Abstract

The advent of Darwinian evolution required the emergence of molecular mechanisms for heritable variation of fitness. One model for such a system involves competing protocell populations, each consisting of a replicating genetic polymer within a replicating vesicle. In this model, each genetic polymer imparts a selective advantage to its protocell by, for example, coding for a catalyst that generates a useful metabolite. Here, we report a partial model of such nascent evolutionary traits in a system consisting of fatty acid vesicles containing a dipeptide catalyst, which catalyzes the formation of a second dipeptide. The newly-formed dipeptide binds to vesicle membranes, imparting enhanced affinity for fatty acids, thus promoting vesicle growth. The catalyzed dipeptide synthesis proceeds with higher efficiency in vesicles than in free solution, further enhancing fitness. Our observations suggest that, in a replicating protocell with an RNA genome, ribozyme-catalyzed peptide synthesis might have been sufficient to initiate Darwinian evolution.

Introduction

Modern cells are thought to have evolved from much earlier protocells – simple replicating chemical systems, composed of a cell membrane and an encapsulated genetic polymer, that were the first cellular systems capable of Darwinian evolution1. Evolvability may have emerged in such systems via competition between protocells for a limiting resource2, 3. Since protocells lacked the complex biochemical machinery of modern cells, such competition was necessarily based on simple chemical or physical processes4. In order to gain further insight into such competitive processes, a variety of model protocell systems have been developed. Fatty acid vesicles have been widely employed as models of early protocellular systems5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 because fatty acids can be generated in plausibly prebiotic scenarios, and because membranes based on fatty acids have physical properties that are well suited to primitive forms of life12, 13. The presence of small molecules can induce size changes and fusion of lipid vesicles14, 15, and it has been previously shown that a membrane-based reaction can drive size changes of self-assembled lipid vesicles16.

The nature of the primordial genetic material remains uncertain; competing schools of thought support either RNA or some alternative nucleic acid as a progenitor of RNA. Irrespective of the nature of the original genetic material, an important question in considering the origins of cellular competition is how that genetic material could impart a selective advantage to a primitive protocell. An early model17 for such a scenario postulated an autocatalytic self-replicating genetic material, such as an RNA replicase, that would accumulate within vesicles at a rate corresponding to its catalytic efficiency. Mutations leading to greater replicase activity would result in a more rapid increase in internal RNA concentration and thus internal osmotic pressure, which would lead to faster vesicle swelling, which in turn would drive competitive vesicle growth. This model was supported by experimental observations that osmotically swollen vesicles could grow by absorbing fatty acid molecules from the membranes of surrounding relaxed vesicles17. Although the simple physical link between mutations leading to faster replication of the genetic material, and the consequent osmotic swelling and vesicle growth is attractive, this model suffers from the lack of a plausible mechanism for the division of osmotically swollen vesicles. More recently, we have observed that low levels of phospholipids can drive the competitive growth of fatty acid vesicles, in a manner that circumvents this problem by causing growth into filamentous structures that divide readily in response to mild shear stresses18. This model implies that a catalyst for phospholipid synthesis, such as an acyltransferase ribozyme, would impart a large selective advantage to its host protocell because faster growth, coupled with division, would result in a shorter cell cycle. A model system illustrating the potential of an encapsulated catalyst to drive vesicle growth in a similar manner would therefore be a significant step towards realizing a complete model of the origin of Darwinian evolution.

