Abstract

Pediatric audiologists lack evidence-based, age-appropriate outcome evaluation tools with well-developed normative data that could be used to evaluate the auditory development and performance of children aged birth to 6 years with permanent childhood hearing impairment. Bagatto and colleagues recommend a battery of outcome tools that may be used with this population. This article provides results of an evaluation of the individual components of the University of Western Ontario Pediatric Audiological Monitoring Protocol (UWO PedAMP) version 1.0 by the audiologists associated with the Network of Pediatric Audiologists of Canada. It also provides information regarding barriers and facilitators to implementing outcome measures in clinical practice. Results indicate that when compared to the Parents’ Evaluation of Aural/Oral Performance of Children (PEACH) Diary, audiologists found the PEACH Rating Scale to be a more clinically feasible evaluation tool to implement in practice from a time, task, and consistency of use perspective. Results also indicate that the LittlEARS® Auditory Questionnaire could be used to evaluate the auditory development and performance of children aged birth to 6 years with permanent childhood hearing impairment (PCHI). The most cited barrier to implementation is time. The result of this social collaboration was the creation of a knowledge product, the UWO PedAMP v1.0, which has the potential to be useful to audiologists and the children and families they serve.

Keywords: knowledge translation, knowledge-to-action framework, communities of practice, outcome measures, outcome evaluation, audiological monitoring, infants, children, hearing loss, hearing aids, desired sensation level (DSL)

Introduction

Bagatto and colleagues (Bagatto, Moodie, Seewald, Bartlett, & Scollie, in 2011b) provide an overview of the importance of early and appropriate amplification for auditory system development in the young child with permanent childhood hearing impairment (PCHI). The authors also describe the dilemma faced by pediatric audiologists in the hearing aid–fitting process because of the lack of evidence-based age-appropriate outcome tools with well-developed normative data that could be used to evaluate the auditory development and performance of children with PCHI. This lack of outcome measures inhibits a pediatric audiologist’s ability to work with parents and other health care providers in forming shared decisions regarding individualized aural habilitation plans for children in their care. At the conclusion of the Bagatto et al. (2011b) work, a battery of outcome evaluation tools aimed to systematically appraise several auditory-related outcomes of infants and children with PCHI who wear hearing aids was recommended.

Creating Knowledge to Influence Clinical Practice

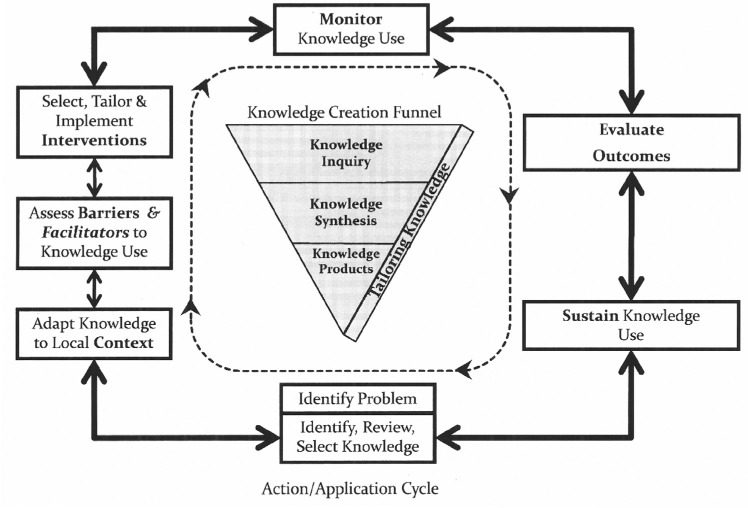

Moodie and colleagues (2011) present an overview of the knowledge-to-action (KTA) framework proposed by Graham and colleagues (2006) and described by others such as Harrison et al. (Harrison, Légaré, Graham, & Fervers, 2010), and Straus et al. (Straus, Tetroe, & Graham, 2009). The KTA framework, as illustrated in Figure 1, is comprised of a knowledge creation funnel and application of knowledge cycle.

Figure 1.

The knowledge-to-action process. Adapted from “Lost in knowledge translation: Time for a map?”, by I.D. Graham, J. Logan, M. B. Harrison, S. E. Straus, J. Tetroe, W. Caswell, and N. Robinson. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 26, p. 19. Copyright 2006 by Wiley and Sons. Reprinted with permission.

The knowledge creation funnel guides the creation of knowledge through several important filtering phases with the end result being the development of tailored knowledge products and tools such as clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) that have the potential to be useful to end users (Harrison et al., 2010; Graham et al., 2006; Straus et al., 2009). Throughout the development of the UWO PedAMP, the creation of knowledge was defined as the social collaboration and negotiation of different perspectives, including personal experience, empirical evidence, and logical deduction that resulted in acceptance of a common result (Brown & Duguid, 2001; Nutley, Walter & Davies, 2003; Stahl, 2000). This definition makes it clear that knowledge creation is collaborative, never absolute, but is subject to change based on future evidence, new questions, interpretation, and negotiation.

Research has shown that knowledge, in the form of CPGs, protocols/procedures will not be implemented into clinical practice merely because they make sense and meet specified needs. They will require a substantive, proactive, and targeted effort for knowledge translation to occur (Graham et al., 2006; Harrison, Graham, & Fervers, 2009; Harrison et al., 2010). Therefore, the KTA framework includes a second, equally important component called “the action cycle” (Graham et al., 2006; Harrison et al., 2009, 2010). The action cycle of the KTA process facilitates the science of clinical implementation. It identifies the activities that should be considered to guide the application of the knowledge in clinical practice, including adaptation of the evidence/knowledge/research for use in local contexts; assessment of the barriers and facilitators to the use of the knowledge; selecting, tailoring, and implementing interventions to ease and promote the use of the knowledge by clinicians; monitoring the use of knowledge; and evaluation of functional and process outcomes of using the knowledge and development of methods to sustain ongoing knowledge use. The application of the knowledge cycle may occur sequentially or simultaneously as the knowledge creation phase (Graham et al., 2006).

Bagatto and colleagues (2011b) completed the inquiry and synthesis stages of the knowledge creation process and compiled evidence for the selection of several evaluation measures for use when examining the auditory development and performance of children with PCHI aged birth to 6 years (Bagatto, Moodie, & Scollie, 2010). The next steps in the KTA framework are the development of a knowledge product (e.g., CPG) and continued tailoring of the CPG to facilitate implementation/uptake in clinical practice.

Moving Knowledge Into Clinical Practice

Our goal in using the KTA framework as a guide for this work is to carefully select, synthesize, and produce a knowledge product (e.g., CPG) that will be consistently applied and adhered to in clinical practice. Adherence to audiology CPG protocols and recommendations, like many of the health sciences professions, is an issue. In fact, in a 2003 article Mueller noted, “There is a current trend to develop test protocols that are “evidence based.” . . . But, before we develop any new fitting guidelines, maybe we should first try to understand why there is so little adherence to the ones we already have” (Mueller, 2003, p. 26). If adherence is defined as “the extent to which a practitioner uses prescribed interventions and avoids those that are proscribed” (Fixsen, Naoom, Blase, Friedman, & Wallace, 2005, p. 81), then there is a need to gain a better understanding of factors associated with implementation of new knowledge into clinical practice to ensure we develop a CPG that is evidence based and is more likely to be adhered to in clinical practice.

The Dilemma of Clinical Implementation of Evidence

The term implementation refers to the uptake of research knowledge and/or other evidence-based practice (EBP) protocols into clinical practice through a specified set of activities (e.g., the predefined written procedural steps within a CPG) with the objective of changing clinical behavior and improving the quality and effectiveness of health care (Durlak & DuPre, 2008; Eccles, Armstrong, Baker, & Sibbald, 2009; Fixsen, Naoom, Blase, Friedman, & Wallace, 2005; Graham et al., 2006). Implementation of evidence into clinical practice is a complex process consisting of several defined functional, nonlinear, and recursive stages that do not occur in isolation; they occur within the practice context and are influenced by organizational and economic factors (Damschroder et al., 2009; Estabrooks, Floyd, Scott-Findlay, O’Leary, & Gushta, 2003; Estabrooks, Wallin, & Milner, 2003; Fixsen et al., 2005; Glasgow & Emmons, 2007; Rycroft-Malone, 2004; Rycroft-Malone et al., 2004). As discussed in Moodie and colleagues (2011) and illustrated in Appendix A, analyses of the barriers to practice change indicate that obstacles to change arise at many different levels: at the level of the guideline, the individual practitioner, the context in which they work, the wider practice environment, and at the level of the patient (Damschroder et al., 2009; Estabrooks, Floyd et al., 2003; Estabrooks, Wallin et al., 2003; Fixsen et al., 2005; Glasgow & Emmons, 2007; Greenhalgh, Robert, Macfarlane, Bate, & Kyriakidou, 2004; Grol, Bosch, Hulscher, Eccles, & Wensing, 2007; Grol & Grimshaw, 2003; Légaré, 2009; McCormack et al., 2002; Rycroft-Malone, 2004; Rycroft-Malone et al., 2004).

