Abstract

Internet usage and accessibility has grown at a staggering rate, influencing technology use for healthcare purposes. The amount of health information technology (Health IT) available through the Internet is immeasurable and growing daily. Health IT is now seen as a fundamental aspect of patient care as it stimulates patient engagement and encourages personal health management. It is increasingly important to understand consumer health IT patterns including who is using specific technologies, how technologies are accessed, factors associated with use, and perceived benefits. To fully uncover consumer patterns it is imperative to recognize common barriers and which groups they disproportionately affect. Finally, exploring future demand and predictions will expose significant opportunities for health IT. The most frequently used health information technologies by consumers are gathering information online, mobile health (mHealth) technologies, and personal health records (PHRs). Gathering health information online is the favored pathway for healthcare consumers as it is used by more consumers and more frequently than any other technology. In regard to mHealth technologies, minority Americans, compared with White Americans utilize social media, mobile Internet, and mobile applications more frequently. Consumers believe PHRs are the most beneficial health IT. PHR usage is increasing rapidly due to PHR integration with provider health systems and health insurance plans. Key issues that have to be explicitly addressed in health IT are privacy and security concerns, health literacy, unawareness, and usability. Privacy and security concerns are rated the number one reason for the slow rate of health IT adoption.

Keywords: informatics, personal health record, technology, consumer, patient, medical data

INTRODUCTION

The consumer use of information technology for the purpose of personal healthcare is a relatively new concept, nonetheless, a practice that is becoming increasingly important to healthcare professionals, government officials, and patients alike. The enormous variety of consumer health information technologies available online continues to increase in size. A driving factor of its widespread adoption is the staggering growth of Internet use. As an indication of its expanding dominance in America, Internet usage among Americans rose from 54% to 80% in just 10 years.1 In addition to increased Internet use, other changes associated with the Internet in the past decade include broadband replaced dial-up Internet connection, Internet became available via mobile devices including cell phones and Tablets, and Wi-Fi connectivity became widely accessible for the public in libraries, hospitals, coffee shops, and on campuses, not to mention passengers can now connect while en route on an airplane.1 A report issued by the National Telecommunications and Information Administration1 indicated that 71% of American households have home Internet service, making the Internet easily accessible for majority of Americans, thus drastically reducing the digital divide. This increase in Internet usage and availability has caused healthcare to evolve rather quickly. Patients seek, gather, and make decisions based on information about healthcare online and that is pressuring healthcare providers to provide information and interact with patients online. As a result, the healthcare industry is rushing to adapt to an online world where information is at patients’ fingertips and patients often expect immediate answers. Accordingly, patients are now thought of as consumers, individuals who are proactive, in control, and well informed of their personal healthcare. This shift, although recent, is one of great significance. As Eysenbach notes,2 ‘information technology and consumerism are synergistic forces that promote an ‘‘information age healthcare system’’ in which consumers can, ideally, use information technology to gain access to information and control their own healthcare, thereby utilizing healthcare resources more efficiently’.

Giving patients both access to their health information and electronic tools for using that information can better position them to participate more fully in their care. Patients can self-manage their conditions, coordinate care across multiple providers, and improve communication with healthcare professionals.3 Thus, health information technology (Health IT) is increasingly seen as vital for patient engagement and patient empowerment as it allows patients to take charge of their own health and their interactions with health professionals.3 Studies have shown that people who use e-health resources feel better prepared for clinical encounters, ask more relevant questions, know more about their healthcare, and are more likely to take steps to improve their health, compared to those who do not.4

It is crucial to understand consumers of healthcare technologies due to the large proportion of Americans who use them, the proven benefits of healthcare online applications, and the continued growth in this area. The aim of this article is threefold: (1) to investigate healthcare consumer’s online patterns (e.g., where and how they access health technologies); (2) to identify common barriers that prevent further adoption of healthcare technologies; and (3) to predict future consumer demand of healthcare technology.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Patterns and Usage of Consumer e-Health Tools

The purpose of consumer health informatics is to provide quality healthcare information on the Internet, easy access to electronic health records (EHR), and discover innovative ways for consumers to track and manage their health.5 Computers and mobile devices are increasingly being used for information gathering and healthcare decisions by patients.5–7 The following are some terms and definitions that are commonly used in consumer informatics.

Health information technology (health IT) is defined as the electronic systems healthcare professionals and patients use to store, share, and analyze health information.8

Consumers include patients, families, and caregivers regardless if they are actively receiving healthcare services.4

Consumer e-health describes electronic tools and services that are designed for consumer usage in an effort to broaden health IT.4,8

e-Health Tools include secure Internet portals to enable patients’ access to information in their EHRs; personal health records (PHRs); patient-provider secure e-mail messaging; personal monitoring devices; mobile health (mHealth) apps; and Internet-based resources for health education, information, advice, and peer support.4,8

This article provides an overview of consumer patterns related to searching for health information online, mobile device usage, and PHRs.

Consumers Seek Health Information Online

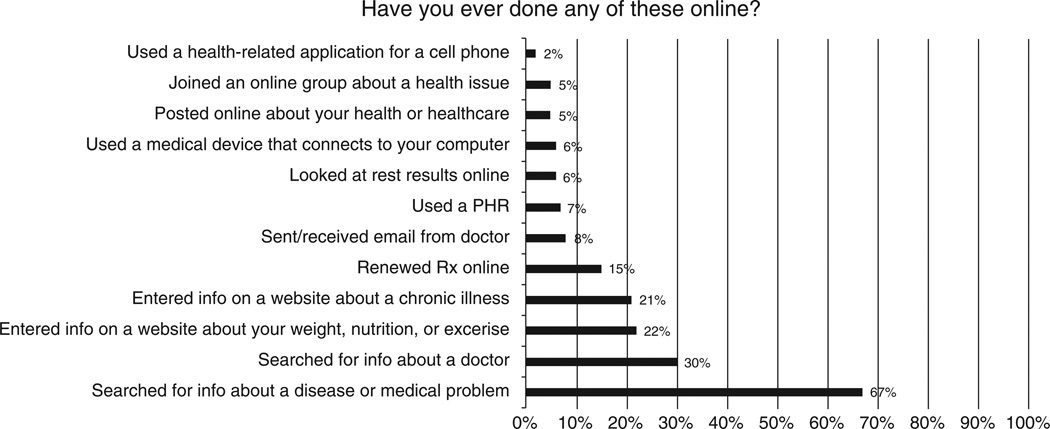

‘Health seekers’ can be defined as ‘Internet users who search online for information on health topics, whether they are acting as consumers, caregivers, or patients’.9 Remarkably, more than half of all American adults fall into this health seeker category.10 As an indicator of the vast use of the Internet related to health, an estimated 8 million American adults search the Internet for health information on any given day, placing health searches at about the same level of popularity as paying bills online.9 Furthermore, a large number of all Internet users (47%) use the Internet for health information at least monthly.11 This suggests that Americans are seeking health information quite frequently. As indicated in Figure 1, the California Healthcare Foundation surveyed 1849 adults nationwide about health IT in 2010. The report titled, ‘Consumers and Health Information Technology: A National Survey’ illustrates the large use of online information seeking compared to other health e-tools (see Figure 1).12

FIGURE 1.

Health information technologies and current usage.

