Abstract

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are believed to exert their regenerative effects through differentiation and modulation of inflammatory responses. However, the relationship between the severity of inflammation and stem cell-mediated tissue repair has not been formally investigated. In this study, we applied different concentrations of dexamethasone (Dex) to anti-CD3-activated splenocyte cultured with or without MSCs. As expected, Dex exhibited a classical dose-dependent inhibition of T-cell proliferation. Surprisingly, although MSCs also blocked T-cell proliferation, the presence of Dex unexpectedly showed a dose-dependent reversion of T-cell proliferation. This effect of Dex was found to be exerted through interfering STAT1 phosphorylation-prompted expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS). Interestingly, inflammation-induced chemokines in MSCs was unaffected. To test the role of inflammation severity in stem cell-mediated tissue repair, we employed mice with carbon tetrachloride-induced advanced liver fibrosis and found that although MSCs alone were effective, concurrent administration of Dex abrogated the therapeutic effects of MSCs on fibrin deposition, serum levels of bilirubin, albumin, and aminotransferases, as well as T-lymphocyte infiltration, especially IFN-γ+CD4+ and IL-17A+CD4+T cells. Likewise, iNOS−/− MSCs, which produce chemokines but not nitric oxide under inflammatory conditions, are ineffective in treating advanced liver fibrosis. Therefore, inflammation has a critical role in MSC-mediated tissue repair. In addition, concomitant application of MSCs with steroids should be avoided.

Keywords: inflammation, mesenchymal stem cell, tissue repair, steroid, liver fibrosis

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) exist in almost all tissues.1, 2, 3 They are believed to have important roles in tissue repair and regeneration through differentiating into specific cell lineages.4 Recently, MSCs have been shown to be strongly immunomodulatory and are effective in treating various diseases, especially severe inflammatory disorders, such as graft-versus-host disease (GvHD),5 systemic lupus erythematosus,6 Crohn's disease,7 myocardial infarction,8 multiple sclerosis,9 and neural degeneration.10 Interestingly, although MSCs are capable of modulating immune responses in human and in mouse, they employ different mechanisms: MSCs from mouse use inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and MSCs from human utilize indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase (IDO).11, 12 The metabolic activities of these enzymes act in concert with chemokines to exert strong immunosuppressive effects.11 As the immunosuppressive activities of MSCs are induced by inflammatory cytokines,11 it is not known whether the degree of inflammation has a role in MSC-mediated tissue repair.

Steroid-based anti-inflammatory therapy is often used to reduce severe inflammatory responses in clinical practice.13, 14 It should be noted that steroid resistance frequently develops in patients.15, 16, 17 Interestingly, in clinical investigations when MSCs are used to promote tissue repair in steroid-resistant patients, in whom inflammation continues, impressive results are often achieved.5, 18 Unfortunately, the administration of MSCs has not been always successful. It has been reported that in animal models, transfusion of MSCs concurrent with immunosuppressants can actually facilitate the development of graft rejection.19 Indeed, in a recent clinical trial using combined therapy with Prochymal, the first approved MSC drug in Canada and New Zealand, along with steroids in GvHD patients, there was no significant clinical improvement.20 Thus, it is highly possible that MSCs and immunosuppressants counteract each other.

To test this novel hypothesis, we focused on examining whether steroids exert direct effects on MSCs, and thereby interfere with the therapeutic effects of MSCs. We employed dexamethasone (Dex) and investigated its effects on immunosuppression of MSCs on proliferation of anti-CD3-activated splenocytes. Although either MSCs or Dex could inhibit T-cell proliferation, the presence of Dex exerted a dose-dependent rescue of T-cell proliferation. Our further studies showed that Dex blocked phosphorylation of STAT1 in MSCs activated by inflammatory cytokines, followed by decreased expression of iNOS in mouse MSCs and IDO in human MSCs. Interestingly, Dex had no effect on chemokine expression induced by inflammatory cytokines in mouse and human MSCs, which could promote inflammation by recruiting inflammatory cells. As it has been shown that MSCs exert therapeutic effects on liver cirrhosis,21, 22 we employed a well-established carbon tetrachloride (CCl4)-induced liver fibrosis model in mouse21, 23 to test the interaction between MSCs and steroids. We demonstrated that MSCs indeed could effectively reverse liver fibrosis. However, when Dex was co-administered with mouse bone marrow-derived MSCs, this therapeutic effect was completely abolished. These studies demonstrate that although MSCs are effective in treating advanced liver fibrosis, existing inflammation is prerequisite for MSC-mediated reversal of liver cirrhosis.

Results

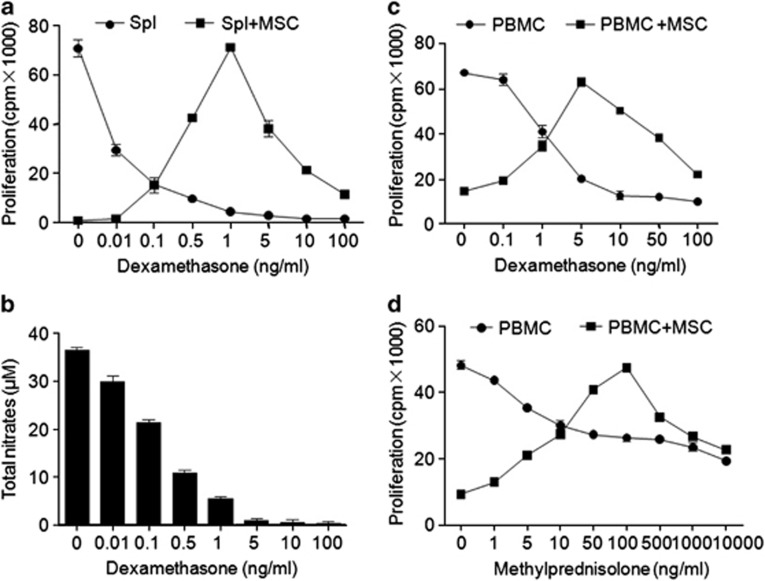

Dex reversed the immunosuppressive effects of MSCs

The immunosuppressive effects of treating with either Dex or MSCs are well established; the effect of Dex on MSCs, however, is unknown. Therefore, to examine this interaction, we added graded amounts of Dex to anti-CD3-activated mouse splenocytes with or without MSC co-culture. As expected, we observed potent inhibition of splenocyte proliferation by MSCs in the absence of Dex (‘0' point on X-axis), whereas Dex alone also caused typical dose-dependent suppression (Figure 1a). Astonishingly, when Dex was added to the co-cultures of MSCs and activated splenocytes, there was a dose-dependent reversal of MSC-mediated immunosuppression. The maximal effect occurred at 1 ng/ml Dex (Figure 1a), which, perhaps tellingly, also happens to be the minimum dose at which Dex nearly completely suppresses activated T cells on its own. In addition, the reversal of MSC-mediated inhibition of anti-CD3 activated splenocyte proliferation by Dex, correlated closely with its dose-dependent inhibition of total nitrate production in the same cultures (Figure 1b). To determine whether a similar effect occurs with human cells, we examined the effects of Dex on MSC-mediated immunosuppression of OKT3-activated human peripheral blood lymphocytes and found that Dex does indeed reverse immunosuppression caused by human MSCs as seen in the mouse system (Figure 1c). Similar results were obtained with methylprednisolone, which is a kind of steroid most commonly used clinically (Figure 1d). Therefore, MSC-mediated immunosuppression requires existing inflammation and can be completely reversed by steroids.

Figure 1.

