Abstract

Risperidone is an antipsychotic drug approved for use in children, but little is known about the long-term effects of early-life risperidone treatment. In animals, prolonged risperidone administration during development increases forebrain dopamine receptor expression immediately upon the cessation of treatment. A series of experiments was performed to ascertain whether early-life risperidone administration altered locomotor activity, a behavior sensitive to dopamine receptor function, in adult rats. One additional behavior modulated by forebrain dopamine function, spatial reversal learning, was also measured during adulthood. In each study, Long-Evans rats received daily subcutaneous injections of vehicle or one of two doses of risperidone (1.0 and 3.0 mg/kg per day) from postnatal days 14 – 42. Weight gain during development was slightly yet significantly reduced in risperidone-treated rats. In the first two experiments, early-life risperidone administration was associated with increased locomotor activity at one week post-administration through approximately nine months of age, independent of changes in weight gain. In a separate experiment, it was found that the enhancing effect of early-life risperidone on locomotor activity occurred in males and female rats. A final experiment indicated that spatial reversal learning was unaffected in adult rats administered risperidone early in life. These results indicate that locomotor activity during adulthood is permanently modified by early-life risperidone treatment. The findings suggest that chronic antipsychotic drug use in pediatric populations (e.g., treatment for the symptoms of autism) could modify brain development and alter neural set-points for specific behaviors during adulthood.

Keywords: antipsychotic drug, locomotor activity, reversal learning, development, gender, dopamine

Antipsychotic drugs (APDs) are used to treat psychosis in adults, and have gained popularity as pharmacotherapy for childhood psychiatric disorders. The number of APD prescriptions for commercially insured children in the United States doubled between 1996 and 2005 (Curtis et al., 2005). In the United States, children under the age of 18 now account for nearly 20% of all APD users, and nearly 16% of all psychotropic medications given to children between the ages of 2 and 5 are APDs (Curtis et al., 2005; Domino & Swartz, 2008; Kuehn, 2009). More importantly, the average duration of APD treatment in pediatric patients has increased, with one study reporting a doubling in duration of use from 10 months to 19 months within a four-year period in Dutch children (Kalverdijk et al., 2008). Increased APD use and treatment duration in children is a likely due to regulatory approval of newer APDs as treatments for chronic psychiatric disorders, such as autism, disruptive behavioral disorder, and bipolar disorder in children (Kuehn 2009). Consequently, the number of children receiving newer, atypical APDs (e.g., risperidone, olanzapine, and aripiprazole) has grown 10-fold in the United States over recent years, with risperidone serving as the most widely prescribed APD in pediatric populations (Curtis et al., 2005), while the use of older APDs (e.g., haloperidol and chloropromazine) has remained stable (Patel et al., 2005). Despite the fact that nearly all reports on APD use in children (e.g., Fanton & Gleason, 2009) stipulate that it is crucial to determine the long-term effects of prolonged APD exposure during childhood, surprisingly few studies have addressed this issue.

Animal studies offer a useful means to obtain indirect, yet efficient answers regarding the long-term effects of early-life APD administration on brain development. Since children are more likely to receive risperidone than any other APD, research addressing its impact on brain development may especially informative. In this regard, Tarazi and colleagues (Choi, Gardner, & Tarazi, 2009; Choi, Moran-Gates, Gardner, & Tarazi, 2010; Moran-Gates, Grady, Shik Park, Baldessarini, & Tarazi 2007) have assessed the immediate biochemical effects of prolonged early-life risperidone administration in laboratory rats. Rats maintained on 1.0 or 3.0 mg/kg of risperidone from postnatal day 22 – 42 manifest increases in forebrain dopamine receptor density (Moran-Gates et al., 2007) at postnatal day 43 as well as changes in the densities of hippocampal serotonin (5HT1A) receptors and forebrain glutamate receptors (Choi et al., 2009; 2010). Administration of lower doses of risperidone for eight months to pig-tail macaques between the ages of 13 and 21 months reduces their ability to switch behavioral strategies over a four-week treatment cessation period (Mandell, Unis, & Sackett, 2011). These studies demonstrate that early-life risperidone administration can impact forebrain neurotransmission and related behaviors upon cessation of treatment, but do not address the possibility that longer-term or more persistent changes in brain and behavioral function emerge after such treatment.

The changes in receptor density reported in rats exposed to early-life risperidone (Choi et al., 2009; 2010; Moran-Gates et al., 2007) were in brain regions, such as the nucleus accumbens, caudate-putamen, and frontal cortex, which are associated with the monitoring of ongoing behavior. Locomotor activity serves as a relatively simple index of functioning in these brain regions since it is sensitive to changes in the biochemical and anatomical integrity of these areas (Bardgett, 2004). The main goal of this research was to assess locomotor activity in adult rats that had been administered risperidone during periods of development, specifically postnatal days 14 – 42, that have been considered analogous to early childhood through early adolescence in humans (Spear, 2000). The first study assessed locomotor activity for 7 – 12 days after the cessation of early-life risperidone administration in male rats. The second study determined if early-life risperidone administration produced an enduring effect on locomotor activity in male rats. The third study considered the impact of sex on activity levels after early-life risperidone administration, since females comprise 20% of the children treated with APDs (Domino & Swartz, 2008) and sex differences in responding to psychoactive drugs are well-documented (Evans, 2007; Evans & Foltin, 2010). Finally, since behavioral flexibility may be diminished by early-life treatment with risperidone (Mandell et al., 2010), reversal learning was measured, using a T-maze, intradimensional set-shift task, in young adult male rats after early-life risperidone treatment.

