Abstract

Objective

To evaluate costs and treatment benefits of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (RD) repair.

Design

A Markov model of cost-effectiveness and utility.

Participants

There were no participants.

Methods

Published clinical trials (index studies) of pneumatic retinopexy (PR), scleral buckling (SB), pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) and laser prophylaxis were used to quantitate surgical management and visual benefits. Markov analysis, with data from the Center of Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), was used to calculate adjusted costs of primary repair by each modality in a hospital-based and ambulatory surgery center (ASC) setting.

Main Outcome Measures

Lines of visual acuity (VA) saved, cost of therapy, adjusted cost of therapy, cost per line saved, cost per line-year saved, cost per quality-adjusted life years (QALY) saved.

Results

In the facility, hospital surgery setting, weighted cost for PR ranged from $3,726 to $5,901 depending on estimated success rate of primary repair. Weighted cost for SB was $6,770, for PPV was $7,940 and for laser prophylaxis was $1,955. The dollars per line saved ranged from $217 to $1,346 depending on the procedure. Dollars per line-year saved ranged from $11 to $67. Dollars per QALY saved ranged from $362 to $2,243.

In the non-facility, ASC surgery setting, weighted cost for PR ranged from $1,961 to $3,565 depending on the success rate of primary repair. The weighted costs for SB, PPV and laser prophylaxis were $4,873, $5,793 and $1,255, respectively. Dollars per line saved ranged from $139 to $982. The dollars per line-year saved ranged from $7–$49 and the dollars per QALY saved ranged from $232 to $1,637.

Conclusions

Treatment and prevention of RD is extremely cost-effective when compared to other treatment of other retinal diseases regardless of treatment modality. RD treatment costs did not vary widely, suggesting providers can tailor patient treatments solely on the basis of optimizing anticipated results since there were not overriding differences in financial impact.

Introduction

Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (RD), the most common type of retinal detachment, has long been the defining target of surgical retinal efforts.1 In 2009, the Medicare database reported a total of 21,762 RD repair procedures.2 Untreated, retinal detachment usually leads to substantial, frequently severe, permanent vision loss, that might be accompanied by painful hypotony and phthisis. Many highly successful treatment options constitute the standard armamentarium including scleral buckling (SB), vitrectomy (PPV), and pneumatic retinopexy (PR). Many clinical trials and series comparing these methods of retinal detachment repair have shown comparable success rates, but have enumerated factors that are helpful in choosing the most suitable technique for certain subsets of patients.3–19

Few studies comparing cost-effectiveness of retinal reattachment surgery to other ophthalmologic or general medical treatments, or among techniques have been published.14,19,20 Generally, cost considerations have not been a factor in clinical decision-making in choosing retinal reattachment treatments. Previous studies have outlined similar cost analyses for age-related macular degeneration (AMD),20 diabetic macular edema (DME)21 and retinal vein occlusion (RVO),22 but treatment of RD has never been subjected to such an analysis of various treatment options.

The purpose of the current report is to calculate parameters of cost-effectiveness using a Markov decision-tree analysis for the main methods of RD repair: PR, SB and PPV.

Methods

Representative index studies were identified to ascertain representative anatomic success rates for each treatment modality of RD repair including PR,8,14–19 SB,4–8,10–13 PPV with or without SB4–12 and laser prophylaxis of RD.23 Based on these studies our models assumed 60%, 75%, or 90% success for PR, 85% success for SB, and 90% success for PPV with or without SB. Medicare fee data for 2013 were acquired from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to ascertain the allowable cost (in United States dollars) associated with each procedure, study or office visit.24–28 The costs were calculated for both facility (hospital-based with surgery performed in a hospital operating room) practice in the geographic area of Miami, FL, and also for a non-facility (i.e. office based clinical services with surgery performance in an ambulatory surgery center (ASC)) in the same geographic area to demonstrate the range of potential reimbursement. The purpose in this dichotomy was to calculate the range of maximum and minimum possible incident costs for the various procedures. The permutations of a practice utilizing facility-based clinic visits with ASC-based surgery, and non-facility-based clinic visits and hospital based surgery would fall in between these limits. PR and laser prophylaxis costs were calculated as if done in an office, without the use of an operating room or anesthesiologist in both models. It should be noted, the differential of professional fees of facility versus non-facility costs is only relevant for clinical visits, not for surgical and treatment procedures.

