Abstract

Bacterial biofilms grow on many types of surfaces, including flat surfaces such as glass and metal and irregular surfaces such as rocks, biological tissues and polymers. While laser scanning confocal microscopy can provide high-resolution images of biofilms grown on any surface, quantification of biofilm-associated bacteria is currently limited to bacteria grown on flat surfaces. This can limit researchers studying irregular surfaces to qualitative analysis or quantification of only the total bacteria in an image. In this work, we introduce a new algorithm called modified connected volume filtration (MCVF) to quantify bacteria grown on top of an irregular surface that is fluorescently labeled or reflective. Using the MCVF algorithm, two new quantification parameters are introduced. The modified substratum coverage parameter enables quantification of the connected-biofilm bacteria on top of the surface and on the imaging substratum. The utility of MCVF and the modified substratum coverage parameter were shown with Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus biofilms grown on human airway epithelial cells. A second parameter, the percent association, provides quantified data on the colocalization of the bacteria with a labeled component, including bacteria within a labeled tissue. The utility of quantifying the bacteria associated with the cell cytoplasm was demonstrated with Neisseria gonorrhoeae biofilms grown on cervical epithelial cells. This algorithm provides more flexibility and quantitative ability to researchers studying biofilms grown on a variety of irregular substrata.

Keywords: Biofilm, COMSTAT, Confocal Microscopy, Quantification, Surface, Tissue

1. Introduction

Bacterial biofilms are communities of bacteria that form when the bacteria adhere to a surface in an aqueous environment and begin to excrete a protective polysaccharide matrix that acts as a glue to hold the biofilm together (Lawrence et al., 1991). The basic requirements for biofilm growth are moisture, nutrients and a surface, enabling biofilms to grow and proliferate in a wide variety of environments. They can adhere to and grow on many types of surfaces, including glass, metals, polymers, sand and rocks, medical implants, and human or animal tissue (Fadeeva et al., 2011; Falsetta et al., 2009; Landry et al., 2006; Lawrence et al., 1991; Moreau-Marquis et al., 2010; Rodríguez and Bishop, 2007). The physical and chemical characteristics of the surface are partially responsible for the structure and behavior of the biofilms (Fadeeva et al., 2011; Landry et al., 2006). However, these surface characteristics, which are useful for understanding how biofilms grow and behave on real surfaces, can also affect the ability of researchers to characterize the biofilms.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) is an optical imaging technique used to obtain high-resolution images of biofilms at various depths within a sample and to generate 3-D reconstructions of the sample. It has been used extensively to enhance our understanding of biofilm structure and function (Lawrence et al., 1991; Neu and Lawrence, 1997; Palmer and Sternberg, 1999). Early research investigating the use of CLSM with biofilms was more commonly descriptive, using qualitative metrics to primarily analyze biofilm architecture (Neu, 2000). The development of new image processing and analysis algorithms specifically for biofilm samples has enhanced the quantitative output from CLSM images of biofilms (Heydorn et al. 2000; Mueller et al. 2006). All image processing software can quantify CLSM images to obtain the total amount of bacteria in an image. However, more sophisticated programs, including COMSTAT and PHLIP, have been developed specifically for biofilms to enable quantification of three-dimensional biofilm structures (Heydorn et al. 2000; Mueller et al. 2006). A particularly useful function called connected volume filtration removes biomass that is not connected to the substrate (Heydorn et al. 2000). This enables researchers to focus specifically on the bacteria that are part of the connected-biofilm and to eliminate unconnected bacteria, including dispersed bacteria, from analysis. It also provides key quantitative parameters, such as substratum coverage and biofilm volume (biomass). The primary limitations in using this function are that biofilm bacteria are assumed to grow in a connected fashion from a substratum and only from the first image layer. Therefore, any biofilm bacteria not connected to the first image layer will not be quantified, such as bacteria within the exopolysaccharide of the matrix, and thus this algorithm is limited in applicability to connected systems. For biofilms grown on an irregular surface, use of connected volume filtration would lead to underestimation of the substratum coverage and biomass since the biofilm bacteria would attach to the surface and mature on multiple image layers.

Therefore, this contribution introduces a modified connected volume filtration (MCVF) algorithm to enable analysis of bacteria grown on irregular surfaces that are visible via fluorescence or reflection confocal microscopy. Scripts were developed in MatLab to provide a tool to quantify bacteria populations and the irregular surface automatically. We also introduce two new quantification parameters that are obtained from this analysis. First, ‘modified substratum coverage’ enables quantification of all the connected-biofilm bacteria on the surface, whether they are on top of the irregular surface or on the surface on the imaging substratum. Second, the ‘percent association’ provides quantified data on the spatial location of bacteria colocalized with a fluorescently labeled component, including bacteria within a labeled tissue. These scripts facilitate the investigation of biofilm growth on irregular surfaces for bacterial attachment/removal, architecture, and viability when appropriately labeled.

2. Methods

2.1 Quantification of biofilm substratum

For biofilms grown on a flat surface, the substratum coverage (percent of the flat surface that is covered by bacteria) is typically calculated using the number of pixels on the first image slice that contain a bacterium (i.e. those that are fluorescently labeled):

| (1) |

where Bo is the number of bacteria pixels on the first image layer, pixelx is the number of pixels in the x-direction, and pixely is the number of pixels in the y-direction. However with an irregular surface, not all of the bacteria that are attached to the surface are on the first image slice.

