Significance

Tumor metastasis is the major cause of cancer lethality, whereas the underlying mechanisms are obscure. Breast cancer stem cells (CSCs) are essential for breast cancer relapse and metastasis and stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1)/chemokine (C-X-C motif) receptor 4 (CXCR4) is a key regulator of tumor dissemination. We report a large-scale quantification of SDF-1/CXCR4–induced phosphoproteome events and identify several previously unidentified phosphoproteins and signaling pathways in breast CSCs. This study provides insights into the understanding of the mechanisms of breast cancer metastasis.

Keywords: chemokine receptor, GPCR, MAPK

Abstract

Breast cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related mortality in women worldwide, with an estimated 1.7 million new cases and 522,000 deaths around the world in 2012 alone. Cancer stem cells (CSCs) are essential for tumor reoccurrence and metastasis which is the major source of cancer lethality. G protein-coupled receptor chemokine (C-X-C motif) receptor 4 (CXCR4) is critical for tumor metastasis. However, stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1)/CXCR4–mediated signaling pathways in breast CSCs are largely unknown. Using isotope reductive dimethylation and large-scale MS-based quantitative phosphoproteome analysis, we examined protein phosphorylation induced by SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling in breast CSCs. We quantified more than 11,000 phosphorylation sites in 2,500 phosphoproteins. Of these phosphosites, 87% were statistically unchanged in abundance in response to SDF-1/CXCR4 stimulation. In contrast, 545 phosphosites in 266 phosphoproteins were significantly increased, whereas 113 phosphosites in 74 phosphoproteins were significantly decreased. SDF-1/CXCR4 increases phosphorylation in 60 cell migration- and invasion-related proteins, of them 43 (>70%) phosphoproteins are unrecognized. In addition, SDF-1/CXCR4 upregulates the phosphorylation of 44 previously uncharacterized kinases, 8 phosphatases, and 1 endogenous phosphatase inhibitor. Using computational approaches, we performed system-based analyses examining SDF-1/CXCR4–mediated phosphoproteome, including construction of kinase–substrate network and feedback regulation loops downstream of SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling in breast CSCs. We identified a previously unidentified SDF-1/CXCR4-PKA-MAP2K2-ERK signaling pathway and demonstrated the feedback regulation on MEK, ERK1/2, δ-catenin, and PPP1Cα in SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling in breast CSCs. This study gives a system-wide view of phosphorylation events downstream of SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling in breast CSCs, providing a resource for the study of CSC-targeted cancer therapy.

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women, with an estimated 1.7 million new cases and 522,000 deaths around the world in 2012 alone. Tumor metastasis is the major source of cancer lethality. Cancer stem cells (CSCs) are small-percentage subpopulation within tumors, which are essential for tumor reoccurrence and metastasis (1). G protein-coupled receptor CXCR4 is critical for tumor growth and metastasis and plays important roles in CSC migration, invasion, and proliferation (2). Chemokine stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1) (CXCL-12) binds to chemokine (C-X-C motif) receptor 4 (CXCR4) and induces SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling. SDF-1 or CXCR4 knockout mice are embryonic lethal. SDF-1 and CXCR4 are vital for tumor angiogenesis and metastasis (3). The large-scale signal transduction and the feedback regulation downstream of SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling in breast CSCs are unknown but critical to understanding the cellular physiology of breast tumor regrowth and metastasis.

Protein phosphorylation and dephosphorylation are essential for cellular signal processing (4). Dynamic regulation of reversible, site-specific protein phosphorylation is critical to the signaling networks that regulate CSC self-renewal, differentiation, and metastasis. Protein-reversible phosphorylation has been extensively analyzed in examining one or a few protein phosphorylation events that affect CSC signaling (1). However, the phosphoproteome composed by protein kinase-driven and phosphatase-regulated signaling networks largely controls CSC fate. Therefore, large-scale analysis of differentially regulated protein phosphorylation is central to understanding complex cellular events, such as CSC maintenance and dissemination.

To unveil the signal transduction downstream of SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling in CSCs, in this study we have carried out isotope reductive dimethylation and large-scale liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)-based phosphoproteomic profiling and quantification in human breast CSCs upon SDF-1/CXCR4 stimulation. The phosphorylation events presented here include SDF-1/CXCR4–mediated phosphorylation sites in several key kinases and phosphatases, and several important signaling pathways in breast CSCs.

Results

Breast CSC Isolation and Identification.

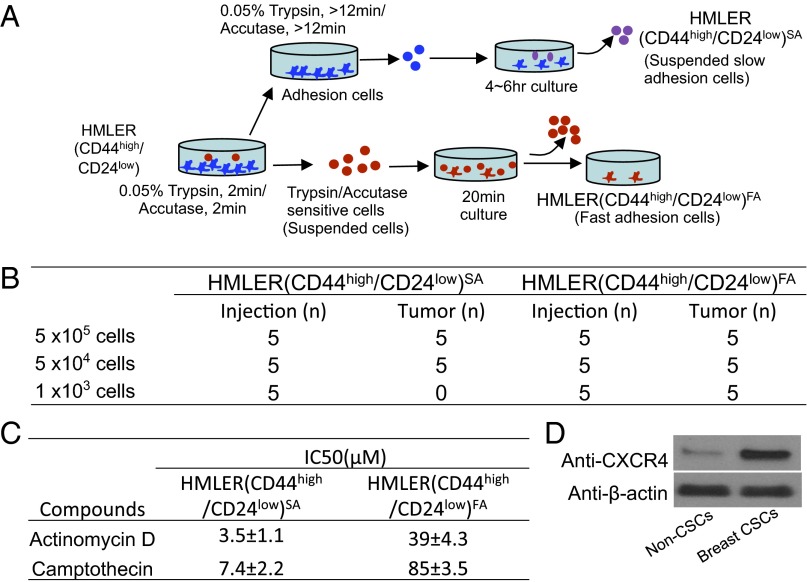

A subpopulation of human mammary epithelial (HMLER) (CD44high/CD24low) cancer cells was isolated from human mammary epithelial HMLER cancer cells by flow cytometry. A small percentage of HMLER (CD44high/CD24low)FA cells with trypsin/Accutase-sensitive and fast-adhesion characters were consequently isolated (Fig. 1A). These enriched HMLER (CD44high/CD24low)FA subpopulation cells were subsequently identified to characterize breast CSC properties with significantly increased tumorsphere growth capacity in vitro (Fig. S1), potent tumor growth capacity in mouse model in vivo (Fig. 1B), and increased drug resistance (>10-fold) compared with non-CSCs (Fig. 1C). The enriched breast CSCs, which express high levels of CXCR4, were used in this study (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

