Abstract

The current study investigates the impact of patient factors, surgical factors, and blood management on postoperative length of stay (LOS) in 516 patients who underwent primary total knee arthroplasty. Age, gender, type of anticoagulation, but not body mass index (BMI) were found to be highly significant predictors of an increased LOS. Allogeneic transfusion and the number of allogeneic units significantly increased LOS, whereas donation and/or transfusion of autologous blood did not. Hemoglobin levels preoperatively until 48 hours postoperatively were negatively correlated with LOS. After adjusting for confounding factors through Poisson regression, age (p = 0.001) and allogeneic blood transfusion (p = 0.002) were the most significant determinants of LOS. Avoiding allogeneic blood plays an essential role in reducing the overall length of stay after primary total knee arthroplasty.

Keywords: Allogeneic blood, anemia, autologous blood, blood management, length of stay, total knee arthroplasty, transfusion.

INTRODUCTION

The demand for total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is rapidly rising in light of the prevalence of arthritis and obesity in an ageing population[1, 2]. The number of total knee replacements increased by more than 275,000 procedures from 2004 to 2010 in the United States[3, 4].The Center for Disease Control (CDC) data on inpatient surgical procedures in the US presents a clear indication of the growing burden of total knee arthroplasty on overall health costs. A total of 719,000 TKA procedures were performed in 2010, more thandouble the number of total hip replacements [4]. At an average cost of 17,000 USD per procedure, this amounts for a total cost of more than 11.5 billion USD in one year [5].

In addition to the price of the implant, procedure costs are incurred through hospital stay and post-operative rehabilitation. The CDC reports average length of stay data according to age group and diagnosis for the years 1990, 2000, and 2010 [6]. The data includes total joint replacement under the broad category of osteoarthritis without differentiating between hip and knee procedures. Among patients between 45 and 64 years of age, the average length of stay decreased from 7.4 days in 1990, to 3.9 days in 2000 and 3.3 days in 2010. This duration increases with age to 9.3 days (1990), 4.7 days (2000), and 3.6 days (2010) for patients between 65 and 74 years old and reaches 10.5 days (1990), 4.7 days (2000), and 3.9 days (2010) among patients older than 85 years. The data also reveals statistically significant longer hospital stay for female patients as compared to males [6].

The projected increase to 3.5 million annual knee replacement procedures in the US by 2030 will considerably strain hospital facilities and resources [1].The total cost of these procedures is driven primarily by cost of joint implants, length of stay, and operating room time. Multimodal clinical pathways have emerged in an attempt to reduce length of stay without increasing post-operative complications. Such “fast-track” pathways focus on patient education, pre-operative discharge planning, pre-emptive pain and nausea management, and accelerated rehabilitation [7-10]. Several variables have associated with a longer duration of hospitalization, namely patient age, comorbidities and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, obesity, operative time, type of anesthesia, preoperative anemia, and blood transfusion [11-13]. Patient blood management addresses preoperative anemia and the associated risk of allogeneic transfusion, both of which are independently associated with adverse outcomes including increased postoperative mortality and morbidity. As such, blood management is one of the most modifiable factors that might significantly impact length of stay [14-18]. The current study investigates the impact of patient factors, surgical factors, and blood management on postoperative length of stay in patients who underwent primary total knee arthroplasty.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We conducted a retrospective review of 516 primary total knee replacement procedures performed between 2009 and 2012 by one of five surgeons at the authors’ institution. Patients with a preoperative hemoglobin (Hb) level below 13.5 g/dL were considered anemic and were advised to donate one unit of autologous blood 7 to 15 days prior to the date of surgery. No patient was allowed to donate less than 7 days prior to the procedure and daily oral iron supplementation was given until the day of the surgery. Patients received allogeneic transfusions if their hemoglobin level dropped below 8.0 g/dL and they displayed clinical symptoms of anemia (tachycardia and/or hypotension) despite an intravenous fluid bolus. The decision to transfuse autologous blood was made at the discretion of the anesthesiologist and medical attending, and strict transfusion guidelines were not enforced.

