Abstract

The authors build on prior research on the motherhood wage penalty to examine whether the career penalties faced by mothers change over the life course. They broaden the focus beyond wages to also consider labor force participation and occupational status and use data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Young Women to model the changing impact of motherhood as women age from their 20s to their 50s (n = 4,730). They found that motherhood is “costly” to women’s careers, but the effects on all 3 labor force outcomes attenuate at older ages. Children reduce women’s labor force participation, but this effect is strongest when women are younger, and is eliminated by the 40s and 50s. Mothers also seem able to regain ground in terms of occupational status. The wage penalty for having children varies by parity, persisting across the life course only for women who have 3 or more children.

Keywords: families and work, fixed effects, longitudinal, midlife, motherhood, women’s employment

A growing body of research has shown that mothers pay a significant wage penalty for having children (Avellar & Smock, 2003; Budig & England, 2001; Budig & Hodges, 2010;Waldfogel, 1995, 1997). The main argument is that having and raising children interferes with the accumulation of human capital and hence the level of productivity, which then translates into lower wages. Women who, as a result of having or planning to have children, either cut short their education, drop out of the labor force for an extended period, cut back to part-time employment, choose occupations that are more family friendly, devote less effort on the job, or pass up promotions because of time or locational constraints, end up achieving less than childless women who stay on track with full-time employment and take advantage of opportunities for training and career advancement (Aisenbrey, Evertsson, & Grunow, 2009; Anderson, Binder, & Krause, 2003; Baum, 2002; Gangl & Ziefle, 2009; Jacobsen & Levin, 1995). Those who become mothers at younger ages and go on to have more children are more likely to make these kinds of accommodations in their work lives and therefore suffer greater career penalties than do women who wait longer and have fewer children (Blackburn, Bloom, & Neumark, 1993; Chandler, Kamo, & Werbel, 1994; Miller, 2011; Taniguchi, 1999). Some researchers also argue that mothers may face workplace discrimination because some employers believe that mothers are less competent or committed to their jobs than childless women (Budig & England, 2001; Correll, Benard, & Paik, 2007). Because discrimination is so hard to measure empirically, evidence of it is typically inferred from residual wage differences that remain after controlling for human capital and other relevant characteristics (see Correll et al., 2007, for a notable exception).

Most research on the motherhood penalty has focused on short-term wage penalties among women who are still raising relatively young children, typically when they are in their 20s and 30s. By focusing on the peak child-rearing ages, however, these studies do not consider the longer term effects on women’s career paths as mothers empty the nest and launch their children from the parental home. Do the careers of mothers eventually catch up to those of childless women, or do mothers fall further and further behind as they age? It seems unrealistic to assume that the burdens of motherhood remain fixed over time, but it is unclear from prior research whether career penalties ease or accumulate over the life course. This question is important, because persistent penalties, especially in terms of job tenure and earnings, may accumulate over time to leave mothers with less access to pensions or retirement income in later life.

In this study, we use data from the National Longitudinal Study of Young Women (NLS-YW; see http://www.bls.gov/nls/nlsorig.htm) to model the motherhood penalty over the course of women’s careers as they age through their 40s and into their early 50s—a time when virtually all women have finished bearing children and most have seen their children either leave the home or at least enter adolescence. Moreover, we expand the focus beyond wages to also consider motherhood penalties associated with labor force participation and occupational status; in this way, we provide a more comprehensive view of how career outcomes of mothers and childless women change over the life course.

Background

Studies have generally found average wage penalties ranging from 5% to 10% per child among women in their 20s and 30s (Anderson et al., 2003; Budig & England, 2001; Waldfogel, 1997). Much, but not all, of the motherhood wage penalty has been explained by differences in productivity as measured by human capital indicators such as education and accumulated work experience (Budig & England, 2001; Gangl & Ziefle, 2009). In much of the literature, the motherhood penalty has also come to define the (unexplained) lower wages of mothers compared with childless women, even after productivity related factors are controlled. The unexplained differences between mothers and nonmothers could still reflect unmeasured productivity differences among women if, for example, motherhood diverts one’s energy and commitment away from the job (Evertsson & Breen, 2008), but it could also be due to differential treatment or discrimination, as suggested in the work of Correll et al. (2007).

Studies have shown that the penalty mothers pay also may vary across income levels, with those at the bottom of the income distribution paying a larger penalty than those at the top (Budig & Hodges, 2010). Others have found that the penalties are greatest for highly skilled working mothers (Wilde, Batchelder, & Ellwood, 2010). No prior research has considered whether the penalty changes as women grow older and the demands of childrearing decline, however.

There are good reasons to believe that motherhood penalties may change over time. On the one hand, as women gain more experience balancing work and family, and as their children grow older and more independent, mothers may be able to refocus on their work lives and as a result eventually narrow the wage gap with childless women (Anderson et al., 2003). On the other hand, mothers may suffer a growing disadvantage over time if their lack of early investment in human capital and discontinuity in work experience keep them out of higher paying occupations and deny them opportunities for significant wage growth and occupational mobility later in life. In this case, one might expect a widening of the motherhood penalty as women age into midlife (Blackburn et al., 1993; Loughran & Zissimopoulos, 2008).

Several studies using cross-sectional data to simulate women’s lifetime earnings losses associated with motherhood have estimated a gradual narrowing with age, but still a persistent motherhood gap by the mid-40s (Davies, Joshi, & Peronaci, 2000; Sigle-Rushton & Waldfogel, 2007). Simulations presented by Sigle-Rushton and Waldfogel (2007) suggest that, in the United States, the annual motherhood earnings gap narrows from about $7,500 among women at age 27 to about $2,500 by age 45, with a complete closing of the gap between mothers with one or two children. These findings are quite suggestive but, as simulations for hypothetical individuals (i.e., women with average education and either zero, one, or two births), based on cross-sectional data with few controls for important factors such as work experience, they are not representative of the lived experiences of actual cohorts of women. In the present analysis, we use detailed longitudinal data for a large, representative cohort to compare women’s employment outcomes over much of their working lives. These data allow us to assess the extent to which the careers of mothers (of all parities) and childless women either converge or diverge over the life course.

Most studies of the motherhood penalty have used wages as the only measure of economic achievement—see Aisenbrey et al.’s (2009) study of occupational penalties for a notable exception. Although wages are certainly an important economic indicator, they are but one aspect of economic success, reflecting the extent to which local labor markets reward workers. When considering the long-term costs of motherhood to women’s careers, it is also important to consider the continuity of women’s employment over time as well as their occupational status. We recognize that employment differences by motherhood status are not “penalties” in the same way as wage or occupational differences, yet we include them in our investigation because they are a core component of women’s careers, and they have often been overlooked in previous studies of the motherhood penalty. Moreover, by focusing only on the experiences of working women, past studies have ignored the selectivity into employment and do not consider how motherhood may influence employment decisions, especially at older ages. Whereas past research has focused on breaks in employment around the time of childbirth (Desai & Waite, 1991; Joshi & Hinde, 1993; Joshi, Macran, & Dex, 1996; Klerman & Leibowitz, 1999), less is known about longer term patterns: How does mothers’ labor force attachment change as their children grow up and leave home? Do mothers remain less attached to the labor force than nonmothers at older ages, or do they eventually catch up to, or even surpass, nonmothers? Few studies have used longitudinal data to consider women’s employment patterns throughout the adult life course as their children grow up and leave the home.

