Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study is to investigate whether pregaming (i.e., drinking prior to a social event) is a risk factor for hospitalization.

Participants

Participants (N=516) were undergraduate students with an alcohol-related sanction.

Method

Participants completed a survey about alcohol use, as well as behaviors and experiences prior to and during the referral event. The dependent variable was whether participants received medical attention at an emergency department during the sanction event.

Results

Results indicated that older students, females who pregame, students with higher alcohol use screening scores, lighter drinkers, and higher numbers of drinks before the referral event all increased the odds of receiving medical attention. Pregaming alone was not significantly related to receiving medical attention in the multivariate analysis.

Conclusions

Female students who pregame appear to be at risk for requiring hospitalization after drinking when controlling for the number of drinks consumed.

Keywords: alcohol, emergency department, gender, pregaming, prevention

Alcohol misuse by college students is a significant and ongoing public health concern, as nearly one third of 8 million American college students engage in risky drinking patterns, such as heavy episodic drinking (defined as consuming five or more alcoholic drinks in one sitting for me, 4 or more for women).1 Heavy episodic drinking is associated with an increased risk of experiencing wide-ranging alcohol-related consequences such as hangovers, injury, assault, sexual abuse, and death.2

It is estimated that approximately 29,412 young adults per year receive medical attention for alcohol overdoses alone.3 Acute intoxication and alcohol-related incidents compose the vast majority of emergency medical treatment cases amongst college students.4 In light of the severity and prevalence of medical attention for alcohol misuse, remarkably few studies have evaluated characteristics of students who experienced a severe alcohol-related incident that requires medical attention.

Pregaming is a potential risk factor for increased alcohol consumption that might be related to receiving medical attention. Also known as “prepartying,” “preloading,” or “drinking before drinking,” pregaming is defined as drinking large quantities of alcohol in a compressed time frame, prior to a social event, during which people drink while waiting for others to arrive, or to “get buzzed” before going to an event where alcohol will be expensive or not readily available.5 Pregaming appears to be prevalent on college campuses. A larger study that assessed 10,320 students at 30 US college and universities found that over 25% reported pregaming at least once a month (N = 2,888; 71% women; mean age 19.8).6 A growing body of research indicates that students who reported pregaming, engaged in the behavior approximately once per week and were more likely to be younger in age.7 Furthermore, research has found that students who pregame drink more alcohol, reach higher levels of intoxication, have higher scores on a frequently used alcohol misuse screening inventory called the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C8), and report experiencing higher amounts of negative alcohol-related consequences than non-pregamers.7,9–13

It is unknown whether female college students are at a higher-risk for receiving medical attention after heavy drinking than men. Women are a high-risk population for harmful effects of alcohol on wide-ranging health outcomes.14 However, little is known about the combination of gender and pregaming. Previous studies have shown that the prevalence of pregaming is similar amongst male and female college students,7,13 while other research has indicated it is more prevalent in females.9,15 This issue is of particular importance, as women may be at increased risk for negative outcomes from such behavior due to reaching higher blood alcohol concentrations in a shorter period of time.7 For example, women have been found to be a heightened risk for sexual victimization after drinking16 and that women who engage in pregaming experience higher rates of subsequent negative alcohol-related consequences.17,18

To date, no research has examined whether gender and pregaming uniquely contribute to the risk for requiring medical attention as a result of drinking. This study had three objectives. The first objective was to replicate previous research5 by comparing students who were sanctioned by the university to receive an brief motivational interview modeled after the Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students19 following a referral event (campus alcohol policy violation, alcohol-related arrest, or receiving medical attention) according to pregaming status prior the referral event on demographics and alcohol use. Second, to examine differences in demographics, alcohol use, and feelings of aversiveness (i.e., perceived severity) related to the referral event between college students who receive medical attention on the day of the referral event and college students who did not. It was hypothesized that students who received medical attention will be more likely to report pregaming, consume more alcohol prior to the referral event, be female, and describe their sanction experience as aversive when compared to students who did not receive medical attention on the day of their referral event. Given the relationship between gender and pregaming, the final objective was to investigate whether women who engaged in pregaming prior to the referral event were more likely to receive medical attention for alcohol-related consequences.

