Abstract

Deoxynivalenol (DON), a trichothecenemycotoxin produced by Fusarium that commonly contaminates food, is capable of activating mononuclear phagocytes of the innate immune system via a process termed the ribotoxic stress response (RSR). To encapture global signaling events mediating RSR, we quantified the early temporal (≤30 min) phosphoproteome changes that occurred in RAW 264.7 murine macrophage during exposure to a toxicologically relevant concentration of DON (250 ng/mL). Large-scale phosphoproteomic analysis employing stable isotope labeling of amino acids in cell culture (SILAC) in conjunction with titanium dioxide chromatography revealed that DON significantly upregulated or downregulated phosphorylation of 188 proteins at both known and yet-to-be functionally characterized phosphosites. DON-induced RSR is extremely complex and goes far beyond its prior known capacity to inhibit translation and activate MAPKs. Transcriptional regulation was the main target during early DON-induced RSR, covering over 20 percent of the altered phosphoproteins as indicated by Gene Ontology annotation and including transcription factors/cofactors and epigenetic modulators. Other biological processes impacted included cell cycle, RNA processing, translation, ribosome biogenesis, monocyte differentiation and cytoskeleton organization. Some of these processes could be mediated by signaling networks involving MAPK-, NFκB-, AKT- and AMPK-linked pathways. Fuzzy c-means clustering revealed that DON-regulated phosphosites could be discretely classified with regard to the kinetics of phosphorylation/dephosphorylation. The cellular response networks identified provide a template for further exploration of the mechanisms of trichothecenemycotoxins and other ribotoxins, and ultimately, could contribute to improved mechanism-based human health risk assessment.

Keywords: Ribotoxic stress response, phosphorylation, quantitative proteomics, trichothecenemycotoxin, deoxynivalenol

Introduction

The trichothecenemycotoxindeoxynivalenol (DON) is a common food contaminant that targets the innate immune system and is therefore of public health significance (Pestka, 2010). DON’s immunomodulatory effects have been demonstrated in vivo in mouse systemic and mucosal immune organs (Zhou et al., 1999) as well as in primary and cloned murine monocyte/macrophage cultures derived from mice and humans (Islam et al., 2006). Most notably, DON stimulates proinflammatory gene expression at low or modest concentrations via a process known as “ribotoxic stress response” (RSR) (Iordanov et al., 1997; Laskin et al., 2002; Pestka et al., 2004). Innate immune system activation is central to both shock-like and autoimmune effects associated with acute and chronic DON exposure, respectively (Pestka, 2010).

DON-induced RSR involves the transient activation of at least two upstream ribosome-associated kinases, double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase (PKR) and hematopoietic cell kinase (HCK), which are phosphorylated within minutes of DON exposure (Zhou et al., 2003; Zhou et al., 2005b; Bae et al., 2010). Although phosphorylation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) and their substrates clearly play pivotal roles in modulating downstream events, the DON-induced RSR signaling network is not yet comprehensively understood from the perspectives of 1) identity and extent of critical proteins involved, 2) kinetics of early signaling changes and 3) early downstream events that contribute to toxic sequelae.

Resolving the complexity of DON-induced RSR requires a sensitive, integrative approach for dissecting the molecular events occurring at the cellular and subcellular level. Proteomics facilitates large-scale identification and quantification of proteins, providing information on protein expression and post-translational modification (Farley and Link, 2009; Mallick and Kuster, 2010). Proteome and phosphoproteome changes occurring after prolonged (6 h or 24 h) DON treatment have been previously measured in human B and T cell lines (Osman et al., 2010; Nogueira da Costa et al., 2011a; Nogueira da Costa et al., 2011b). While these studies are important for identification of biomarkers of effect, they are not informative from perspective of early events and signaling within the macrophage, a primary target of DON which mediates innate immune activation (Zhou et al., 2003; Pestka, 2008). Stable isotope labeling of amino acids in cell culture (SILAC) has been successfully used to characterize the signaling and subcellular compartmentalization for global delineation of macrophage behavior during phagocytosis and upon toll-like receptor stimulation (Rogers and Foster, 2007; Dhungana et al., 2009), suggesting the applicability of this strategy to the study of DON-induced RSR.

The goal of this study was to test the hypothesis that DON induces ordered phosphorylation changes in proteins in the macrophage that are associated with intracellular signaling and key biological processes that enable it to adapt and respond to RSR. Specifically, we identified and quantitated early phosphoproteomic changes induced by DON in the RAW 264.7 cells, a well-established murine macrophage model (Raschke et al., 1978; Hambleton et al., 1996) that has been used to extensively to investigate the effects of this mycotoxin on the innate immune response (Pestka, 2010). Critical features of this investigation were the use of a moderate concentration (250 ng/mL) and short time period (0 to 30 min)to mimic acute in vivo DON exposure based on the pharmacokinetic distribution and local concentration of DON in immune organs (Azcona-Olivera et al., 1995; Pestka and Amuzie, 2008). We further employed SILAC in conjunction with titanium dioxide (TiO2) chromatography and LC-MS/MS to ensure accurate quantitative phosphoproteomics(Ong et al., 2002). This large-scale phoshoproteomic analysis revealed that DON-induced RSR is extremely complex and goes far beyond its prior known capacity to activate MAPKs. These findings further provide a foundation for future exploration and elucidation of cellular response networks associated with toxicity evoked by DON and potentially other ribotoxins.

Material and methods

Experimental design

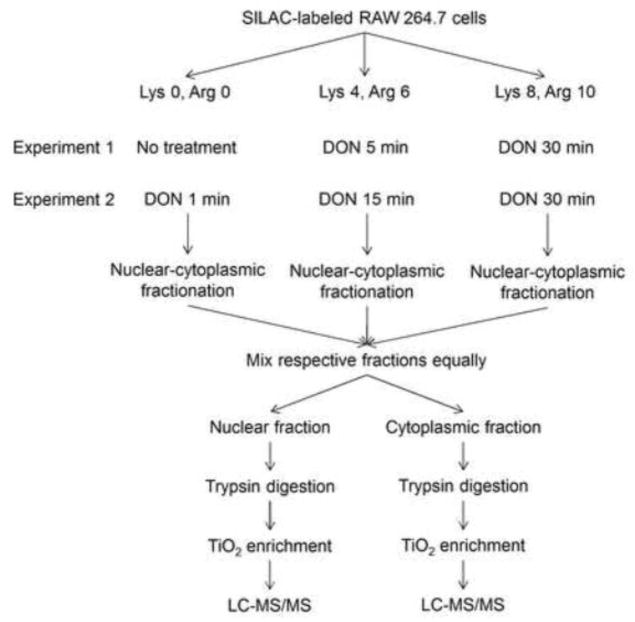

Protein phosphorylation changes during DON-induced RSR were measured in RAW 264.7 cells (American Type Tissue Collection, Rockville, MD) by a multitiered approach exploiting SILAC for quantification, TiO2 chromatography for phosphopeptide enrichment and high-accuracy mass spectrometric characterization (Olsen et al., 2006). Briefly, RAW 264.7 cells were labeled with L-arginine and L-lysine (R0K0), L-arginine-U-13C614N4 and L-lysine-2H4 (R6K4), or L-arginine-U- 13C6-15N4 and L-lysine-U-13C6-15N2 (R10K8) (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Andover, MA) (6 plates of 80% confluent cells per condition) in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, from SILAC™ Phosphoprotein ID and Quantitation Kit, Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY). Since SILAC requires sufficient proliferation for the full incorporation of labeled amino acids into the cellular proteome, metabolic labeling was performed for six cell doubling times (≈108 h). The defined mass increments introduced by SILAC among the three RAW 264.7 populations resulted in characteristic peptide triplets that enabled relative quantification of peptide abundance.

Labeled RAW 264.7 cells were treated with 250 ng/mL of DON for 0 min, 5 min, and 30 min. A second, identically labeled set of cells were treated with DON for 1 min, 15 min, and 30 min. Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were extracted using a Nuclear Extract Kit (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA). Each fraction of three treatment types were pooled equally based on protein content as determined by BCA Protein Assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL). These resultant mixtures were then subjected to phosphoproteomic analysis. Each time course set was repeated in three independent experiments (n=3) to account for biological and technical variability.

Phosphopeptide enrichment

Proteins were digested with trypsin according to the filter-aided sample preparation (FASP) protocol (Wisniewski et al., 2009) using spin ultrafiltration units of nominal molecular weight cut of 30,000 (Millipore, Billerica, MA). The peptides were desalted with 100 mg reverse-phase tC18 SepPak solid-phase extraction cartridges (Waters, Milford, MA), and enriched for phosphopeptide with Titansphere PHOS-TiO Kit (GL Sciences, Torrance, CA) following manufacturer’s instructions. Enriched peptides were desalted again prior to LC-MS/MS.