From a life course perspective, labor force participation and continuity is of interest in its own right. Many mothers continue to take some time out of the labor force when their children are young, and studies have shown that there tends to be considerable labor force churning for mothers surrounding the first and second births (Joshi & Hinde, 1993; Joshi et al., 1996; Klerman & Liebowitz, 1999). Interruptions that are short and early in a woman’s career may not be all that costly over the long term because women are not out of the labor force long enough for skills to erode. In fact, some research has found that one way women combat the motherhood penalty is to drop out for a short period after the birth of a child and then go to work for a new employer. Estes and Glass (1996) showed that wages were higher for mothers who changed jobs than for those who did not. Staff and Mortimer (2012) found that how a mother used her time when she was not in the labor force was also important; years spent gaining additional education and training did not increase the penalty, whereas years when a mother was neither enrolled in school nor working for pay increased the wage gap between mothers and childless women. Finally, mothers may sometimes be able to minimize the effects of time out of the labor force by choosing occupations with lower levels of skill depreciation and fewer penalties for time out, thus reducing the effect on wages (Mincer & Ofek, 1982; Mincer & Polachek, 1974; Okamoto & England, 1999). Some occupational skills can continue to be honed in volunteer activities during time out of the labor force, increasing the continuity of labor force careers.

On one hand, the more children a woman has, the more difficult it may be to exit the labor force for only a short period, complete additional schooling, or spend large amounts of time on volunteer activities. On the other hand, more children create greater pressure for labor force reentry and a second income later in life as those children age into adolescence, graduate from high school, and attend college. An examination of differences in labor force trajectories across the life course for mothers with different numbers of children is thus likely to be informative.

Labor force continuity may potentially be even more important for occupational location than wages. Occupational status scores show how well an occupation is valued in society, at least in terms of prestige; they also reflect the training required (education) as well as the remuneration level (earnings) for people in that occupation in general, thereby providing a broader view of the incumbent’s relative success in the work world. One’s occupational achievement may capture something more enduring than wages, and high levels of occupational attainment may be more or less easily recaptured than wages after years of absence from the workforce or reduced hours in the workforce. How interesting one’s work is, whether one has supervisory authority over others, and how much autonomy and control one has over one’s work may accumulate over a career, making it difficult for mothers who take time out of the labor force or cut back on work hours to rear children to be as well positioned occupationally later in life as those who do not make these types of adjustments. Comparative work has shown that in countries, such as Sweden, where parental leaves are generous, occupational gender segregation was actually higher than in countries, such as the United States, where paid maternal leaves are relatively short and less widely available than in Sweden (Mandel & Semyonov, 2005, 2006). Other research has found a significant amount of occupational downgrading immediately after childbirth (Aisenbrey et al., 2009; Joshi & Hinde, 1993), but these studies were unable to determine whether, in the long run, women recovered from these short-term labor–supply accommodations.

Labor force trajectories, occupational attainment, and wages are influenced by a host of characteristics that vary across individuals and that are typically controlled in studies of the motherhood wage penalty. These include key aspects of human capital accumulation, such as early investments in educational attainment, years of work experience, whether work is part time or full time, and utilization of on-the-job training, all of which can affect further labor force attachment, occupational advancement, and wages. Some have argued that women develop strong preferences for work versus family early in life and that this affects later life choices and outcomes (Hakim, 2002; Shaw & Shapiro, 1987). Women who are more committed to having a career may devote greater effort on the job and make choices that open opportunities for advancement compared with women who are more home oriented. Although prior studies of the motherhood wage penalty have not incorporated direct measures of work–family preferences, recent work by García-Manglano (2012a) showed that preferences are an important mechanism linking human capital to labor force outcomes.

Finally, women are differentially positioned on other social statuses that can affect employment outcomes. Those who are married and have access to a husband’s sizable income may face different incentives for labor force participation and career advancement than do women who are unmarried or who have low-earning husbands. White women may have different opportunity structures than non-White women that can affect decisions about education and employment that in turn influence life course trajectories of occupational advancement and earnings attainment. Past research on the motherhood penalty has typically included most of these factors in estimating the effects of children on wages.

In summary, this article builds on prior research on the motherhood wage penalty by considering the long-term association between motherhood and careers across the adult life course, to determine whether the motherhood penalty grows larger or smaller as women age from young adulthood to their early 50s. Unlike previous studies, which have focused almost exclusively on wage penalties, we broaden the focus to consider three interrelated career outcomes: (a) labor force participation, (b) wages, and (c) occupational status measured throughout the 35 years of the NLS-YW panel. Our key focus throughout the analysis is on changes over the life course in the relationship between motherhood and women’s career outcomes; we pay particular attention to how much of the penalty is explained by human capital accumulated across respondents’ lives and how much remains unexplained. Our goal is to describe how labor force outcomes play out over a mother’s life time as women make choices about their family lives and thus self-select (either intentionally or inadvertently) into different career trajectories.

Method

Data and Measures

The data for the analysis come from the NLS-YW cohort. The original NLS-YW cohort is based on a national sample of 5,159 women who were ages 14 through 24 in 1968. These women were born between 1944 and 1954 and were the leading half of the Baby Boom generation. They are an especially interesting cohort because they came of age right at the time that women’s work and family roles were being redefined by the civil rights and women’s movements of the 1960s and early 1970s. The NLS-YW cohort was reinterviewed either every year, or every other year, until the final interview in 2003, when they were ages 49 through 59. The NLS-YW is well suited for the present analysis because it follows the cohort long past the intensive child-rearing stage of life and therefore permits the assessment of longer term outcomes than was possible in previous studies. It also includes detailed employment and family information collected repeatedly throughout the adult lives of the respondents. Although women in later cohorts may differ from the NLS-YW in terms of labor force attachment and fertility behavior, some research suggests that the motherhood penalties by the early 40s had not changed substantially between the NLS-YW and the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 (NLSY79) cohorts (Avellar & Smock, 2003; García-Manglano, 2012b). Of course, it is too soon to predict whether more recent cohorts will continue to follow the same patterns into their 50s as the NLS-YW cohort, but the current analysis provides a useful baseline against which to compare the experiences of future cohorts.

Our ultimate goal is to model cumulative change throughout the adult life course, and thus we define our initial sample quite broadly as women who participated in at least two interviews between the initial wave in 1968 and the final wave in 2003. Most respondents contributed far more than two waves of data: Ninety-one percent had at least five interviews, and 74% had at least 10 interviews. Because only half the sample at the last interview was older than age 54 (i.e., the cohort was ages 49–59 at the last interview), we set the upper limit of our period of observation as age 54, thereby allowing us to observe all women as they aged into their early 50s. By focusing on women’s experiences prior to age 55, we attempt to limit the potential bias due to early retirement that occurs increasingly by the late 50s. Sensitivity analyses (available on request) show that this age restriction does not change our results in a substantive way.

Following prior studies of the motherhood wage penalty (e.g., Budig & England, 2001), we use fixed-effects methods to estimate the impact of motherhood and parity (measured as the cumulative number of children reported at each interview, i.e., zero, one, two, three or more) on labor force participation, wages, and occupational status. Fixed-effects estimates show the average impact of motherhood on employment outcomes, across the woman’s career, controlling for the effects of fixed, unobservable (and observable) characteristics that may be influencing both fertility and employment outcomes and thereby producing spurious motherhood effects. Although prior studies have found significant average wage penalties for women in their 20s and 30s, few have studied the effects at older ages, and none has considered whether the penalties might change as women (and their children) grow older.