Gender, age, body mass index (BMI), preoperative Hb, autologous blood donation, number of autologous transfusions, number of allogeneic transfusions, postoperative Hb levels until date of discharge, and in-house complications were recorded. Length of stay was calculated as the number of days in hospital from the day of surgery to the day of discharge, with day of surgery being day 0. Patients who underwent revision TKA, simultaneous bilateral TKA, and patients with bleeding disorders were excluded. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the authors’ institution.

All procedures were performed under hypotensive spinal–epidural anesthesia using a standardized medial parapatellar approach in TKA with the use of a tourniquet. 177 procedures were performed on males and 339 on females, with a mean age of 66 years at the time of the surgery (range: 27–90 years) and BMI of 30.3 kg/m2 (range: 12.7–74.7 kg/m2) (Table 1). Patients were divided by BMI into groups according to the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria; underweight (< 18.5 kg/m2), normal weight

Table 1.

Demographic factors of patients in the study.

| Factor | Number | Mean LOS | Median LOS [25th Percentile, 75th Percentile] | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | ||||

| < 60 | 129 (25.0%) | 3.7 ± 1.0 | 3 [3, 4] | 0.0017* |

| 60-69 | 197 (38.2%) | 3.8 ± 1.1 | 4 [3, 4] | |

| 70-79 | 144 (27.9%) | 4.1 ± 1.4 | 4 [3, 4] | |

| ≥ 80 | 46 (8.9%) | 4.4 ± 1.9 | 4 [3, 5] | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 177 (34.3%) | 3.7 ± 1.2 | 4 [3, 4] | 0.0008** |

| Female | 339 (65.7%) | 4.0 ± 1.3 | 4 [3, 4] | |

| Laterality | ||||

| Left | 265 (51.4%) | 4.0 ± 1.4 | 4 [3, 4] | 0.2344** |

| Right | 251 (48.6%) | 3.8 ± 1.1 | 4 [3, 4] | |

| BMI (kg/m2) † | ||||

| < 18.5 | 1 (0.2%) | 4 | 4 [4, 4] | 0.1012* |

| 18.5-24.9 | 91 (17.7%) | 3.7 ± 0.9 | 4 [3, 4] | |

| 25-29.9 | 194 (37.7%) | 4.0 ± 1.4 | 4 [3, 4] | |

| 30-34.9 | 123 (23.9%) | 3.8 ± 0.8 | 4 [3, 4] | |

| 35-39.9 | 73 (14.2%) | 4.0 ± 1.5 | 4 [3, 4] | |

| ≥ 40 | 32 (6.2%) | 4.6 ± 1.7 | 4 [4, 5] | |

Obtained from Kruskal-wallis test.

Obtained from Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Some missing data.

(18.5 kg/m2 to 24.9 kg/m2), over-weight (25 kg/m2 to 29.9 kg/m2) and obese (> 30 kg/m2). Patients with BMI greater than 30 kg/m2 were further subdivided into 3 groups, 30 to 34.9 kg/m2, 35 to 39.9 kg/m2, and 40 kg/m2 or more.

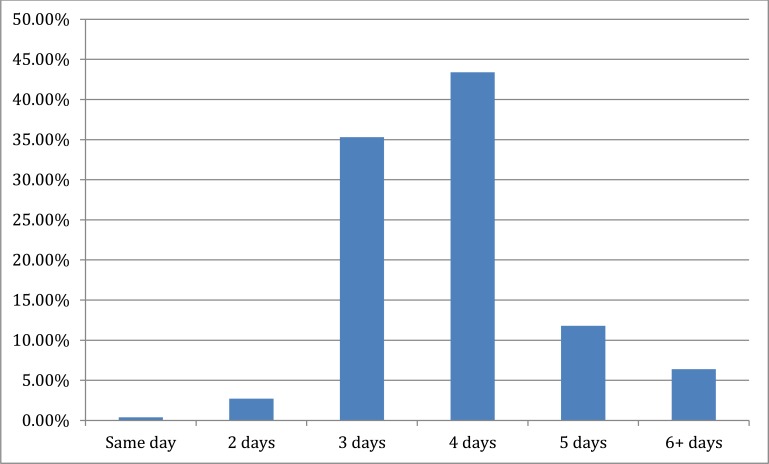

Descriptive statistics were used to illustrate patient demographics and health characteristics. Medians and the 25th and the 75th percentiles were calculated for length of stay, means and standard deviations were calculated for continuous variables, and frequency distributions for categorical variables. Inferential statistics (Kruskal-Wallis test, Wilcoxon Rank Sum, or Pearson’s Chi-square as appropriate) were used to assess statistical significance among study variables. Poisson regression was performed to identify significant factors influencing LOS. All analyses were conducted using SAS for Windows 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). All tests were two-sided and a critical p-value of 0.05 was set for all comparisons (Fig.1).

