Abstract

Background

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and biliary stenting fails in 5–10% patients of malignant biliary obstruction because papilla is inaccessible. Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) is an accepted alternative. Endosonography-guided biliary drainage (EUS-BD) has been described recently.

Aim

To compare success rates and complications of EUS-BD and PTBD internal stenting.

Methods

This retrospective study included failed ERCP in inoperable malignant biliary obstruction due to inaccessible papilla undergoing PTBD or EUS-BD. Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography guided/EUS-guided rendezvous procedures were excluded. When PTBD internal stenting failed, external drainage was performed. EUS-BD was performed using either intra- or extrahepatic approach, and stents were placed by transmural (choledocho-duodenostomy or hepatico-gastrostomy) or antegrade approach. Self-expandable metallic stents or plastic stents were placed in both groups. Success of internal stenting and complications were compared using t-test and chi-squared test.

Results

Retrospective review of 6 years of records (2005–2011) revealed 50 patients meeting the required criteria. EUS-BD was attempted in 25 and PTBD in 26 patients (one crossover from EUS-BD to PTBD). Internal stenting was technically and clinically successful in 23/25 (92%) EUS-BD vs. 12/26 (46%) PTBD (p < 0.05). External catheter drainage was performed in remaining 14 PTBD patients. Complications occurred in 5/25 (20%) EUS-BD (one major, four minor) and in 12/26 (46%) PTBD (four major, eight minor; p < 0.05). Late stent occlusion occurred in one EUS-BD and three PTBD.

Conclusions

In this retrospective study comparing success and complications of EUS-BD and PTBD in patients with inoperable malignant biliary obstruction and inaccessible papilla, EUS-BD was found superior to PTBD for both comparators.

Keywords: EUS, biliary drainage, biliary stenting, choledocho-duodenostomy, hepatico-gastrostomy, interventional EUS, PTBD, therapeutic endosonography

Introduction

ERCP fails in up to 5–10% patients due to failed papillary cannulation or because the duodenoscope cannot be advanced to the papilla due to obstruction or altered anatomy.1 In these patients, percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) or surgical bypass may be utilized for biliary decompression, but these are associated with higher patient discomfort and prolonged hospital stay.2 Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage (EUS-BD) has been introduced as an alternative for patients with failed ERCP. Giovannini et al.3 described the first EUS-guided biliary drainage in 2001. Since then, many reports have been published focusing on indications, technique modifications, and efficacy. EUS-BD may be performed as a rendezvous procedure in combination with ERCP4 or stents may be directly placed using the echoendoscope.5–9 Although the technique has shown promising results in large multicentre studies,10 it must be compared to established modalities like PTBD or surgery. Only one such randomized controlled study has been published to date, and this has limitations of small sample size.11

One of the commonest causes for failed ERCP (and therefore for alternative PTBD or EUS-BD) is when the papilla is inaccessible to the duodenoscope either due to tumour infiltration, gastric outlet obstruction, an indwelling duodenal stent, or previous gastric bypass surgery. Such situations are commonly encountered when the malignant process concomitantly obstructs the biliary tree and the gastric outlet. This study addresses results of EUS-BD in such situations and compares its efficacy and complication rates to those of PTBD.

Patients and methods

This was a retrospective single-centre comparative study. Amongst patients with inoperable cancer causing malignant biliary obstruction, those with failed ERCP due to an inaccessible papilla and undergoing palliative PTBD or EUS-guided stenting were included. Those with accessible papilla but failed ERCP undergoing rendezvous procedure (PTBD or EUS-guided) were excluded. EUS-BD procedures were performed by a single endoscopist with adequate experience in performing EUS-guided therapeutic interventions. EUS-BD was performed by either the transmural via intrahepatic (hepatico-gastrostomy, EUS-HG) or extrahepatic (choledocho-duodenostomy, EUS-CD) route or by the antegrade transpapillary approach (EUS-AG). Two independent experienced interventional radiologists performed PTBD. Informed consent was obtained from all patients or their next-of-kin prior to the procedure and the institutional ethics committee approved the study.