Using the NLS-YW data, we are able to examine the motherhood penalty as women age from their 20s to their 50s and, by testing for Age × Parity interactions, we assess the extent to which these penalties grow larger or smaller at older ages. We interpret the age interactions not as a reflection of the aging or maturation process for women but rather as a proxy for the declining burden of childrearing that accompanies the aging of a mother’s children. We tried several alternative specifications that attempted to directly tap the changing impact over time of both the timing and numbers of births as well as the ages of the youngest child, but we came to the same conclusions that we draw based on parity.

The fixed-effects model requires that our data be organized into person-year records, one for each year in which the woman was interviewed (with a minimum of two observations per woman), and then pooled across years and across women. Our overall analytic sample consists of 4,730 women who contributed two or more person years to one or more of our models. Sample sizes vary, depending on the outcome under consideration. We start by modeling labor force participation across all person-year records for all women, and then we model wages and occupational status for working women, based only on the person-year records in which women were employed. For the labor force participation analysis, 4,006 women contributed 60,376 person-years of observation. Because the fixed-effects model requires that women experience at least one change in the outcome variable across the years of observation, we dropped 724 women from our analytic sample because they were either employed every year or not employed in any year and therefore were never observed to change employment status. For the wage models, 4,351 women contributed 35,272 employed person-years of observation; for the occupational prestige analysis, 4,476 respondents contributed 39,569 employed person-years of observation.

Our dependent variables reflect three employment outcomes measured each year: (a) labor force participation, (b) hourly wages, and (c) occupational status. A woman was considered to be currently employed if she answered “working” to the question “What where you doing most of last week—working, going to school, or something else?” Hourly wages are obtained from women’s direct reports of their hourly rate of pay, consistent with previous research on the motherhood wage penalty (cf. Avellar & Smock, 2003; Budig & England, 2001; Budig & Hodges, 2010). All wages are expressed in 1990 dollars, and we use the natural log of wages in the regressions. We measured occupational status using the Hauser–Warren Socioeconomic Index, which incorporates 1990 census occupational codes and occupational prestige ratings as reported in the 1989 General Social Survey (Hauser & Warren, 1997). The scale is a composite measure created by regressing occupational prestige ratings onto occupational earnings and education and then using the results to generate socioeconomic scores for all of the 1990 detailed occupation categories. Values range from 0 to 80.5.

Key independent variables include the number of children ever born (or adopted), as reported at each interview. This time-varying measure was coded categorically, thereby allowing the comparison of childless women with those who have one, two, or three or more children. It should be noted that as women make the transition to motherhood at older ages, the composition of the comparison group of childless women changes with age, with many of the best educated women switching from being childless when they become mothers at older ages. This is a problem inherent to most longitudinal fixed-effects studies of the motherhood penalty that require time-varying measures of fertility. In preliminary analyses, without fixed effects, we experimented with alternative specifications, including using a fixed measure of completed (final) fertility instead of the time-varying measure of cumulative fertility, so that the (always) childless comparison group would be fixed over time. Perhaps because most mothers in the NLS-YW had their first birth by their early 30s, the choice of fixed versus time-varying measures of fertility made little difference to the results at older ages; in other words, the childless category in this cohort did not change much after the early 30s.

Measures of human capital include educational attainment, reflecting the highest level attained by a given year. Women were categorized as having completed less than high school, a high school degree, some college, or at least a 4-year college degree. We include measures of years of full-time work experience and part-time work experience and the square of each of these terms. Because part-time jobs are often lower paying and of lower status than full-time jobs, we also include (in the wage and occupational status models) an indicator for whether the respondent was currently employed part time at the time of the interview. Part-time status was defined as working less than 35 hours per week in the week prior to the interview. A final measure of human capital reflects on-the-job training received over time and was calculated as the cumulative number of weeks of job training completed as of each interview. A squared term for this indicator is also included in the multivariate models, consistent with prior research.

In addition to measures of fertility and human capital, we also include a series of time-varying demographic characteristics, but because the fixed-effects model requires that covariates change over time, we do not include any fixed characteristics, such as race or parents’ socioeconomic status. Our key life course indicator is current age (at each interview), coded continuously and then grouped into decade categories reflecting the 20s, 30s, 40s, and early 50s. We tried different age specifications, including age and age squared, and found similar results, but we chose to present the categorical age specification because it is easier to interpret than the quadratic specification, especially when interacted with other variables. In addition to age, we control for marital status at each interview, coded as married versus not currently married (including never- and previously married), and husband’s income (measured in thousands of 1990 dollars and coded as 0 for unmarried women). We include husband’s income to index the financial needs of the family in the absence of the mother’s earnings. Finally, we include a woman’s work–family orientation, using her responses to the question “What would you like to be doing when you are 35 years old?”, which was asked at each interview until the woman reached age 34. Possible responses include “working (at a different or the same job),” “married, keeping house, raising [a] family,” or “other/don’t know.” Specifically, we define work expectations cumulatively as falling on a continuum from 0 to 10, representing the cumulative percentage of interviews (divided by 10) in which a woman indicated that she expected to be doing something other than working at age 35. This measure of home-oriented work–family expectations is time varying up to age 34 (the last age when the women were asked the question) and then remains fixed, whereby those older than age 34 are assigned the final value for this variable.

Analytic Strategy

We first present summary characteristics for the NLS-YW cohort at ages 25, 35, 45, and 52. Throughout the multivariate analysis, we use the full longitudinal data collected up through age 54 from women who were interviewed at least twice between 1968 and 2003, including those who dropped out prior to the end of the study. We estimate fixed-effects models for a binary outcome for the labor force analysis and for continuous outcomes in the case of wages and occupational prestige. All models are run in three steps. First, parity and age, measured in age decades of the life course (i.e., 20s, 30s, 40s, and early 50s), are used to predict the outcome of interest, net of demographic controls and early life expectations about paid work at age 35. The second model adds human capital variables, thus allowing us to determine how much of the motherhood penalty can be explained by education and work experience. A third set of models includes interactions between parity and the maternal age dummies in order to test whether the impact of motherhood varies by age. All results are weighted to adjust for sample attrition, and standard errors have been corrected for the correlation between observations from the same individual.

Results

Table 1 presents means and distributions on the career outcomes and human capital variables for the NLS-YW cohort at around ages 25, 35, 45, and 52, separately by parity, thereby allowing a comparison of childless women with women who had one, two, or three or more children. (Distributions on all variables used in the analysis of each of the three outcomes are included in the Appendix) Childless women at age 25 were better educated, more likely to be employed, earned higher wages, and worked in occupations of higher prestige than women who became mothers early, in particular those who had more than one child before age 25. Whereas 76% of childless women at age 25 were in the labor force, only 28% of mothers with three children were working for pay. At age 25, those who already had three (or more) children had completed only 10.6 years of schooling, compared with an average of 13.8 years for those who were childless at age 25. The gap between childless women and mothers in labor force participation, occupational attainment and, to a lesser extent, wages, appeared to attenuate at older ages. By age 52, mothers at all parities were more likely than childless women to be employed, and they had narrowed the gap in wages and occupational status compared with younger ages. It is unclear from these data whether the narrowing gap reflects improvements over time in the position of mothers, or the changing composition of childless women occurring as late child-bearers joined the group of mothers, bringing with them their relatively higher levels of human capital, particularly educational attainment. Nevertheless, Table 1 shows that the average level of education of childless women did not decline at older ages and in fact continued to increase slightly with age.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Women at Selected Ages, by Current Parity: National Longitudinal Survey of Young Women, 1968–2003

| Variable– | All Women all ages |

Age 25 | Age 35 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Childless women |