Methods

Setting and Recruitment

Research participants were undergraduate students (N =516) at a large university in the Mid-Atlantic who violated the campus alcohol policy, were arrested for an alcohol-related offense (e.g., driving under the influence), or received alcohol-related medical attention between August 2011 to July 2012. Reasons for referral included prohibited underage possession or use of alcohol (69%), receipt of medical attention for alcohol-related complications (29%), excessive consumption of alcohol (12%), driving under the influence/DUI (6%), possession of alcohol in a prohibited residence/building (5%), hosting a party with alcohol in the residence hall (3%), being in the presence of alcoholic beverages (1%), open-container in an unauthorized area (1%), supplying to minors (1%), or other (1%) (participants could receive more than one sanction). All students who received one of these sanctions were required by the university to pay a $200 program fee, complete a computerized baseline assessment that was partially administered by a staff member, receive a brief motivational intervention, and complete a 1 month follow-up. Additional details about the parent research are reported elsewhere (name deleted to maintain the integrity of the review process).

Participants had an average age of 19.30 years (SD = 1.53). The sample was 85% white (compared to 70% at the host site), 5% black (4.9% at the host site), 8% Hispanic (5% at the host site), 6% Asian (4.9% at the host site), 2% (0.09% at the host site) Native American or Alaskan Native, 1% (4.2% at the host site) Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, and 1% other (participants could select more than one race/ethnicity in this study). Participants were freshman (51%), sophomore (15%), junior (23%), and senior (11%).

Potential participants (N = 1,543) completed a brief screening questionnaire. Students were eligible to participate if they were 18 years or older (20 students were under 18), if their Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT)20 score was <16 (AUDIT scores ≥16 indicate severe alcohol-related problems or alcohol dependence (consistent with campus policy as students who received higher scores received more personalized attention); 178 students had AUDIT scores exceeding this cut-off), and if they did not endorse suicidal ideation (74 students endorsed suicidal ideation). Eligible students (N = 1,333) received a brief explanation of the study by a trained member of the research program. Participants were notified that they would be entered into a drawing to receive one of twenty $100 gift cards for the completion of a 3 month follow-up assessment. Of the eligible students, 43.9% (N = 585) consented to participate in this study and completed a baseline assessment. Students who did not consent to participate were required by campus administrators to complete the baseline assessment and receive a one-on-one alcohol intervention and complete the 1 month follow-up. All procedures for this study were approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Demographics

This measure assessed gender, age, race, ethnicity, and year in school. Participants were classified as non-white if they endorsed any race or ethnicity other than white/caucasian.

Alcohol Use

Alcohol use was measured by a modified Daily Drinking Questionnaire.21 This questionnaire assesses the number of drinks consumed on a typical day for each day of the week over the past 30 days. The number of drinks per typical week was obtained by adding the number of drinks consumed on each day of the week during a typical week of drinking (Cronbach’s alpha = .78).

Referral Event Experience Measure

This measure was a modified version of the event description measure used in previous studies.15,22 This measure was administered by a staff member and assesses key details regarding the participant’s behaviors and experiences that resulted in the referral event. Participants were asked specific questions regarding the event. First, information about receiving medical attention was obtained from the following question: “Did the incident involve alcohol-related treatment at [the closest hospital] (or another hospital)?” (Coded: 0 = no, 1 = yes). Second, participants were verbally provided with a commonly used definition of pregaming (“Drinking before you go out for the night [e.g. in your home/room or a friend’s home/room]. This includes drinking while waiting for people to gather for the evening, or drinking in order to “get buzzed” before going to a party/function at which alcohol will be expensive [e.g. at a bar or club] or difficult to obtain [e.g. at a school function]”),5 and were asked to report whether they participated in the aforementioned behavior prior to the referral event. Third, participants were asked to report the number of drinks they consumed while pregaming prior to the referral event.

Event Aversiveness

This three item measure assesses negative feelings after drinking from the following questions: “To what extent has this incident upset you?”; “When thinking about this incident, how badly do you feel about it?”; and “How unpleasant has this incident been for you?”23 Participants were asked to respond to each question using a response scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 7 (extremely or totally). The sum score of these items were used in this study (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.89).

