Abstract

Hydrogen sulfide has recently been found decreased in chronic kidney disease. Here we determined the effect and underlying mechanisms of hydrogen sulfide on a rat model of unilateral ureteral obstruction. Compared with normal rats, obstructive injury decreased the plasma hydrogen sulfide level. Cystathionine-β-synthase, a hydrogen sulfide-producing enzyme, was dramatically reduced in the ureteral obstructed kidney, but another enzyme cystathionine-γ-lyase was increased. A hydrogen sulfide donor (sodium hydrogen sulfide) inhibited renal fibrosis by attenuating the production of collagen, extracellular matrix, and the expression of α-smooth muscle actin. Meanwhile, the infiltration of macrophages and the expression of inflammatory cytokines including interleukin-1β, tumor necrosis factor-α, and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in the kidney were also decreased. In cultured kidney fibroblasts, a hydrogen sulfide donor inhibited the cell proliferation by reducing DNA synthesis and downregulating the expressions of proliferation-related proteins including proliferating cell nuclear antigen and c-Myc. Further, the hydrogen sulfide donor blocked the differentiation of quiescent renal fibroblasts to myofibroblasts by inhibiting the transforming growth factor-β1-Smad and mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways. Thus, low doses of hydrogen sulfide or its releasing compounds may have therapeutic potentials in treating chronic kidney disease.

Keywords: cell signaling, chronic inflammation, chronic renal disease

Tubulointerstitial fibrosis is the final common pathway to chronic kidney diseases (CKD).1 Pathologically, renal fibrosis manifests as the formation of myofibloblasts and the deposition of extracellular matrix proteins in the renal interstitium.2 The mechanisms of renal fibrosis have not been fully elucidated and effective drugs are still scarce. Renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system is one of the main culprits of renal fibrogenesis, and renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors remain the first-line drugs in fighting renal fibrosis.3 However, the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors may deteriorate renal function and cause hyperpotassemia when serum creatinine rises above 3 mg/dl.4 New antifibrotic agents are therefore needed to expand therapeutic options and decrease side effects, which is especially important for azotemia patients.

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) represents the third gasotransmitter along with nitric oxide and carbon monoxide.5 It is generated by cystathionine-γ-lyase (CSE), cystathionine-β-synthase (CBS), and 3-mercaptopyruvate sulphurtransferase. CBS and CSE are enriched in renal proximal tubules and produce H2S in kidney in a combined way.6 H2S plays various physiological and pathological roles in the kidney. For instance, it exhibits diuretic, natriuretic, and kaliuretic properties by increasing glomerular filtration rate and functions as an oxygen sensor in the renal medulla.6, 7 Recently, it was reported that plasma H2S level was decreased in 5/6 nephrectomy rat and uremia patients,8, 9 suggesting that uremic toxin of CKD impairs the production of endogenous H2S.

Notably, the biological functions of H2S in CKD are not fully understood. Heterozygous cbs−/− mice with unilateral nephretomy, an animal model of CKD, developed proteinuria and collagen deposition, and increased the expressions of matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9.10 Emerging evidence also demonstrates that H2S exhibits antifibrotic effects in the lung, heart, and liver.11, 12, 13 Furthermore, H2S bears some similarities to the other two gaseous molecules, nitric oxide and carbon monoxide, both of which protect the kidney from renal fibrosis.14, 15 Taken together, we hypothesize that H2S may attenuate renal fibrosis.

In this study, we examined the effect of H2S on unilateral ureteral obstructive (UUO) animal model and defined its safe and effective dosage range. Furthermore, we investigated the roles of H2S in renal fibroblast proliferation and differentiation. The potential mechanisms were also explored.

RESULTS

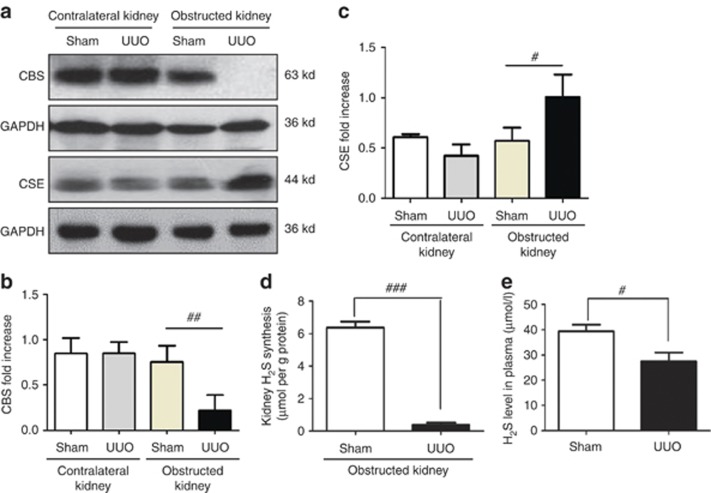

CBS expression and plasma H2S levels are decreased in the obstructed kidney

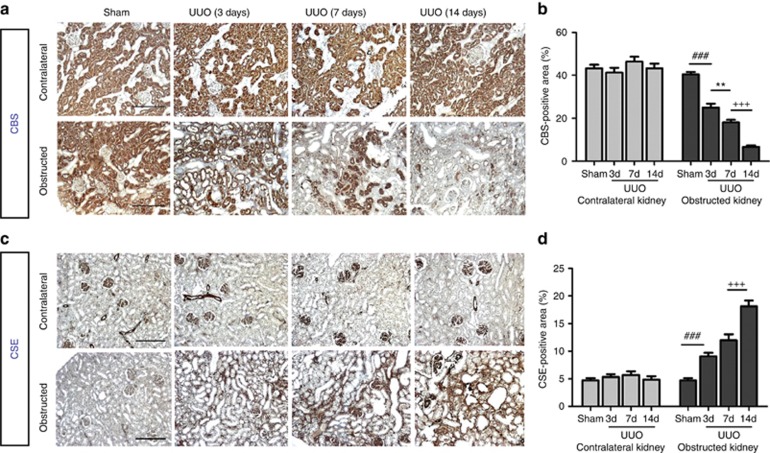

To investigate whether endogenous H2S was involved in the pathogenesis of renal fibrosis, we examined the expression and activity of H2S-producing enzymes CBS and CSE, as well as plasma H2S levels. The CBS expression was nearly completely ablated by obstructive injury at day 14, whereas CSE was increased. In contrast, the expressions of CBS and CSE in the contralateral kidneys were not affected (Figure 1a–c). Moreover, H2S generation in the obstructed kidneys was dramatically reduced compared with sham-operated rats (Figure 1d). Plasma H2S levels were reduced by ∼30% in UUO rats compared with the sham counterparts (27.5±4.3 μmol/l vs. 39.4±6.3 μmol/l, P=0.021, Figure 1e). Immunohistochemistry staining indicated that CBS was predominantly expressed in proximal renal tubules. UUO injury time-dependently reduced CBS expression in the obstructed kidneys without affecting that in the contralateral and sham-operated kidneys (Figure 2a and b). In contrast, CSE was mainly located in renal glomeruli, interstitium, and interlobular arteries of normal rats. UUO injury markedly increased the CSE expression in the interstitium of obstructed kidneys. The CSE expression in the unobstructed kidneys remained unchanged (Figure 2c and d).