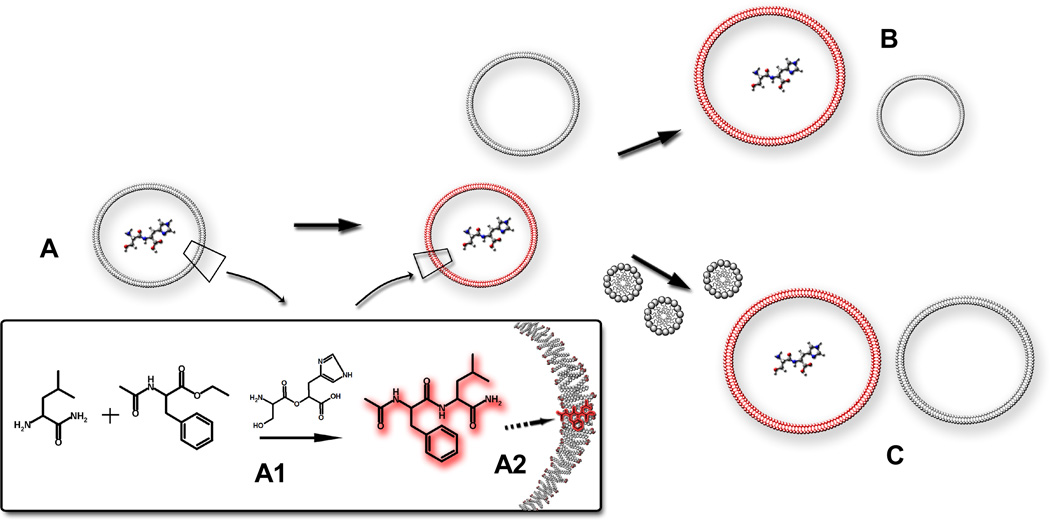

Here, we show that the simple dipeptide catalyst seryl-histidine (Ser-His) can drive vesicle growth through the catalytic synthesis of a hydrophobic dipeptide, N-acetyl-L-phenylalanine-leucinamide (AcPheLeuNH2), which localizes to the membrane of model protocells and drives competitive vesicle growth in a manner similar to that previously demonstrated for phospholipids. Ser-His has previously been shown to catalyze the formation of peptide bonds between amino acids and between PNA monomers19, 20. Although Ser-His is a very inefficient and non-specific catalyst, we have found that Ser-His generates higher yields of peptide product in the presence of fatty acid vesicles. As a result, vesicles containing the catalyst generate sufficient reaction product to exhibit enhanced fitness, as measured by competitive growth, relative to those lacking the catalyst [Figure 1]. We can therefore observe how a simple catalyst causes changes in the composition of the membrane of protocell vesicles and enables the origin of selection and competition between protocells.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of adaptive changes and competition between protocell vesicles.

A: Synthesis of AcPheLeuNH2 by catalyst encapsulated in fatty acid vesicles. A1: the dipeptide Ser-His catalyzes the reaction between substrates LeuNH2 and AcPheOEt, generating the product of the reaction, AcPheLeuNH2. A2: product dipeptide AcPheLeuNH2 localizes to the bilayer membrane. B: Vesicles with AcPheLeuNH2 in the membrane grow when mixed with vesicles without dipeptide, which shrink. C: Vesicles with AcPheLeuNH2 in the membrane grow more following micelle addition than vesicles without the dipeptide.

