Abstract

Music can have sound levels that are in excess of the capability of most modern digital hearing aids to transduce sound without significant distortion. One innovation is to use a hearing aid microphone that is less sensitive to some of the lower frequency intense components of music, thereby providing the analog-to-digital (A/D) converter with an input that is within its optimal operating region. The “missing” low-frequency information can still enter through an unoccluded earmold as unamplified sound and be part of the entire music listening experience. Technical issues with this alternative microphone configuration include an increase in the internal noise floor of the hearing aid, but with judicious use of expansion, the noise floor can significantly be reduced. Other issues relate to fittings where significant low-frequency amplification is also required, but this type of fitting can be optimized in the fitting software by adding amplification after the A/D bottle neck.

Keywords: music, microphones, distortion

Introduction

One of the main differences between normal speech and music is the intensity level. Conversational speech at average conversational levels is typically in the 65 to 70 dB SPL range, and some of the more intense components of the conversation can be in the mid-80 dB SPL range. Shouting can be a little more intense but generally this is only true for the lower frequency sonorant sounds.

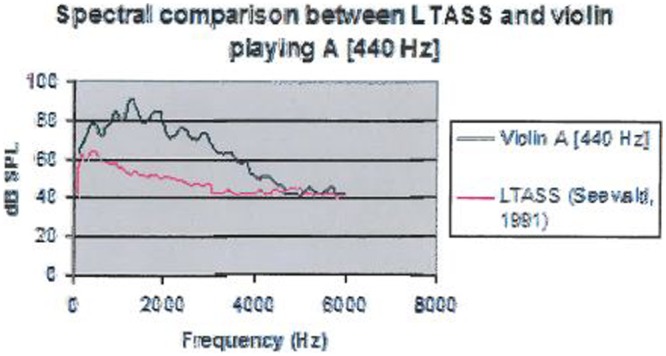

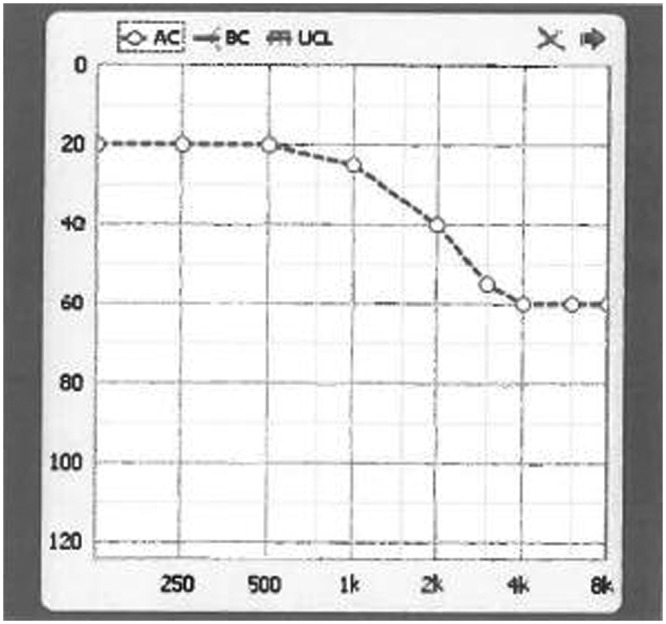

Conversely, even quiet instrumental music can exceed 90 dB SPL with some passages at sustained levels of greater than 105 dB SPL. These typical sound pressure levels are found in both classical and pop music forms. Some classical pieces and for sure rock/pop/country concerts levels can exceed levels of 120 dB SPL. (See, for example, Chasin, 2006; Chasin & Schmidt, 2009). Whether a hearing aid wearer is simply enjoying the music or if they are actively involved in playing music, these loud intensity levels will undoubtedly challenge the modern digital instrument (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

While music spectra are highly variable, in general, there is greater intensity in the lower frequency regions