Figure 1.

Unilateral ureteral obstructive (UUO) injury downregulates cystathionine-β-synthase (CBS) expression and decreases hydrogen sulfide (H2S) level in plasma on day 14 after operation. (a) Representative western blots of CBS and cystathionine-γ-lyase (CSE) proteins in sham and UUO group are shown. Relative levels of (b) CBS and (c) CSE were analyzed by normalizing to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). (d) Kidney H2S production and (e) plasma H2S level in sham and UUO group are shown. Data are mean±s.e.m., n=4–6, #P<0.05, ##P<0.01, ###P<0.001 versus sham group.

Figure 2.

Expression and localization of cystathionine-β-synthase (CBS) and cystathionine-γ-lyase (CSE) in rat renal cortex after unilateral ureteral obstructive (UUO) injury. (a, b) CBS was predominantly expressed in proximal renal tubules. CBS expression in the left (obstructed) kidneys was reduced at 3 (3d), 7 (7d), and 14 days (14d) after UUO injury, whereas it remained unchanged in the right (contralateral) kidneys. (c, d) CSE was mainly located in renal glomeruli, interstitium, and interlobular arteries and was markedly increased in the left (obstructed) kidneys at 3, 7, and 14 days after operation. In contrast, its expression in unobstructed kidneys was not altered. Scale bar=200 μm. Data are mean±s.e.m., n=4, ###P<0.001 versus sham group, **P<0.01 versus UUO 3-day group, +++P<0.001 versus UUO 7-day group.

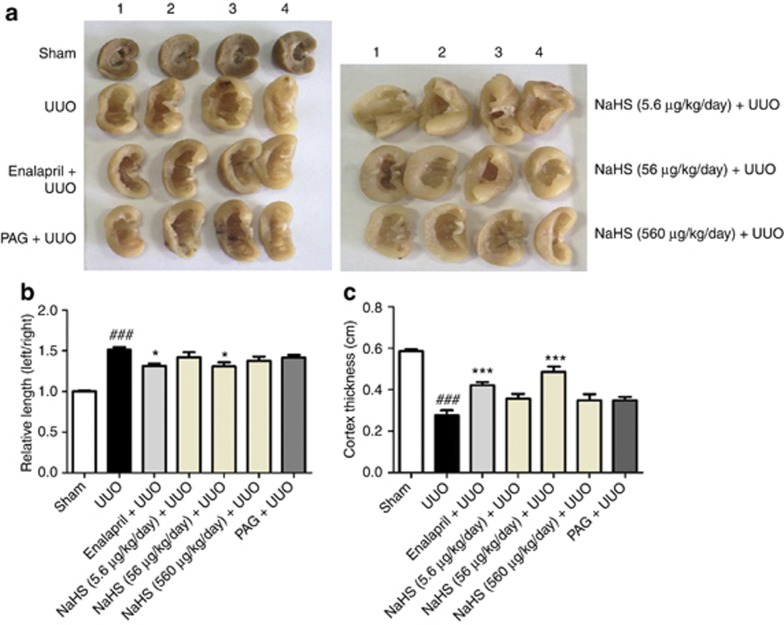

NaHS treatment decreases the renal size, increases the cortical thickness, and ameliorates renal function of UUO rats

To assess the effect of exogenous H2S supplement on renal fibrosis, we treated UUO rats with incremental doses of sodium hydrosulfide (NaHS; 5.6, 56, and 560 μg/kg/day) and CSE inhibitor (DL-propargylglycine (PAG), 25 mg/kg/day) via intraperitoneal injection once daily for 3 days before and 2 weeks after UUO injury. The renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitor enalapril (10 mg/kg/day) was also administrated via intragastria as a positive control. Gross appearance (Figure 2a) and group data (Figure 2b and c) showed that enalapril and NaHS (56 μg/kg/day) reduced the size of the kidney and increased the renal cortical thickness in UUO rats. However, these effects were not observed in the rats treated with NaHS at a higher dose of 560 μg/kg/day or PAG (Figure 3). Compared with UUO rats, NaHS (56 μg/kg/day) decreased serum creatinine levels, whereas PAG increased serum urea nitrogen concentration. There were no differences of serum electrolytes among each group (Supplementary Data and Supplementary Table S1 online).

Figure 3.

Sodium hydrosulfide (NaHS) treatment decreases the size and increases the cortical thickness of unilateral ureteral obstructive (UUO) kidney. (a) General appearance of four representative left kidneys of rats subjected to various treatments. UUO rats received vehicle (saline) treatment. NaHS (5.6, 56, and 560 μg/kg/day) and DL-propargylglycine (PAG; 25 mg/kg/day) were intraperitoneally given once daily 3 days before and continued for 2 weeks after operation, whereas enalapril (10 mg/kg/day) was given via intragastria. (b) Relative lengths of the left kidney calibrated by the right counterpart of the same rat in different groups. (c) Renal cortex thickness in the mid-portion of left kidney in coronal section. Data are mean±s.e.m. (n=7), ###P<0.001 versus sham group; *P<0.05, ***P<0.001 versus UUO group.

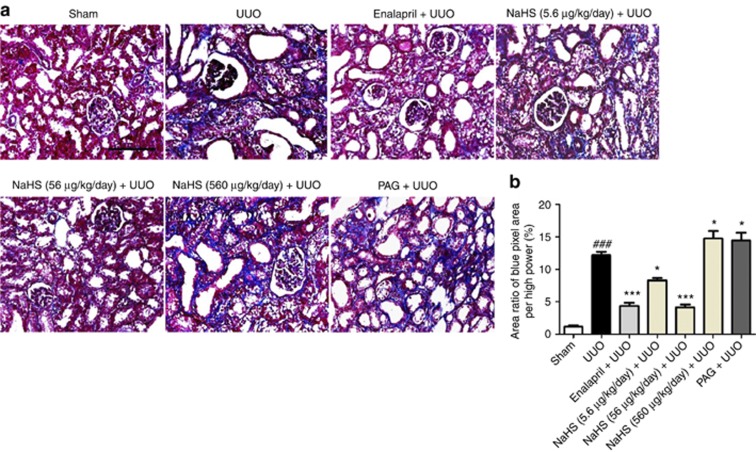

NaHS attenuates renal tubulointerstitial injury and collagen deposition in renal interstitium

Hematoxylin and eosin staining results indicated that UUO rats exhibited dilated renal tubule, epithelial cells atrophy, interstitial expansion, and increased infiltration of inflammatory cells at 14 days after operation. The tubulointerstitial injury of UUO rats was ameliorated when treated with NaHS (5.6 and 56 μg/kg/day) and enalapril. NaHS at 560 μg/kg/day and PAG failed to ameliorate the tubulointerstitial injury compared with UUO group (Supplementary Data and Supplementary Figure S1 online).