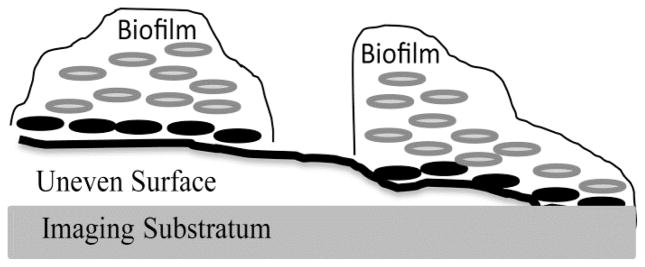

To account for attachment to an irregular surface, a modified connected volume filtration (MCVF) algorithm was developed, which requires the irregular surface be visible via fluorescence or reflection. The MCVF is used to find the modified substratum coverage, which is equated to the percent bacteria pixels on the first image slice that surround the irregular surface and bacteria pixels directly above a surface pixel (Figure 1). Like the available CVF algorithm, the bacteria on the first image slice represent bacteria adhered to the device imaging substratum (Figure 1 far right). Beyond this, our modified substratum coverage includes the bacteria above a fluorescent or reflective irregular surface. The algorithm assumes that bacteria and surface cannot occupy the same pixel location. Mathematically the modified substratum coverage is given by

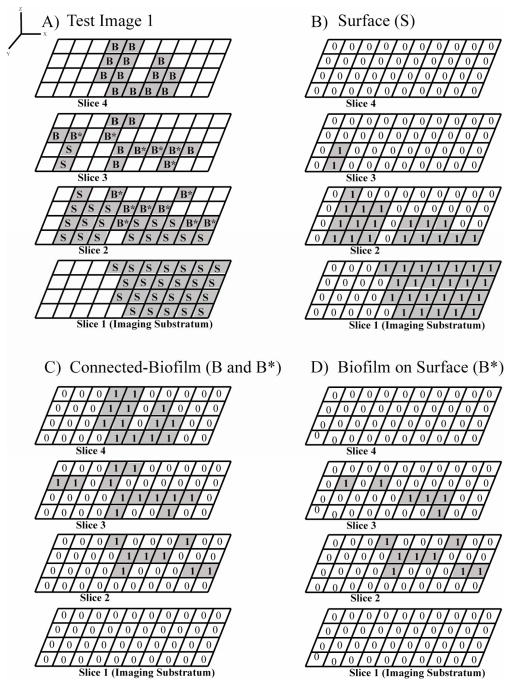

Figure 1.

Example of biofilm bacteria growing on top of an irregular surface that is above a flat imaging substratum. Biofilm at the far right grows on both the imaging substratum and the irregular surface. Conventional analysis of the biofilm with the connected volume filtration algorithm would quantify the biofilm grown upward from the imaging substratum, including the biofilm on the right in the figure and neglecting the biofilm on the left in the figure. Using our modified connected volume filtration algorithm all of the biofilm in the figure can be quantified, which starts quantification at the indexed bacteria locations where bacteria are located directly above the irregular surface or imaging substratum (black bacteria).

| (2) |

where Bo is the number of bacteria pixels on the first image layer, B* is the number of connected-biofilm bacteria pixels directly above a surface pixel, pixelx the number of pixels in the x-direction, and pixely is the number of pixels in the y-direction. Unlike the original substratum coverage algorithm, the modified substratum coverage considers the fluorescent/reflective surface and any imaging substratum surrounding the surface as the overall substratum of interest. Therefore bacteria above the irregular surface or the flat imaging substratum are considered in the quantification.

The colocalization of bacteria and the surface was quantified for percent bacteria associated with surface and volume of bacteria associated with surface.

| (3) |

| (4) |

where pixelz is the z-step size in μm.

2.2 Development of scripts

To analyze the connected-biofilm bacteria and surface components in a single pass, the Irregular Surface Scripts began with self-defined Bacteria and Surface images (source code for these scripts are available at http://www.fiegellab.org/source). The number of pixels in the image columns, number of pixels in the image rows, total number of pixels, micron per pixel calibration information, and the z-step size were written in the code. For the confocal images of biofilms and tissue, current COMSTAT source code (www.imageanalysis.dk) was used to read in the “.tif” image sequences of the confocal images and “.info” files to read in the calibration information. An automatic Otsu threshold in MatLab was used to segment the images into Bacteria and Surface binary sequences.

Once the image and calibration information were established, then the modified connected volume filtration (MCVF) was used to retain the connected-biofilm bacteria grown on an irregular surface in the variable ConnectedBiofilmBacteriaPixel. The original CVF algorithm assumes that any bacteria pixel on the first image slice or flat substratum is considered connected-biofilm bacteria (Heydorn et al., 2000). This assumption still holds true in our MCVF algorithm, which would account for bacteria growing around the irregular surface within the biofilm growth device. In addition, the MCVF algorithm assumes that any bacteria pixel in the same location directly above a surface pixel on a previous image slice is also considered a connected-biofilm bacteria pixel. The MCVF algorithm was used to identify bacteria growing on the flat substratum around the irregular surface and bacteria growing on top of an irregular surface. These bacteria pixels were stored in the variable BiofilmConnectedtoSurface. Then any bacteria pixels colocalized with the surface pixels (stored in variable BacteriaColocalized) were eliminated for the modified substratum coverage calculation since bacteria internalized within the surface were not included in this calculation. The variable BiofilmConnectedtoSurfaceforSubstratum represented the (Bo+B*) pixels and was used to quantify the modified substratum coverage (Equation 2).

The MCVF algorithm included an eight neighborhood connection on the variable BiofilmConnectedtoSurface to allow for horizontal biofilm growth. For each value of 1 in the variable BiofilmConnectedtoSurface, an eight neighborhood connection was completed for the specified pixel location in the Bacteria image. The eight neighborhood connection identified surrounding pixels in the eight locations around the pixel. If any of those pixel locations contained a value of 1, then a value of 1 was saved in the same pixel location for variable HorizontalGrowthForBacteriaAttachedtoBStart. To prevent double counting of the bacteria attached to the surface, a comparison of each pixel location in the variables BiofilmConnectedtoSurface and HorizontalGrowthForBacteriaAttachedtoBStart was completed. If a value of 1 was found in either group or in both groups for a single pixel location, then this pixel location was given the value of 1 in the variable BasisforSubstratum. Otherwise, a value of zero was given to the pixel location.

