Abstract

Although the rate of development of drug resistance remains very high, 5-fluorouracil (5-Fu) is still the most common chemotherapeutic drug used for the treatment of colon cancer. A better understanding of the mechanism of why cancers develop resistance to 5-Fu could improve its therapeutic effect. Sometimes, antioxidants are used simultaneously with 5-Fu treatment. However, a recent clinical trial showed no advantage or even a harmful effect of combining antioxidants with 5-Fu compared with administration of 5-Fu alone. The mechanism explaining this phenomenon is still poorly understood. In this study, we show that 5-Fu can induce reactive oxygen species-dependent Src activation in colon cancer cells. Mouse embryonic fibroblasts that are deficient in Src showed a clear resistance to 5-Fu, and knocking down Src protein expression in colon cancer cells also decreased 5-Fu-induced apoptosis. We found that Src could interact with and phosphorylate caspase-7 at multiple tyrosine sites. Functionally, the tyrosine phosphorylation of caspase-7 increases its activity, thereby enhancing cellular apoptosis. When using 5-Fu and antioxidants together, Src activation was blocked, resulting in decreased 5-Fu-induced apoptosis. Our results provide a novel explanation as to why 5-Fu is not effective in combination with some antioxidants in colon cancer patients, which is important for clinical chemotherapy.

Keywords: antioxidant, 5-Fu, Src, caspase-7, colon cancer, apoptosis

Colon cancer remains a major threat to human life. In 2012, 103 170 new cases of colon cancer were diagnosed and 51 690 deaths occurred from colorectal cancer in the United States.1 Although the rate of drug resistance remains very high, 5-fluorouracil (5-Fu) is still the most common and widely used chemotherapeutic drug for the treatment of colon cancer. A better understanding of the mechanism of the development of resistance to 5-Fu could improve its therapeutic effect.

Antioxidants are widely used as dietary supplements and have been investigated for their effectiveness in prevention of diseases such as cancer and coronary heart disease. However, recent research findings suggested that antioxidants may not be beneficial or might even adversely affect cancer prevention and treatment.2, 3, 4 We hypothesized that this effect might be due to their efficiency at decreasing the levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and thus inhibiting ROS-induced apoptosis. Besides being used for cancer prevention, supplemental antioxidants have usually been prescribed to cancer patients either by clinicians or the patients themselves. However, whether this type of supplementation is beneficial or harmful is uncertain. In addition, the mechanism as to how ROS can induce cellular apoptosis is not fully understood.

Src is known to be overexpressed in more than 80% of colon cancers5 and is closely associated with cancer cell proliferation, survival, angiogenesis, adhesion and metastasis.6, 7, 8 However, the relationship between Src and apoptosis is controversial. Src has been reported to inhibit apoptosis by activating the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway, which protects cells against pro-apoptotic stimuli through the phosphorylation and inactivation of death accelerators, such as Bad, Bax and caspase-9.9, 10, 11 Src could downregulate caspase-8 activity either directly12 or through activation of the p38-mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway.13 In addition, Src could downregulate pro-apoptotic genes to reduce apoptosis.14, 15 On the other hand, Src has also been reported to enhance apoptosis induced by different pro-apoptotic stimuli,16, 17, 18 and this effect is triggered specifically at high Src signaling levels.19

In the present study, we show that antioxidants decrease apoptosis induced by 5-Fu in colon cancer by blocking ROS-dependent Src activation. Cells expressing low levels of Src were more resistant to 5-Fu. Src could bind and phosphorylate caspase-7 at multiple tyrosine residues, resulting in an enhancement of caspase-7 activity and increased cellular apoptosis. Our results indicate a specific role of Src in 5-Fu-induced colon cancer apoptosis and highlight the incompatibility of combining antioxidants with 5-Fu.

Results

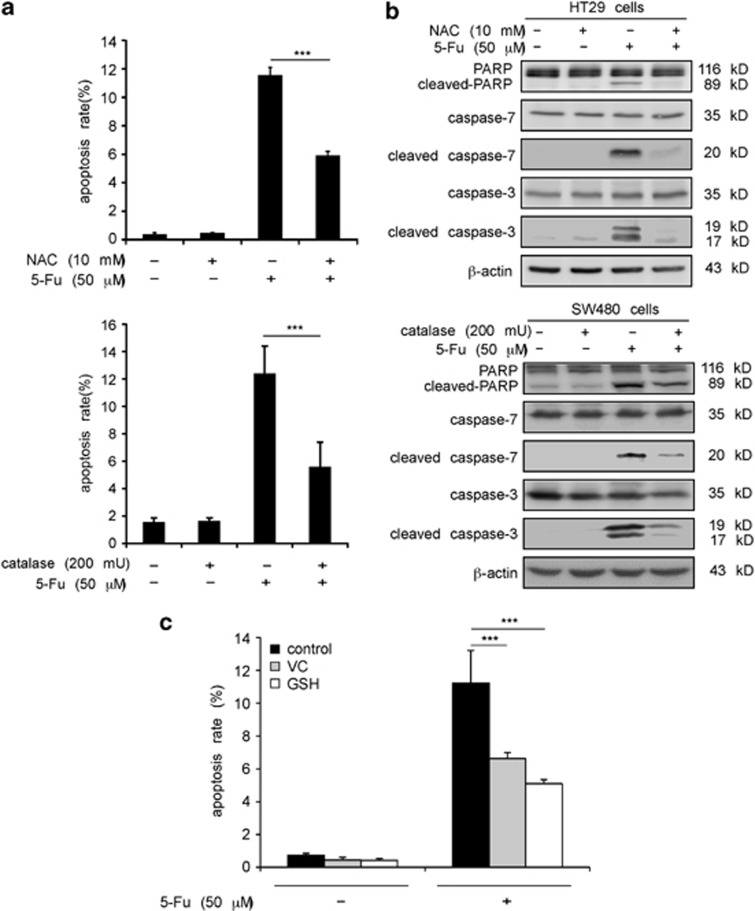

Antioxidants decrease the apoptotic effects of 5-Fu in colon cancer cells

First, we determined whether combining antioxidants with 5-Fu would affect apoptosis in colon cancer cells. Flow cytometry results indicated that N-acetylcysteine (NAC) decreased 5-Fu-induced apoptosis in HT29 colon cancer cells (Figure 1a, upper panel); and a hydrogen peroxide scavenging enzyme, catalase, decreased 5-Fu-induced apoptosis in SW480 colon cancer cells (Figure 1a, lower panel). Western blotting results showed that combining NAC with 5-Fu dramatically decreased cleavage of PARP, caspase-3 and -7 in HT29 cells compared with cleavage induced by 5-Fu alone (Figure 1b, upper panel). Similar effects were observed in SW480 cells treated with both catalase and 5-Fu (Figure 1b, lower panel). Furthermore, we also treated cells with common antioxidants used clinically, reduced L-glutathione (GSH) or vitamin C (VC) followed by 5-Fu treatment. Flow cytometry results showed that both VC and GSH decreased apoptosis induced by 5-Fu in HT29 cells (Figure 1c). Overall, these results indicated that antioxidants might decrease the apoptotic effects of 5-Fu in colon cancer cells.

