Abstract

Background

Pharyngeal pH probes and pH-impedance catheters have been developed for the diagnosis of laryngo-pharyngeal reflux.

Objective

To determine the reliability of pharyngeal pH alone for the detection of pharyngeal reflux events.

Methods

24-h pH-impedance recordings performed in 45 healthy subjects with a bifurcated probe for detection of pharyngeal and oesophageal reflux events were reviewed. Pharyngeal pH drops to below 4 and 5 were analysed for the simultaneous occurrence of pharyngeal reflux, gastro-oesophageal reflux, and swallows, according to impedance patterns.

Results

Only 7.0% of pharyngeal pH drops to below 5 identified with impedance corresponded to pharyngeal reflux, while 92.6% were related to swallows and 10.2 and 13.3% were associated with proximal and distal gastro-oesophageal reflux events, respectively. Of pharyngeal pH drops to below 4, 13.2% were related to pharyngeal reflux, 87.5% were related to swallows, and 18.1 and 21.5% were associated with proximal and distal gastro-oesophageal reflux events, respectively.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that pharyngeal pH alone is not reliable for the detection of pharyngeal reflux and that adding distal oesophageal pH analysis is not helpful. The only reliable analysis should take into account impedance patterns demonstrating the presence of pharyngeal reflux event preceded by a distal and proximal reflux event within the oesophagus.

Keywords: Gastro-oesophageal reflux, laryngo-pharyngeal reflux, oesophageal impedance, pharyngeal pH

Introduction

The concept of laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) has been developed by ENT specialists; it is defined by the association of laryngeal symptoms with laryngeal inflammation at laryngoscopy.1 However, symptoms are non-specific and difficult to characterize. Laryngoscopic signs supposed to be related to LPR have also a very poor specificity and can be observed in up to 70% of asymptomatic subjects.2 Response to proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) is part of the LPR definition but a clinical response to PPIs is likely to be related to a placebo effect.3,4 Current recommendations suggest documenting the presence of abnormal gastro-oesophageal reflux (GOR) by endoscopy and/or 24-h reflux testing.5 If the presence of pathological GOR disease (GORD) is confirmed in <40% of patients,6 a direct causal relationship between GORD and laryngeal symtoms is difficult to establish. Moreover, the presence of abnormal proximal and/or distal acid reflux on pH monitoring does not predict response to therapy.7 Therefore, there is a need for the development of new tools which may help to better identify the subgroup of patients with laryngeal symptoms related to LPR.8

Proximal oesophageal pH recordings can be performed with a ‘dual-probe’ pH catheter, but this technique does not allow positioning of the proximal probe in a uniform location relative to the upper oesophageal sphincter (UOS)9 and has a poor reproducibility.10 Pharyngeal pH recordings can be done with a pH sensor positioned 2 cm above the UOS previously located with manometry; However, this technique has many limitations mainly related to artefacts.11 The so-called Restech technique has been developed. This is a novel nasopharyngeal pH catheter capable of measuring liquid and aerosolized acid levels. Two sets of normal values have been established12,13 and two recent short and uncontrolled studies suggested that Restech technique could predict response to both medical14 and surgical therapy15 with a good sensitivity and specificity. Finally the impedance technology has been recently used to detect reflux events reaching the pharynx. Pharyngeal impedance catheters consist of bifurcated catheters allowing reliable positioning of the impedance and pH sensors above the upper and lower oesophageal sphincters, whatever the height of the subject. This technique allows the detection and characterization of all types of reflux events; reflux episodes are followed from the distal oesophagus to the pharynx. Our group has recently published a set of normal values of pharyngeal reflux (PR) ‘off’ and ‘on’ PPIs with this technique.16

The aim of this study was to evaluate the relevance of pharyngeal pH drops assessed by characterizing the pharyngeal and oesophageal impedance patterns associated with pharyngeal pH drops.