Mass spectrometry

Peptides were resuspended in 2% acetonitrile (ACN)/0.1%trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) to final concentration of 20 μg/uL. From this, 10 μL (200 μg) were automatically injected using a Waters nanoAcquity Sample Manager (www.waters.com) and loaded for 5 min onto a Waters Symmetry C18 peptide trap (5 μm, 180 μm × 20 mm) and washed at 4 μL/min with 2% ACN/0.1% Formic Acid. Bound peptides were eluted using a Waters nanoAcquity UPLC (Buffer A = 99.9% Water/0.1% Formic Acid, Buffer B = 99.9% ACN/0.1% Formic Acid) onto a Michrom MAGIC C18AQ column (3 u, 200 A, 100 U × 150 mm, www.michrom.com) and eluted over 360 min with a gradient of 2% B to 30% B in 347 min at a flow rate of 1 μl/min. Eluted peptides were sprayed into a ThermoFisher LTQ-FT Ultra mass spectrometer (www.thermo.com) using a Michrom ADVANCE nanospray source. Survey scans were taken in the FT (25000 resolution determined at m/z 400) and the top ten ions in each survey scan were then subjected to automatic low energy collision induced dissociation (CID) in the LTQ.

Data analysis

Peak list generation, protein quantitation based upon SILAC, extracted ion chromatograms (XIC) and estimation of false discovery rate (FDR) were all performed using MaxQuant(Cox and Mann, 2008), v1.2.2.5. MS/MS spectra were searched against the IPI mouse database, v3.72, appended with common environmental contaminants using the Andromeda searching algorithm (Cox et al., 2011). Further statistical analysis of the SILAC labeled protein and peptide ratio significance was performed with Perseus (www.maxquant.org). MaxQuant parameters were protein, peptide and modification site maximum FDR = 0.01; minimum number of peptides = 1; minimum peptide length = 6; minimum ratio count = 1; and protein quantitation was done using all modified and unmodified razor and unique peptides. Andromeda parameters were triplex SILAC labeling: light condition (no modification), medium condition (Arg6, Lys4), heavy condition (Arg10, Lys8); fixed modification of Carbamidomethylation (C), variable modifications of Oxidation (M), Phosphorylation (STY) and Acetyl (Protein N-term); Maximum number of modifications per peptide = 5; enzyme trypsin max missed cleavage = 2; parent Ion tolerance = 6ppm; fragment Ion tolerance = 0.6 Da and reverse database search was included. For each identified SILAC triplet, MaxQuant calculated the three extracted ion chromatogram (XIC) values, and XICs for the light and medium member of the triplet were normalized with respect to the heavy common 30 min time point of DON treatment, which was scaled to one. A significance value, Significance B, was calculated for each SILAC ratio and corrected by the method of Benjamini and Hochberg using the statistical program Perseus in the MaxQuant environment (Cox and Mann, 2008). Significance B values of a phosphopeptide in the two sets of time courses are calculated independently. Significant protein ratio cutoff was set as at least one set of time course has a Significance B value ≤0.05 as calculated by MaxQuant(Cox et al., 2009). Phosphosites were mapped with PhosphoSitePlus(Hornbeck et al., 2012).

Verification by Western analysis

Immunoblotting analysis was performed on selected proteins as described previously (Bae and Pestka, 2008) to verify phosphoproteome quantitation. Antibodies against the following proteins were used: p38, phospho-p38 MAPK (Thr180/Tyr182), p42/p44 MAP kinase, phospho-p42/p44 MAP kinase (Thr202/Tyr204), SAPK/JNK, phospho-SAPK/JNK (Thr183/Tyr185), GAPDH, stathmin (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), phospho-stathmin (Ser25, Santa Cruz, CA). Blots were scanned on the Odyssey IR imager (LICOR, Lincoln, NE) and quantification was performed using LICOR software v.3.0.

DAVID analysis

Analyses for gene ontology (GO) annotation terms were performed with the functional annotation tool DAVID (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/). Uniprot accession identifiers of significantly regulated phosphoproteins were submitted for analysis of GO biological processes and KEGG pathways, with a maximal DAVID EASE score of 0.05 for categories represented by at least two proteins.

Fuzzy c-means clustering

Patterns in the time profiles of regulated phosphopeptides, all phosphopeptides identified were sought by fuzzy c-means (FCM) clustering (Olsen et al., 2006) in MATLAB (MathWorks). To robustly represent the ratio of a peptide being quantified multiple times, the median values of the three biological replicates were used for clustering. SILAC ratios of peptides quantified over all five time points were included, natural log transformed and normalized. From the 40 stable clusters, we selected 6 representing early, intermediate and late responders with phosphorylation levels up- or down-regulated based on the average probability of each cluster.

Results and Discussion

DON-induced changes in phoshoproteomic profile

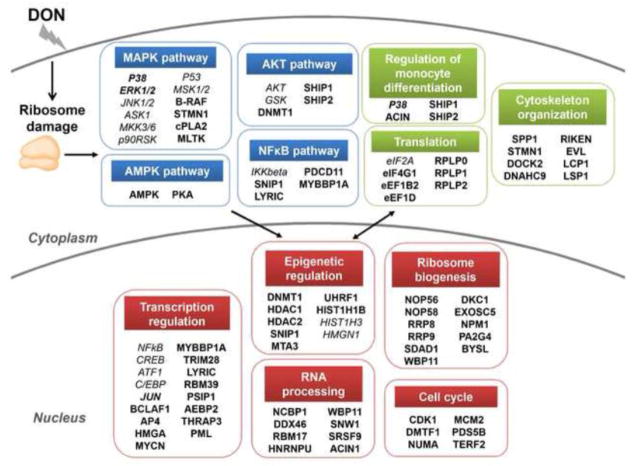

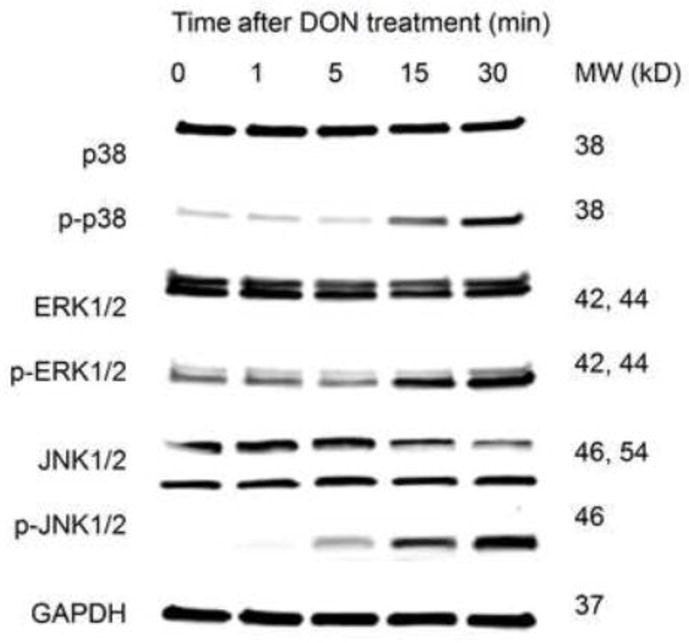

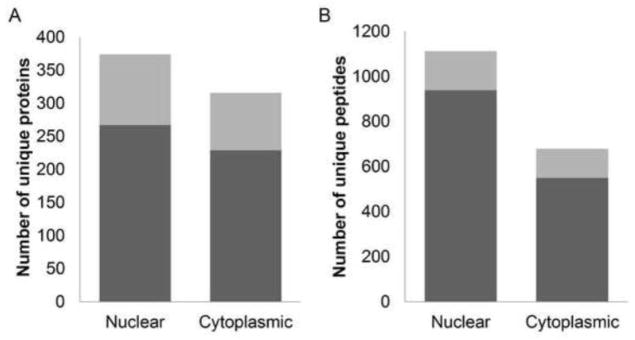

DON induced the activation p38, ERK and JNK, the marker of DON-induced RSR, in SILAC-labeled RAW 264.7 (Fig. 1) comparable to that described previously in unlabeled RAW 264.7 (Zhou et al., 2003), demonstrating the validity of this model to study RSR. Using SILAC in conjunction with TiO2 chromatography and LC-MS/MS (Fig. 2), more than 96% of identified peptides were found to harbor at least one phosphorylation residue, indicating that phosphopeptide enrichment by TiO2 was highly efficient. We reproducibly identified 1112 and 680 unique phosphopeptides corresponding to 374 and 316 proteins in the nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions, respectively, at an accepted FDR of 1% (Fig. 3). Approximately 17% of the total phosphopeptides identified were considered significant (FDR≤0.05). The distribution of phosphorylated serine, threonine, and tyrosine sites was 84%, 14% and 2%, respectively (Table 1). The affected nuclear and cytosolic phosphoproteins are listed in Supplemental Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Based on PhosphoSitePlus annotation, the extensive phosphoproteome changes occurred in the macrophage early during DON-induced RSR encompass known and yet-to-be functionally characterized phosphosites.

