Abstract

Killer lymphocyte granzyme (Gzm) serine proteases induce apoptosis of pathogen-infected cells and tumor cells. Many known Gzm substrates are nucleic acid binding proteins, and the Gzms accumulate in the target cell nucleus by an unknown mechanism. Here we show that human Gzms bind to DNA and RNA with nanomolar affinity. Gzms cleave their substrates most efficiently when both are bound to nucleic acids. RNase treatment of cell lysates reduces Gzm cleavage of RNA binding protein (RBP) targets, while adding RNA to recombinant RBP substrates increases in vitro cleavage. Binding to nucleic acids also influences Gzm trafficking within target cells. Pre-incubation with competitor DNA and DNase treatment both reduce Gzm nuclear localization. The Gzms are closely related to neutrophil proteases, including neutrophil elastase (NE) and cathepsin G (CATG). During neutrophil activation, NE translocates to the nucleus to initiate DNA extrusion into neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), which bind NE and CATG. These myeloid cell proteases, but not digestive serine proteases, also bind DNA strongly and localize to nuclei and NETs in a DNA-dependent manner. Thus, high affinity nucleic acid binding is a conserved and functionally important property specific to leukocyte serine proteases. Furthermore, nucleic acid binding provides an elegant and simple mechanism to confer specificity of these proteases for cleavage of nucleic acid binding protein substrates that play essential roles in cellular gene expression and cell proliferation.

Introduction

Cytotoxic T lymphocytes and natural killer cells eliminate virus-infected cells and tumor cells by releasing the granzyme (Gzm) serine proteases and perforin (PFN) from cytotoxic granules into the immunologic synapse formed with the cell destined for elimination (1). GzmA and GzmB, the most abundant and best studied Gzms, are delivered to the target cell cytosol by PFN and rapidly concentrate in the target cell nucleus by an unknown mechanism and induce independent programs of cell death (2, 3). To orchestrate cell death in diverse types of target cells, the Gzms cleave multiple substrates, likely numbering in the hundreds, within the cytosol, nucleus, and mitochondria (1, 4). DNA and RNA binding proteins are highly represented in the set of Gzm substrates. All but 1 of the 17 substrates of GzmA that have been carefully validated bind to DNA, RNA or chromatin (1, 4). A recent proteomics study that profiled GzmA substrates in isolated nuclei identified 44 candidate substrates, of which 33 were RNA binding proteins (RBPs), including 12 heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (hnRNP) (4). The remaining 11 candidate substrates were mostly DNA binding proteins. In some cases, the nucleic acid appears to play an important role in the Gzm/target interaction. GzmA cleavage of histone H1 and binding to PARP-1 depends on the presence of DNA (5, 6). All five of the human Gzms cleave hnRNP K in an RNA-dependent manner (7). Gzm cleavage of viral and host nucleic acid binding proteins also plays an important role in controlling viral infection (8, 9). Thus many of the substrates of GzmA and GzmB are nucleic acid binding proteins that are physiologically important for cytotoxicity or the control of viral infections.

Although serine proteases have a high degree of sequence similarity, the Gzms are most closely related to a group of myeloid cell granule proteases involved in microbial defense. These immune proteases include the neutrophil proteases neutrophil elastase (NE) and cathepsin G (CATG) (10). When neutrophils are activated, they can ensnare and kill microbes in neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), which are formed by nuclear DNA in a unique, non-apoptotic cell death mechanism, called NETosis (11). NE participates in NETosis by translocating to the neutrophil nucleus where it cleaves histones (12). Histone cleavage promotes chromatin decondensation, which precipitates the extrusion of nuclear DNA through the cell membrane. The extruded DNA is coated with histones, antimicrobial peptides, NE and CATG (13).

The aim of this study was to explore further the role of nucleic acids in mediating Gzm/substrate interactions and trafficking. We find that RNA enhances in vitro cleavage of RBP substrates, but not non-RBP substrates. We show that Gzms directly bind RNA and DNA with nanomolar affinity. NE and CATG also bind nucleic acids with high affinity, while digestive serine proteases do not. In the presence of competitor DNA, the leukocyte serine proteases do not localize to nuclei and NETs. Together, our findings indicate that nucleic acid binding is a conserved and functionally important property of leukocyte serine proteases that directs them to and enhances their cleavage of nucleic acid binding protein targets.

Materials and Methods

Abs

The following abs were used at the indicated final concentration or dilution: mouse monoclonal abs to hnRNP U (Santa Cruz; 3G6; 0.2 μg/ml), hnRNP A1 (Sigma; 4B10; 2 μg/ml), lamin B1 (Calbiochem; 101-B7; 1/1,000), α-tubulin (Sigma; B-5-1-2; 1/1,000), G3BP1 (BD; 23/G3BP; 0.25 μg/ml), hnRNP C1/C2 (Sigma; 4F4; 0.4 μg/ml), β-actin (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank; 1/1,000), HuR (Santa Cruz; 3A2; 0.2 μg/ml); rabbit antisera to HMGB2 (Abcam; 1/1,000), ICAD (Abcam; 0.5 μg/ml), NE (Abcam; 1 μg/ml); DDX5 (Abcam; 0.5 μg/ml). Secondary abs were sheep anti-mouse-HRP (GE; 1/2,500), donkey anti-rabbit-HRP (GE; 1/2,500), donkey anti-goat-HRP (GE, 1/2,500), goat anti-rabbit AF488 (Invitrogen; 1/200), donkey anti-mouse Cy3 (Jackson ImmunoResearch 715-165-150; 1:200). Normal rabbit IgG (Cell Signaling 2729; 1 μg/ml) was used as an isotype control for immunofluorescence.

Proteins

Human GzmA and GzmB expression plasmids (4) were transfected into HEK 293T cells by calcium phosphate precipitation. The transfected cells were grown in serum-free ExCell 293 medium (Sigma) for 4 days. Recombinant granzymes were purified from the culture supernatants by immobilized metal affinity chromatography using Nickel-NTA (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Eluted granzymes were treated with enterokinase (0.05 IU/mL supernatant; Sigma) for 16 hours at room temperature. Active Gzms were finally purified on an S column, concentrated, and quality tested as previously described (14). GST-tagged HuR, hnRNPC1, and LMNB1 were expressed and purified as described (4). H1 (NEB M2501S) and caspase 3 (Enzo – ALX-201-059-U025) were purchased. Other serine proteases were NE (Athens Research and Technology, Athens, GA 16-14-051200), PE (Millipore 324682), CATG (Athens Research and Technology 16-14-030107) and trypsinogen (Sigma T1143). Proteins were fluorescently labeled with Alexa Fluor® 488 (AF488) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen A30006).

