Abstract

Background

The GerdQ scoring system may be a useful tool for managing gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. However, GerdQ has not been fully validated in Asian countries.

Objective

To validate the Japanese version of GerdQ and to compare this version to the Carlsson-Dent questionnaire (CDQ) in both general and hospital-based populations.

Methods

The questionnaires, including the Japanese versions of GerdQ and CDQ, and questions designed to collect demographic information, were sent to a general population via the web, and to a hospital-based population via conventional mail. The optimal cutoff GerdQ score and the differences in the characteristics between GerdQ and CDQ were assessed.

Results

The answers from 863 web-responders and 303 conventional-mail responders were analysed. When a GerdQ cutoff score was set at 8, GerdQ significantly predicted the presence of reflux oesophagitis. Although the GerdQ scores were correlated with the CDQ scores, the concordance rates were poor. Multivariate analysis results indicated that, the additional use of over-the-counter medications was associated with GerdQ score ≥ 8, but not with CDQ score ≥ 6.

Conclusions

The GerdQ cutoff score of 8 was appropriate for the Japanese population. Compared with CDQ, GerdQ was more useful for evaluating treatment efficacy and detecting patients’ unmet medical needs.

Keywords: Cutoff, GerdQ, GERD, questionnaire, unmet medical need

Introduction

The prevalence of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is dramatically increasing in both Western and Asian countries, including Japan.1 To diagnose GERD objectively, invasive examinations such as oesophagogastroduodenoscopy and pH monitoring can be employed. However, these methods are inconvenient to patients and have limited availability for primary care physicians. Therefore, the current guidelines recommend a symptom-based approach for diagnosis and treatment, especially in the primary care of young patients, who have a short disease history and no alarm symptoms.2 Primary care physicians experience the challenge of accurately diagnosing and effectively managing GERD with drugs that meet patients’ satisfaction.

GerdQ is a self-administered 6-item questionnaire that was recently developed as a tool to improve and standardize symptom-based diagnosis and evaluation of treatment response in patients with GERD.3 Norwegian researchers assessed the diagnostic validity of GerdQ, and they concluded that GerdQ is a useful, complementary tool for diagnosing GERD in primary care.4 They also reported that a symptom-based approach using GerdQ reduced healthcare costs without a loss in efficacy.5

In the development of GerdQ, GERD was diagnosed if patients fulfilled at least one of the following criteria: (i) oesophageal pH < 4 for >5.5% of a 24-h period, (ii) Los Angeles (LA) grade A−D oesophagitis at endoscopy, (iii) indeterminate 24-h oesophageal pH in combination with a positive response to 14 days’ esomeprazole treatment, and (iv) positive (>95) symptom association probability (SAP).3 This suggests that the GerdQ scores might be well correlated with the severity of acid reflux. In the East Asia and Pacific regions, lower gastric acid secretion is generally observed, and the prevalence of reflux oesophagitis is comparatively low.6–8 Therefore, the validation of GerdQ in Asian countries is important.

In the present study, we evaluated the usefulness of the Japanese version of GerdQ in two different Japanese populations: general and hospital-based populations. Among the hospital-based population, the association between the GerdQ score and the presence of reflux oesophagitis was assessed. In addition, to clarify the characteristics of GerdQ, the differences in the characteristics between the GerdQ and the Carlsson-Dent questionnaire (CDQ), which is a traditional questionnaire used for diagnosing GERD,9–11 were investigated.

Materials and methods

Study population

The present study was approved by the ethics committee of the Keio University School of Medicine (2010–319, 5 April 2011). The questionnaires, which comprised the Japanese versions of GerdQ and CDQ, demographic information (age, gender, smoking habits, alcohol consumption, height, weight, and past medical history), and treatment history for upper gastrointestinal symptoms involving prescription or over-the-counter (OTC) medicine use, were sent to both a web-based and conventional mail-surveyed population. Participants for the web-based survey were randomly selected from subjects who had registered with a web-survey company and who had a present or past history of heartburn and/or regurgitation. They provided informed consent by checking a web box. On the other hand, patients who underwent oesophagogastroduodenoscopy at the Keio University Hospital between December 2010 and May 2011 were enrolled in the mail survey. The mails were sent in June 2011. Participants with malignant diseases, peptic ulcers, a history of gastric surgery, or systematic diseases affecting the upper gastrointestinal tract were excluded. Participants with heartburn and/or regurgitation more frequently than once a week were defined as having GERD.12 The presence of erosive oesophagitis or positive proton pump inhibitor (PPI) response has not been taken into account for the diagnosis of GERD in the present study.