Fig. 1.

Western blot of p38, ERK and JNK in SILAC-labeled RAW 264.7 with total and phospho-specific antibodies. with GAPDH as internal control. The activation of MAPKs was comparable to that in unlabeled RAW 264.7 ensuring the SILAC-labeled behave similarly to their unlabeled counterparts. Results shown are representative of 3 replicate experiments.

Fig. 2.

Experimental design for SILAC-based quantitative phosphoproteomic analysis of DON-induced RSR. RAW 264.7 cultured in media supplemented with normal lysine and arginine (Lys0, Arg0), medium-labeled lysine and arginine (Lys4, Arg6), and heavy-labeled lysine and arginine (Lys8, Arg10) were subjected different DON treatments in two sets of experiments. Nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins were extracted, mixed equally among different groups based on protein amount and trypsin digested. Phosphopeptides were enriched by titanium dioxide chromatography and analyzed by high-resolution mass spectrometry. Each set was repeated in three independent experiments (n=3).

Fig. 3.

DON-induced RSR involves extensive protein phosphorylation changes. The numbers of significantly regulated (grey) phosphorylated proteins (A) and peptides (B) as determined by Significance B corrected for FDR≤0.05 among all unique proteins and peptides identified (grey + black).

Table 1.

Distribution of phospho-serine, threonine and tyrosine identified in RAW 264.7 cells

| Nuclear | Cytoplasmic | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Site | Number all | Percent all | Number significant | Percent significant | Number all | Percent all | Number significant | Percent significant |

| pSer | 921 | 83.8% | 160 | 86.5% | 505 | 83.2% | 114 | 87.0% |

| pThr | 158 | 14.4% | 25 | 13.5% | 88 | 14.5% | 12 | 9.2% |

| pTyr | 20 | 1.8% | 0 | 0.0% | 14 | 2.3% | 5 | 3.8% |

Confirmation of proteomic results

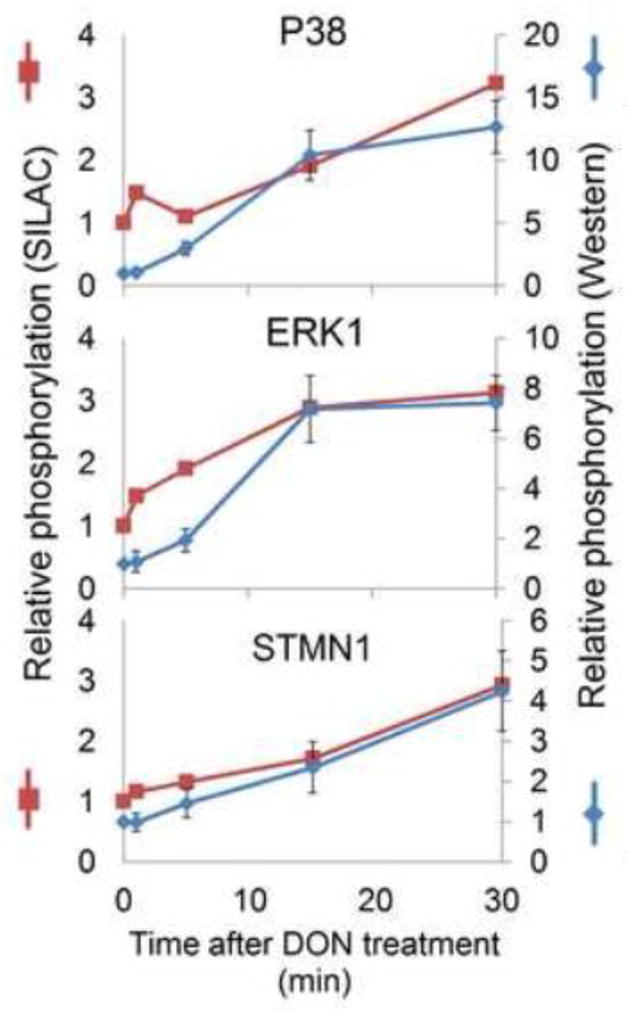

To verify the quantification of phosphorylation in SILAC-based proteomics, the phosphorylation kinetics of three representative proteins, p38, ERK1 and STMN1, were measured by Western blotting using phosphosite-specific antibodies. SILAC- and immunoblot-based relative quantifications were in agreement (Fig. 4), indicating the SILAC method to be a viable approach to study the dynamic effects of DON-induced RSR.

Fig. 4.

Confirmation of phosphoproteome quantification. Phosphorylation levels were measured using Western blot by normalizing the signaling intensity of the bands from phosphosite-specific antibody with those from total antibody. Normalized intensities (blue, shown as mean± SEM) were then correlated with the SILAC ratios (red, shown as median).

Biological analysis of altered phosphoproteins

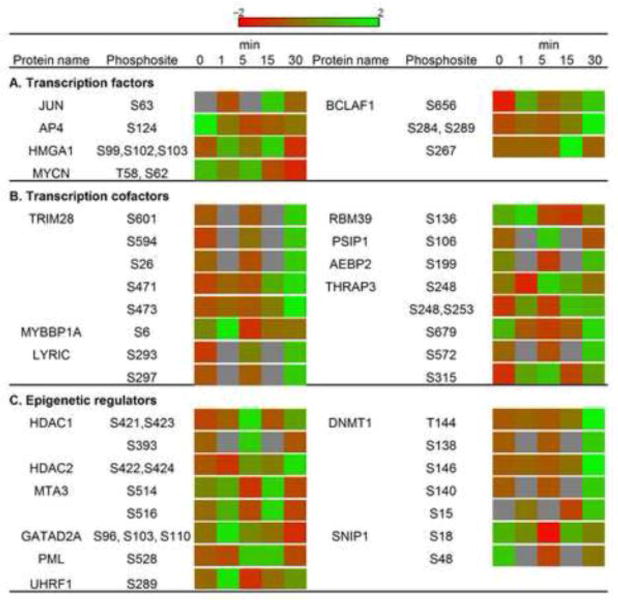

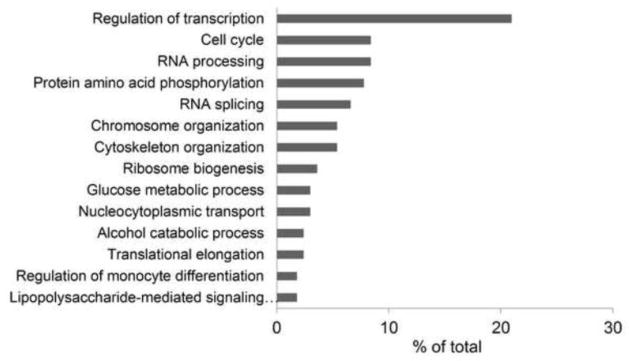

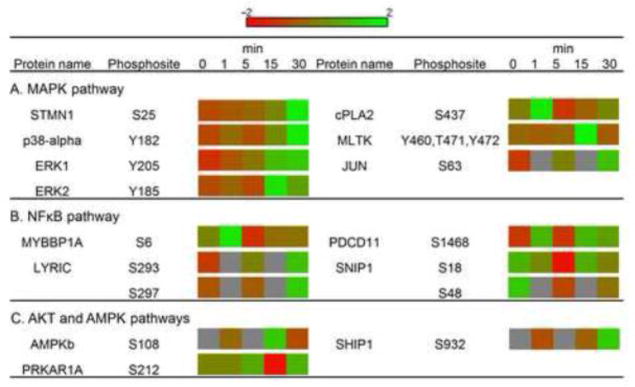

To discern the potential impact of DON-induced phosphorylation, changes prevalence of differentially phosphorylated proteins were related to specific biological processes using GO annotation in DAVID (Fig. 5). The process most affected during DON-induced RSR was regulation of transcription, which constituted more than 20 percent of all significantly regulated phosphoproteins and included transcription factors (Fig. 6A), cofactors (Fig. 6B), and epigenetic modulators (Fig. 6C). Functional annotation further indicated that phosphoproteins affected during DON-induced RSR might impact other biological processes including cell cycle, RNA processing, translation, ribosome biogenesis, monocyte differentiation and cytoskeleton organization. For example, cyclin-dependent kinase 1/2 (CDK1/2) dephosphorylation (Thr14), which promotes G2/M transition (Mayya et al., 2006), was observed at 15 min. Also, modulation of translation (eIF4G1, eEF1B and eEF1D) might influence protein expression during DON-induced RSR. Finally, ribosomal RNA-processing protein 8 and 9 (RRP8 and RRP9), nucleophosmin (NPM1) and other proteins that function in the ribosome biogenesis were also differentially phosphorylated, suggesting that fine-tuning of translation likely occurs in early DON-induced RSR before onset of large-scale translation inhibition. Concomitant with impacting transcriptional and other processes, DON altered the phosphorylation of proteins mediating MAPK (Fig. 7A), NFκB (Fig. 7B), and AKT/AMPK (Fig. 7C) signaling, suggesting likely roles for these master regulators.