Method

Subjects

Experimental procedures were performed according to the Current Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (USPHS) under a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee at Northern Kentucky University. A total of 211 Long-Evans rats (56 females and 155 males) were used in these studies. These rats were derived from 24 litters that were shipped from Harlan Laboratories (Indianapolis, IN) and arrived in the Northern Kentucky University Department of Psychological Science animal facility on postnatal day seven. In the first two locomotor experiments and the reversal learning experiment, only male rats were studied, and litters were culled to 5 – 6 male pups on postnatal day eight. In the third locomotor experiment, male and female rats were used and litters were culled to 5 – 6 pups of each gender on postnatal day eight. On postnatal day 10, all pups were paw-tagged with subdermal injections of ink into the footpad for identification purposes. Moreover, at postnatal day 21, pups received single ear punches. Lighting in the housing room was maintained on a 12h on/off schedule with the lights on at 06:30. Drug treatments and testing were performed between 08:00 and 14:00.

Risperidone treatment

Careful consideration was given to selecting the doses of risperidone. A 1.0 mg/kg dose was chosen since it reportedly occupies 60–80% of D2 receptors (Kapur, VanderSpek, Brownlee, & Nobrega, 2003) in rat brain – the same degree of receptor blockade required for APD efficacy in humans - and reduces amphetamine-induced hyperactivity in rats by 50% (Arnt, 1995). However, a 1.0 mg/kg dose of risperidone in adult rats does not consistently produce drug blood levels that are near those reported in adult humans (Kapur et al., 2003). Therefore, a higher dose (3.0 mg/kg) of risperidone was also chosen for study, especially since some children are likely to receive doses at or above those recommended even for adults. Previous studies in rats (Choi et al., 2009; 2010; Moran-Gates et al., 2007) using these same two doses of risperidone have shown significant changes in forebrain receptor binding after early-life treatment. Using these doses in the present study allowed us to better compare our behavioral data to the biochemical changes reported in these earlier receptor-binding studies.

Beginning on postnatal day 14, subcutaneous injections of risperidone were performed daily until postnatal day 42. Within each study, three groups of roughly equal numbers of rats received injections of 1.0 mg/kg of risperidone, 3.0 mg/kg of risperidone, or the vehicle used for the risperidone solution as a control. Within each litter, there were 1 – 2 pups of the same sex that received the same treatment. Injections of risperidone were performed in a room just outside of the housing room. Prior to weaning, the pups were removed from the home cage and placed in a separate cage during injections. Each pup was weighed and received its injection - a process that took approximately one minute per pup. Immediately after received an injection, each pup was returned to its home cage. Litters were weaned at postnatal day 21, and the rats were group-housed three per cage such that each treatment group was represented within each cage. The National Institute of Mental Health’s Chemical Synthesis and Drug Supply program kindly provided the risperidone. Risperidone was dissolved in 10% glacial acetic acid. The resulting solution was brought to volume with saline, and the pH adjusted to ~6.2 with 6M NaOH. Solutions were injected at a volume of 2.0 ml/kg of body weight. In each locomotor experiment, body weight was recorded every third day during treatment.

Locomotor activity

In the first experiment, twenty-six male rats (n = 9 in the vehicle and 3.0 mg/kg risperidone groups; n = 8 in the 1.0 mg/kg risperidone group) were tested for locomotor activity for 20 minutes a day beginning at postnatal day 49 and continuing daily until postnatal day 53. Locomotor testing was performed in a dark testing room located 25 feet from the animal housing room. Each rat was placed into one of 12 clear polypropylene cages (51 cm long × 26.5 cm wide × 32 cm high) situated within a Kinder Scientific (Kinder Scientific, Poway, CA) Smart-Frame, photocell-based activity monitor. Rats were brought directly in their home cages from the housing room to the testing room on each test day and immediately placed in the test cages. Rats were tested in the same cage on each day. The number of photobeam breaks was tabulated over 20 minutes on each day of testing.

A second experiment determined if the locomotor effects of early-life risperidone treatment persisted well into adulthood. In this experiment, twenty-seven male rats (n = 9 per treatment group) received daily drug administration as described above from postnatal days 14 – 42. Locomotor activity was tested as described above beginning on postnatal day 49. Rats were tested once a week for seven weeks, and again at nine and twelve months of age (postnatal days 270 and 365). Rats were tested in the same cage on each day of testing over the first seven weeks – a clean cage was used at nine and 12 months of age.

A third experiment ascertained the effects of sex on the locomotor effects of early-life risperidone seen in young adult rats. In this experiment, sixty male (n = 20 per treatment group) and 56 female (n = 19 rats in the vehicle and 3.0 mg/kg dose group, n = 18 in the 1.0 mg/kg dose group) rats were treated as described earlier and tested for locomotor activity for 20 minutes on postnatal days 49 and 51. Rats were tested in the same cage each day – males were tested in cages kept separate from those used for testing females.

Reversal Learning

A fourth experiment assessed reversal learning during adulthood in rats administered early-life risperidone. An intra-dimensional shift (i.e., switch from one arm location to another) version of the task was performed. Forty-two male rats (n = 14 per treatment group) were treated as described above, and then trained and tested for reversal learning in a T-maze. Beginning on postnatal day 56, each rat was maintained on approximately 15 grams of rat chow per day. T-maze training commenced on postnatal day 63. The apparatus and habitation procedure were identical to those described in previous reports (e.g., Bardgett et al., 2010). The T-maze was constructed of wire-mesh and wood, with the wood painted black. The walls were 10 cm tall and arms were 9 cm wide. The start arm was 40 cm long, each goal arm was 45 cm long, and the entire maze had a wire mesh bottom. Beginning on postnatal day 63, all rats were placed on the T-maze until they ate two pieces of food (1/2 Honey-Nut Cheerio) or 90 seconds had elapsed. The food was located in cups that were 2 cm in diameter and 1.5 cm tall, and contained a wire mesh bottom in which inaccessible food could be placed beneath and accessible food could be placed above. The habituation procedure was repeated three times per day for five consecutive days. By the last day of habituation, all rats were eating the two pieces of food within 90 seconds.