In addition to the overall level of music, another factor that challenges the circuitry of modern digital hearing aids is the crest factor. The “crest factor” is defined as the difference between the instantaneous peak level of a given signal and the RMS (Root Mean Square) of the given signal expressed in dB. Traditionally, typical crest factors in speech are considered to be about 12 dB, suggesting that the more intense parts of speech are about 12 dB higher than the average level of the given conversation. If we consider an average conversation at a level of 65 dB SPL, it could be expected that the peaks of the conversation would be around 77 dB SPL (65 +12). This concept is undoubtedly familiar for anyone involved in testing hearing instruments when utilizing the ANSI S 3.22 standard.

In contrast to speech, the crest factor for music can be greater. It is typical that crest factors in music can range from 14 dB to more than 20 dB (with an average of 18 dB) depending on the music played and the physical characteristics of the musical instrument the piece is played on. Thus instantaneous peak levels being generated from a given musical instrument will be typically 18 dB more intense than the average level of the played music

As is well known, sound pressure level drops off rapidly as the distance increases. For those individuals who play musical instruments where the sound is being generated close to the hearing instrument microphone (close to the ear), the overload problem will be naturally a greater risk. Such instruments that are close to the ear include the violin, viola, flute, and the bassoon, to name a few.

Analog to Digital Converters

If you have ever had opportunity to visit a modern recording studio, chances are it will be a digital recording studio. As you may know one of the key pieces of equipment in the modern digital studio is the A/D (Analog to Digital) convertor. This device in short converts the real world analog signals from your musical instrument (picked up via the recording microphone) into a stream of precisely timed ones and zeroes that represent the analog signal input. From here the digital information can be processed and stored in various manners and formats with varying accuracies (or bit rates).

Hearing aids also use microphones to pick up the sound in any given environment. Digital hearing aids not unlike the digital recording systems also have A/D convertors.

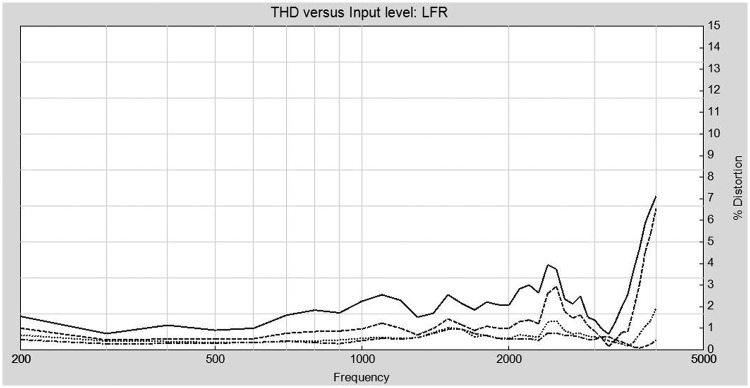

However, unlike a recording studio, digital hearing aids don’t have unlimited power available to drive the A/D convertors. Hearing aids need to operate at 1 to 1.3 volts and must keep the battery current consumption in check to have reasonable battery life for the wearer of the device. With limited power available, the operating range of the hearing instrument A/D convertor is also limited. The hearing instrument microphone can typically handle up to 118 dB peak pressure levels, which is quite an intense sound, so the microphone itself generally is not a problem. Modern digital hearing aids typically target a 16-bit A/D converter that strive for a dynamic range of about 96 dB at best (but typically ends up being somewhat less than 96 dB, closer to 85 dB). A/D converters found in modern hearing aids can start overloading when presented with signals in the range of 105 dB to 110 dB SPL and beyond and thus producing front end distortion (see Figure 2). Alternatively stated, if the front end of the amplification chain gets overloaded or “overworked” the input signal can become distorted. In this situation it is very challenging algorithmically to “unclip” the signal in the later signal processing stages of the hearing aid.