Enriched breast CSCs expresses high levels of CXCR4. (A) A small percentage of HMLER(CD44high/CD24low)FA cells with trypsin/Accutase sensitive and fast adhesion characters were isolated. (B) HMLER (CD44high/CD24low)FA cells presents potent tumor growth capacity. (C) HMLER (CD44high/CD24low)FA cells show increased drug resistance. (D) Enriched breast CSCs of HMLER (CD44high/CD24low)FA cells express high levels of CXCR4.

Phosphoproteomic Profiling and Quantification.

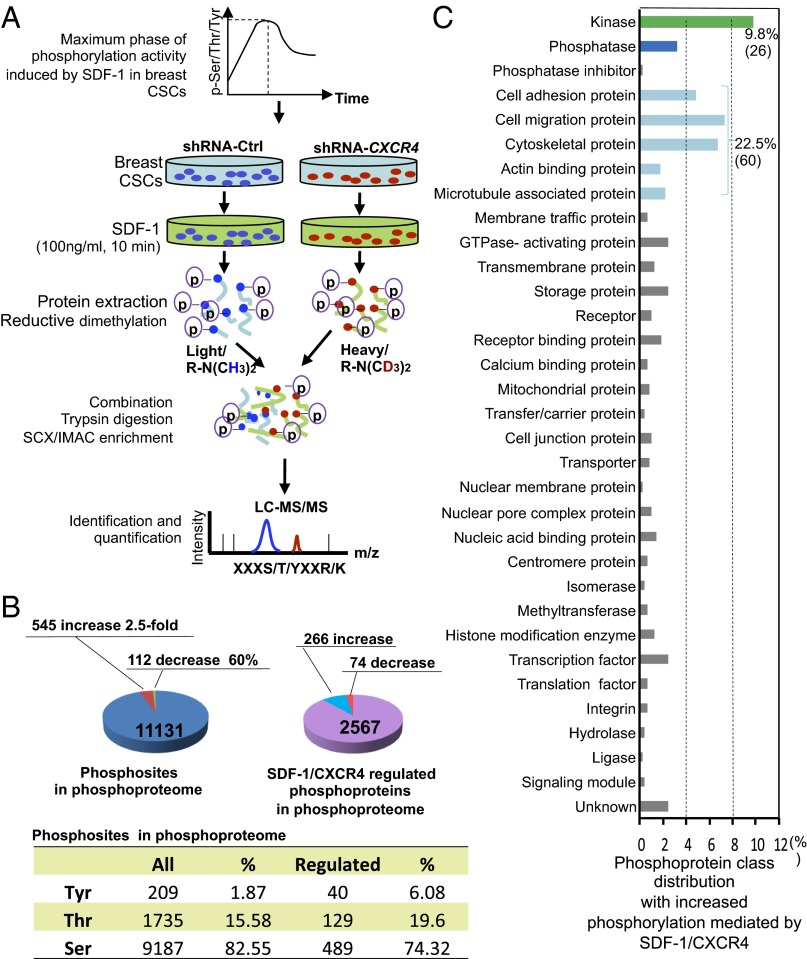

SDF-1 (100 ng/mL) induced significant phosphorylation increase of both Tyr and Ser/Thr at 10 min in these breast CSCs (Fig. S2 A and B). Previous studies reported that CXCR7 is another receptor of SDF-1 (5). To rule out the possible effects of SDF-1/CXCR7 signaling and other potential SDF-1–induced signaling, we compared phosphorylation events induced by 100 ng/mL SDF-1 for 10 min in breast CSCs with or without transient CXCR4 knocked-down (Fig. S2C) by isotope reductive dimethylation and MS-based phosphoproteomic profiling (Fig. 2A and Fig. S3). We quantified 11,131 phosphorylation sites of 2,567 phosphoproteins. Of these phosphosites, 87% were statistically unchanged in abundance in response to SDF-1/CXCR4 stimulation. In contrast, SDF-1/CXCR4 increases phosphorylation of 545 phosphosites in 266 phosphoproteins at least 2.5-fold and decreases phosphorylation of 113 phosphosites in 74 phosphoproteins (Fig. 2B). Distribution of tyrosine phosphorylation (p-Tyr) in the total phosphosites was 1.87% (Fig. 2B), which is consistent with theoretical prediction and previous observations (6). In contrast, SDF-1/CXCR4 used high percentage of p-Tyr (6.08%, Fig. 2B) in mediated phosphosites, indicating that the relatively rare p-Tyr plays important roles in SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling in breast CSCs.

Fig. 2.

Overview of analyses of SDF-1/CXCR4–induced phosphoproteome in breast CSCs. (A) Schematic of phosphoproteome analyses of the maximum phase of phosphorylation activity induced by SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling in breast CSCs. Breast CSCs with or without transient CXCR4 knockdown [transiently transduced with shRNA-CXCR4 or shRNA-control (Ctrl) plasmids] were treated with 100 ng/mL SDF-1 for 10 min. The purified phosphopeptides were performed isotope reductive dimethylation labeling and enrichment followed by LC-MS/MS analyses. (B) Pie charts show detected phosphosites, phosphoproteins, and SDF-1/CXCR4–regulated phosphoproteins and their distribution. A total of 266 phosphoproteins showed phosphorylation increase ≥2.5-fold. (C) Protein class distribution of 61.4% phosphorylation increased proteins in B. The kinases (26) occupy 9.8% and cell migration-related proteins (60) occupy 22.5%. The other total 38.6% of known proteins with increased phosphorylation and the single-item percentage less than 0.4% are not shown.