The dollars per relative value unit (RVU) used (conversion factor) was $34.023 since that was the established rate for most of 2013.25 The cost for a given provider service is an equation that considers work (w) RVUs (professional fees), practice expense (pe) RVUs, and malpractice (mp) RVUs, each of which are subject to geographic modifiers that adjust for costs and relative malpractice risk.25

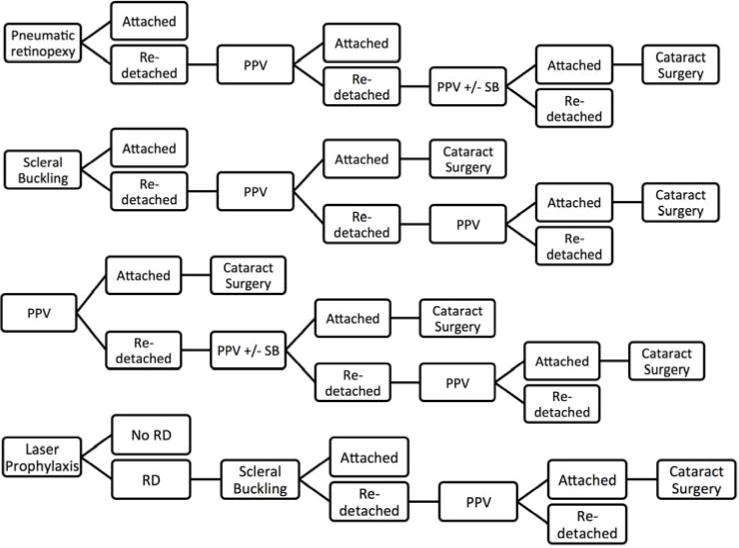

A Markov analysis29 was performed to generate a cost for each procedure based on the anatomic success rates of index studies, but also for three different hypothetical success rates for PR. Four hypothetical treatment groups were modeled and analyzed (Figure 1) for each of the two different practice setting permutations described above.

Figure 1. Decision Model Used in Markov Analysis.

PPV = pars plana vitrectomy, SB = scleral buckling. RD = retinal detachment. Phakic patients (assumed to be 70% of total cohort) were expected to require cataract surgery after PPV

The first model was treatment with PR (in an office, without hospital or anesthesia fees); failures were treated by PPV with or without SB (costs are the same), and any subsequent re-operations treated with PPV. The second model was treatment with SB; failures were treated by PPV, and subsequent failures treated with PPV. The third model was treatment with primary PPV; failures were treated by PPV with or without SB, and subsequent failures were treated with PPV. For contrast, a final model was treatment of laser prophylaxis (also assumed to be done in an office without operating room or anesthesia fees) for a retinal break (assuming 95% success), with failures treated initially with SB, and subsequent failures treated with PPV to provide a sense of the cost of prophylactic therapy as well.

All phakic PPV patients were assumed to also require cataract surgery (phacoemulsification with intraocular lens implantation). The incidence of patients who were phakic was assumed to be 70% for all groups, a frequency of previous RD treatment cohort studies.7,17