1 child |

2 children |

3+ children |

Childless women |

1 child |

2 children |

3+ children |

||

| N still in study | 4,730 | 1,592 | 1,056 | 842 | 455 | 578 | 651 | 1,185 | 1,091 |

| % in each parity group (of N still in study) | 100 | 40.4 | 26.8 | 21.3 | 11.5 | 16.5 | 18.6 | 33.8 | 31.1 |

| Career outcomes | |||||||||

| Labor force participation (% employed) | 61.2 | 76.0 | 44.5 | 33.1 | 27.9 | 79.2 | 69.6 | 61.2 | 50.5 |

| Hourly wages (if employed) | 9.6 | 9.2 | 7.9 | 7.2 | 6.2 | 11.4 | 10.1 | 8.6 | 7.9 |

| Occupational prestige (HWSEI index, if employed) |

35.9 | 39.4 | 32.5 | 28.8 | 25.4 | 40.9 | 36.1 | 35.6 | 31.4 |

| Human capital accumulation | |||||||||

| Completed years of schooling | 13.3 | 13.8 | 12.5 | 11.7 | 10.6 | 14.4 | 13.5 | 13.2 | 12.4 |

| Years of full-time work experience (>35 hours/week) |

9.4 | 3.3 | 3.2 | 2.4 | 2.3 | 9.0 | 8.2 | 6.5 | 5.3 |

| Years of part-time work experience (<35 hours/week) |

2.9 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 2.7 | 2.4 |

| Age 45[KAS1] | Age 52 | ||||||||

| Childless women |

1 child |

2 children |

3+ children |

Childless women |

1 child |

2 children |

3+ children |

||

| N still in study | 446 | 543 | 1,080 | 1,107 | 469 | 556 | 1,099 | 1,114 | |

| % in each parity group (of N still in study) | 14.0 | 17.1 | 34.0 | 34.9 | 14.5 | 17.2 | 33.9 | 34.4 | |

| Career outcomes | |||||||||

| Labor force participation (% employed) | 74.7 | 75.0 | 72.7 | 67.6 | 62.4 | 64.0 | 66.9 | 63.1 | |

| Hourly wages (if employed) | 13.2 | 11.3 | 10.8 | 8.8 | 13.1 | 12.3 | 11.2 | 10.1 | |

| Occupational prestige (HWSEI index, if employed) |

42.7 | 38.2 | 38.6 | 34.1 | 41.7 | 38.4 | 39.4 | 35.8 | |

| Human capital accumulation | |||||||||

| Completed years of schooling | 14.5 | 13.8 | 13.6 | 12.8 | 14.7 | 13.8 | 13.7 | 12.9 | |

| Years of full-time work experience (>35 hours/week) |

15.2 | 14.5 | 11.7 | 9.9 | 18.6 | 18.2 | 15.2 | 13.2 | |

| Years of part-time work experience (<35 hours/week) | 4.1 | 4.0 | 4.7 | 4.4 | 4.9 | 4.8 | 5.9 | 5.6 | |

Note: Data are from women with valid interview(s) between the ages of 20 and 54 and no missing data on any of the covariates used in the multivariate analysis. Because interviews were carried out every 1 to 3 years, there are not data for all women at each exact age. In this table, we have selected for each woman the observation closest to the reference age for each decade (e.g., for the 20s: age 25, or age 24, or age 26, or age 23, or age 27) and then computed means across women by parity. HWSEI = Hauser–Warren Socioeconomic Index.

Appendix.

Person-Year Means and Proportions for Variables Used in the Analysis of Each Market Outcome, National Longitudinal Survey of Young Women, 1968–2003

| Variable | LFP | Wages | HWSEI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Person-years | 60,376 | 35,272 | 39,569 |

| Career outcomes | |||

| Labor force participation (% employed) | 61.2 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Hourly wages (if employed) | 9.5 | 9.6 | 9.6 |

| Occupational prestige (HWSEI index, if employed) | 36.1 | 35.7 | 35.9 |

| Current fertility | |||

| Children ever born (current) | 1.7 | 1.4 | 1.5 |

| Human capital | |||

| Completed years of schooling | 13.1 | 13.2 | 13.3 |

| Years of full-time work experience (>35 hours/week) | 7.6 | 9.2 | 9.4 |

| Years of part-time work experience (<35 hours/week) | 2.8 | 2.6 | 2.9 |

| Currently working part time | 24.4 | 15.8 | 17.1 |

| Years of job training | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| Sociodemographic controls | |||

| Marital status (% married) | 65.2 | 58.3 | 59.3 |

| Husband’s income (in thousands of 1990 dollars) | 25.7 | 24.8 | 24.7 |

| Work expectationsa (0:work − 10:home) | 4.2 | 3.9 | 3.9 |

Note: Data are from women with valid interview(s) between the ages of 20 and 54 and no missing data on any of the covariates used in the multivariate analysis. Sample sizes correspond to Tables 2, 3, and 4. LFP = labor force participation; HWSEI = Hauser–Warren Socioeconomic Index.

Work expectations are measured as a continuum from 0 to 10, representing the cumulative percentage of interviews (divided by 10) in which a woman indicated that she expects to be doing something other than working at age 35.

Multivariate Analysis

Estimates of labor force participation from fixed-effects models are shown in Table 2. The fixed-effects models are nested, with the first model including the number of children and the woman’s age (measured in decades), the second column adding human capital variables, and the third model adding Age × Parity interactions. All models include controls for a woman’s marital status, her husband’s income, and whether her expectations were to be at home versus work at age 35.

Table 2.

Fixed-Effects Logistic Coefficients Predicting Women’s Participation in Paid Work: National Longitudinal Survey of Young Women, 1968–2003

| Variable | Gross effect |

+ Human capital |

+ Decade interaction |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 4,006 | 4,006 | 4,006 |

| Person-year observations | 60,376 | 60,376 | 60,376 |

| Children ever born (CEB; ref.: childless) | |||

| One child | −1.521*** | −1.641*** | −1.837*** |

| Two children | −1.821*** | −1.869*** | −2.314*** |

| Three or more children | −1.895*** | −1.843*** | −2.419*** |

| Age decade (ref.: 20s)a | |||

| 30s | −0.152** | −0.127** | −0.799*** |

| 40s | −0.433*** | −0.278** | −1.941*** |

| 50s | −0.986*** | −0.482*** | −2.152*** |

| CEB–age decade interaction (ref.: 20s × childless) | |||

| 30s × 1 child | 0.813*** | ||

| 30s × 2 children | 0.922*** | ||

| 30s × 3 or more children | 0.762*** | ||

| 40s × 1 child | 1.559*** | ||

| 40s × 2 children | 1.940*** | ||

| 40s × 3 or more children | 1.937*** | ||

| 50s × 1 child | 1.387*** | ||

| 50s × 2 children | 1.829*** | ||

| 50s × 3 or more children | 1.901*** | ||

| Highest educational degree (ref.: <high school) | |||

| High school graduate | 0.014 | −0.071 | |

| Some college | 0.002 | −0.128 | |

| College grad and beyond | 1.285*** | 1.286*** | |

| Work status, cumulative experience, and training | |||

| Cumulative years of full-time work experience | 0.246*** | 0.244*** | |

| Years of full-time work experience squared | −0.007*** | −0.007*** | |

| Cumulative years of part-time work experience | 0.252*** | 0.239*** | |

| Years of part-time work experience squared | −0.006*** | −0.005*** | |

| Years in job training | 0.066 | 0.103* | |

| Years in job training squared | −0.016* | −0.019** | |

| Sociodemographic controls | |||

| Marital status at interview (married = 1, other = 0) | −0.330*** | −0.422*** | −0.350*** |

| Husband’s income (in thousands of 1990 dollars) | −0.007*** | −0.009*** | −0.009*** |

| Home-oriented expectations at 35 (% of interviews) | −0.080*** | −0.054*** | −0.060*** |

