled for 3 min, then subjected to Western blot analysis.

Membrane Solubilization and Affinity Purification of Complexes. Membrane pellets prepared as described above were solubilized with 600 μl of detergent buffer (PBS, pH 7.2/1% digitonin/150 mM NaCl/10% glycerol/1 mM Pefabloc) by rotating for 2 h at 4°C. Samples were then centrifuged at 4°C for 1 h at 100,000 × g in a SW50.1 rotor. The supernatant (500 μl) was collected and diluted with 500 μl of buffer (PBS, pH 7.2/150 mM NaCl, 1 mM Pefabloc). A sample (50 μl) was taken to represent the input, then the rest was mixed with 100 μl cobalt resin slurry (Clontech) by rotating for 1 h at 4°C. Resin was collected by centrifugation at 1,000 × g, washed three times with buffer (PBS, pH 7.2/150 mM NaCl/10 mM imidazole/5% glycerol/1 mM Pefabloc), then eluted with 60 μl of buffer (1× sample buffer containing 200 mM imidazole, 300 mM NaCl, and 10 mM EDTA) by incubating at 50°C for 20 min. A sample (10 μl) was subjected to Western blot analysis.

Results

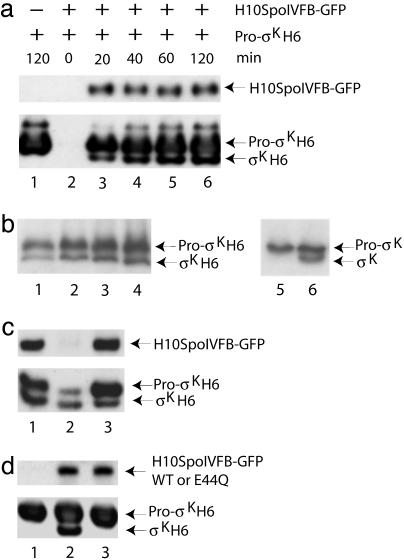

Accurate and Abundant Pro-σK Processing in E. coli. Coexpression of a C-terminally 6-histidine-tagged pro-σK (denoted pro-σKH6) with an N-terminally 10-histidine- and C-terminally GFP-tagged SpoIVFB (denoted H10SpoIVFB-GFP) in E. coli BL21(DE3) resulted in processing of pro-σKH6 (Fig. 2a, lanes 3–6). Processing depended absolutely on H10SpoIVFB-GFP (Fig. 2a, lane 1). The N-terminal amino acid sequence of the processed pro-σKH6 (denoted σKH6) was determined by Edman degradation to be YVKNNAFP, which is identical to that of σK from sporulating B. subtilis (28), so processing was accurate.

Fig. 2.

Accurate and abundant pro-σK processing in E. coli. (a) Western blot analysis of H10SpoIVFB-GFP and pro-σKH6/σKH6 by using penta-His antibodies. Samples were collected at the indicated times after IPTG induction of E. coli bearing only pETpro-σK (lane 1) or both pETpro-σK and pZR2 (lanes 2–6). (b) Comparison of pro-σK processing in E. coli and in sporulating B. subtilis PY79 (41). Whole-cell extracts were subjected to Western blot analysis with antibodies against pro-σK. E. coli bearing pETpro-σK and pZR2 was induced with IPTG for 1 h, extract was prepared and diluted 1,000-fold, then 2 (lane 1), 4 (lane 2), 6 (lane 3), or 8 μl (lane 4) was analyzed. An equivalent amount of B. subtilis (based on the OD600 of the culture) was analyzed at hour 3 (lane 5) and hour 4 (lane 6) of sporulation, using 6 μl of undiluted extract. (c) Fractionation of cell extracts. E. coli bearing pETpro-σK and pZR2 was induced with IPTG for 2 h. The whole-cell lysate after low-speed (12,000 × g) centrifugation (lane 1) and the cytoplasmic (lane 2) and membrane (lane 3) fractions were subjected to Western blot analysis with antibodies against GFP (Upper) or pro-σK (Lower). (d) Effect of an E44Q change in H10SpoIVFB-GFP. E. coli bearing pETpro-σK alone (lane 1) or in combination with pZR2 (lane 2) or pZR24 (lane 3) was induced with IPTG for 2 h, and extracts were subjected to Western blot analysis with penta-His antibodies.