An index variable called StartIndex was created to determine which image slices had values of 1 present in the variable BiofilmConnectedtoSurface. Then CVF was completed for each image slice according to the variable StartIndex starting with the BasisforSubstratum image and comparing to the binary Bacteria image. This comparison included pixel-by-pixel comparison between image slices to allow for vertical biofilm growth and eight neighborhood connections to allow for horizontal biofilm growth. For any pixel location that contained a 1 in the variable BiofilmAttachedtoBiofilm, the value was kept in the variable Storage. To prevent over counting pixels, a comparison was done between the variables BiofilmConnectedtoSurface, BasisforSubstratum, and Storage. If a value of 1 was found in a pixel location for any of these three variables, then the output (variable filt_images) was given a value of 1 for the specific pixel location. The filt_images variable was used to quantify the connected-biofilm bacteria (variable ConnectedBiofilmBacteriaPixel) both associated with the surface and growing on top of the surface.

The bacteria pixels that were located in the same location as the surface pixels (variable BacteriaColocalized) were used to quantify the total number of pixels and the percentage of bacteria pixels that were associated with the surface (variables NumberofBacteriaandSurfaceSamePixel and PercentBacteriaAssociatedwithSurface respectively). This is a new quantification option for assessing bacteria internalized or associated with the edge of a surface using Equations 3 and 4.

The Surface binary image sequence was not subjected to CVF and was directly quantified. While the emphasis was on connected-biofilm bacteria and surface quantification of this code, the Irregular Surface Scripts also contain code to separate connected-biofilm bacteria and unconnected bacteria populations (Sommerfeld Ross, et al. 2012). For all quantified bacteria and surface pixels, the number of pixels and area were calculated for the overall image stack and for each slice in the stack. Calculated data were saved in an Excel file. Image “.tif” sequences were generated for visualization of ConnectedBiofilmBacteria, UnconnectedBacteria, OverallBacteria, Surface, BacteriaAssociatedWithSurface, and ModifiedSubstratumCoverageBacteria.

2.3 Pseudomonas aeruginosa grown on human bronchial epithelial cells and imaged via confocal microscopy

Human bronchial epithelial cells (16HBE14o-) were cultured on collagen-coated coverslips in a 24-well plate with a seeding density of 5×104 cells/well (Gruenert et al., 1988). Tissue was grown until confluent at 37°C and 5% CO2 (3 days). After three washings with 0.5 mL phosphate buffer, the cells were stained with 1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) for 20 minutes and washed three more times to eliminate excess stain prior to introducing bacteria. P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 containing the gfp plasmid pMRP9-1, originally provided by M. Parsek (Davies et al., 1998) and shared by T. Starner, University of Iowa, were grown in the 24-well plate at 37°C and 6% CO2 statically for 4 hours. The Zeiss LSM 710 confocal system (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) was used to acquire images.

2.4 Staphylococcus aureus grown on cultured human airway epithelial cells

Staphylococcus aureus biofilms were grown for 24 hours on cultured human airway epithelial cells (Calu-3). Polarized, antibiotic-free Calu-3 cells were prepared following the methods of Starner et al. and Karp et al. (Karp et al., 2002; Starner et al., 2006). Calu-3 cells were stained with CellTracker Orange (Molecular Probes). GFP–LAC/USA300 strain AH1726 was generated by transforming GFP-expressing plasmid pCM29 into LAC. Plasmid DNA was transformed into S. aureus by electroporation, as previously described (Chiu et al., 2013; Lauderdale et al., 2009). For plasmid maintenance in S. aureus, strains were grown in tryptic soy broth with chloramphenicol. GFP-expressing S. aureus were added at 108 CFU/mL in phosphate buffer to the apical surface of the cells and grown 24 hours. The Nikon Eclipse E600 microscope with Radiance 2010 image capturing (Biorad, Hercules, CA) was used to acquire images.

2.5 Neisseria gonorrhoeae bacteria grown on cervical tissue

Primary cervical cells were grown with Neisseria gonorrhoeae in continuous-flow chambers and imaged via confocal microscopy as previously reported by Falsetta et al. (Falsetta et al., 2009). Briefly, primary cervical cells were provided by the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, IA, from cervical biopsies and immortalized by the method of Klingelhutz et al. (Klingelhutz et al., 1994). Transformed cervical cells were cultured on collagen-coated coverslips until confluent at 37°C and 5% CO2 (2 days) and stained with Cell Tracker Orange (Life Technologies Corp.) prior to introducing bacteria. Coverslips with the labelled transformed cervical cells were moved to continuous-flow chambers, where they were inoculated with green-fluorescent Neisseria gonorrhoeae bacteria. After 1 hour static culture at 37°C, the combined cells continued to grow for 48 hours with a continuous flow of media at 180uL/min. A Nikon C1 confocal system (Nikon, Melville, NY) was used to acquire images.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1 Modified connected volume filtration (MCVF) and modified substratum coverage

To quantify biofilm bacteria grown on an irregular surface, Heydorn et al.’s connected volume filtration (CVF) algorithm (www.imageanalysis.dk, Heydorn et al., 2000) was modified to create the modified connected volume filtration (MCVF) algorithm. The original CVF algorithm requires that the first image slice to be analyzed be a flat surface. The CVF algorithm starts at the first image slice and connects pixels upward for vertical biofilm growth and completes an 8-neighborhood analysis to account for horizontal biofilm growth. In the MCVF algorithm, bacteria growing directly above a visible surface image pixel were indexed as the starting location. Thus, the surface does not need to be flat for biofilm analysis, but it does need to be visible through fluorescence (using a probe that emits at a different wavelength than the probe staining the bacteria) or reflection. From the indexed location starting point, the biofilm bacteria pixels are connected using an 8-neighborhood analysis as CVF does.

