Abstract

Despite the importance of platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1, CD31) in the adhesion and diapedesis of monocytes/lymphocytes, little is known about the mechanisms by which it is regulated. We explored the role of a glycosphingolipid, lactosylceramide (LacCer), in modulating PECAM-1 expression and cell adhesion in human monocytes. We observed that LacCer specifically exerted a time-dependent increase in PECAM-1 expression in U-937 cells. Maximal increase in PECAM-1 protein occurred after incubation with LacCer for 60 min. LacCer activated PKCα and -ε by translocating them from cytosol to membrane. This was accompanied by the activation of phospholipase A2 (PLA2) and the increase of cell adhesion, which were abrogated by chelerythrine chloride, 2-[1-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-1H-indol-3-yl]-3-(1H-indol-3-yl)-maleimide and 12-(2-cyanoethyl)-6,7,12,13-tetrahydro-13-methyl-5-oxo-5H-indolo(2,3-a)pyrrolo(3,4-c)-carbazole (GÖ 6976) (PKC inhibitors). Similarly, bromoenol lactone (a Ca2+-independent PLA2 inhibitor) and methyl arachidonyl fluorophosphonate (an inhibitor of cytosolic PLA2 and Ca2+-independent PLA2) inhibited LacCer-induced PLA2 activity. Bromophenacyl bromide (a PLA2 inhibitor) abrogated LacCer-induced PECAM-1 expression, and this was bypassed by arachidonic acid. Furthermore, the arachidonate-induced up-regulation of PECAM-1 was abrogated by indomethacin [a cyclooxygenase (COX)-1 and -2 inhibitor] or N-[2-(cyclohexyloxy)-4-nitrophenyl]-methanesulfonamide (a COX-2 inhibitor) but not nordihydroguaiaretic acid (a lipoxygenase inhibitor). In sum, PKCα/ε are the primary targets for the activation of LacCer. Downstream activation of intracellular Ca2+-independent PLA2 and/or cytosolic PLA2 results in the production of arachidonic acid, which in turn serves as a precursor for prostaglandins that subsequently stimulate PECAM-1 expression and cell adhesion. These findings may be relevant in explaining the role of LacCer in the regulation of PECAM-1 and related pathophysiology.

Platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1, CD31), a member of the Ig superfamily, is located on the surface of human vascular endothelial cell junctions as well as in platelets, neutrophils, subsets of lymphocytes, and monocytes. PECAM-1 is constitutively expressed in human endothelial cells, and its level is modulated by macrophage colony-stimulating factor (1) and vascular endothelial growth factor (2). A soluble form of PECAM-1 (sPECAM-1) devoid of the transmembrane domain is shed in blood. An increased sPECAM-1 level has been reported in severe congestive heart failure (3) and acute myocardial infarction in patients with chest pain (4). A decreased sPECAM-1 level was reported in the plasma of patients with cancer (5). Although PECAM-1 has been implicated in the adhesion and transendothelial migration of monocytes/lymphocytes (6), little is known about mechanisms by which this molecule is regulated.

Lactosylceramide (LacCer) is one of the ubiquitous glycosphingolipids found in eukaryotic cells (7) and is emerging as a novel lipid second messenger in mediating tumor necrosis factor-α, platelet-derived growth factor, and oxidized low-density lipoprotein-induced phenotypic changes in cells of the vascular wall such as cell proliferation (8, 9) and cell adhesion (10). Elevated levels of LacCer have been reported in the plasma of patients with familial hypercholesterolemia (11) and, most interestingly, in calcified or uncalcified plaque intima from the aorta of patients who died of cardiovascular disease (12).

Previously, studies of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) have shown that tumor necrosis factor α recruits a β-1,4 galactosyltransferase, LacCer synthase, to increase the level of LacCer. In turn, this newly generated LacCer recruited an “oxygen-sensitive” signal transduction cascade involving the activation of NADPH oxidase and NF-κB that contributed to increased expression of intercellular cell adhesion molecule (ICAM-1) and increased adhesion of neutrophils to HUVECs (13). This phenotypic change was abrogated by the preincubation of cells with d-1-phenyl-2-decanoylamino-3-morpholino-1-propanol, a nonspecific inhibitor of glycosphingolipid galactosyltransferase (12), and specifically this was bypassed by LacCer. Therefore, we rationalized that LacCer may also recruit the signaling cascade above to alter the expression of PECAM-1 in human monocytes. Our studies reveal that human monocytes do not recruit the oxygen-sensitive signaling cascade above to increase the level of PECAM-1. Rather, in human U-937 cells, LacCer activated PKC isozymes α and ε and stimulated the activity of intracellular Ca2+-independent phospholipase A2 (iPLA2) and/or cytosolic Ca2+-dependent PLA2 (cPLA2). Arachidonic acid released as a consequence of this reaction produces prostaglandins that subsequently increase PECAM-1 expression and adhesion of monocytes to endothelial cells.