Processing was also abundant in the heterologous host. The engineered E. coli synthesized at least 20 times more SpoIVFB (data not shown) and produced about 1,000 times more σK than an equivalent amount of sporulating B. subtilis (Fig. 2b, compare lanes 3 and 6). Fractionation of cell extracts showed that H10SpoIVFB-GFP is present only in the membrane fraction, as is the majority of pro-σKH6 (Fig. 2c, lane 3). Taken together, our results demonstrate that SpoIVFB is sufficient for accurate and abundant processing of pro-σK in E. coli.

In support of the model that SpoIVFB is a metalloprotease with a transmembrane 43HEXXH47 motif (Fig. 1) in which the conserved glutamic acid (E44) promotes nucleophilic attack by a water molecule on the carbonyl atom of the substrate peptide bond, changing E44 of H10SpoIVFB-GFP to glutamine abolished processing of pro-σKH6 in E. coli (Fig. 2d, lane 3), just as this mutation blocked processing in B. subtilis (4, 5).

BofA Alone Can Inhibit Processing of Pro-σK. Both BofA and SpoIVFA are necessary to inhibit pro-σK processing during B. subtilis sporulation, until a signal from the forespore overcomes the inhibition (13, 21, 29). Recently, two studies have suggested that BofA might be the primary inhibitor of SpoIVFB I-Clip activity, with SpoIVFA aiding in assembly and stabilization of an inhibited complex (20, 25). If this model is correct, we reasoned that overproduction of BofA in the E. coli system might alleviate the need for SpoIVFA and enable BofA alone to inhibit SpoIVFB.

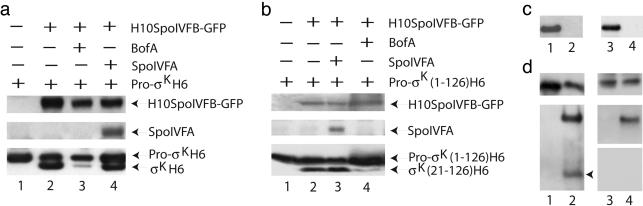

E. coli engineered to overproduce BofA, in addition to H10SpoIVFB-GFP and pro-σKH6, showed a substantial reduction in the level of σKH6 (Fig. 3a, lane 3), consistent with the notion that BofA can inhibit SpoIVFB I-Clip activity. In contrast, production of SpoIVFA had little or no effect on the σKH6 level (Fig. 3a, lane 4).

Fig. 3.

BofA inhibits processing of pro-σK. (a) Effects of BofA or SpoIVFA on processing of pro-σKH6. E. coli cells bearing pETpro-σK alone (lane 1) or in combination with pZR2 (lane 2), pZR16 (lane 3), or pZR33 (lane 4), were induced with IPTG for 2 h to express the indicated proteins. Extracts were prepared as described for fractionation of cellular proteins (Materials and Methods) and the whole-cell lysates after low-speed (12,000 × g) centrifugation were subjected to Western blot analysis using antibodies against GFP (Top), SpoIVA (Middle), or penta-His (Bottom). (b) Effect of BofA or SpoIVFA on processing of pro-σK(1–126)H6. E. coli cells bearing pZR12 alone (lane 1) or in combination with pZR13 (lane 2), pZR33 (lane 3), or pZR16 (lane 4) were induced with IPTG for 2 h, then whole-cell extracts were subjected to Western blot analysis using antibodies against penta-His (Top and Bottom) or SpoIVFA (Middle). (c) Membrane association of GFPΔ27BofA and SpoIVFA. Membrane (lanes 1 and 3) and cytoplasmic (lanes 2 and 4) fractions of E. coli bearing pZR63 (lanes 1 and 2) or pZR33 (lanes 3 and 4), which had been induced with IPTG for 2 h, were subjected to Western blot analysis with antibodies against GFP (lanes 1 and 2, to detect GFPΔ27BofA) or SpoIVFA (lanes 3 and 4). (d) Membrane solubilization and affinity purification of complexes. Detergent-solubilized membranes from E. coli bearing pZR62 alone (lane1) or in combination with pZR6 (lane 2), or bearing pZR73 alone (lane 3) or in combination with pZR6 (lane 4), were subjected to Western blot analysis before (Upper) or after (Lower) affinity purification of complexes (Materials and Methods), using antibodies against GFP (lanes 1 and 2, Upper shows GFPΔ27BofA, Lower shows H10SpoIVFB-GFP as the upper band and GFPΔ27BofA marked with an arrowhead) or, for lanes 3 and 4, antibodies against SpoIVFA (Top and Bottom) or against GFP (Middle, to detect H10SpoIVFB-GFP).

