Abstract

Background

The source and outcomes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) in oncologic patients are poorly investigated.

Objective

The study aimed to investigate these issues in a tertiary academic referral center specialized in cancer treatment.

Methods

This was a retrospective study including all patients with cancer referred to endoscopy due to UGIB in 2010.

Results

UGIB was confirmed in 147 (of 324 patients) referred to endoscopy for a suspected episode of GI bleeding. Tumor was the most common cause of bleeding (N = 35, 23.8%), followed by varices (N = 30, 19.7%), peptic ulcer (N = 29, 16.3%) and gastroduodenal erosions (N = 16, 10.9%). Among the 32 patients with cancer of the upper GI tract, the main causes of bleeding were cancer (N = 27, 84.4%) and peptic ulcer (N = 5, 6.3%). Forty-one patients (27.9%) presented with bleeding from the primary tumor or from a metastatic lesion, and seven received endoscopic therapy, with successful initial hemostasis in six (85.7%). Rebleeding and mortality rates were not different between endoscopically treated (N = 7) and non-treated (N = 34) patients (28.6% vs. 14.7%, p = 0.342; 43.9% vs. 44.1%, p = 0.677). Median survival was 20 days, and the overall 30-day mortality rate was 44.9%. There was no predictive factor of mortality or rebleeding.

Conclusion

Tumor bleeding is the most common cause of UGIB in cancer patients. UGIB in cancer patients correlates with a high mortality rate regardless of the bleeding source. Current endoscopic treatments may not be effective in preventing rebleeding or improving survival.

Keywords: Gastrointestinal hemorrhage, neoplasms, human, endoscopy, gastrointestinal

Introduction

Despite the vast amount of literature addressing the causes and management of upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) in the general population, there is a paucity of data regarding the etiology and natural course of UGIB in patients with cancer.

Some authors suggest that the causes of UGIB in cancer patients are similar to those in non-cancer patients,1–4 but the only article reporting these data was published in 1974 from Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC), which included 65 patients.1 In this report, the major cause of bleeding was found to be hemorrhagic gastritis (40%). Although 28% of patients had gastric cancer, the tumor was considered as the source of bleeding in only 15%. This is not consistent with our experience, as bleeding in patients with GI neoplasia is rarely from a source other than the tumor itself. It is also noteworthy that over the last three decades there have been significant developments in oncologic treatment, which have likely changed the natural course of oncologic patients who present with UGIB.

For the same reasons, the role of endoscopy in the diagnosis and treatment of UGIB in oncologic patients is unclear. There are few reports describing the efficacy of endoscopic treatment of bleeding tumors. On the other hand, it is uncertain if the results of endoscopic treatment for peptic ulcer or variceal bleeding differ in patients with cancer.

The main objective of this article is to study the causes of bleeding in an oncologic population and characterize outcomes after the bleeding episodes. We also aim to describe the role of endoscopy in the treatment of the bleeding lesions in these patients.

Methods

A retrospective review from a prospectively collected database was performed, including all patients referred to the endoscopy unit with suspected GI hemorrhage at a reference center for cancer treatment (Cancer Institute, University of São Paulo, Brazil), between January and December 2010. Data extraction was conducted under Institutional Ethical Committee–approved protocol.

Exams were performed with standard Olympus endoscopes (GIF H180) under conscious sedation. Bleeding was confirmed whenever there was active bleeding at endoscopy, undisputable signs of recent bleeding (adherent clots or visible vessel), or blood or coffee-ground stasis. When there were signs of bleeding but the true source could not be confirmed at endoscopy, we described it as an undefined source.

Endoscopic therapy was applied according to the bleeding lesion: elastic banding for esophageal varices, cyanoacrylate injection for gastric varices, combined treatment (injection and hemoclips or injection and thermal therapy) for peptic ulcers, hemoclips for Dieulafoy lesions and argon plasma coagulation (APC) for angioectasias. Because there is no formal indication to perform endoscopic treatment for tumor oozing, APC and thermocoagulation were performed at the discretion of the endoscopist in some patients, but not on a routine basis.