Barriers to implementation can be divided into extrinsic (e.g., organizational and wider practice environment) and intrinsic (e.g., guideline and individual practitioner) factors (Moodie et al., 2011; Shiffman, 2009). Extrinsic factors can be difficult to capture and control during the guideline development process but may be considered during the tailoring stage/phase. However, factors hindering implementation at the individual and guideline level can be identified and remedied by guideline authors during the knowledge creation phase. If they are not captured during the knowledge creation phase then they must be identified and remedied prior to or during the implementation phase.

Acknowledging the Complexity of Changing Clinical Practice

Research in the area of implementation and changing clinical practice behavior comes from several theories, including Everett Rogers’ diffusion of innovations theory (DoI). Diffusion, according to Rogers, can be defined as the process by which an innovation is communicated through various channels over time among members of a social system (Rogers, 2003). The spread of novel ideas can be spontaneous or planned, but the four main elements by which diffusion occurs remain the same. These elements are innovation (the perceived new knowledge or product), communication channels (information sharing among people), social systems (groups through which innovation is diffused), and time (time for innovation to diffuse to all adopters). Most important, for the KTA framework, the DoI theory suggests that the perception of the end users or adopters regarding the characteristics of the knowledge that they are asked to implement helps explain different rates of implementation/adoption. End users will choose to adopt a knowledge product or innovation on the basis of their perception of its relative advantage, compatibility, complexity, trialability, and observability (Grol et al., 2007). Appendix B provides a description of these terms for the interested reader (Moodie et al., 2011).

A second theory that can be used to acknowledge and better understand the complexity of changing clinical practice is the theory of planned behavior (TPB). The TPB encompasses a comprehensive list of behavior influences known to affect knowledge product/innovation utility and health care practitioner’s behavior. According to the TPB, human behavior is primarily rational and motivated by factors that result in systematic decision making that affects behavior (Azjen, 1991). Once defined, motivational factors can be used to predict, alter, and explain individual behavior(s). The TPB states that intention (attitudes toward the behavior, beliefs about the opinions of others with respect to the behavior) and perceived control over the behavior (perceived ability to perform the behavior) directly influence the targeted behavior. Attitudes are determined by an individual’s perceptions of the consequences of his or her behavior. Subjective norms are based on the perceptions of the preferences of others for the individual to adopt a behavior. Perceived control over the behavior is derived from the notion of self-efficacy.

Both the DoI theory and the TPB have been utilized in a number of recent implementation research studies, and the constructs associated with these and other theories have been shown to be valuable in developing interventions to change behavior (Brouwers, Graham, Hanna, Cameron, & Browman, 2004; Ceccato, Ferris, Manuel, & Grimshaw, 2007; Eccles, Johnson et al., 2007; Eccles, Grimshaw et al., 2007; Francis et al., 2009; Michie, Fixsen, Grimshaw, & Eccles, 2009; Ramsay, Thomas, Croal, Grimshaw, & Eccles, 2010). Evidence has shown that the uptake of knowledge products is, at least in part, a function of the adoptors’ perceptions about the attributes of the knowledge product and the process by which the knowledge is developed and translated to clinical practice (Brouwers et al., 2004; Ceccato et al., 2007; Eccles et al., 2007a, 2007b; Francis et al., 2009; Graham et al., 2006; Légaré, 2009; Michie et al., 2009; Ramsay et al., 2010).

Research has also shown that health care practitioners want their knowledge, perceptions, and beliefs heard, acknowledged, and implemented as part of the CPG development process (Browman & Brouwers, 2009; Browman, Makarski, Robinson, & Brouwers, 2005; Evans, Graham, Cameron, Mackay, & Brouwers, 2006; Fung-Kee-Fung et al., 2009; Stern et al., 2007). By doing this “up front” (prior to a dissemination and/or implementation phase and during the CPG development process) we have the potential to produce more than the small-to-moderate implementation effects currently reported in the CPG uptake literature (Eccles et al., 2009; Hakkennes & Dodd, 2008; McCormack et al., 2002; Rycroft-Malone, 2004; Rycroft-Malone et al., 2004, 2002; Wensing, Bosch, & Grol, 2009). In addition, we have the opportunity to increase adherence to the CPG, ultimately affecting patient outcomes and quality of provided care.

Throughout the knowledge creation phase, the KTA framework emphasizes the need to tailor the knowledge, refine it, and develop a knowledge product at the end of the process that will be acceptable to practitioners and adopted into clinical practice.

With this in mind, the authors of the University of Western Ontario Pediatric Audiological Monitoring Protocol Version 1.0 (UWO PedAMP v1.0; Bagatto et al., 2010) collaborated in a project with The Network of Pediatric Audiologists of Canada (Moodie et al., 2011) throughout the knowledge creation phase to obtain objective and subjective feedback regarding the components of the UWO PedAMP. We also requested their feedback regarding barriers and facilitators to implementing outcome measures within the context in which they work. This article will present and discuss the results of this project.

Our objective in this study was to gather information relative to end-users’ perceptions of the knowledge product and its use in their clinical practice to assist us to (a) develop an implementable CPG to measure auditory-related outcomes of infants and children with PCHI, and (b) develop an appropriate understanding of barriers and facilitators/interventions that could be used for translating the desired knowledge into action in clinical practice.

Method

Participants

Participants were pediatric audiologists who had been invited to be members of The Network of Pediatric Audiologists of Canada. This group initially consisted of 25 pediatric audiologists and/or pediatric audiology department managers from six provinces in Canada.

In 2008, researchers associated with the Child Amplification Laboratory (CAL) at The National Centre for Audiology (NCA), UWO, met with this group to discuss (a) the potential interest in establishing a community of practice (CoP) in pediatric audiology across Canada with the aim of reducing the KTA gap for children receiving audiological services, and (b) to define areas of practice where these pediatric audiologists felt that there was a lack of knowledge in the treatment for children receiving audiological services. During the one-and-a-half-day meeting, the pediatric audiologists discussed the challenges to implementing evidence into clinical practice. The audiologists reached consensus that an area that they would like to have more knowledge and evidence for use in clinical practice was outcome measures to evaluate the auditory development of children with PCHI aged birth to 6 years who wear hearing aids. They also agreed that they would like to work as a country-wide CoP and in collaboration with researchers at the NCA to develop this knowledge. Prior to the start of the project, after our initial focus group meetings, three audiologists withdrew from the Network; two of them left because of job change and one for career change. This left 22 pediatric audiologists to evaluate the initial components of the UWO PedAMP.

Ethics

This study was reviewed and approved by The University of Western Ontario’s Research Ethics Board for Health Sciences Research.

Survey Instruments

Two questionnaires were developed for use in this project, a preevaluation questionnaire and a questionnaire that allowed participants to individually evaluate the components of the UWO PedAMP v1.0. Prior to sending the questionnaires to the pediatric audiologists each was reviewed by the research/authorship team that included experts in the areas of audiology, research design, and methodology and knowledge translation to ensure clarity of instructions and feasibility of the online approach to data collection.

Preevaluation questionnaire

The preevaluation questionnaire was developed for use in this project as there was no previously developed, validated questionnaire that covered all of the important constructs that we wished to measure. The preevaluation questionnaire was completed prior to having the Network review any of the proposed components of the UWO PedAMP. It was comprised of a letter of information and 84 items for the pediatric audiologists’ consideration. The items were developed based on the KTA framework and characteristics of the guideline, practitioner, and context in which pediatric audiologists work that influence the use of knowledge and evidence in clinical practice. Consideration during item development was also given to the theories of DoI and TPB. Some item wording was developed from other similar work (Brouwers et al., 2004; Ceccato et al., 2007; Eccles et al., 2007a; Evans et al., 2006; Francis et al., 2009; Gerrish et al., 2007; Michie et al., 2009; Quiros, Lin, & Larson, 2007; Ramsay et al., 2010; Shiffman et al., 2005). An email invitation to participate in the preevaluation survey was sent to the members of the Network of Pediatric Audiologists of Canada with a link to the e-survey. The online survey tool SurveyMonkey™ (www.surveymonkey.com) was used for this study. The decision to use an online survey system over a focus group was to enable pediatric audiologists from across the country to participate. Gathering the participants in one place for a focus group meeting was time and cost prohibitive. The items were presented in SurveyMonkey with clear instructions asking the respondent to indicate level of knowledge, familiarity, and/or comfort using a 3-point rating scale, and level of agreement or disagreement using a 5-point scale. Participants were also invited to provide additional written/typed information or comments where they felt appropriate and helpful.

Questionnaire to Individually Evaluate the Components of the UWO PedAMP v1.0

The second questionnaire that was developed for this project was used by the pediatric audiologists to individually evaluate the components of the UWO PedAMP v1.0. This included the two auditory-related pediatric subjective outcome evaluation tools that were being considered for inclusion in the UWO PedAMP guideline: the LittlEARS® Auditory Questionnaire (Tsiakpini et al., 2004) and the Parents’ Evaluation of Aural/Oral Performance of Children (PEACH) Rating Scale (Ching & Hill, 2005b). The pediatric audiologists also evaluated the PEACH Diary (Ching & Hill, 2005a) in this project, using the same questionnaire so that we could compare their ratings of the PEACH Rating Scale and PEACH Diary to ensure that our choice of using the rating scale over the diary reflected the opinion of pediatric audiologists in clinical practice.