Acquisition testing began on postnatal day 70. On the first day of acquisition testing, each goal arm of the T-maze was baited with food in food cups during the first three trials. Each rat was placed at the beginning of the start arm and removed from the maze as soon as they chose one of the goal arms and ate the food. The intertrial interval was approximately 90 seconds during these trials and all others. The arm that each rat chose the least over the first three trials became the baited or correct goal arm during the acquisition trials.

Beginning 90 seconds after the third trial on the first day of testing, each rat received seven additional trials in which only the non-preferred arm was baited. If the rat chose the correct arm, defined as placing all four paws into the goal arm, it was allowed to eat the food and then returned to its home cage. If it chose the incorrect arm, it was allowed to investigate the empty food cup and then returned to its home cage. Thereafter, rats received nine days of acquisition testing with ten trials a day. On each day of testing, the percentage of correct arm choices, defined as the number of correct arm choices divided by the number of trials × 100, and the time to choose an arm, defined as the time elapsed between the rat being set on the start arm of the maze and the rat placing four paws into a goal arm, were recorded. On the first day of acquisition testing, the percentage of correct arm choices was based on the last seven trials.

Reversal testing began on the tenth day of testing. Throughout this phase of testing, the location of the baited goal arm was reversed. Each rat received 10 trials a day for four more days.

Data analyses

The number of photobeam breaks accrued over each 20-minute testing session was compared between the treatment groups using a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with treatment group as a between-groups, independent factor and test day as a repeated measure, within-groups factor. In the third locomotor experiment, a three-way ANOVA was used to compare the effects of treatment and sex (between-groups, independent factors) and test day (repeated measure, within-groups factor) on activity over 20 minutes. Body weight data were compared as a function of treatment and postnatal age (and sex in the third study) using the same statistical methods. Pearson product-moment correlations were performed for each of the three locomotor experiments in order to assess the association between the amount of weight gain between postnatal days 14 – 41 and locomotor activity on postnatal day 49. In each experiment, correlations were conducted for animals within each treatment group and, in the case of the third locomotor experiment, within each sex. A two-way ANOVA was used for the acquisition and reversal phases of the reversal learning experiment, with drug treatment serving as a between-groups, independent factor, and test day serving as repeated measures, within-groups factor. Data for percent correct choices per day and time to choose each day were analyzed. Alpha levels were set at p < .05 for all analysis of variance tests. Post-hoc testing was performed using a Tukey/Kramer test with a significance level set at 5%.

Results

Weight gain

Body weight data from the three locomotor experiments were assessed to determine the effects of early-life risperidone administration on growth. In the first experiment, body weight was found to be slightly but significantly lower in the risperidone-treated rats as a function of age (Treatment × Age interaction: F(18, 207) = 1.7, p = .04)(Figure 1A). While this interaction was statistically significant, post-hoc comparisons of weights between the treatment groups on each day did not reveal a significant group difference on any of the days. By postnatal day 45, three days after treatment ceased and before locomotor testing was performed, the three treatment groups did not differ in body weight (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Comparison of body weight across development during early-life risperidone administration from postnatal day 14 – 42. A. and B. represent respective data from the first two experiments with male rats, and C. represents body weight data from the third experiment involving male and females rats. Symbols indicate where the males treated with 3.0 mg/kg of risperidone differed from the vehicle-treated males (*), the males treated with 1.0 mg/kg of risperidone differed from vehicle-treated males (**), the females treated with 3.0 mg/kg of risperidone differed from the vehicle-treated females (§), or both groups of risperidone-treated females differed from vehicle-treated females (§§). All group differences were significant at p < .05 using a Tukey/Kramer post-hoc test.

Similar to the first experiment, age-dependent differences in body weight were also observed between the three treatment groups in the second locomotor experiment (Treatment × Age interaction: F(18, 216) = 2.1, p = .006)(Figure 1B). Rats treated with the 3.0 mg/kg dose of risperidone weighed less than vehicle-treated rats on postnatal days 35, 38, and 41 (p < .05, Tukey/Kramer). When these rats received behavioral testing at 9 and 12 months of age, body weights did not differ significantly between the treatment groups (data not shown).

The third locomotor experiment involved larger, mixed-sex litters in contrast to the smaller, single-sex litters used in the first two experiments. As noted for the first two experiments, rats treated with risperidone in the third experiment gained less weight in an age-dependent manner (Treatment × Age interaction: F(18, 990) = 5.6, p < .0001; Figure 1C). There was also a significant effect of sex on weight gain that was age-specific (Sex × Age interaction: F(9, 990) = 76.5, p < .0001). Post-hoc tests were conducted separately on each sex to isolate treatment effects at each postnatal day. The female rats treated with 3.0 mg/kg of risperidone weighed significantly less than the vehicle-treated female rats on postnatal days 17, 32, 35, and 41 (p < .05, Tukey/Kramer). The female rats treated with 1.0 mg/kg of risperidone weighed significantly less than the controls on postnatal day 41 (p < .05, Tukey/Kramer). Male rats treated with 1.0 mg/kg of risperidone weighed less than control male rats on postnatal day 17 (p < .05, Tukey/Kramer).

Locomotor activity

The first experiment evaluated the effect of early-life risperidone administration on locomotor activity in young adult rats one week after the cessation of treatment. Rats administered risperidone during development were more active than vehicle-treated rats (Treatment effect: F(2, 23) = 11.4, p = .0004)(Figure 2). Activity in all groups decreased across testing days (Day effect: F(4, 92) = 43.0, p < .0001). There was no Treatment × Test Day interaction. Rats previously treated with 3.0 mg/kg of risperidone were significantly more active than rats treated with vehicle on all days except for the second one and rats previously treated with 1.0 mg/kg of risperidone on the third and fourth days of testing (p < .05, Tukey/Kramer).

