Abstract

Background

EUS-guided rendezvous procedure (EUS-RV) can be done by the transhepatic (TH) or the extrahepatic (EH) route. There is no data on the preferred access route when both routes are available.

Study aim

To compare the success, complications, and duration of hospitalization for patients undergoing EUS-RV by the TH or the EH route.

Patients and methods

Patients with distal common bile duct (CBD) obstruction, who failed selective cannulation, underwent EUS-RV by the TH route through the stomach or the EH route through the duodenum.

Results

A total of 35 patients were analysed (17 TH, 18 EH). The mean procedure time was significantly longer for the TH group (34.4 vs. 25.7 min; p = 0.0004). There was no difference in the technical success (94.1 vs. 100%). However, the TH group had a higher incidence of post-procedure pain (44.1 vs. 5.5%; p = 0.017), bile leak (11.7 vs. 0; p = 0.228), and air under diaphragm (11.7 vs. 0; p = 0.228). All bile leaks were small and managed conservatively. Duration of hospitalization was significantly higher for the TH group (2.52 vs. 0.17 days; p = 0.015).

Conclusions

EUS-RV has similar success rate by the TH or the EH route. However, the TH route has higher post-procedure pain, longer procedure time, and longer duration of hospitalization. The EH route should be preferred for EUS-RV in patients with distal CBD obstruction when both access routes are technically feasible.

Keywords: Biliary, endosonography, ERCP, precut, rendezvous, stent

Introduction

The EUS-guided rendezvous procedure (EUS-RV) has emerged as a rescue procedure for patients with failed endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and biliary drainage.1 We have also shown EUS-RV to be an acceptable alternative to precut papillotomy in patients with difficult bile duct cannulation.2 One of the advantages of EUS-guided biliary drainage procedure is the possibility of accessing the biliary ductal system from multiple routes. The dilated intrahepatic biliary radicals (IHBR) can be accessed from the liver via the distal oesophagus or stomach (transhepatic, TH) or the common bile duct (CBD) can be punctured from the proximal duodenum (extrahepatic, EH). Rarely, the CBD can be accessed from gastric antrum. This choice of access routes allows endoscopic biliary drainage even in patients with duodenal obstruction or duodenal bypass surgeries. Published reports on EUS-RV have utilized both these routes with varying success rates.3–5 However, it is not clear which route is preferable when both routes are available to the endoscopist. This study was performed to compare the success rate, complications, procedure time, and hospitalization time for patients undergoing EUS-RV by the TH or the EH route.

Patients and methods

This was a retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data from patients who underwent EUS-RV at our centre from February 2011 to December 2011. Data of consecutive patients with distal CBD obstruction who failed attempts at selective CBD cannulation with sphincterotome and guide wire during ERCP was entered in a standard database. Precut papillotomy was not attempted in view of our earlier study showing equivalent efficacy of EUS-RV and precut papillotomy.2 Exclusion criteria were duodenal obstruction, post-surgical anatomy (Whipples, gastrojejunostomy or biliary reconstruction procedures), extensive collaterals, multiple liver metastasis, and concomitant EUS-guided stent placement.

Informed consent for both procedures was obtained prior to ERCP. The EUS-RV procedure was done immediately following a failed ERCP in the same session. Prophylactic antibiotics (sulbactam and cefoperazone, 1000 mg intravenous, 30 min prior to procedure) were administered to all patients. All procedures were done under propofol anaesthesia administered by an anaesthetist with appropriate cardiorespiratory monitoring. Endosonographic survey of biliary system was done prior to intervention and bile duct measurements were taken. Generally, transhepatic approach was attempted first when dilated intrahepatic biliary radicals were visualized and accessible without intervening vessels. Extrahepatic approach was tried first in patients with mildly dilated IHBR.