Fig. 5.

Gene Ontology associated with significantly regulated phosphoproteins as determined by DAVID Biological Process terms (DAVID EASE score < 0.05). Data are presented as a histogram of the relevant biological processes identified and shown as a percentage of the total identified proteins that fall within each category.

Fig. 6.

Phosphorylation changes of transcription factors (A), cofactors (B), and epigenetic regulators (C) during DON-induced RSR. The heat map depicts the log 2 transformed relative abundance (red to green) of the protein phosphorylation.

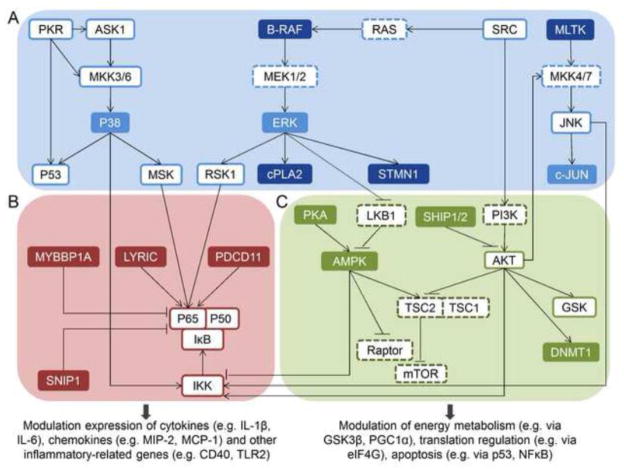

Fig. 7.

Phosphorylation changes of proteins involved in the MAPK (A), NFκB (B), AKT and AMPK pathways (C) during DON-induced RSR. The heat map depicts the log 2 transformed relative abundance (red to green) of the protein phosphorylation.

Integration of phosphoproteomic data with prior studies - transcriptional regulation

The extent of gene expression generally reflects the availability of mRNA for translation through modulation of transcription and mRNA stability. Prolonged exposure to DON has been previously shown to activate transcription factors (e.g., c-JUN, NF-κB, CREB, AP-1 and C/EBP) in RAW 264.7 at 2 hr(Wong et al., 2002). Consistent with these findings, we confirmed c-JUN phosphorylation at Ser63, and further identified phosphorylation sites on other transcription factors not previously known to be modulated by DON (Fig. 6A). For example, n-MYC (V-mycmyelocytomatosis viral related oncogene, neuroblastoma derived, MYCN) targets and enhances the expression of genes functioning in ribosome biogenesis and protein synthesis, and thus modulates the abundance of the translation machinery (Boon et al., 2001). Since n-MYC also regulates global chromatin structure (Murphy et al., 2009), modification of its phosphorylation might simultaneously function in epigenetic regulation.

Transcription cofactors were similarly impacted during DON-induced RSR (Fig. 6B). For example, MYBBP1A, found to be rapidly dephosphorylated at 30 min, is known to interact with and activate several transcription factors such as c-JUN, while repressing others such as PPARγ co-activator 1α (PGC-1α), NFκB, and c-MYB (Fan et al., 2004; Owen et al., 2007; Yamauchi et al., 2008). This protein was reported to be upregulated at the protein level by DON (150 ng/mL) at 6 h in a prior proteomic study in EL4 mouse thymoma cells (Osman et al., 2010). Another interacting protein and repressor of c-MYB, tripartite motif protein 28 (TRIM28), was altered via phosphorylation. TRIM28 is a universal co-repressor that induces cell differentiation in the monocytic cell line U937 via its interaction and activation of C/EBP beta (Rooney and Calame, 2001), a transcription factor also activated by DON (Wong et al., 2002). Overall, phosphorylation alterations of these two MYB-binding proteins as observed in our analysis suggest that MYB transcription factor complex could be a possible hub for transcriptional regulation during DON-induced RSR.

DON might also affect gene expression via epigenetic processes (Fig. 6C). Altered phosphoproteins included histone deacetylases 1 and 2 (HDAC1 and HDAC2), GATA zinc finger domain-containing protein 2A (GATAD2A), metastasis-associated protein 3 (MTA3) - all four proteins function as core components of the nucleosome remodeling and deacetylase (NuRD) complex, an ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling entity (Lai and Wade, 2011). Phosphorylation at Ser421 and Ser423 (significantly regulated by DON) of HDAC1 promotes enzymatic activity and interactions with the NuRD complex (Pflum et al., 2001). Similarly, HDAC2 interaction with co-repressor proteins and transcription factors is further dependent on phosphorylation at Ser422 and Ser424 (also significantly regulated by DON) (Adenuga and Rahman, 2010). Phosphorylation changes of HDAC1 and HDAC2 at these sites could impact NuRD assembly and enzymatic activity (Adenuga and Rahman, 2010) and further modulate gene expression (Kurdistani et al., 2004). Another phosphoprotein altered by DON treatment, promyelocyticleukaemia (PML), is part of an oncogenic transcription factor that recruits the NuRD complex to target genes through direct protein interaction (Lai and Wade, 2011). Thus, DON impacted several critical regulators of chromatin remodeling.

Besides nucleosome remodeling, DON also altered phosphorylation status of key regulators in DNA methylation and microRNA biogenesis (Fig. 6C). Most notably, differential phosphorylation of DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) at multiple sites that dictate its DNA-binding activity (Sugiyama et al., 2010; Esteve et al., 2011)was identified. Also affected was SNIP1, which interacts with Drosha and is involved in the biogenesis of miRNAs(Yu et al., 2008). Consistent with this observation, DON has been shown to alter miRNA profile in RAW 264.7 (He and Pestka, 2010). We further identified other mediators of epigenetic regulation. Ubiquitin-like, containing PHD and RING finger domains 1 (UHRF1) recruits DNMT1 to hemi-methylated DNA (Sharif et al., 2007) and binds to the tail of histone H3 in a methylation sensitive manner, bridging DNA methylation and histone modification (Sharif et al., 2007). Besides being a transcriptional co-repressor, the aforementioned TRIM28 is recruited to DNA and subsequently initiates epigenetic silencing by recruiting histone deacetylase, histone methyltransferase, and heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1) family members (Ellis et al., 2007). This process could be inhibited by phosphorylation of TRIM28 at Ser473(Hu et al., 2012).

Although the potential for DON to evoke epigenetic effects has been indicated previously in a human intestinal cell line in which DON treatment increased overall genomic DNA methylation (Kouadio et al., 2007), the mechanisms for such effects were not understood. Our analysis provides a plausible explanation as evidenced by altered phosphorylation of DNA methyltransferase DNMT1 at phosphosites important for regulating its activity, and reveals further possible epigenetic effects linked to DON-induced RSR such as nucleosome remodeling and miRNA biogenesis. Effects on nucleosome remodeling by macrophage-stimulating non-ribotoxic agents have been reported previously. For example, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) induces NuRD component MTA1 depletion (Pakala et al., 2010) and selective recruitment of Mi-2β-containing NuRD complex (Ramirez-Carrozzi et al., 2006). However, post-translational modification across multiple components of the NuRD complex as shown here is novel suggesting that these latter epigenetic effects might be a specific ribotoxin-linked response. Additional studies are needed to elucidate how epigenetic regulation coordinates the balance between induction of stress related proteins and the global system shutdown during RSR caused by DON.