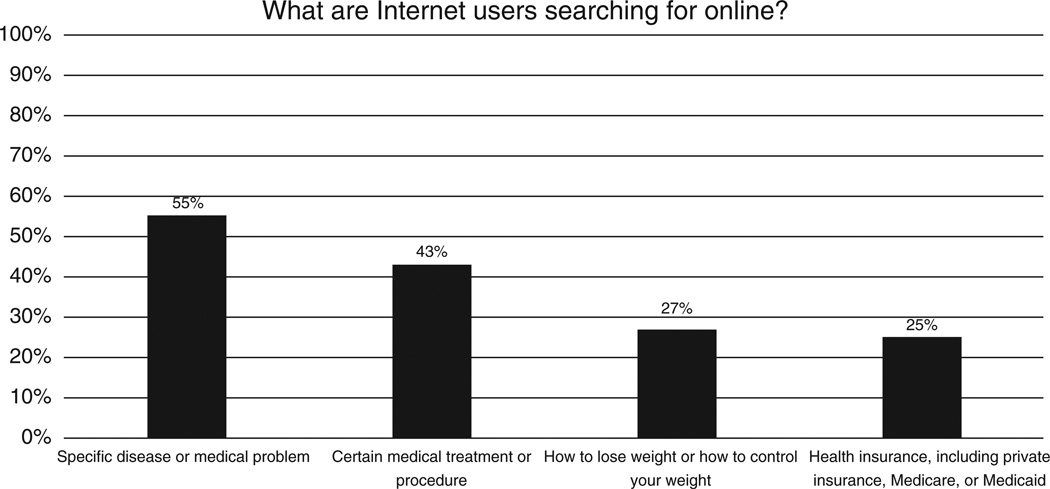

The Internet has been recognized as a significant source of health information. Consumers have identified the Internet as a valuable tool for self-education, supplementing information obtained by a provider, getting advice from peers, and a means of obtaining a second opinion.13,14 With regard to online health searches, specific diseases and medical conditions have been identified as the most frequently searched health topics.10,12–14 Information on medical treatments or procedures9,10,14,15 and information on diet/nutrition9,10,14 follow in popularity among health searches. Recently, the Pew Internet and American Life Project released its 2013 Online Health Report, which consisted of survey responses from 3014 U.S. adults.10 Findings from the 2013 Online Health Report support previous research in regard to online health searches and are illustrated in Figure 2. Although previous studies tend to agree on the health topics searched online, one study found that seniors most often search for information on prescription drugs.16

FIGURE 2.

Health search topics.

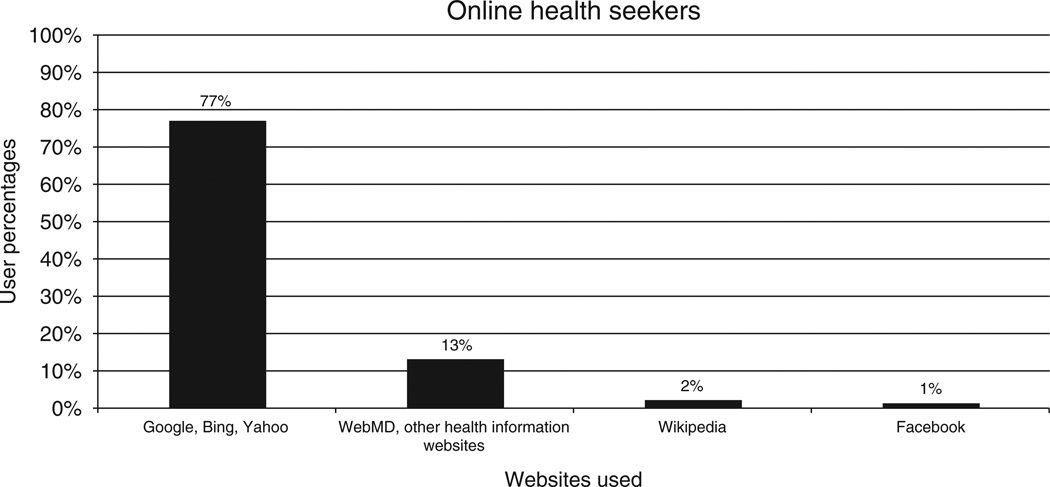

A variety of websites exist containing health information. A simple search for ‘flu’ on Google’s search engine provided ‘about 88,500,000 results in 0.18 seconds’. Owing to the abundance of health information online, studies have explored the methods health seekers use to gather information. One study found that health seekers rarely visit only one health website, but instead visit at least two.9 Several studies reveal that majority of health seekers consult general search engines such as Google or Yahoo! to find information.9,10 Websites devoted entirely to health information such as WebMD, ranked second among websites visited by health seekers.10 Figure 3 illustrates findings from the 2013 Online Health report by Pew Internet and American Life Project.

FIGURE 3.

How health seekers gather information online.

WebMD is often mentioned in health seeking studies and literature. WebMD offers a vast array of health information including a symptom checklist, prescription drug information, and an abundance of specific medical information.17 Recently, WebMD reported that an astounding 60 million unique users accessed the site per month.18 One study estimated that WebMD content is read by 95% of U.S. health seekers over the course of a year.19 In another study, health seekers were asked to identify three websites for health information and more than half cited WebMD.19 These findings imply WebMD is perhaps the most well-known health website among health seekers.

Several studies have examined demographics of health seeking individuals. These studies found that women are more likely than men to search for health-related information online.9,10,13,20 22 Additionally, more frequent health-related Internet use has been associated with people younger than 65 and college graduates.,9,10,13,18,23,24 Lower levels of health literacy have been found to be associated with less health-related Internet usage.25 One study found that individuals living in rural areas were less likely to search for health information online.22 It is important to note that high percentages of all ages are online seekers. More than 67% of all online seniors have used the Internet to access health information.26 A major distinction between older health seekers and younger health seekers is the perceived benefits of its use. Recent studies show that older people turn to the Internet because of the amount of information available, whereas younger people go online because of its relative speed.16,20

Half of health information searches are on behalf of someone else.9,10 This is expected as 30% of all U.S. adults are caregivers.26 Caregivers are unique health seekers in regard to their seeking behavior. As an example, one study found caregivers are more likely than any other group to search the Internet for doctor and hospital reviews.14 Furthermore, caregivers are more likely to utilize social media for health-related purposes compared to those who are not caregivers.10,14

Research has demonstrated that adults with chronic illnesses are less likely to have Internet compared to adults without a chronic illness.10,15,27 Once adults with a chronic illness become Internet users, health-related Internet use is substantially higher with those who have a chronic illness.9,10,15,24 One study found that 86% of Internet users living with a chronic illness use the Internet to gather information about health topics compared to 80% of Internet users without a chronic illness.19 Unlike other seekers, consumers with chronic conditions are more likely to utilize peer-to-peer and social media online resources such as discussion forums, blogging, and chat rooms.4,10,26,27 Research demonstrates that 25% of U.S. adults with high blood pressure, diabetes, heart conditions, lung conditions, cancer, or some other chronic ailment have used peer-to-peer online resources.28 Online resources allow consumers to find others with similar conditions and exchange information on treatments, providers, and overall experiences.10,28 Similarly, consumers report that online communities aid in understanding their illness, making better healthcare choices, alerting them to health issues, and accessing more appropriate services.29 PatientsLikeMe and CureTogether have been reported as the dominant peer-to-peer online communities for health consumers.28 Perhaps the most distinctive features of peer-to-peer online resources are consumer reported feelings of encouragement and emotional support.26–29 One study using PatientsLikeMe users and data found that majority of members reported an improved psychological experience of living with their conditions due to the ability to connect with others.30 Another study of note investigated the extent to which the Internet was perceived as beneficial for Internet users with chronic illnesses.15 The study wanted to answer whether the stage of a patient’s disease increased Internet health seeking or not. It was found that the perceived benefit of online health information remained consistent for seekers with a chronic illness during all stages of their disease (e.g., diagnosis, treatment).15 Strategies to feel connected and supported also include online blogging.14,27,28 Consumers living with at least one chronic illness who maintained a blog tended to report increased connection with others and decreased feelings of lonliness.27

Although the Internet is a trusted and common channel for accessing health information, consumers continue to rate health professionals as their first choice when health concerns arise.14,31 Generally, information from the Internet supplements information received from health professionals.13,15,23,31,32 It is important to understand that majority of health consumers are not turning to the Internet to replace face-to-face interaction with healthcare professionals. Several studies15,23,33 have verified that majority of health seekers perceive Internet content as supplemental information or a way to be more informed and engaged in their personal health decisions. This suggests that information gathering is a result of the desire for patient engagement and patient empowerment. For example, one study demonstrated that majority of seekers (74%) feel more confident about their ability to make appropriate healthcare decisions after reading online health information, be it before or after consultation with a health professional.9 Additionally, research has shown that frequent visits to healthcare providers are associated with more Internet use for health information.9,24