In vitro cleavage in cell lysates

Whole cell lysates were made from 106 HeLa cells suspended in 1 mL of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl) by alternating freezing in an ethanol/dry ice bath and thawing at 37°C three times. Cell debris was pelleted by centrifugation (16,000 x g for 10 min at 4°C). The supernatant was divided, and half was treated with RNase A/T1 (Thermo) at a concentration of 325 U/mL for 30 min at 37°C. RNaseOUT (Invitrogen) was added at a concentration of 1000 U/mL to the remaining half. The lysates were then treated with the indicated amounts of Gzms in a volume of 60 μL for 15 min at 37°C. In some cases, GzmB was incubated with varying amounts of salmon sperm DNA on ice for 30 min before addition to lysates. The cleavage reaction was stopped by adding 5x SDS-loading buffer and boiling at 95°C for 5 min. For caspase 3 experiments, lysates were incubated with or without 1 unit of recombinant capsase 3 for 1 hour before stopping the reaction. Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblot.

In vitro cleavage of recombinant proteins

In vitro cleavage was performed in 100 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5). Each protein was first incubated in the indicated concentration of HeLa cell total RNA or salmon sperm DNA for 20 min and then incubated with 50 nM GzmB for 15 min (hnRNP C), 50 nM GzmB for 30 min (LMNB1), 200 nM GzmA for 20 min (H1) or 5 nM NE for 10 min (H1). Total HeLa cell RNA was purified with Trizol (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The final concentrations of hnRNP C, LMNB1 and H1 were 333 nM, 1 nM and 400 nM respectively. For HuR cleavage, RNA oligos were diluted to 10 μM, heated at 70°C for 10 min and cooled on ice. 400 nM recombinant GST-tagged HuR was incubated with or without 200 nM recombinant GzmB. The cleavage reactions were performed in the presence of 3 ng/μL total HeLa RNA, AU RNA or BB94 RNA at the indicated molar ratios and incubated in a total volume of 40 μL at 37°C for 30 min. Cleavage reactions were stopped by adding 5X SDS loading buffer and boiling for 5 min. Cleavage was assayed by immunoblot or silver staining (Invitrogen SilverQuest kit).

Protease localization in permeabilized HeLa cells

HeLa cells were obtained from ATCC and maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penicillin G, 100 μg/mL streptomycin sulfate, 6 mM HEPES, 1.6 mM L-glutamine and 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol. HeLa cells were grown overnight on 12 mm coverslips, then fixed for 10 min at RT in 2% formaldehyde, then permeabilized for 10 min in methanol on dry ice. In some experiments the cells were treated with DNase I (NEB) or RNase A/T1 (Thermo) at a 1:50 dilution for 4 hours at RT before blocking. The cells were blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS for 1 hour at RT, coverslips were incubated with blocking buffer containing salmon sperm DNA or no DNA for 30 min on ice and then incubated at RT for 1 hour with 100 nM AF488-labeled serine proteases. The cover slips were then washed and stained with 4 μg/mL DAPI in PBS and mounted on slides (VWR 48311-703) using polyvinyl alcohol (Sigma P-8136) aqueous mounting medium. Cells were imaged using an Axiovert 200M microscope (Pan Apochromat, 1.4 NA; Carl Zeiss). Images were analyzed with SlideBook 4.2 (Intelligent Imaging Innovations Inc.).

Neutrophil isolation and activation

Human studies were reviewed and approved by the Harvard Committee on the Use of Human Subjects (IRB-P00005698). Neutrophils were isolated from the blood of de-identified healthy donors by density gradient centrifugation as described (15). The neutrophil layer was washed with HBSS and resuspended at 106 cells/mL in RPMI. Neutrophils (2.5×105) were incubated at 37°C for 15 min on 12 mm coverslips in 24-well flat-bottom cell culture plates and then treated in 500 μl RPMI for 3 hours with 100 nM PMA (phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate, Sigma P1585). In some experiments, 100 nM AlexaFluor-488 (AF488)-labeled protease and/or salmon sperm DNA (Sigma D7656) were added just prior to adding PMA. Treated cells were fixed in PBS containing 4% formaldehyde. For immunofluorescence staining of endogenous NE, the fixed cells were incubated with primary ab or rabbit antiserum control for 1 hour at RT, washed three times in PBS, and then incubated in secondary ab (AF488-labeled goat α-rabbit IgG) for 1 hour at RT. The cells were washed, stained with DAPI, and mounted as above.

Gene Ontology and phylogenetic analysis of serine proteases

We analyzed the candidate targets of human GzmA (16) and GzmB (17) identified by proteomics using the FuncAssociate tool (18) on default settings. Top gene ontology (GO) terms were ranked by the sum of the −log10(p) values for enrichment of targets of each enzyme. All human proteins having the GO term “serine-type peptidase activity” (GO:0008236) were identified with AmiGO (19). Of these proteins, the manually annotated and reviewed Swiss-Prot sequences were downloaded using the UniProt retrieve tool (20). The sequences were trimmed to focus on their protease domains and exclude spurious alignment of other protein domains in multidomain proteins. The ClustalW2 (21) multiple sequence alignment and phylogeny tools were used with default parameters to construct a phylogenetic tree. Phylogeny was visualized with the EvolView web tool (22).

Fluorescence polarization (FP) oligonucleotides

The following FAM-labeled oligonucleotides were used for FP, all from Integrated DNA Technologies:

BB94 DNA: 5′TCTGTGAGTTGAACGCACACATCACAAAGGAG-FAM-3′

dA(30): 5′AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA-FAM-3′

dC(30): 5′CCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCC-FAM-3′

dT(30): 5′TTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT-FAM-3′

rU(30): 5′UUUUUUUUUUUUUUUUUUUUUUUUUUUUUU-FAM-3′

BB94 RNA: 5′UCUGUGAGUUGAACGCACACAUCACAAAGGA-FAM-3′

AU RNA: 5′CCCAAGCUUAUUUAUUUAUUUAUUGCAGGUC-FAM-3′

Fluorescence polarization assays

FAM-labeled oligonucleotides were used at 10 nM, and binding reactions were performed in a total volume of 20 μL. Proteins and oligos were diluted in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl and 2.5 mM MgCl2. For RNA oligos, RNAseOUT was added to a final concentration of 1 U/μL. Diluted RNA oligos were heated to 70°C for 10 min prior to use. In the salt concentration assay, protein concentration was fixed (100 nM) and either NaCl or KCl was added to the assay buffer at the indicated final concentrations. Samples were equilibrated in 384-well black polystyrene assay plates (Corning 3575) for 20 min at room temperature, and polarization was determined using a Synergy 2 Microplate Reader and Gen5 Data Analysis Software (BioTek).