Methods

Study design and subjects

Healthy volunteers were recruited by advertising in six university hospitals in France (Bordeaux, Nantes, Lyon, Rouen, Colombes, Rennes). A careful interview was conducted to exclude the presence of typical (heartburn, regurgitation) and atypical symptoms (excessive belching, cough, asthma or wheezing, hoarseness, chest pain) suggestive or potentially related to GORD. Exclusion criteria were: history of thoracic or digestive surgery (excepted appendectomy), alcohol consumption >40 g/day, smoking >10 cigarettes/day, nursing mothers, subjects on medications that alter intragastric acidity or oesophageal motility, gastrointestinal disease, and allergy to esomeprazole or benzamidazole derivates. Concomitant treatment with clopidogrel was prohibited. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects and the protocol was approved by the Comité de Protection des Personnes (CPP) Sud-Ouest Outre-Mer 3. The subjects received financial compensation for their participation to the study. These healthy subjects participated in a study that aimed to determine normal values of gastro-oesophageal and pharyngeal reflux recently published.16

Study protocol

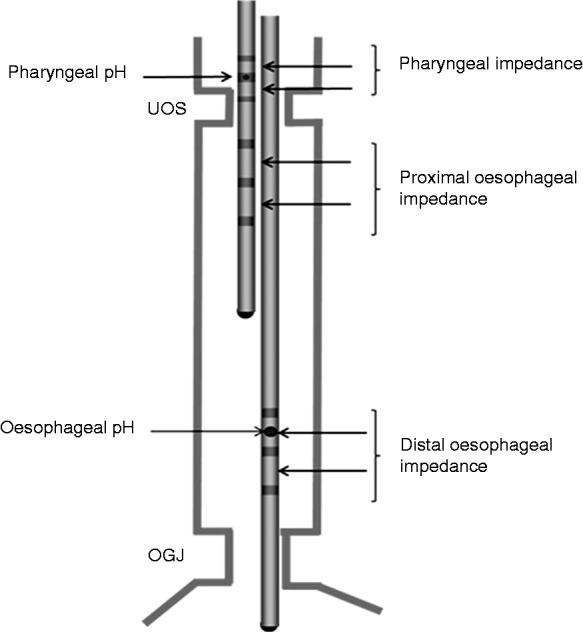

The study protocol has been described previously.16 The studies were performed on an outpatient basis after an overnight fast. A high-resolution oesophageal manometry permitted to locate the upper UOS and oesophagogastric junction (OGJ). Studies were performed with a bifurcated pH-impedance catheter (Sandhill Scientific, Highlands Ranch, CO, USA; Figure 1). The long arm branch of the catheter had two electrode pairs positioned at 3 and 5 cm proximal to the OGJ with a pH sensor positioned 5 cm proximal to the junction. The short arm branch had two electrode pairs in the proximal oesophagus and two pairs in the hypopharynx with a second pH sensor located 0.5 cm proximal to the upper border of the UOS. Before recording, the catheter was calibrated using pH 4.0 and pH 7.0 buffer solutions. An external reference electrode was attached to the anterior chest wall over the mid-sternum. The long branch of the catheter was first placed. Subjects were encouraged to maintain their normal activities, sleep schedule, and eat their usual meal.

Figure 1.

Bifurcated oesophageal and pharyngeal pH-impedance catheter. The long arm branch has two impedance electrode pairs positioned 3 and 5 cm above the oesophagogastric junction (OGJ) and a pH sensor positioned 5 cm above the OGJ. The short arm branch has four impedance electrode pairs positioned 2 and 4 cm below the upper oesophageal sphincter (UOS) and 0 and 1 cm above the UOS; a pH sensor is located 0.5 cm above the UOS.

Definitions

Gastro-oesophageal reflux events

Liquid reflux was defined as a retrograde 50% drop in impedance starting distally (at the level of the OGJ) and propagating to at least the next two more proximal impedance measuring segments. Gas reflux was defined as a rapid (3 k Ω/s) increase in impedance >5000 Ω, occurring simultaneously in two consecutive impedance measuring segments, in absence of swallowing. Mixed liquid–gas reflux was defined as gas reflux occurring immediately before or during a liquid reflux. Pure gas reflux events (belches without liquid component) were not taken into account. Reflux events were considered as distal if the impedance drop propagated to the next two more proximal impedance measuring segments. Reflux events were considered as proximal if the impedance drop reached the two electrode pairs located in the proximal oesophagus.