Of the classified proteins with increased phosphorylation mediated by SDF-1/CXCR4, the total percentage of proteins involved in cell adhesion, migration, cytoskeleton, actin, and microtubule association is up to 22.5% (60 of 266, Fig. 2C), perfectly matching the established critical roles of SDF-1/CXCR4 in cell migration and invasion, and tumor metastasis. Of these 60 cell mobility-related proteins, 43 proteins (>70%) have previously not been characterized as dependent on SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling. Interestingly but not unexpectedly, kinases represent the largest percentage of a single item among these classified proteins mediated by SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling (9.8% or 26 of 266, Fig. 2C). The roles of 20 unique phosphosites in PLEC1 are unknown (Fig. S4A). The remarkable phosphorylation change in GTPase activating proteins, cell junction proteins, histone modification enzymes, transporters and endogenous inhibitors suggests that SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling is implicated in many cellular activities that have previously not been recognized (Fig. 2C).

Kinases, Phosphatases, and Endogenous Phosphatase Inhibitors.

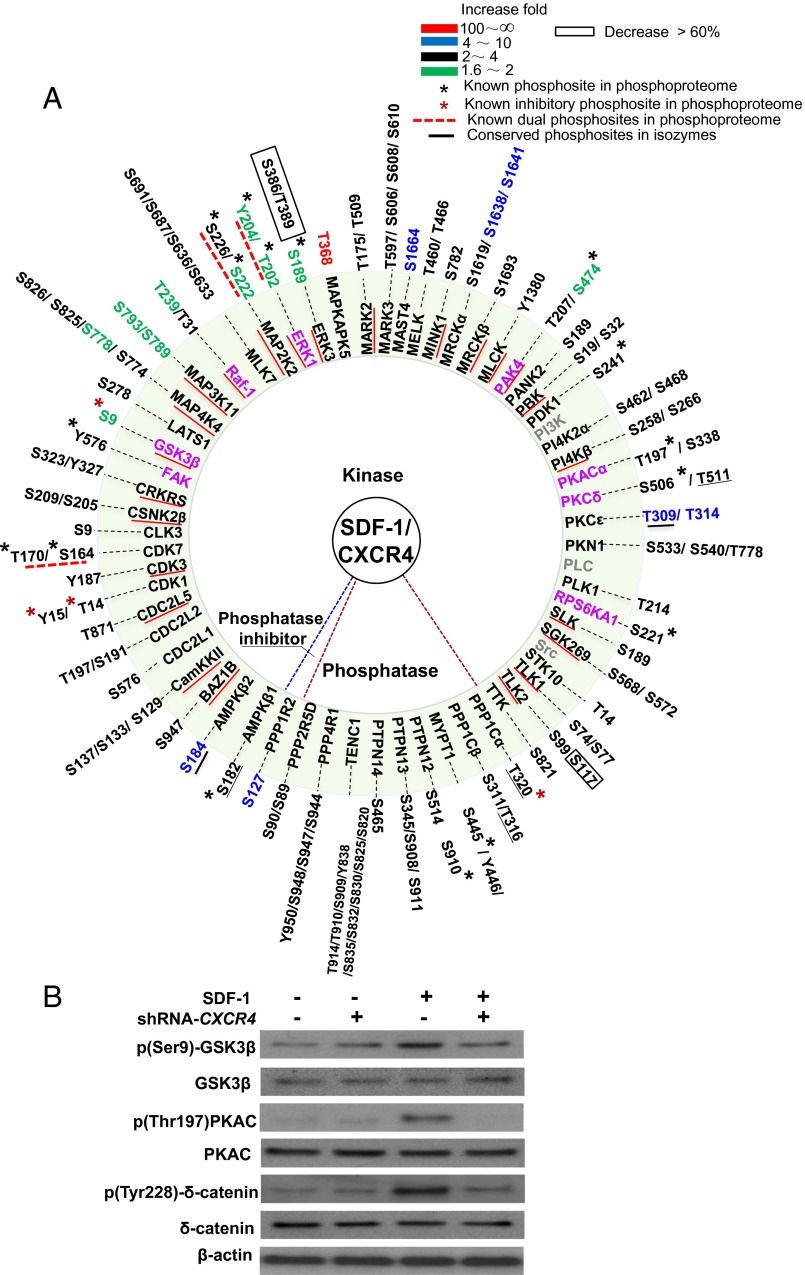

To analyze the effects of SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling, we arranged the phosphorylation affected kinases and phosphatases in a circle and color-coded them according to the phosphorylation responses (Fig. 3A). We found only 23% (14 of 60) phosphoproteins contain known phosphosites. Thus, most of the kinases and phosphatases identified here have not been previously described in SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling.

Fig. 3.

Phosphorylation in kinases, phosphatases, and phosphatase inhibitors. (A) For the proteins, the known kinases in SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling in both are in purple, known kinases in SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling not detected in this phosphoproteome are in gray, and phosphoproteins in phosphoproteome are in black. Recovered kinases (phosphorylation increase 1.6- to ∼2.5-fold) are in black with red underlining. Phosphosites with a black asterisk represent known active phosphosites in phosphoproteome. Phosphosites with a red asterisk represent known inhibitory phosphosites in this phosphoproteome. Known dual phosphosites in phosphoproteome are indicated by red dashed underlining. Conserved phosphosites in isozymes are underlined in black. The color bar in the key indicates phosphorylation increase fold. (B) Western blot analyses of SDF-1/CXCR4 regulated phosphorylation of kinases and effectors in A.

