Abstract

A self-fitting hearing aid has been proposed as a viable option to meet the need for rehabilitation in areas where audiology services are unreliable. A successful outcome with a self-fitting hearing aid pivots in part on the clarity of the instructions accompanying the device. The aims of this article are (a) to review the literature to determine features that should be incorporated into written health-care materials and factors to consider in the design process when developing written instructions for a target audience of older adults and (b) to apply this information to the development of a set of written instructions as the first step in self-fitting of a hearing aid, assembling four parts and inserting the aid into the ear. The method involved a literature review of published peer reviewed research. The literature revealed four steps in the development of written health-care materials: planning, design, assessment of suitability, and pilot testing. Best practice design principles for each step were applied in the development of instructions for how to assemble and insert a hearing aid. Separate booklets were developed for the left and right aids and the content of each consisted of simple line drawings accompanied by captions. The reading level was Grade 3.5 equivalent and the Flesch Reading Ease Score was 91.1 indicating that the materials were “very easy” to read. It is essential to follow best practice design principles when developing written health-care materials to motivate the reader, maximize comprehension, and increase the likelihood of successful application of the content.

Keywords: self-fitting hearing aid, written instructions, health literacy, patient education, older adults

Introduction

This article outlines the process involved in the design and development of written instructions for assembly of a self-fitting hearing aid (SFHA). A SFHA is an amplification device that users can program and fit to themselves without the need for a previous audiogram, access to a computer, or assistance from an audiologist. In the absence of an audiologist, the client, and/or significant other is required to assemble the device, fit, and program it using written instructions.

A concept for a SFHA was developed at the National Acoustic Laboratories (NAL) and a comprehensive overview of it is provided by Convery et al. (2011). The three main components of a SFHA are (a) the hearing aid body (part that sits behind the ear), (b) a dome (part that sits inside the ear), and (c) a tube (part that hangs over the ear and connects the dome to the hearing aid body). Adults’ ears vary in size, hence the domes and tubes come in different sizes and the correct size must be selected for a comfortable fit. Therefore, the first step of a SFHA is for the end user to select the best size dome and tube for him/her and to assemble the parts to the hearing aid body. The research team was interested to know if older adults with a hearing impairment were able to assemble the parts, insert the device in the ear, and switch on both left and right devices with assistance from a friend or family member (significant other), and using written instructions only. As such, the design, content, and suitability of the written instructions were pivotal to success.

To design effective written instructions, it is imperative to consider key characteristics of the target audience including age, race/ethnicity, and health literacy level. The target audience for the current instructions was older, community dwelling adults living in Australia. This is highly relevant as the prevalence of hearing loss is highest in older people aged 60 years and above, and hence the market for SFHAs is likely to be greatest in this population. Hearing loss occurs in approximately 40% of adults in their 60s, 60% of adults in their 70s, and 90% of adults in their 80s and above (Chia et al., 2007; Wilson et al., 1999). Overall, hearing levels decrease on an average of 1dB per year for adults aged above 60, depending on gender, age, and initial levels (Lee, Matthews, Dubno, & Mills, 2005). It is also likely that the market for such devices will be greatest in the developing world where the cost of hearing aids is prohibitive; however, designing and testing instructions for this population is beyond the scope of the current study.

A key consideration in developing instructions was the fact that a significant percentage of older adults have limited health literacy (Gausman Benson & Forman, 2002; Gazmararian et al., 1999). Health literacy refers to “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions” (Ratzan & Parker, 2000). The terms literacy and health literacy are often used interchangeably but have important distinctions. Literacy is more general and refers to the ability to read, write, and understand in one’s native language, whereas health literacy refers to these skills applied in the context of health-care (Mayer & Villaire, 2007). Research findings show that adults with limited health literacy have poorer health status, less health knowledge, higher health-care costs, higher utilization of health services, and are less likely to comply with self-management regimes for chronic health conditions (Baker et al., 2002; Baker, Parker, & Williams,1997; Gazmararian, Williams, Peel, & Baker, 2003; Howard, Gazmararian, & Parker, 2005; Williams, Baker, & Parker, 1998).

Paasche-Orlow, Parker, Gazmararian, Nielsen-Bohlman, and Rudd (2005) conducted a systematic review examining the prevalence of limited health literacy and found that participants’ age was significantly associated with the rate of low literacy. Studies with a mean age of above 50 years showed a prevalence of low literacy of 38%. The largest study of health literacy was conducted by the National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAALs) (Kutner, Greenberg, & Paulsen, 2006) and involved approximately 19,000 adult participants. It revealed that adults aged 65 years and above had lower average health literacy than adults in younger age groups. Twenty nine percent of adults aged >65 years, had “below basic” health literacy compared with approximately 10% in younger age groups, and only 3% had proficient health literacy. It has been postulated that lower health literacy levels in older adults may be associated with fewer years of education (Weiss, Reed, & Kligman, 1995) and/or age-related changes in cognitive performance (e.g., working memory) that can affect reading and comprehension abilities (Van der Linden et al., 1999).

A wealth of information is available on how to design written health-care materials suitable for people with limited health literacy. Early research in the area focused on improving readability by using short simple words and sentences (Wilson et al., 2010). More recently, researchers have highlighted the importance of attending to a myriad of other design elements, in addition to readability (Doak, Doak, Friedell, & Meade, 1998; Seligman et al., 2007). These include text cohesion, organization, layout, graphics, writing style, cultural factors, and the amount of information presented (Doak, Doak, & Root, 1996; Liu, Kemper, & Bovaird, 2009; Meade & Smith, 1991). In addition, it is important to consider cognitive factors such as demands on working memory (Wilson & Wolf, 2009). According to Wilson and Wolf (2009) “design elements that minimize the amount of working memory necessary to decode new information will allow individuals to siphon more resources toward comprehending the core messages that designers are attempting to convey” (p. 319).

