Significance

In this study, by using molecular dynamics simulations and Markov state models, we reveal that RNA polymerase II translocation is driven purely by thermal energy and does not require the input of any additional chemical energy. Our simulations show an important role for the bridge helix: Large thermal oscillations of this structural element facilitate the translocation by specific interactions that lower the free-energy barriers between four metastable states. Among these states, we identify two previously unidentified intermediates that have not been previously captured by crystallography. The dynamic view of translocation presented in our study represents a substantial advance over the current understanding based on the static snapshots provided by X-ray structures of transcribing complexes.

Keywords: Markov state model, molecular dynamics, trigger loop

Abstract

Transcription is a central step in gene expression, in which the DNA template is processively read by RNA polymerase II (Pol II), synthesizing a complementary messenger RNA transcript. At each cycle, Pol II moves exactly one register along the DNA, a process known as translocation. Although X-ray crystal structures have greatly enhanced our understanding of the transcription process, the underlying molecular mechanisms of translocation remain unclear. Here we use sophisticated simulation techniques to observe Pol II translocation on a millisecond timescale and at atomistic resolution. We observe multiple cycles of forward and backward translocation and identify two previously unidentified intermediate states. We show that the bridge helix (BH) plays a key role accelerating the translocation of both the RNA:DNA hybrid and transition nucleotide by directly interacting with them. The conserved BH residues, Thr831 and Tyr836, mediate these interactions. To date, this study delivers the most detailed picture of the mechanism of Pol II translocation at atomic level.

The RNA polymerase is the central component of gene expression in all living organisms, transferring genetic information from DNA to RNA. In eukaryotes, the RNA polymerase II (Pol II) enzyme is responsible for transcribing DNA into messenger RNA. In the past decade, a number of X-ray crystallographic structures of Pol II have been obtained at different stages of the transcription process, providing a static picture of how this complex machine performs its function (1, 2). Transcription is a multistep process consisting of initiation, elongation, and termination, where elongation is composed of consecutive nucleotide addition cycles (NACs). In each NAC, the NTP substrate first diffuses into Pol II active site through the secondary channel (3–5) or alternatively the main channel (6). Upon correct NTP binding to the Pol II active site, the trigger loop (TL) conformation switches from an inactive open state to an active closed state (7). The closure of the active site subsequently facilitates the catalysis of the nucleotide addition reaction (7), followed by release of the pyrophosphate ion (PPi). To proceed to the next NAC, Pol II must translocate from a pretranslocation state, in which the active site is still occupied by the newly added nucleotide at 3′-RNA, to a posttranslocation state. During translocation, the template DNA and RNA must move by exactly one register, once again creating a free insertion site (i site) (1, 2, 5, 8–13).

Although static snapshots of X-ray structures of Pol II pretranslocation and posttranslocation states are valuable, the dynamics underlying the fundamental RNA polymerase translocation mechanism remain poorly understood (14). Two models of translocation have been proposed based on structural, biochemical, and genetic approaches. On one hand, for single subunit T7 RNAP, PPi release is suggested to be mechanically coupled to the opening motion of the O-helix (counterpart of TL) and subsequent translocation, referred to as the “power-stroke” model (15, 16). On the other hand, the Brownian ratchet model is proposed for translocation in multisubunit RNA polymerases (14, 17–19). In this model, the system can rapidly interconvert between the pretranslocation and posttranslocation states without the requirement of NTP hydrolysis. The motion is facilitated by thermal oscillation of the bridge helix (BH) between the straight and bent conformations; the binding of the incoming NTP will then stabilize forward translocation (14, 17–19). However, the dynamics at the atomic level and the details of the mechanism of Pol II translocation remain obscure and direct experimental approaches are limited.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations can provide dynamic information at atomic resolution and thus complement experimental approaches to elucidate the mechanisms of Pol II translocation. Indeed, previous all-atom MD simulation studies have provided valuable insights into the dynamics of Pol II (9, 20–22). However, it is important to point out that previous MD simulations are limited to a few hundred nanoseconds, at which proteins may only undergo local conformational changes such as side-chain rotations and loop motions. These MD simulations fall far short of biologically relevant timescales of Pol II translocation (tens of microseconds to millisecond or even longer) (23, 24). Directly simulating the millisecond timescale of a huge system like Pol II in explicit solvent (nearly half a million atoms) is not yet possible, even with modern specialized simulation hardware (25–27). Therefore, a major challenge for simulating Pol II translocation is to reach the biologically relevant timescale for this complex cellular machinery.

Recently, Markov state models (MSMs) built from many simulations (each as short as a few nanoseconds) have been applied to study protein folding and function at microsecond or even millisecond timescales (28–35). To overcome the timescale gap, we have seeded MD simulations along low-energy translocation pathways predicted by the Climber algorithm (36), and then we have used MD simulations to construct a MSM (Fig. S1). This strategy allows us to investigate the dynamics of the Pol II translocation at atomic resolution and millisecond timescales. Here we report the complete Pol II translocation event at atomic level. We found that Pol II can oscillate between the pretranslocation and posttranslocation states with an average timescale of tens of microseconds for each transition. Our simulation results are in general support of the Brownian ratchet mechanism, although the mechanical analogies of reciprocating and stationary pawls may not precisely describe a system driven by stochastic thermal motion such as Pol II. Instead, we see the BH playing a central role in facilitating the translocation of the RNA:DNA hybrid and that of the transition nucleotide (TN) by reducing free-energy barriers. This provides novel insights into the metastable intermediate states, the rate-limiting step, and the driving force of the Pol II translocation process, which allows us to propose a detailed mechanism for Pol II translocation.

Results

High-resolution structures of the Pol II complexes have greatly enhanced our understanding of the transcription mechanism; however, crystal structures can only capture static snapshots of the starting and ending points of translocation: pretranslocation and posttranslocation states. To investigate the detailed molecular events underlying Pol II translocation, we constructed a MSM from all-atom MD simulations (Material and Methods).

Simulations Reveal Spontaneous Millisecond Pol II Translocation.