Gathering supplemental information occurs by health seekers either before or after consulting a health professional. Numerous studies have examined the differences between health information seekers who turn to the Internet before seeing a health professional and those who seek supplemental information following a consultation. One study found that over half of health seekers turn to the Internet before seeing a health professional.21 Recent reports show that many of these seekers consult the Internet for appointment preparation, that is, researching questions to ask health professionals and gaining a basic understanding of their medical concern.13,15,23,31 As a result, health seekers are generally more confident to raise questions or concerns with their healthcare provider than those who are not seekers.9 Another result of information seeking prior to consultation includes consumer requests for clinical resources (e.g., specific tests or procedures to be done, referral to a specialist). In fact, one study found that over half of all health seekers who consulted the Internet prior to a visit reported requesting additional clinical resources.31 Typically, turning to the Internet first before a consultation is associated with a younger age and a higher level of education.13,21 The majority of health seekers 35 and older consult the Internet after seeing a professional healthcare provider.21 Another study found that health seekers who use the Internet after seeing a health professional tend to be more comfortable with their provider than those who consult the Internet first.20 This suggests that patient satisfaction is associated with health seeking behavior.

Recent studies have explored patient satisfaction in regard to health seeking behavior. Studies have shown patients who are unsatisfied with their physician are more likely to use the Internet for health information and tend to rely more on the information they find.21,24 Patients who are dissatisfied are more likely to use the Internet as a primary source of health information and turn to the Internet first with a medical concern.21,32 In line with patient satisfaction, other studies suggest that satisfaction with the amount of emotional support (empathy) patients receive from providers is also a factor of online usage and reliance. Patients who do not feel empathy are more likely to use and rely on the Internet for health information and support.32,34

Mobile Health

mHealth is defined as the use of mobile and wireless technologies to support the achievement of health objectives.35 In the context of this article, mHealth refers to the use of cell phone technology for health-related activities including SMS text messaging and mobile applications. mHealth is a relatively new addition to consumer health technologies that has great potential and high expectations. Consumers are increasingly interested in the use of mHealth due to its convenience, accessibility, and ability to increase patient control and management.36

To understand the scope and potential for mHealth, it is important to note that 85% of U.S. adults own a cell phone and a little over half of those are smartphone owners.6 The iPhone is owned by one third of U.S. smartphone users.36 Roughly 75million individuals (about 31% of the U.S. population) have used mobile phones for health information and apps in 2012.6 More frequent health-related mobile usage is associated with Latinos, African Americans, those between the ages of 18 and 49, and college graduates.6,37,38 According to a 2012 study from Manhattan Research,36 slightly more mHealth users are male (54%) and the average age is 35. Another study reported similar findings, where health app usage was highest among adults aged 30–49. mHealth usage for all age groups is steadily increasing annually.27

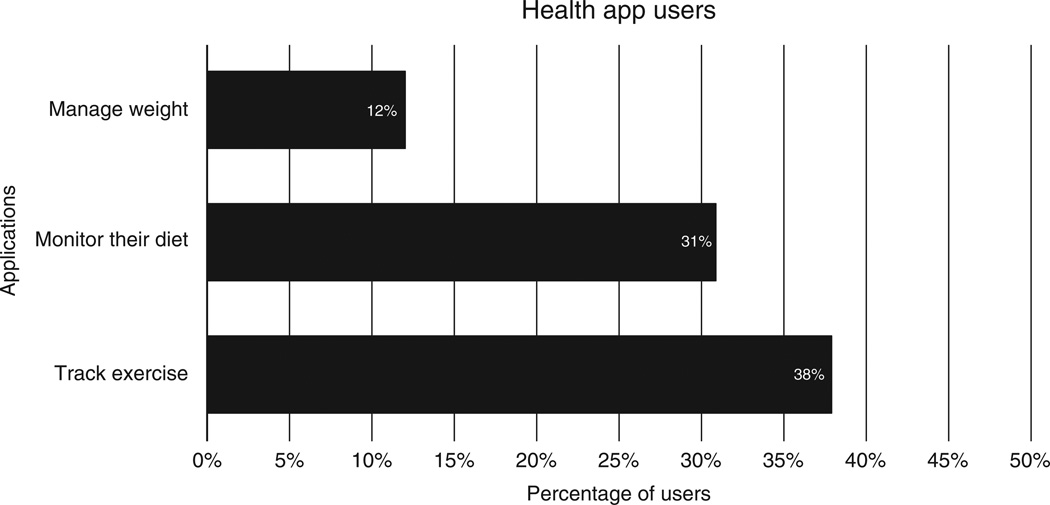

Consumer health apps are among the most used mHealth technologies.6,14,36,38 Consumer health apps include those used for health and medication reference, exercise/fitness, condition management, mobile monitoring, and wellness/nutrition.37 The ability to customize health apps has shown to empower patients through less burdensome health management and monitoring.39 As of April 2012, over 13,600 consumer health apps were available in the Apple iTunes store.7 Consumer wellness and fitness apps account for approximately 70%ofmHealth apps and are the most used apps on the market.7,37 Within the wellness and fitness category, apps revolving around exercise, diet, and weight are most popular. As an indicator, the Pew Internet and American Life Project issued a 2012 report on mHealth and found that among health app users the most frequently used apps are those which track their exercise, monitor their diet, and manage their weight (see Figure 4).6

FIGURE 4.

Health app users.

Apps aimed at managing conditions and mobile/home monitoring has become recently available for the most common chronic conditions.37 Few studies have been conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of this innovative approach.38

It is believed by many healthcare industry leaders that mHealth will have the greatest impact on healthcare delivery in the near future.36 Despite consumer’s positive thoughts on mHealth, widespread adoption is too slow and too low to adequately address consumer behavior.6,7,35–38

Personal Health Records

PHR stores and maintains patient health information, such as diagnoses, medications, immunizations, family medical history, and contact information, for providers.8 The goal of a PHR is to ‘empower patients so they can make the most informed decisions possible about their health.’40 PHRs enable information collection and storage; the ability to share information (e.g., patient to provider, patient to caregiver); information exchange (e.g., two-way exchange between provider and patient); and functions for self-management (e.g., symptom tracking).41 Functions of PHRs often include the recording and storing health information, accessing personal EHR used by providers, viewing lab results online, sending messages to providers, recording immunizations, and requesting medication refills.8,40,42,43

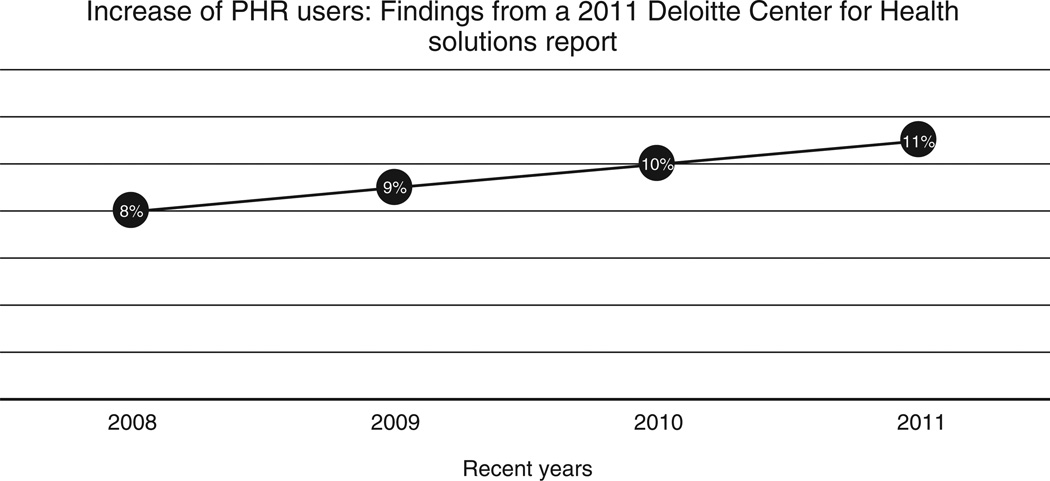

The percentage of consumers who maintain a personal health/medical record (PHR) in electronic format remains low.44,45 A 2010 report finds that only 7% of U.S. adults have an electronic PHR.12 Although the percentage of PHRs is low, it is continually growing. Deloitte Center for Health Solutions found that the number of PHR users has increased to 11% as of 2011.44 This growth of PHR users can be seen in Figure 5.