Figure 1.

Antioxidants decrease the amount of 5-Fu-induced apoptosis in colon cancer cells. (a) HT29 and SW480 colon cancer cells were pretreated with NAC (10 mM, upper panel) or catalase (200 mU, lower panel) for 2 h and then 5-Fu (50 μM) was added to the mixture and cells incubated for an additional 48 h. Apoptosis was determined by flow cytometry. Data are shown as means±S.D. of triplicate measurements. The asterisks indicate a significant decrease in apoptosis in cells treated with NAC or catalase (***P<0.001). (b) HT29 and SW480 cells were treated as in a and harvested. Total and cleaved PARP, caspase-7 and caspase-3 were detected by western blot analysis using specific antibodies. Data shown are representative of results from triplicate independent experiments. (c) HT29 cells were pretreated with VC (50 μg/ml) or GSH (40 μM) for 2 h and then 5-Fu (50 μM) was added to the mixture and cells were incubated for an additional 48 h. Apoptosis was measured by flow cytometry and data are shown as means±S.D. of triplicate measurements. The asterisks indicate a significant decrease in apoptosis in cells treated with VC or GSH (***P<0.001)

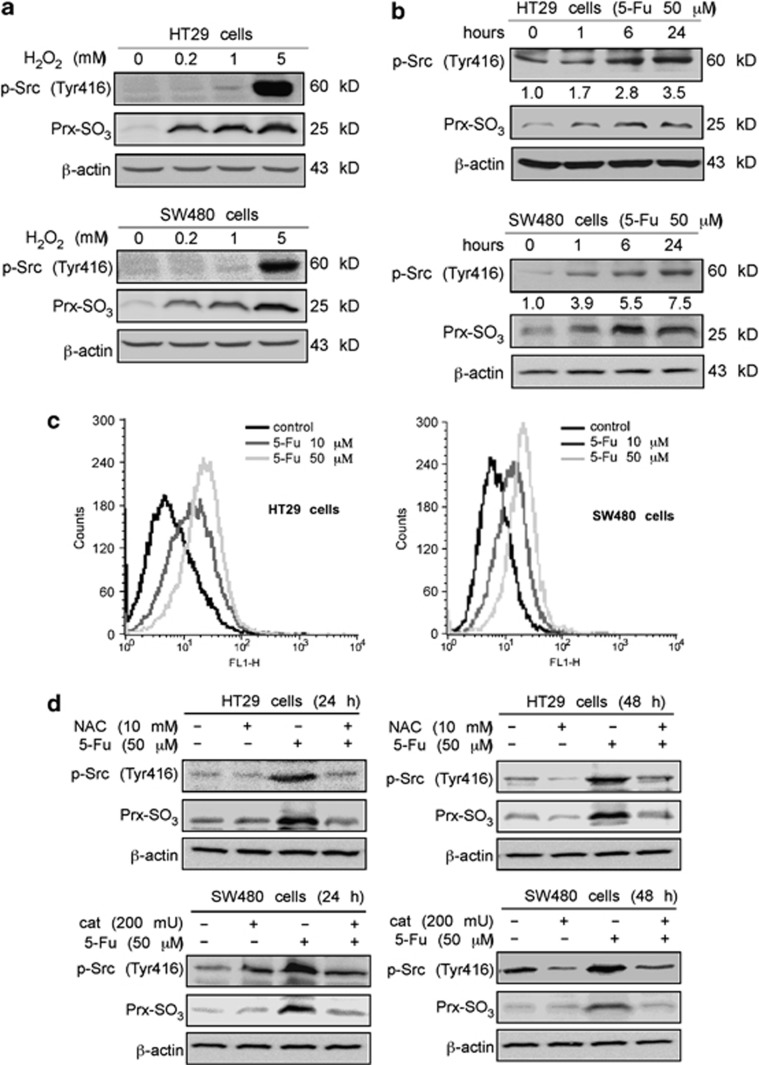

5-Fu-induced Src activation is mediated by ROS

The main effect of antioxidants is to diminish excessive levels of intracellular ROS. However, today's most effective nonsurgical therapeutic approaches to induce apoptosis occur through the generation of ROS.20 ROS reportedly induce dramatic Src activation.21, 22, 23 We treated HT29 and SW480 cells with various doses of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) for 30 min. The level of Prx-SO3 was determined using a specific antibody to serve as a marker of intracellular ROS level.24, 25, 26 Phosphorylated Src (Tyr416) was examined as an indication of Src activity. We found that treatment with H2O2 convincingly increased Src activity with generation of ROS in two cell lines (Figure 2a). We then assessed Src activity with 5-Fu treatment in these two cell lines. HT29 and SW480 cells were treated with 50 μM 5-Fu for various times. 5-Fu treatment induced Src activation in a time-dependent manner with ROS generation in both cell lines (Figure 2b). A dose-dependent increase of intracellular ROS was observed after 5-Fu treatment using the method described in Materials and Methods (Figure 2c). Next, we found that treatment with 5-Fu for 24 or 48 h induced ROS generation and Src activation. In addition, blocking ROS generation with antioxidants dramatically increased Src activation (Figure 2d), demonstrating that 5-Fu-induced activation of Src is mediated by ROS.

Figure 2.