Using our MSM, we have generated a synthetic trajectory revealing the millisecond dynamics of the large system of Pol II transcription complex in explicit solvent (∼426,000 atoms in total; Fig. S2), providing an observation of full cycles of Pol II translocation events at the atomic level. We observed that Pol II oscillates repeatedly between the pretranslocation and posttranslocation states within a millisecond in the absence of the incoming NTP (Fig. 1A). The average translocation timescale is around tens of microseconds. A movie for a 7-µs segment exhibiting a translocation event is available as Movie S1.

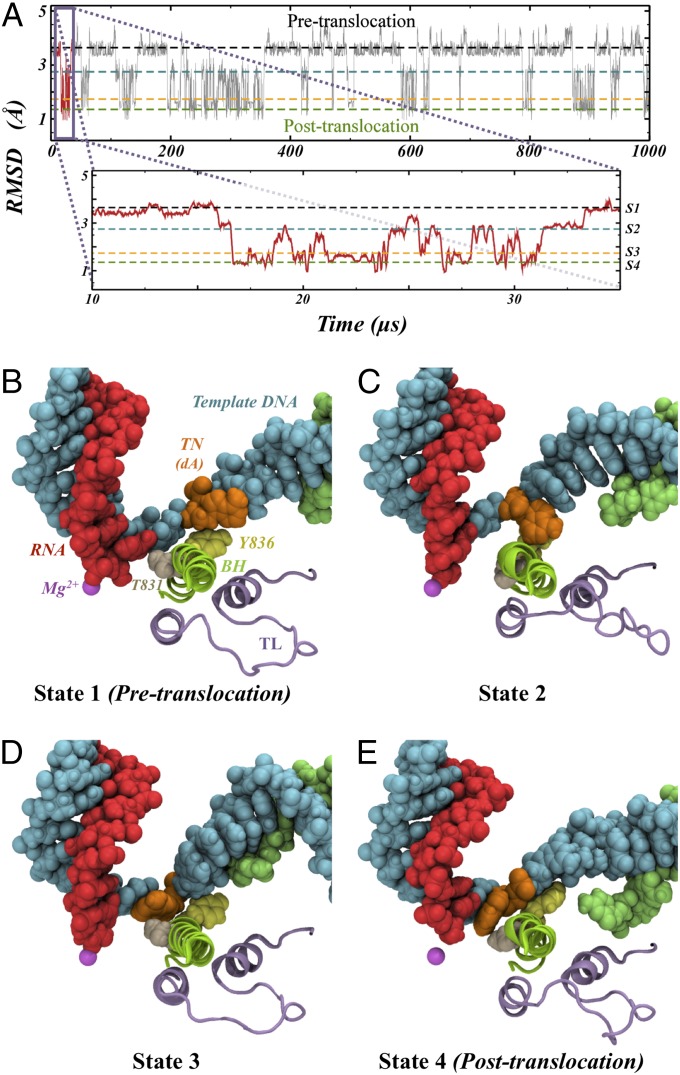

Fig. 1.

(A) RMSD of the active site with respect to the posttranslocation state as a function of time for the 1-ms MSM simulation trajectory (Materials and Methods). The segment between 10 and 35 μs is shown in the insert. The average RMSD for states 1–4 is shown by four dashed lines colored black, cyan, orange, and green for states 1–4, respectively. (B–E) Representative conformations of the metastable states identified by our model. Detailed views of the active site are shown for each of the four states identified by our model. Nucleic acids, ions, Thr831, and Tyr836 are shown in a sphere representation, whereas protein elements are shown in cartoon representation. The RNA (red), template DNA strand (cyan), BH (green), TL (purple), Mg2+ A (magenta), Rpb1 Thr831 (wheat), Rpb1 Tyr836 (yellow), and TN (orange) are shown. (B) State 1 (S1) corresponds to the pretranslocation state, analogous to the one found in X-ray crystallographic studies. (C and D) States 2 and 3 are intermediates of the translocation identified by the MSM. (E) State 4 also corresponds to the posttranslocation state found in X-ray crystallographic studies.

Four-State Asynchronous Translocation.