Each of the three measures identified above, (1) the LittlEARS Auditory Questionnaire, (2) the PEACH Rating Scale, and (3) the PEACH Diary, were evaluated using a 41-item questionnaire. SurveyMonkey™ was used to present an overview of each measure, provide the respondent with a copy of the outcome evaluation tool, and when applicable, a copy of the corresponding evaluation tool score sheet. While examining these materials, the pediatric audiologists were asked to respond to the 41-item questionnaire that aimed to assess the following: relevancy of the tool for use in clinical practice, quality, feasibility, utility, executability, acceptability, applicability, comparative value, and personal motivation to use the outcome evaluation tool. The pediatric audiologists were provided with clear instructions and a 5-point rating scale to indicate level of agreement or disagreement for each item statement. Participants were also provided with a 4-point rating scale to indicate level of recommendation for each of the outcome evaluation tools and asked whether they would recommend it as part of preferred clinical practice and whether they would use it as part of a guideline. Participants were invited to provide additional written information or comments where they felt they would be appropriate and helpful. Some item wording was borrowed directly or was worded similarly to other work (Brouwers et al., 2004; Ceccato et al., 2007; Eccles et al., 2007a; Evans et al., 2006; Francis et al., 2009; Gerrish et al., 2007; Michie et al., 2009; Quiros et al., 2007; Ramsay et al., 2010; Shiffman et al., 2005). Participants received each of the outcome evaluation tools in random order. When the participant completed his or her evaluation of each measure he or she sent an email message to the lead author (Moodie) who sent them an electronic link to the next questionnaire, until each participant had individually evaluated all of the tools. This ensured that participants did not get overwhelmed by seeing the whole package at once. Participants were asked to, but not required to, identify themselves on their evaluations. Periodic email reminders were sent to the Network of Pediatric Audiologists to encourage participants to complete all of the evaluations.

For this study, data analyses were descriptive in nature. Detailed statistical analyses were not performed on the survey data as the study aimed to provide an overall picture of pediatric audiologists’ perceptions of the UWO PedAMP v1.0. The respondents were not required to provide responses to all questions; therefore, the sample size may vary slightly from question to question. The content of the open-ended responses were examined to see how they enhanced our understanding of the objective measures.

Results

The years of experience as a pediatric audiologist for participants in this project ranged from less than 1 year to 30 years with a mean of 15.25 years.

Preevaluation Survey

The preevaluation survey was sent to 22 pediatric audiologists. Completed surveys were received from 20 providing a 91% response rate.

Current level of knowledge

Eighty percent (16 out of 20) of the pediatric audiologists responding to this preevaluation survey indicated that they would rate their current level of knowledge regarding outcome measurement tools in audiology as somewhat knowledgeable. All of the respondents (100%) indicated that their current knowledge regarding auditory behaviors in infants and children aged birth to 6 years was somewhat to very knowledgeable.

How do pediatric audiologists decide which outcome evaluation tool(s) to use in practice?

The pediatric audiologist respondents decide most frequently which outcome evaluation tools to use in clinical practice based on protocols, guidelines, and education programs. Table 1 provides a list, from most frequently cited to least frequently cited, of how they currently decide which outcome evaluation tools for hearing-related behaviors in infants and children that they use in clinical practice.

Table 1.

List of How Canadian Network Audiologists Currently Decide Which Outcome Evaluation Tools for Auditory-Related Behaviors in Infants and Children to Use in Clinical Practice (in Rank Order From Most Cited to Least Cited Measure)

| 1. | Information I get from provincial infant hearing program protocols |

| 2. | Information I get from continuing education programs |

| 3. | Information I get from preferred practice guidelines |

| 4. | Information I learn about each patient/client as an individual |

| 5. | Information my fellow audiologists share |

| 6. | Information I learned during my education/training |

| 7. | New research that I learn about at conferences |

| 8. | Information I get from attending conferences |

| 9. | My personal experience of caring for patients/clients over time |

| 10. | The way that I am “regulated” or “told” to do it at my work setting (procedural requirement) |

| 11. | Information I get from audiology regulatory bodies at the provincial level |

| 12. | Articles published in peer-reviewed audiology journals |

| 13. | Information more experienced clinical audiologists share |

| 14. | Articles published in online journals (Audiology Online) |

| 15. | Information I get from attending in-service workshops |

| 16. | Information I get form the Internet |

| 17. | My intuitions about what seems to be “right” for the patient/client |

| 18. | Information that I learn about from manufacturers’ representatives |

| 19. | What has worked for me in the past |

| 20. | Information I get from product literature |

| 21. | Information in textbooks |

| 22. | Articles from “trade” journals (e.g., Hearing Review) |

| 23. | The way I have always done it |

| 24. | What physicians/ENTs discuss with me |

| 25. | Information I get from the media |

| 26. | Information I get from audits of my client records |

| 27. | Other |

Evidence-based outcome evaluation tools

The pediatric audiologists all agreed (100%) that there is a need to use evidence-based outcome evaluation tools in practice and that though some tools do exist there is a need to develop evidence-based outcome evaluation tools to monitor auditory-related behaviors in infants and children aged birth to 6 years. These tools would have value for their clinical practice and the place where they work would have value for outcome evaluation tools.

What methods for monitoring auditory-related behaviors are pediatric audiologists currently using?

When asked to provide a list of their current method(s) for monitoring auditory-related behaviors in infants and children, 19 out of 20 clinicians provided responses. All clinicians used more than one means of monitoring auditory-related behaviors. The final list of 23 potential methods is provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

List of the Outcome Evaluation Tools Currently Being Used in Clinical Practice to Monitor Auditory-Related Behaviors in Infants and children (in No Particular Order)

| 1. | Parental observation and report |

| 2. | Consult speech-language pathologist and/or auditory-verbal therapist |

| 3. | Aided soundfield measures and aided hearing threshold measures |

| 4. | Use the SPLogram and evaluate proximity to prescriptive (DSL) target |

| 5. | Aided speech perception scores in quiet and noise |

| 6. | Infant-Toddler Meaningful Auditory Integration Scale (IT-MAIS) or Meaningful Auditory Integration Scale (MAIS). |

| 7. | Parents’ Evaluation of Aural/Oral Performance of Children (PEACH) |

| 8. | Early Listening Function (ELF) |

| 9. | Children’s Home Inventory of Listening Difficulties (CHILD) |

| 10. | LittlEARS Auditory Questionnaire |

| 11. | Processing and Cognitive Enhancement (PACE) |

| 12. | Screening Identification for Targeting Educational Risk (SIFTER) |

| 13. | Client-Oriented Scale of Improvement (COSI) |

| 14. | Early Speech Perception Test (ESP) |

| 15. | Glendonald Auditory Screening Procedure (GASP) |

| 16. | Multi-Syllabic Lexical Neighborhood Test (MLNT)— Iler-Kirk, Pisoni, & Osberger, 1995 |

| 17. | Word intelligibility by picture identification (WIPI) |

| 18. | WD22 word list |

| 19. | Preschool Language Scale (PLS-4) |

| 20. | Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT) |

| 21. | Ling 6 sound test |

| 22. | tykeTalk communication checklist |

| 23. | Toronto preschool speech & language development milestone checklist |

Note: Publication references for some of the outcome evaluation tools listed above have been provided in the reference section of this article.

Approximately half of the pediatric audiologists reported that they were somewhat familiar (53%) with the reliability and/or validity of the outcome evaluation tools they currently use in clinical practice. Approximately, one third (37%) reported that they were not familiar at all with the reliability and validity of the outcome evaluation tools they currently used.

Knowledge and selecting appropriate tools

Only one out of the 20 pediatric audiologist respondents rated him or herself as very comfortable in knowing what auditory-related behaviors to measure in infants and children and in selecting an appropriate evaluation tool. Most rated themselves as somewhat comfortable in knowing what auditory -related behaviors to measure (90%), selecting appropriate evaluation tools (70%), and knowing whether evaluation tools are available (80%).

When asked to rate the level of agreement they had with the statement, “I feel that the outcome evaluation tools for monitoring auditory-related behaviors in infants and children that I currently use provide me with relevant information on which to base treatment decisions,” 65% of audiologists agreed that they did (13 out of 20), 25% (5 out of 20) provided a neutral response, and 10% (2 out of 20) indicated that they disagreed strongly with the statement.

