Abstract

Modern digital hearing aids have provided improved fidelity over those of earlier decades for speech. The same however cannot be said for music. Most modern hearing aids have a limitation of their “front end,” which comprises the analog-to-digital (A/D) converter. For a number of reasons, the spectral nature of music as an input to a hearing aid is beyond the optimal operating conditions of the “front end” components. Amplified music tends to be of rather poor fidelity. Once the music signal is distorted, no amount of software manipulation that occurs later in the circuitry can improve things. The solution is not a software issue. Some characteristics of music that make it difficult to be transduced without significant distortion include an increased sound level relative to that of speech, and the crest factor- the difference in dB between the instantaneous peak of a signal and its RMS value. Clinical strategies and technical innovations have helped to improve the fidelity of amplified music and these include a reduction of the level of the input that is presented to the A/D converter.

Keywords: music, hearing aids, distortion

Introduction

The subject area of music, as an input to a hearing aid, is relatively new. Understandably, hearing aid design engineers and researchers have long been interested in optimizing a hearing aid response and technology for speech as an input. Speech and music have many similarities; however, there are some important differences that have direct implications on how a hearing aid should be designed (rather than simply programmed) for music.

Similarities and Differences Between Speech and Music

The Low-Frequency Limit

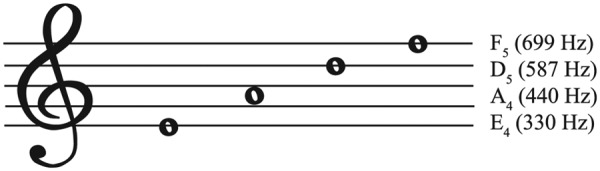

Both speech and music occupy similar, albeit slightly different frequency ranges. The lowest frequency element of speech is the fundamental frequency, which for a male voice is on the order of 100-125 Hz. (Johnson, 2003). In the human vocal tract, the vibration of the vocal cords for voiced sounds defines the fundamental frequency and its higher-frequency harmonic content and this limits the low-frequency end of the vocal output. There is simply no speech energy below the frequency of the fundamental. In contrast, musical instruments can generate significantly lower frequency with fundamental energy on the order of 40-50 Hz for bass instruments. Figure 1 shows a treble clef showing several musical notes and the frequency of their fundamentals. Middle C (just below the treble clef) is 262 Hz, and a typical male’s fundamental frequency is an octave below that (approximately 125 Hz).

Figure 1.

A treble clef showing several musical notes and their fundamental frequencies

However music, like speech, is slightly more complicated than just a rendition of any frequency components available or audible. In turns out that in music, like speech, it is not the fundamental frequency that defines the “pitch” of the note but the difference between any two successive harmonics. This is called the missing fundamental and explains why one only needs to hear the higher-frequency harmonics to define the pitch, which in some cases is below the bandwidth of the transmitter.

In the case of a telephone for example, the bandwidth is typically between 340 and 3400 Hz. A fundamental frequency of 125 Hz which is typical of a male’s voice is below the transmitting frequency response of the telephone, yet we can identify the voice as male. It is the difference between two adjacent harmonics, where the harmonics are within the bandpass of a transmitting device, that is important. In the human vocal tract, the vocal cords function as a one half wavelength resonator with the result of integer multiple harmonics being generated. Harmonics of 250 Hz, 375 Hz, 500 Hz, 625 Hz, and so on are generated by the 125 Hz fundamental and it is these harmonics that are within the bandpass of the telephone that are audible, namely, 375 Hz and higher. The difference between any two adjacent harmonics is exactly 125 Hz and this is what our brains replace.

The take-home message about the lower end of the frequency response of a hearing aid for any stimulus is that the harmonic structure is more important than the lowest frequency component or fundamental. Extending the amplified frequency response, especially in a noisy environment, down to 125 Hz for a male voice is simply not necessary. The same is true of music. Large, low-frequency emphasis instruments, such as the bass and cello, do generate significant energy in the lower-frequency region, but it is typically the mid- and higher-frequency harmonic structure that define its quality.

Despite the presence of some low-frequency elements in music, because of noise reduction circuits in hearing aids that frequently cannot be disabled, amplified music needs to be high-pass-filtered above 100 Hz in order to not confuse the hearing aid into rejecting an important signal. This may not be required in the future, but is certainly the case with current technology.

The High-Frequency Limit

In contrast to the above discussion, both speech and music have similar higher-frequency limits in their spectra. Speech of all languages has higher-frequency sibilants (“s”), affricates (“ch”), and fricatives (“th”) that have significant energy above 10,000 Hz. The same is true of musical instruments although the harmonic structure of bass instruments and some stringed instruments may have minimal high-frequency harmonic energy, especially above their bridge resonance.