Materials and Methods

Bovine brain LacCer (95% pure), digalactosyl diglyceride (D4561), and most chemicals used in this study were purchased from Sigma. LacCer from bovine milk (>98% pure) and palmitoyl LacCer (≈98% pure) were purchased from Matreya (Pleasant Gap, PA). Methyl arachidonyl fluorophosphonate, 2-[1-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-1H-indol-3-yl]-3-(1H-indol-3-yl)-maleimide (GÖ 6850) and 12-(2-cyanoethyl)-6,7,12,13-tetrahydro-13-methyl-5-oxo-5H-indolo(2,3-a)pyrrolo(3,4-c)-carbazole (GÖ 6976) were purchased from Calbiochem. 3-(3-Acetamide 1-benzyl-2-ethylindolyl-5-oxy) propanesulfonic acid (LY311727) was a gift from Lilly Research Laboratories (Indianapolis). [5,6,8,9,11,12,14,15–3H(N)] arachidonic acid [60–100 Ci (2.22–3.70 TBq)/mmol] was obtained from Perkin–Elmer. N-[2-(P-bromocinnamylamino)ethyl]-5-iso-quinoline-sulfonamide was purchased from ICN. Indomethacin, N-[2-(cyclohexyloxy)-4-nitrophenyl]-methanesulfonamide), and nordihydroguaiaretic acid were purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). Dihydro LacCer was prepared by using bovine LacCer by Pd2+-catalyzed reduction and purified by high-performance thin-layer chromatography/HPLC techniques.

The details for the following methods are described in Supporting Methods, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site: cell culture; membrane and cytosol fractionation; Western immunoblot analysis; semiquantitative RT-PCR; measurement of PL A2 activity; and adhesion of U-937 cells to HUVECs.

Results

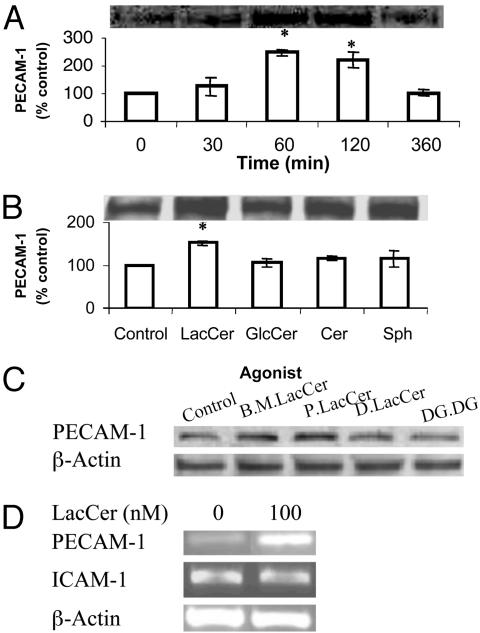

LacCer Increases PECAM-1 Expression Level in U-937 Cells. The effect of LacCer on the expression level of PECAM-1 in U-937 cells was determined in the absence and presence of various concentrations of LacCer (Sigma) for different periods of time by the use of Western immunoblot analysis. The maximal increase of PECAM-1 in cells was observed after incubation with 100 nM LacCer for 1 h. The PECAM-1 level returned to a basal level after 360 min of treatment (Fig. 1A). LacCer had no cytotoxicity to cells based on the trypan blue exclusion test.

Fig. 1.

Effect of 100 nM bovine brain LacCer (Sigma) (A), its metabolites (B), and bovine milk (B.M.) LacCer, palmitoyl LacCer (Matreya; P.LacCer), dihydro LacCer (D.LacCer), and digalactosyl diglyceride (DG.DG.) (C) on PECAM-1 protein expression in U-937 cells. Western immunoblot analysis and densitometric scanning of PECAM-1 level in cells in serum-free RPMI medium 1640, treated with indicated agonists for indicated periods of time in A, and for 1 h in B and C. (D) Effect of LacCer on PECAM-1 and ICAM-1 mRNA transcription in U-937 cells. Total RNA was extracted from cells (1 × 107) incubated with 100 nM LacCer for 1 h and an equal amount of total RNA was subjected to semiquantitative RT-PCR. β-Actin served as an internal control to verify the equal amount of total cDNA used for each sample (P < 0.05 vs. control).

LacCer Specifically Stimulates PECAM-1 in U-937 Cells. To determine whether the up-regulation of PECAM-1 in U-937 cells was produced by LacCer itself or by its metabolites, we treated cells with 100 nM LacCer and its metabolites such as GlcCer, Cer, and sphingosine (Fig. 1B). Only LacCer itself increased the PE-CAM-1 expression level significantly, whereas its metabolites did not. Our additional studies revealed that LacCer from bovine milk and l-palmitoyl LacCer (Matreya) also stimulated PE-CAM-1 protein expression in U-937 cells, whereas other structurally related molecules such as dihydro LacCer and digalactosyl diglyceride did not (Fig. 1C).