TH access

A linear array echoendoscope (GFUCT140; Olympus Medical, Tokyo, Japan) and a 19-gauge needle (Echo Tip 19A; Cook Endoscopy, Winston Salem, NC, USA) were used to puncture the intrahepatic biliary radical. The choice of biliary radical was dictated by the diameter of the radical, proximity to the echoendoscope, and absence of intervening vessels. Attempt was made to puncture the radical with the echoendoscope in a straight position and the needle pointing in the direction of the common bile duct (Figure 1). This meant that the puncture was made just above the gastro-oesophageal junction. Once biliary access was confirmed by aspiration of 5–10 cc bile, contrast was injected to evaluate the ductal system and, a 260-cm long 0.032-inch hydrophilic angled-tip guide wire (Glide wire; Terumo Medical, Somerset, NJ, USA) was inserted through the needle and directed in an anterograde fashion downstream across the stricture and/or the papilla into the duodenum (Figure 2). If the wire could not be manoeuvred, several loops of the wire were made in the hilar ductal system and the needle was exchanged for a 5F tapered tip catheter (Proforma cannula; Conmed Endoscopic Technologies, Chelmsford MA, USA). The catheter improved manoeuvrability of the wire as it could be passed all the way to the obstruction (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Needle puncture in the left lobe intrahepatic biliary radical.

Figure 2.

Guidewire manipulated across the papilla in to the duodenum.

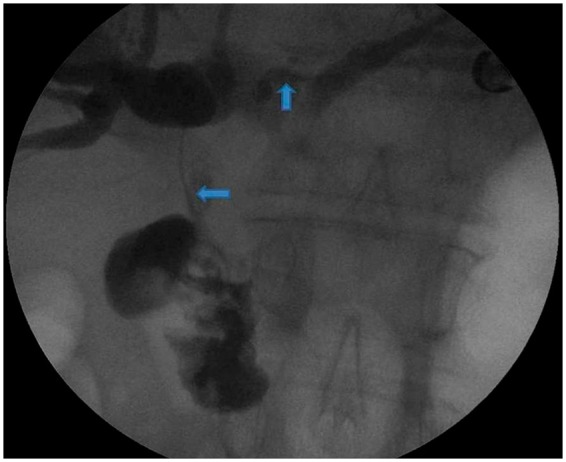

Figure 3.

The 5 french catheter maneuvered across the hilum in to the CBD (arrows) just above the stricture.

Once the guide wire crossed the papilla and looped in the duodenum, the echoendoscope was withdrawn and an ERCP scope was positioned at the papilla. Due to the short length of wire, continuous water injection was used to keep the wire in position when the wire disappeared in the scope, as described previously.6 The guide wire was pulled into the biopsy channel of duodenoscope with a snare and ERCP was completed. The EUS and ERCP procedures were done by two different endoscopists (VD and AM, respectively).

EH access

The procedure for extrahepatic puncture has been described before.6 Briefly, the CBD was punctured with a 19-gauge needle from the duodenum (Figure 4). The wire was manoeuvred downstream through the obstruction and papilla (Figure 5). Once several loops of wire were made in the duodenum, the echoendoscope was withdrawn (Figure 6), and a duodenoscope was positioned in front of the papilla. After retrieving the wire via the biopsy channel of the duodenoscope using a snare, ERCP was completed.

Figure 4.

Needle puncture in the common bile duct.

Figure 5.

Guidewire manipulated across the obstruction and the papilla in to duodenum.

Figure 6.

Echoendoscope being withdrawn, keeping loops of wire in the duodenum.

