Abstract

Background

Prucalopride is a selective, high-affinity, 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) type 4 (5-HT4) receptor agonist with gastrointestinal prokinetic activities. This integrated analysis of data from three double-blind phase III trials (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT00488137, NCT00483886, NCT00485940) compared the efficacy and safety of prucalopride 2 mg once daily in women with chronic constipation [≤2 spontaneous complete bowel movements (SCBM) per week] in whom laxatives had failed to provide adequate relief with that in the all-patient (AP) population of men and women with chronic constipation who had or had not obtained relief from laxatives.

Methods

Patients received prucalopride 2 mg or placebo once-daily for 12 weeks. Efficacy endpoints included an average of ≥3 SCBM/week and average increases of ≥1 SCBM/week and ≥1 SBM/week over this period. A response on any of these three endpoints was considered to be clinically relevant, and an overall response rate was derived for patients satisfying any of these endpoints.

Results

Of the AP population (n = 1318), 936 were women in whom laxatives had failed to provide adequate relief (WLF). More patients on prucalopride 2 mg than placebo had an average of ≥3 SCBM/week (AP 24.4 vs 11.0%; WLF 24.7 vs 9.2%), an average increase of ≥1 SCBM/week (AP 43.5 vs 24.8%; WLF 44.2 vs 22.6%), and an average increase of ≥1 SBM/week (AP 66.7 vs 38.4%; WLF 68.3 vs 37.0%) (all p < 0.001). Significant differences from placebo were evident in week 1 and sustained thereafter. Overall response rates in the AP and WLF populations, respectively, were 69.7 and 71.0% with prucalopride 2 mg and 44.5 and 41.6% with placebo (p < 0.001). Early (weeks 1–4) response predicted ultimate response over time. Common (>10%) adverse events were abdominal pain, nausea, diarrhoea, and headache.

Conclusions

Prucalopride 2 mg once daily is effective in WLF. The efficacy and safety profile observed in WLF was similar to that in the total evaluated population of patients with chronic constipation who had or had not obtained adequate relief from laxatives.

Keywords: 5-HT4 agonist, efficacy, safety, serotonergic

Background

Constipation is a common and often chronic gastrointestinal problem. It is now recognized that constipation is not just a simple reduction in stool frequency but rather a condition featuring multiple symptoms.1–4 The most commonly cited diagnostic criteria for chronic constipation are the Rome III criteria, that is two or more of the following for at least 3 months (with symptom onset at least 6 months prior to diagnosis): fewer than three bowel movements per week and/or at least 25% of defaecations with straining, lumpy or hard stools, sensation of incomplete evacuation, sensation of anorectal obstruction or blockage, or manual manoeuvres to facilitate defaecation.4

Dietary and lifestyle measures are usually the interventions of first choice. If these measures fail, prescription or over-the-counter laxatives with different mechanisms of action may be used.5,6 However, many of these available therapies do not target the underlying cause(s) of constipation or adequately relieve all constipation-related symptoms (e.g. bloating, straining, lumpy or hard stools, incomplete evacuation).7,8 Furthermore, data from well-designed controlled trials to support the efficacy of traditional therapies are limited and, typically, are based on small sample sizes and short treatment durations (4 weeks).5,6 The implications of longer-term treatment with available therapies in chronic constipation are therefore unclear.5

Prucalopride is a selective, high-affinity 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) type 4 (5-HT4) receptor agonist. The high affinity and selectivity for the 5-HT4 receptor likely explains its gastrointestinal prokinetic activities and also differentiates prucalopride from previous-generation compounds like cisapride and tegaserod, by minimizing the potential for target-unrelated side effects.9–11 Its mechanism of action includes stimulation of colonic contractions, especially high-amplitude propagated contractions that are closely associated with defaecation.12 In the European Union, prucalopride succinate tablets (Resolor) are currently approved for the symptomatic treatment of chronic constipation in women in whom laxatives fail to provide adequate relief. The recommended dose for adult patients is 2 mg once daily.13

The results of three identical pivotal phase III trials in men and women with chronic constipation showed that once-daily treatment with prucalopride for 12 weeks improved bowel function, symptoms of constipation, and patient satisfaction with bowel function and treatment.14–16 The primary endpoint in these trials was an average of three or more spontaneous complete bowel movements per week, over the 12-week treatment period. This endpoint was based on a combination of an objective (number of bowel movements) and a subjective (complete evacuation) measure, and, thus, identified changes that are relevant to the patient.14,16,17

A pertinent clinical question that arises in relation to any new treatment for constipation is whether it will work among those who have failed conventional approaches. The aim of the present integrated analysis, therefore, was to compare the observed efficacy and safety of prucalopride 2 mg once daily in women in the pivotal trials in whom laxatives had failed to provide adequate relief (i.e. the population for which prucalopride treatment is currently indicated in the European Union13) with the observed efficacy and safety in the all-patient population of men and women who had or had not obtained relief from laxatives. Considering that a clinically relevant improvement can also be present in patients who do not meet the stringent criteria of the primary endpoint but satisfy other endpoints, an overall response rate was derived for patients satisfying any of three predefined clinical endpoints to enable the overall treatment effect to be compared. The efficacy of prucalopride over time and the impact of adherence to the recommended once-daily dose regimen were also evaluated.

Methods

Data were pooled from three multicentre, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trials [trial IDs: PRU-INT-6 (NCT00488137), PRU-USA-11 (NCT00483886), and PRU-USA-13 (NCT00485940)]. The methodology for the trials has previously been described elsewhere in detail14–16 and is briefly summarized below. The protocols and amendments were reviewed by an independent institutional review board or independent ethics committee. The trials were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, good clinical practice guidelines, and local laws and regulations. All patients gave written informed consent before trial entry.