Data analysis was performed using SPSS software (version 19.0) (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Categorical variables were compared using the Fisher exact test. A statistical significance level of 5% was adopted.

Results

Patient demographics

Three hundred and twenty-four patients were referred to endoscopy with suspected upper GI bleeding during the study period. Bleeding was confirmed endoscopically in 147 (45.4%). Patients’ clinical presentation consisted of hematemesis (45.6%), melena (27.2%), falling hemoglobin (15.6%), hematochezia (4.1%), coffee-ground emesis (3.4%) and others (4.1%). One hundred and four patients had metastatic disease, 38 had locoregional advanced cancer, and in five, precise staging could not be determined. There were no patients with early cancer. Table 1 summarizes patients’ demographic data.

Table 1.

Demographic data of cancer patients with confirmed gastrointestinal bleeding

| Demographic data | N = 147 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 90 | 61.2% | ||

| Female | 57 | 38.8% | ||

| Cancer | ||||

| GI | 85 | 57.8% | ||

| Breast | 12 | 8.2% | ||

| Lung | 8 | 5.4% | ||

| Lymphoma | 9 | 6.1% | ||

| Head and neck | 6 | 4.1% | ||

| Leukemia | 5 | 3.4% | ||

| Prostate | 5 | 3.4% | ||

| Ovary | 4 | 2.7% | ||

| Kidney | 3 | 2.1% | ||

| Others | 10 | 6.8% | ||

| Clinical presentation | ||||

| Hematemesis | 67 | 45.6% | ||

| Melena | 40 | 27.2% | ||

| Enterorrhagia | 6 | 4.1% | ||

| Coffee-ground emesis | 5 | 3.4% | ||

| Falling hemoglobin | 23 | 15.6% | ||

| Unknown | 6 | 4.1% | ||

| Endoscopic treatment | ||||

| Elastic banding | 20 | 31.7% | ||

| Combined therapy (injection + clip or coagulation) | 10 | 15.9% | ||

| APC | 10 | 15.9% | ||

| Hemoclips | 7 | 11.1% | ||

| Adrenaline injection | 7 | 11.1% | ||

| Cyanoacrylate injection | 5 | 7.9% | ||

| Variceal sclerotherapy | 2 | 3.2% | ||

| Cyanoacrylate injection + elastic banding | 2 | 3.2% |

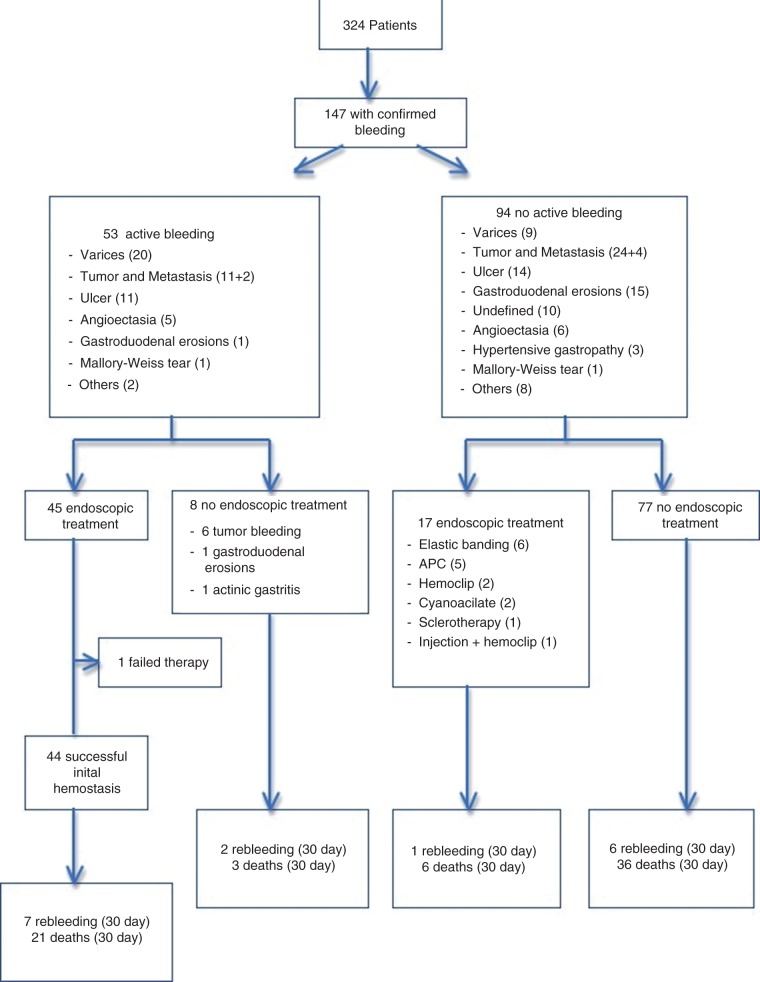

