Dear Sir,

Color Doppler ultrasonography (CDUS) is a sensitive, noninvasive technique, to diagnose vasculitis of the temporal artery and the large vessels [Diamantopoulos et al. 2013]. In temporal arteritis, the halo sign (hypoechoic, dark area around the lumen of the temporal artery) seems to disappear within 2 days to 6 months after the start of treatment with corticosteroids [Santoro et al. 2013; Schmidt, 2000; De Miguel et al. 2012; Perez Lopez et al. 2009].

Our patient, a 66-year-old woman with no previous medical history, presented with new-onset headache and fatigue. Clinical examination revealed generalized scalp tenderness, swelling and pain over the temporal artery. Both temporal arteries were thickened and tender on examination. The laboratory work-up revealed an increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 59 mm/h (normal rate < 20 mm/h) and C-reactive protein of 73 mg/l (normal range < 5 mg/l).

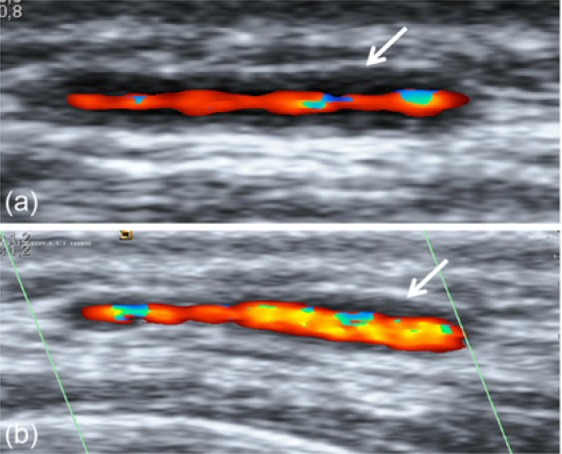

The patient underwent a CDUS examination. The typical halo sign in the whole length of both temporal arteries was detected (Figure 1(a)). The maximum halo thickness was measured to be 1 mm. No signs of inflammation were observed in subclavian, carotid and axillary arteries.

Figure 1.

Left parietal branch of temporal artery in a patient with giant cell arteritis: (a) before the introduction of corticosteroids; (b) 7 months after initiation of treatment. Halo sign is visible in both images (white arrows).

A biopsy of the left frontal branch of the temporal artery revealed lymphocytic infiltration and giant cells in the vessel wall compatible with the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis (GCA). The patient started with 40 mg prednisolone and went into clinical remission with normalization of the inflammation markers and disappearance of symptoms during the first 4 weeks of treatment.

Seven months later the patient was re-evaluated by CDUS. The halo sign in the left parietal branch of the temporal artery was detectable, but to a lower degree (maximum halo thickness 0.6 mm, Figure 1(b)). During the 7 months, no relapse of vasculitis had been observed. The inflammation markers were still normal and no symptoms or signs of active GCA were reported by the patient. At this period (7 months) the patient was treated with 7.5 mg prednisolone.

Discussion

In diverse studies, the halo sign seems to disappear within a period of 2 days to 6 months after the start of treatment with corticosteroids [Santoro et al. 2013; De Miguel et al. 2012; Perez Lopez et al. 2009]. In addition, the halo sign reappears in GCA patients suffering a flare [De Miguel et al. 2012].

Our experience regarding the duration of halo sign in GCA patients is that the halo sign persists and seldom disappears before 2 months in the majority of patients. As demonstrated in this case, the halo sign could last as long as 7 months. Our patient was in remission during this period and no clinical relapses were observed. Thus, the halo sign could not be attributed to a flare.

Biopsy of the temporal artery is considered the gold standard in the diagnostics of GCA. Nonetheless, the likelihood of getting a positive biopsy reduces significantly two weeks after the initiation of corticosteroids [De Miguel et al. 2012]. Halo sign seems to persist up to 7 months in GCA patients. Thus, CDUS may be useful for the evaluation of patients suspected to have GCA in whom biopsy has been negative or has not been performed and they have been in prolonged treatment with corticosteroids. In addition, CDUS could be valuable during the follow up of GCA patients by monitoring changes of the halo thickness, hence being supplementary to the clinical evaluation.

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Contributor Information

Andreas P. Diamantopoulos, Department of Rheumatology, Hospital of Southern Norway Trust, Service box 416, 4604 Kristiansand, Norway

Geirmund Myklebust, Department of Rheumatology, Hospital of Southern Norway Trust Kristiansand, Norway.

References

- De Miguel E., Roxo A., Castillo C., Peiteado D., Villalba A., Martin-Mola E. (2012) The utility and sensitivity of colour Doppler ultrasound in monitoring changes in giant cell arteritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 30: S34–S38 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamantopoulos A., Haugeberg G., Hetland H., Soldal D., Bie R., Myklebust G. (2013) The diagnostic value of color Doppler ultrasonography of temporal arteries and large vessels in giant cell arteritis: A consecutive case series. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken), in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez Lopez J., Solans Laque R., Bosch Gil J., Molina Cateriano C., Huguet Redecilla P., Vilardell Tarres M. (2009) Colour-duplex ultrasonography of the temporal and ophthalmic arteries in the diagnosis and follow-up of giant cell arteritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 27: S77–S82 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoro L., D’Onofrio F., Bernardi S., Gremese E., Ferraccioli G., Santoliquido A. (2013) Temporal ultrasonography findings in temporal arteritis: early disappearance of halo sign after only 2 days of steroid treatment. Rheumatology (Oxford) 52: 622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt W. (2000) Doppler ultrasonography in the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 18: S40–S42 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]