Pharyngeal reflux events

A pharyngeal reflux (PR) event was defined as a retrograde 50% drop in impedance starting distally (at the level of the OGJ) and reaching the more proximal impedance site. A PR event was considered only if it was preceded by retrograde impedance drop both distally and proximally within the oesophagus and if no swallow occurred during the pharyngeal impedance drop. Careful attention was taken to the baseline value regarding the frequent artefacts in impedance values within the pharynx, especially when trapped air was present. For this reason, gaseous PR events were not analysed.

Swallows

A swallow was defined as an anterograde drop in impedance starting from the UOS and reaching the OGJ.

Data analysis

The pH-impedance recording was performed during 24 h ‘off’ PPI therapy. Tracings were visually analysed using Bioview Analysis version 5.6.0.0 (Sandhill Scientific). Meals were excluded for the analysis as well as the 5-min postprandial periods which were often very artefacted.

All the tracings were carefully reviewed by FZ and SR and each individual reflux event was validated by a consensus review. Then, each tracing was analysed by MD to study the pH drops in the pharynx. All pharyngeal pH drops to below 5 lasting more than 5 s and all pharyngeal pH drops to below 4, regardless their duration, were taken into account. Slow pH drifts and artefacts were excluded from the analysis. Regarding pH instability, each increase of pH value > 5 or 4 lasting more than 5 s indicated the end of the considered pH drop.

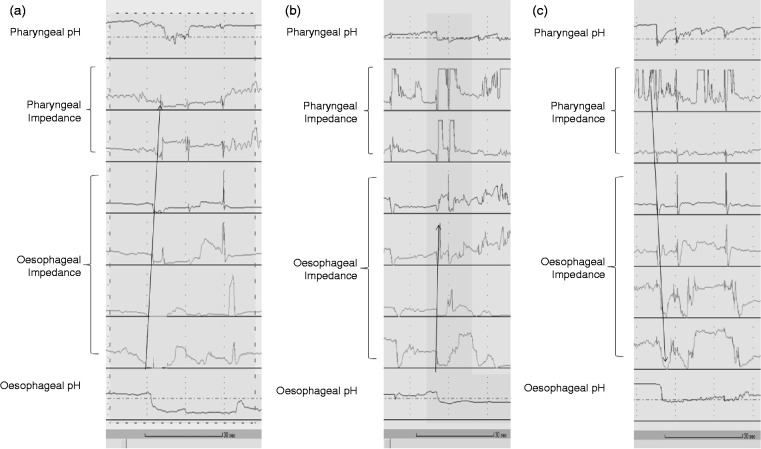

For each individual pharyngeal pH drop, oesophageal pH and impedance patterns were analysed to determine the simultaneous occurrence of PR event (Figure 2A), proximal and distal GOR event (Figure 2B), and swallows (Figure 2C). Several events could be associated during a single pH drop period; therefore the percentages of events associated with pharyngeal pH drops is >100%. Attention was also paid to the correlation between the two pH sensors. A time interval of 5 s was allowed between them to be considered as simultaneous events. A concordance was considered if oesophageal pH dropped to below 5 or 4 when the pharyngeal pH dropped to below 5 or 4, respectively.

Figure 2.

Examples of pharyngeal pH drops. (a) Pharyngeal drop to below 4 related to a gastro-oesophageal and pharyngeal reflux event; there is a drop in impedance starting distally (at the level of the oesophagogastric junction) and reaching the more proximal pharyngeal impedance site (arrow). (b) Pharyngeal pH drop to below 4 associated with a distal acid gastro-oesophageal reflux event without any evidence of proximal oesophageal nor pharyngeal extent. (c) Successive pharyngeal pH drops to below 4 and 5 related to swallows as confirmed by the impedance patterns (antegrade drop in impedance values within the oesophagus) (arrow); note that there is a simultaneous pH drop to below 4 in the distal oesophagus.

Data about event duration are expressed as median (interquartile range). Unpaired Student’s test was used for statistical analysis of median comparisons.