Figure 2.

Male rats treated with risperidone from postnatal days 14 – 42 are more active than vehicle-treated male rats when tested for five days beginning on postnatal day 49. Rats administered the 3.0 mg/kg dose of risperidone were more active on all test days, except for day 2, when compared to the vehicle-treated controls, as indicated by the *. Rats administered 3.0 mg of risperidone early in life were significantly more active on test days 3 and 4 than rats administered 1.0 mg/kg of risperidone early in life, as indicated by the §. All group differences were significant at p < .05 using a Tukey/Kramer post-hoc test.

The second locomotor experiment determined the persistence of the effect of early-life risperidone administration on locomotor activity into adulthood. Rats administered 1.0 and 3.0 mg/kg of risperidone during development were significantly more active than vehicle-treated rats (Treatment effect: F(2, 24) = 7.8, p = .002)(Figure 3). Activity decreased in each group across time (Test Week effect: F(8, 192) = 121.4, p < .0001) but there was no Treatment × Test Week interaction. Post-hoc testing indicated that rats administered 1.0 mg/kg of risperidone early in life were more active than vehicle-treated rats at postnatal days 49, 56, 84, and 270 (i.e., nine months of age) (p < .05, Tukey/Kramer). Rats that received 3.0 mg/kg of risperidone across development were more active than vehicle-treated rats on each test day except for postnatal days 63, 70, and 365 (i.e., one year of age) (p < .05, Tukey/Kramer).

Figure 3.

Adult male rats demonstrate persistently greater locomotor activity when administered risperidone from postnatal days 14 – 42. The asterisks indicate ages when the rats previously administered the 1.0 mg/kg or 3.0 mg/kg dose of risperidone were more active than the rats previously treated with vehicle. All statistically significant differences were at p < .05 using a Tukey/Kramer post-hoc test.

The third experiment determined the effects of sex on the heightened activity levels seen in rats administered risperidone during development. Statistically significant effects of Treatment, Sex, and Test Day were found (F(2, 110) = 13.4, p < .0001; F(1, 110) = 11.5; p = .001; F(1, 110) = 132.2, p < .0001 respectively for each effect)(Figure 4). Female and male rats that received 3.0 mg/kg of risperidone early in life were significantly more active on each test day than control rats (p < .05, Tukey/Kramer). Females administered the 3.0 mg/kg of risperidone were significantly more active than females that received 1.0 mg/kg of risperidone on the second day of testing (p < .05, Tukey/Kramer),

Figure 4.

Male and female rats treated with risperidone from postnatal day 14 – 42 are more active for two consecutive test days one week after the cessation of treatment. Asterisks indicate days when rats administered 3.0 mg/kg of risperidone were more active than same-sex, vehicle-treated control rats. Female rats treated with 3.0 mg/kg of risperidone were significantly more active than female rats treated with 1.0 mg/kg of risperidone on day 2 of testing, as indicated by the §. All statistically significant differences were at p < .05 using a Tukey/Kramer post-hoc test.

Since risperidone-treated rats experienced decreased weight gain across the course of treatment from postnatal day 14 – 42, it is possible that the changes in locomotor activity observed in treated rats during adulthood were associated with reduced weight gain during development. In the first locomotor experiment, there was no evidence of a correlation between the weight gain observed between postnatal days 14 – 41 and average locomotor activity on postnatal day 49 (r(24) = .20, p = .92)(Table 1). In the second experiment, a significant negative correlation was discovered between weight gain observed between postnatal days 14 – 42 and average locomotor activity on postnatal day 49 (r(25) = −.65, p < .0001). It should be noted that analyses of the individual group data revealed that there was a significant correlation between weight gain and activity in the rats administered vehicle (r(7) = −.71, p = .03), but the same variables were not correlated in the rats administered 1.0 mg/kg of risperidone (r(7) = −.44, p = .24) or 3.0 mg/kg of risperidone (r(7) = −.51, p = .17). Finally, an analysis of the third locomotor experiment involving male and female rats indicated that weight gain recorded between postnatal days 14 – 41 and average activity on postnatal day 49 were not correlated in male rats (r(58) = −.15, p = .24), but were correlated in the female rats (r(54) = −.49, p < .0001). A significant correlation was observed for the female rats treated with 3.0 mg/kg of risperidone (r(17) = −.52, p = .02), but not for the other two groups (respective coefficients for the vehicle and 1.0 mg/kg of risperidone individual group data: r(17) = −.21, p = .39 and r(16) = −.33, p = .18).

Table 1.

Correlations between weight gain from postnatal days 14 – 41 and locomotor activity at postnatal day 49 within groups in each experiment.

| Experiment | Sex | Vehicle | Risperidone 1.0 | Risperidone 3.0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | r(7) = +.50 | r(6) = −.29 | r(7) = −.003 |

| 2 | Male | r(7) = −.71* | r(6) = −.45 | r(7) = −.51 |

| 3 | Male | r(18) = −.14 | r(18) = −.06 | r(18) = +.11 |

| 3 | Female | r(17) = −.21 | r(16) = −.33 | r(17) = −.52** |

Note.

r values represent (df) = ± Pearson product moment correlation.

p = .03;

p = .02.