Masson trichrome staining demonstrated that UUO injury resulted in a significant accumulation of collagen fibrils (blue area) compared with the sham group. Enalapril and NaHS (5.6 and 56 μg/kg/day) attenuated the fibrotic lesions with less collagen deposited in the renal interstitium. In contrast, NaHS at 560 μg/kg/day and PAG increased the collagen production compared with that of the UUO group (Figure 4a and b).

Figure 4.

Sodium hydrosulfide (NaHS) treatment attenuates the accumulation of collagen fibrils in renal interstitium in the obstructed kidneys at 14 days after unilateral ureteral obstructive (UUO) operation. Representative pictures of (a) Masson trichrome staining and (b) semiquantitative analysis of the proportion with the blue color area over the whole field area in all groups are indicated. PAG, DL-propargylglycine. Scale bar=200 μm. Mean±s.e.m. (n=4), ###P<0.001 versus sham group; *P<0.05, ***P<0.001 versus UUO group.

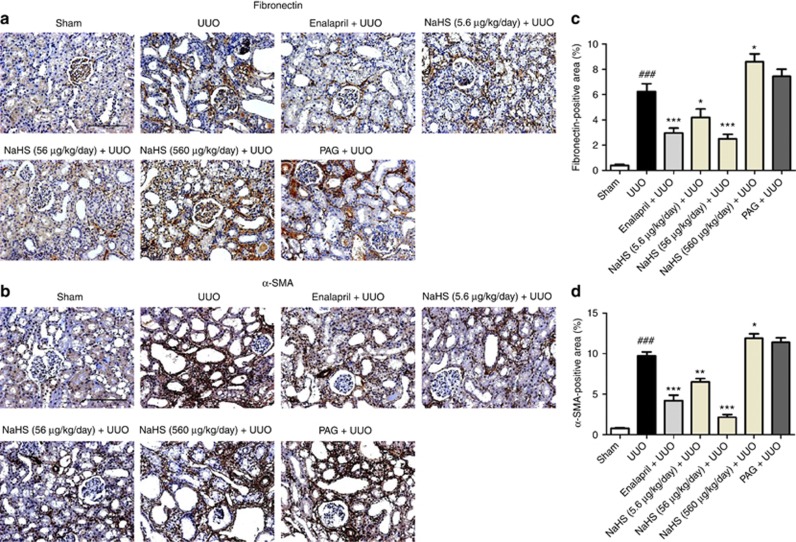

NaHS inhibits the expression of SMA and fibronectin in the obstructed kidney

To evaluate whether H2S reduced the production of myofibroblasts and extracellular matrix, the renal expression of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and fibronectin were detected on day 14 after UUO operation. Immunohistochemistry staining and semiquantitative analysis showed that enalapril and NaHS (5.6 and 56 μg/kg/day) decreased the expressions of α-SMA and fibronectin of the UUO rats. In contrast, NaHS 560 μg/kg/day and PAG increased the production of these proteins, but statistical difference was not obtained in the PAG group (Figure 5a–d). These observations were verified by western blot analysis, in which NaHS, especially at the dose of 56 μg/kg/day, markedly reduced the expressions of α-SMA, fibronectin, phospho-Smad3, and transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) (Figure 6a–d).

Figure 5.

Sodium hydrosulfide (NaHS) inhibits the expressions of fibronectin and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) in the obstructed kidneys at 14 days after unilateral ureteral obstructive (UUO) operation. Representative immunohistochemistry images for the expression of (a) fibronectin and (b) α-SMA, and semiquantitative analysis of these two proteins are presented. PAG, DL-propargylglycine. Scale bar =200 μm. Data are mean±s.e.m. of 10 non-overlapping fields from four animals per group, ###P<0.001 versus sham group; *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 versus UUO group.

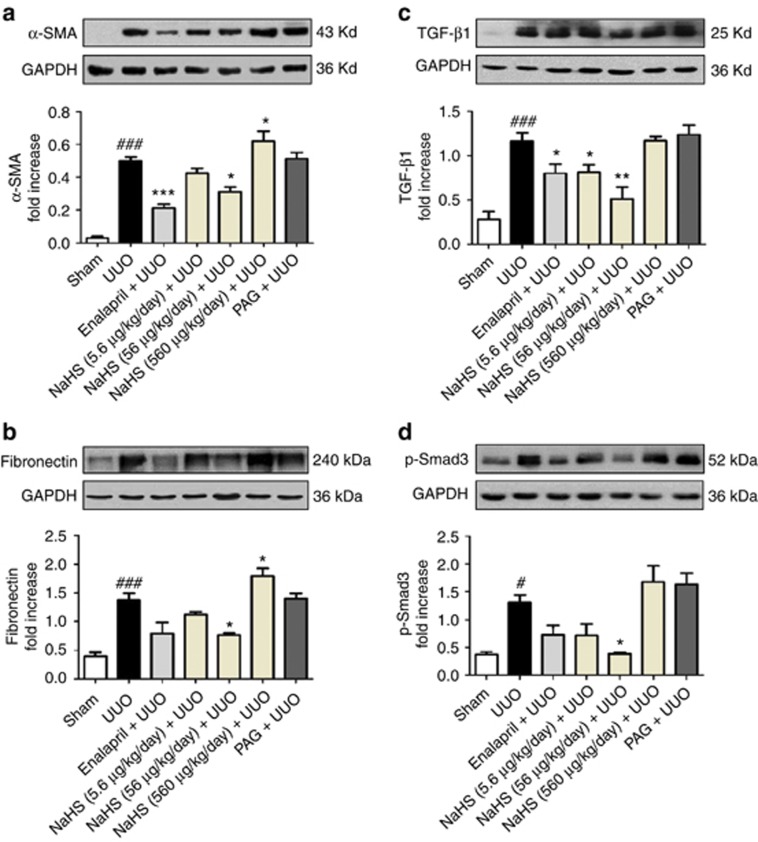

Figure 6.

Sodium hydrosulfide (NaHS) downregulates the expression of fibrosis-associated and signaling molecules in the obstructed kidneys at 7 days after unilateral ureteral obstructive (UUO) operation. Whole kidney tissue lysates were immunoblotted with antibody against (a) α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), (b) fibronectin, (c) transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1), and (d) phospho-Smad3 in each group and quantitative analyses of the relative abundance of these proteins among various groups are presented. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; PAG, DL-propargylglycine. Mean±s.e.m., n=4, #P<0.05, ###P<0.001 versus sham group; *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 versus UUO group.