LacCer Increases the Transcription of PECAM-1 in U-937 Cells. Using a semiquantitative RT-PCR-based assay, we observed that 1-h incubation of cells with 100 nM LacCer significantly increased the PECAM-1 mRNA level (relative to β-actin) in U-937 cells (Fig. 1D). However, this up-regulation was not observed in the mRNA level of ICAM-1 (Fig. 1D).

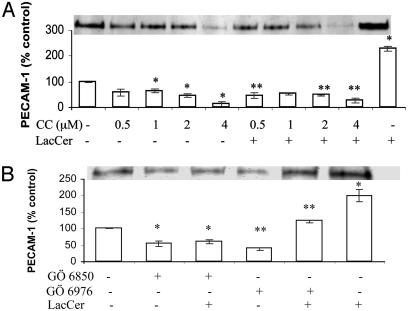

LacCer-Mediated Up-Regulation of PECAM-1 Requires PKCα and -ε. We observed that the PKC inhibitor chelerythrine chloride decreased the endogenous level of PECAM-1 as compared with the control. No recovery of inhibition in PECAM-1 expression mediated by chelerythrine chloride was observed on feeding the cells LacCer (Fig. 2A). Staurosporine but not N-[2-(P-bromocinnamylamino)ethyl]-5-iso-quinolinesulfonamide, a PKA inhibitor, inhibited PECAM-1 expression in U-937 cells (data not shown). These results suggest that the up-regulation of PECAM-1 by LacCer is PKC-but not PKA-dependent. Moreover, LacCer-mediated induction of PECAM-1 does not require a PKC-independent pathway.

Fig. 2.

Effect of PKC inhibitors chelerythrine chloride (CC; A) and GÖ 6976 and GÖ 6850 (B) on LacCer-mediated PECAM-1 protein expression in U-937 cells. Western immunoblot analysis and densitometric scanning of PECAM-1 in cells treated with various concentrations of chelerythrine chloride (CC) for 2 h (A) and 10 nM GÖ 6976 or GÖ 6850 for3h(B) followed with and without 100 nM LacCer for 1 h. *, P < 0.05 vs. control; **, P < 0.05 vs. LacCer; n = 3.

To determine which isozymes of PKC were involved in LacCer-mediated PECAM-1 up-regulation, the effect of the inhibitors GÖ 6976 (specific for PKCα and -β) and GÖ 6850 (selective for PKCα, -β, -γ, -ε, and -δ) on PECAM-1 expression in U-937 cells with and without treatment with LacCer was studied. As shown in Fig. 2B, the inhibitory effect of GÖ 6976 on the PECAM-1 basal level was bypassed by the addition of LacCer as compared with the control. This result suggested that other PKC isozymes in addition to α or β were also involved in the LacCer-stimulated PECAM-1 level. As a further proof, the inhibitory effect of GÖ 6850 could not be bypassed by the addition of LacCer, which also suggested that the isozymes recruited by LacCer should be among the ones inhibited by GÖ 6850. In sum, PKC isozymes such as α and/or β and ε and/or δ/γ might be involved in the up-regulation of PECAM-1 in U-937 cells induced by LacCer.

The expression profile of PKC isozymes was investigated in U-937 cells treated with and without LacCer by Western immunoblot analysis. PKC isozymes α, β, ε, δ, ζ, ι, and λ were detected in U-937 cells (in Fig. 8, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). However, their expression levels were not altered in U-937 cells treated with LacCer. Therefore, the role of PKC in the LacCer-stimulated upregulation of PECAM-1 was not mediated through the increased synthesis of particular isozymes of PKC. Instead, it was due to the activation of corresponding PKC isozymes (Fig. 2).

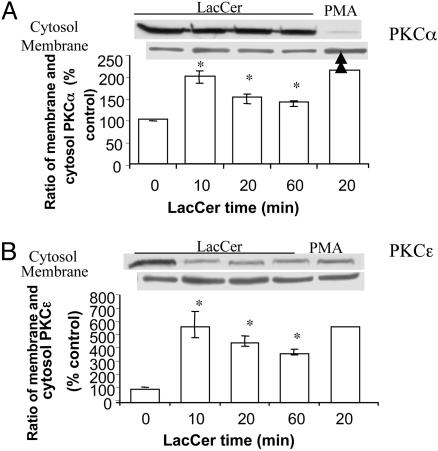

To further confirm which PKC isozymes were involved in LacCer-induced PECAM-1 up-regulation, experiments on membrane translocation of PKC isozymes were carried out.

In untreated U-937 cells, PKCα, -β, and -ε were mainly distributed in cytosol, whereas PKCδ, -ζ, -ι, and -λ were mainly distributed in membrane (data not shown). Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate, an activator of both conventional and novel PKC isozymes (14), induced the translocation of α and ε (Fig. 3 A and B) and β and δ (data not shown) from cytosol to membrane. Detailed kinetics of LacCer-induced PKC translocation showed that LacCer led to membrane translocation of PKC isozymes α and ε (Fig. 3 A and B, respectively) with a peak time of 10-min incubation. However, LacCer had no effect on the membrane translocation of PKC isozymes β, δ, ζ, ι, and λ (data not shown). This result could serve as evidence that PKCα and -ε were activated/translocated to a membrane induced by LacCer and thus resulted in PECAM-1 upregulation in U-937 cells.