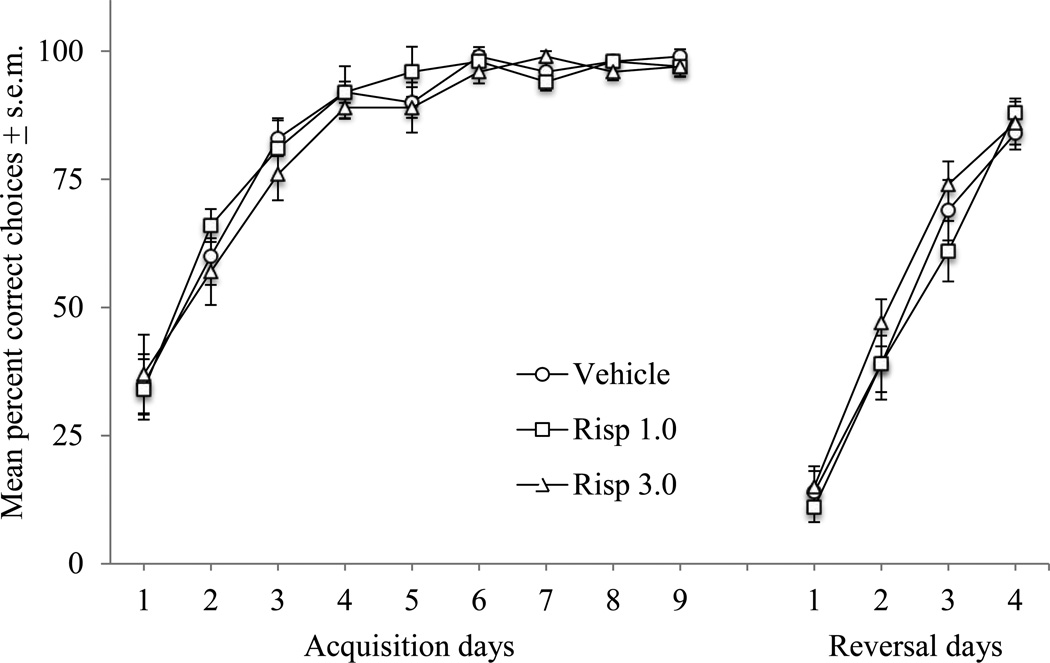

Spatial Reversal Learning

There were no significant effects of early-life risperidone administration on acquisition and reversal learning in the T-maze. Rats in each treatment group significantly increased the percentage of correct arm choices across the nine-day acquisition period (Day effect: F(8, 312) = 111.4, p < .0001)(Figure 5) and over the four days of reversal testing (Day effect: F(3, 117) = 229.8, p < .0001). The time to choose a goal arm did not differ between groups across testing days, but did decline across each phase of testing (Respective day effects across acquisition and reversal phases of testing: F(8, 312) = 3.8, p = .0003 and F(3, 117) = 19.9, p < .0001).

Figure 5.

Acquisition and reversal of a T-maze spatial discrimination task in adult rats administered risperidone on postnatal days 14 – 42. Acquisition testing began on postnatal day 70. There were no significant effects of early-life risperidone administration on correct arm choice during acquisition or reversal testing.

Discussion

There is a little data documenting the long-term behavioral consequences of early-life APD administration, especially regarding the effects of newer, atypical APDs such as risperidone that are more widely prescribed at present (Curtis et al., 2005). This study was conducted in order to begin the process of generating such sorely needed data. We found that prolonged risperidone administration across development led to hyperactivity in male and female rats, an effect that persisted for several months after the cessation of treatment. On the other hand, spatial reversal learning remained intact in adult male rats administered risperidone early in development. These findings indicate that early-life risperidone treatment exerts selective but persistent effects on behavior during adulthood.

Early animal studies, driven by concerns about APD use during pregnancy and nursing, demonstrated long-term behavioral effects of early-life APD treatment (Rosengarten & Friedhoff, 1979; Velley, Blanc, Tassin, Thierry, & Glowinski, 1975). For example, rats exposed to the typical APD, haloperidol, in utero or during the first three weeks of life, were found to exhibit hyperactivity, impaired impulse control, and greater behavioral sensitivity to dopamine agonists and antagonists during adulthood (Cuomo et al., 1981: Scalzo & Spear, 1985; Shalaby & Spear, 1980; although see Rosengarten & Friedhoff, 1979 for contrasting outcomes of prenatal versus postnatal APD treatment). More recently, Soiza-Reilly and Azcurra (2009) administered haloperidol to rats during later stages of development that are more akin to those when human children receive APD treatment. This study uncovered a potential critical period - rats treated with haloperidol during postnatal days 30 – 37 were hyperactive as adults, but those treated during postnatal days 20 – 27 or 40 – 47 were not. While previous research shows the potential for developmental APD treatment to alter later behavior, it leaves two important questions unanswered. One, with the exception of Soiza-Reilly and Azcurra (2009), it is uncertain whether APD treatment during peripubertal periods similar to those when human children would receive APDs affects later behavior in the same manner as treatment immediately prior to or after birth. Second, the long-term effects of early-life treatment with second-generation, atypical APDs, which are more frequently used in children (Patel et al., 2005), have not been studied. The present study addressed these gaps in the literature by determining the long-term consequences of peripubertal risperidone treatment.

The hyperactivity observed in adult rats administered risperidone early in life could reflect a permanent up-regulation of dopamine receptors induced by drug treatment. Developmental risperidone treatment elevates dopamine receptor density in various forebrain regions (Moran-Gates et al., 2007), and prenatal and early postnatal treatment with haloperidol enhances behavioral sensitivity to dopamine agonists in adulthood (Cuomo et al., 1981). In light of these findings, it is not surprising that adult rats administered risperidone during the later stages of weaning and early adolescence were more active. However, other mechanisms besides elevated dopamine receptor density could account for the increased activity. Long-term antagonism of presynaptic D2 receptors by risperidone may encourage greater dopamine release during treatment and lead to an exhaustion of available dopamine pools after the cessation of treatment. A dopamine-deficient state in the forebrain of adult rats exposed to risperidone early in life fits with studies (Cuomo et al., 1981; Velley et al., 1975) that have demonstrated blunted striatal dopamine synthesis in adult rats that were treated with APDs prenatally or for a few weeks after birth. Another possibility is that the hyperactivity induced by early-life risperidone may stem from compensatory changes in other neurotransmitters systems, such as glutamate or serotonin (Choi et al., 2009; 2010). All of these possibilities will need to be considered in future studies.