Barriers to implementing/utilizing tools to measure/monitor auditory-related behaviors in children aged birth to 6 years

Pediatric audiologists responding to the e-survey were asked to rate their level of agreement from agree strongly to disagree strongly relative to potential barriers that might be present in implementing/utilizing tools to measure auditory-related behaviors in children aged birth to 6 years. The results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Level of Agreement With Statements Related to Barriers to Implementing/Utilizing Tools to Measure Auditory-Related Behaviors in Children Aged Birth to 6 Years

| Level of agreement |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Agree to agree strongly (%) | Neither agree nor disagree (%) | Disagree to disagree strongly (%) | |

| There are insufficient resources (e.g., equipment) where I work to implement outcome measures for monitoring hearing-related behaviors in infants and children | 0 | 15 | 85 |

| The colleagues in my work setting are not receptive to changing practice | 5 | 15 | 80 |

| I lack the authority in my work setting to implement new measures or protocols | 5 | 15 | 80 |

| Implementation of outcome measures for monitoring hearing-related behaviors in infants and children will require too many organizational changes where I work | 5 | 10 | 85 |

| The child will not be able to perform the tasks required of him or her as part of outcome measures for monitoring hearing-related behaviors in infants and children | 5 | 25 | 70 |

| I do not feel that I have the necessary technical skills to implement outcome measures for monitoring hearing-related behaviors in infants and children | 0 | 15 | 85 |

| There is not enough leadership at my workplace to implement outcome measures for monitoring hearing-related behaviors in infants and children | 5 | 10 | 85 |

| It will be too costly to set up my/our clinic to perform outcome measures for monitoring hearing-related behaviors in infants and children | 0 | 20 | 80 |

| The culture in my work setting is not conducive to implementing outcome measures for monitoring hearing-related behaviors in infants and children | 0 | 15 | 85 |

| There is a lack of institutional support where I work for implementing outcome measures for monitoring hearing-related behaviors in infants and children | 0 | 15 | 85 |

| The parent will not be able to perform the tasks required of him or her as part of outcome measures for monitoring hearing-related behaviors in infants and children | 10 | 30 | 60 |

| I do not feel confident about initiating change in my clinical practice | 15 | 5 | 80 |

| There is insufficient time where I work for me to implement outcome measures for monitoring hearing-related behaviors in infants and children | 15 | 30 | 55 |

| Outcome measures for monitoring hearing-related behaviors in infants and children are too complex to incorporate into current practice | 0 | 20 | 80 |

| I do not believe that outcome measures for monitoring hearing-related behaviors in infants and children are beneficial | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| I do not have colleagues that I could go to for support when implementing outcome measures for monitoring hearing-related behaviors in infants and children | 0 | 10 | 90 |

| Outcome measures for monitoring hearing-related behaviors in infants and children are too time consuming to incorporate into current practice | 5 | 45 | 50 |

| The parent will not take the time to perform the tasks required of him or her as part of outcome measures for monitoring hearing-related behaviors in infants and children | 20 | 45 | 35 |

| I will require training to learn to implement outcome measures for monitoring hearing-related behaviors in infants and children | 70 | 25 | 5 |

| ENTs/physicians I work with are supportive of my implementing outcome measures for monitoring hearing-related behaviors in infants and children | 55 | 45 | 0 |

When asked to list the top five barriers to implementing outcome evaluation tools in their practice they responded with the following (#1 being the greatest barrier):

There is insufficient time.

The parent will not take the time to perform the tasks required of him or her as part of outcome evaluation tools.

Outcome evaluation tools are too time consuming to incorporate into current practice.

The following two barriers were rated equally as the fourth greatest barriers. They are as follows:

4. The parent will not be able to perform the tasks required of him or her as part of outcome evaluation.

4. The child will not be able to perform the tasks required of him or her as part of outcome evaluation,

The fifth greatest barrier was reported as:

5. I will require training to learn to implement outcome evaluation tools.

Facilitators to implementing/utilizing tools to measure/monitor auditory-related behaviors in children aged birth to 6 years. Table 4 provides a list of potential facilitators recommended by the audiologists to assist with implementing/utilizing tools to measure auditory-related behaviors in children aged birth to 6 years.

Table 4.

Level of Agreement With Statements Related to Facilitators to Implementing/Utilizing Tools to Measure Auditory-Related Behaviors in Children Aged Birth to 6 Years

| Level of agreement |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Agree to agree strongly (%) | Neither agree nor disagree (%) | Disagree to disagree strongly (%) | |

| Making a personal commitment to implement outcome measures for monitoring hearing-related behaviors in infants and children will facilitate implementation | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Receiving hands-on training will facilitate implementation of outcome measures for monitoring hearing-related behaviors in infants and children | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Getting timely feedback from expert(s) when I have a question will facilitate implementation of outcome measures for monitoring hearing-related behaviors in infants and children | 95 | 5 | 0 |

| Having managers/admin understand the benefits of the protocol will facilitate implementation of outcome measures for monitoring hearing-related behaviors in infants and children | 95 | 5 | 0 |

| Managers/administrators where I work are supportive of my implementing outcome measures for monitoring hearing-related behaviors in infants and children | 85 | 10 | 5 |

| Flowcharts of test measures will facilitate implementation of outcome measures for monitoring hearing-related behaviors in infants and children | 80 | 20 | 0 |

| Having trained “leaders” onsite will facilitate implementation of outcome measures for monitoring hearing-related behaviors in infants and children | 75 | 15 | 10 |

| Trying the protocol out one measurement at a time will facilitate the implementation of an entire protocol related to outcome measures for monitoring hearing-related behaviors in infants and children | 75 | 25 | 0 |

| Audiologist colleagues where I work are supportive of my implementing outcome measures for monitoring hearing-related behaviors in infants and children | 75 | 25 | 0 |

| Receiving quarterly reports on my progress will facilitate implementation of outcome measures for monitoring hearing-related behaviors in infants and children | 65 | 25 | 10 |

| Having a DVD to watch where other clinicians have implemented the protocol will facilitate implementation of outcome measures for monitoring hearing-related behaviors in infants and children | 60 | 40 | 0 |

| Having an expert observe me to ensure that I am performing the measurements properly will facilitate implementation of outcome measures for monitoring hearing-related behaviors in infants and children | 35 | 50 | 15 |

| ENTs/physicians I work with are supportive of my implementing outcome measures for monitoring hearing-related behaviors in infants and children | 50 | 50 | 0 |

The top five facilitators for implementation of outcome evaluation tools for monitoring auditory-related behaviors in infants and children recommended by the audiologists are (#1 being the greatest facilitator):

Receiving hands-on training,

Flowcharts of test measures,

Trying the protocol out one measurement at a time,

Getting timely feedback from expert(s) when I have a question.

The following three facilitators were rated equally as the fifth greatest facilitator(s). They are as follows:

5. Making a personal commitment to implement outcome evaluation tools,

5. Support from audiologist colleagues where I work,

5. Support from managers/administrators where I work.

Pediatric Audiologist’s Individual Evaluation of the Components of the UWO PedAMP Guideline v1.0

After the pediatric audiologists had completed the preevaluation survey they were invited to participate in individually evaluating components under consideration for use in the UWO PedAMP v1.0 using a 41-item questionnaire developed for this project.

Individual evaluation of the PEACH Rating Scale versus the PEACH Diary

Most participants agreed that the rationale and instructions for use for both the PEACH Rating Scale and PEACH Diary were stated clearly, specifically, and unambiguously in the UWO PedAMP documentation. However, on approximately 75% of the questions related to quality, feasibility, utility, executability, acceptability, applicability, and personal motivation to use the measure, the end-user’s ranking of the PEACH Diary was poorer than the PEACH Rating Scale. Table 5 provides results comparing the rating of the PEACH Rating Scale and the PEACH Diary for many relevant questions. For ease of data examination, we have collapsed the rating scale from 5 point to 3 point by combining the responses for the categories agree to agree strongly and disagree to disagree strongly.

Table 5.

Individual Evaluation of the Parents’ Evaluation of Aural/Oral Performance of Children (PEACH) Rating Scale Versus the PEACH Diary

| Level of agreement |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statement | Measure | Agree to agree strongly (%) | Neither agree nor disagree (%) | Disagree to disagree strongly (%) |

| The task related to the XXX is not too difficult for the respondent (parent) to perform | PEACH Rating Scale | 73 | 13 | 13 |

| PEACH Diary | 13 | 7 | 80 | |

| The task related to the XXX is not too time consuming for the interviewer (audiologist) to perform | PEACH Rating Scale | 80 | 7 | 13 |

| PEACH Diary | 27 | 20 | 53 | |

| Interpretation of results for the XXX is straightforward | PEACH Rating Scale | 64 | 14 | 21 |

| PEACH Diary | 33 | 27 | 40 | |

| Patient results for the XXX can be reported with ease | PEACH Rating Scale | 80 | 13 | 7 |

| PEACH Diary | 27 | 33 | 40 | |

| Clinicians across work settings will be able to execute the XXX in a consistent way | PEACH Rating Scale | 73 | 7 | 20 |

| PEACH Diary | 14 | 36 | 50 | |

| It is clinically feasible to perform the XXX in my pediatric audiology practice | PEACH Rating Scale | 87 | 7 | 7 |

| PEACH Diary | 36 | 14 | 50 | |

| The XXX is suitable for routine use in pediatric audiology settings | PEACH Rating Scale | 80 | 13 | 7 |

| PEACH Diary | 33 | 13 | 53 | |

| The use of the XXX is likely to be supported by the manager/administrator in my work setting | PEACH Rating Scale | 86 | 14 | 0 |

| PEACH Diary | 50 | 29 | 21 | |

| Parents cannot perform the task required of them in the XXX | PEACH Rating Scale | 13 | — | 73 |