Research suggests that well-designed written materials are preferred by all readers, regardless of their literacy level and that comprehension is significantly higher than for less easy-to-read materials (Ley, 1993; Paul, Redman, & Sanson-Fisher, 1997). For example, Davis et al. (1996) used a randomized trial methodology to compare reading time and comprehension of two vaccine information pamphlets with one designed to be easy-to-read. The easy-to-read pamphlet contained less words, instructional graphics and was written at a lower reading level compared with the other pamphlet. Mean reading time was significantly shorter and mean comprehension levels were significantly higher for the easy-to-read pamphlet for readers with both high and low health literacy levels. According to Davis et al. (1996) readers with good health literacy could comprehend the more complex pamphlet but prefer a simpler pamphlet, because “it is easier to understand and can be read in one fourth the time” (p. 808). Despite these findings, more than 300 research studies indicate that written health-care materials often far exceed the average reading ability of the target client group (Griffin, McKenna, & Tooth, 2006; Nielsen-Bohlman, Panzer, & Kindig, 2004; Sarma, Alpers, Prideaux, & Kroemer, 1995). For example, Friedman and Hoffman-Goetz (2006) conducted a systematic review on the readability of print and web-based cancer information. The mean reading grade level in the 16 studies ranged from Grade 6 to 14 despite the recommended reading level of Grade 3 to 6 (Davis et al., 1996; Doak et al., 1996; Meade, McKinney, & Barnas, 1994) for printed health-care material. This has broad implications because “information that is written above the reading level of patients is useless and contributes to loss of time and money” (Meade & Smith, 1991, p. 153).

In summary, success of a SFHA pivots, in part, on the design and content of the written instructions, because an audiologist will not be on hand to assist. It is important that the instructions are tailored to the target audience which is likely to consist of older adults, of whom approximately 30% are likely to have limited health literacy. Studies show that well-designed written materials result in higher information recall, comprehension and understanding for people with both high and low health literacy.

The aims of this study were to

Review the literature to determine features that should be incorporated into written health-care materials and factors to consider in the design process when developing written instructions for a target audience of older adults.

Apply this information to the development of a written instruction document for the SFHA, the purpose of which was to guide the hearing-impaired adult and a significant other through the process of assembling, inserting, and switching on the right and left aids. Henceforth, this subset of instructions relevant to the SFHA is referred to as the SFHA instructions.

Method

Relevant research articles were initially located by conducting searches of PsycINFO, Web of Science, Medline, and Scopus databases from 2000 to 2010, using the search term “health literacy.” Additional articles were found from the reference lists of retrieved articles. Both research studies and literature reviews were examined with emphasis placed on studies including experimental control group comparisons. In addition, information was sourced from a range of health literacy textbooks (Mayer & Villaire, 2004; Nielsen-Bohlman, Panzer, & Kindig, 2004; Schwartzberg, VanGeest, & Wang, 2005; Zarcadoolas, Pleasant, & Greer, 2006).

Results/Discussion

Overview

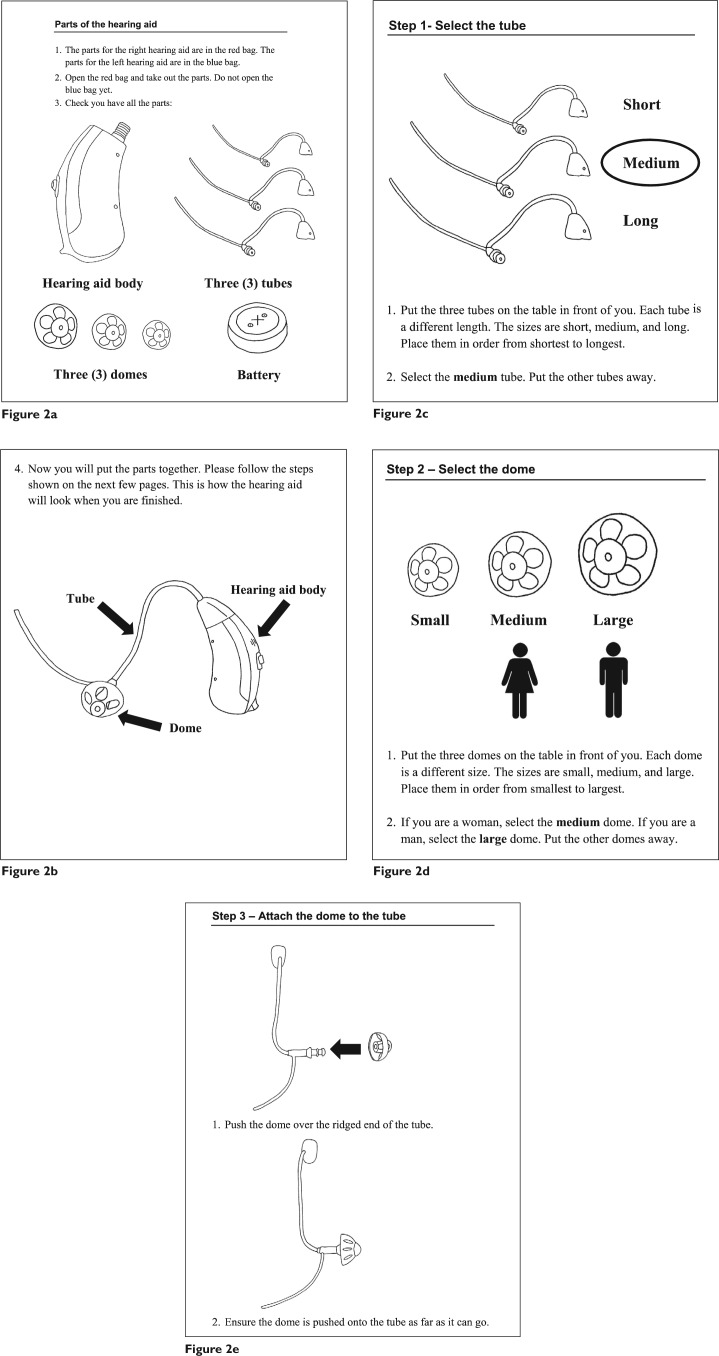

The review of the literature identified four steps in the development of written health-care materials (see Figure 1). These are planning, design, assessment of suitability, and pilot testing. This section provides information on each of these steps, including background theory and application to the SFHA instructions. Some recommendations are not incorporated into the instructions because they are more suited to longer text documents but are included in this article for completeness. Five pages from the SFHA instructions for the right ear are shown in Figure 2 and will be referred to throughout this article.

