Abstract

Purpose of review

To highlight recent evidence from clinical trials of anti-Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and non-anti-TNF biologics for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) focused on comparative clinical efficacy including safety outcomes and medication discontinuation.

Recent findings

Patients with RA are sometimes able to attain low disease activity or remission since the introduction of biologic therapy for RA. Biologics like anti-TNF, anti-interleukin-6 (IL-6), anti-CD20 and those that modulate T-cell co-stimulation have consistently shown good efficacy in patients with RA. Preliminary data from comparative efficacy studies to evaluate potential differences in between anti-TNF and non-anti-TNF biologics have shown little differences among these. There is ongoing work in comparative efficacy to answer this question further.

Summary

Biologic therapy in RA has significantly changed the course of RA in the last decade. Recently published CTs have been focused on comparative efficacy, cardiovascular safety of biologics and potential anti-TNF therapy discontinuation in patients with RA.

Keywords: rheumatoid arthritis, anti-Tumor Necrosis factor, non-tumor necrosis factor biologic

Introduction

The introduction of biologic medicines for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) has resulted in a significant improvement in clinical and radiographic outcomes among patients with RA over the last 10 years. Evidence has shown that low disease activity (LDA) and even remission in RA is achievable with combination of biologics and non-biologic disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) in a larger proportion than with less aggressive, non-biologic DMARDs regimens (1). Comparative efficacy research has been a major area of interest in the last several years so as to allow more direct comparisons between biologics and to establish evidence-based differences or similarities in both efficacy and safety.

This article summarizes recent data from controlled trials on anti-TNF and non-anti-TNF biologics for the treatment in RA. The four key domains to be covered will include efficacy of new therapies (including new formulations), comparative efficacy between approved agents, the possibility of anti-TNF discontinuation, and potential effects on cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors and risk of cardiovascular events.

Efficacy studies for anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF) and non-TNF biologics

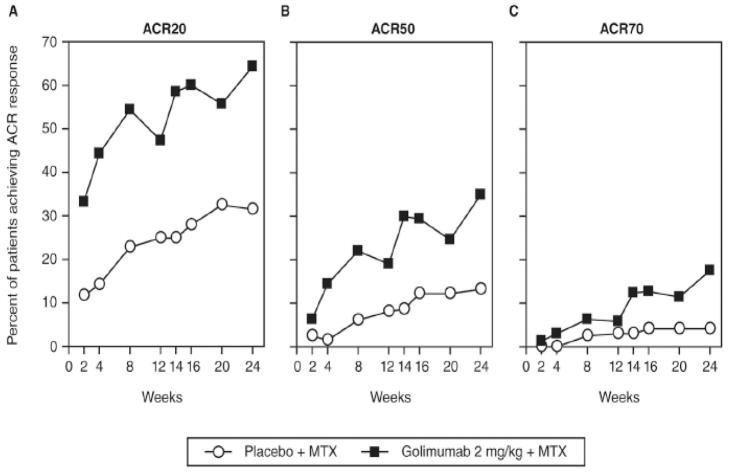

Recently published efficacy trials have provided results for new routes of administration for several currently approved biologics. These include intravenous (IV) golimumab and subcutaneous (SC) tocilizumab. In a phase III trial of IV golimumab at a dose of 2 mg/kg + MTX, golimumab was given at weeks 0, 4 and then every 8 weeks for a total of 24 weeks (2). At week 14, IV golimumab showed significant efficacy based on American College of Rheumatology response (ACR) 20 compared to placebo (59% vs. 25%, p < 0.001) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Proportion of patients receiving methotrexate and placebo (empty circles) or golimumab 2mg/kg intravenously and methotrexate (black squares) achieving ACR20 (A), ACR50 (B) and ACR70 (C) responses over time through week 24. ACR20, ACR50 and ACR 70- American College of Rheumatology 20%, 50% and 70% response criteria, MTX = methotrexate (2).

