Abstract

Cochlear implant systems that combine electric and acoustic stimulation in the same ear are now commercially available and the number of patients using these devices is steadily increasing. In particular, electric-acoustic stimulation is an option for patients with severe, high frequency sensorineural hearing impairment. There have been a range of approaches to combining electric stimulation and acoustic hearing in the same ear. To develop a better understanding of fitting practices for devices that combine electric and acoustic stimulation, we conducted a systematic review addressing three clinical questions: what is the range of acoustic hearing in the implanted ear that can be effectively preserved for an electric-acoustic fitting?; what benefits are provided by combining acoustic stimulation with electric stimulation?; and what clinical fitting practices have been developed for devices that combine electric and acoustic stimulation? A search of the literature was conducted and 27 articles that met the strict evaluation criteria adopted for the review were identified for detailed analysis. The range of auditory thresholds in the implanted ear that can be successfully used for an electric-acoustic application is quite broad. The effectiveness of combined electric and acoustic stimulation as compared with electric stimulation alone was consistently demonstrated, highlighting the potential value of preservation and utilization of low frequency hearing in the implanted ear. However, clinical procedures for best fitting of electric-acoustic devices were varied. This clearly identified a need for further investigation of fitting procedures aimed at maximizing outcomes for recipients of electric-acoustic devices.

Keywords: electric and acoustic stimulation (EAS), cochlear implants (CI), hearing aids (HA)

Introduction

Continuing developments in implant electrode design and improved surgical techniques have resulted in increasing incidence of preservation of residual acoustic hearing in the implanted ear following cochlear implantation (Friedland & Runge-Samuelson, 2009; Talbot & Hartley, 2008). In turn, this has led to an expansion of CI candidature to include patients with significantly more residual hearing, and the development of cochlear implant technology for combined electric and acoustic stimulation (EAS) in the implanted ear. In the EAS or Hybrid application, a cochlear implant electrode array is implanted into the cochlea and electrical stimulation is used to convey high frequency information to the user. This is coupled with a hearing aid in the implanted ear, that is used to convey low frequency information to the user via acoustic stimulation.

To date, the focus of EAS research has been on the degree of postoperative hearing preservation outcomes (Arnoldner et al., 2010; Gantz & Turner, 2003; Gstoettner et al., 2006; James et al., 2006; Kiefer et al., 2005; Lenarz et al., 2006; Mukerjee et al., 2012; Skarzynski, Lorens, Piotrowska, & Skarzynski, 2010; von Ilberg et al., 1999; Woodson, Reiss, Turner, Gfeller, & Gantz, 2009) as well as the perceptual benefits of combined electric-acoustic applications for: speech perception (Büchner et al., 2009; Dorman & Gifford, Dorman, & Brown, 2010; Fraysse et al., 2006; Gantz, Turner, Gfeller, & Lowder, 2005; Helbig & Baumann, 2009; James et al., 2005; Lenarz et al., 2009; Lorens, Polak, Piotrowska, & Skarzynski, 2008; Simpson, McDermott, Dowell, Sucher, & Briggs, 2009; Skarzynski et al., 2012; Turner, Gantz, Karsten, Fowler, & Reiss, 2010); localization (Dunn, Perreau, Gantz, & Tyler, 2010); perception of music (Brockmeier et al., 2010; Dorman, Gifford, Spahr, & McKarns, 2008; Gfeller, Olszewski, Turner, Gantz, & Oleson, 2006; Gfeller et al., 2007; Gifford, Dorman, & Brown, 2010); and functional performance (Driver & Stark, 2010; Gstoettner et al., 2008; Gstoettner et al., 2011; Helbig et al., 2011). In general, results with EAS have been compared with either the cochlear implant used in isolation, or with the preoperative condition with hearing aids.

A variety of EAS fitting approaches have been reported in the literature. EAS outcome studies report utilising a range of practices for both electric and acoustic stimulation. As the number of recipients increases, research into how to best fit EAS devices to individuals with different degrees of postoperative residual hearing is crucial.

Previously, Talbot & Hartley (2008) have reported a descriptive review of the effectiveness of EAS intervention as compared with conventional cochlear implant use with respect to pitch perception. However, that review was not structured to address three critical issues:

what is the range of acoustic hearing in the implanted ear that can be effectively used for an electric-acoustic fitting?;

what benefits are provided by combining acoustic stimulation with electric stimulation?; and

what clinical fitting practices have been developed for devices that combine electric and acoustic stimulation?

The examination of these issues should lead to the development of guidelines and recommendations for fitting EAS devices.

Method

Search Strategy

A systematic review of literature was conducted using methods that followed the guidelines provided by Cox (2005). The initial electronic databases searched included PubMed and MEDLINE. The following key words were entered into the search fields: “Cochlear implant OR cochlear implantation AND acoustic stimulation AND electric stimulation” Additional terms used in subsequent searches: “Cochlear Implantation OR Cochlear Implants AND Electric Stimulation AND Acoustic Stimulation AND Hearing Loss, Sensorineural OR Hearing Loss, High-Frequency. In addition, a textbook by Van de Heyning and Kleine Punte, 2010 was searched by hand to identify references that met the search criteria. Finally, a further electronic search of Web of Science (ISI), SCOPUS - V.4 (Elsevier), CINAHL PLUS (EBSCO), PsycINFO (CSA) databases and the reference lists of the relevant manuscripts were examined for articles that did not appear in prior searches.

Selection Procedure

The search strategy yielded 168 articles. Following a preliminary examination of all 168 article abstracts, 58 were selected for more comprehensive review. The full text articles were retrieved for the 58 articles and were analyzed with regard to the inclusion and exclusion criteria below.

A final 27 met the criteria and were identified for detailed analysis and included in this review.

Inclusion Criteria

Studies were selected for detailed analysis if they met the following inclusion criteria:

publication of the results appeared in a peer-reviewed article or textbook. Excluded repeat publications by the same author/research group using the same subject group and reporting no additional or new evidence.

randomized controlled trials (RCT), nonrandomized controlled trials, cohort studies, case-control studies;

studies that implanted “Hybrid or EAS” candidates with preoperative residual low frequency hearing (Pure tone thresholds ≤ 65 dB HL for 250 Hz and 500Hz) and severe to profound hearing loss in the high frequencies (Pure tone thresholds >70 dB HL at 1500 Hz);and

studies that report on preservation or performance data with a minimum of 6 months postoperative device experience only, to ensure the low frequency air-bone gap and cochlear implant MAP/program have stabilized (Helbig et al., 2011; Lenarz et al., 2009).

articles published between 2000 and 2012

Exclusion Criteria

Studies were excluded from detailed analysis on the following criteria:

expert opinion-based evidence and case studies;

studies that implanted only “traditional” or “conventional” cochlear implant candidates with severe to profound, sensorineural hearing loss;

studies reporting hearing preservation or performance data with less than 6 months postoperative device experience.

Rating of Quality Evidence

Two evidence-based practice (EBP) review rating schemes were used to evaluate the research evidence. The first scheme was the Valente et al. (2006) scale design which ranks studies according to the strength of research evidence. This method was used initially to filter the large number of studies based on: evaluation of the research design used (Level of evidence: 1-6); the quality and relevance of the data (Grade of recommendation: A-D); and the effectiveness (EV: real-world based) and efficacy (EF: laboratory based) of the study. Based on these, an overall strength of recommendation (Strength of evidence: I-III) was made. This process yielded similar strength of evidence for all the studies that met the search criteria. The second scheme was designed by MacDermid (2004). A number of research design principles (subject selection, methodology, endpoints, methods of analysis, results, and conclusions) were used to rate the source of evidence. A total of 24 items are assessed and a total score from (1-48) is calculated. A higher score on the MacDermid scale reflects a higher level of quality of evidence or high internal validity. Whilst a study by Olson and Shinn (2008) showed a strong correlation between the two rating scales used, MacDermid’s critical review worksheet “Evaluation of effectiveness Study design” worksheet and “Evaluation Guidelines for Rating the Quality of an Intervention Study” were used together to qualitatively score and rank the evidence from the final 27 studies in more detail. The evidence was also categorized according to whether assessments were carried out under laboratory/ ideal conditions (Efficacious, EF) or in the real world (Effectiveness, EV).

Results

A total of 27 articles were identified for detailed analysis and inclusion in this review. All articles were published between 2005 and 2012. The review of the studies yielded evidence of a moderate strength (B to D). No meta-analysis or truly randomized controlled trial studies were identified.