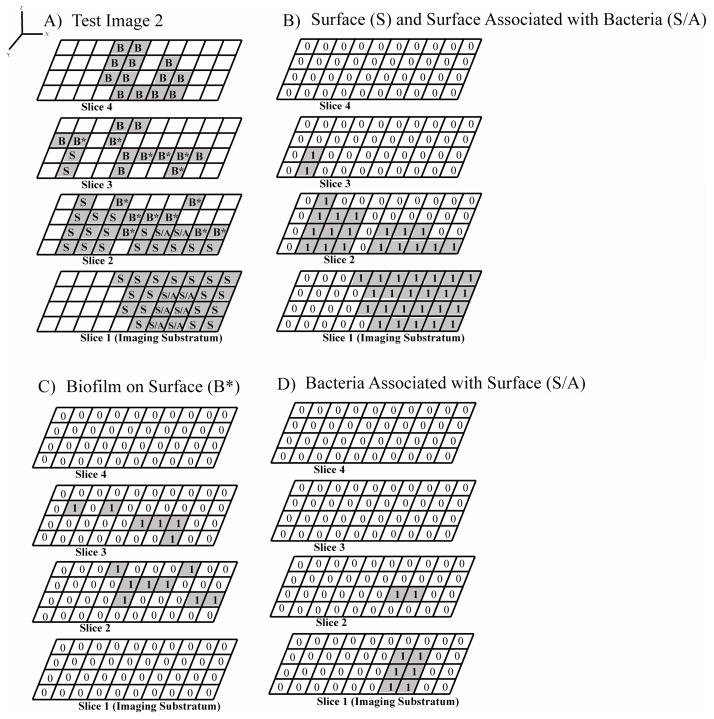

Figure 2 demonstrates how MCVF quantifies biofilm bacteria grown on top of an irregular surface. The test image in Figure 2A shows a surface (S) that is not uniformly spread throughout the image. The surface begins on image slice 1 and extends into slices 2 and 3. Connected-biofilm bacteria (B and B*) grow directly above a surface pixel and both outward and upward to the fourth image slice. In the original CVF algorithm, only pixels on the first image slice are considered surface. In the MCVF algorithm, any fluorescently-labeled surface (S) pixels (fluorescently-labeled or reflective), whether on the first image slice or on the last image slice, is considered the surface for quantification (Figure 2B). In the original CVF algorithm, the surface does not need to be fluorescently-labeled, as the surface is assumed to be the entire first image layer. Thus any bacteria on the first image layer is considered connected-biofilm bacteria Using MCVF, all 33 connected-biofilm bacteria pixels (B+B*) were identified (Figure 2C) by connecting bacteria starting with the biofilm on the surface (B*), which were found directly above surface (S) pixels (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Four-slice images containing bacteria and surface components. A) Test Image 1 of connected-biofilm bacteria (B* and B) grown on top of an irregular surface (S). The indexed bacteria that were used for the modified substratum calculation (Equation 2) are depicted as B*. B) Binary image sequence of the surface from Test Image 1. C) Binary image sequence of the connected-biofilm bacteria from Test Image 1. D) Binary image sequence of the indexed bacteria B*.

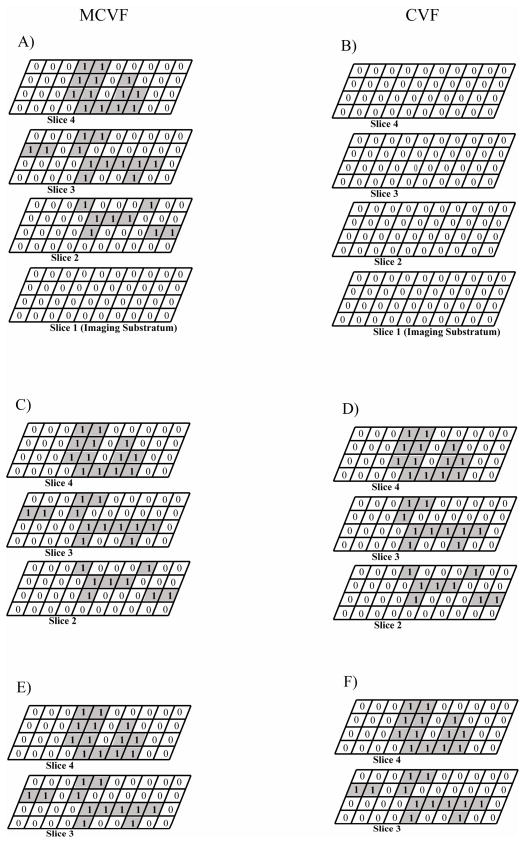

Table 1 compares MCVF and CVF when starting at image slice 1, slice 2, and slice 3 of Figure 2A. The MCVF uses the Bo and B* values to define the substratum slice instead of a single imaging substratum. When beginning at slice 1, the value of Bo was zero since no bacteria were present on the first slice and the value of B* was 14 from all the B* pixels on the image slices above. Upon connecting bacteria from Bo and B*, a total of 33 connected-biofilm bacteria pixels were quantified (Figure 3A). In comparison, when beginning at slice 1 and analyzing the images via CVF, the value of Bo was zero since no bacteria were present on the first slice. Therefore, using CVF results in no biofilm bacteria being quantified in the image (Figure 3B). If slice 1 were eliminated and analysis was started at slice 2, MCVF results in a total of 33 connected-biofilm bacteria pixels (Figure 3C), whereas CVF results in 31 total pixels (Figure 3D). The MCVF analysis resulted in the same number of connected-biofilm bacteria pixels obtained when analysis was started on the first image slice since no bacteria were present on this image. CVF analyzed only bacteria on the right side, thereby eliminating two bacteria pixels on the left in slice 3. Finally, if both slices 1 and 2 were eliminated and analysis was started at slice 3, the total number of connected-biofilm bacteria pixels was 25 using MCVF (Figure 3E) or CVF (Figure 3F). Therefore, MCVF and CVF only resulted in the same number of connected-biofilm bacteria pixels when the starting image slice contained all B* pixels, which equated to a flat surface.

Table 1.

Comparison of original connected volume filtration (CVF) and modified connected volume filtration (MCVF) for quantifying connected-biofilm bacteria. Analysis was started at image slice 1, image slice 2, or image slice 3 for comparison.

| Beginning at Slice Number: | Using CVF

|

Using MCVF

|

|---|---|---|

| Number of Connected-Biofilm Bacteria Pixels | Number of Connected-Biofilm Bacteria Pixels | |

| 1 | 0 | 33 |

| 2 | 31 | 33 |

| 3 | 25 | 25 |

Figure 3.