Data Analysis Plan

First, the researchers evaluated whether students who pregame differ from non-pregamers (coded: 0 = non-pregamer, 1 = pregamer), based on demographics and alcohol use variables using a series of independent t-tests. Next, descriptive statistics for the sample were obtained to summarize alcohol use variables according to pregaming and non-pregaming drinking behaviors. Then, the researchers compared participants who received medical attention with those who did not, in order to identify characteristics associated with such individuals based on demographics and alcohol-use variables, using independent t-tests. For the primary analysis, logistic regression was used to determine the degree to which pregaming and gender were related to receiving medical attention on the day of the referral event after controlling for other predictors. In this model, receiving medical attention on the day of the referral event (coded: 0 = no medical attention, 1 = medical attention received) served as the dependent variable, and pregaming and gender (coded: 0 = male, 1 = female) served as independent variables. To control for variables that are known to be associated with alcohol-related harms, several covariates were included in the logistic regression including age, white/non-white (students who are white are a high-risk group for alcohol misuse),24 AUDIT scores, number of drinks consumed on the day of the referral event, and number of drinks consumed on a typical drinking occasion (in order to control for prior alcohol use). A gender X pregaming interaction was evaluated in order to explore whether gender moderated the effect of pregaming on the dependent variable (receiving medical attention during the referral event). All continuous predictors were mean centered to facilitate the interpretation of these findings. Data was analyzed using SPSS software version 21 (IBM SPSS Inc., 2012).

Results

Preliminary analysis

The researchers compared individuals who consented to participate to those who did not on the screening variables and gender. Participants who consented to participate were not significantly different from those who did not according to age and AUDIT scores. However, female students consented to participate at a higher rate than males (chi square = 6.47, p = 0.01).

Given that alcohol-related medical attention was the ultimate outcome variable, participants who did not drink alcohol prior to the referral event (n = 69) were dropped from the analysis, leaving an analytic sample of 516 participants. Preliminary data analysis was conducted to detect outliers on continuous variables. Outliers greater than 3 standard deviations (SD) from the mean were recoded to the next possible value.25 There were four outliers for the number of drinks consumed in a typical week and two outliers for the number of drinks consumed prior to the referral event. Two logistic regression models were conducted, one using the raw data, and the other using the data with recoded outliers. All significant and non-significant findings obtained from the logistic regression model using the raw data were identical to the parallel results using the recoded data. The presented results use the recoded data.

Descriptive Statistics

Regarding pregaming, 42.6% (n = 220) participants reported engaging in pregaming the day of the referral event while 57.4% (n = 296) did not. Participants who engaged in pregaming reported consuming an average of 5 drinks while pregaming (M = 5.34, SD = 3.51) and a total of 7.60 (SD = 4.33) drinks prior to the referral event. For students who engaged in pregaming, 70.3% of the drinks consumed prior to the referral event were consumed while pregaming. A comparison of participants based on whether they pregamed prior to the referral event is presented in Table 1. Females were more likely to pregame (45.9%) prior to the referral event than not (34.1%; p < 0.007). In addition, pregamers reported consuming more alcohol prior to the referral event than non-pregamers (t = −2.72, p = 0.006). However, there were no statistically significant differences between pregamers and non-pregamers in terms of white race, year in school, age, AUDIT scores, and typical drinks per week.

Table 1.

Group comparisons for Pre-gamers (n = 220) and non-Pregamers (n = 296).

| Pregamers N (%) | Non-Pregamers N (%) | χ2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Female | 101 (45.9) | 101 (34.1) | 7.36 | 0.007 |

| White | 179 (81.4) | 231 (78.0) | 0.85 | 0.36 |

| Freshman | 117 (53.2) | 140 (42.3) | 1.77 | 0.17 |

| Pregamers M (SD) | Non-Pregamers M (SD) | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 19.30 (1.46) | 19.44 (1.66) | 0.97 | 0.21 |

| Alcohol Use Variables | ||||

| AUDIT Score | 8.05 (3.32) | 8.05 (3.51) | −1.54 | 0.12 |

| Number of drinks prior to the referral event | 7.60 (4.33) | 6.50 (4.66) | −2.72 | 0.006 |

| Number of drinks in typical week | 10.71 (6.86) | 9.63 (6.86) | −1.75 | 0.08 |

Note. AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test.