Endoscopic treatment was performed in 62 patients (42.1%; Figure 1). At the time of endoscopy, 53 patients (36.1%) had active bleeding, and in 45 the treatment was aimed at arresting the bleed. There was one case of therapeutic failure. This was a patient with a pancreatic tumor invading the duodenum treated with APC. In the remaining eight untreated patients, the tumor itself was the source of the bleeding in six and diffuse hemorrhagic gastritis was the etiology in two patients (including one with actinic gastritis); the endoscopist decided not to offer any kind of endoscopic treatment for these patients.

Figure 1.

Patient flow diagram. A total of 324 cancer patients were referred to endoscopy due to upper gastrointestinal bleeding. In 147 patients the bleeding was confirmed (53 active bleeding and 94 non-active bleeding).

There were four complications (1.2%) related to the endoscopic exam: three cases of bronchoaspiration and one case of respiratory depression necessitating ventilatory support. The three patients with bronchoaspiration died within two days of the procedure and the patient requiring ventilatory support died 19 days later. There were no perforations.

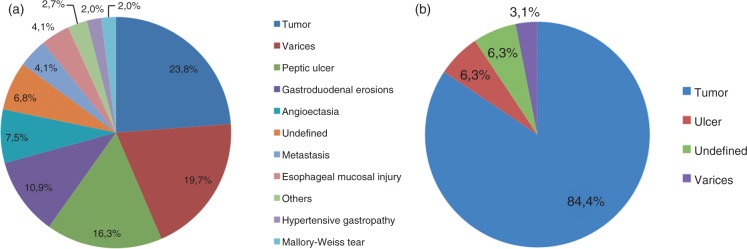

Tumor was the most common cause of bleeding (23.8%) followed by varices (19.7%), peptic ulcer (16.3%), gastroduodenal erosions (10.9%), angioectasia (7.5%), undefined (6.8%), metastasis (4.1%), esophageal mucosal injury (4.1%), others (3.4%), hypertensive gastropathy (2.0%) and Mallory-Weiss tear (1.4%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

(A) Most common causes of bleeding in patients with cancer (N = 147). (B) Most common causes of bleeding in patients with tumors of the upper gastrointestinal tract (oropharynx, esophagus and stomach).

Patients with tumors of the upper GI tract

Considering patients with luminal tumors of the upper GI tract (oropharynx = 3, hypopharynx = 2, esophagus = 10, stomach = 14, gastric stump = 3), the main causes of bleeding were tumor (84.4%), ulcer (6.3%), undefined (6.3%), and varices (3.1%) (Figure 2).