| PEACH Diary | 36 | 36 | 27 | |

| The XXX will take too much time for the parent to complete | PEACH Rating Scale | 7 | 13 | 80 |

| PEACH Diary | 73 | 20 | 7 | |

| The XXX can be used by clinicians without the acquisition of new knowledge and skills | PEACH Rating Scale | 73 | 20 | 7 |

| PEACH Diary | 27 | 20 | 53 | |

| The XXX is cumbersome and inconvenient | PEACH Rating Scale | 13 | 0 | 87 |

| PEACH Diary | 60 | 20 | 20 | |

| The XXX reflects a more effective approach for monitoring hearing-related behaviors in infants and children than what I am currently doing in my practice | PEACH Rating Scale | 55 | 33 | 13 |

| PEACH Diary | 73 | 7 | 20 | |

| When applied, the XXX will result in better use of resources than current usual practice | PEACH Rating Scale | 27 | 53 | 20 |

| PEACH Diary | 47 | 40 | 13 | |

An examination of the two questions asked relating to comparative value shows that participants agreed that both the PEACH Rating Scale and the PEACH Diary reflected a more effective approach for monitoring auditory-related behaviors in infants and children than what they were currently doing in practice; however, their choice of the ranking neither agree nor disagree indicates that they are unsure that when applied in practice that either of these measures will result in better use of resources than what they are currently doing (53% of respondents choose neither agree nor disagree that the PEACH Rating Scale results in better use of resources than current usual practice and 40% of respondents chose the same category for the PEACH Diary).

Finally, participants were asked three questions related to implementation of the PEACH Rating Scale and/or the PEACH Diary in clinical practice. Table 6 provides the results of these questions for the two measures.

Table 6.

Implementing the Parents’ Evaluation of Aural/Oral Performance of Children (PEACH) Rating Scale Versus the PEACH Diary in Clinical Practice

| Level of agreement |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statement | Measure | Agree to agree strongly (%) | Neither agree nor disagree (%) | Disagree to disagree strongly (%) | |

| The XXX should be implemented as part of preferred practice | PEACH Rating Scale | 33 | 47 | 20 | |

| PEACH Diary | 20 | 33 | 47 | ||

| Level of likelihood to implement measure |

|||||

| Statement | Measure | Very likely (%) | Moderately likely (%) | Not likely at all (%) | |

| In its current form (as you have reviewed it today), if the XXX became part of a practice guideline, how likely would you be to make use of it in your daily practice? | PEACH Rating Scale | 33 | 53 | 13 | |

| PEACH Diary | 33 | 27 | 40 | ||

| Level of recommendation for use in clinical practice |

|||||

| Statement | Measure | Strongly recommend (%) | Recommend (with alterations, %) | Would not recommend (%) | Unsure (%) |

| In its current form (as you have reviewed it today), would you recommend the XXX for use in clinical practice? | PEACH Rating Scale | 33 | 47 | 13 | 7 |

| PEACH Diary | 0 | 47 | 53 | 0 | |

In terms of clinical implementation, more respondents indicated that the PEACH Diary should not be implemented as part of preferred practice. However, it should be noted that only 33% of respondents agreed that the PEACH Rating Scale should be implemented. Many respondents (47%) indicated that they would like to see alterations made to both measures before they recommended them for clinical practice use. In its current form (as they reviewed it at the time) 53% of respondents were moderately likely to make use of the PEACH Rating Scale in daily practice if it became part of a CPG. Forty-percent (40%) of respondents indicated that they would not be likely at all to use the PEACH Diary in daily practice if it became part of a CPG.

Pediatric audiologist’s open-ended comments regarding the PEACH Rating Scale and the PEACH Diary

The pediatric audiologists participating in this evaluation of the UWO PedAMP v1.0 provided open-ended comments for both the PEACH Rating Scale (n = 10) and the PEACH Diary (n = 8). The goal for including an open-ended comment section for this survey was to identify, isolate, and explore salient points that the pediatric audiologists wanted brought to the UWO PedAMP authors’ attention. Most comments were positive in nature and aimed at providing constructive input to the development of the UWO PedAMP v1.0. Comments related primarily to trialability, time, English as a second language, experience, normative data, counseling parents, and suggested alterations to the measures. Positive, negative, and requested revisions comments are provided in Comments Box 1.

Comments Box 1.

Respondent Comments Regarding the PEACH Diary and PEACH Rating Scale

| POSITIVE COMMENTS “I think that the PEACH Rating Scale will be especially good for clinicians new to pediatric hearing aid fitting.” |

| “Finally . . . I also think that if parents are not convinced that the aids are helping—this would be a great tool to convince them otherwise—by comparing two assessments over time—one with aids and one without. . . . This PEACH Rating Scale may be helpful in convincing parents to keep the hearing aids on all waking hours.” |

| NEGATIVE COMMENTS |

| “If parent completion is expected I find the instructions for each question in the PEACH Diary quite lengthy and feel that some parents may struggle with reading and comprehending the task and what they are to record. Materials in several languages would be necessary for successful implementation.” |

| “I feel that the PEACH Diary will be time consuming and planning of time frames for a visit will need to take into account completion of the PEACH. If a clinician is completing the PEACH with the parents then it could be quite time-consuming. This is also where differences in knowledge and skillset may be reflected. How effective and efficient the clinician is in administering the test will be important to successful implementation in a clinical setting.” |

| SUGGESTIONS FOR REVISIONS |

| “One concern regarding the PEACH is the telephone question and how this is to be interpreted for example some children use Skype/speaker phone is that considered successful use. Also what if the child has never used a phone, they would score a ‘0’ which affects their score in a negative way.” |

| “Materials in several languages would be necessary for successful implementation.” |

| “It would be helpful to have some clear normative data for ages and degrees of hearing loss so that we could tell parents whether their child’s scores are within expected range or not, and to help clinicians know when to consider alternative intervention strategies (e.g., CI, FM).” |

| “I think it would be a good idea to make the last blank section a place to more strongly encourage parents to write out examples and comment, instead of suggesting comments.” |

Selection of the PEACH Rating Scale for inclusion in the UWO PedAMP v1.0

Results of a comparison of the PEACH Rating Scale and the PEACH Diary indicate that the pediatric audiologists included in this sample agreed that the PEACH Rating Scale was a more clinically feasible outcome evaluation tool to implement in practice from a time, task, and consistency of use perspective.

Individual evaluation of the LittlEARS Auditory Questionnaire and the PEACH Rating Scale

This section will provide the results of the pediatric audiologist’s individual evaluation of the LittlEARS Auditory Questionnaire (hereinafter referred to as the LittlEARS). Results from the PEACH Rating Scale evaluations have been included for comparison and discussion purposes. Most participants agreed that the rationale and instructions for use for the LittlEARS and the PEACH Rating Scale were stated clearly, specifically, and unambiguously in the UWO PedAMP documentation. Respondents agreed that scoring for both measures was not difficult. On questions related to quality, feasibility, utility, executability, acceptability, applicability, and personal motivation to use the measure, the end user’s ranking of the LittlEARS and the PEACH Rating Scale were very positive. Table 7 provides results comparing both measures for many relevant questions. For ease of data examination, we have collapsed the rating scale from its 5-point version to a 3-point version by combining the responses for the categories agree to agree strongly and disagree to disagree strongly.

Table 7.

Individual Evaluation of the LittlEARS Auditory Questionnaire and the Parents’ Evaluation of Aural/Oral Performance of Children (PEACH) Rating Scale

| Level of agreement |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statement | Measure | Agree to agree strongly (%) | Neither agree nor disagree (%) | Disagree to disagree strongly (%) |

| The task related to the XXX is not too difficult for the respondent (parent) to perform | LittlEARS Auditory Questionnaire | 88 | 6 | 6 |

| PEACH Rating Scale | 73 | 13 | 13 | |

| The task related to the XXX is not too time consuming for the interviewer (audiologist) to perform | LittlEARS Auditory Questionnaire | 81 | 0 | 19 |

| PEACH Rating Scale | 80 | 7 | 13 | |

| Interpretation of results for the XXX is straightforward | LittlEARS Auditory Questionnaire | 94 | 6 | 0 |

| PEACH Rating Scale | 64 | 14 | 21 | |

| Patient results for the XXX can be reported with ease | LittlEARS Auditory Questionnaire | 88 | 12 | 0 |

| PEACH Rating Scale | 80 | 13 | 7 | |

| Clinicians across work settings will be able to execute the XXX in a consistent way | LittlEARS Auditory Questionnaire | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| PEACH Rating Scale | 73 | 7 | 20 | |

| It is clinically feasible to perform the XXX in my pediatric audiology practice | LittlEARS Auditory Questionnaire | 88 | 6 | 6 |

| PEACH Rating Scale | 87 | 7 | 7 | |

| The XXX is suitable for routine use in pediatric audiology settings | LittlEARS Auditory Questionnaire | 88 | 12 | 0 |

| PEACH Rating Scale | 80 | 13 | 7 | |

| The use of the XXX is likely to be supported by the manager/administrator in my work setting | LittlEARS Auditory Questionnaire | 94 | 6 | 0 |