A phase III trial of SC TCZ presented at the 2012 ACR meeting in Washington D.C. showed non-inferiority of TCZ 162mg SC q week to TCZ 8mg/kg IV every month. The primary outcome was the proportion of patients in each group meeting the ACR20 criteria at week 24 using a 12% non-inferiority margin (3). At Week 24, 69.4% (95% CI: 65.5, 73.2) of TCZ SC-treated patients versus 73.4% (95% CI: 69.6, 77.1) of TCZ IV-treated patients achieved an ACR20 response (3), which satisfied the non-inferiority endpoint. The ACR 50/70 responses were likewise comparable between the SC and IV TCZ, as was safety. Another trial evaluated TCZ 162mg SC q 2weeks (approximating the 4mg/kg IV monthly dose) to placebo SC and showed that significantly more patients receiving TCZ achieved ACR20 responses at week 24 compared to placebo (60.9% vs 31.5%) and ACR50 (39.8% vs. 12.3%) and ACR70 responses (19.7% vs. 5.0%) were higher as well (4).

A phase IIIb trial of Certolizumab pegol (CZP) was conducted in a diverse RA population that included patients with different disease durations and different prior and background treatments for RA including those who were biologic naïve and also those with previous anti-TNF use (5)*. At 12 weeks, 51.1% of the certolizumab-treated patients achieved ACR20 compared to 25.9% in the placebo group. Among patients who previously used anti-TNF, the proportions of ACR20 and ACR50 vs. placebo were 47.2 vs. 27.5 and 21.6 vs. 11.3 respectively. This data suggest that even patients who have previously received anti-TNF therapy can achieve a meaningful benefit with CZP, and the magnitude of benefit is comparable to biologic naïve patients initiating CZP.

Additional biologics in early phase development for RA are shown in Table 1 and include new targets (e.g. IL-17) (6–8), anti- S-CSF (9), monoclonal antibody against B-cell activating factor (BAFF) (10, 11) and new methods to block cytokine signaling (e.g. blocking IL-6 itself rather than its receptor) (12, 13).

Table 1.

Summary of Biologics under Development for Rheumatoid Arthritis

| New Biologic targets | Description | Phase of Clinical Development for rheumatoid arthritis |

|---|---|---|

| Secukinumab (6) | Fully human IgG1k mAb against IL-17A | Phase II |

| ASK8007 (7) | Monoclonal antibody blocking osteopontin | Proof of concept study |

| Ixekizumab LY2439821 (8) | Humanised, hinge- modified IgG4 mAb against IL-17A | Phase II |

| Brodalumab (AMG 827) (8) | Fully human IgG2 mAb against IL-17RA receptor | Phase II |

| MOR103 (9) | Fully human monoclonal antibody (mAb) directed towards human GM- CSF | Phase 1b/2a |

| Tabalumab (10, 11) | Fully human IgG4 monoclonal antibody, neutralizes soluble and membrane-bound B cell activating factor (BAFF). | Phase II |

| New Methods of blocking cytokine signaling | ||

| Sirukumab (12) | Monoclonal antibody against soluble IL-6 rather than IL-6 receptor | Phase III clinical trials are ongoing. |

| BMS945429 (also known as ALD518) (13) | MAB directed against IL-6 rather than the IL-6 receptor | Phase II |

Comparative efficacy of anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF) and non-TNF biologics to non-biologic DMARDs and to each other

The Treatment of Early Aggressive RA (TEAR) trial (14)** was an investigator initiated, randomized, blinded study of early RA patients (median disease duration 4 months) that compared 1) MTX, hydroxychloroquine, and sulfasalazine in combination (i.e. triple therapy, TT) to 2) combination therapy with etanercept (ETA) + MTX to 3) MTX monotherapy for 6 months, with mandatory step-up to TT or ETA only if the DAS28 ≥ 3.2, resulting in 4 arms. Clinical outcomes were similar among all treatment groups at the end of 2 years. A statistically significant difference in radiographic progression favoring the ETA treatment arms was found, although it was small in magnitude. Consistent with the TEAR results, the 2-year follow up of the non-blinded, parallel-group Swedish Farmacotherapy (Swefot) trial (15) showed that although anti-TNF treated patients using infliximab had better radiographic outcomes, there was no difference between TT and infliximab in clinical outcomes at 18 or 24 months. Likewise, there were no differences between the two treatment arms in utility or quality-adjusted life-years (16).