5-Fu-induced Src activation is mediated by reactive oxygen species (ROS). (a) ROS induce Src activation in colon cancer cells. After treatment with various doses of H2O2 for 30 min, cells were harvested. Phosphorylation of Src (Tyr416) and total Prx-SO3 in whole-cell lysates were detected by western blot analysis. (b) Effect of 5-Fu on Src activation and ROS generation. HT29 and SW480 colon cancer cells were treated with 5-Fu (50 μM) for various times. Phosphorylated Src (Tyr416) and total Prx-SO3 levels were determined by western blot analysis. Fold changes in Src activity after 5-Fu treatment are labeled below the western blot image and were calculated using the Image J (NIH) software program. (c) Generation of ROS with increasing concentrations of 5-Fu. HT29 and SW480 cells were treated for 48 h with 5-Fu at the dose indicated. Cells were then incubated for 30 min at 37 °C with 2.5 μM CellROX Green Reagent. FACS Calibur flow cytometry was used to detect ROS as described in Materials and Methods. (d) Effect of combining NAC or catalase and 5-Fu on Src activation. HT29 and SW480 colon cancer cells were pretreated with NAC (10 mM) or catalase (200 mU) for 2 h and then incubated for 24 or 48 h with 5-Fu (50 μM). Phosphorylated Src (Tyr416) and total Prx-SO3 levels were determined by western blotting. β-Actin was detected in the same membrane and served as a loading control. Data shown are representative of results from triplicate independent experiments

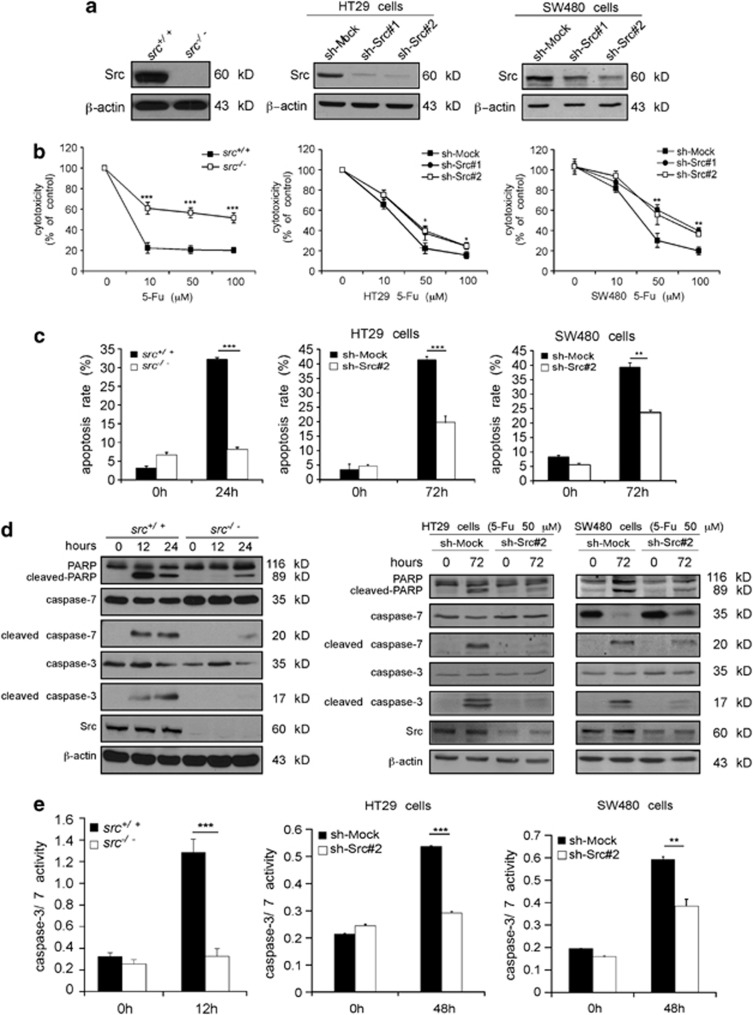

Src contributes to 5-Fu-induced apoptosis

To further investigate the role of Src in 5-Fu-induced cellular apoptosis, three pairs of cell types were treated with 5-Fu. Cells included Src wild-type and knockout mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) and HT29 and SW480 cells stably expressing sh-Mock or sh-Src. The Src level in each cell type was determined by western blot analysis (Figure 3a). Compared with wild-type cells or sh-Mock cells, Src knockout MEFs or Src-knockdown cells were less sensitive to 5-Fu-induced cytotoxicity (Figure 3b) or Fu-induced apoptosis (Figure 3c). Western blot results showed that knockout or knockdown of Src induced less cleaved PARP, cleaved caspase-3 and cleaved caspase-7 than was observed in control cells (Figure 3d). Effector caspase activities were also decreased in cells expressing low levels of Src (Figure 3e). Overall, these results indicated that downregulation of Src decreases 5-Fu-induced apoptosis of MEFs and colon cancer cells.

Figure 3.

Src contributes to 5-Fu-induced apoptosis. (a) The protein level of Src in wild-type (src+/+) and knockout (src−/−) MEFs was determined by western blotting. Sh-Mock and Src knockdown (sh-Src) cells were generated by stable infection with an sh-mock, sh-src#1 or sh-src#2 plasmid into HT29 and SW480 cells. Src protein levels were determined by western blotting. β-Actin was detected in the same membrane and served as a loading control. (b) Comparison of the cytotoxicity of 5-Fu against src+/+ and src−/− MEFs, or in sh-Mock- and sh-Src#1- or sh-Src#2-expressing cells. An MTS assay was used to assess cytotoxicity at 24 h for MEFs or 48 h for colon cancer cells after treatment with 5-Fu. Absorbance was read at 492 nm and data are expressed as percentage of untreated control (100%). Data are shown as means±S.D. of triplicate measurements. The asterisks indicate significantly (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001) less cytotoxicity induced by 5-Fu. (c) 5-Fu-induced apoptosis was determined by flow cytometry. Data are shown as means±S.D. of triplicate measurements. The asterisks indicate significantly less apoptosis induced by 5-Fu (**P<0.01, ***P<0.001). (d) 5-Fu induces less cleaved PARP, cleaved caspase-7 and cleaved caspase-3 in cells expressing low levels of Src. 5-Fu (50 μM) was used to simulate MEFs and colon cancer cells. Total and cleaved PARP, caspase-7 and caspase-3 were detected by western blot analysis using specific antibodies. Data shown are representative of results from triplicate independent experiments. (e) Caspase-3/7 activity is decreased in cells expressing low levels of Src compared with cells expressing normal levels of Src after 5-Fu treatment. 5-Fu (50 μM) was used to simulate cells. After 12 or 48 h, cells were harvested, and caspase-3/7 activity was detected as described in ‘Materials and Methods'. Data are shown as means±S.D. of triplicate measurements. The asterisks indicate significantly lower caspase 3/7 activity (**P<0.01, ***P<0.001)