Comparison of modified connected volume filtration (MCVF) and original connected volume filtration (CVF) for quantifying connected-biofilm bacteria. A) Connected-biofilm bacteria identified using MCVF when starting at image slice 1. B) Connected-biofilm bacteria identified using CVF when starting at image slice 1. C) Connected-biofilm bacteria identified using MCVF when starting at image slice 2. D) Connected-biofilm bacteria identified using CVF when starting at image slice 2. E) Connected-biofilm bacteria identified using MCVF when starting at image slice 3. F) Connected-biofilm bacteria identified using CVF when starting at image slice 3.

MCVF can also be used to quantify a new parameter which we label as modified substratum coverage. This parameter was included since the original substratum coverage, defined as the percent coverage of bacteria on the first image slice, is a common quantification parameter used by researchers (Heydorn et al., 2000; Ren et al., 2005; www.imageanalysis.dk). The modified substratum coverage, which contains the bacteria on the first image slice (Bo) and the bacteria on the irregular surface (B*), was found to be 35.0% from 0 Bo pixels and 14 B* pixels present on the 4×10 image size (Figure 2D, Table 2). Using COMSTAT, the substratum coverage would be 0% since this parameter is quantified from the Bo only.

Table 2.

Test Image 1 quantification for surface, connected-biofilm bacteria, and modified substratum coverage. The number of pixels, area (μm2), and area (%) were enumerated for surface and connected-biofilm bacteria using a single pass through our scripts. The modified substratum coverage (Equation 2) represents the bacteria on top of the irregular surface.

| Surface | Connected-Biofilm Bacteria | Modified Substratum Coverage, % | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Pixels | Area, μm2 | Area, % | Number of Pixels | Area, μm2 | Area, % | ||

| Overall | 44 | 11.0 | 27.5 | 33 | 8.3 | 20.6 | 35.0 |

| Slice 1 | 24 | 6.0 | 60.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Slice 2 | 18 | 4.5 | 45.0 | 8 | 2.0 | 20.0 | |

| Slice 3 | 2 | 0.5 | 5.0 | 12 | 3.0 | 30.0 | |

| Slice 4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 13 | 3.3 | 32.5 | |