Fluorescence polarization data analysis

The apparent equilibrium Kd was determined from fitting the data to a sigmoidal dose-response function using JMP Pro 10 (JMP Statistical Discovery Software from SAS). The apparent Kd was determined for each protein/nucleic acid interaction using the equation , where f is the fraction bound or the polarization value, [P] is the protein concentration, b is the equilibrium Kd, a is the Hill coefficient, d is the maximum polarization and c is the minimum polarization (23). Each experiment was performed at least in duplicate. The average and standard error of the polarization value for each protein concentration was calculated from at least 10 independent samples.

Oligo(dT) pulldown

120 μl Oligo(dT)25 Dynabeads (Invitrogen 61002) and 10 μl Protein G Dynabeads (Invitrogen 10004D) were washed three times in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 100 nM NaCl. The beads were blocked for 30 min at RT in the same buffer containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Sigma A9647). Following blocking, half of the Oligo(dT)25 Dynabeads were treated at RT for 30 min with 25 U Benzonase® Nuclease (Sigma E1014), the other half was left untreated. After this incubation, the beads were incubated with 120 μl of protein (final concentration 1 μM) in blocking buffer for 30 min at room temperature. The beads were washed three times and protein was eluted by boiling samples for 3 min in 30 μl SDS loading buffer. Samples were electrophoresed through a 12% polyacrylamide denaturing gel and visualized by Coomassie staining.

Results

Predicted targets of GzmA and GzmB are enriched for nucleic acid binding proteins

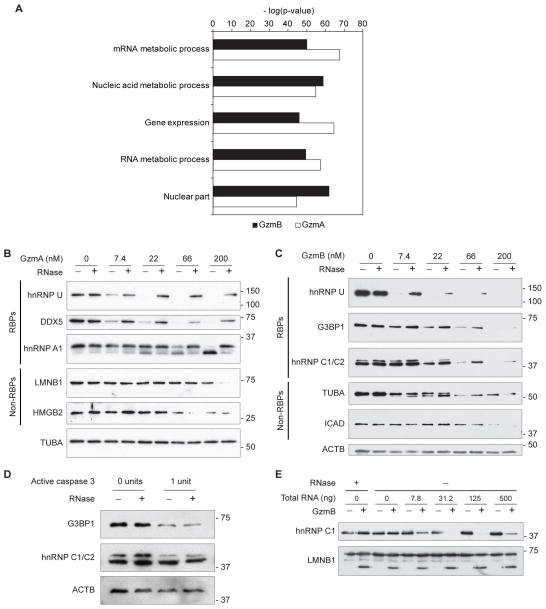

Because the Gzms concentrate in the nucleus of target cells, we hypothesized that proteins that function in the nucleus might be over-represented amongst Gzm substrates. Two proteomics studies identified candidate GzmA and GzmB substrates without bias by analyzing Gzm-incubated cell lysates for novel cleavage products (16, 17). We analyzed these target lists using the FuncAssociate gene ontology (GO) tool (18) for over-represented GO terms in both GzmA and GzmB datasets (Fig. 1A and Supplemental Table I). Proteins with nucleic acid-related GO terms were the most highly enriched categories, when analyzed for each Gzm individually or together. The top 7 GO terms for both Gzms (mRNA metabolic process, nucleic acid metabolic process, gene expression, RNA metabolic process, nuclear part, nucleotide metabolic process, RNA binding) were highly significantly over-represented (P-values of ~10−50 for each Gzm). This analysis suggested that Gzms might have a special preference for nucleic acid binding, especially RBP, substrates.

Figure 1. RBP target cleavage by Gzms is enhanced by RNA.

(A) GO analysis of GzmA and GzmB targets. Nucleic acid binding proteins are highly enriched. Cell lysates or recombinant proteins were incubated with RNase or the indicated concentration of total RNA followed by incubation with Gzms. The reactions were analyzed by immunoblot. (B,C) RNase treatment of HeLa cell lysates reduced cleavage by GzmA (B) and GzmB (C) of RBP targets, but not non-RBP targets. Results in B and C are representative of at least 3 independent experiments. (D) RNase treatment of HeLa cell lysates did not affect cleavage of RBP targets by active caspase 3. (E) GzmB cleavage of recombinant hnRNP C1, but not recombinant LMNB1, was enhanced by exogenous total RNA. Results in D and E are representative of 2 independent experiments.

RNA promotes GzmA and GzmB cleavage of RNA-binding proteins

We first asked whether RNA enhances Gzm RBP cleavage by comparing Gzm cleavage of RBPs in whole cell lysates depleted of RNA. HeLa cell lysates were pretreated or not with a mixture of RNase A and T1 before a 15 minute incubation with varying concentrations of recombinant human GzmA or GzmB. The samples were then immunoblotted for known GzmA and GzmB targets. All 3 GzmA RBP targets analyzed (hnRNP U, DDX5, hnRNP A1) were cleaved less efficiently in RNase-treated samples (Fig. 1B). Similarly, cleavage of RBP targets of GzmB (hnRNP U, G3BP1, hnRNP C1/C2) was reduced by removing RNA (Fig. 1C). In contrast, non-RBP targets (LMNB1, HMGB2, TUBA, ICAD) were cleaved equally or more efficiently in RNase-treated lysates, suggesting that Gzm target preference is altered to favor non-RBPs in the absence of RNA. This effect is not universal to cytotoxic proteases as RNase treatment did not affect caspase 3 cleavage of hnRNP C1/C2 and G3BP1 RBP substrates (Fig. 1D). We next tested whether adding HeLa cell RNA would alter in vitro GzmB cleavage of recombinant hnRNP C1 and LNMB1. The RBP hnRNP C1 was more efficiently cleaved in the presence of added RNA, while cleavage of the non-RBP LMNB1 was unaffected (Fig. 1E). These results indicate that RNA enhances Gzm cleavage of RBP targets. Of note, although the highest concentration of RNA still enhanced cleavage, GzmB cleavage of hnRNP C1 was more efficient when less RNA was added.