Results

Subjects

We analysed the pH-impedance records from 45 healthy subjects (22 females, mean age 46.3 years (range 18–78), body mass index 23.9 kg/m2 (range 16.4–31.8 kg/m2)). In six subjects, pharyngeal pH remained >5 during the whole recording. Among the remaining 39 subjects, 1211 and 147 pharyngeal pH drops to below 5 and 4, respectively, were observed, and there were 348/1211 pH drops to below 5 (28.7%) lasting more than 5 s. They were further taken into account for the analysis.

Pharyngeal pH drops to below 5

From the 348 pH drops to below 5, 91 isolated slow pH drifts and one pure gas reflux event were excluded. Thus a total of 256 pH drops to below 5 were analysed (Table 1). A simultaneous distal oesophageal pH drop to below 5 was observed in 81.3% of them. Only 7.0% of the pH drops to below 5 corresponded to a PR event determined by impedance. The majority of pH drops to below 5 were related to swallows (92.6%). Finally only 10.2 and 13.3% were associated with a proximal and distal GOR event, respectively. In 12.1% of these episodes, swallows were associated with a GOR event, at least distally.

Table 1.

Pharyngeal and oesophageal events (impedance patterns) associated with pharyngeal pH drops to below 5

| All pharyngeal pH drops (n = 256) | Simultaneous oesophageal pH drops to below 5 (n = 208) | Isolated pharyngeal pH drops (n = 48) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Distal GOR event | 34 (13.3) | 33 (15.9) | 1 (2.1) |

| Proximal GOR event | 26 (10.2) | 25 (12.0) | 1 (2.1) |

| PR event | 18 (7.0) | 17 (8.2) | 1 (2.1) |

| Swallows | 237 (92.6) | 190 (91.3) | 47 (97.9) |

Values are n (%). Sums of events are greater than totals because different types of events could occur during the same pH drop.

GOR, gastro-oesophageal reflux; PR, pharyngeal reflux.

In the 208/256 pharyngeal pH drops during which distal oesophageal pH dropped to below 5 simultaneously, 17 PR (8.2%) occurred, while only one PR event (2.1%) occurred during 48 isolated (pharyngeal only) pH drops.

The median duration of the pH drops associated with PR event was 57 s (IQR 31–96 s), not significantly different from other pH drops’ duration (23 s (IQR 11–56 s), p = 0.34).

Pharyngeal pH drops to below 4

Among the 147 pH drops, one pure gas reflux event, and two slow pH drifts were excluded; a total of 144 pH drops to below 4 were analysed (Table 2). Simultaneous drops to below 4 in distal oesophagus occurred in 88.2% of cases. Only 13.2% of pH drops to below 4 were related to PR events determined by impedance. Most pH drops were related to swallows (87.5%), and 18.1 and 21.5 % were associated with proximal and distal GOR event, respectively. Swallows were associated with a reflux event in 13/144 (9.0%) cases. When oesophageal pH was to below 4, the percentage of PR events associated with pharyngeal pH drop was 14.2%.

Table 2.

Pharyngeal and oesophageal events (impedance patterns) associated with pharyngeal pH drops to below 4

| All pharyngeal pH drops (n = 144) | Simultaneous Oesophageal pH drops to below 4 (n = 127) | Isolated pharyngeal pH drops (n = 17) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Distal GOR event | 31 (21.5) | 30 (23.6) | 1 (5.9) |

| Proximal GOR event | 26 (18.1) | 25 (19.7) | 1 (5.9) |

| PR event | 19 (13.2) | 18 (14.2) | 1 (5.9) |

| Swallows | 126 (87.5) | 110 (86.6) | 16 (94.1) |

Values are n (%). Sums of events are greater than totals because different types of events could occur during the same pH drop.

GOR, gastro-oesophageal reflux; PR, pharyngeal reflux.

The median duration of the pH drops associated with PR event was 15 s (IQR 3–39 s), not significantly different from other pH drops’ duration (8 s (IQR 2–24 s), p = 0.82).