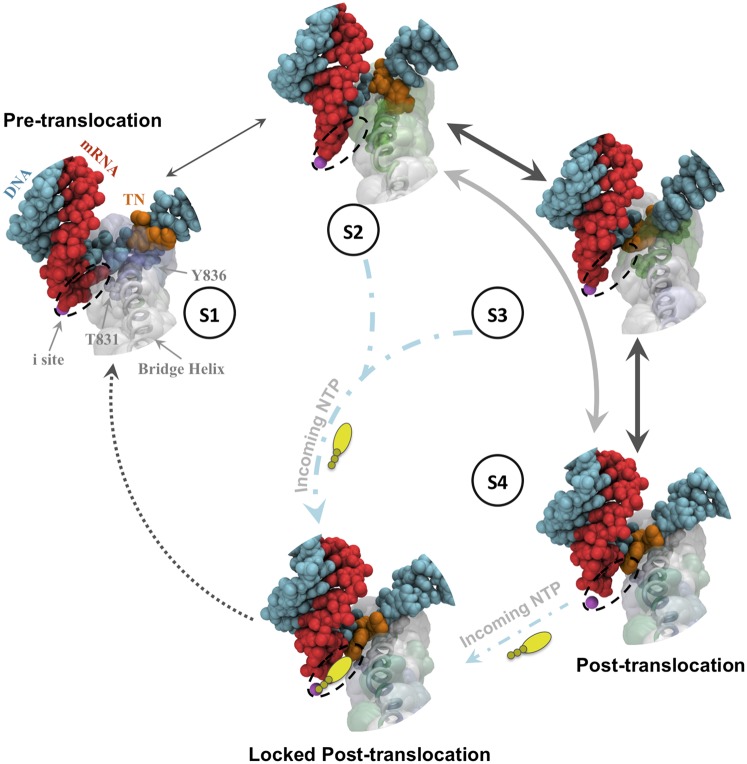

Our simulations reveal that there are four metastable states along the Pol II translocation pathway, two are already known and two are previously unidentified metastable states (structure coordinates for these two states are available in Supporting Information). In addition to pretranslocation and posttranslocation states previously captured by X-ray crystallography (states 1 and 4; Figs. 1 B and E), we identified two previously unidentified metastable intermediate states (states 2 and 3; cyan and orange dashed lines in Fig. 1 A, C, and D). In the first intermediate state (state 2, Dataset S1), the backbone of the upstream DNA and RNA has been translocated, whereas the base of the TN at the DNA i+2 position along the DNA lags behind, staying directly above the BH to form stacking interactions with the BH residue Tyr836 (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, the interaction between Thr831 and the DNA nucleotide (i+1 position) as found in state 1 is lost in state 2 due to the slight rotation of the BH. This loss of interaction in state 2 is compensated by the newly formed stacking interactions between the TN base and Tyr836, which lower the energetic barriers for translocation. In the second intermediate state (state 3, Dataset S2), the interactions between Thr831 and the DNA nucleotide are reestablished with the TN base, which has crossed the BH and reached a position only a few angstroms away from the canonical i+1 position. The position of the TN in state 3 is poised to form some initial/partial interactions with the incoming NTP, if it is available. To complete the full translocation, the TN further moves into the canonical i+1 position that allows Watson–Crick base pairing to the incoming NTP (state 4).

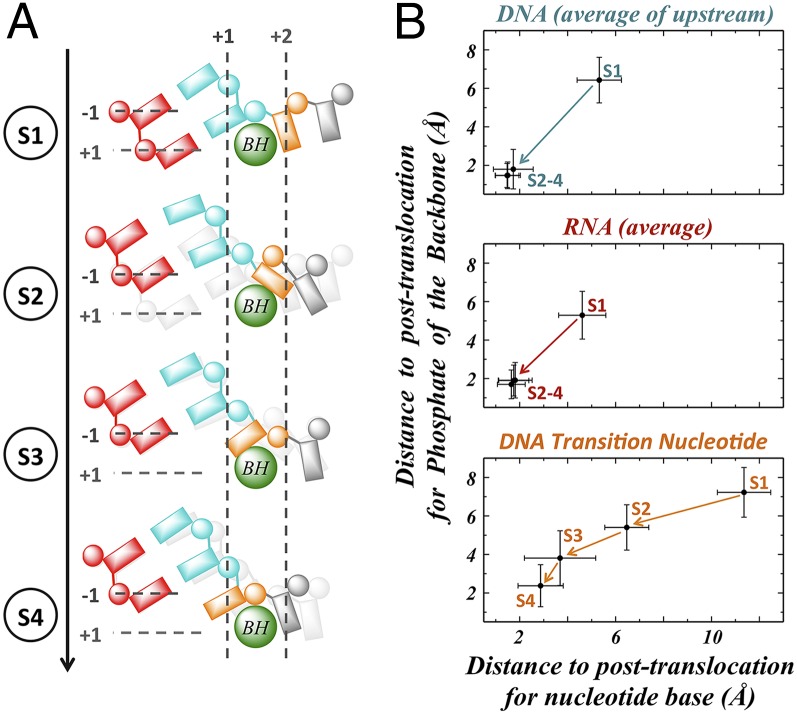

We found that the TN moves asynchronously from the rest of the upstream RNA and DNA in the hybrid region. As shown in Fig. 2A, the upstream RNA:DNA hybrid translocates simultaneously via a single-step transition from state 1 to reach their final register positions at state 2. They then remain in the same position throughout state 2 to state 4 (Fig. 2B). Accordingly, the magnesium ion (Mg2+A) also switches its binding nucleotide, from the i+1 to i−1 RNA nucleotide during the transition from state 1 to state 2 (Fig. S3A). In sharp contrast, the TN base lags behind the translocation of the upstream RNA:DNA hybrid. Specifically, the TN base translocates through a three-step mechanism. In the first step (state 1 to state 2), the TN base moves from the pretranslocation position to the top of the BH, halfway to the position of posttranslocation state, maintaining stacking with BH Tyr836 residue (Figs. 1C and 2B). Next (state 2 to state 3), the TN base crosses over the BH but is still a few angstroms away from the canonical posttranslocation state. Finally (state 3 to state 4), the transition base rotates to the canonical position of posttranslocation state, which allows full base pairing with the incoming NTP. The intermediate state’s identity is consistent with previous translocation intermediate structures trapped either by α-amanitin or DNA damage (13, 37), in which the TN base is located on top of the BH.

Fig. 2.

Translocation of the RNA:DNA hybrid is not synchronous with the translocation of TN. (A) A cartoon of the four metastable states, S1 to S4, shows the order of backbone and nucleotide translocation. From S1 to S2 the backbones of the RNA:DNA hybrid (red and cyan) translocate from pretranslocation to posttranslocation positions, whereas the TN (orange) lags behind and stacks with the BH (green). From S2 to S3 the TN crosses over the BH toward the active site but still remains stacked with the BH. From S3 to S4 the TN moves into the active site, losing the stacking with the BH and completing the translocation. (B) The plots show the distance to position in posttranslocation state for the backbone phosphate versus distance to position in the posttranslocation state for the nucleotide base. For DNA (Top) and RNA (Middle) the values are averaged over the eight upstream nucleotides of the DNA and RNA (also see Fig. S3), respectively. For the DNA TN (Bottom) there is just one phosphate and one base, so no averaging is needed.

The Thermal Oscillation of the BH Drives Translocation.