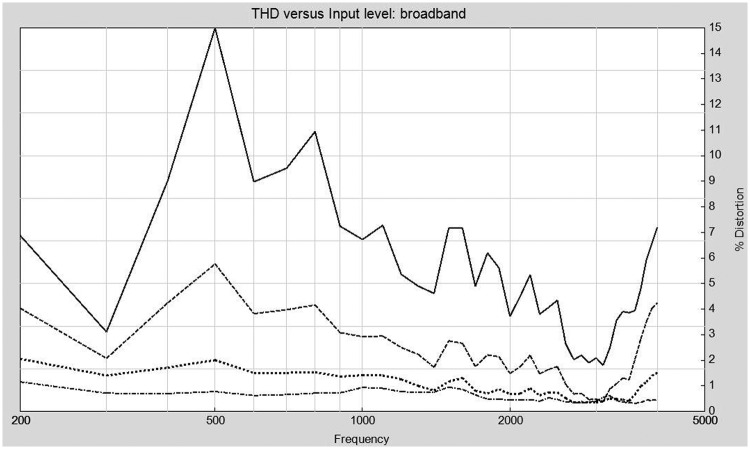

Figure 2.

THD Results with broadband mic for 95 (dash dot line), 100 (dot line), 105 (dash line), and 110 (solid line) dB SPL inputs

While a “less than full” dynamic range is sufficient for most speech inputs, instrumental music can easily exceed 105 dB SPL and thus present a signal that is beyond the upper limits of the dynamic operating range of the hearing aid A/D convertor. Instrumental music, having both an overall higher intensity and greater crest factor, tends to overdrive the front end of the hearing aid because of the limited available dynamic range on the given A/D converters.

Interestingly enough, many analog hearing aids of the 1990s (which of course, have no need for an A/D converter) were much better positioned to handle louder music. The input dynamic range was typically limited only by the microphone and in some cases, the input compressors.

A Typical Musicians’ Hearing Loss

It is quite common that musicians and/or audiophiles with hearing loss may only experience hearing loss in the high frequency regions—they may in fact hear fairly well at 1000 Hz and below (see figure 3). For such cases an open fit hearing instrument, usually a nonoccluding BTE is ideal. This type of fitting balances adequate gain versus feedback while minimizing the occlusion effect. The typical frequency response is one with minimal or no gain below 1000 Hz. Low-frequency sounds can enter the nonoccluded ear canal directly. However, the intense low-frequency sounds commonly heard in music also enter the hearing instrument microphone. This is where a signal processing problem can occur.

Figure 3.

Commonly observed high frequency hearing loss typical of presbycusis, noise, and music exposure

Typical broadband microphones found in digital hearing instruments are sensitive to all frequencies between about 100 Hz to beyond 20 kHz—the limiting factor for the high frequency end is generally the integrated hybrid circuit where the upper frequency cutoff is around 10 KHz these days as this is more than enough for speech. Additionally, wider bandwidth requires additional battery current.

For many individuals with a high-frequency sensorineural hearing loss, there is little need for low-frequency gain for a typical musicians’ hearing loss. In this case, there is really no need to route the low-frequency sound energy through the microphone and A/D converter. The intense low-frequency sound often found in music can overdrive the front end A/D converter of the hearing aid causing significant distortion. The lower frequency components are still heard by the hearing aid wearers because these sounds enter through the unoccluded vent directly. For the digital hearing instrument with the broadband mic, the loud low-frequency energy of the music will be transferred through to the A/D convertor causing unwanted harmonics to be amplified and passed on to the wearer of the instrument.