Consistent with our findings, DON has previously been shown to alter RNA processing, as well as ribosome structure and function, during prolonged RSR in human lymphoid cells (Katika et al., 2012), Accordingly, fine-tuning of the transcriptional activity during early DON-induced RSR is a hallmark of cells in responding to the stress, with concurrent translational activity as an assisting measure. If stress persists, such balance likely shifts towards regulation of translation for systematic shutdown, via mechanisms such as phosphorylation of eIF2α, damage of the peptidyltransferase center and cleavage of rRNA(Pestka, 2010).

Integration of phosphoproteomic data with prior studies - kinase signaling

DON appears to broadly impact kinase signaling pathways (Fig. 7, 8). Activation of MAPK cascades is considered a central feature of RSR (Iordanov et al., 1997), and indeed, we were recapitulatednot only the activation of p38, ERK, and c-JUN, but, in addition, identified other potential mediators upstream and downstream to MAPK (Fig. 7A, 8A). These included B-RAF which activates ERK via MEK1/2 directing cell proliferation, as well as MLK-like mitogen-activated protein triple kinase (MLTK) which can activate JNK-mediated pathway regulating actin organization, and has been shown to be an upstream MAP3K in stress induced by the ribotoxinsanisomycin, ricin and Shiga toxin (Gotoh et al., 2001; Jandhyala et al., 2008).

Fig. 8.

Signaling pathways mediating DON-induced RSR, including the MAPK (A, blue), NFκB (B, red), AKT and AMPK pathways (C, green). Dark-filled boxes indicate novel mediators based on this study, light-filled boxes indicate known mediators identified here, open boxes with solid outline indicate known mediators not identified here, and open boxes with dashed outline indicate known mediators in canonical pathway and not identified here.

Potential downstream effectors of the activated MAPKs were also identified that are capable of modulating both cell structure and function during DON-induced RSR. One of these, stathmin (STMN1), is a small binding protein that regulates the rates of microtubules polymerization and disassembly. ERK-driven phosphorylation of STMN1 at four serine residues including Ser25 (also significantly regulated by DON) leads to cell cycle arrest and apoptosis (Nakamura et al., 2006). Another was cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2), the phosphorylation of which is required for the release of arachidonic acid, and has been implicated in the initiation of inflammatory responses (Pavicevic et al., 2008). Activation of cPLA2 could set the stage for the later prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) production catalyzed by cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), which is consistent with previous observations in DON-treated cells and animals (Moon and Pestka, 2002). Accordingly, these phosphoproteome data provide new insights into precursor events and functional consequences of MAPK pathways during DON-induced RSR.

Among other proteins identified, metadherin (LYRIC), programmed cell death protein 11(PDCD11) and p38 are responsible for positive regulation of the I-kappaB kinase/NF-kappaB(IKK/NFκB) cascade (Saccani et al., 2002; Sweet et al., 2003; Emdad et al., 2006) (Fig. 7B, 8B). Furthermore, Smad nuclear interacting protein (SNIP1) and Myb-binding protein 1A (MYBBP1A) function as repressors of NF-κB signaling pathway by competing with the NFκB transcription factor p65/RelA for binding to the transcriptional coactivator p300 (Kim et al., 2001; Owen et al., 2007). Collectively these data suggest that the NFκB pathway might be crucial to transcription regulation in DON-induced RSR. Importantly, functions of some phosphosites identified here have not been previously reported, suggesting the need for extended investigation of NFκB function in DON toxicity.

AKT- and AMPK-related pathways are also likely impacted during DON-induced RSR (Fig. 7C, 8C). AKT, an AGC kinase known to be activated in response to DON starting at 15 min (Zhou et al., 2005a), indirectly activates mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) by phosphorylation and inhibition of the tumor suppressor TSC2 which heterodimerizes with TSC1 (Memmott and Dennis, 2009). Interestingly, modulated phosphorylation of 5′-phosphatase SH2-containing inositol-5′-phosphatase (SHIP) was observed. SHIP regulates intracellular levels of phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate (PIP3), an important second messenger necessary for AKT activation (Rauh et al., 2004). In addition to the potential positive regulation of the mTOR pathway via AKT, we detected AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK). AMPK at Ser108 at 15 min followed by rapid and robust phosphorylation dephosphorylation at 30 min. AMPK inhibits the mTOR pathway directly through phosphorylation of Raptor or indirectly through phosphorylation and activation of TSC2 (Memmott and Dennis, 2009). Autophosphorylation of AMPK at this site is associated with increased phosphorylation at Thr172 and increased AMPK activity (Sanders et al., 2007). This latter site can be phosphorylated by liver kinase B1 (LKB1) (Yang et al., 2010), the activity of which could be dampened via phosphorylation by ERK1. Interestingly, AMPK phosphorylation at Thr172, which boosts energy-producing catabolic processes in the cell (Schultze et al., 2012), can be impeded by PKA, also significantly affected by DON, by inducing AMPK phosphorylation at another site (Ser173) (Djouder et al., 2010). Overall, these results suggest that extensive crosstalk is likely among AKT, AMPK and MAPK pathways while mediating DON-induced RSR (Zheng et al., 2009).

Modulation of signaling within pathways involving MAPK, NF-κB, AKT and AMPK could enable cells to prepare for subsequent onset of proinflammatory gene expression and maintain an appropriate level of stress-related proteins during the ensuing response. In macrophages, AKT and AMPK have proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory effects, respectively, both of which are modulated via IKK in the NFκB pathway (Murakami and Ohigashi, 2006; Rajaram et al., 2006; Sag et al., 2008). As observed in LPS-treated macrophages (Kim et al.), AMPK is dephosphorylated and AKT is phosphorylated in DON-treated RAW 264.7 prior to the release of proinflammatory mediators. Modulation of the NFκB pathway could regulate the expression of cytokines (e.g. IL-1β, IL-6), chemokines (e.g. MIP-2, MCP-1) and other inflammatory-related genes that are reported to be regulated on the transcription level (e.g. CD40, TLR2) (Kinser et al., 2005; He et al., 2012). The AKT and AMPK pathways also converge and regulate the activity of mTOR pathway that controls translation via p70S6K and eIF4E, with the latter also being modulated by MAPK. As has been reported for another ribotoxin Shiga toxin 1 (Cherla et al., 2006), DON-induced expression of inflammatory proteins might reflect in part the rapid onset of translation initiation following eIF4E phosphorylation (He et al., 2012).

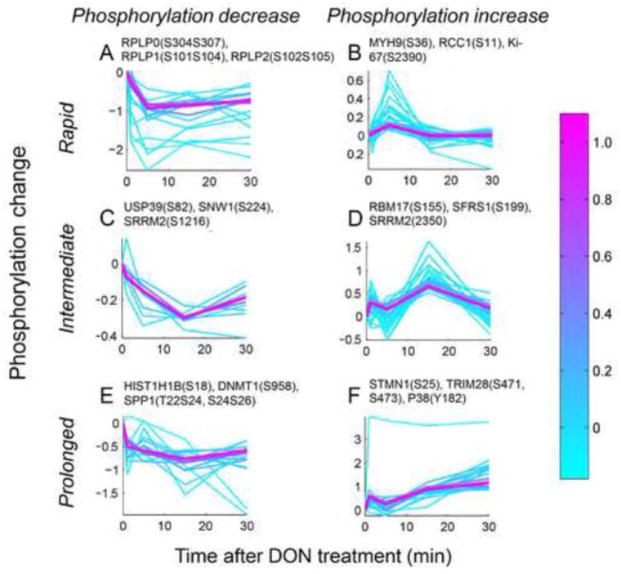

Categorization of DON-regulated phosphopeptides into distinct temporal profiles

Fuzzy c-means clustering analysis was utilized to trace the temporal changes of protein phosphorylation observed. Based on the pattern of phosphorylation changes and the average probability of the clusters, six distinctive temporal profiles (rapid, intermediate, prolonged) of the regulated (phosphorylated, dephosphorylated) phosphopeptides were recognized (Fig. 9A–F). DON-induced RSR initiated with rapid (≤ 5 min) dephosphorylation of ribosomal proteins (e.g. RPLP0, RPLP1, RPLP2) (Fig. 9A), and phosphorylation of cell cycle proteins (e.g. MYH9, RCC1, Ki-67) (Fig. 9B). The stress response proceeded with a cascade of phosphorylation events involving proteins in RNA splicing (e.g. USP39, SNW1, SRRM2, RBM17, SFRS1) (Fig. 9C, 9D) up to approximately 15 min. Such proteins function in both constitutive pre-mRNA splicing and alternative splicing, suggesting the possible involvement of RNA splicing during DON-induced RSR, which could be important to modulating gene expression in the recovery of stressed cells (Biamonti and Caceres, 2009). As RSR progressed, prolonged dephosphorylation of epigenetic regulators (e.g. HIST1H1B, DNMT1) occurred which could further fine-tune gene expression (Fig. 9E) whereas prolonged phosphorylation of cytoskeleton proteins (e.g. STMN1) was evident, possibly affecting cell morphology, motility, and trafficking to adapt to ribotoxic stress posed by DON (Fig. 9F).