Post-procedure follow up

Patients were kept under observation for 6 hours post procedure and discharged if the vital signs were normal and there was no pain and /or abdominal distension. Patients were admitted if they had abdominal pain and/or distension 6 hours post procedure. Discharged patients were contacted by telephone on days 2 and 7 post procedure to enquire about pain and fever. Serum bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase levels were checked on day 8.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was technical success, defined as ability to complete the intended therapeutic procedure in a single session. Secondary outcome measures included procedure time, post-procedure complications, and length of hospital stay. Procedure time was defined as the time between the introduction of the echoendoscope and the final introduction of the duodenoscope for performing ERCP. Pain was defined as abdominal pain persisting for >6 hours and requiring hospitalization. Bile leak was defined as contrast visualized during procedure or collection of bile on follow-up ultrasound. The complications were graded in accordance with a lexicon of adverse events for endoscopy.7

Statistical analysis

We used epi info software (version 3.4) for statistical analysis. The chi-squared test and Fisher's test were used to compare the rates of success and complications. Student's t-test was used for comparison of continuous variables. Institutional ethics approval was acquired for the data analysis.

Results

Forty patients underwent EUS-guided biliary interventions in the study period. Five patients were excluded from analysis as they underwent EUS-guided stent placements. The patient profile and procedural indications are shown in Table 1. There was no significant difference between the two groups with regards to patient demographics and common bile duct dimensions. The IHBR diameter in the TH group was significantly higher than that in the EH group (4.2 ± 1.01 vs. 3.4 ± 0.62 mm, p = 0.0001).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Transhepatic (n = 17) | Extrahepatic (n = 18) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 53.06 ± 11.22 | 53.83 ± 10.72 | 0.753 |

| Males | 10 | 12 | 0.732 |

| Malignant:Benign | 11:6 | 13:5 | 0.724 |

| CBD diameter (mm) | 12.24 ± 1.44 | 12.33 ± 1.68 | 0.215 |

| IHBR (mm) | 4.2 ± 1.01 | 3.4 ± 0.62 | 0.0001 |

| Diagnosis | |||

| Ca head pancreas | 9 | 12 | |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 2 | 1 | |

| Benign CBD stricture | 4 | 2 | |

| CBD stone | 2 | 3 |

Values are mean ± SD or n.

CBD, common bile duct; IHBR, intrahepatic biliary radicals.

Technical success and complications are shown in Table 2. Technical success could be achieved in 34/35 patients (97.14%) with no significant difference in technical success between both groups. The lone failure in the TH group was due to inability to pass the wire across the biliary stricture in a patient with pancreatic head cancer. This patient was referred for percutaneous drainage. The mean procedure time for TH procedures was significantly longer than that for EH procedures (34.41 ± 8.45 vs. 25.70 ± 3.75 min, p = 0.0004; Table 2). This was due to the fact that the needle had to be exchanged for a catheter in six patients for successful negotiation across the papilla. A total of eight patients (22.85%) required admission beyond the 6 h observation period. Significantly higher number of patients in the TH group experienced pain requiring hospital admission (41.1 vs. 5.5%, p = 0.017). Four of seven patients with pain in the TH group had bile leak (two patients) or air under diaphragm (two patients). The mean length of stay was also significantly longer for the TH group (2.52 vs. 0.17 days, p = 0.015; Table 2). One patient in the TH group with severe pain and air under the diaphragm underwent surgical exploration for suspected perforation on the fourth post-procedure day. However, no perforation was found. The other three patients with air under diaphragm and bile leak improved with conservative management.

Table 2.

Outcomes and complications

| Transhepatic (n = 17) | Extrahepatic (n = 18) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Success | 16 (94.1) | 18 (100) | 0.485 |

| Pain | 7 (41.1) | 1 | 0.017 |

| Bile leaka | 2 (11.7) | 0 | 0.228 |

| Air under diaphragma | 2 (11.7) | 0 | 0.228 |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 2.52 ± 2.25 | 0.17 ± 0.73 | 0.015 |

| Procedure time (mins) | 34.41 ± 8.45 | 25.71 ± 3.75 | 0.0004 |

Values are n (%) or mean ± SD. Total number of patients with complications in the TH group is seven.

Patients with bile leak/air under diaphragm also had pain.