EUS-BD

EUS-BD procedures were performed using a therapeutic 3.8-mm channel curved linear echo-endoscope (Fujinon UG-530XT) and SU-7000 EUS processor. The duodenal route (EUS-CD) was preferred whenever duodenal bulb was accessible. Alternatively, the gastric intrahepatic approach was used (EUS-HG or EUS-AG).12

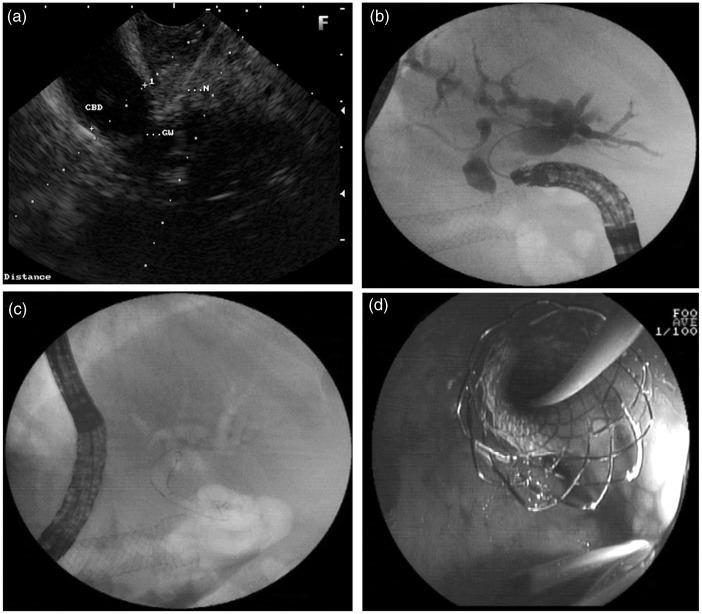

EUS choledocho-duodenostomy

For EUS-CD, the extrahepatic common bile duct (CBD) was located from the duodenal bulb and the endoscope was oriented to direct the puncture towards the liver hilum. The CBD was punctured using a prefilled 19G FNA needle (Echotip Ultra 19, Cook Endoscopy, Winston Salem, USA). Aspiration of bile confirmed the intraductal position (Figure 1a). A cholangiogram was obtained by injecting contrast. A 0.035-inch 450-cm hydrophilic guidewire (Tracer Metro; Cook Endoscopy, Winston Salem, USA; or Visiglide; Olympus Corporation, Japan) was negotiated through the needle into the intrahepatic bile duct. The tract was dilated over the wire (Figure 1b) using a tapered biliary dilation catheter (7Fr Soehendra biliary dilation catheter; Cook Endoscopy), 6Fr Cystotome (Endoflex, Germany), needle knife (Microknife; Boston Scientific Microvasive, Boston, Massachusetts, USA), or 4-mm biliary dilatation balloon (Hurricane; Boston Scientific Microvasive, Boston, Massachusetts, USA) or a combination of instruments. Transmural deployment of covered self-expandable metallic stents (SEMS) (Wallstent; Boston Scientific Microvasive; or Niti-S, Taewoong Medical, South Korea) or 10Fr plastic stents (Cook Endoscopy) was performed over the wire. The entire procedure was monitored by X-ray fluoroscopy. (Figure 1c, d)

Figure 1.

EUS choledocho-duodenostomy. (a) EUS-guided puncture of the dilated common bile duct from the duodenal bulb. (b) cholangiogram showing dilated biliary tree and duodenal stent in situ, (c, d) Fluoroscopy, showing EUS-CD with deployed self-expandable metallic stents (c) and endoscopic view (d).