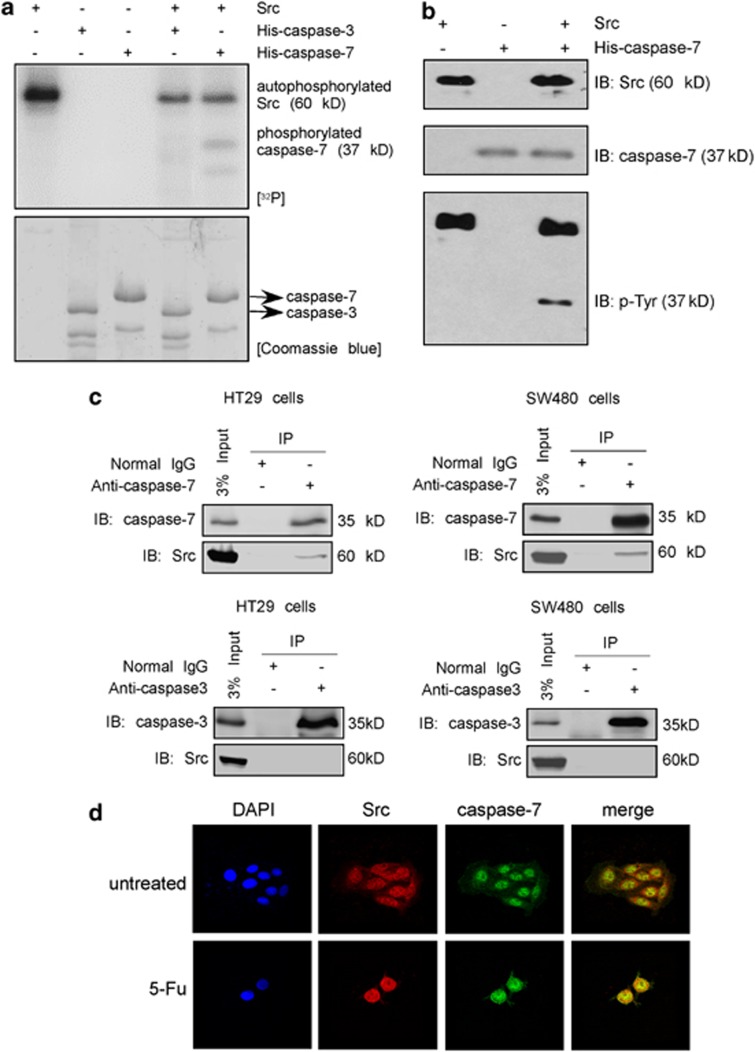

Src phosphorylates caspase-7 in vitro and interacts with caspase-7 in cells

From the above results, we observed that the decreased Fu-induced apoptosis in cells deficient in Src was accompanied by decreased effector caspase activities. Thus, Src might directly modulate caspase-3 and -7 activities. Caspase-3 and -7 proteins were prepared as described in Materials and Methods and then an in vitro kinase assay was performed in the presence of [γ-32P] ATP. The data indicated that Src could phosphorylate caspase-7 in vitro but could only weakly phosphorylate caspase-3 (Figure 4a). Because Src is a known tyrosine kinase, we performed an in vitro kinase assay with Src and caspase-7 and detected phosphorylated tyrosines by western blotting. The results confirmed that Src could phosphorylate caspase-7 at tyrosine residues (Figure 4b). We next determined whether Src could directly bind with caspase-7 and caspase-3 in SW480 and HT29 cells. Cells were harvested and disrupted and caspase-3/7 was immunoprecipitated with anti-caspase-3/7 followed by detection of Src with anti-Src. The results indicated that Src could bind with caspase-7 but not with caspase-3 in cells (Figure 4c). To determine whether Src and caspase-7 could co-localize in cells, an immunofluorescence analysis was performed. The results showed that Src was localized in both the cytoplasm and nucleus and caspase-7 was localized mainly in the nucleus under normal conditions. However, after stimulation with 5-Fu, they co-localized in the nucleus (Figure 4d). To examine the role of caspase-7 in 5-Fu-induced apoptosis, caspase-7 knockout MEFs were treated with 5-Fu. Flow cytometry results (Supplementary Figure 1A) showed a dramatically decreased rate of apoptosis in caspase-7 knockout cells compared with wild-type MEFs. Western blotting results (Supplementary Figure 1B) showed decreased levels of cleaved PARP and cleaved caspase-3 in caspase-7 knockout cells. These data provide strong evidence showing that caspase-7 is important for 5-Fu-induced apoptosis, for which caspase-3 cannot be a substitute. Overall, results indicate that caspase-7, but not caspase-3, could be a key downstream partner of Src in the regulation of cellular apoptosis.

Figure 4.

Src phosphorylates caspase-7 in vitro and interacts with caspase-7 in cells. (a) Src phosphorylates caspase-7 in vitro. Results of an in vitro kinase assay in the presence of [γ-32P] ATP were visualized by autoradiography. Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining was used to assure that the same quantity of protein was loaded. Data shown are representative of results from triplicate independent experiments. (b) Src phosphorylates caspase-7 at tyrosine residues as determined by western blotting following an in vitro kinase assay. IB, immunoblot. (c) Src binds with caspase-7 but not caspase-3 in colon cancer cells. HT29 and SW480 total cell lysates (1 mg) were immunoprecipitated with anti-caspase-3/7, and the immunoprecipitated complex was probed to detect Src. (d) Src and caspase-7 co-localize in SW480 cells. SW480 cells were seeded in four-chamber glass slides and treated or not treated with 5-Fu (50 μM) for 48 h. Src and caspase-7 were detected by immunofluorescence staining with Src and caspase-7 primary antibodies, accompanied by the respective secondary antibody