Figure 1.

Four steps in the development of written health-care materials

Figure 2.

Example pages taken from the SFHA instructions (continued on next page)

Planning

The first stage in the development process is to convene a working team of key stakeholders which may include health-care providers, topic experts, patients, and/or family members (Seligman et al., 2007). The initial goal for the team is to define the target audience and characteristics of it, including age, education level, race/ethnicity, health literacy, and topic knowledge (Bernier, 1993; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009; National Cancer Institute, 2003). This may be achieved through checking existing sources of information such as health statistics (National Cancer Institute, 2003) or engaging directly with a sample of the audience through interviews, focus groups, and/or surveys (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009; National Cancer Institute, 2003). Second, the team must identify the purpose and key objectives for the instructions (Bernier, 1993; National Cancer Institute, 2003; Seligman et al., 2007). Research findings indicate that it is best to limit the scope by focusing on two to three concepts only as this leads to enhanced information recall (Bernier, 1993; Seligman et al., 2007).

A multidisciplinary team was convened to design the SFHA instructions. Team members included a clinical audiologist, a speech pathologist, and research audiologists. The team communicated weekly by phone and/or in person during the planning and design phases.

The target audience was defined as older, community-dwelling adults with a hearing impairment, living in Australia. Research was conducted by the team to determine key characteristics of the target audience. Sources of information included research papers and textbooks on both ageing and health literacy. As outlined in the introduction, the main finding was that approximately 30% of older adults have limited health literacy. In addition, a substantial percentage of older adults have age related deterioration in visual function (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2005; Bergman & Sjostrand, 2002), visual-reading ability (Watson, 2009), processing speed (Salthouse, 1996), attention (Krauss Whitbourne, 2005), and memory (Park et al., 2002) which may impact on their ability to read and use instructions. Each participant was required to bring along a friend or family member to assist, but as the significant other could be of any age or background, key characteristics of the group were likely to be varied. Previous hearing aid experience was not a requirement for either the participant or the significant other, hence it was envisaged that hearing aid knowledge could range from none to quite extensive. The purpose and key objectives for the project, as determined by the team, are included in Table 1.

Table 1.

Details of the Self-Fitting Hearing Aid (SFHA) Instructions

| Purpose | To provide written instructions on how to assemble, insert in the ear, and turn on both the right and left SFHA. |

| Key objectives |

|

| Number of booklets | One for the right aid and one for the left aid |

| Pages in each booklet | 16 |

| Page size | A4—printed on two sides |

| Colors | Black text on white matte paper |

| Flesch-Kincaid Grade reading level | Grade Level 3.4 |

Note: Refer to Figure 2.

Design

There are five elements that need to be considered in the design of written materials: content, language, layout/typography, organization, and graphics. Five key recommendations for each element are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Recommendations for Designing Written Health Care Education Materials for Older Adults

|

|

|

|

|

Content

First, it is important to limit learning objectives and to avoid any information that might confuse or overwhelm the reader (Seligman et al., 2007), particularly as it is neither necessary nor advantageous to aim for attainment of high-level knowledge (Davis et al., 1996). According to Doak et al. (1996) one should ask, “What is the least I can include to give the reader the information and motivation needed to change behavior or perform the procedure?” (p. 76).

Second, research suggests that emphasis be placed on practical information that assists the reader to achieve desired behaviors rather than factual information. To do so, provide explicit “how to” information and clearly state the actions the reader needs to take (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009; Doak et al., 1998; National Cancer Institute, 2003; Seligman et al., 2007). In addition, emphasis on small practical steps is recommended to encourage and motivate the reader (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009).

Third, one should avoid negatively worded statements, particularly in health-care materials designed for older adults. Research conducted by Wilson and Park (2008) found that older adults have difficulty remembering negatively worded statements and are inclined to remember the opposite meaning of the statement. For example, “do not stop taking your antibiotic when you feel better could be remembered as stop taking your antibiotic when you feel better.” They argued that this is due to the fact that negatively worded statements place additional cognitive demands on the reader relative to positively worded statements, and hence older adults tend to forget the negations present in medical information and remember only the key words. This was found to be the case for older adults with both poor and good health literacy.

Fourth, it is beneficial to tailor information to the individual. Research conducted by Bull, Holt, Kreuter, Clark, and Scharff (2001) indicates that behavior change is more likely for those who receive tailored health-care material. In addition, tailored material is more likely to be read and shown to others, which is an important component of social support. There are a number of ways to tailor written health-care material and these can be achieved using computer generated programs. They include adding a person’s name to the cover (Doak et al., 1998), only printing information relevant to the individual (Bull et al., 2001), and targeting messages to the cultural group by using culturally appropriate images, concepts, and language (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009). Complimentary strategies include opening the document in the client’s presence and underlining or highlighting the most important information (Doak et al., 1998). One can also stratify the contents of a patient education booklet at different levels of complexity (Badarudeen & Sabharwal, 2008), so it is suitable for people with different interests, levels of health literacy, and/or at different stages along their rehabilitation journey. In summary, one needs to present information that makes sense to the client and is relevant and logical from their perspective. “They need to see how the advice fits into their current lifestyle, is achievable, and is worth their effort to implement it” (Doak et al.,1998, p. 153).