A −6 dB/Octave Microphone Solution

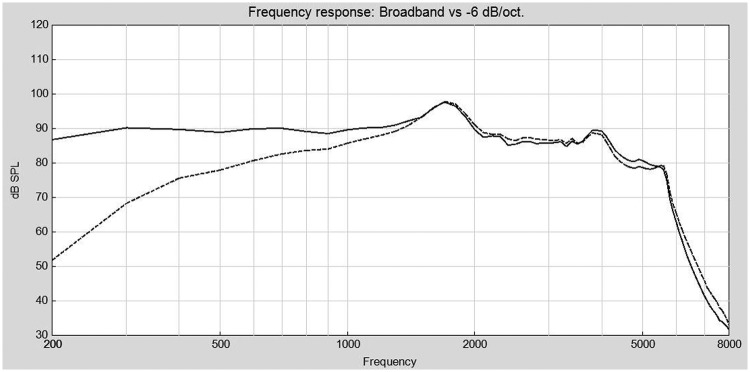

A relatively simple modification to the overloaded hearing aid would be to use a microphone that is less sensitive to the lower frequencies: such a microphone substitution that could be considered is a −6 dB/octave LFR (low-frequency roll-off) microphone. Figure 4 below compares the frequency response impact of applying the −6 dB/octave low-frequency microphone versus a standard broadband microphone for the same hearing instrument.

Figure 4.

Measured hearing instrument output: Standard microphone versus −6 dB/octave LFR microphone: (all hearing aid adaptive features disabled)

The −6 dB/octave LFR microphone modification is not intended to alter the final frequency response measured in the ear. Having a microphone that is less sensitive to low-frequency sounds simply prevents too much of that intense low frequency energy often found in music from entering the hearing aid. This in turn reduces the risk of input signals that can overload the A/D, which in turn reduces potential distortion problems. The unamplified low-frequency energy would enter through the vent, bypassing the hearing aid circuitry.

As seen in Figure 5, there is a substantial improvement (reduction of) harmonic distortion at the output of the hearing instrument at the onset of large low-frequency energy input versus the same hearing instrument fitted with a broadband microphone as in Figure 2.

Figure 5.

THD results with −6 dB/Octave Mic for 95 (dash dot line), 100 (dot line), 105 (dash line), and 110 (solid line) dB SPL inputs

What Are Some of the Technical Trade-Offs?

Engineering is the art of making trade-offs, and one must consider the following design issues when considering exchanging the typically used broadband microphone for the −6 dB/octave low-frequency roll-off microphone: (a) Microphone noise floor versus sensitivity; (b) Directional hearing aid microphone characteristics; and (c) reduced available fitting range.

Microphone Noise Floor Versus Sensitivity

The noise floor of a −6 dB/octave LFR microphone is essentially the same as its broadband counterpart for the same microphone form factor/model family. However, the sensitivity to low-frequency sounds is substantially reduced. Thus the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in the low frequencies for the −6 dB/octave LFR microphone is poorer than its broadband counterpart.

When a hearing instrument system is modified with the −6 dB/octave LFR microphone, more digital gain may need to be applied in the low frequencies for the given fitting to achieve the same result that a broadband microphone would yield in the lower frequency region. Generally, this means that the noise floor of the microphone will be amplified as well. This can result in higher audible noise for the hearing instrument wearer. This is basically the same effect that occurs when directional microphone systems are compensated for gain in the lower frequency region.

A tool to help combat this potential risk of higher noise is related to expansion. Low-level Expansion (LLE) is a signal processing technique included in most if not all modern digital hearing aids. LLE can be configured to reduce the audible noise floor and can be controlled by altering a threshold on the input-output curve. This can be set to a specified level whereby below the specified LLE threshold, the gain of the hearing instrument system is rapidly reduced at some specifically defined rate. For multifrequency band–based amplification systems (true of most digital hearing instruments today) each frequency region can have the LLE threshold set independently. This allows the hearing aid design engineer to maintain the LLE thresholds for the high-frequency region and increasingly raise the LLE thresholds for the lower frequency bands.