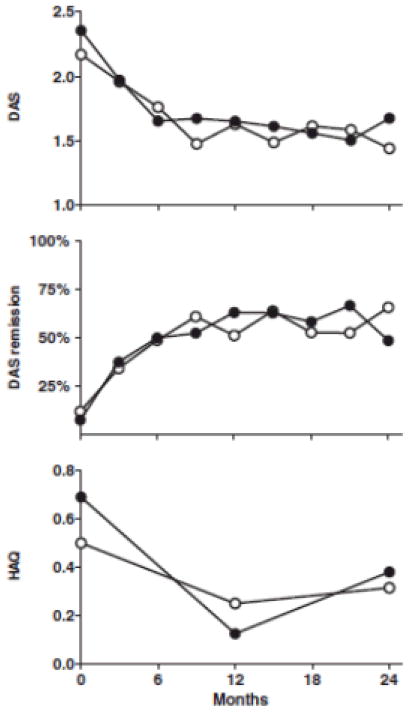

A strategy trial (17) evaluated aggressive vs. conventional treatment for early RA patients with only moderately active disease (between 2 and 5 swollen joints). The aggressive treatment arm included adalimumab (ADA) whereas conventional treatment was according to the rheumatologist’s discretion with non-biologic DMARDs and without prednisone. Remission rates were 66% and 49% and HAQ decreased by a mean of −0.09 (0.50) and −0.25 (0.59) units (p=0.06) in the aggressive and conventional care group, respectively. The median SHS increase between 0 and 2 years was 0 (IQR 0–1.0) in the entire aggressive group and 0.25 (IQR 0–2.5) in the entire conventional care group (P = 0.17). The sample size of this study was small (n=80) which may explain why significant differences were not found (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

DAS and HAQ scores for tight-control vs. conventional care treatment approaches in patients with only moderately active rheumatoid arthritis. Upper: mean DAS at each time point. Middle: remission rates (percentage of patients with DAS < 1.6) at each time point. Bottom: median HAQ scores at baseline, 1 and 2 years. Open dots represent the tight-control group and closed dots represent the conventional care group (17).

While the aforementioned trials compared biologics with aggressive DMARDs therapy, results from head to head clinical trials (CT) comparing anti-TNF biologics to one another or to non-anti-TNF biologics are now available. A trial where patients with established active RA despite prior or current use of two DMARDs including MTX and who were biologic naive compared ADA 40 mg every 2 weeks vs. ETA 50 mg weekly, both in combination with MTX. The proportion of good, moderate and non-responders based on DAS28 at 52 weeks were 26.3%, 33.3% and 40.4%, respectively, for ADA versus 16.7%, 31.7% and 51.7%, respectively, for ETA (p=0.158) (18)**. Another study comparing ETA vs. ADA with respect to immunogenicity showed that the overall treatment response was comparable between ETA and ADA-treated patients (adjusted odds ratio (OR) 0.81 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.54–1.21]) (19)**. In a comparison between ETA and patients receiving ADA without anti-ADA antibodies the odds ratio (OR) for achieving better clinical outcome was 0.55, 95% CI (0.37–0.83) (p= 0.004), favoring adalimumab; when ETA was compared to ADA patients with anti-ADA antibodies the OR was 2.62 (1.19–5.75) (p = 0.017), favoring etanercept. This data suggest that ADA appears to be more effective in patients who do not develop antibodies to the drug and that those who developed anti-ADA antibodies (26% of ADA patients) had far less favorable treatment outcomes when compared to ETA (19)**.

The Abatacept (ABA) or infliximab versus placebo, a Trial for Tolerability, Efficacy and Safety in Treating rheumatoid arthritis (ATTEST) trial (20), found no difference in efficacy between ABA vs. infliximab in patients with incomplete response to MTX-IR that were biologic naïve. An open extension study of the ATTEST trial showed that changing from infliximab, regardless of clinical response, to ABA provided sustained or increased efficacy after the change in medications according to DAS28 (21)*. A larger non-inferiority trial compared ADA vs. ABA SC in combination with MTX in MTX-IR patients showed at 1 year, 64.8% and 63.4%of patients demonstrated an ACR20 response; the estimated difference [95% CI] between groups was 1.8 [−5.6, 9.2]) demonstrating the non-inferiority of ABA versus ADA. All efficacy measures showed similar results and kinetics of response. Rates of radiographic non-progression using van der Heijde modified Sharp total scores smallest detectable change (mTSS.SDC) were 84.8% and 88.6%; mean changes from baseline in mTSS of 0.58 and 0.38. Discontinuation due to adverse events were 3.1% versus 6.1%, due to SAEs were 1.3% versus 3% ABA vs. ADA respectively (22)**. Preliminary results of a trial designed to test the superiority of biologic monotherapy in patients with RA of ≥6-mo duration who were MTX intolerant compared TCZ monotherapy to ADA. Results of that study showed more favorable TCZ compared to ADA (change in DAS28 of −3.3 and −1.9, p < 0.001) (23).