A key finding from our research was the persistence of the elevated locomotor activity observed in adult rats administered risperidone early in life. While it is well established that prolonged APD administration to adult rats leads to hyperactivity upon the cessation of treatment, such hyperactivity dissipates over a period of time equal to the length of treatment (Muller & Seeman, 1979). In the present study, however, four weeks of daily risperidone administration across development increased locomotor activity for as long as six months after the cessation of treatment. The permanence of this effect indicates the receptor blockade produced by risperidone administration during development altered the postnatal organization of brain regions linked to locomotor activity. If correct, this modification in brain development adjusted the normal set point for activity in treated rats in a manner that persisted well into adulthood.

There are a couple of caveats regarding the locomotor data that bear consideration. First, baseline differences in activity were observed between the three experiments. It is unclear why these differences occurred since the timing, housing, and lighting procedures used to measure activity, at least at postnatal day 49, were identical across experiments. The most likely factor was a difference in the batch of litters used for each experiment, since each batch was received directly from the animal vendor, and dams were not reused across experiments. Continued work in this area will need to be mindful of such extraneous influences on activity. Second, activity measures were recorded during the animals’ light cycle for twenty minutes in a darkened room with no habituation to the testing room. This approach is consistent with much previous work on APD administration and locomotor activity, with the length of testing slightly longer than that reported in some papers (Shalaby & Spear, 1980; Soiza-Reilly & Azcurra, 2009; Wiley, 2008; Wiley & Evans, 2008; 2009; Zuo et al., 2008), and shorter than reported in others (Cuomo et al., 1981; Samaha et al., 2008). Locomotor activity is influenced by multiple parameters that are too numerous to discuss here. Given that these studies have established that at least one aspect of activity, locomotor activity in a test cage for 20 minutes across multiple days, is consistently altered by early-life APD administration, it is now incumbent to explore whether activity under other conditions (e.g., in different periods of the light/dark cycle, in novel versus unfamiliar cages or testing rooms, after pharmacological challenge) is similarly affected by such treatment.

Risperidone treatment does not compromise cognitive function, such as delayed recall, in children who are maintained on the drug for extended periods of time (Pandina et al., 2007; Pandina, Zhu, & Cornblatt, 2009). Whether cognitive function in children remains intact after cessation of treatment or after even longer periods of treatment is unknown. In animal studies, young, pigtail macaque monkeys maintained on relatively low doses of risperidone for eight months display impairments in the reversal phase of a two-object discrimination task following the discontinuation of drug administration (Mandell et al., 2011). Moreover, adult rats treated with APDs during the first few weeks are deficient in their ability to withhold responses for reward (Cuomo et al., 1981; Cuomo et al., 1983). We did not find a significant effect of early-life risperidone administration on reversal learning during adulthood. It is possible that differences between the present study and past ones in the types of tasks used, the drugs and drug doses, and the species studied contributed to the discrepant outcomes. It is also possible that forebrain dopamine systems involved in spatial reversal learning (Haluk & Floresco, 2009; van der Meulen, Joosten, de Bruin, & Feenstra, 2007) are disrupted by early-life risperidone, but that other brain regions, such as the hippocampus (Bardgett et al., 2003; Bardgett et al., 2008), compensate for these drug-induced perturbations. Finally, the tasks used in the present study may not have been sufficiently sensitive to modest changes in forebrain function. The use of extra-dimensional contingencies in the reversal-learning task could have placed a greater cognitive burden on the animals.

Across development, rats administered risperidone weighed less than rats treated with vehicle, especially towards the end of the treatment period. This effect was observed in each experiment despite differences in litter size or inclusion of each sex. This alteration in weight gain calls to mind an important clinical issue – the association of APD treatment in children with altered metabolism and weight gain (Correll et al., 2009). However, the observation of reduced weight gain in rats treated with risperidone stands in contrast to the greater body weight in children treated with APDs (e.g., Correll et al., 2009). Notwithstanding the difference in metabolic rates between humans and rats, and the difficulty of modeling APD-induced weight gain in rodent models (e.g., Baptista et al., 2002), one explanation for this difference is that the sedative action of risperidone, which could explain some of the APD-induced weight gain in humans, likely decreased weight gain in developing rats by simply reducing the amount of active feeding. The decreased weight gain seen in the present study also fits with studies of APD treatment in young monkeys, where transient decreases in bone density have been reported (Sackett, Unis, & Crouthamel, 2010), and in rats, where adolescent treatment with the APD, olanzapine, produces subtle decreases in weight gain (Llorente-Berzal et al., 2012). It should also be noted that the difference in weight gain observed between treatment groups during development does not appear to contribute to the hyperactivity seen in adult rats administered risperidone early in life. Overall correlations between weight gain and activity were only observed in the second experiment, and only in females in the third experiment. When correlational analyses were extended to the individual groups within these experiments, significant correlations only remained for the vehicle-treated group in the second experiment, and the group of females administered 3.0 mg/kg of risperidone in the third experiment. The inconsistent nature of these correlations suggests that the increased activity observed adult rats treated with risperidone early in life is not a direct product of drug-induced changes in weight gain during development.