To streamline content for the SFHA, each participant received two SFHA instruction booklets: one for the right aid and one for the left aid. The rationale was to reduce the amount of information in each booklet and to make the instructions easier for the reader to follow. Each booklet was identical with exception of right/left information. In the SFHA instructions, the assembly of the aid was divided into small practical steps with the intent that the reader could experience small successes along the way, leading to an increase in confidence. The actions required to complete each step were explicitly stated and supported by clear graphics as shown in Figure 2. The majority of sentences were worded in the positive, and no factual or theoretical information was included such as technical data on the device. In this study, all participants received the same SFHA instructions; however, it is envisaged that future SFHA instructions will be tailored to groups or individuals. This may include printing the user’s name, showing an emblem of cultural significance on the cover or changing the language depending on the country and/or region.

Language

An important aspect of language is readability. This is an objective measurement of the reading skills necessary to understand a written text and is typically measured in terms of grade level (Badarudeen & Sabharwal, 2008). Readability formulae are used to assess reading level and are based on language variables such as sentence length, word length, and syllable counts (Doak et al., 1996; Liu, Kemper, & Bovaird, 2009; Vahabi & Ferris, 1995). The most commonly used formulae include the Flesch Reading Ease (Flesch, 1948), Flesch-Kincaid Formula (Kincaid, Fishburne, Rogers, & Chissom, 1975), Fog Index (Gunning, 1968), Fry Readability Graph (Fry, 1968), and the Simple Measure of Gobbledygook Index (SMOG; McLaughlin, 1969). The Flesch-Kincaid Grade is the most widely used readability formula (Albright et al., 1996) and can be accessed through the Microsoft Word Office package. It is a modified version of the Flesch Reading Ease Formula and is based on the average number of syllables per word and the average number of words per sentence (Badarudeen & Sabharwal, 2008).

Research findings show that readability formulae have high validity, satisfactory reliability, and are highly correlated (Ley & Florio, 1996; Meade & Smith, 1991). However, despite the fact that the formulae show high intercorrelations, they often produce different estimates of reading grade level for a piece of text. This is, in part, due to the fact that they are based on different comprehension levels. For example, the Flesch Reading Ease is based on a criterion of 75% comprehension whereas the Fog Index is based on 90% comprehension (Ley & Florio, 1996). For this reason, it is recommended that one assess the readability of a document using multiple formulae, because this will result in a more reliable estimate. One can then select to take either the score that represents the highest estimated reading grade level or the average score (Ley & Florio, 1996).

According to research, people of all literacy levels prefer simple written materials over complex materials and have less difficulty comprehending simple materials (Doak et al., 1996). However, there is mixed opinion regarding the optimal reading level for health care information. Recommendations range from third- or fourth-grade level (Davis et al., 1996) to fifth- or sixth-grade level (Doak et al., 1996; Meade et al., 1994). According to Boyd (1987), material should be written at two to four grade levels below the average reading grade level of the end user. This information cannot be ascertained by simply asking the end user about their highest level of education because comprehension may be 2 to 4 years lower than stated years of school (Doak et al., 1996).

A second important aspect of language is text cohesion. This refers to the use of explicit words, phrases, and sentences to guide the reader through the text and enhance comprehension by making connections between sentences, topics, and ideas (Liu, Kemper, & Bovaird, 2009). Liu et al. (2009) investigated how readability (Flesch Reading Ease) in conjunction with text cohesion affects the ability of older adults to comprehend common health texts. They found that all participants exhibited better comprehension when high readability (reading ease) was combined with high text cohesion. They surmised that increasing text cohesion may benefit older adults, because the repetition of similar words, phrases, and ideas may reduce processing demands. A second finding revealed that older adults with reduced working memories had more difficulty understanding text with high readability (reading ease) but low text cohesion. This suggests that increasing readability/reading ease through the use of shorter words and sentences can lead to poorer comprehension in older people with smaller working memories if it results in the omission of key information such as “causal and temporal connections among ideas” (p. 664).

There is consensus that one should write in active voice because it improves readability and is more likely to move the reader to action compared with the same message written in passive voice (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009; Doak et al., 1996; National Cancer Institute, 2003; Vahabi & Ferris, 1995). It is also recommended to use short words that are familiar to the reader (one to two syllables where possible) and short sentences (8 to 10 words). It is important to limit use of jargon, technical language, abbreviations, and unnecessary acronyms; to clearly define any new words; and to be consistent with word use (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009; Doak et al., 1996; National Cancer Institute, 2003).

According to Doak et al. (1996, 1998), certain types of words are difficult to understand, particularly for people with limited health literacy and include concept, category, and value judgment words. Concept words provide a general idea or abstract range of reference, such as “normal range.” Using this example, “keep your blood sugar in the normal range” is better written as “keep your blood sugar somewhere between 70 and 120.” Category words are used to classify a group of related entities. It is recommended that the exact term is used rather than the category term (e.g., use chicken rather than poultry). Value judgment words often describe amounts, such as “exercise regularly.” Such words can be interpreted in different ways by different people and therefore should be avoided.

The readability level of the SFHA instructions was measured using four different formulae: Flesch Reading Ease, Flesch-Kincaid Formula, Fog Index, and the Fry Readability Graph. The results are shown in Table 3. The readability grade level ranged from Grade 2.6 for the Flesh-Kincaid Formula to Grade 4.9 for the Fog Index. The average readability grade level was Grade 3.5 which is appropriate for older adults with limited health literacy. The Flesch Reading Ease Score was 91.1 indicating that the material was “very easy” to read.

Table 3.

SFHA Instructions Readability Grade Levels

| Readability formulae | Reading grade level or score |

|---|---|

| Flesch Reading Easea | (Score of 91.1 indicating “very easy” to read.) |

| Flesch-Kincaid Formula | 2.6 |

| Fog Index | 4.9 |

| Fry Readability Graph | 3.0 |

| Average reading grade level | 3.5 |

The formula does not estimate reading grade level but provides a “reading ease” score ranging from 0 (very difficult to read) to 100 (very easy to read).