Results

Vesicles Enhance Ser-His synthesis of AcPheLeuNH2

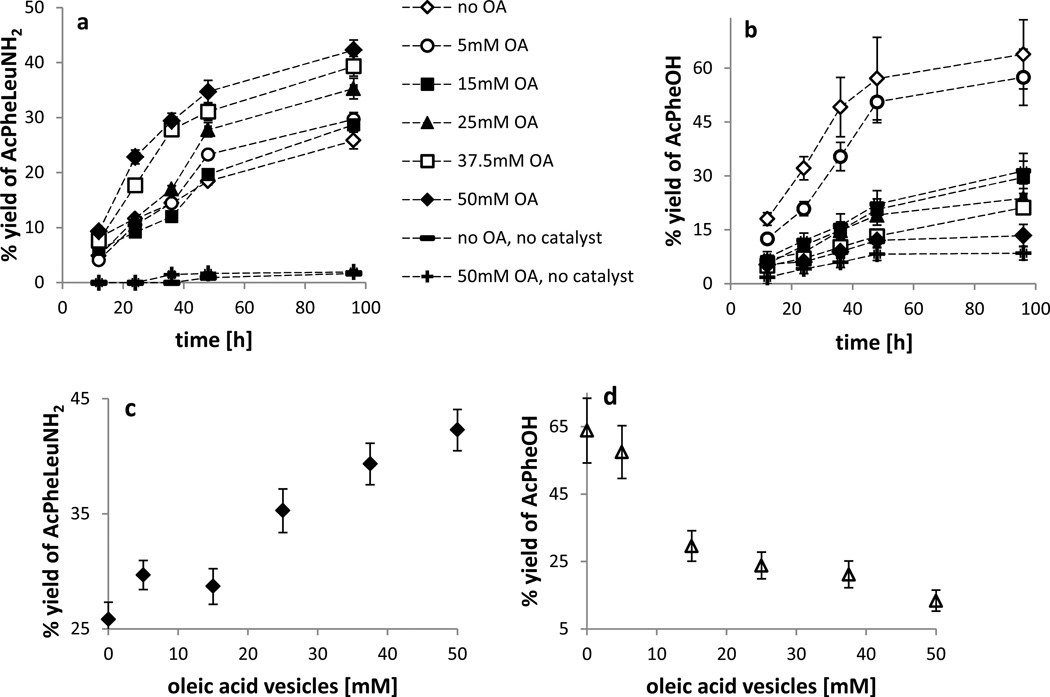

The catalytic efficiency of the dipeptide Ser-His is extremely low, and quantitation is difficult due to precipitation of the hydrophobic product19. In addition, Ser-His appears to be a more effective catalyst of the hydrolysis of the AcPheOEt ethyl ester than of peptide bond formation, which further limits product yield. We decided to characterize the Ser-His catalyzed synthesis of AcPheLeuNH2 in the presence of fatty acid membranes, which we suspected would dissolve the product and prevent precipitation. We also suspected that co-localizing the hydrophobic substrates for the synthesis of the AcPheLeuNH2 within or on fatty acid membranes might improve the yield and possibly minimize substrate hydrolysis. We found that the Ser-His catalyst produced progressively more AcPheLeuNH2 in the presence of increasing concentrations of oleate vesicles, with the conversion of substrate to product increasing from 25% in free solution to 44% in the presence of 50 mM oleate vesicles [Figure 2A]. The presence of vesicles also diminished substrate hydrolysis from 65% in free solution to 10% in the presence of 50 mM oleate vesicles [Figure 2B]. One possible explanation for these results is that the hydrophobic substrates partition to the membrane, allowing the reaction to occur at the solvent-lipid bilayer interface, or even within the bilayer, thereby minimizing ester hydrolysis and enhancing product formation.

Figure 2. More dipeptide synthesis and less substrate hydrolysis as a result of Ser-His catalysis in the presence of fatty acid vesicles.

A: Ser-His catalyzed synthesis of AcPheLeuNH2 is faster, and results in a higher yield, in the presence of increasing concentrations of oleate vesicles. B: Ser-His catalyzed hydrolysis of the substrate AcPheOEt is progressively slower in the presence of increasing concentrations of oleate vesicles. C: yield of dipeptide AcPheLeuNH2 vs. concentration of oleate vesicles. D: yield of hydrolyzed substrate AcPheOH vs concentration of oleate vesicles in the same reactions. All experiments: 10mM of each substrate, 5 mM Ser-His catalyst, 0.2 M Na+-bicine pH 8.5, 37 °C. In these experiments, both the Ser-His catalyst and the AcPheOEt and LeuNH2 substrates were present both inside and outside of the oleate vesicles.

We also studied the catalysis of AcPheLeuNH2 synthesis by the tripeptide Ser-His-Gly, which is a less effective catalyst than Ser-His, producing about half as much product dipeptide in the presence of oleate vesicles (with 50 mM vesicles, the yield of AcPheLeuNH2 synthesis from 10 mM of each substrate and with 5mM Ser-His-Gly was 27% after 96 hours in 0.2 M Na+-bicine, pH 8.5 at 37°C, compared to 44% for Ser-His).

Slow exchange of Ser-His and AcPheLeuNH2 peptides between vesicles

Competition between protocells is expected to result in the selection of adaptations that are beneficial to the protocells in which those adaptations originated. Thus, the adaptive property must not be shared with other protocells in a population. It was therefore important to establish, in our simplified model system, that the Ser-His catalyst and the dipeptide product AcPheLeuNH2 remain localized within the vesicles that originally contained the catalyst.

We first asked whether the hydrophobic peptide AcPheLeuNH2 remained localized within an initial set of vesicles, or exchanged between vesicles. Our results indicate that dipeptide AcPheLeuNH2 exchanges only slowly between vesicles when the vesicles are prepared from oleic acid plus 0.5 equivalents of NaOH, with >80% remaining in the original vesicles over a period of 8h [Figure S1A]. In contrast the presence of additional buffer (0.2 M Na+-bicine, pH 8.5) leads to accelerated exchange of peptide between vesicles. All subsequent experiments were therefore carried out over time scales that were short relative to peptide exchange. We performed similar experiments to show that encapsulated Ser-His and Ser-His-Gly were also retained within vesicles and did not exchange between vesicles [Figure S1B and S1C].

Interaction of AcPheLeuNH2 with Membranes

As a means of examining the interaction of AcPheLeuNH2 with the vesicle membrane, we measured the fluorescence anisotropy of the molecular probe 1,6-diphenyl-1,3,5-hexatriene (DPH) as a probe of membrane order. We found that the fluidity of oleate membranes decreases in the presence of the dipeptide AcPheLeuNH2 [Figure S2], similar to the previously observed effects of phospholipids on oleate membrane fluidity18. The presence of the hydrophobic dipeptide also decreases the off-rate of fatty acids from fatty acid membranes [Figure S9]. We found that the desorption rate of oleate from fatty acid vesicles decreases with increasing concentrations of dipeptide AcPheLeuNH2 in the membrane, consistent with previously reported observations of the effects of phospholipid on fatty acid vesicles18. The similar effect of AcPheLeuNH2 and phospholipid on fatty acid desorption suggested that the dipeptide might, like phospholipid, also drive vesicle growth at the expense of surrounding pure fatty acid vesicles.