Discussion

Recent studies on EUS-RV have shown success rates varying from 72 to 98.3% and complication rates from 3.2 to 41% (Table 3). We believe that the differences in the success rates in these studies could be explained by ability to negotiate the wire across the stricture and papilla. Our study shows that technical success for EUS-RV is high regardless of the access route chosen. However, we found the EH access route superior in terms of procedure duration, complications, and duration of hospitalization. Although there is no previous study comparing the two access routes, Table 3 shows recent studies utilizing the two routes. Iwashita et al.9 found marked differences in the success rate and complications between the TH and EH approachs, the success rate for the TH route being just 44% with a 25% complication rate. Kahaleh et al.4 had to convert 27% (5/18) patients' access routes from transhepatic to extrahepatic due to inability to negotiate the wire across the stricture. Although they found a higher rate of complication with the EH route, it is not clear whether the complications occurred following a EUS-RV procedure or following a EUS-guided direct stenting procedure. Shah et al.10 had a 75% success rate with EUS-RV. They mentioned that they preferred the TH route for access, but details of the number of patients undergoing EUS-RV by each route were not provided.

Table 3.

EUS-RV: results with transhepatic and extrahepatic routes

| Study | No of patients | Extrahepatic access |

Transhepatic access |

Overall success | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Success | Complication | Success | Complication | |||

| Kim et al.8 | 15 | 12/15 (80) | 2/15 (13.3) | – | – | 80 |

| Kahaleh et al.4 | 23a | 7/10 (70) | 3/10 (30) | 11/18 (61) | 1/18 (9) | 78 |

| Iwashita et al.9 | 40 | 25/31 (81) | 1/31 (3.2) | 4/9 (44) | 1/9 (25) | 72 |

| Shah et al.10 | 52 | NS | NS | NS | NS | 75 |

| Dhir et al.2 | 58 | 57/58 (98.3) | 2/58 (3.4) | – | – | 98.3 |

| Present study | 35 | 18/18 (100) | 1/18 (5.5) | 16/17 (94.1) | 7/17 (41) | 97 |

Values are n/total (%) or %.

Five patients crossed over to extrahepatic after failed transhepatic access.

The complication rates in our study are in keeping with the current standards and reported rates. Other studies have reported complication rates ranging from 10 to 25% for similar EUS-guided interventions.4–10 In our study, the overall complication rate was 22.85%. However, it must be mentioned that majority of our complications were mild in nature. We did not encounter significant bleeding, pancreatitis, or cholangitis. Two patients had bile leak which settled on conservative management. Together with one suspected perforation, this makes our potentially serious complication rate to be 8.5% (3/35). Pain was considered a complication in keeping with the lexicon's criteria,9 as it resulted in prolonged hospital stay. Half of the patients with pain lasting more than 6 h had bile leak or air under diaphragm. Thus prolonged pain served as a marker of potentially serious complications. Minor bile leak was seen in 11.7% of the TH patients. While this was not significantly higher than the EH patients (no leak), it could be due to a type II error.

The reason for higher incidence of complications seen with the TH route is likely multifactorial. The TH route involves puncture into the peritoneal cavity as the EUS needle is advanced through the oesophageal or proximal gastric wall, followed by puncture of the liver capsule. There is also dynamic movement of the left lobe of the liver with respiration despite the EUS needle being kept relatively stable and stationary by the endoscope. This probably leads to increased trauma to the puncture tract and subsequently higher likelihood of bile leak and pain. Additionally, the fundus of the stomach contains greater amount of free air compared to the duodenum and likely contributes to the greater amount of air leakage during the EUS-guided intrahepatic puncture. Itoi et al.11 reported the limitations of the intrahepatic puncture, including non-apposed gastric wall and the left liver lobe, risk of mediastinitis with a transoesophageal approach, difficulty of puncture in case of liver cirrhosis, risk of injury to the portal vein, and necessitating the use of small-calibre stents with a small-diameter delivery device.