Fig. 9.

DON-regulated phosphosites can be categorized into several temporal profiles. Based on the phosphorylation dynamics, Fuzzy c-means clustering analysis generated clusters representing early, intermediate and late responders with phosphorylation levels up- or down-regulated were selected from 40 stable clusters based on the average probability (A–F). Each trace depicts the natural log value of relative phosphorylation level as a function of time, and is color coded according to its membership value (i.e. the probabilities that a profile belongs to different clusters) for the respective cluster. Each cluster is designated by the function of prominent members. Examples of such members are given for each cluster.

Limitations of phosphoproteomic approach

It is critical to note that the phosphorylation changes observed here likely represent the most abundant phosphoproteins - a general characteristic of proteomics (Pandey and Mann, 2000). In addition, this study focuses on a time window representing acute DON exposure (0–30 min), while many studies addressing protein phosphorylation of signaling molecules and transcription factors targeted employed longer exposure periods(2–6 hr) (Wong et al., 2002; Zhou et al., 2005a). As a result, it is not surprising that some of the phosphorylation targets that have been previously demonstrated immunochemically to be linked to DON-induced RSR, such as JNK and AKT, were not detected in our phosphoproteomic analysis. As demonstrated here, it was thus necessary to meld large-scale phosphoproteomic data with that of focused small-scale studies to comprehensively understand the molecular mechanisms of a complicated response such as DON-induced RSR.

It should also be emphasized that some of the phosphorylation sites affected here have not been previously reported in the literature, and the precise effects of these phosphosites on cell function are not understood. Phosphorylation of a protein could theoretically lead to activation or inhibition of its activity, altered protein-protein interaction, or degradation by the ATP-dependent ubiquitin/proteasome pathway (Jung and Jung, 2009). Thus further elucidation how DON-modulated phosphorylation patterns alter cell functions is necessary. This would involve characterization of how mutations of the phosphosite to another amino acid genetically would impact enzymatic activity or cell physiology and organization, which exceeds the scope of the present study. Nevertheless phosphoproteomic analysis serves as a hypothesis-generating tool and inventories proteins with changed phosphorylation status for future focused studies.

Conclusion

The global, quantitative and kinetic analysis of the early phosphoproteome changes described here demonstrates that DON-induced RSR is extremely complex and goes far beyond the simple capacity to activate the MAPK pathway and inhibit translation for which it has been long-recognized. These findings provide new insights into the processes by which DON impacts intracellular signaling and aberrantly modulate critical cell processes in a well-established macrophage model with high relevance to innate immune system activation in vivo. Given that a single regulatory protein can be targeted by many protein kinases and phosphatases, phosphorylation is critical to effectively integrating information carried by multiple signal pathways, thus providing opportunities for great versatility and flexibility in regulation (Jackson, 1992). As summarized in Fig. 10, in response the ribosome damage caused by ribotoxic stressors, signaling pathways including MAPK, NFκB, AKT and AMPK pathways are activated which mediate key biological processes in the cytoplasm and the nucleus to adapt and respond to RSR.

Fig. 10.

Summary of pathways and biological processes involved in DON-induced RSR. In response the ribosome damage caused by ribotoxic stressors, signaling pathways including MAPK, NFκB, AKT and AMPK pathways are activated which mediate key biological processes in the cytoplasm and the nucleus to adapt and respond to RSR. Proteins in bold indicate novel mediators identified in the present study, proteins in bold and italics indicate previously known mediators confirmed here, and proteins in italics indicate previously known mediators but not identified here.

Taken together, the phosphoproteome changes observed here suggest DON-induced RSR entails 1) a complex signaling network involving the MAPK, NF-κB, AKT and AMPK pathways; 2) delicate balance between stress response and quiescence achieved by transcription regulation via transcription factors/cofactors and epigenetic modulators as the main strategy, and 3) translation regulation by modulating of translation and ribosome biogenesis processes coordinating with it. These data provide a foundation for future exploration of phosphoprotein functions in DON-induced RSR. Elucidation of cellular-response networks on the basis of large-scale proteomic analyses such as that observed here will enhance mechanistic understanding of toxicity pathways leading to the adverse effects of DON and other ribotoxic stressors that is a prerequisite for human health risk assessment within the “toxicity testing in the 21st century” paradigm (Andersen and Krewski, 2009). Given that the DON concentration used here is toxicologically relevant, mechanistic understanding of DON-induced RSR derived from this in vitro mouse macrophage cell model should have value for prediction of the molecular events taking place in vivo. Therefore this study could ultimately contribute to designing strategies for the treatment and prevention of the adverse effects of DON and other ribotoxic stressors.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Mycotoxin deoxynivalenol (DON) induces immunotoxicity via ribotoxic stress response

SILAC phosphoproteomics using TiO2 was applied to DON-treated RAW 264.7 cells

DON induces extensive protein phosphorylation changes involving 188 phosphoproteins

The main target of early DON-induced RSR is transcriptional regulation

Early DON-induced RSR is mediated by MAPK-, NFκB-, AKT- and AMPK-linked pathways

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health (PHS grant ES003358). We thank Drs. Gavin Reid, Brad Upham and PavelBabica for their support in formulating the experiment procedure, Dr. Hui-Ren Zhou, Elizabeth Vickers and Saunia Withers for their technical assistance, and Mary Rosner, Melissa Bates and Brenna Flannery for proofreading the manuscript.

Footnotes

List of nuclear (Supplementary Table 1) and cytoplasmic (Supplementary Table 2) proteins with significantly altered phosphorylation status, and details of fuzzy c-means clustering (Supplementary Dataset 1) and excel spreadsheets of original data for all and Significant changed phosphopeptides (Supplementary Dataset 2) were included. Raw data have been uploaded into the publicly available database Tranche, https://proteomecommons.org/ (Accession: All MS raw files can be accessed using the hash code DqYeTfyZRDlnE67PJ+fDl/Fz+6lmPNZl7Gc72M9bBw00/qrVHB3wEB7+g8O4dknaa0UXPjCQST lVPi0DG2ikqFG3zJEAAAAAAAAPPQ==