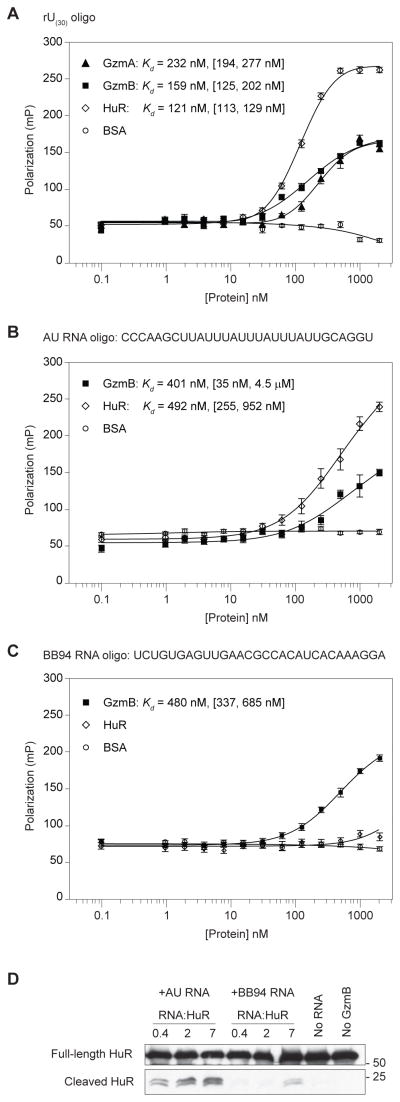

The Gzms bind to RNA with nanomolar affinity

Because RNA enhanced Gzm activity against RBPs, we hypothesized that the Gzms might bind to RNA to direct them to RBP targets. We tested RNA binding by fluorescence polarization (FP), a technique widely used to measure protein-nucleic acid interactions (24), using a 3′ FAM-labeled oligouridylate homopolymer (rU30). As a positive control, we measured RNA binding of human antigen R (HuR), a GzmB substrate that binds to AU-rich RNA sequences (25). GzmA, GzmB and HuR all bound to rU30 with high affinity, while the negative control protein BSA did not bind (Fig. 2A). The apparent equilibrium dissociation constants (Kd) between all three purified proteins and the rU30 oligo determined by FP were in the nanomolar range (Table I).

Figure 2. Gzms directly bind RNA.

FP assays with purified Gzms and RNA. (A) GzmA and GzmB bound to a FAM-labeled 30-nt RNA (rU30). (B) GzmB and HuR bind a 30 nt RNA containing an AU rich sequence (AU RNA). (C) GzmB, but not HuR, binds a length-matched control RNA (BB94 RNA). The mean polarization values ± sem are plotted and the apparent Kd with 95% confidence interval in brackets is shown. Results are representative of at least three independent experiments. (D) GzmB cleaves HuR, an RBP target, most efficiently when it is bound to RNA. GST-tagged HuR protein was incubated with indicated molar ratios of AU RNA or BB94 RNA, and GzmB was then added for 30 min. HuR cleavage was detected by immunoblot probed for GST.

Table I.

Protein – nucleic acid interactions measured by FP in this study. The apparent dissociation constant (Kd) with 95% confidence interval in brackets is given for each binding interaction.

| Oligo | Protein | Kd (nM) |

|---|---|---|

| rU(30) | GzmA | 232 [194, 277] |

| GzmB | 159 [125, 202] | |

| HuR | 121 [113, 129] | |

|

| ||

| AU RNA | GzmA | 401 [35 nM, 4.5 μM] |

| GzmB | 651 [157 nM, 2.7 μM] | |

| NE | 602 [304 nM, 1.2 μM] | |

| CATG | 165 [139, 197] | |

| HuR | 492 [255, 952] | |

|

| ||

| BB94 ssRNA | GzmA | 1.6 μM [188 nM, 15.2 μM] |

| GzmB | 480 [337, 685] | |

| HuR | 4.8 μM [16 nM, 1465.9 μM] | |

|

| ||

| BB94 ssDNA | GzmA | 122 [95, 158] |

| GzmB | 35 [31, 40] | |

| NE | 272 [219, 339] | |

| CATG | 22 [17, 29] | |

| Histone H1 | 10 [8, 12] | |

|

| ||

| BB94 dsDNA | GzmA | 120 [106, 136] |

| GzmB | 161 [112, 231] | |

| NE | 607 [516, 712] | |

| CATG | 35 [24, 52] | |

| Histone H1 | 9 [7, 13] | |

|

| ||

| dC(30) | GzmA | 91 [65, 127] |

| GzmB | 175 [140, 219] | |

|

| ||

| dT(30) | GzmA | 48 [42, 55] |

| GzmB | 45 [26, 78] | |

GzmB cleavage of HuR is enhanced by HuR binding to RNA

Because HuR preferentially binds AU-rich sequences, we used its specificity to assess the effect of substrate binding to RNA on GzmB cleavage. We compared GzmB cleavage of HuR in the presence of an AU-rich target sequence (AU RNA) (26) that both HuR and GzmB bind with similar affinity (Fig. 2B and Table I) and in the presence of a control sequence (BB94) that binds well only to GzmB (Fig. 2C and Table I). Formation of the cleavage product was enhanced by AU RNA, but only minimally increased by BB94 RNA (Fig. 2D). These results suggest that RBP targets are optimally cleaved by Gzms when both the target and Gzm interact with RNA.