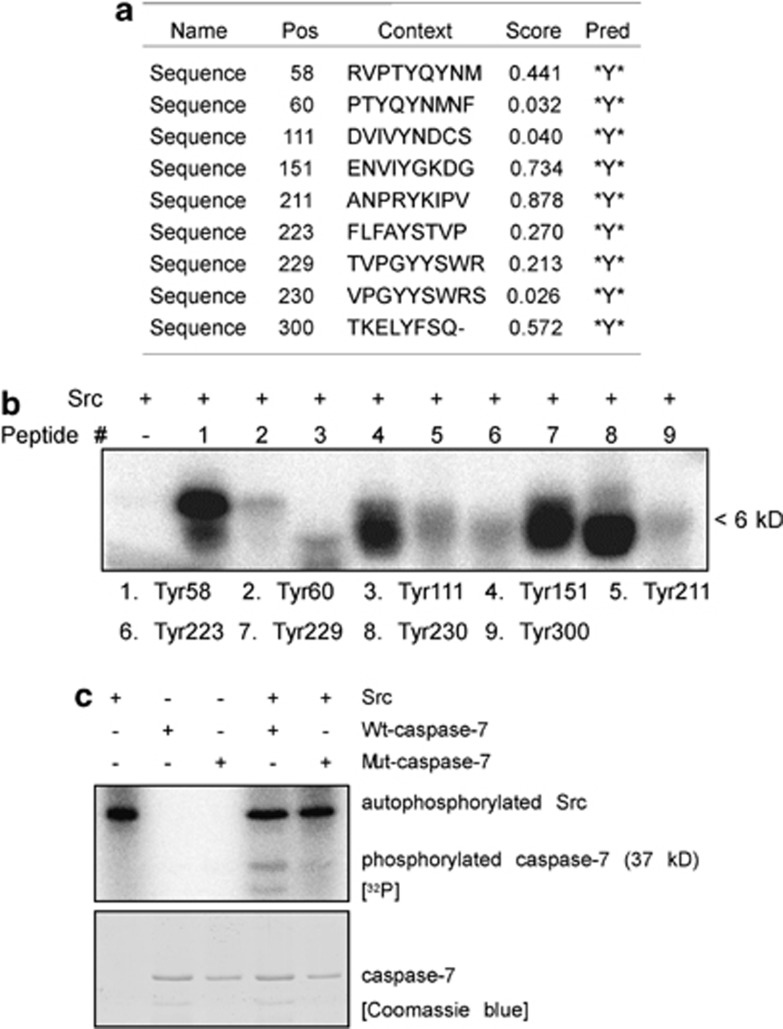

Src phosphorylates caspase-7 at multiple tyrosine sites

After confirming that Src can phosphorylate caspase-7, the next step was to identify the site(s) of caspase-7 that can be phosphorylated by Src. The potential tyrosine phosphorylation sites were predicted by the NetPhos 2.0 software program as previously described27 (Figure 5a). Nine peptides were designed and synthesized commercially (PEPTIDE 2.0, Houston, TX, USA). The peptide array results indicated that Tyr58, Tyr151, Tyr229 and Tyr230 of caspase-7 are likely to be the most important sites to be phosphorylated by Src (Figure 5b). When all four sites were mutated to phenylalanine, the in vitro kinase assay results showed that phosphorylation of the Mut-caspase-7 protein by Src decreased dramatically compared with Wt-caspase-7, suggesting that these four sites, Tyr58, Tyr151, Tyr229 and Tyr230, are the most important sites of caspase-7 to be phosphorylated by Src (Figure 5c).

Figure 5.

Src phosphorylates caspase-7 at multiple tyrosine sites. (a) Potential tyrosine phosphorylation sites of caspase-7 were predicted by the NetPhos 2.0 software program. (b) Peptide mapping of nine synthesized peptides containing potential tyrosine sites. Sites were examined using an in vitro kinase assay with Src in the presence of [γ-32P] ATP and results were visualized by autoradiography. (c) Confirmation of the peptide mapping results using an in vitro kinase assay with Src and wild-type (Wt)-caspase-7 or mutant (Mut)-caspase-7. Results were visualized by autoradiography. Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining was used to assure that the same quantity of protein was loaded. For b and c, representative blots from three independent experiments are shown

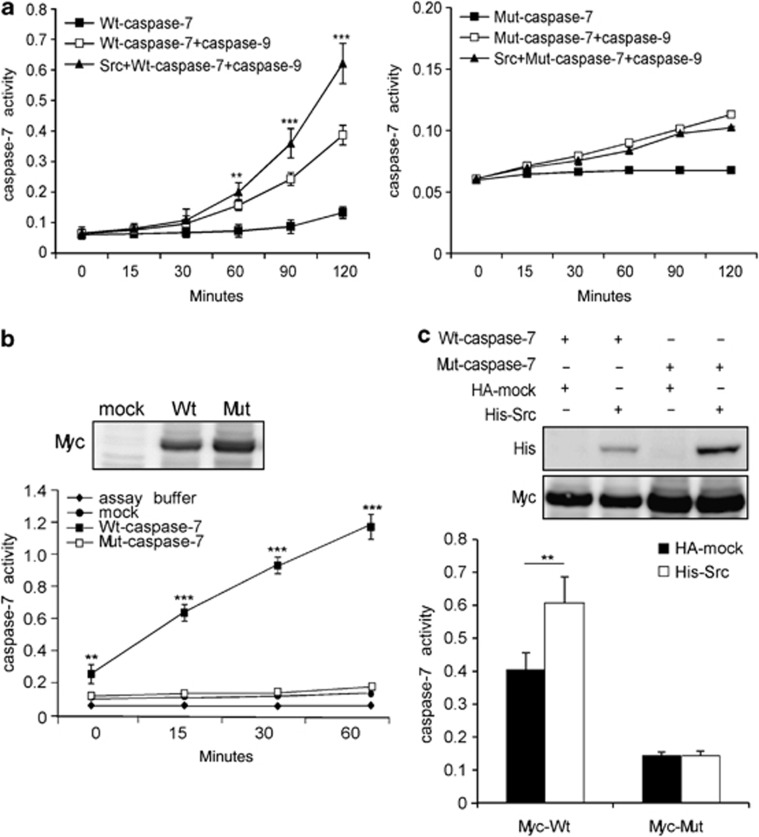

Src enhances caspase-7 activity in vitro and in cells

To determine whether caspase-7 activity can be influenced by Src phosphorylation, an in vitro kinase assay was performed using Src and Wt-caspase-7 or Mut-caspase-7. Caspase-7 activity was detected at different time points. Caspase-9 is known to be the upstream activator of effector caspases in the intrinsic apoptosis pathway. The presence of caspase-9 protein activated caspase-7 to a higher level than in its absence. Our results showed that Wt-caspase-7 was first phosphorylated by Src, and then adding caspase-9 dramatically increased caspase-7 activity (Figure 6a, left panel, Supplementary Figure 2). In contrast, Mut-caspase-7 activity was relatively unaffected in the presence of Src and caspase-9 treatment (Figure 6a, right panel). 293T cells transfected with Wt-myc-caspase-7 exhibited increased caspase-7 activity, whereas little change in caspase-7 activity was observed in cells transfected with Mut-myc-caspase-7 (Figure 6b). Cells co-transfected with Src and Wt-caspase-7 exhibited a 1.5-fold increase in caspase-7 activity compared with Wt-caspase-7 alone. In contrast, no change in caspase-7 activity was observed in cells co-transfected with Src and Mut-caspase-7 compared with cells transfected with only Mut-caspase-7 (Figure 6c). Overall, these results indicated that Src might regulate apoptosis by enhancing caspase-7 activity through phosphorylation.

Figure 6.