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adenuga D, Rahman I. Protein kinase CK2-mediated phosphorylation of HDAC2 regulates co-repressor formation, deacetylase activity and acetylation of HDAC2 by cigarette smoke and aldehydes. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics. 2010;498:62–73. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen ME, Krewski D. Toxicity testing in the 21st century: bringing the vision to life. Toxicol Sci. 2009;107:324–330. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azcona-Olivera JI, Ouyang Y, Murtha J, Chu FS, Pestka JJ. Induction of cytokine mRNAs in mice after oral exposure to the trichothecene vomitoxin (deoxynivalenol): relationship to toxin distribution and protein synthesis inhibition. Toxicology and applied pharmacology. 1995;133:109–120. doi: 10.1006/taap.1995.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae H, Gray JS, Li M, Vines L, Kim J, Pestka JJ. Hematopoietic cell kinase associates with the 40S ribosomal subunit and mediates the ribotoxic stress response to deoxynivalenol in mononuclear phagocytes. Toxicol Sci. 2010;115:444–452. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfq055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae HK, Pestka JJ. Deoxynivalenol induces p38 interaction with the ribosome in monocytes and macrophages. Toxicol Sci. 2008;105:59–66. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biamonti G, Caceres JF. Cellular stress and RNA splicing. Trends in biochemical sciences. 2009;34:146–153. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boon K, Caron HN, van Asperen R, Valentijn L, Hermus MC, van Sluis P, Roobeek I, Weis I, Voute PA, Schwab M, Versteeg R. N-myc enhances the expression of a large set of genes functioning in ribosome biogenesis and protein synthesis. The EMBO journal. 2001;20:1383–1393. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.6.1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherla RP, Lee SY, Mees PL, Tesh VL. Shiga toxin 1-induced cytokine production is mediated by MAP kinase pathways and translation initiation factor eIF4E in the macrophage-like THP-1 cell line. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2006;79:397–407. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0605313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox J, Mann M. MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nature biotechnology. 2008;26:1367–1372. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox J, Matic I, Hilger M, Nagaraj N, Selbach M, Olsen JV, Mann M. A practical guide to the MaxQuant computational platform for SILAC-based quantitative proteomics. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:698–705. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox J, Neuhauser N, Michalski A, Scheltema RA, Olsen JV, Mann M. Andromeda: a peptide search engine integrated into the MaxQuant environment. Journal of proteome research. 2011;10:1794–1805. doi: 10.1021/pr101065j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhungana S, Merrick BA, Tomer KB, Fessler MB. Quantitative proteomics analysis of macrophage rafts reveals compartmentalized activation of the proteasome and of proteasome-mediated ERK activation in response to lipopolysaccharide. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8:201–213. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800286-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djouder N, Tuerk RD, Suter M, Salvioni P, Thali RF, Scholz R, Vaahtomeri K, Auchli Y, Rechsteiner H, Brunisholz RA, Viollet B, Makela TP, Wallimann T, Neumann D, Krek W. PKA phosphorylates and inactivates AMPKalpha to promote efficient lipolysis. The EMBO journal. 2010;29:469–481. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis J, Hotta A, Rastegar M. Retrovirus silencing by an epigenetic TRIM. Cell. 2007;131:13–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emdad L, Sarkar D, Su ZZ, Randolph A, Boukerche H, Valerie K, Fisher PB. Activation of the nuclear factor kappaB pathway by astrocyte elevated gene-1: implications for tumor progression and metastasis. Cancer research. 2006;66:1509–1516. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteve PO, Chang Y, Samaranayake M, Upadhyay AK, Horton JR, Feehery GR, Cheng X, Pradhan S. A methylation and phosphorylation switch between an adjacent lysine and serine determines human DNMT1 stability. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2011;18:42–48. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan M, Rhee J, St-Pierre J, Handschin C, Puigserver P, Lin J, Jaeger S, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Spiegelman BM. Suppression of mitochondrial respiration through recruitment of p160 myb binding protein to PGC-1alpha: modulation by p38 MAPK. Genes & development. 2004;18:278–289. doi: 10.1101/gad.1152204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farley AR, Link AJ. Identification and quantification of protein posttranslational modifications. Methods in enzymology. 2009;463:725–763. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)63040-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotoh I, Adachi M, Nishida E. Identification and characterization of a novel MAP kinase kinase kinase, MLTK. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:4276–4286. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008595200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hambleton J, Weinstein SL, Lem L, DeFranco AL. Activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase in bacterial lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophages. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93:2774–2778. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.2774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He K, Pan X, Zhou HR, Pestka J. Modulation of Inflammatory Gene Expression by the Ribotoxin Deoxynivalenol Involves Coordinate Regulation of the Transcriptome and Translatome. Toxicol Sci. 2012 doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfs266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He K, Pestka JJ. Deoxynivalenol-induced modulation of microRNA expression in RAW 264.7 macrophages-A potential novel mechanism for translational inhibition. The Toxicologist (Toxicol Sci) 2010;114(Suppl):310. [Google Scholar]