Fig. (1).

Patient distribution by length of stay following primary TKA.

RESULTS

The mean duration of hospital stay for all the patients was 3.9 days with a range of 1 to 13 days. The median LOS was 4 days with an inter-quartile range (i.e. 25th and 75th percentile) of 3 to 4 days. Tables 1-3 display the individual categories for each factor, the number of cases in each category and the mean length of stay.

Table 3.

Surgical factors of patients in the study.

| Factor | Number | Mean LOS | Median LOS [25th Percentile, 75th Percentile] | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgeon - TKA | ||||

| 1 | 17 (3.3%) | 3.1 ± 0.9 | 3 [3, 3] | <0.0001* |

| 2 | 357 (69.2%) | 4.0 ± 1.4 | 4 [3, 4] | |

| 3 | 32 (6.2%) | 3.7 ± 1.2 | 3 [3, 4] | |

| 4 | 8 (1.6%) | 4.0 ± 0.8 | 4 [4, 5] | |

| 5 | 102 (19.8%) | 3.7 ± 1.0 | 4 [3, 4] | |

| Day of operation | ||||

| Monday | 7 (1.4%) | 2.9 ± 1.1 | 3 [2, 4] | 0.0002* |

| Tuesday | 43 (8.3%) | 3.8 ± 1.5 | 3 [3, 4] | |

| Wednesday | 69 (13.4%) | 4.0 ± 1.3 | 4 [3, 4] | |

| Thursday | 97 (18.8%) | 3.8 ± 1.0 | 4 [3, 4] | |

| Friday | 230 (44.6%) | 4.1 ± 1.4 | 4 [3, 4] | |

| Saturday | 70 (13.6%) | 3.6 ± 0.8 | 4 [3, 4] | |

| Anticoagulation | ||||

| None | 4 (0.8%) | 4.3 ± 0.5 | 4 [4, 5] | <0.0001* |

| Aspirin | 45 (8.7%) | 3.4 ± 0.9 | 3 [3, 4] | |

| Aspirin + Coumadin | 73 (14.1%) | 4.0 ± 1.4 | 4 [3, 4] | |

| Aspirin + Coumadin + Lovenox/Heparin | 5 (1.0%) | 5.4 ± 2.1 | 5 [4, 5] | |

| Aspirin + Lovenox/Heparin | 1 (0.2%) | 3 | 3 [3, 3] | |

| Coumadin | 376 (72.9%) | 3.9 ± 1.2 | 4 [3, 4] | |

| Coumadin + Lovenox/Heparin | 11 (2.1%) | 5.4 ± 2.4 | 4 [4, 6] | |

| Lovenox | 1 (0.2%) | 3 | 3 [3, 3] | |

Obtained from Kruskal-wallis test.

Patient characteristics that were found to be highly significant predictors of an increased LOS when considered independently were age and gender, but not BMI or laterality. Surgical factors influencing length of stay included the weekday of surgery, the type of anticoagulation, and the orthopedic surgeon. In terms of blood management, transfusion of allogeneic blood and the number of allogeneic units transfused significantly increased length of stay, whereas donation and/or transfusion of autologous blood did not.Patient hemoglobin levels preoperatively until 48 hours after the procedurewere found to be negatively correlated with LOS.There is no correlation between length of stay and hemoglobin levels at discharge. When adjusted for the effect of confounding factors through Poisson regression, patient age (OR = 1.01, 95% CI = 1.001 to 1.01, p = 0.001)and allo-geneic blood transfusion (OR = 1.18, 95% CI = 1.03 to 1.36, p = 0.002) were found to be the most significant determi-nants of length of stay (Tables 1-3).