We also examined the effects of the peptide on membrane permeability; neither AcPheLeuNH2, nor reaction substrates or Ser-His catalyst affected vesicle permeability to the small molecule calcein or to oligonucleotides [Figure S4].

Competitive Growth of Vesicles Containing AcPheLeuNH2

Given that AcPheLeuNH2 decreases membrane fluidity and fatty acid dissociation in a manner similar to that previously observed for phospholipids, we investigated whether AcPheLeuNH2 also affected membrane growth dynamics. The dipeptide AcPheLeuNH2 is practically insoluble in water, so the dilution of the insoluble peptide fraction present in fatty acid membrane is entropically favored. That, in addition to the decreased fatty acid off rate (monomer efflux from the membrane), could lead to the accumulation of fatty acids in the dipeptide-containing membrane, when fatty acid vesicles without the dipeptide are present to provide the oleate monomer.

We monitored vesicle growth using a FRET-based assay for the real-time measurement of membrane surface area21, in which the dilution of membrane localized fluorescent donor and acceptor dyes causes decreased FRET (see the Materials and Methods for details). We found that vesicles containing AcPheLeuNH2 grew at the expense of those lacking this dipeptide, when the two were incubated together [Figure 3A, Figure 7A]. Similarly, when “fed” with added fatty acid micelles, AcPheLeuNH2-containing vesicles grew preferentially, taking up more micelles than vesicles without dipeptide [Figure 3B, Figure 7B]. The time course of competitive vesicle growth, and the corresponding time course of shrinking of vesicles without the dipeptide, match previously reported phospholipid-driven growth, suggesting a similar fatty acid exchange mechanism [Figure S3].

Figure 3. Competition between vesicles with and without the hydrophobic dipeptide AsPheLeuNH2.

A: Self-buffered oleate vesicles (i.e. no added buffer or salt) containing the indicated mol% of AcPheLeuNH2 were mixed with 1 or 2 equivalents of empty vesicles. After 15min the surface area was measured using the FRET-based assay. Filled markers: with FRET dyes on vesicles with AcPheLeuNH2 growth is observed; open markers: with FRET dyes on vesicles without AcPheLeuNH2 shrinkage is observed. B: Competition for added oleate micelles in a high-salt environment (0.2M Na+-bicine, pH=8.5). Equal amounts of vesicles with and without AcPheLeuNH2 were mixed, after which oleate micelles were added, and the surface area measured after 15 min. Filled markers: FRET dyes on vesicles with AcPheLeuNH2, growth is observed. Open markers: FRET dyes on vesicles without AcPheLeuNH2, less growth is observed than for the corresponding peptide-containing sample. This experiment could only be carried out in the presence of added buffer, otherwise the alkaline oleate micelles (with 1 equivalent of NaOH per fatty acid, vs. the ½ equivalent per fatty acid in a vesicle) quickly and excessively changed the pH of the mixture, destabilizing the pre-formed vesicles.

Figure 7. Competition between populations of protocell vesicles.

A: Vesicle size changes following 1:1 mixing of indicated vesicle populations. B: Vesicle size changes following competitive oleate uptake after addition of 6 equivalents of oleate micelles. Populations of vesicles contained either Ser-His (S-H), Ser-His-Gly (S-H-G), or no catalyst, as indicated. All vesicle populations were incubated separately with amino acid substrates for 48h to allow for synthesis of hydrophobic dipeptide product prior to mixing. C: Competition between vesicles containing different catalysts. Each sample contained two or three populations of vesicles, as indicated, in a 1:1 or 1:1:1 ratio. In each case, the FRET dye pair was placed in one of the populations, to measure the size change after the reaction. Vesicles containing Ser-His outcompete vesicles containing Ser-His-Gly.

Surprisingly, we only observed competitive growth between vesicles with and without peptide in self-buffered vesicles (vesicles with only the carboxyl groups of the fatty acids as buffering agents). Following the addition of ½ molar equivalent of NaCl to self-buffered vesicles (relative to oleate), less than half as much growth was observed, and when 1 equivalent of NaCl was added to self-buffered vesicles, no significant competitive growth was observed [Figure 4]. The addition of 1 equivalent of tetramethylammonium chloride (TMAC) affected the observed surface area change to a lesser extent (~ 20% inhibition) [Figure 4], suggesting that surface ionic interactions strongly affect fatty acid exchange processes. In contrast to competitive vesicle-vesicle growth, we were only able to measure competitive micelle-induced growth in high-salt Na+-bicine buffered vesicle samples [Figure 3B].