Amino acids 1 through 126 of pro-σK, denoted pro-σK(1–126), are sufficient to serve as a substrate for RIP in sporulating B. subtilis (H. Prince and L.K., unpublished data). This truncated form of pro-σK is also processed in E. coli, if H10SpoIVFB-GFP is coexpressed (Fig. 3b, lane 2). The N-terminal amino acid sequence of the product after processing was determined by Edman degradation to be identical to that of σKH6 produced in E. coli and that of σK produced in sporulating B. subtilis (28), indicating that processing of pro-σK(1–126)H6 is accurate and produces a product we denote σK(21–126)H6. Processing appeared to be inhibited by BofA (Fig. 3b, lane 4), but not by SpoIVFA (Fig. 3b, lane 3). Because it was easier to separate pro-σK(1–126)H6 from σK(21–126)H6 by SDS/PAGE than for the full-length proteins, the C-terminally truncated pro-σK was used in subsequent experiments.

The reduction in the level of σK(21–126)H6 in E. coli engineered to overproduce BofA (Fig. 3b, lane 4) did not result from a change in the stability of σK(21–126)H6. These cells exhibited kinetics of σK(21–126)H6 loss after inhibition of translation by chloramphenicol (200 mg/ml) similar to those of cells not producing BofA (data not shown). Also, BofA did not impair accumulation of pro-σK(1–126)H6 (Fig. 3b, lane 4). Hence, BofA did not appear to have an indirect effect on substrate availability or product stability.

GFPΔ27BofA is a fusion of GFP to amino acid 28 of BofA, which was shown previously to be fully functional in B. subtilis and allow detection of the protein by Western blotting with anti-GFP antibodies (20). When overproduced in E. coli, GFPΔ27BofA was present exclusively in the membrane fraction (Fig. 3c, lane 1), and it appeared to inhibit pro-σK(1–126)H6 processing (Fig. 4a, lane 2) to an extent similar to that of BofA (Fig. 3b, lane 4). SpoIVFA was also present only in the membrane fraction (Fig. 3c, lane 3), so its lack of an effect on processing (Fig. 3b, lane 3) did not appear to result from mislocalization.

Fig. 4.

Amino acid substitutions in BofA impair its ability to inhibit pro-σK(1–126)H6 processing. (a) Effect of a G75E change in BofA. E. coli cells bearing pZR12 and pZR13 (lane 1), pZR67 (lane 2), or pZR68 (lane 3) were induced with IPTG for 2 h to express the indicated proteins. Whole-cell extracts were subjected to Western blot analysis using antibodies against GFP (Top and Middle) or penta-His (Bottom). (b) Effect of a H57F change in BofA. E. coli strains were the same as in a, except lane 3 contained an extract from E. coli bearing pZR13 and pZR70. (c) Membrane association of mutant BofA proteins. Membrane (lanes 1 and 3) and cytoplasmic (lanes 2 and 4) fractions of E. coli bearing pZR64 (lanes 1 and 2) or pZR65 (lanes 3 and 4), which had been induced with IPTG for 2 h, were subjected to Western blot analysis with antibodies against GFP. (d) Membrane solubilization and affinity purification of complexes. Detergent-solubilized membranes from E. coli bearing pZR64 alone (lane 1) or in combination with pZR6 (lane 2), or bearing pZR65 alone (lane 3) or in combination with pZR6 (lane 4), were subjected to Western blot analysis before (Upper) or after (Lower) affinity purification of complexes, using antibodies against GFP.