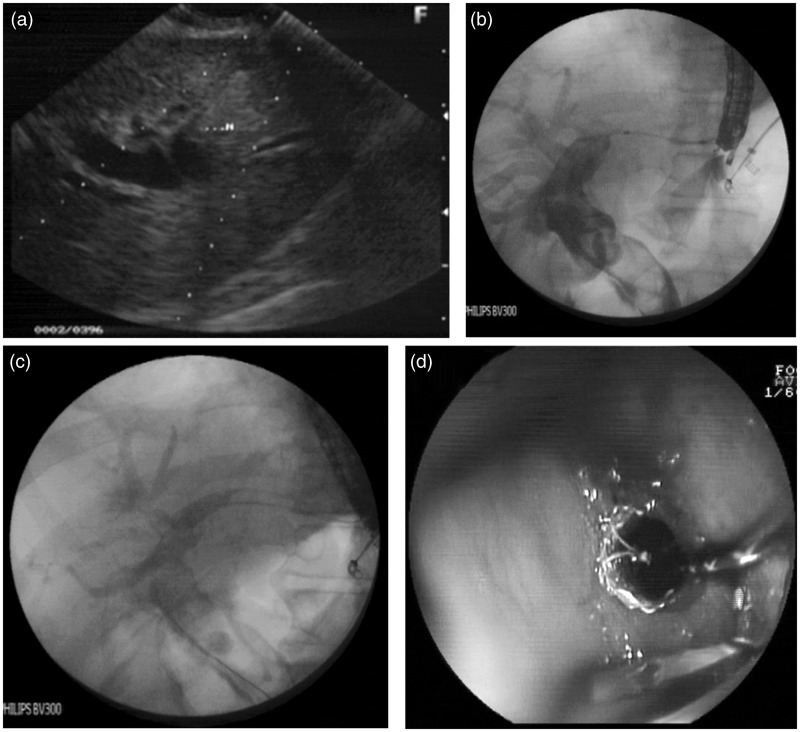

EUS hepatico-gastrostomy

For EUS-HG, the dilated left intrahepatic biliary radicle was visualized by positioning the transducer in a short loop position facing the lesser curve. A dilated intrahepatic left duct radicle closest to the transducer was punctured using a 19G needle. Further intervention was similar to that described above for EUS-CD (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

EUS hepatico-gastrostomy. (a) EUS-guided puncture of dilated intrahepatic biliary radicle. (b) Cholangiogram showing dilated common bile duct and intrahepatic biliary radicle. (c, d) Fluoroscopy, showing EUS-HG with deployed self-expandable metallic stents (c) and endoscopic view (d).

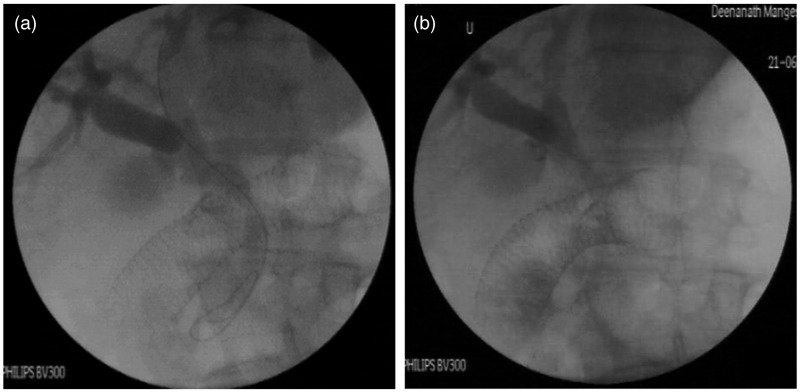

EUS antegrade transpapillary approach

For EUS-AG, after puncture of the intrahepatic biliary radicle, a 0.032-inch 260-cm hydrophilic glide wire (Terumo Corporation, Japan) was negotiated through the bile duct and across the papilla into the duodenum in an antegrade manner. Track dilatation was performed using a 6Fr-tapered dilator and the glide wire was exchanged for a stiffer 0.035-inch guide wire (Tracer Metro or Visiglide) through the dilator. An uncovered SEMS (Zilver 635; Cook Endoscopy) was placed across the stricture (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

EUS antegrade transpapillary approach. (a) EUS-guided cholangiogram with guide-wire crossing the ampulla. (b) Antegrade biliary self-expandable metallic stents across the papilla. Duodenal stent seen in situ.

Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage

For PTBD, percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography was performed using the standard technique from the right mid-axillary (right hepatic duct) or sub-xiphoid approach (left hepatic duct) using a 23G Chiba needle. A 21G needle was advanced into the liver under fluoroscopy guidance; a guidewire was advanced under fluoroscopy guidance into the CBD and further into the duodenum across the stricture. SEMS or plastic stents were deployed across the stricture after optimum track dilatation. External drainage catheters were placed when the stricture could not be negotiated, when repeat procedures were contemplated, or when drainage was suspected to be suboptimal.