Anti-TNF discontinuation trials

Discontinuation of biologic therapy, particularly anti-TNF therapy, has been suggested as a possibility to consider whether patients doing well and who stop therapy might maintain low disease activity (LDA) or remission off biologic treatment, with or without background therapies like MTX. A prospective cohort studied which factors were associated with successful discontinuation of anti-TNF and found that early combination therapy (MTX + anti-TNF) within the first 6 months of symptoms of RA (24) was the only clinical predictor identified. Another study conducted among patients who agreed to discontinue ADA as part of routine clinical practice after sustained remission for ≥ 6 months (DAS28 <2.6), showed that 12-months after discontinuing ADA, 36% of patients remained in remission by DAS28 <2.6 and 45% were in remission based upon a simplified disease activity index (SDAI) ≤ 3.3. Additionally, 95% showed no evidence of radiographic progression over that year (25).

A post-hoc analysis after 4 years of treatment of the “Behandel Strategieën” BeST study (26), was published in which patients who have achieved a DAS44 < 1.6 discontinued treatment gradually until be completely off medication. Between months 24–48, 20% of all patients achieved drug-free remission for a mean duration of 9 months. At year 4, 13% achieved drug-free remission with a mean duration of 11 months. Factors associated with drug free remission were the absence of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP), male gender and shorter RA symptom duration (<6 months). A majority of patients (94%) in which therapy was withdrawn that experienced an increase in disease activity return to either remission or LDA once treatment with the last DMARDs used (either MTX or sulfasalazine) was reinitiated. Treatment was intensified if DAS44 >2.4. These patients did not experience any radiographic progression (27).

Preliminary results for more recent trials that discontinued anti-TNF biologic in early RA patients have been recently published in abstract form. An randomized CT (RCT) comparing ADA vs. MTX monotherapy showed that treatment with ADA + MTX was significantly superior to MTX monotherapy at 26 weeks with respect to clinical, radiographic and functional outcomes in patients with early active RA who were treatment naïve (28). A second phase of the same trial with 52-week follow up (29) identified patients who achieved LDA at 2 consecutive visits after 6 months of ADA treatment and randomized them to discontinue or continue ADA while continuing MTX. Among those who continued MTX but discontinued ADA, 51% remained in remission by SDAI ≤3.3 one year later, and 84% remained in LDA (SDAI ≤11). Moreover, only 8% more patients who continued ADA remained in remission (p = 0.07) and 11% more remained in LDA (p = 0.10) compared to those who discontinued ADA, suggesting that many patients in this trial did not need ongoing ADA therapy to continue to do well. In a similarly designed study of ETA, patients had to have achieved LDA or remission at one visit at 6 months before discontinuation of ETA. Patients who discontinued ETA experienced a significant increase in disease activity compared to those that continued either 50 mg of ETA or a reduced ETA dose of 25 mg weekly (30). These results suggest that patients needed to have a greater depth of treatment benefit (ideally clinically remission, not just LDA) that is more sustained (not just a single visit) before discontinuation of anti-TNF therapy should be considered. Predictors of remission are not yet available, although a small observational study suggested that lack of power Doppler signal on musculoskeletal ultrasound may be useful to predict successful discontinuation of RA therapy (31)*.