Discussion

Q1. What is the range of acoustic hearing in the implanted ear that can be effectively used for an electric-acoustic fitting?;

Preservation of residual hearing for the purpose of combining electric and acoustic stimulation has been reported by several research groups using a variety of standard and research electrode arrays and atraumatic surgical techniques (Friedland & Runge-Samuelson, 2009; Talbot & Hartley, 2008). To determine the postoperative fitting range in the implanted ear that can be effectively aided, these published studies were classified into three sub-groups: firstly, Type I studies that implanted conventional, perimodiolar electrode arrays using the “Advanced Off Stylet” technique and a cochleostomy approach to achieve a full insertion (300°-430°) of array; secondly, Type II studies that implanted standard, full length or medium length electrode arrays with reduced insertion depth (360°), using either a cochleostomy or round window approach; and lastly, Type III studies that implanted shorter and thinner electrodes, such as the “Hybrid or EAS arrays,” that were specifically designed to increase the likelihood of preserving residual hearing, using either a cochleostomy or round window approach. A summary of the 14 studies that met the search inclusion criteria is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

A Summary of 14 Articles That Provide Information on Postoperative Hearing Preservation Outcomes That Met the Systematic Review Inclusion Criteria.

| Type I. Perimodiolar electrode array ( “Advance off stylet’ technique) studies | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Study design | Implant/electrode/surgical approach | Key findings | Level, grade strength, EV/EF | MD score |

| James et al., 2006 | 1 group: N = 10 adults | Implant: Nucleus 24 Contour Advance. Electrode array: 19mm TL, 22 channel | 70% preservation of hearing to varying degrees for participants at minimum of 6 months. | 3B II EF | 25/48 |

| Cochleostomy (<1.5mm) Anterior & inferior to RW. Insertion depth to 17-19mm or (300°-430°). | Range: Individual thresholds in implanted ear from normal to profound at 125-500Hz & profound at ≥750Hz. | ||||

| Simpson. McDermott, Dowell, Sucher, & Briggs, 2009 | 1 group: N = 5 adults | Implant: Nucleus Freedom Contour Advance Electrode array: 22 channel, 9mm TL. | 100% preservation to varying degrees for trial participants after a minimum of 6 months. | 3B II EF | 30/48 |

| Cochleostomy: Inferior to RW. “AOS” technique. Insertion depth to 17-19mm or (300°-430°). | Range: Individuals thresholds in implanted ear from mild to profound HL range at 125-500Hz & profound at 750Hz. | ||||

| Type II. Standard length (Reduced/shallow insertion depth) and/or medium length straight electrode array studies | |||||

| Study | Study design | Implant/electrode/surgical approach | Postoperative hearing preservation | Level, grade strength, EV/EF | MD score |

| Kiefer et al., 2005 | 1 group: N = 13 adults | Implant: MED-EL Combi 40+ | 84.6 % preserved hearing either fully or partially reported at minimum of 12 months. | 3C II EF | 24/48 |

| Electrode array: 12 channel, 1.Standard/flex 31.5mm TL (n = 6) 2.Medium, 26.4mm TL (n = 7). | Range: No individual data reported at 12 months. | ||||

| Cochleostomy. Insertion depth to 18-24mm or 360° | |||||

| Gstoettner et al., 2006 | 1 group: N = 23 adults | Implant: MED-EL Combi 40+ | 70% preservation to varying degrees for trial participants after a minimum of 6 months (range 6 -70 months). | 4C II EF | 20/48 |

| Electrode array: 12 channel 1.Standard/flex array 31.5mm TL 2.Medium array, 26.4mm TL. | Range: Individuals thresholds in implanted ear from normal to profound range at 125-500Hz & severe to profound at 750Hz. | ||||

| Cochleostomy. CT scans to predict insertion depth to achieve 360° (18-24mm). Reduced insertion for longer arrays. | |||||

| Skarzynski, Lorens, Piotrowska, & Anderson, 2007 | 1 group: N = 9 children | Implant: MED-EL Combi 40+ or Pulsar. | 100% preservation either partially or fully for trial participants after a minimum of 6 months (range 6-12 months). | 4C II EF | 23/48 |

| Inclusion criteria: “partial deafness” | Electrode array: 12 channel 1.Standard/flex 31.5mm TL (n = 1) 2.Medium, 26.4mm TL (n = 8) | Range: Individuals thresholds in implanted ear from normal to severe HL range at 125-500Hz & moderate to profound at 750Hz . | |||

| RW approach. Reduced insertion depth (20mm) for longer arrays | |||||

| Gstoettner et al., 2008 | 1 group: N = 18 adults | Implant: MED-EL Combi 40+ | 83.2 % preserved hearing either fully or partially for trial participants after a minimum of 12 months. | 4C II EF & EV | 24/48 |

| Electrode array: 12 channel Medium array, 26.4mm TL, | Range: No individual data reported at 12 months. | ||||

| Cochleostomy: Limited electrode insertion of 18mm-22mm. | |||||

| Skarzynski, Lorens, Piotrowska, & Podskarbi-Fayette, 2009 | 2 groups: Total =28 N = 19 adults N = 9 children | Implant: MED-EL Combi 40+ or Pulsar. | 84% preserved hearing for trial participants either partially or fully after a minimum of 12 months (range 1-4 years postoperatively). | 3C II EF | 26/48 |

| Electrode array: 12 channel 1.Standard/flex, 31.5mm TL (n = 18) 2.Medium, 26.4mm TL,(n = 10). | Range: No individual data. Means reported. | ||||

| RW approach. Reduced insertion depth for longer arrays (20mm). | |||||

| Type III. Electroacoustic electrode array studies | |||||

| Study | Study design | Implant/electrode/surgical approach | Postoperative hearing preservation | Level, grade strengthen/EF | MD score |

| Gantz, Turner, Gfeller, & Lowder, 2005 | 1 group N = 21 adults | Implant: Nucleus Hybrid 10. | 95.8 % preserved hearing either partially or fully after minimum of 6 months (range 6 months - 36 months). | 3C II EF | 24/48 |

| Electrode array: 6 channel. Short array 10 mm (T L) | Range: No individual data. Means reported. | ||||

| Cochleostomy (0.5mm) | |||||

| Gstoettner et al., 2009 | 1 group N = 9 total | Implant: MED-EL Pulsar | 100 % preserved hearing either partially or fully after minimum of 6 months (range 6 - 15.65 months). | 4C II EF | 22/48 |

| Electrode array: 12 channel Flex EAS 6.4mm T L | Range: Individuals thresholds in implanted ear from normal to profound HL range at 125-500Hz & severe to profound at 750Hz. | ||||

| RW approach (n = 7) Cochleostomy (n = 2). Insertion depths to achieve 360° (18-22mm). Calculated to enter the 1000 Hz region. | |||||

| Lenarz et al., 2009 | 2 groups N = 32 adults

|

Implant: Nucleus Hybrid—L24 | 100 % preserved hearing. * | 3C II EF | 27/48 |

| Electrode array. 22 channel L array, 18mm TL | * PTA results reported at * 3 months (n = 32/32) 6 months (n = 22/32) & 12 months (n = 16/32) postoperatively. | ||||

| RW approach & and full insertion (depth of 16mm or 270°) | Average increase in air-bone gap was 4.4 dB at 1 month. At 6 months there was an average increase of 1.2 dB compared to preoperative value. | ||||

| Danka, Pillsbury, Adunka, & Buchman, 2010 | 2 groups: N = 20 adults | Implant: MED-EL Combi 40+ & Pulsar CI100. | Postoperative hearing preservation: minimum of 6 months device use. | 2B II EF | 32/48 |

| EAS array (n = 10) & Standard CI array (n = 10) groups matched for age & word scores. | Electrode array: 12 channel 1. Flex EAS, 26.4 mm TL (n = 10) 2. Standard straight 31mm TL full insertion (n = 10) | EAS array: 90 % preserved hearing | |||

| EAS group: RW approach (n = 5) & Cochleostomy (n = 5) | Standard array: 0% preserved hearing | ||||

| Range: No individual data. Means reported | |||||

| Woodson et al., 2009 | 1 group N = 81 total | Implant: Nucleus Hybrid 10 | 90 % preserved hearing either partially or fully after minimum of 12 months (ranging from 12 months to 5 years). | 3B II EF | 29/48 |

| Phase I & II: <60 dB HL below 500Hz | Electrode array: Short array, 6 channel, 10 mm (TL) | Range: Individuals thresholds in implanted ear from normal to profound HL range at 125-750 Hz. | |||

| Cochleostomy (0.5mm) anterior & inferior to RW. | |||||

| Helbig et al., 2011 | 1 group N = 18 adults | Implant: MED-EL Pulsar CI100 | 100 % preserved hearing either partially or fully after minimum of 15 months postoperatively. | 3B II EF & EV | 28/48 |

| Electrode array: Flex EAS, 12 channel, 26.4 mm TL | |||||

| RW insertion or Cochleostomy | |||||

| Skarzynski et al., 2012 | 3 group N = 23 adults | Implant: Nucleus Straight Research Array | Hybrid candidates PTA results reported at * 13 months postoperatively (EC group n = 7/7 & EAS group 5/7 EC). 100 % preserved hearing either partially or fully. | 3C II EF | 27/48 |

| 1. EC group ≤ 50 dB HL at 500Hz (n = 7) 2. EAS group Between 50 and 80dB HL (n = 7) 3. ES group ≥80 dB HL. | Electrode array: 22 channel, 25 mm TL | Slight improvement between 1 month and 4 months postoperatively due to clearing of middle ear fluid. | |||

| RW insertion | |||||

Abbreviations: AOS= Advanced Off Stylet; CI: Cochlear implant; EAS=Electric-acoustic Stimulation; EC=Electrical complement; EF=Efficacious or laboratory based measures; ES=Electrical stimulation; EV= Effectiveness or real world measures; IE= Implanted ear; HA= Hearing aids; MD score= MacDermid score; NIE= No implanted ear; NH: Normal hearing; PDCI; Partial deafness cochlear implantation; PTA: pure tone eudiometry; PTT: pure tone thresholds; RW= round window; SN= Sensorineural hearing loss; SNR = signal to noise ratio; TL=Total length.