Among 147 patients with confirmed bleeding at endoscopy, 27 patients had esophageal or gastric cancer (10 esophageal and 17 gastric). Of these, the tumor was confirmed as the cause of bleeding in 25 (92.6%, 10 esophageal and 15 gastric cancer). In one patient the bleeding source could not be determined, and one patient had signs of bleeding from esophageal varices. Five patients received endoscopic therapy, including four APC and one variceal obliteration with cyanoacrylate injection. Median survival for these five treated patients was 28.5 days (range 26–51). Of the 27 patients with confirmed bleeding, three rebled within 30 days; at initial endoscopy, two of these patients received no therapy and one was treated with APC. One patient was lost to follow-up after 36 days. Overall mortality rate at 30 days was 44.4% (12 of 27).

Patients with tumors outside the gastrointestinal tract

Among patients with tumors located outside the GI tract (55 patients), the main causes of bleeding were ulcer (23.6%), gastroduodenal erosions (16.4%), varices (14.5%), angioectasia (12.7%), metastasis (10.9%), esophageal mucosal injury (9.1%), undefined (7.3%), and other causes (5.5%). The 30-day rebleeding rate was 10.9% (six patients) and the 30-day mortality rate was 50.9% (28 patients).

Bleeding from tumoral lesions

Forty-one patients (with any primary neoplasia) presented with bleeding from a tumor or metastatic lesion: 15 had gastric cancer, 10 had esophageal cancer, seven had duodenal invasion from a pancreatic or hepatobiliary cancer, six had distant metastases to the GI tract and three had oropharyngeal cancer.

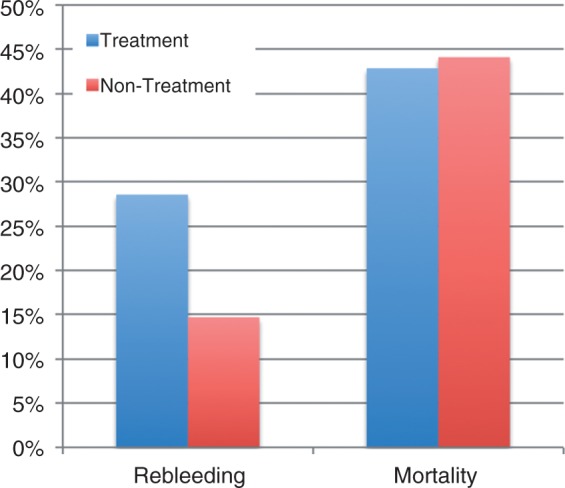

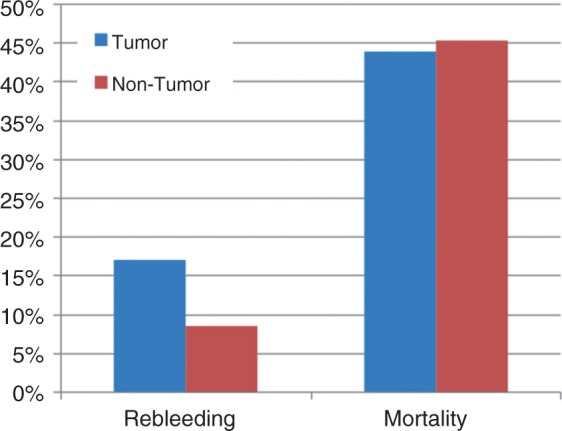

Active bleeding was identified in 13 of these patients (31.7%). Six received no therapy, at the endoscopist’s discretion (Figure 3). Thirty-day rebleeding rate for these six patients was 33.3% (two patients) and the 30-day mortality rate was 33.3% (two patients). Seven patients with active bleeding received endoscopic therapy (five APC, one hemoclips, one thermocoagulation + clips). Successful immediate hemostasis was achieved in six patients (85.7%). Two patients (28.5%) rebled and three (42.8%) died within 30 days. There was no difference in rebleeding or 30-day mortality rates comparing the seven patients who received endoscopic treatment with the six who did not (p = 0.636 and p = 0.571, respectively). Eleven patients with gastric tumor or duodenal invasion were referred to hemostatic radiotherapy and two patients were submitted to gastrectomy. Finally, among patients with tumoral bleeding (N = 41) there was no difference in the rebleeding rate (28.6% vs. 14.7%) and the 30-day mortality rate (42.9% vs. 44.1%) comparing the seven patients who received endoscopic treatment with the 34 who did not (p = 0.342 and p = 0.677, respectively; Figure 4).