To test whether BofA or SpoIVFA forms a complex with SpoIVFB in E. coli, we made use of the observation that a BofA–SpoIVFA–SpoIVFB complex can be solubilized from membranes of sporulating B. subtilis with the nonionic detergent digitonin (20). Membranes from E. coli overproducing GFPΔ27BofA or SpoIVFA, and H10SpoIVFB-GFP, were solubilized, then complexes were affinity-purified with cobalt resin, to which the 10-His tag on H10SpoIVFB-GFP was expected to bind. GFPΔ27BofA copurified with H10SpoIVFB-GFP (Fig. 3d, lane 2) and did not bind to the cobalt resin in the absence of H10SpoIVFB-GFP (Fig. 3d, lane 1). SpoIVFA did not copurify with H10SpoIVFB-GFP (Fig. 3d, lane 4). These results demonstrate that GFPΔ27BofA forms a complex with H10SpoIVFB-GFP in E. coli, supporting the idea that BofA directly inhibits SpoIVFB I-Clip activity to bring about the observed reduction in the level of σK(21–126)H6 (Fig. 3b, lane 4).

Specificity of Inhibition by BofA. It was conceivable that formation of an inhibitory complex with SpoIVFB was an artifact of BofA overproduction in E. coli. To test the specificity of the inhibition, we made a single amino acid change in BofA. Previous studies showed that changing the glycine at position 75 to glutamic acid (denoted G75E) impaired BofA's ability to inhibit pro-σK processing in sporulating B. subtilis (13, 30). We engineered this change into the gene encoding GFPΔ27BofA so we could detect the mutant protein.

The G75E change in GFPΔ27BofA impaired its ability to inhibit processing (Fig. 4a, lane 3), despite accumulation of the mutant protein to a level similar to that of wild-type GFPΔ27BofA (Fig. 4a Middle). Unlike the wild-type protein, a substantial amount of GFPΔ27BofA G75E was present in the cytoplasmic fraction (Fig. 4c, lane 2), although a slight majority was in the membrane fraction (Fig. 4c, lane 1). However, GFPΔ27BofA G75E failed to copurify with H10SpoIVFB-GFP after membrane solubilization (Fig. 4d, lane 2). It appears that the G75E change impairs BofA's ability to interact with the SpoIVFB metalloprotease and inhibit intramembrane proteolysis of pro-σK.