The preservation of residual hearing was reported to range from 70% to 100% of participants across the14 studies with minimum postoperative timeframes of 6 to 12 months. In these studies the term “Hearing preservation” encompassed both complete and partial preservation. As defined in the studies complete preservation referred to the maintenance of hearing thresholds within 10 dB HL of all preoperative thresholds, whereas partial preservation generally referred to a change in thresholds of greater than 10 dB to 15 dB HL of any preoperative threshold level. The degree of postoperative hearing loss and audiometric configuration varied both across individuals within studies, and across studies (see Table 1: Key Findings & Range).

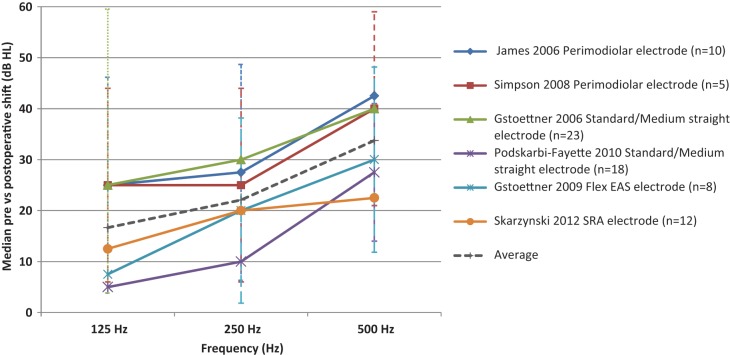

No systematic reporting procedure exists to allow for direct comparisons of postoperative hearing results across various electrode arrays or surgical procedures aimed at improving hearing preservation. In order to compare changes in low frequency acoustic hearing across Type I, II & III studies, the preoperative and postoperative medians at 125 Hz, 250 Hz & 500 Hz were calculated using the raw data from each participant’s audiogram, for six studies out of 14 that provided individual threshold data across frequencies (Gstoettner et al., 2006, 2009; James et al., 2005; Podskarbi-Fayette, Pilka, & Skarzynski, 2010: Skarzynski et al., 2012; Simpson et al., 2009). Thresholds at ≥ 750 Hz were excluded because reporting of thresholds at the octave and intermediate frequencies was highly variable between studies and the preoperative thresholds were already in the severe to profound range. Figure 1 shows the median change in low frequency hearing at 125, 250, and 500Hz. Results from each study are represented by a data point ±SD for the various electrode array studies.

Figure 1.

Median change in low frequency thresholds dB HL ± SD for various electrode array studies.

Figure 1 shows that the greatest shift in acoustic hearing thresholds occurred at 500 Hz across all studies. Median changes in postoperative hearing thresholds ranged from 5 dB to 25 dB HL at 125 Hz, 10 dB to 30 dB HL at 250 Hz, and 28 to 43 dB HL at 500 Hz. When examining threshold shifts it is important to also consider a shift in the context of the impact on individual hearing thresholds and whether they are still aidable. Threshold shifts may move postoperative hearing thresholds into a mild to moderate range that may still benefit from amplification or may also result in final thresholds that are in the severe to profound range that may not.

Table 2 summarizes the hearing preservation data for Type I, II & III studies based on six of the 14 studies that reported individual threshold data across frequencies.

Table 2.

Hearing Preservation Data for Type I, II & III Electrode Array Studies.

| Median threshold shift in dB HL & 25th, 75th percentile (125, 250 & 500 Hz.) |

Postoperative Pure tone thresholds minimum –maximum dB HL |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Array | Total number participants | Average threshold shift in dB HL 3FA (125,250 & 500 Hz) | Median | 25th | 75th | 125 Hz | 250 Hz | 500 Hz | Complete preservation <10dB HL at 3 frequencies | Partial preservation ≥15dB HL at 1 frequency or ≥10dB HL at 2 adjacent frequencies | Total loss No measurable hearing thresholds |

| Type I | 17 | 371,2 | 341,2 | 251,2 | 451,2 | 10-90 | 25-110 | 65-125 | 0 (0%) | 14 (82%) | 3 (18%) |

| James et al.1(2006) | |||||||||||

| Simpson, McDermott, Dowell, Sucher, & Briggs2 (2009) | |||||||||||

| Type II | 41 | 261,2 | 221,2 | 171,2 | 381,2 | 20-90 | 25-110 | 45-125 | 13 (32%) | 21 (51%) | 7 (17%) |

| Gstoettner et al.1 (2006) | |||||||||||

| Podskarbi-Fayette, Pilka, & Skarzynski2 (2010) | |||||||||||

| Type III | 26 | 241,3 | 181,2 | 181,2 | 231,2 | 15-501 | 30-901 | 70-1201 | 21 (22%) | 71 (78%) | 01 (0%) |

| Gstoettner1 (2009) | |||||||||||

| Skarzynski2 (2012) | |||||||||||

| Helbig et al.3 (2011) | |||||||||||

Note: 1,2,3Super script refers to the relevant reference in the Type row the calculation was based on.

Average changes to thresholds at and below 500Hz (3FA) ranged between approximately 24 dB to 37dB HL and median changes ranged from 18 dB HL to 34 dB HL. In general, better preservation outcomes were achieved in Type III studies that implanted electrode arrays specifically designed to preserve residual hearing for the purpose of electric and acoustic stimulation compared to Type I and II studies that implanted standard electrode arrays either partially or fully inserted. Table 2 shows a lower average threshold shift (3FA) postoperatively for Type III studies as compared to either Type I or Type II. In addition, a higher percentage of participants showed complete preservation (defined in this paper as <10dB HL at any 3 frequencies) or partial preservation (defined as ≥15dB HL at 1 frequency or ≥10dB HL at any 2 adjacent frequencies) of residual hearing for Type III studies as compared to either Type I or Type II . Finally, Type I and Type II studies reported total hearing loss percentages of 17% and 18 % respectively, whereas, Type III array studies report no cases of a participant losing all hearing as a result of surgery. There is a wide range of resulting auditory thresholds in the low frequencies following implantation (see Table 2; minimum and maximum pure tone thresholds). Low frequency thresholds in the implanted ear (125, 250, and 500 Hz) ranged from normal to profound. However, the majority of subjects showed thresholds in the severe to profound range for frequencies of 750 Hz and above. The data are too limited at this time to provide a definitive recommendation regarding the risk of this intervention with regard to the various electrode arrays.

It is important to note that the majority of studies that met the inclusion criteria had relatively small numbers of participants and reported results with minimum postoperative timeframes of 6 to 12 months. Whilst a few studies reported outcomes for longer timeframes, unfortunately, these results were combined with results from much shorter time periods. Examination of the study evidence revealed a high degree of variability in assessment time frames and reporting procedures, therefore, the evidence is insufficient to provide any recommendation regarding the longer term changes in postoperative hearing following this intervention.

In summary, studies investigating preservation of residual acoustic hearing have shown that preservation of low frequency hearing was achieved in the majority of patients, particularly with the use of electric-acoustic arrays. However, there is on average, a reduction in the low frequency acoustic thresholds postoperatively. On an individual level, there is a wide range of resulting auditory thresholds and audiometric configurations, with the majority available for EAS application following implantation. Given this, there is a need for a range of amplification options to accommodate degrees of hearing loss from mild to profound in the implanted ear. The review also emphasizes the need for additional research studies utilizing longer timeframes with minimum of 2 to 5 years postoperatively and larger studies as postoperative hearing preservation is not always stable and changes in postoperative hearing can continue to occur. It is recommended that studies do not combine hearing preservation data from various postoperative timeframes or exclude any enrolled participants. Standard reporting of thresholds at octave and intermediate frequencies, median and mean postoperative threshold changes at all frequencies and preoperative and postoperative audiometric data for both ears for all enrolled participants would enable meta-analysis methods to be used to examine preservation results across studies, across surgical technique and electrode arrays.

A systematic and consistent reporting procedure for all hearing preservation results would also help clinicians in the preoperative counseling stage to provide a clearer understanding of risks of this intervention and assist patients considering this option in making a fully informed choice. An international consensus statement on recommended reporting practices for postoperative hearing preservation and performance data for EAS devices would be clinically useful and relevant.

Q2. What benefits are provided by combining acoustic stimulation with electric stimulation?