Follow up

All patients were hospitalized 24–48 hours post procedure to monitor development of early complications. Clinical efficacy and development of late complications were evaluated at 1 week and at 1 month post procedure. Further evaluations were performed when clinically indicated.

Statistical analysis

Categorical data was compared using simple t-test while continuous data was compared using chi-square test. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

On retrospective analysis of our database from April 2005 to March 2012, there were 1752 patients subjected to ERCP for inoperable malignant biliary obstruction. Of these, in 50 patients, ERCP had failed because the papilla was inaccessible to the duodenoscope. These patients had been subjected to PTBD or EUS-BD and formed the study group. Records of these patients were analysed and compared, primarily for efficacy of placement of an internal biliary stent and secondarily for complications.

There were 30 men and 20 women in the study group. There was no significant difference between baseline parameters of patients in the two groups (p > 0.05; Table 1). The commonest aetiology of biliary obstruction was pancreatic head cancer in both groups, followed by ampullary carcinoma, gastric cancer, and hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Duodenal obstruction was the commonest cause of ERCP failure. Most patients in the EUS group had an indwelling duodenal stent whereas those in the PTBD group were scheduled for duodenal stenting or bypass following biliary decompression as per our policy to ensure optimum biliary decompression prior to gastric drainage.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients

| Characteristic | EUS-BD (n = 25) | PTBD (n = 26) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| Mean ± SD | 59.9 ± 13.3 | 62.4 ± 10.2 |

| Range | 43–87 | 44–75 |

| Sex (male/female) | 13/12 | 16/10 |

| Bilirubin (mg %) | ||

| Mean ± SD | 7.11 ± 7.6 | 9.41 ± 12.4 |

| Range | 2.7–28 | 1.8–33 |

| Aetiology of duodenal obstruction | ||

| CA head of pancreas | 15 | 18 |

| Ampullary CA | 5 | 3 |

| Hilar cholangio-CA | 2 | 2 |

| Reason for failed ERCP | ||

| Failed duodenal intubation | 21 | 21 |

| Indwelling duodenal stent for malignant duodenal obstruction | 14 | 2 |

| Duodenal obstruction (tumour infiltration) | 7 | 19 |

| Previous surgery (Billroth II gastrectomy, Whipple’s, GJ for peptic ulcer) | 4 | 5 |

| CA stomach | 3 | 3 |

Values are n unless otherwise stated. There were no significant differences between the groups.

CA, carcinoma; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; EUS-BD, endosonography-guided biliary drainage; GJ, gastrojejunostomy; PTBD, percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage.

EUS-BD was attempted in 25 (49%) and PTBD in 26 (51%) patients. One patient crossed over from EUS-BD to PTBD. The results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Results of internal stenting

| Parameter | EUS-BD | N (%) | PTBD | N (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Successful internal stent placement | 23/25 (92) | 12/26 (46) | <0.05 | ||

| Approach | Extrahepatic | 13 (52) | Segment VI | 18 | NS |

| Intrahepatic | 12 (48) | Segment III | 8 | NS | |

| Route | Transmural | 18 (78) | Transmural | 0 | NS |

| Trans-papillary | 5 (22) | Trans-papillary | 12 (100) | NS | |

| Procedure | EUS-CD | 13 (57) | PTBD | 12 (46) | NS |

| EUS-HG | 5 (21.5) | External drain | 14 (54) | NS | |

| EUS-AG | 5 (21.5) | – | – | – | |

| Type of stent | SEMS | 20 (87) | SEMS | 8 (67) | NS |

| Plastic 10Fr | 3 (13) | Plastic 10Fr | 4 (33) | NS | |

| Sessions until internal stenting | |||||

| Single | 23/25 (92) | 7/26 (27) | <0.05 | ||

| Multiple (mean 2.6, range 2–4) | 0 | 5/26 (19) | |||

| Failure of internal stenting | 2/25 (8) | 14/26 (54) | <0.05 | ||

Values are n, n/total, or n/total (%).