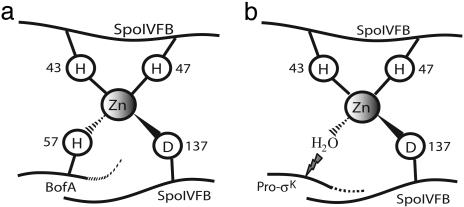

Mechanism of Inhibition by BofA. We considered the possibility that BofA inhibits SpoIVFB by a mechanism analogous to the cysteine switch observed for matrix metalloproteases (31–33). These enzymes are synthesized as latent proenzymes in which the sulfhydryl group of a cysteine residue in the propeptide coordinates the catalytic zinc ion. Interruption of this interaction activates the metalloprotease. By analogy, BofA could provide a ligand to the putative metal ion of SpoIVFB, blocking the active site. GFPΔ27BofA has two potential metal ligands. Alignment of BofA orthologs from B. subtilis, Bacillus halodurans, Bacillus cereus, and Bacillus anthracis revealed that histidine-57, but not cysteine-46, is conserved (Fig. 6, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Changing the histidine at position 57 to phenylalanine (denoted H57F) in GFPΔ27BofA markedly impaired the ability of the protein to inhibit processing of pro-σK(1–126)H6 in E. coli (Fig. 4b, lane 3). The H57F mutant protein accumulated to a level similar to that of the wild-type protein (Fig. 4b, Middle), and GFPΔ27BofA H57F was almost exclusively membrane-associated (Fig. 4c), but it failed to copurify with H10SpoIVFB-GFP after membrane solubilization (Fig. 4d, lane 4). GFPΔ27BofA H57F also was impaired in its ability to inhibit pro-σK processing in sporulating B. subtilis, despite accumulating to a level similar to that of the wild-type protein (Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). In contrast to the H57F substitution in BofA, a C46S change had no effect on its ability to inhibit processing in E. coli (data not shown). These results support a model in which H57 of BofA is a ligand of zinc in SpoIVFB and thereby prevents intramembrane proteolysis of pro-σK.

Discussion

We have established a powerful system for studying RIP of pro-σK and used it to provide evidence that BofA is the primary inhibitor of SpoIVFB I-Clip activity. Our results suggest that a similar approach of overproducing I-Clips, their substrates, and potential regulatory proteins in E. coli, or another vector/host system such as baculovirus-infected insect cells, could be applied to investigate other RIP events.

The large amount of σK produced in E. coli engineered to overproduce H10SpoIVFB-GFP suggests that these cells are the best available starting material for attempts aimed at purifying SpoIVFB and demonstrating I-Clip activity in vitro. The engineered E. coli produced about 1,000-fold more σK (Fig. 2b) and at least 20-fold more H10SpoIVFB-GFP (data not shown) than sporulating B. subtilis expressing sigK (encoding pro-σK) and spoIVFB-gfp from native promoters. Overproducing pro-σK in sporulating B. subtilis did not increase the σK level, as if the protease was limiting (14). Also, expressing sigK and spoIVFB-gfp from a xylose-inducible promoter in growing B. subtilis did not result in more σK produced per cell (17).

Despite the 1,000-fold increase in the σK level in our engineered E. coli, there appears to be room for improvement. Much pro-σK remains unprocessed in the whole-cell extract 2 h after induction with IPTG (Fig. 2a). However, more than half of the overproduced pro-σK is probably inaccessible for RIP, because it pellets upon low-speed centrifugation, suggesting it forms insoluble aggregates (compare the whole-cell extract shown in Fig. 2a, lane 6, with the supernatant after low-speed centrifugation shown in Fig. 2c, lane 1). Nevertheless, a substantial amount of pro-σK is membrane-associated, but not processed (Fig. 2c, lane 3), so SpoIVFB I-Clip activity may be limiting. Alternatively, a factor that stimulates pro-σK processing in sporulating B. subtilis may be missing or suboptimal in the heterologous E. coli host.

By overproducing BofA in our E. coli system, we discovered that BofA is sufficient to markedly inhibit pro-σK processing, providing experimental evidence that BofA is the primary inhibitor of SpoIVFB I-Clip activity. In sporulating B. subtilis, both BofA and SpoIVFA are required to prevent processing of pro-σK until the SpoIVB signal comes from the forespore (13, 21, 29). In the absence of SpoIVFA, GFPΔ27BofA and SpoIVFB-GFP fail to localize to the OFM, and GFPΔ27BofA and native SpoIVFB are less stable (20). In E. coli, GFPΔ27BofA (Fig. 3c) and H10SpoIVFB-GFP (Fig. 2c) are stable and membrane-associated in the absence of SpoIVFA, and RIP of pro-σK is inhibited (Fig. 3 a and b). The inhibition appears to result from a direct interaction between GFPΔ27BofA and H10SpoIVFB-GFP (Fig. 3d).