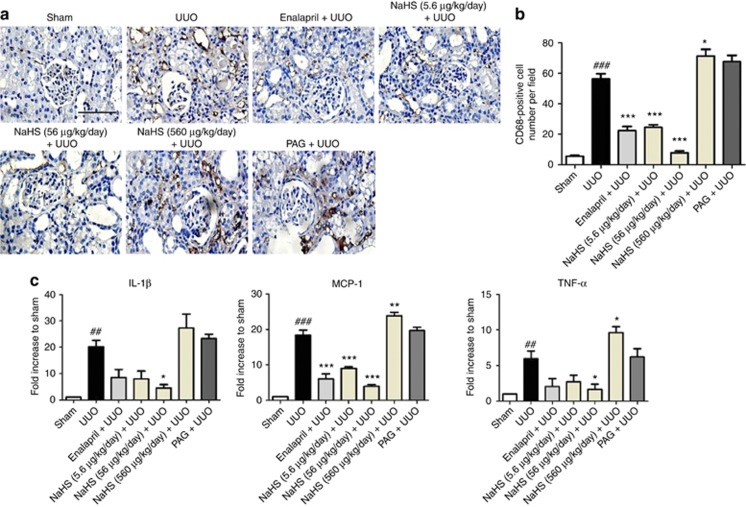

NaHS inhibits inflammation in the kidney after obstructive injury

The effect of H2S on the infiltration of inflammatory cells in obstructed kidneys was also determined at 7 days after UUO. CD68 (a macrophage marker) staining in renal cortex revealed an increased macrophage infiltration in the renal interstitium of UUO rats. NaHS (5.6 and 56 μg/kg/day) and enalapril markedly reduced the number of macrophage in the interstitium against the UUO group. This effect was most pronounced in the NaHS (56 μg/kg/d)-treated group. Compared with the UUO group, NaHS at 560 μg/kg/day increased the number of macrophage in renal cortex, whereas PAG tended but failed to significantly increase the CD68-positive cell number (Figure 7a and b).

Figure 7.

Sodium hydrosulfide (NaHS) inhibits the macrophage infiltration in the obstructed kidneys at 7 days after unilateral ureteral obstructive (UUO) operation. (a) Representative pictures of kidney sections stained with anti-CD68. A total of 10 fields from 4 animals were included in analyzing the number of CD68-positive cells in the interstitium and (b) the group data are shown correspondingly. (c) Quantitative PCR results of the mRNA levels of interleukin-1β (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) in the kidneys among different treatment groups. PAG, DL-propargylglycine. Scale bar=100 μm. Data are presented as mean±s.e.m., ##P<0.01, ###P<0.001 versus sham group; *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 versus UUO group.

To confirm the anti-inflammatory effect of NaHS, the mRNA levels of interleukin-1β, tumor necrosis factor-α, and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 were determined by quantitative PCR. All these inflammatory molecules were increased by UUO injury. NaHS (5.6 and 56 μg/kg/day) and enalapril suppressed the expression of these cytokines, whereas NaHS at 560 μg/kg/day and PAG were unable to exhibit anti-inflammatory effects (Figure 7c).

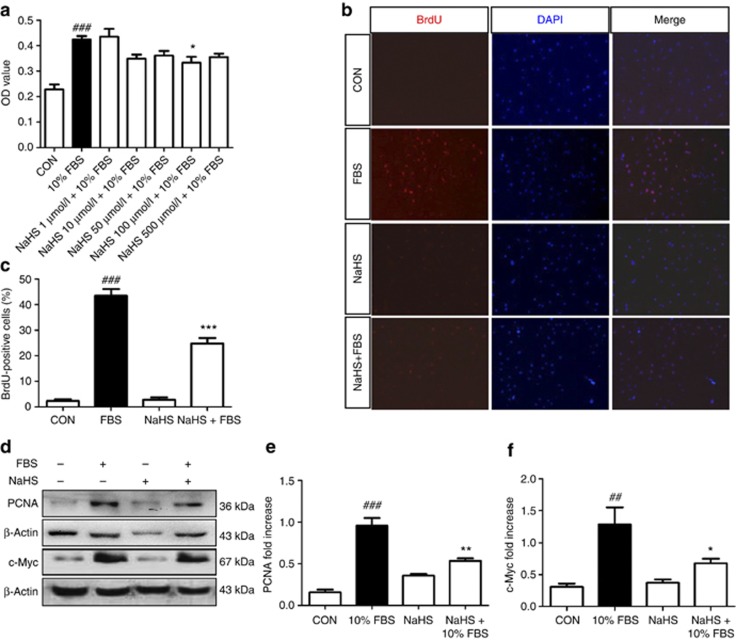

NaHS suppresses the NRK-49F cell proliferation induced by fetal bovine serum (FBS)

We further performed an in vitro study to investigate the antiproliferation effect of H2S on renal fibroblast using NRK-49F cells. Cells were exposed to various concentrations (1–500 μmol/l) of NaHS for 30 min, followed by stimulation with 10% FBS for 24 h. Cells with serum-free medium were set as controls. MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay showed the cell number was significantly increased after incubation with 10% FBS for 24 h (P<0.05, Figure 8a). Preincubation with NaHS (10, 50, 100, and 500 μmol/l) reduced the cell number by 17.6%, 14.8%, 21.4%, and 16.2%, respectively. However, statistical difference was only reached in 100 μmol/l NaHS group and the dose-dependent effect was not observed.

Figure 8.

Sodium hydrosulfide (NaHS) suppresses the proliferation of NRK-49F cells. Serum-starved cells were preincubated with NaHS at concentrations as indicated for 30 min, followed by stimulation with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) for 24 h. Serum-starved cells without FBS treatment served as controls (CON). (a) MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay shows the optical density (OD) value of various treatment groups. (b, c) Representative micrographs (original magnification × 200, b) and (c) group data display the number of bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU)-positive cells. Cells were stained with anti-BrdU antibody (red) and 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; blue) was used to visualize the nuclei. N=6. (d–f) Representative pictures (d) and group data analysis (e, f) for proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) and c-Myc expressions in NRK-49F cells subjected to various treatments. Relative abundance was determined by normalizing to β-actin. Data are mean±s.e.m. of three independent experiments. ##P<0.01, ###P<0.001 versus control group; *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 versus 10% FBS group.

Furthermore, we continued to test whether H2S inhibited the DNA synthesis of renal fibroblast cells using bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation assay. The DNA synthesis triggered by 10% FBS was significantly decreased by NaHS (100 μmol/l) before treatment (Figure 8b and c). To delineate the mechanism beneath the antiproliferation effect of H2S, the expression of proliferation-related genes, including proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) and c-Myc, was also assessed. Preincubation with 100 μmol/l NaHS consistently attenuated the expressions of PCNA and c-Myc proteins induced by 10% FBS stimulation for 24 h (Figure 8d–f).