AG, antegrade transpapillary approach; BD, biliary drainage; CD, choledocho-duodenostomy; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; EUS, endosonography; HG, hepatico-gastrostomy; NS, not significant; PTBD, percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage.

EUS-BD

A total of 23/25 (92%) patients underwent successful placement of internal stents. The extrahepatic approach was used in 13 (57%) and intrahepatic in 10/23 (43%) patients. Transmural stents were placed in 18 (78%) and antegrade across papilla in five (22%) patients. SEMS were placed in 20 (87%) and 10Fr plastic stents in three (13%) patients. All plastic stents were placed by EUS-CD. All patients had a one-stage procedure. There were two failures, both using the intrahepatic approach: in one patient, intrahepatic biliary radicle dilatation was inadequate and puncture was unsuccessful, and the patient was crossed over to PTBD where puncture and subsequent stent placement was successful using the two-stage procedure; in the other patient, the intrahepatic bile duct was punctured and during dilatation, the guidewire slipped out and access was lost; the intrahepatic biliary radicle had by then collapsed and repeat puncture failed; PTBD was also attempted but failed.

PTBD

In the PTBD group, internal stents were placed in 12/26 (46%) patients. In the remaining 14 (54%) patients, either the guide wire could not be negotiated across the stricture or the stricture could not be effectively dilated despite guide wire negotiation. Internal stents therefore could not be placed. Patients were maintained on long-term external biliary drainage. Amongst those who received stents, SEMS were placed in eight (67%) and plastic stents in four (33%) patients. Seven (58%) patients underwent successful one-stage procedure, whereas five (42%) patients required multistage procedures (mean 2.6 sessions, range 2–4). Therefore, internal biliary drainage was more successful by EUS-BD as compared to PTBD (92 vs. 46%; p < 0.05).

Complications

Complications in both groups are summarized in Table 3. In the EUS-BD group, one patient (in whom guide wire access was lost during dilatation and re-puncture failed) developed biliary peritonitis. Despite intensive management and abdominal drainage, this patient succumbed to severe sepsis. Four other patients had minor, self-limiting, peri-stent leak of contrast. Patients were managed conservatively with intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotics for 72 hours and discharged without sequelae. In PTBD group, two patients developed fever in the post-procedure period due to cholangitis. Both recovered with intravenous antibiotics. Two other patients with pre-existing mild ascites developed biliary peritonitis after PTBD. Despite abdominal paracentesis, administration of intravenous antibiotics, and intensive management, both died due to multi-organ failure. One patient with mildly deranged coagulation profile (INR 1.6) developed significant bleeding from the puncture site to warrant blood transfusion. Bleeding eventually stopped after pressure dressing and no further intervention was necessary. In seven patients with long-term external catheter drainage, peri-catheter bile leak developed after few days. Skin excoriation was the most distressing symptom and management remained suboptimal with skin care creams and lotions. There was one death in EUS-BD group and two in PTBD group. To summarize, 5/25 (20%) patients in EUS-BD and 12/26 (46%) in PTBD group developed complications. This was statistically significant in favour of EUS-BD (p < 0.05).

Table 3.

Complications

| Complication | EUS-BD | PTBD |

|---|---|---|

| Major | 1/25 | 4/26 |

| Biliary sepsis, peritonitis, death | 1 | – |

| Cholangitis | – | 2 |

| Infected ascites, death | – | 2 |

| Minor | 4/25 | 8/26 |

| Self-limiting peri-stent leak | 4 | – |

| Peri-catheter cutaneous leak | – | 7 |

| Minor self limiting bleed | – | 1 |

| Total | 5/25 (20) | 12/26 (46) |

| Procedure-related mortality | 1/25 (4) | 2/26 (7.7) |

Values are n, n/total, or n/total (%). There were no significant differences between the groups.

EUS-BD, endosonography-guided biliary drainage; PTBD, percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage.

Follow up

All patients were followed for 1 month post procedure or until death (one patient in EUS-BD group having procedure-related mortality). Liver function tests on day 7 post procedure showed improvement, indicating stent patency. Four patients had delayed stent occlusion during the late follow up: three from the PTBD group, who underwent repeat stenting, and one from the EUS-AG group, in whom ERCP was performed through the duodenal stent and 10Fr plastic stents was placed through the previous SEMS after balloon dilatation.