DISCUSSION

The growing demand for TKA highlights the need to reduce costs without affecting postoperative outcomes, prolonging rehabilitation, or increasing adverse events and readmission rates. Our findings suggest that patient age and blood management have the most significant impact on patients’ duration of hospital stay after primary unilateral TKA. LOS has been reported to increase by 10% to 13% with every decade added to the age of the patient as a function of increased co-morbidities and decreased physiologic fitness [17]. This is in accordance with other studies as the effect of age on postoperative hospital stay is well established in the literature [13, 19-21]. Males had a significantly shorter stay in the univariate analysis but the difference did not remain significant when corrected for other variables.

Several studies have identified the importance of blood management as a modifiable factor that influences postoperative hospital stay [17, 18, 20-22]. Guerin et al. concluded that the preoperative hemoglobin level was the only variable that independently predicts the need for blood transfusion after primary joint arthroplasty [22]. In a study of 2106 primary unilateral total knee procedures, Smith et al. found an increased length of stay of one day on average between patients with preoperative Hb less than 12 g/dL compared to patients with Hb greater than 13 g/dL [17].Furthermore, Husted et al. identified allogeneic blood transfusion as the most important predictor of discharge around the third day of admission in a fast-track streamlined practice. The data showed a three-fold increased risk of staying more than 3 days whenever a patient is transfused [13]. Our data reveals that the transfusion of allogeneic blood has a greater effect on delaying patient discharge after primary TKA than gender, BMI, hemoglobin levels, anticoagulation protocol, surgeon, or day of surgery.

Variations in practice and rehabilitation protocols between countries have led to a wide disparity in postoperative hospital stay, ranging from 3.8 days in the United States [23], to 10 days in Germany [24], 24 days in France [25], and 35 days in Japan [26].The elective nature of TKA makes it possible to anticipate significant blood loss and individualize patient blood management. Simple measures such as optimizing patient preoperative status and enforcing strict allogeneic transfusion guidelines can significantly reduce morbidity, costs, and length of stay. Correcting preoperative anemia with iron and/or erythropoiesis-stimulating agents can help to decrease transfusion risk. Tranexamic acid [27], fibrin sealants [28, 29], blood salvage [30], and hypotensive anesthesia have proven to be safe and efficient in reducing operative blood loss and exposure to allogeneic blood [31].Autologous blood remains one of the safest alternatives to minimize exposure to allogeneic blood [32].Targeting anemic patients for preoperative autologous blood donation was shown to decrease transfusion risk in primary TKA with minimal wastage rates and cost [33]. Donation or transfusion of one autologous blood unit showed no correlation with longer hospital stay in this TKA cohort.

This study is limited by its retrospective nature which restricted obtaining pooled preoperative knee scores and ASA scores in addition to information on complications and readmission rates. Moreover, the threshold of 13.5 g/dL employed in this study for autologous blood donation is based on previous data from our institution on maximizing the benefit and reducing number of units wasted in TKA [33]. Most studies in the literature rely on the World Health Organization definition for anemia of Hb level less than 13 g/dL in males and 12 g/dL in females.

CONCLUSION

Adapting to the increased demand for total knee arthroplasty requiresa cost-effective approach that prioritizes patient safety. Inevitably, higher costs are incurred when patients remain in hospital for longer periods of time after the procedure. Although the difference in the mean length of stay between categories of significant variables is sometimes less than half a day and may not be significant in an individual patient, it would give rise to a significant cost over time. Preoperative optimization of Hb level, employing blood management techniques, and adopting strict transfusion criteria can significantly reduce hospital stay and overall cost of total knee replacement procedures.

Table 2.

The effect of hemoglobin level and blood transfusions on LOS.