Note: Data are from women between the ages of 20 and 54 with at least two valid interviews. Results are weighted for attrition, and standard errors are corrected for correlation between observations from the same individual. All models include controls for calendar year. Switching the reference category for “decade” reveals comparable results.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

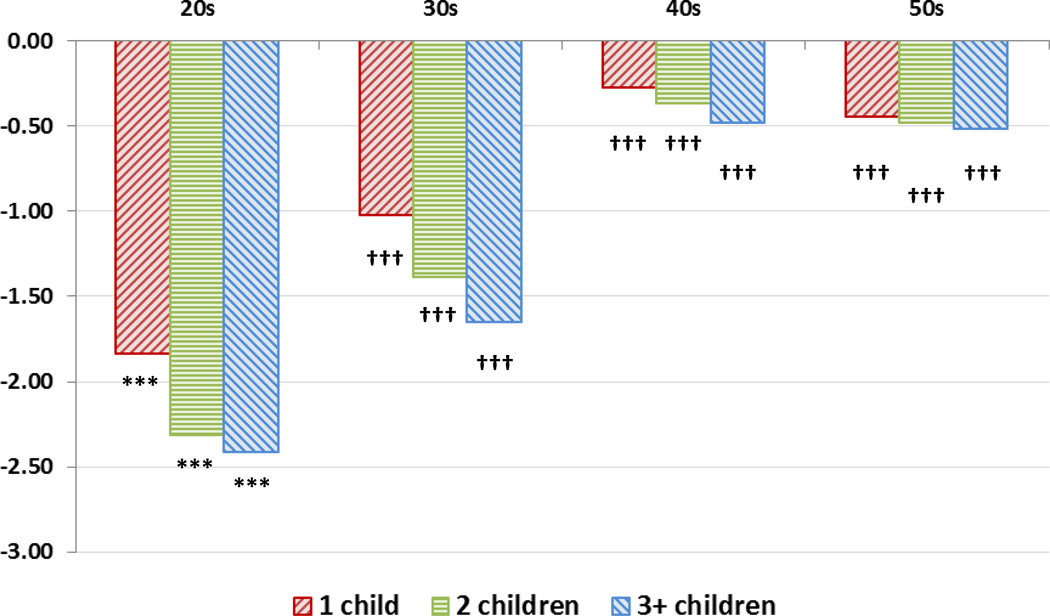

The first model in Table 2 shows that the number of children and age are both negatively associated with labor force participation. When human capital measures are added, the negative association of children remains largely unchanged, but the negative effect of age is diminished, particularly for women in their 50s. In all likelihood, this reflects the high correlation between age and accumulated work experience. In the final model, which adds interactions of parity with age, interactions are all positive and highly significant. Labor force rates tend to rebound later in the life course, counterbalancing some of the earlier negative effects of children and of aging. This pattern is clearly visible in Figure 1 which shows the net effects of motherhood (calculated as the sum of the main effect of parity plus the interaction of parity and age) for mothers relative to childless women for women in their 20s, 30s, 40s, and 50s. It is evident throughout the life course that higher parity is associated with lower employment rates, but the impact at all parities declines with age so that by the 40s, there is very little difference between mothers and childless women.

Figure 1.

Note: Net motherhood effects on employment are calculated from Table 2 as the sum of the coefficients for children ever born and the interaction between children ever born and age decade. Asterisks denote significant differences in the main effects (vs. childless women in their 20s), and daggers denote significant differences in the interactions (vs. women of the same parity in their 20s).

***/†††p < .001.

Results from fixed-effects models predicting the wages of employed women are presented in Table 3. As expected on the basis of prior studies, children are negatively associated with women’s wages, and controlling for human capital explains much, but not all, of the motherhood penalty (Budig & England, 2001). Whereas the first model suggests a very large gross motherhood penalty whereby having two or more children reduces the growth of wages by 12% to 17%, this effect drops to only 3% once we control for human capital differences. When we add Age × Parity interactions in the third model, the main effects attenuate and lose significance, suggesting that mothers in their 20s (the omitted age category) face a minimal wage penalty at any parity. The negative and significant interactions for mothers in their 30s with two or more children suggest a significantly larger penalty in the 30s than in the 20s. In both the 40s and early 50s, however, we see significantly larger penalties only for high-parity women with three or more children, compared with the effects for women in their 20s. The penalties for mothers over age 40 who have only one or two children are not significantly different than the small and nonsignificant penalties in the 20s.

Table 3.

Fixed-Effects Coefficients Predicting Women’s (ln) Hourly Wages: National Longitudinal Survey of Young Women, 1968–2003

| Predictor | Gross effect |

+ Human capital |

+ Decade interaction |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 4,351 | 4,351 | 4,351 |

| Person-year observations | 35,272 | 35,272 | 35,272 |

| Children ever born (CEB; ref.: childless) | |||

| One child | −0.052*** | −0.011 | −0.011 |

| Two children | −0.122*** | −0.031** | −0.020^ |

| Three or more children | −0.172*** | −0.033* | 0.011 |

| Age decade (ref.: 20s)a | |||

| 30s | 0.020* | 0.003 | 0.023* |

| 40s | −0.033* | −0.025^ | −0.004 |

| 50s | −0.106*** | −0.048* | −0.038 |

| CEB–age decade interaction (ref.: 20s × childless) | |||

| 30s × 1 child | −0.008 | ||

| 30s × 2 children | −0.039** | ||

| 30s × 3 or more children | −0.053** | ||

| 40s × 1 child | −0.018 | ||

| 40s × 2 children | −0.019 | ||

| 40s × 3 or more children | −0.068*** | ||

| 50s × 1 child | −0.017 | ||

| 50s × 2 children | −0.005 | ||

| 50s × 3 or more children | −0.051* | ||

| Highest educational degree (ref.: <high school) | |||

| High school graduate | 0.021 | 0.027^ | |

| Some college | 0.073*** | 0.079** | |

| College grad and beyond | 0.219*** | 0.222*** | |

| Work status, cumulative experience, and training | |||

| Cumulative years of full-time work experience | 0.052*** | 0.052*** | |

| Years of full-time work experience squared | −0.001*** | −0.001*** | |

| Cumulative years of part-time work experience | 0.023*** | 0.024*** | |

| Years of part-time work experience squared | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Currently employed part time | −0.039*** | −0.040*** | |

| Years in job training | 0.053*** | 0.052*** | |

| Years in job training squared | −0.004*** | −0.004*** | |

| Sociodemographic controls | |||

| Marital status at interview (married = 1, other = 0) | −0.023*** | −0.029*** | −0.030*** |

| Husband’s income (in thousands of 1990 dollars) | 0.001*** | 0.001*** | 0.001*** |

| Home-oriented expectations at 35 (% of interviews) | −0.006*** | −0.002 | −0.002 |

Note: Data are from working women between the ages of 20 and 54 with at least two valid interviews. Results are weighted for attrition, and standard errors are corrected for correlation between observations from the same individual. All models include controls for calendar year.