Clinical trials on assessment of cardiovascular risk with tocilizumab

Results from RCTs of TCZ, an IL-6 receptor blocker, have raised concerns regarding a possible increase in the risk of CVD given increased lipid levels observed with use of this agent (32). More recent trials have been developed with the objective of clarifying CVD risk with TCZ use. An open-label trial conducted in Japan of biologic and MTX-naïve RA patients with DAS28 > 3.2 evaluated the effect of TCZ vs. ETA and ADA monotherapy on arterial stiffness (33)*. They measured 2 different parameters to determine arterial stiffness: cardio-ankle vascular index (CAVI) (34) and the augmentation index corrected to a heart rate of 75 bpm (Aix@75) (35). Both of these measures are surrogate parameters of arterial stiffness and are commonly used as predictors of CVD risk. At the end of the 24 weeks of follow-up and compared to baseline, TCZ, ETA and ADA all significantly and comparably decreased the CAVI and Aix@75. TCZ increased the fasting TC levels significantly compared to baseline 18.0 ± 5.2 mg/dl (p=0.03) and compared to ADA and ETA (p=0.032 and 0.024 respectively). There were no significant changes with any of the biologics in carotid-intima media thickness and carotid artery plaque.

Another RCT of TCZ evaluated the effects of TCZ on lipid particle size and arterial stiffness by pulse wave velocity (36). TCZ did not have a statistically significant effect on the concentration of small low density lipoprotein (LDL) particles, considered pro-atherogenic (37, 38), at either week 12 (mean difference, 0.0 [95% CI, −115.0, 115.0] nmol/L) or week 24 (mean difference, 11.2 [95% CI, −106.7, 129.1] nmol/L). TCZ was associated with a median (IQR) increase in total cholesterol (TC) at 12 weeks of 12.6% (−0.05, 23.9); LDL, 10.6% (1.0, 28.9); HDL, 3.1% (−6.6, 12.7) and triglycerides, 28.1% (−1.7, 63.5). Conversely, a substantial decrease (>30%) in lipoprotein (a) (39), a risk factor known to be associated with vascular events, occurred in TCZ-treated patients compared with placebo patients. In terms of arterial stiffness, a small significant increase at 12 weeks in favor of placebo was observed, although there was no difference between treatment groups at 24 weeks.

The data presented in this section suggest that the impact of TCZ on CVD is not necessarily detrimental and that the numeric increase in lipid molecules is not as harmful as initially posited since more specific parameter of CVD like arterial stiffness and LDL particle size are either affected in a positive way or negligibly by TCZ.

Conclusion

New formulations of existing compounds may provide greater treatment options for the management of RA. At least when used with background MTX, most trials have not identified important differences in efficacy across biologics available for RA, although there may be advantages for some when gives as monotherapy. Several new trials suggest that a meaningfully large subgroup of RA patients can be withdrawn successfully from anti-TNF biologic treatment. However, further characterization of predictors of successful withdrawal, and requiring a greater and more sustained depth of clinical response before discontinuing, is probably warranted than was studied in most discontinuation trials. Finally, the increases in lipid molecules observed with TCZ and some other biologics (e.g. anti-TNF therapy) does not appear to be detrimental to CVD risk and underscores the need to better understand the complex interactions between systemic inflammation, lipids, and CVD risk and outcomes for patients with RA.

Key Points.

Newer formulations of tocilizumab (subcutaneous versus original intravenous formulation) and golimumab (intravenous versus original subcutaneous formulation) have shown similar efficacy to their original formulations among patients with rheumatoid arthritis

Head to head clinical trials among biologics for rheumatoid arthritis have not found major differences across biologics when given with background methotrexate

Current studies on discontinuation of anti-tumor necrosis factor for rheumatoid arthritis suggest that patients who had greater depth of treatment benefit (ideally clinically remission) that is more sustained (several months or longer), discontinuation of anti-TNF therapy could be considered.

Extensive studies to determine the impact of tocilizumab and other biologics on cardiovascular disease in patient with rheumatoid arthritis suggest that the numeric increase in lipid molecules may not be harmful as initially posited.

Footnotes

Disclosures:

Dr. Navarro-Millán- Nothing to disclose

Dr. Jeffrey R Curtis -JRC has received consulting fees and research grants for unrelated work from Amgen, Abbott, BMS, Pfizer, Eli Lilly, Janssen, UCB, Roche/Genentech, and CORRONA.