Individuals were categorized as ‘non-smokers’, ‘ex-smokers’, ‘1–15 cigarettes/day’, and ‘> 15 cigarettes/day’, according to the number of cigarettes consumed per day. With regard to alcohol consumption, individuals were categorized as ‘abstainers’, ‘social drinkers’, ‘stopped drinking’, ‘1–2 days/week’, ‘3–4 days/week’, and ‘5–7 days/week’, according to the number of days alcohol was consumed per week. Body mass index (BMI, weight/height2) was calculated. Participants were diagnosed with metabolic syndrome if they were overweight (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) or they had hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or dyslipidaemia, according to their responses on the questionnaire.13 For participants who responded via the mail survey, the severity of reflux oesophagitis was investigated using medical records.

Statistical analysis

Comparisons of two categorical variables such as gender and the presence/absence of diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, fatty liver, or the use of each medication were analysed using Fisher’s Exact test. Other categorical variables such as smoking and alcohol consumption were analysed using Pearson’s χ2 test. Continuous variables such as age and BMI were analysed using Student’s t-test. The cutoff value for the CDQ was set at 6, whereas the cutoff value of GerdQ was set at 8, in accordance with previous reports.3,9 The GerdQ cutoff value for predicting the presence of reflux oesophagitis was validated among the mail-surveyed population by using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis. Subsequently, the correlations between the CDQ and GerdQ scores were analysed using Pearson’s correlation analysis, and the concordance rates (kappa coefficient) were calculated between CDQ score ≥ 6 and GerdQ score ≥ 8. Finally, the associations of CDQ score ≥ 6 or GerdQ score ≥ 8 with demographic factors were analysed using univariate and multivariate logistic regression models. The multivariate logistic regression model was adjusted for age, gender, the presence of metabolic syndrome, and the use of both prescription and OTC medications. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics version 18.0 for Windows software (SPSS Japan, Tokyo, Japan). Two-sided p-values were considered statistically significant at a level of 0.05.

Results

Characteristics of participants

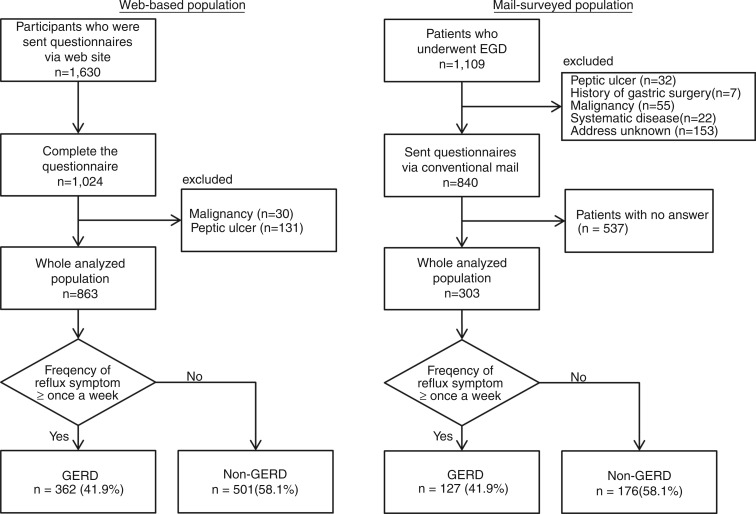

In the web survey, a total of 1630 participants were sent questionnaires, among which 1024 complete responses were received (Figure 1a). After excluding participants with malignant diseases (n = 30) and those with peptic ulcers (n = 131), the responses of the remaining 863 participants were used in the analysis. Among them, 362 participants were included in the GERD group. From the conventional mail survey, a total of 1109 patients were enrolled (Figure 1b). After excluding participants with peptic ulcers (n = 32), histories of gastric surgery (n = 7), malignant diseases (n = 55), severe systematic diseases (n = 22), and unknown addresses (n = 153), 840 patients were sent questionnaires along with an informed consent form; of these, 303 patients gave complete responses. Among the 303, 127 participants were included in the GERD group. Demographic characteristics of these two populations were totally different except for BMI, as shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

The web-based (a) and mail-surveyed (b) populations.