Switching the reference category for “decade” revealed comparable results.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

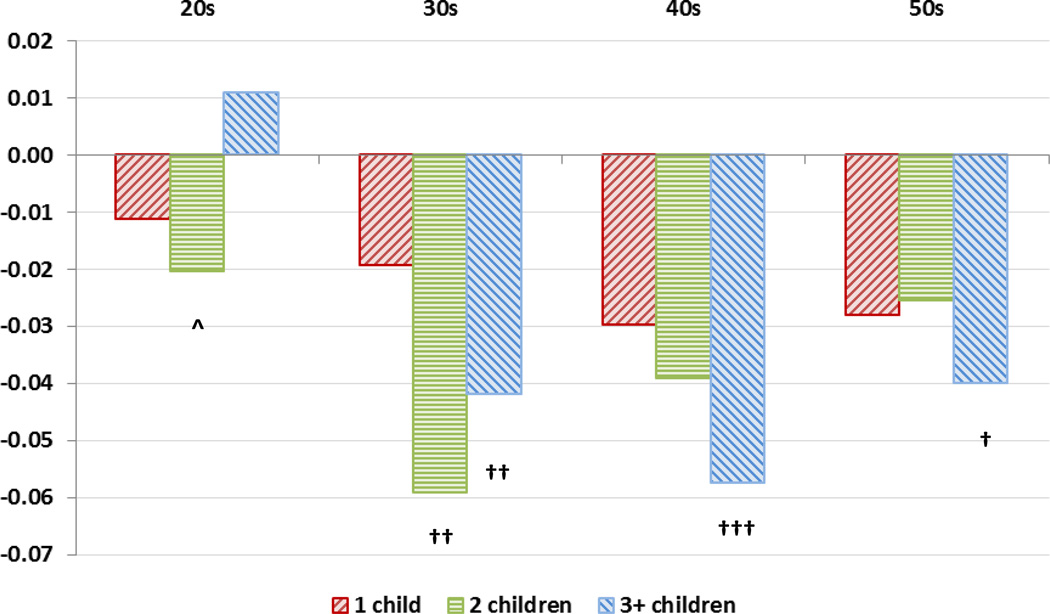

These patterns are evident in Figure 2 in which we have plotted the net effects of motherhood from these regressions: The wage penalties at parities above one child are significantly larger in the 30s than in the 20s, but by the 40s and 50s only the penalties for the highest parity mothers (with three or more children) remain statistically significant, and even they grow smaller by the 50s (4% penalty in the 50s vs. 6% in the 40s). In sum, these results suggest very different wage penalties according to parity: Whereas having one child never appears to significantly hurt mothers’ wages, the impact of having more children increases significantly by the 30s, but then continues past age 40 only for high-parity mothers with at least three children; by the time they reach their 40s, mothers with two children no longer suffer a significant wage penalty.

Figure 2.

Note: Net motherhood effects on hourly wages are calculated from Table 3 as the sum of the coefficients for children ever born and the interaction between children ever born and age decade. Asterisks and carats denote significant differences in the main effects (vs. childless women in their 20s), and daggers denote significant differences in the interactions (vs. women of the same parity in their 20s).

^p < .10. †/*p < .05. ††/**p < .01. †††/***p < .001.

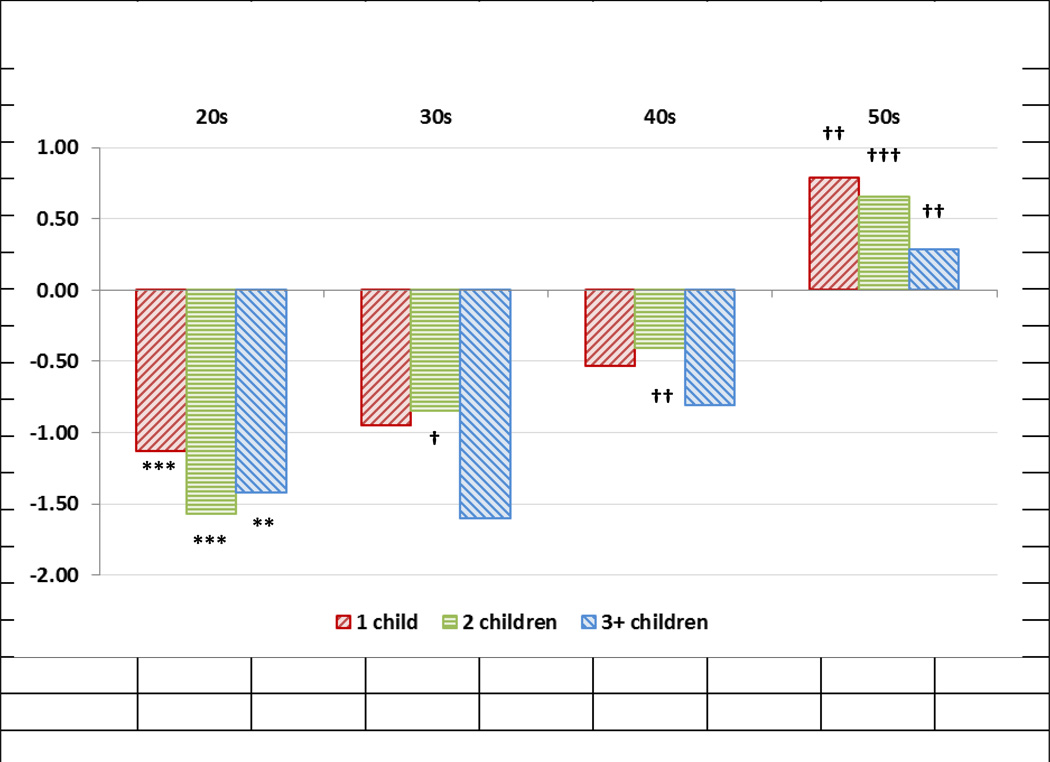

The results for occupational prestige in Table 4 appear to be more similar to the labor force participation results than the wage results. The first model in Table 4 shows that having children is negatively associated with occupational attainment and, net of parity, occupational attainment is lowest for women in their 50s (compared with women in their 20s). The effect of age is largely eliminated in models controlling for human capital, and the size of the negative effects of children are diminished, although they remain statistically significant in the second model. In the model with Age × Parity interactions, the interactions are positive and statistically significant for women with two children in their 30s and 40s and for all mothers in their 50s, suggesting that the occupational penalties for mothers decline significantly at older ages. This pattern is evident in Figure 3 in which are plotted the net effects of motherhood on occupational status. The negative effects of motherhood decline substantially between the 30s and 40s, and by the time employed mothers reach age 50, their occupational attainment is, if anything, higher than that for childless women, suggesting an occupational premium for older employed mothers. We return to this finding in the Discussion section. The trajectory of improvement in mothers’ occupational attainment over the life course (relative to childless women) is very consistent with the rebound in labor force participation seen in Table 2 and Figure 1 The occupation results are also consistent, though even more clear cut, than the relative improvement in wages for all but the highest parity mothers.

Table 4.