References

- 1.Emery P, Kvien TK, Combe B, Freundlich B, Robertson D, Ferdousi T, et al. Combination etanercept and methotrexate provides better disease control in very early (<=4 months) versus early rheumatoid arthritis (>4 months and <2 years): post hoc analyses from the COMET study. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2012;71(6):989–92. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201066. Epub 2012/03/10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weinblatt ME, Bingham CO, 3rd, Mendelsohn AM, Kim L, Mack M, Lu J, et al. Intravenous golimumab is effective in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis despite methotrexate therapy with responses as early as week 2: results of the phase 3, randomised, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled GO-FURTHER trial. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2012 doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201411. Epub 2012/06/05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burmester GR, Rubbert-Roth A, Cantagrel AG, Hall S, Leszczynski P, Feldman D, Rangara MJ. A Randomized, Double-Blind, Parallel Group Study of the Safety and Efficacy of Tocilizumab SC Versus Tocilizumab IV, in Combination with Traditional Dmards in Patients with Moderate to Severe RA. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2012;64(Supplement 10):2545. [Google Scholar]

- 4.AJK A Randomized, Double-Blind, Parallel-Group Study of the Safety and Efficacy of Tocilizumab Subcutaneous Versus Placebo in Combination with Traditional Dmards in Patients with Moderate to Severe Rheumatoid Arthritis (BREVACTA) Arthritis and rheumatism. 2012;64(Supplement 10) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weinblatt ME, Fleischmann R, Huizinga TW, Emery P, Pope J, Massarotti EM, et al. Efficacy and safety of certolizumab pegol in a broad population of patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: results from the REALISTIC phase IIIb study. Rheumatology. 2012;51(12):2204–14. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kes150. Epub 2012/08/28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Genovese MC, Durez P, Richards HB, Supronik J, Dokoupilova E, Mazurov V, et al. Efficacy and safety of secukinumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a phase II, dose-finding, double-blind, randomised, placebo controlled study. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2012 doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201601. Epub 2012/06/26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boumans MJ, Houbiers JG, Verschueren P, Ishikura H, Westhovens R, Brouwer E, et al. Safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and efficacy of the monoclonal antibody ASK8007 blocking osteopontin in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised, placebo controlled, proof-of-concept study. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2012;71(2):180–5. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200298. Epub 2011/09/16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel DD, Lee DM, Kolbinger F, Antoni C. Effect of IL-17A blockade with secukinumab in autoimmune diseases. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2012 doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202371. Epub 2012/12/21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Behrens FOM, Stoilov R, Wiland P, Huizinga T, Berenfus V, Tak P, Vladeva S, Rech J, Rubbert-Roth A, Korkosz M, Rekalov D, Zupanets I, Ejbjerg B, Geiseler J, Fresenius J, Korolkiewicz R, Schottelius A, Burkhardt H. First in Patient Study of Anti-GM-CSF Monoclonal Antibody (MOR103) in Active Rheumatoid Arthritis: Results of a Phase 1b/2a Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. 2012 [updated Nov 2012; cited 20121/30/2013]; Presentation]. Available from: http://www.morphosys.com/sites/default/files/presentations/MOR121113_ACR_2012_Abstract_L11%20ppt.pdf.