Src enhances caspase-7 activity in vitro and in cells. (a) Phosphorylation of caspase-7 by Src increases caspase-7 activity. An in vitro kinase assay was performed using Src and a Wt-caspase-7 (0.8 μg) or Mut-caspase-7 (0.8 μg) protein. The reaction was then incubated with Wt-caspase-9 for 1 h at 32 °C and caspase-7 activity was detected at various time points as described in ‘Materials and Methods'. Data are shown as means±S.D. from triplicate experiments. The asterisks indicate a significant enhancement in caspase-7 activity (**P<0.01, ***P<0.001). (b) 293T cells were transiently transfected with HA-mock, Wt-myc-caspase-7 or Mut-myc-caspase-7 and at 24 h after transfection, cells were harvested. The level of Myc was detected by western blotting and caspase-7 activity was detected at various time points. Data are shown as means±S.D. from triplicate experiments. The asterisks indicate a significant enhancement in caspase-7 activity (**P<0.01, ***P<0.001). (c) 293T cells were transiently co-transfected with HA-mock/His-Src and Wt-myc-caspase-7/Mut-myc-caspase-7 and at 24 h after transfection, cells were harvested. His and Myc were detected by western blot using specific antibodies. Caspase-7 activity is shown as means±S.D. from triplicate experiments. The asterisks indicate a significant enhancement in caspase-7 activity (**P<0.01)

Discussion

ROS have important roles in cell signaling and are essential for various physical and pathological processes in normal cells. ROS were reported to directly cause somatic cell mutagenesis and thereby promote cancer.28 Thus, ROS are often considered oncogenic and life threatening. Ironically, ROS production is a common characteristic of all non-surgical therapeutic approaches, including chemotherapy and radiotherapy, against various cancers because of their ability to trigger cancer cell death.20 This suggests that ROS may have different roles in various stages of cancer. Watson29 suggested that cancer cells that are mainly driven by Ras and Myc are among the most difficult to treat, which might be due to high levels of ROS-destroying antioxidants.

Here we showed that 5-Fu could also induce ROS in colon cancer cells (Figure 2). We found that combining antioxidants with 5-Fu treatment decreased colon cancer cell apoptosis compared with treatment with only 5-Fu (Figure 1). This suggests that when using 5-Fu to kill colon cancer cells, using antioxidants simultaneously or before 5-Fu treatment will decrease its effectiveness. Combining antioxidants with 5-Fu treatment in colon cancer patients might be linked to the observed high 5-Fu drug resistance.

The important role of Src family kinases in cancer cell survival, proliferation, adhesion, angiogenesis and metastasis has been well established. Here we found that 5-Fu can induce ROS-dependent Src activation in colon cancer cells (Figure 2). To further evaluate the role of Src in 5-Fu-induced apoptosis, we used Src knockout MEFs and Src knockdown human colon cancer cells to evaluate the effects of 5-Fu on apoptosis. Our results show that cells expressing low levels of Src are more resistant to 5-Fu treatment (Figure 3). These results suggest that Src might be a target of 5-Fu in colon cancer treatment. Clinical findings indicated that Src activity is highest in moderate to well-differentiated colonic lesions, whereas poorly differentiated carcinomas display Src kinase activity similar to normal colonic mucosa.30 This phenomenon supports our results because almost every patient who was diagnosed with colon cancer receives 5-Fu in the primary stage, which is effective; whereas in later recurrent stages, 5-Fu has little effect possibly due to lower Src activity.

Failure of apoptosis is a main contributor to tumor development and drug resistance. Caspases, a family of cysteine proteases, are central components of cellular apoptosis.31, 32 The two types of apoptotic caspases include initiator (apical) caspases and effector (executioner) caspases. Initiator caspases (e.g., caspase-2, caspase-8, caspase-9 and caspase-10) cleave the inactive pro-forms of the effector caspases, thereby activating them. Effector caspases (e.g., caspase-3, caspase-6, caspase-7) in turn cleave other protein substrates within the cell, to trigger the apoptotic process. Regulating caspase activity is an important means by which cellular apoptosis and chemotherapy resistance are regulated.33, 34

Phosphorylation is an important post-transcriptional modification for various cellular proteins. Phosphoryaltion of caspases by protein kinases has been widely studied. For example, caspase-9 phosphorylation by different kinases has been reported. Interestingly, tyrosine phosphorylation can increase caspase-9 activity, whereas phosphorylation of various serine or threonine sites can decrease caspase-9 activity.35 The phosphorylation of caspase-8 and -3 has also been reported.12, 13 However, the modification and regulation of caspase-7 remains poorly understood. The function of caspase-7 was long assumed to be redundant with the function of caspase-3 because of their similar structure and common protein substrates. In our previous study, we found that phosphorylation of caspase-7 is important in chemotherapeutic drug-induced apoptosis of breast cancer cells.27 Interestingly, PAK2 is a serine/threonine kinase, which decreases caspase-7 activity by phosphorylation. In the present study, we showed that the Src tyrosine kinase can directly phosphorylate and interact with caspase-7 (Figure 4), resulting in increased caspase-7 activity (Figure 6). Our finding is similar to the story of caspase-9 phosphorylation.35 Apparently, the effect of tyrosine phosphorylation is opposite to the effect of serine/threonine phosphorylation of caspase family members. We also showed that caspase-7 is important for 5-Fu induction of apoptosis independent of caspase-3 (Supplementary Figure 1). The relation between Src and caspase-7 might explain why cells with low levels of Src are more resistant to 5-Fu-induced apoptosis (Figure 3). Importantly, antioxidants, such as NAC or catalase, decrease the apoptotic effect induced by 5-Fu in colon cancer cells by regulating Src-dependent caspase-7 phosphorylation. Taken together, our results highlight the role of Src in 5-Fu-induced apoptosis and provide a novel explanation as to why 5-Fu is not effective in combination with some antioxidants in colon cancer patients, which is important for clinical chemotherapy.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and antibodies

5-Fluorouracil (5-Fu), NAC, catalase and VC were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). GSH was purchased from Caymen Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Antibodies to detect total Src, phosphorylated Src (Tyr416), cleaved caspase-7 (Asp198), caspase-3, PARP and phosphorylated tyrosines were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA, USA). The antibody to detect total caspase-7 was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Anti-peroxiredoxin-SO3 (Prx- SO3) was from Abcam Inc. (Cambridge, MA, USA). The small hairpin RNA constructs against Src (number 1 sense sequence, 5′-GCTCGGCTCATTGAAGACAAT-3′ number 2 sense sequence, 5′-GACAGACCTGTCCTTCAAGAA-3′) used in this study were from the BioMedical Genomics Center at the University of Minnesota. The Src active kinase was purchased from Millipore Corp. (Billerica, MA, USA).

Cell culture and transfection

SW480 human colon cancer cells, HEK293T cells, wild-type and Src knockout mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) and wild-type and caspase-7 knockout MEFs were cultivated in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. HT29 human colon cancer cells were maintained in McCoy's 5A medium (modified) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. All cells used in these studies were maintained with antibiotics at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator. For transfection experiments, the jet-PEI (Qbiogen, Inc., Carlsbad, CA, USA) reagent was used according to the manufacturer's instructions.