| PEACH Rating Scale | 86 | 14 | 0 | |

| Parents cannot perform the task required of them in the XXX | LittlEARS Auditory Questionnaire | 6 | 13 | 81 |

| PEACH Rating Scale | 13 | 13 | 73 | |

| The XXX will take too much time for the parent to complete | LittlEARS Auditory Questionnaire | 0 | 13 | 87 |

| PEACH Rating Scale | 7 | 13 | 80 | |

| The XXX can be used by clinicians without the acquisition of new knowledge and skills | LittlEARS Auditory Questionnaire | 69 | 6 | 25 |

| PEACH Rating Scale | 73 | 20 | 7 | |

| The XXX is cumbersome and inconvenient | LittlEARS Auditory Questionnaire | 0 | 19 | 81 |

| PEACH Rating Scale | 13 | 0 | 87 | |

| The XXX reflects a more effective approach for monitoring hearing-related behaviors in infants and children than what I am currently doing in my practice | LittlEARS Auditory Questionnaire | 75 | 19 | 6 |

| PEACH Rating Scale | 53 | 33 | 13 | |

| When applied, the XXX will result in better use of resources than current usual practice | LittlEARS Auditory Questionnaire | 75 | 13 | 13 |

| PEACH Rating Scale | 27 | 53 | 20 | |

An examination of the two questions relating to comparative value shows that participants agreed that the LittlEARS reflected a more effective approach for monitoring auditory-related behaviors in infants and children than what they were currently doing in practice; however, their choice of the ranking neither agree nor disagree most frequently for the PEACH Rating Scale indicates that they are unsure that when applied in practice that the PEACH Rating Scale will result in better use of resources than what they are currently doing. Finally, participants were asked three questions related to implementation of the LittlEARS and the PEACH Rating Scale in clinical practice. Table 8 provides the results of these questions for both measures.

Table 8.

Implementing the LittlEARS and the PEACH Rating Scale in Clinical Practice

| Level of agreement |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statement | Measure | Agree to agree strongly (%) | Agree to agree strongly (%) | Agree to agree strongly (%) | |

| The XXX should be implemented as part of preferred practice | LittlEARS | 75 | 19 | 6 | |

| PEACH Rating Scale | 33 | 47 | 20 | ||

| Level of likelihood to implement measure |

|||||

| Statement | Measure | Very likely (%) | Moderately likely (%) | Not likely at all (%) | |

| In its current form (as you have reviewed it today), if the XXX became part of a practice guideline, how likely would you be to make use of it in your daily practice? | LittlEARS | 56 | 38 | 6 | |

| PEACH Rating Scale | 33 | 53 | 13 | ||

| Level of recommendation for use in clinical practice |

|||||

| Statement | Measure | Strongly recommend (%) | Recommend (with alterations, %) | Would not recommend (%) | Unsure (%) |

| In its current form (as you have reviewed it today), would you recommend the XXX for use in clinical practice? | LittlEARS | 63 | 19 | 12 | 6 |

| PEACH Rating Scale | 33 | 47 | 13 | 7 | |

In terms of clinical implementation, most respondents’ chose the response option agree to strongly agree for implementing LittlEARS as part of preferred practice (75% and 62%, respectively), and only 33% responded with agree to strongly agree for implementing the PEACH Rating Scale as part of preferred practice. In its current form (as they reviewed it at the time) 85% or more of the respondents indicated that they were moderately to very likely to make use of the LittlEARS and the PEACH Rating Scale in daily practice if they became part of a CPG. However, approximately half of the audiologists indicated that they would like to see alterations made to the PEACH Rating Scale before they recommended it for clinical practice use. About 63% of the respondents stated that they would recommend the LittlEARS in its current form for use in clinical practice.

Pediatric audiologist’s open-ended comments regarding LittlEARS and the PEACH Rating Scale

The pediatric audiologists participating in this evaluation of the UWO PedAMP v1.0 provided open-ended subjective comments for the LittlEARS and the PEACH Rating Scale. The goal for including an open-ended comment section for this survey was to identify, isolate, and explore salient points that the pediatric audiologists wanted brought to the UWO PedAMP authors’ attention. Most comments were positive in nature and aimed at providing constructive input to the development of the UWO PedAMP v1.0. Comments related primarily to comparative value, procedural issues, necessary translations, language level, counseling parents, and suggested alterations to the measures. Examples for the LittlEARS are provided in Comments Box 2. Comments related to the PEACH Rating Scale were provided in the previous section of this article.

Comments Box 2.

Respondent Comments Regarding the LittlEARS Auditory Questionnaire

| POSITIVE COMMENTS |

| “The items listed in the LittlEARS questionnaire are very descriptive and provide both accurate and straightforward information regarding the child’s communication development. . . . The items listed in the questionnaire are easy and simple enough for parents to complete and observe in their child; thus aiding as a counseling tool. . . .” |

| “This tool allows for measurement of even small gains in auditory skills. By highlighting gains a parent can feel proud of all their hard work. I see this tool being used with very young children. However I mainly see that I would use it with children who are hearing impaired who are low functioning where it is otherwise not possible to see gain.” |

| NEGATIVE COMMENTS |

| “The LittlEARS questions only cover a limited number of auditory responses a child may display. . . . The disadvantage that it poses is that all questions are closed set and by being limited to questions that only depict certain scenarios, an infant’s true range of auditory behaviors may not be accurately portrayed.” |

| “The process is clinically redundant. However if the concept is simply to document whether the child is doing as they should, given age etc, auditorily under an amplified condition, then it should be divided off into age related sections. If the child is doing as expected in their given age range . . . then done, there is no need to determine if they are doing ‘better’ than expected . . . this information can be provided by the relevant therapist or teacher. If doing ‘worse’ than expected yes certainly appropriate review should be conducted and referrals and/or counseling conducted.” |

| SUGGESTED REVISIONS |

| “There is no need to look for 6 ‘no’s’ in a row, when you are already well above the child’s age range.” |

| “Additionally it would be nice if there were norms on English speakers as well.” |

| “It would be interesting to see what the reports would look like from parents with children with auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder.” |

Discussion

Clinicians wish to make decisions on which outcome evaluation tools to use in clinical practice on the basis of best available evidence. The Network of Pediatric Audiologists of Canada clinicians unanimously agreed that there is a need to use evidence-based outcome evaluation tools in practice. They currently attempt to obtain this best evidence by using measures on the basis of information that they obtain from provincially developed protocols and preferred practice guidelines. They also wish to integrate and balance information on the basis of evidence from their clinical experience and by valuing their young patients and their families as individuals.

All of the invited Network of Pediatric Audiologists of Canada audiologists were motivated to participate in a project to evaluate the components of the UWO PedAMP. This provided them with an opportunity to actively collaborate and negotiate with researchers during the knowledge creation process to ensure that the knowledge product (e.g., CPG) that was being created was tailored in such a way to promote use and adherence within their clinical practice setting.

Most of the Canadian Network audiologists are knowledgeable and comfortable with knowing what auditory-related behaviors to measure, feel that they can select appropriate measurement tools, but many do not feel that the measures they currently use provide them with relevant information on which to base treatment decisions. As shown in Table 2, numerous measures are currently being used in clinical practice to monitor auditory-related behaviors in infants and children. The data presented in Table 2 indicates that there appears to be no consistent battery of outcome evaluation tools being used for the evaluation of auditory development of children aged birth to 6 years with PCHI who wear hearing aids. Many of the tools being used would not be administered during routine audiological appointments and would be administered by other professionals associated with their audiology department (e.g., auditory-verbal therapists and/or speech-language pathologists). Some of the measures listed by respondents would be more useful with children aged 6 years or older (e.g., SIFTER, PACE, ESP, GASP, MLNT, WIPI, and WD22 word list) whereas others primarily assess speech and language development (e.g., PLS-4, PPVT, tykeTalk communication checklist, Toronto preschool speech and language development milestone checklist). For those on the list that are appropriate for use with children aged birth to 6 years, they have not been included in the UWO PedAMP v1.0 because of one or more factors, including they did not have normative data gathered from large-scale studies, they were lengthy, or their administration/respondent burden was high (see Bagatto et al., 2011b).

In the introduction to this article we defined knowledge creation as the social collaboration and negotiation of different perspectives, including personal experience, empirical evidence, and logical deduction that results in acceptance of a common result (Stahl, 2000). This definition can be seen in practice in the decision to use the PEACH Rating Scale over the PEACH Diary within the UWO PedAMP v1.0. If one were to make a decision on which outcome evaluation tool to use in practice, based on the highest ranking or quality of evidence the PEACH Diary would be used. Administration of the PEACH Diary required parents to observe and document a list of auditory-related behaviors over a 1-week period. The PEACH Rating Scale, a paper-and-pencil task where the parents are asked to retrospectively (during the prior week) rate the presence/absence of auditory related behaviors, provides a tool reduced in respondent and administrative burden compared to the PEACH Diary. The Network of Pediatric Audiologists of Canada provided us with an opportunity to have clinicians’ in the field evaluate both formats of the PEACH (the diary and rating scale). One of the benefits of active collaboration with this CoP is that the Network audiologists, regardless of the context in which they worked, made it very clear that they found the PEACH Rating Scale to be a more clinically feasible outcome evaluation tool to include in the UWO PedAMP. They indicated that the PEACH Rating Scale is less difficult to score and interpret, less difficult and time consuming for the caregiver to perform, less time consuming for the audiologist, easier to use the results in reports, more clinically feasible and suitable to use, would have more support and acceptance for use in their workplace setting, would require less development of new skills and knowledge to be able to use, and is more practical to implement. More audiologists indicated that they were likely to use the PEACH Rating Scale in daily practice over the PEACH Diary if it became part of a practice guideline. This made the authors of the UWO PedAMP v1.0 decision to include the PEACH Rating Scale very straightforward and also provided evidence for the choice for this inclusion.