The current procedural terminology (CPT) codes used for the procedures were as follows: 67110 for PR, 67107 for SB, 67108 for PPV, 67112 for PPV in cases of re-operation, and 67145 for laser demarcation of retinal breaks (Table 1). In addition to the costs of the RD repair procedure, the cost for associated cataract surgery (CE) (CPT code 66984), and one level 4 new patient visit (CPT code 99204) and three level 3 follow up visits (CPT code 99213) were added to the total cost to represent one year of continued treatment. In any instance, if the scenario called for PPV following a previous PPV (i.e. 67112), the −78 modifier was applied so that only 70% of the total reimbursement fee was applied for that procedure. If the PPV followed a SB, or if the SB followed PR or laser for a retinal break, the −58 modifier was used so the more complex procedure was calculated at 100% of the Medicare allowable. The reimbursement schedules for procedures are based on the CMS terminology for procedures done in hospital or in an ASC, but only CE, SB, and PPV were ever modeled to be performed in an operating suite setting. PR and laser prophylaxis of RD were modeled as performed in the clinic setting regardless of practice setting permutation. The setting of CE was considered to be the same as the setting of RD repair, thus the calculations for facility-based RD repair includes CE under hospital-based billing, and the calculations for non-facility-based RD repair includes CE in an ASC.

Table 1.

Medicare Allowable Costs for Retinal Detachment Repair and Associated Treatments

| Facility, Hospital Operating Room Surgery | Non-Facility, ASC Surgery | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Procedure | CPT Code | Professional | Non-technical | Anesthesia | Total | Professional | Nontechnical | Anesthesia | Total |

| PR | 67110 | $901 | $1,442 | – | $2,343 | $1,005 | $0 | – | $1,005 |

| SB | 67107 | $1,493 | $2,914 | $255 | $4,662 | $1,493 | $1,635 | $255 | $3,383 |

| PPV | 67108 | $1,892 | $2,914 | $255 | $5,061 | $1,892 | $1,635 | $255 | $3,782 |

| PPV +/− SB | 67112 | $1,563 | $2,914 | $255 | $4,732 | $1,563 | $1,635 | $255 | $3,453 |

| Laser prophylaxis of RD | 67145 | $583 | $411 | – | $994 | $615 | $0 | – | $615 |

| Cataract surgery | 66984 | $769 | $1,730 | $153 | $2,652 | $769 | $971 | $153 | $1,893 |

| Level 4 new patient visit | 99204 | $145 | $128 | – | $273 | $183 | $0 | – | $183 |

| Level 3 follow up visit | 99213 | $55 | $74 | – | $128 | $79 | $0 | – | $79 |

All amounts are in United States dollars. ASC = ambulatory surgery center, CPT = current procedural terminology, PR = pneumatic retinopexy, SB = scleral buckle, PPV = pars plana vitrectomy, RD = retinal detachment.

Anesthesia professional fees (when applicable) were calculated based on the sum of base units and time units, multiplied by the conversion factor 25.52.28 CPT code 00145, anesthesia for vitreoretinal surgery is weighed as 6 base units. One time unit is 15 minutes and an estimated one hour was applied for vitreoretinal cases. Thus, the anesthesia professional fee for vitreoretinal cases was calculated as $255. In cataract surgery, CPT code 00142 is weighed as 4 base units, and the cases were estimated to use 2 time units, for a total of $153 in anesthesia professional fees.

We assumed that an untreated retinal detachment results in 20/400, but that a successful repair preserves 20/25 for a macular sparing RD and 20/80 for a macula off RD. We also assumed that 70% of RDs are macular involving and 30% are macular sparing. We purposely chose the highest number reported for macular involving rates, and also chose what are probably better natural history assumptions, so that, if anything, our model for all procedures errs on the side of being less cost-effective. Patients undergoing reoperations were assumed to retain 20/400, thus representing a failure to yield any better vision compared to natural history. Based on this calculation, a retinal detachment repair was calculated to save 5.9 lines of vision, likely an underestimate. Furthermore, we assumed that the visual acuity (VA) results were the same regardless of the technique.17 An average age of 62 years old was used based on previous literature.7 Years of life expectancy were derived from actuarial tables of the Social Security Administration.30 Quality-adjusted life year (QALY) data were adapted from previously published articles; a conversion of 0.03 QALYs per line-year of vision saved was applied.31

Calculations and analysis were performed using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Seattle, WA) software.