Dex completely reversed the immunosuppressive effects of MSCs in vitro. (a) Splenocytes from C57BL/6 mice were co-cultured with MSCs from WT C57BL/6 mice (1 : 20 ratio of MSC to splenocytes) in the presence of anti-CD3, with or without Dex, and proliferation was assayed by 3H-Tdr incorporation. (b) Total nitrates in the supernatant of the cultures from (a) were assayed by modified Griess reagent. (c and d) Proliferation of human PBMCs co-cultured with human MSCs (1 : 10 ratio of MSCs to PBMCs) in the presence of anti-CD3 and anti-CD28, with or without Dex or methylprednisolone, respectively. Values are shown as mean±S.E.M. Representative of five independent experiments

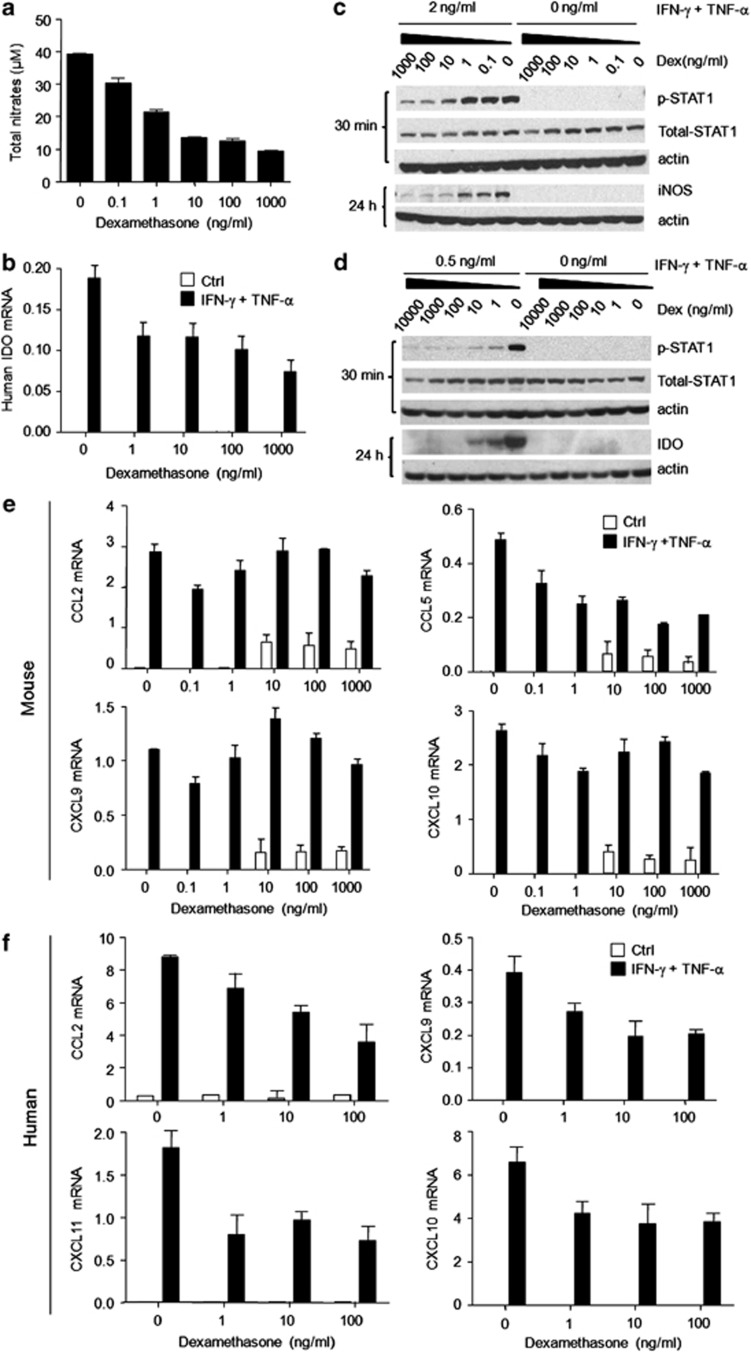

Dex blocked inflammatory cytokine-induced expression of immunosuppressive iNOS and IDO through inhibiting STAT1 phosphorylation

Our previous studies have demonstrated that MSCs become immunosuppressive in the presence of interferon-γ (IFN-γ), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-1α (IL-1α), or interleukin-1β (IL-1β) by upregulating their expression of iNOS (in mouse cells) or IDO (in human cells).11, 12 To determine whether Dex acts to inhibit the expression of iNOS or IDO by MSCs, we stimulated MSCs with inflammatory cytokines and measured iNOS or IDO in mouse or human MSCs, respectively. We found that iNOS and IDO levels were indeed decreased in the presence of Dex (Figures 2a–d). As STAT1 is a critical signaling molecule for IFN-γ-induced expression of iNOS or IDO, we next examined whether Dex affects STAT1 phosphorylation. When MSCs were treated with IFN-γ and TNF-α in the presence of graded concentrations of Dex, we found that STAT1 phosphorylation was indeed inhibited in both mouse MSCs and human MSCs (Figures 2c and d). Therefore, Dex prevents inflammatory cytokine-induced immunosuppression by blocking iNOS or IDO expression likely via modulation of STAT1 phosphorylation.

Figure 2.

Dex blocked the expression of inflammatory cytokine-induced iNOS and IDO through inhibiting STAT1 phosphorylation. Cultured mouse MSCs or human MSCs were supplemented with the indicated combinations of IFN-γ and TNF-α (10 ng/ml each), with or without Dex for 24 h. (a) Nitrates were assayed in mouse MSC supernatants. (b) IDO mRNA in human MSCs was determined using real-time PCR. (c) Cultured mouse MSCs were supplemented with IFN-γ and TNF-α (2 ng/ml each), and graded dosages of Dex. STAT1 phosphorylation and iNOS expression at 30 min and 24 h were detected by western blot analysis. (d) Similarly, human MSCs were supplemented with IFN-γ and TNF-α (0.5 ng/ml each) with or without Dex. STAT1 phosphorylation and IDO expression at 30 min and 24 h were examined. (e) Mouse MSCs were stimulated with IFN-γ and TNF-α (10 ng/ml each) for 12 h, in the presence of graded doses of Dex. Levels of mRNA for CCL2, CCL5, CXCL9, and CXCL10 were detected and normalized to β-actin. (f) Similarly, CCL2, CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11 mRNA were detected in human MSCs, after stimulation with IFN-γ and TNF-α (10 ng/ml each) for 12 h in the presence of graded doses of Dex. Values are shown as mean±S.E.M. Representative of four independent experiments

Dex does not affect inflammatory cytokine-induced expression of chemokines

Our previous studies have demonstrated that on stimulation with inflammatory cytokines, MSCs also produce chemokines,11, 12 which attract immune cells into close proximity with MSCs, allowing the local high concentrations of NO or IDO causing tryptophan exhaustion to suppress T-cell function. Interestingly, in the presence of iNOS inhibitor or genetic knockdown of iNOS, inflammatory cytokine-stimulated MSCs actually promote immune reactions through the action of chemokines they produce.24 We here found that when MSCs are stimulated with IFN-γ and TNF-α, addition of Dex blocked the expression of iNOS or IDO, but not chemokines (CXCL10, CXCL9, CCL2, CCL5, and CXCL11), in both mouse and human systems (Figures 2e and f). Therefore, it is highly probable that these chemokines are still capable of recruiting inflammatory cells.