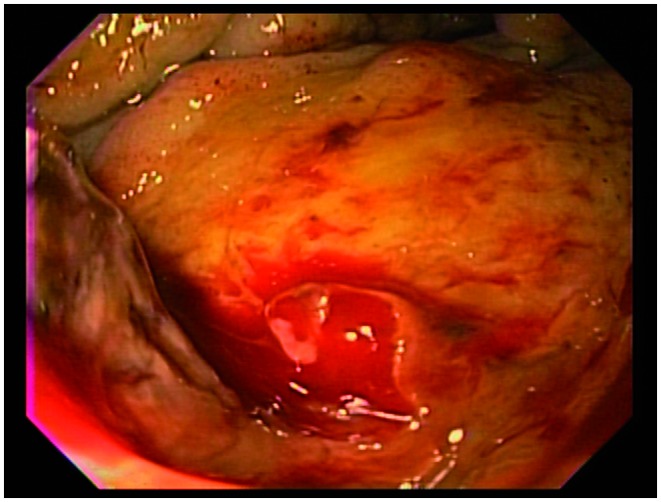

Figure 3.

Endoscopic view of an oozing bleed from a pancreatic adenocarcinoma invading the duodenal wall.

Figure 4.

Of the 41 patients with tumoral bleeding, seven received endoscopic treatment and 34 did not. There was no difference in 30-day rebleeding and mortality rates between these groups (p = 0.342 and p = 0.677, respectively).

The thirty-day rebleeding rate for this entire group (41 patients) was 17% (seven patients) and the 30-day mortality rate was 43.9% (18 patients). The 30-day rebleeding rate for patients with bleeding from non-tumoral sources was 8.5%; the 30-day mortality rate for these patients was 45.3% (Figure 5). We found no differences in the rebleeding rate (p = 0.116) or mortality rate (p = 0.63) comparing patients with tumor bleeding versus non-tumor bleeding.

Figure 5.

Comparing patients with bleeding from tumoral versus non-tumoral sources, there was no difference in 30-day rebleeding and mortality rates (p = 0.116 and p = 0.63, respectively).

Rebleeding

Seventeen patients (11.6%) presented with at least one episode of rebleeding within 30 days after the initial episode. Mean time to rebleeding was eight days (range 1–19, SD 6.2).

Comparing rebleeding rates by gender, etiology of bleeding (tumoral vs. non-tumoral), active versus non-active bleeding and concomitant use of chemotherapy, there was only a trend toward increase risk of rebleeding for patients who presented with active bleeding at endoscopy (p = 0.068).

Survival

Of the 147 patients who bled, 109 died within a mean follow-up period of 46 days. The mortality rate at 30 days and six months was 44.9% and 70.7%, respectively. Moreover, 36.7% of the patients died before leaving the hospital (mean hospital stay until death, eight days). The mean hospital stay for patients who survived was 11 days (SD 13.9) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Main outcomes after the bleeding episode

| Mortality | All patients | Tumor bleeding | Non-tumor bleeding |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30-day | 44.9% | 43.9% | 45.3% |