Discussion

ERCP and biliary stenting is the treatment of choice for patients with inoperable malignant biliary obstruction.13–15 ERCP may fail in 5–10% patients1 because the duodenoscope cannot be advanced to the ampulla due to tumour obstruction or because of a previously placed duodenal stent or surgical gastro-enteric bypass. PTBD has been the accepted alternative in such situations,16 but it is associated with significant morbidity and patient discomfort and may result in long-term external catheter drainage.16,17

EUS-BD has been a technique in evolution for last 10 years. Current evidence shows that the technique is feasible and has an acceptable safety profile.18 EUS-BD may therefore be an alternative to PTBD when ERCP fails.19 Four variants of EUS-BD have been described – placement of transmural (EUS-CD, EUS-HG, or choledocho-antrostomy), or transpapillary stents (EUS-AG or EUS-ERCP rendezvous).11

In EUS-CD, EUS-HG, and EUS-AG, the entire procedure including stent placement is performed using the echoendoscope. It does not necessitate intubation of the descending duodenum and therefore can be utilized in situations when the papilla is inaccessible.

In EUS-ERCP rendezvous, the initial procedure is performed using the echoendoscope. Once the guide wire is negotiated out of the papilla into the duodenum, duodenoscope is advanced to the descending duodenum to retrieve the guide wire and complete ERCP and stent placement. EUS-ERCP rendezvous therefore, is similar to the PTBD-ERCP rendezvous because it is a modified (assisted) ERCP that is useful when papillary cannulation is difficult or impossible,20 but is futile in situations when the papilla cannot be reached.

In our study, we excluded patients with distorted papillary or duodenal anatomy where standard ERCP had failed and PTBD or EUS rendezvous with ERCP was performed. Our study only includes patients undergoing EUS-BD or PTBD because ERCP had failed due to inability to advance the duodenoscope to the papilla or descending duodenum. In our opinion, this group needs to be addressed separately since therapeutic options in these patients are limited and although PTBD and surgical drainage have been traditional treatment options, they have significant morbidity.

The following parameters were compared in our study – technical success of internal stent placement, number of sessions required to complete therapy, clinical success as indicated by improvement in symptoms and liver function tests, and incidence of complications.

Technical success of EUS-BD in our series was 23/25 (92%) for internal stent placement, which is comparable to the current overall success rates for this procedure.10,18,21–23 In all 23 patients, procedure was completed in a single session.

In comparison, in the PTBD group, only 12/26 (46%) patients received an internal stent across the stricture. In seven patients, the procedure was completed in a single session, whereas the remaining five needed multiple sessions (mean 2.6 sessions). Internal stenting was therefore found to be more successful in the EUS-BD group (92 vs. 46%, p < 0.05). Also, single-session therapy was possible in the EUS-BD group as compared to PTBD (92% vs. 27%, p < 0.05). The remaining 14 patients (54%) were maintained on long-term external catheter drainage. This was either due to inability to negotiate a guide wire across the stricture or else due to inability to dilate the stricture even after the guide wire had gone across. Most studies on PTBD report success rates of around 90%.16,17,24 The reasons for our inferior results may be attributed to multiple factors.

Patients in our series had concomitant malignant biliary and duodenal obstruction with advanced stage of disease. The malignancy involved the biliary tree and the bowel. Strictures in such situations may often be long, tortuous, very tight, and difficult for guide wire negotiation and subsequent dilatation. All 14 PTBD external drainages in our series had such strictures. Of the 12 successful stent placements, multistage procedures were required in five (42%) patients, indicating that strictures were tight and resistant to dilatation.

It is possible that experience in PTBD at our centre is limited, presumably due to lack of adequate opportunity (only 50/1752 ERCP failures in this study, 2.9% over 7-year period). One could therefore hypothesize that in centres where EUS expertise supersedes that of PTBD, EUS-BD could be the preferred method of drainage. The validity of such a hypothesis must be further critically evaluated in randomized trials.