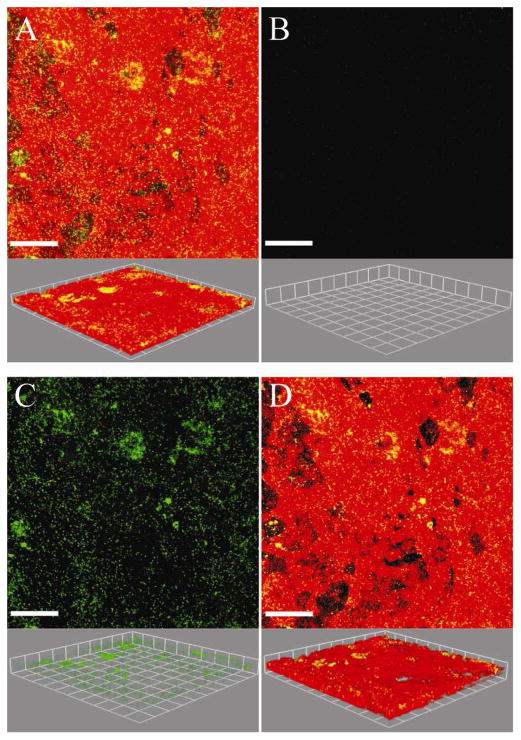

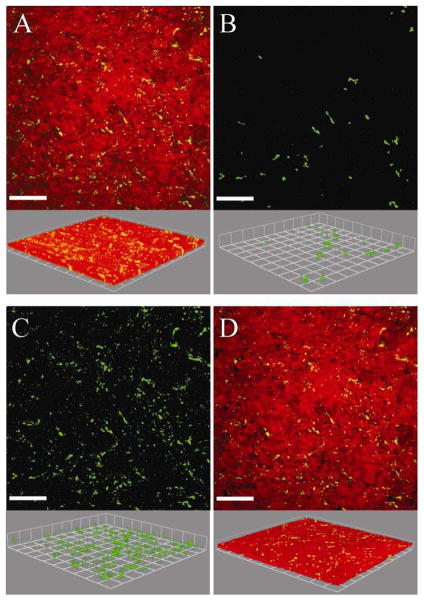

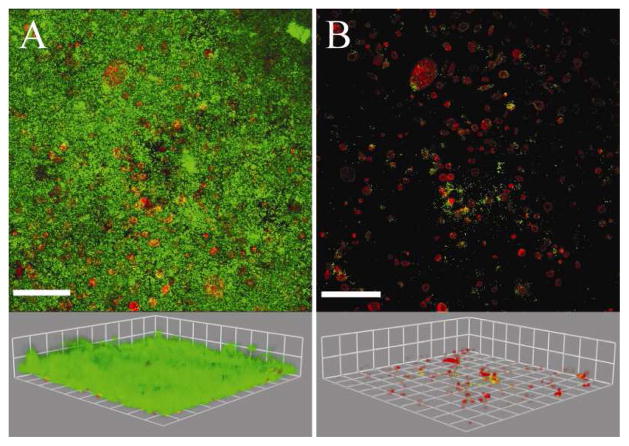

Being able to quantify biofilms grown on irregular surfaces could enhance the knowledge gained by researchers interested in biofilms grown on tissue, implants, natural environmental materials, and on medical or industrial equipment (Fadeeva et al., 2011; Landry et al., 2006; Lim et al. 2008; Moreau-Marquis et al., 2010). Biofilms grown on tissue were chosen to demonstrate the utility of the MCVF and modified substratum coverage (Savidge et al., 1995; Unger et al., 2005). Figure 4A is an original confocal image of green fluorescent Pseudomonas aeruginosa grown on red fluorescently-labeled human bronchial epithelial cells. It is important to note that with the modified CVF algorithm, the surface and the bacteria need to be contrastingly fluorescent to be separately identified. There were limited bacteria on the first image slice, such that using the original CVF algorithm would result in the substratum coverage of 0.2%. Since the original CVF depends on the first image slice, only 472 connected-biofilm bacteria pixels out of a possible 262,144 pixels were identified when applying CVF (Figure 4B). Since the first image slice contained very few bacteria pixels, the original CVF algorithm underestimates the biofilm bacteria present in the original image (Figure 4A). Using MCVF to index bacteria on top of the tissue, more connected-biofilm bacteria were identified and better match the original image (Figure 4C). A total of 190,403 connected-biofilm bacteria pixels were counted, indicating use of CVF did not quantify 99% of the connected-biofilm bacteria pixels. The modified substratum coverage was 6.5%. The modified substratum coverage can be used to assess the bacterial spread across the surface. A value of 100% would represent that bacteria were growing on the entire surface. The modified substratum coverage (Figure 4D) shows less bacteria than the original image since the substratum coverage does not include any free-swimming bacteria or bacteria that may be internalized within the tissue. Figure 5A shows the original confocal image of green fluorescent Staphylococcus aureus grown on red membrane-stained human airway epithelial cells. Processing the images via CVF resulted in 24,250 connected-biofilm pixels and a substratum coverage of 0.2% (Figure 5B). In comparison, the MCVF algorithm identified 126,081 total connected-biofilm bacteria pixels (Figure 5C). Therefore, CVF processing resulted in only 20% of the pixels being retained, mainly on the right of the image. Since MCVF quantifies the bacteria on the tissue surface, rather than just on the first image slice, MCVF processing resulted in a modified substratum coverage of 9.7%, significantly higher than the 0.2% obtained using CVF (Figure 5D). Overall, we have shown that the MCVF algorithm can be used to quantify both gram negative and gram positive biofilm bacteria grown on an uneven surface. While these example surfaces were tissue, the surface could be any fluorescently-labeled surface or reflective metal surface that contrasts with fluorescent bacteria.

Figure 4.

A) Original confocal image of green-fluorescent Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteria grown on red membrane-stained human bronchial epithelial cells (16HBEo-). B) Connected-biofilm bacteria quantified with connected volume filtration (CVF). C) Connected-biofilm bacteria quantified with modified connected volume filtration (MCVF). D) Modified substratum coverage of index bacteria on cells. Top: aerial view with scale bar of 80 μm. Bottom: side view with side of square equal to 42.7 μm. Threshold values were 149 for surface and 43 for bacteria.

Figure 5.

Confocal microscopy images of green-fluorescent Staphylococcus aureus biofilms grown on cultured human airway epithelial cells (Calu-3) stained with Cell Tracker Orange. A) Original confocal image. B) Connected-biofilm bacteria quantified with original connected volume filtration (CVF). C) Connected-biofilm bacteria quantified with modified connected volume filtration (MCVF). D) Connected-biofilm bacteria using MCVF recombined with epithelial cells. Top: aerial view with scale bar of 70 μm; bottom: side view with side of square equal to 38.2 μm; the threshold values were 77 for surface and 49 for bacteria.

3.2 Quantifying the spatial location of bacteria (percent association)

Researchers have observed colocalization of pixels for fluorescently labeled bacteria and fluorescently-labeled growth surface component pixels (Ledeboer and Jones, 2005). A surface can be a stained membrane or section of tissue, polymer, metallic device, or other reflective surface. In our algorithm, pixels that contain both the bacteria and surface pixels in the same location were classified as surface associated bacteria pixels. The test image in Figure 6A includes eight total surface associated bacteria pixels (S/A). On the first slice there were no connected-biofilm pixels and six S/A pixels, therefore 100% of the pixels were surface-associated (Figures 6C and 6D; Table 3). On the second slice there were two SA pixels and eight connected-biofilm bacteria pixels (B*), therefore 20% of the bacteria pixels were surface-associated and 80% of the bacteria pixels were connected-biofilm pixels. This provides researchers with the spatial location of the bacteria associated within the surface. This also provides relative amounts of surface associated bacteria and connected-biofilm bacteria by image depth, which could be particularly interesting for understanding biofilm growth, removal, or persistence either in the biofilm population or in the intra-surface population. In this example, more bacteria were associated at the lower image slice, indicating these bacteria were mobile into the lowest regions of the fluorescently-labeled surface. Overall there were 8 S/A pixels and 33 connected-biofilm bacteria pixels (B+B*), which meant 19.5% of the total bacteria were associated with the surface and 80.5% of the bacteria were connected-biofilm. Researchers could use this as a metric for understanding the prevalence of bacteria to grow as a biofilm on the surface or the preference of the bacteria to internalize into the surface. Furthermore, the volume of bacteria associated with the surface was also calculated. The first slice had 1.5 μm3 bacteria associated with surface, the second slice had 0.5 μm3 bacteria associated with surface, and a the total environment had 2.0 μm3 bacteria associated with surface. This new quantification parameter may be of interest to researchers investigating internalization of bacteria into the irregular surface, such as intracellular bacteria in tissue (Lim et al., 2008).

Figure 6.

Four-slice images containing bacteria and surface components with some overlap between bacteria and surface. A) Test Image 2 of connected-biofilm bacteria (B* and B) grown on top of an irregular surface (S) with some bacteria and surface colocalized (S/A). B) Binary image sequence of the surface from Test Image 2. C) Binary image sequence of the indexed bacteria on the surface B*, which is used to quantify the modified substratum coverage (Equation 2). D) Binary image sequence of the bacteria associated with the surface through colocalization.

Table 3.

Test Image 2 quantification for modified substratum coverage and the bacteria associated with the surface. The modified substratum coverage (Equation 2) represents the bacteria on top of the irregular surface, but does not include any bacteria colocalized with the surface. The number of pixels, volume (μm3), and percent of bacteria associated with the surface (%) were enumerated for the bacteria associated with the surface using a single pass through our scripts.

| Modified Substratum Coverage, % | Bacteria Associated with Surface | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Pixels | Volume, μm3 | Percent Bacteria Associated with Surface, % | ||

| Overall | 35.0 | 8 | 2.0 | 19.5 |

| Slice 1 | 6 | 1.5 | 100.0 | |

| Slice 2 | 2 | 0.5 | 20.0 | |

| Slice 3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Slice 4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

The utility of quantifying the percent bacteria associated is demonstrated with Neisseria gonorrhoeae biofilms grown on transformed cervical epithelial cells with the cytoplasm stained (Figure 7A). Table 4 shows quantified data for the overall 51-slice image sequence and for the first 5 image slices. The number, area (μm2), and percent area (%) of stained cytoplasm were quantified with MCVF. Of the Neisseria gonorrhoeae bacteria that were surface-associated, there were more surface-associated bacteria in the lower image slices, indicating these bacteria traveled into the cervical epithelial cells at the bottom of the cell layer. Further investigating this preference of the biofilm population or the intracellular population could provide insight into evasive survival mechanisms of these bacteria. Figure 7B includes the 0.6% of total bacteria that were associated with the cytoplasm, which is equivalent to 35,489.8 μm3 bacteria (Equations 3 and 4). Progressing from the first image slice, less bacteria were associated with the cytoplasm for each successive image slice. This new quantification parameter not only allows researchers to quantify colocalization of bacteria with a surface, but also allows identification of the spatial location of the interactions.