Table 2 depicts a group comparison of participants who received medical attention on the day of the referral event (n = 151; 29.3%) with those participants who did not. Of the students who received medical attention, 49.7% were female, 79.5% were white, and 36.4% were freshmen. Additionally, participants who received medical attention reported consuming about twice the number of drinks prior to the referral event (t = −10.83, p < 0.001) and perceived their experience as more aversive (t = −7.33, p < 0.001). Of those who reported pregaming prior to the referral, participants who received medical attention reported consuming more drinks while pregaming when compared to participants who did not receive medical attention (t = −4.51, p < 0.001) and also had higher AUDIT scores (t = −4.71, p < 0.001). However, there was not a significant difference in the number of drinks consumed in a typical week between students who received medical attention and those who did not.

Table 2.

Group comparisons for participants who received medical attention (n = 151) and those who did not receive medical attention the day of their referral event (n = 365).

| Received Medical Attention N (%) | Did Not Receive Medical Attention N (%) | χ2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Female Gender | 75 (49.7) | 127 (34.8) | 9.92 | 0.002 |

| White | 108 (71.5) | 302 (82.7) | 8.23 | 0.004 |

| Freshman | 55 (36.4) | 202 (55.3) | 15.29 | <0.001 |

| Received Medical Attention M (SD) | Did Not Receive Medical Attention M (SD) | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 19.89 (1.85) | 19.17 (1.41) | −4.62 | <0.001 |

| Alcohol Use Variables | ||||

| AUDIT Score | 9.34 (3.25) | 7.81 (3.41) | −4.71 | <0.001 |

| Number of drinks prior to the referral event | 10.02 (4.05) | 5.71 (4.13) | −10.83 | <0.001 |

| Number of drinks consumed while pregaming* | 6.73 (3.57) | 4.58 (3.26) | −4.51 | <0.001 |

| Number of drinks in typical week | 9.62 (6.24) | 10.28 (7.24) | 0.98 | 0.32 |

| Event Experience | ||||

| Aversiveness of the event (emotional/physical effect of the event) | 16.69 (4.22) | 13.49 (4.63) | −7.33 | <0.001 |

Note.

only 220 participants who reported pregaming prior to the referral were asked to answer this question. AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test.