Results

The tabulated facility, professional fee, and anesthesia costs for each individual procedure are listed in Table 1. A summary of the adjusted results is presented in Table 2 for facility, hospital surgery and Table 3 for non-facility, ASC surgery.

Table 2.

Weighted Costs of Retinal Detachment Repair with Dollars per Line Saved, Dollars per Line-Year Saved and Dollars per QALY for Facility, Hospital Operating Room Surgery

| Initial Procedure | Weighted Cost | Weighted Cost with CE/IOL | With Clinic Visits | Lines Saved | Dollars per Line Saved | Mean Life Expectancy (Years) | Dollars per Line-Year Saved | Dollars per QALY |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR 60% | $4,500 | $5,243 | $5,901 | 5.9 | $1,000 | 20 | $50 | $1,667 |

| PR 75% | $3,691 | $4,155 | $4,814 | 5.9 | $816 | 20 | $41 | $1,360 |

| PR 90% | $2,882 | $3,068 | $3,726 | 5.9 | $632 | 20 | $32 | $1,053 |

| SB | $5,740 | $6,112 | $6,770 | 5.9 | $1,147 | 20 | $57 | $1,912 |

| PPV | $5,425 | $7,282 | $7,940 | 5.9 | $1,346 | 20 | $67 | $2,243 |

| Laser prophylaxis | $1,278 | $1,296 | $1,955 | 9 | $217 | 20 | $11 | $362 |

All amounts are in United States dollars. QALY = quality adjusted life years, CE/IOL = phacoemulsification of cataract with intraocular lens, PR = pneumatic retinopexy, 60% = primary procedure success rate of 60%, 75% = primary procedure success rate of 75%, 90% = primary procedure success rate of 90%, SB – scleral buckling, PPV = pars plana vitrectomy

Table 3.

Weighted Costs of Retinal Detachment Repair with Dollars per Line Saved, Dollars per Line-Year Saved and Dollars per QALY for Non-facility, ASC Surgery

| Initial Procedure | Weighted Cost | Weighted Cost with CE/IOL | With Clinic Visits | Lines Saved | Dollars per Line Saved | Mean Life Expectancy (Years) | Dollars per Line-Year Saved | Dollars per QALY |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR 60% | $2,615 | $3,145 | $3,565 | 5.9 | $604 | 20 | $30 | $1,007 |

| PR 75% | $2,011 | $2,343 | $2,763 | 5.9 | $468 | 20 | $23 | $780 |

| PR 90% | $1,408 | $1,540 | $1,961 | 5.9 | $322 | 20 | $17 | $554 |

| SB | $4,188 | $4,453 | $4,873 | 5.9 | $826 | 20 | $41 | $1,377 |

| PPV | $4,048 | $5,373 | $5,793 | 5.9 | $982 | 20 | $49 | $1,637 |

| Laser prophylaxis | $822 | $835 | $1,255 | 9 | $139 | 20 | $7 | $232 |

All amounts are in United States dollars. ASC = ambulatory surgical center, QALY = quality adjusted life years, CE/IOL = phacoemulsification of cataract with intraocular lens, PR = pneumatic retinopexy, 60% = primary procedure success rate of 60%, 90% = primary procedure success rate of 90%, SB – scleral buckling, PPV = pars plana vitrectomy

Primary Retinal Detachment Repair with Pneumatic Retinopexy

The groups with primary PR treatment were evaluated at 60%, 75%, and 90% success rates for initial procedure. These rates were chosen because previously reported studies have a wide range of success. Studies have reported a range from 60–65% primary success,3,8,16–18 75% primary success,15,19 and even higher rates, up to 90–95%.14

For a patient in a facility-based setting, when PR was assigned a 75% success rate, and subsequent surgery with PPV given a 90% success rate, the Markov analysis yielded a weighted cost of $3,691 (carrying it for the possibility of three procedures). Since 99% of patients would have successful RD repair after the three procedures, the model was never carried to a fourth intervention. If cataract surgery is factored in as described in the methods, the cost for these procedures was $4,155. When one level 4 new patient visit and three level 3 follow-up office visits were added to the cost, the total was $4,814. The dollars per line saved was $816, and the dollars per line-year saved was $41. The dollars per QALY saved calculation, as described above, was $1,360.