Following review, 18 studies were selected for detailed analysis to address the second question concerning benefit of combining acoustic and electric stimulation. Findings are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

A Summary of 18 Articles That Provide Information on Postoperative Outcomes That Met the Systematic Review Inclusion Criteria.

| 1. Perimodiolar electrode array ( “Advance off stylet’ technique) studies | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Participants | Outcome measures | Key findings | Level, Grade Strength, EV/EF | MD Score |

| James et al., 2006 | 1 group: N = 10 adults | Words at 65 dB SPL in quiet; German, Spanish & French | CI alone scores significantly better than preoperative scores with HAs, in quiet & noise. (N = 7/10) | 3B II EF | 25/48 |

| Inclusion criteria: Word scores ≥10% (IE). Symmetrical. | Sentences at 70 dB SPL in multitalker babble (+5dB SNR) | Mean CI + Ipsilateral HA scores better than CI alone scores in quiet & noise (not statistically significant). | |||

| Single loudspeaker at 0° azimuth. | Ceiling effects in quiet (N = 2) and in noise (N = 1). | ||||

| Results reported for subjects with HTLs ≤ 80 dB HL at 125 & 250 Hz in IE. | |||||

| Simpson, McDermott, Dowell, Sucher, & Briggs, 2009 | 1 group: N = 5 adults | Words at 60-65 dB SPL in quiet; English | CI alone word scores significantly better than preoperative scores in quiet. (N = 3/5 bimodal & N = 2/5 CI+ bilateral HAs) | 3B II EF | 30/48 |

| Inclusion criteria: Word scores at 60-65 dBA between 0-30% in both ears | Sentences at 65 dB SPL in adaptive noise (SNR50). English | CI +HA/s scores significantly better than CI alone scores in quiet & noise. | |||

| Single loudspeaker at 0° azimuth. | No significant difference between CIHAi, CIHAc, CIHAs condition (N = 2) | ||||

| 2. Standard length (Reduced/shallow insertion depth) and/or medium length straight electrode array studies | |||||

| Study | Participants | Outcome measures | Postoperative findings | Level, grade strength, EV/EF | MD score |

| Kiefer et al., 2005 | 1 group: N = 13 adults | Words at 70 dB SPL in quiet | CI alone word scores significantly better than preoperative scores in quiet & noise. | 3C II EF | 24/48 |

| Inclusion criteria: Word scores at 70 dB ≤40% in both ears. | Sentences in quiet and noise (+10dB SNR) German | CI +HA/s sentences scores significantly better than CI alone scores in quiet & noise. | |||

| Single loudspeaker at 0° azimuth. | Results reported for participants who retained hearing (N = 11/13). | ||||

| Gstoettner et al., 2006 | 1 group: N = 23 adults | Words at 65 dB SPL; | Mean CI alone word scores were better than preoperative scores in quiet & noise. No statistical test preformed on data. | 4C II EF | 20/48 |

| Inclusion criteria Word scores at 70 dB ≤ 40% in best aided condition | Sentences at 65 dB SPL in adaptive noise (SNR50). German | Mean CI + Ipsilateral HA sentence scores were better than CI alone scores in quiet. No statistics. Ceiling effect for words in quiet | |||

| Single loudspeaker at 0° azimuth. | Results reported for participants with complete hg preservation (N = 8/23). | ||||

| Lorens et al, 2007 | 3 groups: | Words in quiet and noise (+10 dB SNR & +0 dB SNR). Polish | EAS group performed significantly better than traditional CI recipients for word & sentences. | 3B II EF | 27/48 |

| Partial deafness adults(n = 11) | Sentences in noise (+10dB SNR) | EAS group: CI + bilateral HAs word scores were significantly better than CI alone, HA alone & CI + Ipsilateral HA scores in noise. | |||

| Traditional CI adult recipients (n = 22) and NH adults (n = 20). | Single loudspeaker at 0° azimuth. | CI + Ipsilateral HA word scores were significantly better than CI alone, HA alone in noise. | |||

| Ceiling effect for words in quiet & sentences in noise. | |||||

| Skarzynski, Lorens, Piotrowska, & Anderson, 2007 | 1 group: N = 9 children | Words in quiet and noise (+10 dB SNR) Polish | Postoperative word scores* significantly better than preoperative scores with HAs in quiet. (n = 4/9). | 4C II EF | 23/48 |

| Inclusion criteria: “partial deafness” or significant residual hearing in low frequencies. | Single loudspeaker at 0° azimuth. | * Different devices used: 4/9 used residual hearing with CI. 4/9 used a DUET combined EAS stimulation device. 1/9 uses CI only. | |||

| Helbig, Baumann, Helbig, von Malsen-Waldkirch, & Gstoettner, 2008 | 1 group: N = 9 adults | Words at 70 dB SPL in quiet. | DUET (combined electric & acoustic stimulation device) sentences scores were significantly better than CI alone scores in noise (+10 dB & +5dB SNR). | 3B II EF & EV | 24/48 |

| Inclusion criteria:EAS recipients. | Sentences in quiet and in noise (+10dB, +5dB & 0 dB SNR). German. | APHAB questionnaire No significant difference reported with device upgrade from CI + Ipsilateral ITE to DUET | |||

| Single loudspeaker at 0° azimuth. | Ceiling effects for sentences in quiet & floor effects for sentences in noise (0 dB SNR). | ||||

| Abbreviated Profile of Hearing Aid Benefit (APHAB) questionnaire | |||||

| Gstoettner et al., 2008 | 1 group: N = 18 adults | Words at 70 dB SPL in quiet; German, Spanish & English | CI + Ipsilateral HA word & sentence scores were significantly better than preoperative scores with HAs in quiet & noise. | 4C II EF & EV | 24/48 |

| Inclusion criteria: Word scores ≤ 45% in best aided condition. | Sentences in quiet and noise (+10 dB SNR) | APHAB questionnaire significant postoperative improvement in subjective benefit compared to preoperative HA condition. | |||

| Single loudspeaker at 0° azimuth. | Speech testing results reported for 6 out of 18 participants who retained hearing and choose to wear amplification. | ||||

| Abbreviated Profile of Hearing Aid Benefit (APHAB) questionnaire. | |||||

| Skarzynski, Lorens, Piotrowska, & Podskarbi-Fayette, 2009 | N = 28 total 2 group N = 19 adults N = 9 children | Words at 60 dB SPL in quiet and noise ( +10 dB SNR) Polish | Word scores in best aided condition* were significantly better than preoperative scores with HAs in quiet & noise. | 3B II EF | 26/48 |

| Inclusion criteria: “partial deafness” | Single loudspeaker at 0° azimuth. | *Best aided condition: DUET + contralateral acoustic hearing or CI + natural bilateral acoustic hearing. | |||

| Podskarbi-Fayette, Pilka, & Skarzynski, 2010 | N = 18 total N = 11 adults N = 7 children | Monosyllabic words at 60 dB SPL in quiet and noise (+10 dB SNR). Polish | Word scores in best aided condition* were better than preoperative scores with HAs in quiet & noise. No statistical test performed on data. ( N = 11/18) | 4C II EF | 23/48 |

| Inclusion criteria: Residual hearing at levels in the low frequency range to 500Hz-1KHz | Single loudspeaker at 0° azimuthw | *Best aided condition: DUET + contralateral acoustic hearing (n = 7) or CI + natural bilateral acoustic hearing (n = 10) or CI alone (n = 1). | |||

| 3. Straight electroacoustic electrode array studies | |||||

| Study | Participants | Outcome measures | Key findings | Level, grade strength, EV/EF | MD score |

| Gantz, Turner, Gfeller, & Lowder, 2005 | 1 group N = 21 adults | Words at 70 dB SPL in quiet. Sentences in quiet and noise (+10 dB SNR). English | CI alone word scores were better than preoperative HA scores in quiet (N = 11/21). | 3C II EF | 24/48 |

| Inclusion criteria: Word scores at 70dB SPL between 10-60% (IE) & 80% (NIE) | Single loudspeaker at 0° azimuth | Mean CI +HAs SRT scores in noise were better than retrospectively matched group of traditional CI users. No statistics. | |||

| Buchener et al., 2009 | 1 group N = 22 adults | Sentences at 65 dB SPL in (+10 dB SNR) and adaptive noise (SNR50) | CI + Ipsilateral HA scores were significantly better than CI or HA alone in noise. | 3B II EF | 24/48 |

| Inclusion criteria Hybrid candidates ≤ 60dB up to 500Hz | Oral articulation evaluation | Information up to 300Hz significantly improved speech perception when combined with CI signal compared to CI alone. | |||

| Single loudspeaker at 0° azimuth | Significant correlation between preoperative articulation abilities & CI alone SRT scores. | ||||

| Gstoettner et al, 2009 | 1 group N = 9 adults | Words at 65 dB SPL in quiet. | CI + Ipsilateral HA scores were higher than CI alone or HA alone scores in quiet and noise. (N = 7/9) No statistics. | 4C II EF | 22/48 |

| Inclusion criteria Word scores at 65 dB SPL in quiet ≤ 40% best aided condition | Sentences in quiet and noise (+10 dB SNR). German | ||||

| Single loudspeaker at 0° azimuth | |||||

| Lenarz et al, 2009 | 2 groups N = 32 adults

|

Words at 65 dB SPL in quiet. | CI alone scores were significantly better than preoperative scores in quiet & noise. (N = 22/32) | 3C II EF | 28/48 |

| Sentences at 65 dB SPL in adaptive noise (SNR50). German | CI + Ipsilateral HA sentence scores were significantly better than CI alone & HA alone in noise. | ||||

| Single loudspeaker at 0° azimuth | Adults with hearing loss >30 years (n = 6) showed limited benefit in CI alone condition. Hearing loss of <30 years showed large EAS benefit. | ||||

| Substantial inter-individual differences in scores. | |||||

| Adunka, Pillsbury, Adunka, & Buchman, 2010 | 2 groups N = 20 total | Words in quiet. English | CI alone scores were better than preoperative scores in quiet. (N = 19/20) | 2B II EF | 32/48 |

| Inclusion criteria Word scores at 65 dB SPL in quiet ≤ 50% in best aided condition | Single loudspeaker at 0° azimuth

|

EAS electrode recipient group: CI + Ipsilateral HA word scores were significantly better than CI alone & HA alone in quiet. | |||

| The EAS electrode group word scores were significantly better than the conventional CI group in quiet. | |||||

| Dunn, Perreau, Gantz, & Tyler, 2010 | 1 group N = 11 total | The Recognition with Multiple Jammers speech-perception-in-noise test. English | Bilateral acoustic amplification with electric stimulation in implanted ear significantly better for sentence recognition compared to all other conditions (CI alone, HA alone, Bimodal) in spatially separated noise (N = 9/11). | 3B II EF | 28/48 |