When EUS-CD or EUS-HG is performed, it is not obligatory to cross or dilate the stricture prior to stent placement. The stent is placed from the duodenum or stomach into the dilated duct proximal to the stricture. A major and technically demanding step of guide wire manipulation across the stricture is therefore avoided.21 Guide wire manipulation is necessary in patients undergoing EUS-AG; but the procedure can easily be converted to EUS-CD or EUS-HG if this manipulation is unsuccessful.

A recent prospective randomized study between EUS-CD and PTBD has shown that results of both techniques are comparable.11 However, there are several limitations to this study. It is unclear from the patient details as to how many patients had duodenal obstruction leading to failure of ERCP, since patients with a patent duodenal lumen but distorted papilla may be subjected to rendezvous rather than EUS-BD or PTBD. It is also unclear as to in how many patients EUS-BD commenced with intention of rendezvous but was later converted to EUS-BD because the guidewire could not cross the stricture. Also, the reasons for not performing rendezvous are not mentioned despite the fact that the guidewire was negotiated into the duodenum in the PTBD group. Further, the study does not mention the number of sessions of PTBD – a significant cause of morbidity and prolonged hospital stay in these patients.

Lastly, the study only includes EUS-CD. Often in proximal biliary obstruction, the retro-duodenal CBD is non-dilated and EUS-CD is not feasible – this situation is not addressed.

In the current study, we had two technical failures in the EUS-BD group, both in the intrahepatic approach. Although one patient crossed over to PTBD and stent placement was successful, the other patient developed complications. In this patient, intrahepatic bile duct was punctured and the guide wire was positioned within. Track dilatation was performed using 6Fr cystotome and diathermy current. During this manoeuvre, the guide wire slipped out of the duct. Repeat puncture was attempted but failed as the biliary system had by then collapsed, possibly due to biliary leak from the liver surface. Subsequent PTBD was attempted but also failed. Patient developed biliary peritonitis and succumbed to sepsis and multi-organ failure. It is possible that the bile leak occurred due to diathermy injury to the liver capsule due to cystotome use, and use of a tapered catheter may have prevented this complication. Other complications in the EUS-BD group were minor and self-limiting: four peri-stent leaks.

In the PTBD group, there were two procedure-related deaths due to biliary peritonitis and multi-organ failure in patients with pre-existing ascites. Two other developed cholangitis but both recovered with intravenous antibiotics. Significant bleeding to warrant blood transfusion occurred in one patient, possibly related to the deranged coagulation profile.

During follow up, 7/14 patients with long-term external drainage developed peri-catheter bile-leak leading to skin excoriation. If skin excoriation is included, 5/25 (20%) patients in the EUS-BD group and 12/26 (46%) in the PTBD group developed complications. Complications, therefore, were less frequently seen in the EUS-BD group (p < 0.05).

Limitations

The poor result of PTBD is a significant limitation of our study, possibly influenced by the limited experience in PTBD at our institute. Secondly, being a retrospective study, there could be a potential bias in patient selection. Further randomized studies with strict patient selection criteria to define target population are recommended to address these limitations.