Risperidone was chosen for study since it is the most widely prescribed APD in pediatric populations (Curtis et al., 2005). It is possible and even likely that early-life administration of other APDs, especially atypical APDs such as aripiprazole and quetiapine, which have approved for use in children and younger adolescents in the United States, will have different long-term effects on behavior. Early postnatal treatment with haloperidol leads to a supersensitivity to dopamine agonists in adult rats (Cuomo et al., 1981) that is not seen after early postnatal treatment with clozapine (Cuomo et al., 1983). Likewise, monkeys treated with quetiapine early in life do not exhibit the decrement in reversal learning observed in monkeys after cessation of early-life risperidone treatment (Mandell et al., 2011). While these drug-specific effects of APDs should discourage generalizations about the impact of early-life APD treatment on behavior, the effects of risperidone remain of interest since it is the most likely APD to be prescribed to children, and leads to significant behavioral alterations upon treatment cessation as evidenced in the present study and others (Mandell et al., 2011).

Not only will it be important to identify outcomes in response to different APDs, but another objective of future work should be to consider alternative dosing strategies. A single dose per day approach was used in this study since many similar reports have used an identical strategy (Choi et al., 2009; 2010; Cuomo et al., 1981; Cuomo et al., 1983; Mandell et al., 2011; Moran-Gates et al., 2006; Soiza-Reilly & Azcurra, 2009) or provided lactating dams with single daily APD doses (Scalzo & Spear, 1985; Shalaby & Spear, 1980) which, in the case of the present study, would not have allowed for continued drug administration past weaning. One issue with this approach is that most APDs have a half-life of a few hours in rats (Kapur et al., 2003). Thus, single daily dosing strategies in rats and mice produce within-day transient fluctuations of blood drug levels and brain receptor occupancy that are likely not experienced clinically by human receiving APDs. Future studies should consider the use of multiple-dosing per day strategies or continuous drug infusion via minipumps. However, it should be noted that no single animal model of APD drug delivery is exemplary. For instance, Samaha et al. (2008) reported that haloperidol injected subcutaneously once a day showed superior efficacy in some behavioral models of APD action in adult rats as opposed to continuous haloperidol infusion achieved through minipump infusion.

The present study shows that early-life risperidone administration has discernable and specific effects on behavior during adulthood. This outcome gives empirical weight to concern regarding the use of APDs in pediatric populations. At the very least, limiting the duration of APD treatment will be in the best interest of the long-term well-being of the child. Further work is needed to ascertain the effects of early-life risperidone treatment on other indices of behavioral and cognitive function during adulthood, as well as to examine the long-term behavioral effects of other APDs that are currently being used in pediatric populations (Kuehn 2009). Such studies will help to ensure that the treatment of children with APDs is performed in a way that considers their long-term effects in an informed manner.

Disclosures and Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (8P20GM103436), National Institute of Mental Health (1R15MH094955), and the Center for Integrated Natural Sciences and Mathematics at Northern Kentucky University. These funding sources had no other role in the research other than funding.

All authors contributed in a significant way to the manuscript and have read and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Arnt J. Differential effects of classical and newer antipsychotics on the hypermotility induced by two dose levels of D-amphetamine. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1995;283:55–62. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00292-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baptista T, Araujo de Baptista E, Ying Kin NM, Beaulieu S, Walker D, Joober R, Richard D. Comparative effects of the antipsychotics sulpiride or risperidone in rats. I: bodyweight, food intake, body composition, hormones and glucose tolerance. Brain Research. 2002;957:144–151. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03616-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardgett ME. Behavioral models of atypical antipsychotic drug action. In: Csernansky J, Laurello J, editors. Atypical Antipsychotics: From Bench to Bedside. New York: Marcel Dekker; 2004. pp. 61–93. [Google Scholar]