Effectiveness of MSC therapy in treating advanced liver fibrosis in a mouse model

To test the interaction between MSCs and steroid during inflammation in vivo, we employed a CCl4-induced advanced liver fibrosis in mice, a well-established inflammatory disease model. We adopted this model in our study using a schedule as outlined in Supplementary Figure 1a. After 8 weeks of CCl4 inoculation, liver abnormality could be clearly observed even by gross visual examination (Supplementary Figure 1b). Histologically, characteristic liver cirrhosis morphology was observed, as shown by disrupted liver structure and formation of nodules of regenerative parenchyma surrounded by fibrotic septae (Supplementary Figure 1c). Interestingly, when MSCs (1 × 106) were administered intravenously (i.v.) 8 weeks after CCl4 induction and the effects were examined 3 days later, we found total bilirubin (TB), albumin (Alb), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) were reversed significantly in MSC-treated cirrhotic mice (Supplementary Figure 1d). Moreover, histological analysis revealed a dramatic amelioration of the signs of liver cirrhosis 1 week after MSC transfusion (Supplementary Figures 1c, e and f). The distribution of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) was also significantly decreased (Supplementary Figure 2), accompanied by proliferation of hepatic parenchymal cells labeled with 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU; Supplementary Figure 3). Meanwhile, MSC administration could also decrease the activities of matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2), a collagenase mainly produced by myofibroblasts that have been indicated to have a role in liver fibrosis;25 however, we did not find much change in matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) (Supplementary Figure 4). Therefore, CCl4-induced liver fibrosis is an appropriate animal model of advanced liver fibrosis with which we will further examine the effects of steroids on MSC-mediated therapy.

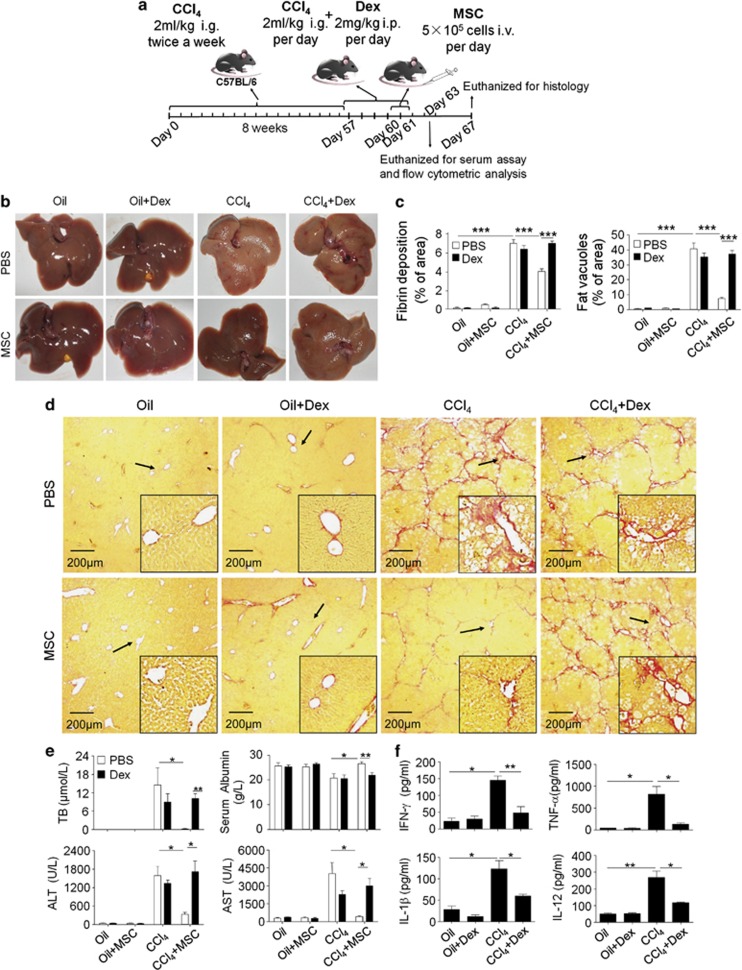

Dex completely reversed the therapeutic effect of MSCs

To investigate whether inflammation is critical for the therapeutic effect of MSCs, Dex was administered daily for each of the 4 days (2 mg/kg, intraperitoneally (i.p.)) before and concurrent with MSC therapy (Figure 3a). Surprisingly, we found that Dex completely reversed the therapeutic effect of MSCs. When livers were examined grossly or histologically, we found that Dex treatment resulted in complete reversal of the effects of MSCs (Figures 3b and d), especially the reduction in fibrin deposition and the appearance of fat vacuoles (Figure 3c). Furthermore, changes in α-SMA, activities of MMPs, and hepatic parenchymal cell proliferation induced by MSC transfusion alone could not be observed when MSCs and Dex were co-administrated (Supplementary Figures 2–4). Moreover, Dex also reversed the MSC-mediated improvements in serum levels of TB, Alb, and amino transferases (Figure 3e). Therefore, Dex co-administration completely abolishes the therapeutic effect of MSCs on liver fibrosis.

Figure 3.

Steroid co-administration abolished the therapeutic effects of MSCs on advanced liver fibrosis in mice. (a) Timeline of the protocol to induce liver fibrosis in mice, and treatment with Dex and MSCs. (b) On euthanization, the livers were collected and representative specimens from each group were photographed. (c) Quantitative analysis of presence of liver fibrosis and fat vacuoles. (d) Fibrin deposition was detected by sirius red staining ( × 40 magnification, scale bar=200 μm; arrows indicate portal areas, which were shown in lower right corner). The liver showed extensive fibrotic development, formation of regenerative nodules, and distortion of the vascular architecture in mouse cirrhotic liver without MSCs transfusion. (e) The serum concentrations of TB, Alb, ALT, and AST in mice from each group were determined. (f) On day 60 (after liver fibrosis induction with or without Dex injection), serum levels of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-12 were assayed by the Luminex technology (Bio-Plex, Bio-Rad). For this figure, values are shown as mean±S.E.M. and statistical significance indicated as *P<0.05, **P<0.01, and ***P<0.001. Representative of three independent experiments; n=7–10