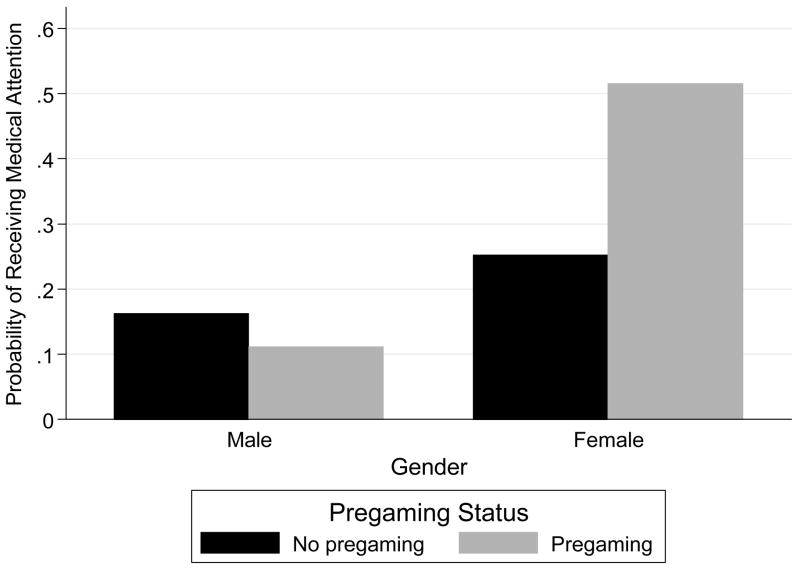

Logistic regression was employed to further understand the relationship between pregaming, gender, and medical attention on the day of the referral event after controlling for other variables (Table 3). Results indicated that female gender, but not pregaming, was significantly related to requiring medical attention (OR = 3.41, CI = [1.99–5.84]). However, the female X pregaming interaction variable (OR = 4.88, CI = [1.84–12.92]) qualified this relationship and indicated that gender significantly moderated the effect of pregaming on receiving medical attention. Thus, these results indicate that female students who pregamed the day of the referral event were at a significantly increased risk of receiving medical attention compared to male participants who pregamed (Figure 1).

Table 3.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis of characteristics associated with increased risk of receiving alcohol-use related medical treatment

| B | Wald statistic | OR | [95% CI] | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.21 | 8.32 | 1.23 | [1.07–1.42] | 0.004 |

| Female Gender | 1.23 | 20.03 | 3.41 | [1.99–5.84] | <0.001 |

| White | −0.83 | 7.99 | 0.44 | [0.25–0.78] | 0.005 |

| AUDIT Score | 0.14 | 9.55 | 1.15 | [1.05–1.26] | 0.002 |

| Number of drinks in typical week | −0.08 | 12.86 | 0.92 | [0.88–0.96] | <0.001 |

| Number of drinks prior to the referral event | 0.29 | 69.59 | 1.34 | [1.25–1.43] | <0.001 |

| Pregaming | 0.20 | 0.61 | 1.22 | [0.74–1.99] | 0.44 |

| Female and pregaming interaction | 1.59 | 10.18 | 4.88 | [1.84–12.92] | 0.001 |

Note. AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test

Figure 1.

Probability of receiving medical attention on the day of the referral event by pregaming status and gender.

Comment

In this study, one in four students who were referred for an alcohol intervention also received medical attention on the day of the referral event, and several factors are associated with this serious event. Of the students with a referral event, those who received medical attention were slightly older in age than those who did not receive medical attention, had higher AUDIT scores, consumed approximately twice as many drinks prior to the referral event, consumed a greater number of drinks while pregaming, and found the referral event to be aversive. However, in the multivariate analysis, drinking fewer drinks in a typical week was associated with an increased risk of receiving medical attention after controlling for other variables. While the odds ratio for drink per week was modest, this finding also suggests that students are lighter drinkers may be at heightened risk for needing medical attention due to drinking after controlling for other variables.

Pregaming was prevalent, with 43% of participants reported pregaming on the day of their referral event. In general, sanctioned students were more likely to be male, reported consuming more alcohol prior to the referral event than those who did not pregame, reported consuming about 5 drinks while pregaming (thus exceeding the criteria for heavy episodic drinking on this occasion alone). Given that limited research has quantified the number of drinks consumed on a pregaming occasion using diverse measures and samples, it is difficult to determine whether the number of drinks consumed during pregaming by this sample is higher than normal. That said, the number of drinks consumed while pregaming is on the higher end of the mean number of drinks (i.e., approximately 2–5 drinks) consumed on a typical pregaming event by undergraduate students.7,11,26–28 Interestingly, on average, participants who engaged in pregaming continued to drink after pregaming, but it is notable that the majority (70%) of drinks consumed prior to the referral event were consumed while pregaming. In addition, pregamers reported drinking slightly more alcohol in a typical week than those participants who did not pregame. The finding that pregamers consume more alcohol than non-pregamers is consistent with previous research.5,7

Perhaps the most compelling and clinically relevant finding was that pregaming in and of itself was not significantly related to receiving medical attention, which contradicts previous research linking pregaming with increased rates of alcohol-related consequences.7,9–11 Instead, females who pregamed were significantly more likely to require medical attention than males who pregamed. Specifically, female students who did not pregame had approximately a 25% risk of receiving medical attention, whereas female students who pregamed had a two-fold increase in the probability of receiving medical attention. The precise risk conferred by this combination of gender and pregaming does not appear to be related to the number of drinks consumed prior to the referral event.