Our results with mutant BofA proteins provide insight into its possible mechanism of SpoIVFB inhibition. Previous mutational analyses of bofA demonstrated that the C terminus plays a critical role in BofA function or stability (30, 34). Our analysis of GFPΔ27BofA G75E in E. coli showed that the mutant protein accumulates as well as the wild-type protein (Fig. 4a), but the mutant protein was impaired in its ability to inhibit pro-σK(1–126)H6 processing (Fig. 4a) and was not found in complex with H10SpoIVFB-GFP (Fig. 4d). The correlation between loss of complex formation and loss of processing inhibition supports the idea that BofA must interact directly with SpoIVFB to inhibit its I-Clip activity. G75 is in a hydrophobic segment of BofA (amino acids 62–82) thought to be in the space between the IFM and OFM (Fig. 1) or possibly looping into the IFM (34). The latter hypothesis is supported by the existence of a proline residue at position 74, which may introduce a bend in the putative α-helix. Perhaps the negative charge introduced by the G75E change perturbs the membrane topology of BofA so that it fails to interact properly with SpoIVFB.

Also in support of the idea that BofA directly inhibits SpoIVFB, GFPΔ27BofA H57F was not found in complex with H10SpoIVFB-GFP (Fig. 4d) and was impaired in its ability to inhibit pro-σK processing (Fig. 4b). We propose that H57 coordinates zinc in the active site of SpoIVFB (Fig. 5a), preventing access of a water molecule and the pro sequence of pro-σK, which are necessary for peptide bond hydrolysis to produce σK (Fig. 5b). In this model, BofA function is analogous to that of the propeptide of matrix metalloproteases (31–33). A potential advantage of encoding the inhibitory peptide in a separate gene, as in the case of bofA, rather than in the same polypeptide, as for matrix metalloproteases, is the opportunity for separate transcriptional regulation of the protease and its inhibitor. Expression of bofA is strongly repressed by the mother cell transcription factor SpoIIID (35, 36), whereas expression of the spoIVF operon (encoding SpoIVFA and SpoIVFB) may be weakly inhibited by SpoIIID (29), but the significance of this regulation for the σK checkpoint has not yet been tested.

Fig. 5.

Model for RIP of pro-σK. (a) SpoIVFB is held inactive when H57 of BofA provides a fourth zinc ligand, in addition to H43, H47, and D137 of SpoIVFB (4, 5). This ligand provision is proposed to occur in the OFM in a complex that also includes SpoIVFA (not shown, see Fig. 1). (b) Loss of BofA, possibly brought about by cleavage of SpoIVFA by SpoIVB (26), allows zinc to activate a water molecule that hydrolyzes pro-σK, releasing σK from the OFM into the mother cell cytoplasm, where it directs transcription of many genes.

In orthologs of B. subtilis BofA found in closely related Bacillus species, H57 is conserved (Fig. 6), suggesting it also plays a crucial role in RIP of pro-σK in these spore-forming bacteria, some of which are human pathogens. The genus Clostridium also includes pathogenic spore-formers, but the mechanisms of regulating σK activation appear to be different. In contrast to the situation in B. subtilis, where BofA and SpoIVFA work together to inhibit pro-σK processing (13, 17, 20, 29, 30, 35), SpoIVFA orthologs are not found in the sequenced Clostridium genomes. Yet their SigK orthologs appear to have pro sequences, and putative metalloproteases with both the HEXXH and NPDG motifs can be found, although the latter exhibit low sequence similarity to SpoIVFB. Potential BofA orthologs are found in Clostridium perfringens, Clostridium thermocellum, and Clostridium acetobutylicum, albeit with less sequence similarity to B. subtilis BofA than for closely related Bacillus species. If the clostridia proteins are BofA homologs that inhibit SpoIVFB homologs, they must do so by a different mechanism than we have proposed for B. subtilis BofA (Fig. 5a), because H57 is not conserved in the clostridia proteins. Regulation of σK production has been shown to be achieved differently in Clostridium difficile (37). Its SigK ortholog has no pro sequence. A DNA rearrangement that excises a prophage-like insertion element in the sigK gene is a necessary step for efficient sporulation. The B. subtilis sigK gene normally undergoes a similar rearrangement (38), but substitution of an insertionless sigK gene for the normal gene does not impair sporulation (39), because RIP of pro-σK still governs the production of active σK.