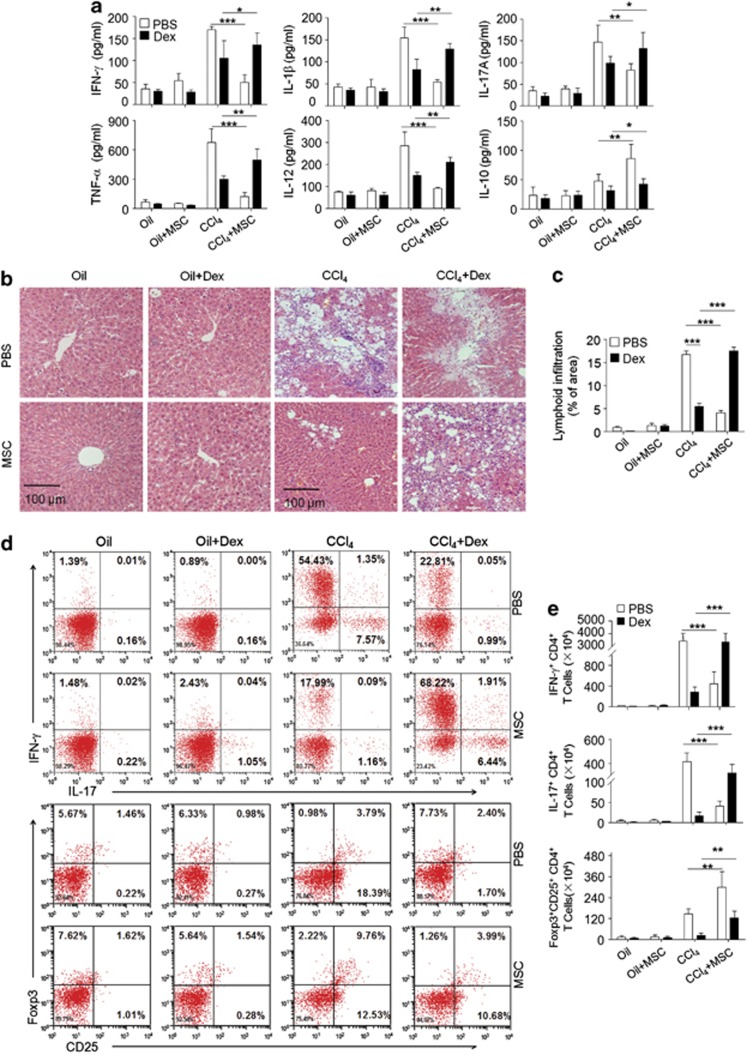

Dex reversed the anti-inflammatory effect of MSCs in vivo

To determine whether Dex alone indeed had anti-inflammatory effects in this mouse model of liver cirrhosis, we measured the inflammatory status in these mice. Serum samples were collected daily following Dex injection, and the changes in inflammatory cytokine levels were monitored by microbead-based multiplex cytokine assay. We found, as expected, that serum levels of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1β, and interleukin-12 (IL-12) were dramatically reduced after Dex treatment (Figure 3f), showing that Dex effectively suppressed inflammation in these mice. Although MSCs alone, as with administration of Dex alone, caused reductions in serum levels of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-12, and interleukin-17 (IL-17) compared with control mice, these changes did not occur with co-administration of Dex and MSCs (Figure 4a).

Figure 4.

Dex abolished the anti-inflammatory effect of MSCs. (a) On day 63, serum levels of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-12 in each group were assayed by Luminex technology. (b) On day 67, some mice were euthanized and liver sections from each group were stained with hematoxylin and eosin ( × 100 magnification). (c) Quantitative analysis of lymphoid infiltration in liver sections was carried out as described in Materials and Methods, and percentage of area affected by inflammatory infiltration was calculated. (d) Flow cytometric analysis of IFN-γ+, IL-17A+, and Foxp3+CD25+ T cells (CD4+) in the liver. (e) Quantitative analysis of IFN-γCD4+, IL-17A+CD4+ T cells, and Foxp3+CD25+CD4+ T cells in the liver. Values are shown as mean±S.E.M. and statistical significance indicated as *P<0.05, **P<0.01, and ***P<0.001. Representative of three independent experiments; n=7–10

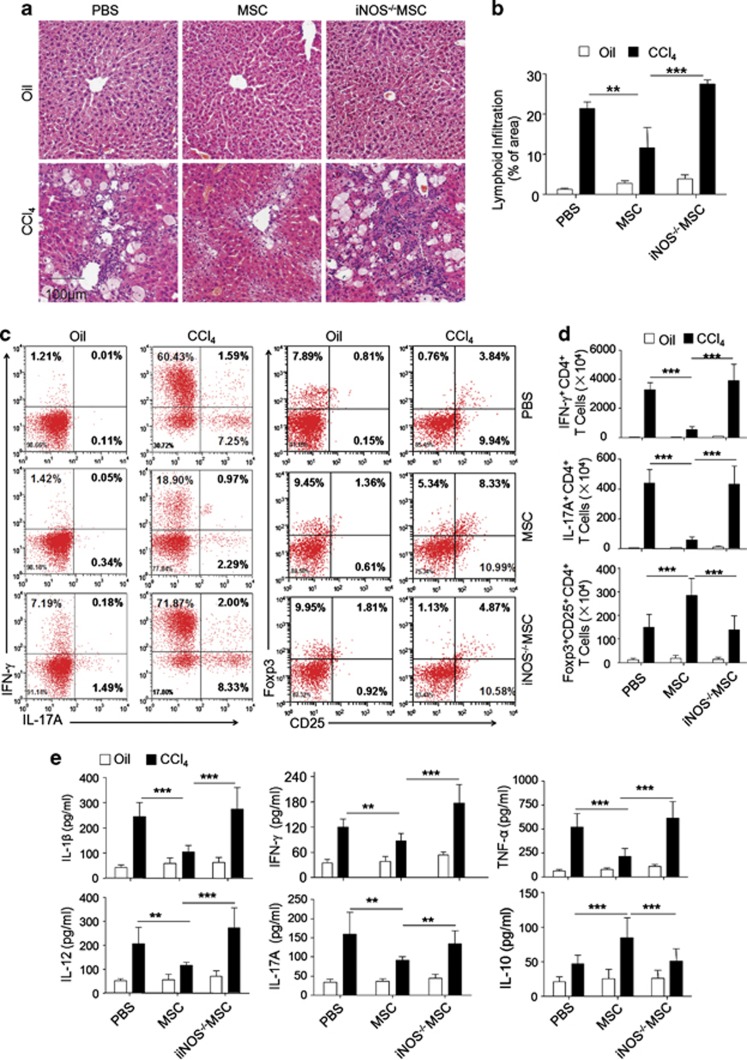

One characteristic of advanced liver fibrosis in human patients is extensive leukocyte infiltration into the liver. Indeed, we found that CCl4 administration in mice caused dramatic lymphocyte infiltration into the liver (Figures 4b and c). This leukocyte infiltration was alleviated by MSC treatment, similar to the results we achieved in the GvHD animal model.11 Further studies found that CCl4 administration induced dramatic increase of IFN-γ+CD4+ and IL-17A+CD4+T cells in mouse liver. Interestingly, these inflammatory cells in MSC-treated group were significantly reduced, whereas the proportion of Foxp3+CD25+ CD4+ T cells was increased (Figures 4d and e). Although leukocyte infiltration, especially Th1 and Th17 cells, was also reduced by Dex in CCl4-treated mice, surprisingly, concurrent administration of both Dex and MSCs reversed the reduction in the overall leukocyte infiltration (Figures 4b and c). Therefore, when Dex is used concurrently with MSCs in mice with CCl4-induced liver fibrosis, leukocyte infiltration continues unimpeded.