The p-Thr202 and p-Tyr204 sites of ERK1, two well-established SDF-1/CXCR4–regulated phosphosites, increased 1.6-fold in the phosphoproteome (Fig. 3A). The p-Thr185 and p-Tyr187 of ERK2 increased 1.4-fold. In Western blot analyses, we confirmed that SDF-1/CXCR4 increases phosphorylation of these two sites in ERK1/2 (Fig. S4B) under the same conditions as in the phosphoproteome analyses described here. These experimental results are consistent with the fact that activated kinases are generally more rapidly dephosphorylated by phosphatases compared with nonkinase signal effectors due to the tighter control on active kinases in cells (7, 8). We further analyzed the kinases in the phosphoproteome and found that 24 kinases showed increased phosphorylation 1.6- to ∼2.5-fold. Of them ERK1 and PAK4 are known kinases in SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling (Fig. 3A and Fig. S4B). These 24 kinases were tracked and stringently recovered. Combined with the aforementioned 26 kinases (Fig. 2C), SDF-1/CXCR4 increases phosphorylation of 50 kinases in total (Fig. 3A).

To evaluate these results, we compared the phosphorylation change of GSK3β (Ser9), PKAC (Thr197), and δ-catenin (Tyr228) in Western blot assays with/without CXCR4 transient knockdown (Fig. 3B). Indeed, we observed that SDF-1 increases phosphorylation of these sites whereas CXCR4-specific knockdown effectively neutralizes the SDF-1 induction effects. The identified set of 50 kinases contains 6 kinases established to be associated with SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling: (FAK (Tyr576), ERK1 (Thr202/Tyr204), PAK4 (Ser474), PKA (Thr197), PKC-δ (Ser506), and Rps6kA1) and six overlapped phosphosites (9).

Of the 50 kinases identified, 44 (88%) were previously unknown as dependent on SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling (Fig. 3A). Notably, 92% proteins (46 of 50) show at least twofold increase in phosphorylation at one or more sites. Of all 87 phosphosites of the kinases detected here, only 17 were already known. SDF-1/CXCR4 increased phosphorylation in eight MAPKs: MAP4K4, Raf-1, MLK7, MAP3K11, MAP2K2, ERK1, ERK3, and MAPKAPK5; and Ser222/Ser226 of MAP2K2, Thr202/ Tyr204 of ERK1, and Ser189 of ERK3 overlap.

In addition, significant phosphorylation increase is found in a number of cell migration and invasion-related kinases: FAK, MARK2, MARK3, MAST4, MELK, MYLK, MRCKα, MRCKβ, PAK4, PBK, PDK1, PKA, PKCδ, PKCε, and SLK. This consolidates the molecular basis of cell trafficking function of the SDF-1/CXCR4 axis. Up to 80% of them (12 of 15) had not been associated with SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling. A substantial phosphorylation increase in CDC2L1, CDC2L2, CDC2L5, CDC25, CDK1, CDK3, CDK7, CLK3, and TLK1 indicates the existence of alternative signaling pathways, which were not previously known to be mediated in the cell cycle regulation by SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling.

Dual phosphorylation is vital for the activities and bistability of MAPKs. The 20 kinases show statistically equal phosphorylation increase at closely spaced site pairs (Table S1). Three of them are characterized dual-phosphosite kinases and 17 kinases are previously unknown. Interestingly, SDF-1/CXCR4 decreases phosphorylation in only four kinases: ERK3 (Ser386 and Thr389), TLK2 (Ser117), MAST3 (Ser170), and STK39 (Ser387). The functions of decreased phosphorylation in these phosphosites are unknown.

Of the seven phosphatases [myosin phosphatases (MPs), PTPN12, PTPN13, PTPN14, TENC1, PPP4R1, and PPP2R5D], SDF-1/CXCR4 significantly increases phosphorylation in three components (PPP1Cα, PPP1Cβ, and MYPT1) of MPs (Fig. 3A) at seven sites (of which three sites overlap). The role of phosphorylation of Tyr446 of MYPT1 is unknown.

Overall, these data significantly extend the current knowledge of SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling-mediated phosphorylation change of kinases and phosphatases toward a system-wide view.

Phosphorylation in Protein Complexes.

Phosphorylation regulation of components in protein complexes is essential for signal effector activities, signaling regulation, and cellular processes (10). We found up to 10 established protein complexes encompassing 21 proteins present where phosphorylation increased in SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling (Fig. 4). Five protein complexes play important roles in cell motility, and an over 15-fold phosphorylation increase was found in δ-catenin, which is involved in a complex with DLG1 and critical for cell polarization, migration, and invasion (11, 12). This is consistent with the important role of SDF-1/CXCR4 in the regulation of cell trafficking. In 5 proteins of AMPKβ1, MYPT1, PKACα, PPP1Cα, and δ-catenin, 7 of 11 phosphosites match those previously described. Up to 36 phosphosites in these protein complexes have previously not been known to depend on SDF-1/CXCR-4 signaling (Fig. 4). Most of the protein complexes show a significant phosphorylation increase in multiple sites, such as δ-catenin (five sites), RBM15 (four sites), AKAP11 (three sites), and PKACα (two sites). In short, the biological functions of these 10 SDF-1/CXCR4–mediated protein complexes cover broad aspects of cellular processes, including cell migration, invasion, cell cycle, DNA repair, transcription, and signaling pathway regulation.

Fig. 4.

SDF-1/CXCR4 increases phosphorylation in the established protein complexes. SDF-1/CXCR4 significantly increases phosphorylation at catalytic subunits PPP1C (α/β) and myosin-targeting subunit MYPT1 of MP, catalytic subunit α, anchoring subunit AKAP2/11/12 of PKA, regulatory subunits β1/β2 of energy sensor AMPK, and cell invasion key factor δ-catenin. Black asterisks indicate known active phosphosites in phosphoproteome. Red asterisks indicate known inhibitory phosphosites in this phosphoproteome. Conserved phosphosites in isozymes are underlined in black. Gray circles indicate proteins that are known complex components not in the phosphoproteome.

An MAPK Network.