FIGURE 5.

Increase of PHR users.

Although PHR usage is low, a larger number of American adults state they are interested in using an online PHR.46 One study indicated as many as 106 million Americans are interested and willing to use a PHR.47 Additionally, majority of consumers strongly believe that using a PHR would benefit their health management and healthcare.48

According to few studies, men are slightly more likely to have a PHR than women.21,49 Contrary to the common stereotype about seniors and technology, recent reports demonstrate that seniors are the highest proportion of any age group to use PHRs.4,12 PHR usage has also been found to be high among Baby Boomers while4,12,18 Generation X was found to have the least amount of PHR users.4,12 Low PHR usage has also been associated with African Americans,50,51 Latinos,51 and those with lower levels of education.41,51 Individuals living with a chronic illness are more likely to utilize a PHR.12,33,41

A recent study found that 80% of consumers who have access to their health records use them often. This may indicate a high-perceived benefit among current PHR users.46 Furthermore, consumers who use PHRs report that it has had a positive effect on their overall perceived health.46 PHR users also report a better understanding of their health and conditions and thus, feel they are taking steps to improve their health.12,46,52

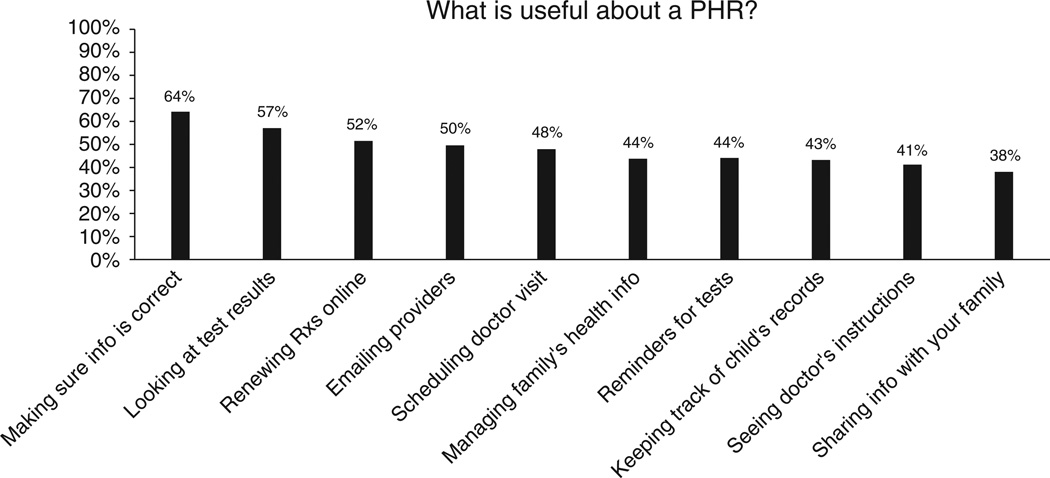

The number one reported benefit of maintaining a PHR is the ability to make sure information on your EHR, which is maintained by health professionals, is correct.33 Reported benefits also include the ability to view test results, renew prescriptions online, and email providers.33,53 These findings are consistent with a recent 2010 survey by the California Healthcare Foundation. The foundation asked respondents who were current PHR users about whether they felt it was a useful PHR function (see Figure 6).12 One study found that among seniors, the number one benefit and most frequent PHR function used is medication reporting, which differs from other PHR user groups.54

FIGURE 6.

What is Useful about a PHR.

Interestingly, another study reported the most common request to providers regarding a PHR is correction of something recorded incorrectly. This is a finding that supports the importance of patient access to view their EHR.52

There are three forms of PHRs: tethered, standalone, and sponsored.8,43 Tethered PHRs are hosted by a healthcare provider and tied to the corresponding electronic health system (EHR).8,42,43 Standalone PHRs are untethered and used only by the patient, usually through a web-based portal.8,40,43 Sponsored PHRs are hosted by a patient’s employer or health insurance plan and generally linked to claims data and information.8,43

Tethered PHRs

Provider-populated PHRs are tethered to patient EHRs, thus requiring adoption of EHRs by patient’s providers.40 As of 2011, tethered PHRs account for 26% of PHR usage.12 Functions of tethered PHRs typically include patient access to their medical health records to ensure information is correct, viewing lab results online, sending secure messages to providers, personally recording health information, and requesting refills.8,42,43 Interestingly, one survey indicated that non-PHR users are most interested in obtaining a PHR provided by their physicians.12

The most active portal in this category is Kaiser Permante’s PHR—My Health Manager. In 2011, it was reported that My Health Manager had 4 million active users.55 A recent report indicates that more than 63% of eligible members use My Health Manager.53 The most frequently used features on a daily bases are secure e-mail messages sent to providers (more than 1 million) and viewing lab results (2.5 million).53 My Health Manager is linked to Kaiser Permanente’s EHR system and provides a variety of functions including access to health records, ability to view test results, connecting with a physician via e-mail, ordering prescriptions, and scheduling/viewing appointments.56 In a recent study, Kieser found that the use of PHRs increases the likelihood of member retention and customer loyalty.53

Another provider-integrated PHR of note is the My HealtheVet, the Veteran Affair’s online personal health record. As of June 2011, My HealtheVet had 1,360,897 registered users.45 Veterans receiving care at a VA medical center are able to view their electronic medical record, view test results on line, view appointments, and communicate with providers using secure e-mail through the site, among other functions. Recently Blue Button was added as a function of My HealtheVet which allows users to download labs, appointments, prescriptions, and other medical records enabling portability and access to information almost anywhere.57