Fig. 3.

Membrane and cytosol distribution of PKC isozymes α (A) and ε (B)in U-937 cells. Western immunoblot analysis and densitometric scanning of PKCα and -ε in membrane and cytosol of cells treated with and without 100 nM LacCer for the indicated time in serum-free RPMI medium 1640. Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate treatment (0.1 μM, 20 min) of U-937 cells served as a positive control. *, P < 0.05 vs. control; n = 3.

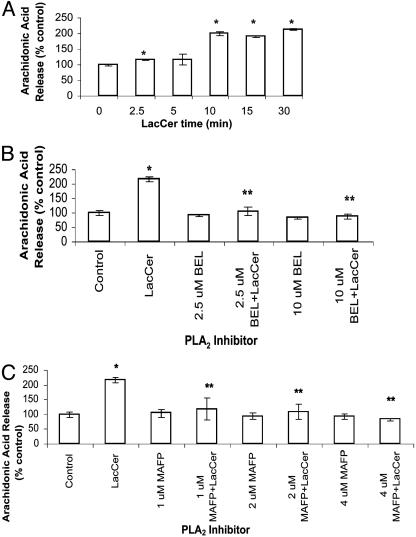

LacCer Activates PLA2 in U-937 Cells in a Time-Dependent Manner. Because phosphorylation of PLA2 by PKC enhances its activity (15) and PKC was involved in LacCer-mediated up-regulation of PECAM-1, the question was raised whether PLA2 was also involved in this process in human monocytes. As shown in Fig. 4A, in U-937 cells, LacCer (100 nM) increased the activity of PLA2 significantly, 2-fold in 10 min, and this was sustained for up to 30 min.

Fig. 4.

(A) LacCer activates PLA2 in U-937 cells in a time-dependent manner. Cells (1 × 106) were labeled with [3H]arachidonic acid for 30 min, washed with serum-free HBSS serially four times, and then incubated with 100 nM LacCer for various time points (0, 2.5, 5, 10, 15, and 30 min). Next, radioactivity in the supernatant was measured. (B and C) PLA2 inhibitors abrogate increased arachidonic acid release from LacCer-treated [3H]arachidonic acid-labeled U-937 cells. [3H]arachidonic acid-labeled U-937 cells were treated with various concentrations of iPLA2 inhibitor bromoenol lactone (BEL; 2.5 and 10 μM) (B), iPLA2 and cPLA2 inhibitor methyl arachidonyl fluorophosphonate (MAFP; 1, 2, and 4 μM) (C) for 30 min at 37°C, followed with and without 100 nM LacCer for 30 min. Data represent mean ± SD of three different experiments in duplicates. *, P < 0.05 vs. control; **, P < 0.05 vs. LacCer.

PLA2 Inhibitors Block the Increased Release of [3H]Arachidonic Acid in LacCer-Treated U-937 Cells. PLA2 can be classified into three types based on their biological properties: secretory PLA2 (sPLA2), cPLA2, and iPLA2. Fig. 4B shows that preincubation of U-937 cells with bromoenol lactone, a specific inhibitor of iPLA2, completely inhibited the LacCer-induced increase in PLA2 activity. Similarly, methyl arachidonyl fluorophosphonate, an inhibitor of cPLA2 and iPLA2, also decreased a LacCer-induced increase in PLA2 activity (Fig. 4C). However, LY311727, a specific inhibitor of sPLA2, did not decrease a LacCer-induced increase in PLA2 activity (data not shown).

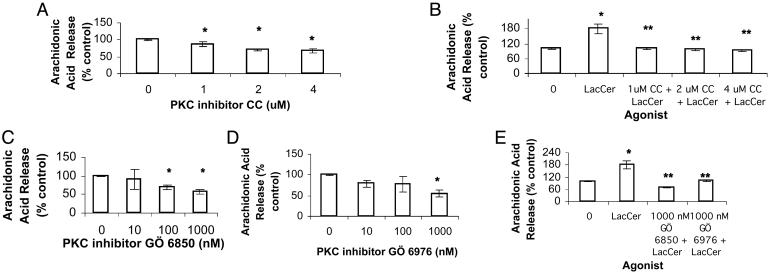

PKC Inhibitors Abrogate LacCer-Mediated PLA2 Activation. Chelerythrine chloride exerted a concentration-dependent decrease in PLA2 activity (Fig. 5A) as well as LacCer-inducible PLA2 activity (Fig. 5B). Similarly, GÖ 6850 and GÖ 6976 also inhibited PLA2 activity (Fig. 5 C and D, respectively) as well as LacCer-inducible PLA2 activity in U-937 cells (Fig. 5E).

Fig. 5.