The trade-off of low-level expansion is reduced gain for low-level inputs in the given frequency region for which the higher threshold is set. In other words the higher one sets the LLE threshold, the less gain that is applied for soft sounds (soft speech). Due to the fact that the individual frequency bands can have independent thresholds, there is potentially no impact to the higher frequency regions for amplification of soft sounds; only the low frequency region would see an impact. However, for the fitting that this modified system is intended for, there is generally very little gain required in the lower frequency region since it is an open fit. Thus there is really no issue.

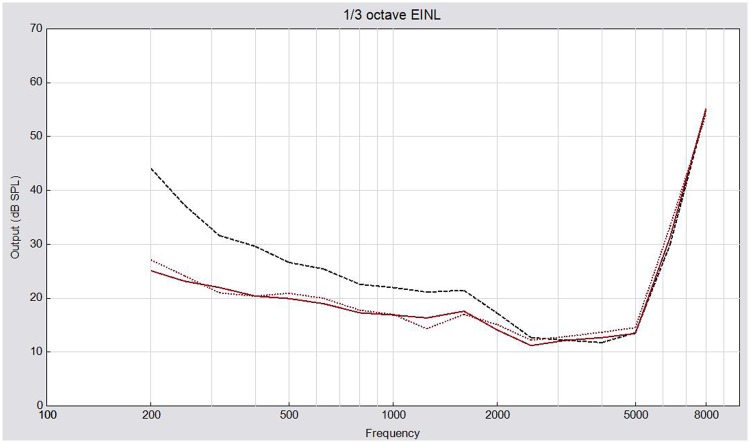

Figure 6 shows the internal noise for three conditions: (a) a broadband microphone typically found with nonoccluding BTEs; (b) −6 dB/octave LFR microphone with less low-frequency sensitivity; and (c) −6 dB/octave LFR microphone with the low-level expansion thresholds optimized. Aside from the use of expansion, in general when listening to music that is by nature more intense, quite often any additional audible noise from the microphone is masked by the intense music input.

Figure 6.

One-third octave noise measure for a given fitting

Note. Solid = broadband microphone system; Dash= -6dB / octave (LFR) microphone system; Dot = -6dB / octave (LFR) microphone system with adjusted LLE thresholds.

Directional Characteristics

A second consideration when applying a −6 dB/octave LFR microphone pair to a hearing aid design is that the phase and sensitivity matching of the microphone pair for the purposes of creating an optimal directional hearing aid system now becomes more challenging—mainly due to the matching process that must focus in on the low-frequency performance.

The −6 dB/octave LFR microphone pairs can, however, be matched, albeit the process is a little more challenging. Thus the concern for loss of directionality when using the −6 dB/octave LFR microphone pairs is really a minor issue as long as sufficient care is given.

Reduced Available Fitting Range

Due to the reduced low-frequency sensitivity of the −6 dB/octave LFR microphone, it is clear that the fitting range of the given instrument will be reduced as compared with the same hearing instrument with a broadband microphone. The amplifier in the device has less low-frequency energy input available to amplify. Having said this, it is generally not an issue for most of the targeted mild-to-moderate high-frequency loss open fittings for which this modified instrument is intended. If increased low-frequency gain and output is required for a hearing aid fitting, then this can be programmed in the hearing aid fitting software. Such changes are after the A/D converter and therefore there should be no increase in distortion.

The Coda

Using a −6 dB/octave LFR microphone in a digital hearing aid configured for an open fit (nonoccluding) can be a practical solution for the hearing impaired musician and/or audiophile when playing or listening to loud music. In addition to the higher overall SPL involved, the crest factor of a signal is what more frequently gives rise to overload or clipping-induced distortion. Although a noncomplicated solution, −6 dB/octave LFR microphone provides an innovative option that hearing care professionals can use to assist in a presentation of clear undistorted sound for their clients.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Chasin M. (2006). Hearing aids and musicians. Hearing Review, 13(3), 24-31 [Google Scholar]

- Chasin M., Schmidt M. (2009). The use of a high frequency emphasis microphone for musicians. HearingReview, 16(2), 32-37 [Google Scholar]