Standalone PHRs

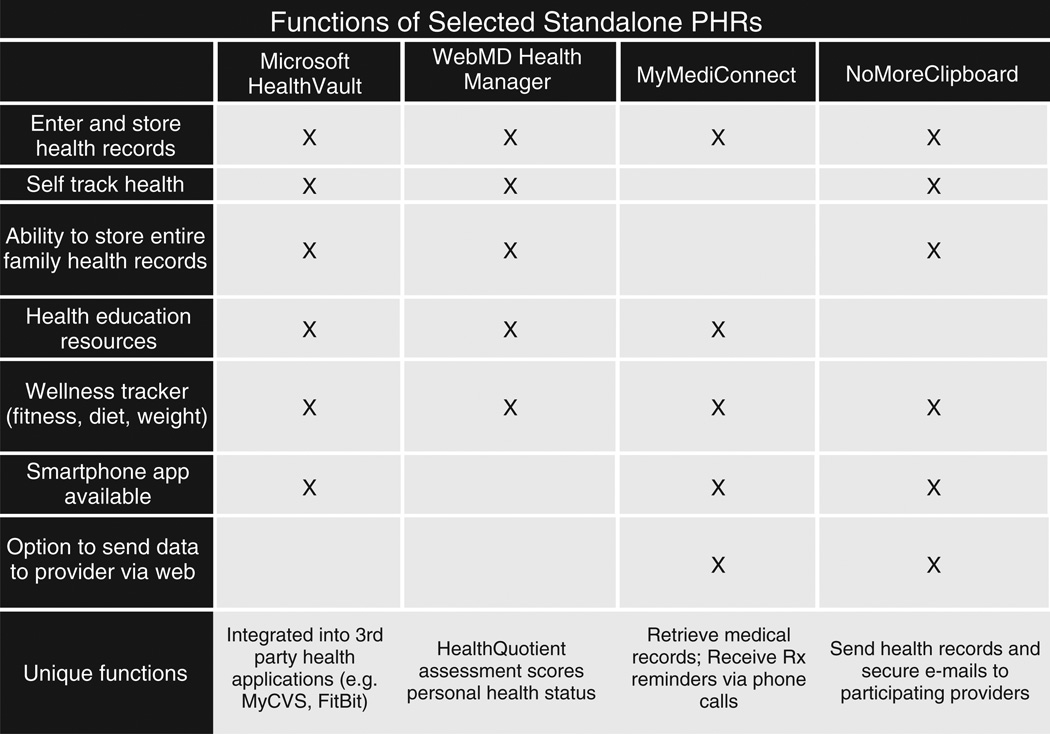

Functions of PHRs used only by a patient and not connected to an EHR typically include the ability to record and store all medical information (e.g., allergies, medical conditions, family history, and current medications) and self-track your health (e.g., weight, height, and blood pressure).8,40,43 The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) offers a wide variety of information on Health IT and how technologies can be used for individual personal health management on their website www.healthit.gov.58 The page dedicated to PHRs includes a list of certified products on the market. Those systems endorsed by the ONC include (1) Microsoft HealthVault, a free PHR system that integrates with multiple web sites and personal health devices; (2) WebMD Health Manager, a free standalone PHR system with some options for sharing information with doctors and others; (3) MyMediConnect, a free standalone PHR system with some options for sharing information with doctors and others; (4) NoMore Clipboard, secure, online, easy-to-use tool that helps you compile, manage and share your medical records.58 Figure 7 illustrates the similarities and differences between the four PHRs recommended by the ONC.

FIGURE 7.

Functions of selected standalone PHRs.

Limited information exists on patterns and behaviors of individuals who use untethered PHR systems. The limited data on consumer use of untethered PHRs concludes that they are the least used PHR systems.12,40 A November 2009 report indicated that 2% of U.S. consumers use a PHR from WebMD and 1% use HealthVault.40 Another report found that only 6% of PHR users did not use a PHR from a health plan, employer, or provider indicating their source was a standalone PHR.12

Sponsored PHRs

Sponsored PHRs offer customized health information (e.g., preventative care, prescriptions) and transparency of cost and quality data.59 Sponsored PHRs are offered through an employer or health insurance plan. In 2008, WebMD conducted a survey with more than 20,000 employees with access to sponsored PHRs.18 The study indicated higher sponsored PHR usage was associated with the Baby Boomer generation, salaried staff, full-time employees, higher levels of education, and those informed of the PHR through e-mail.18 There was no difference in usage among men and women.18

Aetna’s ActiveHealth Management is among the most used sponsored PHR.40,59 As of May 2008, over 6 million consumers were using ActiveHealth Management.59 Members are able to share access to their PHRs with providers, caregivers, and family members. Additionally, they can create reminders for preventative care, personalized messaging and alerts based on health data including lab results and medications, and view tests and procedures.59

Barriers for Health IT Implementation

The four most common barriers for health IT implementation among consumers are privacy and security concerns, health literacy, unawareness, and usability. These barriers are helpful in understanding the slow rate of e-tool adoption by consumers.

Privacy/Security

It is evident that a primary concern of patients is the privacy and security of their personal health data. Despite HIPPA privacy laws and the recent HITECH Act, both of which directly involve e-Health usage, privacy and security of health information remain an incredibly large concern for Americans.4,12,33,41,44,48,60 62 This concern only continues to grow with increases in health technology usage.33 These uneasy feelings about health information security among a large portion of health consumers have influenced the slow PHR adoption rate and current usage.33,41,51,62 A wealth of literature exist surrounding feelings of concern toward privacy and security of health data. These studies show that greater concerns are associated with ethnic and racial minorities, Baby Boomers, and those living with a chronic illness.33,44,46,61 One surprising study of note indicated that concerns are lowest among seniors.44

Stories of high-profile security and privacy breaches in healthcare have surfaced recently in the media, adding to the concern of consumers. As required by the HITECH Act, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services posts a list of breaches of unsecured health information affecting 500 or more individuals. Between 2009 and April 2013 an astounding 571 incidences matching this criteria were reported.63 In 2011 alone, TRICARE Management Activity (TMA) reported the loss of backup tapes affecting the privacy and security of 4.9 million individuals. That same year, Health Net Inc. reported 1.9 million lost records due to missing hard drives.63 Moreover, patients do not fully understand HIPPA privacy laws or the HITECH Act adding to security and privacy concerns.61 One survey found that learning about government privacy rules would highly encourage PHR and health technology usage among those who currently do not.12 Several studies have found that concern for privacy is the main reason consumers choose not to adopt a PHR.48,51 The amount of people concerned with privacy and security more than double those that are not concerned.60

It is difficult to understand the full effect security and privacy concerns have on whether patients will use health technologies or not. A study found that 64% of people believe the benefits of using computer technologies to maintain records outweigh privacy risks.60 Similarly, once patients begin to use PHRs, they are less concerned with privacy.12,41,44 Security concerns are also shown to decrease with the perception of value a PHR will bring to the consumer.41

Health Literacy

Health literacy is defined as ‘the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions.’64 According to results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy, 36% of U.S. adults have basic or below basic health literacy skills.25 As many as 80% of Americans have limited health literacy skills, meaning they have trouble understanding complex health information.8,25 Health literacy skills are disproportionately low among the economically disadvantaged, seniors, and ethnic minorities.25,50,65

The inability to fully understand health content gathered via online seeking has been identified as a major barrier across various types of consumer health technologies. While the Internet has made health information easily accessible, the cognitive ability to read and understand the material accessed can be challenging.19,21,66,67 The use of clinical information and technical jargon create a real possibility of misinformed or confused patients as a result of information obtained from the Internet.21,33,50,66,67 A great deal of studies and articles accessed online include probabilities, reasoning about risk, proportions, and converting data from one representation to another.65 The National Institutes of Health recommends all health information sources not exceed fourth- to sixth-grade reading level; however, a large portion regularly exceed this. Furthermore, health consumers often access U.S. medical curricula, which are written for a scientific audience.66 Rarely do authors of these articles have the ability or knowledge of writing for patient education purposes nor are they patient-centered.33,66,68 Owing to lack of understanding, oftentimes health information gathered is useless in helping consumers make informed health decisions.67 The health literacy barrier is exceptionally high among non-English or English as a second language online seekers.65,69

Health literacy impacts patient’s ability to use PHRs.51,70,71 One particular study surveyed over 14,000 diabetic patients regarding their experience and behaviors with the Kaiser Permanete integrated PHR.70 Researchers found that patients who reported lower health literacy are less likely to use a patient-oriented Internet portal, regardless of regular access to the Internet.70 Of the 14,102 participants, 43% reported having problems learning about health due to reading difficulties, 28% reported needing help reading health related materials, and 19% were not confident with healthcare forms.70 The study concluded that those who reported low health literacy were more likely to never attempt to log on to the patient portal.70

There is some evidence that while health literacy is a significant predictor of e-Health usage, it does not impact peer-to-peer utilization. That is, mainstream social communities and condition-specific communities for the use of health information gathering and exchanging.31

Unawareness

A general unawareness surrounds health IT. While many are aware that the Internet holds an abundance of information including that surrounding healthcare, other existing health technologies are unknown to Americans. An astounding 76% of Americans have not heard of cell phone programs or applications available for tracking or keeping health information.12 Additionally, over half of Americans have not heard about PHR e-tools, whether they be tethered, sponsored, or standalone.12

As with any service or product, awareness of its existence and an understanding of the perceived benefits that comes along with its use drive demand and usability first and foremost. Health technology has a long way to go in this aspect.