Figure 4.

* +: vesicles in high salt buffer (0.2M Na+-bicine, pH 8.5), −: self-buffered vesicles (50 mol% NaOH)

** −: no salt added; A: 50 mol% NaCl (relative to oleate), B: 100 mol% NaCl, C: 100 mol% TMAC

Inhibitory effect of salt and buffer on competitive growth of vesicles.

Equal amounts of oleate vesicles with and without 10 mol% AcPheLeuNH2 were mixed and growth (or shrinkage) was monitored by a FRET-based surface area assay. Black columns: vesicles containing AcPheLeuNH2 were labeled with FRET dyes, and growth was monitored. White columns: vesicles without AcPheLeuNH2 were labeled with FRET dyes, and shrinkage was monitored. The presence of either salt or buffer strongly inhibits both growth and shrinkage following mixing of vesicles. Error bars indicate SEM (N=5).

In a preliminary effort to correlate structure and activity, we examined the effect of several different small peptides on vesicle growth. While other small hydrophobic dipeptides (e.g., Phe-Phe) led to some competitive growth, none was as efficient as AcPheLeuNH2 [Figure S5]. N-terminal peptide acetylation was quite important, as Phe-LeuNH2 was less effective than AcPheLeuNH2. LogPcalc (calculated logarithm of octanol-water partition coefficient) values suggest that the more lipophilic peptides induce a greater competitive growth effect.

Competitive growth can facilitate protocell vesicle division

It has previously been shown that the growth of multilamellar oleate vesicles following micelle addition22 results in the development of fragile, thread-like structures that can easily fragment, producing daughter vesicles. Similar filamentous growth of phospholipid containing vesicles is observed following mixing with excess pure fatty acid vesicles17. We therefore asked whether competitive growth caused by the presence of the hydrophobic AcPheLeuNH2 can also result in the formation of filamentous vesicles and subsequent division. We found that initially spherical vesicles with 10 mol% of AcPheLeuNH2 in their membranes develop into thread-like filamentous vesicles after mixing with 100 equivalents of empty oleate vesicles [Figure 5A–B]. Gentle agitation of the filamentous vesicles resulted in vesicle division into multiple smaller daughter vesicles [Figure 5C]. We have previously shown that division of filamentous vesicles occurs without significant loss of encapsulated content, and therefore is a plausible mechanism for spontaneous protocell division17, 23.

Figure 5. Vesicle growth and division.

A: Large multilamellar vesicles with 0.2 mol% Rh-DHPE dye and 10 mol% of dipeptide AcPheLeuNH2 in the membrane are initially spherical. B: 10 minutes after mixing with a 100 equivalents of unlabeled, empty oleic acid vesicles without the dipeptide, thread-like filamentous structures develop. The development of filamentous vesicles from initially spherical vesicles is caused by the more rapid increase of surface area relative to volume increase, which is osmotically controlled by solute permeability. To recreate this effect in the absence of additional buffer, we used sucrose, a non-ionic osmolyte to provide an osmotic constraint on vesicle volume. C: after gentle agitation, the filamentous vesicles fragment into small daughter vesicles. Scale bar, 10 um.

Competitive vesicle growth induced by Ser-His catalyzed synthesis of AcPheLeuNH2

The results described above show that Ser-His can catalyze the formation of AcPheLeuNH2 in vesicles and that AcPheLeuNH2 can cause or enhance vesicle growth. We sought to combine these phenomena to effect Ser-His-driven vesicle growth. We prepared oleate vesicles containing encapsulated Ser-His dipeptide and FRET dyes in their membranes. Unencapsulated catalyst was removed either by dialysis against a vesicle solution of the same amphiphile concentration lacking the catalyst, or, alternatively, by purification on a Sepharose 4B size exclusion column. Purified vesicles containing 5 mM Ser-His were then mixed with 10 mM of the amino acid substrates AcPheOEt and LeuNH2, and incubated at 37 °C for 24 to 48 hours to allow for synthesis of the dipeptide AcPheLeuNH2. HPLC analysis of vesicles after 48h of incubation showed that in vesicles with Ser-His the dipeptide product AcPheLeuNH2 was synthesized with 28% yield; parallel experiments with vesicles containing Ser-His-Gly showed that the product was synthesized in 16% yield [Figure S8]. After incubation, samples with catalyst were mixed with one equivalent of oleate vesicles that had been incubated with amino acid substrates, but without Ser-His catalyst. Vesicle size changes were measured following mixing using the FRET assay for surface area, as described above. We found that vesicles containing the peptide catalyst Ser-His that had been incubated with substrates to allow for the accumulation of AcPheLeuNH2 increased in surface area by 24% when mixed with one equivalent of empty oleate vesicles. When the added empty oleate vesicles were labeled with FRET dyes, we saw a decrease in their surface area, as expected. In parallel experiments, vesicles lacking Ser-His, or incubated without substrates, did not grow following the addition of oleate vesicles [Figure 7A]. We also examined vesicles containing the less active catalyst Ser-His-Gly, which grew, but to a lesser extent than the Ser-His containing vesicles [Figure 7A].