Results show that the Network of Pediatric Audiologists of Canada found the LittlEARS and the PEACH Rating Scale to be clinically feasible to perform in a consistent fashion and that their use in practice would likely be supported by other clinicians and administration/managers within their work context. Approximately 90% of the Network audiologists indicated that they would moderately to very likely implement the measures in their daily practice. This would contribute to the objective of developing a guideline that would produce more than the small-to-moderate implementation effects currently reported in the CPG uptake literature (Eccles et al., 2009; Hakkennes & Dodd, 2008; McCormack et al., 2002; Rycroft-Malone, 2004; Rycroft-Malone et al., 2004, 2002; Wensing et al., 2009).

The KTA framework outlines the activities that may be needed for the application of knowledge in clinical practice (Graham et al., 2006; Graham & Tetroe, 2007; Harrison et al., 2009, 2010; Straus, 2009; Straus et al., 2009). One of the primary steps in the application cycle is the adaptation of the evidence, knowledge and research to the local context. In the development of the UWO PedAMP, the early feedback from the pediatric audiologists provided insight to the potential adaptations that might be necessary. Many of the audiologists work in large, urban, multicultural centers. They noted that having an outcome evaluation tool like the LittlEARS that has been translated into many different languages was beneficial for clinical use and might be more easily implemented into clinical practice. Many noted that the implementation of PEACH Rating Scale could be more problematic because it may have to be administered interview style for parents who did not read English or Canadian French. They also provided input to the researchers on the requirement within some practice contexts to have materials for clinical use that were as close to a Grade 4 reading level as possible. The CAL researchers have worked with audiologists to derive an initial list of languages for the PEACH Rating Scale translation and will continue to work to improve the reading levels of as many materials to closely approximate a Grade 4 reading level.

Another component of the application cycle within the KTA framework is the assessment of barriers to using the knowledge in clinical practice. Some of the Network of Pediatric Audiologists of Canada expressed concern that the UWO PedAMP might require some need for new knowledge/skill development prior to clinical implementation. During the development of the UWO PedAMP training materials (manual, case examples, etc.) we tried to remember that novice audiologists will likely have different expertise and training requirements than more experienced clinicians (Salisbury, 2008a, 2008b). Therefore, we developed case examples that increase in difficulty as part of the UWO PedAMP. The audiologists also indicated concern that parents might not be able to perform the tasks required of the measures in a timely fashion. Some were concerned with the retrospective nature of the PEACH Rating Scale. Some of these barriers can be addressed prior to implementation (development of knowledge/skills), and some will need to be addressed as the implementation phase of the UWO PedAMP develops.

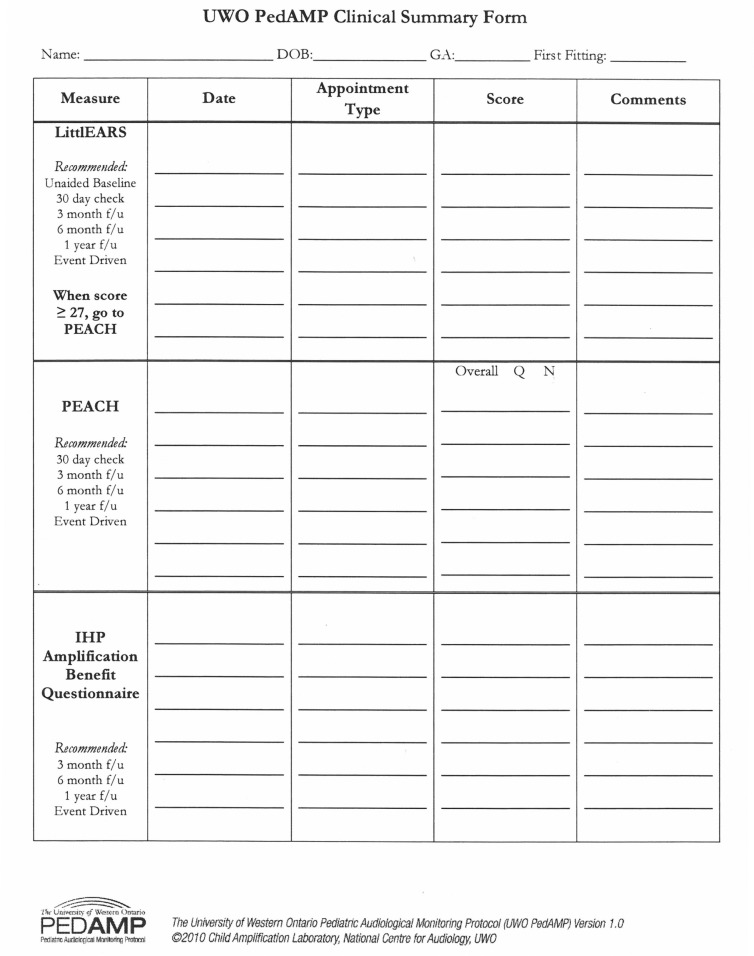

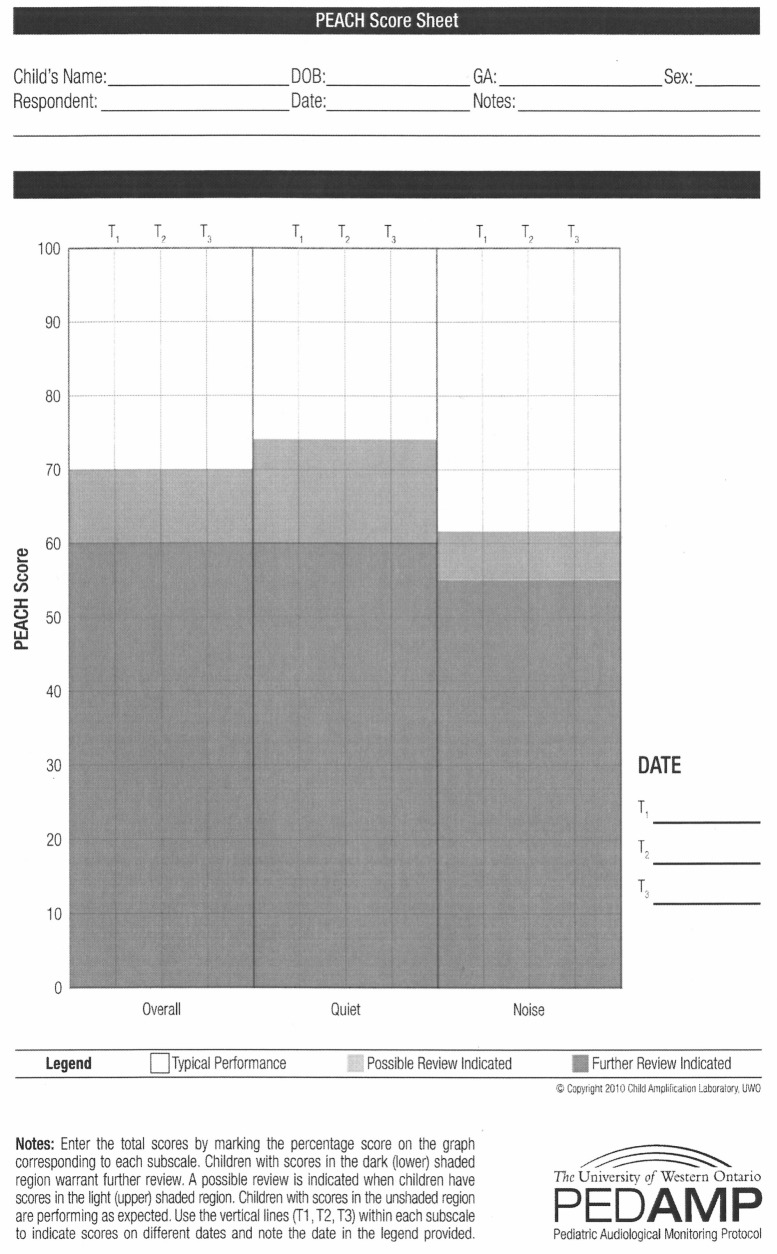

The knowledge-to-action framework indicates that use of the knowledge within clinical practice settings can be facilitated during the application cycle by selecting, tailoring, and implementing interventions to promote clinical uptake of the knowledge (Graham et al., 2006; Graham & Tetroe, 2007; Harrison et al., 2009, 2010; Straus et al., 2009, 2011). With this in mind, written input from the pediatric audiologists was solicited and provided by several who tried out the components of the UWO PedAMP in clinical practice. Their input led to several important changes prior to finalizing the UWO PedAMP for widespread release, including the development of the clinical summary form shown in Figure 2, darkening of lines and shaded regions on the score sheets to make visualization easier, development of a percentage look-up table for the PEACH Rating Scale so that clinicians would not have to use a calculator to determine percentage of correct scores, development of a PEACH score sheet so that performance ranges are clearly visible and individual scores can be interpreted (Figure 3), and the ability to track several appointments on one PEACH Rating Scale score sheet (as indicated by Time 1, Time 2, Time 3 [T1, T2, and T3] areas shown on Figure 3) so that performance over time was more easily visualized.