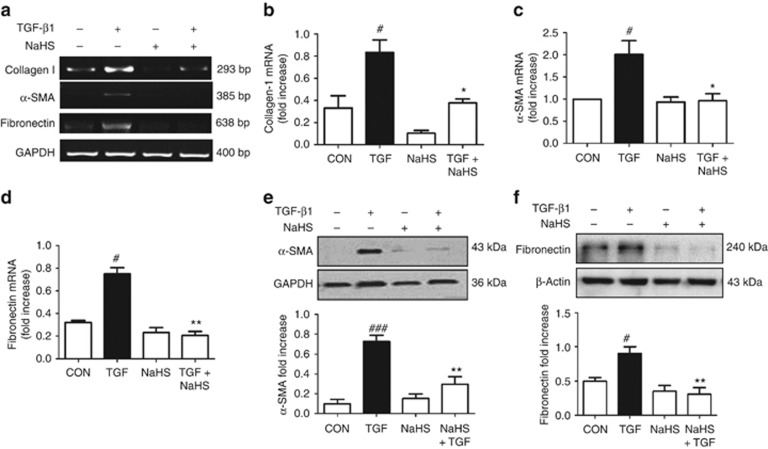

NaHS blocks the differentiation of quiescent renal fibroblasts to myofibroblasts

Because TGF-β1 is the most potent cytokine controlling the phenotype switch from renal fibroblasts to myofibroblasts, we investigated the effect of H2S on renal fibroblast activation induced by TGF-β1. Reverse transcription–PCR demonstrated that NaHS pretreatment inhibited the mRNA expressions of collagen I, α-SMA, and fibronectin induced by TGF-β1 (Figure 9a–d). Western blot analysis also revealed a significant elevation of α-SMA and fibronectin expression in NRK-49F cells after TGF-β1 stimulation. These effects were essentially abolished by NaHS (Figure 9e and f).

Figure 9.

Sodium hydrosulfide (NaHS) pretreatment blocks the differentiation of renal fibroblasts to myofibroblasts. Serum-starved cells were incubated with NaHS (100 μmol/l) for 30 min, and then stimulated with transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1; 2 ng/ml) for 12 h (reverse transcription–PCR) or 24 h (western blot). (a–d) Collagen I, fibronectin, and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) mRNA levels were determined by (a) reverse transcription–PCR and (b–d) semiquantified by normalizing to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) by densitometric analysis. (e, f) Whole-cell lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies against (e) α-SMA and (f) fibronectin, respectively. GAPDH and β-actin were loaded as internal controls. Data are mean±s.e.m. of three independent experiments, #P<0.05, ###P<0.001 versus control group; *P<0.05, **P<0.01 versus TGF group.

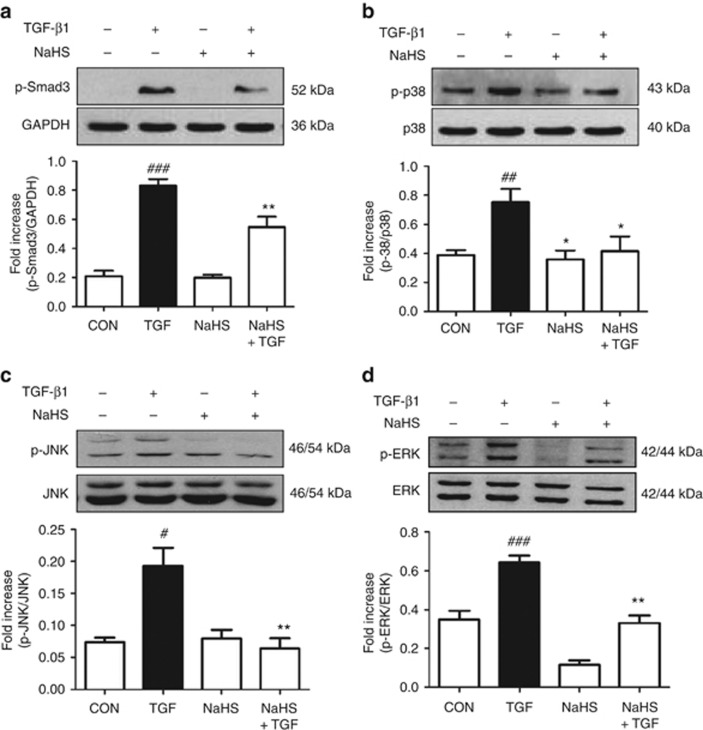

NaHS abolishes the phosphorylation of the MAPKs and Smad3

TGF-β1-Smad and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways are two critical signaling mechanisms implicated in renal fibrosis. We therefore examined the effects of H2S on the TGF-β1-induced phosphorylation of Smad3, p38, c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and extracellular signal–regulated kinase (ERK) with western blot analysis. TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml) triggered the phosphorylation of these proteins with distinct patterns. The phosphorylation of p38 peaked at 0.5 h after TGF-β1 stimulation, quicker than that of the other molecules. Specifically, phosphorylation of ERK and JNK peaked at 2 h after TGF-β1 exposure whereas Smad3 at 1 h (data not shown). Pretreatment with 100 μmol/l NaHS abolished the increase of Smad3 and MAPKs phosphorylation induced by TGF-β1 stimulation (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Sodium hydrosulfide (NaHS) abolishes the phosphorylation increase of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and Smad3. Serum-starved cells were incubated with NaHS (100 μmol/l) for 30 min, followed by transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1; 2 ng/ml) treatment for 1 h in the presence or absence of NaHS. Cell lysates were subjected to western blotting with antibodies against (a) phospho-Smad3, (b) phospho-p38/p38, (c) phospho-JNK/JNK, and (d) phospho-ERK/ERK. Relative abundance was quantified by densitometry and normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), p38, c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and extracellular signal–regulated kinase (ERK), respectively. Data are mean±s.e.m., n=3, #P<0.05, ##P<0.01, ###P<0.001 versus control group; *P<0.05, **P<0.01 versus TGF group.

DISCUSSION

UUO is a well-established animal model featured by progressive renal fibrosis and tubulointerstitial injury. In this study, we demonstrated that exogenous H2S suppressed collagen and extracellular matrix deposition in the UUO rats. We also identified that H2S blocked renal fibrosis via multiple mechanisms. It inhibited renal fibroblast proliferation by reducing DNA synthesis and downregulating the expressions of proliferation-related proteins. H2S also blocked cell differentiation by suppressing the TGF-β1-Smad and MAPK signal pathways. Besides, H2S inhibited the inflammatory process induced by UUO injury.

The association of H2S and renal fibrosis is not well defined. Our study demonstrated that plasma H2S levels and endogenous H2S production in the obstructed kidneys were decreased in UUO rats. As UUO model is devoid of any exogenous toxin, or a ‘uremic' environment,16 our finding implies that renal fibrosis per se could reduce the H2S generation. Our study further demonstrated that CBS was predominantly expressed in renal tubules whereas CSE was mainly located in glomeruli and interstitial vessels, consistent with a recent report.17 UUO injury markedly decreased the expression of CBS but increased that of CSE in the renal interstitium. This finding is consistent with previous studies that CBS is more predisposed to decrease in kidney disease compared with CSE. For instance, CBS was decreased 6 weeks earlier than CSE in rat remnant kidney.8 In renal ischemic–reperfusion rats, CBS was reduced as earlier as 6 h after reperfusion,18 whereas CSE was increased by prolonged reperfusion for 24 h.19 Hence, the increase of CSE observed in this study could be explained as a ‘compensatory mechanism' to maintain the H2S level. As CSE is abundant in glomeruli, H2S may also be beneficial for glomerular diseases. A recent study by Lee et al.20 confirms this notion that H2S is able to protect the renal glomerular epithelial cells from high glucose–induced injury, indicating the reduction of H2S is involved in diabetic nephropathy.