Study design

The original trials consisted of a 2-week, drug-free run-in period followed by a 12-week, double-blind treatment period including both men and women. Following the drug-free run-in period, all patients were randomly assigned to double-blind treatment with placebo or prucalopride 2 mg or 4 mg once daily for 12 weeks. Only patients receiving placebo or the recommended dose of 2 mg once daily were included in the integrated analysis presented here.

If patients did not have a bowel movement for three or more consecutive days, they were allowed to take bisacodyl (Dulcolax®; Boehringer Ingelheim) as rescue medication, up to a maximum dose of 15 mg. If this standard dose was insufficient, an increase in dose was permitted, but only after the patient had consulted the investigator. If no bowel movements were passed after an increase in the bisacodyl dose, an enema could be administered. The use of bisacodyl and enemas had to be documented in a patient diary.

Study populations

Each trial enrolled outpatients aged 18 years and older with a history of chronic constipation, defined as having two or fewer spontaneous complete bowel movements per week for at least 6 months prior to trial entry. Patients also had to have hard or very hard stools, a sensation of incomplete evacuation, or straining during defaecation with at least 25% of stools. A bowel movement was considered ‘spontaneous’ when it occurred more than 24 hours following the last intake of a laxative or use of an enema. Patients with chronic constipation attributable to a secondary cause were excluded.

In the integrated analysis presented here, data from the all-patient population comprising all male and female patients, who had or had not obtained adequate relief from laxatives, were compared with data from all the female patients in whom laxatives had failed to provide adequate relief. The response to previous laxatives was assessed by asking all patients who entered the trials whether they had used dietary measures, bulk-forming agents, and/or other laxatives to treat constipation in the previous 6 months and, if so, whether they would rate the overall therapeutic effect of these measure(s) as ‘adequate’ or ‘inadequate’. No details on the type of laxatives were collected.

Data collection and endpoints

Efficacy data were collected by means of a patient diary to record medication intake, stool frequency, and stool characteristics throughout the run-in period and 12-week double-blind treatment period. The following endpoints were derived from these diaries: the proportion of patients with an average of three or more spontaneous complete bowel movements per week (the primary endpoint in the three pivotal trials); the proportion of patients with an average increase of one or more spontaneous complete bowel movements per week compared with run-in; the proportion of patients with an average increase of one or more spontaneous bowel movements per week compared with run-in; the average number of spontaneous complete bowel movements per week; the proportion of (spontaneous) bowel movements with normal consistency, no straining, or a sensation of complete evacuation; the median time to the first spontaneous (complete) bowel movement after the first intake of trial medication; and the average number of bisacodyl tablets taken per week.

Taking into account that clinically relevant improvements can also be present in patients who do not respond on the primary endpoint but satisfy other endpoints, a response on any of the following three endpoints was considered to be clinically relevant (i.e. beneficial) to the patient. Therefore, an overall response rate was derived for patients satisfying any of these three endpoints over 12 weeks of treatment: an average of three or more spontaneous complete bowel movements per week, an average increase of one or more spontaneous complete bowel movements per week compared with run-in, or an average increase of one or more spontaneous bowel movements per week compared with run-in.

Safety was monitored throughout the trials, through assessment of adverse events, vital signs (blood pressure and pulse rate), physical examination, clinical laboratory tests (haematology, biochemistry and urinalysis), and electrocardiogram parameters (heart rate, PR interval, QRS width, QT interval, and corrected QT interval using Bazett’s and Fridericia’s formulae).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with Statistical Analysis System version 8 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Within each population (all-patient and women in whom laxatives had failed to provide adequate relief), the safety analysis comprised all patients who took at least one dose of trial medication (prucalopride 2 mg or placebo) and the efficacy analysis comprised all patients who took at least one dose of trial medication and had any post-baseline efficacy data.

The Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test, controlling for trial, was used to test differences in binary endpoints (response rates) between treatment groups. For continuous data, analysis of covariance was used (including factors for treatment, baseline value and trial) to evaluate differences between treatment groups.