- Hornbeck PV, Kornhauser JM, Tkachev S, Zhang B, Skrzypek E, Murray B, Latham V, Sullivan M. PhosphoSitePlus: a comprehensive resource for investigating the structure and function of experimentally determined post-translational modifications in man and mouse. Nucleic acids research. 2012;40:D261–270. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu C, Zhang S, Gao X, Gao X, Xu X, Lv Y, Zhang Y, Zhu Z, Zhang C, Li Q, Wong J, Cui Y, Zhang W, Ma L, Wang C. Roles of Kruppel-associated Box (KRAB)-associated Co-repressor KAP1 Ser-473 Phosphorylation in DNA Damage Response. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2012;287:18937–18952. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.313262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iordanov MS, Pribnow D, Magun JL, Dinh TH, Pearson JA, Chen SL, Magun BE. Ribotoxic stress response: activation of the stress-activated protein kinase JNK1 by inhibitors of the peptidyl transferase reaction and by sequence-specific RNA damage to the alpha-sarcin/ricin loop in the 28S rRNA. Molecular and cellular biology. 1997;17:3373–3381. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.6.3373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam Z, Gray JS, Pestka JJ. p38 Mitogen-activated protein kinase mediates IL-8 induction by the ribotoxin deoxynivalenol in human monocytes. Toxicology and applied pharmacology. 2006;213:235–244. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson SP. Regulating transcription factor activity by phosphorylation. Trends in cell biology. 1992;2:104–108. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(92)90014-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jandhyala DM, Ahluwalia A, Obrig T, Thorpe CM. ZAK: a MAP3Kinase that transduces Shiga toxin- and ricin-induced proinflammatory cytokine expression. Cellular microbiology. 2008;10:1468–1477. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung K, Jung H. A new mechanism of phosphoregulation in signal transduction pathways. Science signaling. 2009;2:pe71. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.296pe71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katika MR, Hendriksen PJ, Shao J, van Loveren H, Peijnenburg A. Transcriptome analysis of the human T lymphocyte cell line Jurkat and human peripheral blood mononuclear cells exposed to deoxynivalenol (DON): New mechanistic insights. Toxicology and applied pharmacology. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2012.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim RH, Flanders KC, Birkey Reffey S, Anderson LA, Duckett CS, Perkins ND, Roberts AB. SNIP1 inhibits NF-kappa B signaling by competing for its binding to the C/H1 domain of CBP/p300 transcriptional co-activators. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:46297–46304. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103819200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinser S, Li M, Jia Q, Pestka JJ. Truncated deoxynivalenol-induced splenic immediate early gene response in mice consuming (n-3) polyunsaturated fatty acids. The Journal of nutritional biochemistry. 2005;16:88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouadio JH, Dano SD, Moukha S, Mobio TA, Creppy EE. Effects of combinations of Fusarium mycotoxins on the inhibition of macromolecular synthesis, malondialdehyde levels, DNA methylation and fragmentation, and viability in Caco-2 cells. Toxicon. 2007;49:306–317. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2006.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurdistani SK, Tavazoie S, Grunstein M. Mapping global histone acetylation patterns to gene expression. Cell. 2004;117:721–733. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai AY, Wade PA. Cancer biology and NuRD: a multifaceted chromatin remodelling complex. Nature reviews. 2011;11:588–596. doi: 10.1038/nrc3091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskin JD, Heck DE, Laskin DL. The ribotoxic stress response as a potential mechanism for MAP kinase activation in xenobiotic toxicity. Toxicol Sci. 2002;69:289–291. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/69.2.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallick P, Kuster B. Proteomics: a pragmatic perspective. Nature biotechnology. 2010;28:695–709. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayya V, Rezual K, Wu L, Fong MB, Han DK. Absolute quantification of multisite phosphorylation by selective reaction monitoring mass spectrometry: determination of inhibitory phosphorylation status of cyclin-dependent kinases. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:1146–1157. doi: 10.1074/mcp.T500029-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Memmott RM, Dennis PA. Akt-dependent and -independent mechanisms of mTOR regulation in cancer. Cellular signalling. 2009;21:656–664. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon Y, Pestka JJ. Vomitoxin-induced cyclooxygenase-2 gene expression in macrophages mediated by activation of ERK and p38 but not JNK mitogen-activated protein kinases. Toxicol Sci. 2002;69:373–382. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/69.2.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami A, Ohigashi H. Cancer-preventive anti-oxidants that attenuate free radical generation by inflammatory cells. Biological chemistry. 2006;387:387–392. doi: 10.1515/BC.2006.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy DM, Buckley PG, Bryan K, Das S, Alcock L, Foley NH, Prenter S, Bray I, Watters KM, Higgins D, Stallings RL. Global MYCN transcription factor binding analysis in neuroblastoma reveals association with distinct E-box motifs and regions of DNA hypermethylation. PloS one. 2009;4:e8154. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura K, Zhang X, Kuramitsu Y, Fujimoto M, Yuan X, Akada J, Aoshima-Okuda M, Mitani N, Itoh Y, Katoh T, Morita Y, Nagasaka Y, Yamazaki Y, Kuriki T, Sobel A. Analysis on heat stress-induced hyperphosphorylation of stathmin at serine 37 in Jurkat cells by means of two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and tandem mass spectrometry. Journal of chromatography. 2006;1106:181–189. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2005.12.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogueira da Costa A, Keen JN, Wild CP, Findlay JB. An analysis of the phosphoproteome of immune cell lines exposed to the immunomodulatory mycotoxin deoxynivalenol. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2011a;1814:850–857. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogueira da Costa A, Mijal RS, Keen JN, Findlay JB, Wild CP. Proteomic analysis of the effects of the immunomodulatory mycotoxin deoxynivalenol. Proteomics. 2011b;11:1903–1914. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201000580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen JV, Blagoev B, Gnad F, Macek B, Kumar C, Mortensen P, Mann M. Global, in vivo, and site-specific phosphorylation dynamics in signaling networks. Cell. 2006;127:635–648. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong SE, Blagoev B, Kratchmarova I, Kristensen DB, Steen H, Pandey A, Mann M. Stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture, SILAC, as a simple and accurate approach to expression proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2002;1:376–386. doi: 10.1074/mcp.m200025-mcp200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman AM, Pennings JLA, Blokland M, Peijnenburg A, van Loveren H. Protein expression profiling of mouse thymoma cells upon exposure to the trichothecene deoxynivalenol (DON): Implications for its mechanism of action. Journal of Immunotoxicology. 2010;7:147–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen HR, Elser M, Cheung E, Gersbach M, Kraus WL, Hottiger MO. MYBBP1a is a novel repressor of NF-kappaB. Journal of molecular biology. 2007;366:725–736. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.11.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pakala SB, Bui-Nguyen TM, Reddy SD, Li DQ, Peng S, Rayala SK, Behringer RR, Kumar R. Regulation of NF-kappaB circuitry by a component of the nucleosome remodeling and deacetylase complex controls inflammatory response homeostasis. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010;285:23590–23597. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.139469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Pandey A, Mann M. Proteomics to study genes and genomes. Nature. 2000;405:837–846. doi: 10.1038/35015709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavicevic Z, Leslie CC, Malik KU. cPLA2 phosphorylation at serine-515 and serine-505 is required for arachidonic acid release in vascular smooth muscle cells. Journal of lipid research. 2008;49:724–737. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700419-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pestka JJ. Mechanisms of deoxynivalenol-induced gene expression and apoptosis. Food Addit Contam Part A Chem Anal Control Expo Risk Assess. 2008;25:1128–1140. doi: 10.1080/02652030802056626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pestka JJ. Deoxynivalenol-induced proinflammatory gene expression: mechanisms and pathological sequelae. Toxins (Basel) 2010;2:1300–1317. doi: 10.3390/toxins2061300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pestka JJ, Amuzie CJ. Tissue distribution and proinflammatory cytokine gene expression following acute oral exposure to deoxynivalenol: comparison of weanling and adult mice. Food Chem Toxicol. 2008;46:2826–2831. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pestka JJ, Zhou HR, Moon Y, Chung YJ. Cellular and molecular mechanisms for immune modulation by deoxynivalenol and other trichothecenes: unraveling a paradox. Toxicol Lett. 2004;153:61–73. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2004.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pflum MK, Tong JK, Lane WS, Schreiber SL. Histone deacetylase 1 phosphorylation promotes enzymatic activity and complex formation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:47733–47741. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105590200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajaram MV, Ganesan LP, Parsa KV, Butchar JP, Gunn JS, Tridandapani S. Akt/Protein kinase B modulates macrophage inflammatory response to Francisella infection and confers a survival advantage in mice. J Immunol. 2006;177:6317–6324. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.6317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Carrozzi VR, Nazarian AA, Li CC, Gore SL, Sridharan R, Imbalzano AN, Smale ST. Selective and antagonistic functions of SWI/SNF and Mi-2beta nucleosome remodeling complexes during an inflammatory response. Genes & development. 2006;20:282–296. doi: 10.1101/gad.1383206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raschke WC, Baird S, Ralph P, Nakoinz I. Functional macrophage cell lines transformed by Abelson leukemia virus. Cell. 1978;15:261–267. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90101-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauh MJ, Sly LM, Kalesnikoff J, Hughes MR, Cao LP, Lam V, Krystal G. The role of SHIP1 in macrophage programming and activation. Biochemical Society transactions. 2004;32:785–788. doi: 10.1042/BST0320785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers LD, Foster LJ. The dynamic phagosomal proteome and the contribution of the endoplasmic reticulum. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:18520–18525. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705801104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rooney JW, Calame KL. TIF1beta functions as a coactivator for C/EBPbeta and is required for induced differentiation in the myelomonocytic cell line U937. Genes & development. 2001;15:3023–3038. doi: 10.1101/gad.937201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Saccani S, Pantano S, Natoli G. p38-Dependent marking of inflammatory genes for increased NF-kappa B recruitment. Nature immunology. 2002;3:69–75. doi: 10.1038/ni748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sag D, Carling D, Stout RD, Suttles J. Adenosine 5′-monophosphate-activated protein kinase promotes macrophage polarization to an anti-inflammatory functional phenotype. J Immunol. 2008;181:8633–8641. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.12.8633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders MJ, Ali ZS, Hegarty BD, Heath R, Snowden MA, Carling D. Defining the mechanism of activation of AMP-activated protein kinase by the small molecule A-769662, a member of the thienopyridone family. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:32539–32548. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706543200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultze SM, Hemmings BA, Niessen M, Tschopp O. PI3K/AKT, MAPK and AMPK signalling: protein kinases in glucose homeostasis. Expert reviews in molecular medicine. 2012;14:e1. doi: 10.1017/S1462399411002109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharif J, Muto M, Takebayashi S, Suetake I, Iwamatsu A, Endo TA, Shinga J, Mizutani-Koseki Y, Toyoda T, Okamura K, Tajima S, Mitsuya K, Okano M, Koseki H. The SRA protein Np95 mediates epigenetic inheritance by recruiting Dnmt1 to methylated DNA. Nature. 2007;450:908–912. doi: 10.1038/nature06397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama Y, Hatano N, Sueyoshi N, Suetake I, Tajima S, Kinoshita E, Kinoshita-Kikuta E, Koike T, Kameshita I. The DNA-binding activity of mouse DNA methyltransferase 1 is regulated by phosphorylation with casein kinase 1delta/epsilon. The Biochemical journal. 2010;427:489–497. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweet T, Khalili K, Sawaya BE, Amini S. Identification of a novel protein from glial cells based on its ability to interact with NF-kappaB subunits. Journal of cellular biochemistry. 2003;90:884–891. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisniewski JR, Zougman A, Nagaraj N, Mann M. Universal sample preparation method for proteome analysis. Nature methods. 2009;6:359–362. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong SS, Zhou HR, Pestka JJ. Effects of vomitoxin (deoxynivalenol) on the binding of transcription factors AP-1, NF-kappaB, and NF-IL6 in raw 264.7 macrophage cells. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2002;65:1161–1180. doi: 10.1080/152873902760125381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi T, Keough RA, Gonda TJ, Ishii S. Ribosomal stress induces processing of Mybbp1a and its translocation from the nucleolus to the nucleoplasm. Genes Cells. 2008;13:27–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2007.01148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Kahn BB, Shi H, Xue BZ. Macrophage alpha1 AMP-activated protein kinase (alpha1AMPK) antagonizes fatty acid-induced inflammation through SIRT1. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010;285:19051–19059. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.123620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu B, Bi L, Zheng B, Ji L, Chevalier D, Agarwal M, Ramachandran V, Li W, Lagrange T, Walker JC, Chen X. The FHA domain proteins DAWDLE in Arabidopsis and SNIP1 in humans act in small RNA biogenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:10073–10078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804218105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng B, Jeong JH, Asara JM, Yuan YY, Granter SR, Chin L, Cantley LC. Oncogenic B-RAF negatively regulates the tumor suppressor LKB1 to promote melanoma cell proliferation. Molecular cell. 2009;33:237–247. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou HR, Harkema JR, Yan D, Pestka JJ. Amplified proinflammatory cytokine expression and toxicity in mice coexposed to lipopolysaccharide and the trichothecene vomitoxin (deoxynivalenol) J Toxicol Environ Health A. 1999;57:115–136. doi: 10.1080/009841099157818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou HR, Islam Z, Pestka JJ. Induction of competing apoptotic and survival signaling pathways in the macrophage by the ribotoxic trichothecene deoxynivalenol. Toxicol Sci. 2005a;87:113–122. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou HR, Jia Q, Pestka JJ. Ribotoxic stress response to the trichothecene deoxynivalenol in the macrophage involves the SRC family kinase Hck. Toxicol Sci. 2005b;85:916–926. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou HR, Lau AS, Pestka JJ. Role of double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase R (PKR) in deoxynivalenol-induced ribotoxic stress response. Toxicol Sci. 2003;74:335–344. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfg148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.