Figure 2.

The Clinical Summary Form developed for use in the UWO PedAMP v1.0. It can be posted within the child’s patient folder to provide a quick, visual summary of the date, appointment type, score, and other comments on each administration of the UWO PedAMP measures

Note: UWO PedAMP v1.0 = University of Western Ontario Pediatric Audiological Monitoring Protocol.

Figure 3.

The PEACH score sheet developed for use in the UWO PedAMP v1.0. Scores for overall performance, performance in quiet and in noise can be entered on the score sheet for three consecutive times of administration (Time 1, Time 2, Time 3) so that performance over time can be easily viewed

Note: UWO PedAMP v1.0 = University of Western Ontario Pediatric Audiological Monitoring Protocol; peach = Parents’ Evaluation of Aural/Oral Performance of Children.

In addition, questions that the pediatric audiologists asked that related to clinical implementation while they evaluated each of the components of the UWO PedAMP were used to develop case examples and frequently asked questions for each section of the UWO PedAMP manual. The research team hoped that by doing this we anticipated the questions that would most frequently be raised and provided answers/solutions during the training/learning process resulting in more clinical confidence and increase perceived self-efficacy in implementing the measures in clinical practice.

The largest barrier reported by the audiologists to implementing outcome measures into clinical practice was time. An examination of health sciences research literature on barriers to implementing evidence into clinical practice reveals that “lack of time” is a major limitation cited by most clinicians regardless of profession (Harrison et al., 2010; Iles & Davidson, 2006; Maher, Sherrington, Elkins, Herbert, & Moseley, 2004; McCleary & Brown, 2003; McCluskley, 2003; Mullins, 2005; Zipoli & Kennedy, 2005). The Network audiologists were also concerned that parents might not take the time to perform the outcome measurement tasks required of them as part of the UWO PedAMP. This concern might also reflect their clinical expertise because they know that children with hearing loss are often born with other complex health issues that place a large time burden on caregivers. Pediatric audiologists who tried the UWO PedAMP out prior to the final released version indicated that on average it would take them about 15 min of extra appointment time to administer the components of the UWO PedAMP. They were concerned that they would run into appointment-time issues, especially while they were gaining confidence and learning how to administer/interpret the outcome measures. The Network of Pediatric Audiologists of Canada were concerned that the increasing amount of paperwork and time involved in performing these outcome evaluation tools over what they are currently doing in practice may mean that they are spending additional time that they may not receive remuneration for. An additional barrier noted to clinical implementation of the LittlEARS is that it is copyrighted material. Copies must be purchased directly from the Med-El Medical Electronics Co., and daily clinical use could become expensive.

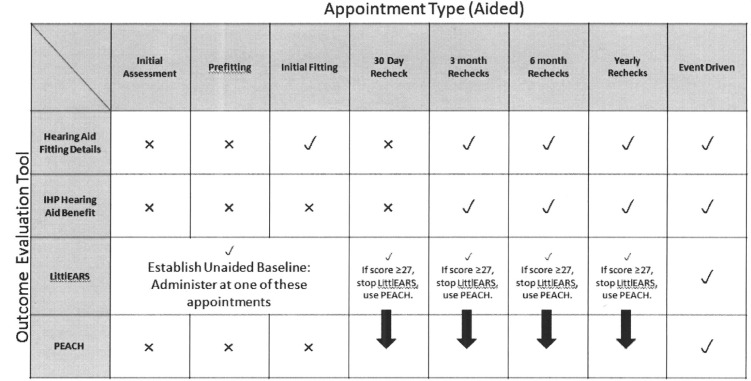

The Network of Pediatric Audiologists of Canada respondents reported that clinical implementation of the outcome evaluation tools would be facilitated primarily by support from administration/managers, colleagues at work, and UWO PedAMP experts. They wanted visual flowcharts to summarize when the outcome evaluation tools should be conducted, appropriate normative data to assist in interpretation of scores, and time to try the measures out independent of each other. The UWO PedAMP includes many flowchart-like tools to facilitate clinical implementation, including a chart that shows which measures should be conducted at which appointment. This outcome evaluation tool by appointment grid is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The Outcome Evaluation Tool by Appointment grid provides a visual for the pediatric audiologist to remind them which outcome evaluation measure to use at various appointments. This grid can be printed and posted in the clinic.

It has been our experience throughout the development of the Desired Sensation Level (DSL) method for hearing-aid selection and fitting that the translation of knowledge from the research laboratory to clinical practice is facilitated by hands-on training. Hands-on training was recommended as the top facilitator by the Network audiologists. Partially on the basis of these results, the developers of the UWO PedAMP could anticipate “up front” that there would be a large demand placed on the CAL researchers’ time for hands-on training. Therefore, we developed a training Digital Versatile Disk (DVD) that will accompany the UWO PedAMP manual. This DVD was developed based on the successful live training sessions that Dr. Bagatto provided to the Ontario Infant Hearing Program (OIHP) audiologists. It essentially duplicates the live training sessions. In addition, copies of appropriate materials such as the PEACH score sheet, clinical summary forms, and the appointment type by outcome evaluation tool administration grid are provided on the DVD for clinicians to access and print as needed. To respond to the requests for timely feedback from experts when a clinician has a question, the CAL researchers are working to add a page to the DSL website (www.dslio.com) where clinicians can look up frequently asked questions and/or pose a question for answer and obtain updated forms and new information relative to the UWO PedAMP as it evolves over time.

One of the interesting findings emerging from this study is that, regardless of the availability of resources, the ability for the pediatric audiologists to change practice if they choose to, the expertise and knowledge of the audiologists, the good leadership, and the culture and institutional support in the contexts in which they work, approximately 10% of the Network audiologists indicated that they would not likely implement the evaluation tools in their daily practice. These statistics underscore the importance of measures of perceived comparative value and of viewing knowledge translation as a dynamic, iterative, and collaborative process. We asked the audiologists to provide reasons if they selected not likely as their response. Overall, subjectively, it appears that relative advantage or utility/comparative value was a primary reason why they might not implement the outcome evaluation tools in daily practice. Relative advantage or comparative value relates to the new measure(s) that are part of the guideline being better than existing or alternative methods. For example, some of the members of the Network of Pediatric Audiologists of Canada indicated that they would not likely implement the measures in daily practice because

Much of the information requested would generally be covered by pediatric audiologists in their standard practice format, i.e., the audiologist should routinely be asking questions around hearing instrument use and auditory behavior and speech development. Formal assessment of auditory verbal and/or language acquisition should occur, however, there are support personnel/professionals who will, and do, do this on a routine basis . . . (auditory/verbal therapists and speech-language-pathologists). In general their observations and assessments will be as thorough as and/or more so than what would be accomplished and/or could be accomplished in the audiologist’s office. Consequently questionnaires like the PEACH or similar to it, may in fact be redundant in terms of the assessment and treatment process.

The questions/topics/ideas covered I already routinely cover with my patients so I do not see value in adding this tool. Also asking the same questions every time the same way does not necessarily uncover other issues that need to be addressed/worked on.

It is our hope by examining both the quantitative and qualitative information gathered in this study and implementing suggestions to alter the UWO PedAMP and address barriers and facilitators to use we have increased the number of Network of Pediatric Audiologists of Canada audiologists who will ”very likely” implement the UWO PedAMP in their daily practice.

This project has several limitations. Richer qualitative information might have been obtained using a face-to-face or telephone interview format. Pediatric audiology practice in Canada, for the most part, follows similar hearing assessment, device selection, and prescription and verification procedures throughout most provinces. Canada is the home of the National Centre for Audiology (NCA) at the University of Western Ontario (UWO) that houses the largest training program for audiologists in the country. Many of the Network audiologists were trained at UWO or at other Canadian universities with almost identical training programs for audiologists who will be working with infants and young children. Findings from this study may not generalize to other countries. Finally, use of the UWO PedAMP is being mandated for use by audiologists within the Ontario Infant Hearing Program (OIHP). Ontario-based audiologists who participated in this project knew that this outcomes battery would have to be implemented within their practice; therefore, this could have affected their ratings of the measures and their written input. An examination of results indicates that all of the audiologists, regardless of the fact some would be mandated to use the measures, wanted their knowledge, experience, perceptions, and beliefs heard and acknowledged as part of the UWO PedAMP development process. They knew and appreciated that they had an opportunity to tailor the UWO PedAMP for use in clinical practice.

Conclusion