PKC inhibitors abrogate LacCer-mediated PLA2 activation. Arachidonic acid release assay was done. [3H]Arachidonic acid-labeled U-937 cells were treated with chelerythrine chloride (CC) (A and B), GÖ 6850 and GÖ 6976 (C–E) for 30 min followed with and without 100 nM LacCer for 30 min at 37°C. Data represent mean ± SD of three different experiments in duplicates. *, P < 0.05 vs. control; **, P < 0.05 vs. LacCer.

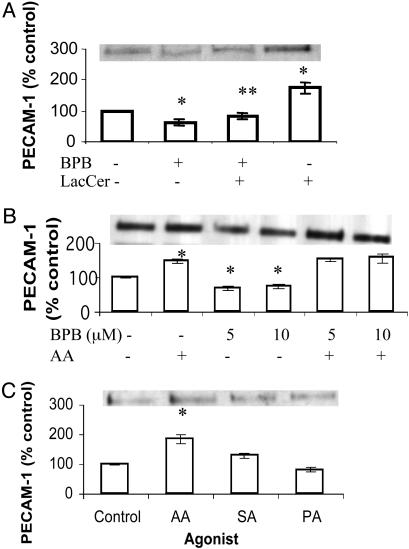

PLA2 Inhibitor Inhibits LacCer-Induced PECAM-1 Protein Expression, and This Can Be Bypassed by Arachidonic Acid. As shown in Fig. 6A, bromophenacyl bromide (BPB) (an inhibitor of PLA2), had an inhibitory effect on PECAM-1 protein expression, which could be bypassed by arachidonic acid (Fig. 6B) but not LacCer. Other fatty acid constituents of LacCer such as palmitic acid and stearic acid did not significantly alter the PECAM-1 level in U-937 as did arachidonic acid (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

Effect of PLA2 inhibitor BPB (A), arachidonic acid (AA; B), and other fatty acids (C) on PECAM-1 protein expression in U-937 cells. Western immunoblot analysis and densitometric scanning of PECAM-1 in cells treated with 100 nM LacCer for 1 h with and without pretreatment with 10 μM BPB for 30 min (A), 10 μM AA for 1 h with and without pretreatment with BPB for 30 min (B), 10 μM AA, stearic acid (SA), and palmitic acid (PA) for 1 h (C). *, P < 0.05 vs. control; **, P < 0.05 vs. LacCer; n = 3.

Arachidonic Acid Up-Regulates PECAM-1 Through Its Product Prostaglandins. Arachidonic acid is converted to leukotrienes and prostaglandins via the action of lipoxygenase (LOX) and cyclo-oxygenase (COX), respectively. We therefore used the inhibitors of LOX and COX to determine whether arachidonic acid itself or its metabolites above regulates PECAM-1. Nordihydroguaiaretic acid, an inhibitor of LOX, did not inhibit the up-regulation of PECAM-1 induced by arachidonic acid in cells (Fig. 9A, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). On the contrary, N-[2-(cyclohexyloxy)-4-nitrophenyl]-methane-sulfonamide, a specific inhibitor of COX-2, as well as indomethacin, a nonselective inhibitor of COX-1 and -2, both abrogated arachidonic acid-induced PECAM-1 up-regulation in U-937 cells (Fig. 9B). These results may suggest that prostaglandins generated by the action of COX-1 and -2 up-regulate PECAM-1 in U-937 cells.

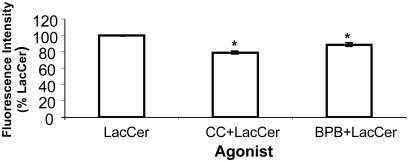

LacCer-Mediated Increase in Cell Adhesion Is Abrogated by PKC and PLA2 Inhibitors in U-937 Cells. LacCer (100 nM) stimulated cell adhesion, and this was abrogated by preincubation of cells with PLA2 inhibitor and PKC inhibitor BPB and chelerythrine chloride, respectively (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

LacCer-mediated increase in cell adhesion is abrogated by PKC inhibitor and PLA2 inhibitor. U-937 cells were treated with 100 nM LacCer with and without PKC inhibitor chelerythrine chloride (CC; 4 μM) and PLA2 inhibitor BPB (5 μM) for 1 h. Adhesion of each category of U-937 cells to HUVECs was done as described in Supporting Methods. Triplicates were used for each treatment. The average fluorescence intensity for the group treated with 100 nM LacCer was 664.5 ± 4.2. It was significantly higher than that of the control (595.5 ± 1.4). Data were plotted by using the fluorescence intensity of LacCer as 100% and represent mean ± SD of two independent experiments. *, P < 0.05 vs. LacCer.

Discussion

Our studies revealed the following findings. First, LacCer specifically stimulated PECAM-1 at both the translation and transcription levels in human promonocytic cell line U-937. Second, LacCer recruited PKC isozymes α and ε to increase the expression of PECAM-1. Third, PLA2 activation depending on PKC activation by LacCer and arachidonic acid produced increased PECAM-1 expression. Fourth, our observation that COX-1 and -2 inhibitors abrogated arachidonic acid-induced PECAM-1 expression suggests that prostaglandins may well mediate PE-CAM-1 expression in monocytes. Finally, LacCer increased the adhesion of monocytes to human endothelial cells. The biochemical mechanism above by which LacCer may stimulate PECAM-1 expression in U-937 cells and adhesion to endothelial cells is summarized in Fig. 10, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site.