Discussion

This study performed with pharyngo-oesophageal pH-impedance monitoring shows that pharyngeal pH drops are rarely associated with pharyngeal reflux, whatever the pH cut-off used in the pharynx. Indeed, only 7 and 13% of pH drops to below 5 and 4, respectively, were related to a pharyngeal reflux event detected by impedance within the oesophagus and the pharynx. Moreover, adding distal oesophageal pH values for the analysis did not significantly increase the relevance of pharyngeal pH drops: when a concomitant pH drop occurred in the oesophagus, only 8 and 14% were associated with pharyngeal reflux events for pH drops to below 5 and 4, respectively.

These results further confirm that pharyngeal pH values alone should not be interpreted without taking into account oesophageal events. A previous study with dual oesophageal and pharyngeal pH probes showed that most acidifications of the pharynx were due to artefacts.11 Only pH drops of more than 2 pH units reaching a nadir value to below 4 in <30 s and associated with a concomitant oesophageal acidification were considered as significant. Our study with oesophageal and pharyngeal impedance demonstrates that these restrictions based on pH values alone do not increase the relevance of pharyngeal pH drops. Indeed, even when concomitant pH drops were observed at the level of distal oesophagus, only a minority of pharyngeal pH drops were actually related to a pharyngeal reflux event (Tables 1 and 2).

According to impedance patterns, we observed that most pharyngeal pH drops were related to swallows and probably correspond to artefacts. One could also consider that subjects swallow some acidic residues present in the pharynx after a meal and/or a previous acidic reflux event. In most cases, we can rule out the hypothesis of an undeclared acidic beverage drinking according to the overall impedance patterns.

Whether the properties of recently developed nasopharyngeal pH catheters may overcome these issues remains to be determined. A recent report compared the results of 24-h oesophageal pH-impedance monitoring and nasopharyngeal pH monitoring in 10 patients with chronic cough.17 Only 1.3% of all impedance reflux episodes and none of the full column reflux (reaching the proximal oesophagus) corresponded to a ‘Restech reflux’. Moreover, only 7/39 (17.9%) pharyngeal pH drops to below 5.5 corresponded to a gastro-oesophageal reflux detected by impedance within the oesophagus. The authors of this study concluded that the Restech pH sensor could not be recommended as a validated diagnostic tool for supra-oesophageal reflux. These results are very similar to those reported in the present study, i.e. 15.9% of pharyngeal pH drops to below 5 associated with distal GOR events (Table 1). It is of note that the Restech device is supposed to detect gaseous acid reflux which is clearly a limitation of the impedance technique: pharyngeal gas reflux is very difficult to detect with impedance because the presence of air is responsible of many artefacts. However, although we did not perform a direct comparison of pharyngo-oesophageal pH-impedance and Restech pH monitoring, it appears that the most recent technology used to detect pharyngeal pH changes does not provide any benefit in terms of reliability compared to previous techniques.

Outcome studies are crucial to determine the relevance of a new medical device. To our best knowledge, there is no outcome study using pharyngeal pH-impedance in patients with suspected LPR and whether this technique will be further developed and prove to be helpful for the management of these difficult patients remains to be determined.5 Even with the help of oesophageal pH and impedance patterns, analysing pharyngeal pH-impedance events is challenging and poorly reproducible.16 This is the reason why we made a lot of efforts to have a consensus review for each individual reflux event in our study. Two short outcome studies have been reported with the Restech device. In one study, the sensitivity and specificity of the device for the diagnosis of LPR were 69 and 100%, respectively,14 but it was a small (22 patients), uncontrolled study, taking the response to PPI therapy as a gold standard. The second uncontrolled study reported a favourable post-fundoplication outcome in 12/14 patients with an abnormal Restech study preoperatively.15 Regarding the important placebo effect in this context, the results of these studies should be interpreted with caution. Prospective controlled outcome studies are mandatory to determine the relevance of this technique.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that pharyngeal pH alone is not reliable for the detection of pharyngeal reflux events and that adding distal oesophageal pH analysis is not helpful. The only reliable analysis should take into account impedance patterns demonstrating the presence of a pharyngeal reflux event preceded by a distal and proximal reflux event within the oesophagus.

Acknowledgements

The pH-impedance catheters were provided by Sandhill Scientific.