As the endogenous H2S production was reduced by UUO injury, it is logical to hypothesize that exogenous H2S supplementation could relieve renal fibrosis. We observed that the antifibrotic effect of NaHS started at 5.6 μg/kg/day, peaked at 56 μg/kg/day, but was reversed at 560 μg/kg/day. Our results were in line with a prior study in which the most effective NaHS dose on cardiac ischemia–reperfusion injury was 56 μg/kg/day.21 Moreover, low doses of NaHS (78 and 392 μg/kg/day body weight, twice daily) also reduced pulmonary fibrosis induced by bleomycin.11 Previous studies demonstrated that H2S level in vertebrate blood varied from 10–300 μmol/l by the methylene blue assay.22, 23 Using a sensitive fluorescent probe,24 we found the plasma H2S level in normal rat was ∼30–40 μmol/l, whereas its counterpart in the UUO rat was 20–30 μmol/l. Nevertheless, the precise determination of H2S in biological samples is still controversial. More sensitive techniques such as monobromobimane-based assay and quantum dot/nanoparticle methods recently indicated that blood and tissue H2S concentrations were as low as 0.15–0.9 μmol/l.25, 26 These findings may justify the application of H2S at relatively low doses in treating renal fibrosis.

Although H2S is beneficial in most animal models of renal diseases, endogenous H2S has been reported detrimental in acute kidney injury caused by nephrotoxic drugs. For instance, the CSE inhibitor PAG (50 mg/kg/day) reduced the kidney damage of Wistar rats induced by cisplatin and adriamycin.27, 28 This is inconsistent with our data in which PAG was unable to relieve renal fibrosis. In fact, 50 mg/kg/day PAG treatment resulted in a great weight loss of normal Sprague–Dawley rats in our study (data not shown), and the dose had to be lowered to 25 mg/kg/day. Such conflicting aspects of H2S implicate that diverse mechanisms of H2S may exist in different animal models and species. Despite this, caution must be taken in interpreting the effect of PAG because of its nonselective inhibitory action of CSE. It has been reported that D-amino acid oxidase and L-alanine transaminase can also be inhibited by PAG.29, 30 Possibilities cannot be ruled out that the protective effect of PAG in renal disease may be mediated by inactivating other enzymes rather than CSE.

Fibroblast proliferation and phenotypic transition to myofibroblast are two major cellular events of renal fibrosis.31 FBS contains numerous growth factors that promote the proliferation and differentiation in many types of cells. The effect of H2S on cell proliferation seems to be cell specific. Some studies reported that H2S promoted the proliferation in rat intestinal epithelial cells and human colon cancer cells, whereas others demonstrated that it inhibited the proliferation of lung fibroblasts and pancreatic stellate cells.32, 33 Our data revealed that NaHS at 100 μmol/l not only decreased the cell number, but also inhibited the DNA synthesis stimulated by FBS. These findings were further verified by the fact that NaHS downregulated the expressions of proliferation-related genes including PCNA and c-Myc. Previous studies also indicated that H2S induced DNA damage in many cell types.34 The proliferation and cell cycle proteins such as p53, p21, and cyclin D1 were downregulated by H2S.35, 36

Numerous cytokines and growth factors such as TGF-β1, platelet-derived growth factor, tissue plasminogen activator, and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 are involved in the phenotypic switch of fibroblast to myofibroblast.37, 38, 39, 40 Microarray analysis in an intestinal cell line suggests that TGF-β1 and MAPK kinases are regulated by H2S.41 Our results showed that NaHS at 100 μmol/l suppressed mRNA and protein expressions of α-SMA and fibronectin induced by TGF-β1. In addition, H2S attenuated the phosphorylation of Smad3, a major pathway in the signal transduction of TGF-β1. These data suggested that H2S inhibited the fibroblast differentiation and extracellular matrix production partially by blocking the TGF-β1-Smad signaling. In addition to Smad-dependent pathway, MAPK kinases also engage in the effect of TGF-β1. ERK, p38, and JNK have been found to be activated in UUO model and regulate the proliferation, migration, and differentiation of fibroblast.42 Our data indicated that H2S reversed the phosphorylation increase of p38, ERK, and JNK stimulated by TGF-β1 in renal interstitial fibroblasts, implying that the blockade of MAPK kinases activation may be another mechanism responsible for the antifibrotic effect of H2S.

Inflammation plays an important role in the priming and progression of renal fibrosis.43 One of the pathological features of the UUO rat model is the marked infiltration of inflammatory cells in the renal interstitium. Substantial data support the anti-inflammation action of H2S in multiple organs and systems.44 Our study echoed with these studies that H2S exhibited an anti-inflammatory property by reducing macrophage recruitment in renal interstitium. The inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1β, tumor necrosis factor-α, and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 were also downregulated by NaHS. MAPKs are involved in modulating inflammatory processes. For example, JNK has been identified with the activation of macrophages and upregulation of proinflammatory mediators, and JNK inhibition resolves the inflammation.45 Thus, the anti-inflammatory effect of H2S may be mediated by inhibiting the MAPK signal pathway.

In summary, this study demonstrates for the first time that H2S exhibited antifibrotic effects on obstructed nephropathy and inhibited the proliferation and differentiation of renal fibroblasts both in vitro and in vivo. The antifibrotic mechanisms of H2S may involve its anti-inflammation as well as its blockade on TGF-β1 and MAPK signaling. This may provide a therapeutic option for renal fibrosis based on H2S modulation. Low dosage of H2S or its releasing compounds may have therapeutic potentials in treating CKD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and antibodies

BrdU, PAG, enalapril, and NaHS, as well as antibodies against PCNA, c-Myc, and BrdU were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO). Recombinant human TGF-β1 and Trizol reagent were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Antibodies against α-SMA, fibronectin, CBS, and ERK/phosphorylated-ERK were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). CSE antibody was purchased from Abnova Chemical (Taiwan, China). Other antibodies unless specified were from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA).

Animal surgery and experimental protocols

Male Sprague–Dawley rats (180–200 g) were purchased from Shanghai Laboratory Animal Commission (Shanghai, China). UUO operation was performed as described previously.16 Rats were randomly divided into the following seven groups: sham, UUO, UUO with enalapril (10 mg/kg/day), UUO with three doses of NaHS (5.6, 56, and 560 μg/kg/day), and UUO with PAG (25 mg/kg/day). NaHS and PAG were given intraperitoneally once daily 3 days before surgery and continued for 1 to 2 weeks after operation. Enalapril was given via intragastria. UUO rats received vehicle (saline) treatment. All rats were killed at day 7 or 14 days after surgery. The kidneys were then harvested and plasma was collected accordingly. The experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Soochow University.

Histological analysis and immunohistochemical staining

Kidney samples were fixed in 10% formalin, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned 4 μm thick. Sections were deparaffined and stained with Masson trichrome reagents and observed under a light microscope. Renal collagen (blue area) was semiquantitatively measured at × 200 magnification in 10 randomly selected fields from 4 animals using Image Pro-Plus 6.0 software (Bethesda, MD).