If a more favorable success rate for PR of 90% is assigned in the facility setting, as described for certain subgroups in the literature,14 then the weighted cost in the Markov analysis was $2,882 after three procedures, with a 99.9% reattachment rate. When cataract development was factored in, the cost was $3,068. With clinic visits factored into the calculation, the total was $3,726. The dollars per line of vision saved was $632, and the dollars per line-year saved was $32. The cost per QALY saved was calculated as $1,053. Similarly, if a 60% PR success rate is presumed, the model yields an imputed cost of $5,901, a cost/line of $1,000, a cost/line-year of $50, and a QALY cost of $1,667.

In a non-facility setting, if a 75% success for PR is assigned, then the Markov analysis with subsequent PPV for primary failures yielded a weighted cost of $2,011. When cataract surgery is factored into this cost, then the weighted cost was $2,343. Inclusion of a level 4 new patient visit and three level 3 follow-up visits generated a weighted cost of $2,763. The cost per line was $468. The dollars per line-year saved was $23 and the dollars per QALY saved was $780.

When a 60% or 90% success for PR was assigned in a non-facility setting, the weighted cost with subsequent PPV for primary failures was $2,615 / $1,408. Factoring in cataract surgery, the cost was $3,145 / $1,540. With included office visits, the cost was $3,565 / $1,961 and the cost per line was $604 / $322. The dollars per line-year was $30 / $17, and the dollars per QALY saved was $1,007 / $554.

Primary Retinal Detachment Repair with Scleral Buckling

The modeled cost of a patient in a facility setting initially undergoing SB surgery for RD in a hospital operating room with 80% primary success rate, and subsequent PPV for failures and another PPV for additional failures was $5,740 using the Markov analysis. The overall re-attachment rate was 99.8% after the three procedures. If the cataract rate as described in the methods was used, the cost was $6,112. Factoring in a level 4 new patient visit and three level 3 follow-up visits led to a cost of $6,770. The cost per line saved was $1,147 and the dollars per line-year saved was $57. When dollars per QALY saved were calculated, the total was $1,912.

This same evaluation in a non-facility setting, ASC surgery, with SB as the initial procedure and PPV for subsequent failures, yielded a weighted cost of $4,188 carrying out for three procedures. When cataract surgery is included in this weighted total, the cost was $4,453. The addition of clinic visits as described above generated a cost of $4,873. The cost per line was $826. Cost per line-year saved was $41 and the cost per QALY was $1,377.

Primary Retinal Detachment Repair with Vitrectomy

A primary PPV without scleral buckling was assumed in this model to have a 90% success rate. For facility cases performed in a hospital operating room, the Markov analysis demonstrated a modeled cost of $5,425 in this setting, with a PPV with or without SB as the second and third procedures for failed RD repair. When cataract development was factored in, the cost was $7,282. Including one level 4 new patient visit and three level 3 follow-up visits, the cost was $7,940. Cost per line was calculated to be $1,346 and the dollars per line-year saved were $67. Dollars per QALY saved were $2,243.

Primary PPV in the non-facility setting, operated in an ASC operating room, with the same success rate as described above, demonstrated a weighted cost of $4,048. Inclusion of cataract surgery yielded a cost of $5,373, and inclusion of clinical visits yielded a cost of $5,793. The cost per line was $982, the cost per line-year was $49 and the cost per QALY was $1,637.