| 6 months | 70.7% | 80.4% | 66.9% |

| Mean | 46 days | 40 days | 49 days |

| Median | 20 days | 26 days | 19 days |

| SD | 62.4 days | 45.4 days | 68.5 days |

| Post-bleeding hospital stay | |||

| Mean | 11 days | 11 days | 11 days |

| Median | 7 days | 8 days | 7 days |

| SD | 13.9 days | 14.8 days | 13.5 days |

| Rebleeding (30-day) | |||

| Total | 17 (11.6%) | 7 (17%) | 9 (8.5%) |

| Time to rebleeding | |||

| Mean | 8 days | 8 days | 8 days |

| Median | 7 days | 7 days | 7 days |

| Range | 1–19 | 1–19 | 1–19 |

| SD | 6.2 | 7.2 | 5.9 |

To assess for factors related to increased risk of 30-day mortality, we compared mortality rates of patients categorized by groups. On univariate analysis there was no predictive factor of 30-day mortality. Gender (p = 0.488), primary tumor location (p = 0.246), clinical presentation (p = 0.423), Karnofsky status (p = 0.209), bleeding etiology (0.515), hemoglobin level (p = 0.069), active bleeding (p = 0.540) and chemotherapy (0.131) were not predictive of 30-day mortality (Table 3).

Table 3.

Predictive factors of 30-day mortality

| Survival | Death | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 49 (54.4%) | 41 (45.6%) | p = 0.488 |

| Female | 32 (56.1%) | 25 (43.9%) | ||

| Clinical presentation | Hematemesis | 38 (56.7%) | 29 (43.3%) | p = 0.423 |

| Others | 43 (53.8%) | 37 (46.2%) | ||

| Hemoglobin | <7 | 35 (63.6%) | 20 (36.4%) | p = 0.069 |

| >7 | 42 (49.4%) | 43 (50.6%) | ||

| Karnofsky status | 80–100 | 38 (64.4%) | 21 (35.6%) | p = 0.209 |

| 0–70 | 35 (55.6%) | 28 (44.4%) | ||

| Karnofsky status | 50–100 | 65 (61.9%) | 40 (38.1 %) | p = 0.186 |

| 0–40 | 8 (47.1%) | 9 (52.9%) | ||

| Etiology | Tumor and metastasis | 23 (56.1%) | 18 (43.9%) | p = 0.515 |

| Others | 58 (54.7%) | 48 (45.3%) | ||

| Actively bleeding | No | 52 (55.3%) | 42 (44.7%) | p = 0.540 |

| Yes | 29 (54.7%) | 24 (45.3%) | ||

| Chemotherapy | No | 38 (50.0%) | 38 (50.0%) | p = 0.131 |

| Yes | 43 (66.6%) | 28 (39.4%) | ||

| Rebleeding | No | 74 (56.5%) | 57 (43.5%) | p = 0.241 |

| Yes | 7 (43.8%) | 9 (56.2%) | ||

Comparing patients with tumoral bleeding who underwent endoscopic therapy versus those who received no therapy, we found no difference in 30-day survival rates (p = 0.677).

Discussion

According to our results, the causes of UGIB in oncologic patients are different from the general population.5 Tumor bleeding is the main etiology among cancer patients. This is especially true in patients with tumors of the GI tract, where the chance of a tumoral bleeding is as high as 84.4%. However, if we consider only patients with tumors outside the GI tract, the most common causes of UGIB are similar to the general population, that is, ulcer, gastroduodenal erosions and varices. On the other hand, even in patients with tumors outside the GI tract, metastases were the source of bleeding in a significant number of patients (11%).

Endoscopic treatment was offered to 19.4% of all patients referred to endoscopy and to 44.2% of patients in whom GI bleeding was confirmed. Immediate control of active bleeding was successful in 44 of 45 patients (97.7%). The 30-day rebleeding rate was 11.6%, although this figure may low, as many patients (44.9%) died within 30 days, before they had a chance to rebleed. Four patients (1.2%) developed complications related to the endoscopic procedure resulting in early mortality in three (0.9%); all were related to sedation, including three cases of aspiration. These data cannot be compared to the literature, since the only study addressing the causes of bleeding in cancer patients did not report outcomes after bleeding.1

After an initial hemostasis of 85.7%, we found a rebleeding rate of 17% and a 30-day mortality rate of 43.9%. In a retrospective study, Savides et al. reported 42 patients with upper GI tumor bleeding. Seven patients were treated with thermal probes or epinephrine injection or both, with successful hemostasis in all patients. Regardless of having been treated or not, patients with upper GI tumor bleeding had a 30-day rebleed rate of 33%, a 30-day mortality rate of 10%, and a one-year mortality rate of 89%.6 While we found no difference in the 30-day mortality rate of patients who received endoscopic therapy versus those who did not, Savides et al. reported significantly higher mortality among patients who received treatment (43% vs. 3%), which they attributed to more advanced disease in this group.