The satisfactory readability grade level for the SFHA instructions was achieved, in part, through high usage of short sentences and words. The mean number of words per sentence was 8.9 and the mean number of characters per word was 3.8. The readability level was not achieved at the expense of text cohesion. Each section was built on the previous section in a sequential manner and included the repetition of core words, terminology, and concepts. Almost all sentences (97%) were written in the active voice, and jargon, abbreviations, and/or acronyms were not used. It was necessary to include technical language to describe the parts of the hearing device. Simple technical terms were selected such as “tube” to describe hearing aid tubing and “dome” to describe the dome tips. Each term was introduced to the reader through the use of a line drawing, clearly depicting it (Figures 2a and 2b). It was decided to use this approach rather than a written definition which could prove difficult for a person unfamiliar with hearing devices to interpret.

Layout/typography

Recommendations for layout and typography for written health care information are displayed in Table 4. As per these recommendations, a serif font (Times New Roman) in 16 point is used in the SFHA instructions. The headings are in a sans serif font (Arial) to stand out from the body of the document and bold type rather than italics or underlining is used to emphasize important words (refer to Figure 2). There is limited text and graphics on each page and the text is printed in black on a white matte background.

Table 4.

Recommendations for Typography and Layout of Written Health Care Education Materials

| Recommendation | Rationale | Reference(s) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typography |

|

A percentage of older readers will have visual problems that cannot be corrected by glasses such as Macular Degeneration. | |

|

Serif font makes individual letters more distinctive and easier for the brain to recognise. | ||

| Use upper and lower case letters. | Words written in all capital letters are difficult to read as the letters have less distinguishing features (e.g., differences in size). | ||

|

Italics and underlining are difficult to read. | ||

| Layout |

|

White space avoids the appearance of solid text which can be intimidating to the reader. It also allows for more contrast and facilitates the ease of reading. | |

| Use dark letters on a light background. | Older readers have difficultly detecting differences in low contrast colors (Schieber, 2006) | ||

| Use right edge “ragged” or unjustified margins. | This makes the text easier to read. | ||

| Break up text with bullet points, where appropriate. | This results in more white space on the page. | ||

| Use a box, larger font, or indent to highlight the most important information. | Poor readers have more difficulty finding the most important information on a page. Their eyes tend to wander about the page and skip prinicpal features whilst focusing on less important detail. | Doak et al. (1996) | |

| Do not use glossaries or refer the reader to other pages for more information. | Readers with limited health literacy have difficulty with cross referencing text. | Doak et al. (1996) |

Organization

The first paragraph should communicate the benefits that the reader desires because it is one of the most often read parts of a written document and should entice the person to continue reading (Buxton, 1999). In addition, the reader has better recall for information contained in the first part of a document, hence the most important and/or useful content should be placed near the begining (Boyd, 1987; Doak et al., 1996). The remaining content should be sequenced in the order the reader will use it (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009; National Cancer Institute, 2003).

It is recommended that information is chunked under simple headings and subheadings so readers are provided with the context and can also easily find the answers to their questions (Boyd, 1987; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009; Doak et al., 1996; National Cancer Institute, 2003). According to Buxton (1999), many people only look at the title, headings, and highlighted information; therefore, one should structure information so key points can be obtained by only reading these elements. It is also good to present one complete idea on one page or two facing pages because if a reader has to turn a page in the middle of a message, they may forget the first part of it (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009).

Paragraphs should be short and limited to one subject or idea (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009; Doak et al., 1996; Vahabi & Ferris, 1995). When writing a sentence or paragraph, it is important to provide the context before presenting new information because this provides a framework for the new information to fit, before it arrives. If context is given last, the reader must carry all the information along in their short-term memory (Doak et al., 1996). Lastly, it is useful to include a summary of the main points either at the end of the document or at the end of each section, because this helps the reader to remember the key points (Doak et al., 1996).

The first sentence in the SFHA instructions clearly outlines the purpose of the material: “This booklet shows you how to put the parts of your hearing aid together and turn it on.” The assembly of the device is then described in discrete steps. Each step is presented under a simple heading which also provides the context (e.g., “Step 1—Select the tube”). The material is organized so key information can be obtained by just reading the heading and scanning the graphic (e.g., “Step 3—Attach the dome to the tube”).

Graphics

Houts, Doak, Doak, and Loscalzo (2006) conducted a comprehensive literature review on the role of graphics in written health-care materials. The majority of studies included in the review used an experimental control group design with random assignment to each group.

The review found that adding pictures to written health materials can substantially increase patient attention, comprehension, recall, and adherence and that this was particularly true for people with low health literacy. In addition, the research suggested that “pictures can help low literacy people understand relationships, provided that they understand the elements being related” (Houts et al., 2006, p. 188). On the basis of the literature review and their experience working extensively with graphics in health education, Houts et al. (2006) recommend the use of simple line drawings accompanied by simple text captions. Although photographs are good for capturing attention (e.g., on the cover of a brochure), line drawings are better because there are less distracting elements. It is important that health professionals, in partnership with end users, design the drawings rather than artists. Houts et al. (2006) also suggest the use of prompts within the picture (e.g., labels or arrows) to help explain the intended meaning. Lastly, it is important to ensure that the graphics support key points in the text.

In contrast to the findings by Houts et al. (2006), a recent study found that one cannot assume that illustrations will increase older adults’ comprehension of health information (Liu, Kemper, & McDowd, 2009). The research used eye-tracking techniques to compare how young and older adults read and comprehend texts with and without illustrations. It revealed that older adults may not benefit from illustrations that often accompany health-related texts because they may have difficulty integrating the illustrations with the written text information. The difficulties experienced “not only increased total reading times but also affected fixation patterns, and responses to the comprehension tests” (Liu et al., 2009, p. 287). However, the study had a number of limitations. It used abstract concepts such as a garden hose analogy to explain the relationship between narrowed blood vessels and high blood pressure; eye tracking could not be performed for 7 out of the 26 older adults; white font was used on a dark background to record eye movements but this is difficult for older people to read, and all the participants were well educated and obtained high scores on vocabulary and working memory tests.