We examined the site-specific kinase–substrate and phosphatase–substrate of the 266 phosphoproteins with increased phosphorylation (Fig. 2B) and found 42 phosphosites of 28 phosphoproteins whose site-specific upstream kinases/phosphatases were established and detected in phosphoproteome (Table S2). SDF-1/CXCR4 mediates multiple upstream kinases of five phosphoproteins: PDK-1 and PKA for p-Thr197 of PKA (13, 14), ERK1 and GSK3β for p-Ser221 of Rps6ka1 (15, 16), ERK1/2 and GSK3β for p-Ser903 of NFκB (17), CDK1 and ERK for p-Ser56 of VIM (18), and CamKKII for p-Ser282 and Ser285 of Ets-1 (19). Both upstream kinase and phosphatase were recorded for 11 substrates (AMPKβ1, CDK7, GSK3β, ERK1, PAK4, PKA, PKCδ, Rps6ka1, PPP1Cα, Rb1, and HNRNPK) in SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling.

Pathways are fundamental components of signaling transduction. To reconstitute signaling pathways downstream of SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling, we reconstructed kinase–/phosphotase–substrate-based signaling pathways with the following three stringent approaches: (i) signal effectors showing phosphorylation increase upon SDF-1/CXCR4 stimulation in the phosphoproteome, (ii) establishing kinase/phosphotase–substrate interaction, and (iii) establishing pathways in SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling (Tables S2 and S3). Using these approaches, we were able to infer the positive or negative regulation of phosphosites detected on proteins in our study. Furthermore, the results were compared with 45 phosphoproteomic experiments of mammalian cells reported in the literature to validate the prediction for the biological function (Table S3). These pathway reconstitution approaches lead to a construction of a SDF-1/CXCR4–mediated MAPK signaling network (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

An MAPK network downstream of SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling in breast CSCs. The SDF-1/CXCR4–induced MAPK subnetwork shows reconstructed nested pathways with a five-tiered MAPK cascade and known dual phosphosites in MAP2K2 and ERK1. Black arrows show the known phosphorylation relationship in SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling in both. Purple arrows indicate the experimentally confirmed pathway in this study. Blue arrows indicate the known direct interaction and phosphorylation relationship in both. Green arrows represent the indirect phosphorylation relationship in the phosphoproteome. Pink arrows indicate biological function regulation. Red lines indicate dephosphorylation or inhibition. The green circle is the predicted functional complex (specific sites of the components are shown in Fig. 3). The light green MAPK cascade shows the five-tiered MAPK cascade in phosphoproteome.

Feedback Regulation on MEK, ERK, δ-Catenin, and PPP1Cα.

To evaluate the feedback regulation, we examined the phosphosites of p(Ser217/Ser221) MEK1/2, p(Thr202/Tyr204)-ERK, and p(Tyr228)-δ-catenin and confirmed the feedback regulation of site-specific phosphorylation (Fig. 6A). SDF-1 significantly increases phosphorylation of p(Ser228)-MEK2, p(Thr202/Tyr204)-ERK, and p(Tyr228)-δ-catenin, and the phosphorylation at these sites decreased over longer time. To evaluate the reconstructed nested phosphate regulation loops (Fig. S5), we examined the p-Thr320 of PPP1Cα in SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling. We detected that phosphorylation of Thr320 increased upon SDF-1 stimulation and subsequently reversed over time (Fig. 6B). In addition, CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100 inhibits the SDF-1–induced phosphorylation increase of p-Thr320 in PPP1Cα (Fig. 6C), indicating that p-Thr320 of PPP1Cα is dephosphorylated by nested phosphatase regulation loops downstream of CXCR4 signaling. Taken together, these data experimentally confirmed the dephosphorylation feedback regulation of kinases of MEK and ERK, signal effector of δ-catenin, and phosphatase of PPP1Cα in SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling.

Fig. 6.

Dephosphorylation feedback regulation on MEK1/2, ERK1/2, δ-catenin, and PPP1Cα. (A) Western blot assay of SDF-1 (100 ng/mL) induced phosphorylation turnover of p(Ser217/Ser221)MEK1/2, p(Tyr228)-δ-catenin, and dual phosphosites in p(Thr202/Tyr204)-ERK1/2 over longer time periods in breast CSCs. The relative phosphorylation ratios compared with control are shown. (B) Western blot assays of p(Thr320)-PPP1Cα phosphorylation homeostasis in breast CSCs over time (100 ng/mL SDF-1 treatment). (C) CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100 inhibits SDF-1/CXCR4–induced phosphorylation increase of p(Thr320)-PPP1Cα in breast CSCs. Breast CSCs were pretreated with 30 μg/mL AMD3100 for 1 h followed by with/without 100 ng/mL SDF-1 treatment for 20 min.

SDF-1/CXCR4-PKA-MAP2K2-ERK Pathway.

To further evaluate the reconstructed SDF-1/CXCR4–mediated MAPK-signaling network, we examined the SDF-1-CXCR4-PKA-MAP2K2-ERK pathway. In Western blot assays, we observed that SDF-1 treatment increased p(Thr197)-PKA, p(Ser222)-MAP2K2, and p(Thr202/Tyr204)-ERK1 whereas CXCR4 knockdown or CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100 neutralized these effects (Figs. 3B and 7A and Fig. S4B), indicating that SDF-1/CXCR4 mediates PKA, MAP2K2, and ERK1 signaling. Furthermore, we examined the PKA-MAPK cascade with PKA inhibitor 14-22-Amide and identified that SDF-1/CXCR4 regulates the PKA-MAP2K2-ERK pathway (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

SDF-1/CXCR4-PKA-MAP2K2-ERK pathway in breast CSCs. (A) CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100 inhibits SDF-1/CXCR4–induced phosphorylation increase of p(Thr197)-PKA, p(Ser217/Ser221)MEK1/2, and p(Thr202/Thy204)-ERK1/2 in breast CSCs. (B) PKA inhibitor 14-22-Amide inhibits SDF-1/CXCR4–induced phosphorylation of p(Ser217/Ser221)MEK1/2, and p(Thr202/Thy204)-ERK1/2 in breast CSCs. The breast CSCs cultured in MEBM for overnight were pretreated with 30 μg/mL AMD3100 or 6 µg/mL 14-22-Amide for 1 h followed by with/without SDF-1 (100 ng/mL) treatment for 10 min.