| Factor | Number | Mean LOS | Median LOS | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative Hb (g/dL) | ||||

| < 12 | 61 (12%) | 4.2 ± 1.5 | 4 [3, 4] | 0.0013* |

| 12-12.9 | 111 (22%) | 3.9 ± 0.8 | 4 [3, 4] | |

| 13-13.9 | 151 (30%) | 4.0 ± 1.3 | 4 [3, 4] | |

| ≥ 14 | 193 (37%) | 3.7 ± 1.3 | 4 [3, 4] | |

| Postoperative Hb (g/dL) | ||||

| < 12 | 261 (51%) | 4.0 ± 1.2 | 4 [3, 4] | 0.001* |

| 12-12.9 | 145 (28%) | 3.9 ± 1.5 | 4 [3, 4] | |

| 13-13.9 | 77 (15%) | 3.7 ± 1.3 | 3 [3, 4] | |

| ≥ 14 | 33 (6%) | 3.5 ± 0.9 | 3 [3, 4] | |

| Autologous blood | ||||

| Did not donate | 424 (82.2%) | 3.9 ± 1.3 | 4 [3, 4] | 0.8591** |

| Donate | 92 (17.8%) | 3.9 ± 0.9 | 4 [3, 4] | |

| Blood transfusion | ||||

| None | 413 (80.0%) | 3.8 ± 1.1 | 4 [3, 4] | 0.003* |

| Autologous only | 41 (7.9%) | 3.8 ± 0.8 | 4 [3, 4] | |

| Allogeneic only | 55 (10.7%) | 4.7 ± 2.1 | 4 [3, 5] | |

| Autologous + Allogeneic | 7 (1.4%) | 5.0 ± 1.7 | 4 [4, 6] | |

| # of Allogeneic units received | ||||

| 0 | 454 (88.0%) | 3.8 ± 1.1 | 4 [3, 4] | 0.0014* |

| 1 | 47 (9.1%) | 4.7 ± 2.2 | 4 [3, 5] | |

| 2 | 11 (2.1%) | 4.3 ± 1.0 | 4 [4, 5] | |

| 3 | 3 (0.6%) | 7.0 ± 2.7 | 8 [4, 9] | |

| 4 | 1 (0.2%) | 3 | 3 [3, 3] | |

Obtained from Kruskal-wallis test.

Obtained from Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the surgeons of the blood preservation center at the Hospital for Special Surgery and its coordinator Michele Prigo for their efforts in enrolling patients in the Blood Preservation Center.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

All authors have read the manuscript, agree with its contents and have substantially contributed to it. No conflicts of interest regarding this submission arise for any of the authors of this submission.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(4):780–5. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.CDC Prevalence of doctor-diagnosed arthritis and arthritis-attributable activity limitation - United States. 2007 2009. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59 (39):1261–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacobs JJ. United States bone and joint decade: the burden of musculoskeletal diseases in the United States. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 4.CDC/NCHS National Hospital Discharge Survey 2010, Available from: http://www.dc.gov/nchs/nhds/nhds_products.htm Accessed September. 2013.

- 5.Cost of hospital discharges with common hospital operating room procedures in nonfederal community hospitals by age and selected principal procedure: United States. selected years 2000-2010. . Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/2012/115.pdf. Accessed. 2013;September 3 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Average length of stay in nonfederal short-stay hospitals by sex.age.and selected first-listed diagnosis United States., selected years 1990 through 2009 2010. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus/contents2012.htm. Accessed 2013, September