Funding

This study was funded by the Groupe Français de NeuroGastroentérologie (GFNG) and supported by the ‘Délégation à la Recherche Clinique et à l'Innovation’ of the Bordeaux University Hospital.

Conflict of interest

FZ has served as a speaker, a consultant and an advisory board member for Addex Pharma, Xenoport, Shire Movetis, Norgine, Astrazeneca, Janssen Cilag, Reckitt Benckiser, and Given Imaging. SR has served as speaker, consultant and advisory board member for Given Imaging. SBdV has served as a speaker, a consultant and an advisory board member for Shire Movetis, Astrazeneca, Janssen Cilag, and Given Imaging. FM has served as a speaker, a consultant and/or an advisory board member for Given Imaging, Medtronic, and Shire Movetis. GG has served as speaker, consultant and advisory board member for Reckitt Benckiser. BC served as a speaker, a consultant and advisory board member for Shire Movetis and Astra Zeneca. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Koufman JA, Aviv JE, Casiano RR, et al. Laryngopharyngeal reflux: position statement of the committee on speech, voice, and swallowing disorders of the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2002; 127: 32–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hicks DM, Ours TM, Abelson TI, et al. The prevalence of hypopharynx findings associated with gastroesophageal reflux in normal volunteers. J Voice 2002; 16: 564–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gatta L, Vaira D, Sorrenti G, et al. Meta-analysis: the efficacy of proton pump inhibitors for laryngeal symptoms attributed to gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007; 25: 385–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qadeer MA, Phillips CO, Lopez AR, et al. Proton pump inhibitor therapy for suspected GERD-related chronic laryngitis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Gastroenterol 2006; 101: 2646–2654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zerbib F, Sifrim D, Tutuian R, et al. Modern medical and surgical management of difficult-to-treat GORD. UEG Journal 2013; 1: 21–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Bortoli N, Nacci A, Savarino E, et al. How many cases of laryngopharyngeal reflux suspected by laryngoscopy are gastroesophageal reflux disease-related? World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18: 4363–4370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vaezi MF, Richter JE, Stasney CR, et al. Treatment of chronic posterior laryngitis with esomeprazole. Laryngoscope 2006; 116: 254–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zerbib F, Stoll D. Management of laryngopharyngeal reflux: an unmet medical need. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2010; 22: 109–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCollough M, Jabbar A, Cacchione R, et al. Proximal sensor data from routine dual-sensor esophageal pH monitoring is often inaccurate. Dig Dis Sci 2004; 49: 1607–1611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vaezi MF, Schroeder PL, Richter JE. Reproducibility of proximal probe pH parameters in 24-hour ambulatory esophageal pH monitoring. Am J Gastroenterol 1997; 92: 825–829 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams RB, Ali GN, Wallace KL, et al. Esophagopharyngeal acid regurgitation: dual pH monitoring criteria for its detection and insights into mechanisms. Gastroenterology 1999; 117: 1051–1061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ayazi S, Lipham JC, Hagen JA, et al. A new technique for measurement of pharyngeal pH: normal values and discriminating pH threshold. J Gastrointest Surg 2009; 13: 1422–1429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun G, Muddana S, Slaughter JC, et al. A new pH catheter for laryngopharyngeal reflux: normal values. Laryngoscope 2009; 119: 1639–1643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vailati C, Mazzoleni G, Bondi S, et al. Oropharyngeal pH monitoring for laryngopharyngeal reflux: is it a reliable test before therapy? J Voice 2013; 27: 84–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Worrell SG, Demeester SR, Greene CL, et al. Pharyngeal pH monitoring better predicts a successful outcome for extraesophageal reflux symptoms after antireflux surgery. Surg Endosc 2013; 27: 4113–4118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zerbib F, Roman S, Bruley Des Varannes S, et al. Normal values of pharyngeal and esophageal 24-hour pH impedance in individuals on and off therapy and interobserver reproducibility. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; 11: 366–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ummarino D, Vandermeulen L, Roosens B, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux evaluation in patients affected by chronic cough: Restech versus multichannel intraluminal impedance/pH metry. Laryngoscope 2013; 123: 980–984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]