Laser Prophylaxis for Symptomatic Retinal Breaks

Laser prophylaxis for a retinal break was assumed to have a 95% success rate in preventing retinal detachment as detailed in prior studies.23 For the patients that developed retinal detachment, scleral buckling was selected as the first procedure with an 80% success rate, and pars plana vitrectomy selected as a second procedure with a 90% success rate in this scenario. The modeled cost for facility patients after Markov analysis was $1,278. When cataract development for the vitrectomy patients was factored in, this cost was $1,296. Inclusion of one level 4 new patient and three level 3 follow-up visits led to a cost of $1,955. The number of lines saved in this scenario was considered to be 9 lines, as the group of patients with retinal breaks have better baseline vision than those with retinal detachment, and a higher rate of treatment success. Cost per line of vision was $217. The cost per line-year saved was $11 and the dollars per QALY saved was $362.

The same algorithm was applied for patients in a non-facility setting. The weighted cost was $822 for the laser and RD repair in failed laser cases. Inclusion of cataract surgery led to a cost of $835. The inclusion of one level 4 new patient and three level 3 follow-up visits totaled $1,255. The cost per line saved was $139, the cost per line-year saved was $7 and the cost per QALY was $232.

Discussion

The analysis presented demonstrates that when factoring in clinical visits and subsequent cataract surgery (which have not been included in other cost-consideration studies), the costs for repair of primary rhegmatogenous RD range from $2,763 to $7,940 depending on the treatment modality (PR, SBP, or PPV) practice and surgical setting. The PR cost could be even lower if a 90% success rate is modeled- a relatively high rate, but one that might be applicable in certain patient subsets.14 Correspondingly, the dollars per QALY saved ranged from $554 to $2,243. Although these ranges are moderately broad, these costs are much lower than for other therapeutic interventions within ophthalmology and other fields of medicine, and well under what has been offered as the acceptable cost of a QALY ($50,000 to $100,000).31 For contrast, the cost per QALY of treatment of H. pylori is roughly $1,830, and the cost per QALY in of treatment of systemic arterial hypertension with beta blockers is $7,389.31 The cost / QALY of the treatment of hyperlipidemia is $77,800, much higher than that of RD treatment.31 In comparison to other retinal treatments, a previous analysis the QALY value of these interventions compared favorably to pan retinal photocoagulation (PRP) for diabetic retinopathy ($700), and prophylaxis of retinal breaks was even more cost-effective ($232–$362).20 Recent analyses of costs associated with one year of pharmacologic therapy macular edema from RVO yielded a range of dollars per QALY saved from $824 for intravitreal bevacizumab to $25,566 for intravitreal ranibizumab.20–22

Several limitations are present in this report. A number of assumptions are made in the modeling the treatment of the patients including the average age, lens status, visual results, and fees for operating room anesthesia. The data presented are based on a Miami, Florida-based practice, and costs will vary depending on a given practice setting and type, or with different treatment algorithms. The conclusions were based on a “worst case scenario” regarding costs- highest setting, highest geographic area, and associated costs. Even with this intended bias, the cost-effectiveness was favorable. When the same costs were evaluated for lowest cost geographic areas, the cost parameters were reduced by 10% or less (Tables 4 and 5, available at http://aaojournal.org). While these figures do not apply directly in other countries where the reimbursement schedules are different and healthcare is distributed differently, the high level of cost-effectiveness of RD repair relative to other medical and ophthalmologic interventions is likely to be valid regardless of surgical approach or reimbursement region.

Our model further erred on the side of undervaluing RD repair by underestimating its VA value. Our assumptions that all re-operations were visual failures and led to no lines of saved vision and our assumption that the natural history or untreated or failed treatment was for 20/400 VA are almost certainly pessimistic and would lead to higher calculated cost values. Furthermore, we assumed a 70% macular involving rate, which is higher than the 50% range reported by some,17,19 and would result in a better value of lines saved and, hence, higher calculated cost values. If we incorporated some of these more favorable assumptions, the lines of vision saved might reasonably be doubled. Hence, the costs per lines of vision saved and QALY values halved, further distinguishing retinal reattachment treatments as extremely cost-effective. Moreover, rhegmatogenous RD may progress to a bilateral condition in 25–40% of patients,33 further amplifying the benefit of treatment and prevention.