For immunohistochemical studies, renal sections were incubated with antibodies against α-SMA (1:50), fibronectin (1:50), and CD68 (1:50) overnight at 4 °C, and subsequently incubated with corresponding secondary antibodies at room temperature for 1 h. Peroxidase-Streptavidin-biotin complex (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and diaminobenzidine (Sigma, St Louis, MO) was used to visualize the proteins. Ten randomly selected fields ( × 200 magnifications for α-SMA and fibronectin, and × 400 magnifications for CD68) were photographed and measured by a blinded observer using Image Pro-Plus 6.0 software.

Plasma H2S and tissue H2S synthesis measurement

Plasma H2S level was detected using Dansyl azide (DNS-Az), a novel fluorescent H2S probe (kindly gifted by Professor Binghe Wang, Georgia State University) as described previously.24 Briefly, DNS-Az stock solution (2.2 mmol/l) was added at 10 μl per well in a 96-well plate, followed by mixing with 100 μl plasma. Fluorescence was immediately measured by a fluorescent microplate reader (Tecan M200, Grodig, Austria) with an excitation at 360 nm and emission at 528 nm.

Tissue H2S production measurement was performed as previously described.46 In brief, the left kidney homogenates were mixed with 2 mmol/l pyridoxal 5′-phosphate and 10 mmol/l L-cysteine and 250 μl 10% trichloroacetic acid to reach a total volume of 750 μl. After incubation at 37 °C for 30 min, 250 μl 1% zinc acetate was added to trap H2S. Then, 133 μl of 20 mmol/l N,N-dimethyl-p-phenylenedi-amine sulfate in 7.2 mol/l HCl and 133 μl of 30 mmol/l FeCl3 in 1.2 mol/l HCl were added. The absorbance of the solution was determined at 670 nm with a spectrophotometer. The H2S concentration was calculated against a calibration curve of NaHS (0.1–100 μmol/l).

Cell culture and treatments

Normal rat kidney fibroblasts (NRK-49F) were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (4.5 g/l glucose) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Grand Island, NY). After preincubation with NaHS at various concentrations (1–500 μmol/l) for 30 min, recombinant human TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml) was added for various periods of time. In the control group, cells were treated with vehicle only. In proliferation studies, 10% FBS served as stimulators and the cells were subjected to serum-free medium for 24 h before experimentation.

Cell proliferation assay

Cell proliferation was assessed by MTT assay and BrdU incorporation. For the MTT assay, cells (2 × 103/100 μl) were seeded in 96-well plate until subconfluence and quiescenced with serum-free medium for 24 h. Cells were then pretreated with NaHS (0.1–500 μmol/l) for 30 min, followed by incubation with or without 10% FBS for 24 h. MTT (0.5 mg/ml) was added at 4 h before treatment termination. At the end of treatment, medium was removed and dimethylsulfoxide at 150 μl per well was then added. Absorbance at 490 nm was measured by a microplate reader (Tecan M200).

For the BrdU incorporation, cells were seeded onto coverslips. After being pretreated with 100 μmol/l NaHS for 30 min, cells were incubated in medium with or without 10% FBS for 5 h, and pulsated with BrdU (10 μmol/l) for another 5 h. Next, cells were fixed in 4% paraformadehyde for 20 min and DNA was denatured with 2 N HCl at 37 °C for 10 min. After blocking, the incorporated BrdU was detected with a mouse anti-BrdU antibody (1:100, Sigma) at 4 °C overnight, followed by incubation with Alexa Fluor 555 Donkey anti-mouse IgG (1:500, Invitrogen) for 1 h. Subsequently, coverslips were mounted and observed under a fluorescent microscope (AXIO SCOPE A1; Zeiss, Jena, Germany).

Reverse transcription–PCR and quantitative PCR

Total RNA was extracted with Trizol reagent and reverse transcription–PCR was performed using an Advantage RT-for-PCR kit and PCR Master Mix kit (Fermentas, Vilnius, Lithuania) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The quantitative PCR reactions were performed using a real-time SYBR technology and on ABI Prism 7000 DNA Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster, CA). For each sample, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and 18S RNA was also assayed as an internal control and final result were normalized to and expressed as ratios of the target gene/internal controls. The primers used in the PCR reactions are listed in Supplementary Table S2 online.

Western blot

Given the heterogeneous expression of CBS and CSE in the kidney, the whole kidney was halved in the middle. One half was used for histological studies, and the other half was homogenized for western blotting analysis. Protein samples (20–80 μg) were separated by 8–10% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels and transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA). After blocking in 5% milk/Tris-buffered saline and Tween-20 buffer, membranes were individually incubated with antibodies against proteins of interest at an appropriate dilution (α-SMA (1:1000), fibronectin (1:500), CBS(1:500), CSE (1:250), ERK/phospho-ERK (1:500), JNK/phospho-JNK (1:500), P38/phospho-P38 (1:500), phospho-Smad3 (1:500), PCNA (1:1000), and c-Myc (1:1000)) at 4 °C overnight. Membranes were then washed and incubated with appropriate horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h. Visualization was carried out using an advanced chemiluminescence kit (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK). The band density was quantified by ImageJ software (Bethesda, MD). GAPDH or β-actin was used as an internal control.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean±s.e.m. Statistical significance was determined using Student's t-test or one-way analysis of variance followed by a post hoc analysis (Tukey's test) where applicable. The significance level was set at P<0.05.

Acknowledgments

We were grateful for the kind gift of Dansyl azide by Professor Binghe Wang from Georgia State University. This work was supported by the research grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81200495/2012 to KS and 81171212 to LF-H) and the start-up funding for imported overseas talents of Soochow University (Q421500210), and was also funded by a project funded by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD). HP was supported by the Center for Diagnostics and Therapeutics (CDT) program and Georgia State University Fellowship through the CDT.

A patent application on the potential therapeutic option of H2S-releasing compounds in renal fibrosis (201210524309.1) has been filed to China Intellectual Property Office. All the authors declared no competing interests.

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Table S1. Renal function and serum electrolytes among different animal groups.

Table S2. The primers used for reverse transcription and quantitative PCR reactions.