Many believe the responsibility of making consumers aware of health e-tools lies in the hands of health professionals. Studies illustrate that providers are perhaps the number one driver for patient PHR adoption and usage.12,41,46 Awareness of PHRs and their benefits is usually communicated to consumers by their physicians.41,46 As such, when consumers who visit providers using EHRs they are more likely to want to use a PHR.12,41 One study examined the extent of provider encouragement and found that only 27% of doctors have discussed mHealth apps with patients and a reported 13% of doctors discourage its use.36

Usability

Another barrier to health IT implementation among consumers is the usability of e-Health tools. Usability encompasses various attributes of e-Health tools including effectiveness, learnability, efficiency, speed, ease of use, interface quality, information quality, perceived usefulness, and error tolerance.72,73 Consumers will usually defer from using systems or e-tools with weak usability attributes. Furthermore, consumers who do adopt e-Health tools will often stop usage if they find the tool difficult to use.72 Specific examples include poor interface, difficulty navigating through functions, poor display of information, confusing functionality, and the amount of time it takes to perform a task.68,72,73

DISCUSSION

There is certainly not a lack of interest in health technology use among Americans today. As discussed earlier, countless studies show a majority of Americans want to use technologies to manage their healthcare. Consumers are looking for increased use of information technologies in the future, especially with the increased importance of the Internet and technology use in everyday life.

Adoption and implementation of health technologies among consumers require current flaws to be addressed. Jones and Kellermann believe the answer is through ‘more standardized systems that are easier to use, are truly interoperable, and afford patients more access to and control over their health data.’68 These suggestions generally addresses majority of reasons consumers are discouraged from utilizing health technologies.

Interoperability, by definition, is the ability to create end-to-end solutions by interconnecting components and systems from multiple vendors forming a network.8 Consumers want interoperability with PHRs, EMRs, mobile phones, patient portals, and other monitoring devices.74 Without interoperability, health technologies have limited value. As an example, health apps used for tracking health and diet do not connect to a standalone PHR, which does not connect to a provider’s EHR. Therefore, it requires consumers to input duplicate information to update each form of health technology.

Looking toward the future, health IT interoperability will need to be addressed not only among consumer devices, but also health information between health providers and patients. A current issue with electronic health record systems is often they cannot exchange or share information.71 If a patient is seeing a family physician and a specialist, and the two providers have different EHR systems, information cannot be exchanged or shared. Patients frequently receive care from multiple healthcare providers making this an issue for many of Americans.45 Communication abilities, free of barriers between all EHR systems, PHR systems, and consumer devices, illustrate a perfectly interoperable health technology world. This design would truly make health management and health monitoring easy, therefore, benefiting all health consumers.

The Future of Consumer Health Technologies

mHealth is one of the newest health IT sectors and the potential for growth is increasing rapidly. A driving factor for the rapid growth of mHealth is widespread adoption of mobile use across multiple generations and diverse demographics.7,39 Not only do a majority of U.S. adults own a cell phone,6 but the frequent use of cell phones is also noteworthy. A recent international poll conducted by Time magazine found that 84% of people worldwide could not go a single day without their cell phones and 20% check their phone every 10min.75 As mobile technology usage explodes, so does the opportunity to expand mHealth. Already, healthcare consumers have expressed their excitement and high expectations for the future of mHealth. Half of American healthcare consumers predict that mHealth will be more convenient and will improve the cost and quality of their personal healthcare in the next 3 years.36 Further, the 2012 Deloitte Open Mobile Survey discovered 78% believed that the healthcare/life sciences sector held the greatest potential for mobile technology.39 Analysts expect the mHealth market will increase from $1.2 billion in 2011 to $11.8 billion by 2018.7 Perhaps, the most promising factor of mHealth is the fact that it is the fastest-growing content category for U.S. mobile users.7

mHealth has a great opportunity to influence minority populations. As indicated earlier, research has shown that minority Americans, compared with White Americans utilize social media, mobile Internet, and mobile applications more frequently. While minority populations tend to be less likely to seek health information online or use PHRs, mHealth is a perfect opportunity to capture this audience.

Healthcare consumers have identified areas in which they would like to see mHealth. Large portions of consumers indicate SMS text messaging is fairly unused in the healthcare industry. Close to 80% of cell phone owners say they send and receive text messages, but just 9% of cell phone owners say they receive any text updates or alerts about health or medical issues.6 An opportunity is available to increase SMS text messaging for appointment reminders and health programs.

Another mHealth trend is the use of mHealth for educational purposes. Research studies have shown that mobile devices in the classroom are useful to increase learning among students.38 As such health education and health promotion are seeking to understanding the best way of incorporating apps for patient education.38 An emerging educational tool in mHealth is ‘gamification’, which integrates fun activities and games to stimulate and reinforce self-directed learning.7,76 The few gamification apps that have been studied have demonstrated success by positively influencing health behavior. Brant, a mobile app, has been shown to successfully improve the frequency of glucose monitoring among its adolescent users.76 The trend of increased mHealth education and particularly gamification are expected to rise in use.

In the United States, 50% (133 million) of individuals are living with at least one chronic disease.27 This large portion of health consumers are usually in a position where self-tracking is extremely useful and often times necessary. As such, there is opportunity to use mHealth to increase the availability of mobile monitoring for chronic illnesses. The use of mobile phone monitoring has been studied in a few clinical trials and has proven effective in influencing positive behavior change in those with a chronic illness.38 Apps targeted toward specific chronic illnesses or enabling a wide range of monitoring and tracking can be useful for mHealth.

Recently, health insurance plans have realized the importance of an mHealth presence. Apps currently on the market enable consumers to find physicians, get information regarding benefits, review claims, and access customer self-service.59 Interestingly, few health plans even offer mPHR applications where consumers can use all PHR functions.7 This trend will spark further development of health plan apps and potentially more integration with PHRs.

We can expect to see an increase of websites that provide feedback on providers, healthcare experience, and peer-to-peer sharing.50,77 Sites like PatientsLikeMe have shown to appeal to the emotional side of consumers. Additionally, these types of websites are expected to increase in volume and size. It is expected that increased awareness in conjunction with the development of additional condition-specific groups will continue to be a significant attribute of online health seeking. Websites that allow for ratings and reviews of providers, health insurance plans, and facilities are likely to increase.77

An increase in kiosks at hospitals/clinics for patient check-in is expected in the near future.77,78 Virtual visits via instant messaging, telephone conversations, and videoconferencing are emerging in healthcare as well.42,77,78 CIGNA Healthcare began offering ‘virtual house calls’ to 170,000 participating members in July 2008. Members were able to reach out to their doctors online for advice on nonurgent health issues.59 Other health insurance plans are likely to follow. e-Visits allow patients to consult with providers and receive health coaching from specialists. The implementation of integrated EHR/PHR systems and self-monitoring devices that could send information electronically to doctors would provide an ideal situation for increased e-Visits. Studies have shown that videoconferencing e-Visists are perceived to be just as effective as face-to-face encounters to patients who have tried them.78 Additionally, one study showed that 56% of health consumers are interested in the ability to videoconference with doctors.62 Videoconferencing availability is especially beneficial for access to specialists or those living in rural areas.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This project was supported by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant 8UL1TR000105 (formerly UL1RR025764). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared no conflicts of interest for this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.US Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, National Telecommunications and Information Administration. Exploring the Digital Nation: Computer and Internet Use at Home. Washington, DC: National Telecommunication and Information Administration; 2011. pp. 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eysenbach G. Consumer health informatics. BMJ. 2000;320:1713–1716. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7251.1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson K, Marsh C, Flemming A, Isenstein H, Reynolds J. AAHRQ Publication No. 12-0061-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Jul, 2012. Quality measurement enabled by health IT: Overview, possibilities, and challenges. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ricciardi L, Mostashari F, Murphy J, Daniel JG, Simine-rio EP. A national action plan to support consumer engagement via e-health. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:376–384. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Virtual Informatics. [Accessed April 1, 2013]; Available at: http://www.virtualinformatics.com/content/Consumer_Health_informatics.htm.