EGD, oesophagogastroduodenoscopy; GERD, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease.

Table 1.

Characteristics of analysed patients

| Web-based population |

Mail-survey population |

Web vs. mail |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole (n = 863) | Non-GERD (n = 501) | GERD (n = 362) | p-value | Whole (n = 303) | Non-GERD (n = 176) | GERD (n = 127) | p-value | p-value | |

| Age (years) | 41.1 ± 9.3 | 40.4 ± 9.4 | 41.9 ± 9.1 | 0.02a | 50.3 ± 15.4 | 51.2 ± 14.4 | 49.1 ± 16.3 | 0.02a | <0.001a |

| Gender | |||||||||

| Men | 391 (45.3) | 218 (43.5) | 173 (47.8) | 0.24b | 168 (55.4) | 100 (56.8) | 68 (53.5) | 0.64b | 0.003b |

| Women | 472 (54.7) | 283 (56.5) | 189 (52.2) | 135 (44.6) | 76 (43.2) | 59 (46.5) | |||

| Smoking habits | |||||||||

| Non-smokers | 409 (47.4) | 246 (49.1) | 163 (45.0) | 0.58c | 180 (59.4) | 112(64.0) | 68(53.5) | 0.13c | <0.001c |

| Ex-smokers | 253 (29.3) | 146 (29.1) | 107 (29.6) | 88 (29.1) | 47(26.9) | 41(32.3) | |||

| 1–15/day | 104 (12.1) | 57 (11.4) | 47 (13.0) | 11 (3.6) | 7(4.0) | 4(3.1) | |||

| > 15/day | 97 (11.2) | 52 (10.4) | 45 (12.4) | 23 (7.6) | 9(4.6) | 14(11.0) | |||

| Alcohol habits | |||||||||

| Abstainers | 161 (18.7) | 114 (22.8) | 47 (13.0) | 0.004c | 61 (20.1) | 29(16.6) | 32(25.2) | 0.22c | <0.001c |

| Social drinkers | 329 (38.1) | 182 (36.3) | 147 (40.6) | 89 (29.4) | 48(27.4) | 41(32.3) | |||

| Stop drinking | 43 (5.0) | 28 (5.6) | 15 (4.1) | 16 (5.3) | 9(5.1) | 7(5.5) | |||

| 1–2 days/week | 58 (6.7) | 36 (7.2) | 22 (6.1) | 46 (15.2) | 31(17.7) | 15(11.8) | |||

| 3–4 days/week | 76 (8.8) | 40 (8.0) | 36 (9.9) | 38 (12.5) | 26(14.9) | 12(9.4) | |||

| 5–7 days/week | 196 (22.7) | 101 (20.2) | 95 (26.2) | 52 (17.2) | 32(18.3) | 20(15.7) | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.2 ± 4.3 | 23.0 ± 4.3 | 23.4 ± 4.3 | 0.26a | 22.9 ± 7.8 | 22.9 ± 7.3 | 22.9 ± 8.3 | 0.99a | 0.27a |

| Diabetes mellitus | 33 (3.8) | 13 (2.6) | 20 (5.5) | 0.03b | 27 (8.9) | 16(9.1) | 11(8.7) | 1.00b | 0.001b |

| Hypertension | 101 (11.7) | 53 (10.6) | 48 (13.3) | 0.23b | 55 (18.2) | 32(18.1) | 23(18.1) | 1.00b | 0.01b |

| Dyslipidaemia | 75 (8.7) | 32 (6.4) | 43 (11.9) | 0.005b | 52 (17.2) | 32(18.1) | 20(15.7) | 0.65b | <0.001b |

| Fatty liver | 63 (7.3) | 34 (6.8) | 29 (8.0) | 0.50b | 37 (12.2) | 16(9.1) | 21(16.5) | 0.07b | 0.01b |

| Medications for upper gastrointestinal tract | |||||||||

| PPI | 42 (4.9) | 20 (4.0) | 22 (6.1) | 0.16b | 73 (24.1) | 35 (20.2) | 38 (30.6) | 0.04b | <0.001b |

| H2RA | 44 (5.1) | 17 (3.4) | 27 (7.5) | 0.007b | 34 (11.2) | 16 (9.2) | 18 (14.5) | 0.20b | <0.001b |

| Prokinetics | 24 (2.8) | 10 (2.0) | 14 (3.9) | 0.10b | 30 (9.9) | 9 (5.2) | 21 (17.1) | 0.001b | <0.001b |

| Others | 35 (4.1) | 16 (3.2) | 19 (5.2) | 0.08b | 35 (11.6) | 12 (7.0) | 23 (18.5) | 0.003b | <0.001b |

| OTC medications | 175 (20.3) | 55 (11.0) | 120 (33.1) | <0.001b | 30 (9.9) | 5 (2.8) | 25 (19.7) | <0.001b | <0.001b |