Discussion

Here we present the quantification and profiling of a large-scale phosphoproteome event in breast CSCs. We quantified 11,131 phosphosites in 2,567 phosphoproteins and found that SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling increases phosphorylation of 545 phosphosites in 266 phosphoproteins and decreases phosphorylation of 113 phosphosites in 74 phosphoproteins in breast CSCs. SDF-1/CXCR4 mediates 50 kinases, 8 phosphatases, and 1 phosphatase inhibitor in breast CSCs. Using a computational approach, we constructed a SDF-1/CXCR4–induced signaling network, including MAPK cascade and its feedback regulation. We identified a previously uncharacterized signaling pathway of SDF-1/CXCR4-PKA-MAP2K2-ERK, and demonstrated the dephosphorylation feedback regulation on kinases of MEK and ERK1/2, phosphatase of PPP1Cα, and the signal effector of δ-catenin. This study extends our understanding of SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling in breast CSCs to a system-wide view.

Phosphorylation in both Core Phosphosites and Noncore Phosphosites in Kinases and Phosphatases.

Recent studies report that core phosphosites, which are implicated in fundamental cellular processes, are positionally conserved in eukaryotes, whereas noncore phosphosites evolved rapidly (20). To evaluate the SDF-1/CXCR4–regulated phosphosites in evolution, we analyzed them across six eukaryotic species of human, mouse, Arabidopsis, Drosphila, Caenorhabditis elegans and yeast. We found that the regulated phosphosites of AMPK, CDC2L5, CDK1, CDK7, MAP2K2, ERK1, ERK3, PAK4, PDK1, PKA, Rps6ka1, and MP in phosphoproteome are highly conserved in all species of human, mouse, Arabidopsis, Drosphila, C. elegans, and yeast. Our observations are consistent with previous reports and find 29 additional cases (Tables S4 and S5 and Fig. 3A). Interestingly, we found that phosphorylation significantly increased at Thr511 of PKCδ and Thr309 of PKCε, which are homologous residues in the Thr-Pro (T-P) motif in a conserved TFCCGTP region in all 13 human PKC isozymes (Table S6). The conservation of regulated phosphosites (57%; 16 of 28) across species over 600 My in evolution suggests that these functional phosphosites have been ancient, strong selection constraints. These results and many other noncore phosphosites regulated by SDF-1/CXCR4 demonstrate that SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling employs both core phosphosites and noncore phosphosites in breast CSCs.

In addition, we found 190 of 545 phosphosites are in Ser/Thr-Pro (S/T-P) motifs in phosphoproteome, indicating that S/T-P turn motifs are broadly and frequently used and are essential for dynamic signaling transduction.

Both Inhibitory Phosphosites and Dephosphorylation Feedback Regulation.

Previous studies reported that MP dephosphorylates p-Ser/Thr in MAP2K2, ERK1, ERK2, and ERK3 (21). Tyrosine-specific phosphatase PTPN12/13/14 dephosphorylate p-Tyr of ERK1/2, FAK, and δ-catenin (22, 23). The endogenous phosphatase inhibitor PPP1R2 (namely I-2) negatively regulates MP by attenuating the catalytic activities PPP1Cα (24). We found that SDF-1/CXCR4 elevates phosphorylation in multiple phosphosites in MP, PTPN12, PTPN13, and PTPN14. In addition, we verified phosphorylation reverses over time in MEK2, ERK1/2, δ-catenin, and PPP1Cα in Western blot assays, which is in agreement with the reversed phosphorylation of total p-Tyr and p-Ser/Thr over time in Fig. S2, suggesting that the feedback regulation mechanism dynamically mediates signaling transduction in both a site-specific and phosphoproteome-wide format. We detected that SDF-1/CXCR4 increases phosphorylation in multiple inhibitory phosphosites: Tyr15/Thr14 in CDK1 and Ser9 in GSK3β. These results suggest that SDF-1/CXCR4 not only activates multiple signaling pathways, but also induces feedback regulation via both inhibitory phosphosites and dephosphorylation to mediate the signaling homeostasis.

SDF-1/CXCR4 Mediates Multiple MAPK Cascades in Breast CSCs.

The three-tiered kinase cascade of MAP3K-MAP2K-MAPK is ubiquitous in all eukaryotes and has an extremely wide range of functions in signal transduction (25). Increased phosphorylation at two or more sites in MAP3Ks (MAP3K11, Raf-1, and MLK7), two serine residues in MAP2Ks (Ser222 and Ser226 in MAP2K2), and conserved dual residues in MAPK (Thr202 and Tyr204 in ERK1) suggests that this three-tiered MAPK cascade may present multiple roles of switch, amplification, and feedback controller in SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling. The multiple MAP4K-MAP3K-MAP2K-MAPK-MAPKAPK five-tiered MAPK cascades presented here significantly extends the knowledge of SDF-1/CXCR4–mediated MPAK signaling.

In the graded pathway of SDF-1/CXCR4-PKCε-Raf-1-MAP2K2-ERK3-MAPKAPK5 (26), phosphorylation of Thr368 of MAPKAPK5 increases 134-fold, which is consistent with the amplification effects of the MAPK cascade. The overexpressed H-Ras in HMLER (CD44high/CD24low) cells (27) may enhance the effects of Ras-mediated Raf-1-MAPK signaling, which may help to track SDF-1/CXCR4–regulated Raf-1-MAPK signaling pathways. MAP2K2 fills the gap of previously fragmentary or unknown SDF-1/CXCR4–induced ordered MAPK pathways and shows more complete pathways with highly overlapped phosphosites.

Both G Protein-Dependent and -Independent Signaling.

Classical G protein-dependent ERK activation is rapid and transient because it is quickly quenched by the β-arrestin–mediated desensitization of the receptor. The β-arrestins scaffold the MAP kinase signaling molecules of MAP3K (Raf1), MAP2K (MEK1), and MAPK (ERK), leading to ERK1/2 phosphorylation and activation (28). The β-arrestin-mediated ERK responses are slower and more persistent. We found SDF-1/CXCR4 increases phosphorylation of ERK1/2 at 1 h (Fig. 6A), suggesting that β-arrestin–mediated ERK phosphorylation plays a role in SDF-1/CXCR4–induced persistent MPAK signaling activation. These results and many other G protein-dependent signaling events (Fig. 5 and Fig. S6) indicate that SDF-1/CXCR4 induces both G protein-dependent and -independent signaling in breast CSCs.