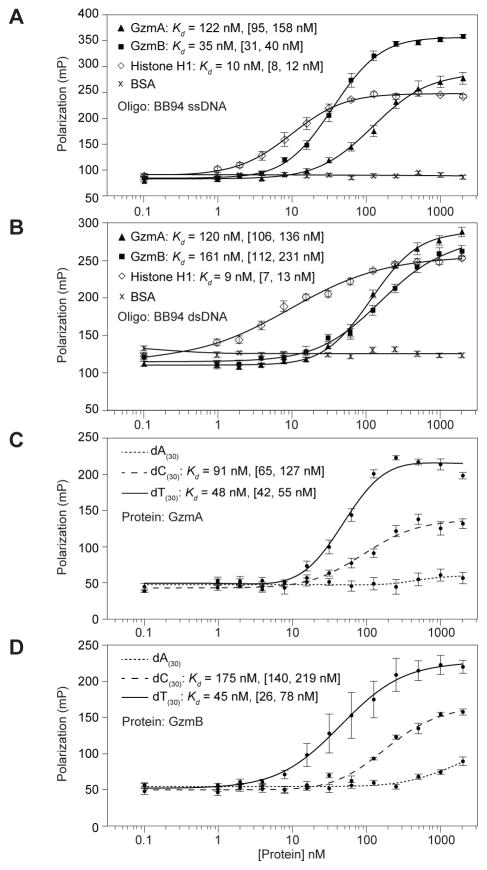

Gzms bind DNA with nanomolar affinity

Because the Gzms bind to RNA and cleave many DNA binding proteins, we asked whether they could also bind DNA. We used FP to measure the binding of GzmA and GzmB to a single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) oligonucleotide of the same sequence as BB94 RNA (Fig. 3A). Both GzmA and GzmB bound ssDNA with nanomolar Kd (Table 1). GzmB (Kd = 35 nM, 95% CI [31,40]) bound ssDNA almost as strongly as histone H1 (H1) (Kd = 10 nM, 95% CI [8, 12]), similar to reported values (27)). GzmA binding was somewhat weaker (Kd = 122 nM, 95% CI [95, 158]). Both Gzms also bound to a double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) oligonucleotide containing the same BB94 sequence with nanomolar affinities (Fig. 3B). To determine if Gzm binding might have a sequence preference, we performed FP assays with ssDNA homopolymers (dA30, dT30 and dC30). Oligo(dG) was not tested because it tends to form higher order structures and aggregate. Both Gzms bound dT30 > dC30 with nanomolar affinity, but only weakly bound to dA30 (Fig. 3C and 3D). This suggests that the Gzms bind preferentially to pyrimidines. These assays were performed in buffer containing 100 mM NaCl. Since many protein-DNA complexes are sensitive to salt concentration, we performed FP assays over a range of NaCl and KCl concentrations, while holding the GzmB and nucleic acid concentration constant. Although binding decreased at higher salt concentrations, binding of GzmB to DNA and RNA remained strong at physiological concentrations (150 mM NaCl or KCl) (Supplemental Fig. 1).

Figure 3. GzmA and GzmB bind DNA with nanomolar affinity.

(A,B) The binding of a single-stranded (A) or double-stranded (B) FAM-labeled DNA oligonucleotide (BB94) to GzmA, GzmB, histone H1 and BSA was measured by FP. (C, D) To determine whether binding was sequence dependent, interactions of GzmA (C) and GzmB (D) with 3′ FAM-labeled homo-oligomers (dA30, dC30 dT30) were measured by FP. Both Gzms bound pyrimidine tracts (dT30, dC30) more strongly than the purine tract dA30. The mean polarization values ± sem are plotted and the apparent Kd with 95% confidence interval in brackets is shown. Results are representative of at least three independent experiments.

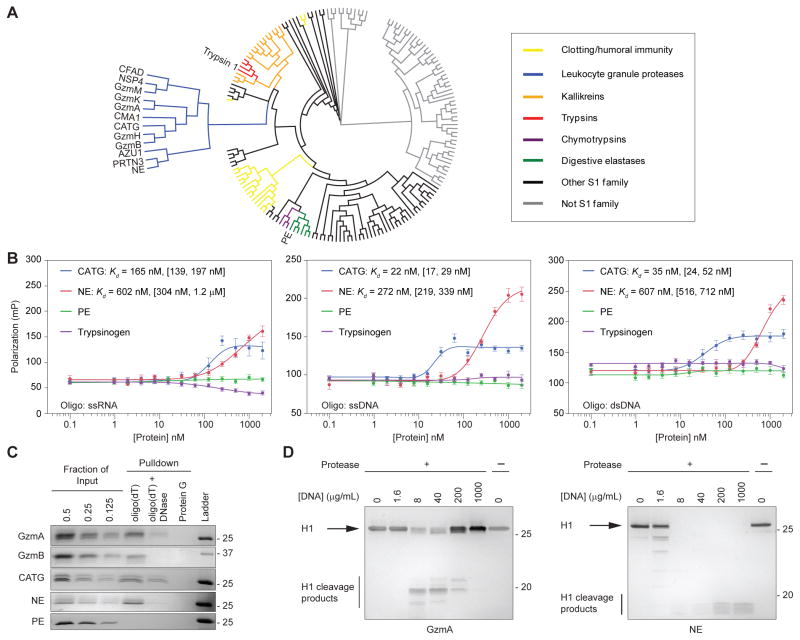

Myeloid granule serine proteases bind nucleic acids

Next we asked whether nucleic acid binding is a general property of serine proteases or limited to a subset. To visualize the evolutionary relationships between the Gzms and other serine proteases, we performed a phylogenetic analysis of all annotated human serine proteases. The Gzms form a monophyletic group with other leukocyte serine proteases (Fig. 4A). This group includes five neutrophil proteases (NE, CATG, NSP4, PRTN3, AZU1) (28) and the mast cell protease CMA1. The Gzms are more distantly related to digestive enzymes, such as pancreatic elastase (PE) and trypsin. We used FP to assess the affinity of native human CATG and NE, porcine PE, and bovine trypsinogen (the proenzyme of trypsin) for RNA, ssDNA and dsDNA (Fig. 4B). Both neutrophil proteases bound these nucleic acids with nanomolar affinity like the Gzms, but neither digestive protease bound. This agrees with an earlier study showing that NE binds to DNA (29). To validate DNA binding with an independent assay, we used oligo(dT)-conjugated beads to pull down the Gzms, neutrophil proteases and PE (Fig. 4C). Consistent with the FP results, the leukocyte proteases (GzmA, GzmB, NE and CATG), but not the digestive protease, bound to oligo(dT) beads. Binding was specific to DNA since it was decreased by pretreating the beads with DNase. The proteases also did not bind to protein G-conjugated beads. We hypothesized that DNA binding would enhance leukocyte protease cleavage of DNA binding protein substrates, as shown above for RNA and previously shown for GzmA cleavage of histone H1 (5). We treated purified histone H1, a target of both GzmA and NE with each protease in the presence of increasing concentrations of salmon sperm DNA. H1 cleavage by NE was greatly increased by adding even a small amount of DNA (Fig. 4D). H1 cleavage by GzmA was first promoted, then inhibited, by increasing amounts of salmon sperm DNA. Inhibition by high concentrations of exogenous RNA was also seen when we analyzed GzmB cleavage of hnRNP C1 (Fig. 1E). These results suggest that an excess of nucleic acids interferes with formation of a substrate-nucleic acid-protease complex. Collectively, these results demonstrate that nucleic acid binding is a conserved and functionally important property of leukocyte serine proteases.