How is the SpoIVFA-BofA-SpoIVFB complex activated by the SpoIVB signal from the forespore during B. subtilis sporulation (Fig. 1)? Recently, Dong and Cutting (26) showed that the SpoIVB serine peptidase can cleave SpoIVFA when the two proteins are produced in vitro. These authors speculated that cleavage of SpoIVFA would dissolve the SpoIVFA–BofA–SpoIVFB complex, permitting SpoIVFB to cleave pro-σK. However, our results show that BofA alone can interact with SpoIVFB and markedly inhibit RIP of pro-σK (Fig. 3), raising the possibility that BofA might persist in complex with SpoIVFB, inhibiting its I-Clip activity, after cleavage of SpoIVFA. This possibility could explain the previous finding that translational arrest in sporulating B. subtilis leads to a decrease in the level of full-length SpoIVFA, but processing of pro-σK is not observed (25). Perhaps when translation is blocked, mother cell proteases target SpoIVFA's N-terminal domain (Fig. 1), which may not be necessary to maintain BofA inhibition of SpoIVFB I-Clip activity. During sporulation, SpoIVB might specifically target the C-terminal domain of SpoIVFA (26), which is believed to be located in the space between the IFM and OFM (Fig. 1), where it may interact with the C-terminal domain of BofA (30, 34, 40), facilitating its inhibition of SpoIVFB.

Although questions remain about RIP of pro-σK, we have provided evidence that BofA is the primary inhibitor of SpoIVFB I-Clip activity. Other well studied I-Clips in the same family as SpoIVFB include human S2P (3) and E. coli YaeL (6, 7). These I-Clips do not appear to be regulated by an inhibitory protein. Rather, they operate in protease cascades in which their substrates must first be cleaved by a serine protease (1, 6, 7). There is no evidence to suggest that pro-σK is cleaved before cleavage by SpoIVFB. However, it is interesting that SpoIVFB may still operate within a protease cascade, with a serine protease, SpoIVB, cleaving SpoIVFA and releasing BofA-mediated inhibition of SpoIVFB I-Clip activity, if the model of Dong and Cutting (26) is correct. More examples of RIP by I-Clips in this family will need to be studied to see whether prior substrate cleavage or prior cleavage of an inhibitory complex by a serine protease, or another mechanism, is the most common regulatory strategy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank O. Resnekov, D. Rudner, and R. Losick for providing plasmids pOR267 and pdr95 and strains BDR511 and BDR88; S. Cutting for providing plasmid pET pro-σK and strain SC599; H. Prince for providing plasmid pHP6; L. Gu for art work on the figures; and R. Britton and L. Snyder for critical reading of the manuscript. This research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM43585 (to L.K.) and by the Michigan Agricultural Experiment Station.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: RIP, regulated intramembrane proteolysis; I-Clip, intramembrane-cleaving protease; OFM, outer forespore membrane; IFM, inner forespore membrane; KmR, kanamycin-resistant; ApR, ampicillin-resistant; IPTG, isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside.