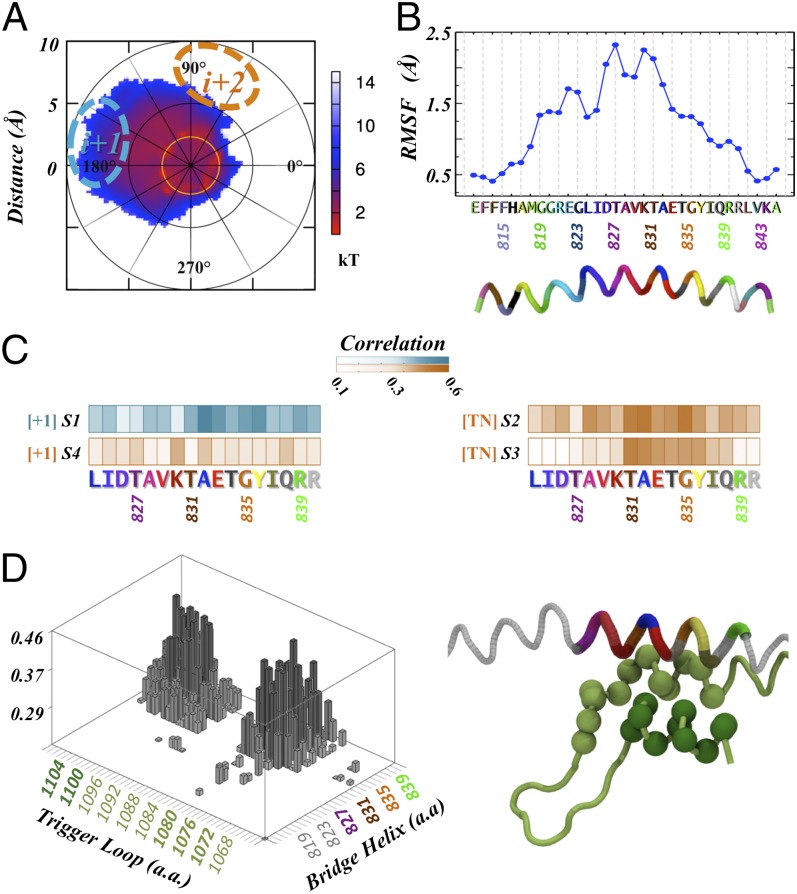

In our simulations, we observed thermal oscillation of the BH between the bent and straight conformations throughout states 1–3 (Fig. S4), whereas state 4 did not exhibit significant bending motion. This thermal bending of the BH is tightly correlated to translocation of the upstream DNA:RNA hybrid backbone (states 1–3). The bent BH occupies part of the active site interacting with the DNA nucleotide at the i+1 position and facilitating the motion of upstream template DNA to the next register (Fig. 3A and Fig. S5B). In particular, BH residues 831–836 are involved in this interaction with the DNA template. A correlation analysis confirms that the motion of this segment is highly coupled with the DNA i+1 nucleotide in state 1 (Fig. 3C). Thr831 is within this segment, consistent with the observation that Thr831 is in direct contact with the DNA i+1 nucleotide as in the pretranslocation crystal state (5). In addition, the thermal fluctuation of the BH may also help the translocation of the TN base. The TN base is stabilized by stacking interactions with Tyr836 during the transition from state 1 to state 2 (Fig. 4A). Its motion is also highly correlated with the BH residues 831–836 when the TN base crosses over the BH (states 2 and 3) (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

The dynamics of the BH and TL direct the translocation. (A) The BH motion projected along the alpha helix axis shows that the bending can be as large as 10 Å, with a preference to bend toward the upstream RNA:DNA hybrid (see Fig. S5 for details of the projection). The cyan and orange dashed ovals illustrate the i+1 and i+2 template DNA positions. (B) The RMS fluctuation values of the Cα atoms in the BH show that its maximum bending occurs in the middle of the helix. (C) In the pretranslocation state (S1) the helix can bend enough to interact with the base in the i+1 position, and the correlation plots show that indeed the movement of the helix is correlated to the displacement of the i+1 DNA position (blue). However, in both intermediates the TN motion is tightly correlated with the BH. The first intermediate (S2) centered on the residues next to the Tyr836 and the second intermediate (S3) centered with the residues surrounding the Thr831. Finally, in the posttranslocation (S4), most of the correlation is lost. (D) The graph of the cross-correlation between the TL and the BH Cα atoms (Left) shows that the motion of the TL in these segments is highly correlated to the motion of the BH.

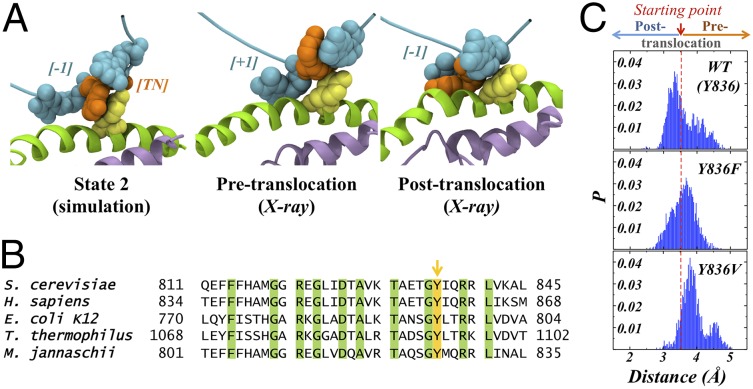

Fig. 4.

Stacking between BH residue Tyr836 and the TN base plays an important role in facilitating translocation. (A) A representative structure from state 2 shows π-stacking between Tyr836 (yellow) and the TN base (orange). Such stacking is not seen in the X-ray structures of Pol II either before (PDB ID: 1I6H) or after translocation (PDB ID: 2E2H). (B) Multiple sequence alignment across different species shows conservation of Tyr836, Thr831, and Gly835. These same residues show highly correlated motion to the BH and the TN. (C) Mutant simulations reveal that disrupting the π-stacking interaction between Tyr836 and the TN hinders forward translocation to the posttranslocation state.