iNOS−/− MSCs are ineffective in treating advanced liver fibrosis in mice

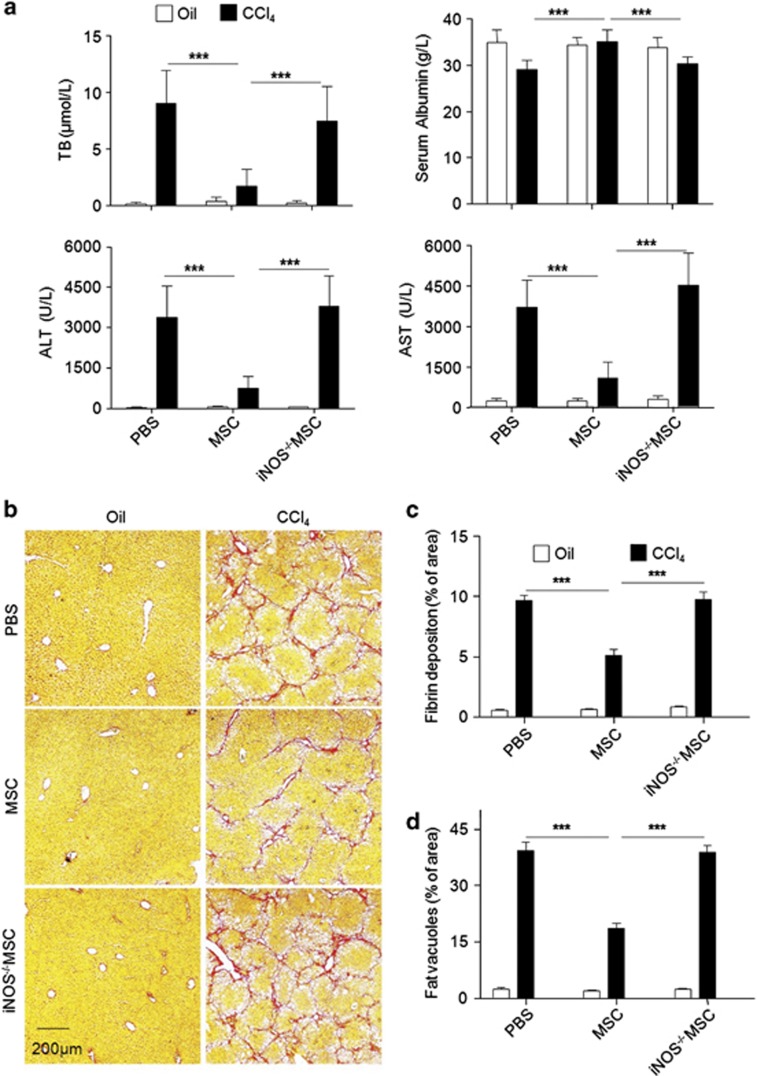

We have demonstrated that the effect of MSCs in treating liver fibrosis mouse is likely exerted by reducing inflammation. In MSCs, Dex suppressed inflammatory cytokine-induced iNOS, but not chemokines. To directly test the roles of iNOS and chemokines, we isolated MSCs from iNOS−/− mouse. On inflammatory cytokine stimulation, although these cells did not produce NO (Supplementary Figure 5), they released chemokines (CXCL10, CXCL9, CCL2, CCL5, and CXCL11) similar to that by wild-type MSCs exposed to inflammatory cytokines in the presence of Dex (Supplementary Figure 6). When iNOS−/− MSCs were administered into mice suffering from advanced liver fibrosis, these MSCs acted similar to wild-type MSCs in mice treated with Dex. iNOS−/− MSCs could not alleviate serum TB, Alb, AST, and ALT (Figure 5a). Histological analysis also showed that iNOS−/− MSCs did not improve the pathological changes (Figures 5b and c). As seen in fibrotic mice treated with wild-type MSCs plus Dex, the liver of iNOS−/− MSC-treated fibrotic mice also showed severe inflammation on histological and flow cytometric analysis (Figures 6a–d). Serum levels of inflammatory cytokines were also not altered by iNOS−/− MSCs (Figures 6e). Therefore, the expression of iNOS under inflammatory conditions is critical for MSC-induced therapeutic effects on mouse liver fibrosis.

Figure 5.

iNOS deficiency abrogated the therapeutic effects of MSCs. (a) The serum concentrations of TB, Alb, ALT, and AST in mice from each group were determined. (b) Fibrin deposition was detected by sirius red staining ( × 40 magnification, scale bar=200 μm). The liver showed extensive fibrotic development, formation of regenerative nodules, and distortion of the vascular architecture in mouse cirrhotic liver without MSCs transfusion. (c and d) Quantitative analysis of the presence of liver fibrosis and fat vacuoles. For this figure, values are shown as mean±S.E.M. and statistical significance indicated as ***P<0.001. Representative of three independent experiments; n=7–10

Figure 6.

iNOS−/− MSCs did not suppress inflammation in mice suffering from liver fibrosis. (a) Liver histological sections from each group were stained with hematoxylin and eosin ( × 100 magnification). (b) Quantitative analysis of inflammatory cell infiltration in liver sections was carried out as described in Materials and Methods, and the percentage of area affected by inflammatory infiltration was calculated. (c) Flow cytometric analysis of IFN-γ+, IL-17A+, and Foxp3+CD25+ T cells (CD4+) in the liver. (d) Quantitative analysis of IFN-γ+, IL-17A+ cells, and Foxp3+CD25+ T cells (CD4+) in the liver. (e) Serum levels of IFN-γ. TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-12, IL-17A, and IL-10 in each group were assayed by Luminex technology. For this figure, values are shown as mean±S.E.M. and statistical significance indicated as **P<0.01, and ***P<0.001. Representative of three independent experiments; n=7–10

Discussion

In recent years, great interests have developed in clinical application of tissue-derived MSCs, which are free of ethical concerns and easily expanded with minimal isolation of a wide array of tissues and body fluids. These cells are normally responsible for tissue growth, wound healing, and tissue regeneration, and likely contribute to the pathological responses in various diseases. Interestingly, a number of animal models and clinical trials have shown, with variable success, that administration of MSCs has therapeutic effects on many diseases, including multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Parkinson's disease, and spinal cord injury.26, 27 MSC therapy has also been investigated for the treatment of advanced liver fibrosis, a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. It has been reported that MSCs are capable of inducing apoptosis in collagen-producing hepatic satellite cells, supporting the survival of damaged hepatocytes in animal models,28, 29 and even differentiating into hepatocyte-like cells in mice.30 However, the efficacy of MSC-mediated therapy in clinical settings is inconsistent.20, 31, 32

Recent studies have indicated a critical role of inflammatory cytokines in eliciting the immune modulation property of MSCs, which is crucial for therapeutic effects of MSCs in various disease models and clinical setting.33 Therefore, we believe that the inflammatory status of patients may partially account for the differences in successful treatment with MSCs. Although this hypothesis had not been formally tested, previously, it was reported that concurrent treatment with CsA and MSCs accelerated rejection in a rat heart allograft model.19 Clinical studies showed that patients suffering from steroid-refractory GvHD were more amenable to MSC therapy.34 Moreover, we have demonstrated that the immunomodulatory effects of MSCs are actually elicited by inflammatory cytokines, specifically IFN-γ in the co-presence of TNF-α, IL-1α, or IL-1β.11 It is important to emphasize that without stimulation with these cytokines, MSCs do not have any immunosuppressive effect. In this study, we tested the role of inflammation in MSC-mediated therapy by employing a CCl4-induced liver fibrosis mouse model. We found that mouse bone marrow-derived MSCs could effectively improve liver function and reverse fibrin deposition. Interestingly, we found that Dex, a well-known immunosuppressant, abolished the effects of MSCs. This novel finding clearly demonstrates that MSCs must be stimulated by inflammatory cytokines to exert their therapeutic effects in vivo, at least in the context of diseases involving abnormal immune responses. Therefore, in clinical settings, MSCs should not be concurrently administered with steroid therapy.

Nevertheless, the improvement in liver function following MSC transfusion in this study could be mainly due to a reduction in inflammation in the livers, as the time for showing the therapeutic effects is too short to allow us to observe hepatocyte differentiation of MSC transfused. We found that improvement in liver function was accompanied by significant decreases in serum levels of inflammatory cytokines, such as IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-12, IL-1β, and IL-17. Meanwhile, MSC administration could reduce infiltrated T lymphocytes, especially IFN-γ+CD4+and IL-17A+CD4+ cells. However, Foxp3+CD25+CD4+ T cells in liver fibrosis mouse were increased by MSCs. Similar phenomenon has also been reported, showing that MSCs could recruit and regulate T-regulatory cells.35 We also demonstrated that Dex inhibited the production of inflammatory cytokines in fibrotic mice. Importantly, however, concurrent treatment with both Dex and MSCs did not produce additive or synergetic effects; in fact, it was quite the opposite, as T-lymphocyte infiltration persisted unchecked in fibrotic livers of mice treated with both Dex and MSCs. As shown in Figure 1, we also found the co-administration of Dex could reverse immunosuppression by MSCs. There is a dose-dependent interaction of Dex with MSCs. Among the dose range tested, we found that at 1 ng/ml, the immunosuppressive capability of MSCs was completely abolished. This result indicates that the pro-inflammatory effects of MSCs could occur when inflammatory cytokines are not sufficient. It is important to point out that MSCs could provide survival signals to lymphocytes.36 However, the mechanisms through which MSCs protect Dex-induced apoptosis in activated lymphocytes have yet to be elucidated.