We then examined the ability of Ser-His (and Ser-His-Gly) to enhance vesicle growth following AcPheLeuNH2 synthesis and then oleate micelle addition. As expected from previous experiments in which vesicles were prepared with AcPheLeuNH2 directly, vesicles in which AcPheLeuNH2 was synthesized internally also showed enhanced oleate uptake from added micelles, and they therefore grew more than empty vesicles [Figure 7B]. Vesicles prepared with Ser-His-Gly showed a similar but smaller growth enhancement.

AcPheLeuNH2-containing Vesicles Exhibit Enhanced Chemical Potential Generation During Competitive Micelle Uptake

As fatty acid vesicles grow, protonated fatty acid molecules flip across the membrane to maintain equilibrium between the inner and outer leaflets. Subsequent ionization of a fraction of the protonated fatty acids that flipped to the inside of the vesicle acidifies the vesicle interior, generating a pH gradient across the membrane. This pH gradient normally decays rapidly due to H+/Na+ exchange, but we have previously shown that by employing a membrane-impermeable counterion, such as arginine, the pH gradient can be maintained for many hours (t1/2 ≈ 16h)21. We have therefore used arginine as a counterion (arg+) to study the effect of AcPheLeuNH2 on the generation of a trans-membrane electrochemical potential during micelle-mediated vesicle growth.

In order to monitor the effect of the peptide on vesicle growth-induced pH gradient formation, we prepared two populations of vesicles in arg+-bicine buffer, one with and one without the hydrophobic dipeptide AcPheLeuNH2 in the membrane. Consistent with the enhanced surface area growth of AcPheLeuNH2-containing vesicles, the peptide-containing vesicles developed a transmembrane pH gradient that was twice as large as that seen in the vesicles lacking peptide, following growth induced by addition of oleate-arg+ micelles [Figure 6].

Figure 6.

Transmembrane pH gradient generated by growth of vesicles during competitive micelle uptake. Equal amounts of vesicles with and without 10 mol% AcPheLeuNH2 were mixed in high salt buffer (arg+ -bicine, pH=8.1), and 1 equivalent of arginine-oleate micelles was added to the mixture to initiate growth. Empty circles: the peptide-containing vesicles carried the pH-sensitive water-soluble dye HPTS encapsulated in the vesicle interior. Filled circles: the peptide-free vesicles contained the HPTS. In both experiments, the two vesicle populations were mixed together and incubated for 30 min. No competitive growth at this stage, since vesicles were in a high-salt arg+-bicine buffer. We then added 1 equivalent of oleate-arg+ micelles to the mixed vesicle sample, triggering growth of both sets of vesicles. We measured the change in pH inside the vesicles vs. time by monitoring the change in the fluorescence emission of the HPTS dye (see Materials and Methods). Vesicles containing AcPheLeuNH2 developed a larger trans-membrane pH gradient as a result of greater growth.

Competition between vesicles containing different catalysts

In order to examine competition between vesicles harboring peptides of varying catalytic efficiencies, we prepared self-buffered Ser-His-containing vesicles and Ser-His-Gly-containing vesicles and incubated them separately in the presence of substrates to allow for the synthesis of the hydrophobic dipeptide AcPheLeuNH2. These vesicles were then mixed, and after a 60min incubation the change in the surface area of vesicles labeled with dye was determined from the change in the FRET signal. The vesicles containing Ser-His increased in surface area, while those containing Ser-His-Gly shrunk. This directly demonstrates competition between protocells containing two catalysts of varying efficiency [Figure 7C]. In a separate experiment, we mixed vesicles with both catalysts and added one equivalent of empty oleate vesicles, to serve as a “feedstock” for the vesicles with the dipeptide AcPheLeuNH2. In this case, both vesicles with Ser-His and with Ser-His-Gly increased in size, but vesicles with Ser-His grew almost twice as much as those with Ser-His-Gly. This demonstrates that in case where “feedstock” is readily available (from empty vesicles), both populations of protocell grow, but the more efficient catalyst allows for more growth [Figure 7C].