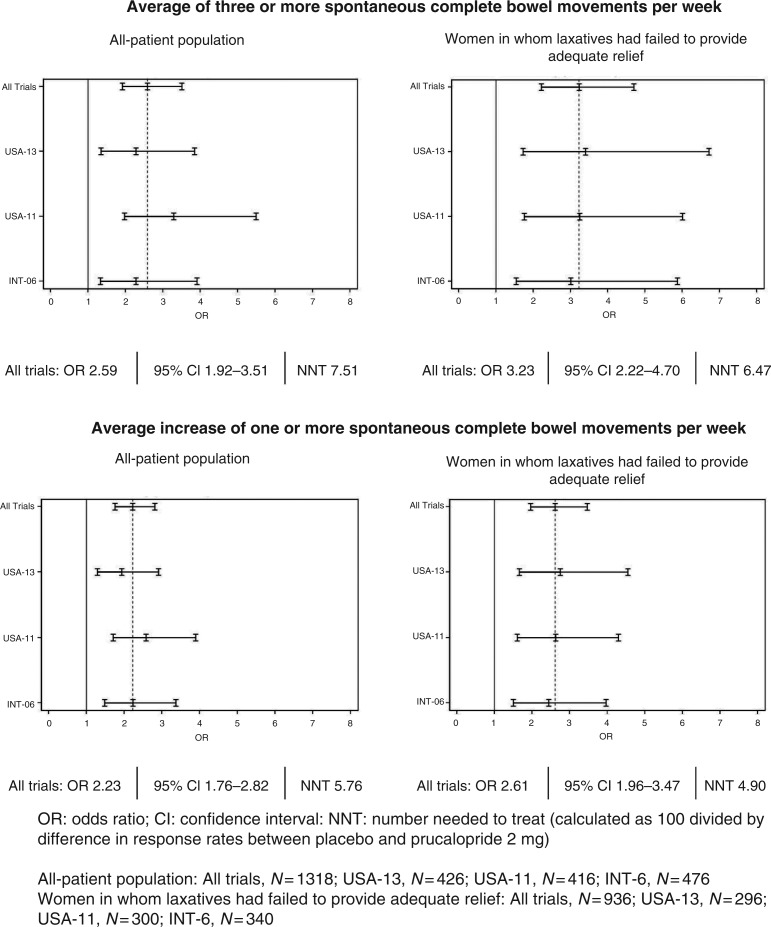

Forest plots were created to visualize and compare treatment effect sizes in the individual trials and the combined trials for both the all-patient population and the population of women in whom laxatives had failed to provide adequate relief. The effect sizes are presented as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals for the following endpoints: an average of three or more spontaneous complete bowel movements per week and an average increase of one or more spontaneous complete bowel movements per week, over 12 weeks of treatment. Numbers needed to treat are provided for the combined trials.

To evaluate whether missing doses of prucalopride compromised its efficacy, the within-patient difference was calculated for the average number of spontaneous complete bowel movements, spontaneous bowel movements, and bowel movements (spontaneous/non-spontaneous) per week during weeks when prucalopride was taken every day vs weeks where at least 2 days of intake were missed. Weeks with no intake at all or only a single intake were also taken into account. Statistical comparison was performed using the paired t-test.

All reported p-values are two-sided and tests were performed with a 5% level of significance.

Results

Patient disposition

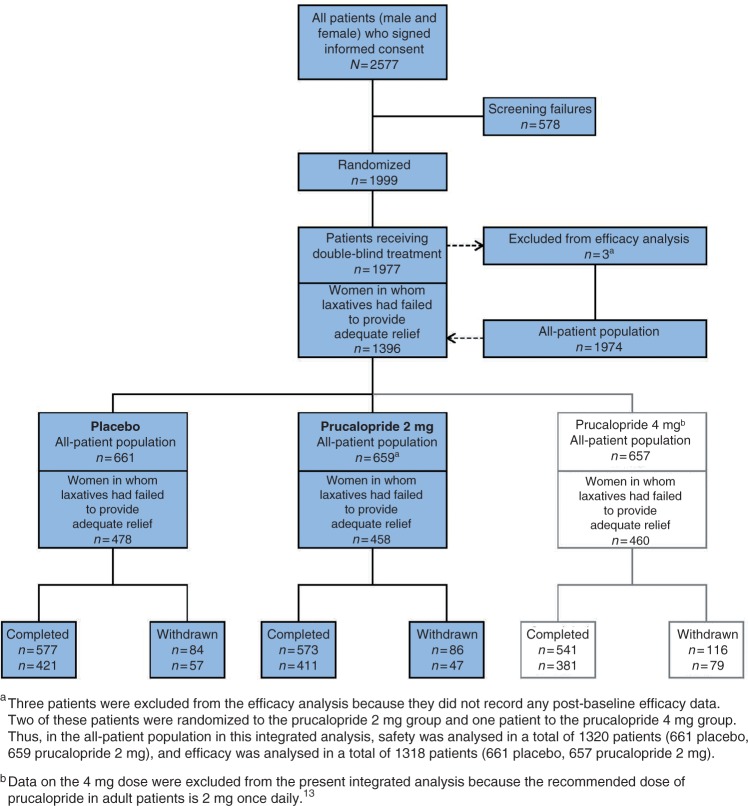

A total of 1999 male and female patients were randomly assigned in the three trials to receive either placebo, prucalopride 2 mg or prucalopride 4 mg once daily. Twenty-two patients discontinued before the start of treatment and three patients did not record any post-baseline efficacy data; two of these three patients were randomized to prucalopride 2 mg and one was randomized to prucalopride 4 mg. Of the 1974 remaining patients with efficacy data (all-patient population), 1396 were women in whom laxatives had failed to provide adequate relief (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Patient disposition.

In the all-patient population, 657 patients with efficacy data had received prucalopride 2 mg and 661 patients with efficacy data had received placebo, providing a study population for this integrated analysis of 1318 patients. In the population of women in whom laxatives had failed to provide adequate relief, 458 patients received prucalopride 2 mg and 478 patients received placebo, providing a study population for this integrated analysis of 936. Almost 90% of the patients receiving prucalopride 2 mg or placebo in either population completed the trials (Figure 1). Adverse events were the most common reason for early trial discontinuation (3.8–6.2% of patients).

Demographics and constipation characteristics

Demographics and constipation characteristics recorded at screening (prior to run-in) were well balanced between treatment groups and between the all-patient population and women in whom laxatives had failed to provide adequate relief (Table 1). Patients were predominantly Caucasian (90.1–92.5%), had a mean age of 44.5–46.3 years and a mean duration of constipation of 19.6–20.8 years. The most common constipation-related complaints at trial entry were (in order of decreasing frequency): infrequent defaecation, abdominal bloating, abdominal pain, feeling not completely empty, straining, and hard stools. Most patients had used a combination of dietary measures, bulk-forming agents, and/or other laxatives to treat their constipation. Only 3.2% (42/1320) of patients in the all-patient population and 3.6% (34/936) of patients in the population of women in whom laxatives had failed to provide adequate relief had used dietary measures alone.

Table 1.