Figure 4. Leukocyte serine proteases bind to RNA and DNA with nanomolar affinity.

(A) Phylogenetic analysis of all human serine proteases shows that leukocyte serine proteases form a monophyletic group. (B) Interactions of two neutrophil serine proteases (NE and CATG) and digestive serine proteases (trypsinogen and PE) with RNA, ssDNA and dsDNA were measured by FP. NE and CATG bound with nanomolar affinity, but the digestive proteases did not. The mean polarization values ± sem and the apparent Kd with 95% confidence interval in brackets is shown. (C) Direct binding of GzmA, GzmB, NE, CATG and PE to ssDNA was assessed by affinity pull-down with oligo(dT)25-conjugated beads. The leukocyte proteases bound, but the digestive enzyme did not. Binding was reduced by DNase treatment. None of the proteases bound to protein G beads. (D) Purified histone H1 was not cleaved in the absence of added DNA. Cleavage of histone H1 by GzmA and NE was assessed in the presence of increasing amounts of salmon sperm DNA. Addition of small amounts of DNA enhanced cleavage by both GzmA and NE. At higher concentrations, DNA inhibited GzmA cleavage. Results are representative of at least three independent experiments.

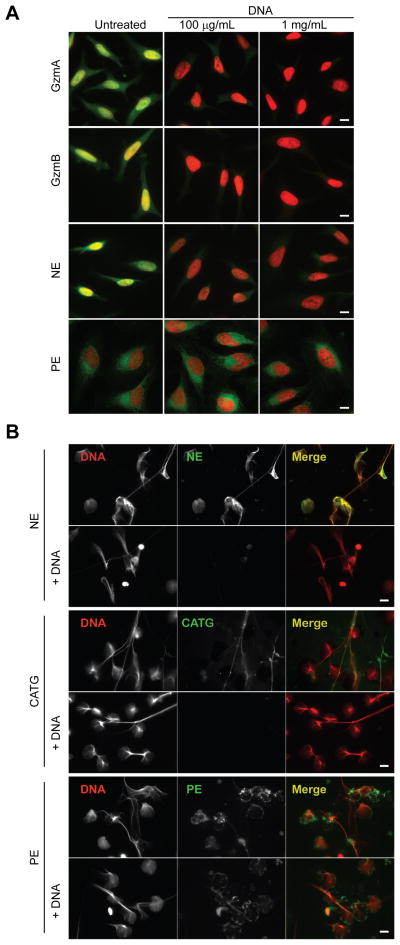

DNA binding mediates localization of Gzms to the nucleus

During killer cell attack, the Gzms rapidly concentrate in the nucleus of target cells by an unknown mechanism. A previous study suggested that nuclear localization is mediated by affinity of the Gzms to insoluble nuclear factors (3). We hypothesized that the nuclear accumulation of Gzms is driven by direct binding to nuclear DNA. To test this idea, we incubated fixed and permeabilized HeLa cells with AF488-labeled serine proteases and visualized their localization with fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 5A). As expected, the Gzms stained the cytosol and nucleus, but concentrated in the nucleus. To test whether nuclear accumulation was mediated by DNA binding, we co-incubated the Gzms with salmon sperm DNA before adding them to the fixed cells. Incubation with exogenous DNA abolished both cytosolic and nuclear staining of the Gzms (Fig. 5A). We treated fixed cells with DNase and RNase, which modestly reduced nuclear and cytosolic GzmB staining, respectively (Supplemental Fig. 2). DNase treatment did not remove all nuclear DNA, so it may be that GzmB binds to residual nucleic acids after nuclease treatment. Labeled NE also accumulated in the nuclei of fixed cells, in agreement with the known nuclear translocation of this enzyme during NETosis (12). PE did not localize to fixed cell nuclei and its staining intensity and pattern were not impacted by pre-incubation with salmon sperm DNA (Fig. 5A). Thus, DNA binding by the Gzms and NE likely mediates their nuclear trafficking during cytotoxic attack and NETosis, respectively.

Figure 5. DNA binding regulates nuclear localization of leukocyte serine proteases and binding to NETs.

The effect of DNA on localization of exogenously added serine proteases to permeabilized cells was assessed by fluorescence microscopy. (A) Permeabilized HeLa cells were incubated with AF488-labeled serine proteases (green) that had been preincubated with buffer or DNA, and then stained with DAPI (red). GzmA, GzmB and NE were visualized in the cytoplasm, but concentrated in the nucleus. Pre-incubation with salmon sperm DNA blocked cellular retention. PE did not localize to the nucleus and its staining pattern was not affected by pre-incubation with DNA. (B) AF488-labeled NE, CATG and PE (green) were added with or without salmon sperm DNA to neutrophils during NET formation. Cells were fixed and stained for DAPI (red). NE and CATG localized to NETs, but PE did not. Salmon sperm DNA blocked binding of NE and CATG to NETs. Images are representative of three independent experiments. Scale bar represents 10 μm.

Localization of NE and CATG to NETs is mediated by DNA binding

CATG and NE both concentrate on NETs (13). We asked whether DNA binding facilitates localization of these enzymes to NETs. Neutrophils isolated from human peripheral blood were treated with PMA for 3 hours to induce NET formation in the presence of AF488-labeled NE, CATG or PE. Competitor DNA was added to some samples during NET formation. Both neutrophil enzymes, but not PE, spontaneously concentrated on the NETs, and binding to the NETs was inhibited by adding salmon sperm DNA (Fig. 5B). Exogenous DNA added during NETosis also reduced the association of endogenous NE to NETs (Supplemental Fig. 3). Thus, CATG and NE specifically localize to NETs by binding to DNA.

Discussion

This work demonstrates that the Gzms and related leukocyte proteases are bona fide nucleic acid binding proteins with nanomolar affinities. The basis for substrate specificity of the Gzms, which are highly specific proteases, remains largely unknown. Although each Gzm has a strong preference for specific P1 residues in its substrates, primary amino acid sequence around the cleavage site does not predict Gzm cleavage. Structural features likely play a key role in Gzm substrate recognition. This study suggests that the high affinity of the Gzms for nucleic acids may be an important determinant of substrate specificity. Nucleic acid binding is a simple and elegant mechanism to direct leukocyte serine proteases to DNA and RNA binding protein targets and probably explains why nucleic acid binding proteins are highly over-represented amongst Gzm substrates. Gzms and their substrates may be brought together by binding to nearby sites on the same nucleic acid strand. The Gzms form a monophyletic group with other leukocyte serine proteases, which also bind to nucleic acids with high affinity. Importantly, nucleic acid binding regulates the sub-cellular localization of Gzms and neutrophil proteases. Leukocyte protease concentration in cell nuclei was prevented by exogenous DNA. Our results support the “affinity” model for Gzm nuclear concentration posited over a decade ago and identify DNA as the unknown insoluble factor mediating this phenomenon (3). Similarly, the localization of NE and CATG to NETs and the antimicrobial activity of NETs likely depend in part upon the affinity of these proteases for DNA.