Fixed-Effects Coefficients Predicting Women’s Occupational Prestige (Hauser–Warren Socioeconomic Index) Scores: National Longitudinal Survey of Young Women, 1968–2003

| Predictor | Gross effect |

+ Human capital |

+ Decade interaction |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 4,476 | 4,476 | 4,476 |

| Person-year observations | 39,569 | 39,569 | 39,569 |

| Children ever born (ref.: childless) | |||

| One child | −1.561*** | −1.030*** | −1.134*** |

| Two children | −2.044*** | −0.998*** | −1.573*** |

| Three or more children | −2.875*** | −1.250*** | −1.424** |

| Age decade (ref.: 20s)a | |||

| 30s | 0.154 | 0.264 | 0.091 |

| 40s | −0.237 | 0.124 | −0.537 |

| 50s | −1.375** | −0.647 | −2.345*** |

| CEB–age decade interaction (ref.: 20s × childless) | |||

| 30s × 1 child | 0.180 | ||

| 30s × 2 children | 0.726* | ||

| 30s × 3 or more children | −0.179 | ||

| 40s × 1 child | 0.597 | ||

| 40s × 2 children | 1.167** | ||

| 40s × 3 or more children | 0.617 | ||

| 50s × 1 child | 1.917** | ||

| 50s × 2 children | 2.229*** | ||

| 50s × 3 or more children | 1.706** | ||

| Highest educational degree (ref.:<high school) | |||

| High school graduate | 1.579*** | 1.500*** | |

| Some college | 5.427*** | 5.302*** | |

| College grad and beyond | 10.300*** | 10.225*** | |

| Work status, cumulative experience, and training | |||

| Cumulative years of full-time work experience | 0.235*** | 0.226*** | |

| Years of full-time work experience squared | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Cumulative years of part-time work experience | 0.115^ | 0.102^ | |

| Years of part-time work experience squared | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| Currently employed part time | −1.533*** | −1.504*** | |

| Years in job training | 0.905*** | 0.932*** | |

| Years in job training squared | −0.048** | −0.050** | |

| Sociodemographic controls | |||

| Race (non-Hispanic White=1, other = 0) | |||

| Marital status at interview (married = 1, other = 0) | −0.028 | −0.003 | 0.038 |

| Husband’s income (in thousands of 1990 dollars) | 0.007* | 0.006^ | 0.006^ |

| Home-oriented expectations at 35 (% of interviews) | −0.240*** | −0.186*** | −0.190*** |

Note: Data are from working women between the ages of 20 and 54 with at least two valid interviews. Results are weighted for attrition, and standard errors corrected for correlation between observations from the same individual. All models include controls for calendar year.

Switching the reference category for “decade” reveals comparable results.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Figure 3.

Note: Net motherhood effects on occupational prestige (Hauser–Warren Socioeconomic Index [HWSEI]) are calculated from Table 4 as the sum of the coefficients for children ever born and the interaction between children ever born and age decade. Asterisks denote significant differences in the main effects (vs. childless women in their 20s), and daggers denote significant differences in the interactions (vs. women of the same parity in their 20s).

*/†p < .05. **/††p < .01. ***/†††p < .001.

Discussion

Building on prior studies of the motherhood wage penalty, we have looked at the long-term association between motherhood and multiple aspects of women’s careers in order to assess whether career penalties ease or accumulate over the life course. Do the careers of mothers eventually catch up to those of childless women, or do mothers fall further behind as they age? We used fixed-effects methods with panel data from the NLS-YW to model the changing impact of motherhood on women’s employment, wages, and occupational status as women age from their 20s to their early 50s.

Motherhood may have a long reach throughout women’s lives, but this analysis has shown that its impact on women’s careers attenuates over the life course. Children reduce labor force participation, but this effect is strongest when women are younger, in their 20s and 30s, when their children are younger too. Later in life, as children age, there may be counter pressures for mothers to increase their labor supply to meet the financial needs of older children. Our employment results showing the narrowing motherhood gap after the 30s gives us more confidence in interpreting our other results. Whereas prior research has generally ignored selection into the labor force and simply estimated wage penalties among working women, we specifically tested for a motherhood gap in employment. Our results confirm that once women are in their 40s, selection into the labor force should not be biasing our wage and occupational prestige estimates. And, in fact, in additional sensitivity analyses in which we assigned imputed wages (and occupational status scores) to nonworking women, we came to similar conclusions for the full sample as we present here for working women (results available on request). This provides further support that selection into employment does not alter our results.

The rewards of mothers’ careers, both in terms of wages and occupational status, also appear to regain ground as women age into their 40s and 50s, though with some differences by parity. Whereas mothers with three or more children continue to suffer significant wage penalties of at least 4% per child well into their 40s and 50s, lower parity mothers have generally narrowed the wage gap with childless women by their 40s. In fact, our results suggest that having only one child never significantly hurts a mother’s wages. The persistent wage penalty for older high-parity mothers is an important finding, because this is the period of the life course when mothers face both the financial needs of older children as well as their own need to save for retirement. Wage penalties make financing children’s needs and one’s own future income security more difficult. Yet it appears that, for the majority of mothers who have fewer than three children, their wages approach those of childless women by the time they reach their 40s. If the number of high-parity women continues to decline, this could signal a further reduction of the motherhood penalty in the future (Kirmeyer & Hamilton, 2011).

Our findings with regard to the wage penalty are consistent with past research, though they reveal the much greater complexity of patterns by both age and parity. Our results for younger women are consistent with findings of studies such as Budig and England (2001), who found a significant wage penalty (of about 3%–5%) for women in their 20s and 30s. Nevertheless, by focusing on differences across the life course, our analysis shows that the wage penalty is actually relatively low in the 20s and peaks in the 30s for women with two children and in the 40s for women with three or more children. Our wage results are also consistent with the simulated earnings gaps estimated by Sigle-Rushton and Waldfogel (2007), which showed a substantial narrowing of the earnings gap by age 45. But by simulating the patterns only for mothers with either one or two children, that study missed the persistent wage gap that we found for higher parity mothers. Our use of longitudinal data that reflect the accumulation of work and family experiences over the life course provides a much richer and more accurate assessment of the long-term consequences of motherhood for women’s careers than is possible using simulations based on cross-sectional data.

In terms of occupational status, the negative effects of motherhood decline substantially between the 30s and 40s at all parities, so that by the time employed mothers reach age 50 their occupational attainment is, if anything, higher than that for childless women. This apparent occupational “premium” for older mothers, net of human capital, is intriguing and worthy of further investigation. One possible explanation for this surprising finding is the changing selection into childlessness at older ages. Childless women in their 40s or 50s are an interesting combination of those who remained childless voluntarily (positively selected for having chosen a career or other pursuits instead of motherhood), and those who ended up childless against their own will (negatively selected either because of infertility, poor health, the inability to find a suitable partner, or family demands such as caring for aging or disabled relatives, all of which might also affect their market performance). As shown earlier, however, we did not find that childless women at older ages are less positively selected than younger childless women, at least in terms of their average level of education: Childless women in their 50s had the highest levels of education in our sample (see Table 1). To see whether the changing selectivity into childlessness was somehow distorting our results, we ran sensitivity analyses using a fixed measure of completed (final) fertility instead of the time-varying measure of cumulative fertility so that the childless comparison group was fixed over time; we found that the choice of a fixed versus time-varying measure of fertility made little difference to the results at older ages (results available on request).

As with any study, this one has several limitations. First, the NLS-YW is an older cohort, and much has changed in the work and family lives of subsequent cohorts, especially in terms of their higher educational attainment, delays in marriage and childbearing, and their lifetime attachment to the labor force. Some studies have shown that motherhood penalties are smaller for mothers who delay childbearing (Chandler et al., 1994; Miller, 2011), but we do not know whether these penalties persist over the long term. As noted earlier, several studies (e.g., Avellar & Smock, 2003; García-Manglano, 2012b) have compared the motherhood wage penalty for the NLS-YW and NLSY79 cohorts and found no change over time, at least for outcomes measured during the 20s and 30s. The NLSY79 cohort is now reaching their 50s, so it should soon be possible to replicate the current analysis for the more recent cohort.

A second limitation of the present study relates to the causal interpretation of our fixed-effects results. Although fixed-effects models take into account unobservable characteristics that remain fixed over time, only unchanging unobserved characteristics can be considered “controlled” in this type of specification. Attitudes and preferences about work and family may not remain fixed over the life course, especially as women have children, discover both the costs and benefits of mothering, and encounter the difficulties inherent in combining paid work with childrearing (Gerson, 1986; Hakim, 2002; Shaw & Shapiro, 1987). In this study, we attempted to control for changes in preferences with our time-varying indicator of what women expected to be doing at age 35, and we found that not only did preferences change over time, but they were also significant predictors of employment and occupational achievement, net of other factors. We recognize, however, that there may be other unobserved characteristics that affect outcomes, that change over time, and that are not captured in our fixed effects modeling approach.