- 6.Fox S, Duggan M. Mobile Health 2012. Washington, DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project; 2012. [Accessed March 15, 2013]. Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2012/Mobile-Health.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenspun H, Coughlin S. mHealth in an mWorld: How Mobile Technology is Transforming Healthcare. Washington, DC: Deloitte Center for Health Solutions; 2012. [Accessed March 26, 2013]. Available at: http://www.deloitte.com/view/en_US/us/Industries/health-care-providers/center-for-health-solutions. [Google Scholar]

- 8.HealthIT. [Accessed April 5, 2013]; Available at: http://www.healthit.gov.

- 9.Fox S. Online Health Search 2006. Washington, DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project; 2006. [Accessed April 3, 2013]. Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2006/Online-Health-Search-2006.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fox S, Duggan M. Health Online 2013. Washington, DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project; 2013. [Accessed March 11, 2013]. Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2013/Health-online.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lebo H. The Digital Future Report 2011: Surveying the Digital Future, Year Ten. Los Angeles, CA: USC Annenberg School Center for the Digital Future; 2011. [Accessed April 8, 2013]. Available at: http://www.digitalcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/2011_digital_future_report-year10.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Undem T. Consumers and Health Information Technology: A National Survey. Oakland, CA: California HealthCare Foundation; 2010. [Accessed February 26, 2013]. Available at: http://www.chcf.org/publications/2010/04/consumers-and-health-health-information-technology-a-national-survey. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Powell J, Inglis N, Ronnie J, Large S. The characteristics and motivations of online health information seekers: cross-sectional survey and qualitative interview study. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13:e20. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fox S. The Social Life of Health Information. Washington, DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project; 2009. [Accessed March 15, 2013]. Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2009/8-The-Social-Life-of-Health-Information.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sec¸kin G. Cyber patients surfing the medical web: Computer-mediated medical knowledge and perceived benefits. Comput Hum Behav. 2010;26:1694–1700. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rideout V, Newman T. eHealth and the Elderly: How Seniors Use the Internet for Health Information, Key Findings from a National Survey of Older Americans. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2005. [Accessed March 15, 2013]. Available at: http://www.kff.org/entmedia/upload/e-Health-and-the-Elderly-How-Seniors-Use-the-internet-for-Health-Information-Key-Findings-From-a-National-Survey-of-Older-Americans-Survey-Report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 17.WebMD. [Accessed March 27, 2013]; Available at: http://www.webmd.com/.

- 18.Chapman LS, Rowe D, Witte K. eHealth portals: who uses them and why? Am J Health Promot. 2010;24:TAHP1–TAHP7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moiduddin A, Kronstadt J, Sellheim W. Consumer Use of Computerized Applications to Address Health and Health Care Needs. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2009. 49 pp. Contract No.: HHSP233200800001T. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ybarra M, Suman M. Reasons, assessments and actions taken: sex and age differences in uses of Internet health information. Health Educ Res. 2008 Jun;23:512–521. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koch-Weser S, Bradshaw YS, Gualtieri L, Gallagher SS. The Internet as a health information source: findings from the 2007 Health Information National Trends Survey and implications for health communication. J Health Commun. 2010;15:279–293. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.522700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCray A. Promoting health literacy. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2005;12:152–163. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stevenson FA, Kerr C, Murray E, Nazareth I. Information from the Internet and the doctor-patient relationship: the patient perspective—a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2007;8:47. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-8-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hou J, Shim M. The role of provider-patient communication and trust in online sources in Internet use for health-related activities. J Health Commun. 2010;15:186–199. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.522691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kutner M, Greenberg E, Jin Y, Paulsen C. The Health Literacy of America’s Adults: Results From the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics; 2006. [Accessed April 3, 2013]. Available at: http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2006/2006483.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fox S. Family Caregivers Online. Washington, DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project; 2012. [Accessed March 15, 2013]. Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2012/Caregivers-online.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ressler PK, Bradshaw YS, Gualtieri L, Chui KK. Communicating the experience of chronic pain and illness through blogging. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14:e143. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fox S. Peer-to-Peer Healthcare. Washington, DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project; 2011. [Accessed April 8, 2013]. Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2011/P2PHealthcare.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ziebland S, Wyke S. Health and illness in a connected world: how might sharing experiences on the internet affect people’s health? Milbank Q. 2012;90:219–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2012.00662.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wicks P, Massagli M, Frost J, Brownstein C, Okun S, Vaughan T, Bradley R, Heywood J. Sharing health data for better outcomes on PatientsLikeMe. J Med Internet Res. 2010;12:e19. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu X, Bell R, Kravitz R, Orrange S. The prepared patient: information seeking of online support group members before their medical appointments. J Health Commun. 2012;17:960–978. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2011.650828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tustin N. The role of patient satisfaction in online health information seeking. J Health Commun. 2010;15:3–17. doi: 10.1080/10810730903465491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ball MJ, Smith C, Bakalar RS. Personal health records: empowering consumers. J Healthc Inf Manag. 2007;21:76–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee SY, Hawkins R. Why do patients seek an alternative channel? The effects of unmet needs on patients’ health-related Internet use. J Health Commun. 2010;15:152–166. doi: 10.1080/10810730903528033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.World Health Organization. mHealth: New Horizons for Health Through Mobile Technologies. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [Accessed March 29, 2013]. Available at: http://www.who.int/goe/publications/goe_mhealth_web.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 36.PWC, Economist Intelligence Unit. Emerging mHealth: Paths for Growth. PricewaterhouseCoopers LLC; Jun, 2012. [Accessed February 12, 2013]. Available at: http://www.pwc.com/en_GX/gx/healthcare/mhealth/assets/pwc-emerging-mhealth-full.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sarasohn-Kahn J. How Smartphones Are Changing Health Care for Consumers and Providers. Oakland, CA: California HealthCare Foundation; 2010. [Accessed March 15, 2013]. Available at: http://www.chcf.org/publications/2010/04/how-smartphones-are-changing-health-care-for-consumers-and-providers. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kratzke C, Cox C. Smartphone technology and apps: rapidly changing health promotion. Int Electr J Health Educ. 2012;15:72–82. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilson S. Open Mobile: The Growth Era Accelerates, The Deloitte Open Mobile Survey 2012. Deloitte Research: 2011. [Accessed April 3, 2013]. Available at: http://www.deloitte.com/assets/Dcom-Norway/Local%20Assets/Documents/Publikasjoner%202012/deloitte_openmobile2012.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Drazen E. Personal Health Records: A True ‘‘Personal Health Record’’? Not Really … Not Yet. Computer Sciences Corporation; 2011. [Accessed March 27, 2013]. Available at: http://www.csc.com/health_services/insights/61137-personal_health_records_a_true_personal_health_record_not_really_not_yet. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Emani S, Yamin CK, Peters E, Karson AS, Lipsitz SR, Wald JS, Williams DH, Bates DW. Patient perceptions of a personal health record: a test of the diffusion of innovation model. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14:e150. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. [Accessed April 5, 2013]; http://www.healthit.gov/patients-families/electronic-health-records-infographic.