In another retrospective study of 21 patients with UGIB from tumors,7 endoscopic therapy was performed in 15 patients, with initial hemostasis in 67%. Recurrence of bleeding occurred in 80%. Median survival was 39 days and the four-month mortality rate was 93%. Thirty-day rebleeding and mortality rates were not reported. Two fatal complications related to the procedures occurred.

In our institution, many patients with esophageal and gastric cancers are referred to endoscopy due to UGIB. Our data suggest that, with the current methods of endoscopic hemostasis, the role of endoscopic examination is probably limited to determining the source of bleeding, which will prove to be the tumor itself in the vast majority of patients. In fact, endoscopic therapy was performed in only five of the 44 patients referred to endoscopy (11.4%), including four patients who received APC therapy. Endoscopic therapy of malignant lesions, either with APC, laser, heater probe or injection, is not a reliable or established treatment for tumor bleeding. So far, only small case series have been published, without control groups, and with rebleeding rates ranging from 17 to 80%.2,6–8 Comparing patients with tumoral bleeding who received treatment versus those who received no treatment, we found no advantages in terms of rebleeding (28.6% vs. 14.7%) or mortality rates (42.9% vs. 44.1%). Based on our results we propose a randomized controlled trial comparing endoscopic treatment with APC versus no endoscopic treatment for oozing bleeding from esophageal, gastric and duodenal tumors. The rationale for choosing APC is based on the fragility of neoplastic tissue where mechanical methods of hemostasis might not be effective. Our data also make clear the need for novel endoscopic methods of hemostasis for tumoral bleeding. Recently, HemosprayTM was introduced as a therapeutic option for UGIB.9 Chen et al. tested this method in five cases of cancer-related GI hemorrhage. Immediate hemostasis was obtained in all patients and rebleeding was observed in one.10

Another important finding of this study is that UGIB in cancer patients is a life-threatening event. Indeed, 36.7% of patients did not leave the hospital after the bleeding, and 44.9% died within 30 days. Mortality was high regardless of whether the bleeding originated from tumor or non-tumor sources. It is also noteworthy that this high mortality rate occurred despite very good initial results of endoscopic treatment. Some may argue that the high mortality rate reported here is caused by the fact that many of our patients had bleeding while in the hospital (inpatient bleeding). Cohen et al.11 reported a 4.6% mortality rate among patients admitted with bleeding versus 30.3% among hospitalized patients who developed UGIB (p < 0.0001), similar to results previously reported by others.12,13 Information in our database did not allow us to distinguish between inpatient versus outpatient onset of bleeding; this is a limitation of the study. However the mortality rates reported here are consistently higher than those previously reported for inpatient bleeding in the general population.

Our results probably reflect the severity of the underlying disease of patients with advanced-stage cancer. A prospective survey of home palliative care reported three deaths in 18 patients (16.6%) as a consequence of GI bleeding (source not specified) one to two days after the event.14 Thirty-day mortality was not described. In fact, even in non-cancer bleeding, most of the mortality is due to non-bleeding–related causes, such as multi-organ failure and cardiopulmonary conditions. Instead of focusing merely on successful hemostasis, management should be optimized to reduce the risk of these complications.15

It should be acknowledged that our population is composed of very ill patients. According to the Brazilian National Database, approximately 50% of gastric cancers are stage IV at the time of diagnosis.16 Although the Cancer Institute of São Paulo provides high-quality medical care,17 above the standard of the Brazil’s public facilities, the above-mentioned facts may have contributed to some differences in the percentage of cancer bleeding and mortality rates.