Our findings highlight the multidimensional examination of later life outcomes that is needed to provide a full picture of any life course “motherhood penalty.” Not only wages, but also occupational standing and employment levels need to be considered to assess where women with different child-bearing trajectories end up. In further work, it would also be important to consider women’s accumulated assets and pension benefits and, related, their marital history, which also connects them to later life benefits and well-being. Finally, more attention should be paid to the selectivity of employment, especially at older ages. In past research that has evaluated the motherhood penalty among younger women in their 20s and 30s, all women were observed at ages when labor force attachment was strong for women and retirement was not yet an option. When considering later life stages and accumulated careers, the differential timing of retirement that is afforded those with strong attachment to “good jobs” with (early) retirement options becomes a more important part of the story. In future work, this also needs to be better conceptualized and explored so that the trajectories and economic outcomes of mothers with differing work and family careers can be adequately compared.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by a grant from the Russell Sage Foundation as well as by funds provided to the Maryland Population Research Center (Grant R24-HD041041) and the California Center for Population Research (Grant R24-HD041022) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Center for Child Health and Human Development. We gratefully acknowledge the helpful comments from Paula England, Michelle Budig, and Larry Kahn. An earlier version of this article was presented at the 2010 annual meeting of the Population Association of America, Dallas, TX.

References

- Aisenbrey S, Evertsson M, Grunow D. Is there a career penalty for mothers’ time out? Germany, Sweden and the US compared. Social Forces. 2009;88:573–605. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson DJ, Binder M, Krause K. The motherhood wage penalty revisited: Experience, heterogeneity, work effort, and work-schedule flexibility. Industrial and Labor Relations Review. 2003;56:273–294. [Google Scholar]

- Avellar S, Smock PJ. Has the price of motherhood declined over time? A cross-cohort comparison of the motherhood wage penalty. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2003;65:597–607. [Google Scholar]

- Baum CL. The effect of work interruptions on women’s wages. Labour. 2002;16:1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn ML, Bloom DE, Neumark D. Fertility timing, wages, and human capital. Journal of Population Economics. 1993;6:1–30. doi: 10.1007/BF00164336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budig MJ, England P. The wage penalty for motherhood. American Sociological Review. 2001;66:204–225. [Google Scholar]

- Budig MJ, Hodges MJ. Differences in disadvantage. American Sociological Review. 2010;75:705–728. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler TD, Kamo Y, Werbel JD. Do delays in marriage and childbirth affect earnings? Social Science Quarterly. 1994;75:838–853. [Google Scholar]

- Correll SJ, Benard S, Paik I. Getting a job: Is there a motherhood penalty? American Journal of Sociology. 2007;112:1297–1338. [Google Scholar]

- Davies H, Joshi H, Peronaci R. Forgone income and motherhood: What do recent British data tell us? Population Studies. 2000;54:293–305. doi: 10.1080/713779094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai S, Waite LJ. Women’s employment during pregnancy and after the first birth: Occupational characteristics and work commitment. American Sociological Review. 1991;56:551–566. [Google Scholar]

- Estes SB, Glass JL. Job changes following childbirth. Work and Occupations. 1996;23:405–436. [Google Scholar]

- Evertsson M, Breen R. The importance of work. changing work commitment following the transition to parenthood; Boston. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Sociological Association.2008. Aug, [Google Scholar]

- Gangl M, Ziefle A. Motherhood, labor force behavior, and women’s careers: An empirical assessment of the wage penalty for motherhood in Britain, Germany, and the United States. Demography. 2009;46:341–369. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Manglano J. The human capital argument revisited: Women’s work expectations, human capital accumulation and market outcomes at midlife; San Francisco. Poster presented at the annual meeting of the Population Association of America.2012a. May, [Google Scholar]

- García-Manglano J. A tale of two cohorts: The market consequences of low work expectations for early and late Baby Boomers in the United States; London, UK. Paper presented at the annual conference of the Centre for Longitudinal Studies.2012b. Nov, [Google Scholar]

- Gerson K. Hard choices: How women decide about work, career, and motherhood. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Hakim C. Lifestyle preferences as determinants of women’s differentiated labor market careers. Work and Occupations. 2002;29:428–459. [Google Scholar]

- Hauser RM, Warren JR. Socioeconomic indexes for occupations: A review, update, and critique. Sociological Methodology. 1997;27:177–298. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen JP, Levin LM. Effects of intermittent labor force attachment on women’s earnings. Monthly Labor Review. 1995;15:14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi H, Hinde PRA. Employment after childbearing in post-war Britain: Cohort study evidence on contrasts within and across generations. European Sociological Review. 1993;9:203–227. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.esr.a036678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi H, Macran S, Dex S. Employment after childbearing and women’s subsequent labour force participation: Evidence from the British 1958 birth cohort. Journal of Population Economics. 1996;9:325–348. doi: 10.1007/BF00176691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirmeyer SE, Hamilton BE. Childbearing differences among three generations of U.S. women. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2011. Data Brief No 68. [Google Scholar]

- Klerman JA, Leibowitz A. Job continuity among new mothers. Demography. 1999;36:145–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loughran D, Zissimopoulos JM. Why wait? The effect of marriage and childbearing on the wage growth of men and women. Journal of Human Resources. 2008;44:326–349. doi: 10.1353/jhr.2009.0032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandel H, Semyonov M. Family policies, wage structures, and gender gaps: Sources of earnings inequality in 20 countries. American Sociological Review. 2005;70:949–967. [Google Scholar]

- Mandel H, Semyonov M. A welfare state paradox: State interventions and women’s employment opportunities in 22 countries. American Journal of Sociology. 2006;111:1910–1949. [Google Scholar]

- Miller A. The effects of motherhood timing on career path. Journal of Population Economics. 2011;24:1071–1100. [Google Scholar]

- Mincer J, Ofek H. Interrupted work careers: Depreciation and restoration of human capital. Journal of Human Resources. 1982;17:3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Mincer J, Polachek S. Family investments in human capital: Earnings of women. In Marriage, family, human capital, and fertility. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 1974. pp. 76–110. [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto D, England P. Is there a supply side to occupational sex segregation? Sociological Perspectives. 1999;42:557–582. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw LB, Shapiro D. Women’s work plans: Contrasting expectations and actual work experience. Monthly Labor Review. 1987 Nov;110:7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Sigle-Rushton W, Waldfogel J. Motherhood and women’s earnings in Anglo-American, continental European and Nordic countries. Feminist Economics. 2007;13:55–91. [Google Scholar]

- Staff J, Mortimer JT. Explaining the motherhood penalty during the early occupational career. Demography. 2012;49:1–21. doi: 10.1007/s13524-011-0068-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi H. The timing of childbearing and women’s wages. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1999;6:1008–1019. [Google Scholar]

- Waldfogel J. The price of motherhood: Family status and women’s pay in a young British cohort. Oxford Economic Papers. 1995;47:584–610. [Google Scholar]

- Waldfogel J. The effect of children on women’s wages. American Sociological Review. 1997;62:209–217. [Google Scholar]

- Wilde ET, Batchelder L, Ellwood D. The mommy track divides: The impact of childbearing on wages of women of differing skill levels. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2010. Working Paper No. 16582. [Google Scholar]