References

- 1.Brown, M. S., Ye, J., Rawson, R. B. & Goldstein, J. L. (2000) Cell 100, 391-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Urban, S. & Freeman, M. (2002) Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 12, 512-518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rawson, R., Zelenski, N., Nijhawan, D., Ye, J., Sakai, J., Hasan, M., Chang, T., Brown, M. & Goldstein, J. (1997) Mol. Cell 1, 47-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rudner, D., Fawcett, P. & Losick, R. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 14765-14770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu, Y.-T. N. & Kroos, L. (2000) J. Bacteriol. 182, 3305-3309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alba, B. M., Leeds, J. A., Onufryk, C., Lu, C. Z. & Gross, C. A. (2002) Genes Dev. 16, 2156-2168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanehara, K., Ito, K. & Akiyama, Y. (2002) Genes Dev. 16, 2147-2155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Urban, S., Schlieper, D. & Freeman, M. (2002) Curr. Biol. 12, 1507-1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gallio, M., Sturgill, G., Rather, P. & Kylsten, P. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 12208-12213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.An, F. Y., Sulavik, M. C. & Clewell, D. B. (1999) J. Bacteriol. 181, 5915-5921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rather, P. N., Ding, X., Baca-DeLancey, R. R. & Siddiqui, S. (1999) J. Bacteriol. 181, 7185-7191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stragier, P. & Losick, R. (1996) Annu. Rev. Genet. 30, 297-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cutting, S., Oke, V., Driks, A., Losick, R., Lu, S. & Kroos, L. (1990) Cell 62, 239-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu, S., Halberg, R. & Kroos, L. (1990) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87, 9722-9726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang, B., Hofmeister, A. & Kroos, L. (1998) J. Bacteriol. 180, 2434-2441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu, S., Cutting, S. & Kroos, L. (1995) J. Bacteriol. 177, 1082-1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Resnekov, O. & Losick, R. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 3162-3167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Resnekov, O., Alper, S. & Losick, R. (1996) Genes Cells 1, 529-542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lewis, A. & Thomas, P. (1999) Protein Sci. 8, 439-442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rudner, D. Z. & Losick, R. (2002) Genes Dev. 16, 1007-1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cutting, S., Driks, A., Schmidt, R., Kunkel, B. & Losick, R. (1991) Genes Dev. 5, 456-466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wakeley, P. R., Dorazi, R., Hoa, N. T., Bowyer, J. R. & Cutting, S. M. (2000) Mol. Microbiol. 36, 1336-1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoa, N. T., Brannigan, J. A. & Cutting, S. M. (2002) J. Bacteriol. 184, 191-199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Resnekov, O. (1999) J. Bacteriol. 181, 5384-5388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kroos, L., Yu, Y. T., Mills, D. & Ferguson-Miller, S. (2002) J. Bacteriol. 184, 5393-5401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dong, T. C. & Cutting, S. M. (2003) Mol. Microbiol. 49, 1425-1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sambrook, J., Fritsch, E. F. & Maniatis, T. (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual (Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press, Plainview, NY), 2nd Ed.

- 28.Kroos, L., Kunkel, B. & Losick, R. (1989) Science 243, 526-529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cutting, S., Roels, S. & Losick, R. (1991) J. Mol. Biol. 221, 1237-1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ricca, E., Cutting, S. & Losick, R. (1992) J. Bacteriol. 174, 3177-3184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Springman, E., Angleton, E., Birkedal-Hansen, H. & Van Wart, H. (1990) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87, 364-368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Wart, H. E. & Birkedal-Hansen, H. (1990) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87, 5578-5582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morgunova, E., Tuuttila, A., Bergmann, U., Isupov, M., Lindqvist, Y., Schneider, G. & Tryggvason, K. (1999) Science 284, 1667-1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Varcamonti, M., Marasco, R., De Felice, M. & Sacco, M. (1997) Microbiology 143, 1053-1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ireton, K. & Grossman, A. (1992) J. Bacteriol. 174, 3185-3195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Halberg, R. & Kroos, L. (1994) J. Mol. Biol. 243, 425-436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haraldsen, J. D. & Sonenshein, A. L. (2003) Mol. Microbiol. 48, 811-821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stragier, P., Kunkel, B., Kroos, L. & Losick, R. (1989) Science 243, 507-512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kunkel, B., Losick, R. & Stragier, P. (1990) Genes Dev. 4, 525-535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Green, D. & Cutting, S. (2000) J. Bacteriol. 182, 278-285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Youngman, P., Perkins, J. B. & Losick, R. (1984) Plasmid 12, 1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.