Demographics and constipation characteristics at screening (prior to run-in)

| All-patient population |

Women in whom laxatives had failed to provide adequate relief |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Placebo (n = 661) | Prucalopride 2 mg (n = 659) | Placebo (n = 478) | Prucalopride 2 mg (n = 458) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| Black | 29 (4.4) | 40 (6.1) | 19 (4.0) | 27 (5.9) |

| Caucasian | 605 (91.5) | 594 (90.1) | 442 (92.5) | 418 (91.3) |

| Hispanic | 11 (1.7) | 8 (1.2) | 8 (1.7) | 7 (1.5) |

| Oriental | 4 (0.6) | 9 (1.4) | 4 (0.8) | 4 (0.9) |

| Other | 12 (1.8) | 8 (1.2) | 5 (1.0) | 2 (0.4) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Female | 594 (89.9) | 582 (88.3) | 478 (100) | 458 (100) |

| Male | 67 (10.1) | 77 (11.7) | 0 | 0 |

| Age (years) | ||||

| Mean ± SE | 46.1 ± 0.54 | 46.3 ± 0.57 | 45.4 ± 0.62 | 44.5 ± 0.65 |

| Median (range) | 45 (18–82) | 45 (17–95) | 44 (18–81) | 44 (17–95) |

| Height (cm) | ||||

| Mean ± SE | 165.1 ± 0.32 | 165.3 ± 0.33 | 164.2 ± 0.33 | 163.7 ± 0.34 |

| Median (range) | 165 (107–196) | 165 (132–193) | 165 (125–191) | 164 (132–188) |

| Weight (kg) | ||||

| Mean ± SE | 68.5 ± 0.55 | 69.7 ± 0.57 | 66.5 ± 0.59 | 67.2 ± 0.62 |

| Median (range) | 65 (42–131) | 67 (40–141) | 64 (42–131) | 65 (40–141) |

| Reported duration of constipation (years) | ||||

| Mean ± SE | 20.4 ± 0.60 | 19.7 ± 0.61 | 20.8 ± 0.69 | 19.6 ± 0.70 |

| Range | 0.5–77 | 0.5–70 | 0.5–69 | 0.5–63 |

| Reported main complaints, n (%)a | ||||

| Infrequent defaecation | 191 (28.9) | 209 (31.7) | 134 (28.0) | 143 (31.2) |

| Abdominal bloating | 167 (25.3) | 156 (23.7) | 127 (26.6) | 114 (24.9) |

| Abdominal pain | 99 (15.0) | 103 (15.6) | 77 (16.1) | 77 (16.8) |

| Feeling not completely empty | 97 (14.7) | 85 (12.9) | 71 (14.9) | 59 (12.9) |

| Straining | 71 (10.7) | 68 (10.3) | 43 (9.0) | 41 (9.0) |

| Hard stools | 36 (5.4) | 38 (5.8) | 26 (5.4) | 24 (5.2) |

| Reported use of laxatives in the previous 6 months, n (%) | ||||

| Dietary | 421 (63.7) | 443 (67.2) | 327 (68.4) | 341 (74.5) |

| Bulk-forming | 401 (60.7) | 402 (61.0) | 313 (65.5) | 301 (65.7) |

| Other laxatives | 570 (86.2) | 565 (85.7) | 421 (88.1) | 403 (88.0) |

| Patient perception of efficacy of laxatives, n (%) | ||||

| Adequate | 110 (17.2) | 121 (18.9) | 0 | 0 |

| Inadequate | 528 (82.8) | 518 (81.1) | 478 (100) | 458 (100) |

SE, standard error.

Main complaints are presented in order of decreasing frequency. Patients could report more than one complaint.

During the run-in period, 82.4–84.3% of patients in the prucalopride 2 mg and placebo groups of either population (all-patient and women in whom laxatives had failed to provide adequate relief) reported an average of one or fewer spontaneous complete bowel movements per week, and another 58.2–62.2% of patients passed no spontaneous complete bowel movements during run-in. A total of 24.3–30.9% of patients reported an average of one or fewer spontaneous bowel movements per week (Additional File 1, available online). Sixty per cent of patients rated their constipation ‘severe’ or ‘very severe’ on a 5-point scale ranging from absent to very severe.