In addition to its direct effects on immune cells, we found that Dex inhibited the expression of iNOS in mouse MSCs, and IDO in human MSCs, by preventing STAT1 phosphorylation. Interestingly, Dex did not affect the expression of chemokines, such as CXCL10, CXCL9, CCL2, CCL5, and CXCL11. We also observed that MSCs migrated to fibrotic livers in mice treated with Dex or MSCs, or both of them (Supplementary Figure 7). There was no significant change of the distribution of MSCs, indicating that Dex did not affect the migration of MSCs into fibrotic liver. Thus, in the presence of Dex, lymphocytes could be attracted toward fibrotic liver tissue by MSC-secreted chemokines. As Dex being metabolized, those infiltrated lymphocytes could resume proliferation and exacerbate inflammation in the fibrotic tissue. In fibrotic mice treated with both Dex and MSCs, inflammation proceeded unchecked, as indicated by serum cytokines and liver leukocyte infiltration. One possibility is that Dex inhibits iNOS expression, but not chemokine expression. To verify this hypothesis, we employed iNOS−/− MSCs, which also do not produce NO, but express chemokines on inflammatory cytokine stimulation. As shown in results, iNOS deficiency abolished the therapeutic effects of MSCs on mouse advanced liver fibrosis. In addition, IFN-γ+CD4+ cells, IL-17A+CD4+ cells, and Foxp3+CD25+CD4+ T cells also exhibited similar infiltrating patterns in the liver in mice treated with either iNOS−/− MSCs or wild-type MSCs plus Dex.

To further investigate the underlying mechanisms on the dramatic therapeutic effects of MSCs on reducing fibrin deposition, we examined the activation of myofibroblasts and activity of MMPs in mouse liver, which is believed to have critical roles in the pathogenic process of fibrogenesis.37, 38 We demonstrated that the distribution of α-SMA, a specific marker of activated hepatic stellate cells (myofibroblast), was significantly reduced after MSC transfusion in the fibrotic mouse liver,39 which was probably due to the elimination of inflammation in the liver by MSC administration. As such, MSC administration also could decrease the activities of MMP-2 effectively, which was mainly produced by hepatic stellate cells.25 Thus, these data indicated that although the production of collagen was largely inhibited by MSC transfusion, however, there is no significant change in MMP-9, which may help degrade pathological matrix, as it has been reported that MMP-9 produced by MSCs is critical for the therapeutic on liver fibrosis.21 We found that along with the alleviation of liver inflammation, MSC transfusion also promoted proliferation of the parenchymal cells in fibrotic liver labeled with BrdU, which may indicate acceleration of the improvement of liver function. As the immunosuppressive capability of MSCs was abrogated by co-administration of Dex, not surprisingly, this treatment also eliminated MSC-induced changes in α-SMA, MMPs, and parenchymal cell proliferation.

In summary, in our mouse model of advanced liver fibrosis, we found that Dex abrogated the therapeutic effects of MSCs, resulting from its ability to suppress the expression of iNOS in mouse MSCs. Therefore, MSC transfusion may be an effective clinical therapy for advanced liver fibrosis and existing inflammation-induced immunosuppression has a critical role. More importantly, concurrent treatment with steroids should be avoided in clinical practice, as it can abolish the therapeutic effect of MSCs.

Material and Methods

Mice

C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Shanghai Laboratory Animal Center of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China) and maintained under specific pathogen-free condition. Mice were maintained in the Vivarium of Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine. Animals were matched for age and gender in each experiment. All animal protocols used were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Institute of Health Sciences.

Reagents

Recombinant mouse and human IFN-γ and TNF-α, were purchased from eBioscience (La Jolla, CA, USA). CCl4 was from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd (Shanghai, China). Dex sodium phosphate was purchased from Suzhou No. 6 Pharmaceutical Factory (Suzhou, China) and methylprednisolone sodium succinate for injection was purchased from Pfizer Manufacturing Belgium NV (Puurs, Belgium).

Cells

Mouse MSCs were generated from the tibia and femur bone marrow aspirates from 6- to 10-week-old mice. Cells were cultured in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (DMEM complete medium; all from Invitrogen, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) in tissue culture flasks. Non-adherent cells were removed after 24 h and adherent cells were maintained with medium replenishment every 3 days. To obtain MSC clones, cells were collected at confluence and seeded into 96-well plates using limiting dilution. Individual clones were then picked and expanded.

Human MSCs were derived from Wharton's jelly of umbilical cords that were kindly provided by Heze Biotechnology Inc. (Beijing, China). Briefly, three blood vessels (one artery and two veins) and membrane of the umbilical cord were dissected from whole cord tissue. The exposed jelly tissue was cut into 1- to 2-mm-long pieces and tissue explants were placed in culture with low-glucose DMEM complete medium supplemented with basic fibroblast growth factor (5 ng/ml, Invitrogen). Within 1 week, when cultures were 60–70% confluent, the cells were dissociated with 0.25% Trypsin-EDTA (Invitrogen) and transferred to a new dish for further expansion. ‘Stemness' of the resulting MSCs (both mouse and human) was determined by their capability to differentiate into adipocytes, osteoblasts, and chondrocytes, and by their expression of specific cell surface markers.

Detection of cytokines and NO

Cytokine levels in serum from mice were determined by multiplexed bead immunoassay using the Luminex Technology (Bio-Plex, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). NO was detected using a modified Griess reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA). Briefly, all NO3 was converted into NO2 by nitrate reductase, and total NO2 detected by the Griess reaction.40

Cell proliferation assay

Cell proliferation was assayed by uptake of 3H-thymidine (3H-Tdr; Shanghai Institute of Applied Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai, China). Briefly, 0.5 μCi of 3H-Tdr was added to each well of a 96-well plate, the culture was continued for 4 to 6 h, and cell proliferation was terminated by freezing. Plates were then thawed, collected, and the amount of incorporated 3H-Tdr was assessed by scintillation counting (Wallac Microbeta Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA).

Mouse model of advanced liver fibrosis and treatment

We used an established mouse model of advanced liver fibrosis. Briefly, 6-week-old female C57BL/6 mice were treated semi-weekly for at least 8 weeks with intragastric administration of CCl4 (10 ml/kg, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd) dissolved in corn oil (1 : 5 ratio by volume; Sigma-Aldrich). On day 56, mice were divided into two groups: one group received daily injection of Dex (2 mg/kg, i.p.), the other received vehicle (specify) alone for 5 days. In addition, frequency of CCl4 administration was also increased to once daily in both groups in order to achieve advanced liver fibrosis. After 4 days of daily CCl4 treatment, mice showed some signs of liver failure, such as slow movement, unkempt fur, yellow urine, and jaundice. On days 60 and 61, half of the animals in each group of cirrhotic mice (with or without Dex treatment) were given transfusions of mouse bone marrow-derived MSCs twice daily (5 × 105 cells/mouse/day, i.v.), and the others received PBS. On day 63, some mice were euthanized for serum assay and flow cytometric analysis. On day 67, the remaining mice were euthanized, and the livers were collected for histological examination. All experiments used 7–10 mice per treatment group.

Isolation of liver infiltrated lymphocytes

Mouse was perfused with 10 ml PBS from the portal vein. Next, the liver was extracted and homogenized by pressing through a disposable plastic mesh (200-gauge, BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Cells were suspended in RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen). After washing twice, the cells were centrifuged at 1500 r.p.m. and resuspended in 35% percoll (GE, Björkgatan, Sweden) solution and then layered on 70% percoll followed by centrifugation at 2000 r.p.m. for 20 min at room temperature. Lymphocytes were aspirated from the interface and washed twice with RPMI 1640 medium.