3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol- 2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2H-tetrazdium (MTS) assay

To estimate cytotoxicity, MEFs (5000 cells per well) or colon cancer cells (2000 cells per well) were seeded into 96-well plates. After incubation for 24 h, cells were treated with different concentrations of 5-Fu and incubated for another 24 or 48 h. The MTS reagent included in the assay kit (20 μl; Promega, Madison, WI, USA) was then added and cells were incubated for an additional 1 h at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator. Absorbance was read at an optical density of 492 nm.

Western blot analysis

Cellular proteins were extracted using radioimmune precipitation assay lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM EDTA, and protease inhibitor mixture), separated by SDS-PAGE, and then transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA). The membranes were incubated with an appropriate specific primary antibody and a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. Protein bands were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence reagent and exposed using the ImageQuant LAS4000 system (GE, Piscataway, NJ, USA)

Plasmid preparation and purification of caspase proteins

The human caspase-3 and caspase-7 plasmids were purchased from Addgene (Cambridge, MA, USA) and subcloned into the pCMV-Myc vector for transfection and into the pET-46 Ek/LIC vector for protein purification. Human pET-23b-His-caspase-9 was purchased from Addgene. Mutant caspase-7 was constructed using pCMV-Myc-caspase-7 and pET-46 Ek/LIC-caspase-7 with four mutated sites (Y58F, Y151F, Y229F, Y230F) and the QuikChange Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). The mutant plasmid was sent to Genewiz, Inc. for DNA sequencing. His-wild-type caspase-7 (Wt-caspase-7) and His-mutant caspase-7 (Mut-caspase-7) proteins were induced in Escherichia coli Rosetta (DE3) at 25 °C for 4 h by the addition of 0.5 mM isopropyl 1-thio-β-D-galactopyranoside (IPTG). His-wild-type caspase-3 (Wt-caspase-3) was induced in E. coli BL21 bacteria at 25 °C for 4 h by the addition of 0.5 mM IPTG. His-wild-type caspase-9 (Wt-caspase-9) was induced in E. coli BL21 bacteria at 30 °C for 1 h by the addition of 0.5 mM IPTG. All proteins were purified using nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA, USA) and eluted with 200 mM imidazole.

In vitro kinase assay

Purified Wt-caspase-7, Mut-caspase-7, Wt-caspase-3 and caspase-7 peptides were incubated with active Src (Upstate Biotechnology, Inc., Boston, MA, USA) and 1 mCi of [γ-32P] ATP, 100 μM unlabeled ATP and kinase buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT and 0.01% Brij 35; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.). Each reaction was incubated in a 32 °C water bath for 40 min and the reaction was stopped by adding 6 × SDS loading buffer. The proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and visualized by autoradiography.

Caspase-7 activity assay

To detect caspase-7 activity, an in vitro kinase assay was conducted using Wt- or Mut-caspase-7 proteins (0.8 μg each) incubated with active Src. Then caspase-7 activity was detected using the Caspase-3 Colorimetric Assay kit (Millipore Corp., Temecula, CA, USA) because caspase-3 and caspase-7 have the same substrate. For detecting caspase-7 activity in cells, whole-cell lysates were harvested and 200 μg of protein were used to detect caspase-7 activity according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Flow cytometry analysis

5-Fu-induced cellular apoptosis was determined using the Annexin V-FITC apoptosis detection kit (MBL International Corp., Woburn, MA, USA) following the manufacturer's suggested protocols. After treatment for different times and with various doses of 5-Fu, cells were harvested, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then incubated for 15 min at room temperature with Annexin V-FITC plus propidium iodide. Apoptosis was analyzed by a FACS Calibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA).

Oxidative stress detection

After treatment with 5-Fu, CellROX Green Reagent (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA) was added to cells to a final concentration of 2.5 μM and incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator for 30 min. Then cells were harvested and analyzed on a FACS Calibur flow cytometer, placing the CellROX Green Reagent signal in FL1. Intact cells were gated in the FSC/SSC plot to exclude small debris. The resulting FL1 data were plotted on a histogram.

Endogenous immunoprecipitation

HT29 and SW480 total cell lysates (1 mg) were immunoprecipitated with a total capase-3 or caspase-7 antibody, and the immunoprecipitated complex was probed to detect Src.

Confocal laser scanning fluorescence microscopy

SW480 cells (1 × 105) were seeded in a four-chamber polystyrene vessel tissue culture glass slide (BD Biosciences) and were treated or not treated with 50 μM 5-Fu for 48 h in a 37 °C incubator. Cells were fixed with 4% formalin for 15 min at room temperature in the dark. After gentle washing twice for 10 min each with PBS, cells were blocked with PBS, 0.02% Tween-20 and 1% BSA in a 37 °C incubator for 1 h. Cells were then incubated with a 1 : 100 dilution of a Src rabbit antibody and a 1 : 50 dilution of a caspase-7 mouse antibody in PBS and 3% BSA by gently rocking at 4 °C overnight. After washing twice for 5 min each, cells were incubated with a 1 : 200 dilution of Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit antibody and Alexa Fluor 568 goat anti-mouse antibody (Invitrogen) for 1 h in the dark. Co-localization of proteins was observed by laser scanning confocal microscopy (Nikon C1s1 Confocal Spectral Imaging System, Nikon Instruments Co., Melville, NY, USA) using a CFI Plan Fluor × 40 oil objective and then analyzed using the EZ-C1 (v3.20) software program (Nikon).

Statistical analysis

All quantitative data are presented as mean values±standard deviations as indicated. Statistically significant differences were determined using the Student's t-test. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by The Hormel Foundation and National Institutes of Health grants CA166011, CA 172457, R37 CA081064 and ES016548. We thank Todd Schuster for technical assistance with flow cytometry. We thank Tatyana Zykova and Margarita Malakhova for help with caspase protein family purification. We also thank Jong Eun Kim for assisting with the detection of ROS.