A decision was made to include graphics in the SFHA instructions because the majority of studies on this topic suggest that older adults do benefit from illustrations in written health-care materials. High quality photos were taken to illustrate each step and these were converted to simple but realistic line drawings. The team intended using a computer program to convert the photos to line drawings, but this approach had to be abandoned because the resultant drawings did not have sufficient contrast. The final technique used involved blowing up each photo, placing it face down on a light box, and using a black marker to trace the contours. The line drawings were then scanned and inserted in the SFHA instructions. The graphics were large and each was accompanied by a simple text caption. Research shows that the reader must understand each element in a graphic to interpret it correctly. To achieve this, the separate elements which include the hearing aid body, tubes, domes, and battery were introduced to the reader near the beginning of the SFHA instructions. Each was named and illustrated (see Figure 2a and 2b). The reader was then shown what the device would look like when the parts were correctly assembled (see Figure 2b). Prompts, particularly large, black arrows, were often used in the graphics to draw attention to important elements and/or actions. For example, in Figure 2e, a large arrow is used to show where and how the dome fits onto the tube. The graphics were designed in such a manner that they could stand alone without the need for written text, if necessary.

Rating Scales

Rating scales can be used to assess the content and design of written materials. Three rating scales have been developed that are suitable for use with written health care instruction materials: (a)TEMPtEd (Clayton, 2009), (b)Suitability Assessment of Materials (SAM; Doak et al., 1996), and (c) Bernier Instructional Design Scale (BIDS; Bernier, 1996). The SAM was deemed the most appropriate to assess the SFHA instructions, because it has been widely used in research examining the suitability of written health-care materials (e.g., Weintraub, Maliski, Fink, Choe, & Litwin, 2004).

The SAM has 22 items grouped under six factors (content, literacy demand, graphics, layout and typography, learning stimulation/motivation, and cultural appropriateness) and is used to pinpoint specific deficiencies in an instrument. Each item is rated on an ordinal scale that includes the anchor points of superior, adequate, not suitable, and not applicable. Scores for the items are summed and the total is converted to a percentage with scores of 70% to 100% indicating that the material is superior, 40% to 69% indicating that the material is adequate, and 0% to 39% indicating that the material is not suitable (Doak et al., 1996).

Two qualified audiologists assessed the SFHA instructions using the SAM. They initially assessed them independently to obtain suitability scores and then met to review any discrepancies and negotiate 100% concordance in the ratings. The final SAM rating was 88%, hence qualifying the SFHA instructions as “superior material.” The SAM revealed a number of limitations which will be addressed in future editions of the booklet. First, a summary was not included but it is questionable whether this is necessary for this first step of the instruction material. However, a summary section would be beneficial when the final product has been developed and the entire SFHA instructions have been designed. Second, the cover was rated as only adequate. A superior rating is obtained if “the cover graphic is (a) friendly, (b) attracts attention, (c) clearly portrays the purpose of the material to the intended audience.” The cover of the booklet displayed the words “Hearing Aid Instructions—Left (or Right)” and showed the SFHA in the form of a black-and-white line drawing. Although the purpose was clear, it was not particularly friendly and was unlikely to attract attention. The booklet also failed to use any cultural images and was limited to instruction information only. It could be improved with the injection of color on the cover and/or a photo of an older adult assembling or wearing the aid.

Pilot Testing and Revision

There are two methods to assess written health care material: (a) evaluation of the material with a sample target audience and (b) use of a validated instrument such as the SAM. Experts strongly recommend the use of both. The latter should only be used in isolation if one lacks time and resources (Doak et al., 1996, Raynor, 1998; Vahabi & Ferris, 1995). The goals of pilot testing are to ensure readers understand the material (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009; Doak et al., 1996; Vahabi & Ferris, 1995) and to obtain feedback on the overall “product” as well as specific features such as content, layout, format, and graphics (Vahabi & Ferris, 1995). Based on this feedback, revisions can be made so that the material is more suitable and attractive to the end user.

The SFHA instructions were not formally assessed using a target audience due to delays and time restrictions. However, they were tested in an informal manner with a small number of nonclinicians including younger and older people. All were presented with the SFHA instructions and asked to follow the directions using the actual devices. No one experienced problems with either the task or the instruction materials and no suggestions were made for improvements. The fact that a target sample audience was not used to assess the instructions is a limitation of this study.

Conclusion

This article documented the process of developing written instructions on how to assemble a SFHA and insert it into the ear. The target audience for the SFHA instructions was older, community dwelling adults with a hearing impairment. Research indicates that approximately 30% of older adults have limited health literacy. In addition, a substantial number have age-related deterioration in visual and/or cognitive function which may impact on their ability to read and use instructions. Hence, it was deemed important to follow best practice design principles in developing the SFHA instructions. Research suggests that well-designed written materials are preferred by all readers and result in improved information recall and comprehension, regardless of literacy level.

Four steps were followed in the development process for the SFHA instructions: planning, design, assessment of suitability, and pilot testing. Five key elements were considered in the design phase, including content, language, layout/typography, organization, and graphics. Separate booklets were developed for the left and right aids and the content of each consisted of simple line drawings accompanied by captions. The text was 16 point, Times New Roman, black font printed on A4-size white matte paper. The information was presented in small practical steps and the readability grade level was 3.5 which is appropriate for older adults. The SFHA instructions were assessed using the SAM rating scale and qualified as “superior material.” They were also pilot tested on a small sample of nonclinicians, none of whom experienced problems with the quality and/or content of the instructions. In summary, it is recommended that health professionals follow best practice design principles when developing written health-care materials to maximize the readers’ interest, comprehension, and information recall.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Gitte Keiser for her input, guidance, and support in the development of the instructions. They also extend their sincere thanks to Elizabeth Convery for her time and expertise in creating the excellent graphics which were pivotal to the success of the SFHA instructions.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Authors’ Note: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The hearing aids used in this study were provided by Siemens Audiologische Technik, Erlangen, Germany. This project was financially supported by the HEARing CRC established and supported under the Australian Government’s Cooperative Research Centres Program.