Supplementary material is linked to the online version of the paper at http://www.nature.com/ki

Supplementary Material

References

- Harris RC, Neilson EG. Toward a unified theory of renal progression. Annu Rev Med. 2006;57:365–380. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.57.121304.131342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeisberg M, Neilson EG. Mechanisms of tubulointerstitial fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:1819–1834. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010080793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boor P, Ostendorf T, Floege J. Renal fibrosis: novel insights into mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2010;6:643–656. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2010.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boor P, Sebeková K, Ostendorf T, et al. Treatment targets in renal fibrosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:3391–3407. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R. Shared signaling pathways among gasotransmitters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:8801–8802. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206646109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia M, Chen L, Muh RW, et al. Production and actions of hydrogen sulfide, a novel gaseous bioactive substance, in the kidneys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;329:1056–1062. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.149963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bełtowski J. Hypoxia in the renal medulla: implications for hydrogen sulfide signaling. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;334:358–363. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.166637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aminzadeh M, Vaziri N. Down-regulation of the renal and hepatic hydrogen sulfide (H2S) producing enzymes and capacity in chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:498–504. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perna AF, Luciano MG, Ingrosso D, et al. Hydrogen sulphide-generating pathways in haemodialysis patients: a study on relevant metabolites and transcriptional regulation of genes encoding for key enzymes. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:3756–3763. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen U, Basu P, Abe OA, et al. Hydrogen sulfide ameliorates hyperhomocysteinemia-associated chronic renal failure. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009;297:F410–F419. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00145.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang L, Li H, Tang C, et al. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates the pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis induced by bleomycin in rats. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2009;87:531–538. doi: 10.1139/y09-039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Seweidy MM, Sadik NA, Shaker OG. Role of sulfurous mineral water and sodium hydrosulfide as potent inhibitors of fibrosis in the heart of diabetic rats. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2011;506:48–57. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan G, Pan S, Li J, et al. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatotoxicity, liver cirrhosis and portal hypertension in rats. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25943. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrissey JJ, Ishidoya S, Mc Cracken R, et al. Nitric oxide generation ameliorates the tubulointerstitial fibrosis of obstructive nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1996;7:2202–2212. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V7102202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Lee JY, Kwak JH, et al. Protective effects of low-dose carbon monoxide against renal fibrosis induced by unilateral ureteral obstruction. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;294:F508–F517. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00306.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier RL, Forbes MS, Thornhill BA. Ureteral obstruction as a model of renal interstitial fibrosis and obstructive nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2009;75:1145–1152. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos EM, Wang R, Snijder PM, et al. Cystathionine γ-lyase protects against renal ischemia/reperfusion by modulating oxidative stress. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24:759–770. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012030268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu N, Siow YL, Karmin O. Ischemia/reperfusion reduces transcription factor SP1 mediated cystathionine b-synthase expression in the kidney. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:18225–18233. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.132142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripatara P, Patel NSA, Collino M, et al. Generation of endogenous hydrogen sulfide by cystathionine gamma-lyase limits renal ischemia/reperfusion injury and dysfunction. Lab Invest. 2008;88:1038–1048. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HJ, Mariappan MM, Feliers D, et al. Hydrogen sulfide inhibits high glucose-induced matrix protein synthesis by activating AMP-activated protein kinase in renal epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:4451–4461. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.278325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan TT, Chen YQ, Bian JS. All in the timing: a comparison between the cardioprotection induced by H2S preconditioning and post-infarction treatment. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;616:160–165. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield NL, Kreimier EL, Verdial FC, et al. Reappraisal of H2S/sulfide concentration in vertebrate blood and its potential significance in ischemic preconditioning and vascular signaling. Am J Physiol Regul Integr CompPhysiol. 2008;294:R1930–R1937. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00025.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong G, Chen F, Cheng Y, et al. The role of hydrogen sulfide generation in the pathogenesis of hypertension in rats induced by inhibition of nitric oxide synthase. J Hypertens. 2003;21:1879–1885. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200310000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng H, Cheng Y, Dai C, et al. A fluorescent probe for fast and quantitative detection of hydrogen sulfide in blood. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2011;50:9672–9675. doi: 10.1002/anie.201104236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wintner EA, Deckwerth TL, Langston W, et al. A monobromobimane-based assay to measure the pharmacokinetic profile of reactive sulphide species in blood. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:941–957. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00704.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang BH, Wu FY, Wu YM, et al. Fluorescent method for the determination of sulfide anion with ZnS:Mn quantum dots. J Fluoresc. 2010;20:243–250. doi: 10.1007/s10895-009-0545-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Della Coletta Francescato H, Cunha FQ, Costa RS, et al. Inhibition of hydrogen sulphide formation reduces cisplatin-induced renal damage. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:479–488. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francescato HD, Marin EC, Cunha Fde Q, et al. Role of endogenous hydrogen sulfide on renal damage induced by adriamycin injection. Arch Toxicol. 2011;85:1597–1606. doi: 10.1007/s00204-011-0717-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett G, Marcotte P, Walsh C. Mechanism-based inactivation of pig heart L-alanine transaminase by L-propargylglycine. Half-site reactivity. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:3487–3491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcotte P, Walsh C. Active site-directed inactivation of cystathionine γ-synthetase and glutamic pyruvic transaminase by propargylglycine. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1975;62:677–682. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(75)90452-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of renal fibrosis. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2011;7:684–696. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2011.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang LP, Lin Q, Tang CS, et al. Hydrogen sulfide suppresses migration, proliferation and myofibroblast transdifferentiation of human lung fibroblasts. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2009;22:554–561. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwer CI, Stoll P, Goebel U, et al. Effects of hydrogen sulfide on rat pancreatic stellate cells. Pancreas. 2012;41:74–83. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318223645b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baskar R, Bian J. Hydrogen sulfide gas has cell growth regulatory role. Eur J Pharmacol. 2011;656:5–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baskar R, Li L, Moore PK. Hydrogen sulfide-induces DNA damage and changes in apoptotic gene expression in human lung fibroblast cells. FASEB J. 2007;21:247–255. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6255com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G, Wu L, Bryan S, et al. Cystathionine gamma-lyase deficiency and overproliferation of smooth muscle cells. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;86:487–495. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böttinger EP, Bitzer M. TGF-beta signaling in renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:2600–2610. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000033611.79556.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floege J, Eitner F, Alpers CE. A new look at platelet-derived growth factor in renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:12–23. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007050532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao S, Shen H, Hou Y, et al. tPA is a potent mitogen for renal interstitial fibroblasts: role of beta1 integrin/focal adhesion kinase signaling. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:1164–1175. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.091269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy AA, Fogo AB. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in chronic kidney disease: evidence and mechanisms of action. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2999–3012. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006050503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deplancke B, Gaskins HR. Hydrogen sulfide induces serum-independent cell cycle entry in nontransformed rat intestinal epithelial cells. FASEB J. 2003;17:1310–1312. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0883fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma FY, Sachchithananthan M, Flanc RS, et al. Mitogen activated protein kinases in renal fibrosis. Front Biosci (Schol Ed) 2009;1:171–187. doi: 10.2741/s17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SB, Kalluri R. Mechanistic connection between inflammation and fibrosis. Kidney Int Suppl. 2010;78:S22–S26. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace JL, Ferraz JG, Muscara MN. Hydrogen sulfide: an endogenous mediator of resolution of inflammation and injury. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012;17:58–67. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyriakis JM, Avruch J. Mammalian MAPK signal transduction pathways activated by stress and inflammation: a 10-year update. Physiol Rev. 2012;92:689–737. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00028.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LF, Lu M, Tiong CX. Neuroprotective effects of hydrogen sulfide on Parkinson's disease rat models. Aging Cell. 2010;9:135–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.