Glossary

- 5-Fu

5-fluorouracil

- NAC

N-acetylcysteine

- PARP

poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase

- H2O2

hydrogen peroxide

- Prx-SO3

peroxiredoxin-SO3

- MEFs

mouse embryonic fibroblasts

- VC

vitamin C

- GSH

reduced glutathione

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- IPTG

isopropyl 1-thio-β-D-galactopyranoside

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Cell Death and Disease website (http://www.nature.com/cddis)

Edited by C Munoz-Pinedo

Supplementary Material

References

- Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjelakovic G, Nikolova D, Gluud LL, Simonetti RG, Gluud C. Mortality in randomized trials of antioxidant supplements for primary and secondary prevention: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2007;297:842–857. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.8.842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjelakovic G, Nikolova D, Simonetti RG, Gluud C. Antioxidant supplements for prevention of gastrointestinal cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2004;364:1219–1228. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17138-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papaioannou D, Cooper KL, Carroll C, Hind D, Squires H, Tappenden P, et al. Antioxidants in the chemoprevention of colorectal cancer and colorectal adenomas in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:1085–1099. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2010.02289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W, Cartwright T, Hainsworth J, Heim W, et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2335–2342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlessinger J. New roles for Src kinases in control of cell survival and angiogenesis. Cell. 2000;100:293–296. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80664-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summy JM, Gallick GE. Src family kinases in tumor progression and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2003;22:337–358. doi: 10.1023/a:1023772912750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeatman TJ. A renaissance for SRC. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:470–480. doi: 10.1038/nrc1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi H, Wang HG. The protein kinase PKB/Akt regulates cell survival and apoptosis by inhibiting Bax conformational change. Oncogene. 2001;20:7779–7786. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zha J, Harada H, Yang E, Jockel J, Korsmeyer SJ. Serine phosphorylation of death agonist BAD in response to survival factor results in binding to 14-3-3 not BCL-X(L) Cell. 1996;87:619–628. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81382-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardone MH, Roy N, Stennicke HR, Salvesen GS, Franke TF, Stanbridge E, et al. Regulation of cell death protease caspase-9 by phosphorylation. Science. 1998;282:1318–1321. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5392.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cursi S, Rufini A, Stagni V, Condo I, Matafora V, Bachi A, et al. Src kinase phosphorylates Caspase-8 on Tyr380: a novel mechanism of apoptosis suppression. EMBO J. 2006;25:1895–1905. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarado-Kristensson M, Melander F, Leandersson K, Ronnstrand L, Wernstedt C, Andersson T. p38-MAPK signals survival by phosphorylation of caspase-8 and caspase-3 in human neutrophils. J Exp Med. 2004;199:449–458. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reginato MJ, Mills KR, Becker EB, Lynch DK, Bonni A, Muthuswamy SK, et al. Bim regulation of lumen formation in cultured mammary epithelial acini is targeted by oncogenes. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:4591–4601. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.11.4591-4601.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez J, Hesling C, Prudent J, Popgeorgiev N, Gadet R, Mikaelian I, et al. Src tyrosine kinase inhibits apoptosis through the Erk1/2- dependent degradation of the death accelerator Bik. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19:1459–1469. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2012.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady RR, Loveridge CJ, Dunlop MG, Stark LA. c-Src dependency of NSAID-induced effects on NF-kappaB-mediated apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:1069–1077. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan P, Griffith OL, Agboke F, Anur P, Zou X, McDaniel RE, et al. c-Src modulates estrogen-induced stress and apoptosis in estrogen-deprived breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2013;73:4510–4520. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niture SK, Jain AK, Shelton PM, Jaiswal AK. Src subfamily kinases regulate nuclear export and degradation of transcription factor Nrf2 to switch off Nrf2-mediated antioxidant activation of cytoprotective gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:28821–28832. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.255042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Vidal M, Warner S, Read R, Cagan RL. Differing Src signaling levels have distinct outcomes in Drosophila. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10278–10285. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Yi J. Cancer cell killing via ROS: to increase or decrease, that is the question. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7:1875–1884. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.12.7067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopetz S, Lesslie DP, Dallas NA, Park SI, Johnson M, Parikh NU, et al. Synergistic activity of the SRC family kinase inhibitor dasatinib and oxaliplatin in colon carcinoma cells is mediated by oxidative stress. Cancer Res. 2009;69:3842–3849. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannoni E, Buricchi F, Raugei G, Ramponi G, Chiarugi P. Intracellular reactive oxygen species activate Src tyrosine kinase during cell adhesion and anchorage-dependent cell growth. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:6391–6403. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.15.6391-6403.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pu M, Akhand AA, Kato M, Hamaguchi M, Koike T, Iwata H, et al. Evidence of a novel redox-linked activation mechanism for the Src kinase which is independent of tyrosine 527-mediated regulation. Oncogene. 1996;13:2615–2622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Jo HY, Kim MH, Cha YY, Choi SW, Shim JH, et al. H2O2-dependent hyperoxidation of peroxiredoxin 6 (Prdx6) plays a role in cellular toxicity via up-regulation of iPLA2 activity. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:33563–33568. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806578200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nardozza AP, D'Orazio M, Trapannone R, Corallino S, Filomeni G, Tartaglia M, et al. Reactive oxygen species and epidermal growth factor are antagonistic cues controlling SHP-2 dimerization. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32:1998–2009. doi: 10.1128/MCB.06674-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zykova TA, Zhu F, Vakorina TI, Zhang J, Higgins LA, Urusova DV, et al. T-LAK cell-originated protein kinase (TOPK) phosphorylation of Prx1 at Ser-32 prevents UVB-induced apoptosis in RPMI7951 melanoma cells through the regulation of Prx1 peroxidase activity. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:29138–29146. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.135905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Wen W, Liu K, Zhu F, Malakhova M, Peng C, et al. Phosphorylation of caspase-7 by p21-activated protein kinase (PAK) 2 inhibits chemotherapeutic drug-induced apoptosis of breast cancer cell lines. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:22291–22299. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.236596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibutani S, Takeshita M, Grollman AP. Insertion of specific bases during DNA synthesis past the oxidation-damaged base 8-oxodG. Nature. 1991;349:431–434. doi: 10.1038/349431a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson J. Oxidants, antioxidants and the current incurability of metastatic cancers. Open Biol. 2013;3:120144. doi: 10.1098/rsob.120144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber TK, Steele G, Summerhayes IC. Differential pp60c-src activity in well and poorly differentiated human colon carcinomas and cell lines. J Clin Invest. 1992;90:815–821. doi: 10.1172/JCI115956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuribayashi K, Mayes PA, El-Deiry WS. What are caspases 3 and 7 doing upstream of the mitochondria. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006;5:763–765. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.7.3228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajra KM, Liu JR. Apoptosome dysfunction in human cancer. Apoptosis. 2004;9:691–704. doi: 10.1023/B:APPT.0000045786.98031.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cillessen SA, Hess CJ, Hooijberg E, Castricum KC, Kortman P, Denkers F, et al. Inhibition of the intrinsic apoptosis pathway downstream of caspase-9 activation causes chemotherapy resistance in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:7012–7021. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara S, Miyake H, Arakawa S, Kamidono S, Hara I. Over expression of inhibitor of caspase 3 activated deoxyribonuclease in human renal cell carcinoma cells enhances their resistance to cytotoxic chemotherapy in vivo. J Urol. 2001;166:2491–2494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan LA, Clarke PR. Apoptosis and autophagy: Regulation of caspase-9 by phosphorylation. FEBS J. 2009;276:6063–6073. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.