Phosphorylation in Multiple Sites in Protein Complex Components.

A number of activated sites are located in multiple anchoring and scaffolding proteins AKAP2, AKAP11, and AKAP12, indicating that AKAP compartmentalization of PKA signaling pathways is widely used in various cellular processes, which is in agreement with established knowledge that AKAPs mediate PKA to appropriate substrate selection and pathway integration selection (29). Multisite covalent modification is omnipresent in components of these complexes, indicating that phosphorylation regulation in diverse distinct sites may be important (i) for compartmentalization/decomposition of functional complexes, (ii) for various functions in distinct signaling pathways, and (iii) acting as a node of pathway cross-talk or a switch of activation or inactivation of regulation loops.

Phosphorylation of Cell Communication Regulators.

Recent studies reported that CSC communication with other cells in CSC niches is important for CSC relocation, self-renewal, proliferation, and differentiation (10). SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling significantly increases phosphorylation in gap junction alpha-1 protein (GJA1; Ser279 and Ser282), sodium-coupled neutral amino acid transporter-2 (SLC38A2; Ser10, Ser12, Ser18, Ser21, and Ser22), and sodium-dependent phosphate transporter-1 (SLC20A1; Ser417 and Tyr-418), which are important for cell communication. These data may provide novel hints to explore the potential roles of SDF-1/CXCR4 in cell communication.

An SDF-1/CXCR4 Signaling Network in Breast CSCs.

Signals that are transmitted inside cells do not unidirectionally amplify through signaling pipelines, but rather are tightly orchestrated through highly interconnected networks by multilayered feedback regulation mechanisms. The characterization of the SDF-1/CXCR4–mediated phosphoproteome and experimental evaluation assays offer a system-wide view of the phosphorylation signature of a key phase of the feedback signaling network downstream of CXCR4 signaling. Furthermore, it provides an opportunity to connect SDF-1/CXCR4–mediated kinases, phosphatase, phosphatase inhibitors, and other phosphoproteins, and effectors that have been reported. By integrating these phosphoproteins with phosphorylation increase in the phosphoproteome and the known factors in SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling (Tables S2, S3, and S7), we constructed an SDF-1/CXCR4–mediated signaling network in Fig. S6. Thus, SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling may be implicated in a broad range of biological procedures including cell adhesion, migration, invasion, chemotaxis, cell cycle, proliferation, apoptosis, angiogenesis, and cell communication.

Phosphoproteomic Profiling in CSCs.

Understanding how breast CSCs tightly orchestrate signal transduction in response to extra- and intracellular stimuli defines a fundamental biological issue. Essential insights into this come from the definition of system-wide signaling network architectures, such as the large-scale SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling network in breast CSC presented here. A very recent study also used an LC/-MS/MS–based approach to examine phosphorylation events downstream of SDF-1/CXCR4 in chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells (30). O’Hayre et al. used a Ni–nitrilotriacetic acid resin phosphoprotein enrichment approach and performed analyses with/without SDF-1 stimulation (30). The PHOS-select iron affinity beads and the strong cation exchange/immobilized metal affinity chromatography (SCX/IMAC) methods used in this study significantly increased phosphopeptide enrichment (∼10-fold). Reductive dimethylation of proteins of wild-type (with CH3) and CXCR4 knockdown (with CD3) breast CSCs and SDF-1 treatment of both cells significantly increased the specificity of SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling. In their study, O’Hayre et al. (30) identified Raf1 and PDK1 as important signals downstream of SDF-1/CXCR4, which was confirmed in our study. However, we have constructed a much broader and more specific signaling network downstream of SDF-1/CXCR4 in breast CSCs. Our study evidenced that phosphoproteomic profiling is a powerful tool for the understanding of CSC signaling networks system-wide in complex tumor evolution procedures, such as tumorangiogenesis and tumor metastasis.

Materials and Methods

Cell Cytometry.

The HMLER cell line was kindly provided by Robert Weinberg (Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research, Boston). HMLER (CD44high/CD24low) subpopulation cells were isolated from HMLER cells by flow cytometry using FITC-conjugated anti-CD44 (G44-26; Biosciences) antibody and PE-conjugated anti-CD24 (ML15; Biosciences) antibody. Cell cultures of mammary epithelial cell growth medium (MEGM) were ordered from Lonza.

Animals.

HMLER (CD44high/CD24low)SA and HMLER (CD44high/CD24low)FA cells were injected into mammary glands of 1.5-mo-old, nonobese diabetic SCID female mice (five mice for each group; Jackson Laboratories) for the dilution tumor formation assays, which was approved by the Harvard Medical Area Standing Committee on Animals.

Cell Lysis, Protein Extraction, Reductive Dimethylation, Combination, and Digestion.

Five CXCR4 specific short hairpin RNA (shRNA) constructs (The RNAi Consortium, Broad Institute, Boston) were tested for their ability to knock down CXCR4 expression by transfection with Lipofectamine Transfection 2000 reagents (Invitrogen). Thirty-six hours after transfection (with MEGM; Lonza), cells were cultured overnight in mammary epithelial cell basal medium (MEBM) medium (Lonza) without growth factor additives. Before analysis, the cells were treated with 100 ng/mL SDF-1 for 10 min [37 °C, 5%(vol/vol) CO2]. HMLER (CD44high/CD24low)FA were cultured in MEBM without serum overnight before SDF-1 treatment. Cells were lysed via standard methods (21) and proteins were extracted. Reductive dimethylation of intact proteins were performed with NaCNBH3(light, L) or NaCNBD3(heavy, H) as previously described (31, 32). Light- and heavy-labeled proteins were combined and purified, followed by trypsin digestion via a standard protocol (31).