Discussion

The ubiquitous role of proteins as the catalysts of metabolic reactions raises the question of the origins of protein enzymes. The fact that all modern proteins are synthesized through the catalytic activity of the RNA component of the large ribosomal subunit24 suggests that primitive enzymes might have been peptides synthesized by ribozymes. By extension, the earliest enzyme progenitors might have been simple peptides synthesized in a non-coding fashion by one or more ribozymes acting sequentially. If short, prebiotically available peptides played useful roles in the growth or division of early protocells, then there would have been a strong selective advantage conferred by ribozymes able to synthesize more of such useful peptides. We have found that a short hydrophobic peptide, whether supplied exogenously or synthesized internally, can confer a growth advantage to fatty acid vesicles. Thus, a ribozyme capable of synthesizing short hydrophobic peptides could accelerate protocell growth, thereby conferring a strong selective advantage. The short peptide Ser-His confers similar effects through its catalytic synthesis of the hydrophobic peptide product, supporting the idea that a ribozyme with similar catalytic activity would confer a selective advantage, but also raising the possibility that a ribozyme that made a catalytic peptide product could amplify its own efficacy through the indirect synthesis of the functional end-product. Similarly, a ribozyme that synthesized a peptide with nascent phospholipid synthase activity would confer a strong selective advantage through phospholipid-driven growth18. Because of the polarity of nucleic acids, ribozymes might have difficulty catalyzing reactions between membrane-localized substrates; thus the synthesis of intermediate catalytic peptides could be an effective strategy for the synthesis of membrane-modifying products. The hydrophobic environment found in the interior of vesicle bilayers could provide a favorable reaction milieu for the catalysis of many chemical reactions, similar to that afforded (in much more sophisticated fashion) by the interior of folded proteins in contemporary biochemistry. This speculation is supported by our observation that the presence of vesicles increases the yield of AcPheLeuNH2 from amino acid substrates in the presence of Ser-His as a catalyst. This increased yield most likely results from the greatly decreased extent of AcPheOEt substrate hydrolysis when it is localized to the hydrophobic membrane interior and is thereby protected from attack by water [Figure 2], much as labile intermediates are protected from water within the active sites of enzymes. Membrane localization of the leucyl-carboxamide substrate may also decrease the pKa of the N-terminal amino group, enhancing its reactivity by increasing the fraction of nucleophilic deprotonated amine. The phenomena of enhancing yields of chemical reactions by co-localizing substrates, altering pKas, and limiting side-reactions are likely to be observed for many other membrane-associated substrates, allowing protocells to start membrane-localized metabolism with assistance from very simple peptide catalysts.

We have described a laboratory model system designed to illustrate the principles of competition between protocells. Since the catalyst we used is not heritable, our system cannot yet evolve. Nevertheless, we have demonstrated adaptive changes arising from encapsulated primitive catalysts acting at the protocell level, as well as competition between populations of protocells containing two catalysts differing in primary structure (Ser-His and Ser-His-Gly). Direct vesicle-vesicle competitive growth is analogous to a predator-prey interaction, with one population acquiring nutrients from another population so that the “predatory” population grows while the “prey” population shrinks. The competitive micelle uptake is analogous to a “competition for feedstock” among two populations. It is interesting to note that, in the model system we have described, these two mechanisms operate under different environmental conditions, with direct competitive growth occurring only under low-salt conditions, while competitive micelle uptake occurs only under high-salt/buffer conditions. In each case, adaptive changes occur as a result of an encapsulated reaction, the rate of which is enhanced by an encapsulated catalyst. Thus, this system links intra-protocell chemistry (and catalysis) to the ability of a model protocell to adapt to selective pressure. Because AcPheLeuNH2 exchanges only slowly between vesicles, the presence of this hydrophobic dipeptide is truly adaptive, in that the product produced by the encapsulated catalyst remains with its original vesicle at least for a few hours, affording it an advantage - here, an enhanced affinity for membrane components, allowing for growth. Competitive protocell vesicle growth can also result, under certain circumstances, in the development of a higher trans-membrane pH gradient [Figure 6], which could potentially be linked to the development of useful energy sources for protocell metabolism 21. Furthermore, rapid competitive vesicle growth leads to the development of thread-like filamentous vesicles, which can subsequently divide into small daughter vesicles as a result of gentle agitation [Figure 5]. This process has previously been observed for oleate vesicles grown by either micelle addition22 or competitive lipid uptake driven by membrane composition4, and thus appears to be a general route to a cycle of growth and division. Here we have shown that growth can be induced by activity of a catalyst encapsulated within the protocell, thus bringing the system one step closer to an internally controlled cell cycle. If such a system exhibited heredity, for example, via the activity of a self-replicating, peptide bond-forming ribozyme, it would amount to a fully functioning protocell, capable of Darwinian evolution.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

J.W.S. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. This work was supported in part by NASA Exobiology grant NNX07AJ09G. We thank Drs. Aaron Engelhart, Christian Hentrich, Itay Budin and Raphael Wiezcorek for discussions and help with manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Both authors contributed to the design of the experiments and to writing the paper. Experiments were conducted by K.A.