PECAM-1 is an important molecule involved in homotypic and heterotypic adhesion and transendothelial migration as well as signaling pathways. Although its cDNA (16) and gene (17) as well as protein structure (18) have been well documented, there have been very few reports on regulation at the transcription (19, 20) and translation levels. Previous studies have shown that in HUVECs, tumor necrosis factor-α can induce LacCer synthesis and in turn LacCer increased ICAM-1 at the transcription and translation levels (13). Our studies with U-937 cells revealed that LacCer increased the level of PECAM-1 protein expression in a dose- and time-dependent manner. The stimulation of PE-CAM-1 by LacCer was also observed at the mRNA level. This stimulation was PECAM-1-specific, because LacCer did not increase the mRNA level of ICAM-1 in U-937 cells.

Moreover, digalactosyl diglyceride and dihydro LacCer did not increase PECAM-1 protein expression in U-937 cells (Fig. 1C), whereas LacCer from three different sources did (Fig. 1 A and C). The differences in PECAM-1 expression in the use of bovine brain LacCer, bovine milk LacCer, or palmitoyl LacCer may be due to the fatty acid composition. Collectively, our observations suggest that LacCer specifically stimulates PE-CAM-1 expression in U-937 cells.

The maximal stimulation of PECAM-1 protein by LacCer was observed at 1 h. During this time, the interaction of LacCer with glucan-like molecules has been documented (21). The possibility that endogenous LacCer was involved in this process was excluded by the observation that d-1-phenyl-2-decanoylamino-3-morpholino-1-propanol, which inhibited the synthesis of endogenous LacCer, did not decrease the PECAM-1 level in U-937 cells (data not shown). Instead, LacCer up-regulated PECAM-1 expression in U-937 cells by serving as an extracellular signaling molecule, other than its role as a lipid second messenger for tumor necrosis factor-α-induced ICAM-1 expression in HUVECs (13). Sphingosine 1-phosphate, a lysosphingolipid metabolitically related to LacCer, was also reported to function by being an extracellular signaling molecule in addition to its role as a second messenger and thus was involved in a variety of biological functions (22, 23). Further studies will be required to investigate whether LacCer recruits a receptor or some other well-documented phospholipase C/diacylglycerol molecules implicated in PKCα and -ε activation and PECAM-1 expression in U-937 cells.

There seemed to be a difference in the mechanism by which chelerythrine chloride and GÖ 6976 exert their inhibitory effect on PKC isoforms. Chelerythrine chloride, a competitive inhibitor of PKC with respect to the phosphate acceptor (histone IIIS) (24), decreased the endogenous PECAM-1 level in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2 A Left), and this was not reversed by LacCer. In contrast, the GÖ 6976-mediated decrease in endogenous the PECAM-1 level was reversed by LacCer (Fig. 2B). Because GÖ 6976 targets only PKCα and -β, whereas LacCer-mediated PECAM-1 expression requires PKCα and -ε (Fig. 3 B and C), a compensatory mechanism must exist that uses LacCer-mediated PECAM-1 expression even when PKCα activity is inhibited in U-937 cells. Nonetheless, these findings suggest that PKC serves as a molecular target for LacCer, and its activation is essential for the up-regulation of PECAM-1 by LacCer. Conversely lysophosphatidylcholine (15 μM) induced tyrosine phosphorylation of PECAM-1 in bovine aortic endothelial cells via a PKC-independent manner (25).

Because PKC was reported to phosphorylate PLA2 and thus enhanced its activity (14), we also investigated the role of PLA2 in the up-regulation of PECAM-1 by LacCer in human monocytes in this study. We found that LacCer stimulated the activity of PLA2. In addition, we found that BPB, an inhibitor of PLA2, inhibited PECAM-1 expression, and this inhibitory effect could not be bypassed by the addition of LacCer (Fig. 6A). These results suggest that PLA2 is essential for PECAM-1 stimulation by LacCer. Furthermore, because bromoenol lactone (specific inhibitor of iPLA2) and methyl arachidonyl fluorophosphonate (an inhibitor of iPLA2 and cPLA2) inhibited LacCer-induced PLA2 activity (but not LY311727, a secretory PLA2 inhibitor; data not shown), this may suggest that LacCer recruits iPLA2 and/or cPLA2 to stimulate PECAM-1 expression in U-937 cells. Our experiment on the effect of PKC inhibitors on LacCer-mediated PLA2 activation suggests that PLA2 locates down-stream of PKC in the signaling events involved in PECAM-1 expression. Our findings are in agreement with the observation of Rashba-Step (15) in which PKC phosphorylated cPLA2 and hence increased its activity.