Efficacy

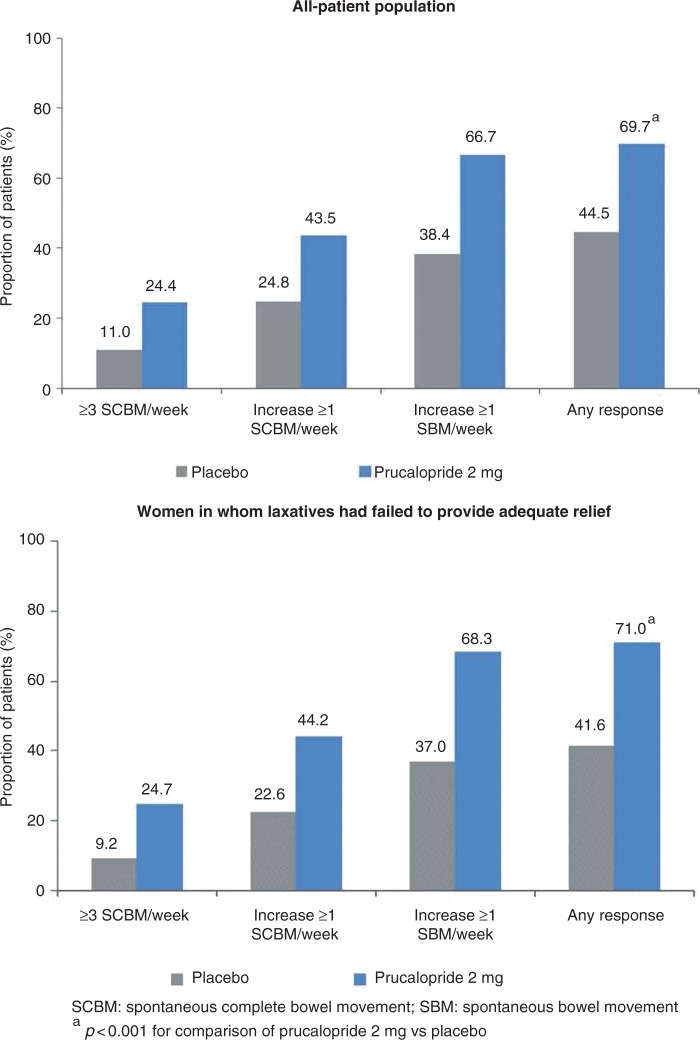

In both populations, the proportion of patients with an average of three or more spontaneous complete bowel movements per week over the 12-week treatment period was significantly (p < 0.001) higher in the prucalopride group than in the placebo group (all-patient 24.4 vs 11.0%; women in whom laxatives had failed to provide adequate relief 24.7 vs 9.2%). Similarly, in both populations, significantly (p < 0.001) more patients in the prucalopride group than in the placebo group had an average increase of one or more spontaneous complete bowel movements per week (all-patient 43.5 vs 24.8%; women in whom laxatives had failed to provide adequate relief 44.2 vs 22.6%) and an average increase of one or more spontaneous bowel movements per week (all-patient 66.7 vs 38.4%; women in whom laxatives had failed to provide adequate relief 68.3 vs 37.0%) over 12 weeks of treatment (Table 2). The overall response rate for patients satisfying any of these endpoints was 69.7% (all-patient) and 71.0% (women in whom laxatives had failed to provide adequate relief) with prucalopride, compared with 44.5% (all-patient) and 41.6% (women in whom laxatives had failed to provide adequate relief) with placebo (p < 0.001) (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Endpoints from patient diaries. Values are shown as n: number of evaluable patients (responder rate %) unless otherwise stated

| All-patient population |

Women in whom laxatives had failed to provide adequate relief |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 661) | Prucalopride 2 mg (n = 657) | Placebo (n = 478) | Prucalopride 2 mg (n = 458) | |||||

| Average of ≥3 spontaneous complete bowel movements per week | ||||||||

| Weeks 1–4 | 661 | (10.6) | 657 | (28.5)a | 478 | (8.6) | 458 | (31.0)a |

| Weeks 1–12 | 661 | (11.0) | 657 | (24.4)a | 478 | (9.2) | 458 | (24.7)a |

| Average increase of ≥1 spontaneous complete bowel movements per week compared with run-in | ||||||||

| Weeks 1–4 | 648 | (23.3) | 629 | (48.6)a | 466 | (21.7) | 439 | (51.0)a |

| Weeks 1–12 | 645 | (24.8) | 628 | (43.5)a | 465 | (22.6) | 439 | (44.2)a |

| Average increase of ≥1 spontaneous bowel movements per week compared with run-in | ||||||||

| Weeks 1–4 | 648 | (42.1) | 629 | (76.3)a | 466 | (39.9) | 439 | (77.4)a |

| Weeks 1–12 | 645 | (38.4) | 628 | (66.7)a | 465 | (37.0) | 439 | (68.3)a |

| Spontaneous complete bowel movements per week: n (mean) or n (mean, mean change from run-in) | ||||||||

| Run-in | 659 | (0.4) | 655 | (0.4) | 476 | (0.4) | 457 | (0.4) |

| Weeks 1–4 | 648 | (1.0, 0.58) | 629 | (2.1, 1.69)a | 466 | (0.9, 0.52) | 439 | (2.2, 1.80)a |

| Weeks 1–12 | 645 | (1.1, 0.68) | 628 | (1.9, 1.52)a | 465 | (1.0, 0.63) | 439 | (2.0, 1.60)a |

| Bowel movements (spontaneous/non-spontaneous) with normal consistency | ||||||||

| Run-in | 658 | (22.2) | 654 | (22.8) | 475 | (22.8) | 456 | (22.2) |

| Weeks 1–4 | 648 | (32.9) | 629 | (39.8)a | 466 | (31.7) | 439 | (40.1)a |

| Weeks 1–12 | 645 | (34.9) | 628 | (43.0)a | 465 | (33.5) | 439 | (42.7)a |

| Bowel movements (spontaneous/non-spontaneous) with no straining | ||||||||

| Run-in | 658 | (20.1) | 654 | (20.2) | 475 | (19.2) | 456 | (19.7) |

| Weeks 1–4 | 648 | (17.9) | 629 | (23.3)a | 466 | (17.7) | 439 | (22.8)a |

| Weeks 1–12 | 645 | (18.6) | 628 | (21.8)b | 465 | (18.1) | 439 | (21.5)b |

| Bowel movements (spontaneous/non-spontaneous) with complete evacuation | ||||||||

| Run-in | 658 | (19.4) | 654 | (17.5) | 475 | (17.6) | 456 | (16.4) |

| Weeks 1–4 | 648 | (24.5) | 629 | (29.2)a | 466 | (22.6) | 439 | (29.4)a |

| Weeks 1–12 | 645 | (26.9) | 628 | (30.6)a | 465 | (24.7) | 439 | (30.9)a |

| Average no. of bisacodyl tablets taken per week: n (mean) or n (mean, mean change from run-in) | ||||||||

| Run-in | 659 | (2.1) | 655 | (1.9) | 476 | (2.2) | 457 | (1.9) |

| Weeks 1–4 | 648 | (2.0, −0.16) | 629 | (1.0, −0.94)a | 466 | (2.1, −0.12) | 439 | (1.0, −0.99)a |

| Weeks 1–12 | 605 | (1.9, −0.14) | 601 | (1.1, −0.86)a | 435 | (2.1, −0.11) | 426 | (1.1, −0.89)a |

| Time (h) to first spontaneous complete bowel movement: median (25%; 75% quartiles) | ||||||||

| After first dose | 384.75 | (86.00; –) | 54.50 | (4.17; 648.75)c | 441.33 | (106.00; –) | 50.88 | (4.08; 651.50)c |

| Time (h) to first spontaneous bowel movement: median (25%; 75% quartiles) | ||||||||

| After first dose | 26.50 | (4.73; 97.63) | 2.50 | (1.08; 13.25)c | 26.77 | (5.00; 99.25) | 2.46 | (1.08; 14.95)c |

ap < 0.0001 (chi-squared), bp < 0.001, cp < 0.01 for comparison of prucalopride 2 mg vs placebo.