The main restriction as discussed by Moore et al. (Moore, Fullgrabe, & Stone, 2011) and Ricketts et al. (Ricketts, Dittberner, & Johnson, 2008) is the degree and slope of the audiometric configuration and not the music per se. In general, the more severe the hearing loss and/or the greater its audiometric slope, the more limited will be the higher-frequency amplification that can be applied with minimal distortion.

Spectral Intensities

A major difference between speech and music lies in their intensities. The most intense elements of average conversational speech are on the order of 85 dB SPL. This usually is related to the low back vowel [a] as in “father” and is common to all human languages. There is minimal damping of the vocal tract with this vowel and subsequently its output at a relative maximum. In contrast with music, even quiet music has energy that is in excess of 80 dB SPL with prolonged levels in excess of 100 dB SPL in many forms of music. Table 1 is from Chasin (2006) and shows the sound level of some musical instruments measured on the horizontal plane from a distance of 3 meters. Higher levels would be measured if the assessment was measured at a different location, such as the violin player’s left ear.

Table 1.

Sound Levels of Some Musical Instruments Measured on the Horizontal Plane From a Distance of 3 Meters

| Musical instrument | dBA ranges measured from 3 meters |

|---|---|

| Cello | 80-104 |

| Clarinet | 68-82 |

| Flute | 92-105 |

| Trombone | 90-106 |

| Violin | 80-90 |

| Violin (near left ear) | 85-105 |

| Trumpet | 88-108 |

Note: The table shows that higher levels would be measured if the assessment was measured at a different location, such as the violin player’s left ear.

Source: Adapted from Chasin (2006); courtesy of Hearing Review, used with permission.

Crest Factors

Crest factors are used in every clinical audiology setting whenever a hearing aid is assessed in a test box (according to ANSI S3.22-2003; American National Standards Institute [ANSI], 2003). Initially, the hearing aid is set to full on volume and the OSPL90 (output sound pressure level with 90 dB SPL input) is measured. Depending on the compression characteristics of the hearing aid, the volume control is then reduced to the reference test gain for testing of the frequency response and some other measures. The reference test gain is given as the OSPL90-77 dB. This 77 dB figure is derived from 65 dB SPL (average conversational level of speech at 1 meter) plus 12 dB. The 12 dB figure is the crest factor for speech using a 125-msec analysis window. The crest factor is the difference in decibels between the instantaneous peak of a signal and its average (or root mean square [RMS]) value. For speech signals of all languages the crest factor is given as 12 dB.

The human vocal tract is a highly damped structure with soft buccal walls, a narrow opening to a highly damped nasal cavity, a highly damped tongue and soft palate, and highly damped nostrils and lips (Johnson, 2003). The difference of 12 dB between the instantaneous peak and its RMS value is a reflection of its highly damped structure. In contrast, a horn or a violin has less overall damping so its instantaneous peaks are much higher than the RMS of the generated sound—its crest factor is on the order of 18 to 20 dB. Adapted from Chasin (2012a), Table 2 shows some typical crest factors for speech and music using a 125-msec analyzing window.

Table 2.

Typical Crest Factors for Speech and Music Using a 125-msec Analyzing Window

| Stimulus | Peak amplitude-total RMS power | Crest factor |

|---|---|---|

| Speech 1 | –0.92-21.97 | 21.05 |

| Speech 2 | –5.53-17.99 | 12.46 |

| Speech 3 | –3.65-17.6 | 13.95 |

| Music 1 | –8.62-19.35 | 10.73 |

| Music 2 | –5.0-15.28 | 10.28 |

| Music 3 | –0.98-22.65 | 21.67 |

| Music 4 | –2.45-21.88 | 19.43 |

Note: The table shows some typical crest factors for speech and music using a 125-msec analyzing window.

Source: Adapted from Chasin (2012a), courtesy of Audiology Practices. Reprinted with permission of the Academy of Doctors of Audiology.

Taking the values of Table 1 and Table 2 together (Average values + 18 dB crest factor), it is apparent that a musical input to a hearing aid is typically in excess of 100 dB SPL.

What can “music and hearing aids,” teach us about “speech and hearing aids”?