- 43.Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The Value of Personal Health Records and Portals to Engage Consumers and Improve Quality. Princeton, NJ: The Foundation; 2012. [Accessed March 23, 2013]. Available at: http://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/issue_briefs/2012/rwjf400251. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Keckley P, Coughlin S, Eselius L. Survey of Health Care Consumers in the United States: Key Findings, Strategic Implications. Washington, DC: Deloitte Center for Health Solutions; 2011. [Accessed March 5, 2013]. Available at: http://www.deloitte.com/assets/Dcom-UnitedStates/Local%20Assets/Documents/US_CHS_2011ConsumerSurveyinUS_062111.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zulman DM, Nazi KM, Turvey CL, Wagner TH, Woods SS, An LC. Patient interest in sharing personal health record information: a web-based survey. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:805–810. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-12-201112200-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Westin A. Making IT Meaningful: How Consumers Value and Trust Health IT. Washington, DC: National Partnership for Women & Families; 2012. [Accessed April 12, 2013]. Available at: http://www.nationalpartnership.org/site/PageServer?pagename=issues_health_IT_survey. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seidman J, Eytan T. Helping Patients Plug In: Lessons in the Adoption of Online Consumer Tools. Oakland, CA: California HealthCare Foundation; 2008. [Accessed April 2, 2013]. Available at: http://www.chcf.org/publications/2008/06/helping-patients-plug-in-lessons-in-the-adoption-of-online-consumer-tools. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Westin A. Americans Overwhelmingly Believe Electronic Personal Health Records Could Improve Their Health. New York, NY: Markle Foundation; 2008. [Accessed March 23, 2013]. Available at: http://www.markle.org/publications/401-americans-overwhelmingly-believe-electronic-personal-health-records-could-improve-t. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wolters Kluwer Health. Wolters Kluwer Health Quarterly Poll: Consumerization of Healthcare. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health; 2012. [Accessed April 8, 2013]. Available at: http://www.wolterskluwerhealth.com/News/. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gibbons C. Use of health information technology among racial and ethnic underserved communities. Perspect Health Inf Manag. 2011;8:1f. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sarkar U, Karter AJ, Liu JY, Adler NE, Nguyen R, López A, Schillinger D. Social disparities in internet patient portal use in diabetes: evidence that the digital divide extends beyond access. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18:318–321. doi: 10.1136/jamia.2010.006015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Feeley TW, Shine KI. Access to the medical record for patients and involved providers: transparency through electronic tools. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:853–854. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-12-201112200-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Turley M, Garrido T, Lowenthal A, Zhou YY. Association between personal health record enrollment and patient loyalty. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18:e248–e253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim EH, Stolyar A, Lober WB, Herbaugh AL, Shinstrom SE, Zierler BK, Soh CB, Kim Y. Usage patterns of a personal health record by elderly and disabled users. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2007;11:409–413. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Healthcare IT News. [Accessed February 28, 2013]; Available at: http://www.healthcareitnews.com/news/kaiser-phr-sees-4-million-sign-most-active-portal-date.

- 56.Kaiser Permanente. [Accessed March 15, 2013]; Available at: https://healthy.kaiserpermanente.org/html/kaiser/index.shtml.

- 57.My HealtheVet. [Accessed April 1, 2013]; Available at: https://www.myhealth.va.gov/.

- 58.HealthIT. [Accessed April 5, 2013]; Available at: http://www.healthit.gov/patients-families/maintain-your-medical-record.

- 59.Bayer E. Trends and Innovations in Health Information Technology, An Update from America’s Health Insurance Plans. Washington, DC: AHIP Center for Policy and Research; 2008. [Accessed February 8, 2013]. Available at: http://www.ahip.org/Innovations-in-Health-IT/. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gaylin DS, Moiduddin A, Mohamoud S, Lundeen K, Kelly JA. Public attitudes about health information technology, and its relationship to health care quality, costs, and privacy. Health Serv Res. 2011;46:920–938. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01233.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bishop L, Holmes B, Kelly C. National Consumer Health Privacy Survey 2005. Oakland, CA: The California HealthCare Foundation; 2005. [Accessed April 4, 2013]. Available at: http://www.chcf.org/publications/2005/11/national-consumer-health-privacy-survey-2005. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Keckley P, Coughlin S. 2012 Survey of U.S. Health Care Consumers: Five-Year Look Back. Washington, DC: Deloitte Center for Health Solutions; 2012. [Accessed March 15, 2013]. Available at: http://dupress.com/articles/2012-survey-of-u-s-health-care-consumers-five-year-look-back/?id=us:exl:dcm:2012. [Google Scholar]

- 63.U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. [Accessed March 5, 2013]; Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/hipaa/administrative/breachnotificationrule/breachtool.html.

- 64.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Keselman A, Logan R, Smith CA, Leroy G, Zeng-Treitler Q. Developing informatics tools and strategies for consumer-centered health communication. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2008;15:473–483. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sun GH. The digital divide in Internet-based patient education materials. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;147:855–857. doi: 10.1177/0194599812456153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Alpay L, Verhoef J, Xie B, Te’eni D, Zwetsloot-Schonk JH. Current challenge in consumer health informatics: bridging the gap between access to information and information understanding. Biomed Inform Insights. 2009;2:1–10. doi: 10.4137/bii.s2223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kellermann AL, Jones SS. What it will take to achieve the as-yet-unfulfilled promises of health information technology. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:63–68. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rosemblat G, Tse T, Gemoets D, Gillen J, Ide N. Supporting access to consumer health information across languages. Proceedings of the 8th International ISKO Conference; London, England. 2005. pp. 315–321. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sarkar U, Karter AJ, Liu JY, Adler NE, Nguyen R, Lopez A, Schillinger D. The literacy divide: health literacy and the use of an Internet-based patient portal in an integrated health system-results from the diabetes study of northern California (DISTANCE) J Health Commun. 2010;15:183–196. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.499988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Beard L, Schein R, Morra D, Wilson K, Keelan J. The challenges in making electronic health records accessible to patients. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2012;19:116–120. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Segall N, Saville JG, L’Engle P, Carlson B, Wright MC, Schulman K, Tcheng JE. Usability evaluation of a personal health record. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2011;2011:1233–1242. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Finkelstein J, Knight A, Marinopoulos S, Gibbons MC, Berger Z, Aboumatar H, Wilson RF, Lau BD, Sharma R, Bass EB. Enabling Patient-Centered Care Through Health Information Technology0. Rockville, MD: Jun, 2012. [Accessed February 22, 2013]. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/evidence-based-reports/er206-abstract.html#Report. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Saparova D. Motivating, influencing, and persuading patients through personal health records: a scoping review. Perspect Health Inf Manag. 2012;9:1f. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gibbs N. Your life is fully mobile. [Accessed February 26, 2013];Time Mag. 2012 180(9):32–39. Available at: http://techland.time.com/2012/08/16/your-life-is-fully-mobile/. [Google Scholar]

- 76.King D, Greaves F, Exeter C, Darzi A. ‘Gamification’: influencing health behaviors with games. J R Soc Med. 2013;106:76–78. doi: 10.1177/0141076813480996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.PwC Health Research Institute. Customer Experience in Healthcare: The Moment of Truth. Pricewater-houseCoopers LLC; 2012. Jul, [Accessed February 12, 2013]. Available at: http://www.pwc.com/us/en/health-industries/publications/health-care-customer-experience.jhtml. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bartolini E, McNeill N. Getting to Value: Eleven Chronic Disease Technologies to Watch. Cambridge, MA: NEHI; 2012. [Accessed April 4, 2013]. pp. 21–23. Available at: http://www.nehi.net/publications/72/getting_to_value_eleven_chronic_disease_technologies_to_watch. [Google Scholar]

FURTHER READING

- Eysenbach G, Kohler C. What is the prevalence of health-related searches on the World Wide Web? Qualitative and quantitative analysis of search engine queries on the Internet. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2003;2003:225–229. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox S. The Engaged e-Patient Population. Washington, DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project; 2008. [Accessed March 28, 2013]. Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2008/The-Engaged-Epatient-Population.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Lafky DB, Horan TA. Prospective personal health record use among different user groups: results of a multi-wave study. 41st Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences; Waikoloa, HI. 2008. p. 233. [Google Scholar]

- Manhattan Research. Cybercitizen Health v8.0. New York, NY: Manhattan Research; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hou SI. Health Literacy Online: A Guide to Writing and Designing Easy-to-Use Health Web Sites. Health Promot Pract. 2012;13:577–580. doi: 10.1177/1524839912446480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Or CK, Karsh BT, Severtson DJ, Burke LJ, Brown RL, Brennan PF. Factors affecting home care patients’ acceptance of a web-based interactive self-management technology. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18:51–59. doi: 10.1136/jamia.2010.007336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitzman ER, Kelemen S, Kaci L, Mandl KD. Willingness to share personal health record data for care improvement and public health: a survey of experienced personal health record users. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2012;12:39. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-12-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]