Values are mean ± standard deviation or n (%). aStudent’s t-test; bFisher’s Exact test; cPearson’s χ2 test.

BMI, body mass index; H2RA, histamine H2-receptor antagonist; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; OTC, over-the-counter.

Optimal cutoff value of GerdQ for the prediction of reflux oesophagitis

Among the 303 included mail respondents, 21 patients had LA grade A oesophagitis, 12 had LA grade B oesophagitis, one had LA grade C oesophagitis, one had LA grade D oesophagitis, and the remaining 268 patients did not have reflux oesophagitis. To validate the optimal cutoff value of GerdQ for predicting the presence of reflux oesophagitis, the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive values (PPVs), negative predictive values (NPVs), and area under the ROC curves (AUCs) were calculated (Table 2). When the cutoff value was set at 8, the PPV and AUC were the highest. A significant association between GerdQ-positive and the presence of reflux oesophagitis was also shown (p = 0.02). These results revealed that a cutoff value of 8 was also most predictive of reflux oesophagitis in Japanese population. In addition, GerdQ score ≥ 8 showed higher specificity, PPV, and AUC than CDQ score ≥ 6 (Table 2). These data indicated that GerdQ is more useful than CDQ for predicting the presence of reflux oesophagitis, although the sensitivity of GerdQ score ≥ 8 was low (34.3%).

Table 2.

Sensitivity and specificity of CDQ and GerdQ for the diagnosis of reflux oesophagitis among the mail-survey population (n = 303)

| Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | AUC | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDQ ≥ 6 | 51.4 | 61.9 | 15.0 | 90.7 | 0.567 | 0.14 |

| GerdQ ≥ 6 | 88.6 | 14.6 | 11.9 | 90.7 | 0.516 | 0.80 |

| GerdQ ≥ 7 | 42.9 | 70.5 | 16.0 | 90.4 | 0.567 | 0.12 |

| GerdQ ≥ 8 | 34.3 | 82.5 | 20.3 | 90.6 | 0.584 | 0.02 |

| GerdQ ≥ 9 | 17.1 | 89.6 | 17.6 | 89.2 | 0.533 | 0.25 |

p-values calculated using Fisher’s Exact test.

CDQ, Carlsson-Dent questionnaire; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value; AUC, area under the curve.