The role of PLA2 was further confirmed by the result that arachidonic acid stimulated PECAM-1 expression by ≈80% as compared to the control, but other fatty acids present in LacCer such as palmitic acid and stearic acid did not (Fig. 6C). Most interestingly, the inhibitory effect of BPB was bypassed by the addition of arachidonic acid (Fig. 6B). Because phospholipids containing arachidonic acid at the sn-2 site are known to be the preferable substrates of cPLA2 (26), these results suggest that cPLA2 was mainly involved in this reaction.

We further showed that arachidonic acid regulated PECAM-1 through its product prostaglands via the action of COX-1 and -2. This effect could be through the downstream activation of NF-κB (a heterodimer consisting of p65/RelA and p50/NF-κB1) by prostaglandin E2. Previously, prostaglandin E2 was shown to promote the inherent transcriptional activity of the p65/RelA subunit of NF-κB instead of stimulating the nuclear translocation of NF-κB (27). Because PGE2 is the most abundant prostaglandin produced in response to inflammation, it may well stimulate NF-κB transactivation and PECAM-1 expression (Fig. 10, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). However, PGH2 can also be converted to PGF2, PGI2, and PGD2 (Fig. 10). Such molecules have been shown to inhibit the nuclear translocation of NF-κB (27) and therefore may play a compensatory role in comparison to PGE2 and may later reduce PECAM-1 to the basal level (Fig. 1 A). Consistent with this finding, one consensus sequence of NF-κB is found in the promoter of the PECAM-1 gene (20). We speculate that LacCer may recruit PGE2-induced transcriptional activation to induce PECAM-1 expression in U-937 cells. This tenet is supported by studies in which LacCer was observed to activate NF-κB in HUVECs and thus stimulate ICAM-1 expres sion and cell adhesion (13). However, in view of a recent report (19), other/alternate transcriptional factors such as GATA-2 may also be involved in PECAM-1 regulation.

In HUVECs, free radicals generated by endogenously produced LacCer were essential for the activation of NF-κB and subsequent up-regulated expression of ICAM-1 (13). In contrast, our studies with human monocytes using N-acetylcysteine, a scavenger of free radicals, and diphenylene iodonium, an inhibitor of NADPH oxidase, suggest that the signal transduction event involving the stimulation of PECAM-1 initiated by LacCer is free radical independent (data not shown). However, it is possible that other reactive oxygen species such as nitric oxide may be implicated in PECAM-1 regulation in vascular cells.

PECAM-1 has been known to function as a cell adhesion molecule as well as a scaffolding molecule capable of modulating cellular signaling pathways (28), the transendothelial migration of leukocytes in vitro (29), and in animal models of inflammation (30). In accordance with these previous studies, we observed that LacCer stimulated cell adhesion that was abrogated by inhibitors specific for either PKC or PLA2. The previously increased level of PECAM-1 was found to be expressed on monocytes in both aging people and in patients with coronary artery diseases (31). Our study further suggests that LacCer, via stimulating PE-CAM-1 expression, may well play a critical role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis.

The focal recruitment of monocytes to the endothelium is perhaps the earliest event in lesion formation in atherosclerosis. Clearly cell adhesion molecules such as ICAM-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM-1), and PECAM-1 play a critical role in this process. We have shown a marked increase in LacCer level and in GlcCer and Gbose3Cer in human atherosclerotic plaques as compared to normal aorta tissue (12). We have also shown that LacCer can stimulate ICAM-1 (13), and now we demonstrate that LacCer may well stimulate PECAM-1 expression in HUVECs as well as in human promonocytes. In parallel studies with apolipoprotein E knockout mice, in which the atherosclerotic lesion mimic closely to the human atherosclerotic lesions, it has been shown that the aorta is markedly increased in LacCer and other glycosphingo lipids (32) as well as PE-CAM-1 and ICAM-1 (33).

Collectively, these findings and our present study point to the speculation/conclusion that LacCer may well contribute to an increased PECAM-1 level in human atherosclerosis and in animal models of atherosclerosis such as in apolipoprotein E knockout mice. In summary, by way of stimulating PECAM-1, LacCer may well play a critical role in the pathophysiology in atherosclerosis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Fang Lu and Song Jie for expert technical assistance. This project was supported in part by a Johns Hopkins Singapore Research grant and by National Medical Research Council, Singapore, Grant 0618-2001. We thank Professor Edward Dennis (University of California, Los Angeles) for suggestions and Eli Lilly Company (Indianapolis) for the supply of LY311727.

Abbreviations: HUVEC, human umbilical vein endothelial cell; iPLA2, intracellular Ca2+-independent phospholipase A2; cPLA2, cytosolic PLA2; BPB, bromophenacyl bromide; GÖ 6850, 2-[1-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-1H-indol-3-yl]-3-(1H-indol-3-yl)-maleimide; GÖ 6976, 12-(2-cyanoethyl)-6,7,12,13-tetrahydro-13-methyl-5-oxo-5H-indolo(2,3-a)pyrrolo(3,4-c)-carbazole; COX, cyclooxygenase; Lacer, lactosylceramide; PECAM-1, platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1; ICAM-1, intercellular cell adhesion molecule-1.