We further analyzed the bending features of the BH at the residue level. We found that the direction of BH bending is toward the active site (Fig. 3A and Fig. S5B). Among all of the residues in BH, the central segment (residues 827–831; Fig. 3B) undergoes the largest bending motion (with a magnitude of ∼8 Å) (Fig. 3A). The intrinsic bending motion of the BH may be enabled by two adjacent highly flexible glycine residues (Gly819 and Gly820). This Gly–Gly pair is referred to as a “hinge,” and we found that it can transiently lose its α-helix secondary structure (Fig. S5C), consistent with previous MD simulation studies on a short timescale (21). We also examined if the BH bending is coupled with the clamp motion by computing its cross-correlation (Fig. S6). The results suggest that the translocation may not be strongly coupled to the clamp opening during the elongation phase.

Our findings are consistent with the Brownian ratchet mechanism of translocation (17) and provide atomic details for this model. The bent BH facilitates the upstream translocation of RNA:DNA hybrid. In the next step, the TN is translocated over the BH, again facilitated by interactions with the fluctuation of the BH. The translocation motion, which takes place on a timescale of tens of microseconds, is reversible until the incoming NTP stabilizes the system in the posttranslocation state.

The Motions of TL and BH Are Tightly Coupled.

Our simulations reveal that the motions of the TL and BH are tightly coupled during the translocation process. In particular, BH residues 831–836 couple with the TL through two segments: residues 1076–1082 and 1097–1103 (Fig. 3D). We observed two main conformations of the TL when the BH is bent: one involves the Leu1081 in the wedged state (37), whereas in the other, Leu1081 is not wedged (Fig. S7), indicating that the bent BH and wedged Leu1081 do not always coincide in the dynamic ensemble. An additional TL segment (1097–1103) far away from the active site may also affect the dynamics of translocation because motion of that segment is correlated to BH motion (Fig. 3C). Previous experiments show that mutations on these segments affect the in vitro elongation rate. The elongation rate is increased by the single mutations G1097D, L1101S, and E1103G, whereas the mutation N1082S decreases the elongation rate. Furthermore, the mutations Q1078 ⇨ A/E/N, L1081 ⇨ A/I/F/G, and N1082A give rise to lethal phenotypes (38, 39). We suggest that the TL may play a role in translocation by enhancing the thermal fluctuation of the BH through the highly coupled motion between these two structural motifs (6, 7, 37–39).

The Free-Energy Landscape Suggests a Single Rate Limiting Step in Translocation.

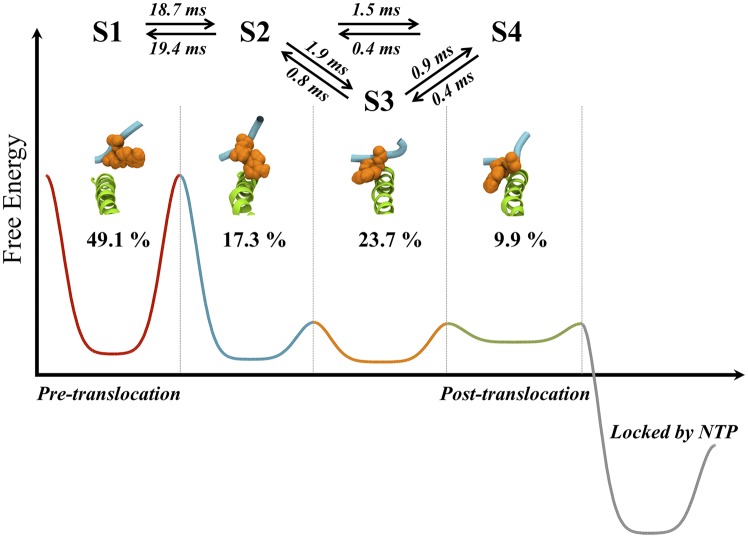

We calculated the free-energy landscape of the translocation using the MSM (Fig. 5) and identified a single high free-energy barrier separating the pretranslocation (state 1) and first intermediate (state 2) states. Therefore, this transition is the rate-limiting step of Pol II translocation and occurs on a timescale of tens of microseconds. This rate-limiting transition is characterized by the backbone translocation of the upstream RNA:DNA hybrid (Fig. 2) and a stabilizing stacking interaction between the BH residue Tyr836 and the TN (Figs. 1C and 4A). There is no significant free-energy barrier for transitions among states 2, 3, and 4, which are all located in a wide flat free-energy basin.

Fig. 5.

The schematic free-energy landscape of translocation. The pathway from the pretranslocation state S1 (red curve) to the posttranslocation state S4 (green curve) has two metastable intermediates (S2 and S3; blue and orange curves). Representative structures of the states are displayed together with their equilibrium populations and the average times (in μs) for transitioning between them. The transition from S1 to S2 is rate-limiting. All of the major pathways connecting S1 and S4 have to go through S2 (see Supporting Information for details of the pathway analysis).

A π–π stacking interaction in state 2 between the TN base and the Tyr836 side chain helps the system overcome the rate limiting free-energy barrier between states 1 and 2. This interaction can only be seen in simulations and is present in neither pretranslocation nor posttranslocation structures (Fig. 4A). Tyrosine at this position is highly conserved, which might be related to its importance in transcription (Fig. 4B). Therefore, to further examine the functional importance of this stacking interaction, we ran single mutant simulations at this position. We selected the initial conformations from around the maximum height of the free-energy barrier between states 1 and 2 (i.e., around the transition state). Theoretically, half the simulations should translocate forward, whereas the other half will translocate backward. Indeed, in the WT simulation, around half the conformations move toward the posttranslocation state. The phenylalanine mutant (Y836F) can form π–π stacking interactions with the transition base and therefore behaves similarly to the wild-type simulations. However, the valine mutant (Y836V) cannot form stacking interactions, and simulations are more likely to return to the pretranslocation state (Fig. 4C). These results are consistent with mutagenesis experiments on a related multisubunit RNAP (40), where valine mutants at this position have lower transcription activity compared with phenylalanine and WT (with tyrosine).

Discussion

We have simulated the molecular dynamics of complete Pol II translocation at atomistic resolution and millisecond timescales using MSMs. Notably, our simulations mimic the translocation process after the PPi release but before the loading of the next NTP and with the TL in an open conformation. Under these conditions, we observe a number of reversible transitions between pretranslocation and posttranslocation states within a millisecond. Our choice of the TL in an open conformation is based on recent fluorescence experimental observations (23) and computational studies (20), both suggesting that the opening of the TL is a prerequisite for full translocation.