| Inclusion criteria Hybrid recipients. | Everyday sounds localization test. Eight speaker array. | Significant difference in localization for the binaural HA conditions compared to monaural hearing aid conditions. | |||

| Gifford, Dorman, & Brown, 2010 | 4 groups: N = 64 adults 1. EAS array (n = 5) 2. Unilateral CI array (n = 25) 3. Bilateral CI array (n = 10) 4. Bimodal (n = 24) | R_SPACE 8 loudspeakers Adaptive speech test using spatially separated noise. English Frequency resolution at 500Hz by derived auditory filter shapes | EAS group (n = 5) combined SRT scores significantly better than Unilateral CI group (n = 25), Bilateral CI group (n = 10) & bimodal (CI +contralateral HA) group (n = 24). | 3B II EF | 27/48 |

| Normal hearers have significant better frequency selectivity than preoperative EAS participants (n = 5). | |||||

| Helbig et al., 2011 | 1 group N = 18 adults | Words at 65 dB SPL in quiet. Sentences in quiet and noise ( +10 dB SNR) German & Dutch | CI alone scores were significantly better than preoperative scores in quiet & noise. (N = 17/18) | 3B II EF & EV | 28/48 |

| Inclusion criteria Word scores at 65 dB SPL in quiet ≤ 50% in best aided condition | Single loudspeaker at 0° azimuth | CI + Ipsilateral HA speech scores were significantly higher than CI alone or HA alone scores in quiet & noise. | |||

| Abbreviated Profile of Hearing Aid Benefit (APHAB) questionnaire | APHAB questionnaire significant postoperative improvement in subjective benefit is reported compared to preoperative HA condition. | ||||

| Skarzynski et al., 2012 | 3 group N = 23 adults | Words at 60 dB SPL in quiet and noise ( +10 dB SNR) Polish | Postoperative word scores were better than preoperative scores with HAs in quiet & noise for “Hybrid” candidate group (EC group n = 7/7 & EAS group 5/7 reported at 13 months). | 3C II EF | 27/48 |

| Hybrid candidates (EC & EAS) and Conventional CI candidate (ES). | Single loudspeaker at 0° azimuth. | *Postoperative aided device condition not reported. | |||

Abbreviations: APHAB=Abbreviated Profile of Hearing Aid Benefit questionnaire; BTE= Behind the ear; CI: Cochlear implant; dB = decibel; EAS= Electric-acoustic Stimulation; EC=Electrical complement; EF=Efficacious or laboratory based measures; ES=Electrical stimulation; EV= EffectiVeness or real world measures; HA = hearing aids; IE= Implanted ear; ITE=In the ear; HA= Hearing aids; MD score= MacDermid score; NIE = nonimplanted ear; NH= Normal hearing; PDCI=Partial deafness cochlear implantation; PTA= Pure tone Audiometry; PTT=Pure tone thresholds; SN= Sensorineural hearing loss; SNR = signal to noise ratio.

Preoperative Versus Postoperative Speech Perception

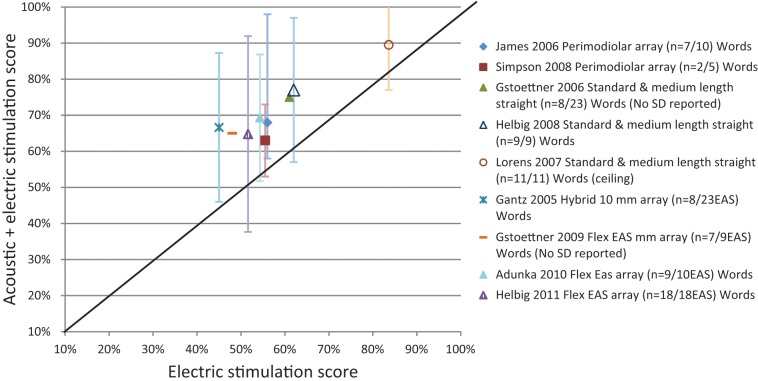

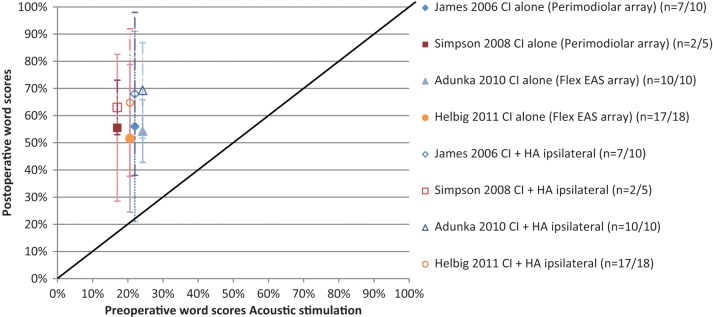

To evaluate the speech perception benefits resulting from combining acoustic amplification with electric stimulation, preoperative speech perception scores obtained using hearing aids (HAs) were compared to postoperative scores in the implanted ear using electric stimulation alone (CI alone) and combining acoustic and electric stimulation (CI +HAi). Results consistently show that speech perception, on average, was significantly higher postoperatively with electric stimulation alone (CI) when compared to best aided preoperative condition, and for combined acoustic and electric stimulation in the implanted ear (CI+HAi) as compared to scores for electric stimulation alone (CI). These findings are shown in Figure 2 for the various electrode arrays studies. In all studies, speech was presented from a single frontal loudspeaker (0° azimuth) at a fixed distance from the participant. Word perception scores from listening in quiet are shown, with averaged results from each study calculated and represented by a data point.

Figure 2.

Preoperative versus postoperative word scores in quiet (Mean ± SD) in implanted ear for various array studies.

Closed symbols represent electric stimulation alone. Open symbols represent combined acoustic & electric stimulation.

Figure 2 shows speech performance in the preoperative best-aided condition (HAs) compared with postoperative monaural listening scores obtained for the implanted ear using electric stimulation alone (CI only) represented as the closed symbols. Any increase in measured performance is assumed to represent primarily benefit as a direct result from implantation. The graph shows that all studies, regardless of array used, reported significantly better mean word perception scores for postoperative electric stimulation alone (CI only) as compared to preoperatively (HAs) in quiet. The increase in word scores ranged from 30% to 39% across the various electrode studies. It could be argued, that testing this condition provides evidence to support this intervention for individuals with severe high frequency sensorineural hearing losses, even when there is complete hearing loss associated with the implantation.

Figure 2 also compares speech performance in the preoperative best aided condition (HAs) as compared with the unilateral listening condition in the implanted ear using combined acoustic and electric stimulation (CI+HAi). Data was taken from the same studies and represented as open symbols. Any increase in measured post implantation performance represents primarily benefit from use of preserved low frequency residual hearing through combining acoustic and electric stimulation following cochlear implantation. On average, word scores in quiet we significantly better postoperatively in the implanted ear combining acoustic and electric stimulation (CI+HAi) as compared to preoperatively (HAs). Postoperative EAS benefit ranged from 43.8% to 49% in word scores. The post implantation speech results show that there is benefit combining acoustic and electric stimulation.

Across all studies eligible for inclusion, results consistently show that speech perception, on average, was enhanced postoperatively with electric stimulation alone compared to preoperative condition. Greater postoperative advantage was evident when combining acoustic and electric stimulation in the implanted ear than for use of electric stimulation alone. It should also be noted that considerable individual variability was reported across these studies, with the majority of individuals showing benefit, whereas a small number showed no difference in preoperative versus postoperative performance. Age and duration of hearing loss accounted for significant variance and had a negative impact on speech performance (Gantz et al., 2009; Lenarz et al., 2009). A significant correlation was also found between preoperative articulation abilities and postoperative CI alone Speech Reception Threshold (SRT) sentence scores (Buchener et al., 2009).

Acoustic and Electric Stimulation Speech Perception Benefit in the Implanted Ear

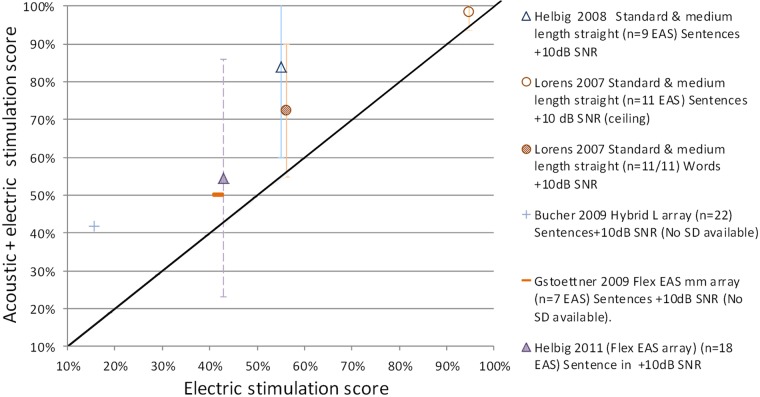

A further question is the degree of benefit that can be gained from combining acoustic and electric stimulation when residual hearing is preserved following implantation? To investigate this, several studies have compared speech perception in the implanted ear using electric stimulation only (CI) with speech perception using combined acoustic and electric stimulation (CI+HAi) in quiet (Figure 3a) and in noise (Figure 3b). Speech perception scores for testing in quiet and noise are shown, with averaged results from each study calculated and represented by a data point.

Figure 3a.

EAS benefit for implanted ear in Quiet: Electric only stimulation (CI) versus Acoustic & Electric Stimulation (CI+HAi) word scores (Mean ± SD) for various electrode array studies.