While this study demonstrates PR to be less costly than surgery, not all cases can be equally managed, and in some hands the success rates are not as high as assumed. While others have reported lower costs for PR (albeit without including reoperations, clinical visit costs, or actualized cataract costs), this sort of comparison was not the primary purpose of the current study design.

This study demonstrates the unequivocally high level of cost-effectiveness of retinal detachment repair regardless of technique used. That the cost-effectiveness for the different methods of RD repair (PR, SB, PPV) are reasonably comparable frees the surgeon of significant financial constraint considerations, allowing them to tailor the repair method that they feel is most appropriate for a given patient’s pathology and situation. The results of this study suggest that repair of RD may be undervalued when compared to pharmacologic treatments for other chronic retinal illnesses, and even for surgical treatment for other subacute problems. Similar Markov analyses may facilitate evaluation of costs for other retinal diseases or pathologies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial Support:

The National Institute of Health Center grant P30-EY014801 and an unrestricted grant to the University of Miami from Research to Prevent Blindness, New York, New York.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Meeting presentation:

Submitted for consideration to American Academy of Ophthalmology, Annual Meeting, November 2013

Conflict of Interest:

JSC: none

WES: Consultant: Alimera

References

- 1.Wilkes SR, Beard CM, Kurland LT, et al. The incidence of retinal detachment in Rochester, Minnesota, 1970–1978. Am J Ophthalmol. 1982;94:670–3. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(82)90013-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hwang JC. Regional practice patterns for retinal detachment repair in the United States. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;153:1125–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Day S, Grossman DS, Mruthyunjaya P, et al. One-year outcomes after retinal detachment surgery among Medicare beneficiaries. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;150:338–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahmadieh H, Moradian S, Faghihi H, et al. Pseudophakic and Aphakic Retinal Detachment (PARD) Study Group Anatomic and visual outcomes of scleral buckling versus primary vitrectomy in pseudophakic and aphakic retinal detachment: six-month follow-up results of a single operation–report no. 1. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:1421–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arya AV, Emerson JW, Engelbert M, et al. Surgical management of pseudophakic retinal detachments: a meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1724–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brazitikos PD, Androudi S, Christen WG, Stangos NT. Primary pars plana vitrectomy versus scleral buckle surgery for the treatment of pseudophakic retinal detachment: a randomized clinical trial. Retina. 2005;25:957–64. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200512000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heimann H, Bartz-Schmidt KU, Bornfeld N, et al. Scleral Buckling versus Primary Vitrectomy in Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment Study Group Scleral buckling versus primary vitrectomy in rhegmatogenous retinal detachment: a prospective randomized multicenter clinical study. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:2142–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schaal S, Sherman MP, Barr CC, Kaplan HJ. Primary retinal detachment repair: comparison of 1-year outcomes of four surgical techniques. Retina. 2011;31:1500–4. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31820d3f55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmidt JC, Rodrigues EB, Hoerle S, et al. Primary vitrectomy in complicated rhegmatogenous retinal detachment–a survey of 205 eyes. Ophthalmologica. 2003;217:387–92. doi: 10.1159/000073067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun Q, Sun T, Xu Y, et al. Primary vitrectomy versus scleral buckling for the treatment of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Curr Eye Res. 2012;37:492–9. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2012.663854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weichel ED, Martidis A, Fineman MS, et al. Pars plana vitrectomy versus combined pars plana vitrectomy-scleral buckle for primary repair of pseudophakic retinal detachment. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:2033–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adelman RA, Parnes AJ, Ducournau D, European Vitreo-Retinal Society (EVRS) Retinal Detachment Study Group Strategy for the management of uncomplicated retinal detachments: the European Vitreo-Retinal Society Retinal Detachment Study report 1. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:1804–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.01.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwartz SG, Kuhl DP, McPherson AR, et al. Twenty-year follow-up for scleral buckling. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:325–9. doi: 10.1001/archopht.120.3.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tornambe PE. Pneumatic retinopexy: the evolution of case selection and surgical technique. A twelve-year study of 302 eyes. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1997;95:551–78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chan CK, Lin G, Nuthi AS, Salib DM. Pneumatic retinopexy for the repair of retinal detachments: a comprehensive review (1986–2007) Surv Ophthalmol. 2008;53:443–78. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis MJ, Mudvari SS, Shott S, Rezaei KA. Clinical characteristics affecting outcome of pneumatic retinopexy. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:163–6. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Han DP, Mohsin NC, Guse CE, et al. Southeastern Wisconsin Pneumatic Retinopexy Study Group Comparison of pneumatic retinopexy and scleral buckling in the management of primary rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998;126:658–68. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(98)00181-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fabian ID, Kinori M, Efrati M, et al. Pneumatic retinopexy for the repair of primary rhegmatogenous retinal detachment: a 10-year retrospective analysis. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131:166–71. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamaophthalmol.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldman DR, Shah CP, Heier JS. Expanded criteria for pneumatic retinopexy and potential cost savings. Ophthalmology. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.06.037. Available online 14 August 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smiddy WE. Relative cost of a line of vision in age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:847–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smiddy WE. Clinical applications of cost analysis of diabetic macular edema treatments. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:2558–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smiddy WE. Economic considerations of macular edema therapies. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:1827–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilkinson CP. Evidence-based analysis of prophylactic treatment of asymptomatic retinal breaks and lattice degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:12–5. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(99)00049-4. discussion 15–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Addendum B. Final OPPS Payment by HCPCS Code for CY 2013. 2013 Jan; Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/HospitalOutpatientPPS/Addendum-A-and-Addendum-B-Updates-Items/January-2013-addendum-B.html?DLPage=1&DLSort=2&DLSortDir=descending. Accessed March 1, 2013.