Our results reveal that Pol II translocation is driven purely by thermal energy and does not require the input of any additional chemical energy. The thermal fluctuations of the BH between bent and straight conformations facilitate the translocation of the upstream RNA:DNA hybrid through the direct contact between the BH and i+1 base pair of the upstream RNA:DNA hybrid. This is the rate-limiting step of translocation. In the next step, the TN is translocated to become part of the RNA:DNA hybrid; this translocation is also facilitated by the thermal fluctuation of the BH that interacts with the TN. The incoming NTP serves to stabilize the system in the posttranslocation state.

In our model (Fig. 6), we did not observe any asymmetric step-wise translocation for the upstream DNA and RNA as suggested by structural studies of transcription initiation complex with short RNA:DNA hybrid (12, 41). Instead, both the nascent RNA chain and upstream DNA translocate simultaneously in our transcription elongation complex. This may reflect a different translocation mechanism between the early transcription initiation step (with an unstable short RNA:DNA hybrid) and productive elongation steps (with a stable 8–9 nt long RNA:DNA hybrid).

Fig. 6.

A model of Pol II translocation. At the pretranslocation state (S1), the oscillation of the BH is large enough to interact with the i+1 DNA nucleotide, which can then facilitate the motion of the RNA:DNA hybrid toward the posttranslocation state. At the first intermediate state (S2), the backbone of the upstream RNA:DNA hybrid has been translocated, whereas the TN still lags behind, stabilized by a stacking interaction with Tyr836. The active site is empty, which may permit entrance of the incoming NTP to the i site. At the second intermediate state (S3), the continuous oscillation of the BH further facilitates TN crossing over it, while maintaining strong interactions, mainly through residue Thr831. The position of the TN in S3 may already allow partial interaction with the incoming NTP. In the final steps, the TN moves to its final i+1 posttranslocation position (S4). The incoming NTP may then lock the system in the posttranslocation state by entering to the i site. The transparent surface surrounding the BH represents its overall displacement in each state. The BH residues that have correlated motion with the i+1 DNA nucleotide, TN, and both of them (i+1 DNA nucleotide and TN) are displayed in blue, green, and turquoise, respectively. The thickness of arrows that connect different states is proportional to the rate of the transitions between them.

We have elucidated the detailed molecular mechanism of the bending motion of the BH: unfolding of the GG segment (819–820) promotes bending of the adjacent segment (827–831), and this bending is further propagated to the DNA template through a third segment (831–836). Mutations of these residues in a related RNAP decrease the in vitro transcription rate (38), and footprinting experiments show that mutations near the GG segment that increase the bending of the BH can promote translocation (42, 43). In addition, a previous structural study revealed that Pol II inhibitor α-amanitin forms a hydrogen bond with E822 (44), likely trapping the BH in a straight conformation and hindering the bending motion of the BH. Tyr836 in the third segment facilitates the system in overcoming the largest free-energy barrier of translocation through π–π stacking interactions with the TN base. It is important to note that the time scale of the BH bending oscillation is much faster than translocation. The BH may oscillate between bent and straight conformations many times within a single translocation event. The bent BH conformation can be trapped in the elemental paused RNAP as revealed by a recent structural study (39). In our model, the motion of the TL is also coupled to the BH through two segments; one is in direct contact with the BH, whereas the other is far from the active site. Mutations in these two segments will affect dynamics of TL conformation change between open and closed conformations, the transcription rate, and fidelity (G1097D, L1101S, or E1103G) or even result in lethal phenotypes (e.g., Q1078 ⇨ A/E/N) (38). It is conceivable that future biochemical and structural studies could exploit mutations of key residues in the BH and TL, as well as modifications/damage to the template DNA strand, that alter the interactions between Pol II and DNA during the translocation. In particular, we hypothesize that mutations or modifications involving the Tyr836 may help trap the intermediate states of translocation.

Our simulations of translocation events, together with previous simulations (9, 20–22), provide important mechanistic and kinetic insights of several key steps in Pol II transcription. Our previous simulation study has suggested that the PPi release is rapid [at ∼1 μs (9)]. NTP loading has been suggested to occur in a few milliseconds (45), whereas the existence of a prebinding site may further accelerate this process. In the current study, we show that translocation can occur at timescales of tens of microseconds, which is relatively fast compared with the elongation rate (∼100 ms per base pair in vivo). However, we note that the rates obtained from our MSM may be overestimated under various scenarios, e.g., when there exist off-pathway intermediate states, which have not been sampled by the seeding MD simulations. Therefore, we suggest these rates to be treated as the upper limit of the rates for translocation. In future studies it will be interesting to simulate a full cycle of nucleotide addition, including DNA melting and annealing, NTP loading, TL closure/folding, catalysis, PPi release, and TL opening/unfolding. Additionally, it would be important to consider a model of a complete transcription bubble and other aspects known to affect the native Pol II elongation complex, such as the effect of Mg2+ and other ions. Such studies may allow us to connect structural snapshots and lead to a complete understanding of the dynamics of Pol II transcription.

Materials and Methods

Generating Initial Low-Energy Pathways of Translocation.

We first generated models of both pretranslocation and posttranslocation states based on existing crystal structures (see Supporting Information for details of model construction). We then obtained two independent pathways along the directions of forward and backward translocation. These initial pathways were produced using a modified version of the Climber algorithm (36) (see Supporting Information for details).

Seeding MD Simulations.

We performed two rounds of MD simulations. The first round of simulations was initiated from structures along the two low-energy pathways generated by the Climber algorithm, and its objective was to relax the system from these initial pathway (44 × 20 ns NPT simulations at 1 bar, 300 K or 310K). We then select 80 representative conformations from these simulations as starting points for a production round of MD simulations (80 × 20 ns NVT simulations at 310 K). The second rounds of simulations were used to build the MSM. All of the simulations were performed using the Amber03 Force Field (46) and Groningen Machine for Chemical Simulations 4.5 software (47). The Pol II complex was solvated in a water box, and counter ions were added to make the system neutral. Total system size was 426,059 atoms. Long-range electrostatic interactions were treated using the Particle-Mesh Ewald method. See Supporting Information for further details.