Figure 2.

Cumulative overall response rate at week 12.

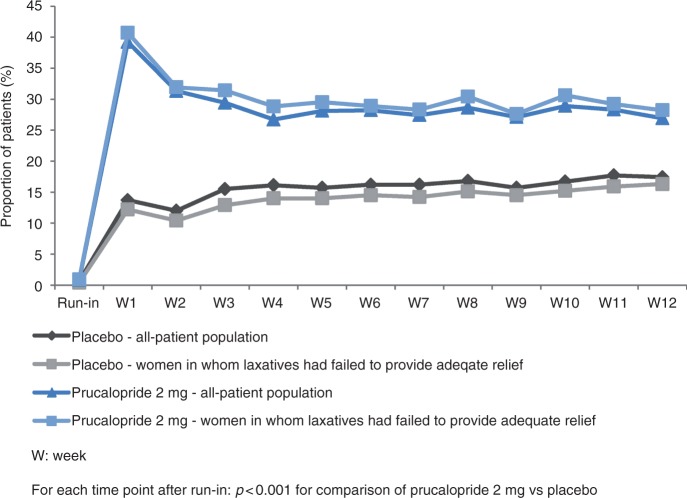

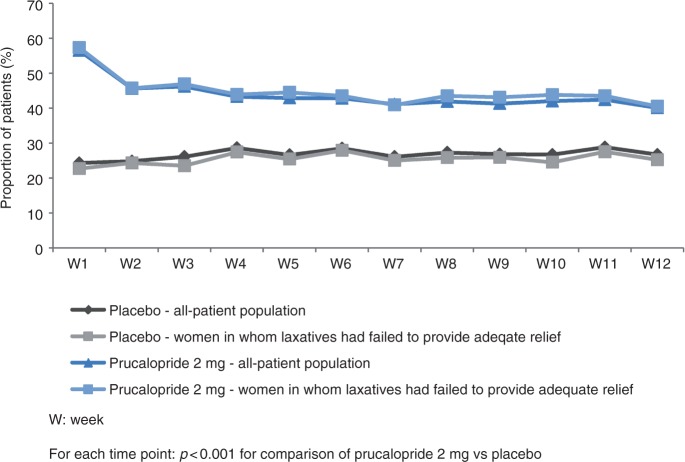

For each of the three endpoints, a significant difference between prucalopride and placebo was evident in the first week of treatment and was sustained every week thereafter, throughout the 12-week treatment period. This is displayed graphically and in tabular format in Figure 3 and Additional File 2 for an average of three or more spontaneous complete bowel movements per week, in Figure 4 and Additional File 3 for an average increase of one or more spontaneous complete bowel movements per week, and in Additional File 4 and Additional File 5 for an average increase of one or more spontaneous bowel movements per week.

Figure 3.

Proportion of patients with three or more spontaneous complete bowel movements during the course of the study.

Figure 4.

Proportion of patients with an increase of one or more spontaneous complete bowel movements compared with run-in.

Figure 5 shows the odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals of individual trials and pooled data at week 12 for an average of three or more spontaneous complete bowel movements per week and an average increase of one or more spontaneous complete bowel movements per week. No apparent differences were observed between trials and between the all-patient population and women in whom laxatives had failed to provide adequate relief. Numbers needed to treat were slightly lower in women in whom laxatives had failed to provide adequate relief than in the all-patient population.

Figure 5.

Forest plots of odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals at week 12.

Additional analyses revealed that 72.7% (136/187, all-patient) and 69.7% (99/142, women in whom laxatives had failed to provide adequate relief) of patients in the prucalopride group who achieved an average of three or more spontaneous complete bowel movements per week during weeks 1–4 of treatment also did so during weeks 1–12. The remaining 30% of patients still showed an average increase of one or more spontaneous complete bowel movements per week during weeks 1–12. Similarly, 92.0% (172/187, all-patient) and 89.4% (127/142, women in whom laxatives had failed to provide adequate relief) of patients in the prucalopride group with an average of three or more spontaneous complete bowel movements per week in weeks 1–4 also had an average increase of one or more spontaneous complete bowel movements per week during weeks 1–12 compared with baseline.

Other endpoints derived from patient diaries also significantly improved with prucalopride compared with placebo, with similar patterns of efficacy in weeks 1–4 and 1–12 (Table 2). In particular, patients receiving prucalopride reported improved stool consistency, less straining, and more bowel movements with a feeling of complete evacuation compared with patients receiving placebo. Prucalopride was also associated with a significant reduction in the number of bisacodyl tablets taken per week and in the median time to the first spontaneous (complete) bowel movement after the first intake of trial medication.

The impact of adherence to the recommended once-daily dose regimen of prucalopride was analysed for a group of 119 patients in the population of women in whom laxatives had failed to provide adequate relief, who had weeks with missed prucalopride doses on 2–5 days. For these patients, the mean average weekly number of bowel movements was 0.4–1.6 lower in weeks with missed doses (i.e. intake on 2–5 days/week) compared with weeks with daily intake (7 days/week) (p < 0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Impact of adherence to the recommended once-daily regimen of prucalopride

| n | Women in whom laxatives had failed to provide adequate relief (prucalopride 2 mg) | |

|---|---|---|

| Spontaneous complete bowel movements | 114 | 0.4 ± 0.18a |

| Spontaneous bowel movements | 113 | 1.3 ± 0.27b |

| Bowel movements (spontaneous/non-spontaneous) | 113 | 1.6 ± 0.27b |

Values are mean ± standard error.