Details are provided in SI Materials and Methods for SCX/IMAC phosphopeptide enrichment, LC-MS/MS analyses, phosphosite assignment, quantification analysis, bioinformatic analysis, and Western blot assay.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Robert Weinberg of Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research of Massachusetts Institute of Technology for the HMLER cell lines. This work was supported by funding from National Institutes of Health Grant CA068262 (to G.W.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data deposition: The five Excel files (Files S1–S5) and MS raw data have been deposited at http://gwagner.med.harvard.edu/intranet/PNAS_Manuscript_2014/.

See Commentary on page 7503.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1404943111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Al-Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hernandez A, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(7):3983–3988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0530291100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Müller A, et al. Involvement of chemokine receptors in breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2001;410(6824):50–56. doi: 10.1038/35065016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tachibana K, et al. The chemokine receptor CXCR4 is essential for vascularization of the gastrointestinal tract. Nature. 1998;393(6685):591–594. doi: 10.1038/31261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Linding R, et al. Systematic discovery of in vivo phosphorylation networks. Cell. 2007;129(7):1415–1426. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balabanian K, et al. The chemokine SDF-1/CXCL12 binds to and signals through the orphan receptor RDC1 in T lymphocytes. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(42):35760–35766. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508234200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olsen JV, et al. Global, in vivo, and site-specific phosphorylation dynamics in signaling networks. Cell. 2006;127(3):635–648. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aoki K, Yamada M, Kunida K, Yasuda S, Matsuda M. Processive phosphorylation of ERK MAP kinase in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(31):12675–12680. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104030108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alessi DR, et al. Identification of the sites in MAP kinase kinase-1 phosphorylated by p74raf-1. EMBO J. 1994;13(7):1610–1619. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06424.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Teicher BA, Fricker SP. CXCL12 (SDF-1)/CXCR4 pathway in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(11):2927–2931. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Good MC, Zalatan JG, Lim WA. Scaffold proteins: Hubs for controlling the flow of cellular information. Science. 2011;332(6030):680–686. doi: 10.1126/science.1198701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wildenberg GA, et al. p120-catenin and p190RhoGAP regulate cell-cell adhesion by coordinating antagonism between Rac and Rho. Cell. 2006;127(5):1027–1039. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alemà S, Salvatore AM. p120 catenin and phosphorylation: Mechanisms and traits of an unresolved issue. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1773(1):47–58. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tang Y, McLeod M. In vivo activation of protein kinase A in Schizosaccharomyces pombe requires threonine phosphorylation at its activation loop and is dependent on PDK1. Genetics. 2004;168(4):1843–1853. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.032466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cauthron RD, Carter KB, Liauw S, Steinberg RA. Physiological phosphorylation of protein kinase A at Thr-197 is by a protein kinase A kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18(3):1416–1423. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.3.1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao Y, Bjorbaek C, Moller DE. Regulation and interaction of pp90(rsk) isoforms with mitogen-activated protein kinases. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(47):29773–29779. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.47.29773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paweletz CP, et al. Identification of direct target engagement biomarkers for kinase-targeted therapeutics. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(10):e26459. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Demarchi F, Bertoli C, Sandy P, Schneider C. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta regulates NF-kappa B1/p105 stability. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(41):39583–39590. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305676200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsujimura K, et al. Visualization and function of vimentin phosphorylation by cdc2 kinase during mitosis. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(49):31097–31106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu H, Grundström T. Calcium regulation of GM-CSF by calmodulin-dependent kinase II phosphorylation of Ets1. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13(12):4497–4507. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-03-0149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tan CS, et al. Comparative analysis reveals conserved protein phosphorylation networks implicated in multiple diseases. Sci Signal. 2009;2(81):ra39. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grassie ME, Moffat LD, Walsh MP, MacDonald JA. The myosin phosphatase targeting protein (MYPT) family: A regulated mechanism for achieving substrate specificity of the catalytic subunit of protein phosphatase type 1δ. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2011;510(2):147–159. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2011.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zheng Y, et al. FAK phosphorylation by ERK primes ras-induced tyrosine dephosphorylation of FAK mediated by PIN1 and PTP-PEST. Mol Cell. 2009;35(1):11–25. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoover AC, et al. Impaired PTPN13 phosphatase activity in spontaneous or HPV-induced squamous cell carcinomas potentiates oncogene signaling through the MAP kinase pathway. Oncogene. 2009;28(45):3960–3970. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li M, Satinover DL, Brautigan DL. Phosphorylation and functions of inhibitor-2 family of proteins. Biochemistry. 2007;46(9):2380–2389. doi: 10.1021/bi602369m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Plotnikov A, Zehorai E, Procaccia S, Seger R. The MAPK cascades: Signaling components, nuclear roles and mechanisms of nuclear translocation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813(9):1619–1633. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seternes OM, et al. Activation of MK5/PRAK by the atypical MAP kinase ERK3 defines a novel signal transduction pathway. EMBO J. 2004;23(24):4780–4791. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gupta PB, et al. Identification of selective inhibitors of cancer stem cells by high-throughput screening. Cell. 2009;138(4):645–659. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DeWire SM, Ahn S, Lefkowitz RJ, Shenoy SK. Beta-arrestins and cell signaling. Annu Rev Physiol. 2007;69:483–510. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.69.022405.154749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wong W, Scott JD. AKAP signalling complexes: Focal points in space and time. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5(12):959–970. doi: 10.1038/nrm1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Hayre M, et al. Elucidating the CXCL12/CXCR4 signaling network in chronic lymphocytic leukemia through phosphoproteomics analysis. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(7):e11716. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Villén J, Gygi SP. The SCX/IMAC enrichment approach for global phosphorylation analysis by mass spectrometry. Nat Protoc. 2008;3(10):1630–1638. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.She YM, Rosu-Myles M, Walrond L, Cyr TD. Quantification of protein isoforms in mesenchymal stem cells by reductive dimethylation of lysines in intact proteins. Proteomics. 2012;12(3):369–379. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201100308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.