Figure 3b.

EAS benefit for implanted ear in Noise: Electric only stimulation (CI) versus Acoustic & Electric Stimulation (CI+HAi) scores (Mean ± SD) for various electrode array studies.

As shown, speech perception scores for the implanted ear were consistently higher for the combined acoustic and electric stimulation as compared to electric stimulation alone, particularly for speech perception tests in noise. Figure 3a shows that in quiet, benefit ranged from 6% to 15% for word perception scores. Five out of the nine electrode array studies reported statistically significant benefit on average. Figure 3b shows that in noise (+10dB SNR) this benefit ranged from 4% to 29% for sentence perception scores. Five out of six studies reported statistically significant benefit, on average. The one study that did not reach statistical significance had reached ceiling affect.

Across all studies, speech perception scores were higher postoperatively in the implanted ear when using combining acoustic and electric stimulation (CI+HAi) as compared to electric stimulation alone (CI), on average, in both quiet and noise. The addition of acoustic stimulation potentially provides low frequency information to enhance the perception of F0 voicing cues (timing and presence), envelope periodicity cues, low-frequency segmental phonetic cues (nasal resonant, F1 onset and shape of transitions) for improved speech perception (Brown & Bacon, 2009; Kong & Carlyon, 2007; Qin & Oxenham, 2006; Zhang, Dorman, & Spahr, 2010).

Binaural Hearing Benefits

Preservation of low frequency hearing in the implanted ear also provides potential benefits through enabling provision of acoustic stimulation to both ears. Five out of the 18 inclusion studies examined the impact of utilizing both ears for binaural benefit in speech perception and localization. Three studies that evaluated word performance in quiet (Gantz et al., 2005; Lorens et al., 2008; Simpson et al., 2009) reported higher speech perception scores in the binaural condition (CI +HAi + HAc opposite ear) compared to the monaural condition (CI +HAi) on average, however, the studies did not reach statistical significance. Two studies evaluated sentence perception using an adaptive test with spatially separated target speech and noise sources (Dunn et al., 2010; Gifford et al., 2010). Binaural hearing did however provide a statistically significant benefit for sentence perception in spatially separated speech and noise sources. The binaural improvement for speech reception thresholds (SRTs) was about 3dB in both studies. Dunn and colleagues (2010) proposed that the potential advantage lies in the utilization of two similar acoustic signals with identical sound processing being presented to the central auditory system ear. One study to date that reported on horizontal localization found a significant difference in localization performance for the binaural condition compared to the monaural or bimodal condition (Dunn et al., 2010). The author concluded that the bilateral hearing aids providing similar processing from both ears improved the perception of audible low frequency input below 800 Hz, where primarily interaural time level differences (ITD) cues help to localize the sound source. The ability to localize the sounds was dependent on participants being able to perceive sounds in both ears with the acoustic amplification provided by the hearing aids, and independent of whether there was electrical stimulation or not.

Only a small number of studies have utilized test arrangements to evaluate binaural benefit derived through the provision of acoustic stimulation to both ears. The review highlights the need for the inclusion of more studies investigating and using outcomes measures that better quantify binaural advantages such as; spatially separated speech and noise, localization, and also functional benefit in everyday life or Effective (EV) evidence, rather than traditional outcome measures utilized in standard cochlear implantation.

Q3. What clinical fitting practices have been developed for devices that combine acoustic and electric stimulation?

EAS outcome studies report utilizing a range of fitting practices for both the acoustic and electric stimulation. A summary of the 16 studies selected to address the third clinical question are shown in Tables 4.

Table 4.

A Summary of 16 EAS Articles That Provide Information on Fitting Practices for Devices That Combine Electric and Acoustic Stimulation.

| 1. Perimodiolar electrode array (“Advance off stylet’ technique) studies | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Acoustic parameters | Electric parameters | Key findings | Level, grade strength, EV/EF | MD score |

| Fraysse et al., 2006 | N = 9 adults. | Sound Processor: ESPrit 3G, ACE, 20 channels, 8 maxima & Channel stimulation rate: 900 pps. | Equivalent speech scores for both programs, however, a trend for better scores in noise for restricted electrical bandwidth. | 3B II EF | 27/48 |

| Hearing aid: digital, high-power Phonak ITE | Programs used:

|

Considerable variability in individual performance. | |||

| Prescription: DSL(i/o) for thresholds ≤ 80 dB HL. Gain reduced > 80dB HL to improve loudness comfort & prevent feedback. Small vent used to remove occlusion discomfort where possible. | * 1 month each program (randomized) then both available. | Preference:

|

|||

| Simpson, McDermott, Dowell, Sucher, & Briggs, 2009 | N = 5 adults | Sound Processor: Freedom, 22channels, ACE, 900Hz, 8 maxima MP stimulation. | No significant difference with unrestricted or pitch-mapped programs for group words or SNRs cores (n = 5). | 3B II EF | 30/48 |

| Hearing aid : digital, high-power Phonak ITE/BTE | Programs used:

|

Participants using combined electric and acoustic stimulation in the implanted ear (n = 2) obtained best score with restricted electrical bandwidth programs. | |||

| Prescription: NAL-NL1 for thresholds ≤ 90 dB HL. Gain reduced to minimum > 90 dB HL (where hearing considered no longer “useful.” | ABA design (A pitch-matched 12 weeks, B conventional 12 weeks & A pitch matched for 2 weeks) | ||||

| Loudness balance task: 9 point loudness rating scale. Subjects listened to running speech at 60dBA to ensure “comfortable” & ICRA noise at 80dB A to ensure “loud but comfortable” | |||||

| 2. Standard length (Reduced/shallow insertion depth) and/or medium length straight electrode array studies | |||||

| Study | Acoustic parameters | Electric parameters | Key findings | Level, grade strength, EV/EF | MD score |

| Kiefer et al., 2005 | N = 13 adults | Sound Processor: TEMPO+, CIS strategy, 7-11 active channels available. Total stimulation rate: 18180 pps | 12/13 participants had best results with & chose the full frequency unrestricted electric bandwidth program (300 - 5500Hz) | 3C II EF | 24/48 |

| Hearing aid: nonlinear compression high-power ITE | Programs used:

|

1/13 obtained best score with restricted program (650Hz -5.500Hz ) | |||

| Prescription: Half gain rule in the 125 to 1000Hz range only. Standard fitting procedures not implemented as it produced “unsatisfactory results where high levels of amplification in mid-high frequency region were either not possible, or desired by participants.” | Initially fit with unrestricted BW program in CI alone condition until stable thresholds reached. Then all 3 programs used for 2-3 weeks prior to testing. | Authors comment : “Overlap not detrimental” | |||

| Loudness balanced | Participants received longer exposure to full frequency range program versus others | ||||

| Loudness scaled and individual adjustments made when necessary. | |||||

| Skarzynski, Lorens, Piotrowska, & Anderson, 2007 | N = 9 children Acoustic: different devices used: 4/9 used residual hearing with CI. 4/9 used a DUET combined EAS stimulation device. 1/9 uses CI only. | Sound Processor: Duet EAS (which uses a TEMPO+ processor and a 2 channel hearing aid in one device.) 12 channels’ | Author’s comments: | 4C II EF | 23/48 |

| Pediatric Fitting: “The hearing aid component was fitted according to the required gain, using the half-gain rule (where the threshold of a given frequency is divided in half to obtain the predicted value). The recommended fitting procedures were followed and no special consideration had to be made for fitting the children.” | “The ci was programmed in such a way that there is no overlap with acoustic perception, so as to not interfere with this perception.” | Programs used:

|

|||

| “The children readily accepted the combination of electric and acoustic information. These results suggest that there are no special issues when fitting children their natural acoustic low frequency hearing” | |||||

| Gstoettner et al., 2008 | N = 18 adults | Sound Processor: TEMPO+, CIS strategy, Total stimulation rate: 18180 pps | 12/18 participants had sufficient residual hearing to utilize ipsilateral electric and acoustic stimulation. | 4C II EF & EV | 24/48 |

| Hearing aid: digital high-powered Oticon ITE: 2 channel, seven band instrument & peak gain 60dB & MPO 127 dB SPL | Programs used: | Author’s comments: | |||

| Prescription: Not reported. Amplification provided for all low frequencies where audiogram ≤ 80 dB HL. For > 80dB HL input into the software arbitrary 10dB HL threshold | 1. Unrestricted electric bandwidth (up to 7000 Hz) for 2 months. 2. Restricted electric bandwidth for Cross-over frequency determined by the frequency at which threshold >65 dB HL on unaided audiogram. | “Six however felt that additional acoustic input was either detrimental to their sound quality or insufficient in terms of amplification, or they disliked management of the two devices and thus choosing not to use EAS.” | |||

| * Aids fitted 2 months post-activation. | Initially used unrestricted BW program in CI alone condition for 2 months & then restricted program fit. | ||||

| Vermeire, Anderson, Flynn, & Van de Heyning, 2008 | N = 4 adults | Sound Processor: TEMPO+ sound processor | Acoustic signal: Highest level of performance in noise & subjective reports of listening effort (Visual Analogue Scale) when frequencies ≤ 120 dB HL amplified & 6dB gain (low boost). | 4C II EF | 26/48 |

| Hearing aid: digital high-power Oticon ITE: Vent as large as possible to reduce occlusion effect. | Programs used:.