Differences in characteristics between CDQ score ≥ 6 and GerdQ score ≥ 8

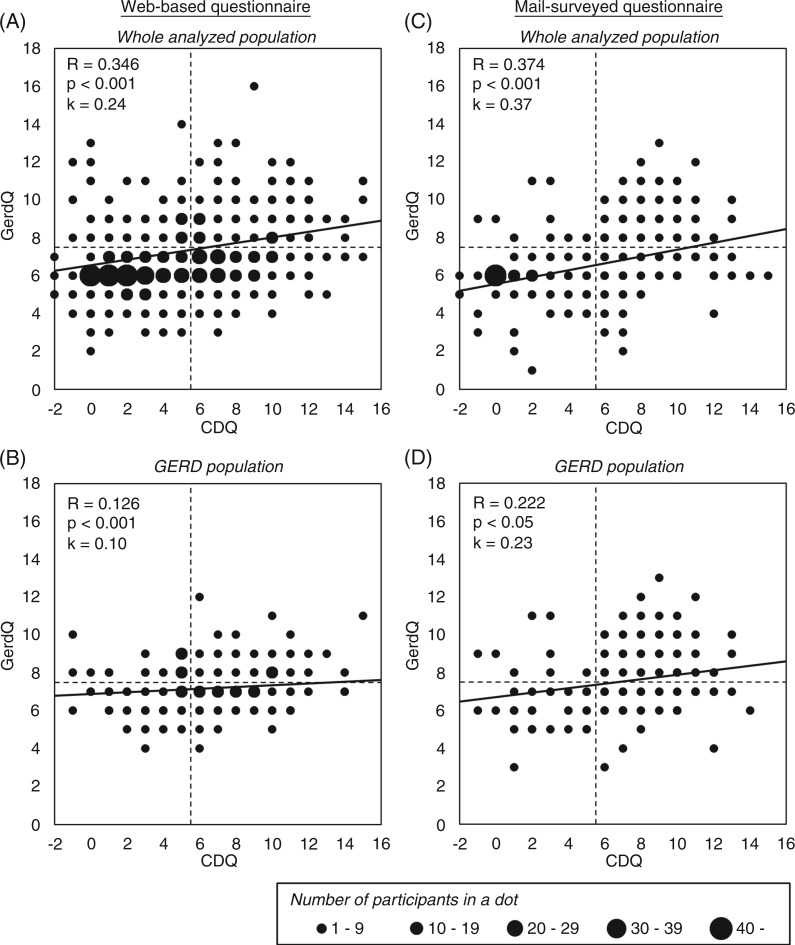

The GerdQ and CDQ scores were significantly correlated in both the web-based and mail-surveyed population (Figure 2). However, many participants showed CDQ score ≥ 6 and GerdQ score < 8, or CDQ score < 6 and GerdQ score ≥ 8, even in the GERD groups. This suggests that there are differences in the patient characteristics between populations of patients with CDQ score ≥ 6 and GerdQ score ≥ 8 populations. Since CDQ cutoff score is sometimes set at 4 in Japan, kappa coefficients between CDQ score ≥ 4 and GerdQ score ≥ 8 were also calculated. Using CDQ cutoff score of 6, kappa coefficients were 0.24 in web-based population and 0.27 in mail-surveyed population, whereas, using CDQ cutoff score of 4, kappa coefficients were 0.22 in web-based population and 0.25 in mail-surveyed population. All of the kappa coefficients were < 0.4, which indicates poor concordance.

Figure 2.

Correlation and concordance between CDQ and GerdQ scores in the total analysed population and in the GERD groups.

CDQ, Carlsson-Dent questionnaire; GERD, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease.

Therefore, the average score of each question of GerdQ was compared between participants with CDQ score ≥ 6 and CDQ score < 6 (Table 3). The scores of question 1, 2, 5, and 6 in GerdQ were significantly higher in CDQ score ≥ 6 than CDQ score < 6. On the other hand, the score of question 3 in GerdQ was significantly lower in CDQ score ≥ 6 than CDQ score < 6. The score of question 4 in GerdQ was not different between CDQ score ≥ 6 and CDQ score < 6. These showed that question 3 and 4 in GerdQ caused poor concordance about the diagnosis of GERD using GerdQ and CDQ.

Table 3.

Scores for each question of GerdQ in CDQ-positive and -negative participants

| Web-based population |

Mail-survey population |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDQ < 6 (n = 135) | CDQ ≥ 6 (n = 227) | p-value | CDQ < 6 (n = 40) | CDQ ≥ 6 (n = 87) | p-value | |

| GerdQ | ||||||

| 1. How often did you have a burning feeling behind your breastbone (heartburn)? | 0.38 ± 0.71 | 0.96 ± 0.89 | <0.001 | 0.14 ± 0.50 | 0.84 ± 0.93 | <0.001 |

| 2. How often did you have stomach contents (liquid or food) moving upwards to your throat or mouth (regurgitation)? | 0.36 ± 0.63 | 0.68 ± 0.80 | <0.001 | 0.26 ± 0.64 | 0.83 ± 0.92 | <0.001 |

| 3. How often did you have a pain in the centre of the upper stomach? | 2.65 ± 0.70 | 2.42 ± 0.83 | <0.001 | 2.66 ± 0.74 | 2.29 ± 0.91 | <0.001 |

| 4. How often did you have nausea? | 2.57 ± 0.74 | 2.53 ± 0.70 | 0.37 | 2.77 ± 0.66 | 2.74 ± 0.69 | 0.72 |

| 5. How often did you have difficulty getting a good night’s sleep because of your heartburn and / or regurgitation? | 0.18 ± 0.51 | 0.32 ± 0.63 | <0.001 | 0.06 ± 0.28 | 0.29 ± 0.63 | <0.001 |

| 6. How often did you take additional medication for your heartburn and / or regurgitation, other than what the physician told you to take? | 0.23 ± 0.65 | 0.49 ± 0.84 | <0.001 | 0.08 ± 0.39 | 0.33 ± 0.77 | <0.001 |

Values are mean ± standard deviation. p-values calculated using Student’s t-test.