Conclusions

This study illustrates safety and efficacy of EUS-BD for biliary drainage when the papilla cannot be reached by the duodenoscope. EUS-BD can offer a single-session treatment as against PTBD where multiple sessions may be necessary to achieve internal drainage. Although in the current study the results of EUS-BD were significantly superior to those of PTBD, the study is non-randomized and has the limitation of poor PTBD success rates. The study therefore does not prove that EUS-BD is superior to PTBD. However, this study indicates that in centres where PTBD expertise is limited, the EUS-guided approach may offer more favourable clinical outcomes.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Enochsson L, Swahn F, Arnelo U, et al. Nationwide, population-based data from 11,074 ERCP procedures from the Swedish Registry for Gallstone Surgery and ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc 2010; 72: 1175–1184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Born P, Rosch T, Triptrap A, et al. Long-term results of percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage for benign and malignant bile duct strictures. Scand J Gastroenterol 1998; 33: 544–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giovannini M, Moutardier V, Pesenti C, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided bilioduodenal anastomosis: a new technique for biliary drainage. Endoscopy 2001; 33: 898–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mallery S, Matlock J, Freeman ML. EUS-guided rendezvous drainage of obstructed biliary and pancreatic ducts: report of 6 cases. Gastrointest Endosc 2004; 59: 100–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kahaleh M, Wang P, Shami VM, et al. EUS-guided transhepatic cholangiography: report of 6 cases. Gastrointest Endosc 2005; 61: 307–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Puspok A, Lomoschitz F, Dejaco C, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound guided therapy of benign and malignant biliary obstruction: a case series. Am J Gastroenterol 2005; 100: 1743–1747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kahaleh M, Yoshida C, Kane L, et al. Interventional EUS cholangiography: a report of five cases. Gastrointest Endosc 2004; 60: 138–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shah JN, Marson F, Weilert F, et al. Single-operator, single-session EUS-guided anterograde cholangiopancreatography in failed ERCP or inaccessible papilla. Gastrointest Endosc 2012; 75: 56–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weilert F, Binmoeller KF, Marson F, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided anterograde treatment of biliary stones following gastric bypass. Endoscopy 2011; 43: 1105–1108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gupta K, Perez-Miranda M, Kahaleh M. ESCP (Endo-songraphic cholangio pancreatography): technique, success and complications of a novel technique to access and drain the bile duct: a 10-year multi-center experience. Endoscopy 2011; 43: A13–A13 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Artifon EL, Aparicio D, Paione JB, et al. Biliary drainage in patients with unresectable, malignant obstruction where ERCP fails: endoscopic ultrasonography-guided choledochoduodenostomy versus percutaneous drainage. J Clin Gastroenterol 2012; 46: 768–774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bapaye A, Aher A. EUS guided biliary and pancreatic duct interventions. In: Akahoshi K, Bapaye A. (eds). Practical handbook of endoscopic ultrasonography, 1st edn Japan: Springer, 2012, pp. 277–285 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith AC, Dowsett JF, Russell RC, et al. Randomised trial of endoscopic stenting versus surgical bypass in malignant low bileduct obstruction. Lancet 1994; 344: 1655–1660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.ASGE guidelines for clinical application. The role of ERCP in diseases of the biliary tract and pancreas. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 1999; 50: 915–920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. NIH state-of-the-science statement on endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) for diagnosis and therapy. NIH Consens State Sci Statements 2002; 19: 1–26. [PubMed]

- 16.Lameris JS, Stoker J, Nijs HG, et al. Malignant biliary obstruction: percutaneous use of self-expandable stents. Radiology 1991; 179: 703–707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pinol V, Castells A, Bordas JM, et al. Percutaneous self-expanding metal stents versus endoscopic polyethylene endoprostheses for treating malignant biliary obstruction: randomized clinical trial. Radiology 2002; 225: 27–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park do H, Jang JW, Lee SS, et al. EUS-guided biliary drainage with transluminal stenting after failed ERCP: predictors of adverse events and long-term results. Gastrointest Endosc 2011; 74: 1276–1284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gupta K, Mallery S, Hunter D, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound and percutaneous access for endoscopic biliary and pancreatic drainage after initially failed ERCP. Rev Gastroenterol Disord 2007; 7: 22–37 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dhir V, Bhandari S, Bapat M, et al. Comparison of EUS-guided rendezvous and precut papillotomy techniques for biliary access (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc 2012; 75: 354–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vila JJ, Perez-Miranda M, Vazquez-Sequeiros E, et al. Initial experience with EUS-guided cholangiopancreatography for biliary and pancreatic duct drainage: a Spanish national survey. Gastrointest Endosc 2012; 76: 1133–1141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamao K, Bhatia V, Mizuno N, et al. EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy for palliative biliary drainage in patients with malignant biliary obstruction: results of long-term follow-up. Endoscopy 2008; 40: 340–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hara K, Yamao K, Niwa Y, et al. Prospective clinical study of EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy for malignant lower biliary tract obstruction. Am J Gastroenterol 2011; 106: 1239–1245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee BH, Choe DH, Lee JH, et al. Metallic stents in malignant biliary obstruction: prospective long-term clinical results. Am J Roentgenol 1997; 168: 741–745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]