Clinical Implications

These results are relevant to current clinical work with college students. Currently, there are no interventions with evidence of efficacy to reduce pregaming. In order to reduce pregaming, comprehensive interventions on multiple levels are needed at the environmental, intrapersonal, and interpersonal level. At the environmental level, increased patrol, enforcement of laws (e.g., minimum drinking age and responsible beverage service), and more stringent laws (e.g., increased fines) for heavy drinking in locations and destinations where pregaming is common (e.g., dormitories, social and sporting events) may be beneficial. Another possible strategy would be to establish breath test requirements upon entering a campus event.6 However, pregaming can also occur on private locations off campus, often out of sight of campus officials and police, making it difficult to intervene.

In addition, interventions are needed to reduce pregaming, especially pregaming by female students, may help reduce the number of students who require medical attention for alcohol-related conditions. Targeted messages about the increased risk for women, students with higher AUDIT scores, and lighter drinkers for incoming and matriculated students may increase awareness of the negative consequences from pregaming. In addition, interventions could include information about the risks associated with pregaming or about the increased risk for women and lighter drinkers in an intervention for incoming and matriculated college students. For example, female students’ pregaming not only place them at risk for requiring medical attention, but likely also increases their risk of being victimized while transitioning to a new environment after drinking.29 Such information could be delivered in the context of a parent-based intervention or brief motivational interview.19,30

Limitations

The findings of the study should be considered in the context of some limitations. First, given that this study had a low response rate and these data were drawn from one university, results may not generalize to other colleges in other regions of the country. Second, this study is cross-sectional in nature, only includes students who received an alcohol referral, and demographics (gender and race/ethnicity) of this sample are discrepant from the overall campus profile. A large-scale, representative sample, and prospective study using event-level data (e.g., daily drinking diaries) is needed to help evaluate predictors of receiving medical attention for alcohol-related complications. Third, the students in this study self-reported whether they pregamed, the number of drinks they consumed on the day of the referral event, and the number of drinks they consumed in a typical week. Fourth, this study did not collect biological markers of alcohol use. Whereas self-reported data poses a limitation to the study as data is dependent on the validity of student responses, it is important to note that self-report data has not been found to be significantly biased.31 Finally, this study did not collect information about the type of medical attention received by the students and the severity of their medical issues.

Conclusions

In summary, these results provide preliminary support for pregaming as a risk factor for an increased likelihood of receiving medical attention during the referral. Overall, students at greatest risk for requiring medical attention were female students who engaged in pregaming on the day of the referral event. In light of this finding, it is recommended that future research be conducted to identify efficacious interventions to reduce pregaming, especially by females, in order to help reduce alcohol-related consequences.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This research was supported by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health (NIH), through Grant UL1RR033184 and KL2RR033180 to John Hustad. Brian Borsari’s contribution to this manuscript was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grants R01-AA015518 and R01-AA017874.