CDQ, Carlsson-Dent questionnaire.

Subsequently, the associations of CDQ score ≥ 6 and GerdQ score ≥ 8 with demographic information were analysed among GERD groups using logistic regression models. The results of univariate analysis involving GERD patients responding to the web-based survey showed that, men and the presence of metabolic syndrome were associated with CDQ score ≥ 6, whereas older age, the presence of metabolic syndrome, and the use of both prescription and OTC medications were associated with GerdQ score ≥ 8 (Table 4). Among GERD patients in the mail-survey population, no association was observed between CDQ score ≥ 6 and demographic factors, whereas men and the presence of metabolic syndrome were associated with GerdQ score ≥ 8. The use of both prescription and OTC medications was marginally associated with a GerdQ score ≥ 8 (p = 0.06).

Table 4.

Association between the scores of CDQ and GerdQ and demographic factors among GERD patients (univariate analysis)

| Web-based population |

Mail-survey population |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDQ < 6 (n = 135) | CDQ ≥ 6 (n = 227) | OR (95% CI) | GerdQ< 8 (n = 183) | GerdQ ≥ 8 (n = 179) | OR (95% CI) | CDQ < 6 (n = 40) | CDQ ≥ 6 (n = 87) | OR (95% CI) | GerdQ < 8 (n = 71) | GerdQ ≥ 8 (n = 87) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Age (years) | 40.8 ± 9.2 | 42.6 ± 9.0 | 1.02 (1.00–1.05) | 40.2 ± 9.1 | 43.7 ± 8.8 | 1.05 (1.02–1.07) | 50.3 ± 6.0 | 48.5 ± 9.0 | 0.97 (0.93–1.02) | 49.1 ± 7.9 | 49.0 ± 8.6 | 1.00 (0.96–1.04) |

| Gender (men) | 52 (38.5) | 121 (53.3) | 1.82 (1.18–2.81) | 88 (48.1) | 85 (47.5) | 0.98 (0.65–1.48) | 22 (55.0) | 46 (52.9) | 0.92 (0.43–1.95) | 29 (40.8) | 39 (69.6) | 3.32 (1.58–6.97) |

| Heavy smoking (> 15/day) | 17 (12.6) | 28 (12.3) | 0.98 (0.51–1.86) | 20 (44.4) | 25 (55.6) | 1.32 (0.71–2.48) | 2 (5.0) | 12 (13.8) | 3.04 (0.65–14.3) | 7 (9.9) | 7 (12.5) | 1.31 (0.43–3.97) |

| Heavy alcohol consumption (5–7 days/week) | 28 (20.7) | 67 (29.5) | 1.60 (0.97–2.65) | 46 (25.1) | 49 (27.4) | 1.12 (0.70–1.79) | 6 (15.0) | 14 (16.1) | 1.09 (0.38–3.07) | 11 (15.5) | 9 (16.1) | 1.04 (0.40–2.73) |

| Metabolic syndrome | 49 (36.3) | 109 (48.0) | 1.62 (1.05–2.51) | 68 (37.2) | 90 (50.3) | 1.71 (1.13–2.60) | 20 (50.0) | 35 (40.2) | 0.67 (0.32–1.43) | 24 (33.8) | 31 (55.4) | 2.43 (1.18–4.99) |

| Using both prescription and OTC medications | 8 (5.9) | 26 (11.5) | 2.05 (0.90–4.68) | 6 (3.3) | 28 (15.6) | 5.47 (2.21–13.6) | 4 (10.0) | 7 (8.0) | 0.79 (0.22–2.86) | 3 (4.2) | 8 (14.3) | 3.78 (0.95–15.0) |

Values are mean ± SD or n (%), unless otherwise stated. Bold indicates significant differences.

CDQ, Carlsson-Dent questionnaire; OTC, over-the-counter.