The leukocyte serine proteases rank amongst the most cationic proteins in the cell, with very high predicted isoelectric points (pIs): GzmA – 9.22, GzmB – 9.69, CATG – 11.37, NE – 9.89 (20). The empirical pIs of NE and CATG are ~11 and >11, respectively (30). This raises the question of whether nucleic acid binding is specific or simply a consequence of charge-balancing electrostatic interactions. For several reasons, we believe binding is specific and physiologically relevant. First, the digestive serine proteases, which do not bind nucleic acids, are also cationic with similar pIs as the Gzms. Porcine PE has a reported pI of 9.5 to >11, while the pI of trypsinogen is ~9.3, but neither binds nucleic acids (31–33). Secondly, Gzm binding to DNA is sequence-specific, favoring pyrimidine oligomers. Third, these proteases directly bind DNA under physiologic conditions. Finally, charge alone does not preclude specificity; RNA and DNA binding proteins are characterized by cationic patches that mediate binding to nucleic acids by electrostatic interactions (34). The Gzm structures predict positively charged surfaces that could be nucleic acid binding sites (35, 36). Further biochemical and structural studies that look at the interactions of these leukocyte proteases with nucleic acids and specific protein substrates are needed.

Negatively charged sugars play a significant role in granule packaging and target cell uptake of cationic Gzms. In cytotoxic granules, the Gzms bind serglycin, a small negatively charged proteoglycan containing chondroitin 4-sulfate (37). Serglycin-null T cells are defective in packaging GzmB into granules. Upon degranulation, GzmB is released from serglycin and binds to cell membrane proteoglycans, most notably heparan sulfate. Purified GzmB has higher affinity for heparan sulfate than serglycin (38). Our results suggest that when Gzms enter target cells they bind to another class of negatively charged molecule, nucleic acids. Gzm binding to different anionic biomolecules as they move from the granules to the target cell nucleus may form a physical ‘chain of custody’ to ensure proper Gzm trafficking and targeting.

Nucleic acid binding enhances the activity and function of leukocyte serine proteases, which may be critical to Gzm induction of cell death and neutrophil protease-mediated NET formation and function. Exogenous DNA transformed purified H1 from a very weak substrate to a robust target. However excess DNA and RNA inhibited cleavage of H1 and hnRNP C1, respectively. A previous study also found that DNA inhibited NE and CATG proteolysis of the non-nucleic acid binding protein elastin (39). An excess of nucleic acid, which has high affinity for both the protease and its substrate, likely interferes with formation of the ternary protease-nucleic acid-substrate complex.

Preferential targeting of DNA and RNA binding proteins by Gzms is an underappreciated property critical for executing cell death. Nucleic acid binding is a simple mechanism to guide Gzms to targets that are essential for survival. Cleavage of nucleic acid binding substrates should enhance Gzm execution of death, independently of caspase activation. During Gzm-mediated cell death, targeting of RBPs disrupts pre-mRNA processing and nuclear export (4). In the extracellular environment, DNA binding may sequester leukocyte serine proteases to focus their activity on pathogens, which get caught in NETs, and minimize tissue injury.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Farokh Dotiwala and Nishant Dwivedi for input and technical assistance and Brian Beliveau and Nancy Kedersha for advice and reagents.

Grant support:

This work was supported by an NSF graduate research fellowship to MPT, NIH K08 grant HL094460 and a Boston Children’s Hospital Career Development Fellowship to JW, and NIH grant AI45587 to JL.