The table summarizes the within-patient difference between the average number of (spontaneous) (complete) bowel movements in weeks with 7 days of prucalopride intake and the average number of (spontaneous) (complete) bowel movements in weeks with 2–5 missing treatment days. For example, the average weekly number of spontaneous complete bowel movements decreases by 0.4 if patients miss their prucalopride dose on 2–5 days per week.

ap < 0.05, bp < 0.0001 for comparison of adherence vs non-adherence.

Safety

The incidence of adverse events was 77.2% with prucalopride and 68.1% with placebo in the all-patient safety population (n = 1320), and 78.4% with prucalopride and 68.8% with placebo in women in whom laxatives had failed to provide adequate relief. In both populations, the most common (>10% of patients) adverse events were gastrointestinal events (abdominal pain, nausea, and diarrhoea) and headache. In women in whom laxatives had failed to provide adequate relief, the respective proportions of patients with such events were for prucalopride and placebo 20.1 and 10.9% for nausea, 12.7 and 10.9% for abdominal pain, 13.3 and 4.8% for diarrhoea, and 18.4 and 14.0% for headache. A higher proportion of patients in the prucalopride group (28.4%) than the placebo group (6.5%) had an adverse event on the first day of treatment. The majority of the excess adverse events on the first day were nausea, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, and headache. When adverse events on the first day of treatment were excluded, the respective proportions of patients with adverse events in the prucalopride and placebo groups were 10.7 and 9.8% for nausea, 8.1 and 10.0% for abdominal pain, 6.6 and 4.8% for diarrhoea, and 15.1 and 11.7% for headache. The same pattern was observed for the all-patient safety population.

Most adverse events were mild or moderate in severity (76.0–81.3% with prucalopride, 64.2–85.3% with placebo) and considered not related or unlikely to be related to study treatment by the investigator (57.4–62.4% with prucalopride, 59.8–72.9% with placebo). The incidence of serious adverse events was low (1–3%).

In the all-patient safety population, 13.1% of patients on prucalopride discontinued treatment prematurely with 6.2% discontinuing because of an adverse event. In the placebo group, 12.7% discontinued treatment prematurely (3.8% due to an adverse event). Results were very similar in the population of women in whom laxatives had failed to provide adequate relief (data not shown).

No clinically relevant changes were observed in vital signs, physical examinations, laboratory tests, or electrocardiogram parameters.

Discussion

The results of this integrated analysis of three identical, double-blind, placebo-controlled, pivotal phase III trials show that prucalopride 2 mg once daily for 12 weeks is an effective treatment for women with chronic constipation in whom laxatives have failed to provide adequate relief and that it has a favourable safety and tolerability profile. The efficacy and safety profile of prucalopride in this population was similar to that observed in the all-patient population of the three trials.

The women in whom laxatives had failed to provide adequate relief were severely affected by their constipation. They had, on average, a history of 20 years of constipation, and more than 80% reported an average of one or fewer spontaneous stools per week. At baseline, 60% of patients rated their constipation as severe/very severe.

When evaluating the most stringent endpoint, i.e. an average or three or more spontaneous complete bowel movements per week, prucalopride proved significantly more effective when compared with placebo. However, this does not imply that all other patients did not benefit from treatment with prucalopride. Analysis of the cumulative response for three endpoints demonstrated that 70% of patients, irrespective of the studied population (all-patient or women in whom laxatives had failed to provide adequate relief), experienced clinically relevant improvements in terms of increased frequency in spontaneous (complete) bowel movements.

In both populations, the increase in the number of spontaneous complete bowel movements with prucalopride was already evident in the first week of treatment and was sustained every week thereafter throughout the 12-week trial period. Given that the average number of spontaneous complete bowel movements per week was 0.4 during the run-in period, obtaining an average of three or more spontaneous complete bowel movements per week and/or an average increase of one or more spontaneous complete bowel movements per week represents an important improvement.

Early (weeks 1–4) response in terms of three or more spontaneous complete bowel movements per week predicted ultimate response over time (weeks 1–12). This indicates that physicians have the option to assess after 4 weeks whether prucalopride treatment should or should not be continued. For other diary derived endpoints, including stool characteristics, use of rescue laxatives and time to first bowel movement following the first dose, the pattern of efficacy of prucalopride was similar for weeks 1–4 and weeks 1–12 in both populations.

As prucalopride is not a laxative but a stimulator of motility, it may require daily rather than intermittent dosing. While most patients in this integrated analysis took prucalopride as planned without missing any daily intake (there were no patients with a clear pattern of non-adherence for a longer period), some had one or more weeks when they missed two or more doses. In these patients with two or more missed doses, the effect of prucalopride on bowel movement frequency was markedly less pronounced. This indicates that intermittent use of prucalopride is associated with decreased efficacy.

No new safety or tolerability concerns were identified. In both populations (all-patient and women in whom laxatives had failed to provide adequate relief), the most common adverse events were gastrointestinal problems and headache.

Conclusion

Prucalopride is effective in treating constipation in women in whom laxatives fail to provide adequate relief. The efficacy and safety profile of prucalopride 2 mg once daily for 12 weeks observed in this population was similar to that observed in the all-patient population of men and women with chronic constipation who had or had not obtained adequate relief from laxatives. In both populations, 70% of patients benefited from prucalopride treatment by achieving clinically relevant improvement on at least one important clinical efficacy endpoint. The effect of prucalopride on bowel movement frequency was significantly less pronounced if two or more doses per week were missed. It is, therefore, important to follow the dosing recommendation of one 2-mg tablet per day.

Acknowledgements

We thank Slavka Baronikova (Shire-Movetis) and Louisa Howard (Oxford PharmaGenesis) for editorial and project management assistance.

Funding

The study design and data collection were funded by Janssen Research Foundation, Beerse, Belgium. Analysis and interpretation of the data was funded by Shire-Movetis NV, Turnhout, Belgium. Anita van den Oetelaar provided medical writing support funded by Shire-Movetis NV, Turnhout, Belgium.