Finally, multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed with adjustments for age, gender, the presence of metabolic syndrome, and the use of both prescription and OTC medications (Table 5). According to the multivariate analysis results, among GERD patients in the web-surveyed population, men were associated with CDQ score ≥ 6, whereas older age and the use of both prescription and OTC medications were independently associated with GerdQ score ≥ 8. Contrarily, among GERD patients in the mail-surveyed population, men and the use of both prescription and OTC medications were independently associated with GerdQ score ≥ 8. These results suggest that the use of both prescription and OTC medications would be associated with GerdQ score ≥ 8, but not CDQ score ≥ 6, in any population.

Table 5.

Association between the scores of CDQ and GerdQ and demographic factors among GERD patients (multivariate analysis)

| OR (95% CI) | Web-based population |

Mail-survey population |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDQ | GerdQ | CDQ | GerdQ | |

| Age | 1.01 (0.99–1.04) | 1.04 (1.02–1.07) | 0.98 (0.93–1.03) | 0.96 (0.92–1.02) |

| Gender (men) | 1.66 (1.05–2.61) | 0.78 (0.50–1.23) | 1.12 (0.49–2.54) | 3.66 (1.57–8.53) |

| Metabolic syndrome | 1.29 (0.80–2.07) | 1.38 (0.86–2.20) | 0.73 (0.32–1.68) | 1.88 (0.82–4.28) |

| Using both prescription and OTC medications | 1.96 (0.85–4.52) | 5.11 (2.04–12.8) | 0.87 (0.23–3.26) | 4.61 (1.06–20.2) |

Values are odds ratio (95% CI). Bold indicates significant differences.

CDQ, Carlsson-Dent questionnaire; OTC, over-the-counter.

Discussion

When the GerdQ was developed as an exploratory part of the DIAMOND study, a cutoff of 8 showed the highest specificity (71.4) and sensitivity (64.6) for GERD. The present study also showed that a GerdQ cutoff of 8 gave the best balance with regard to sensitivity and specificity for reflux oesophagitis in Japanese populations. The reason for the low positive predictive value (20.3) would be that the prevalence of reflux oesophagitis is low in GERD patients. Previous data showed that the prevalence of non-erosive reflux disease (NERD) in medical check-up studies was about 70−80% in Asian GERD population.14 Patients with GerdQ score ≥ 8 but without reflux oesophagitis were thought to be NERD patients.

According to the univariate logistic regression analysis, the presence of metabolic syndrome was associated with GerdQ score ≥ 8 in both the web- and mail-surveyed populations. Because metabolic syndrome is well known to be associated with the development and progression of GERD,15 the association between GerdQ score ≥ 8 and metabolic syndrome also suggests that GerdQ is useful for diagnosing GERD in Japanese individuals. On the other hand, CDQ score ≥ 6 was also associated with the presence of metabolic syndrome in the web-surveyed population, but not in mail-surveyed population. CDQ cannot be used to distinguish between GERD and functional heartburn,16 and functional heartburn is not associated with metabolic syndrome.17 CDQ score ≥ 6 was not associated with metabolic syndrome in the mail-surveyed population because more patients with functional heartburn were included in the population. In addition, epigastric pain (question 3 in GerdQ) was more frequent in participants with CDQ score ≥ 6 than those with CDQ score < 6, suggesting that participants with CDQ score ≥ 6 were likely to have functional dyspepsia. These results suggest that GerdQ would be more useful for distinguishing between GERD and functional upper gastrointestinal disorders (heartburn and dyspepsia) than CDQ. However, GerdQ has limitations to distinguish between GERD and functional heartburn. Although positive PPI response and SAP were taken into account to diagnose GERD in the development of GerdQ, some researchers have reported that positive PPI response cause overestimation of functional heartburn patients.18,19 SAP might be overinterpreted in patients with refractory GERD especially when low reflux rates are observed.20 In addition, nonacid reflux, which is reported to be involved in the development of reflux symptoms, was not taken into account in GerdQ.21 Therefore, to validate how useful for distinguishing between GERD and functional heartburn, GerdQ should be evaluated using combined impedance pH monitoring.

According to the multivariate logistic regression analysis, the additional use of OTC medications was well associated with GerdQ score ≥ 8 in both populations. The additional use of OTC medications may indicate that prescription medicines are inadequate for treating reflux symptoms. This result suggests that the GerdQ would be useful for evaluating treatment response and for detecting unmet medical needs.