- 7.Ayalon O, Liu S, Flics S, Cahill J, Juliano K, Cornell CN. A multimodal clinical pathway can reduce length of stay after total knee arthroplasty. HSS J. 2011;7(1):9–15. doi: 10.1007/s11420-010-9164-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones S, Alnaib M, Kokkinakis M, Wilkinson M, St Clair Gibson A, Kader D. Pre-operative patient education reduces length of stay after knee joint arthroplasty. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2011;93(1):71–5. doi: 10.1308/003588410X12771863936765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kehlet H. Fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty. Lancet. 2013;381(9878):1600–2. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61003-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khan F, Ng L, Gonzalez S, Hale T, Turner-Stokes L. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation programmes following joint replacement at the hip and knee in chronic arthropathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD004957. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004957.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Batsis JA, Naessens JM, Keegan MT, Huddleston PM, Wagie AE, Huddleston JM. Body mass index and the impact on hospital resource use in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2010;25(8):1250–7 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Husted H, Hansen HC, Holm G , et al. What determines length of stay after total hip and knee arthroplasty?A nationwide study in Denmark.. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2010;130(2):263–8. doi: 10.1007/s00402-009-0940-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Husted H, Holm G, Jacobsen S. Predictors of length of stay and patient satisfaction after hip and knee replacement surgery: fast-track experience in 712 patients. Acta Orthop. 2008;79(2):168–73. doi: 10.1080/17453670710014941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spahn DR. Anemia and patient blood management in hip and knee surgery: a systematic review of the literature. Anesthesiology. 2010;113(2):482–95. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181e08e97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goodnough LT, Shander A. Patient blood management. Anesthesiology. 2012;116(6):1367–76. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318254d1a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bozic KJ, Lau E, Kurtz S , et al. Patient-related risk factors for periprosthetic joint infection and postoperative mortality following total hip arthroplasty in medicare patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(9):794–800. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.00072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith ID, Elton R, Ballantyne JA, Brenkel IJ. Pre-operative predictors of the length of hospital stay in total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90(11):1435–40. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B11.20687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jans O, Jorgensen C, Kehlet H, Johansson PI. Lundbeck Foundation Centre for Fast-track Hip and Knee Replacement Collaborative Group.Role of preoperative anemia for risk of transfusion and postoperative morbidity in fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty. Transfusion. 2014;54(3):717–26. doi: 10.1111/trf.12332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forrest G, Fuchs M, Gutierrez A, Girardy J. Factors affecting length of stay and need for rehabilitation after hip and knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13(2):186–90. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(98)90097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jonas SC, Smith HK, Blair PS, Dacombe P, Weale AE. Factors influencing length of stay following primary total knee replacement in a UK specialist orthopaedic centre. Knee. 2012;20(5):310–5. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2012.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raut S, Mertes SC, Muniz-Terrera G, Khanduja V. Factors associated with prolonged length of stay following a total knee replacement in patients aged over 75. Int Orthop. 2012;36(8):1601–8. doi: 10.1007/s00264-012-1538-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guerin S, Collins C, Kapoor H, McClean I, Collins D. Blood transfusion requirement prediction in patients undergoing primary total hip and knee arthroplasty. Transfus Med. 2007;17(1):37–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3148.2006.00698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vorhies JS, Wang Y, Herndon JH, Maloney WJ, Huddleston JI. Decreased length of stay after TKA is not associated with increased readmission rates in a national medicare sample. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(1):166–71. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-1957-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kramer S, Wenk M, Fischer G, Mollmann M, Popping DM. Continuous spinal anesthesia versus continuous femoral nerve block for elective total knee replacement. Minerva Anestesiol. 2011;77(4):394–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dauty M, Smitt X, Menu P, Dubois C. Which factors affect the duration of inpatient rehabilitation after total knee arthroplasty in the absence of complications?. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2009;52(3):234–45. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Husted H, Jensen CM, Solgaard S, Kehlet H. Reduced length of stay following hip and knee arthroplasty in Denmark 2000-2009: from research to implementation. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2012;132(1):101–4. doi: 10.1007/s00402-011-1396-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alshryda S, Sarda P, Sukeik M, Nargol A, Blenkinsopp J, Mason JM. Tranexamic acid in total knee replacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(12):1577–85. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B12.26989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levy O, Martinowitz U, Oran A, Tauber C, Horoszowski H. The use of fibrin tissue adhesive to reduce blood loss and the need for blood transfusion after total knee arthroplasty.A prospecive.rand-omized., multicenter study. J Bone Joint Surg Am . 1999; 81(11):1580–8. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199911000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carless PA, Henry DA, Anthony DM. Fibrin sealant use for minimising peri-operative allogeneic blood transfusion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;2:CD004171. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carless PA, Henry DA, Moxey AJ, O'Connell D, Brown T, Fergusson DA. Cell salvage for minimising perioperative allogeneic blood transfusion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;4:CD001888. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001888.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tenholder M, Cushner FD. Intraoperative blood management in joint replacement surgery. Orthopedics. 2004;27(6 Suppl ):s663–8. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-20040602-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Henry DA, Carless PA, Moxey AJ , et al. Pre-operative autologous donation for minimising perioperative allogeneic blood transfusion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(2):CD003602. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boettner F KS, Altneu E, Bou Monsef J, King E, Sculco T. Nonanemic patients do not benefit from autologous blood donation before total knee replacement. HSSJ. 2011;7:141–4. doi: 10.1007/s11420-011-9200-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]