Abbreviations used in this article

- AF488

AlexaFluor 488

- CATG

Cathepsin G

- FP

Fluorescence polarization

- GO

Gene Ontology

- Gzm

Granzyme

- H1

Histone H1

- hnRNP

heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein

- NE

Neutrophil Elastase

- NET

Neutrophil Extracellular Trap

- PFN

Perforin

- RBP

RNA binding protein

- ssDNA

salmon sperm DNA

References

- 1.Chowdhury D, Lieberman J. Death by a Thousand Cuts: Granzyme Pathways of Programmed Cell Death. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:389–420. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jans DA, Jans P, Briggs LJ, Sutton V, Trapani JA. Nuclear Transport of Granzyme B (Fragmentin-2) J Biol Chem. 1996;271:30781–30789. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.48.30781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jans DA, Briggs LJ, Jans P, Froelich CJ, Parasivam G, Kumar S, Sutton VR, Trapani JA. Nuclear targeting of the serine protease granzyme A (fragmentin-1) J Cell Sci. 1998;111:2645–2654. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.17.2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rajani DK, Walch M, Martinvalet D, Thomas MP, Lieberman J. Alterations in RNA processing during immune-mediated programmed cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109:8688–8693. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201327109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang D, Pasternack MS, Beresford PJ, Wagner L, Greenberg AH, Lieberman J. Induction of Rapid Histone Degradation by the Cytotoxic T Lymphocyte Protease Granzyme A. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:3683–3690. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005390200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhu P, Martinvalet D, Chowdhury D, Zhang D, Schlesinger A, Lieberman J. The cytotoxic T lymphocyte protease granzyme A cleaves and inactivates poly(adenosine 5′-diphosphate-ribose) polymerase-1. Blood. 2009;114:1205–1216. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-195768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Domselaar R, Quadir R, van der Made AM, Broekhuizen R, Bovenschen N. All human granzymes target hnRNP K that is essential for tumor cell viability. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:22854–22864. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.365692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knickelbein JE, Khanna KM, Yee MB, Baty CJ, Kinchington PR, Hendricks RL. Noncytotoxic Lytic Granule–Mediated CD8+ T Cell Inhibition of HSV-1 Reactivation from Neuronal Latency. Science. 2008;322:268–271. doi: 10.1126/science.1164164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marcet-Palacios M, Duggan BL, Shostak I, Barry M, Geskes T, Wilkins JA, Yanagiya A, Sonenberg N, Bleackley RC. Granzyme B Inhibits Vaccinia Virus Production through Proteolytic Cleavage of Eukaryotic Initiation Factor 4 Gamma 3. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002447. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krem MM, Rose T, Di Cera E. Sequence Determinants of Function and Evolution in Serine Proteases. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2000;10:171–176. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(00)00068-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brinkmann V, Zychlinsky A. Neutrophil extracellular traps: Is immunity the second function of chromatin? J Cell Biol. 2012;198:773–783. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201203170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Papayannopoulos V, Metzler KD, Hakkim A, Zychlinsky A. Neutrophil elastase and myeloperoxidase regulate the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps. J Cell Biol. 2010;191:677–691. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201006052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Urban CF, Ermert D, Schmid M, Abu-Abed U, Goosmann C, Nacken W, Brinkmann V, Jungblut PR, Zychlinsky A. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Contain Calprotectin, a Cytosolic Protein Complex Involved in Host Defense against Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000639. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thiery J, Walch M, Jensen DK, Martinvalet D, Lieberman J. Current Protocols in Cell Biology. Vol. 47. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2010. Isolation of Cytotoxic T Cell and NK Granules and Purification of Their Effector Proteins; pp. 3.37pp. 1–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brinkmann V, Laube B, Abu Abed U, Goosmann C, Zychlinsky A. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps: How to Generate and Visualize Them. J Vis Exp. 2010;36 doi: 10.3791/1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Damme P, Maurer-Stroh S, Hao H, Colaert N, Timmerman E, Eisenhaber F, Vandekerckhove J, Gevaert K. The substrate specificity profile of human granzyme A. Biol Chem. 2010;391:983–997. doi: 10.1515/BC.2010.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Damme P, Maurer-Stroh S, Plasman K, Van Durme J, Colaert N, Timmerman E, De Bock PJ, Goethals M, Rousseau F, Schymkowitz J, Vandekerckhove J, Gevaert K. Analysis of Protein Processing by N-terminal Proteomics Reveals Novel Species-specific Substrate Determinants of Granzyme B Orthologs. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8:258–272. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800060-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berriz GF, Beaver JE, Cenik C, Tasan M, Roth FP. Next generation software for functional trend analysis. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:3043–3044. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carbon S, Ireland A, Mungall CJ, Shu S, Marshall B, Lewis S the AmiGO Hub and the Web Presence Working Group. . AmiGO: online access to ontology and annotation data. Bioinformatics. 2008;25:288–289. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The UniProt Consortium. Reorganizing the protein space at the Universal Protein Resource (UniProt) Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;40:D71–D75. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goujon M, McWilliam H, Li W, Valentin F, Squizzato S, Paern J, Lopez R. A new bioinformatics analysis tools framework at EMBL–EBI. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:W695–W699. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang H, Gao S, Lercher MJ, Hu S, Chen WH. EvolView, an online tool for visualizing, annotating and managing phylogenetic trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:W569–W572. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ryder SP, Williamson JR. Specificity of the STAR/GSG domain protein Qk1: Implications for the regulation of myelination. RNA. 2004;10:1449–1458. doi: 10.1261/rna.7780504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jantz D, Berg JM. Probing the DNA-Binding Affinity and Specificity of Designed Zinc Finger Proteins. Biophys J. 2010;98:852–860. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fialcowitz-White EJ, Brewer BY, Ballin JD, Willis CD, Toth EA, Wilson GM. Specific Protein Domains Mediate Cooperative Assembly of HuR Oligomers on AU-rich mRNA-destabilizing Sequences. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:20948–20959. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701751200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park S, Myszka DG, Yu M, Littler SJ, Laird-Offringa IA. HuD RNA Recognition Motifs Play Distinct Roles in the Formation of a Stable Complex with AU-Rich RNA. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:4765–4772. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.13.4765-4772.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nightingale KP, Pruss D, Wolffe AP. A Single High Affinity Binding Site for Histone H1 in a Nucleosome Containing the Xenopus borealis 5 S Ribosomal RNA Gene. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:7090–7094. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.12.7090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perera NC, Schilling O, Kittel H, Back W, Kremmer E, Jenne DE. NSP4, an elastase-related protease in human neutrophils with arginine specificity. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109:6229–6234. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200470109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Belorgey D, Bieth JG. DNA binds neutrophil elastase and mucus proteinase inhibitor and impairs their functional activity. FEBS Lett. 1995;361:265–268. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00173-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Travis J, Giles PJ, Porcelli L, Reilly CF, Baugh R, Powers J. Human leucocyte elastase and cathepsin G: structural and functional characteristics. Ciba Found Symp. 1979:51–68. doi: 10.1002/9780470720585.ch4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lewis UJ, Williams DE, Brink NG. Pancreatic Elastase: Purification, Properties, and Function. J Biol Chem. 1956;222:705–720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ardelt W. Physical parameters and chemical composition of porcine pancreatic elastase II. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1975;393:267–273. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(75)90053-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Higaki JN, Light A. The identification of neotrypsinogens in samples of bovine trypsinogen. Anal Biochem. 1985;148:111–120. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(85)90635-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shazman S, Mandel-Gutfreund Y. Classifying RNA-Binding Proteins Based on Electrostatic Properties. PLoS Comput Biol. 2008;4:e1000146. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Estébanez-Perpiñá E, Fuentes-Prior P, Belorgey D, Braun M, Kiefersauer R, Maskos K, Huber R, Rubin H, Bode W. Crystal Structure of the Caspase Activator Human Granzyme B, a Proteinase Highly Specific for an Asp-P1 Residue. Biol Chem. 2000;381:1203–1214. doi: 10.1515/BC.2000.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hink-Schauer C, Estebanez-Perpina E, Kurschus FC, Bode W, Jenne DE. Crystal structure of the apoptosis-inducing human granzyme A dimer. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2003;10:535–540. doi: 10.1038/nsb945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kolset SO, Tveit H. Serglycin – Structure and biology. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:1073–1085. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7455-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raja SM, Metkar SS, Höning S, Wang B, Russin WA, Pipalia NH, Menaa C, Belting M, Cao X, Dressel R, Froelich CJ. A novel mechanism for protein delivery: granzyme B undergoes electrostatic exchange from serglycin to target cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:20752–20761. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501181200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Duranton J, Belorgey D, Carrère J, Donato L, Moritz T, Bieth JG. Effect of DNase on the activity of neutrophil elastase, cathepsin G and proteinase 3 in the presence of DNA. FEBS Lett. 2000;473:154–156. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01512-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.