Flow cytometric analysis

Cells surface markers and intracellular cytokines were stained according to the eBioscience flow cytometry protocol. Briefly, for surface staining of CD3, CD4, and CD25, cells were resuspended in PBS containing 0.5% BSA and were incubated on ice for 30 min with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies (eBioscience). After fixation and permeabilization, cells were stained, respectively, with anti-mouse IL-17A, anti-mouse IFN-γ, and anti-mouse Foxp3 antibodies conjugated with fluorochrome (eBioscience). Finally, stained cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and analyzed on a BD Caliber flow cytometer.

Real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated using RNAprep pure Cell/Bacteria Kit (Tiangen Biotech, Beijing, China). First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed using 1st cDNA Synthesis Kit with oligo (dT) 15 (Tiangen Biotech). mRNA levels of the gene of interest were quantified by real-time PCR (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) using SYBR Green Master Mix (TaKaRa Biotech, Dalian, China). The total amount of mRNA was normalized across samples according to endogenous β-actin mRNA. Sequences of PCR primer pairs were as follows: mouse CCL2, sense 5′-TCTCTCTTCCTCCACCACCATG-3′ and antisense 5′-GCGTTAACTGCATCTGGCTGA-3′ mouse CCL5, sense 5′-TTTCTACACCAGCAGCAAGTGC-3′ and antisense 5′-CCTTCGTGTGACAAACACGAC-3′ mouse CXCL9, sense 5′-AGTGTGGAGTTCGAGGAACCC T-3′ and antisense 5′-TGCAGGAGCATCGTGCATT-3′ mouse CXCL10, sense 5′-TCCTTGTCCTCCCTAGCTCA-3′ and antisense 5′-ATAACCCCTTGGGAAGATGG-3′ mouse β-actin, sense 5′-CCACGAGCGGTTCCGATG-3′ and antisense 5′-GCCACAGGA TTCCATACCCA-3′ human IDO, sense 5′-TGCCCCTGTGATAAACTGTGGT-3′ and antisense 5′-CATTCTTGTAGTCTGCTCCTCTGG-3′ human CCL2, sense 5′-CCCCAGTCACCTGCTGTTAT-3′ and antisense 5′-AGATCTCCTTGGCCACAATG-3′ human CXCL9, sense 5′-GGTTCTGATTGGAGTGCAAGGA-3′ and antisense 5′-GGATAGTCCCTTGGTTGGTGCT-3′ human CXCL10, sense 5′-GCCAATTTTGTCCACGTGTTG-3′ and antisense 5′-GGCCTTCGATTCTGGATTCAG-3′ human CXCL11, sense 5′-CCTTGGCTGTGATATTGTGTGC-3′ and antisense 5′-CCTATGCAAAGACAGCGTCCT-3′ human β-actin, sense, 5′-CGTACCACTGGCATCGTGAT-3′. All primers were synthesized by Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China).

Western blotting

Mouse or human protein samples in SDS sample buffer were heated to 95 °C for 10 min and separated on SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Resolved proteins were then electroblotted onto nitrocellulose membranes and probed with antibody against iNOS, STAT-1, phospho-STAT1, IDO, or β-actin overnight at 4 °C. The antibodies were as follows: rat anti-mouse iNOS (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Danvers, MA, USA), rat-anti human/mouse STAT1 (Cell Signaling), rat anti-human/mouse phospho-STAT1 (Cell Signaling), mouse anti-human IDO (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), and mouse anti-β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich). These were followed by secondary antibodies HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG or HRP-conjugated anti-rat IgG (Cell Signaling), and visualized by chemiluminescent detection according to the manufacturer's instructions (Immobilon western chemiluminescent HRP substrate, Millipore).

Immunohistochemistry

For histological examination, mouse livers were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight, embedded in paraffin, and 4 μm sections were cut and stained with hematoxylin–eosin and sirius red according to the manufacturer's protocol. Mouse α-SMA was stained using anti-α-SMA (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) followed by HRP-conjugated rat anti-mouse secondary antibody (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA), and visualized using the DAB Peroxidase Substrate Kit (Maixin Bio, Fuzhou, China). The distribution of α-SMA was also determined by computer-assisted image analysis with software, NIS-Elements BR 3.1 (Nikon Instruments, Shanghai, China) similarly determined, which was expressed as the percentage of the α-SMA-labeled areas in four or five random low power ( × 10) microscope fields.

GFP expression in liver sections was localized using rabbit anti-GFP (Abcam) followed by goat anti-rabbit coupled to DyLight594 (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA). Cell nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich). Stained sections were examined by fluorescence microscopy.

Quantitative analysis of liver pathological changes

The extent of liver fibrosis, lipoid degeneration, and leukocyte infiltration were quantified after stained with sirius red and hematoxylin–eosin microscope (Nikon Instruments), as described previously.21 The percentage of area affected by fibrosis, fat vacuoles, and leukocyte infiltration was determined at five randomly selected areas per sample and averaged by computer-assisted image analysis with a software, NIS-Elements BR 3.1 (Nikon Instruments).

Nuclear BrdU incorporation

To determine the proliferation of parenchymal cells in mouse liver, BrdU (Sigma-Aldrich) was injected i.p. at a dose of 50 mg/kg body weight. After 2 h, mice were euthanized, and the livers were collected and prepared for immunohistochemical detection of nuclear BrdU incorporation. To detect BrdU, liver sections were stained with anti-BrdU followed by HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (both from Sigma-Aldrich), and chromogenic detection using AEC Peroxidase Substrate Kit (Maixin Bio). The frequency of BrdU-labeled hepatocytes was determined by counting positively stained hepatocyte nuclei in four or five random low-power ( × 10) microscope fields using computer-assisted image analysis (NIS-Elements BR 3.1, Nikon Instruments).

MMP enzymatic activity assay

The activities of MMP-2 and MMP-9 in mouse liver tissue were examined using commercial kits (Tissue Active MMP-2 Fluorescent Assay kit and Tissue Active MMP-9 Fluorescent Assay kit, respectively; Genmed Scientific, Inc., Wilmington, DE, USA). Relative fluorescence intensity was determined spectrophotometrically using an excitation wavelength of 330 nm and an emission wavelength of 400 nm. Consistency of the fluorescent polypeptide segments was calculated on the basis of the relative fluorescence units; MMP-2 and MMP-9 activities were expressed as nmol/mg/min.

Statistical analysis

Parameters from treatment groups were compared statistically using unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test. Significance was expressed as: *P<0.05, **P<0.01, and ***P<0.001.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Scientific Innovation Project of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA01040000) and the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2010CB945600 and 2011DFA30630).

Glossary

- MSC

mesenchymal stem cell

- NO

nitric oxide

- Dex

dexamethasone

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- IDO

indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase

- GvHD

graft-versus-host disease

- α-SMA

α-smooth muscle actin

- MMP-2

matrix metalloproteinase-2

- MMP-9

matrix metalloproteinase-9

- IFN-γ

interferon-γ

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor-α

- IL-1β

interleukin-1β

- IL-12

interleukin-12

- IL-17

interleukin-17

- TB

total bilirubin

- Alb

albumin

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Cell Death and Disease website (http://www.nature.com/cddis)