Figure 7. Neisseria gonorrhoeae.

bacteria grown on transformed cervical cells. A) Original confocal image with green-fluorescent bacteria on top of red-stained cervical cell cytoplasm. B) Bacteria associated with the cytoplasm via colocalization. Top: aerial view with scale bar of 120 μm. Bottom: side view with side of square equal to 61.7 μm. Threshold values were 38 for surface and 37 for bacteria.

Table 4.

Quantified data for Neisseria gonorrhoeae biofilms grown on transformed cervical cells. The entire image sequence contained 51 image slices. Data is shown for the overall image sequence and for each of the first five image slices. The number of pixels, area (μm2), and area (%) were enumerated for surface and connected-biofilm bacteria using a single pass through our scripts. The modified substratum coverage (Equation 2) represents the bacteria colocalized with the stained cervical cell cytoplasm. The number of pixels, volume (μm3), and percent of bacteria associated with the cytoplasm (%) were enumerated using a single pass through our scripts.

| Surface | Connected-Biofilm Bacteria | Bacteria Associated with Cytoplasm | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Pixels | Area, μm2 | Area, % | Number of Pixels | Area, μm2 | Area, % | Number of Pixels | Volume, μm3 | Percent Bacteria Associated with Cytoplasm, % | |

| Overall | 76837 | 118716.9 | 0.6 | 1804992 | 2788801.1 | 13.5 | 11485 | 35489.8 | 0.6 |

| Slice 1 | 17002 | 26268.9 | 6.5 | 107187 | 165609.2 | 40.9 | 2890 | 8930.4 | 2.7 |

| Slice 2 | 13184 | 20369.9 | 5.0 | 116785 | 180438.5 | 44.5 | 2255 | 6968.2 | 1.9 |

| Slice 3 | 10225 | 15798.1 | 3.9 | 121900 | 188341.5 | 46.5 | 1580 | 4882.4 | 1.3 |

| Slice 4 | 8178 | 12635.4 | 3.1 | 123441 | 190722.4 | 47.1 | 1169 | 3612.3 | 0.9 |

| Slice 5 | 6744 | 10419.8 | 2.6 | 121824 | 188224.0 | 46.5 | 966 | 2985.0 | 0.8 |

When using the MCVF algorithm it is important to consider the visibility of the surface. Connected-biofilm bacteria, modified substratum coverage, and percent bacteria associated with a surface will depend on the fluorescent stain or reflection of the surface. If only a portion of the surface is visible, then connected-biofilm bacteria may be underestimated. This is particularly a concern for fluorescent labels which may bleach over time. Therefore, the stability of a fluorescent label over the time course of experiment must be considered. For longer experiments the use of stable cells, such as green fluorescent protein or red fluorescent protein expressing cells, may be required to ensure the entire surface and bacterial population remain visible throughout the experiment.

4. Conclusions

In this work, the modified connected volume filtration algorithm was introduced that can be used to calculate novel parameters for bacteria grown on top of fluorescent or reflective irregular surfaces. The modified substratum coverage can be used to quantify the connected-biofilm bacteria on top of the surface and surrounding the surface on the imaging substratum. The utility of the MCVF algorithm and modified substratum coverage quantification parameter were demonstrated with Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus biofilms grown on top of human bronchial epithelial cells. The percent or volume of bacteria associated with a labeled component within the biofilm can provide quantified data on the colocalization of the two populations and can provide the spatial location of the interaction. The utility of the bacteria associated with surface parameters was demonstrated with Neisseria gonorrhoeae biofilms grown on transformed cervical cells.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Quantify connected-biofilm bacteria grown on visible irregular surfaces

Introduce modified connected volume filtration algorithm

Novel modified substratum coverage parameter assesses bacteria coverage on surface

Quantify percent bacteria associated with visible surface (fluorescent/reflective)

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grant Numbers AI096007 (JF) and AI078921 (AH) from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, a Pharmaceutics Research Starter Grant (JF) and Pharmaceutics Pre-Doctoral Fellowship (SSR) from the PhRMA Foundation, a University of Iowa Institute for Clinical and Translational Science Pilot Grant (NIH CTSA grant number UL1RR024979) (JF), and the Dr. J. Keith Guillory Fellowship (SSR).

We thank Dr. Arne Heydorn, Glostrup Hospital, Denmark, for the use of his connected volume filtration algorithm. The code was altered to create the modified connected volume filtration algorithm for quantifying fluorescently-labeled bacteria and surface. We thank Scott Hirsch, MathWorks, Natick, MA, for allowing the use of his xlswrite code, which was modified for our application to save quantified data to an Excel file. We thank Dr. Dieter C. Gruenert, University of California San Francisco, for the gift of the 16HBE14o- cell line and Dr. Timothy Starner, Department of Pediatrics, University of Iowa, for help in culturing Calu-3 cells for the Staphylococcus aureus studies and for providing GFP-labeled Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Footnotes

Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Chiu IM, Heesters BA, Ghasemlou N, Von Hehn CA, Zhao F, Tran J, Wainger B, Strominger A, Muralidharan S, Horswill AR, Bubeck Wardenburg J, Hwang SW, Carroll MC, Woolf CJ. Bacteria activate sensory neurons that modulate pain and inflammation. Nature. 2013;501(7465):52–57. doi: 10.1038/nature12479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies DG, Parsek MR, Pearson JP, Iglewski BH, Costerton JW, Greenberg EP. The involvement of cell-to-cell signals in the development of a bacterial biofilm. Science. 1998;280:295–298. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5361.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadeeva E, Truong VK, Stiesch M, Chichkov BN, Crawford RJ, Wang J, Ivanova EP. Bacterial retention on superhydrophobic titanium surfaces fabricated by femtosecond laser ablation. Langmuir. 2011;27:3012–3019. doi: 10.1021/la104607g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falsetta ML, Bair TB, Ku SC, vanden Hoven RN, Steichen CT, McEwan AG, Jennings MP, Apicella MA. Transcriptional profiling identifies the metabolic phenotype of gonococcal biofilms. Infection and Immunity. 2009;77:3522–3532. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00036-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenert DC, Basbaum CB, Welsh MJ, Li M, Finkbeiner WE, Nadel JA. Characterization of human tracheal epithelial cells transformed by an origin-defective simian virus 40. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science USA. 1988;85:5951–5955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.16.5951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall-Stoodley L, Nistico L, Sambanthamoorthy K, Dice B, Nguyen D, Mershon WJ, Jonshon C, Hu FZ, Stoodley P, Ehrlich GD, Post JG. Characterization of biofilm matrix, degradation by DNase treatment and evidence of capsule downregulation in Streptococcus pneumoniae clinical isolates. BMC Microbiology. 2008;8:173. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heydorn A, Nielsen AT, Hentzer M, Sternberg C, Givskov M, Ersbøll BK, Molin S. Quantification of biofilm structures by the novel computer program COMSTAT. Microbiology. 2000;146:2395–2407. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-10-2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbs AR. Confocal microscopy for biologists. Springer Science Business Media; New York, NY: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Karp PH, Moninger TO, Weber SP, Nesselhauf TS, Launspach JL, Zabner J, Welsh MJ. An in vitro model of differentiated human airway epithelia. Methods for establishing primary cultures. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2002;188:115–137. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-185-X:115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiedrowski MR, Paharik AE, Ackermann LW, Starner TD, Horswill AR. Staphylococcus aureus interactions with airway epithelia. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12543. submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klingelhutz AJ, Barber SA, Smith PP, Dyer K, McDougall JK. Restoration of telomeres in human papillomavirus-immortalized human anogenital epithelial cells. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1994;14:961–969. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.2.961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry RM, An D, Hupp JT, Singh PK, Parsek MR. Mucin-Pseudomonas aeruginosa interactions promote biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance. Molecular Microbiology. 2006;59:142–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauderdale KJ, Malone CL, Boles BR, Morcuende J, Horswill AR. Biofilm dispersal of community-associated methicillin-resistantStaphylococcus aureus on orthopedic implant material. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 2009;28(1):55–61. doi: 10.1002/jor.20943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence JR, Korber DR, Hoyle BD, Costerton JW, Caldwell DE. Optical sectioning of microbial biofilms. Journal of Bacteriology. 1991;173:6558–6567. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.20.6558-6567.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledeboer NA, Jones BD. Exopolysaccharide sugars contribute to biofilm formation by Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium on HEp-2 cells and chicken intestinal epithelium. Journal of Bacteriology. 2005;187:3214–3226. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.9.3214-3226.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim KHL, Jones CE, vanden Hoven RN, Edwards JL, Falsetta ML, Apicella MA, Jennings MP, McEwan AG. Metal binding specificity of the MntABC permease of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and its influence on bacterial growth and interaction with cervical epithelial cells. Infection and Immunity. 2008;76:3569–3576. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01725-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau-Marquis S, Redelman CV, Stanton BA, Anderson GG. Co-culture models of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms grown on live human airway cells. Journal of Visualized Experiments. 2010;44:2186. doi: 10.3791/2186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller LN, de Brouwer JFC, Almeida JS, Stal LJ, Xavier JB. Analysis of a marine phototrophic biofilm by confocal laser scanning microscopy using the new image quantification software PHLIP. BMC Ecology. 2006;6:1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6785-6-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neu TR. In situ cell and glycoconjugate distribution in river snow studied by confocal laser scanning microscopy. Aquatic Microbial Ecology. 2000;21:85–95. [Google Scholar]

- Neu TR, Lawrence JR. Development and structure of microbial biofilms in river water studied by confocal laser scanning microscopy. FEMS Microbilogy Ecology. 1997;24:11–25. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer RJ, Sternber C. Modern microscopy in biofilm research: confocal microscopy and other approaches. Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 1999;10:263–268. doi: 10.1016/S0958-1669(99)80046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren D, Zuo R, Barrios AFG, Bedzyk LA, Eldridge GR, Pasmore ME, Wood TK. Differential gene expression for investigation of Escherichia coli biofilm inhibition by plant extract ursolic acid. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2005;71:4022–4034. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.7.4022-4034.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez SJ, Bishop PL. Three-dimensional quantification of soil biofilms using image analysis. Environmental Engineering Science. 2007;24:96–103. [Google Scholar]

- Savidge TC, Walker-Smith JA, Phillips AD. Novel insights into human intestinal epithelial cell proliferation in health and disease using confocal microscopy. Gut. 1995;36:369–374. doi: 10.1136/gut.36.3.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommerfeld Ross S, Reinhardt JM, Fiegel J. Enhanced analysis of bacteria susceptibility in connected biofilms. Journal of Microbiological Methods. 2012;90:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2012.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starner TD, Zhang N, Kim G, Apicella MA, McCray PB., Jr Haemophilus influenzae forms biofilms on airway epithelia: implications in cystic fibrosis. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2006;174 (2):213–220. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200509-1459OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugahara KN, Teesalu T, Karmali PP, Kotamraju VR, Agemy L, Girard OM, Hanahan D, Mattrey RF, Ruoslahti E. Tissue-penetrating delivery of compounds and nanoparticles into tumors. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:510–520. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger RE, Huang Q, Peters K, Protzer D, Paul D, Kirkpatrick CJ. Growth of human cells on polyethersulfone (PES) hollow fiber membranes. Biomaterials. 2005;26:1877–1884. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.