References

- 1.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Alcohol use and alcohol use disorders in the United States: Main findings from the 2001–2002 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hingson RW, Zha W, Weitzman ER. Magnitude of and the trends in alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18–24, 1998–2005. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2009;(Suppl No. 16):12–20. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.White AM, Hingson RW, Pan IJ, Yi HY. Hospitalizations for alcohol and drug overdoses in young adults ages 18–24 in the United States, 1999–2008: Results from the nationwide inpatient sample. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2011;72:774–786. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnett NP, Tevyaw TO, Fromme K, et al. Brief alcohol interventions with mandated or adjudicated college students. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004 Jun;28:966–975. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000128231.97817.c7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borsari B, Boyle KE, Hustad JTP, Barnett NP, O’Leary Tevyaw T, Kahler CW. Drinking before drinking: Pre-gaming and drinking games in mandated students. Addict Behav. 2007:2694–2705. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zamboanga BL, Casner HG, Olthuis JV, et al. Knowing where they’re going: destination-specific pregaming behaviors in a multiethnic sample of college students. J Clin Psychol. 2013;69:383–396. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Read JP, Merrill JE, Bytschkow K. Before the party starts: Risk factors and reasons for ‘pregaming’ in college students. J Am Coll Health. 2010;58:461–472. doi: 10.1080/07448480903540523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): An effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Arch Intern Med. 1998 Sep 14;158:1789–1795. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barnett NP, Orchowski LM, Read JP, Kahler CW. Predictors and consequences of pregaming using day- and week-level measurements. Psychol Addict Behav. 2013 Dec;27:921–933. doi: 10.1037/a0031402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paves AP, Pedersen ER, Hummer JF, Labrie JW. Prevalence, social contexts, and risks for prepartying among ethnically diverse college students. Addict Behav. 2012;37:803–810. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Labhart F, Graham K, Wells S, Kuntsche E. Drinking before going to licensed premises: An event-level analysis of predrinking, alcohol consumption, and adverse outcomes. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013;37:284–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barry AE, Stellefson ML, Piazza-Gardner AK, Chaney BH, Dodd V. The impact of pregaming on subsequent blood alcohol concentrations: An event-level analysis. Addict Behav. 2013;38:2374–2377. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barry AE, Stellefson ML, Piazza-Gardner AK, Chaney BH, Dodd V. The impact of pregaming on subsequent blood alcohol concentrations: An event-level analysis. Addict Behav. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Binge drinking: A serious, under-recognized problem among women and girls. 2013 http://www.cdc.gov/features/vitalsigns/bingedrinkingfemale/index.html.

- 15.Borsari B, Hustad JTP, Mastroleo NR, et al. Addressing alcohol use and problems in mandated college students: A randomized clinical trial using stepped care. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012 Dec;80:1062–1074. doi: 10.1037/a0029902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pedersen ER, LaBrie J. Drinking game participation among college students: Gender and ethnic implications. Addict Behav. 2006;31:2105–2115. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hummer JF, Napper LE, Ehret PE, LaBrie JW. Event-specific risk and ecological factors associated with prepartying among heavier drinking college students. Addict Behav. 2013 Mar;38:1620–1628. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merrill JE, Vermont LN, Bachrach RL, Read JP. Is the pregame to blame? Event-level associations between pregaming and alcohol-related consequences. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2013;74:757. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dimeff LA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Marlatt GA. Brief alcohol screening and intervention for college students (BASICS): A harm reduction approach. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bradley KA, McDonell MB, Bush K, Kivlahan DR, Diehr P, Fihn SD. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions: Reliability, validity and responsiveness to change in older male primary care patients. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:1842–1849. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb03991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barnett NP, Monti PM, Spirito A, et al. Alcohol use and related harm among older adolescents treated in an emergency department: The importance of alcohol status and college status. J Stud Alcohol. 2003 May;64:342–349. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Longabaugh R, Minugh PA, Nirenberg TD, Clifford PR, Becker B, Woolard R. Injury as a motivator to reduce drinking. Acad Emerg Med. 1995;2:817–825. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1995.tb03278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chartier K, Caetano R. Ethnicity and health disparities in alcohol research. Alcohol Res Health. 2010;33:152–160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 3. New York: Harper Collins College Publishers; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 26.DeJong W, DeRicco B, Schneider SK. Pregaming: An exploratory study of strategic drinking by college students in Pennsylvania. J Am Coll Health. 2010 Jan 29;58:307–316. doi: 10.1080/07448480903380300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burger JM, LaSalvia CT, Hendricks LA, Mehdipour T, Neudeck EM. Partying before the party gets started: The effects of descriptive norms on pregaming behavior. Basic Appl Soc Psych. 2011 Jul 01;33:220–227. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pedersen ER, LaBrie J. Partying before the party: Examining prepartying behavior among college students. J Am Coll Health. 2007 Nov 01;56:237–245. doi: 10.3200/JACH.56.3.237-246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Testa M, Hoffman JH. Naturally occurring changes in women’s drinking from high school to college and implications for sexual victimization. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2012 Jan;73:26–33. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Turrisi R, Larimer ME, Mallett KA, et al. A randomized clinical trial evaluating a combined alcohol intervention for high-risk college students. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2009 Jul;70:555–567. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Borsari B, Muellerleile P. Collateral reports in the college setting: A meta-analytic integration. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:826–838. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00902.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]