- 10.Genovese MC, Bojin S, Biagini I, Mociran E, Cristei D, Mirea G, et al. Tabalumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis with an inadequate response to methotrexate and naive to biologic therapy. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2013 doi: 10.1002/art.37820. Epub 2013/01/30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Genovese MC, Fleischmann RM, Greenwald M, Satterwhite J, Veenhuizen M, Xie L, et al. Tabalumab, an anti-BAFF monoclonal antibody, in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis with an inadequate response to TNF inhibitors. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2012 doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202775. Epub 2012/12/27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu Z, Bouman-Thio E, Comisar C, Frederick B, Van Hartingsveldt B, Marini JC, et al. Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and safety of a human anti-IL-6 monoclonal antibody (sirukumab) in healthy subjects in a first-in-human study. British journal of clinical pharmacology. 2011;72(2):270–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.03964.x. Epub 2011/03/12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mease P, Strand V, Shalamberidze L, Dimic A, Raskina T, Xu LA, et al. A phase II, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled study of BMS945429 (ALD518) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis with an inadequate response to methotrexate. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2012;71(7):1183–9. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200704. Epub 2012/02/14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moreland LW, O’Dell JR, Paulus HE, Curtis JR, Bathon JM, St Clair EW, et al. A randomized comparative effectiveness study of oral triple therapy versus etanercept plus methotrexate in early aggressive rheumatoid arthritis: the treatment of early aggressive rheumatoid arthritis trial. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2012;64(9):2824–35. doi: 10.1002/art.34498. Epub 2012/04/18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Vollenhoven RF, Geborek P, Forslind K, Albertsson K, Ernestam S, Petersson IF, et al. Conventional combination treatment versus biological treatment in methotrexate-refractory early rheumatoid arthritis: 2 year follow-up of the randomised, non-blinded, parallel-group Swefot trial. Lancet. 2012;379(9827):1712–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60027-0. Epub 2012/04/03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karlsson JANM, Nilsson J-A, Petersson IF, Bratt J, van Vollenhoven RF, Ernestam S, Geborek P. Addition of infliximab compared with addition of sulfasalazine and hydroxychloroquine to methotrexate in early rheumatoid arthritis: 2-year quality of life results of the randomised, controlled Swefot trial. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2012;71(Suppl 3):106. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Eijk IC, Nielen MM, van der Horst-Bruinsma I, Tijhuis GJ, Boers M, Dijkmans BA, et al. Aggressive therapy in patients with early arthritis results in similar outcome compared with conventional care: the STREAM randomized trial. Rheumatology. 2012;51(4):686–94. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker355. Epub 2011/12/15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jobanputra P, Maggs F, Deeming A, Carruthers D, Rankin E, Jordan AC, et al. A randomised efficacy and discontinuation study of etanercept versus adalimumab (RED SEA) for rheumatoid arthritis: a pragmatic, unblinded, non-inferiority study of first TNF inhibitor use: outcomes over 2 years. BMJ open. 2012;2(6) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001395. Epub 2012/11/14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krieckaert CL, Jamnitski A, Nurmohamed MT, Kostense PJ, Boers M, Wolbink G. Comparison of long-term clinical outcome with etanercept treatment and adalimumab treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with respect to immunogenicity. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2012;64(12):3850–5. doi: 10.1002/art.34680. Epub 2012/08/31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schiff M, Keiserman M, Codding C, Songcharoen S, Berman A, Nayiager S, et al. Efficacy and safety of abatacept or infliximab vs placebo in ATTEST: a phase III, multi-centre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to methotrexate. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2008;67(8):1096–103. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.080002. Epub 2007/12/07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schiff M, Keiserman M, Codding C, Songcharoen S, Berman A, Nayiager S, et al. Clinical response and tolerability to abatacept in patients with rheumatoid arthritis previously treated with infliximab or abatacept: open-label extension of the ATTEST Study. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2011;70(11):2003–7. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200316. Epub 2011/09/15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weinblatt ME, Schiff M, Valente R, van der Heijde D, Citera G, Zhao C, et al. Head-to-head comparison of subcutaneous abatacept versus adalimumab for Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2012 doi: 10.1002/art.37711. Epub 2012/11/22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gabay CEP, van Vollenhoven R, Dikranian A, Alten R, Klearman M, Musselman D, Agarwal S, Green J, Kavanaugh A. Tocilizumab monotherapy is superior to adalimumab monotherapy in reducing disease activity in patients with rheumatoid arthirtis: 24-week data from the phase 4 ADACTA trial. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2012;71(Suppl 3):152. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saleem B, Keen H, Goeb V, Parmar R, Nizam S, Hensor EM, et al. Patients with RA in remission on TNF blockers: when and in whom can TNF blocker therapy be stopped? Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2010;69(9):1636–42. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.117341. Epub 2010/04/28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tanaka YHS, Fukuyo S, Nawata M, Kubo S, Yamaoka K, Saito K. Discontinuation of Adalimumab without Functional and Radiographic Damage Progression After Achieving Sustained Remission in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis (the HONOR study): 1-Year Results. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2012;64(Supplement 10):771. [Google Scholar]