Conflict of interest

JT has acted as an advisor to Addex, Almirall, AstraZeneca, Danone, Ironwood, Menarini, Novartis, Sanofi-Aventis, Shire-Movetis, SK Life Sciences, Takeda, Theravance, Tranzyme Pharma, XenoPort and Zeria, and has undertaken speaking engagements for Abbott, Alfa Wasserman, Almirall, AstraZeneca, Janssen, Menarini, Novartis, Nycomed, Shire-Movetis, and Takeda.

EQ has acted as an advisor to Alimentary Health, Almirall, Ironwood, Norgine and Shire-Movetis, and has undertaken speaking engagements for Alfa Wasserman, Almirall, Danone, Janssen, Procter and Gamble, Ironwood and Shire-Movetis.

MC has acted as an advisor to Shire-Movetis and has undertaken speaking engagements for Shire-Movetis.

LV and RK are employees of Shire-Movetis and own stock in Shire.

RESOLOR is a CTM registered trademark of Shire-Movetis NV.

Presentation

Part of the results have previously been presented at the 2011 meeting of the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG), the United European Gastroenterology Week (UEGW) 2011, and the Digestive Disease Week (DDW) 2008, 2011 and 2012. In some of these presentations the performed analysis was the same as in the present publication but in a slightly different study population:

Camilleri M, Specht Gryp R, Kerstens R and Vandeplassche L. Efficacy of 12-week treatment with prucalopride [Resolor®] in patients with chronic constipation: combined results of three identical randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trials [abstract]. Gastroenterology 2008; 134(Suppl. 1): A-548.

Quigley EM, Tack JF, Vandeplassche L and Kerstens R. The efficacy and safety of oral prucalopride in female patients with chronic constipation who had failed laxative therapy (EMA-authorized population) is similar to that of the complete intent-to-treat population in the initial pivotal trials: pooled data analysis [abstract]. Gastroenterology 2012; 142(5): S-820–S-821.

Stanghellini V, Kerstens R and Vandeplassche L. Effect of treatment compliance on efficacy of prucalopride in patients with chronic constipation [abstract]. United European Gastroenterology Week (UEGW). October 22–26 2011. Stockholm, Sweden. Available at: http://www.mediaconcept.de/images/pdf/uegwposter1.pdf

Stanghellini V, Vandeplassche L and Kerstens R. Best response distribution of 12-week treatment with prucalopride (RESOLOR) in patients with chronic constipation: combined results of three randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trials [abstract]. Gut 2011; 60: A159–A160.

Tack JF, Ausma J, Kerstens R and Vandeplassche L. Safety and tolerability of prucalopride (Resolor®) in patients with chronic constipation: pooled data from three pivotal Phase III studies [abstract]. Gastroenterology 2008; 134(Suppl. 1): A-530–A-531.

Tack JF, Kerstens R and Vandeplassche L. Efficacy and safety of oral prucalopride in female patients with chronic constipation: pooled data of three pivotal trials [abstract]. Gastroenterology 2011; 140(Suppl. 1): S614–S615.

References

- 1. World Gastroenterology Organisation. World Gastroenterology Organisation practice guidelines: constipation. Available at: www.worldgastroenterology.org/assets/downloads/en/pdf/guidelines/05_constipation.pdf (2007)

- 2.Locke 3rd, GR, Pemberton JH, Phillips SF. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement: guidelines on constipation. Gastroenterology 2000; 119: 1761–1766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American College of Gastroenterology Chronic Constipation Task Force. An evidence-based approach to the management of chronic constipation in North America. Am J Gastroenterol 2005; 100(Suppl. 1): S1–S4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rome Foundation. Rome III diagnostic criteria for functional gastrointestinal disorders. Available at: www.romecriteria.org/assets/pdf/19_RomeIII_apA_885–898.pdf (2006) [PubMed]

- 5.Johanson JF. Review of the treatment options for chronic constipation. Med Gen Med 2007; 9: 25–25 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tack J, Müller-Lissner S. Treatment of chronic constipation: current pharmacologic approaches and future directions. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009; 7: 502–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson DA. Treating chronic constipation: How should we interpret the recommendations? Clin Drug Investig 2006; 26: 547–557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johanson JF, Kralstein J. Chronic constipation: a survey of the patient perspective. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007; 25: 599–608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Maeyer JH, Lefebvre RA, Schuurkes JA. 5-HT4 receptor agonists: similar but not the same. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2008; 20: 99–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Briejer MR, Prins NH, Schuurkes JA. Effects of the enterokinetic prucalopride (R093877) on colonic motility in fasted dogs. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2001; 13: 465–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Briejer MR, Bosmans JP, Van Daele P, et al. The in vitro pharmacological profile of prucalopride, a novel enterokinetic compound. Eur J Pharmacol 2001; 423: 71–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Schryver AM, Samsom M, Akkermans LM, et al. Fully automated analysis of colonic manometry recordings. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2002; 14: 697–703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. European Medicines Agency. Resolor® (prucalopride). Summary of product characteristics. Available at: www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/001012/WC500053998.pdf (2009)

- 14.Camilleri M, Kerstens R, Rykx A, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of prucalopride for severe chronic constipation. N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 2344–2354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quigley EM, Vandeplassche L, Kerstens R, et al. Clinical trial: the efficacy, impact on quality of life, and safety and tolerability of prucalopride in severe chronic constipation – a 12-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009; 29: 315–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tack J, Van Outryve M, Beyens G, et al. Prucalopride (Resolor) in the treatment of severe chronic constipation in patients dissatisfied with laxatives. Gut 2009; 58: 357–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin SR, Ke MY, Luo JY, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial assessing the efficacy and safety of tegaserod in patients from China with chronic constipation. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13: 732–739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]