Limitations of the present study include the absence of pH monitoring for the mail-surveyed population. The pH monitoring data might have revealed the prevalence of NERD and functional heartburn in this population, and the optimal cutoff value of GerdQ and the differences between GerdQ and CDQ might have been more clearly evaluated. The low response rate for the questionnaires in the mail-surveyed population might have caused selection bias.

In conclusion, the present study is the first study to evaluate the usefulness of GerdQ in Japanese population. The GerdQ cutoff score of 8 was found to also be appropriate for the Japanese population. The GerdQ was better able to detect unmet therapeutic needs. Symptom-based management of GERD using GerdQ would be beneficial in Japan, as was revealed in Western countries.

Funding

This study was supported in part by the Smoking Research Foundation (to HS), the Keio Gijuku Academic Development Fund (No. 24-24, to HS), a Keio University Grant-in-Aid for Encouragement of Young Medical Scientists (to JM), and a grant from AstraZeneca K.K.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Fujiwara Y, Arakawa T. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of GERD in the Japanese population. J Gastroenterol 2009; 44: 518–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kahrilas PJ, Shaheen NJ, Vaezi MF, et al. American Gastroenterological Association Medical Position Statement on the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology 2008; 135: 1383–1391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones R, Junghard O, Dent J, et al. Development of the GerdQ, a tool for the diagnosis and management of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in primary care. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009; 30: 1030–1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jonasson C, Wernersson B, Hoff DA, et al. Validation of the GerdQ questionnaire for the diagnosis of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jonasson C, Moum B, Bang C, et al. Randomised clinical trial: a comparison between a GerdQ-based algorithm and an endoscopy-based approach for the diagnosis and initial treatment of GERD. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2012; 35: 1290–1300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong BC, Kinoshita Y. Systematic review on epidemiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease in Asia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006; 4: 398–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kinoshita Y, Kawanami C, Kishi K, et al. Helicobacter pylori independent chronological change in gastric acid secretion in the Japanese. Gut 1997; 41: 452–458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kinoshita Y, Adachi K, Hongo M, et al. Systematic review of the epidemiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease in Japan. J Gastroenterol 2011; 46: 1092–1103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carlsson R, Dent J, Bolling-Sternevald E, et al. The usefulness of a structured questionnaire in the assessment of symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease. Scand J Gastroenterol 1998; 33: 1023–1029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mishima I, Adachi K, Arima N, et al. Prevalence of endoscopically negative and positive gastroesophageal reflux disease in the Japanese. Scand J Gastroenterol 2005; 40: 1005–1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iwasaki E, Suzuki H, Sugino Y, et al. Decreased levels of adiponectin in obese patients with gastroesophageal reflux evaluated by videoesophagography: possible relationship between gastroesophageal reflux and metabolic syndrome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008; 23(Suppl 2): S216–S221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, et al. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol 2006; 101: 1900–1920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alberti KG, Zimmet P, Shaw J. The metabolic syndrome − a new worldwide definition. Lancet 2005; 366: 1059–1062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jung HK. Epidemiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease in Asia: a systematic review. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2011; 17: 14–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee YC, Yen AM, Tai JJ, et al. The effect of metabolic risk factors on the natural course of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Gut 2009; 58: 174–181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Netinatsunton N, Attasaranya S, Ovartlarnporn B, et al. The value of Carlsson-dent questionnaire in diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease in area with low prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2011; 17: 164–168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsuzaki J, Suzuki H, Iwasaki E, et al. Serum lipid levels are positively associated with non-erosive reflux disease, but not with functional heartburn. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2010; 22: 965–970, e251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zerbib F, Belhocine K, Simon M, et al. Clinical, but not oesophageal pH-impedance, profiles predict response to proton pump inhibitors in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Gut 2012; 61: 501–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Savarino E, Marabotto E, Zentilin P, et al. The added value of impedance-pH monitoring to Rome III criteria in distinguishing functional heartburn from non-erosive reflux disease. Dig Liver Dis 2011; 43: 542–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Slaughter JC, Goutte M, Rymer JA, et al. Caution about overinterpretation of symptom indexes in reflux monitoring for refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 9: 868–874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Savarino E, Tutuian R, Zentilin P, et al. Characteristics of reflux episodes and symptom association in patients with erosive esophagitis and nonerosive reflux disease: study using combined impedance-pH off therapy. Am J Gastroenterol 2010; 105: 1053–1061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]