References

- 1.Minehata, K., Mukouyama, Y. S., Sekiguchi, T., Hara, T. & Miyajima, A. (2002) Blood 99, 2360-2368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shih, S. C., Robinson, G. S., Perruzzi, C. A., Calvo, A., Desai, K., Green, J. E., Ali, I. U., Smith, L. E. & Senger, D. R. (2002) Am. J. Pathol. 161, 35-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Serebruany, V. L., Murugesan, S. R., Pothula, A., Atar, D., Lowry, D. R., O'Connor, C. M. & Gurbel, P. A. (1999) Eur. J. Heart Fail. 1, 243-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Serebruany, V. L., Murugesan, S. R., Pothula, A., Semaan, H. & Gurbel, P. A. (1999) Cardiology 91, 50-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blann, A. D., Devine, C., Amiral, J. & McCollum, C. N. (1998) Blood Coagul. Fibrinolysis 9, 479-484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schimmenti, L. A., Yan, H. C., Madri, J. A. & Albelda, S. M. (1992) J. Cell. Physiol. 153, 417-428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hakomori, S. (1990) J. Biol. Chem. 265, 18713-18716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chatterjee, S. (1991) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 181, 554-561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhunia, A. K., Han, H., Snowden, A. & Chatterjee, S. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 15642-15649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arai, T., Bhunia, A. K., Chatterjee, S. & Bulkley, G. B. (1998) Circ. Res. 825, 540-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chatterjee, S., Kwiterovich, P. O. Jr., Gupta, P., Erozan, Y. S., Alving, C. R. & Richards, R. L. (1983) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 80, 1313-1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chatterjee, S., Dey, S., Shi, W. Y., Thomas, K. & Hutchins, G. M. (1997) Glycobiology 7, 57-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhunia, A. K., Arai, T., Bulkley, G. & Chatterjee, S. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 34349-34357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mellor, H. & Parker, P. J. (1998) Biochem. J. 332, 281-292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rashba-Step, J., Tatoyan, A., Duncan, R., Ann, D., Pushpa-Rehka, T. R. & Sevanian, A. (1997) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 343, 44-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simmons, D. L., Walker, C., Power, C. & Pigott, R. (1990) J. Exp. Med. 171, 2147-2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirschbaum, N. E., Gumina, R. J. & Newman, P. J. (1994) Blood 84, 4028-4037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stockinger, H., Gadd, S. J., Eher, R., Majdic, O., Schreiber, W., Kasinrerk, W., Strass, B., Schnabl, E. & Knapp, W. (1990) J. Immunol. 145, 3889-3897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gumina, R. J., Kirschbaum, N. E., Piotrowski, K. & Newman, P. J. (1997) Blood 89, 1260-1269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Botella, L. M., Puig-Kroger, A., Almendro, N., Sanchez-Elsner, T., Munoz, E., Corbi, A. & Bernabeu, C. (2000) J. Immunol. 164, 1372-1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zimmerman, J. W., Lindermuth, J., Fish, P. A., Palace, G. P., Stevenson, T. T., DeMong, D. E. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 22014-22020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kon, J., Sato, K., Watanabe, T., Tomura, H., Kuwabara, A., Kimura, T., Tamama, K.-I., Ishizuka, T., Murata, N., Kanda, T., et al. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 23940-23947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghosh, T. K., Bian, J. & Gill, D. L. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 22628-22635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herbert, J. M., Augereau, J. M., Gleye, J. & Maffrand, J. P. (1990) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 172, 993-999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ochi, H., Kume, N., Nishi, E., Moriwaki, H., Masuda, M., Fujiwara, K. & Kita, T. (1998) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 243, 862-868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clark, J. D., Lin, L. L., Kriz, R. W., Ramesha, C. S., Sultzman, L. A., Lin, A. Y., Milona, N. & Knopf, J. L. (1991) Cell 65, 1043-1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poligone, B. & Baldwin, A. S. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 38658-38664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Graesser, D., Solowiej, A., Bruckner, M., Osterweil, E., Juedes, A., Davis, S., Ruddle, N. H., Engelhardt, B., Madri, J. A. (2002) J. Clin. Invest. 109, 383-392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liao, F., Huynh, H. K., Eiroa, A., Greene, T., Polizzi, E. & Muller, W. A. (1995) J. Exp. Med. 182, 1337-1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wakelin, M. W., Sanz, M. J., Dewar, A., Albelda, S. M., Larkin, S. W., Boughton-Smith, N., Williams, T. J. & Nourshargh, S. (1996) J. Exp. Med. 184, 229-239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Masuda, M. & Takahashi, H. (1998) Rinsho. Byori. 46, 1149-1155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garner, B., Priestman, D. A., Stocker, R., Harvey, D. J., Butters, T. D. & Platt, F. M. (2002) J. Lipid Res. 43, 205-214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zibara, K., Chettab, K., McGregor, B., Poston, R. & McGregor, J. (2001) Thromb. Haemostasis 85, 908-914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.