|

Electric signal: “Best results” in noise ( +15 & +10 SNR) with restricted electrical bandwidth program. | |||

| Prescription: Half gain rule & VoiceFinder alogorithm enabled which adjusts gain based on input signal. | Fitting: Participants initially fit with unrestricted BW program for 2 months. Then 30 minute adjustment period with each listening program & 1 practice list for each section. | 3/4 subjects with steeply sloping losses performed better with restricted electric bandwidth program & low boost to gain. One subject with flat severe loss performed better with unrestricted program. NSD effects for any condition on VAS scale. | |||

HA Programs used:

| |||||

| Helbig, Baumann, Helbig, von Malsen-Waldkirch, & Gstoettner, 2008 | N = 9 adults | Sound Processor: Duet EAS | Initially, 9 participants wore ITE but then 6 rejected it. | 3B II EF & EV | 24/48 |

| Acoustic via ITE and/or DUET EAS. | Programs used: Not reported | Author’s comment: | |||

| Prescription: Half gain rule & optimized according to subject’s responses. | “Despite the fact that an increase in speech perception was measurable due to acoustic amplification, this lack of gain and wearing difficulties resulted in individuals discontinuing to use the hearing aid before they could possibly perceive its benefit.” | ||||

| Fitting Issues: “The handling of two separate devices with different batteries and with different battery life spans is cumbersome and was reason enough to reject the use of the hearing aid. In patients with poorer low frequency thresholds, the ITE amplification was often insufficient, especially in the frequencies below 500Hz, which made fitting to provide sufficient gain very difficult.” | |||||

| Helbig & Baumann, 2009 | N = 15 adults | Sound Processor: Duet EAS | 11 of 15 subjects continued to use the combined DUET EAS sp . | 4C III EF | 13/48 |

| Acoustic: DUET 2 channel hearing aid with 4 trimming controllers: gain, LFS, volume and AGC. Gain at 500 Hz is adjustable between 27-42 dB HL. Peak gain is 52 dB HL at 1.6KHz. | Program used: | 4 of 15 participants rejected acoustic amplification due to limited benefit. | |||

| Prescription: Half gain rule set based on hearing threshold at 500Hz, | 1. Restricted electric bandwidth | “The “DUET user” group had residual hearing that was better than 75dB in the 500Hz frequency region or below. | |||

| Slope: “Low frequency slope (LFS) set between 0-18dB/octave. Subtraction of thresholds at 250 & 500 Hz. Half of this difference determines LFS. | Cross-over frequency determined by the frequency at which threshold is >65 dB HL on unaided audiogram. | The “non-user” group had a hearing loss of greater than 55dB HL at 125 Hz, 70 dB HL at 250 Hz and 98 dB HL at 500Hz. Acceptance of acoustic amplification was dependent on postoperative hearing thresholds” | |||

| Loudness balance: volume controller used for overall attenuation & ranges between 0-47 dB HL. Loudness scaling test performed at 500Hz (acoustic only) to determine setting of AGC threshold (input levels between 40-70 dB HL) | Fitting issues: Larger overlap of acoustic & electric “individuals with nearly normal hg in low frequency complained of “echo.” | ||||

| “Amplification peak at 1.6KHz led to problems of “distorted speech” dead regions in the area and lower regions activated.” | |||||

| Polak, Lorens, Helbig, McDonald, S., & Vermeire, 2010 | N = 24 adults | Sound Processor: Duet EAS | Study reported optimization of the parameters had a ‘strong effect” on speech performance, however, no statistical analysis of the results. | 4C III EF | 18/48 |

| Acoustic 2 channel hearing aid via DUET™ EAS processor | Programs used: | Parameters that had most impact on “overall” benefit were compression ratio & frequency where electrical stimulation started. No details on which of the parameters varied were optimal | |||

| Prescription: Initially Half gain rule plus individual adaption. | All restricted electric bandwidth programs: 200Hz from unaided audiogram at:

|

||||

| 3 Acoustic Parameters varied: | Fitting: Participants had 2 hr or 1day adjustment period with each listening program. | ||||

| LF slope: Th500-Th250/2, o, 18dB/octave Compression threshold: 40,55,70 dB Compression: ratio:1:1, 1:1.33, 1:2 | |||||

| Nopp & Polak, 2010 | Review paper reports on Polak study (2007) | Sound Processor: Duet EAS | On average, best speech understanding achieved when restricted electric bandwidth range set to the frequency at 65HL on the unaided audiogram. | 6D I II Review paper | * |

| N = 15 adults | Programs used:

|

78% subjects had poorer speech test scores with unrestricted electric bandwidth (full frequency range) program. | |||

| Acoustic via DUET™ EAS processor | Fitting: 1 day period for adjustment with each program | No data provided | |||

| Prescription: Half gain rule in the region of 125 to 1500Hz Hz, plus individual adaption (slope, AGC threshold, volume). | |||||

| Skarzynski & Lorens, 2010 | Design: N = 25 total 2 children groups: 1. Partial Deafness (n = 15) 2. Platinum HA users ( n = 10) | Sound Processor: Duet EAS with 8-11 active channels | Pediatric Fitting: “slight overlap with acoustic perception” | 4C II EF | 25/48 |

| Acoustic: Different devices used* | Program used: | * Individuals used either their natural acoustic low frequency hearing together with CI for everyday listening or used a DUET to amplify low frequencies and ci to amplify high frequencies in same ear (n = 22/25). | |||

| 1. Restricted electric bandwidth. Cross-over frequency determined by unaided audiogram. Low frequency ranged from 300 & 1000 Hz. The upper frequency was 8.5 kHz. | Participants with “nonfunctional partial preservation” used ci only (n = 3/25). | ||||

| Fitting: No extra-cochlea electrodes used. Determined by impedance telemetry & hearing sensation reports. | |||||

| 3. Straight electroacoustic electrode array studies | |||||

| Study | Acoustic parameters | Electric parameters | Key findings | Level, grade strength, EV/EF | MD score |

| Skarzynski, Lorens, Piotrowska, & Skarzynski, 2010 | Design: N = 95 total 2 group: Adults (n = 62) Children (n = 32) | Sound Processor: Duet EAS | 3 Groups: | 4C II EF | 20/48 |

| Acoustic: Different devices used | Programs: Not reported | A. Electrical component (EC) & nonamplified residual hearing for patients with normal or slightly elevated hearing losses (n = 30). | |||

| Individuals used either their natural acoustic low frequency hearing together with CI or used a DUET to amplify low frequencies and ci to amplify high frequencies in same ear or CI alone. | “The Skarzynski PDT Classification. A proposed classification system to assist with decision making process for amplification in the IE based on individual’s postoperative PTA at 125 Hz, 250 Hz & 500Hz. | B. Electric-acoustic stimulation (EAS) for patients with mild-to-severe loss (n = 43). | |||

| C. Electrical component (EC) only for patients with nonfunctional preservation or complete hg loss(n = 22). | |||||

| Gantz et al., 2009 | N = 87 adults | Sound Processor: All processors programmed with a standard CIS type of processing strategy, 6 channels available. | Author comments: | 3C II EF | 24/48 |

| Acoustic: Some used residual hearing & some used different devices: | Program used: | “In cases where a subject lost sufficient hearing so that amplification was not beneficial, the implant was programmed to correspond with the upper frequency cutoff of the contralateral ear as well as a broadband MAP.” | |||

| Prescription: NAL, Amplification provided up to a cutoff of useful residual hearing ≤ 90 dB HL. Broadband amplification applied to the contralateral ear for all subjects (NAL). 2 subjects preferred to use their residual low frequency hearing in both ears rather than hearing aids (both had mild to moderate hearing thresholds up to 750Hz in both ear). 2 used amplification only in contralateral ear (1 profound loss & 1 with complete loss.) | 1. Restricted electric bandwidth | Testing proceeded with the patient’s preferred map, which in all cases was the map with the abbreviated frequency allocation. | |||

| Cross-over frequency determined by frequency at which the threshold is ≥ 90 dB HL on unaided audiogram. Frequency range of 688 - 7938 or 1063 - 7938 Hz | |||||

| Lenarz et al., 2009 | N = 32 adults | Sound Processor: Freedom. 22 channels available | 25 participants used acoustic and electric stimulation in the implanted ear. 6 used CI alone in the implanted ear. 1 preferred to used residual hearing without a HA in the implanted ear. | 3C II EF | 28/48 |

| Acoustic: | Program used: | 8/32 participants reported basal most electrodes cause non-auditory sensations (pain or facial nerve stimulation) All sensations were resolved when electrodes deactivated. | |||

| ITE in IE: Amplification provided for all low frequencies up to the frequency point where audiogram was 80 dB HL. | 1. Restricted electric bandwidth. | ||||

| Recipients not using the HA were fitted with a standard CI program covering the low frequency range. | Cross-over frequency determined by frequency at which the threshold is ≥ 80 dB HL on unaided audiogram. | ||||

| Dunn, Perreau, Gantz, & Tyler, 2010 | Hearing aids: 15 channel Phonak ITE in ipsilateral ear and own BTE in contralateral ear to implant. | Sound Processor: Stimulation rates of up to 2400 Hz or 3500 Hz pulses per channel. 6 channels available. | Author comments: | 3C II EF | 28/48 |

| N = 11 adults | Program used: | “It appears when listeners have similar processing bilaterally through the use of bilateral hearing aids, listeners are able to take advantage of ITD cues, and the addition of the cochlear implant did not disrupt overall performance.’ | |||

| Prescription: | 1. Restricted electric bandwidth | ||||

| NAL-RP targets at all low frequencies bilaterally. | “Cochlear implant frequency response was set to supplement the subject’s acoustic hearing as determined by their audiogram.” | ||||

| Fitting: Real ear probe measurements to verify targets matched. | |||||

| Karsten et al, 2012 | N = 10 adults. | Sound Processor: Nucleus Hybrid Stimulation rates of 900 to 2500 Hz per channel, ACE processing strategy, 6-10 channels available. | Significantly better sentence scores in noise & subjective ratings for the “meet” non-overlapping and restricted bandwidth program. | 3B II EF | 30/48 |

| Prescription: NAL-NL1 targets | Program used: | No significant difference between programs for consonant recognition in quiet. | |||

| Fitting: Real-ear aided response measures to verify targets matched. | Restricted electric bandwidths: Cross-over frequency determined by frequency at which Electric and acoustic signal:

|

||||

| Loudness balancing using live speech | Fitting: Minimum of 11 days for adjustment with each program | ||||