References

- Albright J., de Guzman C., Acebo P., Paiva D., Faulkner M., Swanson J. (1996). Readability of patient education materials: implications for clinical practice. Applied Nursing Research, 9, 139-143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2005). Vision problems among older Australians. Retrieved from http://www.aihw.gov.au/publications/aus/bulletin27/bulletin27.pdf

- Badarudeen S., Sabharwal S. (2008). Readability of patient education materials from the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons and Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America web sites. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, 90, 199-204. 10.2106/jbjs.g.00347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker D. W., Gazmararian J. A., Williams M. V., Scott T., Parker R. M., Green D., . . . Peel J. (2002). Functional health literacy and the risk of hospital admission among Medicare managed care enrollees. American Journal of Public Health, 92, 1278-1283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker D. W., Parker R. M., Williams M. V. (1997). The relationship of patient reading ability to self-reported health and use of health services. American Journal of Public Health, 87, 1027-1030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman B., Sjostrand J. (2002). A longitudinal study of visual acuity and visual rehabilitation needs in urban Swedish population followed form the ages of 70 to 97 years of age. Acta Ophthalmologica Scandanavica, 80, 598-607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernier M. J. (1993). Developing and evaluating printed education materials: A prescriptive model for quality. Orthopaedic Nursing, 12(6), 39-46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernier M. J. (1996). Establishing the psychometric properties of a scale for evaluating quality in printed education materials. Patient Education and Counseling, 29, 283-299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd M. (1987). A guide to writing effective patient education materials. Nursing Management, 18, 56-57 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull F. C., Holt C. L., Kreuter M. W., Clark E. M., Scharff D. (2001). Understanding the effects of printed health education materials: Which features lead to which outcomes? Journal of Health Communication, 6, 265-279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buxton T. (1999). Effective ways to improve health education materials. Journal of Health Education, 30(1), 47-50 [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2009). Simply put: A guide for creating easy-to-understand materials (3rd ed.). Retrieved from www.cdc.gov/healthmarketing/pdf/Simply_Put_082010.pdf

- Chia E. M., Wang J. J., Rochtchina E., Cumming R. R., Newall P., Mitchell P. (2007). Hearing impairment and health-related quality of life: The Blue Mountains Hearing Study. Ear and Hearing, 28, 187-195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton L. H. (2009). TEMPtEd: Development and psychometric properties of a tool to evaluate material used in patient education. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 65, 2229-2238. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05049.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Convery E., Keidser G., Dillon H., Hartley L. (2011). A self-fitting hearing aid: need and concept. Trends in Amplification, 15(4), 157-166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis T. C., Bocchini J. A., Fredrickson D., Arnold C., Mayeaux E. J., Murphy P. W., . . . Paterson M. (1996). Parent comprehension of polio vaccine information pamphlets. Pediatrics, 97, 804-810 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doak C. C., Doak L. G., Friedell G. H., Meade C. D. (1998). Improving comprehension for cancer patients with low literacy skills: Strategies for clinicians. CA: A Cancer Journal For Clinicians, 48(3), 151-162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doak C. C., Doak L. G., Root J. (1996). Teaching patients with low literacy levels (2nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: J. B. Lippincott [Google Scholar]

- Flesch R. (1948). A new readability yardstick. Journal of Applied Psychology, 32, 221-233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman D. B., Hoffman-Goetz L. (2006). A systematic review of readability and comprehension instruments used for print and web-based cancer information. Health Education & Behavior, 33, 352-373. 10.1177/1090198105277329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry E. (1968). A readability formula that saves time. Journal of Reading, 11, 513-516, 575-578 [Google Scholar]

- Gausman Benson J., Forman W. B. (2002). Comprehension of written health care information in an affluent geriatric retirement community: Use of the test of functional health literacy. Gerontology, 48(2), 93-97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazmararian J. A., Baker D. W., Williams M. V., Parker R. M., Scott T. L., Green D. C., . . . Koplan J. P. (1999). Health literacy among medicare enrollees in a managed care organization. Journal of American Medical Association, 281, 545-551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazmararian J. A., Williams M. V., Peel J., Baker D. W. (2003). Health literacy and knowledge of chronic disease. Patient Education and Counseling, 51, 267-275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin J., McKenna K., Tooth L. (2006). Discrepancy between older clients’ ability to read and comprehend and the reading level of written education materials used by occupational therapists. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 60(1), 70-80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunning R. (1968). The technique of clear writing. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill [Google Scholar]

- Houts P. S., Doak C. C., Doak L. G., Loscalzo M. J. (2006). The role of pictures in improving health communication: a review of research on attention, comprehension, recall, and adherence. Patient Education and Counseling, 61, 173-190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard D. H., Gazmararian J., Parker R. M. (2005). The impact of low health literacy on the medical costs of Medicare managed care enrollees. American Journal of Medicine, 118, 371-377. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kincaid J. P., Fishburne R. P., Rogers R. L., Chissom B. S. (1975). Deviation of a new readability formula for navy enlisted personnel. Millington, TN: Navy Research Branch [Google Scholar]

- Krauss Whitbourne S. (2005). Adult development & ageing (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley [Google Scholar]

- Kutner M., Greenberg E. Y. J., Paulsen C. (2006, September). The health literacy of America’s adults: Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NCES 2006483). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, US Department of Education [Google Scholar]

- Lee F., Matthews L. J., Dubno J. R., Mills J. H. (2005). Longitudinal study of pure-tone thresholds in older persons. Ear and Hearing, 26(1), 1-11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley P. (Ed.). (1993). Communicating with patients: Improving communication, satisfaction and compliance. London, UK: Chapman & Hall [Google Scholar]