This study has some limitations. Although data were collected from a prospective database, it is a retrospective study. Data on the amount of transfusional therapy or the presence of concomitant diseases were not available. This is a single-center study and selection bias inherent to a tertiary referral academic center may have contributed to the results.

Conclusion

The etiology of UGIB in cancer patients is different from in the general population. Tumor bleeding is the most common bleeding source. UGIB in cancer patients is related to a high mortality rate despite good efficacy of initial endoscopic treatment; thus UGIB in this patient population must be seen as a life-threatening event. The role of endoscopy is limited in cancer patients with advanced disease: it aids in identification of the bleeding source, but in the majority of patients the bleeding is of tumor origin and endoscopic treatment may not be effective in improving outcomes. Prospective controlled studies are needed to determine whether endoscopy therapy should be applied to control tumor bleeding, and to develop better-adapted hemostatic techniques.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Alan Barkun for the critical review of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Lightdale CJ, Kurtz RC, Sherlock P, et al. Aggressive endoscopy in critically ill patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding and cancer. Gastrointest Endosc 1974; 20(4): 152–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heller SJ, Tokar JL, Nguyen MT, et al. Management of bleeding GI tumors. Gastrointest Endosc 2010; 72(4): 817–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Imbesi JJ, Kurtz RC. A multidisciplinary approach to gastrointestinal bleeding in cancer patients. J Support Oncol 2005; 3(2): 101–110 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yarris JP, Warden CR. Gastrointestinal bleeding in the cancer patient. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2009; 27(3): 363–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adler DG, Leighton JA, Davila RE, et al. ASGE guideline: The role of endoscopy in acute non-variceal upper-GI hemorrhage. Gastrointest Endosc 2004; 60(4): 497–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Savides TJ, Jensen DM, Cohen J, et al. Severe upper gastrointestinal tumor bleeding: endoscopic findings, treatment, and outcome. Endoscopy 1996; 28(2): 244–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loftus EV, Alexander GL, Ahlquist DA, et al. Endoscopic treatment of major bleeding from advanced gastroduodenal malignant lesions. Mayo Clin Proc 1994; 69(8): 736–740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suzuki H, Miho O, Watanabe Y, et al. Endoscopic laser therapy in the curative and palliative treatment of upper gastrointestinal cancer. World J Surg 1989; 13(2): 158–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sung JJ, Luo D, Wu JC, et al. Early clinical experience of the safety and effectiveness of Hemospray in achieving hemostasis in patients with acute peptic ulcer bleeding. Endoscopy 2011; 43(4): 291–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen YI, Barkun AN, Soulellis C, et al. Use of the endoscopically applied hemostatic powder TC-325 in cancer-related upper GI hemorrhage: preliminary experience (with video). Gastrointest Endosc 2012; 75(6): 1278–1281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen M, Sapoznikov B, Niv Y. Primary and secondary nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. J Clin Gastroenterol 2007; 41(9): 810–813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zimmerman J, Meroz Y, Arnon R, et al. Predictors of mortality in hospitalized patients with secondary upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. J Intern Med 1995; 237(3): 331–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muller T, Barkun AN, Martel M. Non-variceal upper GI bleeding in patients already hospitalized for another condition. Am J Gastroenterol 2009; 104(2): 330–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mercadante S, Fusco F, Valle A, et al. Factors involved in gastrointestinal bleeding in advanced cancer patients followed at home. Support Care Cancer 2004; 12(2): 95–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sung JJ, Tsoi KK, Ma TK, et al. Causes of mortality in patients with peptic ulcer bleeding: a prospective cohort study of 10,428 cases. Am J Gastroenterol 2010; 105(1): 84–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saúde Md. A situação do câncer no Brasil , Rio de Janeiro: Instituto Nacional de Câncer, Coordenação de Prevenção e Vigilância, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Health care in Brazil: an injection of reality. The Economist, 30 July 2011, http://www.economist.com/node/21524879 (accessed 28 December 2012)