- Bardgett ME, Boeckman R, Krochmal D, Fernando H, Ahrens R, Csernansky JG. NMDA receptor blockade and hippocampal neuronal loss impair fear conditioning and position habit reversal in C57Bl/6 mice. Brain Research Bulletin. 2003;60:131–142. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(03)00023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardgett ME, Points M, Ramsey-Faulkner C, Topmiller J, Roflow J, McDaniel T, Griffith MS. The effects of clonidine on discrete-trial delayed spatial alternation in two rat models of memory loss. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:1980–1991. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardgett ME, Points M, Kleier J, Blankenship M, Griffith MS. The H3 antagonist, ciproxifan, alleviates the memory impairment but enhances the motor effects of MK-801 (dizocilpine) in rats. Neuropharmacology. 2010;59:492–502. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi YK, Gardner MP, Tarazi FI. Effects of risperidone on glutamate receptor subtypes in developing rat brain. European Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;19:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi YK, Moran-Gates T, Gardner MP, Tarazi FI. Effects of repeated risperidone exposure on serotonin receptor subtypes in developing rats. European Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;20:187–194. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correll CU, Manu P, Olshanskiy V, Napolitano B, Kane JM, Malhotra AK. Cardiometabolic risk of second-generation antipsychotic medications during first-time use in children and adolescents. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;302:1765–1773. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuomo V, Cagiano R, Coen E, Mocchetti I, Cattabeni F, Racagni G. Enduring behavioural and biochemical effects in the adult rat after prolonged postnatal administration of haloperidol. Psychopharmacology. 1981;74:166–169. doi: 10.1007/BF00432686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuomo V, Cagiano R, Mocchetti I, Coen E, Cattabeni F, Racagni G. Behavioural and biochemical effects in the adult rat after prolonged postnatal administration of clozapine. Psychopharmacology. 1983;81:239–243. doi: 10.1007/BF00427270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis LH, Masselink LE, Østbye T, Hutchison S, Dans PE, Wright A, Schulman KA. Prevalence of atypical antipsychotic drug use among commercially insured youths in the United States. Archives of Pediatric & Adolescent Medicine. 2005;159:362–366. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.4.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domino ME, Swartz MS. Who are the new users of antipsychotic medications? Psychiatric Services. 2008;59:507–514. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.5.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SM. The role of estradiol and progesterone in modulating the subjective effects of stimulants in humans. Experimental & Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2007;15:418–426. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.5.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SM, Foltin RW. Does the response to cocaine differ as a function of sex or hormonal status in human and non-human primates? Hormones & Behavior. 2010;58:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanton J, Gleason MM. Psychopharmacology and preschoolers: a critical review of current conditions. Child & Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2009;18:753–771. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haluk DM, Floresco SB. Ventral striatal dopamine modulation of different forms of behavioral flexibility. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:2041–2052. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapur S, VanderSpek SC, Brownlee BA, Nobrega JN. Antipsychotic dosing in preclinical models is often unrepresentative of the clinical condition: a suggested solution based on in vivo occupancy. Journal of Pharmacology & Experimental Therapeutics. 2003;305:625–631. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.046987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalverdijk LJ, Tobi H, van den Berg PB, Buiskool J, Wagenaar L, Minderaa RB, de Jong-van den Berg LT. Use of antipsychotic drugs among Dutch youths between 1997 and 2005. Psychiatric Services. 2008;59:554–560. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.5.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuehn BM. FDA panel OKs 3 antipsychotic drugs for pediatric use, cautions against overuse. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;302:833–834. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llorente-Berzal A, Mela V, Borcel E, Valero M, López-Gallardo M, Viveros MP, Marco EM. Neurobehavioral and metabolic long-term consequences of neonatal maternal deprivation stress and adolescent olanzapine treatment in male and female rats. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62:1332–1341. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandell DJ, Unis A, Sackett GP. Post-drug consequences of chronic atypical antipsychotic drug administration on the ability to adjust behavior based on feedback in young monkeys. Psychopharmacology. 2011;215:345–352. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-2147-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran-Gates T, Grady C, Shik Park Y, Baldessarini RJ, Tarazi FI. Effects of risperidone on dopamine receptor subtypes in developing rat brain. European Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;17:448–455. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller P, Seeman P. Dopaminergic supersensitivity after neuroleptics: time-course and specificity. Psychopharmacology. 1978;60:1–11. doi: 10.1007/BF00429171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandina GJ, Bilder R, Harvey PD, Keefe RS, Aman MG, Gharabawi G. Risperidone and cognitive function in children with disruptive behavior disorders. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;62:226–234. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandina GJ, Zhu Y, Cornblatt B. Cognitive function with long-term risperidone in children and adolescents with disruptive behavior disorder. Journal of Child & Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2009;19:749–756. doi: 10.1089/cap.2008.0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel NC, Crismon ML, Hoagwood K, Johnsrud MT, Rascati KL, Wilson JP, Jensen PS. Trends in the use of typical and atypical antipsychotics in children and adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44:548–556. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000157543.74509.c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins TW, Arnsten AF. The neuropsychopharmacology of fronto-executive function: monoaminergic modulation. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2009;32:267–287. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosengarten H, Friedhoff AJ. Enduring changes in dopamine receptor cells of pups from drug administration to pregnant and nursing rats. Science. 1979;203:1133–1135. doi: 10.1126/science.570724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sackett G, Unis A, Crouthamel B. Some effects of risperidone and quetiapine on growth parameters and hormone levels in young pigtail macaques. Journal of Child & Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2010;20:489–493. doi: 10.1089/cap.2010.0018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samaha AN, Reckless GE, Seeman P, Diwan M, Nobrega JN, Kapur S. Less is more: antipsychotic drug effects are greater with transient rather than continuous delivery. Biological Psychiatry. 2008;15:145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scalzo FM, Spear LP. Chronic haloperidol during development attenuates dopamine autoreceptor function in striatal and mesolimbic brain regions of young and older adult rats. Psychopharmacology. 1985;85:271–276. doi: 10.1007/BF00428186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalaby IA, Spear LP. Chronic administration of haloperidol during development: later psychopharmacological responses to apomorphine and arecoline. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, & Behavior. 1980;13:685–690. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(80)90012-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soiza-Reilly M, Azcurra JM. Developmental striatal critical period of activity-dependent plasticity is also a window of susceptibility for haloperidol induced adult motor alterations. Neurotoxicology & Teratology. 2009;31:191–197. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear LP. The adolescent brain and age-related behavioral manifestations. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2000;24:417–463. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Meulen JA, Joosten RN, de Bruin JP, Feenstra MG. Dopamine and noradrenaline efflux in the medial prefrontal cortex during serial reversals and extinction of instrumental goal-directed behavior. Cerebral Cortex. 2007;17:1444–1453. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhl057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velley L, Blanc G, Tassin JP, Thierry AM, Glowinski J. Inhibition of striatal dopamine synthesis in rats injected chronically with neuroleptics in their early life. Naunyn Schmiedeberg’s Archives of Pharmacology. 1975;288:97–102. doi: 10.1007/BF00501817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley JL. Antipsychotic-induced suppression of locomotion in juvenile, adolescent and adult rats. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2008;578:216–121. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley JL, Evans RL. Evaluation of age and sex differences in locomotion and catalepsy during repeated administration of haloperidol and clozapine in adolescent and adult rats. Pharmacological Research. 2008;58:240–246. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley JL, Evans RL. To breed or not to breed? Empirical evaluation of drug effects in adolescent rats. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience. 2009;27:9–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo J, Liu Z, Ouyang X, Liu H, Hao Y, Xu L, Lu XH. Distinct neurobehavioral consequences of prenatal exposure to sulpiride (SUL) and risperidone (RIS) in rats. Progress in Neuropsychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2009;32:387–397. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]