Constructing and Validating MSMs.

To construct MSMs, we divided all MD conformations (∼80 K) into 976 microstates using the K-centers clustering algorithm implemented in MSMBuilder package (48) (see Supporting Information for further details). The implied timescale plots displayed a plateau after a lag time of 4 ns, indicating that the model is Markovian at this or a longer lag time (Fig. S8E). This 976-state MSM has been further validated by successfully reproducing the probability curves for the system to remain in a certain microstate directly computed from the original MD simulations (Fig. S8F). Finally, we compared the initial Climber pathways against the MSM results by projecting them onto a set of common reaction coordinates using the Isomap dimensionality reduction technique (49). This analysis confirmed that the sampling from MSMs has diffused away significantly from the initial pathways, indicating that the initial pathways do not govern the final results of the MSMs (Fig. S9B). All of the quantitative properties reported in this work are computed exclusively from the 976-state MSM.

Generating Millisecond Trajectories from MSMs.

We have sampled the transition probability matrix of our MSM with a lag time of 5 ns to produce the millisecond MSM simulation trajectory.

Clustering Microstates into Four Metastable States.

To visualize the translocation mechanisms, we have clustered the microstates into four metastable states using the Perron cluster cluster analysis algorithm in the MSMBuilder package (48).

Mutant Simulations.

Using a conformation that is near to the transition state between the pretranslocation (S1) and the first-intermediate (S2) as the initial point, we generated the in silico mutants of Rpb1: Y836F and Y836V. Five 20-ns MD simulations (NVT, T = 310 K) were performed for each of the mutants and the wild-type protein.

Cross-Correlations.

To determine whether pairs of elements (e.g., a residue and a nucleotide) have concerted dynamics we have calculated the Pearson correlation coefficient of the covariance matrix.

Measurement of BH Bending.

The tips of the BH (Rpb1, residues 811–815 and 841–844) were aligned to the structure of an idealized α-helix. We then measured two reaction coordinates: (i) the distance of a vector to the center of the idealized α-helix and (ii) the angle between the previous vector and a reference vector (for convenience, we defined that in an idealized α-helix the angle of the Tyr836 is 90°).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Fu Kit Sheong for useful discussions. We acknowledge the Hong Kong Research Grant Council (Grants 661011, AoE/M-09/12, M-HKUST601/13, and T13-607/12R), National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program 2013CB834703), and National Science Foundation of China (Grant 21273188) (to X.H.); National Institute of General Medical Sciences Grant F32GM093580 and National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant U54 GM072970 (to D.R.W.); NIH Grants GM085136 and GM102362, Sidney Kimmel Foundation for Cancer Research Grant SKF-12-014, and University of California, San Diego, Startup fund (to D.W.); Hong Kong PhD Fellowship and Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Technología Fellowship 215482 (to F.P.A.); and NIH Grant GM063817 (to M.L., who is the Robert W. and Vivian K. Cahill Professor of Cancer Research). Computing resources were provided by the National Supercomputing Center in Shenzhen and Aitzaloa cluster in Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana of Mexico City.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. R.L. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

See Commentary on page 7507.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1315751111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Kornberg RD. The molecular basis of eukaryotic transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(32):12955–12961. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704138104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheung AC, Cramer P. A movie of RNA polymerase II transcription. Cell. 2012;149(7):1431–1437. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Westover KD, Bushnell DA, Kornberg RD. Structural basis of transcription: Nucleotide selection by rotation in the RNA polymerase II active center. Cell. 2004;119(4):481–489. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kettenberger H, Armache KJ, Cramer P. Complete RNA polymerase II elongation complex structure and its interactions with NTP and TFIIS. Mol Cell. 2004;16(6):955–965. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gnatt AL, Cramer P, Fu JH, Bushnell DA, Kornberg RD. Structural basis of transcription: An RNA polymerase II elongation complex at 3.3 A resolution. Science. 2001;292(5523):1876–1882. doi: 10.1126/science.1059495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burton ZF, et al. NTP-driven translocation and regulation of downstream template opening by multi-subunit RNA polymerases. Biochem Cell Biol. 2005;83(4):486–496. doi: 10.1139/o05-059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang D, Bushnell DA, Westover KD, Kaplan CD, Kornberg RD. Structural basis of transcription: Role of the trigger loop in substrate specificity and catalysis. Cell. 2006;127(5):941–954. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Svetlov V, Nudler E. Macromolecular micromovements: How RNA polymerase translocates. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2009;19(6):701–707. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Da LT, Wang D, Huang X. Dynamics of pyrophosphate ion release and its coupled trigger loop motion from closed to open state in RNA polymerase II. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134(4):2399–2406. doi: 10.1021/ja210656k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abbondanzieri EA, Greenleaf WJ, Shaevitz JW, Landick R, Block SM. Direct observation of base-pair stepping by RNA polymerase. Nature. 2005;438(7067):460–465. doi: 10.1038/nature04268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guo M, et al. Core structure of the yeast spt4-spt5 complex: A conserved module for regulation of transcription elongation. Structure. 2008;16(11):1649–1658. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu X, Bushnell DA, Silva DA, Huang X, Kornberg RD. Initiation complex structure and promoter proofreading. Science. 2011;333(6042):633–637. doi: 10.1126/science.1206629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang D, Zhu G, Huang X, Lippard SJ. X-ray structure and mechanism of RNA polymerase II stalled at an antineoplastic monofunctional platinum-DNA adduct. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(21):9584–9589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002565107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Svetlov V, Nudler E. Basic mechanism of transcription by RNA polymerase II. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1829(1):20–28. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yin YW, Steitz TA. The structural mechanism of translocation and helicase activity in T7 RNA polymerase. Cell. 2004;116(3):393–404. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00120-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu J, Oster G. A small post-translocation energy bias aids nucleotide selection in T7 RNA polymerase transcription. Biophys J. 2012;102(3):532–541. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bar-Nahum G, et al. A ratchet mechanism of transcription elongation and its control. Cell. 2005;120(2):183–193. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martinez-Rucobo FW, Cramer P. Structural basis of transcription elongation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1829(1):9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maoiléidigh DO, Tadigotla VR, Nudler E, Ruckenstein AE. A unified model of transcription elongation: What have we learned from single-molecule experiments? Biophys J. 2011;100(5):1157–1166. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.12.3734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feig M, Burton ZF. RNA polymerase II with open and closed trigger loops: active site dynamics and nucleic acid translocation. Biophys J. 2010;99(8):2577–2586. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kireeva ML, et al. Molecular dynamics and mutational analysis of the catalytic and translocation cycle of RNA polymerase. BMC Biophys. 2012;5(1):11. doi: 10.1186/2046-1682-5-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang X, et al. RNA polymerase II trigger loop residues stabilize and position the incoming nucleotide triphosphate in transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(36):15745–15750. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009898107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malinen AM, et al. Active site opening and closure control translocation of multisubunit RNA polymerase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(15):7442–7451. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dangkulwanich M, et al. Complete dissection of transcription elongation reveals slow translocation of RNA polymerase II in a linear ratchet mechanism. eLife. 2013;2:e00971. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shaw DE, et al. Anton, a special-purpose machine for molecular dynamics simulation. SIGARCH Comput. Archit. News. 2007;35(2):1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Allen F, et al. Blue Gene: a vision for protein science using a petaflop supercomputer. IBM Syst J. 2001;40(2):310–327. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larson SM, Snow CD, Shirts M, Pande VS. 2009. Folding@Home and Genome@Home: Using distributed computing to tackle previously intractable problems in computational biology. arXiv:0901.0866.