- 26.van der Kooij SM, Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, de Vries-Bouwstra JK, Guler-Yuksel M, Zwinderman AH, Kerstens PJ, et al. Drug-free remission, functioning and radiographic damage after 4 years of response-driven treatment in patients with recent-onset rheumatoid arthritis. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2009;68(6):914–21. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.092254. Epub 2008/07/30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klarenbeek NB, van der Kooij SM, Guler-Yuksel M, van Groenendael JH, Han KH, Kerstens PJ, et al. Discontinuing treatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in sustained clinical remission: exploratory analyses from the BeSt study. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2011;70(2):315–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.136556. Epub 2010/11/12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kavanaugh A, Fleischmann RM, Emery P, Kupper H, Redden L, Guerette B, et al. Clinical, functional and radiographic consequences of achieving stable low disease activity and remission with adalimumab plus methotrexate or methotrexate alone in early rheumatoid arthritis: 26-week results from the randomised, controlled OPTIMA study. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2013;72(1):64–71. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201247. Epub 2012/05/09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kavanaugh AEP, Fleischmann R, van Vollenhoven RF, Pavelka K, Durez P, et al. Withdrawal of Adalimumab in Early Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients Who Attained Stable Low Disease Activity with Adalimumab Plus Methotrexate: Results of a Phase 4, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2011;63(S10):65–6. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smolen J, Ilivanova E, Hall S, Irazoque-Palazuelos F, Park MC, Kotak S, et al. Low Disease Activity or Remission Induction with Etanercept 50 Mg and Methotrexate in Moderately Active Rheumatoid Arthritis: Maintenance of Response and Safety of Etanercept 50 Mg, 25 Mg, or Placebo in Combination with Methotrexate in a Randomized Double-Blind Study. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2011;63(Suppl 10):L1. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saleem B, Brown AK, Quinn M, Karim Z, Hensor EM, Conaghan P, et al. Can flare be predicted in DMARD treated RA patients in remission, and is it important? A cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012 doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200548. Epub 2012/02/02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schiff MH, Kremer JM, Jahreis A, Vernon E, Isaacs JD, van Vollenhoven RF. Integrated safety in tocilizumab clinical trials. Arthritis research & therapy. 2011;13(5):R141. doi: 10.1186/ar3455. Epub 2011/09/03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kume K, Amano K, Yamada S, Hatta K, Ohta H, Kuwaba N. Tocilizumab monotherapy reduces arterial stiffness as effectively as etanercept or adalimumab monotherapy in rheumatoid arthritis: an open-label randomized controlled trial. The Journal of rheumatology. 2011;38(10):2169–71. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.110340. Epub 2011/08/03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shirai K, Utino J, Otsuka K, Takata M. A novel blood pressure-independent arterial wall stiffness parameter; cardio-ankle vascular index (CAVI) Journal of atherosclerosis and thrombosis. 2006;13(2):101–7. doi: 10.5551/jat.13.101. Epub 2006/05/31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilhelm B, Klein J, Friedrich C, Forst S, Pfutzner A, Kann PH, et al. Increased arterial augmentation and augmentation index as surrogate parameters for arteriosclerosis in subjects with diabetes mellitus and nondiabetic subjects with cardiovascular disease. Journal of diabetes science and technology. 2007;1(2):260–3. doi: 10.1177/193229680700100217. Epub 2007/03/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McInnes ILJ, Thompson L, Giles JT, Bathon JM, Salmon JE, Beaulieu AD, Codding CE, Delles C, Sattar N. The Effects of Tocilizumab Treatment on Lipids and Inflammatory/Prothrombotic Markers in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis: Data from the Randomised, Controlled MEASURE Study. Eropean Society of Cardiology. 2012 Epub 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hurt-Camejo E, Paredes S, Masana L, Camejo G, Sartipy P, Rosengren B, et al. Elevated levels of small, low-density lipoprotein with high affinity for arterial matrix components in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: possible contribution of phospholipase A2 to this atherogenic profile. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2001;44(12):2761–7. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200112)44:12<2761::aid-art463>3.0.co;2-5. Epub 2002/01/05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rizzo M, Spinas GA, Cesur M, Ozbalkan Z, Rini GB, Berneis K. Atherogenic lipoprotein phenotype and LDL size and subclasses in drug-naive patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Atherosclerosis. 2009;207(2):502–6. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.07.015. Epub 2009/08/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Clarke R, Peden JF, Hopewell JC, Kyriakou T, Goel A, Heath SC, et al. Genetic variants associated with Lp(a) lipoprotein level and coronary disease. The New England journal of medicine. 2009;361(26):2518–28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902604. Epub 2009/12/25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]