With the EH route of biliary access, the puncture is made predominantly via a retroperitoneal route and the duodenum is in close proximity to the dilated CBD. The retroperitoneal location of the common bile duct makes it also an attractive access site for patients with ascites, in whom fluid around the liver makes TH access more difficult and hazardous. The distal CBD is also relatively fixed in this part compared to the intrahepatic ducts and there is less respiratory influence. There are also no large intervening blood vessels between the duodenal wall and the extrahepatic bile duct. Due to the anatomical location of the puncture site in the bile duct, the defect made by the needle is subsequently covered and sealed once the stent is placed. These factors most likely contribute to significantly lower rates of post-procedure pain, bile leak, and pneumoperitoneum.

Although most of the complications in our study were mild, they did increase the hospitalization time, significantly more so in the TH group. Although we did not calculate healthcare costs, this has financial implications. There are no previous studies regarding the additional time taken by the EUS-RV procedure. The longer time taken for TH access in our study could be explained by difficulty in negotiating the wire across the obstruction and papilla. The wire has a tendency to loop at the hilum and cross over to the right side. In addition, crossing the distal CBD stricture is difficult due to the long length of floppy wire from the liver to the stenosis, making it susceptible to take a U turn towards the hilum. We had to exchange the needle for a catheter in six patients before successful negotiation of wire could be done.

Our study does have limitations. It is a retrospective analysis of prospectively entered data performed in a single institution. The number of patients included is relatively small and it is possible that a type II error might exist, although the results show a significant difference in complication rates amongst the two groups. There is a probable selection bias in this study since we utilized the TH or the EH route depending upon the diameter of the intrahepatic biliary radicals. However, the TH route is not usually employed for patients with non-dilated or minimally dilated intrahepatic biliary radicals. A prospective randomized comparison is needed to eliminate these potential limitations.

In summary, our results show that EUS-RV can be performed with high success rate utilizing either the TH or the EH route. However, the TH route is associated with longer procedure time, higher complication rate and longer hospitalization. We believe that when both routes are available, the EH route should be chosen for access. The TH route should be reserved for patients with proximal biliary obstruction and those with altered upper gastrointestinal anatomy. These results were obtained at a tertiary centre with expertise in these procedures and further studies are needed to see whether they are applicable generally.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Yoon WJ, Brugge WR. EUS-guided biliary rendezvous: EUS to the rescue. Gastrointest Endosc 2012; 75: 360–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dhir V, Bhandari S, Bapat M, et al. Comparison of EUS-guided rendezvous and precut papillotomy techniques for biliary access (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc 2012; 75: 354–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mallery S, Matlock J, Freeman ML. EUS-guided rendezvous drainage of obstructed biliary and pancreatic ducts: Report of 6 cases. Gastrointest Endosc 2004; 59: 100–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kahaleh M, Hernandez AJ, Tokar J, et al. Interventional EUS-guided cholangiography: evaluation of a technique in evolution. Gastrointest Endosc 2006; 64: 52–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Artifon EL, Ferreira FC, Otoch JP, et al. EUS-guided biliary drainage: a review article. JOP 2012; 13: 7–17 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dhir V, Kwek BE, Bhandari S, et al. EUS-guided biliary rendezvous using a short hydrophilic guidewire. J Interv Gastroenterol 2011; 1: 153–159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cotton PB, Eisen GM, Aabakken L, et al. A lexicon for endoscopic adverse events: report of an ASGE workshop. Gastrointest Endosc 2010; 71: 446–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim YS, Gupta K, Mallery S, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound rendezvous for bile duct access using a transduodenal approach: cumulative experience at a single center. A case series. Endoscopy 2010; 42: 496–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iwashita T, Lee JG, Shinoura S, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided rendezvous for biliary access after failed cannulation. Endoscopy 2012; 44: 60–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shah JN, Marson F, Weilert F, et al. Single-operator, single-session EUS-guided anterograde cholangiopancreatography in failed ERCP or inaccessible papilla. Gastrointest Endosc 2012; 75: 56–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Itoi T, Sofuni A, Itokawa F, et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided biliary drainage. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2010; 17: 611–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]