- 28.Chodera JD, Singhal N, Pande VS, Dill KA, Swope WC. Automatic discovery of metastable states for the construction of Markov models of macromolecular conformational dynamics. J Chem Phys. 2007;126(15):155101. doi: 10.1063/1.2714538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bowman GR, Beauchamp KA, Boxer G, Pande VS. Progress and challenges in the automated construction of Markov state models for full protein systems. J Chem Phys. 2009;131(12):124101. doi: 10.1063/1.3216567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Noé F, Schütte C, Vanden-Eijnden E, Reich L, Weikl TR. Constructing the equilibrium ensemble of folding pathways from short off-equilibrium simulations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(45):19011–19016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905466106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morcos F, et al. Modeling conformational ensembles of slow functional motions in Pin1-WW. PLOS Comput Biol. 2010;6(12):e1001015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1001015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Voelz VA, Bowman GR, Beauchamp K, Pande VS. Molecular simulation of ab initio protein folding for a millisecond folder NTL9(1-39) J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132(5):1526–1528. doi: 10.1021/ja9090353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bowman GR, Voelz VA, Pande VS. Atomistic folding simulations of the five-helix bundle protein λ(6−85) J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133(4):664–667. doi: 10.1021/ja106936n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bowman GR, Voelz VA, Pande VS. Taming the complexity of protein folding. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2011;21(1):4–11. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Silva DA, Bowman GR, Sosa-Peinado A, Huang X. A role for both conformational selection and induced fit in ligand binding by the LAO protein. PLOS Comput Biol. 2011;7(5):e1002054. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weiss DR, Levitt M. Can morphing methods predict intermediate structures? J Mol Biol. 2009;385(2):665–674. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.10.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brueckner F, Cramer P. Structural basis of transcription inhibition by alpha-amanitin and implications for RNA polymerase II translocation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15(8):811–818. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaplan CD, Jin H, Zhang IL, Belyanin A. Dissection of Pol II trigger loop function and Pol II activity-dependent control of start site selection in vivo. PLoS Genet. 2012;8(4):e1002627. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weixlbaumer A, Leon K, Landick R, Darst SA. Structural basis of transcriptional pausing in bacteria. Cell. 2013;152(3):431–441. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tan L, Wiesler S, Trzaska D, Carney HC, Weinzierl RO. Bridge helix and trigger loop perturbations generate superactive RNA polymerases. J Biol. 2008;7(10):40. doi: 10.1186/jbiol98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cheung AC, Sainsbury S, Cramer P. Structural basis of initial RNA polymerase II transcription. EMBO J. 2011;30(23):4755–4763. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nedialkov YA, et al. The RNA polymerase bridge helix YFI motif in catalysis, fidelity and translocation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1829(2):187–198. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nedialkov YA, Nudler E, Burton ZF. RNA polymerase stalls in a post-translocated register and can hyper-translocate. Transcription. 2012;3(5):260–269. doi: 10.4161/trns.22307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bushnell DA, Cramer P, Kornberg RD. Structural basis of transcription: alpha-amanitin-RNA polymerase II cocrystal at 2.8 A resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(3):1218–1222. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251664698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Batada NN, Westover KD, Bushnell DA, Levitt M, Kornberg RD. Diffusion of nucleoside triphosphates and role of the entry site to the RNA polymerase II active center. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(50):17361–17364. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408168101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Duan Y, et al. A point-charge force field for molecular mechanics simulations of proteins based on condensed-phase quantum mechanical calculations. J Comput Chem. 2003;24(16):1999–2012. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hess B, Kutzner C, van der Spoel D, Lindahl E. GROMACS 4: Algorithms for highly efficient, load-balanced, and scalable molecular simulation. J Chem Theory Comput. 2008;4(3):435–447. doi: 10.1021/ct700301q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bowman GR, Huang X, Pande VS. Using generalized ensemble simulations and Markov state models to identify conformational states. Methods. 2009;49(2):197–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2009.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tenenbaum JB, de Silva V, Langford JC. A global geometric framework for nonlinear dimensionality reduction. Science. 2000;290(5500):2319–2323. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5500.2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]