- Ley P., Florio T. (1996). The use of readability formulas in health care. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 1(1), 7-28 [Google Scholar]

- Liu C. J., Kemper S., Bovaird J. A. (2009). Comprehension of health-related written materials by older adults. Educational Gerontology, 35, 653-668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C. J., Kemper S., McDowd J. (2009). The use of illustration to improve older adults’ comprehension of health-related information: Is it helpful? Patient Education and Counseling, 76, 283-288. 10.1016/j.pec.2009.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer G. G., Villaire M. (2007). Health literacy in primary care: A clinician’s guide. New York, NY: Springer [Google Scholar]

- Mayer G. G., Villaire M. (2004). Low health literacy and its effects on patient care. Journal of Nursing Administration, 34, 440-442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin G. H. (1969). SMOG grading: A new readibility formula. Journal of Reading, 12, 639-646 [Google Scholar]

- Meade C. D., McKinney P., Barnas G. P. (1994). Educating patients with limited literacy skills: The effectiveness of printed and videotaped materials about colon cancer. American Journal of Public Health, 84(1), 119-121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meade C. D., Smith C. F. (1991). Readability formulas: Cautions and criteria. Patient Education and Counseling, 17, 153-158 [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. (2003). Clear and simple: Developing effective print materials for low-literate readers. Retrieved from http://www.cancer.gov/cancerinformation/clearandsimple

- Nielsen-Bohlman L., Panzer A. M., Kindig D. A. (Eds.). (2004). Health literacy: A prescription to end confusion. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paasche-Orlow M. K., Parker R. M., Gazmararian J. A., Nielsen-Bohlman L. T., Rudd R. R. (2005). The prevalence of limited health literacy. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 20, 175-184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park D. C., Lautenschlager G., Hedden T., Davidson N. S., Smith A. D., Smith P. K. (2002). Models of visuospatial and verbal memory across the lifespan. Psychology and Aging, 17, 299-320 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul C. l., Redman S., Sanson-Fisher R. W. (1997). The development of a checklist of content and design characteristics for printed health education materials. Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 7, 153-159 [Google Scholar]

- Ratzan S. C., Parker R. M. (2000). Introduction. In Selden C. R., Zorn M., Ratzan S. C., Parker R. M. (Eds.), National library of medicine current bibliographies in medicine: Health literacy (NLM CBM 2000-1). Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health [Google Scholar]

- Raynor D. K. (1998). The influence of written information on patient knowledge and adherence to treatment. In Myers L., Midence K. (Eds.), Adherence to treatment in medical conditions (pp. 83-111). London, UK: Harwood Academic [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse T. A. (1996). The processing-speed theory of adult age differences in cognition. Psychological Review, 103, 403-428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarma M., Alpers J. H., Prideaux D. J., Kroemer D. J. (1995). The comprehensibility of Australian educational literature for patients with asthma. Medical Journal of Australia, 162, 360-363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schieber F. (2006). Vision and aging. In Birren J. E., Schaie K. W. (Eds.), Handbook of the psychology of aging (pp. 129-162). Boston, MA: Elsevier Academic Press [Google Scholar]

- Schwartzberg J. G., VanGeest J. B., Wang C. C. (Eds.). (2005). Understanding health literacy: Implications for medicine and public health. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association [Google Scholar]

- Seligman H. K., Wallace A. S., DeWalt D. A., Schillinger D., Arnold C. L., Shilliday B. B., . . . Davis T. C. (2007). Facilitating behavior change with low-literacy patient education materials. American Journal of Health Behavior, 31(Suppl. 1), S69-S78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vahabi M., Ferris L. (1995). Improving written patient education materials: A review of the evidence. Health Education Journal, 54, 99-106 [Google Scholar]

- Van der Linden M., Hupet M., Feyereisen P., Schelstraete M. A., Bestgen Y., Bruyer R., . . . Seron X. (1999). Cognitive mediators of age-related differences in language comprehension and verbal memory performance. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition, 6, 32-55 [Google Scholar]

- Watson G. (2009). Assessment and rehabilitation of older adults with low vision. In Halter J., Ouslander J., Tinetti M., Studenski S., High K., Asthana S., Hazzard W. (Eds.), Hazzard’s geriatric medicine & gerontology (pp. 511-525). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Medical [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub D., Maliski S., Fink A., Choe S., Litwin M. (2004). Suitability of prostate cancer education materials: Applying a standardized assessment tool to currently available materials. Patient Education and Counseling, 55, 275-280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss B. D., Reed R. L., Kligman E. W. (1995). Literacy skills and communication methods of low-income older persons. Patient Education and Counseling, 25, 109-119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams M. V., Baker D. W., Parker R. M. (1998). Relationship of functional health literacy to patients’ knowledge of their chronic disease: A study of patients with hypertension and diabetes. Archives of Internal Medicine, 158, 166-172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson D. H., Walsh P. G., Sanchez L., Davis A. C., Taylor A. W., Tucker G. (1999). The epidemiology of hearing impairement in an Australian adult population. International Journal of Epidemiology, 28, 247-252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson E. A. H., Park D. C. (2008). A case for clarity in the writing of health statements. Patient Education and Counseling, 72, 330-335. 10.1016/j.pec.2008.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson E. A. H., Wolf M. S. (2009). Working memory and the design of health materials: A cognitive factors perspective. Patient Education and Counseling, 74, 318-322. 10.1016/j.pec.2008.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson E. A. H., Wolf M. S., Curtis L. M., Clayman M. L., Cameron K. A., Vom Eigen K., Makoul G. (2010). Literacy, cognitive ability, and the retention of health-related information about colorectal cancer screening. Journal of Health Communication, 15, 116-125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarcadoolas C., Pleasant A. F., Greer D. S. (Eds.). (2006). Advancing health literacy: A framework for understanding and action. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley [Google Scholar]