Traditional studies of crest factors of speech and hearing aids utilize a 125-msec analyzing window (Cox, Mateisch, & Moore, 1988; Sivian & White, 1933). This value of 125 msec was historically chosen since it is close to the temporal resolution of the human auditory system. However, when it comes to hearing aids we should be examining the input to the hearing aid rather than the output to the human auditory system. Hearing aid components are not limited to a 125-msec resolution and as such different limiting time constants should be used. Table 3 (Chasin, 2012b) shows the crest factor of speech (from Sample 2 in Table 2) but with different analyzing windows. For shorter windows the instantaneous peaks are greater with higher calculated crest factors. If we are looking at the input to a hearing aid, the crest factor of even speech is greater than 12 dB. The resulting speech signal, despite only having a maximum level of 85 dB SPL for the average spoken level of the vowel [a], when the crest factor is taken into consideration, the instantaneous peaks of speech can be in excess of 100 dB. When we examine a hard of hearing person’s own speech levels at the location of their own microphone, the input to the hearing aid can be even greater.

Table 3.

Crest Factor of Speech (From Sample 2 in Table 2) but With Different Analyzing Windows

| Analysis window (msec) | 500 | 400 | 300 | 200 | 125 | 100 | 50 | 25 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crest factor (dB) | 12.46 | 12.48 | 12.46 | 12.45 | 12.46 | 13.22 | 16.68 | 16.68 |

Note: The table shows the crest factor of speech (from Sample 2 in Table 2) but with different analyzing windows. For shorter windows, the instantaneous peaks are greater with higher calculated crest factors.

Source: Adapted Chasing (2012b); table courtesy of Hearing Review, used with permission.

Hearing Aid Technology and Its Limitation for Music

The technical question arises whether inputs to a microphone of 110 dB SPL can be handled as well as inputs of 75 dB SPL. Since the late 1980s modern hearing aid microphones have been able to handle inputs of 115 dB SPL with minimal distortion. Modern digital-to-analog (D/A) converters also can handle mathematical values that are quite high. The limitation appears to be in the input compressor associated with the analog to digital (A/D) conversion process at the “front end of the hearing aid.”

Modern 16-bit hearing aids have a theoretical limitation of a dynamic range of its input of 96 dB. Because of many engineering and design compromises, the effective dynamic range is typically less than this. While a 96 dB dynamic range (e.g., 0 dB SPL to 96 dB SPL) is adequate for most speech (with the possible exception of a person’s own voice at the level of their own hearing aids), the upper limit of this range tends to be a limiting factor when it comes to music as an input.

If the input is distorted at the level of the A/D converter, then no amount of software reprogramming that occurs later in the circuit will improve the situation. This front-end distortion is perpetuated through the hearing aid. The best approach is to adjust the front-end elements of the hearing aid such that the more intense components of the music are within the operating range of the A/D converter.

In this issue, several articles are dedicated to just this approach. Some ingenious technologies already exist in the marketplace. These include compressing and then expanding the signal on either side of the A/D converter (in a similar vein as ducking under a low hanging door way), altering the input by the selection of a hearing aid microphone that has a different characteristic, and altering the 96 dB dynamic range from 0 dB SPL to 96 dB SPL, to 15 dB SPL to 111 dB SPL. Other approaches exist where an input to a direct audio input jack or an inductive input has been reduced by 10 to 12 dB by the use of a resistive circuit. Each of these technologies is based on the understanding of the limitations of modern A/D converters as well as the actual levels of the musical input to a hearing aid. And each of these technologies can be used with cochlear implants as well as hearing aids. This is an input-related issue and not an output or programming related issue. Only when the front end has been configured to be distortion free can a hearing aid be optimized for listening to and the playing of music.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- American National Standards Institute. (2003). American National Standard specification of hearing aid characteristics (ANSI S3.22-2003). New York, NY: Author [Google Scholar]

- Chasin M. (2006). Sound levels for musical instruments. Hearing Review, 13, 3 [Google Scholar]

- Chasin M. (2012a). Music and hearing aids. Audiology Practices, 4, 2 [Google Scholar]

- Chasin M. (2012b). Should all hearing aids have a -6 dB/octave microphone? Hearing Review, 19, 10 [Google Scholar]

- Cox R. M., Mateisch J. S., Moore J. N. (1988). Distribution of short-term RMS levels in conversational speech. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 84, 1100-1104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson K. (2003). Acoustic and auditory phonetics (2nd ed.). Oxford, UK: Blackwell [Google Scholar]

- Moore B. J., Fullgrabe C., Stone M. A. (2011). Determination of preferred parameters for multiband compression using individually fitted simulated hearing aids and paired comparisons. Ear and Hearing, 32(5), 556-568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricketts T. A., Dittberner A. B., Johnson E. E. (2008). High frequency amplification and sound quality in listeners with normal through moderate hearing loss. Journal of Speech-Language-Hearing Research, 51, 160-172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivian L. J., White S. D. (1933). On minimum audible sound fields. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 4, 288-321 [Google Scholar]