Edited by G Melino

Supplementary Material

References

- Yoshimura K, Shigeura T, Matsumoto D, Sato T, Takaki Y, Aiba-Kojima E, et al. Characterization of freshly isolated and cultured cells derived from the fatty and fluid portions of liposuction aspirates. J Cell Physiol. 2006;208:64–76. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HS, Hung SC, Peng ST, Huang CC, Wei HM, Guo YJ, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells in the Wharton's jelly of the human umbilical cord. Stem Cells. 2004;22:1330–1337. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toma JG, Akhavan M, Fernandes KJ, Barnabe-Heider F, Sadikot A, Kaplan DR, et al. Isolation of multipotent adult stem cells from the dermis of mammalian skin. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:778–784. doi: 10.1038/ncb0901-778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Ott L, Seshareddy K, Weiss ML, Detamore MS. Musculoskeletal tissue engineering with human umbilical cord mesenchymal stromal cells. Regen Med. 2011;6:95–109. doi: 10.2217/rme.10.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Blanc K, Frassoni F, Ball L, Locatelli F, Roelofs H, Lewis I, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells for treatment of steroid-resistant, severe, acute graft-versus-host disease: a phase II study. Lancet. 2008;371:1579–1586. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60690-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Wang D, Liang J, Zhang H, Feng X, Wang H, et al. Umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in severe and refractory systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:2467–2475. doi: 10.1002/art.27548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Olmo D, Garcia-Arranz M, Herreros D, Pascual I, Peiro C, Rodriguez-Montes JA. A phase I clinical trial of the treatment of Crohn's fistula by adipose mesenchymal stem cell transplantation. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1416–1423. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0052-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RH, Pulin AA, Seo MJ, Kota DJ, Ylostalo J, Larson BL, et al. Intravenous hMSCs improve myocardial infarction in mice because cells embolized in lung are activated to secrete the anti-inflammatory protein TSG-6. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamout B, Hourani R, Salti H, Barada W, El-Hajj T, Al-Kutoubi A, et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in patients with multiple sclerosis: a pilot study. J Neuroimmunol. 2010;227:185–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones J, Jaramillo-Merchan J, Bueno C, Pastor D, Viso-Leon M, Martinez S. Mesenchymal stem cells rescue Purkinje cells and improve motor functions in a mouse model of cerebellar ataxia. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;40:415–423. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren G, Zhang L, Zhao X, Xu G, Zhang Y, Roberts AI, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-mediated immunosuppression occurs via concerted action of chemokines and nitric oxide. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren G, Su J, Zhang L, Zhao X, Ling W, L'Huillie A, et al. Species variation in the mechanisms of mesenchymal stem cell-mediated immunosuppression. Stem Cells. 2009;27:1954–1962. doi: 10.1002/stem.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karkhanis J, Verna EC, Chang MS, Stravitz RT, Schilsky M, Lee WM, et al. Steroid use in acute liver failure Hepatology 2013. e-pub ahead of print 8 August 2013 doi: 10.1002/hep.26678 [DOI]

- Almalki DM, Al-Suwaidan FB. Steroid pulse therapy in herpes simplex encephalitis. Neurosciences (Riyadh) 2013;18:276–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soloway RD, Hewlett AT. The medical treatment for autoimmune hepatitis through corticosteroid to new immunosuppressive agents: a concise review. Ann Hepatol. 2007;6:204–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucala R. Approaching the immunophysiology of steroid resistance. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14:118. doi: 10.1186/ar3820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy D, Little FF. Steroid resistant asthma: more than meets the eye. J Asthma. 2013;50:1036–1044. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2013.831870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu KH, Chan CK, Tsai C, Chang YH, Sieber M, Chiu TH, et al. Effective treatment of severe steroid-resistant acute graft-versus-host disease with umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Transplantation. 2011;91:1412–1416. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31821aba18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue S, Popp FC, Koehl GE, Piso P, Schlitt HJ, Geissler EK, et al. Immunomodulatory effects of mesenchymal stem cells in a rat organ transplant model. Transplantation. 2006;81:1589–1595. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000209919.90630.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker M.Stem-cell drug fails crucial trials Nature 2009. Available at http://www.nature.com/news/2009/090909/full/news.2009.894.html .

- Sakaida I, Terai S, Yamamoto N, Aoyama K, Ishikawa T, Nishina H, et al. Transplantation of bone marrow cells reduces CCl4-induced liver fibrosis in mice. Hepatology. 2004;40:1304–1311. doi: 10.1002/hep.20452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Lin H, Shi M, Xu R, Fu J, Lv J, et al. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells improve liver function and ascites in decompensated liver cirrhosis patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27 (Suppl 2:112–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.07024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue F, Takahara T, Yata Y, Kuwabara Y, Shinno E, Nonome K, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor gene therapy accelerates regeneration in cirrhotic mouse livers after hepatectomy. Gut. 2003;52:694–700. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.5.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Ren G, Huang Y, Su J, Han Y, Li J, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells: a double-edged sword in regulating immune responses. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19:1505–1513. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2012.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preaux AM, Mallat A, Nhieu JT, D'Ortho MP, Hembry RM, Mavier P. Matrix metalloproteinase-2 activation in human hepatic fibrosis regulation by cell-matrix interactions. Hepatology. 1999;30:944–950. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uccelli A, Moretta L, Pistoia V. Mesenchymal stem cells in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:726–736. doi: 10.1038/nri2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner J, Kean T, Young R, Dennis JE, Caplan AI. Optimizing mesenchymal stem cell-based therapeutics. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2009;20:531–536. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao DC, Lei JX, Chen R, Yu WH, Zhang XM, Li SN, et al. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells protect against experimental liver fibrosis in rats. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:3431–3440. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i22.3431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Hu G, Su J, Li W, Chen Q, Shou P, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells: a new strategy for immunosuppression and tissue repair. Cell Res. 2010;20:510–518. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao XR, Li WL, Su J, Jin CX, Wang XM, Li JX, et al. Clonal mesenchymal stem cells derived from human bone marrow can differentiate into hepatocyte-like cells in injured livers of SCID mice. J Cell Biochem. 2009;108:693–704. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrion F, Nova E, Ruiz C, Diaz F, Inostroza C, Rojo D, et al. Autologous mesenchymal stem cell treatment increased T regulatory cells with no effect on disease activity in two systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Lupus. 2010;19:317–322. doi: 10.1177/0961203309348983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duijvestein M, Vos AC, Roelofs H, Wildenberg ME, Wendrich BB, Verspaget HW, et al. Autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cell treatment for refractory luminal Crohn's disease: results of a phase I study. Gut. 2010;59:1662–1669. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.215152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren G, Chen X, Dong F, Li W, Ren X, Zhang Y, et al. Concise review: mesenchymal stem cells and translational medicine: emerging issues. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2012;1:51–58. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2011-0019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wernicke CM, Grunewald TG, Juenger H, Kuci S, Kuci Z, Koehl U, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells for treatment of steroid-refractory GvHD: a review of the literature and two pediatric cases. Int Arch Med. 2011;4:27. doi: 10.1186/1755-7682-4-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Ianni M, Del Papa B, De Ioanni M, Moretti L, Bonifacio E, Cecchini D, et al. Mesenchymal cells recruit and regulate T regulatory cells. Exp Hematol. 2008;36:309–318. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu G, Zhang Y, Zhang L, Ren G, Shi Y. The role of IL-6 in inhibition of lymphocyte apoptosis by mesenchymal stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;361:745–750. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.07.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassiman D, Libbrecht L, Desmet V, Denef C, Roskams T. Hepatic stellate cell/myofibroblast subpopulations in fibrotic human and rat livers. J Hepatol. 2002;36:200–209. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(01)00260-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han YP. Matrix metalloproteinases, the pros and cons, in liver fibrosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21 (Suppl 3:S88–S91. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04586.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinz B, Dugina V, Ballestrem C, Wehrle-Haller B, Chaponnier C. Alpha-smooth muscle actin is crucial for focal adhesion maturation in myofibroblasts. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:2508–2519. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-11-0729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda KM, Espey MG, Wink DA. A rapid, simple spectrophotometric method for simultaneous detection of nitrate and nitrite. Nitric Oxide. 2001;5:62–71. doi: 10.1006/niox.2000.0319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.