- 25.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Physician Fee Schedule. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/PhysicianFeeSched/index.html. Accessed October 21, 2013.

- 26.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Physician Fee Schedule–January 2013 revised release. Excel files: ANES2013.xls, GPCI2013.xls, PPRVU13_V1226_UP0 (within RVU13AR.zip). Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/PhysicianFeeSched/PFS-Relative-Value-Files-Items/RVU13AR.html. Accessed October 28, 2013.

- 27.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Ambulatory Surgical Center (ASC) Payment. Addenda Updates, July 2013 – ASC Approved HCPCS Code and Payment Rates. Excel file: July_2013_ASC_web_addenda_06.17.2013.xls (within: 2013-July-ASC-Addenda.zip). Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/ASCPayment/11_Addenda_Updates.html. Accessed September 5, 2013.

- 28.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual. Physicians/Nonphysician Practitioners. Rev 2714. 2013:121-9. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed September 14, 2013.

- 29.Sonnenberg FA, Beck JR. Markov models in medical decision making: a practical guide. Med Decis Making. 1993;13:322–38. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9301300409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Social Security. Actuarial Life Table. Period Life Table. 2009 Available at: http://ssa.gov/OACT/STATS/table4c6.html. Accessed May 29, 2013.

- 31.Brown MM, Brown GC, Sharma S, Landy J. Health care economic analyses and value-based medicine. Surv Ophthalmol. 2003;48:204–23. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(02)00457-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown MM, Brown GC, Lieske HB, Lieske PA. Preference-based comparative effectiveness and cost-effectiveness: a review and relevance of value-based medicine for vitreoretinal interventions. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2012;23:163–74. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e3283523fc1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilkinson CP, Rice TA. Michels Retinal Detachment. 2. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1997. pp. 1081–133. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.