Abbreviations: ACE= Advanced combination encoder; BTE= Behind the ear; CI: Cochlear implant; dB = decibel; CIS= Continuous interleaved sampling DSL = Desired Sensation Level; DSLi/o = Desired Sensation Level Input/Output; EF=Efficacious or laboratory based measures; EV= EffectiVeness or real world measures; HA = hearing aids; IE= Implanted ear; ITE=In the ear; HA= Hearing aids; MD= MacDermid score;MP= Monopolar stimulation; NAL RP = National Acoustic Laboratories-Revised Profound; NAL-NL1 = National acoustic laboratories-Non-linear 1; NIE = nonimplanted ear; NH= Normal hearing; PDCI=Partial deafness cochlear implantation; PTA= Pure tone Audiometry; PTT=Pure tone thresholds; SN= Sensorineural hearing loss; SNR = signal to noise ratio; PPS=Pulses per second.

Low Frequency Acoustic Amplification for Combined Acoustic and Electric Stimulation

The provision of acoustic amplification to the residual low frequency hearing preserved in the implanted ear in EAS studies has been either via an independently operating, commercially available digital in-the-ear hearing aid worn together with a behind-the-ear cochlear implant sound processor, or more recently, via EAS sound processors that deliver both acoustic and electrical stimulation through one integrated device. A wide range of conventional hearing aid prescriptive rules have been used in the studies to determine the amplification applied to the low frequency hearing in the implanted ear. Procedures for linear and nonlinear amplification such as: Half gain rule (Kiefer et al., 2005; Helbig et al., 2011), NAL-RP (Gantz & Turner, 2009; Dunn et al., 2010), DSL [I/O] (James et al., 2005; Fraysse et al., 2006) and NAL-NL1 (Karsten et al., 2012, Simpson et al., 2009) have been applied. The majority of studies apply a variation to these standard hearing aid fitting rationales for the high frequency region of the audiogram. In EAS device fittings the high frequency information is provided via electrical stimulation via the cochlear implant part, therefore, acoustic amplification is only provided up to the point where there is useful residual hearing or cut off where hearing is not measurable. This frequency up to which acoustic amplification is provided ranged from the frequencies where the hearing threshold exceeded 60 dB HL (Helbig et al., 2009; Nopp & Polak, 2010); exceeded 80 dB HL (Fraysse et al., 2006; Gstoettner et al., 2008; James et al., 2005; Lenarz et al., 2009) or 85 dB HL (Gantz et al., 2009; Simpson et al., 2009) on the individual’s audiogram. Practical considerations such as prevention of feedback and off- frequency listening, providing sufficient loudness, improving mould or loudness comfort and prolonging battery life, have also been reported as the reason for applying variation to the standard fitting rationale.

Only two studies reported on the broadband amplification applied to the contralateral ear for subjects in their study (Dunn et al., 2010; Gantz et al., 2009). Hearing aid verification using real ear probe measures to obtain objective measures of hearing aid fitting were reported in only two studies (Dunn et al., 2010; Vermeire, Anderson, Flynn, & Van de Heyning, 2008). Four studies report performing loudness balancing tasks between the electric and acoustic signal in the implanted ear. Loudness rating scales were used and adjustments to gain of hearing aid were made in response to individual feedback to live voice recorded speech or noise signals at different input levels (Karsten et al., 2012; Kiefer et al., 2005; Simpson et al., 2009). One study reported using a loudness scaling test performed at 500 Hz with the CI component deactivated to determine the setting of the AGC threshold (Helbig et al., 2011). The majority of the studies examined did not provide any information on whether a loudness balancing procedure between the electric and acoustic signal was used.

To date, two studies have evaluated the influence of different acoustic fitting parameters in the implanted ear on EAS outcomes (Vermeire et al., 2008; Polak, Lorens, Helbig, McDonald, & Vermeire, 2010). A small study by Vermeire and colleagues (2008) investigated the effect of two parameters; acoustic amplification (gain) and frequency range of amplification on speech performance, and subjective measure of benefit in 4 adults with a MED-EL M- electrode array and ITE hearing aid in the same ear. Results showed that additional low frequency gain (+6dB SPL in the low frequency range) and providing a wider frequency range for amplification (amplification up to thresholds of 120dB HL on the audiogram) provided the highest mean speech scores. Unfortunately, small participant numbers and limited listening experience of 30 min with each condition limit the strength of evidence and therefore the ability to support definitive conclusions. A second study by Polak et al. (2010) evaluated compression, compression threshold, and low frequency slope in the implanted ear (nonimplanted ear plugged) in 24 EAS participants. The authors reported that whilst all the parameters tested had an effect on speech perception in quiet and noise in the implanted ear, the parameters that had the most impact on overall benefit was the compression ratio and the frequency where electrical stimulation started. No statistical analysis of the results was reported to evaluate significance. Limited listening experience with each condition (2 hr or 1 day) also limits the strength of evidence from this study. Further investigation is required. A summary of hearing aid parameters used in EAS fittings is shown in Table 3.

Discontinuation of Low Frequency Acoustic Amplification Postoperatively

A number of studies report discontinuation or rejection of amplification in the implanted ear by some individuals. Typically, they can be divided into three groups. The first group consisted of individuals with a severe to profound hearing loss in the implanted ear (typically >80 dB HL across the frequency range) (Gantz et al., 2009; Gstoettner et al., 2008; Helbig et al., 2011; Simpson et al., 2009; Skarzynski et al., 2010) and without sufficient useful hearing for combined electric acoustic stimulation. It is not clear whether this is due to limited benefit or the “perceived” limited benefit by the recipient or as a result of practical issues concerning physical or loudness discomfort around fitting such losses, the inconvenience of wearing an additional component or a combination of factors. In addition Helbig et al. (2011) reported that “amplification was often reported to be insufficient, especially in the frequencies below 500Hz, which made fitting to provide sufficient gain very difficult.” A study by Helbig and Baumann (2009) examined the relationship between the postoperative pure tone audiometric thresholds in the implanted ear and wearer acceptance of a combined DUET EAS sound processor in 15 individuals. The study found that the 11 participants continued to use combined electric and acoustic stimulation, had residual hearing that was <75dB HL in the 500Hz frequency region or below. The remaining four participants who rejected acoustic amplification, had a hearing loss of greater than 55dB HL at 125 Hz, 70 dB HL at 250 Hz and 98 dB HL at 500Hz. The authors deduced that acceptance of acoustic amplification was dependent on postoperative hearing thresholds.

The second group that did not use amplification in the implanted ear consists of individual with significant amounts of residual hearing between 125-500Hz and PTA within the normal to mild range (Gantz et al., 2009; Lenarz et al., 2009; Skarzynski, Lorens, Piotrowska, & Anderson, 2007; Skarzynski & Lorens, 2010). This group did not require amplification as they could combine their natural acoustic hearing with electric stimulation. Skarzynski et al. (2010) proposed a classification system where electrical stimulation alone should be used in the implanted ear if low frequency hearing (125 Hz - 500 Hz) is ≤ 30 dB HL or ≥ 80 dB HL, and acoustic amplification considered in the implanted ear for all others.

The final group consists of individuals that report management and wearing of a supplementary acoustic instrument was cumbersome, inconvenient or contraindicated due to issues of the external ear canal such as acute external otitis media and was the reason to reject the use of the hearing aid (Gstoettner et al., 2008; Helbig, Baumann, Helbig, von Malsen-Waldkirch, & Gstoettner, 2008; Helbig et al., 2011) despite some having sufficient residual hearing to utilize and potentially benefit from ipsilateral electric and acoustic stimulation. Whilst the introduction of less cumbersome EAS sound processors which deliver both acoustic and electrical stimulation in one integrated device has helped reduce some of these wearing issues, there are still a number of participants that have discontinued amplification (Helbig et al., 2008; Helbig & Baumann, 2009). Further systematic investigation of fitting procedures aimed at maximizing outcomes for recipients of electric-acoustic devices could potentially facilitate the continued use of acoustic amplification following implantation, reduce individual variability with regard EAS benefit, increase recipient outcomes and wearer satisfaction.

Cochlear Implant Electric Fitting for Combined Acoustic and Electric Stimulation

To date, the electric parameters selected for electric stimulation in EAS applications are generally default settings determined by the cochlear implant system used. The default parameters utilized in studies include sound coding strategies, stimulation rates, number of channels. A summary of electric parameters used in EAS fittings is shown in Table 3.