Competing Financial Interests Statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Monnard PA, Deamer DW. Membrane self-assembly processes: steps toward the first cellular life. The Anatomical record. 2002;268(3):196–207. doi: 10.1002/ar.10154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Szathmary E, Demeter L. Group selection of early replicators and the origin of life. J Theor Biol. 1987;128(4):463–486. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5193(87)80191-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Szostak JW, Bartel DP, Luisi PL. Synthesizing life. Nature. 2001;409(6818):387–390. doi: 10.1038/35053176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Budin I, Szostak JW. Expanding roles for diverse physical phenomena during the origin of life. Annual review of biophysics. 2010;39:245–263. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.050708.133753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gebicki JM, Hicks M. Ufasomes are stable particles surrounded by unsaturated fatty acid membranes. Nature. 1973;243(5404):232–234. doi: 10.1038/243232a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hargreaves WR, Deamer DW. Liposomes from ionic, single-chain amphiphiles. Biochemistry. 1978;17(18):3759–3768. doi: 10.1021/bi00611a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oberholzer T, Wick R, Luisi PL, Biebricher CK. Enzymatic RNA replication in self-reproducing vesicles: an approach to a minimal cell. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 1995;207(1):250–257. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Apel CL, Deamer DW, Mautner MN. Self-assembled vesicles of monocarboxylic acids and alcohols: conditions for stability and for the encapsulation of biopolymers. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1559(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(01)00400-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Noireaux V, Libchaber A. A vesicle bioreactor as a step toward an artificial cell assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(51):17669–17674. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408236101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stano P, Luisi PL. Achievements and open questions in the self-reproduction of vesicles and synthetic minimal cells. Chem Commun (Camb) 2010;46(21):3639–3653. doi: 10.1039/b913997d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kurihara K, Tamura M, Shohda K, Toyota T, Suzuki K, Sugawara T. Self-reproduction of supramolecular giant vesicles combined with the amplification of encapsulated DNA. Nature chemistry. 2011;3(10):775–781. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deamer DW, Dworkin JP. Chemistry and physics of primitive membranes. Top Curr Chem. 2005;(259):1–27. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deamer DW, Barchfeld GL. Encapsulation of macromolecules by lipid vesicles under simulated prebiotic conditions. Journal of molecular evolution. 1982;18(3):203–206. doi: 10.1007/BF01733047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chiruvolu S, Warriner HE, Naranjo E, Idziak SH, Radler JO, Plano RJ, et al. A phase of liposomes with entangled tubular vesicles. Science. 1994;266(5188):1222–1225. doi: 10.1126/science.7973704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bard M, Albrecht MR, Gupta N, Guynn CJ, Stillwell W. Geraniol interferes with membrane functions in strains of Candida and Saccharomyces. Lipids. 1988;23(6):534–538. doi: 10.1007/BF02535593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suzuki K, Toyota T, Takakura K, Sugawara T. Sparkling Morphological Changes and Spontaneous Movements of Self-assemblies in Water Induced by Chemical Reactions. Chemistry Letters. 2009;38(11):1010–1015. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen IA, Roberts RW, Szostak JW. The emergence of competition between model protocells. Science. 2004;305(5689):1474–1476. doi: 10.1126/science.1100757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Budin I, Szostak JW. Physical effects underlying the transition from primitive to modern cell membranes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108(13):5249–5254. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100498108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gorlero M, Wieczorek R, Adamala K, Giorgi A, Schinina ME, Stano P, et al. Ser-His catalyses the formation of peptides and PNAs. FEBS Lett. 2009;583(1):153–156. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.11.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wieczorek R, Dorr M, Chotera A, Luisi PL, Monnard PA. Formation of RNA phosphodiester bond by histidine-containing dipeptides. Chembiochem : a European journal of chemical biology. 2013;14(2):217–223. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201200643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen IA, Szostak JW. Membrane growth can generate a transmembrane pH gradient in fatty acid vesicles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(21):7965–7970. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308045101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu TF, Szostak JW. Coupled Growth and Division of Model Protocell Membranes. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131(15):5705–5713. doi: 10.1021/ja900919c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhu TF, Adamala K, Zhang N, Szostak JW. Photochemically driven redox chemistry induces protocell membrane pearling and division. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109(25):9828–9832. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203212109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moore PB, Steitz TA. The roles of RNA in the synthesis of protein. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology. 2011;3(11):a003780. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.